User login

Habit Reversal Therapy for Skin Picking Disorder

Practice Gap

Skin picking disorder is characterized by repetitive deliberate manipulation of the skin that causes noticeable tissue damage. It affects approximately 1.6% of adults in the United States and is associated with marked distress as well as a psychosocial impact.1 Complications of skin picking disorder can include ulceration, infection, scarring, and disfigurement.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques have been established to be effective in treating skin picking disorder.2 Although referral to a mental health professional is appropriate for patients with skin picking disorder, many of them may not be interested. Cognitive behavioral therapy for diseases at the intersection of psychiatry and dermatology typically is not included in dermatology curricula. Therefore, dermatologists should be aware of CBT techniques that can mitigate the impact of skin picking disorder for patients who decline referral to a mental health professional.

The Technique

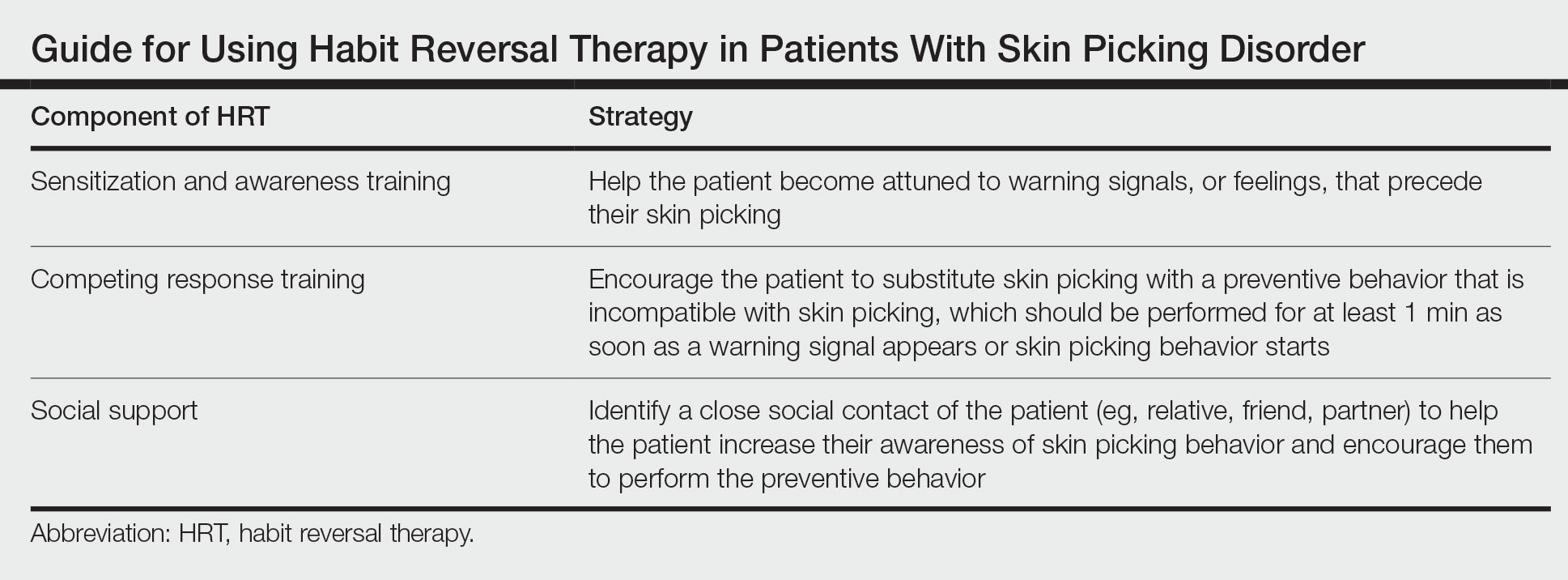

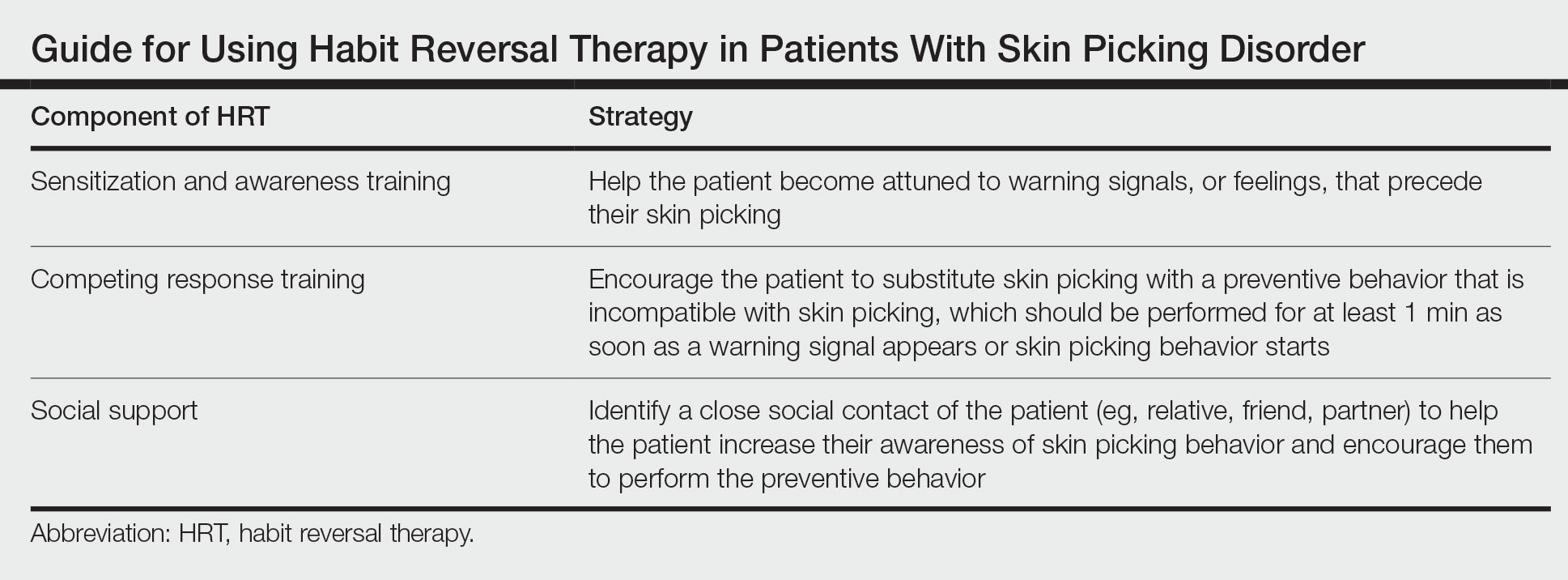

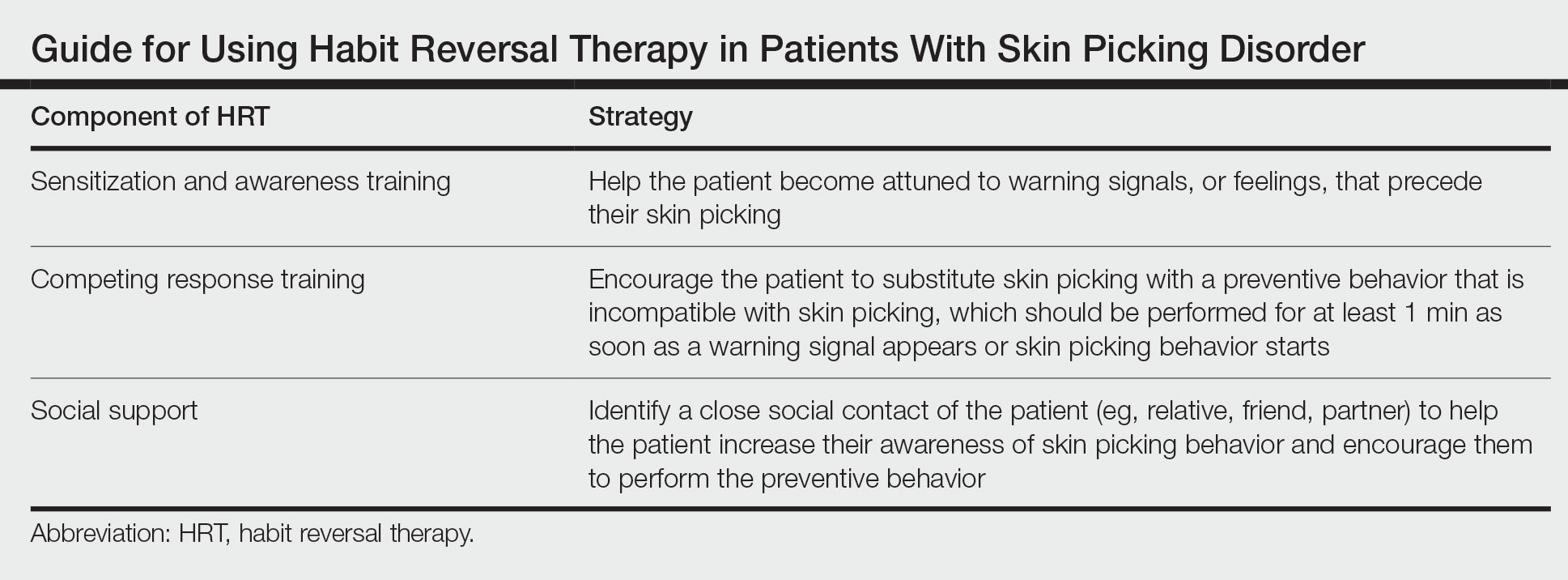

Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the more effective forms of psychotherapy for the treatment of skin picking disorder. Consistent utilization of CBT techniques can achieve relatively permanent change in brain function and contribute to long-term treatment outcomes. A particularly useful CBT technique for skin picking disorder is habit reversal therapy (HRT)(Table). Studies have shown that HRT techniques have demonstrated efficacy in skin picking disorder with sustained impact.3 Patients treated with HRT have reported a greater decrease in skin picking compared with controls after only 3 sessions (P<.01).4 There are 3 elements to HRT:

1. Sensitization and awareness training: This facet of HRT involves helping the patient become attuned to warning signals, or feelings, that precede their skin picking, as skin picking often occurs automatically without the patient noticing. Such feelings can include tingling of the skin, tension, and a feeling of being overwhelmed.5 Ideally, the physician works with the patient to identify 2 or 3 warning signals that precede skin picking behavior.

2. Competing response training: The patient is encouraged to substitute skin picking with a preventive behavior—for example, crossing the arms and gently squeezing the fists—that is incompatible with skin picking. The preventive behavior should be performed for at least 1 minute as soon as a warning signal appears or skin picking behavior starts. After 1 minute, if the urge for skin picking recurs, then the patient should repeat the preventive behavior.5 It can be helpful to practice the preventive behavior with the patient once in the clinic.

3. Social support: This technique involves identifying a close social contact of the patient (eg, relative, friend, partner) to help the patient increase their awareness of skin picking behavior and encourage them to perform the preventive behavior.5 The purpose of identifying a close social contact is to ensure accountability for the patient in their day-to-day life, given the limited scope of the relationship between the patient and the dermatologist.

Other practical solutions to skin picking include advising patients to cut their nails short; using finger cots to cover the nails and thus lessen the potential for skin injury; and using a sensory toy, such as a fidget spinner, to distract or occupy the patient when they feel the urge for skin picking.

Practice Implications

Although skin picking disorder is a challenging condition to manage, there are proven techniques for treatment. Techniques drawn from HRT are quite practical and can be implemented by dermatologists for patients with skin picking disorder to reduce the burden of their disease.

- Keuthen NJ, Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, et al. The prevalence of pathologic skin picking in US adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:183-186. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.04.003

- Jafferany M, Mkhoyan R, Arora G, et al. Treatment of skin picking disorder: interdisciplinary role of dermatologist and psychiatrist. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13837. doi:10.1111/dth.13837

- Schuck K, Keijsers GP, Rinck M. The effects of brief cognitive-behaviour therapy for pathological skin picking: a randomized comparison to wait-list control. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.005

- Teng EJ, Woods DW, Twohig MP. Habit reversal as a treatment for chronic skin picking: a pilot investigation. Behav Modif. 2006;30:411-422. doi:10.1177/0145445504265707

- Torales J, Páez L, O’Higgins M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for excoriation (skin picking) disorder. Telangana J Psych. 2016;2:27-30.

Practice Gap

Skin picking disorder is characterized by repetitive deliberate manipulation of the skin that causes noticeable tissue damage. It affects approximately 1.6% of adults in the United States and is associated with marked distress as well as a psychosocial impact.1 Complications of skin picking disorder can include ulceration, infection, scarring, and disfigurement.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques have been established to be effective in treating skin picking disorder.2 Although referral to a mental health professional is appropriate for patients with skin picking disorder, many of them may not be interested. Cognitive behavioral therapy for diseases at the intersection of psychiatry and dermatology typically is not included in dermatology curricula. Therefore, dermatologists should be aware of CBT techniques that can mitigate the impact of skin picking disorder for patients who decline referral to a mental health professional.

The Technique

Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the more effective forms of psychotherapy for the treatment of skin picking disorder. Consistent utilization of CBT techniques can achieve relatively permanent change in brain function and contribute to long-term treatment outcomes. A particularly useful CBT technique for skin picking disorder is habit reversal therapy (HRT)(Table). Studies have shown that HRT techniques have demonstrated efficacy in skin picking disorder with sustained impact.3 Patients treated with HRT have reported a greater decrease in skin picking compared with controls after only 3 sessions (P<.01).4 There are 3 elements to HRT:

1. Sensitization and awareness training: This facet of HRT involves helping the patient become attuned to warning signals, or feelings, that precede their skin picking, as skin picking often occurs automatically without the patient noticing. Such feelings can include tingling of the skin, tension, and a feeling of being overwhelmed.5 Ideally, the physician works with the patient to identify 2 or 3 warning signals that precede skin picking behavior.

2. Competing response training: The patient is encouraged to substitute skin picking with a preventive behavior—for example, crossing the arms and gently squeezing the fists—that is incompatible with skin picking. The preventive behavior should be performed for at least 1 minute as soon as a warning signal appears or skin picking behavior starts. After 1 minute, if the urge for skin picking recurs, then the patient should repeat the preventive behavior.5 It can be helpful to practice the preventive behavior with the patient once in the clinic.

3. Social support: This technique involves identifying a close social contact of the patient (eg, relative, friend, partner) to help the patient increase their awareness of skin picking behavior and encourage them to perform the preventive behavior.5 The purpose of identifying a close social contact is to ensure accountability for the patient in their day-to-day life, given the limited scope of the relationship between the patient and the dermatologist.

Other practical solutions to skin picking include advising patients to cut their nails short; using finger cots to cover the nails and thus lessen the potential for skin injury; and using a sensory toy, such as a fidget spinner, to distract or occupy the patient when they feel the urge for skin picking.

Practice Implications

Although skin picking disorder is a challenging condition to manage, there are proven techniques for treatment. Techniques drawn from HRT are quite practical and can be implemented by dermatologists for patients with skin picking disorder to reduce the burden of their disease.

Practice Gap

Skin picking disorder is characterized by repetitive deliberate manipulation of the skin that causes noticeable tissue damage. It affects approximately 1.6% of adults in the United States and is associated with marked distress as well as a psychosocial impact.1 Complications of skin picking disorder can include ulceration, infection, scarring, and disfigurement.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques have been established to be effective in treating skin picking disorder.2 Although referral to a mental health professional is appropriate for patients with skin picking disorder, many of them may not be interested. Cognitive behavioral therapy for diseases at the intersection of psychiatry and dermatology typically is not included in dermatology curricula. Therefore, dermatologists should be aware of CBT techniques that can mitigate the impact of skin picking disorder for patients who decline referral to a mental health professional.

The Technique

Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the more effective forms of psychotherapy for the treatment of skin picking disorder. Consistent utilization of CBT techniques can achieve relatively permanent change in brain function and contribute to long-term treatment outcomes. A particularly useful CBT technique for skin picking disorder is habit reversal therapy (HRT)(Table). Studies have shown that HRT techniques have demonstrated efficacy in skin picking disorder with sustained impact.3 Patients treated with HRT have reported a greater decrease in skin picking compared with controls after only 3 sessions (P<.01).4 There are 3 elements to HRT:

1. Sensitization and awareness training: This facet of HRT involves helping the patient become attuned to warning signals, or feelings, that precede their skin picking, as skin picking often occurs automatically without the patient noticing. Such feelings can include tingling of the skin, tension, and a feeling of being overwhelmed.5 Ideally, the physician works with the patient to identify 2 or 3 warning signals that precede skin picking behavior.

2. Competing response training: The patient is encouraged to substitute skin picking with a preventive behavior—for example, crossing the arms and gently squeezing the fists—that is incompatible with skin picking. The preventive behavior should be performed for at least 1 minute as soon as a warning signal appears or skin picking behavior starts. After 1 minute, if the urge for skin picking recurs, then the patient should repeat the preventive behavior.5 It can be helpful to practice the preventive behavior with the patient once in the clinic.

3. Social support: This technique involves identifying a close social contact of the patient (eg, relative, friend, partner) to help the patient increase their awareness of skin picking behavior and encourage them to perform the preventive behavior.5 The purpose of identifying a close social contact is to ensure accountability for the patient in their day-to-day life, given the limited scope of the relationship between the patient and the dermatologist.

Other practical solutions to skin picking include advising patients to cut their nails short; using finger cots to cover the nails and thus lessen the potential for skin injury; and using a sensory toy, such as a fidget spinner, to distract or occupy the patient when they feel the urge for skin picking.

Practice Implications

Although skin picking disorder is a challenging condition to manage, there are proven techniques for treatment. Techniques drawn from HRT are quite practical and can be implemented by dermatologists for patients with skin picking disorder to reduce the burden of their disease.

- Keuthen NJ, Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, et al. The prevalence of pathologic skin picking in US adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:183-186. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.04.003

- Jafferany M, Mkhoyan R, Arora G, et al. Treatment of skin picking disorder: interdisciplinary role of dermatologist and psychiatrist. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13837. doi:10.1111/dth.13837

- Schuck K, Keijsers GP, Rinck M. The effects of brief cognitive-behaviour therapy for pathological skin picking: a randomized comparison to wait-list control. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.005

- Teng EJ, Woods DW, Twohig MP. Habit reversal as a treatment for chronic skin picking: a pilot investigation. Behav Modif. 2006;30:411-422. doi:10.1177/0145445504265707

- Torales J, Páez L, O’Higgins M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for excoriation (skin picking) disorder. Telangana J Psych. 2016;2:27-30.

- Keuthen NJ, Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, et al. The prevalence of pathologic skin picking in US adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:183-186. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.04.003

- Jafferany M, Mkhoyan R, Arora G, et al. Treatment of skin picking disorder: interdisciplinary role of dermatologist and psychiatrist. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13837. doi:10.1111/dth.13837

- Schuck K, Keijsers GP, Rinck M. The effects of brief cognitive-behaviour therapy for pathological skin picking: a randomized comparison to wait-list control. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.005

- Teng EJ, Woods DW, Twohig MP. Habit reversal as a treatment for chronic skin picking: a pilot investigation. Behav Modif. 2006;30:411-422. doi:10.1177/0145445504265707

- Torales J, Páez L, O’Higgins M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for excoriation (skin picking) disorder. Telangana J Psych. 2016;2:27-30.

Atypical Presentation of Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

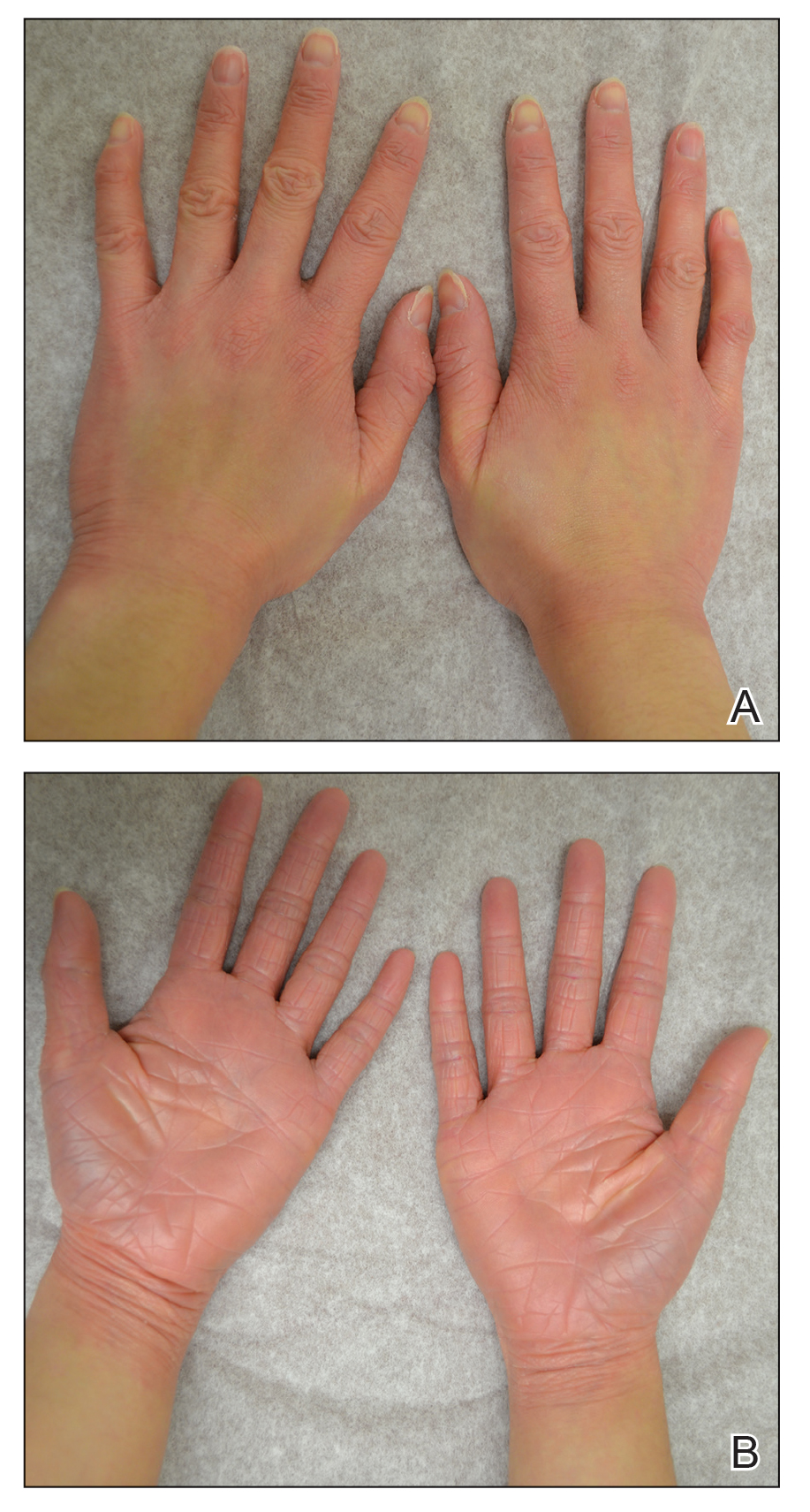

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

Practice Points

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.

- The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations.

Recent Developments in Psychodermatology and Psychopharmacology for Delusional Patients

The management of delusional infestation (DI), also known as Morgellons disease or delusional parasitosis, can lead to some of the most difficult and stressful patient encounters in dermatology. As a specialty, dermatology providers are trained to respect scientific objectivity and pride themselves on their visual diagnostic acumen. Therefore, having to accommodate a patient’s erroneous ideations and potentially treat a psychiatric pathology poses a challenge for many dermatology providers because it requires shifting their mindset to where the subjective reality becomes the primary issue during the visit. This disconnect may lead to strife between the patient and the provider. All of these issues may make it difficult for dermatologists to connect with DI patients with the usual courtesy and consideration given to other patients. Moreover, some dermatologists find it difficult to respect the chief concern, which often is seen as purely psychological because there may be some lingering bias where psychological concerns perhaps are not seen as bona fide or legitimate disorders.

Is There a Biologic Basis for DI? A New Theory on the Etiology of Delusional Parasitosis

It is important to distinguish DI phenomenology into primary and secondary causes. Primary DI refers to cases where the delusion and formication occur spontaneously. In contrast, in secondary DI the delusion and other manifestations (eg, formication) happen secondarily to underlying broader diagnoses such as illicit substance abuse, primary psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, organic brain syndrome, and vitamin B12 deficiency.

It is well known that primary DI overwhelmingly occurs in older women, whereas secondary DI does not show this same predilection. It has been a big unanswered question as to why primary DI so often occurs not only in women but specifically in older women. The latest theory that has been advancing in Europe and is supported by some data, including magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, involves the dopamine transporter (DAT) system, which is important in making sure the dopamine level in the intersynaptic space is not excessive.1 The DAT system is much more prominent in woman vs men and deteriorates with age due to declining estrogen levels. This age-related loss of striatal DAT is thought to be one possible etiology of DI. It has been hypothesized that decreased DAT functioning may cause an increase in extracellular striatal dopamine levels in the synapse that can lead to tactile hallucinations and delusions, which are hallmark symptoms seen in DI. Given that women experience a greater age-related DAT decline in striatal subregions than men, it is thought that primary DI mainly affects older women due to the decline of neuroprotective effects of estrogen on DAT activity with age.2 Further studies should evaluate the possibility of estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of DI.

Improving Care of Psychodermatology Patients in Clinic

There are several medications that are known to be effective for the treatment of DI, including pimozide, risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine, among others. Pimozide is uniquely accepted by DI patients because it has no official psychiatric indication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it is only indicated in the United States for Tourette syndrome, which is a neurologic disorder. Therefore, pimozide arguably can be disregarded as a true antipsychotic agent. The fact that its chemical structure is similar to those of bona fide antipsychotic medications does not necessarily put it in this same category, as there also are antiemetic and antitussive medications (eg, prochlorperazine, promethazine) with chemical structures similar to antipsychotics, but clinicians generally do not think of these drugs as antipsychotics despite the similarities. This nuanced and admittedly somewhat arbitrary categorization is critical to patient care; in our clinic, we have found that patients who categorically refuse to consider all psychiatric medications are much more willing to try pimozide for this very reason, that this medication can uniquely be presented to the DI patient as an agent not used in psychiatry. We have found great success in treatment with pimozide, even with relatively low doses.3,4

One of the main reasons dermatologists are reluctant to prescribe antipsychotic medications or even pimozide is the concern for side effects, especially tardive dyskinesia (TD), which is thought to be irreversible and untreatable. However, after a half century of worldwide use of pimozide in dermatology, a PubMed search of English-language articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pimozide and tardive dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia and delusions of parasitosis, tardive dyskinesia and dermatology, and tardive dyskinesia and delusional infestation/Morgellons disease yielded only 1 known case of TD reported in dermatologic use for DI.5 In this particular case, TD-like symptoms did not appear until after pimozide had been discontinued for 1 month. Therefore, it is not clear if this case was true TD or a condition known as withdrawal dyskinesia, which mimics TD and usually is self-limiting.5

The senior author (J.K.) has been using pimozide for treatment of DI for more than 30 years and has not encountered TD or any other notable side effects. The reason for this extremely low incidence of side effects may be due to its high efficacy in treating DI; hence, only a low dose of pimozide usually is needed. At the University of California, San Francisco, Psychodermatology Clinic, pimozide typically is used to treat DI at a low dose of 3 mg or less daily, starting with 0.5 or 1 mg and slowly titrating upward until a clinically effective dose is reached. Pimozide rarely is used long-term; after the resolution of symptoms, the dose usually is continued at the clinically effective dose for a few months and then is slowly tapered off. In contrast, for a condition such as schizophrenia, an antipsychotic medication often is needed at high doses for life, resulting in higher TD occurrences being reported. Therefore, even though the newer antipsychotic agents are preferable to pimozide because of their somewhat lower risk for TD, in actual clinical practice many, if not most, DI patients detest any suggestion of taking a medication for “crazy people.” Thus, we find that pimozide’s inherent superior acceptability among DI patients often is critical to enabling any effective treatment to occur at all due to the fact that the provider can honestly say that pimozide has no FDA psychiatric indication.

Still, one of the biggest apprehensions with initiating and continuing these medications in dermatology is fear of TD. Now, dermatologists can be made aware that if this very rare side effect occurs, there are medications approved to treat TD, even if the anti-TD therapy is administered by a neurologist. For the first time, 2 medications were approved by the FDA for treatment of TD in 2017, namely valbenazine and deutetrabenazine. These medications represent a class known as vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitors and function by ultimately reducing the amount of dopamine released from the presynaptic dopaminergic neurons. In phase 3 trials for valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, 40% (N=234) and 34% (N=222) of patients, respectively, achieved a response, which was defined as at least a 50% decrease from baseline on the abnormal involuntary movement scale dyskinesia score in 6 to 12 weeks compared to 9% and 12%, respectively, with placebo.Discontinuation because of an adverse event was seldom encountered with both medications.6

Conclusion

The recent developments in psychodermatology with regard to DI are encouraging. The advent of new evidence and theories suggestive of an organic basis for DI could help this condition become more respected in the eyes of the dermatologist as a bona fide disorder. Moreover, the new developments and availability of medications that can treat TD can further make it easier for dermatologists to consider offering DI patients truly meaningful treatment that they desperately need. Therefore, both of these developments are welcomed for our specialty.

- Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. a new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1351-1358.

- Chan SY, Koo J. Sex differences in primary delusional infestation: an insight into etiology and potential novel therapy. Int J Women Dermatol. 2020;6:226.

- Lorenzo CR, Koo J. Pimozide in dermatologic practice: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:339-349.

- Brownstone ND, Beck K, Sekhon S, et al. Morgellons Disease. 2nd ed. Kindle Direct Publishing; 2020.

- Thomson AM, Wallace J, Kobylecki C. Tardive dyskinesia after drug withdrawal in two older adults: clinical features, complications and management. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:563-564.

- Citrome L. Tardive dyskinesia: placing vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors into clinical perspective. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18:323-332.

The management of delusional infestation (DI), also known as Morgellons disease or delusional parasitosis, can lead to some of the most difficult and stressful patient encounters in dermatology. As a specialty, dermatology providers are trained to respect scientific objectivity and pride themselves on their visual diagnostic acumen. Therefore, having to accommodate a patient’s erroneous ideations and potentially treat a psychiatric pathology poses a challenge for many dermatology providers because it requires shifting their mindset to where the subjective reality becomes the primary issue during the visit. This disconnect may lead to strife between the patient and the provider. All of these issues may make it difficult for dermatologists to connect with DI patients with the usual courtesy and consideration given to other patients. Moreover, some dermatologists find it difficult to respect the chief concern, which often is seen as purely psychological because there may be some lingering bias where psychological concerns perhaps are not seen as bona fide or legitimate disorders.

Is There a Biologic Basis for DI? A New Theory on the Etiology of Delusional Parasitosis

It is important to distinguish DI phenomenology into primary and secondary causes. Primary DI refers to cases where the delusion and formication occur spontaneously. In contrast, in secondary DI the delusion and other manifestations (eg, formication) happen secondarily to underlying broader diagnoses such as illicit substance abuse, primary psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, organic brain syndrome, and vitamin B12 deficiency.

It is well known that primary DI overwhelmingly occurs in older women, whereas secondary DI does not show this same predilection. It has been a big unanswered question as to why primary DI so often occurs not only in women but specifically in older women. The latest theory that has been advancing in Europe and is supported by some data, including magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, involves the dopamine transporter (DAT) system, which is important in making sure the dopamine level in the intersynaptic space is not excessive.1 The DAT system is much more prominent in woman vs men and deteriorates with age due to declining estrogen levels. This age-related loss of striatal DAT is thought to be one possible etiology of DI. It has been hypothesized that decreased DAT functioning may cause an increase in extracellular striatal dopamine levels in the synapse that can lead to tactile hallucinations and delusions, which are hallmark symptoms seen in DI. Given that women experience a greater age-related DAT decline in striatal subregions than men, it is thought that primary DI mainly affects older women due to the decline of neuroprotective effects of estrogen on DAT activity with age.2 Further studies should evaluate the possibility of estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of DI.

Improving Care of Psychodermatology Patients in Clinic

There are several medications that are known to be effective for the treatment of DI, including pimozide, risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine, among others. Pimozide is uniquely accepted by DI patients because it has no official psychiatric indication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it is only indicated in the United States for Tourette syndrome, which is a neurologic disorder. Therefore, pimozide arguably can be disregarded as a true antipsychotic agent. The fact that its chemical structure is similar to those of bona fide antipsychotic medications does not necessarily put it in this same category, as there also are antiemetic and antitussive medications (eg, prochlorperazine, promethazine) with chemical structures similar to antipsychotics, but clinicians generally do not think of these drugs as antipsychotics despite the similarities. This nuanced and admittedly somewhat arbitrary categorization is critical to patient care; in our clinic, we have found that patients who categorically refuse to consider all psychiatric medications are much more willing to try pimozide for this very reason, that this medication can uniquely be presented to the DI patient as an agent not used in psychiatry. We have found great success in treatment with pimozide, even with relatively low doses.3,4

One of the main reasons dermatologists are reluctant to prescribe antipsychotic medications or even pimozide is the concern for side effects, especially tardive dyskinesia (TD), which is thought to be irreversible and untreatable. However, after a half century of worldwide use of pimozide in dermatology, a PubMed search of English-language articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pimozide and tardive dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia and delusions of parasitosis, tardive dyskinesia and dermatology, and tardive dyskinesia and delusional infestation/Morgellons disease yielded only 1 known case of TD reported in dermatologic use for DI.5 In this particular case, TD-like symptoms did not appear until after pimozide had been discontinued for 1 month. Therefore, it is not clear if this case was true TD or a condition known as withdrawal dyskinesia, which mimics TD and usually is self-limiting.5

The senior author (J.K.) has been using pimozide for treatment of DI for more than 30 years and has not encountered TD or any other notable side effects. The reason for this extremely low incidence of side effects may be due to its high efficacy in treating DI; hence, only a low dose of pimozide usually is needed. At the University of California, San Francisco, Psychodermatology Clinic, pimozide typically is used to treat DI at a low dose of 3 mg or less daily, starting with 0.5 or 1 mg and slowly titrating upward until a clinically effective dose is reached. Pimozide rarely is used long-term; after the resolution of symptoms, the dose usually is continued at the clinically effective dose for a few months and then is slowly tapered off. In contrast, for a condition such as schizophrenia, an antipsychotic medication often is needed at high doses for life, resulting in higher TD occurrences being reported. Therefore, even though the newer antipsychotic agents are preferable to pimozide because of their somewhat lower risk for TD, in actual clinical practice many, if not most, DI patients detest any suggestion of taking a medication for “crazy people.” Thus, we find that pimozide’s inherent superior acceptability among DI patients often is critical to enabling any effective treatment to occur at all due to the fact that the provider can honestly say that pimozide has no FDA psychiatric indication.

Still, one of the biggest apprehensions with initiating and continuing these medications in dermatology is fear of TD. Now, dermatologists can be made aware that if this very rare side effect occurs, there are medications approved to treat TD, even if the anti-TD therapy is administered by a neurologist. For the first time, 2 medications were approved by the FDA for treatment of TD in 2017, namely valbenazine and deutetrabenazine. These medications represent a class known as vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitors and function by ultimately reducing the amount of dopamine released from the presynaptic dopaminergic neurons. In phase 3 trials for valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, 40% (N=234) and 34% (N=222) of patients, respectively, achieved a response, which was defined as at least a 50% decrease from baseline on the abnormal involuntary movement scale dyskinesia score in 6 to 12 weeks compared to 9% and 12%, respectively, with placebo.Discontinuation because of an adverse event was seldom encountered with both medications.6

Conclusion

The recent developments in psychodermatology with regard to DI are encouraging. The advent of new evidence and theories suggestive of an organic basis for DI could help this condition become more respected in the eyes of the dermatologist as a bona fide disorder. Moreover, the new developments and availability of medications that can treat TD can further make it easier for dermatologists to consider offering DI patients truly meaningful treatment that they desperately need. Therefore, both of these developments are welcomed for our specialty.

The management of delusional infestation (DI), also known as Morgellons disease or delusional parasitosis, can lead to some of the most difficult and stressful patient encounters in dermatology. As a specialty, dermatology providers are trained to respect scientific objectivity and pride themselves on their visual diagnostic acumen. Therefore, having to accommodate a patient’s erroneous ideations and potentially treat a psychiatric pathology poses a challenge for many dermatology providers because it requires shifting their mindset to where the subjective reality becomes the primary issue during the visit. This disconnect may lead to strife between the patient and the provider. All of these issues may make it difficult for dermatologists to connect with DI patients with the usual courtesy and consideration given to other patients. Moreover, some dermatologists find it difficult to respect the chief concern, which often is seen as purely psychological because there may be some lingering bias where psychological concerns perhaps are not seen as bona fide or legitimate disorders.

Is There a Biologic Basis for DI? A New Theory on the Etiology of Delusional Parasitosis

It is important to distinguish DI phenomenology into primary and secondary causes. Primary DI refers to cases where the delusion and formication occur spontaneously. In contrast, in secondary DI the delusion and other manifestations (eg, formication) happen secondarily to underlying broader diagnoses such as illicit substance abuse, primary psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, organic brain syndrome, and vitamin B12 deficiency.

It is well known that primary DI overwhelmingly occurs in older women, whereas secondary DI does not show this same predilection. It has been a big unanswered question as to why primary DI so often occurs not only in women but specifically in older women. The latest theory that has been advancing in Europe and is supported by some data, including magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, involves the dopamine transporter (DAT) system, which is important in making sure the dopamine level in the intersynaptic space is not excessive.1 The DAT system is much more prominent in woman vs men and deteriorates with age due to declining estrogen levels. This age-related loss of striatal DAT is thought to be one possible etiology of DI. It has been hypothesized that decreased DAT functioning may cause an increase in extracellular striatal dopamine levels in the synapse that can lead to tactile hallucinations and delusions, which are hallmark symptoms seen in DI. Given that women experience a greater age-related DAT decline in striatal subregions than men, it is thought that primary DI mainly affects older women due to the decline of neuroprotective effects of estrogen on DAT activity with age.2 Further studies should evaluate the possibility of estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of DI.

Improving Care of Psychodermatology Patients in Clinic

There are several medications that are known to be effective for the treatment of DI, including pimozide, risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine, among others. Pimozide is uniquely accepted by DI patients because it has no official psychiatric indication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it is only indicated in the United States for Tourette syndrome, which is a neurologic disorder. Therefore, pimozide arguably can be disregarded as a true antipsychotic agent. The fact that its chemical structure is similar to those of bona fide antipsychotic medications does not necessarily put it in this same category, as there also are antiemetic and antitussive medications (eg, prochlorperazine, promethazine) with chemical structures similar to antipsychotics, but clinicians generally do not think of these drugs as antipsychotics despite the similarities. This nuanced and admittedly somewhat arbitrary categorization is critical to patient care; in our clinic, we have found that patients who categorically refuse to consider all psychiatric medications are much more willing to try pimozide for this very reason, that this medication can uniquely be presented to the DI patient as an agent not used in psychiatry. We have found great success in treatment with pimozide, even with relatively low doses.3,4

One of the main reasons dermatologists are reluctant to prescribe antipsychotic medications or even pimozide is the concern for side effects, especially tardive dyskinesia (TD), which is thought to be irreversible and untreatable. However, after a half century of worldwide use of pimozide in dermatology, a PubMed search of English-language articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pimozide and tardive dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia and delusions of parasitosis, tardive dyskinesia and dermatology, and tardive dyskinesia and delusional infestation/Morgellons disease yielded only 1 known case of TD reported in dermatologic use for DI.5 In this particular case, TD-like symptoms did not appear until after pimozide had been discontinued for 1 month. Therefore, it is not clear if this case was true TD or a condition known as withdrawal dyskinesia, which mimics TD and usually is self-limiting.5

The senior author (J.K.) has been using pimozide for treatment of DI for more than 30 years and has not encountered TD or any other notable side effects. The reason for this extremely low incidence of side effects may be due to its high efficacy in treating DI; hence, only a low dose of pimozide usually is needed. At the University of California, San Francisco, Psychodermatology Clinic, pimozide typically is used to treat DI at a low dose of 3 mg or less daily, starting with 0.5 or 1 mg and slowly titrating upward until a clinically effective dose is reached. Pimozide rarely is used long-term; after the resolution of symptoms, the dose usually is continued at the clinically effective dose for a few months and then is slowly tapered off. In contrast, for a condition such as schizophrenia, an antipsychotic medication often is needed at high doses for life, resulting in higher TD occurrences being reported. Therefore, even though the newer antipsychotic agents are preferable to pimozide because of their somewhat lower risk for TD, in actual clinical practice many, if not most, DI patients detest any suggestion of taking a medication for “crazy people.” Thus, we find that pimozide’s inherent superior acceptability among DI patients often is critical to enabling any effective treatment to occur at all due to the fact that the provider can honestly say that pimozide has no FDA psychiatric indication.

Still, one of the biggest apprehensions with initiating and continuing these medications in dermatology is fear of TD. Now, dermatologists can be made aware that if this very rare side effect occurs, there are medications approved to treat TD, even if the anti-TD therapy is administered by a neurologist. For the first time, 2 medications were approved by the FDA for treatment of TD in 2017, namely valbenazine and deutetrabenazine. These medications represent a class known as vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitors and function by ultimately reducing the amount of dopamine released from the presynaptic dopaminergic neurons. In phase 3 trials for valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, 40% (N=234) and 34% (N=222) of patients, respectively, achieved a response, which was defined as at least a 50% decrease from baseline on the abnormal involuntary movement scale dyskinesia score in 6 to 12 weeks compared to 9% and 12%, respectively, with placebo.Discontinuation because of an adverse event was seldom encountered with both medications.6

Conclusion

The recent developments in psychodermatology with regard to DI are encouraging. The advent of new evidence and theories suggestive of an organic basis for DI could help this condition become more respected in the eyes of the dermatologist as a bona fide disorder. Moreover, the new developments and availability of medications that can treat TD can further make it easier for dermatologists to consider offering DI patients truly meaningful treatment that they desperately need. Therefore, both of these developments are welcomed for our specialty.

- Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. a new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1351-1358.

- Chan SY, Koo J. Sex differences in primary delusional infestation: an insight into etiology and potential novel therapy. Int J Women Dermatol. 2020;6:226.

- Lorenzo CR, Koo J. Pimozide in dermatologic practice: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:339-349.

- Brownstone ND, Beck K, Sekhon S, et al. Morgellons Disease. 2nd ed. Kindle Direct Publishing; 2020.

- Thomson AM, Wallace J, Kobylecki C. Tardive dyskinesia after drug withdrawal in two older adults: clinical features, complications and management. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:563-564.

- Citrome L. Tardive dyskinesia: placing vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors into clinical perspective. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18:323-332.

- Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. a new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1351-1358.

- Chan SY, Koo J. Sex differences in primary delusional infestation: an insight into etiology and potential novel therapy. Int J Women Dermatol. 2020;6:226.

- Lorenzo CR, Koo J. Pimozide in dermatologic practice: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:339-349.

- Brownstone ND, Beck K, Sekhon S, et al. Morgellons Disease. 2nd ed. Kindle Direct Publishing; 2020.

- Thomson AM, Wallace J, Kobylecki C. Tardive dyskinesia after drug withdrawal in two older adults: clinical features, complications and management. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:563-564.

- Citrome L. Tardive dyskinesia: placing vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors into clinical perspective. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18:323-332.

Depression and Suicidality in Psoriasis and Clinical Studies of Brodalumab: A Narrative Review

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that affects patients’ quality of life and social interactions.1 Several studies have shown a strong consistent association between psoriasis and depression as well as possible suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB).1-13 Notable findings from a 2018 review found depression prevalence ranged from 2.1% to 33.7% among patients with psoriasis vs 0% to 22.7% among unaffected patients.7 In a 2017 meta-analysis, Singh et al2 found increased odds of SIB (odds ratio [OR], 2.05), attempted suicide (OR, 1.32), and completed suicide (OR, 1.20) in patients with psoriasis compared to those without psoriasis. In 2018, Wu and colleagues7 reported that odds of SIB among patients with psoriasis ranged from 1.01 to 1.94 times those of patients without psoriasis, and SIB and suicide attempts were more common than in patients with other dermatologic conditions. Koo and colleagues1 reached similar conclusions. At the same time, the occurrence of attempted and completed suicides among patients in psoriasis clinical trials has raised concerns about whether psoriasis medications also may increase the risk for SIB.7

We review research on the effects of psoriasis treatment on patients’ symptoms of depression and SIB, with a focus on recent analyses of depressive symptoms and SIB among patients with psoriasis who received brodalumab in clinical trials. Finally, we suggest approaches clinicians may consider when caring for patients with psoriasis who may be at risk for depression and SIB.

We reviewed research on the effects of biologic therapy for psoriasis on depression and SIB, with a primary focus on recent large meta-analyses. Published findings on the pattern of SIB in brodalumab clinical trials and effects of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety are summarized. The most recent evidence (January 2014–December 2018) regarding the mental health comorbidities of psoriasis was assessed using published English-language research data and review articles according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the following terms: depression, anxiety, suicide, suicidal ideation and behavior, SIB, brodalumab, or psoriasis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources. Implications for clinical care of patients with psoriasis are discussed based on expert recommendations and the authors’ clinical experience.

RESULTS

Effects of Psoriasis Treatment on Symptoms of Depression and Suicidality

Occurrences of attempted suicide and completed suicide have been reported during treatment with several psoriasis medications,7,9 raising concerns about whether these medications increase the risk for depression and SIB in an already vulnerable population. Wu and colleagues7 reviewed 11 studies published from 2006 to 2017 reporting the effects of medications for the treatment of psoriasis—adalimumab, apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab—on measures of depression and anxiety such as the Beck Depression Inventory, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 8. In each of the 11 studies, symptoms of depression improved after treatment, over time, or compared to placebo. Notably, the magnitude of improvement in symptoms of depression was not strongly linked to the magnitude of clinical improvement.7 Other recent studies have reported reductions in symptoms of depression with biologic therapies, including adalimumab, etanercept, guselkumab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab.14-21

With respect to suicidality, an analysis of publicly available data found low rates of completed and attempted suicides (point estimates of 0.0–0.15 per 100 patient-years) in clinical development programs of apremilast, brodalumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. Patient suicidality in these trials often occurred in the context of risk factors or stressors such as work, financial difficulties, depression, and substance abuse.7 In a detailed 2016 analysis of suicidal behaviors during clinical trials of apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and other investigational agents, Gooderham and colleagues9 concluded that the behaviors may have resulted from the disease or patients’ psychosocial status rather than from treatment and that treatment with biologics does not increase the risk for SIB. Improvements in symptoms of depression during treatment suggest the potential to improve patients’ psychiatric outcomes with biologic treatment.9

Evidence From Brodalumab Studies

Intensive efforts have been made to assess the effect of brodalumab, a fully human anti–IL-17RA monoclonal antibody shown to be efficacious in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, on symptoms of depression and to understand the incidence of SIB among patients receiving brodalumab in clinical trials.22-27

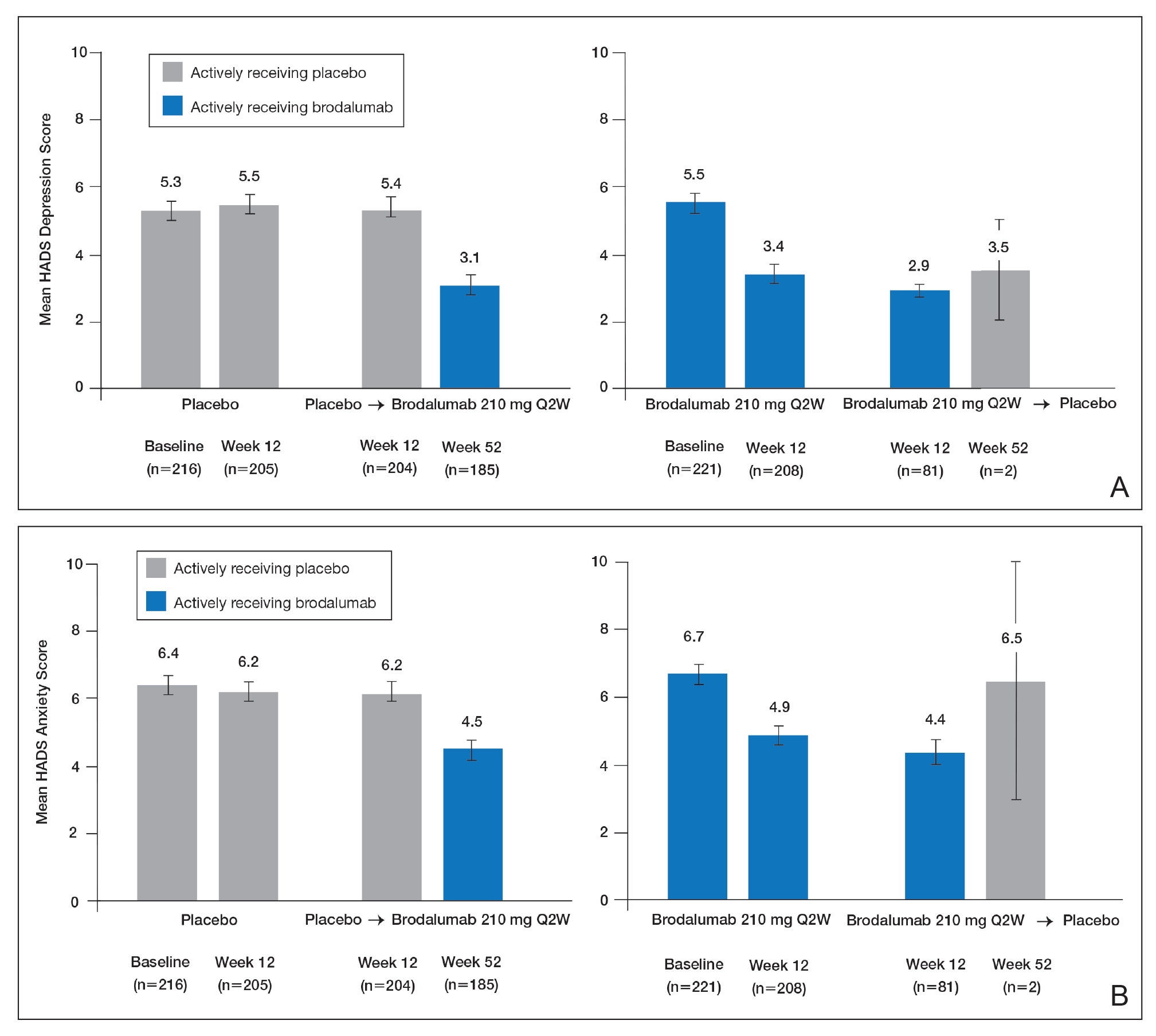

To examine the effects of brodalumab on symptoms of depression, the HADS questionnaire28 was administered to patients in 1 of 3 phase 3 clinical trials of brodalumab.23 A HADS score of 0 to 7 is considered normal, 8 to 10 is mild, 11 to 14 is moderate, and 15 to 21 is severe.23 The HADS questionnaire was administered to evaluate the presence and severity of depression and anxiety symptoms at baseline and at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 52.25 This scale was not used in the other 2 phase 3 studies of brodalumab because at the time those studies were initiated, there was no indication to include mental health screenings as part of the study protocol.

Patients were initially randomized to placebo (n=220), brodalumab 140 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W; n=219), or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W (the eventual approved dose; n=222) for 12 weeks.23 At week 12, patients initially randomized to placebo were switched to brodalumab through week 52. Patients initially randomized to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W were re-randomized to either placebo or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.23 Depression and anxiety were common at baseline. Based on HADS scores, depression occurred among 27% and 26% of patients randomized to brodalumab and placebo, respectively; anxiety occurred in 36% of patients in each group.22 Among patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W from baseline to week 12, HADS depression scores improved in 67% of patients and worsened in 19%. In contrast, the proportion of patients receiving placebo whose depression scores improved (45%) was similar to the proportion whose scores worsened (38%). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety scores also improved more often with brodalumab than with placebo.22

Furthermore, among patients who had moderate or severe depression or anxiety at baseline, a greater percentage experienced improvement with brodalumab than placebo.23 Among 30 patients with moderate to severe HADS depression scores at baseline who were treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, 22 (73%) improved by at least 1 depression category by week 12; in the placebo group, 10 of 22 (45%) improved. Among patients with moderate or severe anxiety scores, 28 of 42 patients (67%) treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W improved by at least 1 anxiety category compared to 8 of 27 (30%) placebo-treated patients.23

Over 52 weeks, HADS depression and anxiety scores continued to show a pattern of improvement among patients receiving brodalumab vs placebo.25 Among patients initially receiving placebo, mean HADS depression scores were unchanged from baseline (5.3) to week 12 (5.5). After patients were switched to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, there was a trend toward improvement between week 12 (5.4) and week 52 (3.1). Among patients initially treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, mean depression scores fell from baseline (5.5) to week 12 (3.4), then rose again between weeks 12 (2.9) and 52 (3.5) in patients switched to placebo (Figure, A). The pattern of findings was similar for HADS anxiety scores (Figure, B).25 Overall,

SIB in Studies of Brodalumab

In addition to assessing the effect of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with psoriasis, the brodalumab clinical trial program also tracked patterns of SIB among enrolled patients. In contrast with other clinical trials in which patients with a history of psychiatric disorders or substance abuse were excluded, clinical trials of brodalumab did not exclude patients with psychiatric disorders (eg, SIB, depression) and were therefore reflective of the real-world population of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.22

In a recently published, detailed analysis of psychiatric adverse events (AEs) in the brodalumab clinical trials, data related to SIB in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were analyzed from the placebo-controlled phases and open-label, long-term extensions of a placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial and from the previously mentioned 3 phase 3 clinical trials.22 From the initiation of the clinical trial program, AEs were monitored during all trials. In response to completed suicides during some studies, additional SIB evaluations were later added at the request of the US Food and Drug Administration, including the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the PHQ-8, and the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment, to independently adjudicate SIB events.22

In total, 4464 patients in the brodalumab clinical trials received at least 1 dose of brodalumab, and 4126 of these patients received at least 1 dose of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.22 Total exposure was 9174 patient-years of brodalumab, and mean exposure was 23 months. During the 52-week controlled phases of the clinical trials, 7 patients receiving brodalumab experienced any form of SIB event, representing a time-adjusted incidence rate of 0.20 events (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.41 events) per 100 patient-years of exposure. During the same 52-week period, patients receiving the comparator drug ustekinumab had an SIB rate of 0.60 events (95% CI, 0.12-1.74 events) per 100 patient-years, which was numerically higher than the rate with brodalumab. Inferential statistical analyses were not performed, but overlapping 95% CIs around these point estimates imply a similar level of SIB risk associated with each agent in these studies. During controlled and uncontrolled treatment periods in all studies, the SIB rate among brodalumab-treated patients was 0.37 events per 100 patient-years.22

Over all study phases, 3 completed suicides and 1 case adjudicated as indeterminate by the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment review board were reported.22 All occurred in men aged 39 to 59 years. Of 6 patients with an AE of suicide attempt, all patients had at least 1 SIB risk factor and 3 had a history of SIB. The rate of SIB events was greater in patients with a history of depression (1.42) or suicidality (3.21) compared to those without any history of depression or suicidality (0.21 and 0.20, respectively).22 An examination of the regions in which the brodalumab studies were conducted showed generally consistent SIB incidence rates: 0.52, 0.29, 0.77, and 0 events per 100 patient-years in North America, Europe, Australia, and Russia, respectively.24