User login

Dupilumab-Induced Facial Flushing After Alcohol Consumption

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

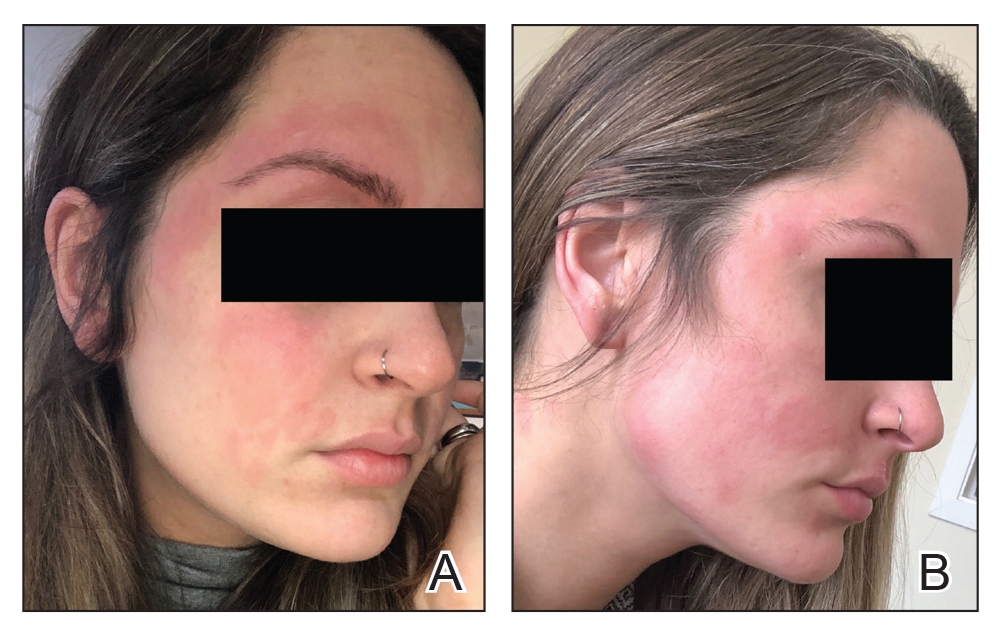

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Practice Points

- Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits the action of IL-4 and IL-13. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Facial flushing after alcohol consumption may be an emerging side effect of dupilumab.

- Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Depression and Suicidality in Psoriasis and Clinical Studies of Brodalumab: A Narrative Review

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that affects patients’ quality of life and social interactions.1 Several studies have shown a strong consistent association between psoriasis and depression as well as possible suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB).1-13 Notable findings from a 2018 review found depression prevalence ranged from 2.1% to 33.7% among patients with psoriasis vs 0% to 22.7% among unaffected patients.7 In a 2017 meta-analysis, Singh et al2 found increased odds of SIB (odds ratio [OR], 2.05), attempted suicide (OR, 1.32), and completed suicide (OR, 1.20) in patients with psoriasis compared to those without psoriasis. In 2018, Wu and colleagues7 reported that odds of SIB among patients with psoriasis ranged from 1.01 to 1.94 times those of patients without psoriasis, and SIB and suicide attempts were more common than in patients with other dermatologic conditions. Koo and colleagues1 reached similar conclusions. At the same time, the occurrence of attempted and completed suicides among patients in psoriasis clinical trials has raised concerns about whether psoriasis medications also may increase the risk for SIB.7

We review research on the effects of psoriasis treatment on patients’ symptoms of depression and SIB, with a focus on recent analyses of depressive symptoms and SIB among patients with psoriasis who received brodalumab in clinical trials. Finally, we suggest approaches clinicians may consider when caring for patients with psoriasis who may be at risk for depression and SIB.

We reviewed research on the effects of biologic therapy for psoriasis on depression and SIB, with a primary focus on recent large meta-analyses. Published findings on the pattern of SIB in brodalumab clinical trials and effects of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety are summarized. The most recent evidence (January 2014–December 2018) regarding the mental health comorbidities of psoriasis was assessed using published English-language research data and review articles according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the following terms: depression, anxiety, suicide, suicidal ideation and behavior, SIB, brodalumab, or psoriasis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources. Implications for clinical care of patients with psoriasis are discussed based on expert recommendations and the authors’ clinical experience.

RESULTS

Effects of Psoriasis Treatment on Symptoms of Depression and Suicidality

Occurrences of attempted suicide and completed suicide have been reported during treatment with several psoriasis medications,7,9 raising concerns about whether these medications increase the risk for depression and SIB in an already vulnerable population. Wu and colleagues7 reviewed 11 studies published from 2006 to 2017 reporting the effects of medications for the treatment of psoriasis—adalimumab, apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab—on measures of depression and anxiety such as the Beck Depression Inventory, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 8. In each of the 11 studies, symptoms of depression improved after treatment, over time, or compared to placebo. Notably, the magnitude of improvement in symptoms of depression was not strongly linked to the magnitude of clinical improvement.7 Other recent studies have reported reductions in symptoms of depression with biologic therapies, including adalimumab, etanercept, guselkumab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab.14-21

With respect to suicidality, an analysis of publicly available data found low rates of completed and attempted suicides (point estimates of 0.0–0.15 per 100 patient-years) in clinical development programs of apremilast, brodalumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. Patient suicidality in these trials often occurred in the context of risk factors or stressors such as work, financial difficulties, depression, and substance abuse.7 In a detailed 2016 analysis of suicidal behaviors during clinical trials of apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and other investigational agents, Gooderham and colleagues9 concluded that the behaviors may have resulted from the disease or patients’ psychosocial status rather than from treatment and that treatment with biologics does not increase the risk for SIB. Improvements in symptoms of depression during treatment suggest the potential to improve patients’ psychiatric outcomes with biologic treatment.9

Evidence From Brodalumab Studies

Intensive efforts have been made to assess the effect of brodalumab, a fully human anti–IL-17RA monoclonal antibody shown to be efficacious in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, on symptoms of depression and to understand the incidence of SIB among patients receiving brodalumab in clinical trials.22-27

To examine the effects of brodalumab on symptoms of depression, the HADS questionnaire28 was administered to patients in 1 of 3 phase 3 clinical trials of brodalumab.23 A HADS score of 0 to 7 is considered normal, 8 to 10 is mild, 11 to 14 is moderate, and 15 to 21 is severe.23 The HADS questionnaire was administered to evaluate the presence and severity of depression and anxiety symptoms at baseline and at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 52.25 This scale was not used in the other 2 phase 3 studies of brodalumab because at the time those studies were initiated, there was no indication to include mental health screenings as part of the study protocol.

Patients were initially randomized to placebo (n=220), brodalumab 140 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W; n=219), or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W (the eventual approved dose; n=222) for 12 weeks.23 At week 12, patients initially randomized to placebo were switched to brodalumab through week 52. Patients initially randomized to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W were re-randomized to either placebo or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.23 Depression and anxiety were common at baseline. Based on HADS scores, depression occurred among 27% and 26% of patients randomized to brodalumab and placebo, respectively; anxiety occurred in 36% of patients in each group.22 Among patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W from baseline to week 12, HADS depression scores improved in 67% of patients and worsened in 19%. In contrast, the proportion of patients receiving placebo whose depression scores improved (45%) was similar to the proportion whose scores worsened (38%). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety scores also improved more often with brodalumab than with placebo.22

Furthermore, among patients who had moderate or severe depression or anxiety at baseline, a greater percentage experienced improvement with brodalumab than placebo.23 Among 30 patients with moderate to severe HADS depression scores at baseline who were treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, 22 (73%) improved by at least 1 depression category by week 12; in the placebo group, 10 of 22 (45%) improved. Among patients with moderate or severe anxiety scores, 28 of 42 patients (67%) treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W improved by at least 1 anxiety category compared to 8 of 27 (30%) placebo-treated patients.23

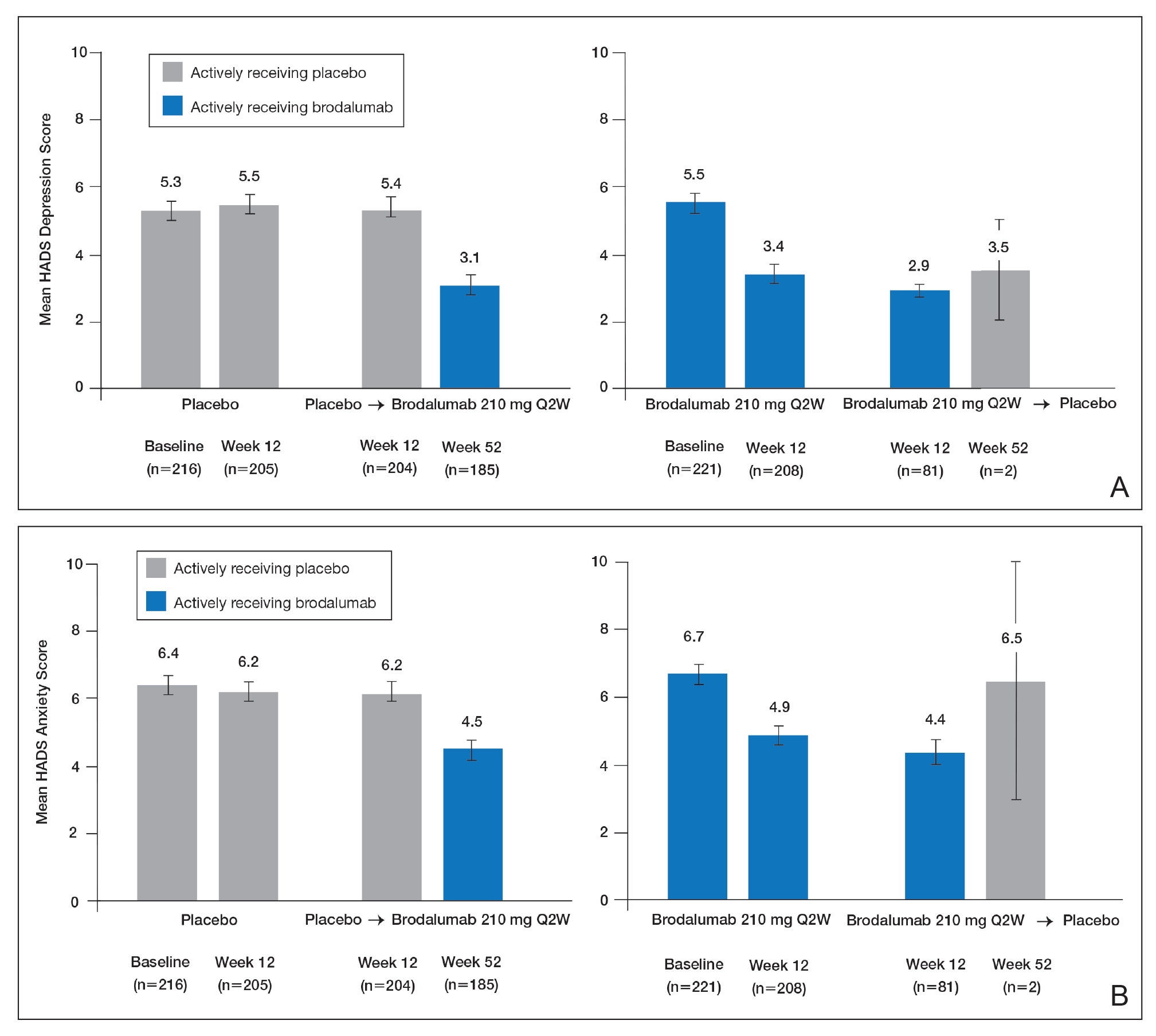

Over 52 weeks, HADS depression and anxiety scores continued to show a pattern of improvement among patients receiving brodalumab vs placebo.25 Among patients initially receiving placebo, mean HADS depression scores were unchanged from baseline (5.3) to week 12 (5.5). After patients were switched to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, there was a trend toward improvement between week 12 (5.4) and week 52 (3.1). Among patients initially treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, mean depression scores fell from baseline (5.5) to week 12 (3.4), then rose again between weeks 12 (2.9) and 52 (3.5) in patients switched to placebo (Figure, A). The pattern of findings was similar for HADS anxiety scores (Figure, B).25 Overall,

SIB in Studies of Brodalumab

In addition to assessing the effect of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with psoriasis, the brodalumab clinical trial program also tracked patterns of SIB among enrolled patients. In contrast with other clinical trials in which patients with a history of psychiatric disorders or substance abuse were excluded, clinical trials of brodalumab did not exclude patients with psychiatric disorders (eg, SIB, depression) and were therefore reflective of the real-world population of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.22

In a recently published, detailed analysis of psychiatric adverse events (AEs) in the brodalumab clinical trials, data related to SIB in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were analyzed from the placebo-controlled phases and open-label, long-term extensions of a placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial and from the previously mentioned 3 phase 3 clinical trials.22 From the initiation of the clinical trial program, AEs were monitored during all trials. In response to completed suicides during some studies, additional SIB evaluations were later added at the request of the US Food and Drug Administration, including the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the PHQ-8, and the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment, to independently adjudicate SIB events.22

In total, 4464 patients in the brodalumab clinical trials received at least 1 dose of brodalumab, and 4126 of these patients received at least 1 dose of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.22 Total exposure was 9174 patient-years of brodalumab, and mean exposure was 23 months. During the 52-week controlled phases of the clinical trials, 7 patients receiving brodalumab experienced any form of SIB event, representing a time-adjusted incidence rate of 0.20 events (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.41 events) per 100 patient-years of exposure. During the same 52-week period, patients receiving the comparator drug ustekinumab had an SIB rate of 0.60 events (95% CI, 0.12-1.74 events) per 100 patient-years, which was numerically higher than the rate with brodalumab. Inferential statistical analyses were not performed, but overlapping 95% CIs around these point estimates imply a similar level of SIB risk associated with each agent in these studies. During controlled and uncontrolled treatment periods in all studies, the SIB rate among brodalumab-treated patients was 0.37 events per 100 patient-years.22

Over all study phases, 3 completed suicides and 1 case adjudicated as indeterminate by the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment review board were reported.22 All occurred in men aged 39 to 59 years. Of 6 patients with an AE of suicide attempt, all patients had at least 1 SIB risk factor and 3 had a history of SIB. The rate of SIB events was greater in patients with a history of depression (1.42) or suicidality (3.21) compared to those without any history of depression or suicidality (0.21 and 0.20, respectively).22 An examination of the regions in which the brodalumab studies were conducted showed generally consistent SIB incidence rates: 0.52, 0.29, 0.77, and 0 events per 100 patient-years in North America, Europe, Australia, and Russia, respectively.24

As previously described, depression and other risk factors for SIB are prevalent among patients with psoriasis. In addition, the rate of suicide mortality has increased substantially over the last decade in the general population, particularly among middle-aged white men,29 who made up much of the brodalumab clinical trial population.22 Therefore, even without treatment, it would not be surprising that SIB events occurred during the brodalumab trials. Most patients with SIB events during the trials had a history of predisposing risk factors.22 Prescribing information for brodalumab in the United States includes a boxed warning advising physicians to be aware of the risk of SIB as well as a statement that a causal relationship between SIB and brodalumab treatment has not been established.27

Despite the boxed warning in the brodalumab package insert concerning suicidality, a causal relationship between brodalumab treatment and increased risk of SIB has not been firmly established.27 The US boxed warning is based on 3 completed suicides and 1 case adjudicated as indeterminate among more than 4000 patients who received at least 1 dose of brodalumab during global clinical trials (0.07% [3/4464]). Compliance in the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program is mandatory, and patient screening and counseling should not be minimized.27 The 3 completed suicides occurred in patients who reported a history of financial stressors, legal difficulties, or depression and anxiety, and they occurred at least 140 days after initiation of treatment with brodalumab, a chronology that does not support a strong association between brodalumab exposure and SIB.22 Taking into consideration the increased risk for depression among individuals with psoriasis and the details surrounding the 3 completed suicides, an evidence-based causal relationship between brodalumab and increased risk for suicidality cannot be concluded. However, physicians must assess risks and benefits of any therapy in the context of the individual patient’s preferences, risk factors, and response to treatment.

Dermatologists who are aware of the comorbidity between psoriasis and mood disorders play an important role in evaluating patients with psoriasis for psychiatric risk factors.30-32 The dermatologist should discuss with patients the relationship between psoriasis and depression, assess for any history of depression and SIB, and evaluate for signs and symptoms of depression and current SIB.33 Screening tools, including the HADS or the short, easily administered PHQ-234 or PHQ-4,35 can be used to assess whether patients have symptoms of depression.1,36,37 Patients at risk for depression or SIB should be referred to their primary care physician or a mental health care practitioner.37 Currently, there is a gap in knowledge in screening patients for psychiatric issues within the dermatology community33,38; however, health care providers can give support to help bridge this gap.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Amgen Inc. Medical writing support was provided under the direction of the authors by Lisa Baker, PhD, and Rebecca E. Slager, PhD, of MedThink SciCom (Cary, North Carolina) and funded by Ortho Dermatologics, a division of Bausch Health US, LLC.

- Koo J, Marangell LB, Nakamura M, et al. Depression and suicidality in psoriasis: review of the literature including the cytokine theory of depression. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1999-2009.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Chi CC, Chen TH, Wang SH, et al. Risk of suicidality in people with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:621-627.

- Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:984-991.

- Pompili M, Innamorati M, Trovarelli S, et al. Suicide risk and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with psoriasis. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:61-66.

- Pompili M, Innamorati M, Forte A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and suicidal ideation in psoriasis, melanoma and allergic disorders. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21:209-214.

- Wu JJ, Feldman SR, Koo J, et al. Epidemiology of mental health comorbidity in psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:487-495.

- Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, et al. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1542-1551.

- Gooderham M, Gavino-Velasco J, Clifford C, et al. A review of psoriasis, therapies, and suicide. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:293-303.

- Shah K, Mellars L, Changolkar A, et al. Real-world burden of comorbidities in US patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:287-292.e4.

- Cohen BE, Martires KJ, Ho RS. Psoriasis and the risk of depression in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:73-79.

- Wu JJ, Penfold RB, Primatesta P, et al. The risk of depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1168-1175.

- Pietrzak D, Pietrzak A, Krasowska D, et al. Depressiveness, measured with Beck Depression Inventory, in patients with psoriasis. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:229-234.

- Sator P. Safety and tolerability of adalimumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a review summarizing 15 years of real-life experience. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9:147-158.

- Wu CY, Chang YT, Juan CK, et al. Depression and insomnia in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis taking tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E3816.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Foley P, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab in subpopulations of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of the phase III VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 studies. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:132-139.

- Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong EMGJ, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:70-80.

- Griffiths CEM, Fava M, Miller AH, et al. Impact of ixekizumab treatment on depressive symptoms and systemic inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: an integrated analysis of three phase 3 clinical studies. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86:260-267.

- Salame N, Ehsani-Chimeh N, Armstrong AW. Comparison of mental health outcomes among adults with psoriasis on biologic versus oral therapies: a population-based study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:135-140.

- Strober BE, Langley RGB, Menter A, et al. No elevated risk for depression, anxiety or suicidality with secukinumab in a pooled analysis of data from 10 clinical studies in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:E105-E107.

- Kim SJ, Park MY, Pak K, et al. Improvement of depressive symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated with ustekinumab: an open label trial validated using Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Depression Rating scale measures and 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET). J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:761-768.

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Feldman SR, Harris S, Rastogi S, et al. Distribution of depression and suicidality in a psoriasis clinical trial population. Poster presented at: Winter Clinical Dermatology Conference; January 12-17, 2018; Lahaina, HI.

- Gooderham M, Feldman SR, Harris S, et al. Effects of brodalumab on anxiety and depression in patients with psoriasis: results from a phase 3, randomized, controlled clinical trial (AMAGINE-1). Poster presented at: 76th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; February 16-20, 2018; San Diego, CA.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Siliq (brodalumab)[package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Bausch Health US, LLC; 2017.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

- Hashim PW, Chen T, Lebwohl MG, et al. What lies beneath the face value of a box warning: a deeper look at brodalumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:S29-S34.

- Roubille C, Richer V, Starnino T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis: expert opinion of the Canadian Dermatology-Rheumatology Comorbidity Initiative. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:1767-1780.

- Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: implications for management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:393-403.

- Gupta MA, Pur DR, Vujcic B, et al. Suicidal behaviors in the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:302-311.

- Wu JJ. Contemporary management of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(21 suppl):S403-S416.

- Manea L, Gilbody S, Hewitt C, et al. Identifying depression with the PHQ-2: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:382-395.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613-621.

- Lamb RC, Matcham F, Turner MA, et al. Screening for anxiety and depression in people with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary referral setting. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1028-1034.

- Dauden E, Blasco AJ, Bonanad C, et al. Position statement for the management of comorbidities in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2058-2073.

- Moon HS, Mizara A, McBride SR. Psoriasis and psycho-dermatology. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2013;3:117-130.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that affects patients’ quality of life and social interactions.1 Several studies have shown a strong consistent association between psoriasis and depression as well as possible suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB).1-13 Notable findings from a 2018 review found depression prevalence ranged from 2.1% to 33.7% among patients with psoriasis vs 0% to 22.7% among unaffected patients.7 In a 2017 meta-analysis, Singh et al2 found increased odds of SIB (odds ratio [OR], 2.05), attempted suicide (OR, 1.32), and completed suicide (OR, 1.20) in patients with psoriasis compared to those without psoriasis. In 2018, Wu and colleagues7 reported that odds of SIB among patients with psoriasis ranged from 1.01 to 1.94 times those of patients without psoriasis, and SIB and suicide attempts were more common than in patients with other dermatologic conditions. Koo and colleagues1 reached similar conclusions. At the same time, the occurrence of attempted and completed suicides among patients in psoriasis clinical trials has raised concerns about whether psoriasis medications also may increase the risk for SIB.7

We review research on the effects of psoriasis treatment on patients’ symptoms of depression and SIB, with a focus on recent analyses of depressive symptoms and SIB among patients with psoriasis who received brodalumab in clinical trials. Finally, we suggest approaches clinicians may consider when caring for patients with psoriasis who may be at risk for depression and SIB.

We reviewed research on the effects of biologic therapy for psoriasis on depression and SIB, with a primary focus on recent large meta-analyses. Published findings on the pattern of SIB in brodalumab clinical trials and effects of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety are summarized. The most recent evidence (January 2014–December 2018) regarding the mental health comorbidities of psoriasis was assessed using published English-language research data and review articles according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the following terms: depression, anxiety, suicide, suicidal ideation and behavior, SIB, brodalumab, or psoriasis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources. Implications for clinical care of patients with psoriasis are discussed based on expert recommendations and the authors’ clinical experience.

RESULTS

Effects of Psoriasis Treatment on Symptoms of Depression and Suicidality

Occurrences of attempted suicide and completed suicide have been reported during treatment with several psoriasis medications,7,9 raising concerns about whether these medications increase the risk for depression and SIB in an already vulnerable population. Wu and colleagues7 reviewed 11 studies published from 2006 to 2017 reporting the effects of medications for the treatment of psoriasis—adalimumab, apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab—on measures of depression and anxiety such as the Beck Depression Inventory, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 8. In each of the 11 studies, symptoms of depression improved after treatment, over time, or compared to placebo. Notably, the magnitude of improvement in symptoms of depression was not strongly linked to the magnitude of clinical improvement.7 Other recent studies have reported reductions in symptoms of depression with biologic therapies, including adalimumab, etanercept, guselkumab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab.14-21

With respect to suicidality, an analysis of publicly available data found low rates of completed and attempted suicides (point estimates of 0.0–0.15 per 100 patient-years) in clinical development programs of apremilast, brodalumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. Patient suicidality in these trials often occurred in the context of risk factors or stressors such as work, financial difficulties, depression, and substance abuse.7 In a detailed 2016 analysis of suicidal behaviors during clinical trials of apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and other investigational agents, Gooderham and colleagues9 concluded that the behaviors may have resulted from the disease or patients’ psychosocial status rather than from treatment and that treatment with biologics does not increase the risk for SIB. Improvements in symptoms of depression during treatment suggest the potential to improve patients’ psychiatric outcomes with biologic treatment.9

Evidence From Brodalumab Studies

Intensive efforts have been made to assess the effect of brodalumab, a fully human anti–IL-17RA monoclonal antibody shown to be efficacious in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, on symptoms of depression and to understand the incidence of SIB among patients receiving brodalumab in clinical trials.22-27

To examine the effects of brodalumab on symptoms of depression, the HADS questionnaire28 was administered to patients in 1 of 3 phase 3 clinical trials of brodalumab.23 A HADS score of 0 to 7 is considered normal, 8 to 10 is mild, 11 to 14 is moderate, and 15 to 21 is severe.23 The HADS questionnaire was administered to evaluate the presence and severity of depression and anxiety symptoms at baseline and at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 52.25 This scale was not used in the other 2 phase 3 studies of brodalumab because at the time those studies were initiated, there was no indication to include mental health screenings as part of the study protocol.

Patients were initially randomized to placebo (n=220), brodalumab 140 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W; n=219), or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W (the eventual approved dose; n=222) for 12 weeks.23 At week 12, patients initially randomized to placebo were switched to brodalumab through week 52. Patients initially randomized to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W were re-randomized to either placebo or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.23 Depression and anxiety were common at baseline. Based on HADS scores, depression occurred among 27% and 26% of patients randomized to brodalumab and placebo, respectively; anxiety occurred in 36% of patients in each group.22 Among patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W from baseline to week 12, HADS depression scores improved in 67% of patients and worsened in 19%. In contrast, the proportion of patients receiving placebo whose depression scores improved (45%) was similar to the proportion whose scores worsened (38%). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety scores also improved more often with brodalumab than with placebo.22

Furthermore, among patients who had moderate or severe depression or anxiety at baseline, a greater percentage experienced improvement with brodalumab than placebo.23 Among 30 patients with moderate to severe HADS depression scores at baseline who were treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, 22 (73%) improved by at least 1 depression category by week 12; in the placebo group, 10 of 22 (45%) improved. Among patients with moderate or severe anxiety scores, 28 of 42 patients (67%) treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W improved by at least 1 anxiety category compared to 8 of 27 (30%) placebo-treated patients.23

Over 52 weeks, HADS depression and anxiety scores continued to show a pattern of improvement among patients receiving brodalumab vs placebo.25 Among patients initially receiving placebo, mean HADS depression scores were unchanged from baseline (5.3) to week 12 (5.5). After patients were switched to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, there was a trend toward improvement between week 12 (5.4) and week 52 (3.1). Among patients initially treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, mean depression scores fell from baseline (5.5) to week 12 (3.4), then rose again between weeks 12 (2.9) and 52 (3.5) in patients switched to placebo (Figure, A). The pattern of findings was similar for HADS anxiety scores (Figure, B).25 Overall,

SIB in Studies of Brodalumab

In addition to assessing the effect of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with psoriasis, the brodalumab clinical trial program also tracked patterns of SIB among enrolled patients. In contrast with other clinical trials in which patients with a history of psychiatric disorders or substance abuse were excluded, clinical trials of brodalumab did not exclude patients with psychiatric disorders (eg, SIB, depression) and were therefore reflective of the real-world population of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.22

In a recently published, detailed analysis of psychiatric adverse events (AEs) in the brodalumab clinical trials, data related to SIB in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were analyzed from the placebo-controlled phases and open-label, long-term extensions of a placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial and from the previously mentioned 3 phase 3 clinical trials.22 From the initiation of the clinical trial program, AEs were monitored during all trials. In response to completed suicides during some studies, additional SIB evaluations were later added at the request of the US Food and Drug Administration, including the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the PHQ-8, and the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment, to independently adjudicate SIB events.22

In total, 4464 patients in the brodalumab clinical trials received at least 1 dose of brodalumab, and 4126 of these patients received at least 1 dose of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.22 Total exposure was 9174 patient-years of brodalumab, and mean exposure was 23 months. During the 52-week controlled phases of the clinical trials, 7 patients receiving brodalumab experienced any form of SIB event, representing a time-adjusted incidence rate of 0.20 events (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.41 events) per 100 patient-years of exposure. During the same 52-week period, patients receiving the comparator drug ustekinumab had an SIB rate of 0.60 events (95% CI, 0.12-1.74 events) per 100 patient-years, which was numerically higher than the rate with brodalumab. Inferential statistical analyses were not performed, but overlapping 95% CIs around these point estimates imply a similar level of SIB risk associated with each agent in these studies. During controlled and uncontrolled treatment periods in all studies, the SIB rate among brodalumab-treated patients was 0.37 events per 100 patient-years.22

Over all study phases, 3 completed suicides and 1 case adjudicated as indeterminate by the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment review board were reported.22 All occurred in men aged 39 to 59 years. Of 6 patients with an AE of suicide attempt, all patients had at least 1 SIB risk factor and 3 had a history of SIB. The rate of SIB events was greater in patients with a history of depression (1.42) or suicidality (3.21) compared to those without any history of depression or suicidality (0.21 and 0.20, respectively).22 An examination of the regions in which the brodalumab studies were conducted showed generally consistent SIB incidence rates: 0.52, 0.29, 0.77, and 0 events per 100 patient-years in North America, Europe, Australia, and Russia, respectively.24

As previously described, depression and other risk factors for SIB are prevalent among patients with psoriasis. In addition, the rate of suicide mortality has increased substantially over the last decade in the general population, particularly among middle-aged white men,29 who made up much of the brodalumab clinical trial population.22 Therefore, even without treatment, it would not be surprising that SIB events occurred during the brodalumab trials. Most patients with SIB events during the trials had a history of predisposing risk factors.22 Prescribing information for brodalumab in the United States includes a boxed warning advising physicians to be aware of the risk of SIB as well as a statement that a causal relationship between SIB and brodalumab treatment has not been established.27

Despite the boxed warning in the brodalumab package insert concerning suicidality, a causal relationship between brodalumab treatment and increased risk of SIB has not been firmly established.27 The US boxed warning is based on 3 completed suicides and 1 case adjudicated as indeterminate among more than 4000 patients who received at least 1 dose of brodalumab during global clinical trials (0.07% [3/4464]). Compliance in the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program is mandatory, and patient screening and counseling should not be minimized.27 The 3 completed suicides occurred in patients who reported a history of financial stressors, legal difficulties, or depression and anxiety, and they occurred at least 140 days after initiation of treatment with brodalumab, a chronology that does not support a strong association between brodalumab exposure and SIB.22 Taking into consideration the increased risk for depression among individuals with psoriasis and the details surrounding the 3 completed suicides, an evidence-based causal relationship between brodalumab and increased risk for suicidality cannot be concluded. However, physicians must assess risks and benefits of any therapy in the context of the individual patient’s preferences, risk factors, and response to treatment.

Dermatologists who are aware of the comorbidity between psoriasis and mood disorders play an important role in evaluating patients with psoriasis for psychiatric risk factors.30-32 The dermatologist should discuss with patients the relationship between psoriasis and depression, assess for any history of depression and SIB, and evaluate for signs and symptoms of depression and current SIB.33 Screening tools, including the HADS or the short, easily administered PHQ-234 or PHQ-4,35 can be used to assess whether patients have symptoms of depression.1,36,37 Patients at risk for depression or SIB should be referred to their primary care physician or a mental health care practitioner.37 Currently, there is a gap in knowledge in screening patients for psychiatric issues within the dermatology community33,38; however, health care providers can give support to help bridge this gap.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Amgen Inc. Medical writing support was provided under the direction of the authors by Lisa Baker, PhD, and Rebecca E. Slager, PhD, of MedThink SciCom (Cary, North Carolina) and funded by Ortho Dermatologics, a division of Bausch Health US, LLC.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that affects patients’ quality of life and social interactions.1 Several studies have shown a strong consistent association between psoriasis and depression as well as possible suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB).1-13 Notable findings from a 2018 review found depression prevalence ranged from 2.1% to 33.7% among patients with psoriasis vs 0% to 22.7% among unaffected patients.7 In a 2017 meta-analysis, Singh et al2 found increased odds of SIB (odds ratio [OR], 2.05), attempted suicide (OR, 1.32), and completed suicide (OR, 1.20) in patients with psoriasis compared to those without psoriasis. In 2018, Wu and colleagues7 reported that odds of SIB among patients with psoriasis ranged from 1.01 to 1.94 times those of patients without psoriasis, and SIB and suicide attempts were more common than in patients with other dermatologic conditions. Koo and colleagues1 reached similar conclusions. At the same time, the occurrence of attempted and completed suicides among patients in psoriasis clinical trials has raised concerns about whether psoriasis medications also may increase the risk for SIB.7

We review research on the effects of psoriasis treatment on patients’ symptoms of depression and SIB, with a focus on recent analyses of depressive symptoms and SIB among patients with psoriasis who received brodalumab in clinical trials. Finally, we suggest approaches clinicians may consider when caring for patients with psoriasis who may be at risk for depression and SIB.

We reviewed research on the effects of biologic therapy for psoriasis on depression and SIB, with a primary focus on recent large meta-analyses. Published findings on the pattern of SIB in brodalumab clinical trials and effects of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety are summarized. The most recent evidence (January 2014–December 2018) regarding the mental health comorbidities of psoriasis was assessed using published English-language research data and review articles according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the following terms: depression, anxiety, suicide, suicidal ideation and behavior, SIB, brodalumab, or psoriasis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources. Implications for clinical care of patients with psoriasis are discussed based on expert recommendations and the authors’ clinical experience.

RESULTS

Effects of Psoriasis Treatment on Symptoms of Depression and Suicidality

Occurrences of attempted suicide and completed suicide have been reported during treatment with several psoriasis medications,7,9 raising concerns about whether these medications increase the risk for depression and SIB in an already vulnerable population. Wu and colleagues7 reviewed 11 studies published from 2006 to 2017 reporting the effects of medications for the treatment of psoriasis—adalimumab, apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab—on measures of depression and anxiety such as the Beck Depression Inventory, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 8. In each of the 11 studies, symptoms of depression improved after treatment, over time, or compared to placebo. Notably, the magnitude of improvement in symptoms of depression was not strongly linked to the magnitude of clinical improvement.7 Other recent studies have reported reductions in symptoms of depression with biologic therapies, including adalimumab, etanercept, guselkumab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab.14-21

With respect to suicidality, an analysis of publicly available data found low rates of completed and attempted suicides (point estimates of 0.0–0.15 per 100 patient-years) in clinical development programs of apremilast, brodalumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. Patient suicidality in these trials often occurred in the context of risk factors or stressors such as work, financial difficulties, depression, and substance abuse.7 In a detailed 2016 analysis of suicidal behaviors during clinical trials of apremilast, brodalumab, etanercept, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and other investigational agents, Gooderham and colleagues9 concluded that the behaviors may have resulted from the disease or patients’ psychosocial status rather than from treatment and that treatment with biologics does not increase the risk for SIB. Improvements in symptoms of depression during treatment suggest the potential to improve patients’ psychiatric outcomes with biologic treatment.9

Evidence From Brodalumab Studies

Intensive efforts have been made to assess the effect of brodalumab, a fully human anti–IL-17RA monoclonal antibody shown to be efficacious in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, on symptoms of depression and to understand the incidence of SIB among patients receiving brodalumab in clinical trials.22-27

To examine the effects of brodalumab on symptoms of depression, the HADS questionnaire28 was administered to patients in 1 of 3 phase 3 clinical trials of brodalumab.23 A HADS score of 0 to 7 is considered normal, 8 to 10 is mild, 11 to 14 is moderate, and 15 to 21 is severe.23 The HADS questionnaire was administered to evaluate the presence and severity of depression and anxiety symptoms at baseline and at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 52.25 This scale was not used in the other 2 phase 3 studies of brodalumab because at the time those studies were initiated, there was no indication to include mental health screenings as part of the study protocol.

Patients were initially randomized to placebo (n=220), brodalumab 140 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W; n=219), or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W (the eventual approved dose; n=222) for 12 weeks.23 At week 12, patients initially randomized to placebo were switched to brodalumab through week 52. Patients initially randomized to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W were re-randomized to either placebo or brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.23 Depression and anxiety were common at baseline. Based on HADS scores, depression occurred among 27% and 26% of patients randomized to brodalumab and placebo, respectively; anxiety occurred in 36% of patients in each group.22 Among patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W from baseline to week 12, HADS depression scores improved in 67% of patients and worsened in 19%. In contrast, the proportion of patients receiving placebo whose depression scores improved (45%) was similar to the proportion whose scores worsened (38%). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety scores also improved more often with brodalumab than with placebo.22

Furthermore, among patients who had moderate or severe depression or anxiety at baseline, a greater percentage experienced improvement with brodalumab than placebo.23 Among 30 patients with moderate to severe HADS depression scores at baseline who were treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, 22 (73%) improved by at least 1 depression category by week 12; in the placebo group, 10 of 22 (45%) improved. Among patients with moderate or severe anxiety scores, 28 of 42 patients (67%) treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W improved by at least 1 anxiety category compared to 8 of 27 (30%) placebo-treated patients.23

Over 52 weeks, HADS depression and anxiety scores continued to show a pattern of improvement among patients receiving brodalumab vs placebo.25 Among patients initially receiving placebo, mean HADS depression scores were unchanged from baseline (5.3) to week 12 (5.5). After patients were switched to brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, there was a trend toward improvement between week 12 (5.4) and week 52 (3.1). Among patients initially treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, mean depression scores fell from baseline (5.5) to week 12 (3.4), then rose again between weeks 12 (2.9) and 52 (3.5) in patients switched to placebo (Figure, A). The pattern of findings was similar for HADS anxiety scores (Figure, B).25 Overall,

SIB in Studies of Brodalumab

In addition to assessing the effect of brodalumab treatment on symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with psoriasis, the brodalumab clinical trial program also tracked patterns of SIB among enrolled patients. In contrast with other clinical trials in which patients with a history of psychiatric disorders or substance abuse were excluded, clinical trials of brodalumab did not exclude patients with psychiatric disorders (eg, SIB, depression) and were therefore reflective of the real-world population of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.22

In a recently published, detailed analysis of psychiatric adverse events (AEs) in the brodalumab clinical trials, data related to SIB in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were analyzed from the placebo-controlled phases and open-label, long-term extensions of a placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial and from the previously mentioned 3 phase 3 clinical trials.22 From the initiation of the clinical trial program, AEs were monitored during all trials. In response to completed suicides during some studies, additional SIB evaluations were later added at the request of the US Food and Drug Administration, including the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the PHQ-8, and the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment, to independently adjudicate SIB events.22

In total, 4464 patients in the brodalumab clinical trials received at least 1 dose of brodalumab, and 4126 of these patients received at least 1 dose of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W.22 Total exposure was 9174 patient-years of brodalumab, and mean exposure was 23 months. During the 52-week controlled phases of the clinical trials, 7 patients receiving brodalumab experienced any form of SIB event, representing a time-adjusted incidence rate of 0.20 events (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.41 events) per 100 patient-years of exposure. During the same 52-week period, patients receiving the comparator drug ustekinumab had an SIB rate of 0.60 events (95% CI, 0.12-1.74 events) per 100 patient-years, which was numerically higher than the rate with brodalumab. Inferential statistical analyses were not performed, but overlapping 95% CIs around these point estimates imply a similar level of SIB risk associated with each agent in these studies. During controlled and uncontrolled treatment periods in all studies, the SIB rate among brodalumab-treated patients was 0.37 events per 100 patient-years.22

Over all study phases, 3 completed suicides and 1 case adjudicated as indeterminate by the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment review board were reported.22 All occurred in men aged 39 to 59 years. Of 6 patients with an AE of suicide attempt, all patients had at least 1 SIB risk factor and 3 had a history of SIB. The rate of SIB events was greater in patients with a history of depression (1.42) or suicidality (3.21) compared to those without any history of depression or suicidality (0.21 and 0.20, respectively).22 An examination of the regions in which the brodalumab studies were conducted showed generally consistent SIB incidence rates: 0.52, 0.29, 0.77, and 0 events per 100 patient-years in North America, Europe, Australia, and Russia, respectively.24

As previously described, depression and other risk factors for SIB are prevalent among patients with psoriasis. In addition, the rate of suicide mortality has increased substantially over the last decade in the general population, particularly among middle-aged white men,29 who made up much of the brodalumab clinical trial population.22 Therefore, even without treatment, it would not be surprising that SIB events occurred during the brodalumab trials. Most patients with SIB events during the trials had a history of predisposing risk factors.22 Prescribing information for brodalumab in the United States includes a boxed warning advising physicians to be aware of the risk of SIB as well as a statement that a causal relationship between SIB and brodalumab treatment has not been established.27

Despite the boxed warning in the brodalumab package insert concerning suicidality, a causal relationship between brodalumab treatment and increased risk of SIB has not been firmly established.27 The US boxed warning is based on 3 completed suicides and 1 case adjudicated as indeterminate among more than 4000 patients who received at least 1 dose of brodalumab during global clinical trials (0.07% [3/4464]). Compliance in the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program is mandatory, and patient screening and counseling should not be minimized.27 The 3 completed suicides occurred in patients who reported a history of financial stressors, legal difficulties, or depression and anxiety, and they occurred at least 140 days after initiation of treatment with brodalumab, a chronology that does not support a strong association between brodalumab exposure and SIB.22 Taking into consideration the increased risk for depression among individuals with psoriasis and the details surrounding the 3 completed suicides, an evidence-based causal relationship between brodalumab and increased risk for suicidality cannot be concluded. However, physicians must assess risks and benefits of any therapy in the context of the individual patient’s preferences, risk factors, and response to treatment.

Dermatologists who are aware of the comorbidity between psoriasis and mood disorders play an important role in evaluating patients with psoriasis for psychiatric risk factors.30-32 The dermatologist should discuss with patients the relationship between psoriasis and depression, assess for any history of depression and SIB, and evaluate for signs and symptoms of depression and current SIB.33 Screening tools, including the HADS or the short, easily administered PHQ-234 or PHQ-4,35 can be used to assess whether patients have symptoms of depression.1,36,37 Patients at risk for depression or SIB should be referred to their primary care physician or a mental health care practitioner.37 Currently, there is a gap in knowledge in screening patients for psychiatric issues within the dermatology community33,38; however, health care providers can give support to help bridge this gap.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Amgen Inc. Medical writing support was provided under the direction of the authors by Lisa Baker, PhD, and Rebecca E. Slager, PhD, of MedThink SciCom (Cary, North Carolina) and funded by Ortho Dermatologics, a division of Bausch Health US, LLC.

- Koo J, Marangell LB, Nakamura M, et al. Depression and suicidality in psoriasis: review of the literature including the cytokine theory of depression. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1999-2009.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Chi CC, Chen TH, Wang SH, et al. Risk of suicidality in people with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:621-627.

- Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:984-991.

- Pompili M, Innamorati M, Trovarelli S, et al. Suicide risk and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with psoriasis. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:61-66.

- Pompili M, Innamorati M, Forte A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and suicidal ideation in psoriasis, melanoma and allergic disorders. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21:209-214.

- Wu JJ, Feldman SR, Koo J, et al. Epidemiology of mental health comorbidity in psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:487-495.

- Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, et al. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1542-1551.

- Gooderham M, Gavino-Velasco J, Clifford C, et al. A review of psoriasis, therapies, and suicide. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:293-303.

- Shah K, Mellars L, Changolkar A, et al. Real-world burden of comorbidities in US patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:287-292.e4.

- Cohen BE, Martires KJ, Ho RS. Psoriasis and the risk of depression in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:73-79.

- Wu JJ, Penfold RB, Primatesta P, et al. The risk of depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1168-1175.

- Pietrzak D, Pietrzak A, Krasowska D, et al. Depressiveness, measured with Beck Depression Inventory, in patients with psoriasis. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:229-234.

- Sator P. Safety and tolerability of adalimumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a review summarizing 15 years of real-life experience. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9:147-158.

- Wu CY, Chang YT, Juan CK, et al. Depression and insomnia in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis taking tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E3816.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Foley P, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab in subpopulations of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of the phase III VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 studies. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:132-139.

- Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong EMGJ, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:70-80.

- Griffiths CEM, Fava M, Miller AH, et al. Impact of ixekizumab treatment on depressive symptoms and systemic inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: an integrated analysis of three phase 3 clinical studies. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86:260-267.

- Salame N, Ehsani-Chimeh N, Armstrong AW. Comparison of mental health outcomes among adults with psoriasis on biologic versus oral therapies: a population-based study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:135-140.

- Strober BE, Langley RGB, Menter A, et al. No elevated risk for depression, anxiety or suicidality with secukinumab in a pooled analysis of data from 10 clinical studies in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:E105-E107.

- Kim SJ, Park MY, Pak K, et al. Improvement of depressive symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated with ustekinumab: an open label trial validated using Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Depression Rating scale measures and 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET). J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:761-768.

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Feldman SR, Harris S, Rastogi S, et al. Distribution of depression and suicidality in a psoriasis clinical trial population. Poster presented at: Winter Clinical Dermatology Conference; January 12-17, 2018; Lahaina, HI.

- Gooderham M, Feldman SR, Harris S, et al. Effects of brodalumab on anxiety and depression in patients with psoriasis: results from a phase 3, randomized, controlled clinical trial (AMAGINE-1). Poster presented at: 76th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; February 16-20, 2018; San Diego, CA.