User login

Hemorrhagic Crescent Sign in Pseudocellulitis

To the Editor:

Cellulitis is the most common reason for skin-related hospital admissions.1 Despite its frequency, it is suspected that many cases of cellulitis are misdiagnosed as other etiologies presenting with similar symptoms such as a ruptured Baker cyst. These cysts are located behind the knee and can present with calf pain, peripheral edema, and erythema when ruptured. Symptoms of a ruptured Baker cyst can be indistinguishable from cellulitis as well as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), both manifesting with lower extremity pain, swelling, and erythema, making diagnosis challenging.2 The hemorrhagic crescent sign—a crescent of ecchymosis distal to the medial malleolus and on the foot that results from synovial injury or rupture—can be a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate between the causes of acute swelling and pain of the leg.2 When observed, the hemorrhagic crescent sign supports testing for synovial pathology at the knee.

A 63-year-old man presented to an outside hospital for evaluation of a fever (temperature, 101 °F [38.3 °C]), as well as pain, edema, and erythema of the right lower leg of 2 days’ duration. He had a history of leg cellulitis, gout, diabetes mellitus, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy. On admission, he was found to have elevated C-reactive protein (45 mg/L [reference range, <8 mg/L]) and mild leukocytosis (13,500 cells/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000 cells/μL]). A venous duplex scan did not demonstrate signs of thrombosis. Antibiotic therapy was started for suspected cellulitis including levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and linezolid. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, the patient continued to be febrile and experienced progressive erythema and swelling of the right lower leg, at which point he was transferred to our institution. A new antibiotic regimen of vancomycin, cefepime, and clindamycin was started and showed no improvement, after which dermatology was consulted.

Physical examination revealed unilateral edema and calor of the right lower leg with a demarcated erythematous rash extending to the level of the knee. Furthermore, a hemorrhagic crescent sign was present below the right medial malleolus (Figure). The popliteal fossa was supple, though the patient was adamant that he had a Baker cyst. Punch biopsies demonstrated epidermal spongiosis and extensive edema with perivascular inflammation. No organisms were found by stain and culture. Ultrasound records confirmed a Baker cyst present at least 4 months prior; however, a repeat ultrasound showed resolution. A diagnosis of pseudocellulitis secondary to Baker cyst rupture was made, and corticosteroids were started, resulting in marked reduction in erythema and edema of the lower leg and hospital discharge.

This case highlights the importance of early involvement of dermatology when cellulitis is suspected. A study of 635 patients in the United Kingdom referred to dermatology for lower limb cellulitis found that 210 (33%) patients did not have cellulitis and only 18 (3%) required hospital admission.3 Dermatology consultations have been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory skin disease by decreasing length of stay and reducing readmissions.4

Our patient had several risk factors for cellulitis, including obesity, lymphedema, and chronic kidney disease, in addition to having fevers and unilateral involvement. However, failure of symptoms to improve with broad-spectrum antibiotics made a diagnosis of cellulitis less likely. In this case, a severe immune response to the ruptured Baker cyst mimicked the presentation of cellulitis.

Ruptured Baker cysts have been reported to cause acute leg swelling, mimicking the symptoms of cellulitis or DVT.2,5 The presence of a hemorrhagic crescent sign can be a useful diagnostic tool, as in our patient, because it has been reported as an indication of synovial injury or rupture, supporting the exclusion of cellulitis or DVT when it is observed.6 Prior reports have observed ecchymosis on the foot in as little as 1 day after the onset of calf swelling and at the lateral malleolus 3 days after the onset of calf swelling.5

Following suspicion of a ruptured Baker cyst causing pseudocellulitis, an ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography shows a large hypoechoic space behind the calf muscles, which is pathognomonic of a ruptured Baker cyst.7

In conclusion, when a hemorrhagic crescent sign is observed, one should be suspicious for a ruptured Baker cyst or other synovial pathology as an etiology of pseudocellulitis. Early recognition of the hemorrhagic crescent sign can help rule out cellulitis and DVT, thereby reducing the amount of intravenous antibiotic prescribed, decreasing the length of hospital stay, and reducing readmission.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.7.726

- Von Schroeder HP, Ameli FM, Piazza D, et al. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causes ecchymosis of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:316-317.

- Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1326-1328.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;53:523-528.

- Dunlop D, Parker PJ, Keating JF. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causing posterior compartment syndrome. Injury. 1997;28:561-562.

- Kraag G, Thevathasan EM, Gordon DA, et al. The hemorrhagic crescent sign of acute synovial rupture. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:477-478.

- Sato O, Kondoh K, Iyori K, et al. Midcalf ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ruptured Baker’s cysts. Surg Today. 2001;31:410-413. doi:10.1007/s005950170131

To the Editor:

Cellulitis is the most common reason for skin-related hospital admissions.1 Despite its frequency, it is suspected that many cases of cellulitis are misdiagnosed as other etiologies presenting with similar symptoms such as a ruptured Baker cyst. These cysts are located behind the knee and can present with calf pain, peripheral edema, and erythema when ruptured. Symptoms of a ruptured Baker cyst can be indistinguishable from cellulitis as well as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), both manifesting with lower extremity pain, swelling, and erythema, making diagnosis challenging.2 The hemorrhagic crescent sign—a crescent of ecchymosis distal to the medial malleolus and on the foot that results from synovial injury or rupture—can be a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate between the causes of acute swelling and pain of the leg.2 When observed, the hemorrhagic crescent sign supports testing for synovial pathology at the knee.

A 63-year-old man presented to an outside hospital for evaluation of a fever (temperature, 101 °F [38.3 °C]), as well as pain, edema, and erythema of the right lower leg of 2 days’ duration. He had a history of leg cellulitis, gout, diabetes mellitus, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy. On admission, he was found to have elevated C-reactive protein (45 mg/L [reference range, <8 mg/L]) and mild leukocytosis (13,500 cells/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000 cells/μL]). A venous duplex scan did not demonstrate signs of thrombosis. Antibiotic therapy was started for suspected cellulitis including levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and linezolid. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, the patient continued to be febrile and experienced progressive erythema and swelling of the right lower leg, at which point he was transferred to our institution. A new antibiotic regimen of vancomycin, cefepime, and clindamycin was started and showed no improvement, after which dermatology was consulted.

Physical examination revealed unilateral edema and calor of the right lower leg with a demarcated erythematous rash extending to the level of the knee. Furthermore, a hemorrhagic crescent sign was present below the right medial malleolus (Figure). The popliteal fossa was supple, though the patient was adamant that he had a Baker cyst. Punch biopsies demonstrated epidermal spongiosis and extensive edema with perivascular inflammation. No organisms were found by stain and culture. Ultrasound records confirmed a Baker cyst present at least 4 months prior; however, a repeat ultrasound showed resolution. A diagnosis of pseudocellulitis secondary to Baker cyst rupture was made, and corticosteroids were started, resulting in marked reduction in erythema and edema of the lower leg and hospital discharge.

This case highlights the importance of early involvement of dermatology when cellulitis is suspected. A study of 635 patients in the United Kingdom referred to dermatology for lower limb cellulitis found that 210 (33%) patients did not have cellulitis and only 18 (3%) required hospital admission.3 Dermatology consultations have been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory skin disease by decreasing length of stay and reducing readmissions.4

Our patient had several risk factors for cellulitis, including obesity, lymphedema, and chronic kidney disease, in addition to having fevers and unilateral involvement. However, failure of symptoms to improve with broad-spectrum antibiotics made a diagnosis of cellulitis less likely. In this case, a severe immune response to the ruptured Baker cyst mimicked the presentation of cellulitis.

Ruptured Baker cysts have been reported to cause acute leg swelling, mimicking the symptoms of cellulitis or DVT.2,5 The presence of a hemorrhagic crescent sign can be a useful diagnostic tool, as in our patient, because it has been reported as an indication of synovial injury or rupture, supporting the exclusion of cellulitis or DVT when it is observed.6 Prior reports have observed ecchymosis on the foot in as little as 1 day after the onset of calf swelling and at the lateral malleolus 3 days after the onset of calf swelling.5

Following suspicion of a ruptured Baker cyst causing pseudocellulitis, an ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography shows a large hypoechoic space behind the calf muscles, which is pathognomonic of a ruptured Baker cyst.7

In conclusion, when a hemorrhagic crescent sign is observed, one should be suspicious for a ruptured Baker cyst or other synovial pathology as an etiology of pseudocellulitis. Early recognition of the hemorrhagic crescent sign can help rule out cellulitis and DVT, thereby reducing the amount of intravenous antibiotic prescribed, decreasing the length of hospital stay, and reducing readmission.

To the Editor:

Cellulitis is the most common reason for skin-related hospital admissions.1 Despite its frequency, it is suspected that many cases of cellulitis are misdiagnosed as other etiologies presenting with similar symptoms such as a ruptured Baker cyst. These cysts are located behind the knee and can present with calf pain, peripheral edema, and erythema when ruptured. Symptoms of a ruptured Baker cyst can be indistinguishable from cellulitis as well as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), both manifesting with lower extremity pain, swelling, and erythema, making diagnosis challenging.2 The hemorrhagic crescent sign—a crescent of ecchymosis distal to the medial malleolus and on the foot that results from synovial injury or rupture—can be a useful diagnostic tool to differentiate between the causes of acute swelling and pain of the leg.2 When observed, the hemorrhagic crescent sign supports testing for synovial pathology at the knee.

A 63-year-old man presented to an outside hospital for evaluation of a fever (temperature, 101 °F [38.3 °C]), as well as pain, edema, and erythema of the right lower leg of 2 days’ duration. He had a history of leg cellulitis, gout, diabetes mellitus, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy. On admission, he was found to have elevated C-reactive protein (45 mg/L [reference range, <8 mg/L]) and mild leukocytosis (13,500 cells/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000 cells/μL]). A venous duplex scan did not demonstrate signs of thrombosis. Antibiotic therapy was started for suspected cellulitis including levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and linezolid. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, the patient continued to be febrile and experienced progressive erythema and swelling of the right lower leg, at which point he was transferred to our institution. A new antibiotic regimen of vancomycin, cefepime, and clindamycin was started and showed no improvement, after which dermatology was consulted.

Physical examination revealed unilateral edema and calor of the right lower leg with a demarcated erythematous rash extending to the level of the knee. Furthermore, a hemorrhagic crescent sign was present below the right medial malleolus (Figure). The popliteal fossa was supple, though the patient was adamant that he had a Baker cyst. Punch biopsies demonstrated epidermal spongiosis and extensive edema with perivascular inflammation. No organisms were found by stain and culture. Ultrasound records confirmed a Baker cyst present at least 4 months prior; however, a repeat ultrasound showed resolution. A diagnosis of pseudocellulitis secondary to Baker cyst rupture was made, and corticosteroids were started, resulting in marked reduction in erythema and edema of the lower leg and hospital discharge.

This case highlights the importance of early involvement of dermatology when cellulitis is suspected. A study of 635 patients in the United Kingdom referred to dermatology for lower limb cellulitis found that 210 (33%) patients did not have cellulitis and only 18 (3%) required hospital admission.3 Dermatology consultations have been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory skin disease by decreasing length of stay and reducing readmissions.4

Our patient had several risk factors for cellulitis, including obesity, lymphedema, and chronic kidney disease, in addition to having fevers and unilateral involvement. However, failure of symptoms to improve with broad-spectrum antibiotics made a diagnosis of cellulitis less likely. In this case, a severe immune response to the ruptured Baker cyst mimicked the presentation of cellulitis.

Ruptured Baker cysts have been reported to cause acute leg swelling, mimicking the symptoms of cellulitis or DVT.2,5 The presence of a hemorrhagic crescent sign can be a useful diagnostic tool, as in our patient, because it has been reported as an indication of synovial injury or rupture, supporting the exclusion of cellulitis or DVT when it is observed.6 Prior reports have observed ecchymosis on the foot in as little as 1 day after the onset of calf swelling and at the lateral malleolus 3 days after the onset of calf swelling.5

Following suspicion of a ruptured Baker cyst causing pseudocellulitis, an ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography shows a large hypoechoic space behind the calf muscles, which is pathognomonic of a ruptured Baker cyst.7

In conclusion, when a hemorrhagic crescent sign is observed, one should be suspicious for a ruptured Baker cyst or other synovial pathology as an etiology of pseudocellulitis. Early recognition of the hemorrhagic crescent sign can help rule out cellulitis and DVT, thereby reducing the amount of intravenous antibiotic prescribed, decreasing the length of hospital stay, and reducing readmission.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.7.726

- Von Schroeder HP, Ameli FM, Piazza D, et al. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causes ecchymosis of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:316-317.

- Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1326-1328.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;53:523-528.

- Dunlop D, Parker PJ, Keating JF. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causing posterior compartment syndrome. Injury. 1997;28:561-562.

- Kraag G, Thevathasan EM, Gordon DA, et al. The hemorrhagic crescent sign of acute synovial rupture. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:477-478.

- Sato O, Kondoh K, Iyori K, et al. Midcalf ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ruptured Baker’s cysts. Surg Today. 2001;31:410-413. doi:10.1007/s005950170131

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.7.726

- Von Schroeder HP, Ameli FM, Piazza D, et al. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causes ecchymosis of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:316-317.

- Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1326-1328.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;53:523-528.

- Dunlop D, Parker PJ, Keating JF. Ruptured Baker’s cyst causing posterior compartment syndrome. Injury. 1997;28:561-562.

- Kraag G, Thevathasan EM, Gordon DA, et al. The hemorrhagic crescent sign of acute synovial rupture. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:477-478.

- Sato O, Kondoh K, Iyori K, et al. Midcalf ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ruptured Baker’s cysts. Surg Today. 2001;31:410-413. doi:10.1007/s005950170131

Practice Points

- Pseudocellulitis is common in patients presenting with cellulitislike symptoms.

- A hemorrhagic crescent at the medial malleolus should lead to the suspicion on bursa or joint pathology as a cause of pseudocellulitis.

Iododerma Simulating Cryptococcal Infection

To the Editor:

A woman in her 40s presented with acute onset of rapidly spreading lesions on the face, trunk, and extremities. She reported high fever and endorsed malaise. She had a history of end-stage renal disease and was on renal dialysis. She recently underwent revision of an arteriovenous fistula.

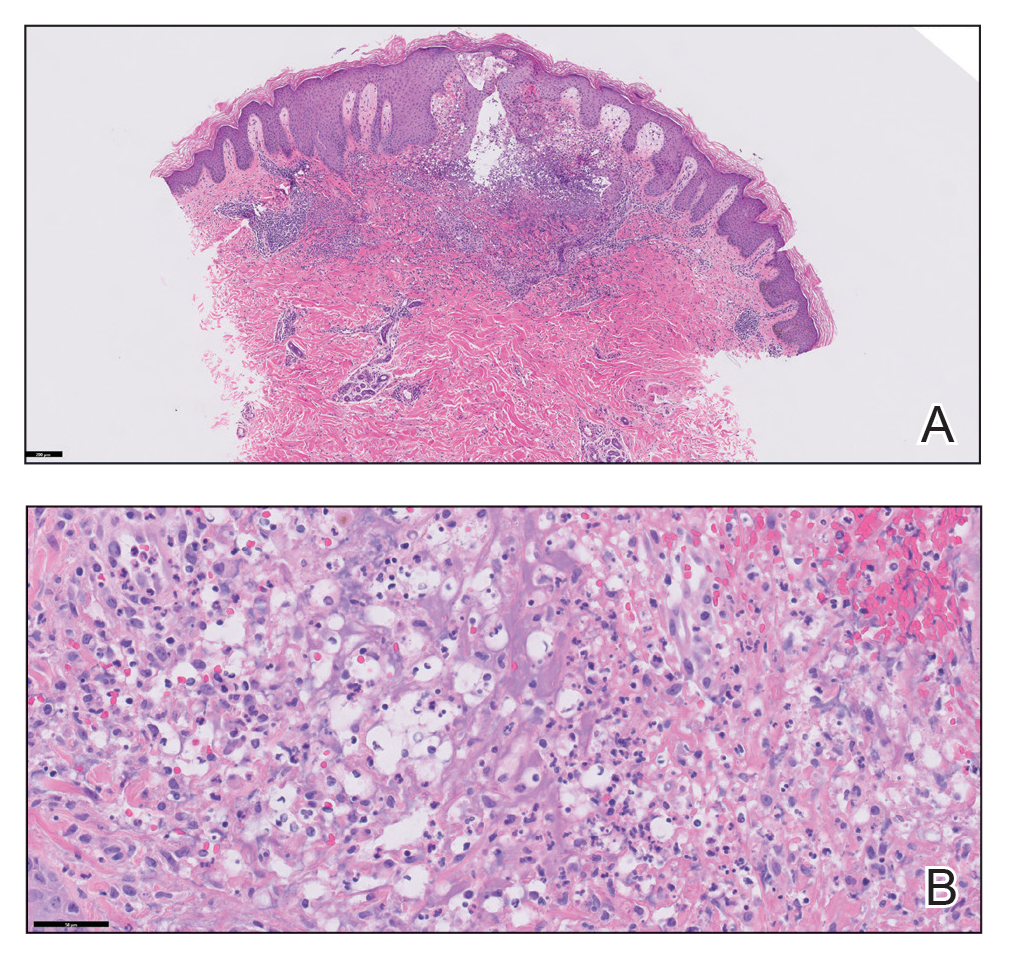

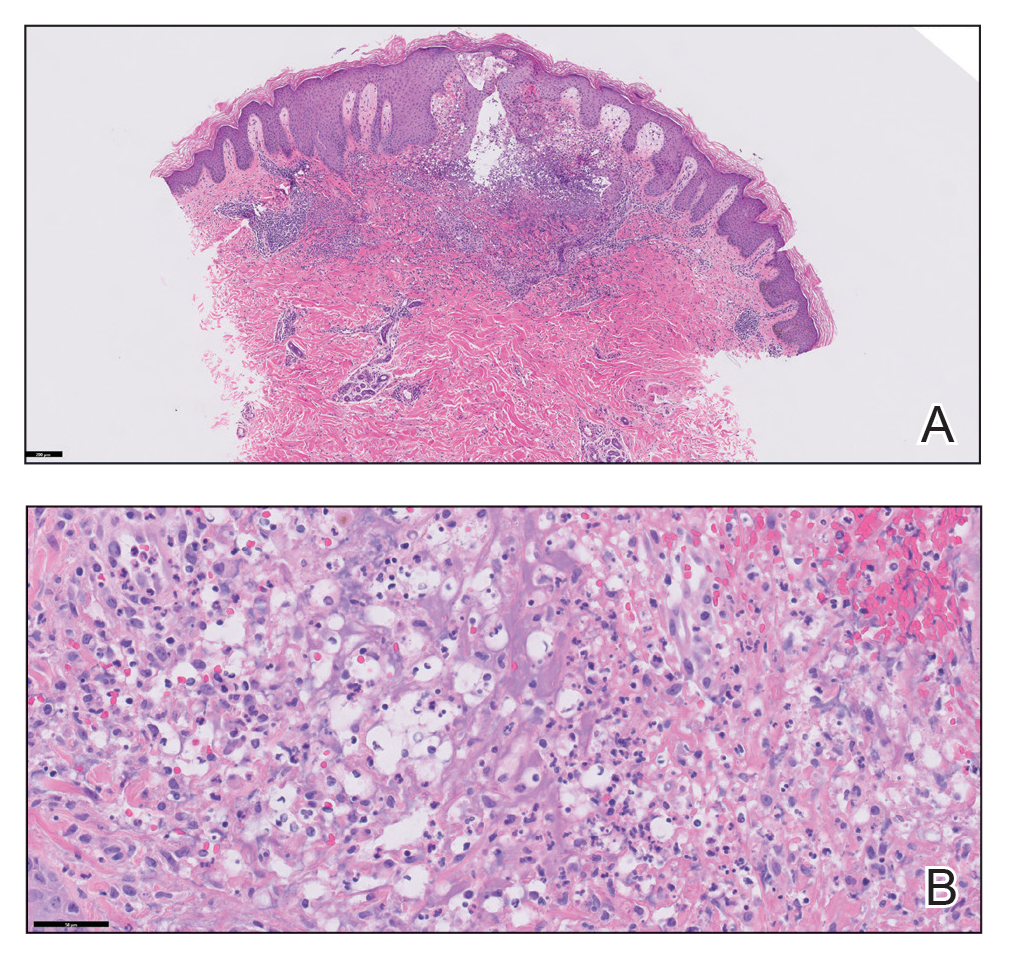

Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, firm papules and plaques with central hemorrhage and umbilication on the dorsal aspect of the nose, forehead, temples, and cheeks. There also were purpuric papules and plaques with a peripheral rim of vesiculation (Figure 1) on the medial and posterior thighs and buttocks. Histopathology of a biopsy specimen revealed an interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial dermis and mid dermis with scattered, haloed, acellular structures simulating cryptococcal organisms (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), Grocott methenamine-silver, and mucicarmine staining was negative. Repeat biopsy showed similar findings. A (1-3)-β-

The findings compatible with a diagnosis of iododerma included umbilicated hemorrhagic papules and plaques, cryptococcal-like structures with negative staining on histopathology, and elevated iodine levels with a negative infectious workup. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up, the lesions had resolved.

Iododerma is a halogenoderma, a skin eruption that occurs after ingestion of or exposure to a halogen-containing substance (eg, iodine, bromine, fluorine) or medication (eg, lithium).1 Common sources of iodine include iodinated contrast media, potassium iodide ingestion, topical application of povidone–iodine, radioactive iodine administration, and the antiarrhythmic amiodarone. Excess exposure to iodine-containing compounds typically occurs in the setting of kidney disease or failure as well as due to reduced iodine clearance.1 Although the pathogenesis of iododerma is unknown, the most common hypothesis is that lesions are delayed hypersensitivity reactions secondary to formation of a protein-halogen complex.2

The presentation of iododerma is polymorphous and includes acneform, vegetative, or pustular eruptions; umbilicated papules and plaques can be present.2,3 Lesions can be either asymptomatic or painful and pruritic. Timing between iodine exposure and onset of lesions varies from hours to days to years.2,4

Systemic symptoms of iododerma can occur, including salivary gland swelling, hypotension and bradycardia, kidney injury, or thyroid and liver abnormalities. Histopathologic analysis demonstrates a dense neutrophilic dermatitis with negative staining for infectious causes.4,5 Cryptococcal-like structures have been described in iododerma3; neutrophilic dermatoses of various causes that mimic cryptococcal infection have been reported.6 Ultimately, iododerma remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

Withdrawal of an offending compound is remedial. Dialysis is beneficial in end-stage renal disease. Topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids, as well as antibiotics, provide variable benefit.4,7 Lesions can take 4 to 6 weeks to clear after withdrawal of the offending agent. It is unclear whether recurrences happen; iodine-containing compounds need to be avoided after a patient has been affected.

Iododerma has a broad differential diagnosis due to the polymorphous presentation of the disorder, including acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (also known as Sweet syndrome), cutaneous cryptococcosis, and cutaneous histoplasmosis. Sweet syndrome presents as abrupt onset of edematous erythematous plaques with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with infection, inflammatory disorders, medication, and malignancy.8 Histopathologic analysis reveals papillary dermal edema and a neutrophilic dermatosis. Cytoplasmic vacuolization resembling C neoformans has been reported.9 The diagnosis is less favored in the presence of renal disease, temporal association of the eruption with iodine exposure, and elevated blood and urine iodine levels, as in our patient.

Cutaneous cryptococcosis, an infection caused by C neoformans, typically occurs secondary to dissemination from the lungs; rarely, the disease is primary. Acneform plaques, vegetative plaques, and umbilicated lesions are seen.10 Histopathologic analysis shows characteristic yeast forms of cryptococcosis surrounded by gelatinous edema, which create a haloed effect, typically throughout the dermis. Capsules are positive for PAS or mucicarmine staining. Although C neoformans can closely mimic iododerma both clinically and histopathologically, negative infectious staining, localization of haloed structures to the upper dermis, a negative test for cryptococcal antigen, and elevated blood and urine iodine levels in this case all favored iododerma.

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is an infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, most commonly as secondary dissemination from pulmonary infection but rarely from direct inoculation of the skin.11 Presentation includes erythematous to hemorrhagic, umbilicated papules and plaques. Histopathologic findings are round to oval, narrow-based, budding yeasts that stain positive for PAS or mucicarmine. Although histoplasmosis can clinically mimic iododerma, the disease is distinguished histologically by the presence of fungal microorganisms that lack the gelatinous edema and haloed effect of iododerma.

We presented a unique case of iododerma simulating cryptococcal infection both clinically and histopathologically. Prompt recognition of histologic mimickers of true infectious microorganisms is essential to prevent unnecessary delay of withdrawal of the offending substance and to initiate appropriate therapy.

- Alagheband M, Engineer L. Lithium and halogenoderma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:126-127. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.1.126

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379. doi:10.1111/bjd.12852

- Runge M, Williams K, Scharnitz T, et al. Iodine toxicity after iodinated contrast: new observations in iododerma. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:319-322. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.006

- Chalela JG, Aguilar L. Iododerma from contrast material. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2477. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1512512

- Chang MW, Miner JE, Moiin A, et al. Iododerma after computed tomographic scan with intravenous radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:1014-1016. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80291-5

- Ko JS, Fernandez AP, Anderson KA, et al. Morphologic mimickers of Cryptococcus occurring within inflammatory infiltrates in the setting of neutrophilic dermatitis: a series of three cases highlighting clinical dilemmas associated with a novel histopathologic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:38-45. doi:10.1111/cup.12019

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Salzetta M, et al. Vegetating iododerma and pulmonary eosinophilic infiltration. a simple co-occurrence? Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:480-481.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. M. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.064

- Wilson J, Gleghorn K, Kelly B. Cryptococcoid Sweet’s syndrome: two reports of Sweet’s syndrome mimicking cutaneous cryptococcosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:413-419. doi:10.1111/cup.12921

- Beatson M, Harwood M, Reese V, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an elderly pigeon breeder. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:433-435. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.03.006

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348. doi:10.1177/0145561318097010-1108

To the Editor:

A woman in her 40s presented with acute onset of rapidly spreading lesions on the face, trunk, and extremities. She reported high fever and endorsed malaise. She had a history of end-stage renal disease and was on renal dialysis. She recently underwent revision of an arteriovenous fistula.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, firm papules and plaques with central hemorrhage and umbilication on the dorsal aspect of the nose, forehead, temples, and cheeks. There also were purpuric papules and plaques with a peripheral rim of vesiculation (Figure 1) on the medial and posterior thighs and buttocks. Histopathology of a biopsy specimen revealed an interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial dermis and mid dermis with scattered, haloed, acellular structures simulating cryptococcal organisms (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), Grocott methenamine-silver, and mucicarmine staining was negative. Repeat biopsy showed similar findings. A (1-3)-β-

The findings compatible with a diagnosis of iododerma included umbilicated hemorrhagic papules and plaques, cryptococcal-like structures with negative staining on histopathology, and elevated iodine levels with a negative infectious workup. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up, the lesions had resolved.

Iododerma is a halogenoderma, a skin eruption that occurs after ingestion of or exposure to a halogen-containing substance (eg, iodine, bromine, fluorine) or medication (eg, lithium).1 Common sources of iodine include iodinated contrast media, potassium iodide ingestion, topical application of povidone–iodine, radioactive iodine administration, and the antiarrhythmic amiodarone. Excess exposure to iodine-containing compounds typically occurs in the setting of kidney disease or failure as well as due to reduced iodine clearance.1 Although the pathogenesis of iododerma is unknown, the most common hypothesis is that lesions are delayed hypersensitivity reactions secondary to formation of a protein-halogen complex.2

The presentation of iododerma is polymorphous and includes acneform, vegetative, or pustular eruptions; umbilicated papules and plaques can be present.2,3 Lesions can be either asymptomatic or painful and pruritic. Timing between iodine exposure and onset of lesions varies from hours to days to years.2,4

Systemic symptoms of iododerma can occur, including salivary gland swelling, hypotension and bradycardia, kidney injury, or thyroid and liver abnormalities. Histopathologic analysis demonstrates a dense neutrophilic dermatitis with negative staining for infectious causes.4,5 Cryptococcal-like structures have been described in iododerma3; neutrophilic dermatoses of various causes that mimic cryptococcal infection have been reported.6 Ultimately, iododerma remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

Withdrawal of an offending compound is remedial. Dialysis is beneficial in end-stage renal disease. Topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids, as well as antibiotics, provide variable benefit.4,7 Lesions can take 4 to 6 weeks to clear after withdrawal of the offending agent. It is unclear whether recurrences happen; iodine-containing compounds need to be avoided after a patient has been affected.

Iododerma has a broad differential diagnosis due to the polymorphous presentation of the disorder, including acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (also known as Sweet syndrome), cutaneous cryptococcosis, and cutaneous histoplasmosis. Sweet syndrome presents as abrupt onset of edematous erythematous plaques with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with infection, inflammatory disorders, medication, and malignancy.8 Histopathologic analysis reveals papillary dermal edema and a neutrophilic dermatosis. Cytoplasmic vacuolization resembling C neoformans has been reported.9 The diagnosis is less favored in the presence of renal disease, temporal association of the eruption with iodine exposure, and elevated blood and urine iodine levels, as in our patient.

Cutaneous cryptococcosis, an infection caused by C neoformans, typically occurs secondary to dissemination from the lungs; rarely, the disease is primary. Acneform plaques, vegetative plaques, and umbilicated lesions are seen.10 Histopathologic analysis shows characteristic yeast forms of cryptococcosis surrounded by gelatinous edema, which create a haloed effect, typically throughout the dermis. Capsules are positive for PAS or mucicarmine staining. Although C neoformans can closely mimic iododerma both clinically and histopathologically, negative infectious staining, localization of haloed structures to the upper dermis, a negative test for cryptococcal antigen, and elevated blood and urine iodine levels in this case all favored iododerma.

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is an infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, most commonly as secondary dissemination from pulmonary infection but rarely from direct inoculation of the skin.11 Presentation includes erythematous to hemorrhagic, umbilicated papules and plaques. Histopathologic findings are round to oval, narrow-based, budding yeasts that stain positive for PAS or mucicarmine. Although histoplasmosis can clinically mimic iododerma, the disease is distinguished histologically by the presence of fungal microorganisms that lack the gelatinous edema and haloed effect of iododerma.

We presented a unique case of iododerma simulating cryptococcal infection both clinically and histopathologically. Prompt recognition of histologic mimickers of true infectious microorganisms is essential to prevent unnecessary delay of withdrawal of the offending substance and to initiate appropriate therapy.

To the Editor:

A woman in her 40s presented with acute onset of rapidly spreading lesions on the face, trunk, and extremities. She reported high fever and endorsed malaise. She had a history of end-stage renal disease and was on renal dialysis. She recently underwent revision of an arteriovenous fistula.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, firm papules and plaques with central hemorrhage and umbilication on the dorsal aspect of the nose, forehead, temples, and cheeks. There also were purpuric papules and plaques with a peripheral rim of vesiculation (Figure 1) on the medial and posterior thighs and buttocks. Histopathology of a biopsy specimen revealed an interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial dermis and mid dermis with scattered, haloed, acellular structures simulating cryptococcal organisms (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), Grocott methenamine-silver, and mucicarmine staining was negative. Repeat biopsy showed similar findings. A (1-3)-β-

The findings compatible with a diagnosis of iododerma included umbilicated hemorrhagic papules and plaques, cryptococcal-like structures with negative staining on histopathology, and elevated iodine levels with a negative infectious workup. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up, the lesions had resolved.

Iododerma is a halogenoderma, a skin eruption that occurs after ingestion of or exposure to a halogen-containing substance (eg, iodine, bromine, fluorine) or medication (eg, lithium).1 Common sources of iodine include iodinated contrast media, potassium iodide ingestion, topical application of povidone–iodine, radioactive iodine administration, and the antiarrhythmic amiodarone. Excess exposure to iodine-containing compounds typically occurs in the setting of kidney disease or failure as well as due to reduced iodine clearance.1 Although the pathogenesis of iododerma is unknown, the most common hypothesis is that lesions are delayed hypersensitivity reactions secondary to formation of a protein-halogen complex.2

The presentation of iododerma is polymorphous and includes acneform, vegetative, or pustular eruptions; umbilicated papules and plaques can be present.2,3 Lesions can be either asymptomatic or painful and pruritic. Timing between iodine exposure and onset of lesions varies from hours to days to years.2,4

Systemic symptoms of iododerma can occur, including salivary gland swelling, hypotension and bradycardia, kidney injury, or thyroid and liver abnormalities. Histopathologic analysis demonstrates a dense neutrophilic dermatitis with negative staining for infectious causes.4,5 Cryptococcal-like structures have been described in iododerma3; neutrophilic dermatoses of various causes that mimic cryptococcal infection have been reported.6 Ultimately, iododerma remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

Withdrawal of an offending compound is remedial. Dialysis is beneficial in end-stage renal disease. Topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids, as well as antibiotics, provide variable benefit.4,7 Lesions can take 4 to 6 weeks to clear after withdrawal of the offending agent. It is unclear whether recurrences happen; iodine-containing compounds need to be avoided after a patient has been affected.

Iododerma has a broad differential diagnosis due to the polymorphous presentation of the disorder, including acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (also known as Sweet syndrome), cutaneous cryptococcosis, and cutaneous histoplasmosis. Sweet syndrome presents as abrupt onset of edematous erythematous plaques with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with infection, inflammatory disorders, medication, and malignancy.8 Histopathologic analysis reveals papillary dermal edema and a neutrophilic dermatosis. Cytoplasmic vacuolization resembling C neoformans has been reported.9 The diagnosis is less favored in the presence of renal disease, temporal association of the eruption with iodine exposure, and elevated blood and urine iodine levels, as in our patient.

Cutaneous cryptococcosis, an infection caused by C neoformans, typically occurs secondary to dissemination from the lungs; rarely, the disease is primary. Acneform plaques, vegetative plaques, and umbilicated lesions are seen.10 Histopathologic analysis shows characteristic yeast forms of cryptococcosis surrounded by gelatinous edema, which create a haloed effect, typically throughout the dermis. Capsules are positive for PAS or mucicarmine staining. Although C neoformans can closely mimic iododerma both clinically and histopathologically, negative infectious staining, localization of haloed structures to the upper dermis, a negative test for cryptococcal antigen, and elevated blood and urine iodine levels in this case all favored iododerma.

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is an infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, most commonly as secondary dissemination from pulmonary infection but rarely from direct inoculation of the skin.11 Presentation includes erythematous to hemorrhagic, umbilicated papules and plaques. Histopathologic findings are round to oval, narrow-based, budding yeasts that stain positive for PAS or mucicarmine. Although histoplasmosis can clinically mimic iododerma, the disease is distinguished histologically by the presence of fungal microorganisms that lack the gelatinous edema and haloed effect of iododerma.

We presented a unique case of iododerma simulating cryptococcal infection both clinically and histopathologically. Prompt recognition of histologic mimickers of true infectious microorganisms is essential to prevent unnecessary delay of withdrawal of the offending substance and to initiate appropriate therapy.

- Alagheband M, Engineer L. Lithium and halogenoderma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:126-127. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.1.126

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379. doi:10.1111/bjd.12852

- Runge M, Williams K, Scharnitz T, et al. Iodine toxicity after iodinated contrast: new observations in iododerma. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:319-322. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.006

- Chalela JG, Aguilar L. Iododerma from contrast material. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2477. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1512512

- Chang MW, Miner JE, Moiin A, et al. Iododerma after computed tomographic scan with intravenous radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:1014-1016. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80291-5

- Ko JS, Fernandez AP, Anderson KA, et al. Morphologic mimickers of Cryptococcus occurring within inflammatory infiltrates in the setting of neutrophilic dermatitis: a series of three cases highlighting clinical dilemmas associated with a novel histopathologic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:38-45. doi:10.1111/cup.12019

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Salzetta M, et al. Vegetating iododerma and pulmonary eosinophilic infiltration. a simple co-occurrence? Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:480-481.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. M. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.064

- Wilson J, Gleghorn K, Kelly B. Cryptococcoid Sweet’s syndrome: two reports of Sweet’s syndrome mimicking cutaneous cryptococcosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:413-419. doi:10.1111/cup.12921

- Beatson M, Harwood M, Reese V, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an elderly pigeon breeder. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:433-435. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.03.006

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348. doi:10.1177/0145561318097010-1108

- Alagheband M, Engineer L. Lithium and halogenoderma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:126-127. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.1.126

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379. doi:10.1111/bjd.12852

- Runge M, Williams K, Scharnitz T, et al. Iodine toxicity after iodinated contrast: new observations in iododerma. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:319-322. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.006

- Chalela JG, Aguilar L. Iododerma from contrast material. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2477. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1512512

- Chang MW, Miner JE, Moiin A, et al. Iododerma after computed tomographic scan with intravenous radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:1014-1016. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80291-5

- Ko JS, Fernandez AP, Anderson KA, et al. Morphologic mimickers of Cryptococcus occurring within inflammatory infiltrates in the setting of neutrophilic dermatitis: a series of three cases highlighting clinical dilemmas associated with a novel histopathologic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:38-45. doi:10.1111/cup.12019

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Salzetta M, et al. Vegetating iododerma and pulmonary eosinophilic infiltration. a simple co-occurrence? Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:480-481.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. M. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.064

- Wilson J, Gleghorn K, Kelly B. Cryptococcoid Sweet’s syndrome: two reports of Sweet’s syndrome mimicking cutaneous cryptococcosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:413-419. doi:10.1111/cup.12921

- Beatson M, Harwood M, Reese V, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an elderly pigeon breeder. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:433-435. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.03.006

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348. doi:10.1177/0145561318097010-1108

Practice Points

- Halogenodermas are rare cutaneous reactions to excess exposure to or ingestion of halogen-containing drugs or substances such as bromine, iodine (iododerma), fluorine, and rarely lithium.

- The clinical presentation of a halogenoderma varies; the most characteristic manifestation is a vegetative or exudative plaque with a peripheral rim of pustules.

- Histologically, lesions of a halogenoderma are characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia associated with numerous intraepidermal microabscesses overlying a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils, plasma cells, eosinophils, histiocytes, and scattered multinucleated giant cells.

- Rarely, the dermal infiltrate of a halogenoderma contains abundant acellular bodies surrounded by capsulelike vacuolated spaces mimicking Cryptococcus neoformans.

Retiform Purpura on the Lower Legs

The Diagnosis: Type I Cryoglobulinemia

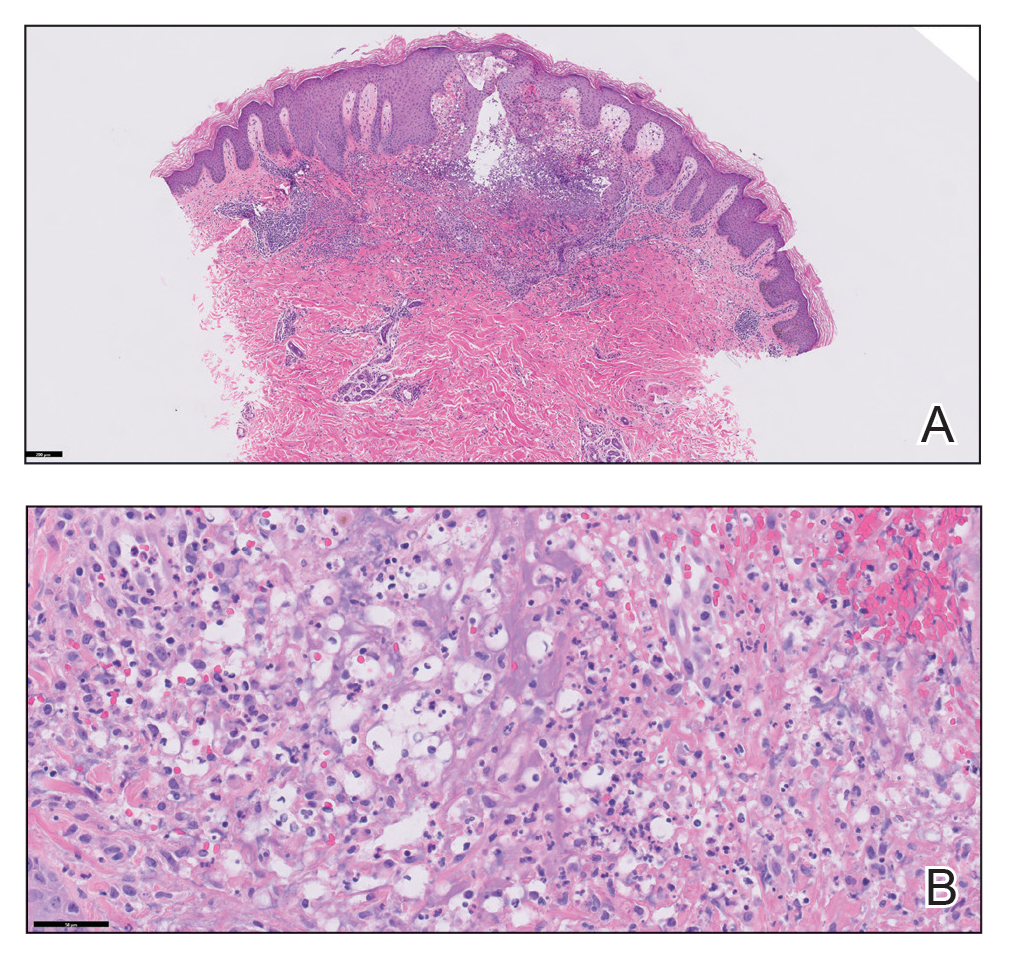

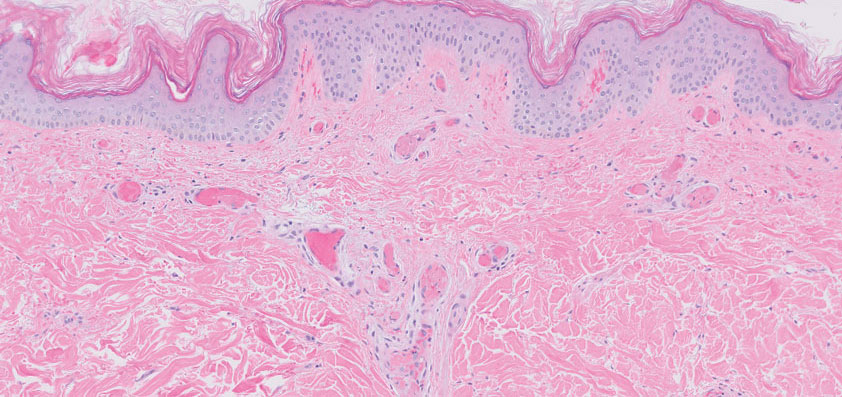

Retiform purpura with overlying necrosis subsequently developed over the course of a week following presentation (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed fibrin thrombi and congestion of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, consistent with vasculopathy (Figure 2). Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A renal biopsy performed due to a continually elevated serum creatinine level revealed glomerulonephritis with numerous IgG1 lambda–restricted glomerular capillary hyaline thrombi, compatible with a lymphoproliferative disorder–associated type I cryoglobulinemia. A serum cryoglobulin immunofixation test confirmed type I cryoglobulinemia involving monoclonal IgG lambda. The combination of cutaneous, renal, and hematologic findings was consistent with type I cryoglobulinemia. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a CD20+ lambda–restricted plasma cell neoplasm. Initial treatment with high-dose corticosteroids followed by targeted treatment of the underlying hematologic condition with bortezomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone improved the skin disease.

Cryoglobulins are abnormal immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C. The persistent presence of cryoglobulins in the serum is termed cryoglobulinemia.1 Type I cryoglobulinemia is distinguished from mixed cryoglobulinemia—types II and III—by the presence of a single monoclonal immunoglobulin, typically IgM or IgG. It is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, most commonly monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and B-cell malignancies such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Histopathology shows occlusion of small vessel lumina with homogenous eosinophilic material containing the monoclonal cryoprecipitate.2 Disease manifestations are caused by small vessel occlusion, which leads to ischemia and tissue damage.

Retiform purpura, livedo reticularis/racemosa, and necrosis leading to ulcers are the most common cutaneous clinical findings. Extracutaneous signs include peripheral neuropathy, arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrocyanosis. Renal involvement, most commonly glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria, is noted in 14% to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevated cryocrit can lead to symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome.2

Treatment is difficult and primarily is focused on addressing the underlying hematologic condition, which is responsible for synthesis of the cryoglobulin. Decreasing cryoglobulin production leads to decreased occlusion of blood vessels, thus alleviating the ischemia and skin damage. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance–related type I cryoglobulinemia initially is treated with corticosteroids followed by rituximab if a CD20+ B-cell clone is identified.2 Bortezomib is recommended for cases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia and cases associated with multiple myeloma with concurrent renal failure. In patients with neuropathy, a lenalidomide-based treatment can be employed. Patients should be instructed to keep extremities warm.2 Diabetic foot care guidelines should be followed to prevent wound complications. The differential diagnosis for type I cryoglobulinemia includes other causes of retiform purpura–like angioinvasive fungal infection, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, calciphylaxis, and livedoid vasculopathy.5 Angioinvasive fungal infections are caused by Candida, Aspergillus, and Mucorales species, as well as other hyaline molds. They typically occur in immunocompromised patients and invade the blood vessels via direct inoculation or dissemination.6 Patients present with retiform purpura but typically will be acutely ill with fevers and vital sign abnormalities. Histopathology with special stains often will identify the fungal organisms in the dermis or inside blood vessel walls with vessel wall destruction and hemorrhage.7 Accurate diagnosis is essential to selecting appropriate antifungal agents. If angioinvasive fungal infection is clinically suspected, treatment should begin before culture and histopathologic data are available.7

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is an autoimmune thrombophilia that can occur as primary disease or in association with other autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis requires the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, such as lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, anti–β2-glycoprotein-1 antibody, with arterial or venous thrombosis and/or recurrent pregnancy loss. Paraproteinemia is not seen. The most common cutaneous finding is livedo reticularis, with livedo racemosa being a more distinctive finding.8 Small vessel thrombosis is seen histopathologically. Treatment includes antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Patients with refractory disease may benefit from additional therapy with hydroxychloroquine or intravenous immunoglobulins.8

Calciphylaxis is a rare depositional vasculopathy that often occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. Patients present with painful and poor-healing skin lesions including indurated nodules, violaceous plaques, and retiform purpura that typically affect areas of high adiposity such as the thighs, abdomen, and buttocks.9 Ulceration and superimposed infections are common complications. Histopathologically, small dermal and subcutaneous vessels demonstrate calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia.9 Wound management is critically important in patients with calciphylaxis. Treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate is typical, but prognosis remains poor. Although livedoid vasculopathy may present with retiform purpura in the ankles, paraproteinemia is not seen and patients frequently present with punched-out ulcerations that tend to heal into atrophie blanche.10 Livedoid vasculopathy has been associated with underlying hypercoagulable states, connective tissue diseases, and chronic venous hypertension. Hypercoagulability and endothelial cell damage contribute to the formation of fibrin thrombi in the superficial dermal blood vessels. Histopathology demonstrates thickening of vessel walls and intraluminal hyaline thrombi. Successful treatment in most cases is achieved with anticoagulation therapy, typically rivaroxaban, especially in patients with underlying hypercoagulability. Antiplatelet therapy also may be considered, while anabolic agents have been shown to be helpful in patients with connective tissue disease.10

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Cryoglobulinemia: an update in 2019. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86:707-713. doi:10.1016/j .jbspin.2019.01.016

- Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2017;129:289-298. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-719773

- Sidana S, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with type 1 monoclonal cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:668-673. doi:10.1002/ajh.24745

- Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: a study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:671-678. doi:10.1111/bjh.13196

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Shields BE, Rosenbach M, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: background, epidemiology, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:869-880.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.059

- Berger AP, Ford BA, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: diagnosis, management, and complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:883-898.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.058

- Negrini S, Pappalardo F, Murdaca G, et al. The antiphospholipid syndrome: from pathophysiology to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17:257-267. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0430-5

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: workup and therapeutic considerations in select conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:799-816. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.113

The Diagnosis: Type I Cryoglobulinemia

Retiform purpura with overlying necrosis subsequently developed over the course of a week following presentation (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed fibrin thrombi and congestion of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, consistent with vasculopathy (Figure 2). Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A renal biopsy performed due to a continually elevated serum creatinine level revealed glomerulonephritis with numerous IgG1 lambda–restricted glomerular capillary hyaline thrombi, compatible with a lymphoproliferative disorder–associated type I cryoglobulinemia. A serum cryoglobulin immunofixation test confirmed type I cryoglobulinemia involving monoclonal IgG lambda. The combination of cutaneous, renal, and hematologic findings was consistent with type I cryoglobulinemia. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a CD20+ lambda–restricted plasma cell neoplasm. Initial treatment with high-dose corticosteroids followed by targeted treatment of the underlying hematologic condition with bortezomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone improved the skin disease.

Cryoglobulins are abnormal immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C. The persistent presence of cryoglobulins in the serum is termed cryoglobulinemia.1 Type I cryoglobulinemia is distinguished from mixed cryoglobulinemia—types II and III—by the presence of a single monoclonal immunoglobulin, typically IgM or IgG. It is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, most commonly monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and B-cell malignancies such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Histopathology shows occlusion of small vessel lumina with homogenous eosinophilic material containing the monoclonal cryoprecipitate.2 Disease manifestations are caused by small vessel occlusion, which leads to ischemia and tissue damage.

Retiform purpura, livedo reticularis/racemosa, and necrosis leading to ulcers are the most common cutaneous clinical findings. Extracutaneous signs include peripheral neuropathy, arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrocyanosis. Renal involvement, most commonly glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria, is noted in 14% to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevated cryocrit can lead to symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome.2

Treatment is difficult and primarily is focused on addressing the underlying hematologic condition, which is responsible for synthesis of the cryoglobulin. Decreasing cryoglobulin production leads to decreased occlusion of blood vessels, thus alleviating the ischemia and skin damage. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance–related type I cryoglobulinemia initially is treated with corticosteroids followed by rituximab if a CD20+ B-cell clone is identified.2 Bortezomib is recommended for cases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia and cases associated with multiple myeloma with concurrent renal failure. In patients with neuropathy, a lenalidomide-based treatment can be employed. Patients should be instructed to keep extremities warm.2 Diabetic foot care guidelines should be followed to prevent wound complications. The differential diagnosis for type I cryoglobulinemia includes other causes of retiform purpura–like angioinvasive fungal infection, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, calciphylaxis, and livedoid vasculopathy.5 Angioinvasive fungal infections are caused by Candida, Aspergillus, and Mucorales species, as well as other hyaline molds. They typically occur in immunocompromised patients and invade the blood vessels via direct inoculation or dissemination.6 Patients present with retiform purpura but typically will be acutely ill with fevers and vital sign abnormalities. Histopathology with special stains often will identify the fungal organisms in the dermis or inside blood vessel walls with vessel wall destruction and hemorrhage.7 Accurate diagnosis is essential to selecting appropriate antifungal agents. If angioinvasive fungal infection is clinically suspected, treatment should begin before culture and histopathologic data are available.7

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is an autoimmune thrombophilia that can occur as primary disease or in association with other autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis requires the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, such as lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, anti–β2-glycoprotein-1 antibody, with arterial or venous thrombosis and/or recurrent pregnancy loss. Paraproteinemia is not seen. The most common cutaneous finding is livedo reticularis, with livedo racemosa being a more distinctive finding.8 Small vessel thrombosis is seen histopathologically. Treatment includes antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Patients with refractory disease may benefit from additional therapy with hydroxychloroquine or intravenous immunoglobulins.8

Calciphylaxis is a rare depositional vasculopathy that often occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. Patients present with painful and poor-healing skin lesions including indurated nodules, violaceous plaques, and retiform purpura that typically affect areas of high adiposity such as the thighs, abdomen, and buttocks.9 Ulceration and superimposed infections are common complications. Histopathologically, small dermal and subcutaneous vessels demonstrate calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia.9 Wound management is critically important in patients with calciphylaxis. Treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate is typical, but prognosis remains poor. Although livedoid vasculopathy may present with retiform purpura in the ankles, paraproteinemia is not seen and patients frequently present with punched-out ulcerations that tend to heal into atrophie blanche.10 Livedoid vasculopathy has been associated with underlying hypercoagulable states, connective tissue diseases, and chronic venous hypertension. Hypercoagulability and endothelial cell damage contribute to the formation of fibrin thrombi in the superficial dermal blood vessels. Histopathology demonstrates thickening of vessel walls and intraluminal hyaline thrombi. Successful treatment in most cases is achieved with anticoagulation therapy, typically rivaroxaban, especially in patients with underlying hypercoagulability. Antiplatelet therapy also may be considered, while anabolic agents have been shown to be helpful in patients with connective tissue disease.10

The Diagnosis: Type I Cryoglobulinemia

Retiform purpura with overlying necrosis subsequently developed over the course of a week following presentation (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed fibrin thrombi and congestion of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, consistent with vasculopathy (Figure 2). Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A renal biopsy performed due to a continually elevated serum creatinine level revealed glomerulonephritis with numerous IgG1 lambda–restricted glomerular capillary hyaline thrombi, compatible with a lymphoproliferative disorder–associated type I cryoglobulinemia. A serum cryoglobulin immunofixation test confirmed type I cryoglobulinemia involving monoclonal IgG lambda. The combination of cutaneous, renal, and hematologic findings was consistent with type I cryoglobulinemia. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a CD20+ lambda–restricted plasma cell neoplasm. Initial treatment with high-dose corticosteroids followed by targeted treatment of the underlying hematologic condition with bortezomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone improved the skin disease.

Cryoglobulins are abnormal immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C. The persistent presence of cryoglobulins in the serum is termed cryoglobulinemia.1 Type I cryoglobulinemia is distinguished from mixed cryoglobulinemia—types II and III—by the presence of a single monoclonal immunoglobulin, typically IgM or IgG. It is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, most commonly monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and B-cell malignancies such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Histopathology shows occlusion of small vessel lumina with homogenous eosinophilic material containing the monoclonal cryoprecipitate.2 Disease manifestations are caused by small vessel occlusion, which leads to ischemia and tissue damage.

Retiform purpura, livedo reticularis/racemosa, and necrosis leading to ulcers are the most common cutaneous clinical findings. Extracutaneous signs include peripheral neuropathy, arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrocyanosis. Renal involvement, most commonly glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria, is noted in 14% to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevated cryocrit can lead to symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome.2

Treatment is difficult and primarily is focused on addressing the underlying hematologic condition, which is responsible for synthesis of the cryoglobulin. Decreasing cryoglobulin production leads to decreased occlusion of blood vessels, thus alleviating the ischemia and skin damage. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance–related type I cryoglobulinemia initially is treated with corticosteroids followed by rituximab if a CD20+ B-cell clone is identified.2 Bortezomib is recommended for cases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia and cases associated with multiple myeloma with concurrent renal failure. In patients with neuropathy, a lenalidomide-based treatment can be employed. Patients should be instructed to keep extremities warm.2 Diabetic foot care guidelines should be followed to prevent wound complications. The differential diagnosis for type I cryoglobulinemia includes other causes of retiform purpura–like angioinvasive fungal infection, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, calciphylaxis, and livedoid vasculopathy.5 Angioinvasive fungal infections are caused by Candida, Aspergillus, and Mucorales species, as well as other hyaline molds. They typically occur in immunocompromised patients and invade the blood vessels via direct inoculation or dissemination.6 Patients present with retiform purpura but typically will be acutely ill with fevers and vital sign abnormalities. Histopathology with special stains often will identify the fungal organisms in the dermis or inside blood vessel walls with vessel wall destruction and hemorrhage.7 Accurate diagnosis is essential to selecting appropriate antifungal agents. If angioinvasive fungal infection is clinically suspected, treatment should begin before culture and histopathologic data are available.7

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is an autoimmune thrombophilia that can occur as primary disease or in association with other autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis requires the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, such as lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, anti–β2-glycoprotein-1 antibody, with arterial or venous thrombosis and/or recurrent pregnancy loss. Paraproteinemia is not seen. The most common cutaneous finding is livedo reticularis, with livedo racemosa being a more distinctive finding.8 Small vessel thrombosis is seen histopathologically. Treatment includes antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Patients with refractory disease may benefit from additional therapy with hydroxychloroquine or intravenous immunoglobulins.8

Calciphylaxis is a rare depositional vasculopathy that often occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. Patients present with painful and poor-healing skin lesions including indurated nodules, violaceous plaques, and retiform purpura that typically affect areas of high adiposity such as the thighs, abdomen, and buttocks.9 Ulceration and superimposed infections are common complications. Histopathologically, small dermal and subcutaneous vessels demonstrate calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia.9 Wound management is critically important in patients with calciphylaxis. Treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate is typical, but prognosis remains poor. Although livedoid vasculopathy may present with retiform purpura in the ankles, paraproteinemia is not seen and patients frequently present with punched-out ulcerations that tend to heal into atrophie blanche.10 Livedoid vasculopathy has been associated with underlying hypercoagulable states, connective tissue diseases, and chronic venous hypertension. Hypercoagulability and endothelial cell damage contribute to the formation of fibrin thrombi in the superficial dermal blood vessels. Histopathology demonstrates thickening of vessel walls and intraluminal hyaline thrombi. Successful treatment in most cases is achieved with anticoagulation therapy, typically rivaroxaban, especially in patients with underlying hypercoagulability. Antiplatelet therapy also may be considered, while anabolic agents have been shown to be helpful in patients with connective tissue disease.10

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Cryoglobulinemia: an update in 2019. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86:707-713. doi:10.1016/j .jbspin.2019.01.016

- Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2017;129:289-298. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-719773

- Sidana S, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with type 1 monoclonal cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:668-673. doi:10.1002/ajh.24745

- Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: a study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:671-678. doi:10.1111/bjh.13196

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Shields BE, Rosenbach M, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: background, epidemiology, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:869-880.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.059

- Berger AP, Ford BA, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: diagnosis, management, and complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:883-898.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.058

- Negrini S, Pappalardo F, Murdaca G, et al. The antiphospholipid syndrome: from pathophysiology to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17:257-267. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0430-5

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: workup and therapeutic considerations in select conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:799-816. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.113

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Cryoglobulinemia: an update in 2019. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86:707-713. doi:10.1016/j .jbspin.2019.01.016

- Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2017;129:289-298. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-719773

- Sidana S, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with type 1 monoclonal cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:668-673. doi:10.1002/ajh.24745

- Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: a study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:671-678. doi:10.1111/bjh.13196

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Shields BE, Rosenbach M, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: background, epidemiology, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:869-880.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.059

- Berger AP, Ford BA, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: diagnosis, management, and complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:883-898.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.058

- Negrini S, Pappalardo F, Murdaca G, et al. The antiphospholipid syndrome: from pathophysiology to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17:257-267. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0430-5

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: workup and therapeutic considerations in select conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:799-816. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.113

A 58-year-old man presented with a petechial and purpuric rash limited to the lower extremities. He reported that the rash had been present for months but worsened acutely over the last 3 days with new-onset dark urine, joint pain, and edema limiting his ability to walk. Physical examination showed areas of violaceous macules and papules on the legs and dorsal feet in a reticular distribution. Laboratory findings were remarkable for an elevated serum creatinine level of 2.75 mg/dL (reference range, 0.70–1.30 mg/dL), and serum immunofixation revealed the presence of markedly elevated IgG lambda monoclonal proteins. He was afebrile and his vital signs were stable. Dermatology, nephrology, and rheumatology services were consulted.

Unusual Presentation of Erythema Elevatum Diutinum With Underlying Hepatitis B Infection

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) manifests on a clinicopathologic spectrum of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. The lesions typically present as persistent, symmetric, firm, red to purple papules or nodules on the extensor arms and dorsal hands.1,2 Underlying infectious, malignant, or autoimmune processes are commonly associated with the disease, notably Streptococcus infection and IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2,3 Hepatitis virus also is often implicated in association with EED. Cases of EED have been seen with concomitant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.4-6 We report a case of EED presenting in various stages of evolution associated with underlying hepatitis B infection alone.

Case Report

A 57-year-old man originally presented to an outpatient dermatology practice with a nodular, painful, episodic rash on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. A biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with prominent eosinophils. At the time, the skin findings were believed to be a manifestation of drug hypersensitivity, likely to opioid use. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Seven years later, the patient was admitted to the hospital with new-onset burning and stinging red nodules on the dorsum of the hands and persistence of the original episodic rash over the lower legs and bilateral flanks. In the interim, he was briefly treated with an oral prednisone taper and topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone cream 0.1% and clobetasol cream 0.05% without improvement.

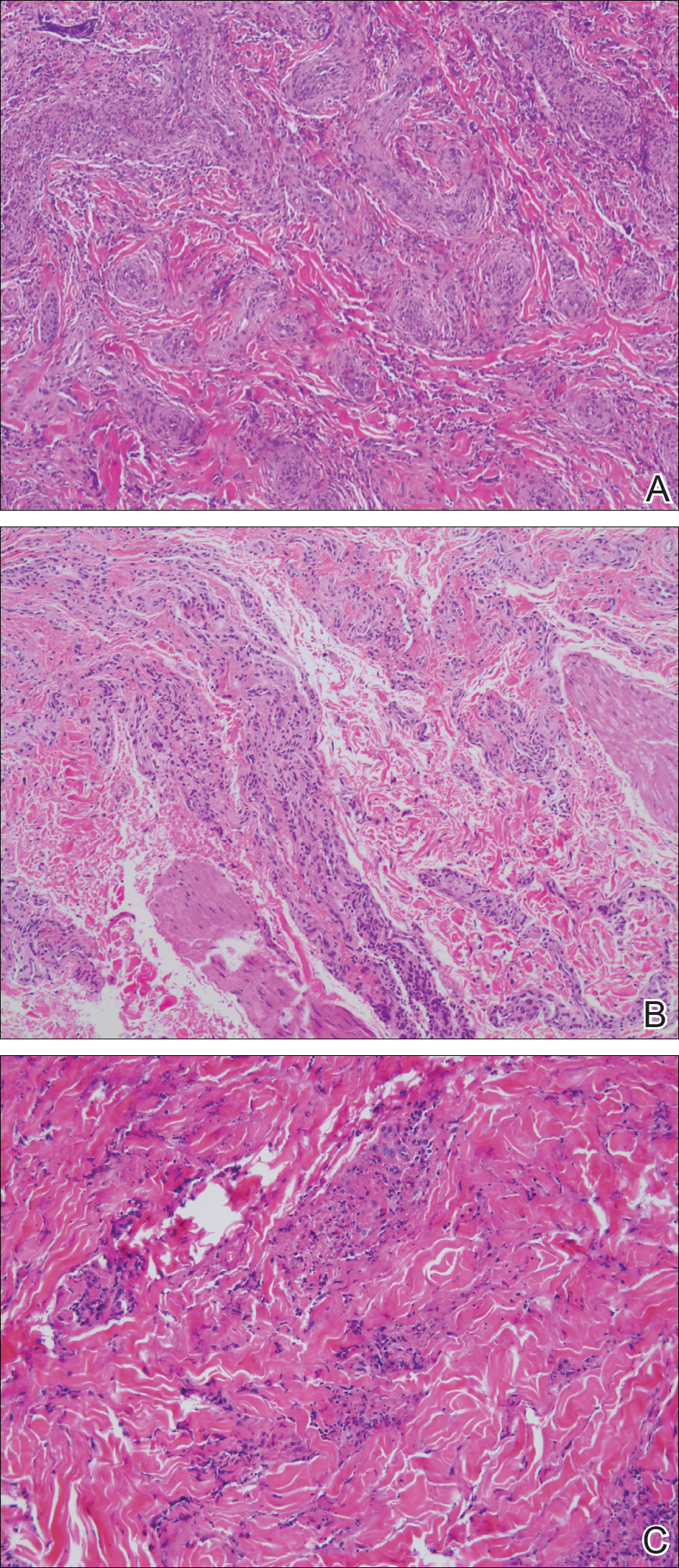

On examination deep red to violaceous discrete nodules and plaques with overlying hyperkeratosis involving all distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands and extensor elbows were seen (Figure 1A). On the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1B), anterior legs, and periumbilical area were deeply erythematous papules and plaques with background hyperpigmentation. Across his lower back and bilateral flanks were erythematous papules with central hemorrhagic crusting (Figure 1C).

Pertinent laboratory findings included a positive hepatitis B surface antigen with hepatitis B DNA value 4,313,876 IU/mL and a hepatitis B virus quantitative polymerase chain reaction value of 6.64 U. The etiology was suspected to be intravenous drug abuse; however, the patient denied recreational drug use.

An additional infectious workup was negative for hepatitis C, streptococcus, syphilis, tuberculosis, and HIV. A complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, complement, cryoglobulins, and serum protein electrophoresis were within reference range. Autoimmune serologies were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, anti-Smith, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. Peripheral blood immunophenotyping, lactate dehydrogenase, quantitative immunoglobulins, and age-appropriate cancer screens did not demonstrate evidence for malignancy underlying the disease. Bilateral hand radiographs showed mild periostitis of the proximal phalanges without obvious erosions.

Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the left fifth digit, left posterior arm, and left flank. Tissue of the left fifth digit showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with a concentric pattern resembling onion skin in a background of increased fibrosis. The blood vessels showed focal fibrinoid necrosis (Figure 2A). The biopsy of the left posterior arm showed an intradermal vascular proliferation with an associated mild acute and chronic perivascular inflammation (Figure 2B). The left flank biopsy showed LCV with focal epidermal necrosis (Figure 2C).

The constellation of clinical findings together with the histopathologic changes represented EED in various stages of evolution. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and referred to the infectious disease service for treatment of chronic hepatitis B; however, he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Overview of EED

Erythema elevatum diutinum represents a rare form of chronic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Originally described by Hutchinson7 and Bury8 as symmetric purpuric nodules of the skin, it was later named by Crocker and Williams9 in 1894. The disease classically presents as firm, fixed, red-brown to violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules affecting the extensor upper or lower extremities.1 Lesions are most commonly found symmetrically overlying joints of the hands, feet, elbows, and knees, as well as the Achilles tendon and buttocks.3 Less common locations include the palms and soles, face,10,11 trunk,12 and periauricular region.1 Although they are typically asymptomatic, sensations such as burning, stinging, and pruritus have been noted.1 Our patient was unique because in addition to typical lesions of EED, he presented with crusted papules on the flanks and violaceous papules of the lower legs and periumbilicus.

Etiology

Originally associated with Streptococcus as isolated from EED lesions,3,13 additional infectious etiologies include viral hepatitis,4-6 human herpesvirus 6,14 and rarely HIV.1,15 Hepatitis B and C are well known to be associated with EED, with only rare reports in patients with concomitant HIV infection. Erythema elevatum diutinum also has been described in relationship to myeloproliferative disorders and hematologic malignancies such as IgA myeloma,16 non-Hodgkin lymphoma,17 chronic lymphocytic leukemia,18 and hypergammaglobulinemia.19 In a study of 13 patients with EED, 4 had associated underlying IgA monoclonal gammopathy.2 Autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis,20 ulcerative colitis,21 relapsing polychondritis,22 and systemic lupus erythematosus23 also have been implicated.

Pathogenesis

Although the precise pathogenesis of EED remains unknown, it has been suggested that a complement cascade initiated by immune-complex deposition in postcapillary venules induces an LCV.24,25 Chronic antigenic exposure or high antibody levels26 in the face of infections, autoimmune disease, or malignancy may incite this immune-complex reaction. Skin lesions seen in association with hepatitis reflect circulating immune-complex deposition in vessel walls causing destruction. It has been postulated that the duration of immune complexemia may be sufficient to account for the differences in the type of vascular injury seen in acute versus chronic infection.27

Histopathology

Erythema elevatum diutinum may present on a histopathologic spectrum of LCV, as manifested in our patient. Early lesions show predominantly polymorphonuclear cells with nuclear dust pattern in a wedge-shaped infiltrate with fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid dermis.2,3 Later lesions show vasculitis in addition to dermal aggregates of lymphocytes, neutrophils, fibrosis, and areas of granulation tissue. The fibrosis may be dense and comprised of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.28 Newly formed vessels within the granulation tissue have been postulated to be more susceptible to immune-complex deposition, thus potentiating the process.1,29

Management

Spontaneous resolution of EED may occur, albeit after a prolonged and recurrent course of up to 5 to 10 years.30 Treatment of the underlying cause, when identified, remains paramount. First-line therapy includes dapsone, shown to be effective in reducing lesion size to complete resolution in 80% of the 47 cases reviewed by Momen et al.31 Dapsone monotherapy tends to be less effective in treating nodular lesions associated with HIV-positivity, likely due to the extensive fibrosis.4,31 Combination therapy with dapsone and a sulfonamide,32 niacinamide and tetracycline,33 colchicine,34 or surgical excision35 may be necessary in more resistant cases.

Conclusion

Our case exemplifies the clinical histologic spectrum that EED can present. The constellation of clinical findings was histologically confirmed to be manifestations of the disease in various stages of evolution. When typical lesions of EED present along with cutaneous findings in less common locations, performing multiple biopsies can be helpful. The clinician should retain a high index of suspicion for an underlying etiology and perform a complete workup for infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Wilkinson SM, English JS, Smith NP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinicopathological study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:87-93.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2001;68:41-42, 55.

- Kim H. Erythema elevatum diutinum in an HIV-positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:411-412.

- Revenga F, Vera A, Muñoz A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and AIDS: are they related? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:250-251.

- Hutchinson J. On two remarkable cases of symmetrieal purple congestion of the skin in patches, with induration. Br J Dermatol. 1888;1:10-15.

- Bury JS. A case of erythema with remarkable nodular thickening and induration of the skin associated with intermittent albuminuria. Illustrated Medical News. 1889;3:145-149.

- Crocker HR, Williams C. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1894;6:33-38.

- Barzegar M, Davatchi CC, Akhyani M, et al. An atypical presentation of erythema elevatum diutinum involving palms and soles. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:73-75.

- Futei Y, Konohana I. A case of erythema elevatum diutinum associated with B-cell lymphoma: a rare distribution involving palms, soles and nails. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:116-119.

- Ben-Zvi GT, Bardsley V, Burrows NP. An atypical distribution of erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:269-270.

- Weidman FD, Besancon JH. Erythema elevatum diutinum. role of streptococci, and relationship to other rheumatic dermatoses. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1929;20:593-620.

- Drago F, Semino M, Rampini P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human herpesvirus 6 infection. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:91-92.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:335-338.

- Archimandritis AJ, Fertakis A, Alegakis G, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and IgA myeloma: an interesting association. Br Med J. 1977;2:613-614.

- Hatzitolios A, Tzellos TG, Savopoulos C, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum with rare distribution as a first clinical sign of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a novel association? J Dermatol. 2008;35:297-300.

- Delaporte E, Alfandari S, Fenaux P, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:188-189.

- Miyagawa S, Kitamura W, Morita K, et al. Association of hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D syndrome with erythema elevatum diutinum. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:572-574.

- Collier PM, Neill SM, Branfoot AC, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—a solitary lesion in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:394-395.

- Buahene K, Hudson M, Mowat A, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum—an unusual association with ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:204-206.