User login

Cemiplimab-Associated Eruption of Generalized Eruptive Keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

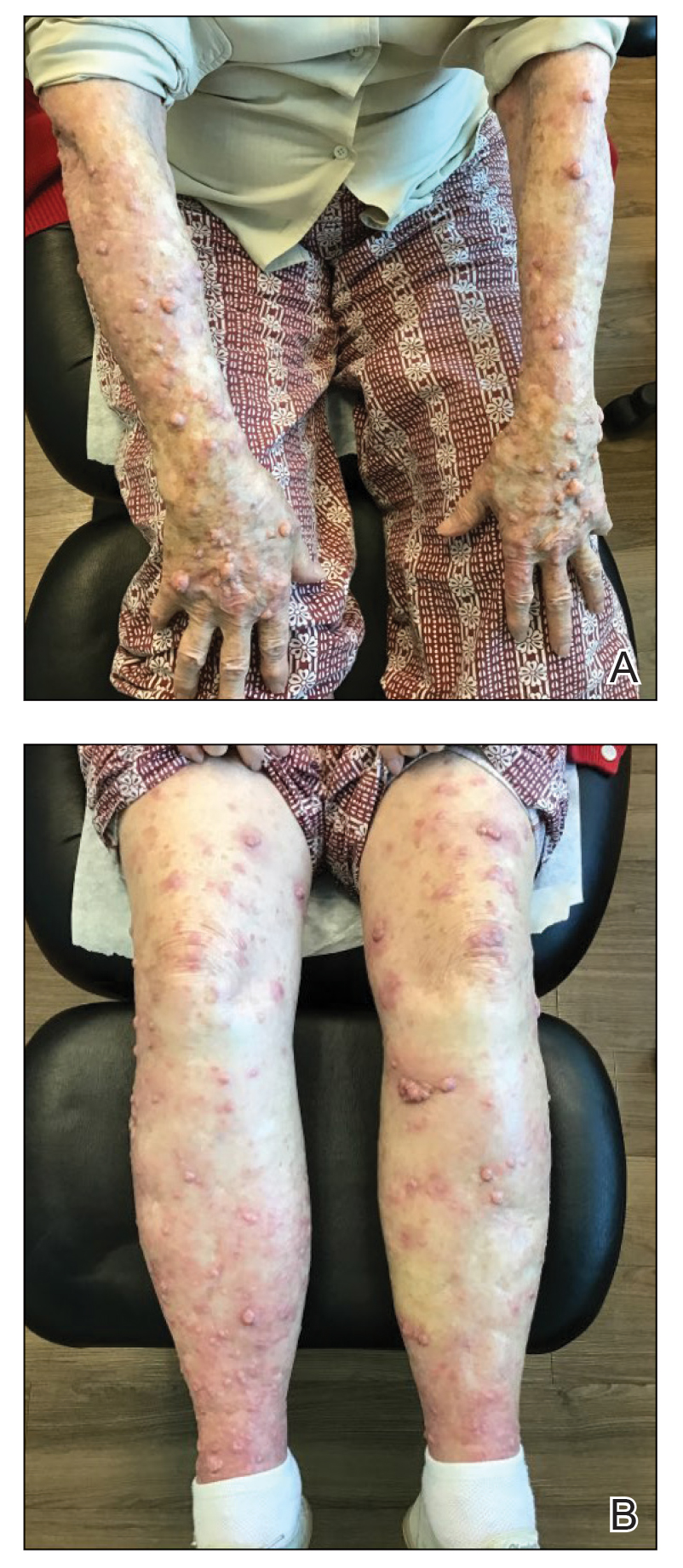

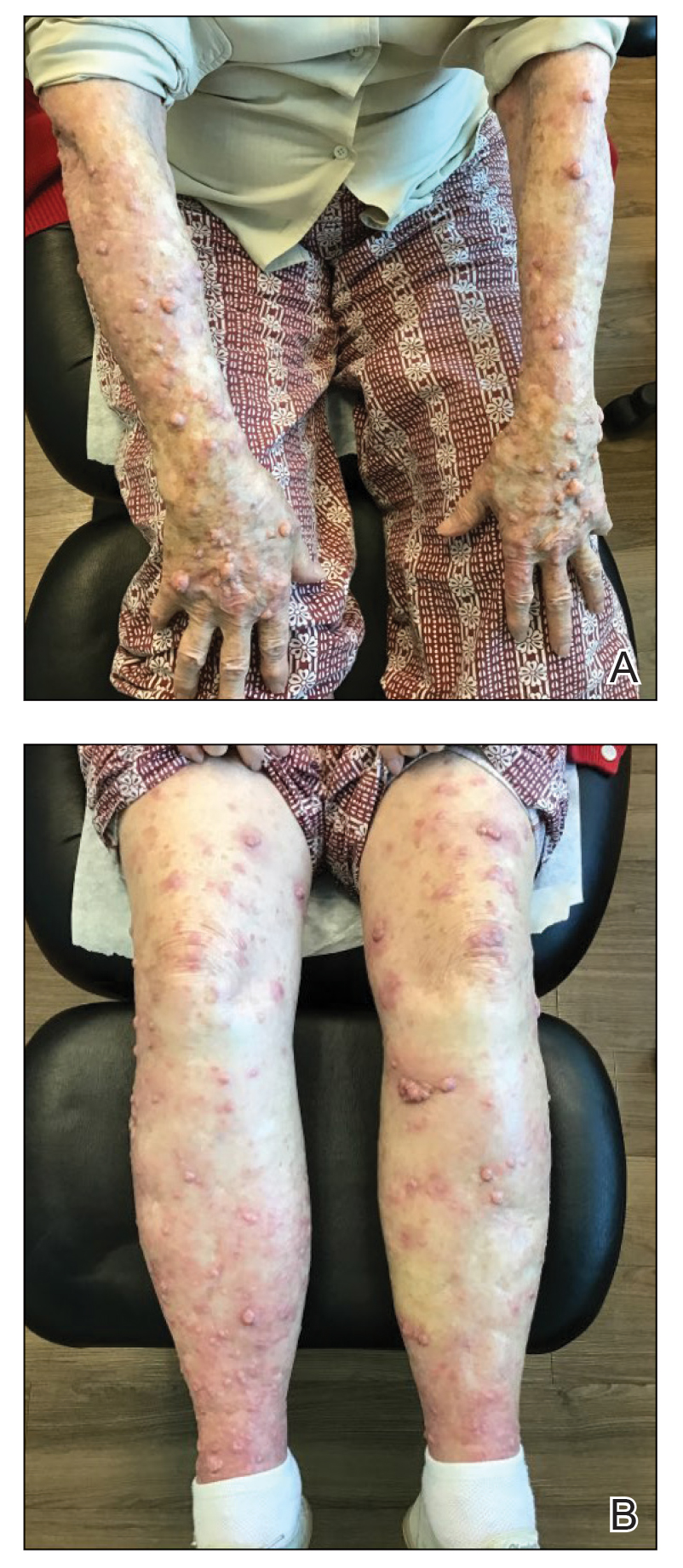

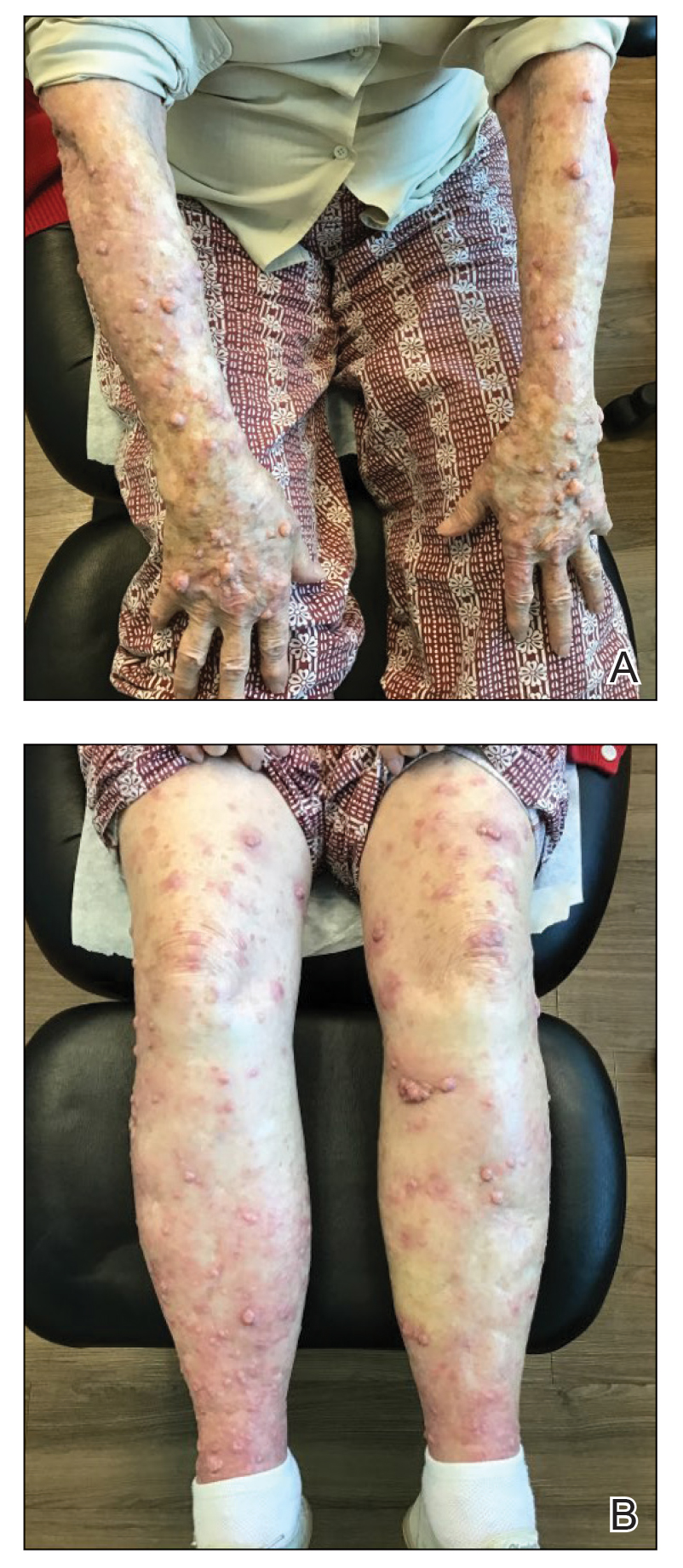

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of cSCC is complex and possibly involves contrasting roles of leukocyte subpopulations.8 The increased incidence of cSCC in the immunocompromised population,8 PD-L1 overexpression in cSCC,9,10 and successful treatment of cSCC with PD-1 inhibition10 all suggest that inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways is pivotal in tumor pathogenesis. However, increased inflammation, particularly inflammation driven by T lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, also is believed to play a key role in the formation of cSCCs, including the degeneration of actinic keratosis into cSCC. Moreover, because keratoacanthomas are believed to be a cSCC variant and also are associated with PD-L1 overexpression,9 it is perplexing that PD-1 blockade may result in eruptive keratoacanthoma in some patients while also treating locally advanced cSCC, as seen in our patient. Successful treatment of keratoacanthoma with anti-inflammatory intralesional or topical corticosteroids adds to this complicated picture.3

We hypothesize that the pathogenesis of invasive cSCC and keratoacanthoma shares certain immune-mediated mechanisms but also differs in distinct manners. To understand the relationship between systemic treatment of cSCC and eruptive keratoacanthoma, further research is required.

In addition, the RAS/BRAF/MEK oncogenic pathway may be involved in the development of cSCCs associated with anti-PD-1. It is hypothesized that BRAF and MEK inhibition increases T-cell infiltration and increases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells,11 thus increasing the susceptibility of those cells to PD-1 blockade. Further supporting a relationship between the RAS/BRAF/MEK and PD-1 pathways, BRAF inhibitors are associated with development of SCCs and verrucal keratosis by upregulation of the RAS pathway.12,13 Perhaps a common mechanism underlying these pathways results in their shared association for an increased risk for cSCC upon blockade. More research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying biochemical mechanism of immunotherapy and formation of SCCs, such as keratoacanthoma.

Treatment of solitary keratoacanthoma often involves surgical excision; however, the sheer number of lesions in eruptive keratoacanthoma presents a larger dilemma. Because oral systemic retinoids have been shown to be most effective for treating eruptive keratoacanthoma, they are considered first-line therapy as monotherapy or in combination with surgical excision.3 Other treatment options include intralesional or topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and cryotherapy.3,6

The development of ICIs has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous malignancy, yet we have a great deal more to comprehend on the systemic effects of these medications. Although IRAEs may signal a better response to therapy, some of these effects regrettably can be dose limiting. In our patient, cemiplimab was successful in treating locally advanced cSCC, but treatment also resulted in devastating widespread eruptive keratoacanthoma. The mechanism of this kind of eruption has yet to be understood; we hypothesize that it likely involves T lymphocyte–driven inflammation and the interplay of molecular and immune-mediated pathways.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

- Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Shen J, Chang J, Mendenhall M, et al. Diverse cutaneous adverse eruptions caused by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immunotherapies: clinicalfeatures and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017751634. doi:10.1177/1758834017751634

- Bandino JP, Perry DM, Clarke CE, et al. Two cases of anti-programmed cell death 1-associated bullous pemphigoid-like disease and eruptive keratoacanthomas featuring combined histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E378-E380. doi:10.1111/jdv.14179

- Marsh RL, Kolodney JA, Iyengar S, et al. Formation of eruptive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas after programmed cell death protein-1 blockade. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.024

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, et al. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2009. doi:10.3390/ijms20082009

- Gambichler T, Gnielka M, Rüddel I, et al. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1199-1204. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2015-x

- Patel R, Chang ALS. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:477-482. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00426-w

- Rozeman EA, Blank CU. Combining checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:879-882. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0482-7

- Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:20-23. doi:10.3816/CGC.2009.n.003

- Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:243-251. doi:10.1111/ced.13751

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of cSCC is complex and possibly involves contrasting roles of leukocyte subpopulations.8 The increased incidence of cSCC in the immunocompromised population,8 PD-L1 overexpression in cSCC,9,10 and successful treatment of cSCC with PD-1 inhibition10 all suggest that inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways is pivotal in tumor pathogenesis. However, increased inflammation, particularly inflammation driven by T lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, also is believed to play a key role in the formation of cSCCs, including the degeneration of actinic keratosis into cSCC. Moreover, because keratoacanthomas are believed to be a cSCC variant and also are associated with PD-L1 overexpression,9 it is perplexing that PD-1 blockade may result in eruptive keratoacanthoma in some patients while also treating locally advanced cSCC, as seen in our patient. Successful treatment of keratoacanthoma with anti-inflammatory intralesional or topical corticosteroids adds to this complicated picture.3

We hypothesize that the pathogenesis of invasive cSCC and keratoacanthoma shares certain immune-mediated mechanisms but also differs in distinct manners. To understand the relationship between systemic treatment of cSCC and eruptive keratoacanthoma, further research is required.

In addition, the RAS/BRAF/MEK oncogenic pathway may be involved in the development of cSCCs associated with anti-PD-1. It is hypothesized that BRAF and MEK inhibition increases T-cell infiltration and increases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells,11 thus increasing the susceptibility of those cells to PD-1 blockade. Further supporting a relationship between the RAS/BRAF/MEK and PD-1 pathways, BRAF inhibitors are associated with development of SCCs and verrucal keratosis by upregulation of the RAS pathway.12,13 Perhaps a common mechanism underlying these pathways results in their shared association for an increased risk for cSCC upon blockade. More research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying biochemical mechanism of immunotherapy and formation of SCCs, such as keratoacanthoma.

Treatment of solitary keratoacanthoma often involves surgical excision; however, the sheer number of lesions in eruptive keratoacanthoma presents a larger dilemma. Because oral systemic retinoids have been shown to be most effective for treating eruptive keratoacanthoma, they are considered first-line therapy as monotherapy or in combination with surgical excision.3 Other treatment options include intralesional or topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and cryotherapy.3,6

The development of ICIs has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous malignancy, yet we have a great deal more to comprehend on the systemic effects of these medications. Although IRAEs may signal a better response to therapy, some of these effects regrettably can be dose limiting. In our patient, cemiplimab was successful in treating locally advanced cSCC, but treatment also resulted in devastating widespread eruptive keratoacanthoma. The mechanism of this kind of eruption has yet to be understood; we hypothesize that it likely involves T lymphocyte–driven inflammation and the interplay of molecular and immune-mediated pathways.

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of cSCC is complex and possibly involves contrasting roles of leukocyte subpopulations.8 The increased incidence of cSCC in the immunocompromised population,8 PD-L1 overexpression in cSCC,9,10 and successful treatment of cSCC with PD-1 inhibition10 all suggest that inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways is pivotal in tumor pathogenesis. However, increased inflammation, particularly inflammation driven by T lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, also is believed to play a key role in the formation of cSCCs, including the degeneration of actinic keratosis into cSCC. Moreover, because keratoacanthomas are believed to be a cSCC variant and also are associated with PD-L1 overexpression,9 it is perplexing that PD-1 blockade may result in eruptive keratoacanthoma in some patients while also treating locally advanced cSCC, as seen in our patient. Successful treatment of keratoacanthoma with anti-inflammatory intralesional or topical corticosteroids adds to this complicated picture.3

We hypothesize that the pathogenesis of invasive cSCC and keratoacanthoma shares certain immune-mediated mechanisms but also differs in distinct manners. To understand the relationship between systemic treatment of cSCC and eruptive keratoacanthoma, further research is required.

In addition, the RAS/BRAF/MEK oncogenic pathway may be involved in the development of cSCCs associated with anti-PD-1. It is hypothesized that BRAF and MEK inhibition increases T-cell infiltration and increases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells,11 thus increasing the susceptibility of those cells to PD-1 blockade. Further supporting a relationship between the RAS/BRAF/MEK and PD-1 pathways, BRAF inhibitors are associated with development of SCCs and verrucal keratosis by upregulation of the RAS pathway.12,13 Perhaps a common mechanism underlying these pathways results in their shared association for an increased risk for cSCC upon blockade. More research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying biochemical mechanism of immunotherapy and formation of SCCs, such as keratoacanthoma.

Treatment of solitary keratoacanthoma often involves surgical excision; however, the sheer number of lesions in eruptive keratoacanthoma presents a larger dilemma. Because oral systemic retinoids have been shown to be most effective for treating eruptive keratoacanthoma, they are considered first-line therapy as monotherapy or in combination with surgical excision.3 Other treatment options include intralesional or topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and cryotherapy.3,6

The development of ICIs has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous malignancy, yet we have a great deal more to comprehend on the systemic effects of these medications. Although IRAEs may signal a better response to therapy, some of these effects regrettably can be dose limiting. In our patient, cemiplimab was successful in treating locally advanced cSCC, but treatment also resulted in devastating widespread eruptive keratoacanthoma. The mechanism of this kind of eruption has yet to be understood; we hypothesize that it likely involves T lymphocyte–driven inflammation and the interplay of molecular and immune-mediated pathways.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

- Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Shen J, Chang J, Mendenhall M, et al. Diverse cutaneous adverse eruptions caused by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immunotherapies: clinicalfeatures and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017751634. doi:10.1177/1758834017751634

- Bandino JP, Perry DM, Clarke CE, et al. Two cases of anti-programmed cell death 1-associated bullous pemphigoid-like disease and eruptive keratoacanthomas featuring combined histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E378-E380. doi:10.1111/jdv.14179

- Marsh RL, Kolodney JA, Iyengar S, et al. Formation of eruptive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas after programmed cell death protein-1 blockade. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.024

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, et al. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2009. doi:10.3390/ijms20082009

- Gambichler T, Gnielka M, Rüddel I, et al. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1199-1204. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2015-x

- Patel R, Chang ALS. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:477-482. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00426-w

- Rozeman EA, Blank CU. Combining checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:879-882. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0482-7

- Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:20-23. doi:10.3816/CGC.2009.n.003

- Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:243-251. doi:10.1111/ced.13751

- Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

- Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Shen J, Chang J, Mendenhall M, et al. Diverse cutaneous adverse eruptions caused by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immunotherapies: clinicalfeatures and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017751634. doi:10.1177/1758834017751634

- Bandino JP, Perry DM, Clarke CE, et al. Two cases of anti-programmed cell death 1-associated bullous pemphigoid-like disease and eruptive keratoacanthomas featuring combined histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E378-E380. doi:10.1111/jdv.14179

- Marsh RL, Kolodney JA, Iyengar S, et al. Formation of eruptive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas after programmed cell death protein-1 blockade. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.024

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, et al. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2009. doi:10.3390/ijms20082009

- Gambichler T, Gnielka M, Rüddel I, et al. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1199-1204. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2015-x

- Patel R, Chang ALS. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:477-482. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00426-w

- Rozeman EA, Blank CU. Combining checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:879-882. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0482-7

- Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:20-23. doi:10.3816/CGC.2009.n.003

- Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:243-251. doi:10.1111/ced.13751

Practice Points

- Immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors such as programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors, is associated with an array of immune-related adverse events that often manifest in a delayed and prolonged manner. They most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.

- Dermatologic adverse effects associated with PD-1 inhibitors include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.

- Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with PD-1 inhibitors such as cemiplimab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab.

Treatment of Angiosarcoma of the Head and Neck: A Systematic Review

Cutaneous angiosarcoma (cAS) is a rare malignancy arising from vascular or lymphatic tissue. It classically presents during the sixth or seventh decades of life as a raised purple papule or plaque on the head and neck areas.1 Primary cAS frequently mimics benign conditions, leading to delays in care. Such delays coupled with the aggressive nature of angiosarcomas leads to a poor prognosis. Five-year survival rates range from 11% to 50%, and more than half of patients die within 1 year of diagnosis.2-7

Currently, there is no consensus on the most effective treatments, as the rare nature of cAS has made the development of controlled clinical trials difficult. Wide local excision (WLE) is most frequently employed; however, the tumor’s infiltrative growth makes complete resection and negative surgical margins difficult to achieve.8 Recently, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been postulated as a treatment option. The tissue-sparing nature and intraoperative margin control of MMS may provide tumor eradication and cosmesis benefits reported with other cutaneous malignancies.9

Nearly all localized cASs are treated with surgical excision with or without adjuvant treatment modalities; however, it is unclear which of these modalities provide a survival benefit. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to compare treatment modalities for localized cAS of the head and neck regions and to compare treatments based on tumor stage.

METHODS

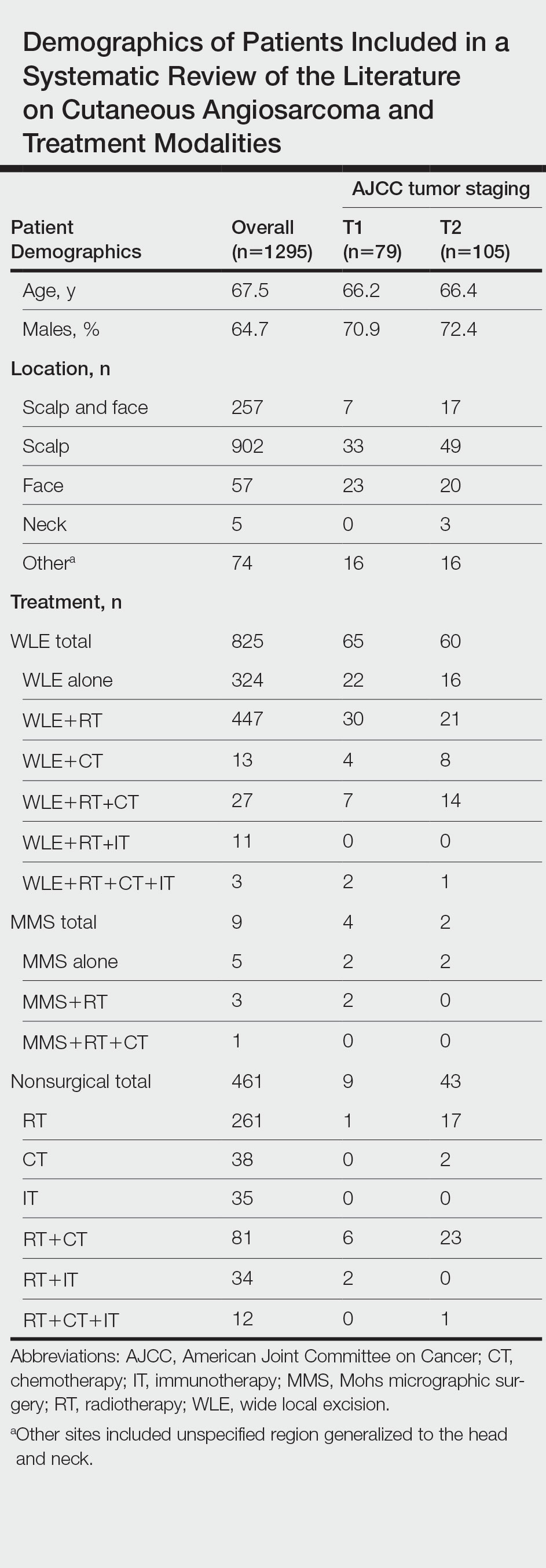

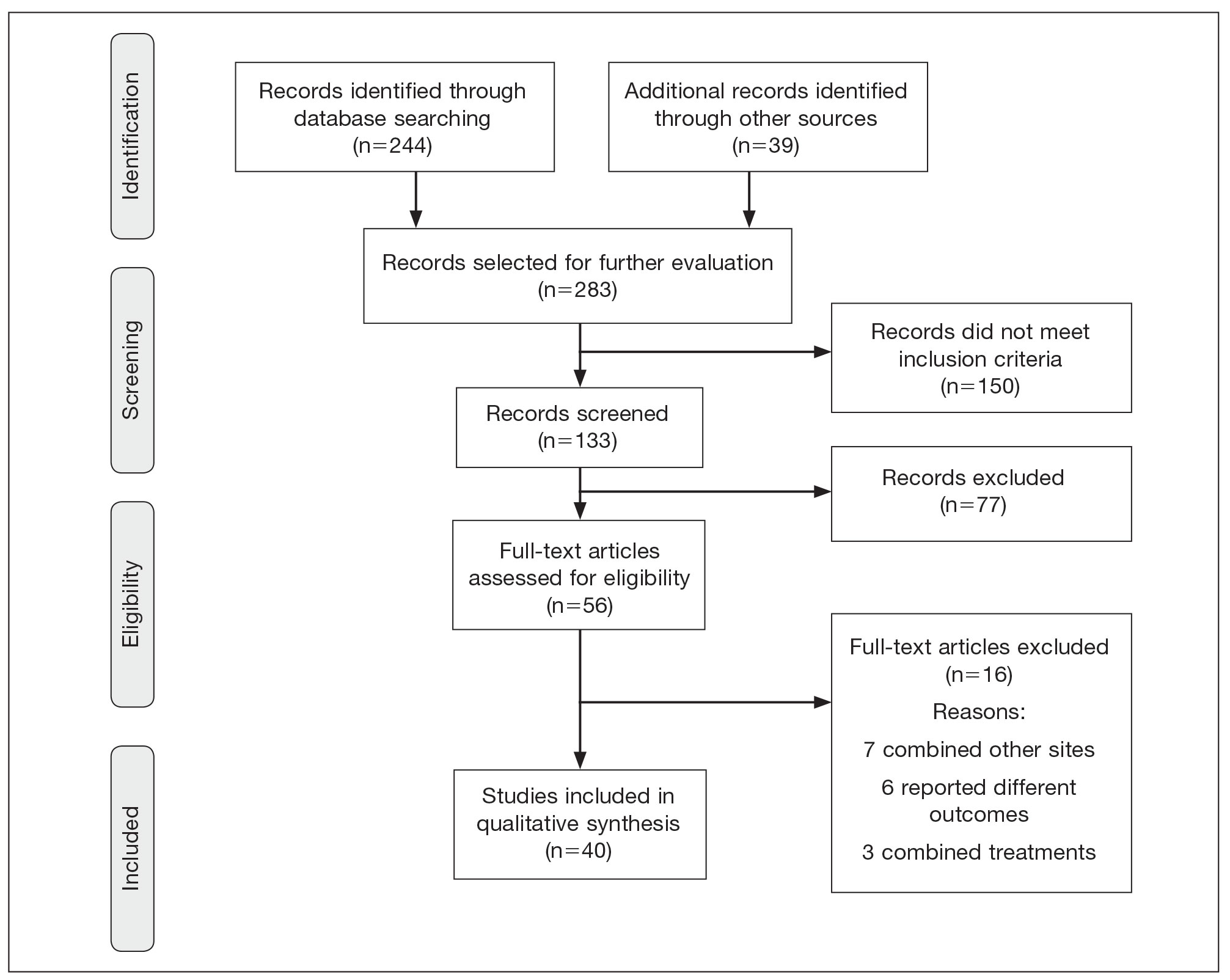

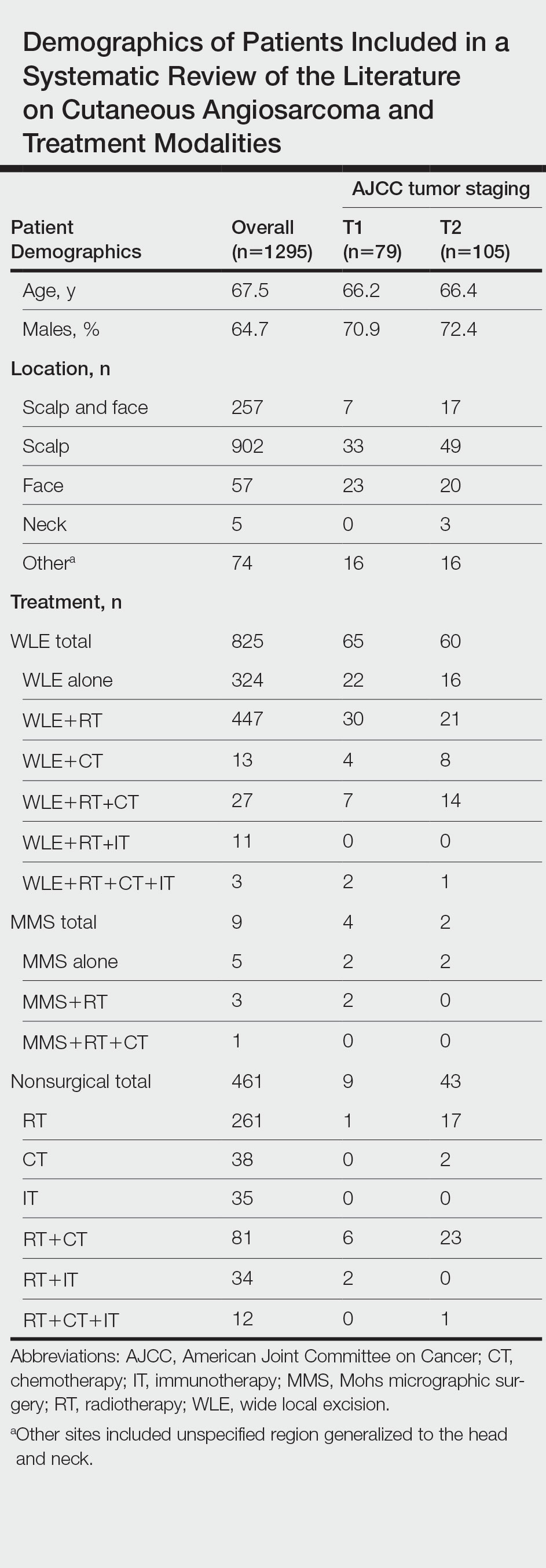

A literature search was performed to identify published studies indexed by MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, and PubMed from January 1, 1977, to May 8, 2020, reporting on cAS and treatment modalities used. The search was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines.5 Data extracted included patient demographics, tumor characteristics (including T1 [≤5 cm] and T2 [>5 cm and ≤10 cm] based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer soft tissue sarcoma staging criteria), treatments used, follow-up time, overall survival (OS) rates, and complications.10,11

Studies were required to (1) include participants with head and neck cAS; (2) report original patient data following cAS treatment with surgical (WLE or MMS) and/or nonsurgical modalities (chemotherapy [CT], radiotherapy [RT], immunotherapy [IT]); (3) report outcome data related to OS rates following treatment; and (4) have articles published in English. Given the rare nature of cAS, there was no limitation on the number of participants needed.

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies was used to assess the quality of studies.12 Higher scores indicate low risk of bias, while lower scores represent high risk of bias.

Continuous data were reported with means and SDs, while categorical variables were reported as percentages. Overall survival means and SDs were compared between treatment modalities using an independent sample t test with P<.05 considered statistically significant. Due to the heterogeneity of the data, a meta-analysis was not reported.

RESULTS

Literature Search and Risk of Bias Assessment

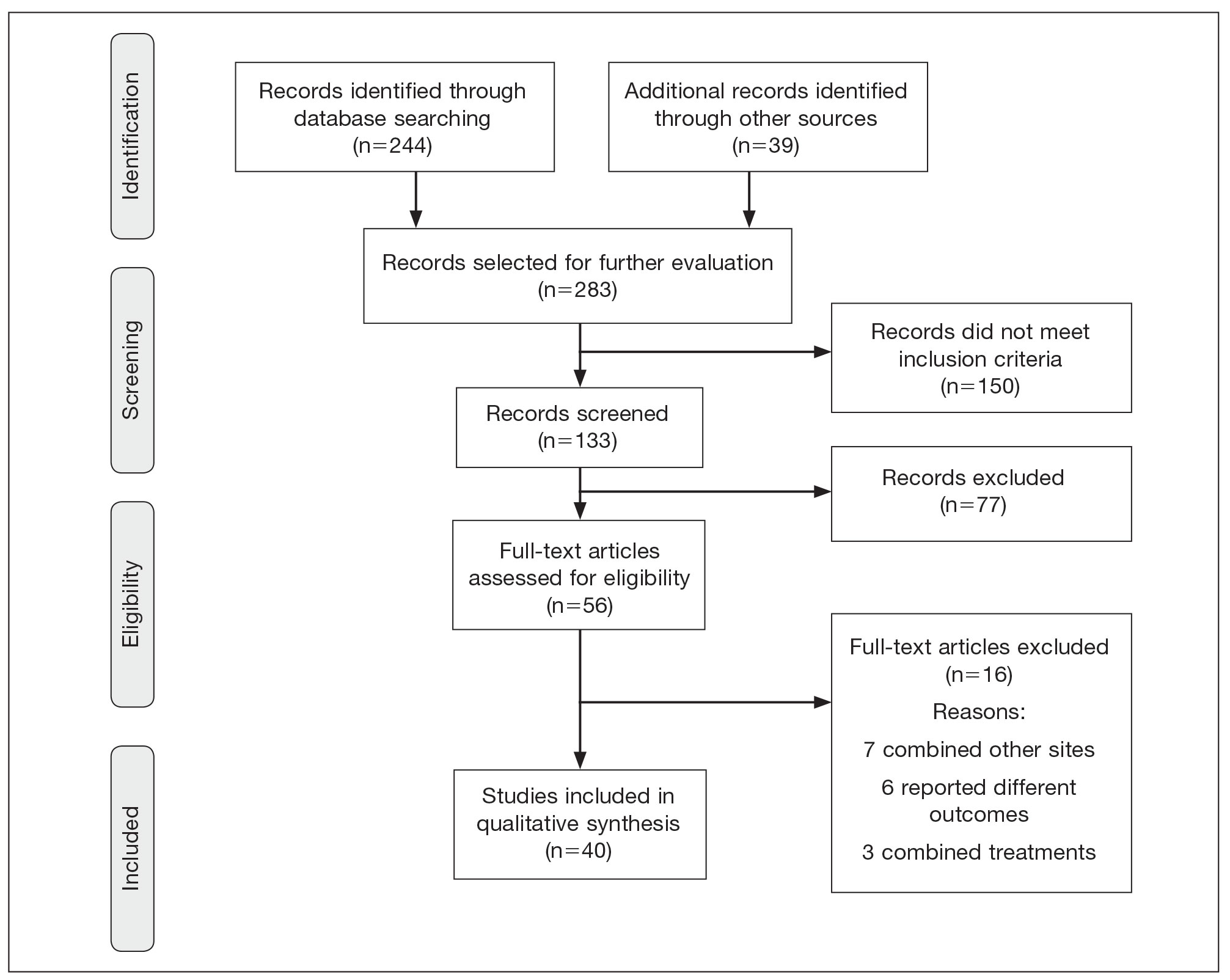

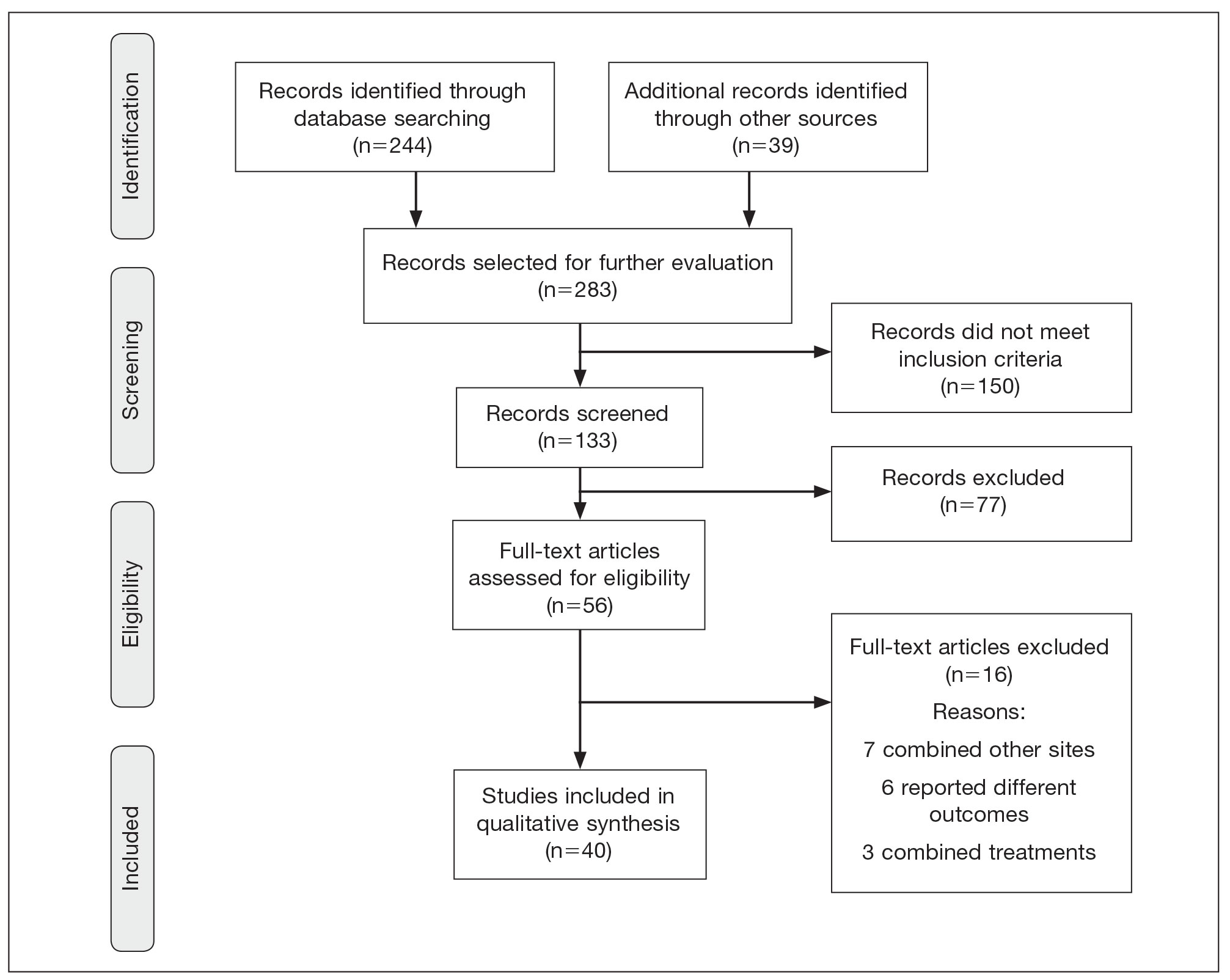

There were 283 manuscripts identified, 56 articles read in full, and 40 articles included in the review (Figure). Among the 16 studies not meeting inclusion criteria, 7 did not provide enough data to isolate head and neck cAS cases,1,13-18 6 did not report outcomes related to the current review,19-24 and 3 did not provide enough data to isolate different treatment outcomes.25-27 Among the included studies, 32 reported use of WLE: WLE alone (n=21)2,7,11,28-45; WLE with RT (n=24)2,3,11,28-31,33-36,38-41,43-51; WLE with CT (n=7)2,31,35,39,41,48,52; WLE with RT and CT (n=11)2,29,31,33-35,39,40,48,52,53; WLE with RT and IT (n=3)35,54,55; and WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=1).53 Nine studies reported MMS: MMS alone (n=5)39,56-59; MMS with RT (n=3)32,50,60,61; and MMS with RT and CT (n=1).51

Risk of bias assessment identified low risk in 3 articles. High risk was identified in 5 case reports,57-61 and 1 study did not describe patient selection.43 Clayton et al56 showed intermediate risk, given the study controlled for 1 factor.

Patient Demographics

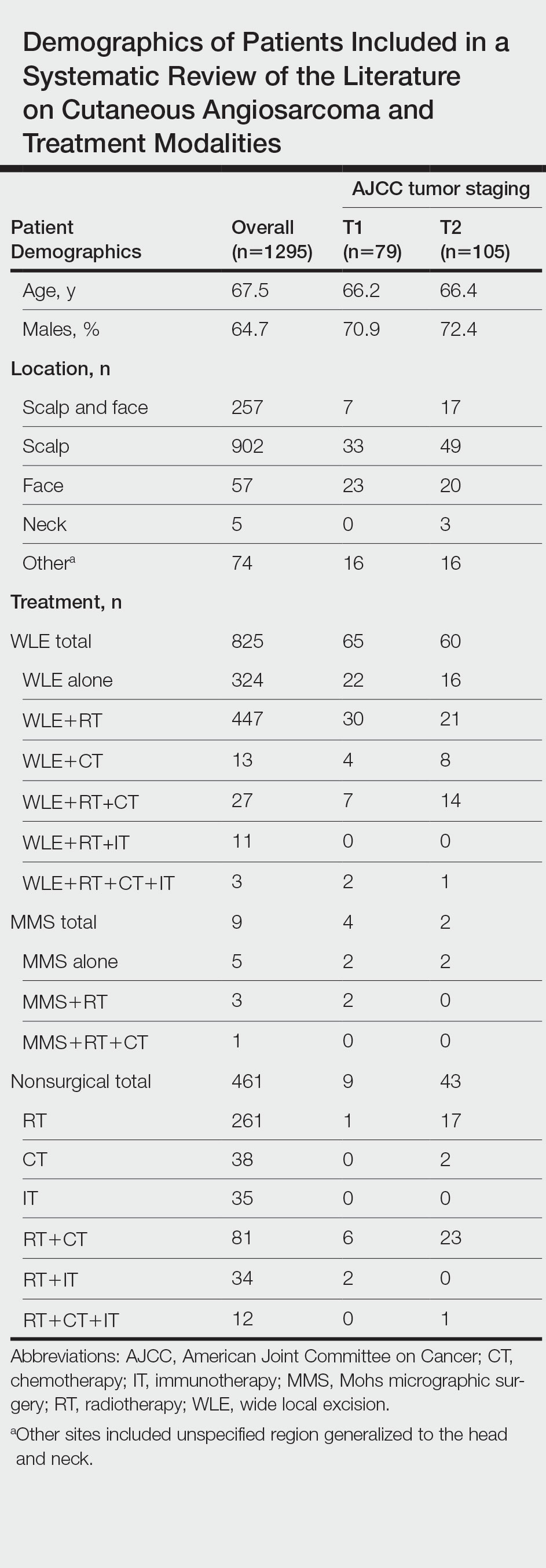

A total of 1295 patients were included. The pooled mean age of the patients was 67.5 years (range, 3–88 years), and 64.7% were male. There were 79 cases identified as T1 and 105 as T2. A total of 825 cases were treated using WLE with or without adjuvant therapy, while a total of 9 cases were treated using MMS with and without adjuvant therapies (Table). There were 461 cases treated without surgical excision: RT alone (n=261), CT alone (n=38), IT alone (n=35), RT with CT (n=81), RT with IT (n=34), and RT with CT and IT (n=12)(Table). The median follow-up period across all studies was 23.5 months (range, 1–228 months).

Comparison Between Surgical and Nonsurgical Modalities

Wide Local Excision—Wide local excision (n=825; 63.7%) alone or in combination with other therapies was the most frequently used treatment modality. The mean (SD) OS was longest for WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=3; 39.3 [24.1]), followed by WLE with RT (n=447; 35.9 [34.3] months), WLE with CT (n=13; 32.4 [30.2] months), WLE alone (n=324; 29.6 [34.1] months), WLE with RT and IT (n=11; 23.5 [4.9] months), and WLE with RT and CT (n=27; 20.7 [13.1] months).

Nonsurgical Modalities—Nonsurgical methods were used less frequently than surgical methods (n=461; 35.6%). The mean (SD) OS time in descending order was as follows: RT with CT and IT (n=12; 34.9 [1.2] months), RT with CT (n=81; 30.4 [37.8] months), IT alone (n=35; 25.7 [no SD reported] months), RT with IT (n=34; 20.5 [8.6] months), CT alone (n=38; 20.1 [15.9] months), and RT alone (n=261; 12.8 [8.3] months).

When comparing mean (SD) OS outcomes between surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities, only the addition of WLE to RT significantly increased OS when compared with RT alone (WLE, 35.9 [34.3] months; RT alone, 12.8 [8.3] months; P=.001). When WLE was added to CT or both RT and CT, there was no significant difference with OS when compared with CT alone (WLE with CT, 32.4 [30.2] months; CT alone, 20.1 [15.9] months; P=.065); or both RT and CT in combination (WLE with RT and CT, 20.7 [13.1] months; RT and CT, 30.4 [37.8] months; P=.204).

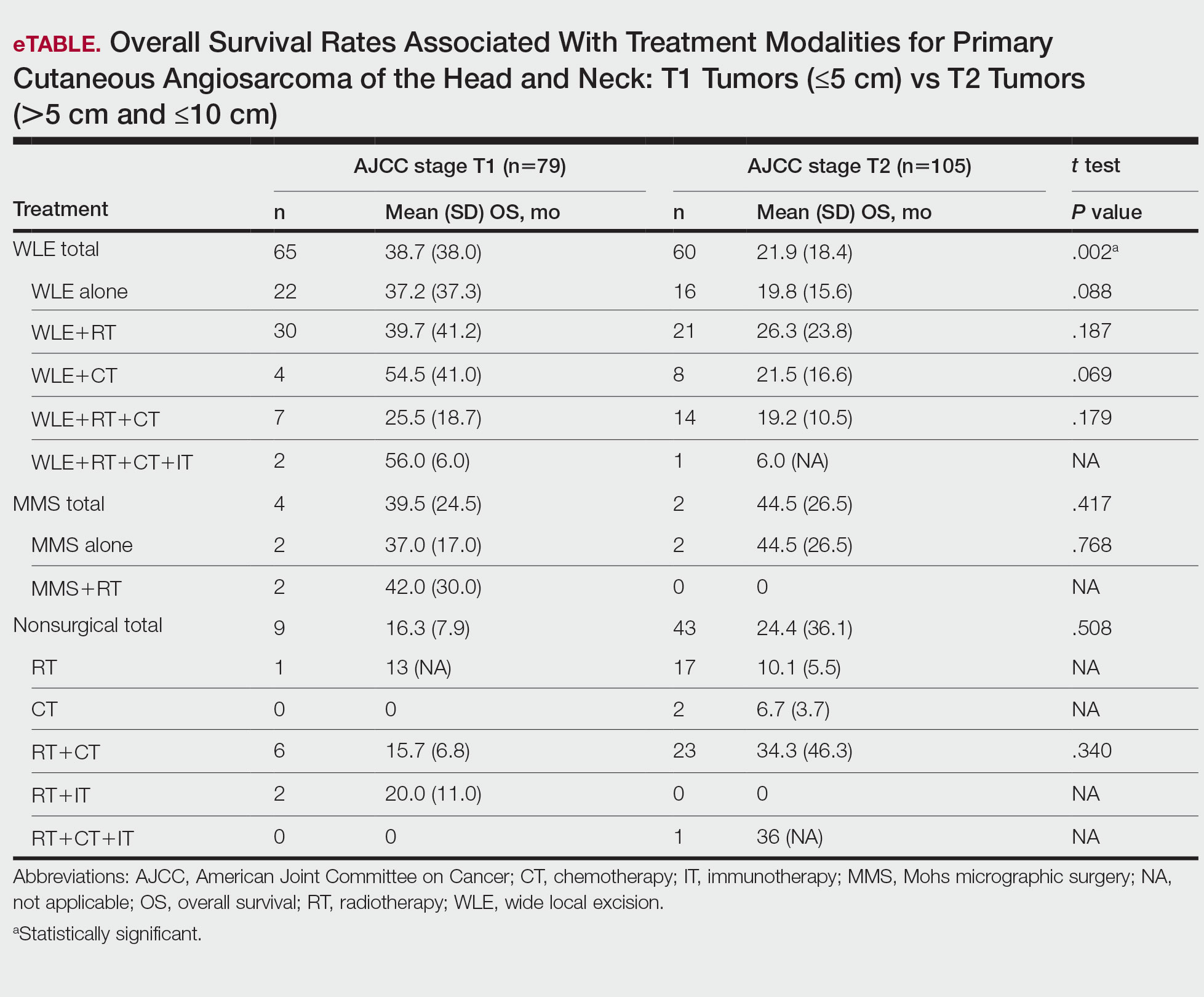

Comparison Between T1 and T2 cAS

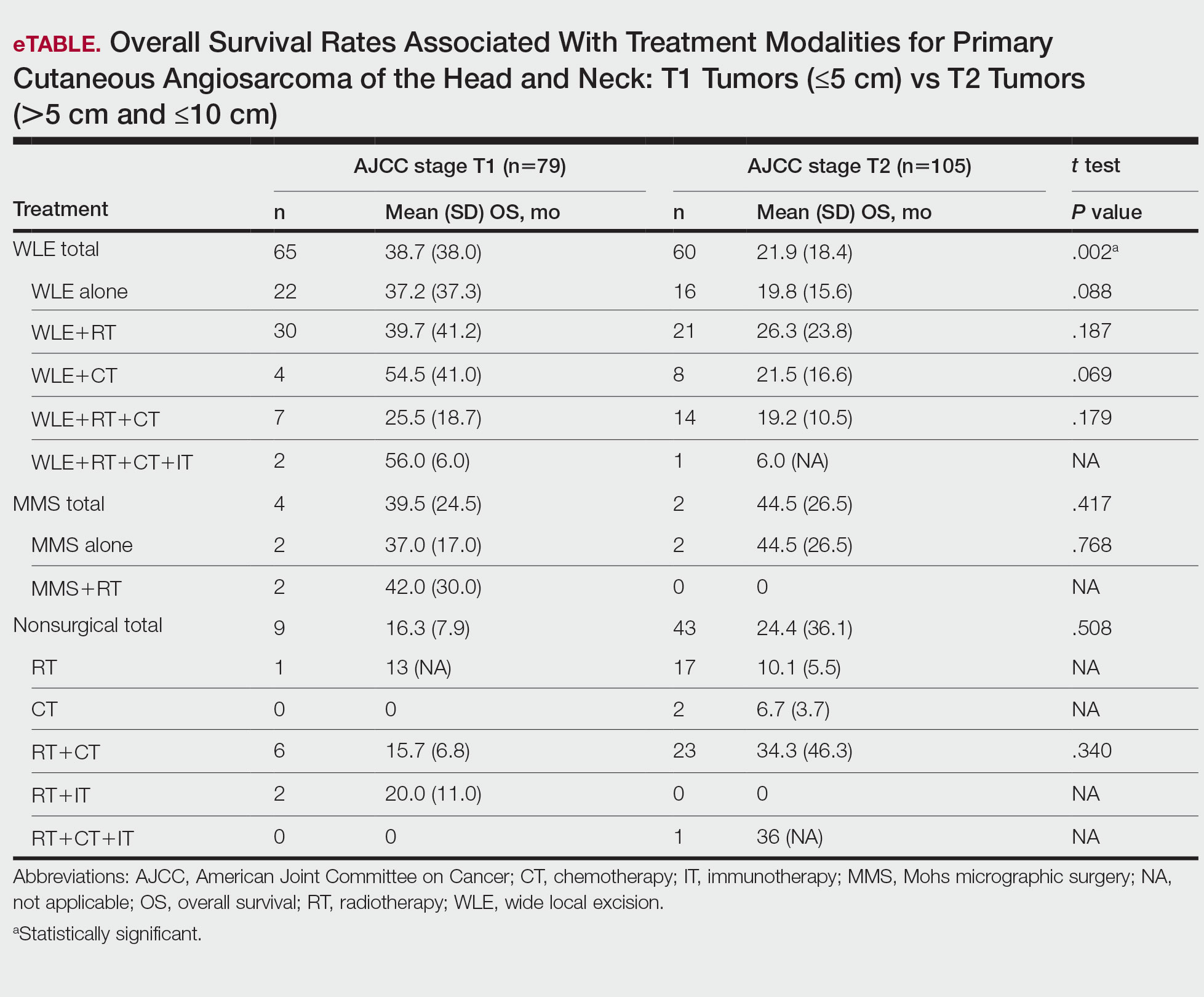

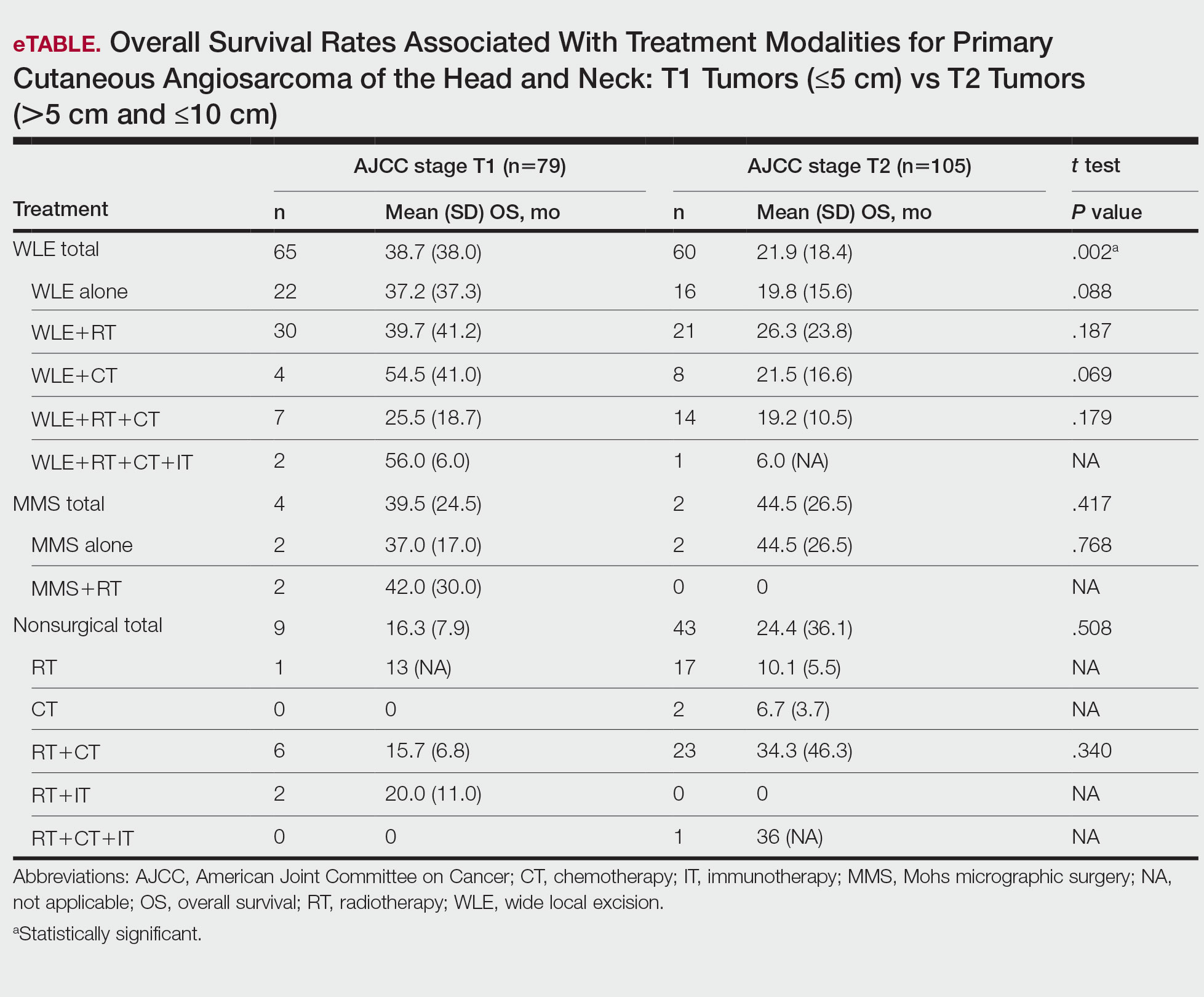

T1 Angiosarcoma—There were 79 patients identified as having T1 tumors across 16 studies.2,31,32,34,39-41,46,48-50,53,58-60,62 The mean (SD) OS was longest for WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=2; 56.0 [6.0] months), followed by WLE with CT (n=4; 54.5 [41.0] months); WLE with RT (n=30; 39.7 [41.2] months); WLE alone (n=22; 37.2 [37.3] months); WLE with both RT and CT (n=7; 25.5 [18.7] months); RT with IT (n=2; 20.0 [11.0] months); RT with CT (n=6; 15.7 [6.8] months); and RT alone (n=1; 13 [no SD]) months)(eTable).

T2 Angiosarcoma—There were 105 patients with T2 tumors in 15 studies.2,31,32,34,39-41,46,48-50,52,53,57,62 The mean (SD) OS for each treatment modality in descending order was as follows: RT with CT and IT (n=1; 36 [no SD reported] months); RT with CT (n=23; 34.3 [46.3] months); WLE with RT (n=21; 26.3 [23.8] months); WLE with CT (n=8; 21.5 [16.6] months); WLE alone (n=16; 19.8 [15.6] months); WLE with RT and CT (n=14; 19.2 [10.5] months); RT alone (n=17; 10.1 [5.5] months); CT alone (n=2; 6.7 [3.7] months); and WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=1; 6.0 [no SD] months)(eTable).

Mohs Micrographic Surgery—The use of MMS was only identified in case reports or small observational studies for a total of 9 patients. Five cASs were treated with MMS alone for a mean (SD) OS of 37 (21.5) months, with 4 reporting cAS staging: 2 were T158,59 (mean [SD] OS, 37.0 [17.0] months) and 2 were T2 tumors39,57 (mean [SD] OS, 44.5 [26.5] months). Mohs micrographic surgery with RT was used for 3 tumors (mean [SD] OS, 34.0 [26.9] months); 2 were T150,60 (mean [SD] OS, 42.0 [30.0] months) and 1 unreported staging (eTable).56 Mohs micrographic surgery with both RT and CT was used in 1 patient (unreported staging; OS, 82 months).51

Complications

Complications were rare and mainly associated with CT and RT. Four studies reported radiation dermatitis with RT.53,55,62,63 Two studies reported peripheral neuropathy and myelotoxicity with CT.35,51 Only 1 study reported poor wound healing due to surgical complications.29

COMMENT

Cutaneous angiosarcomas are rare and have limited treatment guidelines. Surgical excision does appear to be an effective adjunct to nonsurgical treatments, particularly WLE combined with RT, CT, and IT. Although MMS ultimately may be useful for cAS, the limited number and substantial heterogeneity of reported cases precludes definitive conclusions at this time.

Achieving margin control during WLE is associated with higher OS when treating angiosarcoma,36,46 which is particularly true for T1 tumors where margin control is imperative, and many cases are treated with a combination of WLE and RT. Overall survival times are lower for T2 tumors, as these tumors are larger and most likely have spread; therefore, more aggressive combination treatments were more prevalent. In these cases, complete margin control may be difficult to achieve and may not be as critical to the outcome if another form of adjuvant therapy can be administered promptly.24,64

When surgery is contraindicated, RT with or without CT was the most commonly reported treatment modality. However, these treatments were notably less effective than when used in combination with surgical resection. The use of RT alone has a recurrence rate reported up to 100% in certain studies, suggesting the need to utilize RT in combination with other modalities.23,39 It is important to note that RT often is used as monotherapy in palliative treatment, which may indirectly skew survival rates.2

Limitations of the study include a lack of randomized controlled trials. Most reports were retrospective reviews or case series, and tumor staging was sparsely reported. Finally, although MMS may provide utility in the treatment of cAS, the sample size of 9 precluded definitive conclusions from being formed about its efficacy.

CONCLUSION

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is rare and has limited data comparing different treatment modalities. The paucity of data currently limits definitive recommendations; however, both surgical and nonsurgical modalities have demonstrated potential efficacy in the treatment of cAS and may benefit from additional research. Clinicians should consider a multidisciplinary approach for patients with a diagnosis of cAS to tailor treatments on a case-by-case basis.

- Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Jimenez YD, Reolid A, et al. State of the art of Mohs surgery for rare cutaneous tumors in the Spanish Registry of Mohs Surgery (REGESMOHS). Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:321-325.

- Alqumber NA, Choi JW, Kang MK. The management and prognosis of facial and scalp angiosarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 15 patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83:55-62.

- Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, McGinn CJ, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer. 2003;98:1716-1726.

- Deyrup AT, McKenney JK, Tighiouart M, et al. Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas: a proposal for risk stratification based on 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:72-77.

- Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Angiosarcoma of soft tissue: a study of 80 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:683-697.

- Harbour P, Song DH. The skin and subcutaneous tissue. In: Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, et al, eds. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 11th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. Accessed April 24, 2023. https://accesssurgery.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2576§ionid=216206374

- Oashi K, Namikawa K, Tsutsumida A, et al. Surgery with curative intent is associated with prolonged survival in patients with cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp and face—a retrospective study of 38 untreated cases in the Japanese population. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:823-829.

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271.

- Amin M, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017.

- Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer. 1987;59:1046-1057.

- Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med. 2015;90:1067-1076.

- Lee BL, Chen CF, Chen PC, et al. Investigation of prognostic features in primary cutaneous and soft tissue angiosarcoma after surgical resection: a retrospective study. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(3 suppl 2):S41-S46.

- Shen CJ, Parzuchowski AS, Kummerlowe MN, et al. Combined modality therapy improves overall survival for angiosarcoma. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1235-1238.

- Breakey RW, Crowley TP, Anderson IB, et al. The surgical management of head and neck sarcoma: the Newcastle experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:78-84.

- Singla S, Papavasiliou P, Powers B, et al. Challenges in the treatment of angiosarcoma: a single institution experience. Am J Surg. 2014;208:254-259.

- Sasaki R, Soejima T, Kishi K, et al. Angiosarcoma treated with radiotherapy: impact of tumor type and size on outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1032-1040.

- Naka N, Ohsawa M, Tomita Y, et al. Angiosarcoma in Japan. A review of 99 cases. Cancer. 1995;75:989-996.

- DeMartelaere SL, Roberts D, Burgess MA, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy-specific and overall treatment outcomes in patients with cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face with periorbital involvement. Head Neck. 2008;30:639-646.

- Ward JR, Feigenberg SJ, Mendenhall NP, et al. Radiation therapy for angiosarcoma. Head Neck. 2003;25:873-878.

- Letsa I, Benson C, Al-Muderis O, et al. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp: effective systemic treatment in the older patient. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:276-280.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors: a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

- Patel SH, Hayden RE, Hinni ML, et al. Angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: the Mayo Clinic experience. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:335-340.

- Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK, Araujo D, et al. Outcomes after definitive treatment for cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Head Neck. 2011;33:661-667.

- Zhang Y, Yan Y, Zhu M, et al. Clinical outcomes in primary scalp angiosarcoma. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:5091-5096.

- Kamo R, Ishii M. Histological differentiation, histogenesis and prognosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Osaka City Med J. 2011;57:31-44.

- Ito T, Uchi H, Nakahara T, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and face: a single-center analysis of treatment outcomes in 43 patients in Japan. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1387-1394.

- Aust MR, Olsen KD, Lewis JE, et al. Angiosarcomas of the head and neck: clinical and pathologic characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:943-951.

- Buschmann A, Lehnhardt M, Toman N, et al. Surgical treatment of angiosarcoma of the scalp: less is more. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61:399-403.

- Cassidy RJ, Switchenko JM, Yushak ML, et al. The importance of surgery in scalp angiosarcomas. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:A3-A8.

- Choi JH, Ahn KC, Chang H, et al. Surgical treatment and prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp: a retrospective analysis of 14 patients in a single institution. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:321896.

- Chow TL, Kwan WW, Kwan CK. Treatment of cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp and face in Chinese patients: local experience at a regional hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2018;24:25-31.

- Donghi D, Kerl K, Dummer R, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: own experience over 13 years. clinical features, disease course and immunohistochemical profile. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1230-1234.

- Ferrari A, Casanova M, Bisogno G, et al. Malignant vascular tumors in children and adolescents: a report from the Italian and German Soft Tissue Sarcoma Cooperative Group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;39:109-114.

- Fujisawa Y, Nakamura Y, Kawachi Y, et al. Comparison between taxane-based chemotherapy with conventional surgery-based therapy for cutaneous angiosarcoma: a single-center experience. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:419-423.

- Hodgkinson DJ, Soule EH, Woods JE. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1979;44:1106-1113.

- Lim SY, Pyon JK, Mun GH, et al. Surgical treatment of angiosarcoma of the scalp with superficial parotidectomy. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:180-182.

- Maddox JC, Evans HL. Angiosarcoma of skin and soft tissue: a study of forty-four cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1907-1921.

- Mark RJ, Tran LM, Sercarz J, et al. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck. The UCLA experience 1955 through 1990. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:973-978.

- Morgan MB, Swann M, Somach S, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867-874.

- Mullins B, Hackman T. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;19:191-195.

- Ogawa K, Takahashi K, Asato Y, et al. Treatment and prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: a retrospective analysis of 48 patients. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:E1127-E1133.

- Panje WR, Moran WJ, Bostwick DG, et al. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck: review of 11 cases. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:1381-1384.

- Perez MC, Padhya TA, Messina JL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3391-3397.

- Veness M, Cooper S. Treatment of cutaneous angiosarcomas of the head and neck. Australas Radiol. 1995;39:277-281.

- Barttelbort SW, Stahl R, Ariyan S. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:55-59.

- Bernstein JM, Irish JC, Brown DH, et al. Survival outcomes for cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp versus face. Head Neck. 2017;39:1205-1211.

- Köhler HF, Neves RI, Brechtbühl ER, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck: report of 23 cases from a single institution. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:519-524.

- Morales PH, Lindberg RD, Barkley HT Jr. Soft tissue angiosarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7:1655-1659.

- Wollina U, Hansel G, Schönlebe J, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare aggressive malignant vascular tumour of the skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:964-968.

- Wollina U, Koch A, Hansel G, et al. A 10-year analysis of cutaneous mesenchymal tumors (sarcomas and related entities) in a skin cancer center. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1189-1197.

- Bien E, Stachowicz-Stencel T, Balcerska A, et al. Angiosarcoma in children - still uncontrollable oncological problem. The report of the Polish Paediatric Rare Tumours Study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2009;18:411-420.

- Suzuki G, Yamazaki H, Takenaka H, et al. Definitive radiation therapy for angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. In Vivo. 2016;30:921-926.

- Miki Y, Tada T, Kamo R, et al. Single institutional experience of the treatment of angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Br J Radiol. 2013;86:20130439.

- Ohguri T, Imada H, Nomoto S, et al. Angiosarcoma of the scalp treated with curative radiotherapy plus recombinant interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1446-1453.

- Clayton BD, Leshin B, Hitchcock MG, et al. Utility of rush paraffin-embedded tangential sections in the management of cutaneous neoplasms. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:671-678.

- Goldberg DJ, Kim YA. Angiosarcoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:156-158.

- Mikhail GR, Kelly AP Jr. Malignant angioendothelioma of the face. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1977;3:181-183.

- Muscarella VA. Angiosarcoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:1132-1133.

- Bullen R, Larson PO, Landeck AE, et al. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck managed by a combination of multiple biopsies to determine tumor margin and radiation therapy. report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:1105-1110.

- Wiwatwongwana D, White VA, Dolman PJ. Two cases of periocular cutaneous angiosarcoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:365-366.

- Morrison WH, Byers RM, Garden AS, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. A therapeutic dilemma. Cancer. 1995;76:319-327.

- Hata M, Wada H, Ogino I, et al. Radiation therapy for angiosarcoma of the scalp: treatment outcomes of total scalp irradiation with X-rays and electrons. Strahlenther Onkol. 2014;190:899-904.

- Hwang K, Kim MY, Lee SH. Recommendations for therapeutic decisions of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:E253-E256.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma (cAS) is a rare malignancy arising from vascular or lymphatic tissue. It classically presents during the sixth or seventh decades of life as a raised purple papule or plaque on the head and neck areas.1 Primary cAS frequently mimics benign conditions, leading to delays in care. Such delays coupled with the aggressive nature of angiosarcomas leads to a poor prognosis. Five-year survival rates range from 11% to 50%, and more than half of patients die within 1 year of diagnosis.2-7

Currently, there is no consensus on the most effective treatments, as the rare nature of cAS has made the development of controlled clinical trials difficult. Wide local excision (WLE) is most frequently employed; however, the tumor’s infiltrative growth makes complete resection and negative surgical margins difficult to achieve.8 Recently, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been postulated as a treatment option. The tissue-sparing nature and intraoperative margin control of MMS may provide tumor eradication and cosmesis benefits reported with other cutaneous malignancies.9

Nearly all localized cASs are treated with surgical excision with or without adjuvant treatment modalities; however, it is unclear which of these modalities provide a survival benefit. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to compare treatment modalities for localized cAS of the head and neck regions and to compare treatments based on tumor stage.

METHODS

A literature search was performed to identify published studies indexed by MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, and PubMed from January 1, 1977, to May 8, 2020, reporting on cAS and treatment modalities used. The search was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines.5 Data extracted included patient demographics, tumor characteristics (including T1 [≤5 cm] and T2 [>5 cm and ≤10 cm] based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer soft tissue sarcoma staging criteria), treatments used, follow-up time, overall survival (OS) rates, and complications.10,11

Studies were required to (1) include participants with head and neck cAS; (2) report original patient data following cAS treatment with surgical (WLE or MMS) and/or nonsurgical modalities (chemotherapy [CT], radiotherapy [RT], immunotherapy [IT]); (3) report outcome data related to OS rates following treatment; and (4) have articles published in English. Given the rare nature of cAS, there was no limitation on the number of participants needed.

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies was used to assess the quality of studies.12 Higher scores indicate low risk of bias, while lower scores represent high risk of bias.

Continuous data were reported with means and SDs, while categorical variables were reported as percentages. Overall survival means and SDs were compared between treatment modalities using an independent sample t test with P<.05 considered statistically significant. Due to the heterogeneity of the data, a meta-analysis was not reported.

RESULTS

Literature Search and Risk of Bias Assessment

There were 283 manuscripts identified, 56 articles read in full, and 40 articles included in the review (Figure). Among the 16 studies not meeting inclusion criteria, 7 did not provide enough data to isolate head and neck cAS cases,1,13-18 6 did not report outcomes related to the current review,19-24 and 3 did not provide enough data to isolate different treatment outcomes.25-27 Among the included studies, 32 reported use of WLE: WLE alone (n=21)2,7,11,28-45; WLE with RT (n=24)2,3,11,28-31,33-36,38-41,43-51; WLE with CT (n=7)2,31,35,39,41,48,52; WLE with RT and CT (n=11)2,29,31,33-35,39,40,48,52,53; WLE with RT and IT (n=3)35,54,55; and WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=1).53 Nine studies reported MMS: MMS alone (n=5)39,56-59; MMS with RT (n=3)32,50,60,61; and MMS with RT and CT (n=1).51

Risk of bias assessment identified low risk in 3 articles. High risk was identified in 5 case reports,57-61 and 1 study did not describe patient selection.43 Clayton et al56 showed intermediate risk, given the study controlled for 1 factor.

Patient Demographics

A total of 1295 patients were included. The pooled mean age of the patients was 67.5 years (range, 3–88 years), and 64.7% were male. There were 79 cases identified as T1 and 105 as T2. A total of 825 cases were treated using WLE with or without adjuvant therapy, while a total of 9 cases were treated using MMS with and without adjuvant therapies (Table). There were 461 cases treated without surgical excision: RT alone (n=261), CT alone (n=38), IT alone (n=35), RT with CT (n=81), RT with IT (n=34), and RT with CT and IT (n=12)(Table). The median follow-up period across all studies was 23.5 months (range, 1–228 months).

Comparison Between Surgical and Nonsurgical Modalities

Wide Local Excision—Wide local excision (n=825; 63.7%) alone or in combination with other therapies was the most frequently used treatment modality. The mean (SD) OS was longest for WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=3; 39.3 [24.1]), followed by WLE with RT (n=447; 35.9 [34.3] months), WLE with CT (n=13; 32.4 [30.2] months), WLE alone (n=324; 29.6 [34.1] months), WLE with RT and IT (n=11; 23.5 [4.9] months), and WLE with RT and CT (n=27; 20.7 [13.1] months).

Nonsurgical Modalities—Nonsurgical methods were used less frequently than surgical methods (n=461; 35.6%). The mean (SD) OS time in descending order was as follows: RT with CT and IT (n=12; 34.9 [1.2] months), RT with CT (n=81; 30.4 [37.8] months), IT alone (n=35; 25.7 [no SD reported] months), RT with IT (n=34; 20.5 [8.6] months), CT alone (n=38; 20.1 [15.9] months), and RT alone (n=261; 12.8 [8.3] months).

When comparing mean (SD) OS outcomes between surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities, only the addition of WLE to RT significantly increased OS when compared with RT alone (WLE, 35.9 [34.3] months; RT alone, 12.8 [8.3] months; P=.001). When WLE was added to CT or both RT and CT, there was no significant difference with OS when compared with CT alone (WLE with CT, 32.4 [30.2] months; CT alone, 20.1 [15.9] months; P=.065); or both RT and CT in combination (WLE with RT and CT, 20.7 [13.1] months; RT and CT, 30.4 [37.8] months; P=.204).

Comparison Between T1 and T2 cAS

T1 Angiosarcoma—There were 79 patients identified as having T1 tumors across 16 studies.2,31,32,34,39-41,46,48-50,53,58-60,62 The mean (SD) OS was longest for WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=2; 56.0 [6.0] months), followed by WLE with CT (n=4; 54.5 [41.0] months); WLE with RT (n=30; 39.7 [41.2] months); WLE alone (n=22; 37.2 [37.3] months); WLE with both RT and CT (n=7; 25.5 [18.7] months); RT with IT (n=2; 20.0 [11.0] months); RT with CT (n=6; 15.7 [6.8] months); and RT alone (n=1; 13 [no SD]) months)(eTable).

T2 Angiosarcoma—There were 105 patients with T2 tumors in 15 studies.2,31,32,34,39-41,46,48-50,52,53,57,62 The mean (SD) OS for each treatment modality in descending order was as follows: RT with CT and IT (n=1; 36 [no SD reported] months); RT with CT (n=23; 34.3 [46.3] months); WLE with RT (n=21; 26.3 [23.8] months); WLE with CT (n=8; 21.5 [16.6] months); WLE alone (n=16; 19.8 [15.6] months); WLE with RT and CT (n=14; 19.2 [10.5] months); RT alone (n=17; 10.1 [5.5] months); CT alone (n=2; 6.7 [3.7] months); and WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=1; 6.0 [no SD] months)(eTable).

Mohs Micrographic Surgery—The use of MMS was only identified in case reports or small observational studies for a total of 9 patients. Five cASs were treated with MMS alone for a mean (SD) OS of 37 (21.5) months, with 4 reporting cAS staging: 2 were T158,59 (mean [SD] OS, 37.0 [17.0] months) and 2 were T2 tumors39,57 (mean [SD] OS, 44.5 [26.5] months). Mohs micrographic surgery with RT was used for 3 tumors (mean [SD] OS, 34.0 [26.9] months); 2 were T150,60 (mean [SD] OS, 42.0 [30.0] months) and 1 unreported staging (eTable).56 Mohs micrographic surgery with both RT and CT was used in 1 patient (unreported staging; OS, 82 months).51

Complications

Complications were rare and mainly associated with CT and RT. Four studies reported radiation dermatitis with RT.53,55,62,63 Two studies reported peripheral neuropathy and myelotoxicity with CT.35,51 Only 1 study reported poor wound healing due to surgical complications.29

COMMENT

Cutaneous angiosarcomas are rare and have limited treatment guidelines. Surgical excision does appear to be an effective adjunct to nonsurgical treatments, particularly WLE combined with RT, CT, and IT. Although MMS ultimately may be useful for cAS, the limited number and substantial heterogeneity of reported cases precludes definitive conclusions at this time.

Achieving margin control during WLE is associated with higher OS when treating angiosarcoma,36,46 which is particularly true for T1 tumors where margin control is imperative, and many cases are treated with a combination of WLE and RT. Overall survival times are lower for T2 tumors, as these tumors are larger and most likely have spread; therefore, more aggressive combination treatments were more prevalent. In these cases, complete margin control may be difficult to achieve and may not be as critical to the outcome if another form of adjuvant therapy can be administered promptly.24,64

When surgery is contraindicated, RT with or without CT was the most commonly reported treatment modality. However, these treatments were notably less effective than when used in combination with surgical resection. The use of RT alone has a recurrence rate reported up to 100% in certain studies, suggesting the need to utilize RT in combination with other modalities.23,39 It is important to note that RT often is used as monotherapy in palliative treatment, which may indirectly skew survival rates.2

Limitations of the study include a lack of randomized controlled trials. Most reports were retrospective reviews or case series, and tumor staging was sparsely reported. Finally, although MMS may provide utility in the treatment of cAS, the sample size of 9 precluded definitive conclusions from being formed about its efficacy.

CONCLUSION

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is rare and has limited data comparing different treatment modalities. The paucity of data currently limits definitive recommendations; however, both surgical and nonsurgical modalities have demonstrated potential efficacy in the treatment of cAS and may benefit from additional research. Clinicians should consider a multidisciplinary approach for patients with a diagnosis of cAS to tailor treatments on a case-by-case basis.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma (cAS) is a rare malignancy arising from vascular or lymphatic tissue. It classically presents during the sixth or seventh decades of life as a raised purple papule or plaque on the head and neck areas.1 Primary cAS frequently mimics benign conditions, leading to delays in care. Such delays coupled with the aggressive nature of angiosarcomas leads to a poor prognosis. Five-year survival rates range from 11% to 50%, and more than half of patients die within 1 year of diagnosis.2-7

Currently, there is no consensus on the most effective treatments, as the rare nature of cAS has made the development of controlled clinical trials difficult. Wide local excision (WLE) is most frequently employed; however, the tumor’s infiltrative growth makes complete resection and negative surgical margins difficult to achieve.8 Recently, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been postulated as a treatment option. The tissue-sparing nature and intraoperative margin control of MMS may provide tumor eradication and cosmesis benefits reported with other cutaneous malignancies.9

Nearly all localized cASs are treated with surgical excision with or without adjuvant treatment modalities; however, it is unclear which of these modalities provide a survival benefit. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to compare treatment modalities for localized cAS of the head and neck regions and to compare treatments based on tumor stage.

METHODS

A literature search was performed to identify published studies indexed by MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, and PubMed from January 1, 1977, to May 8, 2020, reporting on cAS and treatment modalities used. The search was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines.5 Data extracted included patient demographics, tumor characteristics (including T1 [≤5 cm] and T2 [>5 cm and ≤10 cm] based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer soft tissue sarcoma staging criteria), treatments used, follow-up time, overall survival (OS) rates, and complications.10,11

Studies were required to (1) include participants with head and neck cAS; (2) report original patient data following cAS treatment with surgical (WLE or MMS) and/or nonsurgical modalities (chemotherapy [CT], radiotherapy [RT], immunotherapy [IT]); (3) report outcome data related to OS rates following treatment; and (4) have articles published in English. Given the rare nature of cAS, there was no limitation on the number of participants needed.

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies was used to assess the quality of studies.12 Higher scores indicate low risk of bias, while lower scores represent high risk of bias.

Continuous data were reported with means and SDs, while categorical variables were reported as percentages. Overall survival means and SDs were compared between treatment modalities using an independent sample t test with P<.05 considered statistically significant. Due to the heterogeneity of the data, a meta-analysis was not reported.

RESULTS

Literature Search and Risk of Bias Assessment

There were 283 manuscripts identified, 56 articles read in full, and 40 articles included in the review (Figure). Among the 16 studies not meeting inclusion criteria, 7 did not provide enough data to isolate head and neck cAS cases,1,13-18 6 did not report outcomes related to the current review,19-24 and 3 did not provide enough data to isolate different treatment outcomes.25-27 Among the included studies, 32 reported use of WLE: WLE alone (n=21)2,7,11,28-45; WLE with RT (n=24)2,3,11,28-31,33-36,38-41,43-51; WLE with CT (n=7)2,31,35,39,41,48,52; WLE with RT and CT (n=11)2,29,31,33-35,39,40,48,52,53; WLE with RT and IT (n=3)35,54,55; and WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=1).53 Nine studies reported MMS: MMS alone (n=5)39,56-59; MMS with RT (n=3)32,50,60,61; and MMS with RT and CT (n=1).51

Risk of bias assessment identified low risk in 3 articles. High risk was identified in 5 case reports,57-61 and 1 study did not describe patient selection.43 Clayton et al56 showed intermediate risk, given the study controlled for 1 factor.

Patient Demographics

A total of 1295 patients were included. The pooled mean age of the patients was 67.5 years (range, 3–88 years), and 64.7% were male. There were 79 cases identified as T1 and 105 as T2. A total of 825 cases were treated using WLE with or without adjuvant therapy, while a total of 9 cases were treated using MMS with and without adjuvant therapies (Table). There were 461 cases treated without surgical excision: RT alone (n=261), CT alone (n=38), IT alone (n=35), RT with CT (n=81), RT with IT (n=34), and RT with CT and IT (n=12)(Table). The median follow-up period across all studies was 23.5 months (range, 1–228 months).

Comparison Between Surgical and Nonsurgical Modalities

Wide Local Excision—Wide local excision (n=825; 63.7%) alone or in combination with other therapies was the most frequently used treatment modality. The mean (SD) OS was longest for WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=3; 39.3 [24.1]), followed by WLE with RT (n=447; 35.9 [34.3] months), WLE with CT (n=13; 32.4 [30.2] months), WLE alone (n=324; 29.6 [34.1] months), WLE with RT and IT (n=11; 23.5 [4.9] months), and WLE with RT and CT (n=27; 20.7 [13.1] months).

Nonsurgical Modalities—Nonsurgical methods were used less frequently than surgical methods (n=461; 35.6%). The mean (SD) OS time in descending order was as follows: RT with CT and IT (n=12; 34.9 [1.2] months), RT with CT (n=81; 30.4 [37.8] months), IT alone (n=35; 25.7 [no SD reported] months), RT with IT (n=34; 20.5 [8.6] months), CT alone (n=38; 20.1 [15.9] months), and RT alone (n=261; 12.8 [8.3] months).

When comparing mean (SD) OS outcomes between surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities, only the addition of WLE to RT significantly increased OS when compared with RT alone (WLE, 35.9 [34.3] months; RT alone, 12.8 [8.3] months; P=.001). When WLE was added to CT or both RT and CT, there was no significant difference with OS when compared with CT alone (WLE with CT, 32.4 [30.2] months; CT alone, 20.1 [15.9] months; P=.065); or both RT and CT in combination (WLE with RT and CT, 20.7 [13.1] months; RT and CT, 30.4 [37.8] months; P=.204).

Comparison Between T1 and T2 cAS

T1 Angiosarcoma—There were 79 patients identified as having T1 tumors across 16 studies.2,31,32,34,39-41,46,48-50,53,58-60,62 The mean (SD) OS was longest for WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=2; 56.0 [6.0] months), followed by WLE with CT (n=4; 54.5 [41.0] months); WLE with RT (n=30; 39.7 [41.2] months); WLE alone (n=22; 37.2 [37.3] months); WLE with both RT and CT (n=7; 25.5 [18.7] months); RT with IT (n=2; 20.0 [11.0] months); RT with CT (n=6; 15.7 [6.8] months); and RT alone (n=1; 13 [no SD]) months)(eTable).

T2 Angiosarcoma—There were 105 patients with T2 tumors in 15 studies.2,31,32,34,39-41,46,48-50,52,53,57,62 The mean (SD) OS for each treatment modality in descending order was as follows: RT with CT and IT (n=1; 36 [no SD reported] months); RT with CT (n=23; 34.3 [46.3] months); WLE with RT (n=21; 26.3 [23.8] months); WLE with CT (n=8; 21.5 [16.6] months); WLE alone (n=16; 19.8 [15.6] months); WLE with RT and CT (n=14; 19.2 [10.5] months); RT alone (n=17; 10.1 [5.5] months); CT alone (n=2; 6.7 [3.7] months); and WLE with RT, CT, and IT (n=1; 6.0 [no SD] months)(eTable).

Mohs Micrographic Surgery—The use of MMS was only identified in case reports or small observational studies for a total of 9 patients. Five cASs were treated with MMS alone for a mean (SD) OS of 37 (21.5) months, with 4 reporting cAS staging: 2 were T158,59 (mean [SD] OS, 37.0 [17.0] months) and 2 were T2 tumors39,57 (mean [SD] OS, 44.5 [26.5] months). Mohs micrographic surgery with RT was used for 3 tumors (mean [SD] OS, 34.0 [26.9] months); 2 were T150,60 (mean [SD] OS, 42.0 [30.0] months) and 1 unreported staging (eTable).56 Mohs micrographic surgery with both RT and CT was used in 1 patient (unreported staging; OS, 82 months).51

Complications

Complications were rare and mainly associated with CT and RT. Four studies reported radiation dermatitis with RT.53,55,62,63 Two studies reported peripheral neuropathy and myelotoxicity with CT.35,51 Only 1 study reported poor wound healing due to surgical complications.29

COMMENT

Cutaneous angiosarcomas are rare and have limited treatment guidelines. Surgical excision does appear to be an effective adjunct to nonsurgical treatments, particularly WLE combined with RT, CT, and IT. Although MMS ultimately may be useful for cAS, the limited number and substantial heterogeneity of reported cases precludes definitive conclusions at this time.

Achieving margin control during WLE is associated with higher OS when treating angiosarcoma,36,46 which is particularly true for T1 tumors where margin control is imperative, and many cases are treated with a combination of WLE and RT. Overall survival times are lower for T2 tumors, as these tumors are larger and most likely have spread; therefore, more aggressive combination treatments were more prevalent. In these cases, complete margin control may be difficult to achieve and may not be as critical to the outcome if another form of adjuvant therapy can be administered promptly.24,64

When surgery is contraindicated, RT with or without CT was the most commonly reported treatment modality. However, these treatments were notably less effective than when used in combination with surgical resection. The use of RT alone has a recurrence rate reported up to 100% in certain studies, suggesting the need to utilize RT in combination with other modalities.23,39 It is important to note that RT often is used as monotherapy in palliative treatment, which may indirectly skew survival rates.2

Limitations of the study include a lack of randomized controlled trials. Most reports were retrospective reviews or case series, and tumor staging was sparsely reported. Finally, although MMS may provide utility in the treatment of cAS, the sample size of 9 precluded definitive conclusions from being formed about its efficacy.

CONCLUSION

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is rare and has limited data comparing different treatment modalities. The paucity of data currently limits definitive recommendations; however, both surgical and nonsurgical modalities have demonstrated potential efficacy in the treatment of cAS and may benefit from additional research. Clinicians should consider a multidisciplinary approach for patients with a diagnosis of cAS to tailor treatments on a case-by-case basis.

- Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Jimenez YD, Reolid A, et al. State of the art of Mohs surgery for rare cutaneous tumors in the Spanish Registry of Mohs Surgery (REGESMOHS). Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:321-325.

- Alqumber NA, Choi JW, Kang MK. The management and prognosis of facial and scalp angiosarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 15 patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83:55-62.

- Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, McGinn CJ, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer. 2003;98:1716-1726.

- Deyrup AT, McKenney JK, Tighiouart M, et al. Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas: a proposal for risk stratification based on 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:72-77.

- Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Angiosarcoma of soft tissue: a study of 80 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:683-697.

- Harbour P, Song DH. The skin and subcutaneous tissue. In: Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, et al, eds. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 11th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. Accessed April 24, 2023. https://accesssurgery.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2576§ionid=216206374

- Oashi K, Namikawa K, Tsutsumida A, et al. Surgery with curative intent is associated with prolonged survival in patients with cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp and face—a retrospective study of 38 untreated cases in the Japanese population. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:823-829.

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271.

- Amin M, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017.

- Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer. 1987;59:1046-1057.

- Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med. 2015;90:1067-1076.

- Lee BL, Chen CF, Chen PC, et al. Investigation of prognostic features in primary cutaneous and soft tissue angiosarcoma after surgical resection: a retrospective study. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(3 suppl 2):S41-S46.

- Shen CJ, Parzuchowski AS, Kummerlowe MN, et al. Combined modality therapy improves overall survival for angiosarcoma. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1235-1238.

- Breakey RW, Crowley TP, Anderson IB, et al. The surgical management of head and neck sarcoma: the Newcastle experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:78-84.

- Singla S, Papavasiliou P, Powers B, et al. Challenges in the treatment of angiosarcoma: a single institution experience. Am J Surg. 2014;208:254-259.

- Sasaki R, Soejima T, Kishi K, et al. Angiosarcoma treated with radiotherapy: impact of tumor type and size on outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1032-1040.

- Naka N, Ohsawa M, Tomita Y, et al. Angiosarcoma in Japan. A review of 99 cases. Cancer. 1995;75:989-996.

- DeMartelaere SL, Roberts D, Burgess MA, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy-specific and overall treatment outcomes in patients with cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face with periorbital involvement. Head Neck. 2008;30:639-646.

- Ward JR, Feigenberg SJ, Mendenhall NP, et al. Radiation therapy for angiosarcoma. Head Neck. 2003;25:873-878.

- Letsa I, Benson C, Al-Muderis O, et al. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp: effective systemic treatment in the older patient. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:276-280.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors: a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

- Patel SH, Hayden RE, Hinni ML, et al. Angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: the Mayo Clinic experience. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:335-340.

- Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK, Araujo D, et al. Outcomes after definitive treatment for cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Head Neck. 2011;33:661-667.

- Zhang Y, Yan Y, Zhu M, et al. Clinical outcomes in primary scalp angiosarcoma. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:5091-5096.

- Kamo R, Ishii M. Histological differentiation, histogenesis and prognosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Osaka City Med J. 2011;57:31-44.

- Ito T, Uchi H, Nakahara T, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and face: a single-center analysis of treatment outcomes in 43 patients in Japan. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1387-1394.

- Aust MR, Olsen KD, Lewis JE, et al. Angiosarcomas of the head and neck: clinical and pathologic characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:943-951.

- Buschmann A, Lehnhardt M, Toman N, et al. Surgical treatment of angiosarcoma of the scalp: less is more. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61:399-403.

- Cassidy RJ, Switchenko JM, Yushak ML, et al. The importance of surgery in scalp angiosarcomas. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:A3-A8.