User login

Some with long COVID see relief after vaccination

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

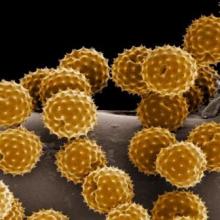

Could pollen be driving COVID-19 infections?

Some scientists say they’ve noticed a pattern to the recurring waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections around the globe: As pollen levels increased in outdoor air in 31 countries, COVID-19 cases accelerated.

Yet other recent studies point in the opposite direction, suggesting that peaks in pollen seasons coincide with a fall-off in the spread of some respiratory viruses, like COVID-19 and influenza. There’s even some evidence that pollen may compete with the virus that causes COVID-19 and may even help prevent infection.

So which is it? The answer may still be up in the air.

Doctors don’t fully understand what makes some viruses – like the ones that cause the flu – circulate in seasonal patterns.

There are, of course, many theories. These revolve around things like temperature and humidity – viruses tend to prefer colder, drier air – something that’s thought to help them spread more easily in the winter months. People are exposed to less sunlight during the winter, as they spend more time indoors, and the earth points away from the sun, providing some natural shielding. That may play a role because ultraviolet light from the sun acts like a natural disinfectant and may help keep circulating viral levels down.

In addition, exposure to sunlight helps the body make vitamin D, which may help keep our immune responses strong. Extreme temperatures – both cold and hot – also change our behavior, so that we spend more time cloistered indoors, where we can more easily cough and sneeze on each other and generally swap more germs.

Spike in pollen, jump in infections

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds a new variable to this mix – pollen. It relies on data from 248 airborne pollen–monitoring sites in 31 countries. The study also took into account other effects, such as population density, temperature, humidity, and lockdown orders. The study authors found that, when pollen in an area spiked, so did infections, after an average lag of about 4 days. The study authors say pollen seemed to account for, on average, 44% of the infection rate variability between countries.

The study authors say pollen could be a culprit in respiratory infections, not because the viruses hitch a ride on pollen grains and travel into our mouth, eyes, and nose, but because pollen seems to perturb our immune defenses, even if a person isn’t allergic to it.

“When we inhale pollen, they end up on our nasal mucosa, and here they diminish the expression of genes that are important for the defense against airborne viruses,” study author Stefanie Gilles, PhD, chair of environmental medicine at the Technical University of Munich, said in a press conference.

In a study published last year, Dr. Gilles found that mice exposed to pollen made less interferon and other protective chemical signals to the immune system. Those then infected with respiratory syncytial virus had more virus in their bodies, compared with mice not exposed to pollen. She seemed to see the same effect in human volunteers.

The study authors think pollen may cause the body to drop its defenses against the airborne virus that causes COVID-19, too.

“If you’re in a crowded room, and other people are there that are asymptomatic, and you’ve just been breathing in pollen all day long, chances are that you’re going to be more susceptible to the virus,” says Lewis Ziska, PhD, a plant physiologist who studies pollen, climate change, and health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York. “Having a mask is obviously really critical in that regard.”

Masks do a great job of blocking pollen, so wearing one is even more important when pollen and viruses are floating around, he says.

Other researchers, however, say that, while the study raises some interesting questions, it can’t prove that pollen is increasing COVID-19 infections.

“Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one causes the other,” says Martijn Hoogeveen, PhD, a professor of technical sciences and environment at the Open University in the Netherlands.

Dr. Hoogeveen’s recent study, published in Science of the Total Environment, found that the arrival of pollen season in the Netherlands coincides with the end of flu season, and that COVID-19 infection peaks tend to follow a similar pattern – exactly the opposite of the PNAS study.

Another preprint study, which focused on the Chicago area, found the same thing – as pollen climbs, flu cases drop. The researchers behind that study think pollen may actually compete with viruses in our airways, helping to block them from infecting our cells.

Patterns may be hard to nail down

Why did these studies reach such different conclusions?

Dr. Hoogeveen’s paper focused on a single country and looked at the incidence of flu infections over four seasons, from 2016 to 2020, while the PNAS study collected data on pollen from January through the first week of April 2020.

He thinks that a single season, or really part of a season, may not be long enough to see meaningful patterns, especially considering that this new-to-humans virus was spreading quickly at nearly the same time. He says it will be interesting to follow what happens with COVID-19 infections and pollen in the coming months and years.

Dr. Hoogeveen says that in a large study spanning so many countries it would have been nearly impossible to account for differences in pandemic control strategies. Some countries embraced the use of masks, stay-at-home orders, and social distancing, for example, while others took less stringent measures in order to let the virus run its course in pursuit of herd immunity.

Limiting the study area to a single country or city, he says, helps researchers better understand all the variables that might have been in play along with pollen.

“There is no scientific consensus yet, about what it is driving, and that’s what makes it such an interesting field,” he says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some scientists say they’ve noticed a pattern to the recurring waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections around the globe: As pollen levels increased in outdoor air in 31 countries, COVID-19 cases accelerated.

Yet other recent studies point in the opposite direction, suggesting that peaks in pollen seasons coincide with a fall-off in the spread of some respiratory viruses, like COVID-19 and influenza. There’s even some evidence that pollen may compete with the virus that causes COVID-19 and may even help prevent infection.

So which is it? The answer may still be up in the air.

Doctors don’t fully understand what makes some viruses – like the ones that cause the flu – circulate in seasonal patterns.

There are, of course, many theories. These revolve around things like temperature and humidity – viruses tend to prefer colder, drier air – something that’s thought to help them spread more easily in the winter months. People are exposed to less sunlight during the winter, as they spend more time indoors, and the earth points away from the sun, providing some natural shielding. That may play a role because ultraviolet light from the sun acts like a natural disinfectant and may help keep circulating viral levels down.

In addition, exposure to sunlight helps the body make vitamin D, which may help keep our immune responses strong. Extreme temperatures – both cold and hot – also change our behavior, so that we spend more time cloistered indoors, where we can more easily cough and sneeze on each other and generally swap more germs.

Spike in pollen, jump in infections

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds a new variable to this mix – pollen. It relies on data from 248 airborne pollen–monitoring sites in 31 countries. The study also took into account other effects, such as population density, temperature, humidity, and lockdown orders. The study authors found that, when pollen in an area spiked, so did infections, after an average lag of about 4 days. The study authors say pollen seemed to account for, on average, 44% of the infection rate variability between countries.

The study authors say pollen could be a culprit in respiratory infections, not because the viruses hitch a ride on pollen grains and travel into our mouth, eyes, and nose, but because pollen seems to perturb our immune defenses, even if a person isn’t allergic to it.

“When we inhale pollen, they end up on our nasal mucosa, and here they diminish the expression of genes that are important for the defense against airborne viruses,” study author Stefanie Gilles, PhD, chair of environmental medicine at the Technical University of Munich, said in a press conference.

In a study published last year, Dr. Gilles found that mice exposed to pollen made less interferon and other protective chemical signals to the immune system. Those then infected with respiratory syncytial virus had more virus in their bodies, compared with mice not exposed to pollen. She seemed to see the same effect in human volunteers.

The study authors think pollen may cause the body to drop its defenses against the airborne virus that causes COVID-19, too.

“If you’re in a crowded room, and other people are there that are asymptomatic, and you’ve just been breathing in pollen all day long, chances are that you’re going to be more susceptible to the virus,” says Lewis Ziska, PhD, a plant physiologist who studies pollen, climate change, and health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York. “Having a mask is obviously really critical in that regard.”

Masks do a great job of blocking pollen, so wearing one is even more important when pollen and viruses are floating around, he says.

Other researchers, however, say that, while the study raises some interesting questions, it can’t prove that pollen is increasing COVID-19 infections.

“Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one causes the other,” says Martijn Hoogeveen, PhD, a professor of technical sciences and environment at the Open University in the Netherlands.

Dr. Hoogeveen’s recent study, published in Science of the Total Environment, found that the arrival of pollen season in the Netherlands coincides with the end of flu season, and that COVID-19 infection peaks tend to follow a similar pattern – exactly the opposite of the PNAS study.

Another preprint study, which focused on the Chicago area, found the same thing – as pollen climbs, flu cases drop. The researchers behind that study think pollen may actually compete with viruses in our airways, helping to block them from infecting our cells.

Patterns may be hard to nail down

Why did these studies reach such different conclusions?

Dr. Hoogeveen’s paper focused on a single country and looked at the incidence of flu infections over four seasons, from 2016 to 2020, while the PNAS study collected data on pollen from January through the first week of April 2020.

He thinks that a single season, or really part of a season, may not be long enough to see meaningful patterns, especially considering that this new-to-humans virus was spreading quickly at nearly the same time. He says it will be interesting to follow what happens with COVID-19 infections and pollen in the coming months and years.

Dr. Hoogeveen says that in a large study spanning so many countries it would have been nearly impossible to account for differences in pandemic control strategies. Some countries embraced the use of masks, stay-at-home orders, and social distancing, for example, while others took less stringent measures in order to let the virus run its course in pursuit of herd immunity.

Limiting the study area to a single country or city, he says, helps researchers better understand all the variables that might have been in play along with pollen.

“There is no scientific consensus yet, about what it is driving, and that’s what makes it such an interesting field,” he says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some scientists say they’ve noticed a pattern to the recurring waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections around the globe: As pollen levels increased in outdoor air in 31 countries, COVID-19 cases accelerated.

Yet other recent studies point in the opposite direction, suggesting that peaks in pollen seasons coincide with a fall-off in the spread of some respiratory viruses, like COVID-19 and influenza. There’s even some evidence that pollen may compete with the virus that causes COVID-19 and may even help prevent infection.

So which is it? The answer may still be up in the air.

Doctors don’t fully understand what makes some viruses – like the ones that cause the flu – circulate in seasonal patterns.

There are, of course, many theories. These revolve around things like temperature and humidity – viruses tend to prefer colder, drier air – something that’s thought to help them spread more easily in the winter months. People are exposed to less sunlight during the winter, as they spend more time indoors, and the earth points away from the sun, providing some natural shielding. That may play a role because ultraviolet light from the sun acts like a natural disinfectant and may help keep circulating viral levels down.

In addition, exposure to sunlight helps the body make vitamin D, which may help keep our immune responses strong. Extreme temperatures – both cold and hot – also change our behavior, so that we spend more time cloistered indoors, where we can more easily cough and sneeze on each other and generally swap more germs.

Spike in pollen, jump in infections

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds a new variable to this mix – pollen. It relies on data from 248 airborne pollen–monitoring sites in 31 countries. The study also took into account other effects, such as population density, temperature, humidity, and lockdown orders. The study authors found that, when pollen in an area spiked, so did infections, after an average lag of about 4 days. The study authors say pollen seemed to account for, on average, 44% of the infection rate variability between countries.

The study authors say pollen could be a culprit in respiratory infections, not because the viruses hitch a ride on pollen grains and travel into our mouth, eyes, and nose, but because pollen seems to perturb our immune defenses, even if a person isn’t allergic to it.

“When we inhale pollen, they end up on our nasal mucosa, and here they diminish the expression of genes that are important for the defense against airborne viruses,” study author Stefanie Gilles, PhD, chair of environmental medicine at the Technical University of Munich, said in a press conference.

In a study published last year, Dr. Gilles found that mice exposed to pollen made less interferon and other protective chemical signals to the immune system. Those then infected with respiratory syncytial virus had more virus in their bodies, compared with mice not exposed to pollen. She seemed to see the same effect in human volunteers.

The study authors think pollen may cause the body to drop its defenses against the airborne virus that causes COVID-19, too.

“If you’re in a crowded room, and other people are there that are asymptomatic, and you’ve just been breathing in pollen all day long, chances are that you’re going to be more susceptible to the virus,” says Lewis Ziska, PhD, a plant physiologist who studies pollen, climate change, and health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York. “Having a mask is obviously really critical in that regard.”

Masks do a great job of blocking pollen, so wearing one is even more important when pollen and viruses are floating around, he says.

Other researchers, however, say that, while the study raises some interesting questions, it can’t prove that pollen is increasing COVID-19 infections.

“Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one causes the other,” says Martijn Hoogeveen, PhD, a professor of technical sciences and environment at the Open University in the Netherlands.

Dr. Hoogeveen’s recent study, published in Science of the Total Environment, found that the arrival of pollen season in the Netherlands coincides with the end of flu season, and that COVID-19 infection peaks tend to follow a similar pattern – exactly the opposite of the PNAS study.

Another preprint study, which focused on the Chicago area, found the same thing – as pollen climbs, flu cases drop. The researchers behind that study think pollen may actually compete with viruses in our airways, helping to block them from infecting our cells.

Patterns may be hard to nail down

Why did these studies reach such different conclusions?

Dr. Hoogeveen’s paper focused on a single country and looked at the incidence of flu infections over four seasons, from 2016 to 2020, while the PNAS study collected data on pollen from January through the first week of April 2020.

He thinks that a single season, or really part of a season, may not be long enough to see meaningful patterns, especially considering that this new-to-humans virus was spreading quickly at nearly the same time. He says it will be interesting to follow what happens with COVID-19 infections and pollen in the coming months and years.

Dr. Hoogeveen says that in a large study spanning so many countries it would have been nearly impossible to account for differences in pandemic control strategies. Some countries embraced the use of masks, stay-at-home orders, and social distancing, for example, while others took less stringent measures in order to let the virus run its course in pursuit of herd immunity.

Limiting the study area to a single country or city, he says, helps researchers better understand all the variables that might have been in play along with pollen.

“There is no scientific consensus yet, about what it is driving, and that’s what makes it such an interesting field,” he says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.