User login

Hereditary Hypotrichosis Simplex of the Scalp

To the Editor:

Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex (HHS)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 146520) is a rare form of hypotrichosis that typically presents in school-aged children as worsening hair loss localized to the scalp.1 Most patients are unaffected at birth and otherwise healthy without abnormalities of the nails, teeth, or perspiration. Examination of the scalp reveals normal follicular ostia and absence of scale and erythema; however, decreased follicular density may be noted.1 The histopathologic findings of HHS reveal velluslike hair follicles without associated fibrosis or inflammation.2 Examination of hair follicles with light microscopy is unremarkable.3,4 Historically, this condition has been largely regarded as autosomal dominant, with variable severity also described within families. Herein, we report a case of this rare disease in a child, with 2 family members displaying a less severe phenotype.

A 7-year-old girl presented with gradual thinning of the scalp hair of 3 to 4 years’ duration. Her mother reported the patient had normal hair density at birth. Over the next several years, she was noted to have an inability to grow lengthy hair. At approximately 3 years of age, thinning of scalp hair was identified. There was no prior history of increased shedding, hypohidrosis, or tooth or nail abnormalities. Family history revealed fine hair in her older sister and fine thin hair at the frontal scalp in her mother. Her mother reported similar inability to grow lengthy hair. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated short blonde hair with diffuse thinning of the crown (Figure 1). The longest hair was approximately 10 cm in length. Follicular ostia were without erythema or scale but notably fewer in number on the crown. Eyebrows, eyelashes, teeth, and fingernails were without abnormalities. A hair pull test was negative and hair mount revealed normal bulb and shaft. Microscopy of hair shafts under polarized light was unremarkable.

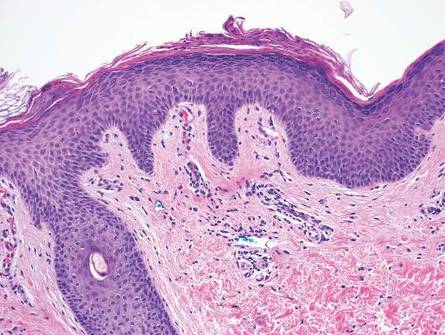

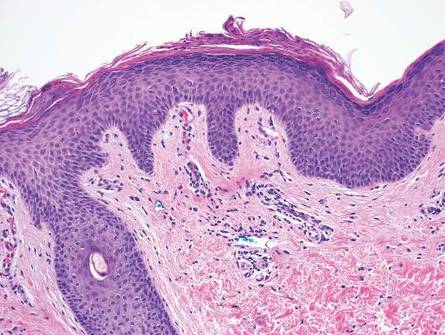

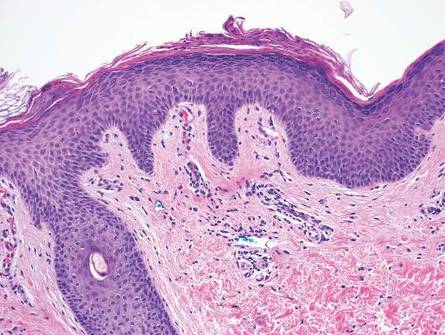

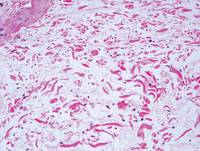

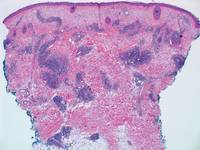

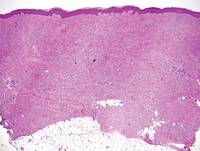

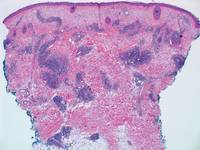

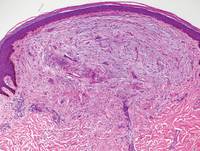

Two punch biopsies were obtained and submitted for vertical and horizontal sectioning. Sections demonstrated an intact epidermis, decreased follicle number, and small follicles with hypoplastic velluslike appearance (Figure 2). Fibrosis and inflammation were not seen; there was no increase in catagen or telogen hairs. Clinical and histopathological findings were consistent with HHS.

Hereditary hypotrichosis localized to the scalp was first described by Toribio and Quinones5 in 1974 in a large Spanish family presenting with normal scalp hair at birth followed by gradual diffuse hair loss. Hair loss that usually began in school-aged children with subsequent few fine hairs remaining on the scalp by the third decade of life was identified in these individuals.Eyelashes, eyebrows, pubic, axillary, and other truncal hairs were normal.5 Several similar cases of HHS localized to the scalp have since been reported.2,6 Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, with the exception of 1 reported sporadic case.3

Research on HHS has primarily focused on genetic analyses of several affected families. Betz et al7 mapped the gene for HHS to band 6p21.3 in 2 families of Danish origin and in the Spanish family initially described by Toribio and Quinones.5 Three years later, a nonsense mutation in the CDSN gene encoding corneodesmosin was described.8 Despite these genetic advances, the pathogenesis of HHS and the role that corneodesmosin may play remain unclear.

Generalized forms of hypotrichosis (OMIM #605389) have long been reported and described as loss of scalp hair with involvement of eyebrows, eyelashes, and other body hair.9 Genetic studies have allowed for genome-wide linkage analysis, linking 3 families with this more generalized HHS phenotype to chromosome 18; specifically, an Italian family with sparse scalp and body hair but normal eyelashes and eyebrows,4 and 2 Pakistani families with thinning scalp hair and sparse truncal hair.10 A mutation in the APC downregulated 1 gene, APCDD1, also has been identified in these families.10 These genetic findings indicate that the generalized form of HHS is a distinct syndrome.

The differential diagnosis of HHS includes Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis, loose anagen hair syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, and androgenetic alopecia. Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis usually presents as near-complete absence of scalp hair at birth, development of wiry twisted hair in childhood, and progressive alopecia.3 Loose anagen hair syndrome usually demonstrates a ruffled cuticle on hair pull test and remits in late childhood. Polarization of the hair shaft can identify patients with trichothiodystrophy. Follicular miniaturization may lead one to consider early-onset androgenetic alopecia in some patients.

There is no effective treatment of HHS. Due to potential phenotypic variation, patients should be counseled that they may experience progressive or possible total loss of scalp hair by the third decade of life.2,3,5 As with other hair loss disorders, wigs or additional over-the-counter cosmetic options may be considered.3 Currently, there are no known patient resources specific for HHS. Therefore, our patient’s family was referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation website (https://naaf.org/) for resources on discussing alopecia with school-aged children. The psychological impact of alopecia should not be overlooked and psychiatric referral should be provided, if needed. Examination of family members along with clinical monitoring are recommended. Genetic counseling also may be offered.3

- Rodríguez Díaz E, Fernández Blasco G, Martín Pascual A, et al. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Dermatology. 1995;191:139-141.

- Ibsen HH, Clemmensen OJ, Brandrup F. Familial hypotrichosis of the scalp. autosomal dominant inheritance in four generations. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:349-351.

- Cambiaghi S, Barbareschi M. A sporadic case of congenital hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp: difficulties in diagnosis and classification. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:301-304.

- Baumer A, Belli S, Trueb RM, et al. An autosomal dominant form of hereditary hypotrichosis simple maps to 18p11.32-p11.23 in an Italian family. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:443-448.

- Toribio J, Quinones PA. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:687-696.

- Kohn G, Metzker A. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Clin Genet. 1987;32:120-124.

- Betz RC, Lee YA, Bygum A, et al. A gene for hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp maps to chromosome 6p21.3. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1979-1983.

- Levy-Nissenbaum E, Betz R, Frydman M, et al. Hypotrichosis of the scalp is associated with nonsense mutations in CDSN encoding corneodesmosin. Nat Genet. 2003;34:151-153.

- Just M, Ribera M, Fuente MJ, et al. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Dermatology. 1998;196:339-342.

- Shimomura Y, Agalliu D, Vonica A, et al. APCDD1 is a novel Wnt inhibitor mutated in hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Nature. 2011;44:1043-1047.

To the Editor:

Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex (HHS)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 146520) is a rare form of hypotrichosis that typically presents in school-aged children as worsening hair loss localized to the scalp.1 Most patients are unaffected at birth and otherwise healthy without abnormalities of the nails, teeth, or perspiration. Examination of the scalp reveals normal follicular ostia and absence of scale and erythema; however, decreased follicular density may be noted.1 The histopathologic findings of HHS reveal velluslike hair follicles without associated fibrosis or inflammation.2 Examination of hair follicles with light microscopy is unremarkable.3,4 Historically, this condition has been largely regarded as autosomal dominant, with variable severity also described within families. Herein, we report a case of this rare disease in a child, with 2 family members displaying a less severe phenotype.

A 7-year-old girl presented with gradual thinning of the scalp hair of 3 to 4 years’ duration. Her mother reported the patient had normal hair density at birth. Over the next several years, she was noted to have an inability to grow lengthy hair. At approximately 3 years of age, thinning of scalp hair was identified. There was no prior history of increased shedding, hypohidrosis, or tooth or nail abnormalities. Family history revealed fine hair in her older sister and fine thin hair at the frontal scalp in her mother. Her mother reported similar inability to grow lengthy hair. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated short blonde hair with diffuse thinning of the crown (Figure 1). The longest hair was approximately 10 cm in length. Follicular ostia were without erythema or scale but notably fewer in number on the crown. Eyebrows, eyelashes, teeth, and fingernails were without abnormalities. A hair pull test was negative and hair mount revealed normal bulb and shaft. Microscopy of hair shafts under polarized light was unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were obtained and submitted for vertical and horizontal sectioning. Sections demonstrated an intact epidermis, decreased follicle number, and small follicles with hypoplastic velluslike appearance (Figure 2). Fibrosis and inflammation were not seen; there was no increase in catagen or telogen hairs. Clinical and histopathological findings were consistent with HHS.

Hereditary hypotrichosis localized to the scalp was first described by Toribio and Quinones5 in 1974 in a large Spanish family presenting with normal scalp hair at birth followed by gradual diffuse hair loss. Hair loss that usually began in school-aged children with subsequent few fine hairs remaining on the scalp by the third decade of life was identified in these individuals.Eyelashes, eyebrows, pubic, axillary, and other truncal hairs were normal.5 Several similar cases of HHS localized to the scalp have since been reported.2,6 Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, with the exception of 1 reported sporadic case.3

Research on HHS has primarily focused on genetic analyses of several affected families. Betz et al7 mapped the gene for HHS to band 6p21.3 in 2 families of Danish origin and in the Spanish family initially described by Toribio and Quinones.5 Three years later, a nonsense mutation in the CDSN gene encoding corneodesmosin was described.8 Despite these genetic advances, the pathogenesis of HHS and the role that corneodesmosin may play remain unclear.

Generalized forms of hypotrichosis (OMIM #605389) have long been reported and described as loss of scalp hair with involvement of eyebrows, eyelashes, and other body hair.9 Genetic studies have allowed for genome-wide linkage analysis, linking 3 families with this more generalized HHS phenotype to chromosome 18; specifically, an Italian family with sparse scalp and body hair but normal eyelashes and eyebrows,4 and 2 Pakistani families with thinning scalp hair and sparse truncal hair.10 A mutation in the APC downregulated 1 gene, APCDD1, also has been identified in these families.10 These genetic findings indicate that the generalized form of HHS is a distinct syndrome.

The differential diagnosis of HHS includes Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis, loose anagen hair syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, and androgenetic alopecia. Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis usually presents as near-complete absence of scalp hair at birth, development of wiry twisted hair in childhood, and progressive alopecia.3 Loose anagen hair syndrome usually demonstrates a ruffled cuticle on hair pull test and remits in late childhood. Polarization of the hair shaft can identify patients with trichothiodystrophy. Follicular miniaturization may lead one to consider early-onset androgenetic alopecia in some patients.

There is no effective treatment of HHS. Due to potential phenotypic variation, patients should be counseled that they may experience progressive or possible total loss of scalp hair by the third decade of life.2,3,5 As with other hair loss disorders, wigs or additional over-the-counter cosmetic options may be considered.3 Currently, there are no known patient resources specific for HHS. Therefore, our patient’s family was referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation website (https://naaf.org/) for resources on discussing alopecia with school-aged children. The psychological impact of alopecia should not be overlooked and psychiatric referral should be provided, if needed. Examination of family members along with clinical monitoring are recommended. Genetic counseling also may be offered.3

To the Editor:

Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex (HHS)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 146520) is a rare form of hypotrichosis that typically presents in school-aged children as worsening hair loss localized to the scalp.1 Most patients are unaffected at birth and otherwise healthy without abnormalities of the nails, teeth, or perspiration. Examination of the scalp reveals normal follicular ostia and absence of scale and erythema; however, decreased follicular density may be noted.1 The histopathologic findings of HHS reveal velluslike hair follicles without associated fibrosis or inflammation.2 Examination of hair follicles with light microscopy is unremarkable.3,4 Historically, this condition has been largely regarded as autosomal dominant, with variable severity also described within families. Herein, we report a case of this rare disease in a child, with 2 family members displaying a less severe phenotype.

A 7-year-old girl presented with gradual thinning of the scalp hair of 3 to 4 years’ duration. Her mother reported the patient had normal hair density at birth. Over the next several years, she was noted to have an inability to grow lengthy hair. At approximately 3 years of age, thinning of scalp hair was identified. There was no prior history of increased shedding, hypohidrosis, or tooth or nail abnormalities. Family history revealed fine hair in her older sister and fine thin hair at the frontal scalp in her mother. Her mother reported similar inability to grow lengthy hair. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated short blonde hair with diffuse thinning of the crown (Figure 1). The longest hair was approximately 10 cm in length. Follicular ostia were without erythema or scale but notably fewer in number on the crown. Eyebrows, eyelashes, teeth, and fingernails were without abnormalities. A hair pull test was negative and hair mount revealed normal bulb and shaft. Microscopy of hair shafts under polarized light was unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were obtained and submitted for vertical and horizontal sectioning. Sections demonstrated an intact epidermis, decreased follicle number, and small follicles with hypoplastic velluslike appearance (Figure 2). Fibrosis and inflammation were not seen; there was no increase in catagen or telogen hairs. Clinical and histopathological findings were consistent with HHS.

Hereditary hypotrichosis localized to the scalp was first described by Toribio and Quinones5 in 1974 in a large Spanish family presenting with normal scalp hair at birth followed by gradual diffuse hair loss. Hair loss that usually began in school-aged children with subsequent few fine hairs remaining on the scalp by the third decade of life was identified in these individuals.Eyelashes, eyebrows, pubic, axillary, and other truncal hairs were normal.5 Several similar cases of HHS localized to the scalp have since been reported.2,6 Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, with the exception of 1 reported sporadic case.3

Research on HHS has primarily focused on genetic analyses of several affected families. Betz et al7 mapped the gene for HHS to band 6p21.3 in 2 families of Danish origin and in the Spanish family initially described by Toribio and Quinones.5 Three years later, a nonsense mutation in the CDSN gene encoding corneodesmosin was described.8 Despite these genetic advances, the pathogenesis of HHS and the role that corneodesmosin may play remain unclear.

Generalized forms of hypotrichosis (OMIM #605389) have long been reported and described as loss of scalp hair with involvement of eyebrows, eyelashes, and other body hair.9 Genetic studies have allowed for genome-wide linkage analysis, linking 3 families with this more generalized HHS phenotype to chromosome 18; specifically, an Italian family with sparse scalp and body hair but normal eyelashes and eyebrows,4 and 2 Pakistani families with thinning scalp hair and sparse truncal hair.10 A mutation in the APC downregulated 1 gene, APCDD1, also has been identified in these families.10 These genetic findings indicate that the generalized form of HHS is a distinct syndrome.

The differential diagnosis of HHS includes Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis, loose anagen hair syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, and androgenetic alopecia. Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis usually presents as near-complete absence of scalp hair at birth, development of wiry twisted hair in childhood, and progressive alopecia.3 Loose anagen hair syndrome usually demonstrates a ruffled cuticle on hair pull test and remits in late childhood. Polarization of the hair shaft can identify patients with trichothiodystrophy. Follicular miniaturization may lead one to consider early-onset androgenetic alopecia in some patients.

There is no effective treatment of HHS. Due to potential phenotypic variation, patients should be counseled that they may experience progressive or possible total loss of scalp hair by the third decade of life.2,3,5 As with other hair loss disorders, wigs or additional over-the-counter cosmetic options may be considered.3 Currently, there are no known patient resources specific for HHS. Therefore, our patient’s family was referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation website (https://naaf.org/) for resources on discussing alopecia with school-aged children. The psychological impact of alopecia should not be overlooked and psychiatric referral should be provided, if needed. Examination of family members along with clinical monitoring are recommended. Genetic counseling also may be offered.3

- Rodríguez Díaz E, Fernández Blasco G, Martín Pascual A, et al. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Dermatology. 1995;191:139-141.

- Ibsen HH, Clemmensen OJ, Brandrup F. Familial hypotrichosis of the scalp. autosomal dominant inheritance in four generations. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:349-351.

- Cambiaghi S, Barbareschi M. A sporadic case of congenital hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp: difficulties in diagnosis and classification. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:301-304.

- Baumer A, Belli S, Trueb RM, et al. An autosomal dominant form of hereditary hypotrichosis simple maps to 18p11.32-p11.23 in an Italian family. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:443-448.

- Toribio J, Quinones PA. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:687-696.

- Kohn G, Metzker A. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Clin Genet. 1987;32:120-124.

- Betz RC, Lee YA, Bygum A, et al. A gene for hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp maps to chromosome 6p21.3. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1979-1983.

- Levy-Nissenbaum E, Betz R, Frydman M, et al. Hypotrichosis of the scalp is associated with nonsense mutations in CDSN encoding corneodesmosin. Nat Genet. 2003;34:151-153.

- Just M, Ribera M, Fuente MJ, et al. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Dermatology. 1998;196:339-342.

- Shimomura Y, Agalliu D, Vonica A, et al. APCDD1 is a novel Wnt inhibitor mutated in hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Nature. 2011;44:1043-1047.

- Rodríguez Díaz E, Fernández Blasco G, Martín Pascual A, et al. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Dermatology. 1995;191:139-141.

- Ibsen HH, Clemmensen OJ, Brandrup F. Familial hypotrichosis of the scalp. autosomal dominant inheritance in four generations. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:349-351.

- Cambiaghi S, Barbareschi M. A sporadic case of congenital hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp: difficulties in diagnosis and classification. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:301-304.

- Baumer A, Belli S, Trueb RM, et al. An autosomal dominant form of hereditary hypotrichosis simple maps to 18p11.32-p11.23 in an Italian family. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:443-448.

- Toribio J, Quinones PA. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:687-696.

- Kohn G, Metzker A. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Clin Genet. 1987;32:120-124.

- Betz RC, Lee YA, Bygum A, et al. A gene for hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp maps to chromosome 6p21.3. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1979-1983.

- Levy-Nissenbaum E, Betz R, Frydman M, et al. Hypotrichosis of the scalp is associated with nonsense mutations in CDSN encoding corneodesmosin. Nat Genet. 2003;34:151-153.

- Just M, Ribera M, Fuente MJ, et al. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Dermatology. 1998;196:339-342.

- Shimomura Y, Agalliu D, Vonica A, et al. APCDD1 is a novel Wnt inhibitor mutated in hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Nature. 2011;44:1043-1047.

Practice Points

- Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex (HHS) is a rare form of hypotrichosis that typically presents in school-aged children as worsening hair loss localized to the scalp.

- Historically, HHS has been largely regarded as autosomal dominant, with variable severity also described within families.

- There is no effective treatment of HHS. Due to potential phenotypic variation, patients should be counseled that they may experience progressive or possible total loss of scalp hair by the third decade of life.

Perifollicular Papules on the Trunk

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

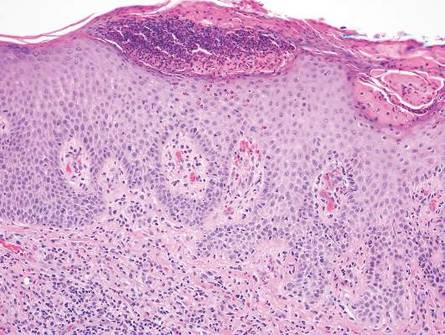

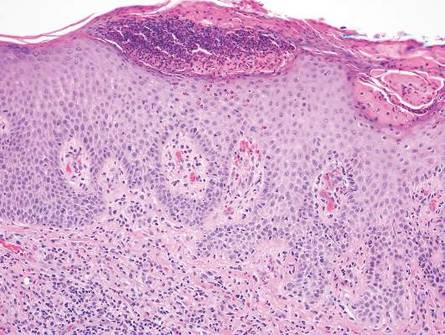

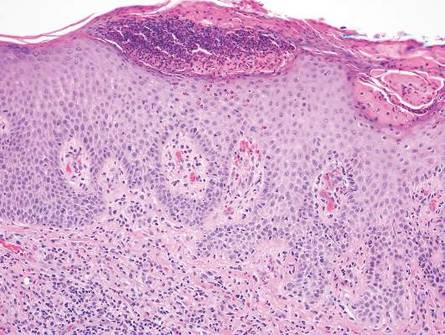

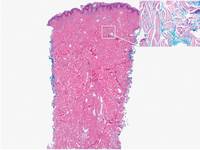

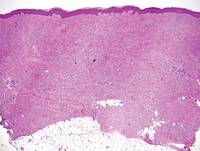

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

A 40-year-old black man presented with numerous perifollicular flesh-colored papules on the back, chest, abdomen, and proximal aspect of the arms of 6 years' duration. He described these lesions as persistent, nonpainful, and nonpruritic. He previously was treated with an unknown cream without any benefit. These lesions were cosmetically bothersome.

Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

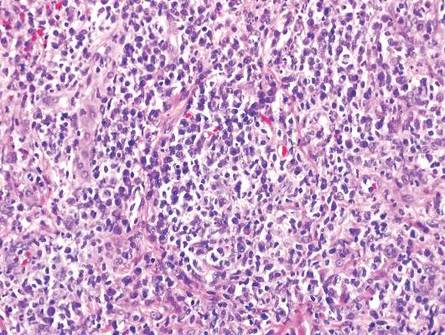

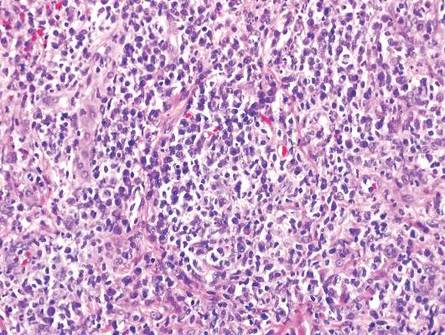

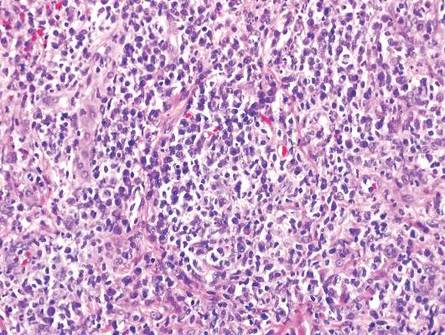

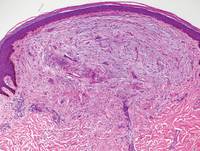

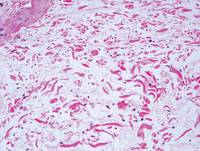

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

Large Subcutaneous Masses

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules on the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. His medical history was remarkable for alcoholism, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

Pretibial Myxedema

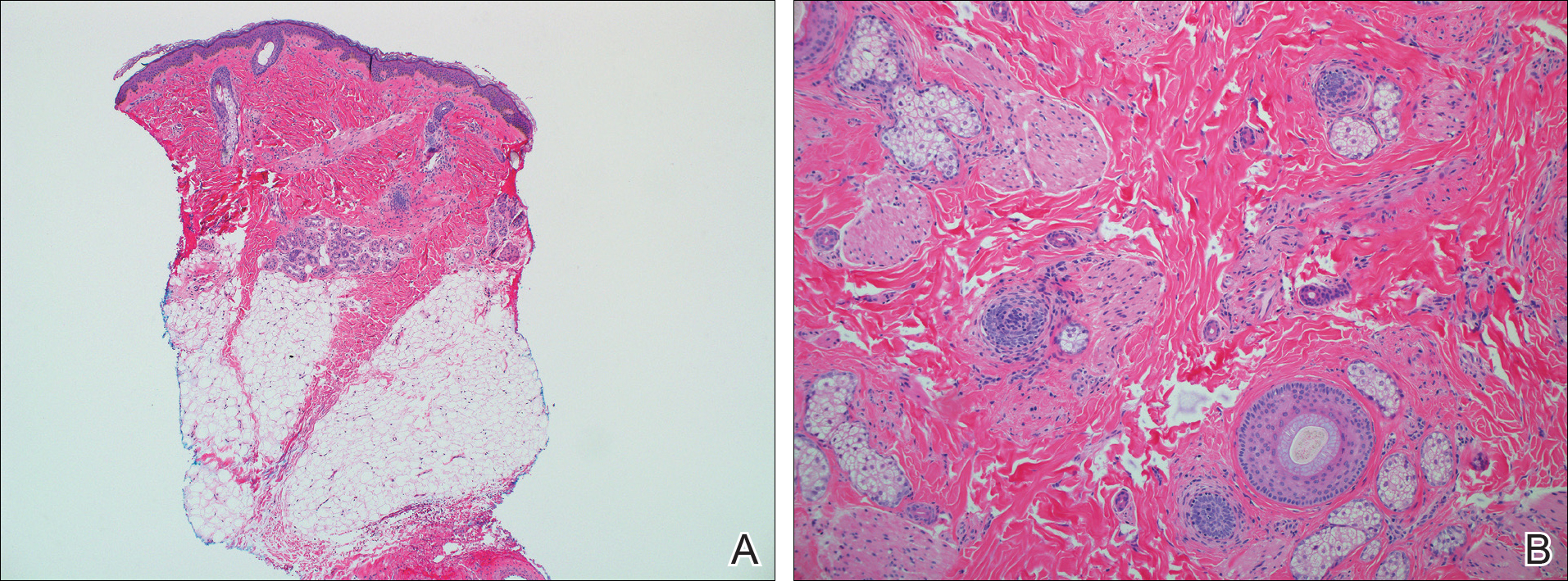

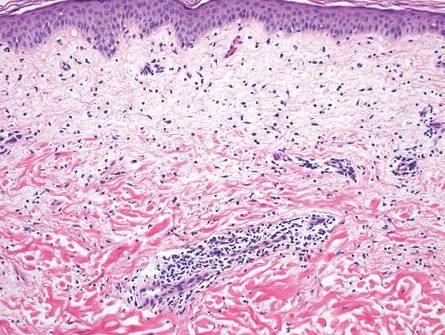

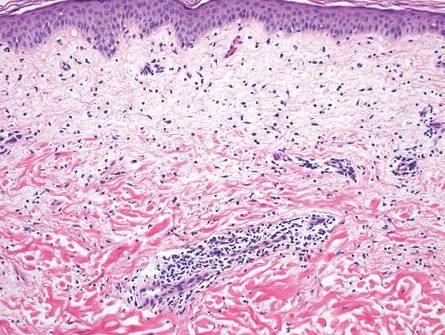

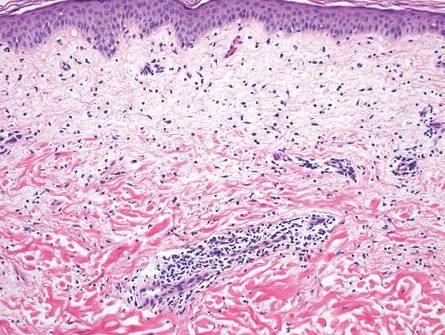

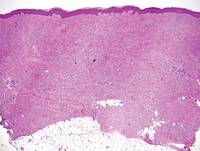

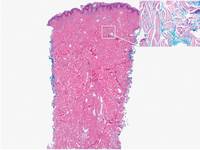

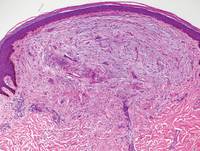

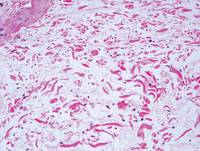

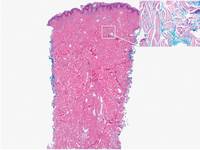

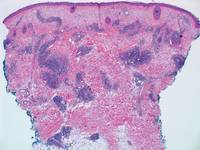

Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. It most commonly presents in the setting of Graves disease and is seen less often in patients with hypothyroidism and euthyroidism.1 The anterior tibia is most frequently affected, but lesions also may present on the feet, thighs, and upper extremities. Physical examination generally demonstrates skin thickening, hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, yellow-red discoloration, and hyperhidrosis. Classically, the term peau d’orange has been used to characterize these clinical features.1 Histologic examination of PM typically reveals marked deposition of mucin throughout the reticular dermis with sparing of the papillary dermis (Figure 1) and may be accompanied by overlying hyperkeratosis. Collagen fibers are splayed and appear decreased in density (Figure 2). Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, colloidal iron, and toluidine blue staining can be used to highlight dermal mucin.

|  |

Figure 1. Prominent mucin deposition throughout the reticular dermis in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 2. Increased mucin deposition and collagen fiber splaying in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|  |

Figure 3. Scleredema with increased dermal thickness (H&E, original magnification ×20) and interstitial mucin on colloidal iron–stained sections (inset in upper right corner, original magnification ×400). | Figure 4. Scleromyxedema with mucin deposition primarily in the superficial dermis as well as increased cellularity and fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|  |

Figure 5. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with prominent mucinous fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 6. Tumid lupus erythematosus with a superficial and perivascular lymphoid infiltrate as well as increased dermal mucin (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Similar to PM, histologic examination of scleredema and scleromyxedema usually demonstrate prominent mucin deposition. In scleredema, mucin primarily is visualized in the deep dermis between thick collagen bundles and typically is localized to the back (Figure 3). Scleromyxedema is distinguished by mucin deposition in the superficial dermis with associated fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is characterized by proliferation of CD34+ dermal spindle cells, fibroblasts, interstitial mucin, altered elastic fibers, and thickened collagen bundles that involve the dermis and subcutaneous septa (Figure 5).2 Tumid lupus erythematosus classically demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal superficial and deep lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 6). Similar to scleredema and PM, mucin deposition in tumid lupus erythematosus is interspersed between collagen bundles in the reticular dermis.3

1. Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

2. Cowper SE, Lyndon DS, Bhawan J, et al. Nephro-genic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol.2001;23:383-393.

3. Kuhn A, Dagmar RH, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. It most commonly presents in the setting of Graves disease and is seen less often in patients with hypothyroidism and euthyroidism.1 The anterior tibia is most frequently affected, but lesions also may present on the feet, thighs, and upper extremities. Physical examination generally demonstrates skin thickening, hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, yellow-red discoloration, and hyperhidrosis. Classically, the term peau d’orange has been used to characterize these clinical features.1 Histologic examination of PM typically reveals marked deposition of mucin throughout the reticular dermis with sparing of the papillary dermis (Figure 1) and may be accompanied by overlying hyperkeratosis. Collagen fibers are splayed and appear decreased in density (Figure 2). Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, colloidal iron, and toluidine blue staining can be used to highlight dermal mucin.

|  |

Figure 1. Prominent mucin deposition throughout the reticular dermis in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 2. Increased mucin deposition and collagen fiber splaying in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|  |

Figure 3. Scleredema with increased dermal thickness (H&E, original magnification ×20) and interstitial mucin on colloidal iron–stained sections (inset in upper right corner, original magnification ×400). | Figure 4. Scleromyxedema with mucin deposition primarily in the superficial dermis as well as increased cellularity and fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|  |

Figure 5. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with prominent mucinous fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 6. Tumid lupus erythematosus with a superficial and perivascular lymphoid infiltrate as well as increased dermal mucin (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Similar to PM, histologic examination of scleredema and scleromyxedema usually demonstrate prominent mucin deposition. In scleredema, mucin primarily is visualized in the deep dermis between thick collagen bundles and typically is localized to the back (Figure 3). Scleromyxedema is distinguished by mucin deposition in the superficial dermis with associated fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is characterized by proliferation of CD34+ dermal spindle cells, fibroblasts, interstitial mucin, altered elastic fibers, and thickened collagen bundles that involve the dermis and subcutaneous septa (Figure 5).2 Tumid lupus erythematosus classically demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal superficial and deep lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 6). Similar to scleredema and PM, mucin deposition in tumid lupus erythematosus is interspersed between collagen bundles in the reticular dermis.3

Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. It most commonly presents in the setting of Graves disease and is seen less often in patients with hypothyroidism and euthyroidism.1 The anterior tibia is most frequently affected, but lesions also may present on the feet, thighs, and upper extremities. Physical examination generally demonstrates skin thickening, hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, yellow-red discoloration, and hyperhidrosis. Classically, the term peau d’orange has been used to characterize these clinical features.1 Histologic examination of PM typically reveals marked deposition of mucin throughout the reticular dermis with sparing of the papillary dermis (Figure 1) and may be accompanied by overlying hyperkeratosis. Collagen fibers are splayed and appear decreased in density (Figure 2). Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, colloidal iron, and toluidine blue staining can be used to highlight dermal mucin.

|  |

Figure 1. Prominent mucin deposition throughout the reticular dermis in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 2. Increased mucin deposition and collagen fiber splaying in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|  |

Figure 3. Scleredema with increased dermal thickness (H&E, original magnification ×20) and interstitial mucin on colloidal iron–stained sections (inset in upper right corner, original magnification ×400). | Figure 4. Scleromyxedema with mucin deposition primarily in the superficial dermis as well as increased cellularity and fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|  |

Figure 5. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with prominent mucinous fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 6. Tumid lupus erythematosus with a superficial and perivascular lymphoid infiltrate as well as increased dermal mucin (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Similar to PM, histologic examination of scleredema and scleromyxedema usually demonstrate prominent mucin deposition. In scleredema, mucin primarily is visualized in the deep dermis between thick collagen bundles and typically is localized to the back (Figure 3). Scleromyxedema is distinguished by mucin deposition in the superficial dermis with associated fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is characterized by proliferation of CD34+ dermal spindle cells, fibroblasts, interstitial mucin, altered elastic fibers, and thickened collagen bundles that involve the dermis and subcutaneous septa (Figure 5).2 Tumid lupus erythematosus classically demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal superficial and deep lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 6). Similar to scleredema and PM, mucin deposition in tumid lupus erythematosus is interspersed between collagen bundles in the reticular dermis.3

1. Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

2. Cowper SE, Lyndon DS, Bhawan J, et al. Nephro-genic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol.2001;23:383-393.

3. Kuhn A, Dagmar RH, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

1. Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

2. Cowper SE, Lyndon DS, Bhawan J, et al. Nephro-genic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol.2001;23:383-393.

3. Kuhn A, Dagmar RH, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.