User login

Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis Presenting as an Extensive Eroded Plaque

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

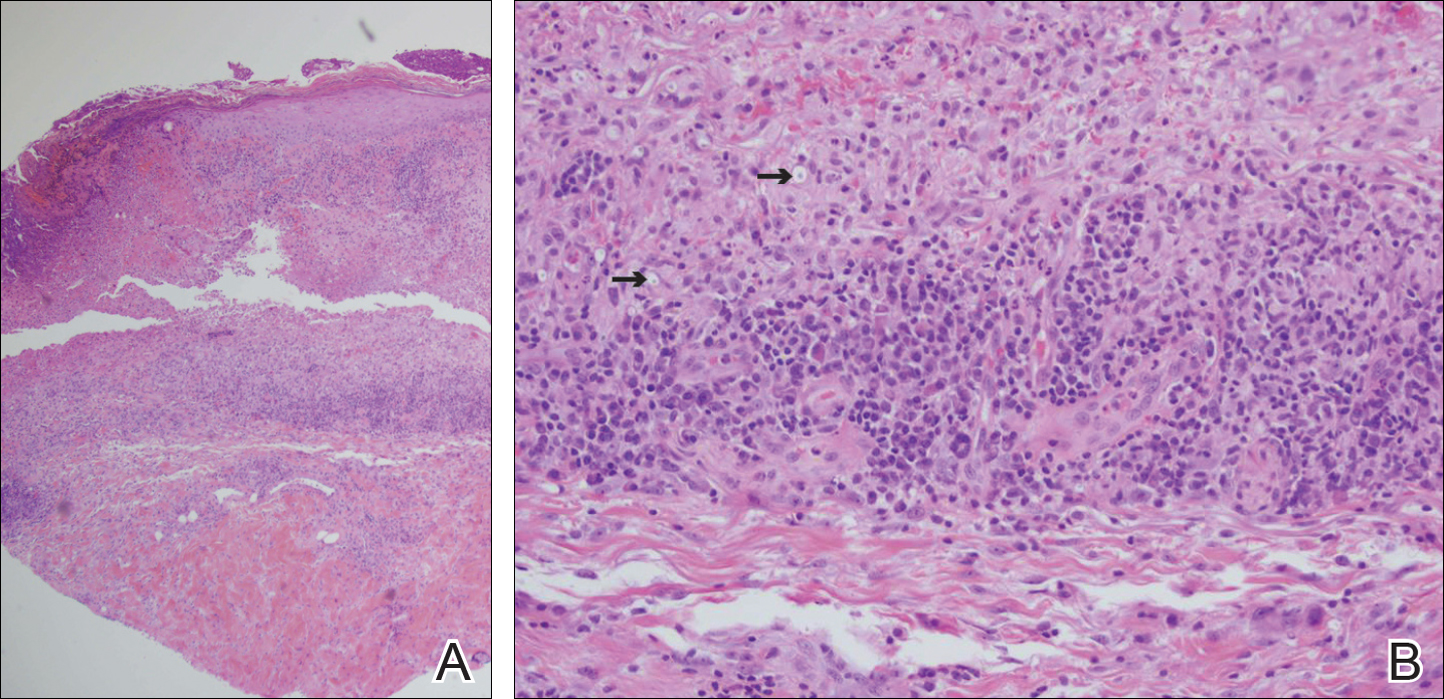

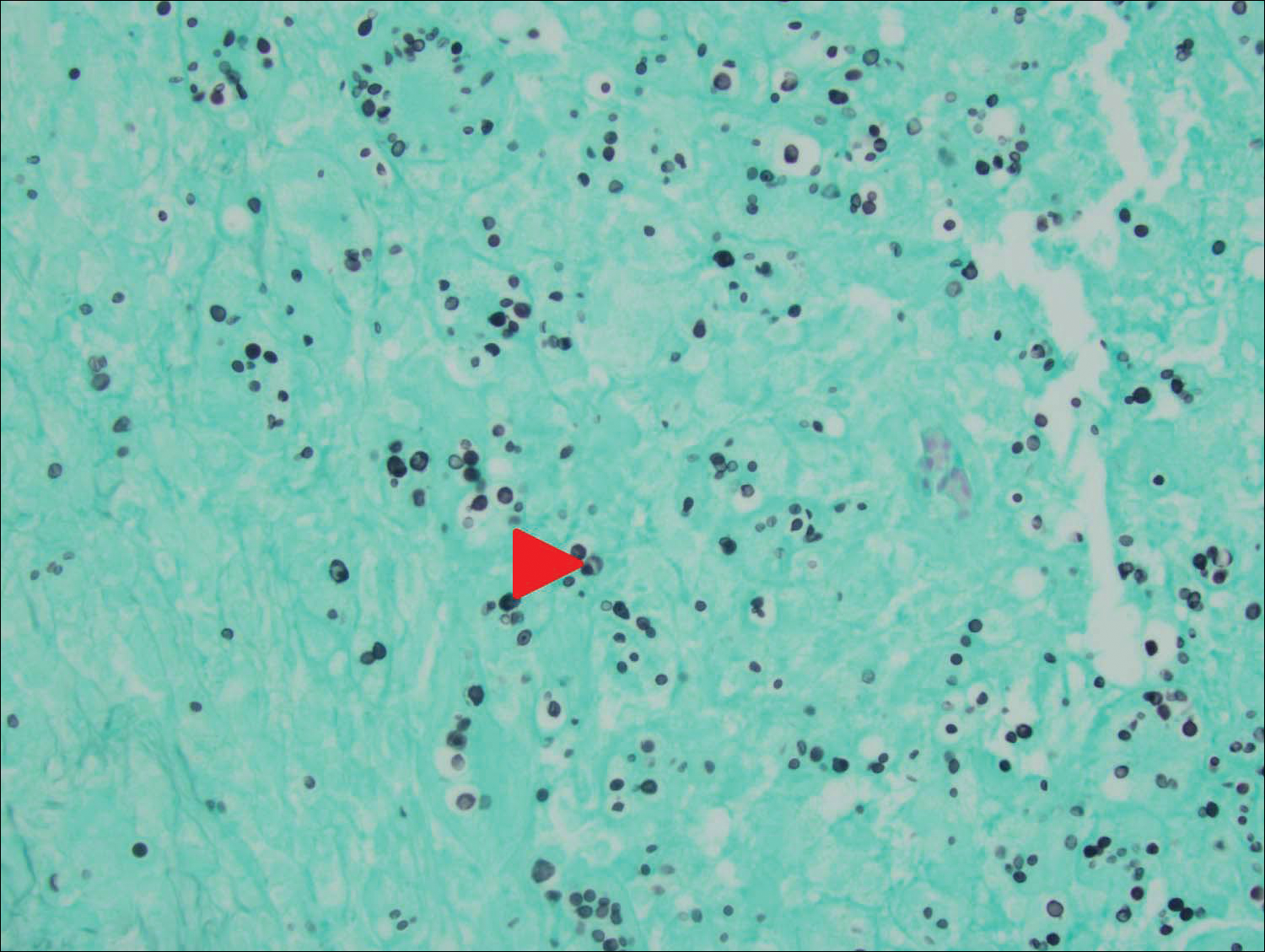

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

Practice Points

- Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is rare in nonimmunosuppressed patients.

- Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis secondary to inoculation can have a clinical presentation similar to more common conditions, such as molluscum, acne, and dermatitis.

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema With Recalcitrant Dermatitis as the Only Presenting Symptom

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man presented with recalcitrant dermatitis of 6 years’ duration. He was otherwise in excellent health. On initial presentation, physical examination revealed symmetrical, erythematous, blanching plaques with areas of erosions and overlying hemorrhagic crust on the eyebrows, scalp, back, dorsal aspects of the hands, axillae, abdomen (Figure), buttocks, groin, scrotum, pubis, and lower legs. Some areas showed slight necrosis. He denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, lightheadedness, weight loss, or appetite change.

Throughout the disease course the patient had visited numerous dermatologists seeking treatment. He had response to higher doses of oral prednisone (80 mg taper), but the condition would recur at the end of an extended taper. Treatment with narrowband UVB, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, acitretin, topical clobetasol, and topical pimecrolimus provided no relief. Eventually he was placed on azathioprine 100 mg twice daily, which led to near-complete resolution. Outbreaks continued every few months and required courses of prednisone.

Multiple biopsies over the years revealed subacute spongiotic or psoriasiform dermatitis. At multiple visits it was noted that during flares there were areas of crusting and mild necrosis, which led to an extensive biochemical investigation. The glucagon level was markedly elevated at 630 ng/L (reference range, 40–130 ng/L), as was insulin at 71 μIU/mL (reference range, 6–27 μIU/mL). Complete blood cell counts over the disease course showed mild normochromic normocytic anemia. The abnormal laboratory findings led to computed tomography of the abdomen, which revealed a mass in the body of the pancreas measuring 3×3.8 cm. After computed tomography, the patient underwent a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. Histologic examination revealed a well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine tumor (glucagonoma) confined to the pancreas. After the surgery, the patient’s rash resolved within a few days and he discontinued all medications.

Diagnosis of glucagonomas often is delayed due to their rarity and lack of classical signs and symptoms. The distribution of the lesions seen in necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) usually involves the inguinal crease, perineum, lower extremities, buttocks, and other intertriginous areas.1 Our patient had involvement in the typical distribution but also had involvement of the scalp, face, and upper body. The typical histology for NME is crusted psoriasiform dermatitis with a tendency for the upper epidermis to have necrosis and a vacuolated pale epidermis.2 Our patient’s histologic findings were less specific showing epidermal spongiosis with a scant lymphocytic infiltrate and at times acanthosis. The lack of classical skin findings and histology delayed diagnosis. In more than 50% of patients, metastasis has already occurred by the time the patient is diagnosed.3 Treatment is aimed at complete removal of the pancreatic tumor, which typically leads to a rapid improvement in symptoms. For patients unable to undergo surgery, chemotherapy agents and octreotide are used; unfortunately, symptoms may persist.4 The response to azathioprine in our patient suggests it is a possible alternate therapy for those with persistent NME.

This patient highlights the difficulty of diagnosing a glucagonoma when the only clinical manifestation may be NME. Moreover, skin biopsies that can sometimes be diagnostic may be nonspecific. This patient also shows a potential benefit of azathioprine in the treatment of NME.

- Shi W, Liao W, Mei X, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema associated with glucagonoma syndrome [published online June 7, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e329-e331.

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. London, England: Elsevier Mosby; 2005.

- Oberg K, Eriksson B. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:753-781.

- Wermers RA, Fatourechi V, Wynne AG, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome: clinical and pathologic features in 21 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;72:53-63.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man presented with recalcitrant dermatitis of 6 years’ duration. He was otherwise in excellent health. On initial presentation, physical examination revealed symmetrical, erythematous, blanching plaques with areas of erosions and overlying hemorrhagic crust on the eyebrows, scalp, back, dorsal aspects of the hands, axillae, abdomen (Figure), buttocks, groin, scrotum, pubis, and lower legs. Some areas showed slight necrosis. He denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, lightheadedness, weight loss, or appetite change.

Throughout the disease course the patient had visited numerous dermatologists seeking treatment. He had response to higher doses of oral prednisone (80 mg taper), but the condition would recur at the end of an extended taper. Treatment with narrowband UVB, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, acitretin, topical clobetasol, and topical pimecrolimus provided no relief. Eventually he was placed on azathioprine 100 mg twice daily, which led to near-complete resolution. Outbreaks continued every few months and required courses of prednisone.

Multiple biopsies over the years revealed subacute spongiotic or psoriasiform dermatitis. At multiple visits it was noted that during flares there were areas of crusting and mild necrosis, which led to an extensive biochemical investigation. The glucagon level was markedly elevated at 630 ng/L (reference range, 40–130 ng/L), as was insulin at 71 μIU/mL (reference range, 6–27 μIU/mL). Complete blood cell counts over the disease course showed mild normochromic normocytic anemia. The abnormal laboratory findings led to computed tomography of the abdomen, which revealed a mass in the body of the pancreas measuring 3×3.8 cm. After computed tomography, the patient underwent a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. Histologic examination revealed a well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine tumor (glucagonoma) confined to the pancreas. After the surgery, the patient’s rash resolved within a few days and he discontinued all medications.

Diagnosis of glucagonomas often is delayed due to their rarity and lack of classical signs and symptoms. The distribution of the lesions seen in necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) usually involves the inguinal crease, perineum, lower extremities, buttocks, and other intertriginous areas.1 Our patient had involvement in the typical distribution but also had involvement of the scalp, face, and upper body. The typical histology for NME is crusted psoriasiform dermatitis with a tendency for the upper epidermis to have necrosis and a vacuolated pale epidermis.2 Our patient’s histologic findings were less specific showing epidermal spongiosis with a scant lymphocytic infiltrate and at times acanthosis. The lack of classical skin findings and histology delayed diagnosis. In more than 50% of patients, metastasis has already occurred by the time the patient is diagnosed.3 Treatment is aimed at complete removal of the pancreatic tumor, which typically leads to a rapid improvement in symptoms. For patients unable to undergo surgery, chemotherapy agents and octreotide are used; unfortunately, symptoms may persist.4 The response to azathioprine in our patient suggests it is a possible alternate therapy for those with persistent NME.

This patient highlights the difficulty of diagnosing a glucagonoma when the only clinical manifestation may be NME. Moreover, skin biopsies that can sometimes be diagnostic may be nonspecific. This patient also shows a potential benefit of azathioprine in the treatment of NME.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man presented with recalcitrant dermatitis of 6 years’ duration. He was otherwise in excellent health. On initial presentation, physical examination revealed symmetrical, erythematous, blanching plaques with areas of erosions and overlying hemorrhagic crust on the eyebrows, scalp, back, dorsal aspects of the hands, axillae, abdomen (Figure), buttocks, groin, scrotum, pubis, and lower legs. Some areas showed slight necrosis. He denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, lightheadedness, weight loss, or appetite change.

Throughout the disease course the patient had visited numerous dermatologists seeking treatment. He had response to higher doses of oral prednisone (80 mg taper), but the condition would recur at the end of an extended taper. Treatment with narrowband UVB, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, acitretin, topical clobetasol, and topical pimecrolimus provided no relief. Eventually he was placed on azathioprine 100 mg twice daily, which led to near-complete resolution. Outbreaks continued every few months and required courses of prednisone.

Multiple biopsies over the years revealed subacute spongiotic or psoriasiform dermatitis. At multiple visits it was noted that during flares there were areas of crusting and mild necrosis, which led to an extensive biochemical investigation. The glucagon level was markedly elevated at 630 ng/L (reference range, 40–130 ng/L), as was insulin at 71 μIU/mL (reference range, 6–27 μIU/mL). Complete blood cell counts over the disease course showed mild normochromic normocytic anemia. The abnormal laboratory findings led to computed tomography of the abdomen, which revealed a mass in the body of the pancreas measuring 3×3.8 cm. After computed tomography, the patient underwent a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. Histologic examination revealed a well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine tumor (glucagonoma) confined to the pancreas. After the surgery, the patient’s rash resolved within a few days and he discontinued all medications.

Diagnosis of glucagonomas often is delayed due to their rarity and lack of classical signs and symptoms. The distribution of the lesions seen in necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) usually involves the inguinal crease, perineum, lower extremities, buttocks, and other intertriginous areas.1 Our patient had involvement in the typical distribution but also had involvement of the scalp, face, and upper body. The typical histology for NME is crusted psoriasiform dermatitis with a tendency for the upper epidermis to have necrosis and a vacuolated pale epidermis.2 Our patient’s histologic findings were less specific showing epidermal spongiosis with a scant lymphocytic infiltrate and at times acanthosis. The lack of classical skin findings and histology delayed diagnosis. In more than 50% of patients, metastasis has already occurred by the time the patient is diagnosed.3 Treatment is aimed at complete removal of the pancreatic tumor, which typically leads to a rapid improvement in symptoms. For patients unable to undergo surgery, chemotherapy agents and octreotide are used; unfortunately, symptoms may persist.4 The response to azathioprine in our patient suggests it is a possible alternate therapy for those with persistent NME.

This patient highlights the difficulty of diagnosing a glucagonoma when the only clinical manifestation may be NME. Moreover, skin biopsies that can sometimes be diagnostic may be nonspecific. This patient also shows a potential benefit of azathioprine in the treatment of NME.

- Shi W, Liao W, Mei X, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema associated with glucagonoma syndrome [published online June 7, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e329-e331.

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. London, England: Elsevier Mosby; 2005.

- Oberg K, Eriksson B. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:753-781.

- Wermers RA, Fatourechi V, Wynne AG, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome: clinical and pathologic features in 21 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;72:53-63.

- Shi W, Liao W, Mei X, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema associated with glucagonoma syndrome [published online June 7, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e329-e331.

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. London, England: Elsevier Mosby; 2005.

- Oberg K, Eriksson B. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:753-781.

- Wermers RA, Fatourechi V, Wynne AG, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome: clinical and pathologic features in 21 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;72:53-63.

Practice Points

- Recalcitrant dermatitis may be a symptom of internal malignancy.

- Glucagon levels are helpful in identifying glucagonomas of the pancreas.

- Although surgical excision is the preferred treatment of glucagonomas, azathioprine also can control dermatitis associated with necrolytic migratory erythema.

The Spectrum of Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis and Mycosis Fungoides: Atypical T-Cell Dyscrasia

Case Report

A healthy 17-year-old adolescent boy with an unremarkable medical history presented with an asymptomatic fixed rash on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs. The rash initially developed in a small area on the right leg 2 years prior and had slowly progressed. He was not currently taking any medications and did not participate in intense physical activity. Multiple biopsies had previously been performed by an outside physician, the most recent one demonstrating an interface and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with pigmented purpura. He did not respond to treatment with intralesional corticosteroids, high-potency topical steroids, or high-dose oral prednisone.

Clinical examination revealed multiple annular purpuric patches on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs that covered approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Over several follow-up visits, a few of the lesions evolved from patches to thin plaques. There was no adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Three additional biopsies taken over the next 4 months demonstrated a mixture of small mature lymphocytes with some atypical lymphocytes in the dermis and epidermis exhibiting diminished CD7 staining and lymphocytes lining up at the dermoepidermal junction. T-cell receptor g gene rearrangements demonstrated the same clonal population in all 3 specimens. The patient was diagnosed with stage IB mycosis fungoides (MF) of the pigmented purpura–like variant. Marked improvement of the lesions was noted after 6 weeks of psoralen plus UVA therapy 3 times weekly (Figure 2). Treatment was continued for 6 months but was discontinued due to the international shortage of methoxsalen. Two months after discontinuation, most of the lesions had completely resolved (Figure 3).

|

Comment

Mycoses fungoides is a rare cutaneous lymphoma that affects approximately 2000 patients in the United States.1 Only 5% of all cases are known to occur in the first 2 decades of life,2 and even fewer cases pre-sent with pigmented purpura, usually of the lichenoid variant.3 Although the patches and plaques of MF can masquerade as many other dermatoses (eg, dermatophytosis, psoriasis, dermatitis), there have been few reports of patients presenting with lesions with the clinical appearance of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD).4 As with the many cases of early MF, which are histologically indistinguishable from dermatitis, the pigmented purpura–like variant of MF initially may have the histologic appearance of pigmented purpura and generally evolves to the histologic appearance of MF over time.

Similar to our case, there have been reports of clinical and histologic diagnosis of PPD preceding the histologic diagnosis of MF. In a small cohort study of 3 young men, Barnhill and Braverman5 first demonstrated the progression of PPD to MF over a 12-year period. The age of onset ranged from 14 to 30 years, with a mean age of 24.3 years. Biopsies in all 3 patients were consistent with PPD for many years prior to the diagnosis of MF, with an average length of time to diagnosis of 8.4 years. Atypical from most cases of PPD, the patients in this study demonstrated extensive involvement of the trunk, arms, and legs.5 It has been suggested that atypical PPD is a variant of PPD that evolves into MF over many years; however, we believe that PPD is a variant of MF, similar to the way an indolent dermatitis may evolve to classical MF over time. If characterized by a T-cell clone, this period preceding the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma could be characterized as a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia.

Guitart and Magro6 noted multiple chronic conditions that are associated with T-cell clones, including PPD. These conditions occurred without a known trigger, were unresponsive to topical therapies, and often did not meet diagnostic criteria for MF. The investigators felt the criteria that may indicate a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia include widespread distribution, lymphocytic infiltrate, diminished CD7 and CD62L expression, and clonality. Lymphocytes may be small without notable atypia.6

In a study of 43 patients with PPD, Magro et al3 found monoclonality and diminished CD7 expression in 18 participants, correlating with large surface area involvement. Approximately 40% of patients had histologic findings consistent with MF, suggesting that T-cell gene rearrangement studies should be obtained for prognostic evaluation in patients with widespread disease.3

|  |

To facilitate proper patient care, histopathology and molecular markers should be evaluated in conjunction with the clinical picture. A considerable increase in the size of the body surface area affected by purpuric patches combined with the presence of poikilodermatous changes and pruritus as well as disease lasting longer than 1 year should prompt an increased clinical suspicion of MF in patients with PPD.4,5 Histologically, the presence of Pautrier microabscesses, large cerebriform lymphocytes, and intraepidermal lymphocytic atypia extending beyond the dermis also would support a diagnosis of MF.3 Given the morphologic appearance and distribution of the lesions in our patient combined with epidermotropism, diminished CD7 expression, and monoclonality seen on pathology, we favored a diagnosis of MF. It would not be unreasonable to call this clonal variant of PPD a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. We appreciate that both PPD and MF will respond to phototherapy.7

Conclusion

We propose that there is a spectrum of disease presenting as PPD or MF sitting at either end of that spectrum and an intermediate stage, where not all criteria for cutaneous lymphoma are met, characterized as cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. Until the potential for evolution of PPD to malignant disease is better understood, patients with unusual presentations of pigmented purpura should be further evaluated for MF.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854-859.

2. Koch SE, Zackheim HS, Williams ML, et al. Mycosis fungoides beginning in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:563-570.

3. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

4. Hanna S, Walsh N, D’Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

5. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

6. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

7. Seckin D, Yazici Z, Senol A, et al. A case of Schamberg’s disease responding dramatically to PUVA treatment. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:95-96.

Case Report

A healthy 17-year-old adolescent boy with an unremarkable medical history presented with an asymptomatic fixed rash on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs. The rash initially developed in a small area on the right leg 2 years prior and had slowly progressed. He was not currently taking any medications and did not participate in intense physical activity. Multiple biopsies had previously been performed by an outside physician, the most recent one demonstrating an interface and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with pigmented purpura. He did not respond to treatment with intralesional corticosteroids, high-potency topical steroids, or high-dose oral prednisone.

Clinical examination revealed multiple annular purpuric patches on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs that covered approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Over several follow-up visits, a few of the lesions evolved from patches to thin plaques. There was no adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Three additional biopsies taken over the next 4 months demonstrated a mixture of small mature lymphocytes with some atypical lymphocytes in the dermis and epidermis exhibiting diminished CD7 staining and lymphocytes lining up at the dermoepidermal junction. T-cell receptor g gene rearrangements demonstrated the same clonal population in all 3 specimens. The patient was diagnosed with stage IB mycosis fungoides (MF) of the pigmented purpura–like variant. Marked improvement of the lesions was noted after 6 weeks of psoralen plus UVA therapy 3 times weekly (Figure 2). Treatment was continued for 6 months but was discontinued due to the international shortage of methoxsalen. Two months after discontinuation, most of the lesions had completely resolved (Figure 3).

|

Comment

Mycoses fungoides is a rare cutaneous lymphoma that affects approximately 2000 patients in the United States.1 Only 5% of all cases are known to occur in the first 2 decades of life,2 and even fewer cases pre-sent with pigmented purpura, usually of the lichenoid variant.3 Although the patches and plaques of MF can masquerade as many other dermatoses (eg, dermatophytosis, psoriasis, dermatitis), there have been few reports of patients presenting with lesions with the clinical appearance of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD).4 As with the many cases of early MF, which are histologically indistinguishable from dermatitis, the pigmented purpura–like variant of MF initially may have the histologic appearance of pigmented purpura and generally evolves to the histologic appearance of MF over time.

Similar to our case, there have been reports of clinical and histologic diagnosis of PPD preceding the histologic diagnosis of MF. In a small cohort study of 3 young men, Barnhill and Braverman5 first demonstrated the progression of PPD to MF over a 12-year period. The age of onset ranged from 14 to 30 years, with a mean age of 24.3 years. Biopsies in all 3 patients were consistent with PPD for many years prior to the diagnosis of MF, with an average length of time to diagnosis of 8.4 years. Atypical from most cases of PPD, the patients in this study demonstrated extensive involvement of the trunk, arms, and legs.5 It has been suggested that atypical PPD is a variant of PPD that evolves into MF over many years; however, we believe that PPD is a variant of MF, similar to the way an indolent dermatitis may evolve to classical MF over time. If characterized by a T-cell clone, this period preceding the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma could be characterized as a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia.

Guitart and Magro6 noted multiple chronic conditions that are associated with T-cell clones, including PPD. These conditions occurred without a known trigger, were unresponsive to topical therapies, and often did not meet diagnostic criteria for MF. The investigators felt the criteria that may indicate a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia include widespread distribution, lymphocytic infiltrate, diminished CD7 and CD62L expression, and clonality. Lymphocytes may be small without notable atypia.6

In a study of 43 patients with PPD, Magro et al3 found monoclonality and diminished CD7 expression in 18 participants, correlating with large surface area involvement. Approximately 40% of patients had histologic findings consistent with MF, suggesting that T-cell gene rearrangement studies should be obtained for prognostic evaluation in patients with widespread disease.3

|  |

To facilitate proper patient care, histopathology and molecular markers should be evaluated in conjunction with the clinical picture. A considerable increase in the size of the body surface area affected by purpuric patches combined with the presence of poikilodermatous changes and pruritus as well as disease lasting longer than 1 year should prompt an increased clinical suspicion of MF in patients with PPD.4,5 Histologically, the presence of Pautrier microabscesses, large cerebriform lymphocytes, and intraepidermal lymphocytic atypia extending beyond the dermis also would support a diagnosis of MF.3 Given the morphologic appearance and distribution of the lesions in our patient combined with epidermotropism, diminished CD7 expression, and monoclonality seen on pathology, we favored a diagnosis of MF. It would not be unreasonable to call this clonal variant of PPD a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. We appreciate that both PPD and MF will respond to phototherapy.7

Conclusion

We propose that there is a spectrum of disease presenting as PPD or MF sitting at either end of that spectrum and an intermediate stage, where not all criteria for cutaneous lymphoma are met, characterized as cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. Until the potential for evolution of PPD to malignant disease is better understood, patients with unusual presentations of pigmented purpura should be further evaluated for MF.

Case Report

A healthy 17-year-old adolescent boy with an unremarkable medical history presented with an asymptomatic fixed rash on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs. The rash initially developed in a small area on the right leg 2 years prior and had slowly progressed. He was not currently taking any medications and did not participate in intense physical activity. Multiple biopsies had previously been performed by an outside physician, the most recent one demonstrating an interface and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with pigmented purpura. He did not respond to treatment with intralesional corticosteroids, high-potency topical steroids, or high-dose oral prednisone.

Clinical examination revealed multiple annular purpuric patches on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs that covered approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Over several follow-up visits, a few of the lesions evolved from patches to thin plaques. There was no adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Three additional biopsies taken over the next 4 months demonstrated a mixture of small mature lymphocytes with some atypical lymphocytes in the dermis and epidermis exhibiting diminished CD7 staining and lymphocytes lining up at the dermoepidermal junction. T-cell receptor g gene rearrangements demonstrated the same clonal population in all 3 specimens. The patient was diagnosed with stage IB mycosis fungoides (MF) of the pigmented purpura–like variant. Marked improvement of the lesions was noted after 6 weeks of psoralen plus UVA therapy 3 times weekly (Figure 2). Treatment was continued for 6 months but was discontinued due to the international shortage of methoxsalen. Two months after discontinuation, most of the lesions had completely resolved (Figure 3).

|

Comment

Mycoses fungoides is a rare cutaneous lymphoma that affects approximately 2000 patients in the United States.1 Only 5% of all cases are known to occur in the first 2 decades of life,2 and even fewer cases pre-sent with pigmented purpura, usually of the lichenoid variant.3 Although the patches and plaques of MF can masquerade as many other dermatoses (eg, dermatophytosis, psoriasis, dermatitis), there have been few reports of patients presenting with lesions with the clinical appearance of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD).4 As with the many cases of early MF, which are histologically indistinguishable from dermatitis, the pigmented purpura–like variant of MF initially may have the histologic appearance of pigmented purpura and generally evolves to the histologic appearance of MF over time.

Similar to our case, there have been reports of clinical and histologic diagnosis of PPD preceding the histologic diagnosis of MF. In a small cohort study of 3 young men, Barnhill and Braverman5 first demonstrated the progression of PPD to MF over a 12-year period. The age of onset ranged from 14 to 30 years, with a mean age of 24.3 years. Biopsies in all 3 patients were consistent with PPD for many years prior to the diagnosis of MF, with an average length of time to diagnosis of 8.4 years. Atypical from most cases of PPD, the patients in this study demonstrated extensive involvement of the trunk, arms, and legs.5 It has been suggested that atypical PPD is a variant of PPD that evolves into MF over many years; however, we believe that PPD is a variant of MF, similar to the way an indolent dermatitis may evolve to classical MF over time. If characterized by a T-cell clone, this period preceding the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma could be characterized as a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia.

Guitart and Magro6 noted multiple chronic conditions that are associated with T-cell clones, including PPD. These conditions occurred without a known trigger, were unresponsive to topical therapies, and often did not meet diagnostic criteria for MF. The investigators felt the criteria that may indicate a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia include widespread distribution, lymphocytic infiltrate, diminished CD7 and CD62L expression, and clonality. Lymphocytes may be small without notable atypia.6

In a study of 43 patients with PPD, Magro et al3 found monoclonality and diminished CD7 expression in 18 participants, correlating with large surface area involvement. Approximately 40% of patients had histologic findings consistent with MF, suggesting that T-cell gene rearrangement studies should be obtained for prognostic evaluation in patients with widespread disease.3

|  |

To facilitate proper patient care, histopathology and molecular markers should be evaluated in conjunction with the clinical picture. A considerable increase in the size of the body surface area affected by purpuric patches combined with the presence of poikilodermatous changes and pruritus as well as disease lasting longer than 1 year should prompt an increased clinical suspicion of MF in patients with PPD.4,5 Histologically, the presence of Pautrier microabscesses, large cerebriform lymphocytes, and intraepidermal lymphocytic atypia extending beyond the dermis also would support a diagnosis of MF.3 Given the morphologic appearance and distribution of the lesions in our patient combined with epidermotropism, diminished CD7 expression, and monoclonality seen on pathology, we favored a diagnosis of MF. It would not be unreasonable to call this clonal variant of PPD a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. We appreciate that both PPD and MF will respond to phototherapy.7

Conclusion

We propose that there is a spectrum of disease presenting as PPD or MF sitting at either end of that spectrum and an intermediate stage, where not all criteria for cutaneous lymphoma are met, characterized as cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. Until the potential for evolution of PPD to malignant disease is better understood, patients with unusual presentations of pigmented purpura should be further evaluated for MF.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854-859.

2. Koch SE, Zackheim HS, Williams ML, et al. Mycosis fungoides beginning in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:563-570.

3. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

4. Hanna S, Walsh N, D’Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

5. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

6. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

7. Seckin D, Yazici Z, Senol A, et al. A case of Schamberg’s disease responding dramatically to PUVA treatment. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:95-96.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854-859.

2. Koch SE, Zackheim HS, Williams ML, et al. Mycosis fungoides beginning in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:563-570.

3. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

4. Hanna S, Walsh N, D’Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

5. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

6. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

7. Seckin D, Yazici Z, Senol A, et al. A case of Schamberg’s disease responding dramatically to PUVA treatment. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:95-96.

Practice Points

- Pigmented purpuric dermatosis may lie on a spectrum with mycosis fungoides (MF).

- Pigmented purpuric dermatosis of MF should be closely followed and likely treated as MF.

- Pigmented purpuric dermatosis may have T-cell gene rearrangements that may or may not be associated with MF.