User login

Sarcoidosis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Connection Documented in a Case Series of 3 Patients

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

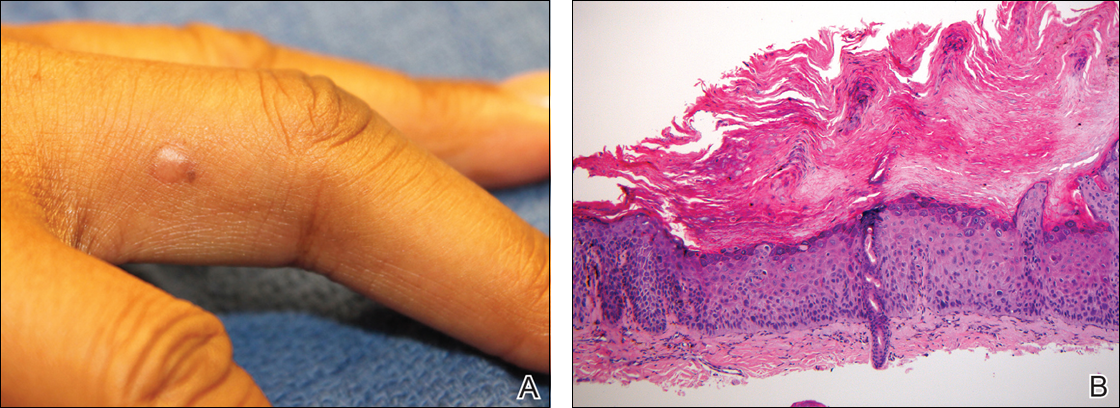

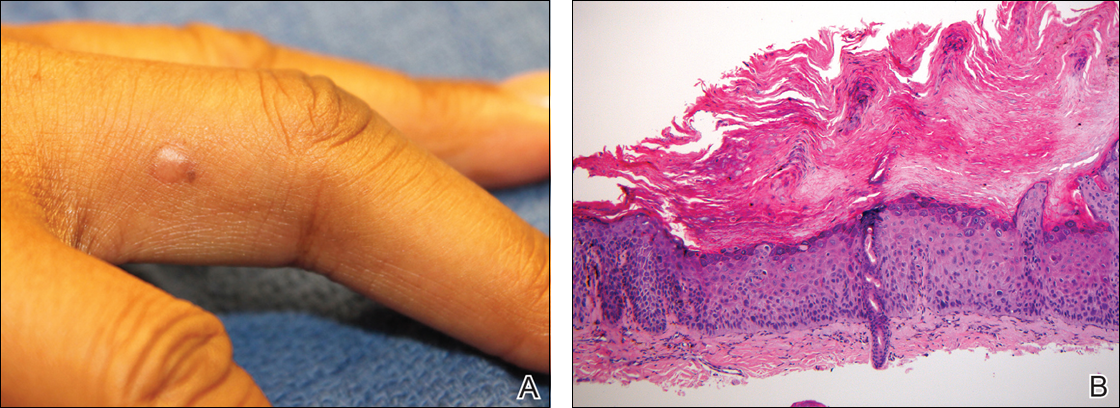

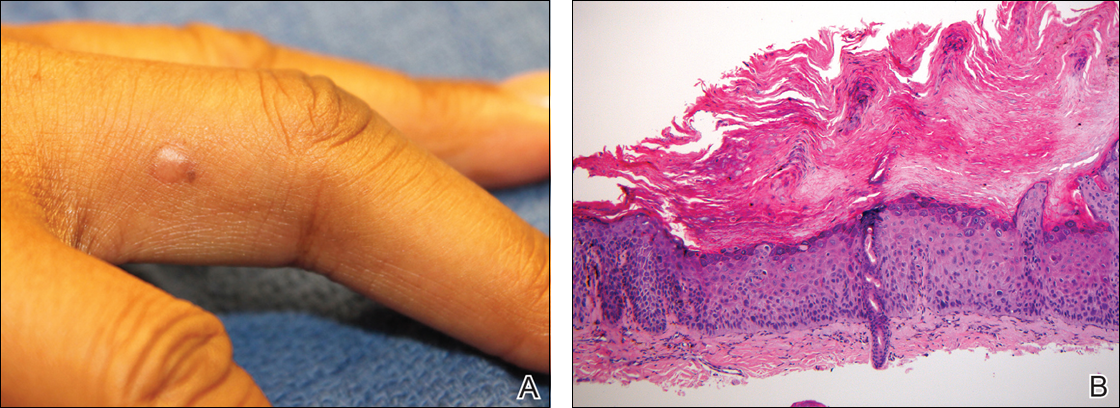

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

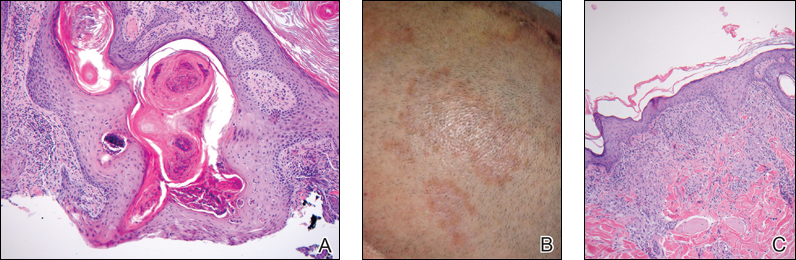

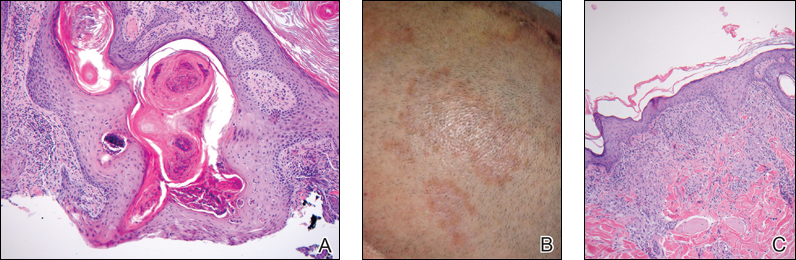

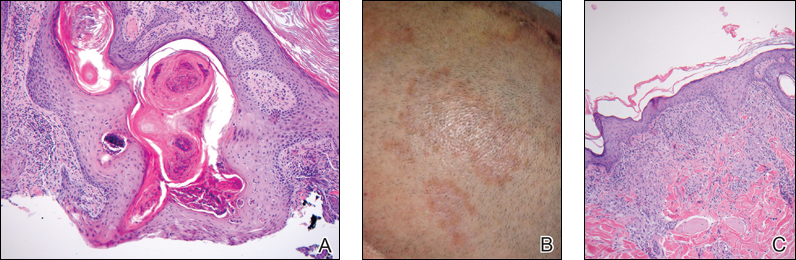

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

Practice Points

- There may be an increased risk of skin cancer in patients with sarcoidosis.

- Sarcoidosis may present with multiple morphologies, including verrucous or hyperkeratotic lesions; superficial biopsy of this type of lesion may be mistaken for a squamous cell carcinoma.

- A biopsy diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in a black patient with sarcoidosis should be carefully reviewed for evidence of deeper granulomatous inflammation.

Rare Angioinvasive Fungal Infection in Association With Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis (LC) is characterized by the infiltration of malignant neoplastic leukocytes or their precursors into the skin, most often in conjunction with systemic leukemia.1 Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the second most common cause of LC and the most common form of leukemia among adults.1 Patients with leukemia often are in a relative or absolute immunocompromised state, which may be secondary to neutropenia, chemotherapy regimens, or immunosuppressive regimens following stem cell transplant (SCT). Thus, when evaluating cutaneous lesions consistent with LC in immunocompromised patients, there must be a high index of suspicion for concomitant opportunistic infections.

We report the case of a 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML following allogeneic SCT with relapse who presented with an LC lesion below the knee with concomitant invasive fungal infection despite being on prophylactic oral antifungal therapy.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML (M1) of 1 year’s duration presented for evaluation of a slowly progressing reddish purple nodule on the right knee of 2 to 4 months’ duration. The patient had undergone a matched unrelated donor allogeneic SCT 6 months following diagnosis of AML with subsequent disease progression despite reduction of posttransplant graft-versus-host disease prophylactic immune suppression and a cycle of clofarabine. The patient was hospitalized 2 months after the SCT for neutropenic fever and was found to have vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia, Clostridium difficile colitis, and possible fungal pneumonia. He was treated with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, which he continued following discharge for antifungal prophylaxis. At the time of discharge, the patient reported that he noticed an asymptomatic “purple papule” on the right knee but did not seek further workup.

Two months later, the patient presented with a fever (temperature, 38.6°C) and leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 130 cells/mL [increased from 53 cells/mL 1 week prior to admission]). Due to his history of immunosuppression and neutropenia, the patient was placed on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of cefepime, daptomycin, and linezolid on admission. Later, vancomycin and gentamicin were added and voriconazole was switched to caspofungin. The patient also received granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia. During the current hospitalization, blood cultures demonstrated vancomycin-resistant enterococcemia, and computed tomography of the chest revealed findings consistent with multilobar pneumonia.

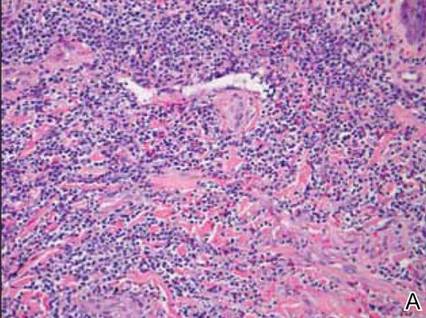

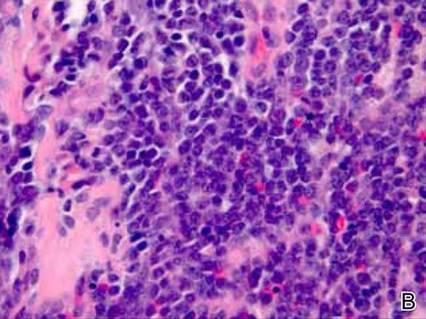

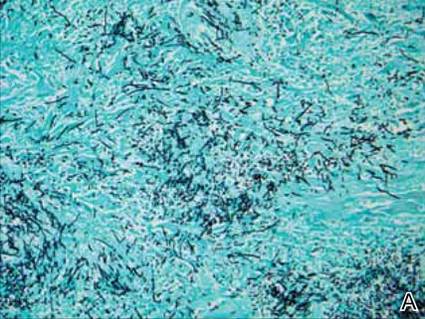

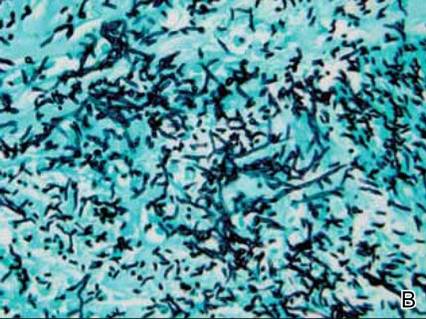

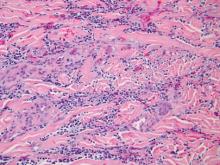

Dermatology was consulted to evaluate the purple nodule on the right knee, which had slowly progressed since his last admission. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, 1.5×1.5-cm nodule with central necrosis covered by black eschar with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Biopsy specimens for routine histology and a tissue culture were obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense diffuse infiltrate of large hyperchromatic mononuclear cells extending through the dermis, which was consistent with the patient’s known AML (Figure 2). Acid-fast bacillus staining was negative for mycobacterial organisms. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated an overwhelming number of septate fungal hyphae with acute-angle branching, concerning for Aspergillus species (Figure 3). Of note, an Aspergillus serum antigen test was performed at this time and was negative. On repeat review of the routine histologic sections, angioinvasion by hyphae was detected amidst the dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Given the patient’s immunocompromised state, the presence of angioinvasive fungi on the skin biopsy, and unresolved pneumonia, the patient was restarted on voriconazole for treatment of likely Aspergillus infection. He was continued on chemotherapy for the primary refractory AML and received a donor lymphocyte infusion prior to discharge. After the patient was discharged, the tissue culture grew Paecilomyces, a rare fungal species. The patient died 1 week after discharge.

|

|

Comment

Leukemia cutis is an extramedullary manifestation of leukemia that appears in 10% to 15% of patients with AML.2 The frequency of LC differs widely for the various types of AML, with the majority of cases occurring in the acute myelomonocytic leukemia (M4) or acute monocytic leukemia (M5) subtypes.3,4 One large study of AML patients (N=381) demonstrated an incidence of LC in 28.6% of patients with the M4 subtype and 42.9% of those with the M5 subtype, with an incidence of only 7.1% of patients with the M1 subtype.3 It occurs less frequently in chronic myeloproliferative diseases.2,4

Leukemia cutis has a wide range of cutaneous manifestations and may present with solitary or multiple papular, nodular, or plaquelike lesions that are red-brown, blue, violaceous, or hemorrhagic.4 Leukemia cutis occurs most commonly on the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.2,4 Leukemia cutis may be hard to distinguish clinically from other conditions such as cutaneous metastases of visceral malignancies, lymphoma, drug eruptions, and opportunistic infections. Leukemia cutis ulcers often measure only a few centimeters in diameter with a firmly adherent purulent or hemorrhagic crust and may occur in unusual locations. These lesions usually are treatment resistant and their persistence may help to lead to diagnosis.4

Microscopically, most LC lesions show a perivascular or periadnexal pattern of involvement or a dense diffuse, interstitial, or nodular atypical lymphocytic infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutis with sparing of the upper papillary dermis.2 The cytologic appearance of M1 and M2 subtypes of AML are characterized by medium-sized to large mononuclear cells with a light cytoplasm and large basophilic cell nuclei. The M4 and M5 subtypes of AML generally are dominated by medium-sized, round or oval-shaped mononuclear cells that may have eosinophilic cytoplasm and segmented or kidney-shaped basophilic nuclei.4 Immunophenotyping is crucial for diagnosis. In myeloid disorders, there is positive staining with markers of myeloid lineage such as myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, CD34, CD15, CD68, CD43, and CD117.5

In our patient, there was an ulcerated dense diffuse dermal infiltrate of large atypical lymphocytes consistent with LC and positive immunostaining consistent with LC associated with AML. Additionally, septate hyphae with acute-angle branching also were noted in the dermal blood vessels on hematoxylin and eosin and fungal staining, demonstrating concomitant fungal infection. Angioinvasion of organisms demonstrated on skin biopsy and persistent pneumonia noted on chest imaging suggested a disseminated infectious process.

Invasive fungal infections are an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised individuals, including those with hematologic malignancies and hematologic SCTs. Despite an increasing number of antifungal therapies, outcomes are frequently suboptimal with mortality rates often greater than 50% depending on the pathogen and disease.6 Thus, there must be a high index of suspicion of infection even when a separate histopathologic diagnosis is available, such as the finding of leukemic infiltrates in this patient’s biopsy specimen. A similar case of LC has been reported with concomitant fungal infection involving Fusarium and Enterococcus.7 Patients with leukemic cells may develop leukemic infiltrates in response to cutaneous infection, and a high index of suspicion for 2 related but distinct processes is necessary.

Paecilomyces species are an emerging cause of opportunistic and usually severe human infections.8-11 The Paecilomyces species are saprophytic filamentous fungi that are found worldwide in soil as well as contaminants in the air and water.12Paecilomyces infection is generally associated with the use of immunosuppressive therapies, implants, or ocular surgery. Among species in this genus, Paecilomyces lilacinus and Paecilomyces variotii are of clinical importance. Most species have high susceptibility to the newer azoles such as voriconazole.6

Conclusion

Despite continued treatment with voriconazole, our patient still developed a rare fungal infection arising in a lesion of LC. He had signs of infection, including an elevated white blood cell count, fever, and malaise, which are nonspecific clinical findings that could have been attributed to known relapse of systemic leukemia or to known enterococcemia. Even in patients on antifungal prophylaxis and with other possible causes of leukocytosis, this case illustrates that there must be a high index of suspicion for angioinvasive fungal infection.

1. Aquilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

2. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros J, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130.

3. Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:90-95.

4. Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, et al. Leukemia cutis—epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:27-36.

5. Hejmadi RK, Thompson D, Shah F, et al. Cutaneous presentation of aleukemic monoblastic leukemia cutis: a case report and review of literature with focus on immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):46.

6. Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive mycoses: strategies for effective management. Am J Med. 2012;125(suppl 1):25-38.

7. Feramisco JD, Hsiao JL, Fox LP, et al. Angioinvasive Fusarium and concomitant Enterococcus infection arising in association with leukemia cutis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:926-929.

8. Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099-1117.

9. Carey J, D’Amico R, Sutton DA, et al. Paecilomyces lilacinus vaginitis in an immuno-competent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1155-1158.

10. Castro LG, Salebian A, Sotto MN. Hyalohyphomycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient and a review of human Paecilomyces species infections. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:15-26.

11. Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:948-960.

12. Castelli MV, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, et al. Susceptibility testing and molecular classification of Paecilomyces spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2926-2928.

Leukemia cutis (LC) is characterized by the infiltration of malignant neoplastic leukocytes or their precursors into the skin, most often in conjunction with systemic leukemia.1 Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the second most common cause of LC and the most common form of leukemia among adults.1 Patients with leukemia often are in a relative or absolute immunocompromised state, which may be secondary to neutropenia, chemotherapy regimens, or immunosuppressive regimens following stem cell transplant (SCT). Thus, when evaluating cutaneous lesions consistent with LC in immunocompromised patients, there must be a high index of suspicion for concomitant opportunistic infections.

We report the case of a 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML following allogeneic SCT with relapse who presented with an LC lesion below the knee with concomitant invasive fungal infection despite being on prophylactic oral antifungal therapy.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML (M1) of 1 year’s duration presented for evaluation of a slowly progressing reddish purple nodule on the right knee of 2 to 4 months’ duration. The patient had undergone a matched unrelated donor allogeneic SCT 6 months following diagnosis of AML with subsequent disease progression despite reduction of posttransplant graft-versus-host disease prophylactic immune suppression and a cycle of clofarabine. The patient was hospitalized 2 months after the SCT for neutropenic fever and was found to have vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia, Clostridium difficile colitis, and possible fungal pneumonia. He was treated with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, which he continued following discharge for antifungal prophylaxis. At the time of discharge, the patient reported that he noticed an asymptomatic “purple papule” on the right knee but did not seek further workup.

Two months later, the patient presented with a fever (temperature, 38.6°C) and leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 130 cells/mL [increased from 53 cells/mL 1 week prior to admission]). Due to his history of immunosuppression and neutropenia, the patient was placed on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of cefepime, daptomycin, and linezolid on admission. Later, vancomycin and gentamicin were added and voriconazole was switched to caspofungin. The patient also received granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia. During the current hospitalization, blood cultures demonstrated vancomycin-resistant enterococcemia, and computed tomography of the chest revealed findings consistent with multilobar pneumonia.

Dermatology was consulted to evaluate the purple nodule on the right knee, which had slowly progressed since his last admission. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, 1.5×1.5-cm nodule with central necrosis covered by black eschar with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Biopsy specimens for routine histology and a tissue culture were obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense diffuse infiltrate of large hyperchromatic mononuclear cells extending through the dermis, which was consistent with the patient’s known AML (Figure 2). Acid-fast bacillus staining was negative for mycobacterial organisms. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated an overwhelming number of septate fungal hyphae with acute-angle branching, concerning for Aspergillus species (Figure 3). Of note, an Aspergillus serum antigen test was performed at this time and was negative. On repeat review of the routine histologic sections, angioinvasion by hyphae was detected amidst the dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Given the patient’s immunocompromised state, the presence of angioinvasive fungi on the skin biopsy, and unresolved pneumonia, the patient was restarted on voriconazole for treatment of likely Aspergillus infection. He was continued on chemotherapy for the primary refractory AML and received a donor lymphocyte infusion prior to discharge. After the patient was discharged, the tissue culture grew Paecilomyces, a rare fungal species. The patient died 1 week after discharge.

|

|

Comment

Leukemia cutis is an extramedullary manifestation of leukemia that appears in 10% to 15% of patients with AML.2 The frequency of LC differs widely for the various types of AML, with the majority of cases occurring in the acute myelomonocytic leukemia (M4) or acute monocytic leukemia (M5) subtypes.3,4 One large study of AML patients (N=381) demonstrated an incidence of LC in 28.6% of patients with the M4 subtype and 42.9% of those with the M5 subtype, with an incidence of only 7.1% of patients with the M1 subtype.3 It occurs less frequently in chronic myeloproliferative diseases.2,4

Leukemia cutis has a wide range of cutaneous manifestations and may present with solitary or multiple papular, nodular, or plaquelike lesions that are red-brown, blue, violaceous, or hemorrhagic.4 Leukemia cutis occurs most commonly on the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.2,4 Leukemia cutis may be hard to distinguish clinically from other conditions such as cutaneous metastases of visceral malignancies, lymphoma, drug eruptions, and opportunistic infections. Leukemia cutis ulcers often measure only a few centimeters in diameter with a firmly adherent purulent or hemorrhagic crust and may occur in unusual locations. These lesions usually are treatment resistant and their persistence may help to lead to diagnosis.4

Microscopically, most LC lesions show a perivascular or periadnexal pattern of involvement or a dense diffuse, interstitial, or nodular atypical lymphocytic infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutis with sparing of the upper papillary dermis.2 The cytologic appearance of M1 and M2 subtypes of AML are characterized by medium-sized to large mononuclear cells with a light cytoplasm and large basophilic cell nuclei. The M4 and M5 subtypes of AML generally are dominated by medium-sized, round or oval-shaped mononuclear cells that may have eosinophilic cytoplasm and segmented or kidney-shaped basophilic nuclei.4 Immunophenotyping is crucial for diagnosis. In myeloid disorders, there is positive staining with markers of myeloid lineage such as myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, CD34, CD15, CD68, CD43, and CD117.5

In our patient, there was an ulcerated dense diffuse dermal infiltrate of large atypical lymphocytes consistent with LC and positive immunostaining consistent with LC associated with AML. Additionally, septate hyphae with acute-angle branching also were noted in the dermal blood vessels on hematoxylin and eosin and fungal staining, demonstrating concomitant fungal infection. Angioinvasion of organisms demonstrated on skin biopsy and persistent pneumonia noted on chest imaging suggested a disseminated infectious process.

Invasive fungal infections are an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised individuals, including those with hematologic malignancies and hematologic SCTs. Despite an increasing number of antifungal therapies, outcomes are frequently suboptimal with mortality rates often greater than 50% depending on the pathogen and disease.6 Thus, there must be a high index of suspicion of infection even when a separate histopathologic diagnosis is available, such as the finding of leukemic infiltrates in this patient’s biopsy specimen. A similar case of LC has been reported with concomitant fungal infection involving Fusarium and Enterococcus.7 Patients with leukemic cells may develop leukemic infiltrates in response to cutaneous infection, and a high index of suspicion for 2 related but distinct processes is necessary.

Paecilomyces species are an emerging cause of opportunistic and usually severe human infections.8-11 The Paecilomyces species are saprophytic filamentous fungi that are found worldwide in soil as well as contaminants in the air and water.12Paecilomyces infection is generally associated with the use of immunosuppressive therapies, implants, or ocular surgery. Among species in this genus, Paecilomyces lilacinus and Paecilomyces variotii are of clinical importance. Most species have high susceptibility to the newer azoles such as voriconazole.6

Conclusion

Despite continued treatment with voriconazole, our patient still developed a rare fungal infection arising in a lesion of LC. He had signs of infection, including an elevated white blood cell count, fever, and malaise, which are nonspecific clinical findings that could have been attributed to known relapse of systemic leukemia or to known enterococcemia. Even in patients on antifungal prophylaxis and with other possible causes of leukocytosis, this case illustrates that there must be a high index of suspicion for angioinvasive fungal infection.

Leukemia cutis (LC) is characterized by the infiltration of malignant neoplastic leukocytes or their precursors into the skin, most often in conjunction with systemic leukemia.1 Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the second most common cause of LC and the most common form of leukemia among adults.1 Patients with leukemia often are in a relative or absolute immunocompromised state, which may be secondary to neutropenia, chemotherapy regimens, or immunosuppressive regimens following stem cell transplant (SCT). Thus, when evaluating cutaneous lesions consistent with LC in immunocompromised patients, there must be a high index of suspicion for concomitant opportunistic infections.

We report the case of a 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML following allogeneic SCT with relapse who presented with an LC lesion below the knee with concomitant invasive fungal infection despite being on prophylactic oral antifungal therapy.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML (M1) of 1 year’s duration presented for evaluation of a slowly progressing reddish purple nodule on the right knee of 2 to 4 months’ duration. The patient had undergone a matched unrelated donor allogeneic SCT 6 months following diagnosis of AML with subsequent disease progression despite reduction of posttransplant graft-versus-host disease prophylactic immune suppression and a cycle of clofarabine. The patient was hospitalized 2 months after the SCT for neutropenic fever and was found to have vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia, Clostridium difficile colitis, and possible fungal pneumonia. He was treated with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, which he continued following discharge for antifungal prophylaxis. At the time of discharge, the patient reported that he noticed an asymptomatic “purple papule” on the right knee but did not seek further workup.

Two months later, the patient presented with a fever (temperature, 38.6°C) and leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 130 cells/mL [increased from 53 cells/mL 1 week prior to admission]). Due to his history of immunosuppression and neutropenia, the patient was placed on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of cefepime, daptomycin, and linezolid on admission. Later, vancomycin and gentamicin were added and voriconazole was switched to caspofungin. The patient also received granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia. During the current hospitalization, blood cultures demonstrated vancomycin-resistant enterococcemia, and computed tomography of the chest revealed findings consistent with multilobar pneumonia.

Dermatology was consulted to evaluate the purple nodule on the right knee, which had slowly progressed since his last admission. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, 1.5×1.5-cm nodule with central necrosis covered by black eschar with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Biopsy specimens for routine histology and a tissue culture were obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense diffuse infiltrate of large hyperchromatic mononuclear cells extending through the dermis, which was consistent with the patient’s known AML (Figure 2). Acid-fast bacillus staining was negative for mycobacterial organisms. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated an overwhelming number of septate fungal hyphae with acute-angle branching, concerning for Aspergillus species (Figure 3). Of note, an Aspergillus serum antigen test was performed at this time and was negative. On repeat review of the routine histologic sections, angioinvasion by hyphae was detected amidst the dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Given the patient’s immunocompromised state, the presence of angioinvasive fungi on the skin biopsy, and unresolved pneumonia, the patient was restarted on voriconazole for treatment of likely Aspergillus infection. He was continued on chemotherapy for the primary refractory AML and received a donor lymphocyte infusion prior to discharge. After the patient was discharged, the tissue culture grew Paecilomyces, a rare fungal species. The patient died 1 week after discharge.

|

|

Comment

Leukemia cutis is an extramedullary manifestation of leukemia that appears in 10% to 15% of patients with AML.2 The frequency of LC differs widely for the various types of AML, with the majority of cases occurring in the acute myelomonocytic leukemia (M4) or acute monocytic leukemia (M5) subtypes.3,4 One large study of AML patients (N=381) demonstrated an incidence of LC in 28.6% of patients with the M4 subtype and 42.9% of those with the M5 subtype, with an incidence of only 7.1% of patients with the M1 subtype.3 It occurs less frequently in chronic myeloproliferative diseases.2,4

Leukemia cutis has a wide range of cutaneous manifestations and may present with solitary or multiple papular, nodular, or plaquelike lesions that are red-brown, blue, violaceous, or hemorrhagic.4 Leukemia cutis occurs most commonly on the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.2,4 Leukemia cutis may be hard to distinguish clinically from other conditions such as cutaneous metastases of visceral malignancies, lymphoma, drug eruptions, and opportunistic infections. Leukemia cutis ulcers often measure only a few centimeters in diameter with a firmly adherent purulent or hemorrhagic crust and may occur in unusual locations. These lesions usually are treatment resistant and their persistence may help to lead to diagnosis.4

Microscopically, most LC lesions show a perivascular or periadnexal pattern of involvement or a dense diffuse, interstitial, or nodular atypical lymphocytic infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutis with sparing of the upper papillary dermis.2 The cytologic appearance of M1 and M2 subtypes of AML are characterized by medium-sized to large mononuclear cells with a light cytoplasm and large basophilic cell nuclei. The M4 and M5 subtypes of AML generally are dominated by medium-sized, round or oval-shaped mononuclear cells that may have eosinophilic cytoplasm and segmented or kidney-shaped basophilic nuclei.4 Immunophenotyping is crucial for diagnosis. In myeloid disorders, there is positive staining with markers of myeloid lineage such as myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, CD34, CD15, CD68, CD43, and CD117.5

In our patient, there was an ulcerated dense diffuse dermal infiltrate of large atypical lymphocytes consistent with LC and positive immunostaining consistent with LC associated with AML. Additionally, septate hyphae with acute-angle branching also were noted in the dermal blood vessels on hematoxylin and eosin and fungal staining, demonstrating concomitant fungal infection. Angioinvasion of organisms demonstrated on skin biopsy and persistent pneumonia noted on chest imaging suggested a disseminated infectious process.

Invasive fungal infections are an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised individuals, including those with hematologic malignancies and hematologic SCTs. Despite an increasing number of antifungal therapies, outcomes are frequently suboptimal with mortality rates often greater than 50% depending on the pathogen and disease.6 Thus, there must be a high index of suspicion of infection even when a separate histopathologic diagnosis is available, such as the finding of leukemic infiltrates in this patient’s biopsy specimen. A similar case of LC has been reported with concomitant fungal infection involving Fusarium and Enterococcus.7 Patients with leukemic cells may develop leukemic infiltrates in response to cutaneous infection, and a high index of suspicion for 2 related but distinct processes is necessary.

Paecilomyces species are an emerging cause of opportunistic and usually severe human infections.8-11 The Paecilomyces species are saprophytic filamentous fungi that are found worldwide in soil as well as contaminants in the air and water.12Paecilomyces infection is generally associated with the use of immunosuppressive therapies, implants, or ocular surgery. Among species in this genus, Paecilomyces lilacinus and Paecilomyces variotii are of clinical importance. Most species have high susceptibility to the newer azoles such as voriconazole.6

Conclusion

Despite continued treatment with voriconazole, our patient still developed a rare fungal infection arising in a lesion of LC. He had signs of infection, including an elevated white blood cell count, fever, and malaise, which are nonspecific clinical findings that could have been attributed to known relapse of systemic leukemia or to known enterococcemia. Even in patients on antifungal prophylaxis and with other possible causes of leukocytosis, this case illustrates that there must be a high index of suspicion for angioinvasive fungal infection.

1. Aquilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

2. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros J, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130.

3. Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:90-95.

4. Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, et al. Leukemia cutis—epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:27-36.

5. Hejmadi RK, Thompson D, Shah F, et al. Cutaneous presentation of aleukemic monoblastic leukemia cutis: a case report and review of literature with focus on immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):46.

6. Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive mycoses: strategies for effective management. Am J Med. 2012;125(suppl 1):25-38.

7. Feramisco JD, Hsiao JL, Fox LP, et al. Angioinvasive Fusarium and concomitant Enterococcus infection arising in association with leukemia cutis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:926-929.

8. Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099-1117.

9. Carey J, D’Amico R, Sutton DA, et al. Paecilomyces lilacinus vaginitis in an immuno-competent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1155-1158.

10. Castro LG, Salebian A, Sotto MN. Hyalohyphomycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient and a review of human Paecilomyces species infections. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:15-26.

11. Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:948-960.

12. Castelli MV, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, et al. Susceptibility testing and molecular classification of Paecilomyces spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2926-2928.

1. Aquilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

2. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros J, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130.

3. Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:90-95.

4. Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, et al. Leukemia cutis—epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:27-36.

5. Hejmadi RK, Thompson D, Shah F, et al. Cutaneous presentation of aleukemic monoblastic leukemia cutis: a case report and review of literature with focus on immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):46.

6. Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive mycoses: strategies for effective management. Am J Med. 2012;125(suppl 1):25-38.

7. Feramisco JD, Hsiao JL, Fox LP, et al. Angioinvasive Fusarium and concomitant Enterococcus infection arising in association with leukemia cutis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:926-929.

8. Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099-1117.

9. Carey J, D’Amico R, Sutton DA, et al. Paecilomyces lilacinus vaginitis in an immuno-competent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1155-1158.

10. Castro LG, Salebian A, Sotto MN. Hyalohyphomycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient and a review of human Paecilomyces species infections. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:15-26.

11. Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:948-960.

12. Castelli MV, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, et al. Susceptibility testing and molecular classification of Paecilomyces spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2926-2928.

Practice Points

- Immunosuppressed patients are at risk for atypical presentations of common infections as well as infection with rare pathogens.

- Skin biopsy and tissue culture play an important role in identifying infectious agents in immunosuppressed patients.

- Leukemic infiltrates may mask pathogens, and pathologists should strongly consider additional stains when indicated.