User login

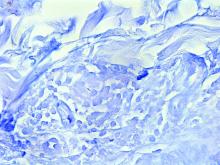

A White male presented with a 1½-year history of a progressive hypoesthetic annular, hyperpigmented plaque on the upper arm

Paucibacillary tuberculoid leprosy is characterized by few anesthetic hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions and can be accompanied by palpable peripheral nerve enlargements.

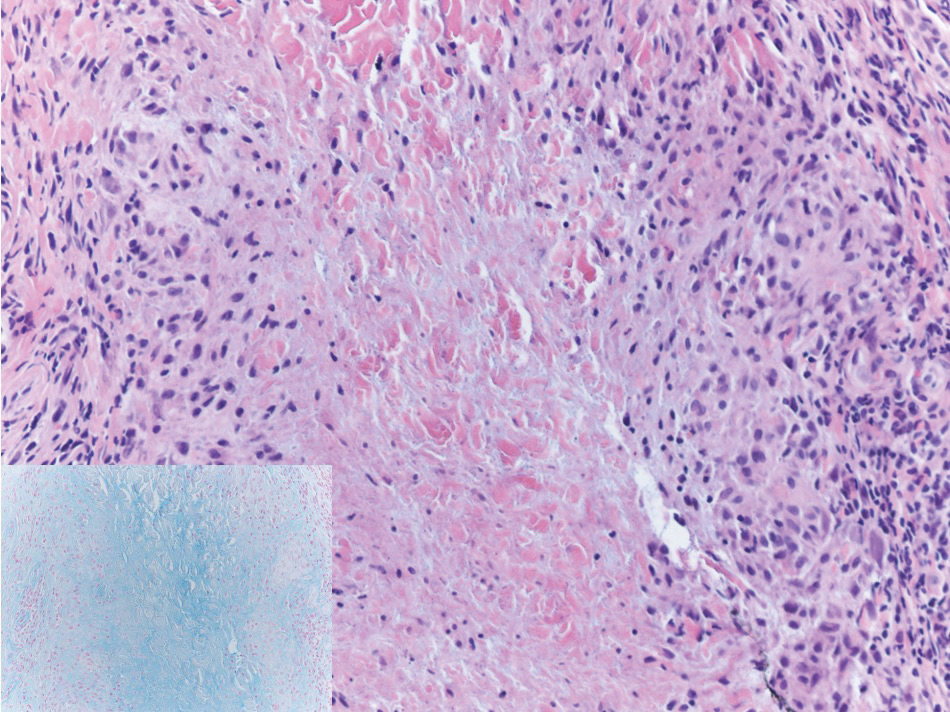

Tuberculoid leprosy presents histologically with epithelioid histiocytes with lymphocytes and Langhans giant cells. Neurotropic granulomas are also characteristic of tuberculoid leprosy. Fite staining allows for the identification of the acid-fast bacilli of M. leprae, which in some cases are quite few in number. The standard mycobacterium stain, Ziehl-Neelsen, is a good option for M. tuberculosis, but because of the relative weak mycolic acid coat of M. leprae, the Fite stain is more appropriate for identifying M. leprae.

Clinically, other than the presence of fewer than five hypoesthetic lesions that are either hypopigmented or erythematous, tuberculoid leprosy often presents with additional peripheral nerve involvement that manifests as numbness and tingling in hands and feet.1 This patient denied any tingling, weakness, or numbness, outside of the anesthetic lesion on his posterior upper arm.

The patient, born in the United States, had a remote history of military travel to Iraq, Kuwait, and the Philippines, but had not traveled internationally within the last 15 years, apart from a cruise to the Bahamas. He denied any known contact with individuals with similar lesions. He denied a history of contact with armadillos, but acknowledged that they are native to where he resides in central Florida, and that he had seen them in his yard.

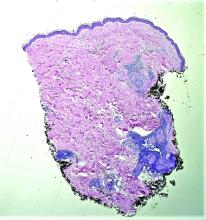

Histopathological examination revealed an unremarkable epidermis with a superficial and deep perivascular, periadnexal, and perineural lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Fite stain revealed rare rod-shaped organisms (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of paucibacillary, tuberculoid leprosy.

The patient’s travel history to highly endemic areas (Middle East), as well as possible environmental contact with armadillos – including contact with soil that the armadillos occupied – could explain plausible modes of transmission. Following consultation with our infectious disease department and the National Hansen’s Disease Program, our patient began a planned course of therapy with 18 months of minocycline, rifampin, and moxifloxacin.

Human-to-human transmission of HD has been well documented; however, zoonotic transmission – specifically via the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) – serves as another suggested means of transmission, especially in the Southeastern United States.2-6 Travel to highly-endemic areas increases the risk of contracting HD, which may take up to 20 years following contact with the bacteria to manifest clinically.

While central Florida was previously thought to be a nonendemic area of disease, the incidence of the disease in this region has increased in recent years.7 Human-to-human transmission, which remains a concern with immigration from highly-endemic regions, occurs via long-term contact with nasal droplets of an infected person.8,9

Many patients in regions with very few cases of leprosy deny travel to other endemic regions and contact with infected people. Thus, zoonotic transmission remains a legitimate concern in the Southeastern United States – accounting, at least in part, for many of the non–human-transmitted cases of leprosy.2,10 We encourage clinicians to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for leprosy when evaluating patients presenting with hypoesthetic cutaneous lesions and to obtain a travel history and to ask about armadillo exposure.

This case and the photos were submitted by Ms. Smith, from the University of South Florida, Tampa; Dr. Hatch and Dr. Sarriera-Lazaro, from the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of South Florida; and Dr. Turner and Dr. Beachkofsky, from the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, Tampa. Dr. Bilu Martin edited this case. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease), in: “Goldman’s Cecil Medicine,” 24th ed. (Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2012: pp. 1950-4.

2. Sharma R et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2127-34.

3. Lane JE et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):714-6.

4. Clark BM et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Jun;78(6):962-7.

5. Bruce S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Aug;43(2 Pt 1):223-8.

6. Loughry WJ et al. J Wildl Dis. 2009 Jan;45(1):144-52.

7. FDo H. Florida charts: Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy). Health FDo. 2019. https://www.flhealthcharts.gov/ChartsReports/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=NonVitalIndNoGrpCounts.DataViewer&cid=174.

8. Maymone MBC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul;83(1):1-14.

9. Scollard DM et al. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006 Apr;19(2):338-81.

10. Domozych R et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2016 May 12;2(3):189-92.

Paucibacillary tuberculoid leprosy is characterized by few anesthetic hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions and can be accompanied by palpable peripheral nerve enlargements.

Tuberculoid leprosy presents histologically with epithelioid histiocytes with lymphocytes and Langhans giant cells. Neurotropic granulomas are also characteristic of tuberculoid leprosy. Fite staining allows for the identification of the acid-fast bacilli of M. leprae, which in some cases are quite few in number. The standard mycobacterium stain, Ziehl-Neelsen, is a good option for M. tuberculosis, but because of the relative weak mycolic acid coat of M. leprae, the Fite stain is more appropriate for identifying M. leprae.

Clinically, other than the presence of fewer than five hypoesthetic lesions that are either hypopigmented or erythematous, tuberculoid leprosy often presents with additional peripheral nerve involvement that manifests as numbness and tingling in hands and feet.1 This patient denied any tingling, weakness, or numbness, outside of the anesthetic lesion on his posterior upper arm.

The patient, born in the United States, had a remote history of military travel to Iraq, Kuwait, and the Philippines, but had not traveled internationally within the last 15 years, apart from a cruise to the Bahamas. He denied any known contact with individuals with similar lesions. He denied a history of contact with armadillos, but acknowledged that they are native to where he resides in central Florida, and that he had seen them in his yard.

Histopathological examination revealed an unremarkable epidermis with a superficial and deep perivascular, periadnexal, and perineural lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Fite stain revealed rare rod-shaped organisms (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of paucibacillary, tuberculoid leprosy.

The patient’s travel history to highly endemic areas (Middle East), as well as possible environmental contact with armadillos – including contact with soil that the armadillos occupied – could explain plausible modes of transmission. Following consultation with our infectious disease department and the National Hansen’s Disease Program, our patient began a planned course of therapy with 18 months of minocycline, rifampin, and moxifloxacin.

Human-to-human transmission of HD has been well documented; however, zoonotic transmission – specifically via the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) – serves as another suggested means of transmission, especially in the Southeastern United States.2-6 Travel to highly-endemic areas increases the risk of contracting HD, which may take up to 20 years following contact with the bacteria to manifest clinically.

While central Florida was previously thought to be a nonendemic area of disease, the incidence of the disease in this region has increased in recent years.7 Human-to-human transmission, which remains a concern with immigration from highly-endemic regions, occurs via long-term contact with nasal droplets of an infected person.8,9

Many patients in regions with very few cases of leprosy deny travel to other endemic regions and contact with infected people. Thus, zoonotic transmission remains a legitimate concern in the Southeastern United States – accounting, at least in part, for many of the non–human-transmitted cases of leprosy.2,10 We encourage clinicians to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for leprosy when evaluating patients presenting with hypoesthetic cutaneous lesions and to obtain a travel history and to ask about armadillo exposure.

This case and the photos were submitted by Ms. Smith, from the University of South Florida, Tampa; Dr. Hatch and Dr. Sarriera-Lazaro, from the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of South Florida; and Dr. Turner and Dr. Beachkofsky, from the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, Tampa. Dr. Bilu Martin edited this case. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease), in: “Goldman’s Cecil Medicine,” 24th ed. (Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2012: pp. 1950-4.

2. Sharma R et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2127-34.

3. Lane JE et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):714-6.

4. Clark BM et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Jun;78(6):962-7.

5. Bruce S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Aug;43(2 Pt 1):223-8.

6. Loughry WJ et al. J Wildl Dis. 2009 Jan;45(1):144-52.

7. FDo H. Florida charts: Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy). Health FDo. 2019. https://www.flhealthcharts.gov/ChartsReports/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=NonVitalIndNoGrpCounts.DataViewer&cid=174.

8. Maymone MBC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul;83(1):1-14.

9. Scollard DM et al. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006 Apr;19(2):338-81.

10. Domozych R et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2016 May 12;2(3):189-92.

Paucibacillary tuberculoid leprosy is characterized by few anesthetic hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions and can be accompanied by palpable peripheral nerve enlargements.

Tuberculoid leprosy presents histologically with epithelioid histiocytes with lymphocytes and Langhans giant cells. Neurotropic granulomas are also characteristic of tuberculoid leprosy. Fite staining allows for the identification of the acid-fast bacilli of M. leprae, which in some cases are quite few in number. The standard mycobacterium stain, Ziehl-Neelsen, is a good option for M. tuberculosis, but because of the relative weak mycolic acid coat of M. leprae, the Fite stain is more appropriate for identifying M. leprae.

Clinically, other than the presence of fewer than five hypoesthetic lesions that are either hypopigmented or erythematous, tuberculoid leprosy often presents with additional peripheral nerve involvement that manifests as numbness and tingling in hands and feet.1 This patient denied any tingling, weakness, or numbness, outside of the anesthetic lesion on his posterior upper arm.

The patient, born in the United States, had a remote history of military travel to Iraq, Kuwait, and the Philippines, but had not traveled internationally within the last 15 years, apart from a cruise to the Bahamas. He denied any known contact with individuals with similar lesions. He denied a history of contact with armadillos, but acknowledged that they are native to where he resides in central Florida, and that he had seen them in his yard.

Histopathological examination revealed an unremarkable epidermis with a superficial and deep perivascular, periadnexal, and perineural lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Fite stain revealed rare rod-shaped organisms (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of paucibacillary, tuberculoid leprosy.

The patient’s travel history to highly endemic areas (Middle East), as well as possible environmental contact with armadillos – including contact with soil that the armadillos occupied – could explain plausible modes of transmission. Following consultation with our infectious disease department and the National Hansen’s Disease Program, our patient began a planned course of therapy with 18 months of minocycline, rifampin, and moxifloxacin.

Human-to-human transmission of HD has been well documented; however, zoonotic transmission – specifically via the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) – serves as another suggested means of transmission, especially in the Southeastern United States.2-6 Travel to highly-endemic areas increases the risk of contracting HD, which may take up to 20 years following contact with the bacteria to manifest clinically.

While central Florida was previously thought to be a nonendemic area of disease, the incidence of the disease in this region has increased in recent years.7 Human-to-human transmission, which remains a concern with immigration from highly-endemic regions, occurs via long-term contact with nasal droplets of an infected person.8,9

Many patients in regions with very few cases of leprosy deny travel to other endemic regions and contact with infected people. Thus, zoonotic transmission remains a legitimate concern in the Southeastern United States – accounting, at least in part, for many of the non–human-transmitted cases of leprosy.2,10 We encourage clinicians to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for leprosy when evaluating patients presenting with hypoesthetic cutaneous lesions and to obtain a travel history and to ask about armadillo exposure.

This case and the photos were submitted by Ms. Smith, from the University of South Florida, Tampa; Dr. Hatch and Dr. Sarriera-Lazaro, from the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of South Florida; and Dr. Turner and Dr. Beachkofsky, from the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, Tampa. Dr. Bilu Martin edited this case. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease), in: “Goldman’s Cecil Medicine,” 24th ed. (Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2012: pp. 1950-4.

2. Sharma R et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2127-34.

3. Lane JE et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):714-6.

4. Clark BM et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Jun;78(6):962-7.

5. Bruce S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Aug;43(2 Pt 1):223-8.

6. Loughry WJ et al. J Wildl Dis. 2009 Jan;45(1):144-52.

7. FDo H. Florida charts: Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy). Health FDo. 2019. https://www.flhealthcharts.gov/ChartsReports/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=NonVitalIndNoGrpCounts.DataViewer&cid=174.

8. Maymone MBC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul;83(1):1-14.

9. Scollard DM et al. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006 Apr;19(2):338-81.

10. Domozych R et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2016 May 12;2(3):189-92.

A 44-year-old White male presented with a 1½-year history of a progressive hypoesthetic annular, mildly hyperpigmented plaque on the left posterior upper arm.

He denied pruritus, pain, or systemic symptoms including weight loss, visual changes, cough, dyspnea, and abdominal pain. He also denied any paresthesia or weakness. On physical examination, there is a subtle, solitary 4-cm annular skin-colored thin plaque on the patient's left posterior upper arm (Figure 1).

Punch biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the histopathological findings are illustrated in Figure 2.

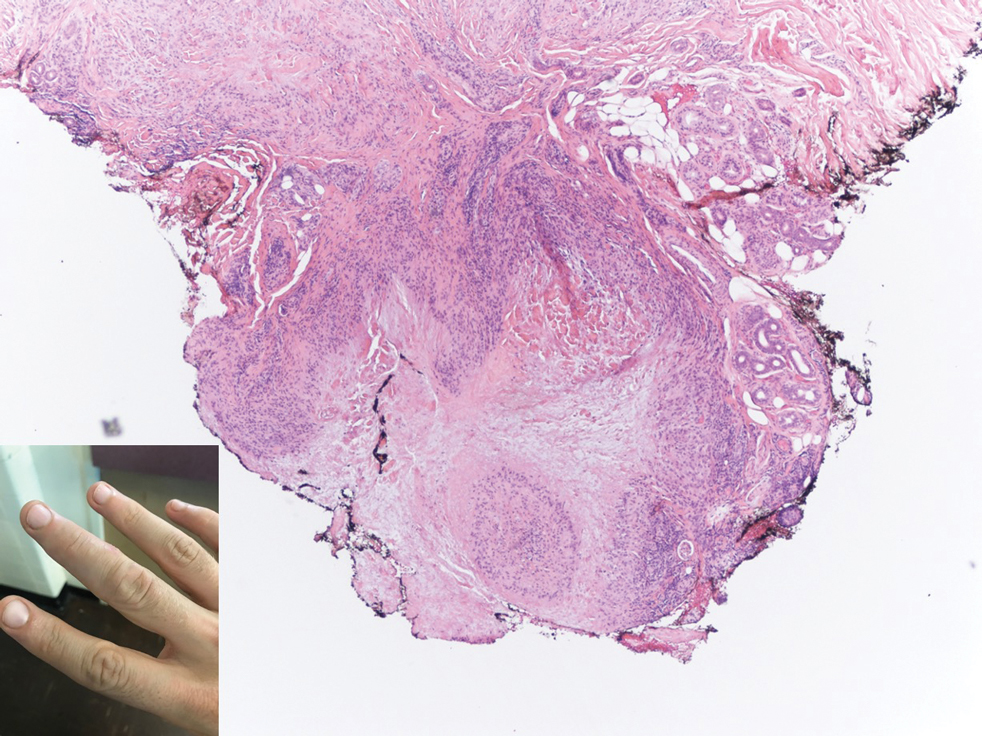

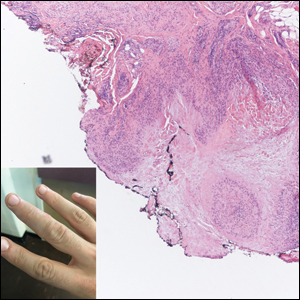

Multiple Nontender Subcutaneous Nodules on the Finger

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

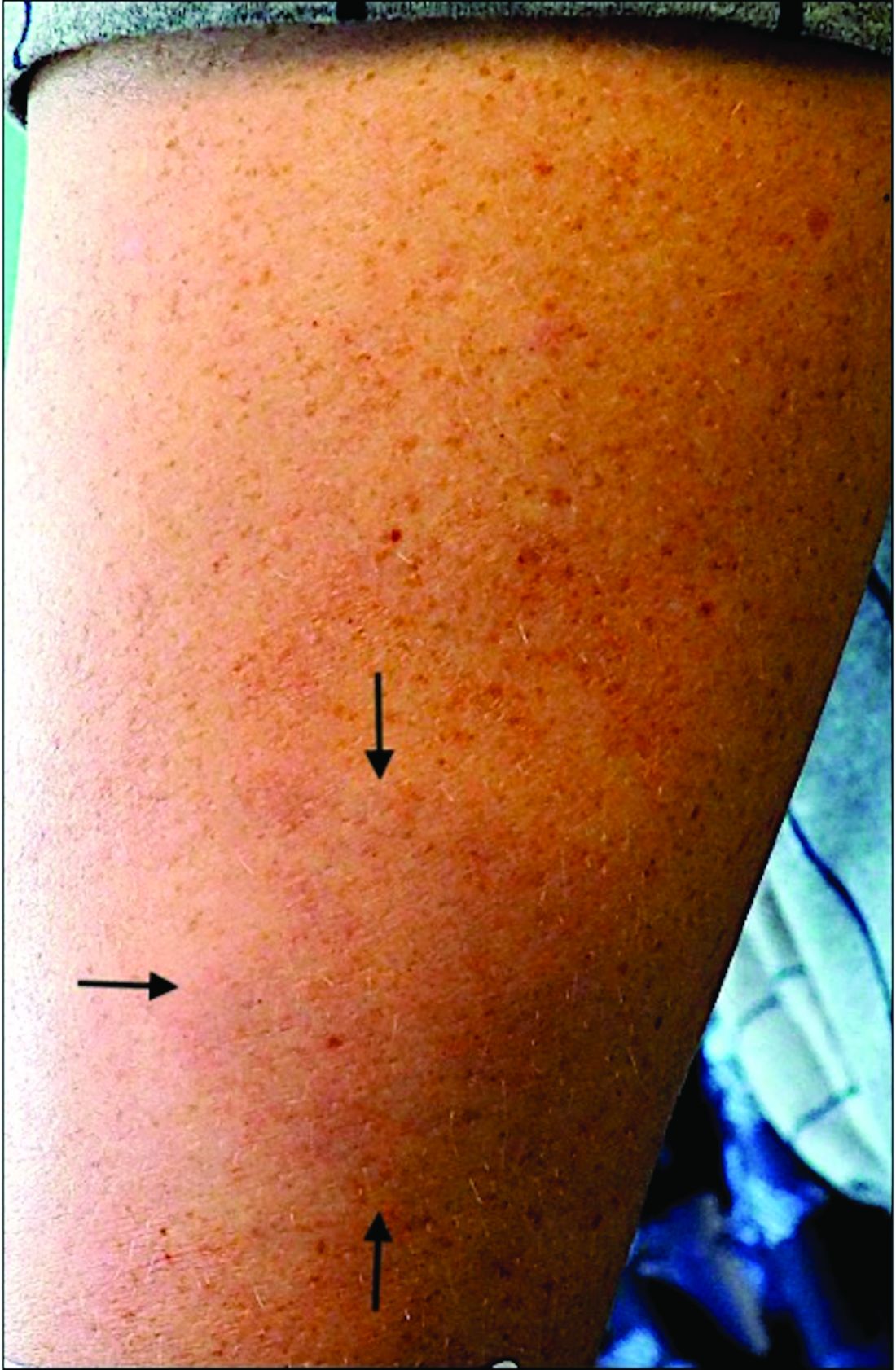

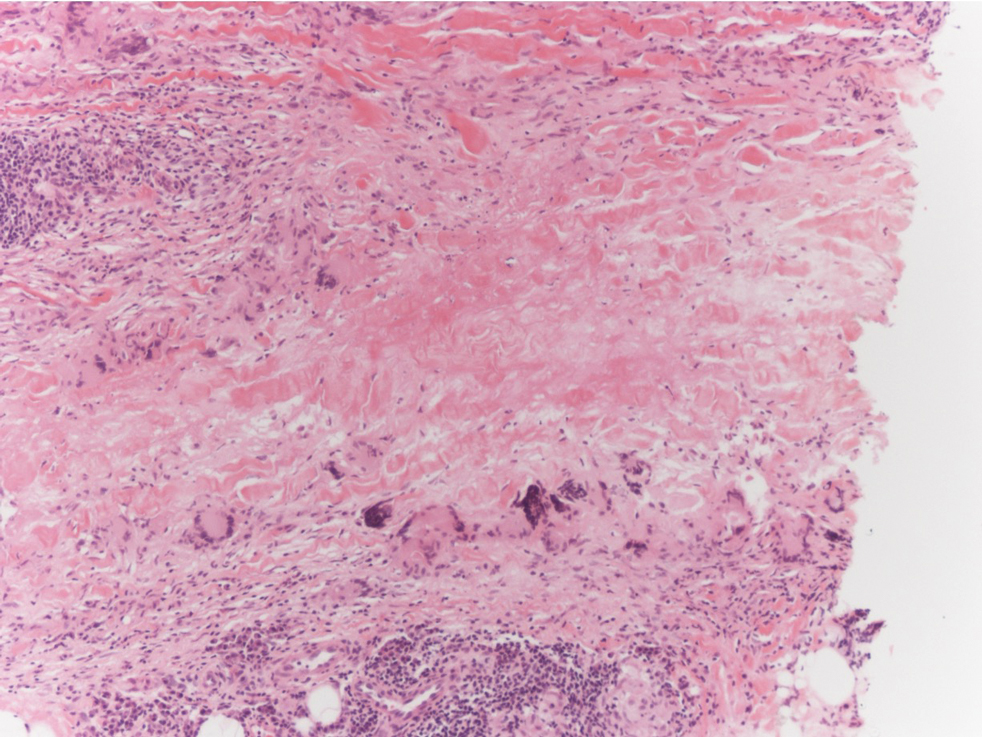

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

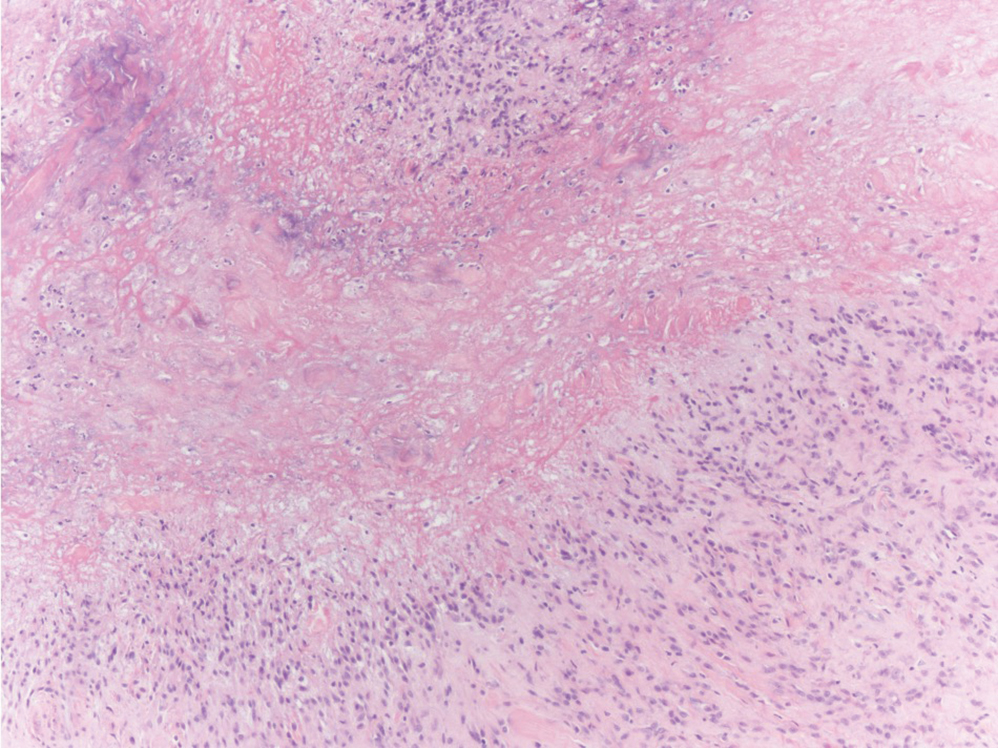

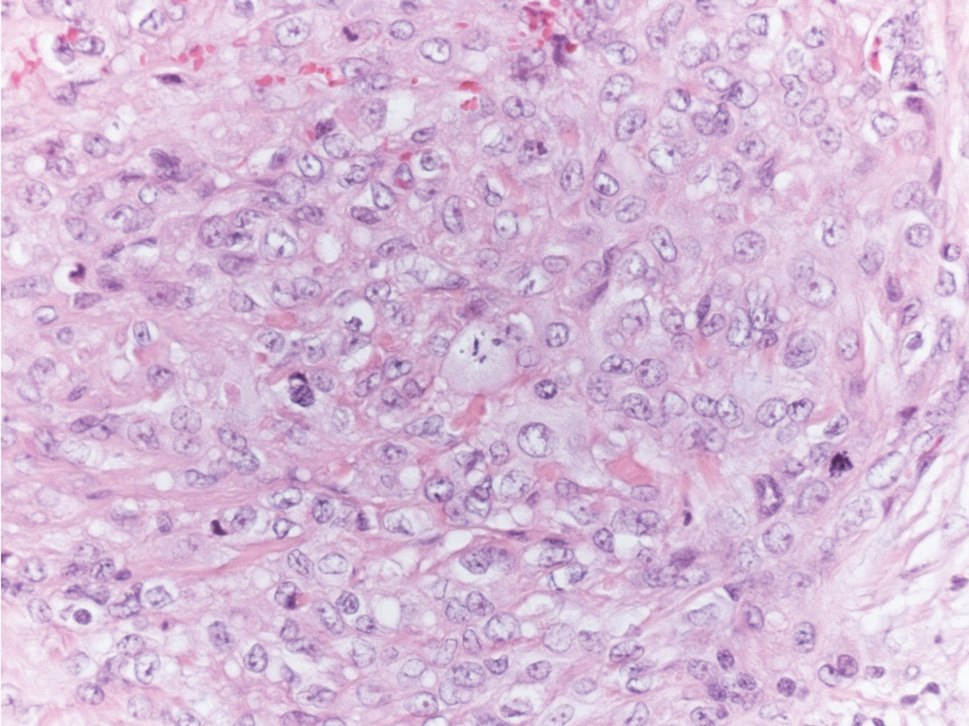

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

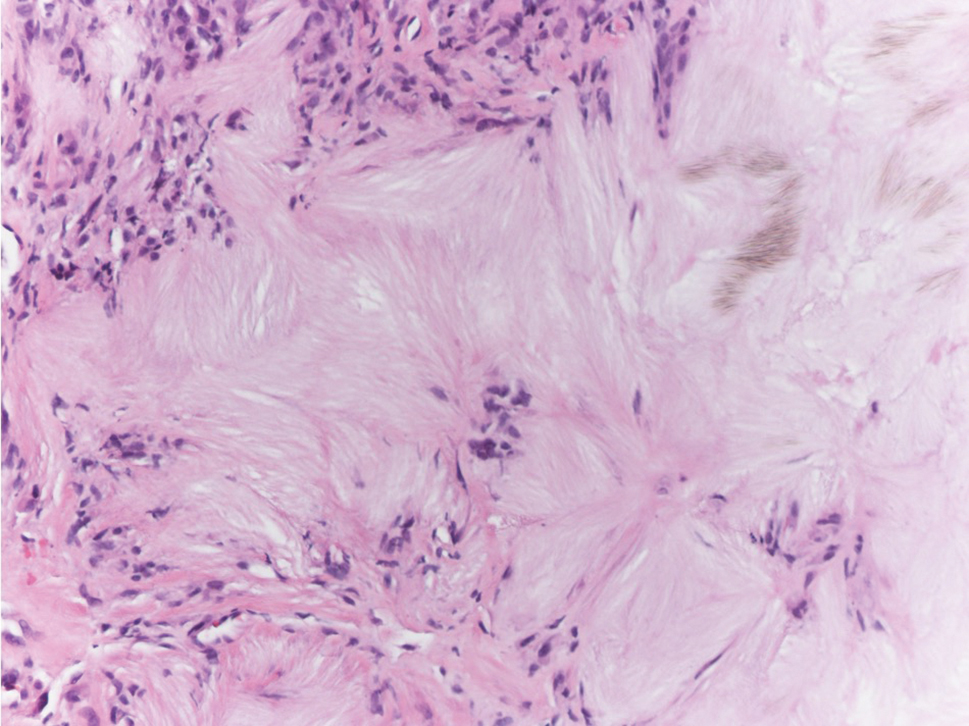

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.