User login

A Case Series of Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis With Mechanical Thrombectomy for Treating Severe Deep Vein Thrombosis

Two cases of extensive symptomatic deep vein thrombosis without phlegmasia cerulea dolens were successfully treated with an endovascular technique that combines catheter-directed thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a frequently encountered medical condition with about 1 in 1,000 adults diagnosed annually.1,2 Up to one-half of patients who receive a diagnosis will experience long-term complications in the affected limb.1 Anticoagulation is the treatment of choice for DVT in the absence of any contraindications.3 Thrombolytic therapies (eg, systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis with or without thrombectomy) historically have been reserved for patients who present with phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD), a severe condition involving venous obstruction within the extremities that causes impaired arterial blood supply and cyanosis that can lead to limb loss and death.4

The role of thrombolytic therapy is less clear in patients without PCD who present with extensive or symptomatic lower extremity DVT that causes significant pain, edema, and functional disability. Proximal lower extremity DVT (thrombus above the knee and above the popliteal vein) and particularly those involving the iliac or common femoral vein (ie, iliofemoral DVT) carry a significant risk of recurrent thromboembolism as well as postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), a complication of DVT resulting in chronic leg pain, edema, skin discoloration, and venous ulcers.5

The goal of thrombolytic therapy is to prevent thrombus propagation, recurrent thromboembolism, and PTS, in addition to providing more rapid pain relief and improvement in limb function.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis can be combined with catheter-directed thrombectomy using the same endovascular technique. This combination is called a pharmacomechanical thrombectomy or a pharmacomechanical thromobolysis and can offer more rapid removal of thrombus and decreased infusion times of thrombolytic drug.8 Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis is a relatively new technique, so the choice of thrombolytic therapy will depend on procedural expertise and resource availability. Early interventional radiology consultation (or vascular surgery in some centers) can assist in determining appropriate candidates for thrombolytic therapies. Here we present 2 cases of extensive symptomatic DVT successfully treated with catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Case 1

A 61-year-old male current smoker with a history of obesity and hypertension presented to the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) with 2 days of progressive pain and swelling in the right lower extremity (RLE) after sustaining a calf injury the preceding week. The patient rated pain as 9 on a 10-point scale and reported no other symptoms. He reported no prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs and normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive RLE edema below the knee with tenderness to palpation and shiny taut skin. The neurovascular examination of the RLE was normal. Laboratory studies were notable only for a mild leukocytosis. Compression ultrasound with Doppler of the RLE demonstrated an acute thrombus of the right femoral vein extending to the popliteal vein.

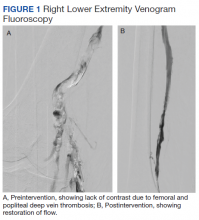

The patient was prescribed enoxaparin 90 mg every 12 hours for anticoagulation. After 36 hours of anticoagulation, he continued to experience severe RLE pain and swelling limiting ambulation. Interventional radiology was consulted, and catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis of the RLE was pursued given the persistence of significant symptoms. Intraprocedure venogram demonstrated thrombi filling the entirety of the right femoral and popliteal veins (Figure 1A). This was treated with catheter-directed pulse-spray thrombolysis with 12 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

After a 20-minute incubation period, a thrombectomy was performed several times along the femoral vein and popliteal vein, using an AngioJet device. A follow-up venogram revealed a small amount of residual thrombi in the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein. This entire segment was further treated with angioplasty, and a postintervention venogram demonstrated patency of the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein with minimal residual thrombi and with brisk venous flow (Figure 1B). Immediately after the procedure, the patient’s RLE pain significantly improved. On day 2 postprocedure, the patient’s RLE edema resolved, and the patient was able to resume normal ambulation. There were no bleeding complications. The patient was discharged with oral anticoagulation therapy.

Case 2

A male aged 78 years with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy presented to the ED with 10 days of progressive pain and swelling in the left lower extremity (LLE). The patient noted decreased mobility over recent months and was using a front wheel walker while recovering from surgical repair of a hamstring tendon injury. He reported taking a transcontinental flight around the same time that his LLE pain began. The patient reported no prior history of VTE or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs with a normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive LLE edema up to the proximal thigh without erythema or cyanosis, and his skin was taut and tender. Neurovascular examination of the LLE was normal. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Compression ultrasonography with Doppler of the LLE demonstrated an extensive acute occlusive thrombus within the left common femoral, entire left femoral, and left popliteal veins.

After evaluating the patient, the Vascular Surgery service did not feel there was evidence of compartment syndrome nor PCD. The patient received unfractionated heparin anticoagulation therapy and the LLE was elevated continuously. After 24 hours of anticoagulation therapy, the patient continued to have significant pain and was unable to ambulate. The case was presented in a joint Interventional Radiology/Vascular Surgery conference and the decision was made to pursue pharmacomechanic thrombolysis given the significant extent of thrombotic burden.

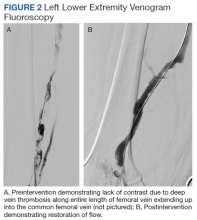

The patient underwent successful catheter-directed pharmacomechanic thrombolysis via pulse-spray thrombolysis of 15 mg of tPA using the Boston Scientific AngioJet Thrombectomy System, and angioplasty with no immediate complications (Figure 2). The patient noted dramatic improvement in LLE pain and swelling 1 day postprocedure and was able to ambulate. He developed mild asymptomatic hematuria, which resolved within 12 hours and without an associated drop in hemoglobin. The patient was transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit on postprocedure day 2.

Discussion

Anticoagulation is the preferred therapy for most patients with acute uncomplicated lower extremity DVT. PCD is the only widely accepted indication for thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute lower extremity DVT. However, in the absence of PCD, management of complicated DVT where there are either significant symptoms, extensive clot burden, or proximal location is less clear due to the paucity of clinical data. For example, in the case of iliofemoral DVT, thrombosis of the iliofemoral region is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, limb malperfusion, and PTS when compared with other types of DVT.5,6

Earlier retrospective observational studies in patients with acute DVT found that the addition of either systemic thrombolysis or catheter-directed thrombolysis to anticoagulation increased rates of clot lysis but did not lead to a reduction in clinical outcomes such as recurrent thromboembolism, mortality, or the rate of PTS.10-12 Additionally, both systemic thrombolytic therapy and catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy were associated with higher rates of major bleeding. However, these studies included all patients with acute DVT without selecting for criteria, such as proximal location of DVT, severe symptoms, or extensive clot burden. Because thrombolytic therapy is proven to provide more rapid and immediate clot lysis (whereas conventional anticoagulation prevents thrombus extension and recurrence but does not dissolve the clot), it is reasonable to suggest that a subpopulation of patients with extensive or symptomatic DVT may benefit from immediate clot lysis, thereby restoring limb perfusion and avoiding limb gangrene while preserving venous function and preventing PTS.

Mixed Study Results

The 2012 CaVenT study is one of the few randomized controlled trials to assess outcomes comparing conventional anticoagulation alone to anticoagulation with catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute lower extremity DVT.13 Study patients did not undergo catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy. Patients in this study consisted solely of those with first-time iliofemoral DVT. Long-term outcomes at 24-month follow-up showed that additional catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of PTS when compared with those who were treated with anticoagulation alone (41.1% vs 55.6%, P = .047). The difference in PTS corresponded to an absolute risk reduction of 14.4% (95% CI, 0.2-27.9), and the number needed to treat was 7 (95% CI, 4-502). There was a clinically relevant bleeding complication rate of 8.9% in the thrombolysis group with none leading to a permanently impaired outcome.

These results could not be confirmed by a more recent randomized control trial in 2017 conducted by Vedantham and colleagues.14 In this trial, patients with acute proximal DVT (femoral and iliofemoral DVT) were randomized to receive either anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis. In the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group, the overall incidence of PTS and recurrent VTE was not reduced over the 24-month follow-up period. Those who developed PTS in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group had lower severity scores, as there was a significant reduction in moderate-to-severe PTS in this group. There also were more early major bleeds in the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group (1.7%, with no fatal or intracranial bleeds) when compared with the control group; however, this bleeding complication rate was much less than what was noted in the CaVenT study. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in both lower extremity pain and edema in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group at 10 days and 30 days postintervention.

Given the mixed results of these 2 randomized controlled trials, further studies are warranted to clarify the role of thrombolytic therapies in preventing major events such as recurrent VTE and PTS, especially given the increased risk of bleeding observed with thrombolytic therapies. The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend anticoagulation as monotherapy vs thrombolytics, systemic or catheter-directed thrombolysis as designated treatment modalities.3 These guidelines are rated “Grade 2C”, which reflect a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. While these recommendations do not comment on additional considerations, such as DVT clot burden, location, or severity of symptoms, the guidelines do state that patients who attach a high value to the prevention of PTS and a lower value to the risk of bleeding with catheter-directed therapy are likely to choose catheter-directed therapy over anticoagulation alone.

Case Studies Analyses

In our first case presentation, pharma-comechanic thrombolysis was pursued because the patient presented with severesymptoms and did not experience any symptomatic improvement after 36 hours of anticoagulation. It is unclear whether a longer duration of anticoagulation might have improved the severity of his symptoms. When considering the level of pain, edema, and inability to ambulate, thrombolytic therapy was considered the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was successful, resulting in complete clot lysis, significant decrease in pain and edema with total recovery of ambulatory abilities, no bleeding complications, and prevention of any potential clinical deterioration, such as phlegmasia cerulea dolens. The patient is now 12 months postprocedure without symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events. Continued follow-up that monitors the development of PTS will be necessary for at least 2 years postprocedure.

In the second case, our patient experienced some improvement in pain after 24 hours of anticoagulation alone. However, considering the extensive proximal clot burden involving the entire femoral and common femoral veins, the treatment teams believed it was likely that this patient would experience a prolonged recovery time and increased morbidity on anticoagulant therapy alone. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was again successful with almost immediate resolution of pain and edema, and recovery of ambulatory abilities on postprocedure day 1. The patient is now 6 months postprocedure without any symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events.

In both case presentations, the presenting symptoms, methods of treatment, and immediate symptomatic improvement postintervention were similar. The patient in Case 2 had more extensive clot burden, a more proximal location of clot, and was classified as having an iliofemoral DVT because the thrombus included the common femoral vein; the decision for intervention in this case was more weighted on clot burden and location rather than on the significant symptoms of severe pain and difficulty with ambulation seen in Case 1. However, it is noteworthy that in Case 2 our patient also experienced significant improvement in pain, swelling, and ambulation postintervention. Complications were minimal and limited to Case 2 where our patient experienced mild asymptomatic hematuria likely related to the catheter-directed tPA that resolved spontaneously within hours and did not cause further complications. Additionally, it is likely that the length of hospital stay was decreased significantly in both cases given the rapid improvement in symptoms and recovery of ambulatory abilities.

High-Risk Patients

Given the successful treatment results in these 2 cases, we believe that there is a subset of higher-risk patients with severe symptomatic proximal DVT but without PCD that may benefit from the addition of thrombolytic therapies to anticoagulation. These patients may present with significant pain, difficulty ambulating, and will likely have extensive proximal clot burden. Immediate thrombolytic intervention can achieve rapid symptom relief, which, in turn, can decrease morbidity by decreasing length of hospitalization, improving ambulation, and possibly decreasing the incidence or severity of future PTS. Positive outcomes may be easier to predict for those with obvious features of pain, edema, and difficulty ambulating, which may be more readily reversed by rapid clot reversal/removal.

These patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, the severity of pain can be balanced against the patient’s risk factors for bleeding because rapid thrombus lysis or immediate thrombus removal will likely reduce the pain. Patients who attach a high value to functional quality (eg, both patients in this case study experienced significant difficulty ambulating), quicker recovery, and decreased hospitalization duration may be more likely to choose the addition of thrombolytic therapies over anticoagulation alone and accept the higher risk of bleed.

Finally, additional studies involving variations in methodology should be examined, including whether pharmacomechanic thrombolysis may be safer in terms of bleeding than catheter-directed thrombolysis alone, as suggested by the lower bleeding rates seen in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedantham and colleagues when compared with the CaVenT study.13,14 Patients in the CaVenT study received an infusion of 20 mg of alteplase over a maximum of 96 hours. Patients in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedanthem and colleagues received either a rapid pulsed delivery of alteplase over a single procedural session (

Conclusions

There is a relative lack of high-quality data examining thrombolytic therapies in the setting of acute lower extremity DVT. Recent studies have prioritized evaluation of the posttreatment incidence of PTS, recurrent thromboembolism, and risk of bleeding caused by thrombolytic therapies. Results are mixed thus far, and further studies are necessary to clarify a more definitive role for thrombolytic therapies, particularly in established higher-risk populations with proximal DVT. In this case series, we highlighted 2 patients with extensive proximal DVT burden with significant symptoms who experienced almost complete resolution of symptoms immediately following thrombolytic therapies. We postulate that even in the absence of PCD, there is a subset of patients with severe symptoms in the setting of acute proximal lower extremity DVT that clearly benefit from thrombolytic therapies.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/data.html

2. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4-I8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report [published correction appears in Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988]. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

4. Sarwar S, Narra S, Munir A. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(1):76-77.

5. Nyamekye I, Merker L. Management of proximal deep vein thrombosis. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 2:61-72. doi:10.1258/phleb.2012.012s37

6. Abhishek M, Sukriti K, Purav S, et al. Comparison of catheter-directed thrombolysis vs systemic thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism: a propensity match analysis. Chest. 2017;152(4): A1047. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.1080

7. Sista AK, Kearon C. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism: where do we stand? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1393-1395. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.009

8. Robertson L, McBride O, Burdess A. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011536. Published 2016 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011536.pub2

9. Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1105-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 Dec;142(6):1698-1704]. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2301

11. Bashir R, Zack CJ, Zhao H, Comerota AJ, Bove AA. Comparative outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone to treat lower-extremity proximal deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1494-1501. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3415

12. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD002783. Published 2016 Nov 10. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002783.pub4

13. Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31-38. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4

14. Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Julian JA, et al; ATTRACT Trial Investigators. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2240-2252. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615066

Two cases of extensive symptomatic deep vein thrombosis without phlegmasia cerulea dolens were successfully treated with an endovascular technique that combines catheter-directed thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy.

Two cases of extensive symptomatic deep vein thrombosis without phlegmasia cerulea dolens were successfully treated with an endovascular technique that combines catheter-directed thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a frequently encountered medical condition with about 1 in 1,000 adults diagnosed annually.1,2 Up to one-half of patients who receive a diagnosis will experience long-term complications in the affected limb.1 Anticoagulation is the treatment of choice for DVT in the absence of any contraindications.3 Thrombolytic therapies (eg, systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis with or without thrombectomy) historically have been reserved for patients who present with phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD), a severe condition involving venous obstruction within the extremities that causes impaired arterial blood supply and cyanosis that can lead to limb loss and death.4

The role of thrombolytic therapy is less clear in patients without PCD who present with extensive or symptomatic lower extremity DVT that causes significant pain, edema, and functional disability. Proximal lower extremity DVT (thrombus above the knee and above the popliteal vein) and particularly those involving the iliac or common femoral vein (ie, iliofemoral DVT) carry a significant risk of recurrent thromboembolism as well as postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), a complication of DVT resulting in chronic leg pain, edema, skin discoloration, and venous ulcers.5

The goal of thrombolytic therapy is to prevent thrombus propagation, recurrent thromboembolism, and PTS, in addition to providing more rapid pain relief and improvement in limb function.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis can be combined with catheter-directed thrombectomy using the same endovascular technique. This combination is called a pharmacomechanical thrombectomy or a pharmacomechanical thromobolysis and can offer more rapid removal of thrombus and decreased infusion times of thrombolytic drug.8 Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis is a relatively new technique, so the choice of thrombolytic therapy will depend on procedural expertise and resource availability. Early interventional radiology consultation (or vascular surgery in some centers) can assist in determining appropriate candidates for thrombolytic therapies. Here we present 2 cases of extensive symptomatic DVT successfully treated with catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Case 1

A 61-year-old male current smoker with a history of obesity and hypertension presented to the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) with 2 days of progressive pain and swelling in the right lower extremity (RLE) after sustaining a calf injury the preceding week. The patient rated pain as 9 on a 10-point scale and reported no other symptoms. He reported no prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs and normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive RLE edema below the knee with tenderness to palpation and shiny taut skin. The neurovascular examination of the RLE was normal. Laboratory studies were notable only for a mild leukocytosis. Compression ultrasound with Doppler of the RLE demonstrated an acute thrombus of the right femoral vein extending to the popliteal vein.

The patient was prescribed enoxaparin 90 mg every 12 hours for anticoagulation. After 36 hours of anticoagulation, he continued to experience severe RLE pain and swelling limiting ambulation. Interventional radiology was consulted, and catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis of the RLE was pursued given the persistence of significant symptoms. Intraprocedure venogram demonstrated thrombi filling the entirety of the right femoral and popliteal veins (Figure 1A). This was treated with catheter-directed pulse-spray thrombolysis with 12 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

After a 20-minute incubation period, a thrombectomy was performed several times along the femoral vein and popliteal vein, using an AngioJet device. A follow-up venogram revealed a small amount of residual thrombi in the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein. This entire segment was further treated with angioplasty, and a postintervention venogram demonstrated patency of the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein with minimal residual thrombi and with brisk venous flow (Figure 1B). Immediately after the procedure, the patient’s RLE pain significantly improved. On day 2 postprocedure, the patient’s RLE edema resolved, and the patient was able to resume normal ambulation. There were no bleeding complications. The patient was discharged with oral anticoagulation therapy.

Case 2

A male aged 78 years with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy presented to the ED with 10 days of progressive pain and swelling in the left lower extremity (LLE). The patient noted decreased mobility over recent months and was using a front wheel walker while recovering from surgical repair of a hamstring tendon injury. He reported taking a transcontinental flight around the same time that his LLE pain began. The patient reported no prior history of VTE or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs with a normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive LLE edema up to the proximal thigh without erythema or cyanosis, and his skin was taut and tender. Neurovascular examination of the LLE was normal. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Compression ultrasonography with Doppler of the LLE demonstrated an extensive acute occlusive thrombus within the left common femoral, entire left femoral, and left popliteal veins.

After evaluating the patient, the Vascular Surgery service did not feel there was evidence of compartment syndrome nor PCD. The patient received unfractionated heparin anticoagulation therapy and the LLE was elevated continuously. After 24 hours of anticoagulation therapy, the patient continued to have significant pain and was unable to ambulate. The case was presented in a joint Interventional Radiology/Vascular Surgery conference and the decision was made to pursue pharmacomechanic thrombolysis given the significant extent of thrombotic burden.

The patient underwent successful catheter-directed pharmacomechanic thrombolysis via pulse-spray thrombolysis of 15 mg of tPA using the Boston Scientific AngioJet Thrombectomy System, and angioplasty with no immediate complications (Figure 2). The patient noted dramatic improvement in LLE pain and swelling 1 day postprocedure and was able to ambulate. He developed mild asymptomatic hematuria, which resolved within 12 hours and without an associated drop in hemoglobin. The patient was transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit on postprocedure day 2.

Discussion

Anticoagulation is the preferred therapy for most patients with acute uncomplicated lower extremity DVT. PCD is the only widely accepted indication for thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute lower extremity DVT. However, in the absence of PCD, management of complicated DVT where there are either significant symptoms, extensive clot burden, or proximal location is less clear due to the paucity of clinical data. For example, in the case of iliofemoral DVT, thrombosis of the iliofemoral region is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, limb malperfusion, and PTS when compared with other types of DVT.5,6

Earlier retrospective observational studies in patients with acute DVT found that the addition of either systemic thrombolysis or catheter-directed thrombolysis to anticoagulation increased rates of clot lysis but did not lead to a reduction in clinical outcomes such as recurrent thromboembolism, mortality, or the rate of PTS.10-12 Additionally, both systemic thrombolytic therapy and catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy were associated with higher rates of major bleeding. However, these studies included all patients with acute DVT without selecting for criteria, such as proximal location of DVT, severe symptoms, or extensive clot burden. Because thrombolytic therapy is proven to provide more rapid and immediate clot lysis (whereas conventional anticoagulation prevents thrombus extension and recurrence but does not dissolve the clot), it is reasonable to suggest that a subpopulation of patients with extensive or symptomatic DVT may benefit from immediate clot lysis, thereby restoring limb perfusion and avoiding limb gangrene while preserving venous function and preventing PTS.

Mixed Study Results

The 2012 CaVenT study is one of the few randomized controlled trials to assess outcomes comparing conventional anticoagulation alone to anticoagulation with catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute lower extremity DVT.13 Study patients did not undergo catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy. Patients in this study consisted solely of those with first-time iliofemoral DVT. Long-term outcomes at 24-month follow-up showed that additional catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of PTS when compared with those who were treated with anticoagulation alone (41.1% vs 55.6%, P = .047). The difference in PTS corresponded to an absolute risk reduction of 14.4% (95% CI, 0.2-27.9), and the number needed to treat was 7 (95% CI, 4-502). There was a clinically relevant bleeding complication rate of 8.9% in the thrombolysis group with none leading to a permanently impaired outcome.

These results could not be confirmed by a more recent randomized control trial in 2017 conducted by Vedantham and colleagues.14 In this trial, patients with acute proximal DVT (femoral and iliofemoral DVT) were randomized to receive either anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis. In the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group, the overall incidence of PTS and recurrent VTE was not reduced over the 24-month follow-up period. Those who developed PTS in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group had lower severity scores, as there was a significant reduction in moderate-to-severe PTS in this group. There also were more early major bleeds in the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group (1.7%, with no fatal or intracranial bleeds) when compared with the control group; however, this bleeding complication rate was much less than what was noted in the CaVenT study. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in both lower extremity pain and edema in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group at 10 days and 30 days postintervention.

Given the mixed results of these 2 randomized controlled trials, further studies are warranted to clarify the role of thrombolytic therapies in preventing major events such as recurrent VTE and PTS, especially given the increased risk of bleeding observed with thrombolytic therapies. The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend anticoagulation as monotherapy vs thrombolytics, systemic or catheter-directed thrombolysis as designated treatment modalities.3 These guidelines are rated “Grade 2C”, which reflect a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. While these recommendations do not comment on additional considerations, such as DVT clot burden, location, or severity of symptoms, the guidelines do state that patients who attach a high value to the prevention of PTS and a lower value to the risk of bleeding with catheter-directed therapy are likely to choose catheter-directed therapy over anticoagulation alone.

Case Studies Analyses

In our first case presentation, pharma-comechanic thrombolysis was pursued because the patient presented with severesymptoms and did not experience any symptomatic improvement after 36 hours of anticoagulation. It is unclear whether a longer duration of anticoagulation might have improved the severity of his symptoms. When considering the level of pain, edema, and inability to ambulate, thrombolytic therapy was considered the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was successful, resulting in complete clot lysis, significant decrease in pain and edema with total recovery of ambulatory abilities, no bleeding complications, and prevention of any potential clinical deterioration, such as phlegmasia cerulea dolens. The patient is now 12 months postprocedure without symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events. Continued follow-up that monitors the development of PTS will be necessary for at least 2 years postprocedure.

In the second case, our patient experienced some improvement in pain after 24 hours of anticoagulation alone. However, considering the extensive proximal clot burden involving the entire femoral and common femoral veins, the treatment teams believed it was likely that this patient would experience a prolonged recovery time and increased morbidity on anticoagulant therapy alone. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was again successful with almost immediate resolution of pain and edema, and recovery of ambulatory abilities on postprocedure day 1. The patient is now 6 months postprocedure without any symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events.

In both case presentations, the presenting symptoms, methods of treatment, and immediate symptomatic improvement postintervention were similar. The patient in Case 2 had more extensive clot burden, a more proximal location of clot, and was classified as having an iliofemoral DVT because the thrombus included the common femoral vein; the decision for intervention in this case was more weighted on clot burden and location rather than on the significant symptoms of severe pain and difficulty with ambulation seen in Case 1. However, it is noteworthy that in Case 2 our patient also experienced significant improvement in pain, swelling, and ambulation postintervention. Complications were minimal and limited to Case 2 where our patient experienced mild asymptomatic hematuria likely related to the catheter-directed tPA that resolved spontaneously within hours and did not cause further complications. Additionally, it is likely that the length of hospital stay was decreased significantly in both cases given the rapid improvement in symptoms and recovery of ambulatory abilities.

High-Risk Patients

Given the successful treatment results in these 2 cases, we believe that there is a subset of higher-risk patients with severe symptomatic proximal DVT but without PCD that may benefit from the addition of thrombolytic therapies to anticoagulation. These patients may present with significant pain, difficulty ambulating, and will likely have extensive proximal clot burden. Immediate thrombolytic intervention can achieve rapid symptom relief, which, in turn, can decrease morbidity by decreasing length of hospitalization, improving ambulation, and possibly decreasing the incidence or severity of future PTS. Positive outcomes may be easier to predict for those with obvious features of pain, edema, and difficulty ambulating, which may be more readily reversed by rapid clot reversal/removal.

These patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, the severity of pain can be balanced against the patient’s risk factors for bleeding because rapid thrombus lysis or immediate thrombus removal will likely reduce the pain. Patients who attach a high value to functional quality (eg, both patients in this case study experienced significant difficulty ambulating), quicker recovery, and decreased hospitalization duration may be more likely to choose the addition of thrombolytic therapies over anticoagulation alone and accept the higher risk of bleed.

Finally, additional studies involving variations in methodology should be examined, including whether pharmacomechanic thrombolysis may be safer in terms of bleeding than catheter-directed thrombolysis alone, as suggested by the lower bleeding rates seen in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedantham and colleagues when compared with the CaVenT study.13,14 Patients in the CaVenT study received an infusion of 20 mg of alteplase over a maximum of 96 hours. Patients in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedanthem and colleagues received either a rapid pulsed delivery of alteplase over a single procedural session (

Conclusions

There is a relative lack of high-quality data examining thrombolytic therapies in the setting of acute lower extremity DVT. Recent studies have prioritized evaluation of the posttreatment incidence of PTS, recurrent thromboembolism, and risk of bleeding caused by thrombolytic therapies. Results are mixed thus far, and further studies are necessary to clarify a more definitive role for thrombolytic therapies, particularly in established higher-risk populations with proximal DVT. In this case series, we highlighted 2 patients with extensive proximal DVT burden with significant symptoms who experienced almost complete resolution of symptoms immediately following thrombolytic therapies. We postulate that even in the absence of PCD, there is a subset of patients with severe symptoms in the setting of acute proximal lower extremity DVT that clearly benefit from thrombolytic therapies.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a frequently encountered medical condition with about 1 in 1,000 adults diagnosed annually.1,2 Up to one-half of patients who receive a diagnosis will experience long-term complications in the affected limb.1 Anticoagulation is the treatment of choice for DVT in the absence of any contraindications.3 Thrombolytic therapies (eg, systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis with or without thrombectomy) historically have been reserved for patients who present with phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD), a severe condition involving venous obstruction within the extremities that causes impaired arterial blood supply and cyanosis that can lead to limb loss and death.4

The role of thrombolytic therapy is less clear in patients without PCD who present with extensive or symptomatic lower extremity DVT that causes significant pain, edema, and functional disability. Proximal lower extremity DVT (thrombus above the knee and above the popliteal vein) and particularly those involving the iliac or common femoral vein (ie, iliofemoral DVT) carry a significant risk of recurrent thromboembolism as well as postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), a complication of DVT resulting in chronic leg pain, edema, skin discoloration, and venous ulcers.5

The goal of thrombolytic therapy is to prevent thrombus propagation, recurrent thromboembolism, and PTS, in addition to providing more rapid pain relief and improvement in limb function.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis can be combined with catheter-directed thrombectomy using the same endovascular technique. This combination is called a pharmacomechanical thrombectomy or a pharmacomechanical thromobolysis and can offer more rapid removal of thrombus and decreased infusion times of thrombolytic drug.8 Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis is a relatively new technique, so the choice of thrombolytic therapy will depend on procedural expertise and resource availability. Early interventional radiology consultation (or vascular surgery in some centers) can assist in determining appropriate candidates for thrombolytic therapies. Here we present 2 cases of extensive symptomatic DVT successfully treated with catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Case 1

A 61-year-old male current smoker with a history of obesity and hypertension presented to the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) with 2 days of progressive pain and swelling in the right lower extremity (RLE) after sustaining a calf injury the preceding week. The patient rated pain as 9 on a 10-point scale and reported no other symptoms. He reported no prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs and normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive RLE edema below the knee with tenderness to palpation and shiny taut skin. The neurovascular examination of the RLE was normal. Laboratory studies were notable only for a mild leukocytosis. Compression ultrasound with Doppler of the RLE demonstrated an acute thrombus of the right femoral vein extending to the popliteal vein.

The patient was prescribed enoxaparin 90 mg every 12 hours for anticoagulation. After 36 hours of anticoagulation, he continued to experience severe RLE pain and swelling limiting ambulation. Interventional radiology was consulted, and catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis of the RLE was pursued given the persistence of significant symptoms. Intraprocedure venogram demonstrated thrombi filling the entirety of the right femoral and popliteal veins (Figure 1A). This was treated with catheter-directed pulse-spray thrombolysis with 12 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

After a 20-minute incubation period, a thrombectomy was performed several times along the femoral vein and popliteal vein, using an AngioJet device. A follow-up venogram revealed a small amount of residual thrombi in the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein. This entire segment was further treated with angioplasty, and a postintervention venogram demonstrated patency of the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein with minimal residual thrombi and with brisk venous flow (Figure 1B). Immediately after the procedure, the patient’s RLE pain significantly improved. On day 2 postprocedure, the patient’s RLE edema resolved, and the patient was able to resume normal ambulation. There were no bleeding complications. The patient was discharged with oral anticoagulation therapy.

Case 2

A male aged 78 years with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy presented to the ED with 10 days of progressive pain and swelling in the left lower extremity (LLE). The patient noted decreased mobility over recent months and was using a front wheel walker while recovering from surgical repair of a hamstring tendon injury. He reported taking a transcontinental flight around the same time that his LLE pain began. The patient reported no prior history of VTE or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs with a normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive LLE edema up to the proximal thigh without erythema or cyanosis, and his skin was taut and tender. Neurovascular examination of the LLE was normal. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Compression ultrasonography with Doppler of the LLE demonstrated an extensive acute occlusive thrombus within the left common femoral, entire left femoral, and left popliteal veins.

After evaluating the patient, the Vascular Surgery service did not feel there was evidence of compartment syndrome nor PCD. The patient received unfractionated heparin anticoagulation therapy and the LLE was elevated continuously. After 24 hours of anticoagulation therapy, the patient continued to have significant pain and was unable to ambulate. The case was presented in a joint Interventional Radiology/Vascular Surgery conference and the decision was made to pursue pharmacomechanic thrombolysis given the significant extent of thrombotic burden.

The patient underwent successful catheter-directed pharmacomechanic thrombolysis via pulse-spray thrombolysis of 15 mg of tPA using the Boston Scientific AngioJet Thrombectomy System, and angioplasty with no immediate complications (Figure 2). The patient noted dramatic improvement in LLE pain and swelling 1 day postprocedure and was able to ambulate. He developed mild asymptomatic hematuria, which resolved within 12 hours and without an associated drop in hemoglobin. The patient was transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit on postprocedure day 2.

Discussion

Anticoagulation is the preferred therapy for most patients with acute uncomplicated lower extremity DVT. PCD is the only widely accepted indication for thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute lower extremity DVT. However, in the absence of PCD, management of complicated DVT where there are either significant symptoms, extensive clot burden, or proximal location is less clear due to the paucity of clinical data. For example, in the case of iliofemoral DVT, thrombosis of the iliofemoral region is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, limb malperfusion, and PTS when compared with other types of DVT.5,6

Earlier retrospective observational studies in patients with acute DVT found that the addition of either systemic thrombolysis or catheter-directed thrombolysis to anticoagulation increased rates of clot lysis but did not lead to a reduction in clinical outcomes such as recurrent thromboembolism, mortality, or the rate of PTS.10-12 Additionally, both systemic thrombolytic therapy and catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy were associated with higher rates of major bleeding. However, these studies included all patients with acute DVT without selecting for criteria, such as proximal location of DVT, severe symptoms, or extensive clot burden. Because thrombolytic therapy is proven to provide more rapid and immediate clot lysis (whereas conventional anticoagulation prevents thrombus extension and recurrence but does not dissolve the clot), it is reasonable to suggest that a subpopulation of patients with extensive or symptomatic DVT may benefit from immediate clot lysis, thereby restoring limb perfusion and avoiding limb gangrene while preserving venous function and preventing PTS.

Mixed Study Results

The 2012 CaVenT study is one of the few randomized controlled trials to assess outcomes comparing conventional anticoagulation alone to anticoagulation with catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute lower extremity DVT.13 Study patients did not undergo catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy. Patients in this study consisted solely of those with first-time iliofemoral DVT. Long-term outcomes at 24-month follow-up showed that additional catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of PTS when compared with those who were treated with anticoagulation alone (41.1% vs 55.6%, P = .047). The difference in PTS corresponded to an absolute risk reduction of 14.4% (95% CI, 0.2-27.9), and the number needed to treat was 7 (95% CI, 4-502). There was a clinically relevant bleeding complication rate of 8.9% in the thrombolysis group with none leading to a permanently impaired outcome.

These results could not be confirmed by a more recent randomized control trial in 2017 conducted by Vedantham and colleagues.14 In this trial, patients with acute proximal DVT (femoral and iliofemoral DVT) were randomized to receive either anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis. In the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group, the overall incidence of PTS and recurrent VTE was not reduced over the 24-month follow-up period. Those who developed PTS in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group had lower severity scores, as there was a significant reduction in moderate-to-severe PTS in this group. There also were more early major bleeds in the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group (1.7%, with no fatal or intracranial bleeds) when compared with the control group; however, this bleeding complication rate was much less than what was noted in the CaVenT study. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in both lower extremity pain and edema in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group at 10 days and 30 days postintervention.

Given the mixed results of these 2 randomized controlled trials, further studies are warranted to clarify the role of thrombolytic therapies in preventing major events such as recurrent VTE and PTS, especially given the increased risk of bleeding observed with thrombolytic therapies. The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend anticoagulation as monotherapy vs thrombolytics, systemic or catheter-directed thrombolysis as designated treatment modalities.3 These guidelines are rated “Grade 2C”, which reflect a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. While these recommendations do not comment on additional considerations, such as DVT clot burden, location, or severity of symptoms, the guidelines do state that patients who attach a high value to the prevention of PTS and a lower value to the risk of bleeding with catheter-directed therapy are likely to choose catheter-directed therapy over anticoagulation alone.

Case Studies Analyses

In our first case presentation, pharma-comechanic thrombolysis was pursued because the patient presented with severesymptoms and did not experience any symptomatic improvement after 36 hours of anticoagulation. It is unclear whether a longer duration of anticoagulation might have improved the severity of his symptoms. When considering the level of pain, edema, and inability to ambulate, thrombolytic therapy was considered the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was successful, resulting in complete clot lysis, significant decrease in pain and edema with total recovery of ambulatory abilities, no bleeding complications, and prevention of any potential clinical deterioration, such as phlegmasia cerulea dolens. The patient is now 12 months postprocedure without symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events. Continued follow-up that monitors the development of PTS will be necessary for at least 2 years postprocedure.

In the second case, our patient experienced some improvement in pain after 24 hours of anticoagulation alone. However, considering the extensive proximal clot burden involving the entire femoral and common femoral veins, the treatment teams believed it was likely that this patient would experience a prolonged recovery time and increased morbidity on anticoagulant therapy alone. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was again successful with almost immediate resolution of pain and edema, and recovery of ambulatory abilities on postprocedure day 1. The patient is now 6 months postprocedure without any symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events.

In both case presentations, the presenting symptoms, methods of treatment, and immediate symptomatic improvement postintervention were similar. The patient in Case 2 had more extensive clot burden, a more proximal location of clot, and was classified as having an iliofemoral DVT because the thrombus included the common femoral vein; the decision for intervention in this case was more weighted on clot burden and location rather than on the significant symptoms of severe pain and difficulty with ambulation seen in Case 1. However, it is noteworthy that in Case 2 our patient also experienced significant improvement in pain, swelling, and ambulation postintervention. Complications were minimal and limited to Case 2 where our patient experienced mild asymptomatic hematuria likely related to the catheter-directed tPA that resolved spontaneously within hours and did not cause further complications. Additionally, it is likely that the length of hospital stay was decreased significantly in both cases given the rapid improvement in symptoms and recovery of ambulatory abilities.

High-Risk Patients

Given the successful treatment results in these 2 cases, we believe that there is a subset of higher-risk patients with severe symptomatic proximal DVT but without PCD that may benefit from the addition of thrombolytic therapies to anticoagulation. These patients may present with significant pain, difficulty ambulating, and will likely have extensive proximal clot burden. Immediate thrombolytic intervention can achieve rapid symptom relief, which, in turn, can decrease morbidity by decreasing length of hospitalization, improving ambulation, and possibly decreasing the incidence or severity of future PTS. Positive outcomes may be easier to predict for those with obvious features of pain, edema, and difficulty ambulating, which may be more readily reversed by rapid clot reversal/removal.

These patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, the severity of pain can be balanced against the patient’s risk factors for bleeding because rapid thrombus lysis or immediate thrombus removal will likely reduce the pain. Patients who attach a high value to functional quality (eg, both patients in this case study experienced significant difficulty ambulating), quicker recovery, and decreased hospitalization duration may be more likely to choose the addition of thrombolytic therapies over anticoagulation alone and accept the higher risk of bleed.

Finally, additional studies involving variations in methodology should be examined, including whether pharmacomechanic thrombolysis may be safer in terms of bleeding than catheter-directed thrombolysis alone, as suggested by the lower bleeding rates seen in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedantham and colleagues when compared with the CaVenT study.13,14 Patients in the CaVenT study received an infusion of 20 mg of alteplase over a maximum of 96 hours. Patients in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedanthem and colleagues received either a rapid pulsed delivery of alteplase over a single procedural session (

Conclusions

There is a relative lack of high-quality data examining thrombolytic therapies in the setting of acute lower extremity DVT. Recent studies have prioritized evaluation of the posttreatment incidence of PTS, recurrent thromboembolism, and risk of bleeding caused by thrombolytic therapies. Results are mixed thus far, and further studies are necessary to clarify a more definitive role for thrombolytic therapies, particularly in established higher-risk populations with proximal DVT. In this case series, we highlighted 2 patients with extensive proximal DVT burden with significant symptoms who experienced almost complete resolution of symptoms immediately following thrombolytic therapies. We postulate that even in the absence of PCD, there is a subset of patients with severe symptoms in the setting of acute proximal lower extremity DVT that clearly benefit from thrombolytic therapies.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/data.html

2. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4-I8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report [published correction appears in Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988]. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

4. Sarwar S, Narra S, Munir A. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(1):76-77.

5. Nyamekye I, Merker L. Management of proximal deep vein thrombosis. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 2:61-72. doi:10.1258/phleb.2012.012s37

6. Abhishek M, Sukriti K, Purav S, et al. Comparison of catheter-directed thrombolysis vs systemic thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism: a propensity match analysis. Chest. 2017;152(4): A1047. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.1080

7. Sista AK, Kearon C. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism: where do we stand? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1393-1395. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.009

8. Robertson L, McBride O, Burdess A. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011536. Published 2016 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011536.pub2

9. Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1105-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 Dec;142(6):1698-1704]. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2301

11. Bashir R, Zack CJ, Zhao H, Comerota AJ, Bove AA. Comparative outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone to treat lower-extremity proximal deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1494-1501. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3415

12. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD002783. Published 2016 Nov 10. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002783.pub4

13. Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31-38. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4

14. Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Julian JA, et al; ATTRACT Trial Investigators. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2240-2252. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615066

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/data.html

2. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4-I8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report [published correction appears in Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988]. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

4. Sarwar S, Narra S, Munir A. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(1):76-77.

5. Nyamekye I, Merker L. Management of proximal deep vein thrombosis. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 2:61-72. doi:10.1258/phleb.2012.012s37

6. Abhishek M, Sukriti K, Purav S, et al. Comparison of catheter-directed thrombolysis vs systemic thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism: a propensity match analysis. Chest. 2017;152(4): A1047. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.1080

7. Sista AK, Kearon C. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism: where do we stand? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1393-1395. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.009

8. Robertson L, McBride O, Burdess A. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011536. Published 2016 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011536.pub2

9. Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1105-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 Dec;142(6):1698-1704]. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2301

11. Bashir R, Zack CJ, Zhao H, Comerota AJ, Bove AA. Comparative outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone to treat lower-extremity proximal deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1494-1501. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3415

12. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD002783. Published 2016 Nov 10. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002783.pub4

13. Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31-38. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4

14. Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Julian JA, et al; ATTRACT Trial Investigators. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2240-2252. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615066

Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis in a Patient With Multiple Inflammatory Disorders

First described in 2000 in a case series of 15 patients, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare scleroderma-like fibrosing skin condition associated with gadolinium exposure in end stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ESRD are at the highest risk for this condition when exposed to gadolinium-based contrast dyes.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a devastating and rapidly progressive condition, making its prevention in at-risk populations of utmost importance. In this article, the authors describe a case of a patient who developed NSF in the setting of gadolinium exposure and multiple inflammatory dermatologic conditions. This case illustrates the possible role of a pro-inflammatory state in predisposing to NSF, which may help further elucidate its mechanism of action.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old Hispanic male with a history of IV heroin use with ESRD secondary to membranous glomerulonephritis on hemodialysis and chronic hepatitis C infection presented to the West Los Angeles VAMC with fevers and night sweats that had persisted for 2 weeks. His physical examination was notable for diffuse tender palpable purpura and petechiae (including his palms and soles), altered mental status, and diffuse myoclonic jerks, which necessitated endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for airway protection. Blood cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Laboratory results were notable for an elevated sedimentation rate of 53 mm/h (0-10 mm/h), C-reactive protein of 19.8 mg/L (< 0.744 mg/dL), and albumin of 1.2 g/dL (3.2-4.8 g/dL). An extensive rheumatologic workup was unrevealing, and a lumbar puncture was unremarkable. A biopsy of his skin lesions was consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The patient’s prior hemodialysis access, a tunneled dialysis catheter in the right subclavian vein, was removed given concern for line infection and replaced with an internal jugular temporary hemodialysis line. Given his altered mental status and myoclonic jerks, the decision was made to pursue a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and spine with gadolinium contrast to evaluate for cerebral vasculitis and/or septic emboli to the brain.

The patient received 15 mL of gadoversetamide contrast in accordance with hospital imaging protocol. The MRI revealed only chronic ischemic changes. The patient underwent hemodialysis about 18 hours later. The patient was treated with a 6-week course of IV penicillin G. His altered mental status and myoclonic jerks resolved without intervention, and he was then discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit.

Eight weeks after his initial presentation the patient developed a purulent wound on his right forearm (Figure 1)

The patient was discharged to continue physical and occupational therapy to preserve his functional mobility, as no other treatment options were available.

Discussion

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a poorly understood inflammatory condition that produces diffuse fibrosis of the skin. Typically, the disease begins with progressive skin induration of the extremities. Systemic involvement may occur, leading to fibrosis of skeletal muscle, fascia, and multiple organs. Flexion contractures may develop that limit physical function. Fibrosis can become apparent within days to months after exposure to gadolinium contrast.

Beyond renal insufficiency, it is unclear what other risk factors predispose patients to developing this condition. Only a minority of patients with CKD stages 1 through 4 will develop NSF on exposure to gadolinium contrast. However, the incidence of NSF among patients with CKD stage 5 who are exposed to gadolinium has been estimated to be about 13.4% in a prospective study involving 18 patients.2

In a 2015 meta-analysis by Zhang and colleagues, the only clear risk factor identified for the development of NSF, aside from gadolinium exposure, was severe renal insufficiency with a glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.75m2.3 Due to the limited number of patients identified with this disease, it is difficult to identify other risk factors associated with the development of NSF. Based on in vitro studies, it has been postulated that a pro-inflammatory state predisposes patients to develop NSF.4,5 The proposed mechanism for NSF involves extravasation of gadolinium in the setting of vascular endothelial permeability.5,6 Gadolinium then interacts with tissue macrophages, which induce the release of inflammatory cytokines and the secretion of smooth muscle actin by dermal fibroblasts.6,7

Treatment of NSF has been largely unsuccessful. Multiple modalities of treatment that included topical and oral steroids, immunosuppression, plasmapheresis, and ultraviolent therapy have been attempted, none of which have been proven to consistently limit progression of the disease.8 The most effective intervention is early physical therapy to preserve functionality and prevent contracture formation. For patients who are eligible, early renal transplantation may offer the best chance of improved mobility. In a case series review by Cuffy and colleagues, 5 of 6 patients who underwent renal transplantation after the development of NSF experienced softening of the involved skin, and 2 patients had improved mobility of joints.9

Conclusion

The case presented here illustrates a possible association between a pro-inflammatory state and the development of NSF. This patient had multiple inflammatory conditions, including MSSA bacteremia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum (the latter 2 conditions were thought to be associated with his underlying chronic hepatitis C infection), which the authors believe predisposed him to endothelial permeability and risk for developing NSF. The risk of developing NSF in at-risk patients with each episode of gadolinium exposure is estimated around 2.4%, or an incidence of 4.3 cases per 1,000 patient-years, leading the American College of Radiologists to recommend against the administration of gadolinium-based contrast except in cases in which benefits clearly outweigh risks.10 However, an MRI with gadolinium contrast can offer high diagnostic yield in cases such as the one presented here in which a diagnosis remains elusive. Moreover, the use of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents such as gadoversetamide, as in this case, has been reported to be associated with higher incidence of NSF.5 Since this case, the West Los Angeles VAMC has switched to gadobutrol contrast for its MRI protocol, which has been purported to be a lower risk agent compared with that of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents (although several cases of NSF have been reported with gadobutrol in the literature).11

Providers weighing the decision to administer gadolinium contrast to patients with ESRD should discuss the risks and benefits thoroughly, especially in patients with preexisting inflammatory conditions. In addition, although it has not been shown to effectively reduce the risk of NSF after administration of gadolinium, hemodialysis is recommended 2 hours after contrast administration for individuals at risk (the study patient received hemodialysis approximately 18 hours after).12 Given the lack of effective treatment options for NSF, prevention is key. A deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of NSF and identification of its risk factors is paramount to the prevention of this devastating disease.

1. Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):1000-1001.

2. Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3433-3441.

3. Zhang B, Liang L, Chen W, Liang C, Zhang S. An updated study to determine association between gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129720.

4. Wermuth PJ, Del Galdo F, Jiménez SA. Induction of the expression of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors in normal human peripheral blood monocytes by gadolinium contrast agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(5):1508-1518.

5. Daftari Besheli L, Aran S, Shaqdan K, Kay J, Abujudeh H. Current status of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Clin Radiol. 2014;69(7):661-668.

6. Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;31(1):F1-F11.

7. Idée JM, Fretellier N, Robic C, Corot C. The role of gadolinium chelates in the mechanism of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a critical update. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014;44(10):895-913.

8. Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, Latinis K, Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35(4):238-249.

9. Cuffy MC, Singh M, Formica R, et al. Renal transplantation for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(3):1099-1109.

10. Deo A, Fogel M, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a population study examining the relationship of disease development of gadolinium exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):264-267

11. Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, Pedersen M, Olesen AB. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010;3(3):285-287.

12. Abu-Alfa AK. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and gadolinium-based contrast agents. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(3);188-198.

First described in 2000 in a case series of 15 patients, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare scleroderma-like fibrosing skin condition associated with gadolinium exposure in end stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ESRD are at the highest risk for this condition when exposed to gadolinium-based contrast dyes.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a devastating and rapidly progressive condition, making its prevention in at-risk populations of utmost importance. In this article, the authors describe a case of a patient who developed NSF in the setting of gadolinium exposure and multiple inflammatory dermatologic conditions. This case illustrates the possible role of a pro-inflammatory state in predisposing to NSF, which may help further elucidate its mechanism of action.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old Hispanic male with a history of IV heroin use with ESRD secondary to membranous glomerulonephritis on hemodialysis and chronic hepatitis C infection presented to the West Los Angeles VAMC with fevers and night sweats that had persisted for 2 weeks. His physical examination was notable for diffuse tender palpable purpura and petechiae (including his palms and soles), altered mental status, and diffuse myoclonic jerks, which necessitated endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for airway protection. Blood cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Laboratory results were notable for an elevated sedimentation rate of 53 mm/h (0-10 mm/h), C-reactive protein of 19.8 mg/L (< 0.744 mg/dL), and albumin of 1.2 g/dL (3.2-4.8 g/dL). An extensive rheumatologic workup was unrevealing, and a lumbar puncture was unremarkable. A biopsy of his skin lesions was consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The patient’s prior hemodialysis access, a tunneled dialysis catheter in the right subclavian vein, was removed given concern for line infection and replaced with an internal jugular temporary hemodialysis line. Given his altered mental status and myoclonic jerks, the decision was made to pursue a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and spine with gadolinium contrast to evaluate for cerebral vasculitis and/or septic emboli to the brain.

The patient received 15 mL of gadoversetamide contrast in accordance with hospital imaging protocol. The MRI revealed only chronic ischemic changes. The patient underwent hemodialysis about 18 hours later. The patient was treated with a 6-week course of IV penicillin G. His altered mental status and myoclonic jerks resolved without intervention, and he was then discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit.

Eight weeks after his initial presentation the patient developed a purulent wound on his right forearm (Figure 1)

The patient was discharged to continue physical and occupational therapy to preserve his functional mobility, as no other treatment options were available.

Discussion

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a poorly understood inflammatory condition that produces diffuse fibrosis of the skin. Typically, the disease begins with progressive skin induration of the extremities. Systemic involvement may occur, leading to fibrosis of skeletal muscle, fascia, and multiple organs. Flexion contractures may develop that limit physical function. Fibrosis can become apparent within days to months after exposure to gadolinium contrast.

Beyond renal insufficiency, it is unclear what other risk factors predispose patients to developing this condition. Only a minority of patients with CKD stages 1 through 4 will develop NSF on exposure to gadolinium contrast. However, the incidence of NSF among patients with CKD stage 5 who are exposed to gadolinium has been estimated to be about 13.4% in a prospective study involving 18 patients.2

In a 2015 meta-analysis by Zhang and colleagues, the only clear risk factor identified for the development of NSF, aside from gadolinium exposure, was severe renal insufficiency with a glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.75m2.3 Due to the limited number of patients identified with this disease, it is difficult to identify other risk factors associated with the development of NSF. Based on in vitro studies, it has been postulated that a pro-inflammatory state predisposes patients to develop NSF.4,5 The proposed mechanism for NSF involves extravasation of gadolinium in the setting of vascular endothelial permeability.5,6 Gadolinium then interacts with tissue macrophages, which induce the release of inflammatory cytokines and the secretion of smooth muscle actin by dermal fibroblasts.6,7

Treatment of NSF has been largely unsuccessful. Multiple modalities of treatment that included topical and oral steroids, immunosuppression, plasmapheresis, and ultraviolent therapy have been attempted, none of which have been proven to consistently limit progression of the disease.8 The most effective intervention is early physical therapy to preserve functionality and prevent contracture formation. For patients who are eligible, early renal transplantation may offer the best chance of improved mobility. In a case series review by Cuffy and colleagues, 5 of 6 patients who underwent renal transplantation after the development of NSF experienced softening of the involved skin, and 2 patients had improved mobility of joints.9

Conclusion

The case presented here illustrates a possible association between a pro-inflammatory state and the development of NSF. This patient had multiple inflammatory conditions, including MSSA bacteremia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum (the latter 2 conditions were thought to be associated with his underlying chronic hepatitis C infection), which the authors believe predisposed him to endothelial permeability and risk for developing NSF. The risk of developing NSF in at-risk patients with each episode of gadolinium exposure is estimated around 2.4%, or an incidence of 4.3 cases per 1,000 patient-years, leading the American College of Radiologists to recommend against the administration of gadolinium-based contrast except in cases in which benefits clearly outweigh risks.10 However, an MRI with gadolinium contrast can offer high diagnostic yield in cases such as the one presented here in which a diagnosis remains elusive. Moreover, the use of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents such as gadoversetamide, as in this case, has been reported to be associated with higher incidence of NSF.5 Since this case, the West Los Angeles VAMC has switched to gadobutrol contrast for its MRI protocol, which has been purported to be a lower risk agent compared with that of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents (although several cases of NSF have been reported with gadobutrol in the literature).11

Providers weighing the decision to administer gadolinium contrast to patients with ESRD should discuss the risks and benefits thoroughly, especially in patients with preexisting inflammatory conditions. In addition, although it has not been shown to effectively reduce the risk of NSF after administration of gadolinium, hemodialysis is recommended 2 hours after contrast administration for individuals at risk (the study patient received hemodialysis approximately 18 hours after).12 Given the lack of effective treatment options for NSF, prevention is key. A deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of NSF and identification of its risk factors is paramount to the prevention of this devastating disease.

First described in 2000 in a case series of 15 patients, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare scleroderma-like fibrosing skin condition associated with gadolinium exposure in end stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ESRD are at the highest risk for this condition when exposed to gadolinium-based contrast dyes.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a devastating and rapidly progressive condition, making its prevention in at-risk populations of utmost importance. In this article, the authors describe a case of a patient who developed NSF in the setting of gadolinium exposure and multiple inflammatory dermatologic conditions. This case illustrates the possible role of a pro-inflammatory state in predisposing to NSF, which may help further elucidate its mechanism of action.

Case Presentation