User login

Cutaneous Body Image: How the Mental Health Benefits of Treating Dermatologic Disease Support Military Readiness in Service Members

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

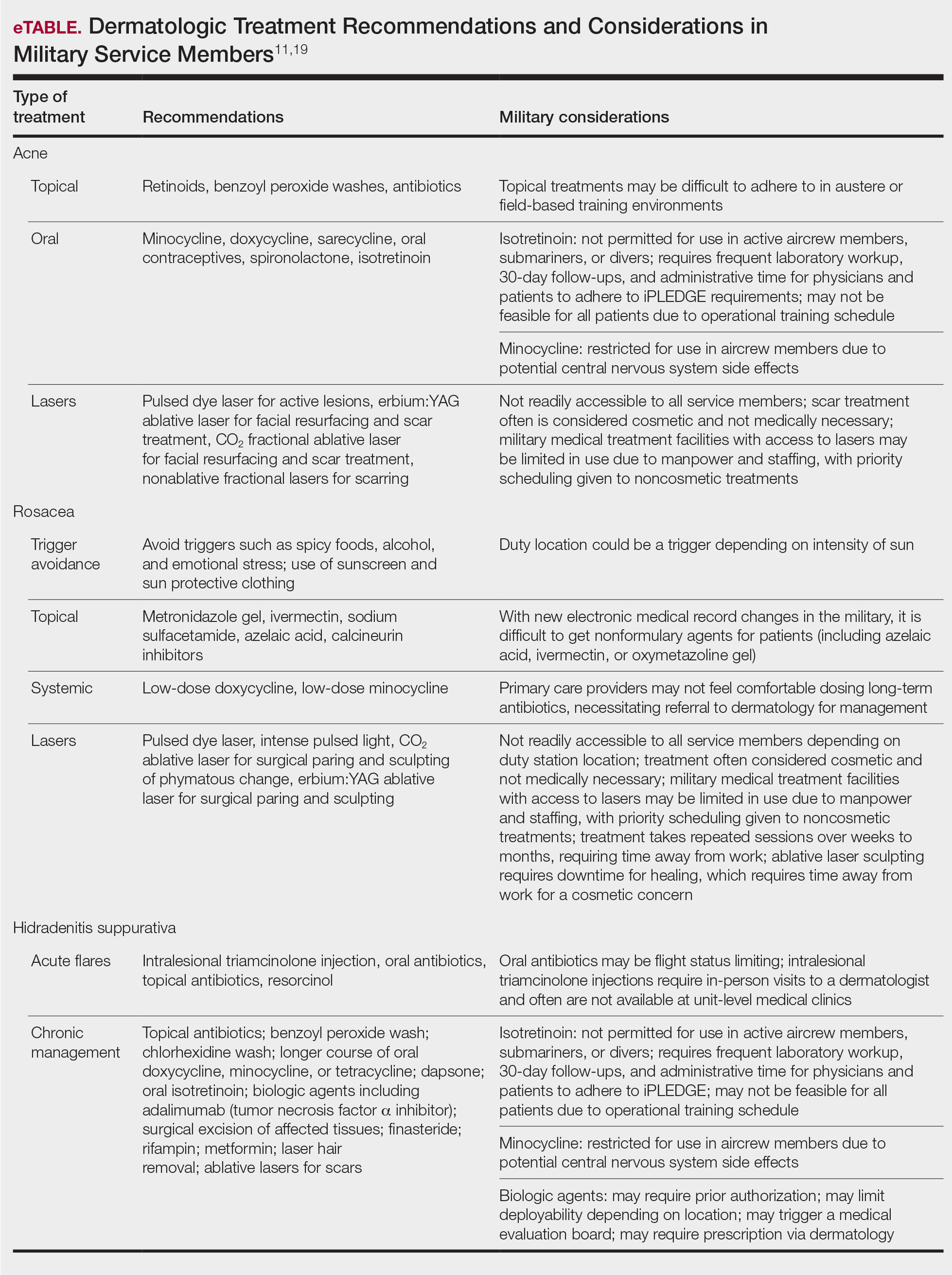

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, LaCroix JM, Koss K, et al. Outpatient mental health treatment utilization and military career impact in the United States Marine Corps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:828. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040828

- Ottignon DA. Marine Corps Suicide Prevention System (MCSPS). Marine Corps Order 1720.2A. 2021. Headquarters United States Marine Corps. Published August 2, 2021. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%201720.2A.pdf?ver=QPxZ_qMS-X-d037B65N9Tg%3d%3d

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Carter SP. Suicide prevention in the US Army: a mission for more than mental health clinicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:991-992. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2042

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2015 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology (T2); 2016. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Department-of-Defense-Suicide-Event-Report

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, et al. Risk factors associated with attempted suicide among US Army soldiers without a history of mental health diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1022-1032. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2069

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Cutaneous body image dissatisfaction and suicidal ideation: mediation by interpersonal sensitivity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:55-59. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.015

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Evaluation of cutaneous body image dissatisfaction in the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.010

- Hinkley SB, Holub SC, Menter A. The validity of cutaneous body image as a construct and as a mediator of the relationship between cutaneous disease and mental health. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:203-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00351-5

- Stamu-O’Brien C, Jafferany M, Carniciu S, et al. Psychodermatology of acne: psychological aspects and effects of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1080-1083. doi:10.1111/jocd.13765

- Sood S, Jafferany M, Vinaya Kumar S. Depression, psychiatric comorbidities, and psychosocial implications associated with acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:3177-3182. doi:10.1111/jocd.13753

- Brahe C, Peters K. Fighting acne for the fighting forces. Cutis. 2020;106:18-20, 22. doi:10.12788/cutis.0057

- Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246-250.

- Xu S, Zhu Y, Hu H, et al. The analysis of acne increasing suicide risk. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:E26035. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026035

- Chen M, Deng Z, Huang Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression in rosacea patients: a cross-sectional study in China [published online June 16, 2021]. Front Psychiatry. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659171

- Incel Uysal P, Akdogan N, Hayran Y, et al. Rosacea associated with increased risk of generalized anxiety disorder: a case-control study of prevalence and risk of anxiety in patients with rosacea. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:704-709. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.03.002

- Alinia H, Cardwell LA, Tuchayi SM, et al. Screening for depression in rosacea patients. Cutis. 2018;102:36-38.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.843

- Misitzis A, Goldust M, Jafferany M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13541. doi:10.1111/dth.13541

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

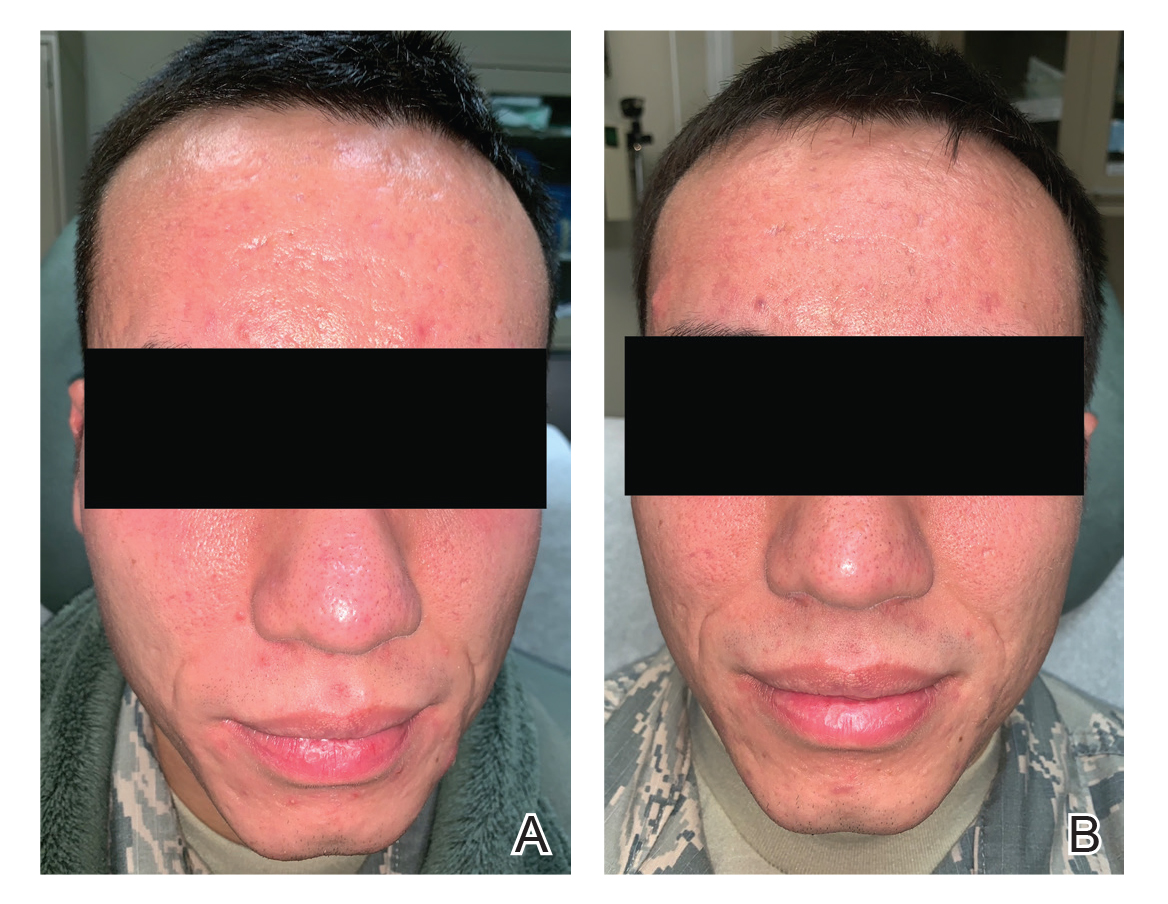

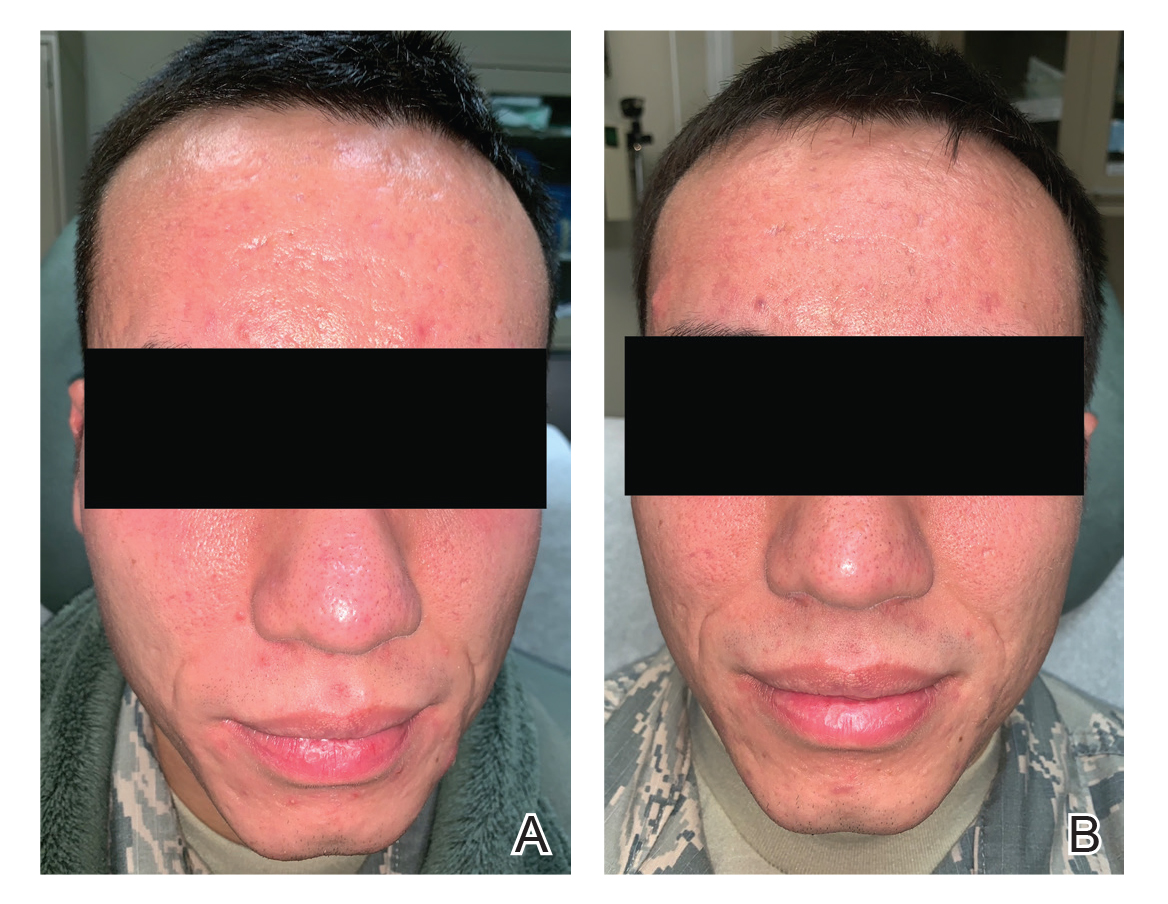

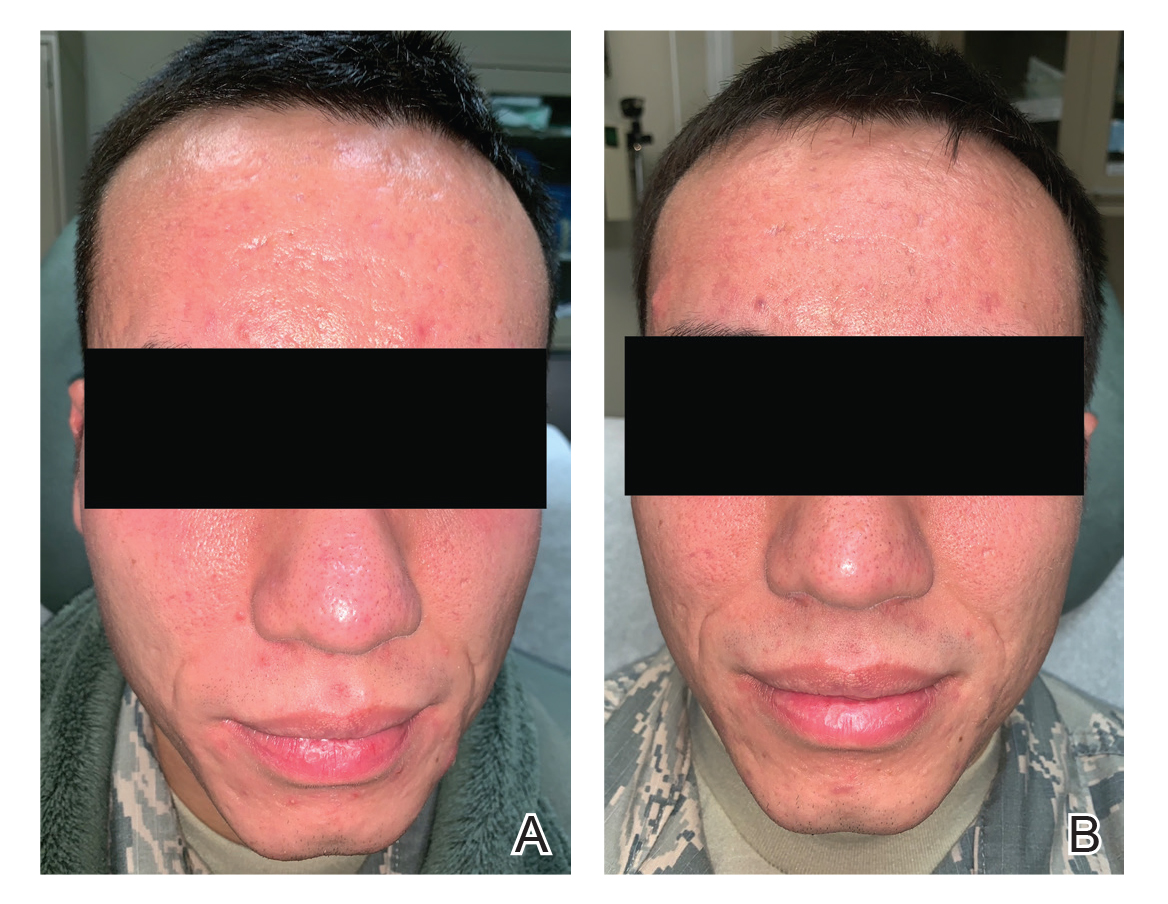

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, LaCroix JM, Koss K, et al. Outpatient mental health treatment utilization and military career impact in the United States Marine Corps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:828. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040828

- Ottignon DA. Marine Corps Suicide Prevention System (MCSPS). Marine Corps Order 1720.2A. 2021. Headquarters United States Marine Corps. Published August 2, 2021. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%201720.2A.pdf?ver=QPxZ_qMS-X-d037B65N9Tg%3d%3d

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Carter SP. Suicide prevention in the US Army: a mission for more than mental health clinicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:991-992. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2042

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2015 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology (T2); 2016. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Department-of-Defense-Suicide-Event-Report

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, et al. Risk factors associated with attempted suicide among US Army soldiers without a history of mental health diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1022-1032. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2069

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Cutaneous body image dissatisfaction and suicidal ideation: mediation by interpersonal sensitivity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:55-59. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.015

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Evaluation of cutaneous body image dissatisfaction in the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.010

- Hinkley SB, Holub SC, Menter A. The validity of cutaneous body image as a construct and as a mediator of the relationship between cutaneous disease and mental health. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:203-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00351-5

- Stamu-O’Brien C, Jafferany M, Carniciu S, et al. Psychodermatology of acne: psychological aspects and effects of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1080-1083. doi:10.1111/jocd.13765

- Sood S, Jafferany M, Vinaya Kumar S. Depression, psychiatric comorbidities, and psychosocial implications associated with acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:3177-3182. doi:10.1111/jocd.13753

- Brahe C, Peters K. Fighting acne for the fighting forces. Cutis. 2020;106:18-20, 22. doi:10.12788/cutis.0057

- Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246-250.

- Xu S, Zhu Y, Hu H, et al. The analysis of acne increasing suicide risk. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:E26035. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026035

- Chen M, Deng Z, Huang Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression in rosacea patients: a cross-sectional study in China [published online June 16, 2021]. Front Psychiatry. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659171

- Incel Uysal P, Akdogan N, Hayran Y, et al. Rosacea associated with increased risk of generalized anxiety disorder: a case-control study of prevalence and risk of anxiety in patients with rosacea. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:704-709. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.03.002

- Alinia H, Cardwell LA, Tuchayi SM, et al. Screening for depression in rosacea patients. Cutis. 2018;102:36-38.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.843

- Misitzis A, Goldust M, Jafferany M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13541. doi:10.1111/dth.13541

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, LaCroix JM, Koss K, et al. Outpatient mental health treatment utilization and military career impact in the United States Marine Corps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:828. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040828

- Ottignon DA. Marine Corps Suicide Prevention System (MCSPS). Marine Corps Order 1720.2A. 2021. Headquarters United States Marine Corps. Published August 2, 2021. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%201720.2A.pdf?ver=QPxZ_qMS-X-d037B65N9Tg%3d%3d

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Carter SP. Suicide prevention in the US Army: a mission for more than mental health clinicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:991-992. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2042

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2015 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology (T2); 2016. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Department-of-Defense-Suicide-Event-Report

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, et al. Risk factors associated with attempted suicide among US Army soldiers without a history of mental health diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1022-1032. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2069

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Cutaneous body image dissatisfaction and suicidal ideation: mediation by interpersonal sensitivity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:55-59. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.015

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Evaluation of cutaneous body image dissatisfaction in the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.010

- Hinkley SB, Holub SC, Menter A. The validity of cutaneous body image as a construct and as a mediator of the relationship between cutaneous disease and mental health. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:203-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00351-5

- Stamu-O’Brien C, Jafferany M, Carniciu S, et al. Psychodermatology of acne: psychological aspects and effects of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1080-1083. doi:10.1111/jocd.13765

- Sood S, Jafferany M, Vinaya Kumar S. Depression, psychiatric comorbidities, and psychosocial implications associated with acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:3177-3182. doi:10.1111/jocd.13753

- Brahe C, Peters K. Fighting acne for the fighting forces. Cutis. 2020;106:18-20, 22. doi:10.12788/cutis.0057

- Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246-250.

- Xu S, Zhu Y, Hu H, et al. The analysis of acne increasing suicide risk. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:E26035. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026035

- Chen M, Deng Z, Huang Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression in rosacea patients: a cross-sectional study in China [published online June 16, 2021]. Front Psychiatry. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659171

- Incel Uysal P, Akdogan N, Hayran Y, et al. Rosacea associated with increased risk of generalized anxiety disorder: a case-control study of prevalence and risk of anxiety in patients with rosacea. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:704-709. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.03.002

- Alinia H, Cardwell LA, Tuchayi SM, et al. Screening for depression in rosacea patients. Cutis. 2018;102:36-38.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.843

- Misitzis A, Goldust M, Jafferany M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13541. doi:10.1111/dth.13541

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

Practice Points

- The term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that are ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat.

- Maintaining readiness requires a holistic approach, as it is directly affected by physical and mental health outcomes.

- Cutaneous body image (CBI) refers to an individual’s mental perception of the condition of their hair, nails, and skin. Positive CBI is related to increased quality of life, while negative CBI, which often is associated with dermatologic disease, is associated with poorer health outcomes and even self-injury.

- Treatment of dermatologic disease in the context of active-duty military members can positively influence CBI, which may in turn increase service members’ quality of life and overall military readiness.

Oral Isotretinoin for Acne in the US Military: How Accelerated Courses and Teledermatology Can Minimize the Duty-Limiting Impacts of Treatment

Acne vulgaris is an extremely common dermatologic disease affecting 40 to 50 million individuals in the United States each year, with a prevalence of 85% in adolescents and young adults aged 12 to 24 years. For some patients, the disease may persist well into adulthood, affecting 8% of adults aged 25 and 34 years.1 Acne negatively impacts patients’ quality of life and productivity, with an estimated direct and indirect cost of over $3 billion per year.2

Oral isotretinoin, a vitamin A derivative, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of severe nodulocystic acne. Isotretinoin reduces the size and secretions of sebaceous glands, inhibits growth and resulting inflammation of Cutibacterium acnes, and normalizes the differentiation of follicular keratinocytes, resulting in permanent changes in the pathogenesis of acne that may lead to remission.3 The use of oral isotretinoin in the active-duty US Military population may cause service members to be nondeployable or limit their ability to function in special roles (eg, pilot, submariner).4 Treatment regimens that minimize the course duration of isotretinoin and reduce the risk for relapse that requires a retrial of isotretinoin may, in turn, increase a service member’s readiness, deployment availability, and ability to perform unique occupational roles.

Additionally, teledermatology has been increasingly utilized to maintain treatment continuity for patients on isotretinoin during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 Application of this technology in the military also may be used to facilitate timely isotretinoin treatment regimens in active-duty service members to minimize course duration and increase readiness.

In this article, we discuss an accelerated course of oral isotretinoin as a safe and effective option for military service members bound by duty restrictions and operational timelines and explore the role of teledermatology for the treatment of acne in military service members.

Isotretinoin for Acne

Isotretinoin typically is initiated at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg daily, increasing to 1 mg/kg daily with a goal cumulative dose between 120 and 150 mg/kg. Relapse may occur after completing a treatment course and is associated with cumulative dosing less than 120 mg/kg.6 The average duration of acne treatment with oral isotretinoin is approximately 6 months.7 At therapeutic doses, nearly all patients experience side effects, most commonly dryness and desquamation of the skin and mucous membranes, as well as possible involvement of the lips, eyes, and nose. Notable extracutaneous side effects include headache, visual disturbances at night, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and myalgia. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and transaminases may be increased in patients taking isotretinoin, which requires routine monitoring using serum lipid profiles and liver function studies. A potential association between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease and changes in mood have been reported, but current data do not suggest an evidence-based link.6,8 Isotretinoin is a potent teratogen, and in the United States, all patients are required to enroll in iPLEDGE, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved pregnancy prevention program that monitors prescribing and dispensing of the medication. For patients who can become pregnant, iPLEDGE requires use of 2 forms of contraception as well as monthly pregnancy tests prior to dispensing the medication.

Acne in Military Service Members

Acne is exceedingly common in the active-duty military population. In 2018, more than 40% of soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines were 25 years or younger, and 75% of all US service members were 35 years or younger, corresponding to acne peak incidences.1,9 Management of acne in this population requires unique treatment considerations due to distinctive occupational requirements of and hazards faced by military personnel. Use of personal protective equipment, including gas masks, safety restraints, parachute rigging, and flak jackets, may be limiting in individuals with moderate to severe acne.10 For example, severe nodulocystic acne on the chin and jawline can interfere with proper wear of the chin strap on a Kevlar helmet. The severity of acne often necessitates the use of oral isotretinoin therapy, which is considered disqualifying for many special military assignments, including submarine duty, nuclear field duty, and diving duty.11 In military aviation communities, oral isotretinoin requires grounding for the duration of therapy plus 3 months after cessation. Slit-lamp examination, triglycerides, and transaminase levels must be normal prior to returning to unrestricted duty.12 Furthermore, use of oral isotretinoin may limit overseas assignments or deployment eligibility.4

The high prevalence of acne and the operationally limiting consequences of isotretinoin therapy present a unique challenge for dermatologists treating military personnel. The average duration of isotretinoin treatment is approximately 6 months,7 which represents a considerable amount of time during an average 4-year enlistment contract. Therapeutic treatment strategies that (1) reduce the duration of oral isotretinoin therapy, (2) reduce the risk for relapse, and (3) increase medication compliance can reduce the operational impact of this acne treatment. Such treatment strategies are discussed below.

High-Dose Isotretinoin

An optimal isotretinoin dosing regimen would achieve swift resolution of acne lesions and reduce the overall relapse rate requiring retrial of isotretinoin, thereby minimizing the operational- and duty-limiting impacts of the medication. Cyrulnik et al13 studied treatment outcomes of high-dose isotretinoin for acne vulgaris using a mean dosage of 1.6 mg/kg daily with an average cumulative dosage of 290 mg/kg. They demonstrated 100% clearance of lesions over 6 months, with a 12.5% relapse rate at 3 years. Aside from an increased rate of elevated transaminases, incidence of adverse effects and laboratory abnormalities were not significantly increased compared to conventional dosing regimens.13 The goal cumulative dosing of 120 to 150 mg/kg can be achieved 1 to 2 months earlier using a dosage of 1.6 mg/kg daily vs a conventional dosage of 1 mg/kg daily.

It has been hypothesized that higher cumulative doses of oral isotretinoin reduce the risk for relapse of acne and retrial of oral isotretinoin.14 Blasiak et al15 studied relapse and retrial of oral isotretinoin in acne patients who received cumulative dosing higher or lower than 220 mg/kg. A clinically but not statistically significant reduced relapse rate was observed in the cohort that received cumulative dosing higher than 220 mg/kg. No statistically significant difference in rates of adverse advents was observed aside from an increase in retinoid dermatitis in the cohort that received cumulative dosing higher than 220 mg/kg. Higher but not statistically significant rates of adverse events were seen in the group that received dosing higher than 220 mg/kg.15 Cumulative doses of oral isotretinoin higher than the 120 to 150 mg/kg range may decrease the risk for acne relapse and the need for an additional course of oral isotretinoin, which would reduce a service member’s total time away from deployment and full duty.

Relapse requiring a retrial of oral isotretinoin not only increases the operational cost of acne treatment but also considerably increases the monetary cost to the health care system. In a cost-analysis model, cumulative doses of oral isotretinoin higher than 230 mg/kg have a decreased overall cost compared to traditional cumulative dosing of less than 150 mg/kg due to the cost of relapse.16

Limitations of high daily and cumulative dosing regimens of oral isotretinoin are chiefly the dose-dependent rate of adverse effects. Low-dose regimens are associated with a reduced risk of isotretinoin-related side effects.6,17 Acute acne flares may be seen following initial administration of oral isotretinoin and are aggravated by increases in dosage.18 Isotretinoin-induced acne fulminans is a rare but devastating complication observed with high initial doses of oral isotretinoin in patients with severe acne.19 The risks and benefits of high daily and cumulatively dosed isotretinoin must be carefully considered in patients with severe acne.

Teledermatology: A Force for Readiness

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically changed the dermatology practice landscape with recommendations to cancel all elective outpatient visits in favor of teledermatology encounters.20 This decreased access to care, which resulted in an increase in drug interruption for dermatology patients, including patients on oral isotretinoin.21 Teledermatology has been increasingly utilized to maintain continuity of care for the management of patients taking isotretinoin.5 Routine utilization of teledermatology evaluation in military practices could expedite care, decrease patient travel time, and allow for in-clinic visits to be utilized for higher-acuity concerns.22

The use of teledermatology for uncomplicated oral isotretinoin management has the potential to increase medication compliance and decrease the amount of travel time for active-duty service members; for example, consider a military dermatology practice based in San Diego, California, that accepts referrals from military bases 3 hours away by car. After an initial consultation for consideration and initiation of oral isotretinoin, teledermatology appointments can save the active-duty service member 3 hours of travel time for each follow-up visit per month. This ultimately increases operational productivity, reduces barriers to accessing care, and improves patient satisfaction.23

Although military personnel usually are located at duty stations for 2 to 4 years, training exercises and military vocational schools often temporarily take personnel away from their home station. These temporary-duty assignments have the potential to interrupt medical follow-up appointments and may cause delays in treatment for individuals who miss monthly isotretinoin visits. When deemed appropriate by the prescribing dermatologist, teledermatology allows for increased continuity of care for active-duty service members and maintenance of a therapeutic isotretinoin course despite temporary geographic displacement.

By facilitating regular follow-up appointments, teledermatology can minimize the amount of time an active-duty service member is on a course of oral isotretinoin, thereby reducing the operational and duty-limiting implications of the medication.

Final Thoughts

Acne is a common dermatologic concern within the active-duty military population. Oral isotretinoin is indicated for treatment-resistant moderate or severe acne; however, it limits the ability of service members to deploy and is disqualifying for special military assignments. High daily- and cumulative-dose isotretinoin treatment strategies can reduce the duration of therapy and may be associated with a decrease in acne relapse and the need for retrial. Teledermatology can increase access to care and facilitate the completion of oral isotretinoin courses in a timely manner. These treatment strategies may help mitigate the duty-limiting impact of oral isotretinoin therapy in military service members.

- White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34-S37. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048

- James WD. Clinical practice. acne. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1463-1472. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp033487

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho SH. Treatment consideration for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019;103:329-332.

- Rosamilia LL. Isotretinoin meets COVID-19: revisiting a fragmented paradigm. Cutis. 2021;108:8-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0299

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

- Huang KE, Carstensen SE, Feldman SR. The duration of acne treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:655-656.

- Bettoli V, Guerra-Tapia A, Herane MI, et al. Challenges and solutions in oral isotretinoin in acne: reflections on 35 years of experience. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:943-951. doi:10.2147/CCID.S234231

- US Department of Defense. 2018 demographics report: profile of the military community. Accessed January 18, 2022. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2018-demographics-report.pdf

- Brahe C, Peters K. Fighting acne for the fighting forces. Cutis. 2020;106:18-20, 22. doi:10.12788/cutis.0057

- US Department of the Navy. Change 167. manual of the medical department. Published February 15, 2019. Accessed January 18, 2022. https://www.med.navy.mil/Portals/62/Documents/BUMED/Directives/MANMED/Chapter%2015%20Medical%20Examinations%20(incorporates%20Changes%20126_135-138_140_145_150-152_154-156_160_164-167).pdf?ver=Rj7AoH54dNAX5uS3F1JUfw%3d%3d

- US Department of the Navy. US Navy aeromedical reference and waiver guide. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed January 18, 2022. https://www.med.navy.mil/Portals/62/Documents/NMFSC/NMOTC/NAMI/ARWG/Waiver%20Guide/ARWG%20COMPLETE_210811.pdf?ver=_pLPzFrtl8E2swFESnN4rA%3d%3d

- Cyrulnik AA, Viola KV, Gewirtzman AJ, et al. High-dose isotretinoin in acne vulgaris: improved treatment outcomes and quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1123-1130. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05409.x

- Coloe J, Du H, Morrell DS. Could higher doses of isotretinoin reduce the frequency of treatment failure in patients with acne? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:422-423. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.025

- Blasiak RC, Stamey CR, Burkhart CN, et al. High-dose isotretinoin treatment and the rate of retrial, relapse, and adverse effects in patients with acne vulgaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1392-1398. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6746

- Zeitany AE, Bowers EV, Morrell DS. High-dose isotretinoin has lower impact on wallets: a cost analysis of dosing approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:174-176. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.012

- Amichai B, Shemer A, Grunwald MH. Low-dose isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:644-666. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1061

- Borghi A, Mantovani L, Minghetti S, et al. Acute acne flare following isotretinoin administration: potential protective role of low starting dose. Dermatology. 2009;218:178-180. doi:10.1159/000182270

- Greywal T, Zaenglein AL, Baldwin HE, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of acne fulminans and its variants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:109-117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.028

- Kwatra SG, Sweren RJ, Grossberg AL. Dermatology practices as vectors for COVID-19 transmission: a call for immediate cessation of nonemergent dermatology visits. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E179-E180. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.037

- Alshiyab DM, Al-Qarqaz FA, Muhaidat JM. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the continuity of care for dermatologic patients on systemic therapy during the period of strict lockdown. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;60:571-574. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2020.11.056

- Hwang J, Kakimoto C. Teledermatology in the US military: a historic foundation for current and future applications. Cutis. 2018;101:335,337,345.

- Ruggiero A, Megna M, Annunziata MC, et al. Teledermatology for acne during COVID-19: high patients’ satisfaction in spite of the emergency. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E662-E663. doi:10.1111/jdv.16746

Acne vulgaris is an extremely common dermatologic disease affecting 40 to 50 million individuals in the United States each year, with a prevalence of 85% in adolescents and young adults aged 12 to 24 years. For some patients, the disease may persist well into adulthood, affecting 8% of adults aged 25 and 34 years.1 Acne negatively impacts patients’ quality of life and productivity, with an estimated direct and indirect cost of over $3 billion per year.2

Oral isotretinoin, a vitamin A derivative, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of severe nodulocystic acne. Isotretinoin reduces the size and secretions of sebaceous glands, inhibits growth and resulting inflammation of Cutibacterium acnes, and normalizes the differentiation of follicular keratinocytes, resulting in permanent changes in the pathogenesis of acne that may lead to remission.3 The use of oral isotretinoin in the active-duty US Military population may cause service members to be nondeployable or limit their ability to function in special roles (eg, pilot, submariner).4 Treatment regimens that minimize the course duration of isotretinoin and reduce the risk for relapse that requires a retrial of isotretinoin may, in turn, increase a service member’s readiness, deployment availability, and ability to perform unique occupational roles.

Additionally, teledermatology has been increasingly utilized to maintain treatment continuity for patients on isotretinoin during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 Application of this technology in the military also may be used to facilitate timely isotretinoin treatment regimens in active-duty service members to minimize course duration and increase readiness.

In this article, we discuss an accelerated course of oral isotretinoin as a safe and effective option for military service members bound by duty restrictions and operational timelines and explore the role of teledermatology for the treatment of acne in military service members.

Isotretinoin for Acne

Isotretinoin typically is initiated at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg daily, increasing to 1 mg/kg daily with a goal cumulative dose between 120 and 150 mg/kg. Relapse may occur after completing a treatment course and is associated with cumulative dosing less than 120 mg/kg.6 The average duration of acne treatment with oral isotretinoin is approximately 6 months.7 At therapeutic doses, nearly all patients experience side effects, most commonly dryness and desquamation of the skin and mucous membranes, as well as possible involvement of the lips, eyes, and nose. Notable extracutaneous side effects include headache, visual disturbances at night, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and myalgia. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and transaminases may be increased in patients taking isotretinoin, which requires routine monitoring using serum lipid profiles and liver function studies. A potential association between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease and changes in mood have been reported, but current data do not suggest an evidence-based link.6,8 Isotretinoin is a potent teratogen, and in the United States, all patients are required to enroll in iPLEDGE, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved pregnancy prevention program that monitors prescribing and dispensing of the medication. For patients who can become pregnant, iPLEDGE requires use of 2 forms of contraception as well as monthly pregnancy tests prior to dispensing the medication.

Acne in Military Service Members

Acne is exceedingly common in the active-duty military population. In 2018, more than 40% of soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines were 25 years or younger, and 75% of all US service members were 35 years or younger, corresponding to acne peak incidences.1,9 Management of acne in this population requires unique treatment considerations due to distinctive occupational requirements of and hazards faced by military personnel. Use of personal protective equipment, including gas masks, safety restraints, parachute rigging, and flak jackets, may be limiting in individuals with moderate to severe acne.10 For example, severe nodulocystic acne on the chin and jawline can interfere with proper wear of the chin strap on a Kevlar helmet. The severity of acne often necessitates the use of oral isotretinoin therapy, which is considered disqualifying for many special military assignments, including submarine duty, nuclear field duty, and diving duty.11 In military aviation communities, oral isotretinoin requires grounding for the duration of therapy plus 3 months after cessation. Slit-lamp examination, triglycerides, and transaminase levels must be normal prior to returning to unrestricted duty.12 Furthermore, use of oral isotretinoin may limit overseas assignments or deployment eligibility.4

The high prevalence of acne and the operationally limiting consequences of isotretinoin therapy present a unique challenge for dermatologists treating military personnel. The average duration of isotretinoin treatment is approximately 6 months,7 which represents a considerable amount of time during an average 4-year enlistment contract. Therapeutic treatment strategies that (1) reduce the duration of oral isotretinoin therapy, (2) reduce the risk for relapse, and (3) increase medication compliance can reduce the operational impact of this acne treatment. Such treatment strategies are discussed below.

High-Dose Isotretinoin

An optimal isotretinoin dosing regimen would achieve swift resolution of acne lesions and reduce the overall relapse rate requiring retrial of isotretinoin, thereby minimizing the operational- and duty-limiting impacts of the medication. Cyrulnik et al13 studied treatment outcomes of high-dose isotretinoin for acne vulgaris using a mean dosage of 1.6 mg/kg daily with an average cumulative dosage of 290 mg/kg. They demonstrated 100% clearance of lesions over 6 months, with a 12.5% relapse rate at 3 years. Aside from an increased rate of elevated transaminases, incidence of adverse effects and laboratory abnormalities were not significantly increased compared to conventional dosing regimens.13 The goal cumulative dosing of 120 to 150 mg/kg can be achieved 1 to 2 months earlier using a dosage of 1.6 mg/kg daily vs a conventional dosage of 1 mg/kg daily.

It has been hypothesized that higher cumulative doses of oral isotretinoin reduce the risk for relapse of acne and retrial of oral isotretinoin.14 Blasiak et al15 studied relapse and retrial of oral isotretinoin in acne patients who received cumulative dosing higher or lower than 220 mg/kg. A clinically but not statistically significant reduced relapse rate was observed in the cohort that received cumulative dosing higher than 220 mg/kg. No statistically significant difference in rates of adverse advents was observed aside from an increase in retinoid dermatitis in the cohort that received cumulative dosing higher than 220 mg/kg. Higher but not statistically significant rates of adverse events were seen in the group that received dosing higher than 220 mg/kg.15 Cumulative doses of oral isotretinoin higher than the 120 to 150 mg/kg range may decrease the risk for acne relapse and the need for an additional course of oral isotretinoin, which would reduce a service member’s total time away from deployment and full duty.

Relapse requiring a retrial of oral isotretinoin not only increases the operational cost of acne treatment but also considerably increases the monetary cost to the health care system. In a cost-analysis model, cumulative doses of oral isotretinoin higher than 230 mg/kg have a decreased overall cost compared to traditional cumulative dosing of less than 150 mg/kg due to the cost of relapse.16

Limitations of high daily and cumulative dosing regimens of oral isotretinoin are chiefly the dose-dependent rate of adverse effects. Low-dose regimens are associated with a reduced risk of isotretinoin-related side effects.6,17 Acute acne flares may be seen following initial administration of oral isotretinoin and are aggravated by increases in dosage.18 Isotretinoin-induced acne fulminans is a rare but devastating complication observed with high initial doses of oral isotretinoin in patients with severe acne.19 The risks and benefits of high daily and cumulatively dosed isotretinoin must be carefully considered in patients with severe acne.

Teledermatology: A Force for Readiness

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically changed the dermatology practice landscape with recommendations to cancel all elective outpatient visits in favor of teledermatology encounters.20 This decreased access to care, which resulted in an increase in drug interruption for dermatology patients, including patients on oral isotretinoin.21 Teledermatology has been increasingly utilized to maintain continuity of care for the management of patients taking isotretinoin.5 Routine utilization of teledermatology evaluation in military practices could expedite care, decrease patient travel time, and allow for in-clinic visits to be utilized for higher-acuity concerns.22

The use of teledermatology for uncomplicated oral isotretinoin management has the potential to increase medication compliance and decrease the amount of travel time for active-duty service members; for example, consider a military dermatology practice based in San Diego, California, that accepts referrals from military bases 3 hours away by car. After an initial consultation for consideration and initiation of oral isotretinoin, teledermatology appointments can save the active-duty service member 3 hours of travel time for each follow-up visit per month. This ultimately increases operational productivity, reduces barriers to accessing care, and improves patient satisfaction.23

Although military personnel usually are located at duty stations for 2 to 4 years, training exercises and military vocational schools often temporarily take personnel away from their home station. These temporary-duty assignments have the potential to interrupt medical follow-up appointments and may cause delays in treatment for individuals who miss monthly isotretinoin visits. When deemed appropriate by the prescribing dermatologist, teledermatology allows for increased continuity of care for active-duty service members and maintenance of a therapeutic isotretinoin course despite temporary geographic displacement.

By facilitating regular follow-up appointments, teledermatology can minimize the amount of time an active-duty service member is on a course of oral isotretinoin, thereby reducing the operational and duty-limiting implications of the medication.

Final Thoughts

Acne is a common dermatologic concern within the active-duty military population. Oral isotretinoin is indicated for treatment-resistant moderate or severe acne; however, it limits the ability of service members to deploy and is disqualifying for special military assignments. High daily- and cumulative-dose isotretinoin treatment strategies can reduce the duration of therapy and may be associated with a decrease in acne relapse and the need for retrial. Teledermatology can increase access to care and facilitate the completion of oral isotretinoin courses in a timely manner. These treatment strategies may help mitigate the duty-limiting impact of oral isotretinoin therapy in military service members.

Acne vulgaris is an extremely common dermatologic disease affecting 40 to 50 million individuals in the United States each year, with a prevalence of 85% in adolescents and young adults aged 12 to 24 years. For some patients, the disease may persist well into adulthood, affecting 8% of adults aged 25 and 34 years.1 Acne negatively impacts patients’ quality of life and productivity, with an estimated direct and indirect cost of over $3 billion per year.2