User login

Fighting Acne for the Fighting Forces

Acne treatment presents unique challenges in the active-duty military population. Lesions on the face may interfere with proper fit and seal of protective masks and helmets, while those involving the shoulders or back may cause considerable discomfort beneath safety restraints, parachute harnesses, or flak jackets. Therefore, untreated acne may limit servicemembers from performing their assigned duties. Treatments themselves also may be limiting; for instance, aircrew members who are taking oral doxycycline, tetracycline, or erythromycin may be grounded (ie, temporarily removed from duty) during and after therapy to monitor for side effects. Minocycline is considered unacceptable for aviators and is completely restricted for use due to risk for central nervous system side effects. Isotretinoin is restricted in aircrew members, submariners, and divers. If initiated, isotretinoin requires grounding for the entire duration of therapy and up to 3 months following treatment. Normalization of triglyceride levels and slit-lamp ocular examination also must take place prior to return to full duty, which may lead to additional grounding time. Well-established topical and oral treatments not impacting military duty are omitted from this review.

Antibiotics

Minocycline

Minocycline carries a small risk for development of systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune treatment-emergent adverse effects. It has known gastrointestinal tract side effects, and long-term use also can lead to bluish discoloration of the skin.1 Systemic minocycline is restricted in aircrew members due to its risk for central nervous system side effects, including light-headedness, dizziness, and vertigo.2-5

A topical formulation of minocycline recently was developed and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a means to reduce systemic adverse effects. This 4% minocycline foam has thus far been safe and well tolerated, with adverse events reported in less than 1% of study participants.1,6 In addition, topical minocycline was shown in a recent phase 3 study to notably reduce inflammatory lesion counts when compared to control vehicles at as early as 3 weeks.7 Topical minocycline may emerge as a viable treatment option for active-duty servicemembers in the future.

Doxycycline

Doxycycline is not medically disqualifying. Even so, it may still necessitate grounding for a period of time while monitoring for side effects.4 Doxycycline can lead to photosensitivity, which could be difficult to tolerate for active-duty personnel training in sunny climates. Fortunately, uniform regulations and personal protective equipment requirements provide cover for most of the body surfaces aside from the face, which is protected by various forms of covers. If the patient tolerates the medication well without considerable side effects, he/she may be returned to full duty, making doxycycline an acceptable alternative to minocycline in the military population.

Sarecycline

This novel compound is a tetracycline-class antibiotic with a narrower spectrum of activity, with reduced activity against enteric gram-negative bacteria. It has shown efficacy in reducing inflammatory and noninflammatory acne lesions, including lesions on the face, back, and chest. Common adverse side effects are nausea, headache, nasopharyngitis, and vomiting. Vestibular and phototoxic adverse effects were reported in less than 1% of patients.1,8 The US Food and Drug Administration approved sarecycline as a once-daily oral formulation for moderate to severe acne vulgaris, the first new antibiotic to be approved for the disease in the last 40 years. Sarecycline is not mentioned in any US military guidelines with regard to medical readiness and duty status; however, given its lack of vestibular side effects and narrower activity spectrum, it may become another acceptable treatment option in the military population.

Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin is well established as an excellent treatment of acne and stands alone as the only currently available medication that alters the disease course and prevents relapse in many patients. Nearly all patients on isotretinoin experience considerable mucocutaneous dryness, and up to 25% of patients on high-dose isotretinoin develop myalgia.9 Isotretinoin causes serious retinoid embryopathy, requiring all patients to be enrolled in the iPLEDGE program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/iPledgeUI/home.u) and to use 2 methods of contraception during treatment. Although it is uncommon to have notable elevations in lipids and transaminases during treatment with isotretinoin, routine laboratory monitoring generally is performed until the patient reaches steady dosing.

Isotretinoin is not permitted for use in active aircrew members, submariners, or divers. Servicemembers pursuing isotretinoin therapy are removed from their duty and are nondeployable for the entirety of their treatment course and several months after completion.4,5

Photodynamic Therapy

Aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT) has been successfully used in the management of acne.10 In addition to inducing selective damage to sebaceous glands, it has been proposed that PDT also destroys Propionibacterium acnes and reduces keratinocyte shedding and immunologic changes that play key roles in the development of acne.10

A recent randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of ALA-PDT vs adapalene gel plus oral doxycycline for treatment of moderate acne included 46 patients with moderate inflammatory acne.10 Twenty-three participants received 2 sessions (spaced 2 weeks apart) of 20% ALA incubated for 90 minutes before red light irradiation with a fluence of 37 J/cm2, and the other 23 received 100 mg/d of oral doxycycline plus adapalene gel 0.1%. By 6-week follow-up, there was a significantly higher reduction in total lesions within the PDT group (P=.038), which was sustained at the secondary 12-week follow-up (P=.026). There was a 79% total reduction of lesions in the ALA-PDT group vs 67% in the doxycycline plus adapalene group.10

Although some studies have shown promise for PDT as an emerging treatment option for acne, further research is needed. A 2016 systematic review of the related literature determined that although 20% ALA-PDT with red light was more effective than lower concentrations of ALA and also more effective than ALA-PDT with blue light—which offered no additional benefit when compared with blue light alone—high-quality evidence on the use of PDT for acne is lacking overall.11 At the time of the review, there was little certainty as to the usefulness of ALA-PDT with red or blue light as a standard treatment for individuals with moderate to severe acne. A 2019 review by Marson and Baldwin12 echoed this sentiment, recommending more stringently designed studies to elucidate the true role of PDT as a monotherapy or adjunctive treatment of acne.

Pulsed Dye Laser

Pulsed dye laser (PDL) was first shown to be a potential therapy for acne by Seaton et al,13 who conducted a small-scale, randomized, controlled trial with 41 patients, each assigned to either a single PDL treatment or a sham treatment. Patients were re-evaluated at 12 weeks, measuring acne severity by the Leeds revised acne grading system and taking total lesion counts. Acne severity (P=.007) and total lesion counts (P=.023) were significantly improved in the treatment group, with a 53% reduction in total lesion count following a single PDL treatment.13

In 2007, a Spanish study described use of PDL every 4 weeks for a total of 12 weeks in 36 patients with mild to moderate acne. Using lesion counts as their primary outcome measure, the investigators found results similar to those from Seaton et al,13 with a 57% decrease in active lesions.14 Others still have found similar outcomes. A 2009 study of 45 patients with mild to moderate acne compared patients treated with PDL every 2 weeks for 12 weeks to patients receiving either topical therapy or chemical peels with 25% trichloroacetic acid. At 12 weeks, they noted the best results were in the PDL group.15

Karsai et al16 compared PDL as an adjuvant treatment of acne to proven treatment with clindamycin plus benzoyl peroxide gel. Eighty patients were randomized to topical therapy plus PDL or topical therapy alone and were followed at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial treatment. Although both groups showed improvement as measured by inflammatory lesion count and dermatology life quality index, there was no statistically significant difference noted between groups.16

Case Report

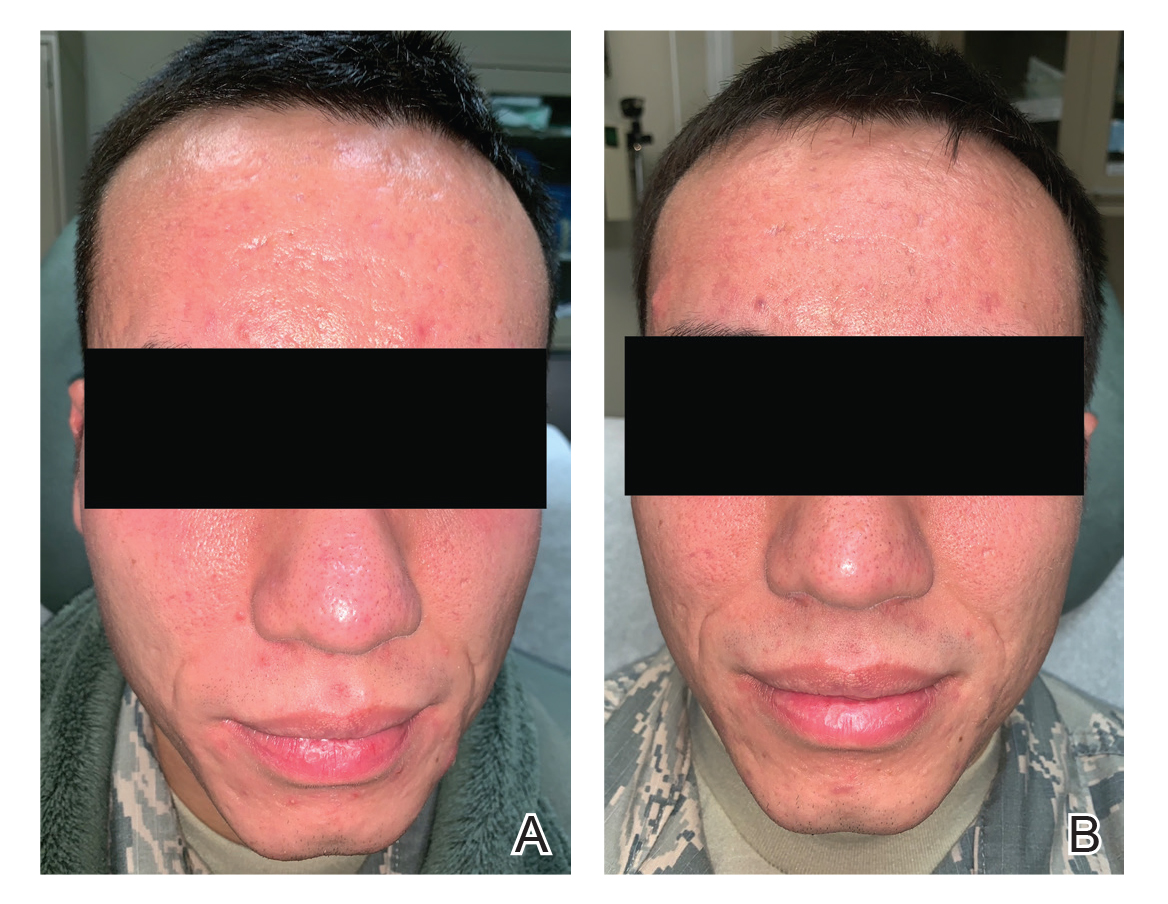

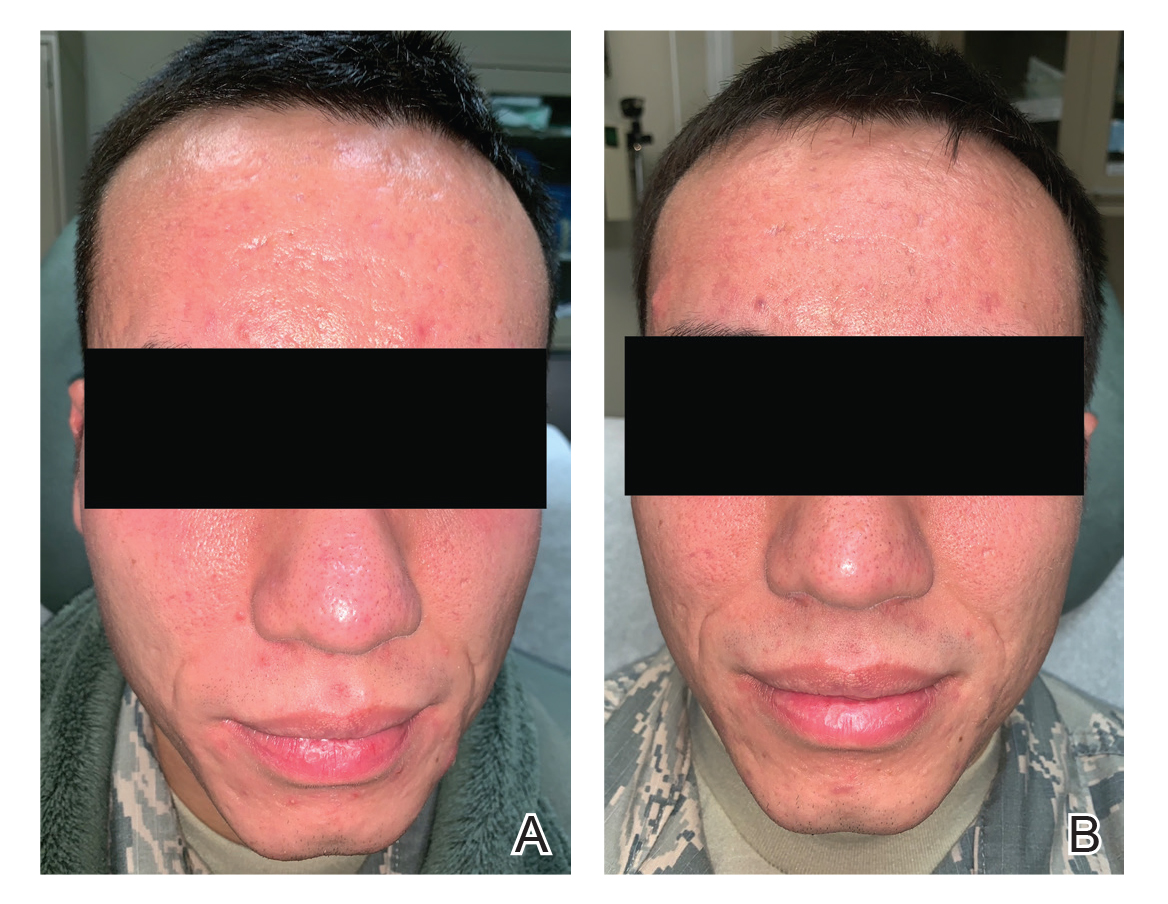

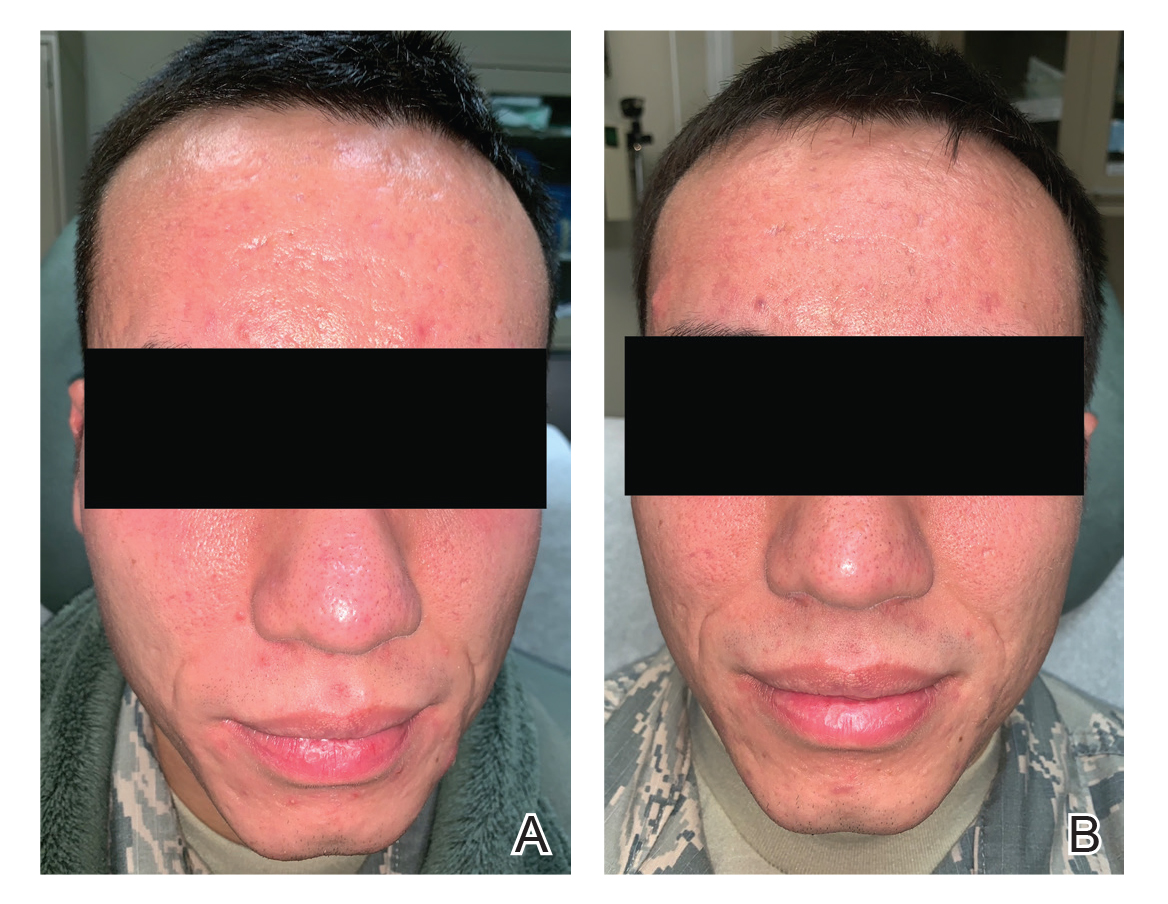

A 24-year-old active-duty male servicemember was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of treatment-resistant nodulocystic scarring acne. Prior to his arrival to dermatology, he had completed 2 weeks of isotretinoin before discontinuation due to notable mood alteration. Following the isotretinoin, he was then switched to doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, which he trialed for 3 months. Even on the antibiotic, the patient continued to develop new pustules and cysts, prompting referral to dermatology for additional treatment options (Figure, A). All of the previous topical and oral medications had been discontinued at the current presentation.

The patient received 3 treatments with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 10 mm; fluence, 7 J/cm2; pulse width, 6 milliseconds) spaced 4 weeks apart. At each treatment, fewer than 10 total inflammatory lesions were treated, including inflammatory papules, pustules, and nodules. Nodular lesions were treated with 2 pulses. After each treatment, the patient reported that all treated lesions resolved within 2 days (Figure, B). Subsequent treated lesions all occurred at previously uninvolved sites.

Final Thoughts

Antibiotic resistance is a known and growing problem throughout the medical community. In 2013, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics than any other specialty.17 Aside from antibiotic stewardship, systemic antibiotics come with various considerations when selecting ideal acne treatment regimens in military populations, as they are either medically disqualifying or lead to temporary grounding status. Numerous guidelines on acne have recommended limiting the use of antibiotics, instead pursuing alternative therapies such as spironolactone, oral contraceptives, or isotretinoin.9,18 Both spironolactone and oral contraceptives work well via antiandrogenic and antisebogenic properties; however, these therapies are limited to female patients only, who make up a minority of patients in the active-duty military setting. Isotretinoin is highly effective in the treatment of acne, but it requires grounding for the entirety of treatment and for months afterward, which comes at great personal and financial costs to servicemembers and their commanders due to limited-duty status and inability to deploy.

Given the operational constraints with isotretinoin and the continual rise of antibiotic resistance, PDL appears to be a safe and effective alternative therapy for acne. In our case, the patient had complete resolution of active inflammatory lesions after each of his treatments. He had no adverse effects and tolerated the treatments well. We report this case here to highlight the use of PDL as an effective therapy for spot treatment in patients limited by personal or operational constraints and as a means to reduce antibiotic use in the face of a growing tide of antibiotic resistance.

- Kircik LH. What’s new in the management of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2019;104:48-52.

- US Department of the Army. Standards of medical fitness. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN8673_AR40_501_FINAL_WEB.pdf. Published June 27, 2019. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- US Department of the Air Force. Medical examinations and standards. http://aangfs.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/AFI-48-123-Medical-Examination-Standards.pdf. Published January 29, 2013. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- US Navy Aeromedical Reference and Waiver Guide. Navy Medicine website. https://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmotc/nami/arwg/Documents/WaiverGuide/Complete_Waiver_Guide.pdf. Published September 4, 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment considerations for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019:103:329-332.

- Gold LS, Dhawan S, Weiss J, et al. A novel topical minocycline foam for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris: results of 2 randomized, double-blind, phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;30:168-177.

- Raoof J, Hooper D, Moore A, et al. FMX101 4% topical minocycline foam for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. Poster presented at: 2018 Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference; October 18-21, 2018; Las Vegas, NV.

- Moore A, Green LJ, Bruce S, et al. Once-daily oral sarecycline 1.5 mg/kg/day is effective for moderate to severe acne vulgaris; results from two identically designed, phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:987-996.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limit systemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Nicklas C, Rubio R, Cardenas C, et al. Comparison of efficacy of aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy vs. adapalene gel plus oral doxycycline for treatment of moderate acne vulgaris—a simple, blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019;35:3-10.

- Barbaric J, Abbott R, Posadzki P, et al. Light therapies for acne [published online September 27, 2016]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007917.pub2.

- Marson JW, Baldwin HE. New concepts, concerns, and creations in acne. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:1-9.

- Seaton ED, Charakida A, Mouser PE, et al. Pulsed-dye laser treatment for inflammatory acne vulgaris: randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2003;362:1347-1352.

- Harto A, Garcia-Morales I, Belmar P, et al. Pulsed dye laser treatment of acne. study of clinical efficacy and mechanism of action. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:415-419.

- Leheta TM. Role of the 585-nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of acne in comparison with other topical therapeutic modalities. J Cosmet Laser Ther Off Publ Eur Soc Laser Dermatol. 2009;11:118-124.

- Karsai S, Schmitt L, Raulin C. The pulsed-dye laser as an adjuvant treatment modality in acne vulgaris: a randomized controlled single-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:395-401.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions—United States. annual report 2013.https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/Annual-ReportSummary_2013.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33.

Acne treatment presents unique challenges in the active-duty military population. Lesions on the face may interfere with proper fit and seal of protective masks and helmets, while those involving the shoulders or back may cause considerable discomfort beneath safety restraints, parachute harnesses, or flak jackets. Therefore, untreated acne may limit servicemembers from performing their assigned duties. Treatments themselves also may be limiting; for instance, aircrew members who are taking oral doxycycline, tetracycline, or erythromycin may be grounded (ie, temporarily removed from duty) during and after therapy to monitor for side effects. Minocycline is considered unacceptable for aviators and is completely restricted for use due to risk for central nervous system side effects. Isotretinoin is restricted in aircrew members, submariners, and divers. If initiated, isotretinoin requires grounding for the entire duration of therapy and up to 3 months following treatment. Normalization of triglyceride levels and slit-lamp ocular examination also must take place prior to return to full duty, which may lead to additional grounding time. Well-established topical and oral treatments not impacting military duty are omitted from this review.

Antibiotics

Minocycline

Minocycline carries a small risk for development of systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune treatment-emergent adverse effects. It has known gastrointestinal tract side effects, and long-term use also can lead to bluish discoloration of the skin.1 Systemic minocycline is restricted in aircrew members due to its risk for central nervous system side effects, including light-headedness, dizziness, and vertigo.2-5

A topical formulation of minocycline recently was developed and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a means to reduce systemic adverse effects. This 4% minocycline foam has thus far been safe and well tolerated, with adverse events reported in less than 1% of study participants.1,6 In addition, topical minocycline was shown in a recent phase 3 study to notably reduce inflammatory lesion counts when compared to control vehicles at as early as 3 weeks.7 Topical minocycline may emerge as a viable treatment option for active-duty servicemembers in the future.

Doxycycline

Doxycycline is not medically disqualifying. Even so, it may still necessitate grounding for a period of time while monitoring for side effects.4 Doxycycline can lead to photosensitivity, which could be difficult to tolerate for active-duty personnel training in sunny climates. Fortunately, uniform regulations and personal protective equipment requirements provide cover for most of the body surfaces aside from the face, which is protected by various forms of covers. If the patient tolerates the medication well without considerable side effects, he/she may be returned to full duty, making doxycycline an acceptable alternative to minocycline in the military population.

Sarecycline

This novel compound is a tetracycline-class antibiotic with a narrower spectrum of activity, with reduced activity against enteric gram-negative bacteria. It has shown efficacy in reducing inflammatory and noninflammatory acne lesions, including lesions on the face, back, and chest. Common adverse side effects are nausea, headache, nasopharyngitis, and vomiting. Vestibular and phototoxic adverse effects were reported in less than 1% of patients.1,8 The US Food and Drug Administration approved sarecycline as a once-daily oral formulation for moderate to severe acne vulgaris, the first new antibiotic to be approved for the disease in the last 40 years. Sarecycline is not mentioned in any US military guidelines with regard to medical readiness and duty status; however, given its lack of vestibular side effects and narrower activity spectrum, it may become another acceptable treatment option in the military population.

Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin is well established as an excellent treatment of acne and stands alone as the only currently available medication that alters the disease course and prevents relapse in many patients. Nearly all patients on isotretinoin experience considerable mucocutaneous dryness, and up to 25% of patients on high-dose isotretinoin develop myalgia.9 Isotretinoin causes serious retinoid embryopathy, requiring all patients to be enrolled in the iPLEDGE program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/iPledgeUI/home.u) and to use 2 methods of contraception during treatment. Although it is uncommon to have notable elevations in lipids and transaminases during treatment with isotretinoin, routine laboratory monitoring generally is performed until the patient reaches steady dosing.

Isotretinoin is not permitted for use in active aircrew members, submariners, or divers. Servicemembers pursuing isotretinoin therapy are removed from their duty and are nondeployable for the entirety of their treatment course and several months after completion.4,5

Photodynamic Therapy

Aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT) has been successfully used in the management of acne.10 In addition to inducing selective damage to sebaceous glands, it has been proposed that PDT also destroys Propionibacterium acnes and reduces keratinocyte shedding and immunologic changes that play key roles in the development of acne.10

A recent randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of ALA-PDT vs adapalene gel plus oral doxycycline for treatment of moderate acne included 46 patients with moderate inflammatory acne.10 Twenty-three participants received 2 sessions (spaced 2 weeks apart) of 20% ALA incubated for 90 minutes before red light irradiation with a fluence of 37 J/cm2, and the other 23 received 100 mg/d of oral doxycycline plus adapalene gel 0.1%. By 6-week follow-up, there was a significantly higher reduction in total lesions within the PDT group (P=.038), which was sustained at the secondary 12-week follow-up (P=.026). There was a 79% total reduction of lesions in the ALA-PDT group vs 67% in the doxycycline plus adapalene group.10

Although some studies have shown promise for PDT as an emerging treatment option for acne, further research is needed. A 2016 systematic review of the related literature determined that although 20% ALA-PDT with red light was more effective than lower concentrations of ALA and also more effective than ALA-PDT with blue light—which offered no additional benefit when compared with blue light alone—high-quality evidence on the use of PDT for acne is lacking overall.11 At the time of the review, there was little certainty as to the usefulness of ALA-PDT with red or blue light as a standard treatment for individuals with moderate to severe acne. A 2019 review by Marson and Baldwin12 echoed this sentiment, recommending more stringently designed studies to elucidate the true role of PDT as a monotherapy or adjunctive treatment of acne.

Pulsed Dye Laser

Pulsed dye laser (PDL) was first shown to be a potential therapy for acne by Seaton et al,13 who conducted a small-scale, randomized, controlled trial with 41 patients, each assigned to either a single PDL treatment or a sham treatment. Patients were re-evaluated at 12 weeks, measuring acne severity by the Leeds revised acne grading system and taking total lesion counts. Acne severity (P=.007) and total lesion counts (P=.023) were significantly improved in the treatment group, with a 53% reduction in total lesion count following a single PDL treatment.13

In 2007, a Spanish study described use of PDL every 4 weeks for a total of 12 weeks in 36 patients with mild to moderate acne. Using lesion counts as their primary outcome measure, the investigators found results similar to those from Seaton et al,13 with a 57% decrease in active lesions.14 Others still have found similar outcomes. A 2009 study of 45 patients with mild to moderate acne compared patients treated with PDL every 2 weeks for 12 weeks to patients receiving either topical therapy or chemical peels with 25% trichloroacetic acid. At 12 weeks, they noted the best results were in the PDL group.15

Karsai et al16 compared PDL as an adjuvant treatment of acne to proven treatment with clindamycin plus benzoyl peroxide gel. Eighty patients were randomized to topical therapy plus PDL or topical therapy alone and were followed at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial treatment. Although both groups showed improvement as measured by inflammatory lesion count and dermatology life quality index, there was no statistically significant difference noted between groups.16

Case Report

A 24-year-old active-duty male servicemember was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of treatment-resistant nodulocystic scarring acne. Prior to his arrival to dermatology, he had completed 2 weeks of isotretinoin before discontinuation due to notable mood alteration. Following the isotretinoin, he was then switched to doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, which he trialed for 3 months. Even on the antibiotic, the patient continued to develop new pustules and cysts, prompting referral to dermatology for additional treatment options (Figure, A). All of the previous topical and oral medications had been discontinued at the current presentation.

The patient received 3 treatments with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 10 mm; fluence, 7 J/cm2; pulse width, 6 milliseconds) spaced 4 weeks apart. At each treatment, fewer than 10 total inflammatory lesions were treated, including inflammatory papules, pustules, and nodules. Nodular lesions were treated with 2 pulses. After each treatment, the patient reported that all treated lesions resolved within 2 days (Figure, B). Subsequent treated lesions all occurred at previously uninvolved sites.

Final Thoughts

Antibiotic resistance is a known and growing problem throughout the medical community. In 2013, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics than any other specialty.17 Aside from antibiotic stewardship, systemic antibiotics come with various considerations when selecting ideal acne treatment regimens in military populations, as they are either medically disqualifying or lead to temporary grounding status. Numerous guidelines on acne have recommended limiting the use of antibiotics, instead pursuing alternative therapies such as spironolactone, oral contraceptives, or isotretinoin.9,18 Both spironolactone and oral contraceptives work well via antiandrogenic and antisebogenic properties; however, these therapies are limited to female patients only, who make up a minority of patients in the active-duty military setting. Isotretinoin is highly effective in the treatment of acne, but it requires grounding for the entirety of treatment and for months afterward, which comes at great personal and financial costs to servicemembers and their commanders due to limited-duty status and inability to deploy.

Given the operational constraints with isotretinoin and the continual rise of antibiotic resistance, PDL appears to be a safe and effective alternative therapy for acne. In our case, the patient had complete resolution of active inflammatory lesions after each of his treatments. He had no adverse effects and tolerated the treatments well. We report this case here to highlight the use of PDL as an effective therapy for spot treatment in patients limited by personal or operational constraints and as a means to reduce antibiotic use in the face of a growing tide of antibiotic resistance.

Acne treatment presents unique challenges in the active-duty military population. Lesions on the face may interfere with proper fit and seal of protective masks and helmets, while those involving the shoulders or back may cause considerable discomfort beneath safety restraints, parachute harnesses, or flak jackets. Therefore, untreated acne may limit servicemembers from performing their assigned duties. Treatments themselves also may be limiting; for instance, aircrew members who are taking oral doxycycline, tetracycline, or erythromycin may be grounded (ie, temporarily removed from duty) during and after therapy to monitor for side effects. Minocycline is considered unacceptable for aviators and is completely restricted for use due to risk for central nervous system side effects. Isotretinoin is restricted in aircrew members, submariners, and divers. If initiated, isotretinoin requires grounding for the entire duration of therapy and up to 3 months following treatment. Normalization of triglyceride levels and slit-lamp ocular examination also must take place prior to return to full duty, which may lead to additional grounding time. Well-established topical and oral treatments not impacting military duty are omitted from this review.

Antibiotics

Minocycline

Minocycline carries a small risk for development of systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune treatment-emergent adverse effects. It has known gastrointestinal tract side effects, and long-term use also can lead to bluish discoloration of the skin.1 Systemic minocycline is restricted in aircrew members due to its risk for central nervous system side effects, including light-headedness, dizziness, and vertigo.2-5

A topical formulation of minocycline recently was developed and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a means to reduce systemic adverse effects. This 4% minocycline foam has thus far been safe and well tolerated, with adverse events reported in less than 1% of study participants.1,6 In addition, topical minocycline was shown in a recent phase 3 study to notably reduce inflammatory lesion counts when compared to control vehicles at as early as 3 weeks.7 Topical minocycline may emerge as a viable treatment option for active-duty servicemembers in the future.

Doxycycline

Doxycycline is not medically disqualifying. Even so, it may still necessitate grounding for a period of time while monitoring for side effects.4 Doxycycline can lead to photosensitivity, which could be difficult to tolerate for active-duty personnel training in sunny climates. Fortunately, uniform regulations and personal protective equipment requirements provide cover for most of the body surfaces aside from the face, which is protected by various forms of covers. If the patient tolerates the medication well without considerable side effects, he/she may be returned to full duty, making doxycycline an acceptable alternative to minocycline in the military population.

Sarecycline

This novel compound is a tetracycline-class antibiotic with a narrower spectrum of activity, with reduced activity against enteric gram-negative bacteria. It has shown efficacy in reducing inflammatory and noninflammatory acne lesions, including lesions on the face, back, and chest. Common adverse side effects are nausea, headache, nasopharyngitis, and vomiting. Vestibular and phototoxic adverse effects were reported in less than 1% of patients.1,8 The US Food and Drug Administration approved sarecycline as a once-daily oral formulation for moderate to severe acne vulgaris, the first new antibiotic to be approved for the disease in the last 40 years. Sarecycline is not mentioned in any US military guidelines with regard to medical readiness and duty status; however, given its lack of vestibular side effects and narrower activity spectrum, it may become another acceptable treatment option in the military population.

Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin is well established as an excellent treatment of acne and stands alone as the only currently available medication that alters the disease course and prevents relapse in many patients. Nearly all patients on isotretinoin experience considerable mucocutaneous dryness, and up to 25% of patients on high-dose isotretinoin develop myalgia.9 Isotretinoin causes serious retinoid embryopathy, requiring all patients to be enrolled in the iPLEDGE program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/iPledgeUI/home.u) and to use 2 methods of contraception during treatment. Although it is uncommon to have notable elevations in lipids and transaminases during treatment with isotretinoin, routine laboratory monitoring generally is performed until the patient reaches steady dosing.

Isotretinoin is not permitted for use in active aircrew members, submariners, or divers. Servicemembers pursuing isotretinoin therapy are removed from their duty and are nondeployable for the entirety of their treatment course and several months after completion.4,5

Photodynamic Therapy

Aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT) has been successfully used in the management of acne.10 In addition to inducing selective damage to sebaceous glands, it has been proposed that PDT also destroys Propionibacterium acnes and reduces keratinocyte shedding and immunologic changes that play key roles in the development of acne.10

A recent randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of ALA-PDT vs adapalene gel plus oral doxycycline for treatment of moderate acne included 46 patients with moderate inflammatory acne.10 Twenty-three participants received 2 sessions (spaced 2 weeks apart) of 20% ALA incubated for 90 minutes before red light irradiation with a fluence of 37 J/cm2, and the other 23 received 100 mg/d of oral doxycycline plus adapalene gel 0.1%. By 6-week follow-up, there was a significantly higher reduction in total lesions within the PDT group (P=.038), which was sustained at the secondary 12-week follow-up (P=.026). There was a 79% total reduction of lesions in the ALA-PDT group vs 67% in the doxycycline plus adapalene group.10

Although some studies have shown promise for PDT as an emerging treatment option for acne, further research is needed. A 2016 systematic review of the related literature determined that although 20% ALA-PDT with red light was more effective than lower concentrations of ALA and also more effective than ALA-PDT with blue light—which offered no additional benefit when compared with blue light alone—high-quality evidence on the use of PDT for acne is lacking overall.11 At the time of the review, there was little certainty as to the usefulness of ALA-PDT with red or blue light as a standard treatment for individuals with moderate to severe acne. A 2019 review by Marson and Baldwin12 echoed this sentiment, recommending more stringently designed studies to elucidate the true role of PDT as a monotherapy or adjunctive treatment of acne.

Pulsed Dye Laser

Pulsed dye laser (PDL) was first shown to be a potential therapy for acne by Seaton et al,13 who conducted a small-scale, randomized, controlled trial with 41 patients, each assigned to either a single PDL treatment or a sham treatment. Patients were re-evaluated at 12 weeks, measuring acne severity by the Leeds revised acne grading system and taking total lesion counts. Acne severity (P=.007) and total lesion counts (P=.023) were significantly improved in the treatment group, with a 53% reduction in total lesion count following a single PDL treatment.13

In 2007, a Spanish study described use of PDL every 4 weeks for a total of 12 weeks in 36 patients with mild to moderate acne. Using lesion counts as their primary outcome measure, the investigators found results similar to those from Seaton et al,13 with a 57% decrease in active lesions.14 Others still have found similar outcomes. A 2009 study of 45 patients with mild to moderate acne compared patients treated with PDL every 2 weeks for 12 weeks to patients receiving either topical therapy or chemical peels with 25% trichloroacetic acid. At 12 weeks, they noted the best results were in the PDL group.15

Karsai et al16 compared PDL as an adjuvant treatment of acne to proven treatment with clindamycin plus benzoyl peroxide gel. Eighty patients were randomized to topical therapy plus PDL or topical therapy alone and were followed at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial treatment. Although both groups showed improvement as measured by inflammatory lesion count and dermatology life quality index, there was no statistically significant difference noted between groups.16

Case Report

A 24-year-old active-duty male servicemember was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of treatment-resistant nodulocystic scarring acne. Prior to his arrival to dermatology, he had completed 2 weeks of isotretinoin before discontinuation due to notable mood alteration. Following the isotretinoin, he was then switched to doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, which he trialed for 3 months. Even on the antibiotic, the patient continued to develop new pustules and cysts, prompting referral to dermatology for additional treatment options (Figure, A). All of the previous topical and oral medications had been discontinued at the current presentation.

The patient received 3 treatments with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 10 mm; fluence, 7 J/cm2; pulse width, 6 milliseconds) spaced 4 weeks apart. At each treatment, fewer than 10 total inflammatory lesions were treated, including inflammatory papules, pustules, and nodules. Nodular lesions were treated with 2 pulses. After each treatment, the patient reported that all treated lesions resolved within 2 days (Figure, B). Subsequent treated lesions all occurred at previously uninvolved sites.

Final Thoughts

Antibiotic resistance is a known and growing problem throughout the medical community. In 2013, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics than any other specialty.17 Aside from antibiotic stewardship, systemic antibiotics come with various considerations when selecting ideal acne treatment regimens in military populations, as they are either medically disqualifying or lead to temporary grounding status. Numerous guidelines on acne have recommended limiting the use of antibiotics, instead pursuing alternative therapies such as spironolactone, oral contraceptives, or isotretinoin.9,18 Both spironolactone and oral contraceptives work well via antiandrogenic and antisebogenic properties; however, these therapies are limited to female patients only, who make up a minority of patients in the active-duty military setting. Isotretinoin is highly effective in the treatment of acne, but it requires grounding for the entirety of treatment and for months afterward, which comes at great personal and financial costs to servicemembers and their commanders due to limited-duty status and inability to deploy.

Given the operational constraints with isotretinoin and the continual rise of antibiotic resistance, PDL appears to be a safe and effective alternative therapy for acne. In our case, the patient had complete resolution of active inflammatory lesions after each of his treatments. He had no adverse effects and tolerated the treatments well. We report this case here to highlight the use of PDL as an effective therapy for spot treatment in patients limited by personal or operational constraints and as a means to reduce antibiotic use in the face of a growing tide of antibiotic resistance.

- Kircik LH. What’s new in the management of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2019;104:48-52.

- US Department of the Army. Standards of medical fitness. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN8673_AR40_501_FINAL_WEB.pdf. Published June 27, 2019. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- US Department of the Air Force. Medical examinations and standards. http://aangfs.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/AFI-48-123-Medical-Examination-Standards.pdf. Published January 29, 2013. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- US Navy Aeromedical Reference and Waiver Guide. Navy Medicine website. https://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmotc/nami/arwg/Documents/WaiverGuide/Complete_Waiver_Guide.pdf. Published September 4, 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment considerations for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019:103:329-332.

- Gold LS, Dhawan S, Weiss J, et al. A novel topical minocycline foam for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris: results of 2 randomized, double-blind, phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;30:168-177.

- Raoof J, Hooper D, Moore A, et al. FMX101 4% topical minocycline foam for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. Poster presented at: 2018 Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference; October 18-21, 2018; Las Vegas, NV.

- Moore A, Green LJ, Bruce S, et al. Once-daily oral sarecycline 1.5 mg/kg/day is effective for moderate to severe acne vulgaris; results from two identically designed, phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:987-996.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limit systemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Nicklas C, Rubio R, Cardenas C, et al. Comparison of efficacy of aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy vs. adapalene gel plus oral doxycycline for treatment of moderate acne vulgaris—a simple, blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019;35:3-10.

- Barbaric J, Abbott R, Posadzki P, et al. Light therapies for acne [published online September 27, 2016]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007917.pub2.

- Marson JW, Baldwin HE. New concepts, concerns, and creations in acne. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:1-9.

- Seaton ED, Charakida A, Mouser PE, et al. Pulsed-dye laser treatment for inflammatory acne vulgaris: randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2003;362:1347-1352.

- Harto A, Garcia-Morales I, Belmar P, et al. Pulsed dye laser treatment of acne. study of clinical efficacy and mechanism of action. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:415-419.

- Leheta TM. Role of the 585-nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of acne in comparison with other topical therapeutic modalities. J Cosmet Laser Ther Off Publ Eur Soc Laser Dermatol. 2009;11:118-124.

- Karsai S, Schmitt L, Raulin C. The pulsed-dye laser as an adjuvant treatment modality in acne vulgaris: a randomized controlled single-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:395-401.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions—United States. annual report 2013.https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/Annual-ReportSummary_2013.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33.

- Kircik LH. What’s new in the management of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2019;104:48-52.

- US Department of the Army. Standards of medical fitness. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN8673_AR40_501_FINAL_WEB.pdf. Published June 27, 2019. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- US Department of the Air Force. Medical examinations and standards. http://aangfs.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/AFI-48-123-Medical-Examination-Standards.pdf. Published January 29, 2013. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- US Navy Aeromedical Reference and Waiver Guide. Navy Medicine website. https://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmotc/nami/arwg/Documents/WaiverGuide/Complete_Waiver_Guide.pdf. Published September 4, 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment considerations for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019:103:329-332.

- Gold LS, Dhawan S, Weiss J, et al. A novel topical minocycline foam for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris: results of 2 randomized, double-blind, phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;30:168-177.

- Raoof J, Hooper D, Moore A, et al. FMX101 4% topical minocycline foam for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. Poster presented at: 2018 Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference; October 18-21, 2018; Las Vegas, NV.

- Moore A, Green LJ, Bruce S, et al. Once-daily oral sarecycline 1.5 mg/kg/day is effective for moderate to severe acne vulgaris; results from two identically designed, phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:987-996.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limit systemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Nicklas C, Rubio R, Cardenas C, et al. Comparison of efficacy of aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy vs. adapalene gel plus oral doxycycline for treatment of moderate acne vulgaris—a simple, blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019;35:3-10.

- Barbaric J, Abbott R, Posadzki P, et al. Light therapies for acne [published online September 27, 2016]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007917.pub2.

- Marson JW, Baldwin HE. New concepts, concerns, and creations in acne. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:1-9.

- Seaton ED, Charakida A, Mouser PE, et al. Pulsed-dye laser treatment for inflammatory acne vulgaris: randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2003;362:1347-1352.

- Harto A, Garcia-Morales I, Belmar P, et al. Pulsed dye laser treatment of acne. study of clinical efficacy and mechanism of action. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:415-419.

- Leheta TM. Role of the 585-nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of acne in comparison with other topical therapeutic modalities. J Cosmet Laser Ther Off Publ Eur Soc Laser Dermatol. 2009;11:118-124.

- Karsai S, Schmitt L, Raulin C. The pulsed-dye laser as an adjuvant treatment modality in acne vulgaris: a randomized controlled single-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:395-401.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions—United States. annual report 2013.https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/Annual-ReportSummary_2013.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33.

Practice Points

- Acne is a common disease that may cause considerable physical and psychological morbidity. Numerous therapies are available, each with their respective risks and benefits.

- Military servicemembers face unique challenges in the management of acne due to operational and medical readiness considerations.

- Less conventional treatments such as photodynamic therapy and pulsed dye laser may be available to military servicemembers.

- Pulsed dye laser is an effective alternative treatment of acne, especially in an age of growing antibiotic resistance.

Acne Keloidalis Nuchae in the Armed Forces

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory disorder most commonly involving the occipital scalp and posterior neck characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques. If left untreated, this condition may progress to scarring alopecia. It primarily affects males of African descent, but it also may occur in females and in other ethnic groups. Although the exact underlying pathogenesis is unclear, close haircuts and chronic mechanical irritation to the posterior neck and scalp are known inciting factors. For this reason, AKN disproportionately affects active-duty military servicemembers who are held to strict grooming standards. The US Military maintains these grooming standards to ensure uniformity, self-discipline, and serviceability in operational settings.1 Regulations dictate short tapered hair, particularly on the back of the neck, which can require weekly to biweekly haircuts to maintain.1-5

First-line treatment of AKN is prevention by avoiding short haircuts and other forms of mechanical irritation.1,6,7 However, there are considerable barriers to this strategy within the military due to uniform regulations as well as personal appearance and grooming standards. Early identification and treatment are of utmost importance in managing AKN in the military population to ensure reduction of morbidity, prevention of late-stage disease, and continued fitness for duty. This article reviews the clinical features, epidemiology, and treatments available for management of AKN, with a special focus on the active-duty military population.

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques on the posterior neck and occipital scalp.6 Also known as folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, AKN is seen primarily in men of African descent, though cases also have been reported in females and in a few other ethnic groups.6,7 In black males, the AKN prevalence worldwide ranges from 0.5% to 13.6%. The male to female ratio is 20 to 1.7 Although the exact cause is unknown, AKN appears to develop from chronic irritation and inflammation following localized skin injury and/or trauma. Chronic irritation from close-shaved haircuts, tight-fitting shirt collars, caps, and helmets have all been implicated as considerable risk factors.6-8

Symptoms generally develop hours to days following a close haircut and begin with the early formation of inflamed irritated papules and notable erythema.6,7 These papules may become secondarily infected and develop into pustules and/or abscesses, especially in cases in which the affected individual continues to have the hair shaved. Continued use of shared razors increases the risk for secondary infection and also raises the concern for transmission of blood-borne pathogens, as AKN lesions are quick to bleed with minor trauma.7

Over time, chronic inflammation and continued trauma of the AKN papules leads to widespread fibrosis and scar formation, as the papules coalesce into larger plaques and nodules. If left untreated, these later stages of disease can progress to chronic scarring alopecia.6

Prevention

In the general population, first-line therapy of AKN is preventative. The goal is to break the cycle of chronic inflammation, thereby preventing the development of additional lesions and subsequent scarring.7 Patients should be encouraged to avoid frequent haircuts, close shaves, hats, helmets, and tight shirt collars.6-8

A 2017 cross-sectional study by Adotama et al9 investigated recognition and management of AKN in predominantly black barbershops in an urban setting. Fifty barbers from barbershops in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, were enrolled and interviewed for the study. Of these barbers, only 44% (22/50) were able to properly identify AKN from a photograph. Although the vast majority (94% [47/50]) were aware that razor use would aggravate the condition, only 46% (23/50) reported avoidance of cutting hair for clients with active AKN.9 This study, while limited by its small sample size, showed that many barbers may be unaware of AKN and therefore unknowingly contribute to the disease process by performing haircuts on actively inflamed scalps. For this reason, it is important to educate patients about their condition and strongly recommend lifestyle and hairstyle modifications in the management of their disease.

Acne keloidalis nuchae that is severe enough to interfere with the proper use and wear of military equipment (eg, Kevlar helmets) or maintenance of regulation grooming standards does not meet military admission standards.10,11 However, mild undiagnosed cases may be overlooked during entrance physical examinations, while many servicemembers develop AKN after entering the military.10 For these individuals, long-term avoidance of haircuts is not a realistic or obtainable therapeutic option.

Treatment

Topical Therapy

Early mild to moderate cases of AKN—papules less than 3 mm, no nodules present—may be treated with potent topical steroids. Studies have shown 2-week alternating cycles of high-potency topical steroids (2 weeks of twice-daily application followed by 2 weeks without application) for 8 to 12 weeks to be effective in reducing AKN lesions.8,12 Topical clindamycin also may be added and has demonstrated efficacy particularly when pustules are present.7,8

Intralesional Steroids

For moderate cases of AKN—papules more than 3 mm, plaques, and nodules—intralesional steroid injections may be considered. Triamcinolone may be used at a dose of 5 to 40 mg/mL administered at 4-week intervals.7 More concentrated doses will produce faster responses but also carry the known risk of side effects such as hypopigmentation in darker-skinned individuals and skin atrophy.

Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapy with oral antibiotics may be warranted as an adjunct to mild to moderate cases of AKN or in cases with clear evidence of secondary infection. Long-term tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline and doxycycline, may be used concurrently with topical and/or intralesional steroids.6,7 Their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects are useful in controlling secondary infections and reducing overall chronic inflammation.

When selecting an appropriate antibiotic for long-term use in active-duty military patients, it is important to consider their effects on duty status. Doxycycline is preferred for active-duty servicemembers because it is not duty limiting or medically disqualifying.10,13-15 However, minocycline, is restricted for use in aviators and aircrew members due to the risk for central nervous system side effects, which may include light-headedness, dizziness, and vertigo.

UV Light Therapy

UV radiation has known anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and antifibrotic effects and commonly is used in the treatment of many dermatologic conditions.16 Within the last decade, targeted UVB (tUVB) radiation has shown promise as an effective alternative therapy for AKN. In 2014, Okoye et al16 conducted a prospective, randomized, split-scalp study in 11 patients with AKN. Each patient underwent treatment with a tUVB device (with peaks at 303 and 313 nm) to a randomly selected side of the scalp 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. Significant reductions in lesion count were seen on the treated side after 8 (P=.03) and 16 weeks (P=.04), with no change noted on the control side. Aside from objective lesion counts, patients completed questionnaires (n=6) regarding their treatment outcomes. Notably, 83.3% (5/6) reported marked improvement in their condition. Aside from mild transient burning and erythema of the treated area, no serious side effects were reported.16

Targeted UVB phototherapy has limited utility in an operational setting due to accessibility and operational tempo. Phototherapy units typically are available only at commands in close proximity to large medical treatment facilities. Further, the vast majority of servicemembers have duty hours that are not amenable to multiple treatment sessions per week for several months. For servicemembers in administrative roles or serving in garrison or shore billets, tUVB or narrowband UV phototherapy may be viable treatment options.

Laser Therapy

Various lasers have been used to treat AKN, including the CO2 laser, pulsed dye laser, 810-nm diode laser, and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6 Kantor et al17 utilized a CO2 laser with a focused beam for surgical excision of a late-stage AKN case as early as 1986. In these patients, it was demonstrated that focused CO2 laser could be used to remove fibrotic lesions in an outpatient setting with only local anesthesia. Although only 8 patients were treated in this report, no relapses occurred.17

CO2 laser evaporation using the unfocused beam setting with 130 to 150 J/cm2 has been less successful, with relapses reported in multiple cases.6 Dragoni et al18 attempted treatment with a 595-nm pulsed dye laser with 6.5-J/cm2 fluence and 0.5-millisecond pulse but faced similar results, with lesions returning within 1 month.

There have been numerous reports of clinical improvement of AKN with the use of the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,19 Esmat et al19 treated 16 patients with a fluence of 35 to 45 J/cm2 and pulse duration of 10 to 30 milliseconds adjusted to skin type and hair thickness. An overall 82% reduction in lesion count was observed after 5 treatment sessions. Biopsies following the treatment course demonstrated a significant reduction in papule and plaque count (P=.001 and P=.011, respectively), and no clinical recurrences were noted at 12 months posttreatment.19 Similarly, Woo et al20 conducted a single-blinded, randomized, controlled trial to assess the efficacy of the Nd:YAG laser in combination with topical corticosteroid therapy vs topical corticosteroid monotherapy. Of the 20 patients treated, there was a statistically significant improvement in patients with papule-only AKN who received the laser and topical combination treatment (P=.031).20

Laser therapy may be an available treatment option for military servicemembers stationed within close proximity to military treatment facilities, with the Nd:YAG laser typically having the widest availability. Although laser therapy may be effective in early stages of disease, servicemembers would have to be amenable to limitation of future hair growth in the treated areas.

Surgical Excision

Surgical excision may be considered for large, extensive, disfiguring, and/or refractory lesions. Excision is a safe and effective method to remove tender, inflamed, keloidlike masses. Techniques for excision include electrosurgical excision with secondary intention healing, excision of a horizontal ellipse involving the posterior hairline with either primary closure or secondary intention healing, and use of a semilunar tissue expander prior to excision and closure.6 Regardless of the technique, it is important to ensure that affected tissue is excised at a depth that includes the base of the hair follicles to prevent recurrence.21

Final Thoughts

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory disease that causes considerable morbidity and can lead to chronic infection, alopecia, and disfigurement of the occipital scalp and posterior neck. Although easily preventable through the avoidance of mechanical trauma, irritation, and frequent short haircuts, the active-duty military population is restricted in their preventive measures due to current grooming and uniform standards. In this population, early identification and treatment are necessary to manage the disease to reduce patient morbidity and ensure continued operational and medical readiness. Topical and intralesional steroids may be used in mild to moderate cases. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics may be added to the treatment regimen in cases of secondary bacterial infection. For more severe refractory cases, laser therapy or complete surgical excision may be warranted.

- Weiss AN, Arballo OM, Miletta NR, et al. Military grooming standards and their impact on skin diseases of the head and neck. Cutis. 2018;102:328, 331-333.

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Washington, DC: Department of the Army; 2017. https://history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/docs/AR670-1.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- U.S. Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. Quantico, VA: United States Marine Corps, 2018. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- Grooming standards. In: US Department of the Navy. United States Navy Uniform Regulations: NAVPERS 15665I. https://www.public.navy.mil/bupers-npc/support/uniforms/uniformregulations/chapter2/Pages/2201PersonalAppearance.aspx. Updated May 2019. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Washington, DC: Department of the Air Force, 2019. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- Maranda EL, Simmons BJ, Nguyen AH, et al. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae: a systemic review of the literature. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:362-378.

- Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483-489.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191.

- Adotama P, Tinker D, Mitchell K, et al. Barber knowledge and recommendations regarding pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae in an urban setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;12:1325.

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment considerations for US military members with sin disease. Cutis. 2019;6:329-332.

- Medical standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction Into the Military Services (DoD Instruction 6130.03). Washington, DC: Department of Defense; May 6, 2018. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003p.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- Callender VD, Young CM, Haverstock CL, et al. An open label study of clobetasol propionate 0.05% and betamethasone valerate 0.12% foams in treatment of mild to moderate acne keloidalis. Cutis. 2005;75:317-321.

- US Department of the Army. Standards of medical fitness. https://www.qmo.amedd.army.mil/diabetes/AR40_5012011.pdf. Published December 14, 2007. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- US Department of the Air Force. Medical examinations and standards. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_sg/publication/afi48-123/afi48-123.pdf. Published November 5, 2013. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- US Navy Aeromedical Reference and Waiver Guide. https://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmotc/nami/arwg/Documents/WaiverGuide/Complete_Waiver_Guide.pdf. Published September 4, 2019. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- Okoye GA, Rainer BM, Leung SG, et al. Improving acne keloidalis nuchae with targeted ultraviolet B treatment: a prospective, randomized split-scalp study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;17:1156-1163.

- Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2, pt 1):263-267.

- 18. Dragoni F, Bassi A, Cannarozzo G, et al. Successful treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae resistant to conventional therapy with 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:231-232.

- Esmat SM, Hay RMA, Zeid OMA, et al. The efficacy of laser assisted hair removal in the treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae; a pilot study. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:645-650.

- Woo DK, Treyger G, Henderson M, et al. Prospective controlled trial for the treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with a long-pulsed neodymium-doped yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:236-238.

- Beckett N, Lawson C, Cohen G. Electrosurgical excision of acne keloidalis nuchae with secondary intention healing. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:36-39.

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory disorder most commonly involving the occipital scalp and posterior neck characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques. If left untreated, this condition may progress to scarring alopecia. It primarily affects males of African descent, but it also may occur in females and in other ethnic groups. Although the exact underlying pathogenesis is unclear, close haircuts and chronic mechanical irritation to the posterior neck and scalp are known inciting factors. For this reason, AKN disproportionately affects active-duty military servicemembers who are held to strict grooming standards. The US Military maintains these grooming standards to ensure uniformity, self-discipline, and serviceability in operational settings.1 Regulations dictate short tapered hair, particularly on the back of the neck, which can require weekly to biweekly haircuts to maintain.1-5

First-line treatment of AKN is prevention by avoiding short haircuts and other forms of mechanical irritation.1,6,7 However, there are considerable barriers to this strategy within the military due to uniform regulations as well as personal appearance and grooming standards. Early identification and treatment are of utmost importance in managing AKN in the military population to ensure reduction of morbidity, prevention of late-stage disease, and continued fitness for duty. This article reviews the clinical features, epidemiology, and treatments available for management of AKN, with a special focus on the active-duty military population.

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques on the posterior neck and occipital scalp.6 Also known as folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, AKN is seen primarily in men of African descent, though cases also have been reported in females and in a few other ethnic groups.6,7 In black males, the AKN prevalence worldwide ranges from 0.5% to 13.6%. The male to female ratio is 20 to 1.7 Although the exact cause is unknown, AKN appears to develop from chronic irritation and inflammation following localized skin injury and/or trauma. Chronic irritation from close-shaved haircuts, tight-fitting shirt collars, caps, and helmets have all been implicated as considerable risk factors.6-8

Symptoms generally develop hours to days following a close haircut and begin with the early formation of inflamed irritated papules and notable erythema.6,7 These papules may become secondarily infected and develop into pustules and/or abscesses, especially in cases in which the affected individual continues to have the hair shaved. Continued use of shared razors increases the risk for secondary infection and also raises the concern for transmission of blood-borne pathogens, as AKN lesions are quick to bleed with minor trauma.7

Over time, chronic inflammation and continued trauma of the AKN papules leads to widespread fibrosis and scar formation, as the papules coalesce into larger plaques and nodules. If left untreated, these later stages of disease can progress to chronic scarring alopecia.6

Prevention

In the general population, first-line therapy of AKN is preventative. The goal is to break the cycle of chronic inflammation, thereby preventing the development of additional lesions and subsequent scarring.7 Patients should be encouraged to avoid frequent haircuts, close shaves, hats, helmets, and tight shirt collars.6-8

A 2017 cross-sectional study by Adotama et al9 investigated recognition and management of AKN in predominantly black barbershops in an urban setting. Fifty barbers from barbershops in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, were enrolled and interviewed for the study. Of these barbers, only 44% (22/50) were able to properly identify AKN from a photograph. Although the vast majority (94% [47/50]) were aware that razor use would aggravate the condition, only 46% (23/50) reported avoidance of cutting hair for clients with active AKN.9 This study, while limited by its small sample size, showed that many barbers may be unaware of AKN and therefore unknowingly contribute to the disease process by performing haircuts on actively inflamed scalps. For this reason, it is important to educate patients about their condition and strongly recommend lifestyle and hairstyle modifications in the management of their disease.

Acne keloidalis nuchae that is severe enough to interfere with the proper use and wear of military equipment (eg, Kevlar helmets) or maintenance of regulation grooming standards does not meet military admission standards.10,11 However, mild undiagnosed cases may be overlooked during entrance physical examinations, while many servicemembers develop AKN after entering the military.10 For these individuals, long-term avoidance of haircuts is not a realistic or obtainable therapeutic option.

Treatment

Topical Therapy

Early mild to moderate cases of AKN—papules less than 3 mm, no nodules present—may be treated with potent topical steroids. Studies have shown 2-week alternating cycles of high-potency topical steroids (2 weeks of twice-daily application followed by 2 weeks without application) for 8 to 12 weeks to be effective in reducing AKN lesions.8,12 Topical clindamycin also may be added and has demonstrated efficacy particularly when pustules are present.7,8

Intralesional Steroids

For moderate cases of AKN—papules more than 3 mm, plaques, and nodules—intralesional steroid injections may be considered. Triamcinolone may be used at a dose of 5 to 40 mg/mL administered at 4-week intervals.7 More concentrated doses will produce faster responses but also carry the known risk of side effects such as hypopigmentation in darker-skinned individuals and skin atrophy.

Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapy with oral antibiotics may be warranted as an adjunct to mild to moderate cases of AKN or in cases with clear evidence of secondary infection. Long-term tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline and doxycycline, may be used concurrently with topical and/or intralesional steroids.6,7 Their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects are useful in controlling secondary infections and reducing overall chronic inflammation.

When selecting an appropriate antibiotic for long-term use in active-duty military patients, it is important to consider their effects on duty status. Doxycycline is preferred for active-duty servicemembers because it is not duty limiting or medically disqualifying.10,13-15 However, minocycline, is restricted for use in aviators and aircrew members due to the risk for central nervous system side effects, which may include light-headedness, dizziness, and vertigo.

UV Light Therapy

UV radiation has known anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and antifibrotic effects and commonly is used in the treatment of many dermatologic conditions.16 Within the last decade, targeted UVB (tUVB) radiation has shown promise as an effective alternative therapy for AKN. In 2014, Okoye et al16 conducted a prospective, randomized, split-scalp study in 11 patients with AKN. Each patient underwent treatment with a tUVB device (with peaks at 303 and 313 nm) to a randomly selected side of the scalp 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. Significant reductions in lesion count were seen on the treated side after 8 (P=.03) and 16 weeks (P=.04), with no change noted on the control side. Aside from objective lesion counts, patients completed questionnaires (n=6) regarding their treatment outcomes. Notably, 83.3% (5/6) reported marked improvement in their condition. Aside from mild transient burning and erythema of the treated area, no serious side effects were reported.16

Targeted UVB phototherapy has limited utility in an operational setting due to accessibility and operational tempo. Phototherapy units typically are available only at commands in close proximity to large medical treatment facilities. Further, the vast majority of servicemembers have duty hours that are not amenable to multiple treatment sessions per week for several months. For servicemembers in administrative roles or serving in garrison or shore billets, tUVB or narrowband UV phototherapy may be viable treatment options.

Laser Therapy

Various lasers have been used to treat AKN, including the CO2 laser, pulsed dye laser, 810-nm diode laser, and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6 Kantor et al17 utilized a CO2 laser with a focused beam for surgical excision of a late-stage AKN case as early as 1986. In these patients, it was demonstrated that focused CO2 laser could be used to remove fibrotic lesions in an outpatient setting with only local anesthesia. Although only 8 patients were treated in this report, no relapses occurred.17

CO2 laser evaporation using the unfocused beam setting with 130 to 150 J/cm2 has been less successful, with relapses reported in multiple cases.6 Dragoni et al18 attempted treatment with a 595-nm pulsed dye laser with 6.5-J/cm2 fluence and 0.5-millisecond pulse but faced similar results, with lesions returning within 1 month.

There have been numerous reports of clinical improvement of AKN with the use of the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,19 Esmat et al19 treated 16 patients with a fluence of 35 to 45 J/cm2 and pulse duration of 10 to 30 milliseconds adjusted to skin type and hair thickness. An overall 82% reduction in lesion count was observed after 5 treatment sessions. Biopsies following the treatment course demonstrated a significant reduction in papule and plaque count (P=.001 and P=.011, respectively), and no clinical recurrences were noted at 12 months posttreatment.19 Similarly, Woo et al20 conducted a single-blinded, randomized, controlled trial to assess the efficacy of the Nd:YAG laser in combination with topical corticosteroid therapy vs topical corticosteroid monotherapy. Of the 20 patients treated, there was a statistically significant improvement in patients with papule-only AKN who received the laser and topical combination treatment (P=.031).20

Laser therapy may be an available treatment option for military servicemembers stationed within close proximity to military treatment facilities, with the Nd:YAG laser typically having the widest availability. Although laser therapy may be effective in early stages of disease, servicemembers would have to be amenable to limitation of future hair growth in the treated areas.

Surgical Excision

Surgical excision may be considered for large, extensive, disfiguring, and/or refractory lesions. Excision is a safe and effective method to remove tender, inflamed, keloidlike masses. Techniques for excision include electrosurgical excision with secondary intention healing, excision of a horizontal ellipse involving the posterior hairline with either primary closure or secondary intention healing, and use of a semilunar tissue expander prior to excision and closure.6 Regardless of the technique, it is important to ensure that affected tissue is excised at a depth that includes the base of the hair follicles to prevent recurrence.21

Final Thoughts

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory disease that causes considerable morbidity and can lead to chronic infection, alopecia, and disfigurement of the occipital scalp and posterior neck. Although easily preventable through the avoidance of mechanical trauma, irritation, and frequent short haircuts, the active-duty military population is restricted in their preventive measures due to current grooming and uniform standards. In this population, early identification and treatment are necessary to manage the disease to reduce patient morbidity and ensure continued operational and medical readiness. Topical and intralesional steroids may be used in mild to moderate cases. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics may be added to the treatment regimen in cases of secondary bacterial infection. For more severe refractory cases, laser therapy or complete surgical excision may be warranted.

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory disorder most commonly involving the occipital scalp and posterior neck characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques. If left untreated, this condition may progress to scarring alopecia. It primarily affects males of African descent, but it also may occur in females and in other ethnic groups. Although the exact underlying pathogenesis is unclear, close haircuts and chronic mechanical irritation to the posterior neck and scalp are known inciting factors. For this reason, AKN disproportionately affects active-duty military servicemembers who are held to strict grooming standards. The US Military maintains these grooming standards to ensure uniformity, self-discipline, and serviceability in operational settings.1 Regulations dictate short tapered hair, particularly on the back of the neck, which can require weekly to biweekly haircuts to maintain.1-5

First-line treatment of AKN is prevention by avoiding short haircuts and other forms of mechanical irritation.1,6,7 However, there are considerable barriers to this strategy within the military due to uniform regulations as well as personal appearance and grooming standards. Early identification and treatment are of utmost importance in managing AKN in the military population to ensure reduction of morbidity, prevention of late-stage disease, and continued fitness for duty. This article reviews the clinical features, epidemiology, and treatments available for management of AKN, with a special focus on the active-duty military population.

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques on the posterior neck and occipital scalp.6 Also known as folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, AKN is seen primarily in men of African descent, though cases also have been reported in females and in a few other ethnic groups.6,7 In black males, the AKN prevalence worldwide ranges from 0.5% to 13.6%. The male to female ratio is 20 to 1.7 Although the exact cause is unknown, AKN appears to develop from chronic irritation and inflammation following localized skin injury and/or trauma. Chronic irritation from close-shaved haircuts, tight-fitting shirt collars, caps, and helmets have all been implicated as considerable risk factors.6-8

Symptoms generally develop hours to days following a close haircut and begin with the early formation of inflamed irritated papules and notable erythema.6,7 These papules may become secondarily infected and develop into pustules and/or abscesses, especially in cases in which the affected individual continues to have the hair shaved. Continued use of shared razors increases the risk for secondary infection and also raises the concern for transmission of blood-borne pathogens, as AKN lesions are quick to bleed with minor trauma.7

Over time, chronic inflammation and continued trauma of the AKN papules leads to widespread fibrosis and scar formation, as the papules coalesce into larger plaques and nodules. If left untreated, these later stages of disease can progress to chronic scarring alopecia.6

Prevention

In the general population, first-line therapy of AKN is preventative. The goal is to break the cycle of chronic inflammation, thereby preventing the development of additional lesions and subsequent scarring.7 Patients should be encouraged to avoid frequent haircuts, close shaves, hats, helmets, and tight shirt collars.6-8

A 2017 cross-sectional study by Adotama et al9 investigated recognition and management of AKN in predominantly black barbershops in an urban setting. Fifty barbers from barbershops in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, were enrolled and interviewed for the study. Of these barbers, only 44% (22/50) were able to properly identify AKN from a photograph. Although the vast majority (94% [47/50]) were aware that razor use would aggravate the condition, only 46% (23/50) reported avoidance of cutting hair for clients with active AKN.9 This study, while limited by its small sample size, showed that many barbers may be unaware of AKN and therefore unknowingly contribute to the disease process by performing haircuts on actively inflamed scalps. For this reason, it is important to educate patients about their condition and strongly recommend lifestyle and hairstyle modifications in the management of their disease.