User login

Psoriasiform Drug Eruption Secondary to Sorafenib: Case Series and Review of the Literature

The expanded use of targeted anticancer agents such as sorafenib has revealed a growing spectrum of adverse cutaneous eruptions. We describe 3 patients with sorafenib-induced psoriasiform dermatitis and review the literature of only 10 other similar reported cases based on a search of PubMed, Web of Science, and American Society of Clinical Oncology abstracts using the terms psoriasis or psoriasiform dermatitis and sorafenib.1-10 We seek to increase awareness of this particular drug eruption in response to sorafenib and to describe potential effective treatment options, especially when sorafenib cannot be discontinued.

Case Reports

Patient 1

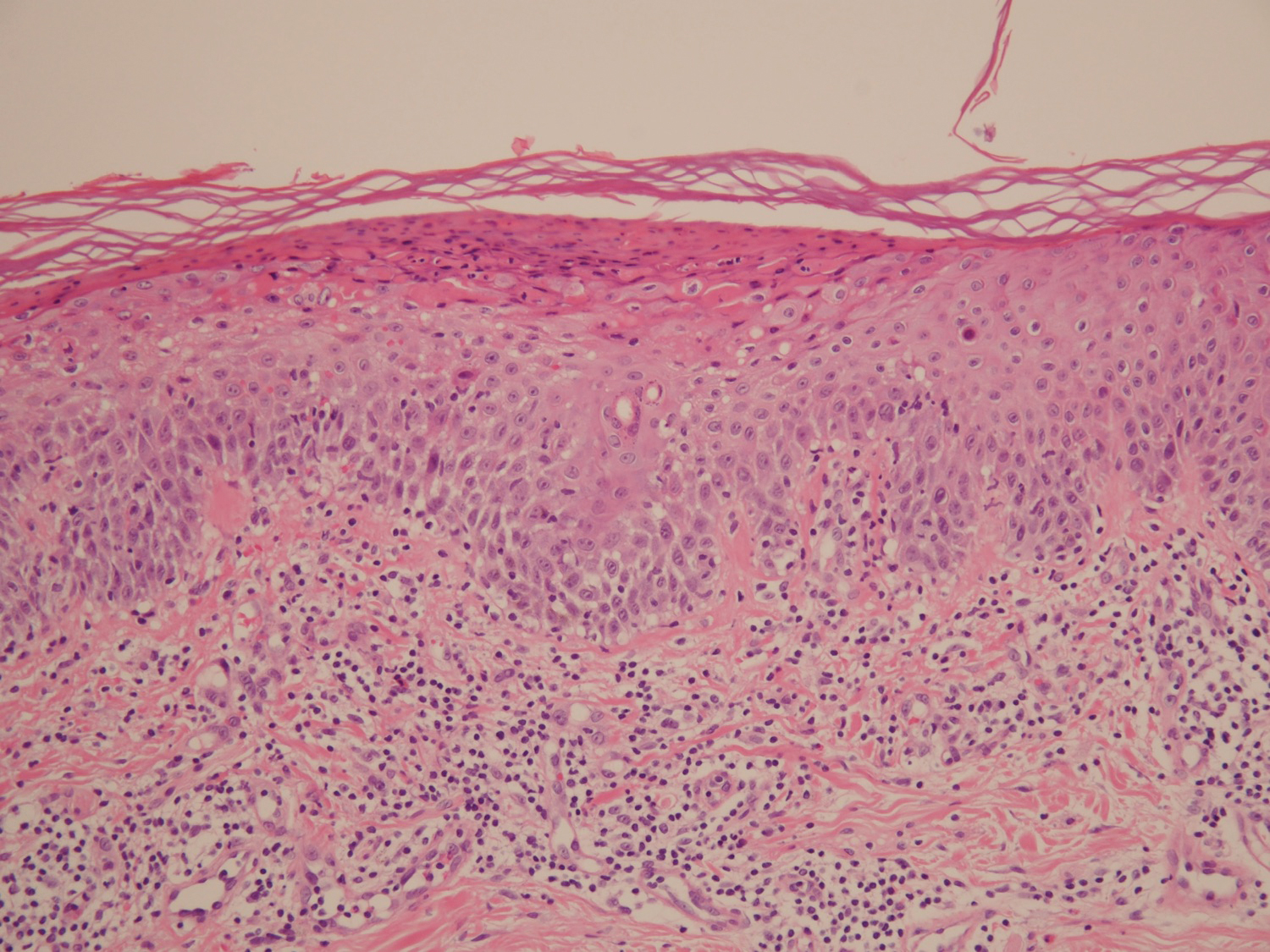

A 68-year-old man with chronic hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was started on sorafenib 400 mg daily. After 2 months of treatment, he developed painful hyperkeratotic lesions on the bilateral palms and soles with formation of calluses and superficial blisters on an erythematous base that was consistent with hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR). He also had numerous erythematous thin papules and plaques with adherent white scale and yellow crust on the bilateral thighs, lower legs, forearms, dorsal hands, abdomen, back, and buttocks (Figure 1). He had no personal or family history of psoriasis, and blood tests were unremarkable. Histologic analysis of punch biopsies from the buttocks and right leg revealed focal parakeratosis with neutrophils and serous crust, acanthosis, mild spongiosis, and lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and surrounding dermal vessels, consistent with psoriasiform dermatitis (Figure 2). Sorafenib was discontinued and the eruption began to resolve within a week. A lower dose of sorafenib (200 mg daily) was attempted and the psoriasiform eruption recurred.

Patient 2

An 82-year-old man with chronic hepatitis B infection and HCC with lung metastasis was treated with sorafenib 400 mg daily. One week after treatment, he developed painful, thick, erythematous lesions on acral surfaces, consistent with HFSR. The sorafenib dose was decreased to 200 mg daily and HFSR resolved. Four months later, he developed well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques with peripheral pustules on the right thigh (Figure 3) and right shin. He had no personal or family history of psoriasis, and blood tests were unremarkable. Samples from the pustules were taken for bacterial culture and fungal stain, but both were negative. Histologic analysis of a punch biopsy from the right thigh revealed necrotic parakeratosis, spongiform pustules, mild acanthosis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with many neutrophils in the dermis. These findings suggested a diagnosis of pustular psoriasis, pustular drug eruption, or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Treatment was initiated with mometasone cream. The patient subsequently developed hemoptysis and ascites from sorafenib. Sorafenib was discontinued and his skin eruption gradually resolved.

Patient 3

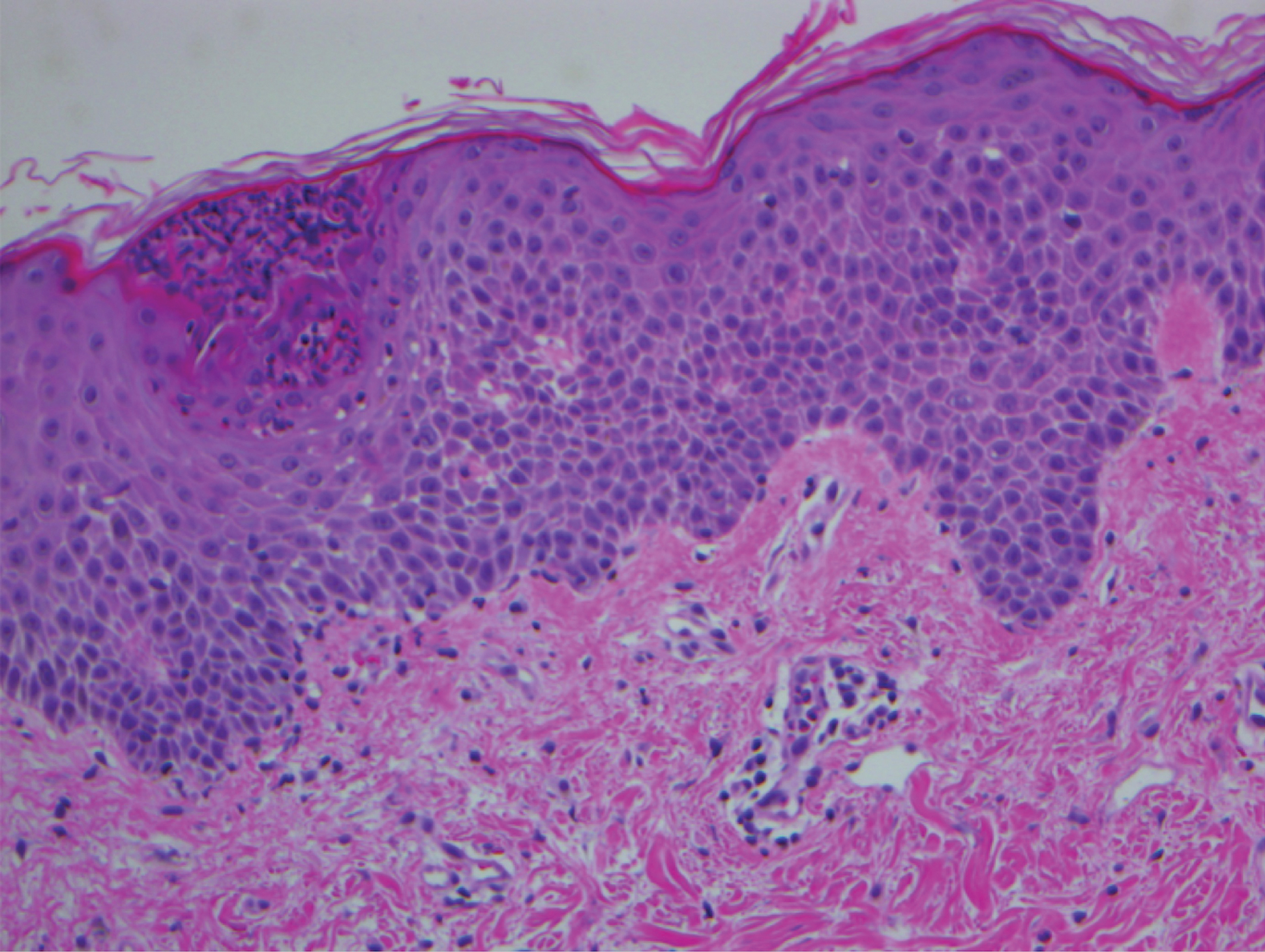

A 45-year-old woman with history of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was started on sorafenib 200 mg twice daily as part of a clinical pilot study to maintain remission following an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Four months after beginning sorafenib, the patient developed multiple well-defined, erythematous, thin papules and plaques with overlying flaky white scale on the bilateral upper extremities and trunk and scattered on the bilateral upper thighs (Figure 4) along with abdominal pain. Her other medical history, physical findings, and laboratory results were unremarkable, and there was no personal or family history of psoriasis. Her oncologist suspected that the eruption and symptoms were due to sorafenib and reduced the dose to 200 mg daily. Histologic analysis of a punch biopsy specimen revealed subcorneal neutrophilic collections with mild spongiosis and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for antibody or complement deposition. A bone marrow biopsy was negative for AML recurrence. The patient was continued on sorafenib to prevent AML recurrence, and she was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily. Two weeks later, the eruption worsened and the patient was started on oral hydroxyzine for pruritus and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy 3 times a week. After 9 applications of NB-UVB phototherapy, there was complete resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Sorafenib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis due to its activity against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, stem cell growth factor receptor, and rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinases.11 It is primarily used for the treatment of solid tumors, such as advanced renal cell carcinoma, unresectable HCC, and thyroid carcinoma, and more recently has been expanded for treatment of AML due to potential inhibition of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor. Although dermatologic toxicity is a common adverse event during treatment with sorafenib,11 reports of psoriasiform drug eruptions are rare.

Review of Cases

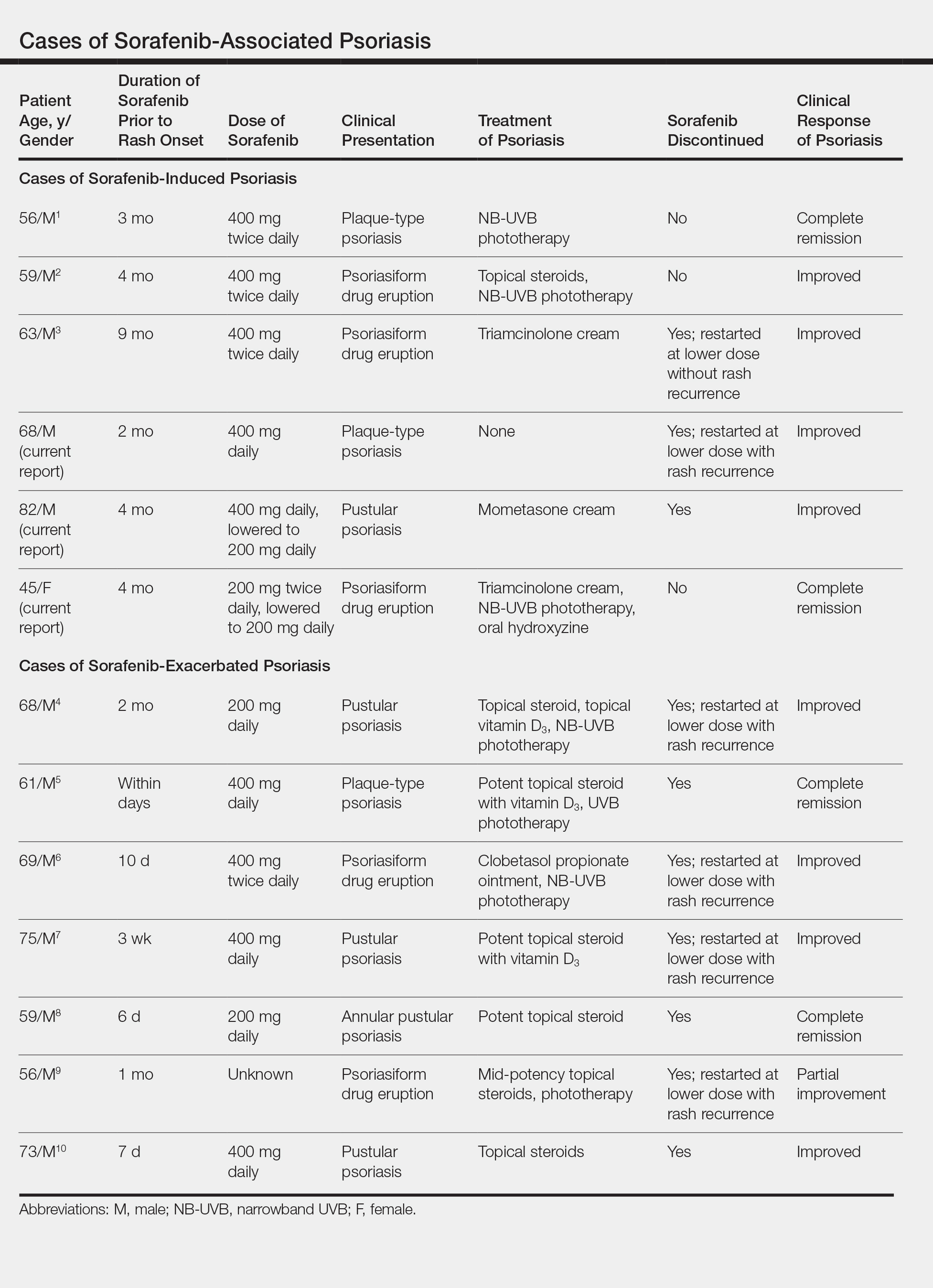

Based on our literature search, there are 10 previously reported cases of psoriasiform drug eruption secondary to sorafenib. Of the 13 total cases (including the 3 patients in this report), 7 patients had a history of psoriasis; most were middle-aged men; and the treatment with sorafenib was for solid tumors, primarily HCC with the exception of patient 3 from the current report who was treated for AML (Table). In all cases, the dose of sorafenib ranged from 200 to 800 mg daily. In 5 cases, HFSR preceded (as with patient 2 in the current report) or presented concurrently (as with patient 1 in the current report) with the onset of psoriasiform rash.1,3,5

Of the 13 total cases, patients with a history of psoriasis generally developed the eruption in a shorter period of time after starting sorafenib (eg, days to 2 months) compared to those without a history of psoriasis (eg, 2 to 9 months)(Table), suggesting that patients with preexisting psoriasis more rapidly developed the drug eruption than patients without a history. In these patients with a history of psoriasis, all had long-standing mild to moderate stable plaque psoriasis, with the exception of 1 case in which the type of psoriasis was not described (Table).7 The presentation of the drug eruption following sorafenib varied from psoriasiform drug eruption (5 patients, including patient 3),2,3,6,9 pustular psoriasis (5 patients, including patient 2),4,7,8,10 and plaque psoriasis (3 patients, including patient 1).1,5 Interestingly, 5 of 6 patients with a history of plaque psoriasis presented with pustular psoriasis or psoriasiform drug eruption after treatment with sorafenib.4-6,8-10 These results suggest a causal relationship between sorafenib and exacerbation of preexisting psoriasis.

In the 13 total cases, treatments included mid- to high-potency topical steroids (10 cases), UVB or NB-UVB phototherapy (7 cases), and discontinuation of sorafenib (10 cases)(Table). All of these treatments led to improvement of the eruption with the exception of 1 case in which hand involvement was recalcitrant to therapy.9 Of the 10 cases in which sorafenib was discontinued, rechallenge at a lower dose was performed in 6 cases (including patient 1)3,4,6,7,9 with recurrence of psoriasiform rash seen in 5 cases (including patient 1)(Table).4,6,7,9 These data strongly implicate sorafenib as the direct cause of these psoriasiform eruptions. In the 3 cases in which sorafenib was not discontinued (including patient 3), there was notable improvement of the eruption with NB-UVB phototherapy.1,2

Vascular endothelial growth factor is overexpressed on psoriatic keratinocytes, contributes to epidermal hyperplasia, and induces angiogenesis in the dermis.12 The development of psoriasiform eruptions in patients treated with sorafenib seems paradoxical, as this drug has been considered as potential therapy for psoriasis due to its ability to block VEGF receptor signaling. Indeed, an improvement of psoriasis has been reported in 1 case of a patient treated with sorafenib13 and in multiple patients with psoriasis treated with other VEGF antagonists (eg, bevacizumab).14 The underlying mechanisms by which sorafenib induced or exacerbated psoriasis are not entirely clear. Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, keratosis pilaris–like eruption, multiple cysts, eruptive keratoacanthomas, and squamous cell carcinoma have been described in patients treated with sorafenib, supporting the hypothesis that treatment with sorafenib alters keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation.15 In addition, B-Raf inhibitors such as imatinib are known to induce or exacerbate psoriasiform dermatitis.16 The activity of sorafenib resulting in psoriasis may be specific to RAF kinase inhibition, as there are no reports in the literature that describe psoriasiform dermatitis with agents that preferentially block other sorafenib targets such as VEGF receptor, stem cell growth factor receptor, or platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Future studies are needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which sorafenib induces or exacerbates psoriasiform dermatitis and whether the severity of the drug eruption correlates with the antitumor efficacy of sorafenib.

Conclusion

Although psoriasiform drug eruptions secondary to sorafenib are not life-threatening, they impact quality of life with associated pain, pruritus, infection, and limitation of daily activities. Dose reduction or discontinuation of sorafenib resulted in resolution of the psoriasiform dermatitis; however, as demonstrated in 3 cases (including patient 3),1,2 psoriasiform dermatitis can be managed while maintaining the patient on sorafenib so that treatment of the malignancy is not compromised.

- Hung CT, Chiang CP, Wu BY. Sorafenib-induced psoriasis and hand-foot skin reaction responded dramatically to systemic narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1076-1077.

- González-López M, Yáñez S, Val-Bernal JF, et al. Psoriasiform skin eruption associated with sorafenib therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:614-615.

- Diamantis ML, Chon SY. Sorafenib-induced psoriasiform eruption in a patient with metastatic thyroid carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:169-171.

- Hsu MC, Chen CC. Psoriasis flare-ups following sorafenib therapy: a rare case. Dermatologica Sin. 2016;34:148-150.

- Yiu ZZ, Ali FR, Griffiths CE. Paradoxical exacerbation of chronic plaque psoriasis by sorafenib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:407-409.

- I˙lknur T, Akarsu S, Çarsanbali S, et al. Sorafenib-associated psoriasiform eruption in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:899-900.

- Maki N, Komine M, Takatsuka Y, et al. Pustular eruption induced by sorafenib in a case of psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2013;40:299-300.

- Du-Thanh A, Girard C, Pageaux GP, et al. Sorafenib-induced annular pustular psoriasis (Milian-Katchoura type). Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:900-901.

- Laquer V, Saedi N, Dann F, et al. Sorafenib-associated psoriasiform skin changes. Cutis. 2010;85:301-302.

- Ohashi T, Yamamoto T. Exacerbation of psoriasis with pustulation by sorafenib in a patient with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:75-77.

- Chu D, Lacouture ME, Fillos T, et al. Risk of hand-foot skin reaction with sorafenib: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2008;47:176-186.

- Canavese M, Altruda F, Ruzicka T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the pathogenesis of psoriasis--a possible target for novel therapies? J Dermatol Sci. 2010;58:171-176.

- Fournier C, Tisman G. Sorafenib-associated remission of psoriasis in hypernephroma: case report. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:17.

- Akman A, Yilmaz E, Mutlu H, et al. Complete remission of psoriasis following bevacizumab therapy for colon cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E202-E204.

- Kong HH, Turner ML. Array of cutaneous adverse effects associated with sorafenib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:360-361.

- Atalay F, Kızılkılıç E, Ada RS. Imatinib-induced psoriasis. Turk J Haematol. 2013;30:216-218.

The expanded use of targeted anticancer agents such as sorafenib has revealed a growing spectrum of adverse cutaneous eruptions. We describe 3 patients with sorafenib-induced psoriasiform dermatitis and review the literature of only 10 other similar reported cases based on a search of PubMed, Web of Science, and American Society of Clinical Oncology abstracts using the terms psoriasis or psoriasiform dermatitis and sorafenib.1-10 We seek to increase awareness of this particular drug eruption in response to sorafenib and to describe potential effective treatment options, especially when sorafenib cannot be discontinued.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 68-year-old man with chronic hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was started on sorafenib 400 mg daily. After 2 months of treatment, he developed painful hyperkeratotic lesions on the bilateral palms and soles with formation of calluses and superficial blisters on an erythematous base that was consistent with hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR). He also had numerous erythematous thin papules and plaques with adherent white scale and yellow crust on the bilateral thighs, lower legs, forearms, dorsal hands, abdomen, back, and buttocks (Figure 1). He had no personal or family history of psoriasis, and blood tests were unremarkable. Histologic analysis of punch biopsies from the buttocks and right leg revealed focal parakeratosis with neutrophils and serous crust, acanthosis, mild spongiosis, and lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and surrounding dermal vessels, consistent with psoriasiform dermatitis (Figure 2). Sorafenib was discontinued and the eruption began to resolve within a week. A lower dose of sorafenib (200 mg daily) was attempted and the psoriasiform eruption recurred.

Patient 2

An 82-year-old man with chronic hepatitis B infection and HCC with lung metastasis was treated with sorafenib 400 mg daily. One week after treatment, he developed painful, thick, erythematous lesions on acral surfaces, consistent with HFSR. The sorafenib dose was decreased to 200 mg daily and HFSR resolved. Four months later, he developed well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques with peripheral pustules on the right thigh (Figure 3) and right shin. He had no personal or family history of psoriasis, and blood tests were unremarkable. Samples from the pustules were taken for bacterial culture and fungal stain, but both were negative. Histologic analysis of a punch biopsy from the right thigh revealed necrotic parakeratosis, spongiform pustules, mild acanthosis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with many neutrophils in the dermis. These findings suggested a diagnosis of pustular psoriasis, pustular drug eruption, or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Treatment was initiated with mometasone cream. The patient subsequently developed hemoptysis and ascites from sorafenib. Sorafenib was discontinued and his skin eruption gradually resolved.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old woman with history of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was started on sorafenib 200 mg twice daily as part of a clinical pilot study to maintain remission following an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Four months after beginning sorafenib, the patient developed multiple well-defined, erythematous, thin papules and plaques with overlying flaky white scale on the bilateral upper extremities and trunk and scattered on the bilateral upper thighs (Figure 4) along with abdominal pain. Her other medical history, physical findings, and laboratory results were unremarkable, and there was no personal or family history of psoriasis. Her oncologist suspected that the eruption and symptoms were due to sorafenib and reduced the dose to 200 mg daily. Histologic analysis of a punch biopsy specimen revealed subcorneal neutrophilic collections with mild spongiosis and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for antibody or complement deposition. A bone marrow biopsy was negative for AML recurrence. The patient was continued on sorafenib to prevent AML recurrence, and she was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily. Two weeks later, the eruption worsened and the patient was started on oral hydroxyzine for pruritus and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy 3 times a week. After 9 applications of NB-UVB phototherapy, there was complete resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Sorafenib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis due to its activity against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, stem cell growth factor receptor, and rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinases.11 It is primarily used for the treatment of solid tumors, such as advanced renal cell carcinoma, unresectable HCC, and thyroid carcinoma, and more recently has been expanded for treatment of AML due to potential inhibition of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor. Although dermatologic toxicity is a common adverse event during treatment with sorafenib,11 reports of psoriasiform drug eruptions are rare.

Review of Cases

Based on our literature search, there are 10 previously reported cases of psoriasiform drug eruption secondary to sorafenib. Of the 13 total cases (including the 3 patients in this report), 7 patients had a history of psoriasis; most were middle-aged men; and the treatment with sorafenib was for solid tumors, primarily HCC with the exception of patient 3 from the current report who was treated for AML (Table). In all cases, the dose of sorafenib ranged from 200 to 800 mg daily. In 5 cases, HFSR preceded (as with patient 2 in the current report) or presented concurrently (as with patient 1 in the current report) with the onset of psoriasiform rash.1,3,5

Of the 13 total cases, patients with a history of psoriasis generally developed the eruption in a shorter period of time after starting sorafenib (eg, days to 2 months) compared to those without a history of psoriasis (eg, 2 to 9 months)(Table), suggesting that patients with preexisting psoriasis more rapidly developed the drug eruption than patients without a history. In these patients with a history of psoriasis, all had long-standing mild to moderate stable plaque psoriasis, with the exception of 1 case in which the type of psoriasis was not described (Table).7 The presentation of the drug eruption following sorafenib varied from psoriasiform drug eruption (5 patients, including patient 3),2,3,6,9 pustular psoriasis (5 patients, including patient 2),4,7,8,10 and plaque psoriasis (3 patients, including patient 1).1,5 Interestingly, 5 of 6 patients with a history of plaque psoriasis presented with pustular psoriasis or psoriasiform drug eruption after treatment with sorafenib.4-6,8-10 These results suggest a causal relationship between sorafenib and exacerbation of preexisting psoriasis.

In the 13 total cases, treatments included mid- to high-potency topical steroids (10 cases), UVB or NB-UVB phototherapy (7 cases), and discontinuation of sorafenib (10 cases)(Table). All of these treatments led to improvement of the eruption with the exception of 1 case in which hand involvement was recalcitrant to therapy.9 Of the 10 cases in which sorafenib was discontinued, rechallenge at a lower dose was performed in 6 cases (including patient 1)3,4,6,7,9 with recurrence of psoriasiform rash seen in 5 cases (including patient 1)(Table).4,6,7,9 These data strongly implicate sorafenib as the direct cause of these psoriasiform eruptions. In the 3 cases in which sorafenib was not discontinued (including patient 3), there was notable improvement of the eruption with NB-UVB phototherapy.1,2

Vascular endothelial growth factor is overexpressed on psoriatic keratinocytes, contributes to epidermal hyperplasia, and induces angiogenesis in the dermis.12 The development of psoriasiform eruptions in patients treated with sorafenib seems paradoxical, as this drug has been considered as potential therapy for psoriasis due to its ability to block VEGF receptor signaling. Indeed, an improvement of psoriasis has been reported in 1 case of a patient treated with sorafenib13 and in multiple patients with psoriasis treated with other VEGF antagonists (eg, bevacizumab).14 The underlying mechanisms by which sorafenib induced or exacerbated psoriasis are not entirely clear. Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, keratosis pilaris–like eruption, multiple cysts, eruptive keratoacanthomas, and squamous cell carcinoma have been described in patients treated with sorafenib, supporting the hypothesis that treatment with sorafenib alters keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation.15 In addition, B-Raf inhibitors such as imatinib are known to induce or exacerbate psoriasiform dermatitis.16 The activity of sorafenib resulting in psoriasis may be specific to RAF kinase inhibition, as there are no reports in the literature that describe psoriasiform dermatitis with agents that preferentially block other sorafenib targets such as VEGF receptor, stem cell growth factor receptor, or platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Future studies are needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which sorafenib induces or exacerbates psoriasiform dermatitis and whether the severity of the drug eruption correlates with the antitumor efficacy of sorafenib.

Conclusion

Although psoriasiform drug eruptions secondary to sorafenib are not life-threatening, they impact quality of life with associated pain, pruritus, infection, and limitation of daily activities. Dose reduction or discontinuation of sorafenib resulted in resolution of the psoriasiform dermatitis; however, as demonstrated in 3 cases (including patient 3),1,2 psoriasiform dermatitis can be managed while maintaining the patient on sorafenib so that treatment of the malignancy is not compromised.

The expanded use of targeted anticancer agents such as sorafenib has revealed a growing spectrum of adverse cutaneous eruptions. We describe 3 patients with sorafenib-induced psoriasiform dermatitis and review the literature of only 10 other similar reported cases based on a search of PubMed, Web of Science, and American Society of Clinical Oncology abstracts using the terms psoriasis or psoriasiform dermatitis and sorafenib.1-10 We seek to increase awareness of this particular drug eruption in response to sorafenib and to describe potential effective treatment options, especially when sorafenib cannot be discontinued.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 68-year-old man with chronic hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was started on sorafenib 400 mg daily. After 2 months of treatment, he developed painful hyperkeratotic lesions on the bilateral palms and soles with formation of calluses and superficial blisters on an erythematous base that was consistent with hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR). He also had numerous erythematous thin papules and plaques with adherent white scale and yellow crust on the bilateral thighs, lower legs, forearms, dorsal hands, abdomen, back, and buttocks (Figure 1). He had no personal or family history of psoriasis, and blood tests were unremarkable. Histologic analysis of punch biopsies from the buttocks and right leg revealed focal parakeratosis with neutrophils and serous crust, acanthosis, mild spongiosis, and lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and surrounding dermal vessels, consistent with psoriasiform dermatitis (Figure 2). Sorafenib was discontinued and the eruption began to resolve within a week. A lower dose of sorafenib (200 mg daily) was attempted and the psoriasiform eruption recurred.

Patient 2

An 82-year-old man with chronic hepatitis B infection and HCC with lung metastasis was treated with sorafenib 400 mg daily. One week after treatment, he developed painful, thick, erythematous lesions on acral surfaces, consistent with HFSR. The sorafenib dose was decreased to 200 mg daily and HFSR resolved. Four months later, he developed well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques with peripheral pustules on the right thigh (Figure 3) and right shin. He had no personal or family history of psoriasis, and blood tests were unremarkable. Samples from the pustules were taken for bacterial culture and fungal stain, but both were negative. Histologic analysis of a punch biopsy from the right thigh revealed necrotic parakeratosis, spongiform pustules, mild acanthosis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with many neutrophils in the dermis. These findings suggested a diagnosis of pustular psoriasis, pustular drug eruption, or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Treatment was initiated with mometasone cream. The patient subsequently developed hemoptysis and ascites from sorafenib. Sorafenib was discontinued and his skin eruption gradually resolved.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old woman with history of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was started on sorafenib 200 mg twice daily as part of a clinical pilot study to maintain remission following an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Four months after beginning sorafenib, the patient developed multiple well-defined, erythematous, thin papules and plaques with overlying flaky white scale on the bilateral upper extremities and trunk and scattered on the bilateral upper thighs (Figure 4) along with abdominal pain. Her other medical history, physical findings, and laboratory results were unremarkable, and there was no personal or family history of psoriasis. Her oncologist suspected that the eruption and symptoms were due to sorafenib and reduced the dose to 200 mg daily. Histologic analysis of a punch biopsy specimen revealed subcorneal neutrophilic collections with mild spongiosis and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for antibody or complement deposition. A bone marrow biopsy was negative for AML recurrence. The patient was continued on sorafenib to prevent AML recurrence, and she was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily. Two weeks later, the eruption worsened and the patient was started on oral hydroxyzine for pruritus and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy 3 times a week. After 9 applications of NB-UVB phototherapy, there was complete resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Sorafenib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis due to its activity against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, stem cell growth factor receptor, and rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinases.11 It is primarily used for the treatment of solid tumors, such as advanced renal cell carcinoma, unresectable HCC, and thyroid carcinoma, and more recently has been expanded for treatment of AML due to potential inhibition of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor. Although dermatologic toxicity is a common adverse event during treatment with sorafenib,11 reports of psoriasiform drug eruptions are rare.

Review of Cases

Based on our literature search, there are 10 previously reported cases of psoriasiform drug eruption secondary to sorafenib. Of the 13 total cases (including the 3 patients in this report), 7 patients had a history of psoriasis; most were middle-aged men; and the treatment with sorafenib was for solid tumors, primarily HCC with the exception of patient 3 from the current report who was treated for AML (Table). In all cases, the dose of sorafenib ranged from 200 to 800 mg daily. In 5 cases, HFSR preceded (as with patient 2 in the current report) or presented concurrently (as with patient 1 in the current report) with the onset of psoriasiform rash.1,3,5

Of the 13 total cases, patients with a history of psoriasis generally developed the eruption in a shorter period of time after starting sorafenib (eg, days to 2 months) compared to those without a history of psoriasis (eg, 2 to 9 months)(Table), suggesting that patients with preexisting psoriasis more rapidly developed the drug eruption than patients without a history. In these patients with a history of psoriasis, all had long-standing mild to moderate stable plaque psoriasis, with the exception of 1 case in which the type of psoriasis was not described (Table).7 The presentation of the drug eruption following sorafenib varied from psoriasiform drug eruption (5 patients, including patient 3),2,3,6,9 pustular psoriasis (5 patients, including patient 2),4,7,8,10 and plaque psoriasis (3 patients, including patient 1).1,5 Interestingly, 5 of 6 patients with a history of plaque psoriasis presented with pustular psoriasis or psoriasiform drug eruption after treatment with sorafenib.4-6,8-10 These results suggest a causal relationship between sorafenib and exacerbation of preexisting psoriasis.

In the 13 total cases, treatments included mid- to high-potency topical steroids (10 cases), UVB or NB-UVB phototherapy (7 cases), and discontinuation of sorafenib (10 cases)(Table). All of these treatments led to improvement of the eruption with the exception of 1 case in which hand involvement was recalcitrant to therapy.9 Of the 10 cases in which sorafenib was discontinued, rechallenge at a lower dose was performed in 6 cases (including patient 1)3,4,6,7,9 with recurrence of psoriasiform rash seen in 5 cases (including patient 1)(Table).4,6,7,9 These data strongly implicate sorafenib as the direct cause of these psoriasiform eruptions. In the 3 cases in which sorafenib was not discontinued (including patient 3), there was notable improvement of the eruption with NB-UVB phototherapy.1,2

Vascular endothelial growth factor is overexpressed on psoriatic keratinocytes, contributes to epidermal hyperplasia, and induces angiogenesis in the dermis.12 The development of psoriasiform eruptions in patients treated with sorafenib seems paradoxical, as this drug has been considered as potential therapy for psoriasis due to its ability to block VEGF receptor signaling. Indeed, an improvement of psoriasis has been reported in 1 case of a patient treated with sorafenib13 and in multiple patients with psoriasis treated with other VEGF antagonists (eg, bevacizumab).14 The underlying mechanisms by which sorafenib induced or exacerbated psoriasis are not entirely clear. Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, keratosis pilaris–like eruption, multiple cysts, eruptive keratoacanthomas, and squamous cell carcinoma have been described in patients treated with sorafenib, supporting the hypothesis that treatment with sorafenib alters keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation.15 In addition, B-Raf inhibitors such as imatinib are known to induce or exacerbate psoriasiform dermatitis.16 The activity of sorafenib resulting in psoriasis may be specific to RAF kinase inhibition, as there are no reports in the literature that describe psoriasiform dermatitis with agents that preferentially block other sorafenib targets such as VEGF receptor, stem cell growth factor receptor, or platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Future studies are needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which sorafenib induces or exacerbates psoriasiform dermatitis and whether the severity of the drug eruption correlates with the antitumor efficacy of sorafenib.

Conclusion

Although psoriasiform drug eruptions secondary to sorafenib are not life-threatening, they impact quality of life with associated pain, pruritus, infection, and limitation of daily activities. Dose reduction or discontinuation of sorafenib resulted in resolution of the psoriasiform dermatitis; however, as demonstrated in 3 cases (including patient 3),1,2 psoriasiform dermatitis can be managed while maintaining the patient on sorafenib so that treatment of the malignancy is not compromised.

- Hung CT, Chiang CP, Wu BY. Sorafenib-induced psoriasis and hand-foot skin reaction responded dramatically to systemic narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1076-1077.

- González-López M, Yáñez S, Val-Bernal JF, et al. Psoriasiform skin eruption associated with sorafenib therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:614-615.

- Diamantis ML, Chon SY. Sorafenib-induced psoriasiform eruption in a patient with metastatic thyroid carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:169-171.

- Hsu MC, Chen CC. Psoriasis flare-ups following sorafenib therapy: a rare case. Dermatologica Sin. 2016;34:148-150.

- Yiu ZZ, Ali FR, Griffiths CE. Paradoxical exacerbation of chronic plaque psoriasis by sorafenib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:407-409.

- I˙lknur T, Akarsu S, Çarsanbali S, et al. Sorafenib-associated psoriasiform eruption in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:899-900.

- Maki N, Komine M, Takatsuka Y, et al. Pustular eruption induced by sorafenib in a case of psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2013;40:299-300.

- Du-Thanh A, Girard C, Pageaux GP, et al. Sorafenib-induced annular pustular psoriasis (Milian-Katchoura type). Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:900-901.

- Laquer V, Saedi N, Dann F, et al. Sorafenib-associated psoriasiform skin changes. Cutis. 2010;85:301-302.

- Ohashi T, Yamamoto T. Exacerbation of psoriasis with pustulation by sorafenib in a patient with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:75-77.

- Chu D, Lacouture ME, Fillos T, et al. Risk of hand-foot skin reaction with sorafenib: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2008;47:176-186.

- Canavese M, Altruda F, Ruzicka T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the pathogenesis of psoriasis--a possible target for novel therapies? J Dermatol Sci. 2010;58:171-176.

- Fournier C, Tisman G. Sorafenib-associated remission of psoriasis in hypernephroma: case report. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:17.

- Akman A, Yilmaz E, Mutlu H, et al. Complete remission of psoriasis following bevacizumab therapy for colon cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E202-E204.

- Kong HH, Turner ML. Array of cutaneous adverse effects associated with sorafenib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:360-361.

- Atalay F, Kızılkılıç E, Ada RS. Imatinib-induced psoriasis. Turk J Haematol. 2013;30:216-218.

- Hung CT, Chiang CP, Wu BY. Sorafenib-induced psoriasis and hand-foot skin reaction responded dramatically to systemic narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1076-1077.

- González-López M, Yáñez S, Val-Bernal JF, et al. Psoriasiform skin eruption associated with sorafenib therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:614-615.

- Diamantis ML, Chon SY. Sorafenib-induced psoriasiform eruption in a patient with metastatic thyroid carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:169-171.

- Hsu MC, Chen CC. Psoriasis flare-ups following sorafenib therapy: a rare case. Dermatologica Sin. 2016;34:148-150.

- Yiu ZZ, Ali FR, Griffiths CE. Paradoxical exacerbation of chronic plaque psoriasis by sorafenib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:407-409.

- I˙lknur T, Akarsu S, Çarsanbali S, et al. Sorafenib-associated psoriasiform eruption in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:899-900.

- Maki N, Komine M, Takatsuka Y, et al. Pustular eruption induced by sorafenib in a case of psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2013;40:299-300.

- Du-Thanh A, Girard C, Pageaux GP, et al. Sorafenib-induced annular pustular psoriasis (Milian-Katchoura type). Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:900-901.

- Laquer V, Saedi N, Dann F, et al. Sorafenib-associated psoriasiform skin changes. Cutis. 2010;85:301-302.

- Ohashi T, Yamamoto T. Exacerbation of psoriasis with pustulation by sorafenib in a patient with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:75-77.

- Chu D, Lacouture ME, Fillos T, et al. Risk of hand-foot skin reaction with sorafenib: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2008;47:176-186.

- Canavese M, Altruda F, Ruzicka T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the pathogenesis of psoriasis--a possible target for novel therapies? J Dermatol Sci. 2010;58:171-176.

- Fournier C, Tisman G. Sorafenib-associated remission of psoriasis in hypernephroma: case report. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:17.

- Akman A, Yilmaz E, Mutlu H, et al. Complete remission of psoriasis following bevacizumab therapy for colon cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E202-E204.

- Kong HH, Turner ML. Array of cutaneous adverse effects associated with sorafenib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:360-361.

- Atalay F, Kızılkılıç E, Ada RS. Imatinib-induced psoriasis. Turk J Haematol. 2013;30:216-218.

Practice Points

- The use of targeted anticancer agents continues to expand. With this expansion, the number and type of cutaneous adverse events continues to increase.

- Although sorafenib is known to cause various dermatologic side effects, there are few reports of psoriasiform dermatitis.

- Increased awareness of sorafenib-induced psoriasiform dermatitis and its management is vital to prevent discontinuation of potentially life-saving anticancer therapy.

Multiple Papules on the Eyelid Margin

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

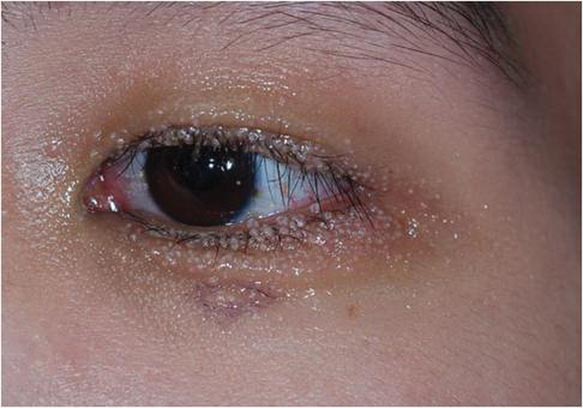

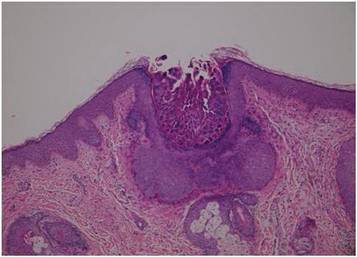

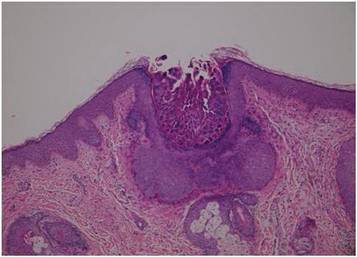

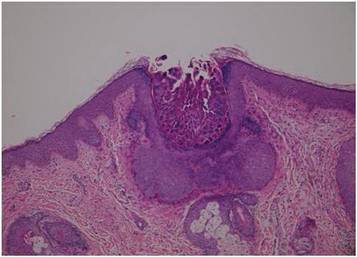

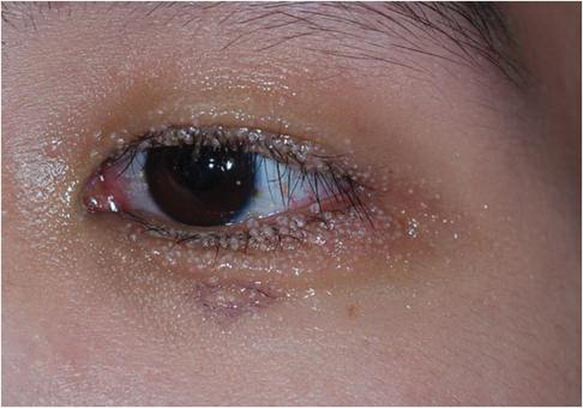

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

A 24-year-old man presented with multiple tiny papules over the left eyelid margin of 2 to 3 months’ duration. There were a couple of papules on the left upper eyelid initially, but they progressed to the upper and lower eyelid margin after scratching. On physical examination, multiple whitish to flesh-colored pearly papules measuring 1 to 2 mm were located on the left eyelid margin. Palpebral follicular conjunctivitis also was noted.