User login

Post-Intensive Care Unit Psychiatric Comorbidity and Quality of Life

The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors ranges from 17% to 44%.1-4 Psychiatric comorbidity, the presence of 2 or more psychiatric disorders, is highly prevalent in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome and is associated with higher mortality in postsurgical ICU survivors.5-7 While long-term cognitive impairment in patients with ICU delirium has been associated with poor quality of life (QoL),1 the effects of psychiatric comorbidity on QoL among similar patients are not as well understood. In this study, we examined whether psychiatric comorbidity was associated with poorer QoL in survivors of ICU delirium.

METHODS

We examined subjects who participated in the Pharmacologic Management of Delirium (PMD) clinical trial. This trial examined the efficacy of a pharmacological intervention for patients who developed ICU delirium at a local tertiary-care academic hospital.8 Out of 62 patients who participated in the follow-up of the PMD study, 58 completed QoL interviews and validated psychiatric screens (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9] for depression, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] questionnaire for anxiety, and the Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome [PTSS-10] questionnaire for PTSD) at 3 months after hospital discharge. High psychiatric comorbidity was defined as having significant symptoms for all 3 conditions (depression: PHQ-9 score ≥ 10; anxiety: GAD-7 ≥ 10; and PTSD: PTSS-10 > 35). No psychiatric morbidity was defined as having no significant symptoms for all 3 conditions. Low to moderate (low-moderate) psychiatric morbidity was defined as having symptoms for 1 to 2 conditions.

Participants also completed 2 complementary QoL measures: the EuroQol 5 dimensions questionnaire 3-level (EQ-5D-3L) Index and the EuroQol 5 dimensions Visual Analog Scale (EQ-5D-VAS).9 The EQ-5D-3L Index asks participants to rate themselves as having (1) no problems, (2) some problems, or (3) extreme problems on the following 5 scales: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The scores are then indexed against the US population to create a continuous index scale ranging from −0.11 to 1.00.

Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare dichotomous outcomes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous outcomes across the 3 psychiatric groups. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine whether psychiatric comorbidity in survivors of ICU delirium was associated with QoL measures. Models were adjusted for the following covariates: age, gender, Charlson Comorbidity Index, discharged to home, prior history of depression, and prior history of anxiety. To assess the relationship of psychiatric comorbidity with QoL, we chose the 2 continuous QoL measures as the outcome. Because we were interested in the effect of psychiatric burden on QoL, we used ANCOVA with QoL as the dependent variable and psychiatric burden as an independent variable. Pairwise comparisons were then performed when overall differences were significant (P < 0.05). We performed 2 separate sensitivity analyses. The first analysis looked solely at the subgroup of patients from the medical intensive care unit. We also recalculated the EQ-5D-3L index excluding the anxiety/depression item.

RESULTS

Nearly one-third of patients (18/58) had high psychiatric burden. The table looks at the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with high psychiatric comorbidity versus those of low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity and those with no psychiatric morbidity. Patient groups did not differ significantly in terms of demographics. For clinical characteristics, patients with high psychiatric comorbidity were more likely than patients with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity to have a prior history of depression (P < 0.05).

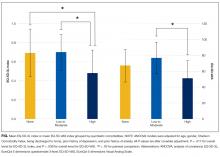

Patients with high psychiatric comorbidity were more likely to have a poorer QoL when compared with patients with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity and to those with no morbidity as measured by a lower EQ-5D-3L Index (no, 0.69 ± 0.25; low-moderate, 0.70 ± 0.19; high, 0.48 ± 0.24; P = 0.006) and EQ-5D-VAS (no, 67.0 ± 20.7; low-moderate, 76.6 ± 20.0; high, 50.8 ± 22.4; P = 0.004). After adjusting for covariates, patients with high psychiatric comorbidity had a poorer QoL compared with those with no morbidity or low-moderate comorbidity on the EQ-5D-3L Index (P = 0.017 for overall differences), whereas patients who had high psychiatric comorbidity had a poorer QoL compared to those with low-moderate comorbidity on the EQ-5D-VAS (P = 0.039 for overall differences; Figure). Subgroup analysis of MICU patients yielded similar results. Patients with high psychiatric burden had significantly poorer QoL as measured by the EQ-5D-3L (unadjusted P = 0.044, adjusted P = 0.003) and the EQ-5D-VAS (unadjusted P = 0.007, adjusted P = 0.021). After excluding the anxiety/depression item from the EQ-5D-3L, we observed similar differences (no, 0.71 ± 0.24; low-moderate, 0.75 ± 0.15; high, 0.58 ± 0.22; unadjusted P = 0.062; adjusted P = 0.040).

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

Psychiatric comorbidities in ICU survivors are common and pose a significant clinical issue. Patients with multiple psychiatric comorbidities can be more complicated to identify from a diagnostic standpoint and often require more prolonged, intensive mental health treatment when compared with patients with a single psychiatric disorder.10,11 Our study showed that high psychiatric comorbidity in survivors of ICU delirium is associated with a decreased QoL compared with those with no psychiatric comorbidity or with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity. This finding is consistent with previous studies in the general population that patients with multiple psychiatric comorbidities are associated with a poorer QoL compared with patients with a single psychiatric comorbidity.10,11

There is a pressing need to better characterize psychiatric comorbidities in ICU survivors because our current evidence suggests that the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities of ICU survivors is substantially higher than that of the general population. We found that nearly one-third of survivors of ICU delirium had comorbid depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms at 3 months. This is consistent with the few other studies of ICU survivors, which showed a prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity of 25% to 33%.5,12 These rates are substantially higher than the prevalence in the general population of 6%.13

The high rate of psychiatric comorbidities may render it difficult to effectively treat the mental health symptoms in ICU survivors.14 Treating multiple psychiatric comorbidities may also be especially challenging in survivors of ICU delirium because they have a high prevalence of cognitive impairment. Mental health treatments for patients with psychiatric disorders and comorbid cognitive impairment are limited. Better characterization of psychiatric comorbidity in ICU survivors, particularly those with ICU delirium, is vital to the development of more effective, bundled treatments for this population with multiple comorbidities.

Standardized screenings of ICU survivors at a high risk for psychiatric disorders, such as survivors of ICU delirium, may help to identify patients with comorbid psychiatric disorder symptoms and have them referred to appropriate treatment earlier with the hope of improving their QoL sooner. Although opportunities to deliver integrated outpatient collaborative mental health and medical care for a subspecialty population are limited, one potential model of care would be to utilize a collaborative-care model in an ICU survivor clinic.15

Strengths of our study include the examination of psychiatric comorbidities in survivors of ICU delirium, who often have a poor QoL. A deeper understanding of psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship with QoL is needed to better understand how to deliver more effective treatments for these survivors. Limitations include the small sample size, a one-time measurement of psychiatric comorbidities at the 3-month follow-up based on screenings tools, and a lack of objective measures of physical functioning to determine the effects of psychiatric comorbidities on physical functioning. There may also have been differences in how patients with no psychiatric comorbidity responded to the EQ-5D-VAS as a result of premorbid differences (eg, they were healthier prior to their ICU stay and perceived their survivor status more negatively). This may explain why we did not see a statistically significant difference between no psychiatric comorbidity and high psychiatric comorbidity groups on the EQ-5D-VAS. Nevertheless, we did see a difference between the low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity group on EQ-5D-VAS and differences between the no comorbidity and low-moderate comorbidity groups versus the high comorbidity group on the EQ-5D-3L. Finally, data about psychiatric history and QoL prior to ICU hospitalization were limited. Therefore, truly determining incidence versus prevalence of post-ICU comorbidities and whether psychiatric symptoms and its effects on QoL were due to ICU hospitalization or to premorbid psychiatric symptoms is difficult.

Our study demonstrated that in survivors of ICU delirium, higher comorbidity of psychiatric symptoms was associated with poorer QoL. Future studies will need to confirm these findings. We will also need to identify potentially reversible risk factors for psychiatric comorbidity and poorer QoL and develop treatments to effectively target the mental health symptoms of survivors of ICU delirium.

Disclosure

Grant support: The PMD trial is funded through the National Institutes of Health grant R01AG054205-02. SW is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133. AP is supported by CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00, Indiana CTSI, and NIA R01AG054205-02. SG is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133, NIA 5R01AG045350, and NIA R01AG054205-02. SK is supported by NHBLI 5T32HL091816-07. MB is supported by NIA R01 AG040220-05, AHRQ P30 HS024384-02, CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00, NIA R01 AG030618-05A1 and NIA R01AG054205-02. BK is supported by NIA K23-AG043476 and NHLBI R01HL131730. The funding agency had no role in the development of the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript development, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Conflicts of interest include MB, SG, and AP being funded by NIA R01AG054205-02 for the PMD study.

1. Jutte JE, Erb CT, Jackson JC. Physical, cognitive, and psychological disability following critical illness: what is the risk? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(6):943-958. PubMed

2. Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:23-29. PubMed

3. Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1744-1753. PubMed

4. Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121-1129. PubMed

5. Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):642-653. PubMed

6. Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric Symptoms in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: A 1-Year National Multicenter Study. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(5):954-965. PubMed

7. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on surgical mortality. Arch Surg. 2010;145(10):947-953. PubMed

8. Campbell NL, Khan BA, Farber M, et al. Improving delirium care in the intensive care unit: the design of a pragmatic study. Trials. 2011;12:139. PubMed

9. EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199-208. PubMed

10. Hirschfeld RM. The comorbidity of major depression and anxiety disorders: recognition and management in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(6):244–254. PubMed

11. Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu CF, et al. Prevalence of depression–PTSD comorbidity: implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):711–718. PubMed

12. Wolters AE, Peelen LM, Welling MC, et al. Long-term mental health problems after delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):1808-1813. PubMed

13. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. PubMed

14. Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1263-1271. PubMed

15. Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MA. CE: critical care recovery center: an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs. 2015;115(3):24-31. PubMed

The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors ranges from 17% to 44%.1-4 Psychiatric comorbidity, the presence of 2 or more psychiatric disorders, is highly prevalent in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome and is associated with higher mortality in postsurgical ICU survivors.5-7 While long-term cognitive impairment in patients with ICU delirium has been associated with poor quality of life (QoL),1 the effects of psychiatric comorbidity on QoL among similar patients are not as well understood. In this study, we examined whether psychiatric comorbidity was associated with poorer QoL in survivors of ICU delirium.

METHODS

We examined subjects who participated in the Pharmacologic Management of Delirium (PMD) clinical trial. This trial examined the efficacy of a pharmacological intervention for patients who developed ICU delirium at a local tertiary-care academic hospital.8 Out of 62 patients who participated in the follow-up of the PMD study, 58 completed QoL interviews and validated psychiatric screens (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9] for depression, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] questionnaire for anxiety, and the Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome [PTSS-10] questionnaire for PTSD) at 3 months after hospital discharge. High psychiatric comorbidity was defined as having significant symptoms for all 3 conditions (depression: PHQ-9 score ≥ 10; anxiety: GAD-7 ≥ 10; and PTSD: PTSS-10 > 35). No psychiatric morbidity was defined as having no significant symptoms for all 3 conditions. Low to moderate (low-moderate) psychiatric morbidity was defined as having symptoms for 1 to 2 conditions.

Participants also completed 2 complementary QoL measures: the EuroQol 5 dimensions questionnaire 3-level (EQ-5D-3L) Index and the EuroQol 5 dimensions Visual Analog Scale (EQ-5D-VAS).9 The EQ-5D-3L Index asks participants to rate themselves as having (1) no problems, (2) some problems, or (3) extreme problems on the following 5 scales: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The scores are then indexed against the US population to create a continuous index scale ranging from −0.11 to 1.00.

Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare dichotomous outcomes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous outcomes across the 3 psychiatric groups. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine whether psychiatric comorbidity in survivors of ICU delirium was associated with QoL measures. Models were adjusted for the following covariates: age, gender, Charlson Comorbidity Index, discharged to home, prior history of depression, and prior history of anxiety. To assess the relationship of psychiatric comorbidity with QoL, we chose the 2 continuous QoL measures as the outcome. Because we were interested in the effect of psychiatric burden on QoL, we used ANCOVA with QoL as the dependent variable and psychiatric burden as an independent variable. Pairwise comparisons were then performed when overall differences were significant (P < 0.05). We performed 2 separate sensitivity analyses. The first analysis looked solely at the subgroup of patients from the medical intensive care unit. We also recalculated the EQ-5D-3L index excluding the anxiety/depression item.

RESULTS

Nearly one-third of patients (18/58) had high psychiatric burden. The table looks at the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with high psychiatric comorbidity versus those of low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity and those with no psychiatric morbidity. Patient groups did not differ significantly in terms of demographics. For clinical characteristics, patients with high psychiatric comorbidity were more likely than patients with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity to have a prior history of depression (P < 0.05).

Patients with high psychiatric comorbidity were more likely to have a poorer QoL when compared with patients with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity and to those with no morbidity as measured by a lower EQ-5D-3L Index (no, 0.69 ± 0.25; low-moderate, 0.70 ± 0.19; high, 0.48 ± 0.24; P = 0.006) and EQ-5D-VAS (no, 67.0 ± 20.7; low-moderate, 76.6 ± 20.0; high, 50.8 ± 22.4; P = 0.004). After adjusting for covariates, patients with high psychiatric comorbidity had a poorer QoL compared with those with no morbidity or low-moderate comorbidity on the EQ-5D-3L Index (P = 0.017 for overall differences), whereas patients who had high psychiatric comorbidity had a poorer QoL compared to those with low-moderate comorbidity on the EQ-5D-VAS (P = 0.039 for overall differences; Figure). Subgroup analysis of MICU patients yielded similar results. Patients with high psychiatric burden had significantly poorer QoL as measured by the EQ-5D-3L (unadjusted P = 0.044, adjusted P = 0.003) and the EQ-5D-VAS (unadjusted P = 0.007, adjusted P = 0.021). After excluding the anxiety/depression item from the EQ-5D-3L, we observed similar differences (no, 0.71 ± 0.24; low-moderate, 0.75 ± 0.15; high, 0.58 ± 0.22; unadjusted P = 0.062; adjusted P = 0.040).

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

Psychiatric comorbidities in ICU survivors are common and pose a significant clinical issue. Patients with multiple psychiatric comorbidities can be more complicated to identify from a diagnostic standpoint and often require more prolonged, intensive mental health treatment when compared with patients with a single psychiatric disorder.10,11 Our study showed that high psychiatric comorbidity in survivors of ICU delirium is associated with a decreased QoL compared with those with no psychiatric comorbidity or with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity. This finding is consistent with previous studies in the general population that patients with multiple psychiatric comorbidities are associated with a poorer QoL compared with patients with a single psychiatric comorbidity.10,11

There is a pressing need to better characterize psychiatric comorbidities in ICU survivors because our current evidence suggests that the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities of ICU survivors is substantially higher than that of the general population. We found that nearly one-third of survivors of ICU delirium had comorbid depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms at 3 months. This is consistent with the few other studies of ICU survivors, which showed a prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity of 25% to 33%.5,12 These rates are substantially higher than the prevalence in the general population of 6%.13

The high rate of psychiatric comorbidities may render it difficult to effectively treat the mental health symptoms in ICU survivors.14 Treating multiple psychiatric comorbidities may also be especially challenging in survivors of ICU delirium because they have a high prevalence of cognitive impairment. Mental health treatments for patients with psychiatric disorders and comorbid cognitive impairment are limited. Better characterization of psychiatric comorbidity in ICU survivors, particularly those with ICU delirium, is vital to the development of more effective, bundled treatments for this population with multiple comorbidities.

Standardized screenings of ICU survivors at a high risk for psychiatric disorders, such as survivors of ICU delirium, may help to identify patients with comorbid psychiatric disorder symptoms and have them referred to appropriate treatment earlier with the hope of improving their QoL sooner. Although opportunities to deliver integrated outpatient collaborative mental health and medical care for a subspecialty population are limited, one potential model of care would be to utilize a collaborative-care model in an ICU survivor clinic.15

Strengths of our study include the examination of psychiatric comorbidities in survivors of ICU delirium, who often have a poor QoL. A deeper understanding of psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship with QoL is needed to better understand how to deliver more effective treatments for these survivors. Limitations include the small sample size, a one-time measurement of psychiatric comorbidities at the 3-month follow-up based on screenings tools, and a lack of objective measures of physical functioning to determine the effects of psychiatric comorbidities on physical functioning. There may also have been differences in how patients with no psychiatric comorbidity responded to the EQ-5D-VAS as a result of premorbid differences (eg, they were healthier prior to their ICU stay and perceived their survivor status more negatively). This may explain why we did not see a statistically significant difference between no psychiatric comorbidity and high psychiatric comorbidity groups on the EQ-5D-VAS. Nevertheless, we did see a difference between the low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity group on EQ-5D-VAS and differences between the no comorbidity and low-moderate comorbidity groups versus the high comorbidity group on the EQ-5D-3L. Finally, data about psychiatric history and QoL prior to ICU hospitalization were limited. Therefore, truly determining incidence versus prevalence of post-ICU comorbidities and whether psychiatric symptoms and its effects on QoL were due to ICU hospitalization or to premorbid psychiatric symptoms is difficult.

Our study demonstrated that in survivors of ICU delirium, higher comorbidity of psychiatric symptoms was associated with poorer QoL. Future studies will need to confirm these findings. We will also need to identify potentially reversible risk factors for psychiatric comorbidity and poorer QoL and develop treatments to effectively target the mental health symptoms of survivors of ICU delirium.

Disclosure

Grant support: The PMD trial is funded through the National Institutes of Health grant R01AG054205-02. SW is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133. AP is supported by CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00, Indiana CTSI, and NIA R01AG054205-02. SG is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133, NIA 5R01AG045350, and NIA R01AG054205-02. SK is supported by NHBLI 5T32HL091816-07. MB is supported by NIA R01 AG040220-05, AHRQ P30 HS024384-02, CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00, NIA R01 AG030618-05A1 and NIA R01AG054205-02. BK is supported by NIA K23-AG043476 and NHLBI R01HL131730. The funding agency had no role in the development of the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript development, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Conflicts of interest include MB, SG, and AP being funded by NIA R01AG054205-02 for the PMD study.

The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors ranges from 17% to 44%.1-4 Psychiatric comorbidity, the presence of 2 or more psychiatric disorders, is highly prevalent in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome and is associated with higher mortality in postsurgical ICU survivors.5-7 While long-term cognitive impairment in patients with ICU delirium has been associated with poor quality of life (QoL),1 the effects of psychiatric comorbidity on QoL among similar patients are not as well understood. In this study, we examined whether psychiatric comorbidity was associated with poorer QoL in survivors of ICU delirium.

METHODS

We examined subjects who participated in the Pharmacologic Management of Delirium (PMD) clinical trial. This trial examined the efficacy of a pharmacological intervention for patients who developed ICU delirium at a local tertiary-care academic hospital.8 Out of 62 patients who participated in the follow-up of the PMD study, 58 completed QoL interviews and validated psychiatric screens (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9] for depression, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] questionnaire for anxiety, and the Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome [PTSS-10] questionnaire for PTSD) at 3 months after hospital discharge. High psychiatric comorbidity was defined as having significant symptoms for all 3 conditions (depression: PHQ-9 score ≥ 10; anxiety: GAD-7 ≥ 10; and PTSD: PTSS-10 > 35). No psychiatric morbidity was defined as having no significant symptoms for all 3 conditions. Low to moderate (low-moderate) psychiatric morbidity was defined as having symptoms for 1 to 2 conditions.

Participants also completed 2 complementary QoL measures: the EuroQol 5 dimensions questionnaire 3-level (EQ-5D-3L) Index and the EuroQol 5 dimensions Visual Analog Scale (EQ-5D-VAS).9 The EQ-5D-3L Index asks participants to rate themselves as having (1) no problems, (2) some problems, or (3) extreme problems on the following 5 scales: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The scores are then indexed against the US population to create a continuous index scale ranging from −0.11 to 1.00.

Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare dichotomous outcomes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous outcomes across the 3 psychiatric groups. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine whether psychiatric comorbidity in survivors of ICU delirium was associated with QoL measures. Models were adjusted for the following covariates: age, gender, Charlson Comorbidity Index, discharged to home, prior history of depression, and prior history of anxiety. To assess the relationship of psychiatric comorbidity with QoL, we chose the 2 continuous QoL measures as the outcome. Because we were interested in the effect of psychiatric burden on QoL, we used ANCOVA with QoL as the dependent variable and psychiatric burden as an independent variable. Pairwise comparisons were then performed when overall differences were significant (P < 0.05). We performed 2 separate sensitivity analyses. The first analysis looked solely at the subgroup of patients from the medical intensive care unit. We also recalculated the EQ-5D-3L index excluding the anxiety/depression item.

RESULTS

Nearly one-third of patients (18/58) had high psychiatric burden. The table looks at the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with high psychiatric comorbidity versus those of low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity and those with no psychiatric morbidity. Patient groups did not differ significantly in terms of demographics. For clinical characteristics, patients with high psychiatric comorbidity were more likely than patients with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity to have a prior history of depression (P < 0.05).

Patients with high psychiatric comorbidity were more likely to have a poorer QoL when compared with patients with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity and to those with no morbidity as measured by a lower EQ-5D-3L Index (no, 0.69 ± 0.25; low-moderate, 0.70 ± 0.19; high, 0.48 ± 0.24; P = 0.006) and EQ-5D-VAS (no, 67.0 ± 20.7; low-moderate, 76.6 ± 20.0; high, 50.8 ± 22.4; P = 0.004). After adjusting for covariates, patients with high psychiatric comorbidity had a poorer QoL compared with those with no morbidity or low-moderate comorbidity on the EQ-5D-3L Index (P = 0.017 for overall differences), whereas patients who had high psychiatric comorbidity had a poorer QoL compared to those with low-moderate comorbidity on the EQ-5D-VAS (P = 0.039 for overall differences; Figure). Subgroup analysis of MICU patients yielded similar results. Patients with high psychiatric burden had significantly poorer QoL as measured by the EQ-5D-3L (unadjusted P = 0.044, adjusted P = 0.003) and the EQ-5D-VAS (unadjusted P = 0.007, adjusted P = 0.021). After excluding the anxiety/depression item from the EQ-5D-3L, we observed similar differences (no, 0.71 ± 0.24; low-moderate, 0.75 ± 0.15; high, 0.58 ± 0.22; unadjusted P = 0.062; adjusted P = 0.040).

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

Psychiatric comorbidities in ICU survivors are common and pose a significant clinical issue. Patients with multiple psychiatric comorbidities can be more complicated to identify from a diagnostic standpoint and often require more prolonged, intensive mental health treatment when compared with patients with a single psychiatric disorder.10,11 Our study showed that high psychiatric comorbidity in survivors of ICU delirium is associated with a decreased QoL compared with those with no psychiatric comorbidity or with low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity. This finding is consistent with previous studies in the general population that patients with multiple psychiatric comorbidities are associated with a poorer QoL compared with patients with a single psychiatric comorbidity.10,11

There is a pressing need to better characterize psychiatric comorbidities in ICU survivors because our current evidence suggests that the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities of ICU survivors is substantially higher than that of the general population. We found that nearly one-third of survivors of ICU delirium had comorbid depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms at 3 months. This is consistent with the few other studies of ICU survivors, which showed a prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity of 25% to 33%.5,12 These rates are substantially higher than the prevalence in the general population of 6%.13

The high rate of psychiatric comorbidities may render it difficult to effectively treat the mental health symptoms in ICU survivors.14 Treating multiple psychiatric comorbidities may also be especially challenging in survivors of ICU delirium because they have a high prevalence of cognitive impairment. Mental health treatments for patients with psychiatric disorders and comorbid cognitive impairment are limited. Better characterization of psychiatric comorbidity in ICU survivors, particularly those with ICU delirium, is vital to the development of more effective, bundled treatments for this population with multiple comorbidities.

Standardized screenings of ICU survivors at a high risk for psychiatric disorders, such as survivors of ICU delirium, may help to identify patients with comorbid psychiatric disorder symptoms and have them referred to appropriate treatment earlier with the hope of improving their QoL sooner. Although opportunities to deliver integrated outpatient collaborative mental health and medical care for a subspecialty population are limited, one potential model of care would be to utilize a collaborative-care model in an ICU survivor clinic.15

Strengths of our study include the examination of psychiatric comorbidities in survivors of ICU delirium, who often have a poor QoL. A deeper understanding of psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship with QoL is needed to better understand how to deliver more effective treatments for these survivors. Limitations include the small sample size, a one-time measurement of psychiatric comorbidities at the 3-month follow-up based on screenings tools, and a lack of objective measures of physical functioning to determine the effects of psychiatric comorbidities on physical functioning. There may also have been differences in how patients with no psychiatric comorbidity responded to the EQ-5D-VAS as a result of premorbid differences (eg, they were healthier prior to their ICU stay and perceived their survivor status more negatively). This may explain why we did not see a statistically significant difference between no psychiatric comorbidity and high psychiatric comorbidity groups on the EQ-5D-VAS. Nevertheless, we did see a difference between the low-moderate psychiatric comorbidity group on EQ-5D-VAS and differences between the no comorbidity and low-moderate comorbidity groups versus the high comorbidity group on the EQ-5D-3L. Finally, data about psychiatric history and QoL prior to ICU hospitalization were limited. Therefore, truly determining incidence versus prevalence of post-ICU comorbidities and whether psychiatric symptoms and its effects on QoL were due to ICU hospitalization or to premorbid psychiatric symptoms is difficult.

Our study demonstrated that in survivors of ICU delirium, higher comorbidity of psychiatric symptoms was associated with poorer QoL. Future studies will need to confirm these findings. We will also need to identify potentially reversible risk factors for psychiatric comorbidity and poorer QoL and develop treatments to effectively target the mental health symptoms of survivors of ICU delirium.

Disclosure

Grant support: The PMD trial is funded through the National Institutes of Health grant R01AG054205-02. SW is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133. AP is supported by CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00, Indiana CTSI, and NIA R01AG054205-02. SG is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133, NIA 5R01AG045350, and NIA R01AG054205-02. SK is supported by NHBLI 5T32HL091816-07. MB is supported by NIA R01 AG040220-05, AHRQ P30 HS024384-02, CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00, NIA R01 AG030618-05A1 and NIA R01AG054205-02. BK is supported by NIA K23-AG043476 and NHLBI R01HL131730. The funding agency had no role in the development of the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript development, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Conflicts of interest include MB, SG, and AP being funded by NIA R01AG054205-02 for the PMD study.

1. Jutte JE, Erb CT, Jackson JC. Physical, cognitive, and psychological disability following critical illness: what is the risk? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(6):943-958. PubMed

2. Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:23-29. PubMed

3. Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1744-1753. PubMed

4. Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121-1129. PubMed

5. Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):642-653. PubMed

6. Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric Symptoms in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: A 1-Year National Multicenter Study. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(5):954-965. PubMed

7. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on surgical mortality. Arch Surg. 2010;145(10):947-953. PubMed

8. Campbell NL, Khan BA, Farber M, et al. Improving delirium care in the intensive care unit: the design of a pragmatic study. Trials. 2011;12:139. PubMed

9. EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199-208. PubMed

10. Hirschfeld RM. The comorbidity of major depression and anxiety disorders: recognition and management in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(6):244–254. PubMed

11. Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu CF, et al. Prevalence of depression–PTSD comorbidity: implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):711–718. PubMed

12. Wolters AE, Peelen LM, Welling MC, et al. Long-term mental health problems after delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):1808-1813. PubMed

13. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. PubMed

14. Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1263-1271. PubMed

15. Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MA. CE: critical care recovery center: an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs. 2015;115(3):24-31. PubMed

1. Jutte JE, Erb CT, Jackson JC. Physical, cognitive, and psychological disability following critical illness: what is the risk? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(6):943-958. PubMed

2. Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:23-29. PubMed

3. Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1744-1753. PubMed

4. Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121-1129. PubMed

5. Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):642-653. PubMed

6. Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric Symptoms in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: A 1-Year National Multicenter Study. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(5):954-965. PubMed

7. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on surgical mortality. Arch Surg. 2010;145(10):947-953. PubMed

8. Campbell NL, Khan BA, Farber M, et al. Improving delirium care in the intensive care unit: the design of a pragmatic study. Trials. 2011;12:139. PubMed

9. EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199-208. PubMed

10. Hirschfeld RM. The comorbidity of major depression and anxiety disorders: recognition and management in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(6):244–254. PubMed

11. Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu CF, et al. Prevalence of depression–PTSD comorbidity: implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):711–718. PubMed

12. Wolters AE, Peelen LM, Welling MC, et al. Long-term mental health problems after delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):1808-1813. PubMed

13. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. PubMed

14. Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1263-1271. PubMed

15. Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MA. CE: critical care recovery center: an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs. 2015;115(3):24-31. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Antidepressant Use and Depressive Symptoms in Intensive Care Unit Survivors

As the number of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors has steadily increased over the past few decades, there is growing awareness of the long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments after ICU hospitalization, collectively known as post–intensive care syndrome (PICS).1 Systematic reviews based mostly on research studies suggest that the prevalence of depressive symptoms 2-12 months after ICU discharge is nearly 30%.2-5 Due to the scarcity of established models of care for ICU survivors, there is limited characterization of depressive symptoms and antidepressant regimens in this clinical population. The Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) at Eskenazi Hospital is one of the first ICU survivor clinics in the United States and targets a racially diverse, underserved population in the Indianapolis metropolitan area.6 In this study, we examined whether patients had depressive symptoms at their initial CCRC visit, and whether the risk factors for depressive symptoms differed if they were on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit.

METHODS

Referral criteria to the CCRC were 18 years or older, admitted to the Eskenazi ICU, were on mechanical ventilation or delirious for ≥48 hours (major risk factors for the development of PICS), and recommended for follow-up by a critical care physician. The exclusion criterion included was enrollment in hospice or palliative care services. Institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct retrospective analyses of de-identified clinical data. Medical history and medication lists were collected from patients, informal caregivers, and electronic medical records.

Two hundred thirty-three patients were seen in the CCRC from July 2011 to August 2016. Two hundred four patients rated symptoms of depression with either the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; N = 99) or Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-30; N = 105) at their initial visit to the CCRC prior to receiving any treatment at the CCRC. Twenty-nine patients who did not complete depression questionnaires were excluded from the analyses. Patients with PHQ-9 score ≥10 or GDS score ≥20 were categorized as having moderate to severe depressive symptoms.7,8

Electronic medical records were reviewed to determine whether patients were on an antidepressant at hospital admission, hospital discharge, and the initial CCRC visit prior to any treatment in the CCRC. Patients who were on a tricyclic antidepressant, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (eg, mirtazapine), or norepinephrine and dopaminergic reuptake inhibitor (eg, bupropion) at any dose were designated as being on an antidepressant. Prescribers of antidepressants included primary care providers, clinical providers during their hospital stay, and various outpatient subspecialists other than those in the CCRC.

We then examined whether the risk factors for depressive symptoms differed if patients were on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics between depressed and nondepressed patients not on an antidepressant. We repeated these analyses for those on an antidepressant. Dichotomous outcomes were compared using chi-square testing, and two-way Student t tests for continuous outcomes. Demographic and clinical variables with P < 0.1 were included as covariates in a logistic regression model for depressive symptoms separately for those not an antidepressant and those on an antidepressant. History of depression was not included as a covariate because it is highly collinear with post-ICU depression.

RESULTS

Two hundred four ICU survivors in this study reflected a racially diverse and underserved population (monthly income $745.3 ± $931.5). Although most had respiratory failure and/or delirium during their hospital stay, 94.1% (N = 160) mostly lived independently after discharge. Nearly one-third of patients (N = 69) were on at least 1 antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit. Of these 69 patients, 60.9% (N = 42) had an antidepressant prescription on hospital admission, and 60.9% (N = 42) had an antidepressant prescription on hospital discharge.

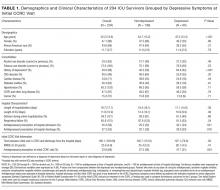

We first compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without depressive symptoms at their initial CCRC visit. Patients with depressive symptoms were younger, less likely to have cardiac disease, more likely to have a history of depression, more likely to have been prescribed an antidepressant on hospital admission, more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant on hospital discharge, and more likely to be on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit (Table 1).

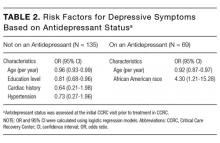

Patients with depressive symptoms on an antidepressant (n = 65) were younger and more likely to be African American (borderline significance; Supplementary Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression showed that both younger age (OR = 0.92 per year, P = 0.003) and African American race (OR = 4.3, P = 0.024) remained significantly associated with depressive symptoms (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that about one-third of our ICU survivor clinical cohort had untreated or inadequately treated depressive symptoms at their CCRC initial visit. Many patients with depressive symptoms had a history of depression and/or antidepressant prescription on hospital admission. This suggests that pre-ICU depression is a major contributor to post-ICU depression. These findings are consistent with the results of a large retrospective analysis of Danish ICU survivors that found that patients were more likely to have premorbid psychiatric diagnoses, compared with the general population.9 Another ICU survivor research study that excluded patients who were on antidepressants prior to ICU hospitalization found that 49% of these patients were on an antidepressant after their ICU stay.10 Our much lower rate of patients on an antidepressant after their ICU stay may reflect the differences between patient populations, differences in healthcare systems, and differences in clinician prescribing practices.

Younger age was associated with a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms independent of antidepressant status. Findings about the relationship between age and post-ICU depression have varied. The Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors group found that older age was associated with more depressive symptoms at 12 months postdischarge.11 On the other hand, a systematic review of post-ICU depression did not find any relationship between age and post-ICU depression.2,3 These differences may be due in part to demographic variations in cohorts.

Our logistic regression models suggest that there may also be different risk factors in patients who had untreated vs inadequately treated depressive symptoms. Patients who were not on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit were more likely to have a lower level of education. This is consistent with the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys study, which showed that adults with less than a high school education were less likely to receive depression treatment.12 In patients who were on antidepressants at their initial CCRC visit, African Americans were more likely to have depressive symptoms. Possible reasons may include differences in receiving guideline-concordant antidepressant medication treatment, access to mental health subspecialty services, higher prevalence of treatment refractory depression, and differences in responses to antidepressant treatments.13,14

Strengths of our study include detailed characterization for a fairly large ICU survivor clinic population and a racially diverse cohort. To the best of our knowledge, our study is also the first to examine whether there may be different risk factors for depressive symptoms based on antidepressant status. Limitations include the lack of information about nonpharmacologic antidepressant treatment and the inability to assess whether noncompliance, insufficient dose, or insufficient time on antidepressants contributed to inadequate antidepressant treatment. Antidepressants may have also been prescribed for other purposes such as smoking cessation, neuropathic pain, and migraine headaches. However, because 72.4% of patients on antidepressants had a history of depression, it is likely that most of them were on antidepressants to treat depression.

Other limitations include potential biases in our clinical cohort. Over the last 5 years, the CCRC has provided care to more than 200 ICU survivors. With 1100 mechanically ventilated admissions per year, only 1.8% of survivors are seen. The referral criteria for the CCRC is a major source of selection bias, which likely overrepresents PICS. Because patients are seen in the CCRC about 3 months after hospital discharge, there is also informant censoring due to death. Physically sicker survivors in nursing home facilities were less likely to be included. Finally, the small cohort size may have resulted in an underpowered study.

Future studies will need to confirm our findings about the high prevalence of post-ICU depression and different responses to antidepressant medications by certain groups. Pre-ICU depression, lack of antidepressant treatment, and inadequate antidepressant treatment are major causes of post-ICU depression. Currently, the CCRC offers pharmacotherapy, problem-solving therapy, or referral to mental health specialists to treat patients with depressive symptoms. ICU survivor clinics, such as the CCRC, may become important settings that allow for increased access to depression treatment for those at higher risk for post-ICU depression as well as the testing of new antidepressant regimens for those with inadequately treated depression.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Adil Sheikh for assistance with data entry and Cynthia Reynolds for her clinical services. Grant support: The Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) is supported by Eskenazi Health Services. SW is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133. SG is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133 and NIA 5R01AG045350. SK is supported by NHBLI 5T32HL091816-07. MB is supported by NIA R01 AG040220-05, AHRQ P30 HS024384-02, CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00 and NIA R01 AG030618-05A1. BK is supported by NIA K23-AG043476 and NHLBI R01HL131730.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest. None of the above NIH grants supported the CCRC or this work.

1. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502-509. PubMed

2. Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:796-809. PubMed

3. Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1744-1753. PubMed

4. Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors: A 1-year national multicenter study. Crit Care Med 2016;44:954-965. PubMed

5. Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:642-653. PubMed

6. Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MA. CE: critical care recovery center: an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs. 2015;115:24-31. PubMed

7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. PubMed

8. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17:37-49. PubMed

9. Wuns ch H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and psychoactive medication use among nonsurgical critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation. JAMA. 2014;311:1133-1142. PubMed

10. Weinert C, Meller W. Epidemiology of depression and antidepressant therapy after acute respiratory failure. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(5):399-407. PubMed

11. Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369-379. PubMed

12. Olfson M, Blanco C, Marcus SC. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1482-1491. PubMed

13. González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:37-46. PubMed

14. Bailey RK, Patel M, Barker NC, Ali S, Jabeen S. Major depressive disorder in the African American population. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:548-557. PubMed

As the number of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors has steadily increased over the past few decades, there is growing awareness of the long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments after ICU hospitalization, collectively known as post–intensive care syndrome (PICS).1 Systematic reviews based mostly on research studies suggest that the prevalence of depressive symptoms 2-12 months after ICU discharge is nearly 30%.2-5 Due to the scarcity of established models of care for ICU survivors, there is limited characterization of depressive symptoms and antidepressant regimens in this clinical population. The Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) at Eskenazi Hospital is one of the first ICU survivor clinics in the United States and targets a racially diverse, underserved population in the Indianapolis metropolitan area.6 In this study, we examined whether patients had depressive symptoms at their initial CCRC visit, and whether the risk factors for depressive symptoms differed if they were on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit.

METHODS

Referral criteria to the CCRC were 18 years or older, admitted to the Eskenazi ICU, were on mechanical ventilation or delirious for ≥48 hours (major risk factors for the development of PICS), and recommended for follow-up by a critical care physician. The exclusion criterion included was enrollment in hospice or palliative care services. Institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct retrospective analyses of de-identified clinical data. Medical history and medication lists were collected from patients, informal caregivers, and electronic medical records.

Two hundred thirty-three patients were seen in the CCRC from July 2011 to August 2016. Two hundred four patients rated symptoms of depression with either the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; N = 99) or Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-30; N = 105) at their initial visit to the CCRC prior to receiving any treatment at the CCRC. Twenty-nine patients who did not complete depression questionnaires were excluded from the analyses. Patients with PHQ-9 score ≥10 or GDS score ≥20 were categorized as having moderate to severe depressive symptoms.7,8

Electronic medical records were reviewed to determine whether patients were on an antidepressant at hospital admission, hospital discharge, and the initial CCRC visit prior to any treatment in the CCRC. Patients who were on a tricyclic antidepressant, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (eg, mirtazapine), or norepinephrine and dopaminergic reuptake inhibitor (eg, bupropion) at any dose were designated as being on an antidepressant. Prescribers of antidepressants included primary care providers, clinical providers during their hospital stay, and various outpatient subspecialists other than those in the CCRC.

We then examined whether the risk factors for depressive symptoms differed if patients were on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics between depressed and nondepressed patients not on an antidepressant. We repeated these analyses for those on an antidepressant. Dichotomous outcomes were compared using chi-square testing, and two-way Student t tests for continuous outcomes. Demographic and clinical variables with P < 0.1 were included as covariates in a logistic regression model for depressive symptoms separately for those not an antidepressant and those on an antidepressant. History of depression was not included as a covariate because it is highly collinear with post-ICU depression.

RESULTS

Two hundred four ICU survivors in this study reflected a racially diverse and underserved population (monthly income $745.3 ± $931.5). Although most had respiratory failure and/or delirium during their hospital stay, 94.1% (N = 160) mostly lived independently after discharge. Nearly one-third of patients (N = 69) were on at least 1 antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit. Of these 69 patients, 60.9% (N = 42) had an antidepressant prescription on hospital admission, and 60.9% (N = 42) had an antidepressant prescription on hospital discharge.

We first compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without depressive symptoms at their initial CCRC visit. Patients with depressive symptoms were younger, less likely to have cardiac disease, more likely to have a history of depression, more likely to have been prescribed an antidepressant on hospital admission, more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant on hospital discharge, and more likely to be on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit (Table 1).

Patients with depressive symptoms on an antidepressant (n = 65) were younger and more likely to be African American (borderline significance; Supplementary Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression showed that both younger age (OR = 0.92 per year, P = 0.003) and African American race (OR = 4.3, P = 0.024) remained significantly associated with depressive symptoms (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that about one-third of our ICU survivor clinical cohort had untreated or inadequately treated depressive symptoms at their CCRC initial visit. Many patients with depressive symptoms had a history of depression and/or antidepressant prescription on hospital admission. This suggests that pre-ICU depression is a major contributor to post-ICU depression. These findings are consistent with the results of a large retrospective analysis of Danish ICU survivors that found that patients were more likely to have premorbid psychiatric diagnoses, compared with the general population.9 Another ICU survivor research study that excluded patients who were on antidepressants prior to ICU hospitalization found that 49% of these patients were on an antidepressant after their ICU stay.10 Our much lower rate of patients on an antidepressant after their ICU stay may reflect the differences between patient populations, differences in healthcare systems, and differences in clinician prescribing practices.

Younger age was associated with a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms independent of antidepressant status. Findings about the relationship between age and post-ICU depression have varied. The Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors group found that older age was associated with more depressive symptoms at 12 months postdischarge.11 On the other hand, a systematic review of post-ICU depression did not find any relationship between age and post-ICU depression.2,3 These differences may be due in part to demographic variations in cohorts.

Our logistic regression models suggest that there may also be different risk factors in patients who had untreated vs inadequately treated depressive symptoms. Patients who were not on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit were more likely to have a lower level of education. This is consistent with the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys study, which showed that adults with less than a high school education were less likely to receive depression treatment.12 In patients who were on antidepressants at their initial CCRC visit, African Americans were more likely to have depressive symptoms. Possible reasons may include differences in receiving guideline-concordant antidepressant medication treatment, access to mental health subspecialty services, higher prevalence of treatment refractory depression, and differences in responses to antidepressant treatments.13,14

Strengths of our study include detailed characterization for a fairly large ICU survivor clinic population and a racially diverse cohort. To the best of our knowledge, our study is also the first to examine whether there may be different risk factors for depressive symptoms based on antidepressant status. Limitations include the lack of information about nonpharmacologic antidepressant treatment and the inability to assess whether noncompliance, insufficient dose, or insufficient time on antidepressants contributed to inadequate antidepressant treatment. Antidepressants may have also been prescribed for other purposes such as smoking cessation, neuropathic pain, and migraine headaches. However, because 72.4% of patients on antidepressants had a history of depression, it is likely that most of them were on antidepressants to treat depression.

Other limitations include potential biases in our clinical cohort. Over the last 5 years, the CCRC has provided care to more than 200 ICU survivors. With 1100 mechanically ventilated admissions per year, only 1.8% of survivors are seen. The referral criteria for the CCRC is a major source of selection bias, which likely overrepresents PICS. Because patients are seen in the CCRC about 3 months after hospital discharge, there is also informant censoring due to death. Physically sicker survivors in nursing home facilities were less likely to be included. Finally, the small cohort size may have resulted in an underpowered study.

Future studies will need to confirm our findings about the high prevalence of post-ICU depression and different responses to antidepressant medications by certain groups. Pre-ICU depression, lack of antidepressant treatment, and inadequate antidepressant treatment are major causes of post-ICU depression. Currently, the CCRC offers pharmacotherapy, problem-solving therapy, or referral to mental health specialists to treat patients with depressive symptoms. ICU survivor clinics, such as the CCRC, may become important settings that allow for increased access to depression treatment for those at higher risk for post-ICU depression as well as the testing of new antidepressant regimens for those with inadequately treated depression.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Adil Sheikh for assistance with data entry and Cynthia Reynolds for her clinical services. Grant support: The Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) is supported by Eskenazi Health Services. SW is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133. SG is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133 and NIA 5R01AG045350. SK is supported by NHBLI 5T32HL091816-07. MB is supported by NIA R01 AG040220-05, AHRQ P30 HS024384-02, CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00 and NIA R01 AG030618-05A1. BK is supported by NIA K23-AG043476 and NHLBI R01HL131730.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest. None of the above NIH grants supported the CCRC or this work.

As the number of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors has steadily increased over the past few decades, there is growing awareness of the long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments after ICU hospitalization, collectively known as post–intensive care syndrome (PICS).1 Systematic reviews based mostly on research studies suggest that the prevalence of depressive symptoms 2-12 months after ICU discharge is nearly 30%.2-5 Due to the scarcity of established models of care for ICU survivors, there is limited characterization of depressive symptoms and antidepressant regimens in this clinical population. The Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) at Eskenazi Hospital is one of the first ICU survivor clinics in the United States and targets a racially diverse, underserved population in the Indianapolis metropolitan area.6 In this study, we examined whether patients had depressive symptoms at their initial CCRC visit, and whether the risk factors for depressive symptoms differed if they were on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit.

METHODS

Referral criteria to the CCRC were 18 years or older, admitted to the Eskenazi ICU, were on mechanical ventilation or delirious for ≥48 hours (major risk factors for the development of PICS), and recommended for follow-up by a critical care physician. The exclusion criterion included was enrollment in hospice or palliative care services. Institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct retrospective analyses of de-identified clinical data. Medical history and medication lists were collected from patients, informal caregivers, and electronic medical records.

Two hundred thirty-three patients were seen in the CCRC from July 2011 to August 2016. Two hundred four patients rated symptoms of depression with either the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; N = 99) or Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-30; N = 105) at their initial visit to the CCRC prior to receiving any treatment at the CCRC. Twenty-nine patients who did not complete depression questionnaires were excluded from the analyses. Patients with PHQ-9 score ≥10 or GDS score ≥20 were categorized as having moderate to severe depressive symptoms.7,8

Electronic medical records were reviewed to determine whether patients were on an antidepressant at hospital admission, hospital discharge, and the initial CCRC visit prior to any treatment in the CCRC. Patients who were on a tricyclic antidepressant, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (eg, mirtazapine), or norepinephrine and dopaminergic reuptake inhibitor (eg, bupropion) at any dose were designated as being on an antidepressant. Prescribers of antidepressants included primary care providers, clinical providers during their hospital stay, and various outpatient subspecialists other than those in the CCRC.

We then examined whether the risk factors for depressive symptoms differed if patients were on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics between depressed and nondepressed patients not on an antidepressant. We repeated these analyses for those on an antidepressant. Dichotomous outcomes were compared using chi-square testing, and two-way Student t tests for continuous outcomes. Demographic and clinical variables with P < 0.1 were included as covariates in a logistic regression model for depressive symptoms separately for those not an antidepressant and those on an antidepressant. History of depression was not included as a covariate because it is highly collinear with post-ICU depression.

RESULTS

Two hundred four ICU survivors in this study reflected a racially diverse and underserved population (monthly income $745.3 ± $931.5). Although most had respiratory failure and/or delirium during their hospital stay, 94.1% (N = 160) mostly lived independently after discharge. Nearly one-third of patients (N = 69) were on at least 1 antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit. Of these 69 patients, 60.9% (N = 42) had an antidepressant prescription on hospital admission, and 60.9% (N = 42) had an antidepressant prescription on hospital discharge.

We first compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without depressive symptoms at their initial CCRC visit. Patients with depressive symptoms were younger, less likely to have cardiac disease, more likely to have a history of depression, more likely to have been prescribed an antidepressant on hospital admission, more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant on hospital discharge, and more likely to be on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit (Table 1).

Patients with depressive symptoms on an antidepressant (n = 65) were younger and more likely to be African American (borderline significance; Supplementary Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression showed that both younger age (OR = 0.92 per year, P = 0.003) and African American race (OR = 4.3, P = 0.024) remained significantly associated with depressive symptoms (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that about one-third of our ICU survivor clinical cohort had untreated or inadequately treated depressive symptoms at their CCRC initial visit. Many patients with depressive symptoms had a history of depression and/or antidepressant prescription on hospital admission. This suggests that pre-ICU depression is a major contributor to post-ICU depression. These findings are consistent with the results of a large retrospective analysis of Danish ICU survivors that found that patients were more likely to have premorbid psychiatric diagnoses, compared with the general population.9 Another ICU survivor research study that excluded patients who were on antidepressants prior to ICU hospitalization found that 49% of these patients were on an antidepressant after their ICU stay.10 Our much lower rate of patients on an antidepressant after their ICU stay may reflect the differences between patient populations, differences in healthcare systems, and differences in clinician prescribing practices.

Younger age was associated with a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms independent of antidepressant status. Findings about the relationship between age and post-ICU depression have varied. The Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors group found that older age was associated with more depressive symptoms at 12 months postdischarge.11 On the other hand, a systematic review of post-ICU depression did not find any relationship between age and post-ICU depression.2,3 These differences may be due in part to demographic variations in cohorts.

Our logistic regression models suggest that there may also be different risk factors in patients who had untreated vs inadequately treated depressive symptoms. Patients who were not on an antidepressant at their initial CCRC visit were more likely to have a lower level of education. This is consistent with the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys study, which showed that adults with less than a high school education were less likely to receive depression treatment.12 In patients who were on antidepressants at their initial CCRC visit, African Americans were more likely to have depressive symptoms. Possible reasons may include differences in receiving guideline-concordant antidepressant medication treatment, access to mental health subspecialty services, higher prevalence of treatment refractory depression, and differences in responses to antidepressant treatments.13,14

Strengths of our study include detailed characterization for a fairly large ICU survivor clinic population and a racially diverse cohort. To the best of our knowledge, our study is also the first to examine whether there may be different risk factors for depressive symptoms based on antidepressant status. Limitations include the lack of information about nonpharmacologic antidepressant treatment and the inability to assess whether noncompliance, insufficient dose, or insufficient time on antidepressants contributed to inadequate antidepressant treatment. Antidepressants may have also been prescribed for other purposes such as smoking cessation, neuropathic pain, and migraine headaches. However, because 72.4% of patients on antidepressants had a history of depression, it is likely that most of them were on antidepressants to treat depression.

Other limitations include potential biases in our clinical cohort. Over the last 5 years, the CCRC has provided care to more than 200 ICU survivors. With 1100 mechanically ventilated admissions per year, only 1.8% of survivors are seen. The referral criteria for the CCRC is a major source of selection bias, which likely overrepresents PICS. Because patients are seen in the CCRC about 3 months after hospital discharge, there is also informant censoring due to death. Physically sicker survivors in nursing home facilities were less likely to be included. Finally, the small cohort size may have resulted in an underpowered study.

Future studies will need to confirm our findings about the high prevalence of post-ICU depression and different responses to antidepressant medications by certain groups. Pre-ICU depression, lack of antidepressant treatment, and inadequate antidepressant treatment are major causes of post-ICU depression. Currently, the CCRC offers pharmacotherapy, problem-solving therapy, or referral to mental health specialists to treat patients with depressive symptoms. ICU survivor clinics, such as the CCRC, may become important settings that allow for increased access to depression treatment for those at higher risk for post-ICU depression as well as the testing of new antidepressant regimens for those with inadequately treated depression.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Adil Sheikh for assistance with data entry and Cynthia Reynolds for her clinical services. Grant support: The Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) is supported by Eskenazi Health Services. SW is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133. SG is supported by NIA 2P30AG010133 and NIA 5R01AG045350. SK is supported by NHBLI 5T32HL091816-07. MB is supported by NIA R01 AG040220-05, AHRQ P30 HS024384-02, CMS 1 L1 CMS331444-02-00 and NIA R01 AG030618-05A1. BK is supported by NIA K23-AG043476 and NHLBI R01HL131730.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest. None of the above NIH grants supported the CCRC or this work.

1. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502-509. PubMed

2. Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:796-809. PubMed

3. Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1744-1753. PubMed

4. Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors: A 1-year national multicenter study. Crit Care Med 2016;44:954-965. PubMed

5. Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:642-653. PubMed

6. Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MA. CE: critical care recovery center: an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs. 2015;115:24-31. PubMed

7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. PubMed

8. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17:37-49. PubMed

9. Wuns ch H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and psychoactive medication use among nonsurgical critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation. JAMA. 2014;311:1133-1142. PubMed

10. Weinert C, Meller W. Epidemiology of depression and antidepressant therapy after acute respiratory failure. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(5):399-407. PubMed

11. Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369-379. PubMed

12. Olfson M, Blanco C, Marcus SC. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1482-1491. PubMed

13. González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:37-46. PubMed

14. Bailey RK, Patel M, Barker NC, Ali S, Jabeen S. Major depressive disorder in the African American population. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:548-557. PubMed

1. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502-509. PubMed

2. Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:796-809. PubMed

3. Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1744-1753. PubMed

4. Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors: A 1-year national multicenter study. Crit Care Med 2016;44:954-965. PubMed

5. Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:642-653. PubMed

6. Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MA. CE: critical care recovery center: an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs. 2015;115:24-31. PubMed

7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. PubMed

8. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17:37-49. PubMed

9. Wuns ch H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and psychoactive medication use among nonsurgical critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation. JAMA. 2014;311:1133-1142. PubMed

10. Weinert C, Meller W. Epidemiology of depression and antidepressant therapy after acute respiratory failure. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(5):399-407. PubMed

11. Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369-379. PubMed

12. Olfson M, Blanco C, Marcus SC. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1482-1491. PubMed