User login

Emergency Imaging

30-year-old woman with a history of alcoholism and anxiety presented to the ED for evaluation of abdominal distension and pain. She reported new social stressors at home and increased alcohol consumption. She also noted gradually increasing abdominal distension over the past several weeks. As patient’s liver function tests were elevated, supine radiographs of the abdomen were acquired for further evaluation; a representative image is presented below (Figure 1a).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Is any additional imaging required?

Answer

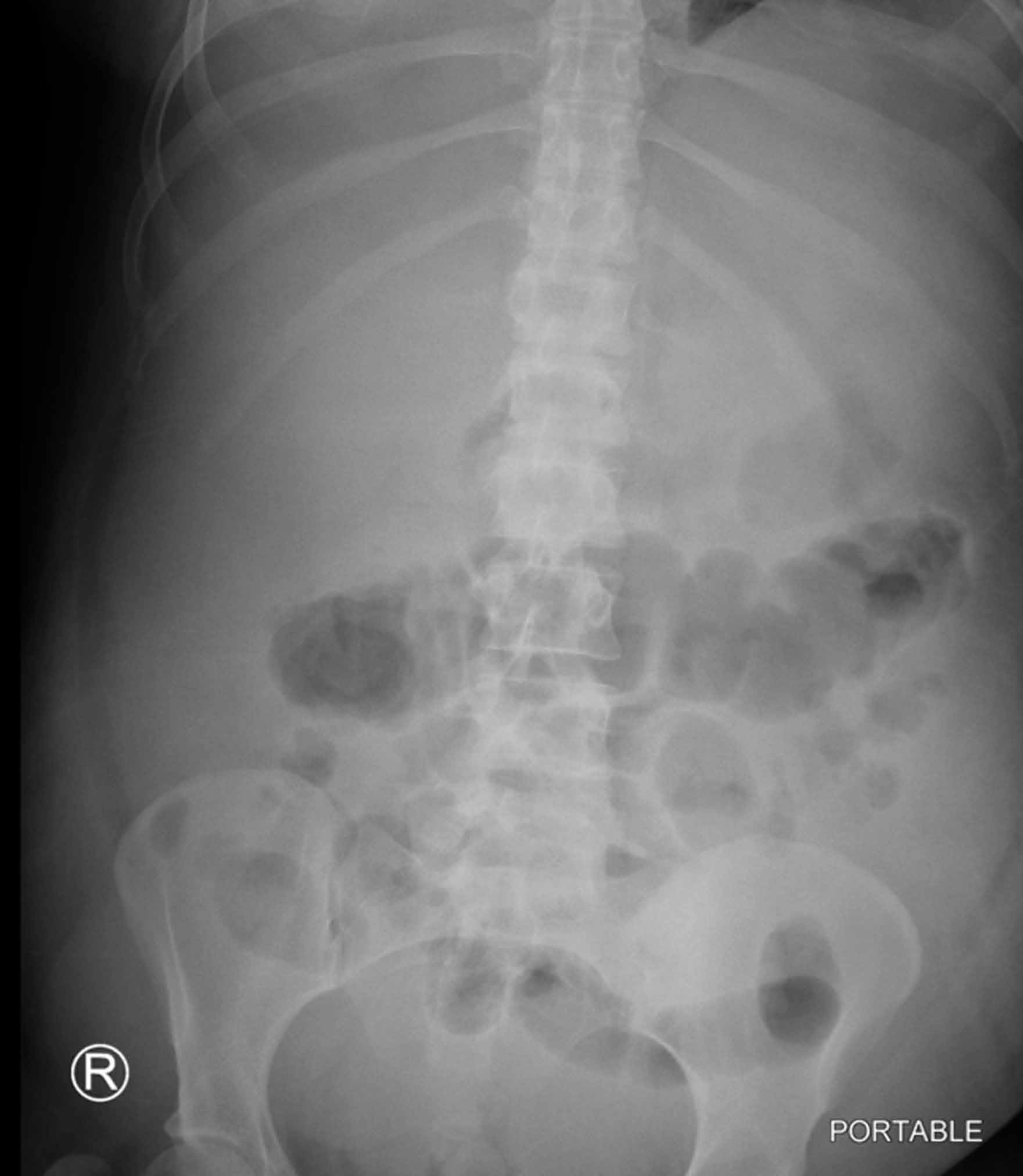

Centralization of bowel is suggestive of abdominopelvic ascites.1 Additional radiographic findings that may be seen with ascites include diffusely increased density of the abdomen and bulging of the peritoneal fat stripes/flanks. In the average adult, a minimum of approximately 800 mL of ascitic fluid is required to medially displace bowel loops or abdominal viscera.2 While there are many causes of ascites, the radiograph in this case suggests the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Although the top of the liver is not visualized on the radiograph, the liver contour appears enlarged (red arrow, Figure 1b).

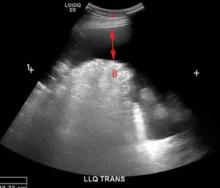

In the ED, ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice to confirm the presence of ascites as it is widely available, quick, relatively inexpensive, and does not require ionizing radiation. Ultrasound is also useful when examining the abdominal viscera since it may detect the underlying cause of ascites.3 The ultrasound image of the abdominal viscera in this case demonstrated a hypoechoic (dark) signal (red arrow, Figure 1c) between the abdominal wall (red asterisk, Figure 1c) and bowel loops (letter ‘B,” Figure 1c). This finding confirmed the presence of ascites because simple fluid does not reflect the ultrasound beam, but instead results in the hypoechoic signal seen in Figure 1c. An additional sonographic image confirmed the presence of an enlarged liver (white asterisk, Figure 1d) and ascites in the right upper quadrant (red arrow, Figure 1d).

The patient was admitted for further workup and treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis. A

Dr Lyons is a resident in the department of radiology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-

- Meschan I. Analysis of Roentgen Signs in General Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1973:1231.

- Keeffee EJ, Gagliardi RA, Pfister RC. The roentgenographic evaluation of ascites. Am J Roentgenol. 1967;101(2):388-396.

- Goldberg BB, Goodman GA, Clearfield HR. Evaluation of ascites by ultrasound. Radiology. 1970;96(1):15-22.

30-year-old woman with a history of alcoholism and anxiety presented to the ED for evaluation of abdominal distension and pain. She reported new social stressors at home and increased alcohol consumption. She also noted gradually increasing abdominal distension over the past several weeks. As patient’s liver function tests were elevated, supine radiographs of the abdomen were acquired for further evaluation; a representative image is presented below (Figure 1a).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Is any additional imaging required?

Answer

Centralization of bowel is suggestive of abdominopelvic ascites.1 Additional radiographic findings that may be seen with ascites include diffusely increased density of the abdomen and bulging of the peritoneal fat stripes/flanks. In the average adult, a minimum of approximately 800 mL of ascitic fluid is required to medially displace bowel loops or abdominal viscera.2 While there are many causes of ascites, the radiograph in this case suggests the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Although the top of the liver is not visualized on the radiograph, the liver contour appears enlarged (red arrow, Figure 1b).

In the ED, ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice to confirm the presence of ascites as it is widely available, quick, relatively inexpensive, and does not require ionizing radiation. Ultrasound is also useful when examining the abdominal viscera since it may detect the underlying cause of ascites.3 The ultrasound image of the abdominal viscera in this case demonstrated a hypoechoic (dark) signal (red arrow, Figure 1c) between the abdominal wall (red asterisk, Figure 1c) and bowel loops (letter ‘B,” Figure 1c). This finding confirmed the presence of ascites because simple fluid does not reflect the ultrasound beam, but instead results in the hypoechoic signal seen in Figure 1c. An additional sonographic image confirmed the presence of an enlarged liver (white asterisk, Figure 1d) and ascites in the right upper quadrant (red arrow, Figure 1d).

The patient was admitted for further workup and treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis. A

Dr Lyons is a resident in the department of radiology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-

30-year-old woman with a history of alcoholism and anxiety presented to the ED for evaluation of abdominal distension and pain. She reported new social stressors at home and increased alcohol consumption. She also noted gradually increasing abdominal distension over the past several weeks. As patient’s liver function tests were elevated, supine radiographs of the abdomen were acquired for further evaluation; a representative image is presented below (Figure 1a).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Is any additional imaging required?

Answer

Centralization of bowel is suggestive of abdominopelvic ascites.1 Additional radiographic findings that may be seen with ascites include diffusely increased density of the abdomen and bulging of the peritoneal fat stripes/flanks. In the average adult, a minimum of approximately 800 mL of ascitic fluid is required to medially displace bowel loops or abdominal viscera.2 While there are many causes of ascites, the radiograph in this case suggests the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Although the top of the liver is not visualized on the radiograph, the liver contour appears enlarged (red arrow, Figure 1b).

In the ED, ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice to confirm the presence of ascites as it is widely available, quick, relatively inexpensive, and does not require ionizing radiation. Ultrasound is also useful when examining the abdominal viscera since it may detect the underlying cause of ascites.3 The ultrasound image of the abdominal viscera in this case demonstrated a hypoechoic (dark) signal (red arrow, Figure 1c) between the abdominal wall (red asterisk, Figure 1c) and bowel loops (letter ‘B,” Figure 1c). This finding confirmed the presence of ascites because simple fluid does not reflect the ultrasound beam, but instead results in the hypoechoic signal seen in Figure 1c. An additional sonographic image confirmed the presence of an enlarged liver (white asterisk, Figure 1d) and ascites in the right upper quadrant (red arrow, Figure 1d).

The patient was admitted for further workup and treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis. A

Dr Lyons is a resident in the department of radiology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-

- Meschan I. Analysis of Roentgen Signs in General Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1973:1231.

- Keeffee EJ, Gagliardi RA, Pfister RC. The roentgenographic evaluation of ascites. Am J Roentgenol. 1967;101(2):388-396.

- Goldberg BB, Goodman GA, Clearfield HR. Evaluation of ascites by ultrasound. Radiology. 1970;96(1):15-22.

- Meschan I. Analysis of Roentgen Signs in General Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1973:1231.

- Keeffee EJ, Gagliardi RA, Pfister RC. The roentgenographic evaluation of ascites. Am J Roentgenol. 1967;101(2):388-396.

- Goldberg BB, Goodman GA, Clearfield HR. Evaluation of ascites by ultrasound. Radiology. 1970;96(1):15-22.

Occipital headache and unstable gait

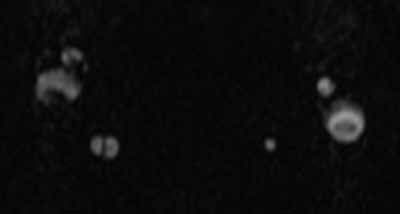

A 41-year-old-man with a history of hypertension presented to the ED with a sudden onset of severe occipital headache and unstable gait. On physical examination, right-sided ptosis and miosis (Horner’s syndrome) were noted. An emergent head computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and showed no evidence of hemorrhage or infraction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck were also ordered. Noncontrast MRA images of the neck are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

|

|

Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

What is the diagnosis?

What other imaging modalities may be useful for evaluation?

Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and the executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Answer

|

|

Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

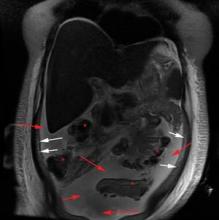

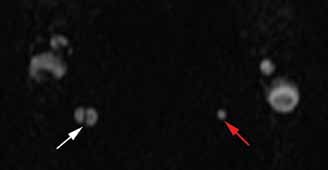

The axial MRA image demonstrates flow in two separate lumens of the right vertebral artery (white arrow, Figure 3), indicating the presence of a dissection. A normal single lumen vertebral artery can be seen on the left (red arrow, Figure 3). This dissection is confirmed on the coronal MRA image (white arrows, Figure 4).

Vertebral artery dissection (VAD) is a common cause of stroke and, less commonly, of transient ischemic attack in patients aged 18 to 45 years. Patients typically present with headache, vertigo, dizziness, and neck pain.1 Additional neurologic signs that may be related to compromise of the posterior cerebral circulation include lateral medullary syndrome (eg, dysphagia, slurred speech, ataxia, facial pain, nystagmus, diplopia, dysphonia) and Horner’s syndrome (eg, ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis). In a small percentage of patients, VAD may present as intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage.1

VAD can occur spontaneously or following high-energy trauma or minor trauma (eg, resulting from coughing, vomiting, cervical spine manipulation, or sports injury). Approximately 15% of patients have an underlying connective tissue disorder, such as fibromuscular dysplasia.2

The diagnosis of VAD can be made with MRI/MRA or with computed tomography angiography (CTA). A recent review of the literature shows no clear advantage to using either modality; therefore, the choice CTA or MRA should be based on urgency, availability of the imaging modality, and the preferences/expertise of the radiologists.3

|

|

Figure 5 | Figure 6 |

Advantages of CTA include its widespread availability, short examination time, and ability to evaluate for concurrent injuries in a trauma patient. With respect to MRA, in addition the lack of ionizing radiation, images may be performed without intravenous contrast and completed at the same time as MRI, which is useful in detecting alternative or concurrent intracranial abnormalities such as stroke, mass, or demyelination.

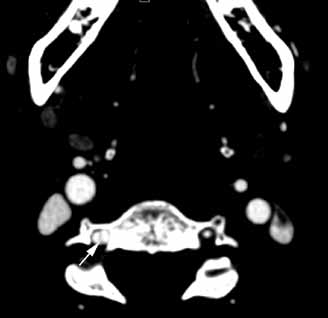

In this case, axial and coronal images from follow-up CTA illustrate its ability to depict the dissection of the right vertebral artery (white arrows, Figures 5 and 6). Typical treatment for VAD includes anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, though there have also been reports of successful treatment with endovascular stenting and endovascular thrombolysis.4 Since timely and proper treatment decreases the risk of stroke and long-term disabilities, emergent imaging with CTA or MRA should be performed in cases of suspected VAD.

- Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, et al. Clinical characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: a systematic review. Neurologist. 2012;18(5):245-254.

- Rodallec MH, Marteau V, Gerber S, Desmottes L, Zins M. Craniocervical arterial dissection: spectrum of imaging findings and differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2008;28(6):1711-1728.

- Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characteristics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(4):1167-1174.

- Menon R, Kerry S, Norris JW, Markus HS. Treatment of cervical artery dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(10):1122-1127.

A 41-year-old-man with a history of hypertension presented to the ED with a sudden onset of severe occipital headache and unstable gait. On physical examination, right-sided ptosis and miosis (Horner’s syndrome) were noted. An emergent head computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and showed no evidence of hemorrhage or infraction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck were also ordered. Noncontrast MRA images of the neck are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

|

|

Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

What is the diagnosis?

What other imaging modalities may be useful for evaluation?

Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and the executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Answer

|

|

Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

The axial MRA image demonstrates flow in two separate lumens of the right vertebral artery (white arrow, Figure 3), indicating the presence of a dissection. A normal single lumen vertebral artery can be seen on the left (red arrow, Figure 3). This dissection is confirmed on the coronal MRA image (white arrows, Figure 4).

Vertebral artery dissection (VAD) is a common cause of stroke and, less commonly, of transient ischemic attack in patients aged 18 to 45 years. Patients typically present with headache, vertigo, dizziness, and neck pain.1 Additional neurologic signs that may be related to compromise of the posterior cerebral circulation include lateral medullary syndrome (eg, dysphagia, slurred speech, ataxia, facial pain, nystagmus, diplopia, dysphonia) and Horner’s syndrome (eg, ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis). In a small percentage of patients, VAD may present as intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage.1

VAD can occur spontaneously or following high-energy trauma or minor trauma (eg, resulting from coughing, vomiting, cervical spine manipulation, or sports injury). Approximately 15% of patients have an underlying connective tissue disorder, such as fibromuscular dysplasia.2

The diagnosis of VAD can be made with MRI/MRA or with computed tomography angiography (CTA). A recent review of the literature shows no clear advantage to using either modality; therefore, the choice CTA or MRA should be based on urgency, availability of the imaging modality, and the preferences/expertise of the radiologists.3

|

|

Figure 5 | Figure 6 |

Advantages of CTA include its widespread availability, short examination time, and ability to evaluate for concurrent injuries in a trauma patient. With respect to MRA, in addition the lack of ionizing radiation, images may be performed without intravenous contrast and completed at the same time as MRI, which is useful in detecting alternative or concurrent intracranial abnormalities such as stroke, mass, or demyelination.

In this case, axial and coronal images from follow-up CTA illustrate its ability to depict the dissection of the right vertebral artery (white arrows, Figures 5 and 6). Typical treatment for VAD includes anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, though there have also been reports of successful treatment with endovascular stenting and endovascular thrombolysis.4 Since timely and proper treatment decreases the risk of stroke and long-term disabilities, emergent imaging with CTA or MRA should be performed in cases of suspected VAD.

A 41-year-old-man with a history of hypertension presented to the ED with a sudden onset of severe occipital headache and unstable gait. On physical examination, right-sided ptosis and miosis (Horner’s syndrome) were noted. An emergent head computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and showed no evidence of hemorrhage or infraction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck were also ordered. Noncontrast MRA images of the neck are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

|

|

Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

What is the diagnosis?

What other imaging modalities may be useful for evaluation?

Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and the executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Answer

|

|

Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

The axial MRA image demonstrates flow in two separate lumens of the right vertebral artery (white arrow, Figure 3), indicating the presence of a dissection. A normal single lumen vertebral artery can be seen on the left (red arrow, Figure 3). This dissection is confirmed on the coronal MRA image (white arrows, Figure 4).

Vertebral artery dissection (VAD) is a common cause of stroke and, less commonly, of transient ischemic attack in patients aged 18 to 45 years. Patients typically present with headache, vertigo, dizziness, and neck pain.1 Additional neurologic signs that may be related to compromise of the posterior cerebral circulation include lateral medullary syndrome (eg, dysphagia, slurred speech, ataxia, facial pain, nystagmus, diplopia, dysphonia) and Horner’s syndrome (eg, ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis). In a small percentage of patients, VAD may present as intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage.1

VAD can occur spontaneously or following high-energy trauma or minor trauma (eg, resulting from coughing, vomiting, cervical spine manipulation, or sports injury). Approximately 15% of patients have an underlying connective tissue disorder, such as fibromuscular dysplasia.2

The diagnosis of VAD can be made with MRI/MRA or with computed tomography angiography (CTA). A recent review of the literature shows no clear advantage to using either modality; therefore, the choice CTA or MRA should be based on urgency, availability of the imaging modality, and the preferences/expertise of the radiologists.3

|

|

Figure 5 | Figure 6 |

Advantages of CTA include its widespread availability, short examination time, and ability to evaluate for concurrent injuries in a trauma patient. With respect to MRA, in addition the lack of ionizing radiation, images may be performed without intravenous contrast and completed at the same time as MRI, which is useful in detecting alternative or concurrent intracranial abnormalities such as stroke, mass, or demyelination.

In this case, axial and coronal images from follow-up CTA illustrate its ability to depict the dissection of the right vertebral artery (white arrows, Figures 5 and 6). Typical treatment for VAD includes anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, though there have also been reports of successful treatment with endovascular stenting and endovascular thrombolysis.4 Since timely and proper treatment decreases the risk of stroke and long-term disabilities, emergent imaging with CTA or MRA should be performed in cases of suspected VAD.

- Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, et al. Clinical characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: a systematic review. Neurologist. 2012;18(5):245-254.

- Rodallec MH, Marteau V, Gerber S, Desmottes L, Zins M. Craniocervical arterial dissection: spectrum of imaging findings and differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2008;28(6):1711-1728.

- Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characteristics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(4):1167-1174.

- Menon R, Kerry S, Norris JW, Markus HS. Treatment of cervical artery dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(10):1122-1127.

- Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, et al. Clinical characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: a systematic review. Neurologist. 2012;18(5):245-254.

- Rodallec MH, Marteau V, Gerber S, Desmottes L, Zins M. Craniocervical arterial dissection: spectrum of imaging findings and differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2008;28(6):1711-1728.

- Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characteristics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(4):1167-1174.

- Menon R, Kerry S, Norris JW, Markus HS. Treatment of cervical artery dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(10):1122-1127.