User login

Risk of Intestinal Necrosis With Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) was first approved in the United States in 1958 and is a commonly prescribed medication for hyperkalemia.1 SPS works by exchanging potassium for sodium in the colonic lumen, thereby promoting potassium loss in the stool. However, reports of severe gastrointestinal side effects, particularly intestinal necrosis, have been persistent since the 1970s,2 leading some authors to recommend against the use of SPS.3,4 In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned against concomitant sorbitol administration, which was implicated in some studies.4,5 The concern about gastrointestinal side effects has also led to the development and FDA approval of two new cation-exchange resins for treatment of hyperkalemia.6 A prior systematic review of the literature found 30 separate case reports or case series including a total of 58 patients who were treated with SPS and developed severe gastrointestinal side effects.7 Because the included studies were all case reports or case series and therefore did not include comparison groups, it could not be determined whether SPS had a causal role in gastrointestinal side effects, and the authors could only conclude that there was a “possible” association. In contrast to case reports, several large cohort studies have been published more recently and report the risk of severe gastrointestinal adverse events associated with SPS compared with controls.8-10 While some studies found an increased risk, others have not. Given this uncertainty, we undertook a systematic review of studies that report the incidence of severe gastrointestinal side effects with SPS compared with controls.

METHODS

Data Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted by a medical librarian using the Cochrane Library, Embase, Medline, Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection databases to find relevant articles published from database inception to October 4, 2020. The search was peer reviewed by a second medical librarian using Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS).11 Databases were searched using a combination of controlled vocabulary and free-text terms for “SPS” and “bowel necrosis.” Details of the full search strategy are listed in Appendix A. References from all databases were imported into an EndNote X9 library, duplicates removed, and then uploaded into Coviden

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We used a standardized form to extract data, which included author, year, country, study design, setting, number of patients, SPS formulation, dosing, exposure, sorbitol content, outcomes of intestinal necrosis and the composite severe gastrointestinal adverse events, and the duration of time from SPS exposure to outcome occurrence. Two reviewers (JLH and AER) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for observational studies13 and the Revised Cochrane risk of bias (RoB 2) tool for randomized controlled trials (RCTs).14 Additionally, two reviewers (JLH and CGG) graded overall strength of evidence based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.15 Disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The proportion of patients with intestinal necrosis was compared using random effects meta-analysis using the restricted maximum likelihood method.16 For the two studies that reported hazard ratios (HRs), meta-analysis was performed after log transformation of the HRs and CIs. One study that performed survival analysis presented data for both the duration of the study (up to 11 years) and up to 1 year after exposure.9 We used the data up to 1 year after exposure because we believed later events were more likely to be due to chance than exposure to SPS. For studies with zero events, we used the treat ment-arm continuity correction, which has been reported to be preferable to the standard fixed-correction factor.17 We also performed two sensitivity analyses, including omitting the studies with zero events and performing meta-analysis using risk difference. The prevalence of intestinal ischemia was pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird18 random effects model with Freeman-Tukey19 double arcsine transformation. Heterogeneity was estimated using the I² statistic. I² values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.20 Meta-regression and tests for small-study effects were not performed because of the small number of included studies.21 In addition to random effects meta-analysis, we calculated the 90% predicted interval for future studies for the pooled effect of intestinal ischemia.22 Statistical analysis was performed using meta and metaprop commands in Stata/IC, version 16.1 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

Selected Studies

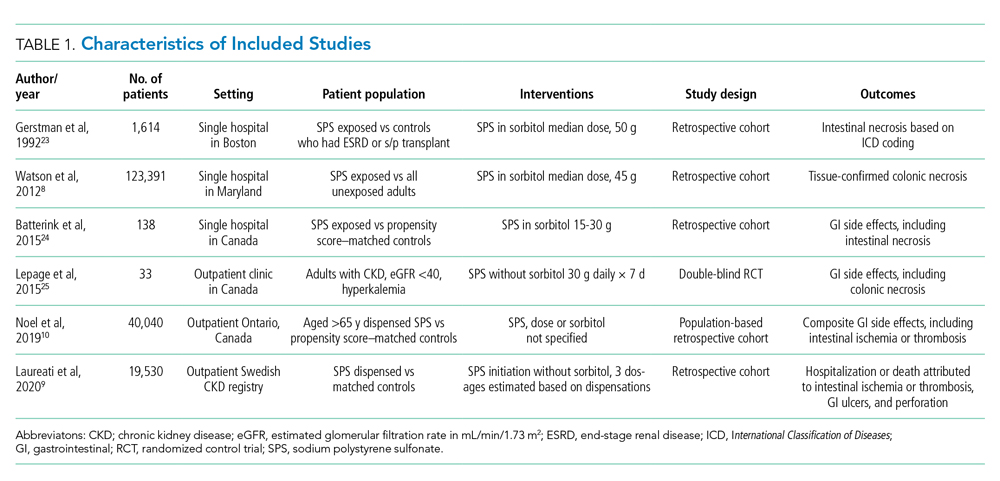

The electronic search yielded 806 unique articles, of which 791 were excluded based on title and abstract, leaving 15 articles for full-text review (Appendix B). Appendix C describes the nine studies that were excluded, including the reason for exclusion. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the six studies that met study inclusion criteria. Studies were published between 1992 and 2020. Three studies were from Canada,10,24,25 two from the United States,8,23 and one from Sweden.9 Three studies occurred in an outpatient setting,9,10,25 and three were described as inpatient studies.8,23,24 SPS preparations included sorbitol in three studies,8,23,24 were not specified in one study,10 and were not included in two studies.9,25 SPS dosing varied widely, with median doses of 15 to 30 g in three studies,9,24,25 45 to 50 g in two studies,8,23 and unspecified in one study.10 Duration of exposure typically ranged from 1 to 7 days but was not consistently described. For example, two of the studies did not report duration of exposure,8,10 and a third study reported a single dispensation of 450 g in 41% of patients, with the remaining 59% averaging three dispensations within the first year.9 Sample size ranged from 33 to 123,391 patients. Most patients were male, and mean ages ranged from 44 to 78 years. Two studies limited participation to those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <4024 or CKD stage 4 or 5 or dialysis.9 Two studies specifically limited participation to patients with potassium levels of 5.0 to 5.9 mmol/L.24,25 All six studies reported outcomes for intestinal necrosis, and four reported composite outcomes for major adverse gastrointestinal events.9,10,24,25

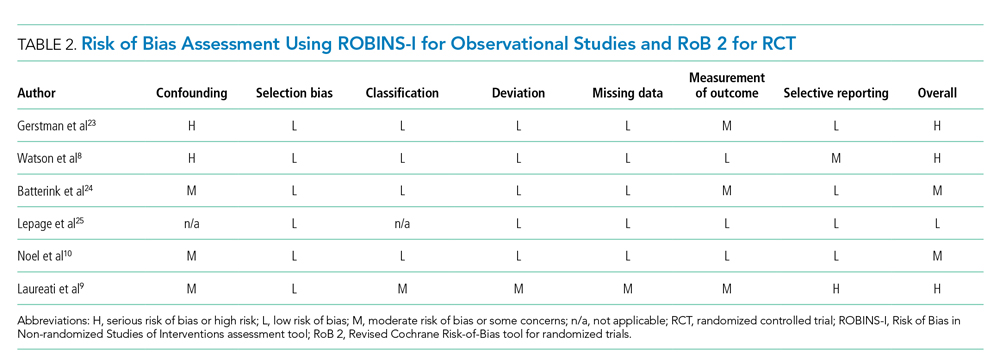

Table 2 describes the assessment of risk of bias using the ROBINS-I tool for the five retrospective observational studies and the RoB 2 tool for the one RCT.13,14 Three studies were rated as having serious risk of bias, with the remainder having a moderate risk of bias or some concerns. Two studies were judged as having a serious risk of bias because of potential confounding.8,23 To be judged low or moderate risk, studies needed to measure and control for potential risk factors for intestinal ischemia, such as age, diabetes, vascular disease, and heart failure.26,27 One study also had serious risk of bias for selective reporting because the published abstract of the study used a different analysis and had contradictory results from the published study.9,28 An additional area of risk of bias that did not fit into the ROBINS-I tool is that the two studies that used survival analysis chose durations for the outcome that were longer than would be expected for adverse events from SPS to be evident. One study chose 30 days and the other up to a maximum of 11 years from the time of exposure.9,10

Quantitative Outcomes

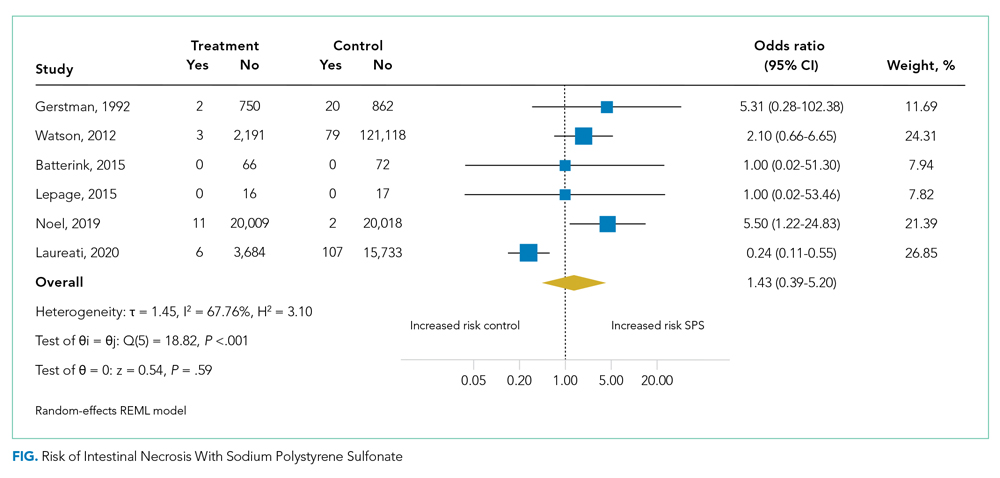

Six studies including 26,716 patients treated with SPS and controls reported the proportion of patients who developed intestinal necrosis. The Figure shows the individual study and pooled results for intestinal necrosis. The prevalence of intestinal ischemia in patients treated with SPS was 0.1% (95% CI, 0.03%-0.17%). The pooled odds ratio (OR) of intestinal necrosis was 1.43 (95% CI, 0.39-5.20). The 90% predicted interval for future studies was 0.08 to 26.6. Two studies reported rates of intestinal necrosis using survival analysis. The pooled HR from these studies was 2.00 (95% CI, 0.45-8.78). Two studies performed survival analysis for a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal adverse events. The pooled HR for these two studies was 1.46 (95% CI, 1.01-2.11).

For the meta-analysis of intestinal necrosis, we found moderate-high statistical significance (Q = 18.82; P < .01; I² = 67.8%). Sensitivity analysis removing each study did not affect heterogeneity, with the exception of removing the study by Laureati et al,9 which resolved the heterogeneity (Q = 1.7, P = .8, I² = 0%). The pooled effect for intestinal necrosis also became statistically significant after removing Laureati et al (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.24-6.63).9 We also performed two subgroup analyses, including studies that involved the concomitant use of sorbitol8,23,24 compared with studies that did not9,25 and subgroup analysis removing studies with zero events. Studies that included sorbitol found higher rates of intestinal necrosis (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 0.80-6.38; I² = 0%) compared with studies that did not include sorbitol (OR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.57; I² = 0%; test of group difference, P < .01). Removing the three studies with zero events resulted in a similar overall effect (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.21-8.19). Finally, a meta-analysis using risk difference instead of ORs found a non–statistically significant difference in rate of intestinal necrosis favoring the control group (risk difference, −0.00033; 95% CI, −0.0022 to 0.0015; I² = 84.6%).

Table 3 summarizes our review findings and presents overall strength of evidence. Overall strength of evidence was found to be very low. Per GRADE criteria,15,29 strength of evidence for observational studies starts at low and may then be modified by the presence of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, effect size, and direction of confounding. In the case of the three meta-analyses in the present study, risk of bias was serious for more than half of the study weights. Strength of evidence was also downrated for imprecision because of the low number of events and resultant wide CIs.

DISCUSSION

In total, we found six studies that reported rates of intestinal necrosis or severe gastrointestinal adverse events with SPS use compared with controls. The pooled rate of intestinal necrosis was not significantly higher for patients exposed to SPS when analyzed either as the proportion of patients with events or as HRs. The pooled rate for a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal side effects was significantly higher (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.01-2.11). The overall strength of evidence for the association of SPS with either intestinal necrosis or the composite outcome was found to be very low because of risk of bias and imprecision.

In some ways, our results emphasize the difficulty of showing a causal link between a medication and a possible rare adverse event. The first included study to assess the risk of intestinal necrosis after exposure to SPS compared with controls found only two events in the SPS group and no events in the control arm.23 Two additional studies that we found were small and did not report any events in either arm.24,25 The first large study to assess the risk of intestinal ischemia included more than 2,000 patients treated with SPS and more than 100,000 controls but found no difference in risk.8 The next large study did find increased risk of both intestinal necrosis (incidence rate, 6.82 per 1,000 person-years compared with 1.22 per 1,000 person-years for controls) and a composite outcome (incidence rate, 22.97 per 1,000 person-years compared with 11.01 per 1000 person-years for controls), but in the time to event analysis included events up to 30 days after treatment with SPS.10 A prior review of case reports of SPS and intestinal necrosis found a median of 2 days between SPS treatment and symptom onset.7 It is unlikely the authors would have had sufficient events to meaningfully compare rates if they limited the analysis to events within 7 days of SPS treatment, but events after a week of exposure are unlikely to be due to SPS. The final study to assess the association of SPS with intestinal necrosis actually found higher rates of intestinal necrosis in the control group when analyzed as proportions with events but reported a higher rate of a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal adverse events that included nine separate International Classification of Diseases codes occurring up to 11 years after SPS exposure.9 This study was limited by evidence of selective reporting and was funded by the manufacturers of an alternative cation-exchange medication.

Based on our review of the literature, it is unclear if SPS does cause intestinal ischemia. The pooled results for intestinal ischemia analyzed as a proportion with events or with survival analysis did not find a statistically significantly increased risk. Because most o

A cost analysis of SPS vs potential alternatives such as patiromer for patients on chronic RAAS-I with a history of hyperkalemia or CKD published by Little et al26 concluded that SPS remained the cost-effective option when colonic necrosis incidence is 19.9% or less, and our systematic review reveals an incidence of 0.1% (95% CI, 0.03-0.17%). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was an astronomical $26,088,369 per quality-adjusted life-year gained, per Little’s analysis.

Limitations of our review are the heterogeneity of studies, which varied regarding inpatient or outpatient setting, formulations such as dosing, frequency, whether sorbitol was used, and interval from exposure to outcome measurement, which ranged from 7 days to 1 year. On sensitivity analysis, statistical heterogeneity was resolved by removing the study by Laureati et al.9 This study was notably different from the others because it included events occurring up to 1 year after exposure to SPS, which may have resulted in any true effect being diluted by later events unrelated to SPS. We did not exclude this study post hoc because this would result in bias; however, because the overall result becomes statistically significant without this study, our overall conclusion should be interpreted with caution.30 It is possible that future well-conducted studies may still find an effect of SPS on intestinal necrosis. Similarly, the finding that studies with SPS coformulated with sorbitol had statistically significantly increased risk of intestinal necrosis compared with studies without sorbitol should be interpreted with caution because the study by Laureati et al9 was included in the studies without sorbitol.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on our r

This work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine and Society of Hospital Medicine 2021 annual conferences.

1. Labriola L, Jadoul M. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate: still news after 60 years on the market. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(9):1455-1458. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa004

2. Arvanitakis C, Malek G, Uehling D, Morrissey JF. Colonic complications after renal transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1973;64(4):533-538.

3. Parks M, Grady D. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate for hyperkalemia. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1023-1024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1291

4. Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-exchange resins for the treatment of hyperkalemia: are they safe and effective? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(5):733-735. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010010079

5. Lillemoe KD, Romolo JL, Hamilton SR, Pennington LR, Burdick JF, Williams GM. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) in sorbitol enemas: clinical and experimental support for the hypothesis. Surgery. 1987;101(3):267-272.

6. Sterns RH, Grieff M, Bernstein PL. Treatment of hyperkalemia: something old, something new. Kidney Int. 2016;89(3):546-554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.018

7. Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, Wald R, Perl J, Bell CM. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):264.e269-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.08.016

8. Watson MA, Baker TP, Nguyen A, et al. Association of prescription of oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate with sorbitol in an inpatient setting with colonic necrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):409-416. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.023

9. Laureati P, Xu Y, Trevisan M, et al. Initiation of sodium polystyrene sulphonate and the risk of gastrointestinal adverse events in advanced chronic kidney disease: a nationwide study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(9):1518-1526. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz150

10. Noel JA, Bota SE, Petrcich W, et al. Risk of hospitalization for serious adverse gastrointestinal events associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate use in patients of advanced age. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1025-1033. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0631

11. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65-94. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136

13. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

14. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

15. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383-394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

16. Raudenbush SW. Analyzing effect sizes: random-effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. 2nd ed. Russel Sage Foundation; 2009:295-316.

17. Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med. 2004;23(9):1351-1375. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1761

18. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

19. Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Statist. 1950;21(4):607-611. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729756

20. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

21. Higgins JPT, Chandler TJ, Cumptson M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

22. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. Jan 2009;172(1):137-159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x

23. Gerstman BB, Kirkman R, Platt R. Intestinal necrosis associated with postoperative orally administered sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20(2):159-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80544-0

24. Batterink J, Lin J, Au-Yeung SHM, Cessford T. Effectiveness of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for short-term treatment of hyperkalemia. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(4):296-303. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i4.1469

25. Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for the treatment of mild hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2136-2142. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03640415

26. Little DJ, Nee R, Abbott KC, Watson MA, Yuan CM. Cost-utility analysis of sodium polystyrene sulfonate vs. potential alternatives for chronic hyperkalemia. Clin Nephrol. 2014;81(4):259-268. https://doi.org/10.5414/cn108103

27. Cubiella Fernández J, Núñez Calvo L, González Vázquez E, et al. Risk factors associated with the development of ischemic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(36):4564-4569. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4564

28. Laureati P, Evans M, Trevisan M, et al. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate, practice patterns and associated adverse event risk; a nationwide analysis from the Swedish Renal Register [abstract]. Nephroly Dial Transplant. 2019;34(suppl 1):i94. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz106.FP151

29. Santesso N, Carrasco-Labra A, Langendam M, et al. Improving GRADE evidence tables part 3: detailed guidance for explanatory footnotes supports creating and understanding GRADE certainty in the evidence judgments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:28-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.006

30. Deeks JJ HJ, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane, 2020. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) was first approved in the United States in 1958 and is a commonly prescribed medication for hyperkalemia.1 SPS works by exchanging potassium for sodium in the colonic lumen, thereby promoting potassium loss in the stool. However, reports of severe gastrointestinal side effects, particularly intestinal necrosis, have been persistent since the 1970s,2 leading some authors to recommend against the use of SPS.3,4 In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned against concomitant sorbitol administration, which was implicated in some studies.4,5 The concern about gastrointestinal side effects has also led to the development and FDA approval of two new cation-exchange resins for treatment of hyperkalemia.6 A prior systematic review of the literature found 30 separate case reports or case series including a total of 58 patients who were treated with SPS and developed severe gastrointestinal side effects.7 Because the included studies were all case reports or case series and therefore did not include comparison groups, it could not be determined whether SPS had a causal role in gastrointestinal side effects, and the authors could only conclude that there was a “possible” association. In contrast to case reports, several large cohort studies have been published more recently and report the risk of severe gastrointestinal adverse events associated with SPS compared with controls.8-10 While some studies found an increased risk, others have not. Given this uncertainty, we undertook a systematic review of studies that report the incidence of severe gastrointestinal side effects with SPS compared with controls.

METHODS

Data Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted by a medical librarian using the Cochrane Library, Embase, Medline, Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection databases to find relevant articles published from database inception to October 4, 2020. The search was peer reviewed by a second medical librarian using Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS).11 Databases were searched using a combination of controlled vocabulary and free-text terms for “SPS” and “bowel necrosis.” Details of the full search strategy are listed in Appendix A. References from all databases were imported into an EndNote X9 library, duplicates removed, and then uploaded into Coviden

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We used a standardized form to extract data, which included author, year, country, study design, setting, number of patients, SPS formulation, dosing, exposure, sorbitol content, outcomes of intestinal necrosis and the composite severe gastrointestinal adverse events, and the duration of time from SPS exposure to outcome occurrence. Two reviewers (JLH and AER) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for observational studies13 and the Revised Cochrane risk of bias (RoB 2) tool for randomized controlled trials (RCTs).14 Additionally, two reviewers (JLH and CGG) graded overall strength of evidence based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.15 Disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The proportion of patients with intestinal necrosis was compared using random effects meta-analysis using the restricted maximum likelihood method.16 For the two studies that reported hazard ratios (HRs), meta-analysis was performed after log transformation of the HRs and CIs. One study that performed survival analysis presented data for both the duration of the study (up to 11 years) and up to 1 year after exposure.9 We used the data up to 1 year after exposure because we believed later events were more likely to be due to chance than exposure to SPS. For studies with zero events, we used the treat ment-arm continuity correction, which has been reported to be preferable to the standard fixed-correction factor.17 We also performed two sensitivity analyses, including omitting the studies with zero events and performing meta-analysis using risk difference. The prevalence of intestinal ischemia was pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird18 random effects model with Freeman-Tukey19 double arcsine transformation. Heterogeneity was estimated using the I² statistic. I² values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.20 Meta-regression and tests for small-study effects were not performed because of the small number of included studies.21 In addition to random effects meta-analysis, we calculated the 90% predicted interval for future studies for the pooled effect of intestinal ischemia.22 Statistical analysis was performed using meta and metaprop commands in Stata/IC, version 16.1 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

Selected Studies

The electronic search yielded 806 unique articles, of which 791 were excluded based on title and abstract, leaving 15 articles for full-text review (Appendix B). Appendix C describes the nine studies that were excluded, including the reason for exclusion. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the six studies that met study inclusion criteria. Studies were published between 1992 and 2020. Three studies were from Canada,10,24,25 two from the United States,8,23 and one from Sweden.9 Three studies occurred in an outpatient setting,9,10,25 and three were described as inpatient studies.8,23,24 SPS preparations included sorbitol in three studies,8,23,24 were not specified in one study,10 and were not included in two studies.9,25 SPS dosing varied widely, with median doses of 15 to 30 g in three studies,9,24,25 45 to 50 g in two studies,8,23 and unspecified in one study.10 Duration of exposure typically ranged from 1 to 7 days but was not consistently described. For example, two of the studies did not report duration of exposure,8,10 and a third study reported a single dispensation of 450 g in 41% of patients, with the remaining 59% averaging three dispensations within the first year.9 Sample size ranged from 33 to 123,391 patients. Most patients were male, and mean ages ranged from 44 to 78 years. Two studies limited participation to those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <4024 or CKD stage 4 or 5 or dialysis.9 Two studies specifically limited participation to patients with potassium levels of 5.0 to 5.9 mmol/L.24,25 All six studies reported outcomes for intestinal necrosis, and four reported composite outcomes for major adverse gastrointestinal events.9,10,24,25

Table 2 describes the assessment of risk of bias using the ROBINS-I tool for the five retrospective observational studies and the RoB 2 tool for the one RCT.13,14 Three studies were rated as having serious risk of bias, with the remainder having a moderate risk of bias or some concerns. Two studies were judged as having a serious risk of bias because of potential confounding.8,23 To be judged low or moderate risk, studies needed to measure and control for potential risk factors for intestinal ischemia, such as age, diabetes, vascular disease, and heart failure.26,27 One study also had serious risk of bias for selective reporting because the published abstract of the study used a different analysis and had contradictory results from the published study.9,28 An additional area of risk of bias that did not fit into the ROBINS-I tool is that the two studies that used survival analysis chose durations for the outcome that were longer than would be expected for adverse events from SPS to be evident. One study chose 30 days and the other up to a maximum of 11 years from the time of exposure.9,10

Quantitative Outcomes

Six studies including 26,716 patients treated with SPS and controls reported the proportion of patients who developed intestinal necrosis. The Figure shows the individual study and pooled results for intestinal necrosis. The prevalence of intestinal ischemia in patients treated with SPS was 0.1% (95% CI, 0.03%-0.17%). The pooled odds ratio (OR) of intestinal necrosis was 1.43 (95% CI, 0.39-5.20). The 90% predicted interval for future studies was 0.08 to 26.6. Two studies reported rates of intestinal necrosis using survival analysis. The pooled HR from these studies was 2.00 (95% CI, 0.45-8.78). Two studies performed survival analysis for a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal adverse events. The pooled HR for these two studies was 1.46 (95% CI, 1.01-2.11).

For the meta-analysis of intestinal necrosis, we found moderate-high statistical significance (Q = 18.82; P < .01; I² = 67.8%). Sensitivity analysis removing each study did not affect heterogeneity, with the exception of removing the study by Laureati et al,9 which resolved the heterogeneity (Q = 1.7, P = .8, I² = 0%). The pooled effect for intestinal necrosis also became statistically significant after removing Laureati et al (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.24-6.63).9 We also performed two subgroup analyses, including studies that involved the concomitant use of sorbitol8,23,24 compared with studies that did not9,25 and subgroup analysis removing studies with zero events. Studies that included sorbitol found higher rates of intestinal necrosis (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 0.80-6.38; I² = 0%) compared with studies that did not include sorbitol (OR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.57; I² = 0%; test of group difference, P < .01). Removing the three studies with zero events resulted in a similar overall effect (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.21-8.19). Finally, a meta-analysis using risk difference instead of ORs found a non–statistically significant difference in rate of intestinal necrosis favoring the control group (risk difference, −0.00033; 95% CI, −0.0022 to 0.0015; I² = 84.6%).

Table 3 summarizes our review findings and presents overall strength of evidence. Overall strength of evidence was found to be very low. Per GRADE criteria,15,29 strength of evidence for observational studies starts at low and may then be modified by the presence of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, effect size, and direction of confounding. In the case of the three meta-analyses in the present study, risk of bias was serious for more than half of the study weights. Strength of evidence was also downrated for imprecision because of the low number of events and resultant wide CIs.

DISCUSSION

In total, we found six studies that reported rates of intestinal necrosis or severe gastrointestinal adverse events with SPS use compared with controls. The pooled rate of intestinal necrosis was not significantly higher for patients exposed to SPS when analyzed either as the proportion of patients with events or as HRs. The pooled rate for a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal side effects was significantly higher (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.01-2.11). The overall strength of evidence for the association of SPS with either intestinal necrosis or the composite outcome was found to be very low because of risk of bias and imprecision.

In some ways, our results emphasize the difficulty of showing a causal link between a medication and a possible rare adverse event. The first included study to assess the risk of intestinal necrosis after exposure to SPS compared with controls found only two events in the SPS group and no events in the control arm.23 Two additional studies that we found were small and did not report any events in either arm.24,25 The first large study to assess the risk of intestinal ischemia included more than 2,000 patients treated with SPS and more than 100,000 controls but found no difference in risk.8 The next large study did find increased risk of both intestinal necrosis (incidence rate, 6.82 per 1,000 person-years compared with 1.22 per 1,000 person-years for controls) and a composite outcome (incidence rate, 22.97 per 1,000 person-years compared with 11.01 per 1000 person-years for controls), but in the time to event analysis included events up to 30 days after treatment with SPS.10 A prior review of case reports of SPS and intestinal necrosis found a median of 2 days between SPS treatment and symptom onset.7 It is unlikely the authors would have had sufficient events to meaningfully compare rates if they limited the analysis to events within 7 days of SPS treatment, but events after a week of exposure are unlikely to be due to SPS. The final study to assess the association of SPS with intestinal necrosis actually found higher rates of intestinal necrosis in the control group when analyzed as proportions with events but reported a higher rate of a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal adverse events that included nine separate International Classification of Diseases codes occurring up to 11 years after SPS exposure.9 This study was limited by evidence of selective reporting and was funded by the manufacturers of an alternative cation-exchange medication.

Based on our review of the literature, it is unclear if SPS does cause intestinal ischemia. The pooled results for intestinal ischemia analyzed as a proportion with events or with survival analysis did not find a statistically significantly increased risk. Because most o

A cost analysis of SPS vs potential alternatives such as patiromer for patients on chronic RAAS-I with a history of hyperkalemia or CKD published by Little et al26 concluded that SPS remained the cost-effective option when colonic necrosis incidence is 19.9% or less, and our systematic review reveals an incidence of 0.1% (95% CI, 0.03-0.17%). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was an astronomical $26,088,369 per quality-adjusted life-year gained, per Little’s analysis.

Limitations of our review are the heterogeneity of studies, which varied regarding inpatient or outpatient setting, formulations such as dosing, frequency, whether sorbitol was used, and interval from exposure to outcome measurement, which ranged from 7 days to 1 year. On sensitivity analysis, statistical heterogeneity was resolved by removing the study by Laureati et al.9 This study was notably different from the others because it included events occurring up to 1 year after exposure to SPS, which may have resulted in any true effect being diluted by later events unrelated to SPS. We did not exclude this study post hoc because this would result in bias; however, because the overall result becomes statistically significant without this study, our overall conclusion should be interpreted with caution.30 It is possible that future well-conducted studies may still find an effect of SPS on intestinal necrosis. Similarly, the finding that studies with SPS coformulated with sorbitol had statistically significantly increased risk of intestinal necrosis compared with studies without sorbitol should be interpreted with caution because the study by Laureati et al9 was included in the studies without sorbitol.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on our r

This work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine and Society of Hospital Medicine 2021 annual conferences.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) was first approved in the United States in 1958 and is a commonly prescribed medication for hyperkalemia.1 SPS works by exchanging potassium for sodium in the colonic lumen, thereby promoting potassium loss in the stool. However, reports of severe gastrointestinal side effects, particularly intestinal necrosis, have been persistent since the 1970s,2 leading some authors to recommend against the use of SPS.3,4 In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned against concomitant sorbitol administration, which was implicated in some studies.4,5 The concern about gastrointestinal side effects has also led to the development and FDA approval of two new cation-exchange resins for treatment of hyperkalemia.6 A prior systematic review of the literature found 30 separate case reports or case series including a total of 58 patients who were treated with SPS and developed severe gastrointestinal side effects.7 Because the included studies were all case reports or case series and therefore did not include comparison groups, it could not be determined whether SPS had a causal role in gastrointestinal side effects, and the authors could only conclude that there was a “possible” association. In contrast to case reports, several large cohort studies have been published more recently and report the risk of severe gastrointestinal adverse events associated with SPS compared with controls.8-10 While some studies found an increased risk, others have not. Given this uncertainty, we undertook a systematic review of studies that report the incidence of severe gastrointestinal side effects with SPS compared with controls.

METHODS

Data Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted by a medical librarian using the Cochrane Library, Embase, Medline, Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection databases to find relevant articles published from database inception to October 4, 2020. The search was peer reviewed by a second medical librarian using Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS).11 Databases were searched using a combination of controlled vocabulary and free-text terms for “SPS” and “bowel necrosis.” Details of the full search strategy are listed in Appendix A. References from all databases were imported into an EndNote X9 library, duplicates removed, and then uploaded into Coviden

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We used a standardized form to extract data, which included author, year, country, study design, setting, number of patients, SPS formulation, dosing, exposure, sorbitol content, outcomes of intestinal necrosis and the composite severe gastrointestinal adverse events, and the duration of time from SPS exposure to outcome occurrence. Two reviewers (JLH and AER) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for observational studies13 and the Revised Cochrane risk of bias (RoB 2) tool for randomized controlled trials (RCTs).14 Additionally, two reviewers (JLH and CGG) graded overall strength of evidence based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.15 Disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The proportion of patients with intestinal necrosis was compared using random effects meta-analysis using the restricted maximum likelihood method.16 For the two studies that reported hazard ratios (HRs), meta-analysis was performed after log transformation of the HRs and CIs. One study that performed survival analysis presented data for both the duration of the study (up to 11 years) and up to 1 year after exposure.9 We used the data up to 1 year after exposure because we believed later events were more likely to be due to chance than exposure to SPS. For studies with zero events, we used the treat ment-arm continuity correction, which has been reported to be preferable to the standard fixed-correction factor.17 We also performed two sensitivity analyses, including omitting the studies with zero events and performing meta-analysis using risk difference. The prevalence of intestinal ischemia was pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird18 random effects model with Freeman-Tukey19 double arcsine transformation. Heterogeneity was estimated using the I² statistic. I² values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.20 Meta-regression and tests for small-study effects were not performed because of the small number of included studies.21 In addition to random effects meta-analysis, we calculated the 90% predicted interval for future studies for the pooled effect of intestinal ischemia.22 Statistical analysis was performed using meta and metaprop commands in Stata/IC, version 16.1 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

Selected Studies

The electronic search yielded 806 unique articles, of which 791 were excluded based on title and abstract, leaving 15 articles for full-text review (Appendix B). Appendix C describes the nine studies that were excluded, including the reason for exclusion. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the six studies that met study inclusion criteria. Studies were published between 1992 and 2020. Three studies were from Canada,10,24,25 two from the United States,8,23 and one from Sweden.9 Three studies occurred in an outpatient setting,9,10,25 and three were described as inpatient studies.8,23,24 SPS preparations included sorbitol in three studies,8,23,24 were not specified in one study,10 and were not included in two studies.9,25 SPS dosing varied widely, with median doses of 15 to 30 g in three studies,9,24,25 45 to 50 g in two studies,8,23 and unspecified in one study.10 Duration of exposure typically ranged from 1 to 7 days but was not consistently described. For example, two of the studies did not report duration of exposure,8,10 and a third study reported a single dispensation of 450 g in 41% of patients, with the remaining 59% averaging three dispensations within the first year.9 Sample size ranged from 33 to 123,391 patients. Most patients were male, and mean ages ranged from 44 to 78 years. Two studies limited participation to those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <4024 or CKD stage 4 or 5 or dialysis.9 Two studies specifically limited participation to patients with potassium levels of 5.0 to 5.9 mmol/L.24,25 All six studies reported outcomes for intestinal necrosis, and four reported composite outcomes for major adverse gastrointestinal events.9,10,24,25

Table 2 describes the assessment of risk of bias using the ROBINS-I tool for the five retrospective observational studies and the RoB 2 tool for the one RCT.13,14 Three studies were rated as having serious risk of bias, with the remainder having a moderate risk of bias or some concerns. Two studies were judged as having a serious risk of bias because of potential confounding.8,23 To be judged low or moderate risk, studies needed to measure and control for potential risk factors for intestinal ischemia, such as age, diabetes, vascular disease, and heart failure.26,27 One study also had serious risk of bias for selective reporting because the published abstract of the study used a different analysis and had contradictory results from the published study.9,28 An additional area of risk of bias that did not fit into the ROBINS-I tool is that the two studies that used survival analysis chose durations for the outcome that were longer than would be expected for adverse events from SPS to be evident. One study chose 30 days and the other up to a maximum of 11 years from the time of exposure.9,10

Quantitative Outcomes

Six studies including 26,716 patients treated with SPS and controls reported the proportion of patients who developed intestinal necrosis. The Figure shows the individual study and pooled results for intestinal necrosis. The prevalence of intestinal ischemia in patients treated with SPS was 0.1% (95% CI, 0.03%-0.17%). The pooled odds ratio (OR) of intestinal necrosis was 1.43 (95% CI, 0.39-5.20). The 90% predicted interval for future studies was 0.08 to 26.6. Two studies reported rates of intestinal necrosis using survival analysis. The pooled HR from these studies was 2.00 (95% CI, 0.45-8.78). Two studies performed survival analysis for a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal adverse events. The pooled HR for these two studies was 1.46 (95% CI, 1.01-2.11).

For the meta-analysis of intestinal necrosis, we found moderate-high statistical significance (Q = 18.82; P < .01; I² = 67.8%). Sensitivity analysis removing each study did not affect heterogeneity, with the exception of removing the study by Laureati et al,9 which resolved the heterogeneity (Q = 1.7, P = .8, I² = 0%). The pooled effect for intestinal necrosis also became statistically significant after removing Laureati et al (OR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.24-6.63).9 We also performed two subgroup analyses, including studies that involved the concomitant use of sorbitol8,23,24 compared with studies that did not9,25 and subgroup analysis removing studies with zero events. Studies that included sorbitol found higher rates of intestinal necrosis (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 0.80-6.38; I² = 0%) compared with studies that did not include sorbitol (OR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.57; I² = 0%; test of group difference, P < .01). Removing the three studies with zero events resulted in a similar overall effect (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.21-8.19). Finally, a meta-analysis using risk difference instead of ORs found a non–statistically significant difference in rate of intestinal necrosis favoring the control group (risk difference, −0.00033; 95% CI, −0.0022 to 0.0015; I² = 84.6%).

Table 3 summarizes our review findings and presents overall strength of evidence. Overall strength of evidence was found to be very low. Per GRADE criteria,15,29 strength of evidence for observational studies starts at low and may then be modified by the presence of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, effect size, and direction of confounding. In the case of the three meta-analyses in the present study, risk of bias was serious for more than half of the study weights. Strength of evidence was also downrated for imprecision because of the low number of events and resultant wide CIs.

DISCUSSION

In total, we found six studies that reported rates of intestinal necrosis or severe gastrointestinal adverse events with SPS use compared with controls. The pooled rate of intestinal necrosis was not significantly higher for patients exposed to SPS when analyzed either as the proportion of patients with events or as HRs. The pooled rate for a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal side effects was significantly higher (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.01-2.11). The overall strength of evidence for the association of SPS with either intestinal necrosis or the composite outcome was found to be very low because of risk of bias and imprecision.

In some ways, our results emphasize the difficulty of showing a causal link between a medication and a possible rare adverse event. The first included study to assess the risk of intestinal necrosis after exposure to SPS compared with controls found only two events in the SPS group and no events in the control arm.23 Two additional studies that we found were small and did not report any events in either arm.24,25 The first large study to assess the risk of intestinal ischemia included more than 2,000 patients treated with SPS and more than 100,000 controls but found no difference in risk.8 The next large study did find increased risk of both intestinal necrosis (incidence rate, 6.82 per 1,000 person-years compared with 1.22 per 1,000 person-years for controls) and a composite outcome (incidence rate, 22.97 per 1,000 person-years compared with 11.01 per 1000 person-years for controls), but in the time to event analysis included events up to 30 days after treatment with SPS.10 A prior review of case reports of SPS and intestinal necrosis found a median of 2 days between SPS treatment and symptom onset.7 It is unlikely the authors would have had sufficient events to meaningfully compare rates if they limited the analysis to events within 7 days of SPS treatment, but events after a week of exposure are unlikely to be due to SPS. The final study to assess the association of SPS with intestinal necrosis actually found higher rates of intestinal necrosis in the control group when analyzed as proportions with events but reported a higher rate of a composite outcome of severe gastrointestinal adverse events that included nine separate International Classification of Diseases codes occurring up to 11 years after SPS exposure.9 This study was limited by evidence of selective reporting and was funded by the manufacturers of an alternative cation-exchange medication.

Based on our review of the literature, it is unclear if SPS does cause intestinal ischemia. The pooled results for intestinal ischemia analyzed as a proportion with events or with survival analysis did not find a statistically significantly increased risk. Because most o

A cost analysis of SPS vs potential alternatives such as patiromer for patients on chronic RAAS-I with a history of hyperkalemia or CKD published by Little et al26 concluded that SPS remained the cost-effective option when colonic necrosis incidence is 19.9% or less, and our systematic review reveals an incidence of 0.1% (95% CI, 0.03-0.17%). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was an astronomical $26,088,369 per quality-adjusted life-year gained, per Little’s analysis.

Limitations of our review are the heterogeneity of studies, which varied regarding inpatient or outpatient setting, formulations such as dosing, frequency, whether sorbitol was used, and interval from exposure to outcome measurement, which ranged from 7 days to 1 year. On sensitivity analysis, statistical heterogeneity was resolved by removing the study by Laureati et al.9 This study was notably different from the others because it included events occurring up to 1 year after exposure to SPS, which may have resulted in any true effect being diluted by later events unrelated to SPS. We did not exclude this study post hoc because this would result in bias; however, because the overall result becomes statistically significant without this study, our overall conclusion should be interpreted with caution.30 It is possible that future well-conducted studies may still find an effect of SPS on intestinal necrosis. Similarly, the finding that studies with SPS coformulated with sorbitol had statistically significantly increased risk of intestinal necrosis compared with studies without sorbitol should be interpreted with caution because the study by Laureati et al9 was included in the studies without sorbitol.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on our r

This work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine and Society of Hospital Medicine 2021 annual conferences.

1. Labriola L, Jadoul M. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate: still news after 60 years on the market. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(9):1455-1458. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa004

2. Arvanitakis C, Malek G, Uehling D, Morrissey JF. Colonic complications after renal transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1973;64(4):533-538.

3. Parks M, Grady D. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate for hyperkalemia. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1023-1024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1291

4. Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-exchange resins for the treatment of hyperkalemia: are they safe and effective? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(5):733-735. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010010079

5. Lillemoe KD, Romolo JL, Hamilton SR, Pennington LR, Burdick JF, Williams GM. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) in sorbitol enemas: clinical and experimental support for the hypothesis. Surgery. 1987;101(3):267-272.

6. Sterns RH, Grieff M, Bernstein PL. Treatment of hyperkalemia: something old, something new. Kidney Int. 2016;89(3):546-554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.018

7. Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, Wald R, Perl J, Bell CM. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):264.e269-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.08.016

8. Watson MA, Baker TP, Nguyen A, et al. Association of prescription of oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate with sorbitol in an inpatient setting with colonic necrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):409-416. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.023

9. Laureati P, Xu Y, Trevisan M, et al. Initiation of sodium polystyrene sulphonate and the risk of gastrointestinal adverse events in advanced chronic kidney disease: a nationwide study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(9):1518-1526. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz150

10. Noel JA, Bota SE, Petrcich W, et al. Risk of hospitalization for serious adverse gastrointestinal events associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate use in patients of advanced age. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1025-1033. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0631

11. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65-94. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136

13. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

14. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

15. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383-394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

16. Raudenbush SW. Analyzing effect sizes: random-effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. 2nd ed. Russel Sage Foundation; 2009:295-316.

17. Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med. 2004;23(9):1351-1375. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1761

18. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

19. Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Statist. 1950;21(4):607-611. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729756

20. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

21. Higgins JPT, Chandler TJ, Cumptson M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

22. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. Jan 2009;172(1):137-159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x

23. Gerstman BB, Kirkman R, Platt R. Intestinal necrosis associated with postoperative orally administered sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20(2):159-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80544-0

24. Batterink J, Lin J, Au-Yeung SHM, Cessford T. Effectiveness of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for short-term treatment of hyperkalemia. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(4):296-303. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i4.1469

25. Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for the treatment of mild hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2136-2142. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03640415

26. Little DJ, Nee R, Abbott KC, Watson MA, Yuan CM. Cost-utility analysis of sodium polystyrene sulfonate vs. potential alternatives for chronic hyperkalemia. Clin Nephrol. 2014;81(4):259-268. https://doi.org/10.5414/cn108103

27. Cubiella Fernández J, Núñez Calvo L, González Vázquez E, et al. Risk factors associated with the development of ischemic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(36):4564-4569. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4564

28. Laureati P, Evans M, Trevisan M, et al. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate, practice patterns and associated adverse event risk; a nationwide analysis from the Swedish Renal Register [abstract]. Nephroly Dial Transplant. 2019;34(suppl 1):i94. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz106.FP151

29. Santesso N, Carrasco-Labra A, Langendam M, et al. Improving GRADE evidence tables part 3: detailed guidance for explanatory footnotes supports creating and understanding GRADE certainty in the evidence judgments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:28-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.006

30. Deeks JJ HJ, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane, 2020. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

1. Labriola L, Jadoul M. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate: still news after 60 years on the market. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(9):1455-1458. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa004

2. Arvanitakis C, Malek G, Uehling D, Morrissey JF. Colonic complications after renal transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1973;64(4):533-538.

3. Parks M, Grady D. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate for hyperkalemia. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1023-1024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1291

4. Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-exchange resins for the treatment of hyperkalemia: are they safe and effective? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(5):733-735. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010010079

5. Lillemoe KD, Romolo JL, Hamilton SR, Pennington LR, Burdick JF, Williams GM. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) in sorbitol enemas: clinical and experimental support for the hypothesis. Surgery. 1987;101(3):267-272.

6. Sterns RH, Grieff M, Bernstein PL. Treatment of hyperkalemia: something old, something new. Kidney Int. 2016;89(3):546-554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.018

7. Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, Wald R, Perl J, Bell CM. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):264.e269-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.08.016

8. Watson MA, Baker TP, Nguyen A, et al. Association of prescription of oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate with sorbitol in an inpatient setting with colonic necrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):409-416. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.023

9. Laureati P, Xu Y, Trevisan M, et al. Initiation of sodium polystyrene sulphonate and the risk of gastrointestinal adverse events in advanced chronic kidney disease: a nationwide study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(9):1518-1526. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz150

10. Noel JA, Bota SE, Petrcich W, et al. Risk of hospitalization for serious adverse gastrointestinal events associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate use in patients of advanced age. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1025-1033. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0631

11. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65-94. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136

13. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

14. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

15. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383-394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

16. Raudenbush SW. Analyzing effect sizes: random-effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. 2nd ed. Russel Sage Foundation; 2009:295-316.

17. Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med. 2004;23(9):1351-1375. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1761

18. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

19. Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Statist. 1950;21(4):607-611. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729756

20. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

21. Higgins JPT, Chandler TJ, Cumptson M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

22. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. Jan 2009;172(1):137-159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x

23. Gerstman BB, Kirkman R, Platt R. Intestinal necrosis associated with postoperative orally administered sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20(2):159-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80544-0

24. Batterink J, Lin J, Au-Yeung SHM, Cessford T. Effectiveness of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for short-term treatment of hyperkalemia. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(4):296-303. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i4.1469

25. Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for the treatment of mild hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2136-2142. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03640415

26. Little DJ, Nee R, Abbott KC, Watson MA, Yuan CM. Cost-utility analysis of sodium polystyrene sulfonate vs. potential alternatives for chronic hyperkalemia. Clin Nephrol. 2014;81(4):259-268. https://doi.org/10.5414/cn108103

27. Cubiella Fernández J, Núñez Calvo L, González Vázquez E, et al. Risk factors associated with the development of ischemic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(36):4564-4569. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4564

28. Laureati P, Evans M, Trevisan M, et al. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate, practice patterns and associated adverse event risk; a nationwide analysis from the Swedish Renal Register [abstract]. Nephroly Dial Transplant. 2019;34(suppl 1):i94. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz106.FP151

29. Santesso N, Carrasco-Labra A, Langendam M, et al. Improving GRADE evidence tables part 3: detailed guidance for explanatory footnotes supports creating and understanding GRADE certainty in the evidence judgments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:28-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.006

30. Deeks JJ HJ, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane, 2020. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Things We Do for No Reason: Intermittent Pneumatic Compression for Medical Ward Patients?

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation's Choosing Wisely campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 74-year-old man with a history of diabetes and gastrointestinal bleeding two months prior, presents with nausea/vomiting and diarrhea after eating unrefrigerated leftovers. Body mass index is 25. Labs are unremarkable except for a blood urea nitrogen of 37 mg/dL, serum creatinine of 1.6 mg/dL up from 1.3, and white blood cell count of 12 K/µL. He is afebrile with blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg. He lives alone and is fully ambulatory at baseline. The Emergency Department physician requests observation admission for “dehydration/gastroenteritis.” The admitting hospitalist orders intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis.

BACKGROUND

The American Public Health Association has called VTE prophylaxis a “public health crisis” due to the gap between existing evidence and implementation.1 The incidence of symptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in hospitalized medical patients managed without prophylaxis is 0.96% and 1.2%, respectively,2 whereas that of asymptomatic DVT in hospitalized patients is approximately 1.8%.2,3 IPC is widely used, and an international registry of 15,156 hospitalized acutely ill medical patients found that 22% of United States patients received IPC for VTE prophylaxis compared with 0.2% of patients in other countries.4

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK IPC IS THE BEST OPTION FOR VTE PROPHYLAXIS IN MEDICAL WARD PATIENTS

The main reason clinicians opt to use IPC for VTE prophylaxis is the wish to avoid the bleeding risk associated with heparin. The American College of Chest Physicians antithrombotic guideline 9th edition (ACCP-AT9) recommends mechanical prophylaxis for patients at increased risk for thrombosis who are either bleeding or at “high risk for major bleeding.”5 The guideline considered patients to have an excessive bleeding risk if they had an active gastroduodenal ulcer, bleeding within the past three months, a platelet count below 50,000/ml, or more than one of the following risk factors: age ≥ 85, hepatic failure with INR >1.5, severe renal failure with GFR <30 mL/min/m2, ICU/CCU admission, central venous catheter, rheumatic disease, current cancer, or male gender.5 IPC also avoids the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, which is a rare but potentially devastating condition.

WHY IPC MIGHT NOT BE AS HELPFUL IN MEDICAL WARD PATIENTS

IPC devices are frequently not worn or turned on. A study at two university-affiliated level one trauma centers found IPC to be functioning properly in only 19% of trauma patients.10 In another study of gynecologic oncology patients, 52% of IPCs were functioning improperly and 25% of patients experienced some discomfort, inconvenience, or problems with external pneumatic compression.11 Redness, itching, or discomfort was cited by 26% of patients, and patients removed IPCs 11% of the time when nurses left the room.11,12 In another study, skin breakdown occurred in 3% of IPC patients as compared with 1% in the control group.7

Concerns about a possible link between IPC and increased fall risk was raised by a 2005 report of 40 falls by the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System,13 and IPC accounted for 16 of 3,562 hospital falls according to Boelig and colleagues.14 Ritsema et al. found that the most important perceived barriers to IPC compliance according to patient surveys were that the devices “prevented walking or getting up” (47%), “were tethering or tangling” (25%), and “woke the patient from sleep” (15%).15

IPC devices are not created equally, differing in “anatomical location of the sleeve garment, number and location of air bladders, patterns for compression cycles and duration of inflation time and deflation time.”16 Comparative effectiveness may differ. A study comparing a rapid inflation asymmetrical compression device by Venaflow with a sequential circumferential compression device by Kendall in a high-risk post knee replacement population produced DVT rates of 6.9% versus 15%, respectively (P = .007).16,17 Furthermore, the type of sleeve and device may affect comfort and compliance as some sleeves are considered “breathable.”

Perhaps most importantly, data supporting IPC efficacy in general medical ward patients are virtually nonexistent. Ho’s meta-analysis of IPC after excluding surgical patients found a relative risk (RR) of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.35-0.81, P < .01) for DVT in nine trials and a nonstatistically significant RR of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.29-1.42. P = .27) for PE in six trials.6 However, if high-risk populations such as trauma, critical care, and stroke are excluded, then

IPC is expensive. The cost for pneumatic compression boots is quoted in the literature at $120 with a range of $80-$250.21 Furthermore, patients averaged 2.5 pairs per hospitalization.22 An online search of retail prices revealed a pair of knee-length Covidien 5329 compression sleeves at $299.19 per pair23 and knee-length Kendall 7325-2 compression sleeves at $433.76 per pair24 with pumps costing $7,518.07 for Venodyne 610 Advantage,25 $6,965.98 for VenaFlow Elite,26 and $5,750.50 for Covidien 29525 700 series Kendall SCD.27 However, using these prices would be overestimating costs given that hospitals do not pay retail prices. A prior surgical cost/benefit analysis used a prevalence of 6.9% and a 69% reduction of DVT.28 However, recent data showed that VTE incidence in 31,219 medical patients was only 0.57% and RR for a large VTE prevention initiative was a nonsignificant 10% reduction.29 Even if we use a VTE prevalence of 1% for the general medical floor and 0.5% RR reduction, 200 patients would need to be treated to prevent one symptomatic VTE and would cost about $24,000 for IPC sleeves alone (estimating $120 per patient) without factoring in additional costs of pump purchase or rental and six additional episodes of anticipated skin breakdown. In comparison, the cost for VTE treatment ranges from $7,712 to $16,644.30

WHAT SHOULD WE DO INSTEAD?

First, one should consider if VTE prophylaxis is needed based on risk assessment. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the most widely used risk stratification model is the University of California San Diego “3 bucket model” (Table 1) derived from tables in ACCP-AT8 guidelines.31

RECOMMENDATIONS

- The VTE risk of general medicine ward patients should be assessed, preferably with the “3 bucket” or Padua risk assessment models.

- For low-risk patients, no VTE prophylaxis is indicated. Ambulation ought to be encouraged for low-risk patients.

- If prophylaxis is indicated, then bleeding risk should be assessed to determine a contraindication to pharmacologic prophylaxis. If there is excessive bleeding risk, then treatment with IPC may be considered even though there are only data to support this in high-risk populations such as surgical, stroke, trauma, and critical care patients.

- If using IPC, then strategies that ensure compliance and consider patient comfort based on type and location of sleeves should be implemented.

- Combined IPC and pharmacologic prophylaxis should be used for high-risk trauma or surgical patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailingTWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Association APH. Deep-vein thrombosis: advancing awareness to protect patient lives. WHITE Paper. Public Health Leadership Conference on Deep-Vein Thrombosis.

2. Lederle FA, Zylla D, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients and those with stroke: a background review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):602-615. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00008. PubMed

3. Zubrow MT, Urie J, Jurkovitz C, et al. Asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing screening duplex ultrasonography. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):19-22. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2112. PubMed

4. Tapson VF, Decousus H, Pini M, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: findings from the International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism. Chest. 2007;132(3):936-945. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2993. PubMed

5. Guyatt GH, Eikelboom JW, Gould MK, et al. Approach to outcome measurement in the prevention of thrombosis in surgical and medical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e185S-e194S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2289. PubMed

6. Ho KM, Tan JA. Stratified meta-analysis of intermittent pneumatic compression of the lower limbs to prevent venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Circulation. 2013;128(9):1003-1020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002690. PubMed

7. CLOTS (Clots in Legs Or sTockings after Stroke) Trials Collaboration, Dennis M, Sandercock P, et al. Effectiveness of intermittent pneumatic compression in reduction of risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients who have had a stroke (CLOTS 3): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9891):516-524. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61050-8. PubMed

8. Park J, Lee JM, Lee JS, Cho YJ. Pharmacological and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients: a network meta-analysis of 12 trials. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(11):1828-1837. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1828. PubMed

9. Kakkos SK, Caprini JA, Geroulakos G, et al. Combined intermittent pneumatic leg compression and pharmacological prophylaxis for prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD005258:CD005258. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005258.pub3. PubMed

10. Cornwell EE, 3rd, Chang D, Velmahos G, et al. Compliance with sequential compression device prophylaxis in at-risk trauma patients: a prospective analysis. Am Surg. 2002;68(5):470-473. PubMed

11. Maxwell GL, Synan I, Hayes RP, Clarke-Pearson DL. Preference and compliance in postoperative thromboembolism prophylaxis among gynecologic oncology patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(3):451-455. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02162-2. PubMed

12. Wood KB, Kos PB, Abnet JK, Ista C. Prevention of deep-vein thrombosis after major spinal surgery: a comparison study of external devices. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10(3):209-214. PubMed

13. Unexpected risk from a beneficial device: sequential compression devices and patient falls. PA-PSRS Patient Saf Advis. 2005 Sep;2(3):13-5.

14. Boelig MM, Streiff MB, Hobson DB, Kraus PS, Pronovost PJ, Haut ER. Are sequential compression devices commonly associated with in-hospital falls? A myth-busters review using the patient safety net database. J Patient Saf. 2011;7(2):77-79. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182110706. PubMed

15. Ritsema DF, Watson JM, Stiteler AP, Nguyen MM. Sequential compression devices in postoperative urologic patients: an observational trial and survey study on the influence of patient and hospital factors on compliance. BMC Urol. 2013;13:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-13-20. PubMed

16. Pavon JM, Williams JW, Jr, Adam SS, et al. Effectiveness of intermittent pneumatic compression devices for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in high-risk surgical and medical patients. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(2):524-532. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.043. PubMed

17. Lachiewicz PF, Kelley SS, Haden LR. Two mechanical devices for prophylaxis of thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty. A prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(8):1137-1141. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B8.15438. PubMed

18. Salzman EW, Sobel M, Lewis J, Sweeney J, Hussey S, Kurland G. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in unstable angina pectoris. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(16):991. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204223061614. PubMed

19. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, Gutterman DD, Schuünemann HJ, American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):7S-47S. doi: 10.1378/chest.1412S3. PubMed

20. Qaseem A, Chou R, Humphrey LL, Starkey M, Shekelle P, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):625-632. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00011. PubMed

21. Casele H, Grobman WA. Cost-effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression at cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 1):535-540. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000227780.76353.05. PubMed