User login

AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Center Program--Applying the Knowledge to Practice to Data Cycle to Strengthen the Value of Patient Care

Research evidence is critical for strengthening the value, quality, and safety of patient care. Learning healthcare systems (LHS) can support the delivery of evidence-based healthcare by establishing organizational processes that support three activities (Figure).1-3

- Knowledge: Identifying and synthesizing evidence to address clinical challenges

- Practice: Applying knowledge in the process of care delivery

- Data: Assessing performance and creating a feedback cycle for learning and improvement

The systematic implementation of evidence into practice continues to be a challenge for many healthcare organizations4-7 due to limited resources, expertise, and culture.5,8-12 Missing opportunities for translating knowledge into practice not only results in low-value care (ie, waste) but also in harm.1

The AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Program was established in 1997, with the goal of synthesizing research to inform evidence-based healthcare. The national impact of this program has been significant. Since the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, EPC program reports have been used to inform over 95 clinical practice guidelines from societies such as the American College of Physicians, 16 health coverage decisions from payers such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and 24 government policies and program planning efforts, such as the National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Program.13

The EPC program recognizes that evidence awareness is not sufficient to change practice and improve clinical outcomes. As such, the EPC program also embarked on initiatives to facilitate the translation of evidence into clinical practice and to measure and monitor how changes in practice impact health outcomes. AHRQ has historically worked with professional organizations to translate systematic reviews into clinical practice guidelines as well as federal agencies to inform payer decisions and program planning. Recently, the EPC program has increased collaborative efforts with hospitals and healthcare systems to understand how they use evidence and to partner with them to identify methods to improve the uptake of evidence into practice.9,12

In this perspective, we describe the AHRQ EPC Program’s work to address the three phases of the LHS cycle (knowledge, practice, and data) to support high-value care, using the topic of preventing and treating Clostridium difficile colitis as a relevant example to the hospital medicine field (Figure 2). By sharing this work, we hope it can serve as a model to illustrate how partnerships between organizations and AHRQ can lead to improvements in healthcare.

USING THE LEARNING HEALTHCARE SYSTEM CYCLE TO STRUCTURE AHRQ EPC WORK

Knowledge: Identifying and Synthesizing Evidence to Address Clinical Challenges

Systematic reviews use carefully formulated questions to summarize the literature results using specific and established methods.14 Given that individual studies can have disparate results, it is critical to summarize and synthesize findings across studies, so we know what the overall evidence suggests, and whether we can be confident in the findings. To date, the EPC program has developed more than 500 evidence synthesis reports. An example relevant to the field of hospital medicine is the 2016 review that examined the effects of interventions to prevent and treat Clostridium difficile colitis in adults.15

The review examined the best available evidence, including data from randomized controlled trials and observational studies, on diagnosing, preventing, and treating Clostridium difficile colitis. Major findings included the following: vancomycin is more effective than metronidazole for treating the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis (high-strength evidence), fecal transplantation may have a significant benefit in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis (low-strength evidence), and institutional preventive interventions such as antibiotic stewardship practices, transmission interruption through terminal room cleaning, and handwashing campaigns reduce the incidence of Clostridium difficile colitis (low-strength evidence). The report results provided the most recent review of the evidence and were particularly important as they suggested a need for significant practice changes in the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis based on the new evidence available. Previous to this report, the 2010 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommended metronidazole over vancomycin for the treatment of the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis.16 Subsequently, the newly released 2018 IDSA guideline provides recommendations consistent with the findings in this AHRQ report.17

Practice: Applying Knowledge in the Process of Care Delivery

AHRQ recognizes there are many interim steps between having the results from a systematic review and changing practice and improving care. In 2017, the EPC program began piloting approaches to make it easier for healthcare systems and hospitals to use its reports to improve the delivery of patient care and clinical outcomes. A pilot project conducted by the ECRI Institute - Penn Medicine EPC evaluated the feasibility of using an existing clinical pathway development and dissemination framework18 to translate findings from the 2016 AHRQ EPC report on Clostridium difficile colitis into a pathway for Clostridium difficile colitis treatment in the acute care setting.

To develop a Clostridium difficile colitis treatment pathway, the ECRI-Penn EPC team recruited a representative stakeholder group from Penn Medicine to review the EPC report as well as existing society guidelines. The clinical pathway was subsequently developed and approved by the stakeholders and disseminated through the Penn Medicine cloud-based pathways repository beginning on April 16, 2018.19 Most recently, the pathway became available in the electronic health record (EHR; 2018 Epic Systems Corporation) to facilitate provider review during care. Specifically, hyperlinks to the pathway are embedded within the ordering screens for those antibiotics used to treat Clostridium difficile colitis (ie, oral and rectal vancomycin, fidaxomicin, and metronidazole). Upon clicking the link in the ordering screen, the pathway launches a floating internet explorer window. The pathway is now publicly available on the AHRQ’s Clinical Decision Support (CDS) Connect Project (https://cds.ahrq.gov/), which is a resource to share pathway artifacts for other healthcare systems to use.

Data: Assessing Performance and Creating a Feedback Cycle for Learning and Improvement

The last step in the LHS cycle is to identify the impact of interventions on practice change and clinical outcomes, to understand how local results compare to peer institutions, and to inform future research and knowledge.

For the ECRI Institute-Penn Medicine EPC pilot project, both qualitative and quantitative outcomes were assessed. The initial qualitative analysis focused on the feasibility of using the AHRQ report in an existing pathway development and dissemination framework.18 It was found that clinical stakeholders identified the EPC report as trustworthy and more current than the society guidelines available at the time of development, particularly regarding the finding that vancomycin was more effective than metronidazole for the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis. Additional qualitative analysis will be conducted to understand provider satisfaction with the pathway and practice impact. The quantitative analysis focused on pathway use (clicks over time) and found that as of September 16, 2018, the pathway had been viewed by providers 403 times. Future analysis will evaluate the impact of the pathway on the use of oral vancomycin for the first occurrences of Clostridium difficile colitis.

Patient registries can also help clinicians and healthcare systems to complete the feedback cycle and evaluate outcomes. Patient registries collect data from clinical and other sources in a standardized way in order to evaluate specific outcomes for various populations.20 AHRQ has created a registry handbook, including best practices for how to create, operate, and evaluate registries.20 This handbook enables the development of high-quality registries with data that can be leveraged for both research and improvement.

In the example of the ECRI Institute-Penn Medicine EPC pilot project, one way that a learning healthcare system, such as Penn Medicine, might measure the impact of the clinical pathway is to develop a quality improvement registry, which might be developed with information from their electronic health record, to examine the impact on the use of vancomycin for first occurrences of Clostridium difficile colitis. This information could help drive improvement in the implementation of the clinical pathway.

Registries can also be used as a source for research data. The NIH-funded American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry is an example of a research registry that collects data on outcomes and adverse events associated with fecal transplants to fill gaps in existing research. The 2016 AHRQ EPC review found low-strength evidence on fecal transplant for treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis. When designing the protocol for this registry, the researchers used the AHRQ handbook to inform the design. Given that this is a research registry, it can be used by researchers to examine trends and outcomes of fecal transplant to treat Clostridium difficile colitis. Publications that use the registry as its source of data may be used in future systematic reviews, thus completing the cycle of learning.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

The EPC program recognizes that gaps remain in the evidence to practice translation process and that more support is needed. Some upcoming activities of the AHRQ EPC Program to address these gaps and make its evidence reports more actionable for healthcare systems include:

- Projects to Disseminate EPC Reports into Clinical Practice. In addition to the ECRI Institute - Penn Medicine EPC pilot dissemination project, other pilot projects are aimed at helping systems apply evidence to practice and include new ways to visualize evidence to make it more actionable and usable; creating other dissemination products, such as evidence summaries and presentations for decision makers; and other implementation tools, such as decision aids. These products and summary reports are available on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Program website at https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/health-systems-use-evidence/overview.

- Healthcare Systems Stakeholder Panel. Starting in Fall 2018, the AHRQ EPC Program will be convening a panel of healthcare system leaders to help make its reports and products more useful and responsive to the needs of healthcare systems and promote the use of evidence in clinical practice.

- Rapid Evidence Products. AHRQ understands that healthcare systems need information rapidly and cannot wait a year or more for a traditional systematic review to be completed. Therefore, AHRQ is applying its methods work on rapid reviews21-24 to pilot new report types that systematically identify and summarize the evidence quickly for healthcare systems and quality improvement efforts.25

- Data Integration. Originally launched in 2012, the Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR) is an AHRQ-supported online open-access repository of abstracted data from individual studies from systematic reviews. The goal is to enable more efficient updates of systematic reviews through data reuse. An updated version of the SRDR is scheduled to launch in 2020. With the new version, future sharing of summary data from systematic reviews digitally in a computable and portable format may allow integration into CDS tools and clinical practice guideline development and dissemination, facilitating the use of evidence in clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The AHRQ EPC program supports initiatives to make evidence more actionable and provide resources and tools throughout all the phases of the learning healthcare system cycle. This case study on C. difficile is one example of how the EPC program is helping hospitals and healthcare systems improve clinical care delivery and its derivative value.

Disclosures

Dr. Umscheid reports grants from AHRQ, during the conduct of the study; serves on the Advisory Board of DynaMed, and founded and directed a hospital-based evidence-based practice center. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s), who are responsible for its content, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in A, Institute of M. In: Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM, eds. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. PubMed

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Learning Health Systems. 2017; https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/learning-health-systems/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2018.

3. Umscheid CA, Brennan PJ. Incentivizing “structures” over “outcomes” to bridge the knowing-doing gap. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):354-355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5293. PubMed

4. Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

5. Marquez C, Johnson AM, Jassemi S, et al. Enhancing the uptake of systematic reviews of effects: what is the best format for health care managers and policy-makers? A mixed-methods study. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0779-9. PubMed

6. Villa L, Warholak TL, Hines LE, et al. Health care decision makers’ use of comparative effectiveness research: report from a series of focus groups. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(9):745-754. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.9.745. PubMed

7. Guise JM, Savitz LA, Friedman CP. Mind the gap: putting evidence into practice in the era of learning health systems. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12): 2237-2239. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4633-1. PubMed

8. Ako-Arrey DE, Brouwers MC, Lavis JN, Giacomini MK. Health systems guidance appraisal--a critical interpretive synthesis. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):9. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0373-y. PubMed

9. White CM, Butler M, Wang Z, et al. Understanding Health-Systems’ Use of and Need for Evidence To Inform Decisionmaking. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. PubMed

10. Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke MJ, et al. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in decision-making by health system managers, policy makers, and clinicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(9):Cd009401. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009401.pub2. PubMed

11. Bornstein S, Baker R, Navarro P, Mackey S, Speed D, Sullivan M. Putting research in place: an innovative approach to providing contextualized evidence synthesis for decision makers. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0606-4. PubMed

12. Schoelles K, Umscheid CA, Lin JS, et al. A Framework for Conceptualizing Evidence Needs of Health Systems. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. PubMed

13. Chang S, Chang C, Borsky A. Putting the Evidence into Decision Making. Prevention Policy Matters Blog 2018; https://health.gov/news/blog/2018/04/putting-the-evidence-into-decision-making/. Accessed September 28, 2018.

14. Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness R. In: Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, Morton S, eds. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. https://www.nihlibrary.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Finding_What_Works_in_Health_Care_Standards_for_Systematic_Reviews_IOM_2011.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2019.

15. Butler M, Olson A, Drekonja D, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. In: Early Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Clostridium difficile: Update. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/c-difficile-update/research. Accessed January 17, 2019.

16. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455. doi: 10.1086/651706. PubMed

17. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7): e1-e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085. PubMed

18. Flores EJ, Mull NK, Lavenberg JG, et al. Utilizing a 10-step framework to support the implementation of an evidence-based clinical pathways. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018:bmjqs-2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008454. PubMed

19. Flores E, Jue JJ, Girardi G, Schoelles K, Umscheid CA. Use of a Clinical Pathway to Facilitate the Translation and Utilization of AHRQ EPC Report Findings. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: Prepared by the ECRI Institute–Penn Medicine Evidence-based Practice Center; 2018. PubMed

20. AHRQ methods for effective health care. In: Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB, eds. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014.

21. Hartling L, Guise JM, Kato E, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. In: EPC Methods: An Exploration of Methods and Context for the Production of Rapid Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2015. PubMed

22. Hartling L, Guise JM, Kato E, et al. A taxonomy of rapid reviews links report types and methods to specific decision-making contexts. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(12):1451-1462.e1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.036. PubMed

23. Hartling L, Guise JM, Hempel S, et al. AHRQ methods for effective health care. In: EPC Methods: AHRQ End-User Perspectives of Rapid Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. PubMed

24. Hartling L, Guise JM, Hempel S, et al. Fit for purpose: perspectives on rapid reviews from end-user interviews. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0425-7. PubMed

25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Synthesizing Evidence for Quality Improvement. 2018; https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/health-systems/quality-improvement. Accessed September 26, 2018.

Research evidence is critical for strengthening the value, quality, and safety of patient care. Learning healthcare systems (LHS) can support the delivery of evidence-based healthcare by establishing organizational processes that support three activities (Figure).1-3

- Knowledge: Identifying and synthesizing evidence to address clinical challenges

- Practice: Applying knowledge in the process of care delivery

- Data: Assessing performance and creating a feedback cycle for learning and improvement

The systematic implementation of evidence into practice continues to be a challenge for many healthcare organizations4-7 due to limited resources, expertise, and culture.5,8-12 Missing opportunities for translating knowledge into practice not only results in low-value care (ie, waste) but also in harm.1

The AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Program was established in 1997, with the goal of synthesizing research to inform evidence-based healthcare. The national impact of this program has been significant. Since the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, EPC program reports have been used to inform over 95 clinical practice guidelines from societies such as the American College of Physicians, 16 health coverage decisions from payers such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and 24 government policies and program planning efforts, such as the National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Program.13

The EPC program recognizes that evidence awareness is not sufficient to change practice and improve clinical outcomes. As such, the EPC program also embarked on initiatives to facilitate the translation of evidence into clinical practice and to measure and monitor how changes in practice impact health outcomes. AHRQ has historically worked with professional organizations to translate systematic reviews into clinical practice guidelines as well as federal agencies to inform payer decisions and program planning. Recently, the EPC program has increased collaborative efforts with hospitals and healthcare systems to understand how they use evidence and to partner with them to identify methods to improve the uptake of evidence into practice.9,12

In this perspective, we describe the AHRQ EPC Program’s work to address the three phases of the LHS cycle (knowledge, practice, and data) to support high-value care, using the topic of preventing and treating Clostridium difficile colitis as a relevant example to the hospital medicine field (Figure 2). By sharing this work, we hope it can serve as a model to illustrate how partnerships between organizations and AHRQ can lead to improvements in healthcare.

USING THE LEARNING HEALTHCARE SYSTEM CYCLE TO STRUCTURE AHRQ EPC WORK

Knowledge: Identifying and Synthesizing Evidence to Address Clinical Challenges

Systematic reviews use carefully formulated questions to summarize the literature results using specific and established methods.14 Given that individual studies can have disparate results, it is critical to summarize and synthesize findings across studies, so we know what the overall evidence suggests, and whether we can be confident in the findings. To date, the EPC program has developed more than 500 evidence synthesis reports. An example relevant to the field of hospital medicine is the 2016 review that examined the effects of interventions to prevent and treat Clostridium difficile colitis in adults.15

The review examined the best available evidence, including data from randomized controlled trials and observational studies, on diagnosing, preventing, and treating Clostridium difficile colitis. Major findings included the following: vancomycin is more effective than metronidazole for treating the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis (high-strength evidence), fecal transplantation may have a significant benefit in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis (low-strength evidence), and institutional preventive interventions such as antibiotic stewardship practices, transmission interruption through terminal room cleaning, and handwashing campaigns reduce the incidence of Clostridium difficile colitis (low-strength evidence). The report results provided the most recent review of the evidence and were particularly important as they suggested a need for significant practice changes in the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis based on the new evidence available. Previous to this report, the 2010 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommended metronidazole over vancomycin for the treatment of the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis.16 Subsequently, the newly released 2018 IDSA guideline provides recommendations consistent with the findings in this AHRQ report.17

Practice: Applying Knowledge in the Process of Care Delivery

AHRQ recognizes there are many interim steps between having the results from a systematic review and changing practice and improving care. In 2017, the EPC program began piloting approaches to make it easier for healthcare systems and hospitals to use its reports to improve the delivery of patient care and clinical outcomes. A pilot project conducted by the ECRI Institute - Penn Medicine EPC evaluated the feasibility of using an existing clinical pathway development and dissemination framework18 to translate findings from the 2016 AHRQ EPC report on Clostridium difficile colitis into a pathway for Clostridium difficile colitis treatment in the acute care setting.

To develop a Clostridium difficile colitis treatment pathway, the ECRI-Penn EPC team recruited a representative stakeholder group from Penn Medicine to review the EPC report as well as existing society guidelines. The clinical pathway was subsequently developed and approved by the stakeholders and disseminated through the Penn Medicine cloud-based pathways repository beginning on April 16, 2018.19 Most recently, the pathway became available in the electronic health record (EHR; 2018 Epic Systems Corporation) to facilitate provider review during care. Specifically, hyperlinks to the pathway are embedded within the ordering screens for those antibiotics used to treat Clostridium difficile colitis (ie, oral and rectal vancomycin, fidaxomicin, and metronidazole). Upon clicking the link in the ordering screen, the pathway launches a floating internet explorer window. The pathway is now publicly available on the AHRQ’s Clinical Decision Support (CDS) Connect Project (https://cds.ahrq.gov/), which is a resource to share pathway artifacts for other healthcare systems to use.

Data: Assessing Performance and Creating a Feedback Cycle for Learning and Improvement

The last step in the LHS cycle is to identify the impact of interventions on practice change and clinical outcomes, to understand how local results compare to peer institutions, and to inform future research and knowledge.

For the ECRI Institute-Penn Medicine EPC pilot project, both qualitative and quantitative outcomes were assessed. The initial qualitative analysis focused on the feasibility of using the AHRQ report in an existing pathway development and dissemination framework.18 It was found that clinical stakeholders identified the EPC report as trustworthy and more current than the society guidelines available at the time of development, particularly regarding the finding that vancomycin was more effective than metronidazole for the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis. Additional qualitative analysis will be conducted to understand provider satisfaction with the pathway and practice impact. The quantitative analysis focused on pathway use (clicks over time) and found that as of September 16, 2018, the pathway had been viewed by providers 403 times. Future analysis will evaluate the impact of the pathway on the use of oral vancomycin for the first occurrences of Clostridium difficile colitis.

Patient registries can also help clinicians and healthcare systems to complete the feedback cycle and evaluate outcomes. Patient registries collect data from clinical and other sources in a standardized way in order to evaluate specific outcomes for various populations.20 AHRQ has created a registry handbook, including best practices for how to create, operate, and evaluate registries.20 This handbook enables the development of high-quality registries with data that can be leveraged for both research and improvement.

In the example of the ECRI Institute-Penn Medicine EPC pilot project, one way that a learning healthcare system, such as Penn Medicine, might measure the impact of the clinical pathway is to develop a quality improvement registry, which might be developed with information from their electronic health record, to examine the impact on the use of vancomycin for first occurrences of Clostridium difficile colitis. This information could help drive improvement in the implementation of the clinical pathway.

Registries can also be used as a source for research data. The NIH-funded American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry is an example of a research registry that collects data on outcomes and adverse events associated with fecal transplants to fill gaps in existing research. The 2016 AHRQ EPC review found low-strength evidence on fecal transplant for treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis. When designing the protocol for this registry, the researchers used the AHRQ handbook to inform the design. Given that this is a research registry, it can be used by researchers to examine trends and outcomes of fecal transplant to treat Clostridium difficile colitis. Publications that use the registry as its source of data may be used in future systematic reviews, thus completing the cycle of learning.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

The EPC program recognizes that gaps remain in the evidence to practice translation process and that more support is needed. Some upcoming activities of the AHRQ EPC Program to address these gaps and make its evidence reports more actionable for healthcare systems include:

- Projects to Disseminate EPC Reports into Clinical Practice. In addition to the ECRI Institute - Penn Medicine EPC pilot dissemination project, other pilot projects are aimed at helping systems apply evidence to practice and include new ways to visualize evidence to make it more actionable and usable; creating other dissemination products, such as evidence summaries and presentations for decision makers; and other implementation tools, such as decision aids. These products and summary reports are available on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Program website at https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/health-systems-use-evidence/overview.

- Healthcare Systems Stakeholder Panel. Starting in Fall 2018, the AHRQ EPC Program will be convening a panel of healthcare system leaders to help make its reports and products more useful and responsive to the needs of healthcare systems and promote the use of evidence in clinical practice.

- Rapid Evidence Products. AHRQ understands that healthcare systems need information rapidly and cannot wait a year or more for a traditional systematic review to be completed. Therefore, AHRQ is applying its methods work on rapid reviews21-24 to pilot new report types that systematically identify and summarize the evidence quickly for healthcare systems and quality improvement efforts.25

- Data Integration. Originally launched in 2012, the Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR) is an AHRQ-supported online open-access repository of abstracted data from individual studies from systematic reviews. The goal is to enable more efficient updates of systematic reviews through data reuse. An updated version of the SRDR is scheduled to launch in 2020. With the new version, future sharing of summary data from systematic reviews digitally in a computable and portable format may allow integration into CDS tools and clinical practice guideline development and dissemination, facilitating the use of evidence in clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The AHRQ EPC program supports initiatives to make evidence more actionable and provide resources and tools throughout all the phases of the learning healthcare system cycle. This case study on C. difficile is one example of how the EPC program is helping hospitals and healthcare systems improve clinical care delivery and its derivative value.

Disclosures

Dr. Umscheid reports grants from AHRQ, during the conduct of the study; serves on the Advisory Board of DynaMed, and founded and directed a hospital-based evidence-based practice center. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s), who are responsible for its content, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Research evidence is critical for strengthening the value, quality, and safety of patient care. Learning healthcare systems (LHS) can support the delivery of evidence-based healthcare by establishing organizational processes that support three activities (Figure).1-3

- Knowledge: Identifying and synthesizing evidence to address clinical challenges

- Practice: Applying knowledge in the process of care delivery

- Data: Assessing performance and creating a feedback cycle for learning and improvement

The systematic implementation of evidence into practice continues to be a challenge for many healthcare organizations4-7 due to limited resources, expertise, and culture.5,8-12 Missing opportunities for translating knowledge into practice not only results in low-value care (ie, waste) but also in harm.1

The AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Program was established in 1997, with the goal of synthesizing research to inform evidence-based healthcare. The national impact of this program has been significant. Since the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, EPC program reports have been used to inform over 95 clinical practice guidelines from societies such as the American College of Physicians, 16 health coverage decisions from payers such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and 24 government policies and program planning efforts, such as the National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Program.13

The EPC program recognizes that evidence awareness is not sufficient to change practice and improve clinical outcomes. As such, the EPC program also embarked on initiatives to facilitate the translation of evidence into clinical practice and to measure and monitor how changes in practice impact health outcomes. AHRQ has historically worked with professional organizations to translate systematic reviews into clinical practice guidelines as well as federal agencies to inform payer decisions and program planning. Recently, the EPC program has increased collaborative efforts with hospitals and healthcare systems to understand how they use evidence and to partner with them to identify methods to improve the uptake of evidence into practice.9,12

In this perspective, we describe the AHRQ EPC Program’s work to address the three phases of the LHS cycle (knowledge, practice, and data) to support high-value care, using the topic of preventing and treating Clostridium difficile colitis as a relevant example to the hospital medicine field (Figure 2). By sharing this work, we hope it can serve as a model to illustrate how partnerships between organizations and AHRQ can lead to improvements in healthcare.

USING THE LEARNING HEALTHCARE SYSTEM CYCLE TO STRUCTURE AHRQ EPC WORK

Knowledge: Identifying and Synthesizing Evidence to Address Clinical Challenges

Systematic reviews use carefully formulated questions to summarize the literature results using specific and established methods.14 Given that individual studies can have disparate results, it is critical to summarize and synthesize findings across studies, so we know what the overall evidence suggests, and whether we can be confident in the findings. To date, the EPC program has developed more than 500 evidence synthesis reports. An example relevant to the field of hospital medicine is the 2016 review that examined the effects of interventions to prevent and treat Clostridium difficile colitis in adults.15

The review examined the best available evidence, including data from randomized controlled trials and observational studies, on diagnosing, preventing, and treating Clostridium difficile colitis. Major findings included the following: vancomycin is more effective than metronidazole for treating the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis (high-strength evidence), fecal transplantation may have a significant benefit in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis (low-strength evidence), and institutional preventive interventions such as antibiotic stewardship practices, transmission interruption through terminal room cleaning, and handwashing campaigns reduce the incidence of Clostridium difficile colitis (low-strength evidence). The report results provided the most recent review of the evidence and were particularly important as they suggested a need for significant practice changes in the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis based on the new evidence available. Previous to this report, the 2010 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommended metronidazole over vancomycin for the treatment of the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis.16 Subsequently, the newly released 2018 IDSA guideline provides recommendations consistent with the findings in this AHRQ report.17

Practice: Applying Knowledge in the Process of Care Delivery

AHRQ recognizes there are many interim steps between having the results from a systematic review and changing practice and improving care. In 2017, the EPC program began piloting approaches to make it easier for healthcare systems and hospitals to use its reports to improve the delivery of patient care and clinical outcomes. A pilot project conducted by the ECRI Institute - Penn Medicine EPC evaluated the feasibility of using an existing clinical pathway development and dissemination framework18 to translate findings from the 2016 AHRQ EPC report on Clostridium difficile colitis into a pathway for Clostridium difficile colitis treatment in the acute care setting.

To develop a Clostridium difficile colitis treatment pathway, the ECRI-Penn EPC team recruited a representative stakeholder group from Penn Medicine to review the EPC report as well as existing society guidelines. The clinical pathway was subsequently developed and approved by the stakeholders and disseminated through the Penn Medicine cloud-based pathways repository beginning on April 16, 2018.19 Most recently, the pathway became available in the electronic health record (EHR; 2018 Epic Systems Corporation) to facilitate provider review during care. Specifically, hyperlinks to the pathway are embedded within the ordering screens for those antibiotics used to treat Clostridium difficile colitis (ie, oral and rectal vancomycin, fidaxomicin, and metronidazole). Upon clicking the link in the ordering screen, the pathway launches a floating internet explorer window. The pathway is now publicly available on the AHRQ’s Clinical Decision Support (CDS) Connect Project (https://cds.ahrq.gov/), which is a resource to share pathway artifacts for other healthcare systems to use.

Data: Assessing Performance and Creating a Feedback Cycle for Learning and Improvement

The last step in the LHS cycle is to identify the impact of interventions on practice change and clinical outcomes, to understand how local results compare to peer institutions, and to inform future research and knowledge.

For the ECRI Institute-Penn Medicine EPC pilot project, both qualitative and quantitative outcomes were assessed. The initial qualitative analysis focused on the feasibility of using the AHRQ report in an existing pathway development and dissemination framework.18 It was found that clinical stakeholders identified the EPC report as trustworthy and more current than the society guidelines available at the time of development, particularly regarding the finding that vancomycin was more effective than metronidazole for the first occurrence of Clostridium difficile colitis. Additional qualitative analysis will be conducted to understand provider satisfaction with the pathway and practice impact. The quantitative analysis focused on pathway use (clicks over time) and found that as of September 16, 2018, the pathway had been viewed by providers 403 times. Future analysis will evaluate the impact of the pathway on the use of oral vancomycin for the first occurrences of Clostridium difficile colitis.

Patient registries can also help clinicians and healthcare systems to complete the feedback cycle and evaluate outcomes. Patient registries collect data from clinical and other sources in a standardized way in order to evaluate specific outcomes for various populations.20 AHRQ has created a registry handbook, including best practices for how to create, operate, and evaluate registries.20 This handbook enables the development of high-quality registries with data that can be leveraged for both research and improvement.

In the example of the ECRI Institute-Penn Medicine EPC pilot project, one way that a learning healthcare system, such as Penn Medicine, might measure the impact of the clinical pathway is to develop a quality improvement registry, which might be developed with information from their electronic health record, to examine the impact on the use of vancomycin for first occurrences of Clostridium difficile colitis. This information could help drive improvement in the implementation of the clinical pathway.

Registries can also be used as a source for research data. The NIH-funded American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry is an example of a research registry that collects data on outcomes and adverse events associated with fecal transplants to fill gaps in existing research. The 2016 AHRQ EPC review found low-strength evidence on fecal transplant for treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis. When designing the protocol for this registry, the researchers used the AHRQ handbook to inform the design. Given that this is a research registry, it can be used by researchers to examine trends and outcomes of fecal transplant to treat Clostridium difficile colitis. Publications that use the registry as its source of data may be used in future systematic reviews, thus completing the cycle of learning.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

The EPC program recognizes that gaps remain in the evidence to practice translation process and that more support is needed. Some upcoming activities of the AHRQ EPC Program to address these gaps and make its evidence reports more actionable for healthcare systems include:

- Projects to Disseminate EPC Reports into Clinical Practice. In addition to the ECRI Institute - Penn Medicine EPC pilot dissemination project, other pilot projects are aimed at helping systems apply evidence to practice and include new ways to visualize evidence to make it more actionable and usable; creating other dissemination products, such as evidence summaries and presentations for decision makers; and other implementation tools, such as decision aids. These products and summary reports are available on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Program website at https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/health-systems-use-evidence/overview.

- Healthcare Systems Stakeholder Panel. Starting in Fall 2018, the AHRQ EPC Program will be convening a panel of healthcare system leaders to help make its reports and products more useful and responsive to the needs of healthcare systems and promote the use of evidence in clinical practice.

- Rapid Evidence Products. AHRQ understands that healthcare systems need information rapidly and cannot wait a year or more for a traditional systematic review to be completed. Therefore, AHRQ is applying its methods work on rapid reviews21-24 to pilot new report types that systematically identify and summarize the evidence quickly for healthcare systems and quality improvement efforts.25

- Data Integration. Originally launched in 2012, the Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR) is an AHRQ-supported online open-access repository of abstracted data from individual studies from systematic reviews. The goal is to enable more efficient updates of systematic reviews through data reuse. An updated version of the SRDR is scheduled to launch in 2020. With the new version, future sharing of summary data from systematic reviews digitally in a computable and portable format may allow integration into CDS tools and clinical practice guideline development and dissemination, facilitating the use of evidence in clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The AHRQ EPC program supports initiatives to make evidence more actionable and provide resources and tools throughout all the phases of the learning healthcare system cycle. This case study on C. difficile is one example of how the EPC program is helping hospitals and healthcare systems improve clinical care delivery and its derivative value.

Disclosures

Dr. Umscheid reports grants from AHRQ, during the conduct of the study; serves on the Advisory Board of DynaMed, and founded and directed a hospital-based evidence-based practice center. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s), who are responsible for its content, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in A, Institute of M. In: Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM, eds. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. PubMed

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Learning Health Systems. 2017; https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/learning-health-systems/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2018.

3. Umscheid CA, Brennan PJ. Incentivizing “structures” over “outcomes” to bridge the knowing-doing gap. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):354-355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5293. PubMed

4. Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

5. Marquez C, Johnson AM, Jassemi S, et al. Enhancing the uptake of systematic reviews of effects: what is the best format for health care managers and policy-makers? A mixed-methods study. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0779-9. PubMed

6. Villa L, Warholak TL, Hines LE, et al. Health care decision makers’ use of comparative effectiveness research: report from a series of focus groups. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(9):745-754. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.9.745. PubMed

7. Guise JM, Savitz LA, Friedman CP. Mind the gap: putting evidence into practice in the era of learning health systems. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12): 2237-2239. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4633-1. PubMed

8. Ako-Arrey DE, Brouwers MC, Lavis JN, Giacomini MK. Health systems guidance appraisal--a critical interpretive synthesis. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):9. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0373-y. PubMed

9. White CM, Butler M, Wang Z, et al. Understanding Health-Systems’ Use of and Need for Evidence To Inform Decisionmaking. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. PubMed

10. Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke MJ, et al. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in decision-making by health system managers, policy makers, and clinicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(9):Cd009401. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009401.pub2. PubMed

11. Bornstein S, Baker R, Navarro P, Mackey S, Speed D, Sullivan M. Putting research in place: an innovative approach to providing contextualized evidence synthesis for decision makers. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0606-4. PubMed

12. Schoelles K, Umscheid CA, Lin JS, et al. A Framework for Conceptualizing Evidence Needs of Health Systems. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. PubMed

13. Chang S, Chang C, Borsky A. Putting the Evidence into Decision Making. Prevention Policy Matters Blog 2018; https://health.gov/news/blog/2018/04/putting-the-evidence-into-decision-making/. Accessed September 28, 2018.

14. Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness R. In: Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, Morton S, eds. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. https://www.nihlibrary.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Finding_What_Works_in_Health_Care_Standards_for_Systematic_Reviews_IOM_2011.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2019.

15. Butler M, Olson A, Drekonja D, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. In: Early Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Clostridium difficile: Update. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/c-difficile-update/research. Accessed January 17, 2019.

16. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455. doi: 10.1086/651706. PubMed

17. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7): e1-e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085. PubMed

18. Flores EJ, Mull NK, Lavenberg JG, et al. Utilizing a 10-step framework to support the implementation of an evidence-based clinical pathways. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018:bmjqs-2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008454. PubMed

19. Flores E, Jue JJ, Girardi G, Schoelles K, Umscheid CA. Use of a Clinical Pathway to Facilitate the Translation and Utilization of AHRQ EPC Report Findings. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: Prepared by the ECRI Institute–Penn Medicine Evidence-based Practice Center; 2018. PubMed

20. AHRQ methods for effective health care. In: Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB, eds. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014.

21. Hartling L, Guise JM, Kato E, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. In: EPC Methods: An Exploration of Methods and Context for the Production of Rapid Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2015. PubMed

22. Hartling L, Guise JM, Kato E, et al. A taxonomy of rapid reviews links report types and methods to specific decision-making contexts. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(12):1451-1462.e1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.036. PubMed

23. Hartling L, Guise JM, Hempel S, et al. AHRQ methods for effective health care. In: EPC Methods: AHRQ End-User Perspectives of Rapid Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. PubMed

24. Hartling L, Guise JM, Hempel S, et al. Fit for purpose: perspectives on rapid reviews from end-user interviews. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0425-7. PubMed

25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Synthesizing Evidence for Quality Improvement. 2018; https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/health-systems/quality-improvement. Accessed September 26, 2018.

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in A, Institute of M. In: Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM, eds. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. PubMed

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Learning Health Systems. 2017; https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/learning-health-systems/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2018.

3. Umscheid CA, Brennan PJ. Incentivizing “structures” over “outcomes” to bridge the knowing-doing gap. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):354-355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5293. PubMed

4. Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

5. Marquez C, Johnson AM, Jassemi S, et al. Enhancing the uptake of systematic reviews of effects: what is the best format for health care managers and policy-makers? A mixed-methods study. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0779-9. PubMed

6. Villa L, Warholak TL, Hines LE, et al. Health care decision makers’ use of comparative effectiveness research: report from a series of focus groups. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(9):745-754. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.9.745. PubMed

7. Guise JM, Savitz LA, Friedman CP. Mind the gap: putting evidence into practice in the era of learning health systems. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12): 2237-2239. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4633-1. PubMed

8. Ako-Arrey DE, Brouwers MC, Lavis JN, Giacomini MK. Health systems guidance appraisal--a critical interpretive synthesis. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):9. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0373-y. PubMed

9. White CM, Butler M, Wang Z, et al. Understanding Health-Systems’ Use of and Need for Evidence To Inform Decisionmaking. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. PubMed

10. Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke MJ, et al. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in decision-making by health system managers, policy makers, and clinicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(9):Cd009401. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009401.pub2. PubMed

11. Bornstein S, Baker R, Navarro P, Mackey S, Speed D, Sullivan M. Putting research in place: an innovative approach to providing contextualized evidence synthesis for decision makers. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0606-4. PubMed

12. Schoelles K, Umscheid CA, Lin JS, et al. A Framework for Conceptualizing Evidence Needs of Health Systems. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. PubMed

13. Chang S, Chang C, Borsky A. Putting the Evidence into Decision Making. Prevention Policy Matters Blog 2018; https://health.gov/news/blog/2018/04/putting-the-evidence-into-decision-making/. Accessed September 28, 2018.

14. Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness R. In: Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, Morton S, eds. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. https://www.nihlibrary.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Finding_What_Works_in_Health_Care_Standards_for_Systematic_Reviews_IOM_2011.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2019.

15. Butler M, Olson A, Drekonja D, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. In: Early Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Clostridium difficile: Update. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/c-difficile-update/research. Accessed January 17, 2019.

16. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455. doi: 10.1086/651706. PubMed

17. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7): e1-e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085. PubMed

18. Flores EJ, Mull NK, Lavenberg JG, et al. Utilizing a 10-step framework to support the implementation of an evidence-based clinical pathways. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018:bmjqs-2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008454. PubMed

19. Flores E, Jue JJ, Girardi G, Schoelles K, Umscheid CA. Use of a Clinical Pathway to Facilitate the Translation and Utilization of AHRQ EPC Report Findings. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: Prepared by the ECRI Institute–Penn Medicine Evidence-based Practice Center; 2018. PubMed

20. AHRQ methods for effective health care. In: Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB, eds. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014.

21. Hartling L, Guise JM, Kato E, et al. AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews. In: EPC Methods: An Exploration of Methods and Context for the Production of Rapid Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2015. PubMed

22. Hartling L, Guise JM, Kato E, et al. A taxonomy of rapid reviews links report types and methods to specific decision-making contexts. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(12):1451-1462.e1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.036. PubMed

23. Hartling L, Guise JM, Hempel S, et al. AHRQ methods for effective health care. In: EPC Methods: AHRQ End-User Perspectives of Rapid Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. PubMed

24. Hartling L, Guise JM, Hempel S, et al. Fit for purpose: perspectives on rapid reviews from end-user interviews. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0425-7. PubMed

25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Synthesizing Evidence for Quality Improvement. 2018; https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/health-systems/quality-improvement. Accessed September 26, 2018.

©2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

National Survey of Hospitalists’ Experiences with Incidental Pulmonary Nodules

Pulmonary nodules are common, and their identification is increasing as a result of the use of more sensitive chest imaging modalities.1 Pulmonary nodules are defined on imaging as small (≤30 mm), well-defined lesions, completely surrounded by pulmonary parenchyma.2 Most of the pulmonary nodules detected incidentally (ie, in asymptomatic patients outside the context of chest CT screening for lung cancer) are benign.1 Lesions >30 mm are defined as masses and have higher risks of malignancy.2

Because the majority of patients will not benefit from the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules (IPNs), improving the benefits and minimizing the harms of IPN follow-up are critical. The Fleischner Society3 published their first guideline on the management of solid IPNs in 2005,4 which was supplemented in 2013 with specific guidance for the management of subsolid IPNs.5 In 2017, both guidelines were combined in a single update.6 The Fleischner Society recommendations for imaging surveillance and tissue sampling are based on nodule type (solid vs subsolid), number (single vs multiple), size, appearance, and patient risk for malignancy.

For IPNs identified in the hospital, management may be particularly challenging. For one, the provider initially ordering the chest imaging may not be the provider coordinating the patient’s discharge, leading to a lack of knowledge that the IPN even exists. The hospitalist to primary care provider (PCP) handoff may also have vulnerabilities, including the lack of inclusion of the IPN follow-up in the discharge summary and the nonreceipt of the discharge summary by the PCP. Moreover, because a patient’s acute medical problems often take precedence during a hospitalization, inpatients may not even be made aware of identified IPNs and the need for follow-up. Thus, the absence of standardized approaches to managing IPNs is a threat to patient safety, as well as a legal liability for providers and their institutions.

To better understand the current state of IPN management in our own institution, we examined the management of IPNs identified by chest computed tomographies (CTs) performed for inpatients on our general medicine services over a two-year period.7 Among the 50 inpatients identified with IPNs requiring follow-up, 78% had no follow-up imaging documented. Moreover, 40% had no mention of the IPN in their hospital summary or discharge instructions.

To inform our approach to addressing this challenge, we sought to examine the practices of hospitalist physicians nationally regarding the management of IPNs, including hospitalists’ familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines.

METHODS

We developed a 14-item survey to assess hospitalists’ exposure to and management of IPNs. The survey targeted attendees of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual conference and was available for completion on a tablet at the conference registration desk, the SHM kiosk in the exhibit hall, and at the entrance and exit of the morning plenary sessions. Following the annual conference, the survey was e-mailed to conference attendees, with one follow-up e-mailed to nonresponders.

Analyses were descriptive and included proportions for categorical variables and median and mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables. In addition, we examined the association between survey items and a response of “yes” to the question “Are you familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines for the management of incidental pulmonary nodules?”

Associations between familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines and survey items were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables with small sample sizes, the Cochran–Armitage test for trend for ordinal variables, and the t-test for continuous variables. The associations between categorical items were measured by odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical tests were two-sided using a P =.05 level for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with the R packages MASS, stats, and Publish. Institutional review board exemption was granted.

RESULTS

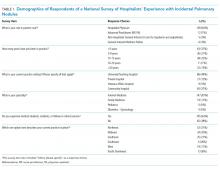

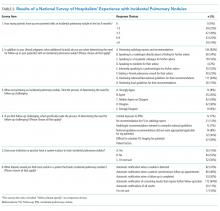

We received 174 responses from a total of 3,954 conference attendees. The majority were identified as hospitalist physicians, and most of them were internists (Table 1). About half practiced at a university or a teaching hospital, and more than half supervised trainees and practiced for more than five years. Respondents were involved in direct patient care (whether a teaching or a nonteaching service) for a median of 28 weeks annually (mean 31.2 weeks, standard deviation 13.5), and practice regions were geographically diverse. All respondents reported seeing at least one IPN case in the past six months, with most seeing three or more cases (Table 2). Despite this exposure, 42% were unfamiliar with the Fleischner Society guidelines. When determining the need for IPN follow-up, most of them utilized radiology report recommendations or consulted national or international guidelines, and a third spoke with radiologists directly. About a third agreed that determining the need for follow-up was challenging, with 39% citing patient factors (eg, lack of insurance, poor access to healthcare), and 30% citing scheduling of follow-up imaging. Few reported the availability of an automated tracking system at their institution, although most of them desired automatic notifications of results requiring follow-up.

Unadjusted analyses revealed that supervision of trainees and seeing more IPN cases significantly increased the odds of a survey respondent being familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.04-3.68, P =.05, and OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.12-2.18, P =.008, respectively; Supplementary Table 1).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the survey reported here is the first to examine hospitalists’ knowledge of the Fleischner Society guidelines and their approach to management of IPNs. Although our data suggest that hospitalists are less familiar with the Fleischner Society recommendations than pulmonologists8 and radiologists,8-10 the majority of hospitalists in our study rely on radiology report recommendations to inform follow-up. This suggests that embedding the Fleischner Society recommendations into radiology reports is an effective method to promote adherence to these recommendations, which has been demonstrated in previous research.11-13 Our study also suggests that hospitalists with more IPN exposure and those who supervise trainees are more likely to be aware of the Fleischner Society recommendations, which is similar to findings from studies examining radiologists and pulmonologists.8-9

Our findings highlight other opportunities for quality improvement in IPN management. Almost a quarter of hospitalists reported formally consulting pulmonologists for IPN management. Hospitalist groups wishing to improve value could partner with their radiology departments and embed the Fleischner Society recommendations into their imaging reports to potentially reduce unnecessary pulmonary consultations. Among the 59 hospitalists who agreed that IPN management was challenging, a majority cited the scheduling process (30%) as a barrier. Redesigning the scheduling process for follow-up imaging could be a focus in local efforts to improve IPN management. Strengthening communication between hospitalists and PCPs may provide additional opportunities for improved IPN follow-up, given the centrality of PCPs to ensuring such follow-up. This might include enhancing direct communication between hospitalists and PCPs for high-risk patients, or creating systems to ensure robust indirect communication, such as the implementation of standardized discharge summaries that uniformly include essential follow-up information.

At our institution, given the large volume of high-risk patients and imaging performed, and the available resources, we have established an IPN consult team to improve follow-up for inpatients with IPNs identified by chest CTs on Medicine services. The team includes a nurse practitioner (NP) and a pulmonologist who consult by default, to notify patients of their findings and recommended follow-up, and communicate results to their PCPs. The IPN consult team also sees patients for follow-up in the ambulatory IPN clinic. This initiative has addressed the most frequently cited challenges identified in our nationwide hospitalist survey by taking the communication and follow-up out of the hospitalists’ hands. To ensure identification of all IPNs by the NP, our radiology department has created a structured template for radiology attendings to document follow-up for all chest CTs reviewed based on the Fleischner Society guidelines. Compliance with use of the template by radiologists is followed monthly. After a run-in period, almost 100% of chest CT reports use the structured template, consistent with published findings from similar initiatives,14 and 100% of patients with new IPNs identified on the inpatient Medicine services have had an IPN consult.

The major limitation of our survey study is the response rate. It is difficult to determine in what direction this could bias our results, as those with and without experience in managing IPNs may have been equally likely to complete the survey. Despite the low response rate, our sample targeted the general cohort of conference attendees (rather than specific forums such as audiences interested in quality or imaging), and the descriptive characteristics of our convenience sample align well with the overall conference attendee demographics (eg, conference attendees were 77% hospitalist attendings and 9% advanced practice providers, as compared with 82% and 7% of survey respondents, respectively), suggesting that our respondents were representative of conference attendees as a whole.

Next steps for this work at our institution include developing systems to ensure appropriate follow-up for those with IPNs identified on chest CTs performed for Medicine outpatients. In addition, our institution is collaborating on a national study to compare outcomes resulting from following the traditional Fleischner Society recommendations compared to the new 2017 recommendations, which recommend more lenient follow-up.15

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Vivek Ahya, Eduardo Barbosa Jr., Tammy Tursi, and Anil Vachani for their leadership of the local quality improvement initiatives described in our Discussion, namely, the development and implementation of the structured templates for radiology reports and the incidental pulmonary nodule consult team.

Disclosures

Dr. Cook reports relevant financial activity outside the submitted work, including royalties from Osler Institute and grants from ACRIN and Beryl Institute. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study. There was no financial support for this study.

Previous Presentations

Presented as a poster at the 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference, Las Vegas, NV: Wilen J, Garin M, Umscheid CA, Cook TS, Myers JS. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules: a survey of hospitalists nationwide [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2017; 12 (Suppl 2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/follow-up-of-incidental-pulmonary-nodules-a-survey-of-hospitalists-nationwide/. Accessed March 18, 2018.

1. Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Clinical Practice: the solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2535-2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012290 PubMed

2. Tuddenham WJ. Glossary of terms for thoracic radiology: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(3):509-517. PubMed

3. Janower ML. A brief history of the Fleischner Society. J Thorac Imaging. 2010;25(1):27-28. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181cc4cee. PubMed

4. Macmahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237(2):395-400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. PubMed

5. Naidich DP, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2013;266(1):304-317. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120628. PubMed

6. MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology.2017;284(1):228-243. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161659. PubMed

7. Garin M, Soran C, Cook T, Ferguson M, Day S, Myers JS. Communication and follow-up of incidental lung nodules found on chest CT in a hospitalized and ambulatory patient population. J Hosp Med. 2014:9(2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/communication-and-followup-of-incidental-lung-nodules-found-on-chest-ct-in-a-hospitalized-and-ambulatory-patient-population/ Accessed June 14, 2018.

8. Mets OM, de Jong PA, Chung K, Lammers JWJ, van Ginneken B, Schaefer-Prokop CM. Fleischner recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules: high awareness but limited conformance – a survey study. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3840-3849. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4249-y. PubMed

9. Eisenberg RL, Bankier AA, Boiselle PM. Compliance with Fleischner Society Guidelines for management of small lung nodules: a survey of 834 radiologists. Radiology. 2010;255(1):218-224. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091556. PubMed

10. Eisenberg RL. Ways to improve radiologists’ adherence to Fleischner society guidelines for management of pulmonary nodules. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(6):439-441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.10.001. PubMed

11. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.08.003. PubMed

12. Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Dann E, Black WC. Using radiology reports to encourage evidence-based practice in the evaluation of small, incidentally detected pulmonary nodules: a preliminary study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(2):211-214. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-242BC. PubMed

13. McDonald JS, Koo CW, White D, Hartman TE, Bender CE, Sykes AMG. Addition of the Fleischner Society Guidelines to chest CT examination interpretive reports improves adherence to recommended follow-up care for incidental pulmonary nodules. Acad Radiol. 2017;24(3):337-344. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.08.026. PubMed

14. Zygmont ME, Shekhani H, Kerchberger JM, Johnson JO, Hanna TN. Point-of-Care reference materials increase practice compliance with societal guidelines for incidental findings in emergency imaging. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(12):1494-1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.07.032. PubMed

15. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Portfolio of Funded Projects. Available at: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/pragmatic-trial-more-versus-less-intensive-strategies-active-surveillance#/. Accessed May 22, 2018.

Pulmonary nodules are common, and their identification is increasing as a result of the use of more sensitive chest imaging modalities.1 Pulmonary nodules are defined on imaging as small (≤30 mm), well-defined lesions, completely surrounded by pulmonary parenchyma.2 Most of the pulmonary nodules detected incidentally (ie, in asymptomatic patients outside the context of chest CT screening for lung cancer) are benign.1 Lesions >30 mm are defined as masses and have higher risks of malignancy.2

Because the majority of patients will not benefit from the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules (IPNs), improving the benefits and minimizing the harms of IPN follow-up are critical. The Fleischner Society3 published their first guideline on the management of solid IPNs in 2005,4 which was supplemented in 2013 with specific guidance for the management of subsolid IPNs.5 In 2017, both guidelines were combined in a single update.6 The Fleischner Society recommendations for imaging surveillance and tissue sampling are based on nodule type (solid vs subsolid), number (single vs multiple), size, appearance, and patient risk for malignancy.

For IPNs identified in the hospital, management may be particularly challenging. For one, the provider initially ordering the chest imaging may not be the provider coordinating the patient’s discharge, leading to a lack of knowledge that the IPN even exists. The hospitalist to primary care provider (PCP) handoff may also have vulnerabilities, including the lack of inclusion of the IPN follow-up in the discharge summary and the nonreceipt of the discharge summary by the PCP. Moreover, because a patient’s acute medical problems often take precedence during a hospitalization, inpatients may not even be made aware of identified IPNs and the need for follow-up. Thus, the absence of standardized approaches to managing IPNs is a threat to patient safety, as well as a legal liability for providers and their institutions.

To better understand the current state of IPN management in our own institution, we examined the management of IPNs identified by chest computed tomographies (CTs) performed for inpatients on our general medicine services over a two-year period.7 Among the 50 inpatients identified with IPNs requiring follow-up, 78% had no follow-up imaging documented. Moreover, 40% had no mention of the IPN in their hospital summary or discharge instructions.

To inform our approach to addressing this challenge, we sought to examine the practices of hospitalist physicians nationally regarding the management of IPNs, including hospitalists’ familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines.

METHODS

We developed a 14-item survey to assess hospitalists’ exposure to and management of IPNs. The survey targeted attendees of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual conference and was available for completion on a tablet at the conference registration desk, the SHM kiosk in the exhibit hall, and at the entrance and exit of the morning plenary sessions. Following the annual conference, the survey was e-mailed to conference attendees, with one follow-up e-mailed to nonresponders.

Analyses were descriptive and included proportions for categorical variables and median and mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables. In addition, we examined the association between survey items and a response of “yes” to the question “Are you familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines for the management of incidental pulmonary nodules?”

Associations between familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines and survey items were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables with small sample sizes, the Cochran–Armitage test for trend for ordinal variables, and the t-test for continuous variables. The associations between categorical items were measured by odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical tests were two-sided using a P =.05 level for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with the R packages MASS, stats, and Publish. Institutional review board exemption was granted.

RESULTS

We received 174 responses from a total of 3,954 conference attendees. The majority were identified as hospitalist physicians, and most of them were internists (Table 1). About half practiced at a university or a teaching hospital, and more than half supervised trainees and practiced for more than five years. Respondents were involved in direct patient care (whether a teaching or a nonteaching service) for a median of 28 weeks annually (mean 31.2 weeks, standard deviation 13.5), and practice regions were geographically diverse. All respondents reported seeing at least one IPN case in the past six months, with most seeing three or more cases (Table 2). Despite this exposure, 42% were unfamiliar with the Fleischner Society guidelines. When determining the need for IPN follow-up, most of them utilized radiology report recommendations or consulted national or international guidelines, and a third spoke with radiologists directly. About a third agreed that determining the need for follow-up was challenging, with 39% citing patient factors (eg, lack of insurance, poor access to healthcare), and 30% citing scheduling of follow-up imaging. Few reported the availability of an automated tracking system at their institution, although most of them desired automatic notifications of results requiring follow-up.

Unadjusted analyses revealed that supervision of trainees and seeing more IPN cases significantly increased the odds of a survey respondent being familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.04-3.68, P =.05, and OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.12-2.18, P =.008, respectively; Supplementary Table 1).

DISCUSSION