User login

Cartilage Sutures for a Large Nasal Defect

Practice Gap

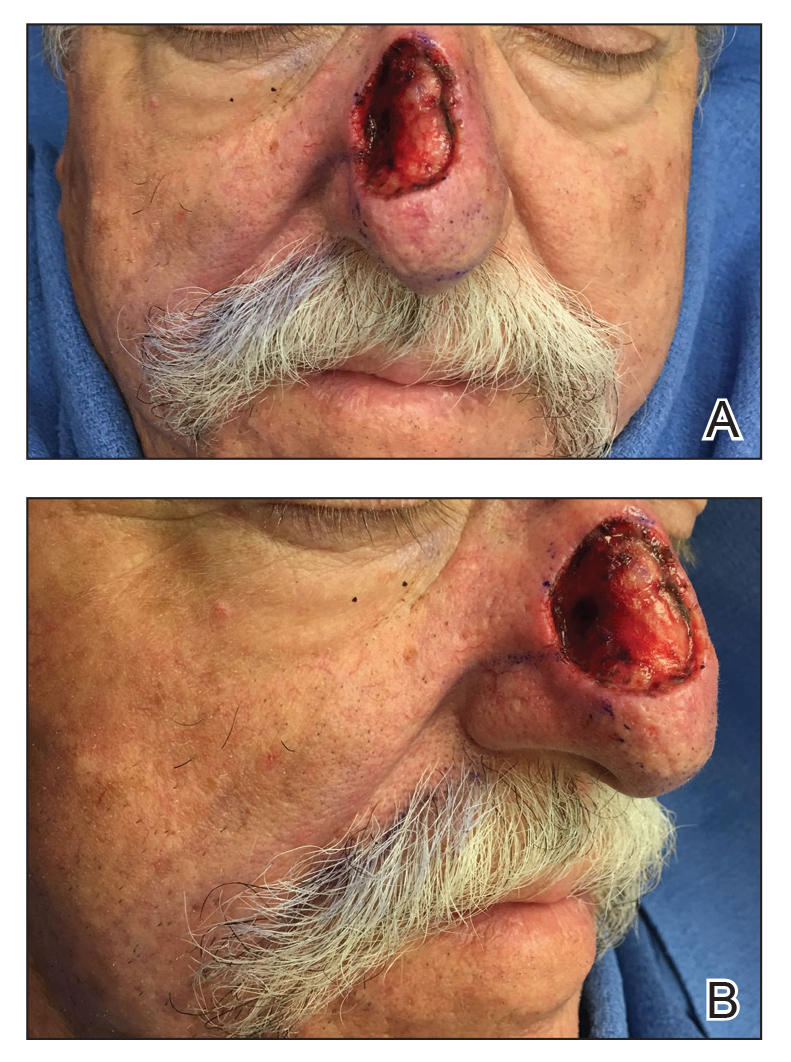

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

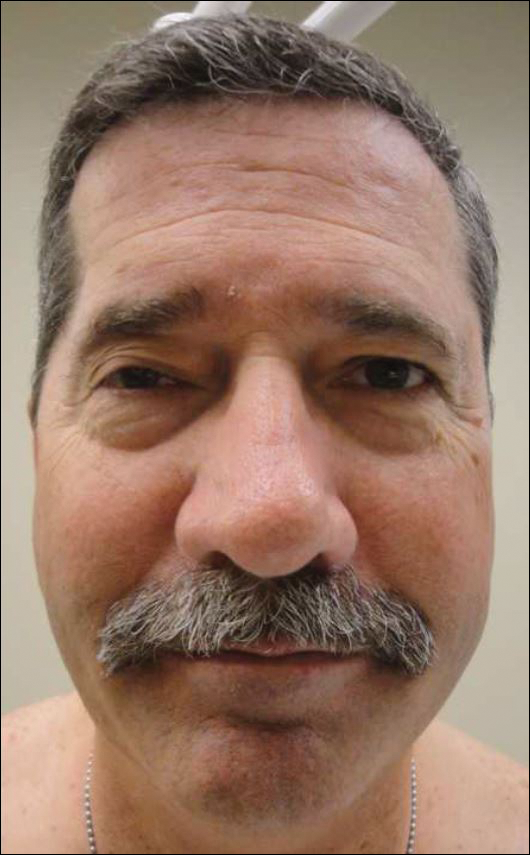

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Differentiating Trigeminal Motor Neuropathy and Progressive Hemifacial Atrophy

To the Editor:

Trigeminal motor neuropathy is a rare condition presenting with muscle weakness and atrophy in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve without sensory changes. We present a challenging case with clinical features that mimic progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA), a disease characterized by slowly progressive, unilateral facial atrophy that can be accompanied by inflammation and sclerosis as early features.

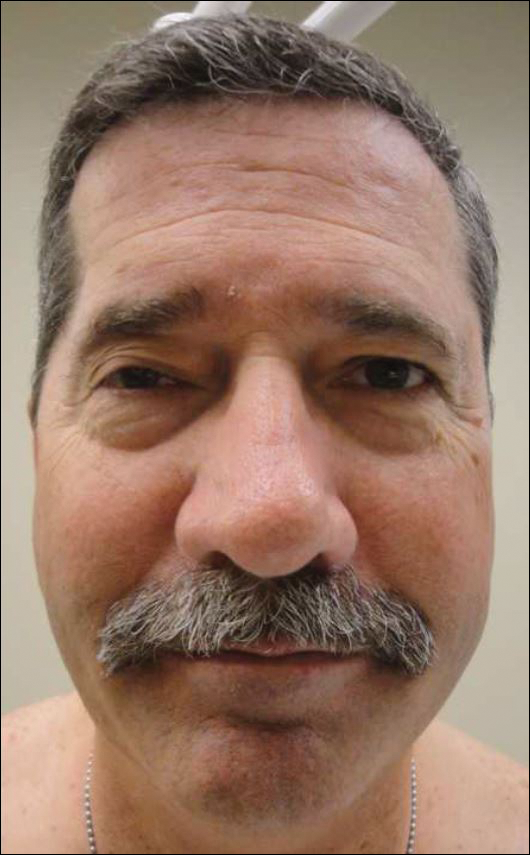

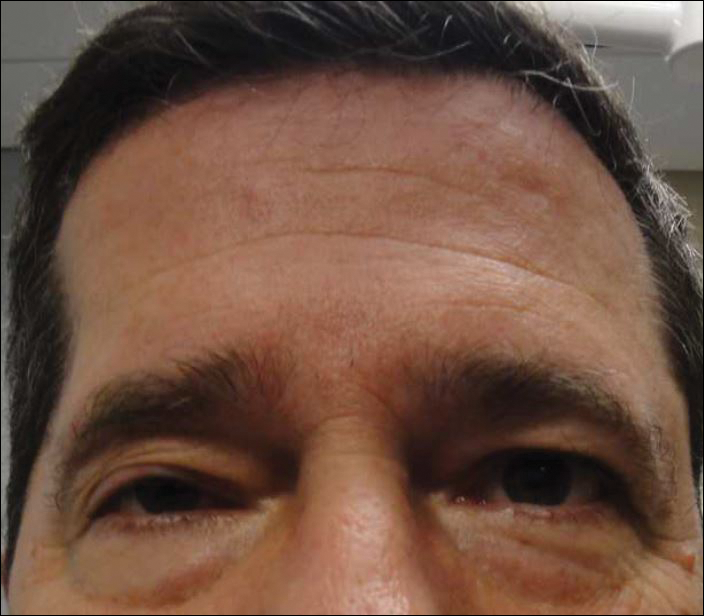

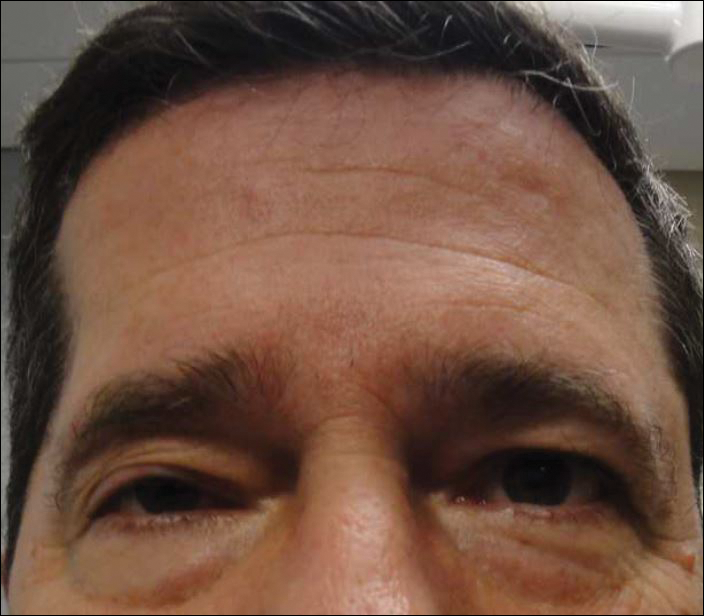

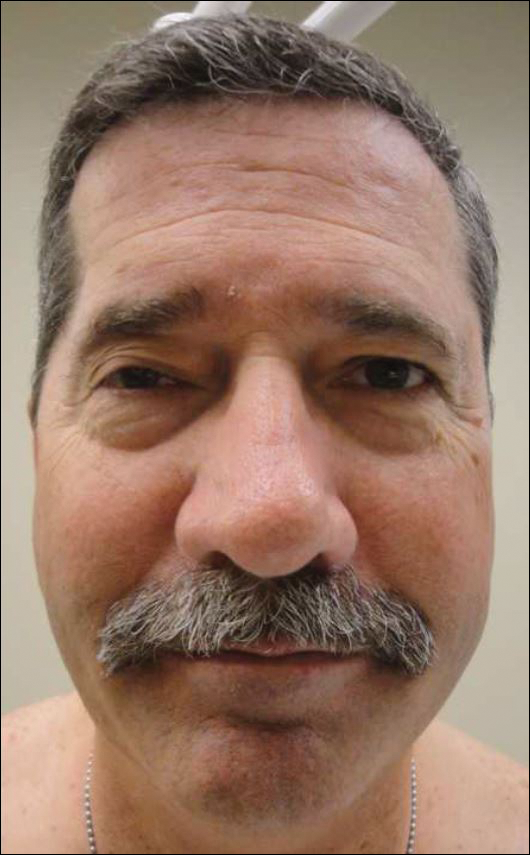

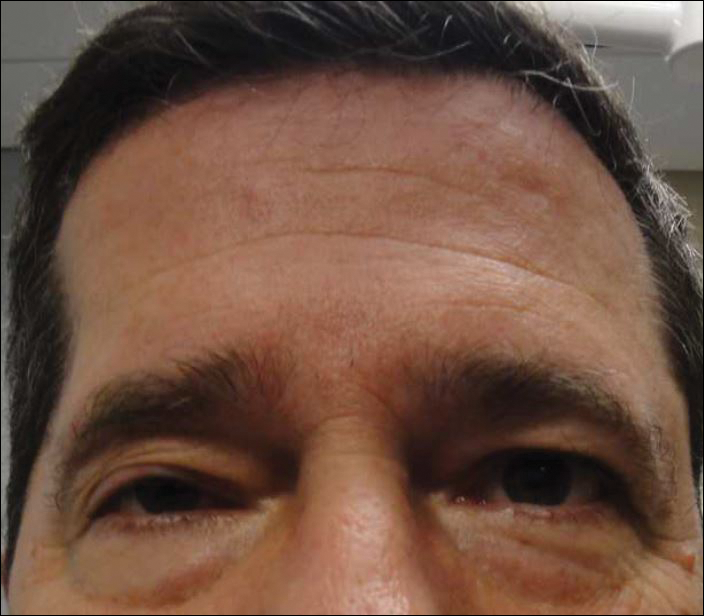

A 55-year-old man presented with right-sided ptosis and progressive right-sided facial atrophy of 4 years’ duration. A clinical diagnosis of PHA was made by the rheumatology department, and the patient was referred to the dermatology department for further evaluation. Examination at presentation revealed right-sided subcutaneous atrophy of the cheek, temple, and forehead extending to the scalp with absence of sclerosis, pigmentary alteration, or typical linear morphea lesions (Figures 1 and 2). The patient had no sensory changes in the affected area.

Workup by the dermatology department included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the face and scalp, which demonstrated denervation muscle atrophy exclusively in the distribution of the third branch of the right trigeminal nerve, including severe atrophy of the right temporalis and masseter muscles and moderate atrophy of the pterygoid muscles. No signs of inflammation, fibrosis, or atrophy of the skin or subcutaneous fat were found, ruling out a diagnosis of PHA.

The patient was referred to the neurology department where he was found to have a normal neurologic examination with the exception of right-sided ptosis and temporalis and masseter muscle atrophy. Notably, the patient had normal sensation in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve and normal strength of the masseter and temporalis muscles.

An extensive workup by the neurology department was completed, including magnetic resonance angiography, eyeblink testing, and testing for causes of neuropathies (eg, infectious, autoimmune, vitamin deficiencies, toxin related). Of note, magnetic resonance angiography showed no abnormalities within the cavernous sinus or trigeminal cave but showed potential vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, which was believed to be an incidental finding. The remainder of the workup was unremarkable. Based on muscle denervation atrophy in the distribution of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve in the absence of sensory symptoms or deficits, the patient’s presentation was consistent with trigeminal motor neuropathy.

In reported cases, the pathogenesis of trigeminal motor neuropathy is attributed to tumors, trauma, stroke, viral infection, and autoimmune reaction.1-6 In other reported cases the cause is unknown,6-8 as was the case in our patient. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed potential vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, which has been previously reported to cause trigeminal neuropathy.9 However, patients with trigeminal neuropathy presented with sensory changes in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve as opposed to motor symptoms and muscle atrophy.

We present a case of trigeminal motor neuropathy presenting as PHA. Progressive hemifacial atrophy is a rare, slowly progressive disease characterized by unilateral atrophy of the skin, subcutis, muscle, and bony structures of the face. Onset usually is during childhood, though later onset has been reported.10 The pathogenesis of PHA is not well understood, though trauma, infection, immune-mediated causes, sympathetic dysfunction, and metabolic dysfunction have been proposed.11 Diagnosis of PHA typically is based on clinical presentation, but histology and imaging are useful. In contrast to trigeminal motor neuropathy, MRI findings in PHA demonstrate involvement of the skin.12

Differentiation between PHA and trigeminal motor neuropathy is important because treatment differs. Treatment of trigeminal motor neuropathy depends on the etiology and may include removal of underlying neoplasms, while treatment of PHA depends on disease activity. The initial goal when treating PHA is to improve symptoms and slow disease progression; immunosuppressants may be considered. Facial reconstruction is an option when PHA is stable.

In this case, the features differentiating trigeminal motor neuropathy from PHA include age of onset and MRI as well as clinical findings of muscle atrophy limited to the distribution of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve. Although PHA is a rare disorder, this case demonstrates the importance of including trigeminal motor neuropathy in the differential diagnosis.

- Beydoun SR. Unilateral trigeminal motor neuropathy as a presenting feature of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:1136-1137.

- Kang YK, Lee EH, Hwang M. Pure trigeminal motor neuropathy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:995-998.

- Kim DH, Kim JK, Kang JY. Pure motor trigeminal neuropathy in a woman with tegmental pontine infarction. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1792-1794.

- Ko KF, Chan KL. A case of isolated pure trigeminal motor neuropathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1995;97:199-200.

- Park KS, Chung JM, Jeon BS, et al. Unilateral trigeminal mandibular motor neuropathy caused by tumor in the foramen ovale. J Clin Neurol. 2006;2:194-197.

- Chia LG. Pure trigeminal motor neuropathy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296:609-610.

- Braun JS, Hahn K, Bauknecht HC, et al. Progressive facial asymmetry due to trigeminal motor neuropathy. Eur Neurol. 2006;55:96-98.

- Chiba M, Echigo S. Unilateral atrophy of the masticatory muscles and mandibular ramus due to pure trigeminal motor neuropathy: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:E30-E34.

- Jannetta PJ, Robbins LJ. Trigeminal neuropathy—new observations. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:347-351.

- Stone J. Parry-Romberg syndrome: a global survey of 205 patients using the Internet. Neurology. 2003;61:674-676.

- El-Kehdy J, Abbas O, Rubeiz N. A review of Parry-Romberg syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:769-784.

- Taylor HM, Robinson R, Cox T. Progressive facial hemiatrophy: MRI appearances. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:484-486.

To the Editor:

Trigeminal motor neuropathy is a rare condition presenting with muscle weakness and atrophy in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve without sensory changes. We present a challenging case with clinical features that mimic progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA), a disease characterized by slowly progressive, unilateral facial atrophy that can be accompanied by inflammation and sclerosis as early features.

A 55-year-old man presented with right-sided ptosis and progressive right-sided facial atrophy of 4 years’ duration. A clinical diagnosis of PHA was made by the rheumatology department, and the patient was referred to the dermatology department for further evaluation. Examination at presentation revealed right-sided subcutaneous atrophy of the cheek, temple, and forehead extending to the scalp with absence of sclerosis, pigmentary alteration, or typical linear morphea lesions (Figures 1 and 2). The patient had no sensory changes in the affected area.

Workup by the dermatology department included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the face and scalp, which demonstrated denervation muscle atrophy exclusively in the distribution of the third branch of the right trigeminal nerve, including severe atrophy of the right temporalis and masseter muscles and moderate atrophy of the pterygoid muscles. No signs of inflammation, fibrosis, or atrophy of the skin or subcutaneous fat were found, ruling out a diagnosis of PHA.

The patient was referred to the neurology department where he was found to have a normal neurologic examination with the exception of right-sided ptosis and temporalis and masseter muscle atrophy. Notably, the patient had normal sensation in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve and normal strength of the masseter and temporalis muscles.

An extensive workup by the neurology department was completed, including magnetic resonance angiography, eyeblink testing, and testing for causes of neuropathies (eg, infectious, autoimmune, vitamin deficiencies, toxin related). Of note, magnetic resonance angiography showed no abnormalities within the cavernous sinus or trigeminal cave but showed potential vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, which was believed to be an incidental finding. The remainder of the workup was unremarkable. Based on muscle denervation atrophy in the distribution of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve in the absence of sensory symptoms or deficits, the patient’s presentation was consistent with trigeminal motor neuropathy.

In reported cases, the pathogenesis of trigeminal motor neuropathy is attributed to tumors, trauma, stroke, viral infection, and autoimmune reaction.1-6 In other reported cases the cause is unknown,6-8 as was the case in our patient. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed potential vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, which has been previously reported to cause trigeminal neuropathy.9 However, patients with trigeminal neuropathy presented with sensory changes in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve as opposed to motor symptoms and muscle atrophy.

We present a case of trigeminal motor neuropathy presenting as PHA. Progressive hemifacial atrophy is a rare, slowly progressive disease characterized by unilateral atrophy of the skin, subcutis, muscle, and bony structures of the face. Onset usually is during childhood, though later onset has been reported.10 The pathogenesis of PHA is not well understood, though trauma, infection, immune-mediated causes, sympathetic dysfunction, and metabolic dysfunction have been proposed.11 Diagnosis of PHA typically is based on clinical presentation, but histology and imaging are useful. In contrast to trigeminal motor neuropathy, MRI findings in PHA demonstrate involvement of the skin.12

Differentiation between PHA and trigeminal motor neuropathy is important because treatment differs. Treatment of trigeminal motor neuropathy depends on the etiology and may include removal of underlying neoplasms, while treatment of PHA depends on disease activity. The initial goal when treating PHA is to improve symptoms and slow disease progression; immunosuppressants may be considered. Facial reconstruction is an option when PHA is stable.

In this case, the features differentiating trigeminal motor neuropathy from PHA include age of onset and MRI as well as clinical findings of muscle atrophy limited to the distribution of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve. Although PHA is a rare disorder, this case demonstrates the importance of including trigeminal motor neuropathy in the differential diagnosis.

To the Editor:

Trigeminal motor neuropathy is a rare condition presenting with muscle weakness and atrophy in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve without sensory changes. We present a challenging case with clinical features that mimic progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA), a disease characterized by slowly progressive, unilateral facial atrophy that can be accompanied by inflammation and sclerosis as early features.

A 55-year-old man presented with right-sided ptosis and progressive right-sided facial atrophy of 4 years’ duration. A clinical diagnosis of PHA was made by the rheumatology department, and the patient was referred to the dermatology department for further evaluation. Examination at presentation revealed right-sided subcutaneous atrophy of the cheek, temple, and forehead extending to the scalp with absence of sclerosis, pigmentary alteration, or typical linear morphea lesions (Figures 1 and 2). The patient had no sensory changes in the affected area.

Workup by the dermatology department included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the face and scalp, which demonstrated denervation muscle atrophy exclusively in the distribution of the third branch of the right trigeminal nerve, including severe atrophy of the right temporalis and masseter muscles and moderate atrophy of the pterygoid muscles. No signs of inflammation, fibrosis, or atrophy of the skin or subcutaneous fat were found, ruling out a diagnosis of PHA.

The patient was referred to the neurology department where he was found to have a normal neurologic examination with the exception of right-sided ptosis and temporalis and masseter muscle atrophy. Notably, the patient had normal sensation in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve and normal strength of the masseter and temporalis muscles.

An extensive workup by the neurology department was completed, including magnetic resonance angiography, eyeblink testing, and testing for causes of neuropathies (eg, infectious, autoimmune, vitamin deficiencies, toxin related). Of note, magnetic resonance angiography showed no abnormalities within the cavernous sinus or trigeminal cave but showed potential vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, which was believed to be an incidental finding. The remainder of the workup was unremarkable. Based on muscle denervation atrophy in the distribution of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve in the absence of sensory symptoms or deficits, the patient’s presentation was consistent with trigeminal motor neuropathy.

In reported cases, the pathogenesis of trigeminal motor neuropathy is attributed to tumors, trauma, stroke, viral infection, and autoimmune reaction.1-6 In other reported cases the cause is unknown,6-8 as was the case in our patient. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed potential vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, which has been previously reported to cause trigeminal neuropathy.9 However, patients with trigeminal neuropathy presented with sensory changes in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve as opposed to motor symptoms and muscle atrophy.

We present a case of trigeminal motor neuropathy presenting as PHA. Progressive hemifacial atrophy is a rare, slowly progressive disease characterized by unilateral atrophy of the skin, subcutis, muscle, and bony structures of the face. Onset usually is during childhood, though later onset has been reported.10 The pathogenesis of PHA is not well understood, though trauma, infection, immune-mediated causes, sympathetic dysfunction, and metabolic dysfunction have been proposed.11 Diagnosis of PHA typically is based on clinical presentation, but histology and imaging are useful. In contrast to trigeminal motor neuropathy, MRI findings in PHA demonstrate involvement of the skin.12

Differentiation between PHA and trigeminal motor neuropathy is important because treatment differs. Treatment of trigeminal motor neuropathy depends on the etiology and may include removal of underlying neoplasms, while treatment of PHA depends on disease activity. The initial goal when treating PHA is to improve symptoms and slow disease progression; immunosuppressants may be considered. Facial reconstruction is an option when PHA is stable.

In this case, the features differentiating trigeminal motor neuropathy from PHA include age of onset and MRI as well as clinical findings of muscle atrophy limited to the distribution of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve. Although PHA is a rare disorder, this case demonstrates the importance of including trigeminal motor neuropathy in the differential diagnosis.

- Beydoun SR. Unilateral trigeminal motor neuropathy as a presenting feature of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:1136-1137.

- Kang YK, Lee EH, Hwang M. Pure trigeminal motor neuropathy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:995-998.

- Kim DH, Kim JK, Kang JY. Pure motor trigeminal neuropathy in a woman with tegmental pontine infarction. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1792-1794.

- Ko KF, Chan KL. A case of isolated pure trigeminal motor neuropathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1995;97:199-200.

- Park KS, Chung JM, Jeon BS, et al. Unilateral trigeminal mandibular motor neuropathy caused by tumor in the foramen ovale. J Clin Neurol. 2006;2:194-197.

- Chia LG. Pure trigeminal motor neuropathy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296:609-610.

- Braun JS, Hahn K, Bauknecht HC, et al. Progressive facial asymmetry due to trigeminal motor neuropathy. Eur Neurol. 2006;55:96-98.

- Chiba M, Echigo S. Unilateral atrophy of the masticatory muscles and mandibular ramus due to pure trigeminal motor neuropathy: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:E30-E34.

- Jannetta PJ, Robbins LJ. Trigeminal neuropathy—new observations. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:347-351.

- Stone J. Parry-Romberg syndrome: a global survey of 205 patients using the Internet. Neurology. 2003;61:674-676.

- El-Kehdy J, Abbas O, Rubeiz N. A review of Parry-Romberg syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:769-784.

- Taylor HM, Robinson R, Cox T. Progressive facial hemiatrophy: MRI appearances. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:484-486.

- Beydoun SR. Unilateral trigeminal motor neuropathy as a presenting feature of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:1136-1137.

- Kang YK, Lee EH, Hwang M. Pure trigeminal motor neuropathy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:995-998.

- Kim DH, Kim JK, Kang JY. Pure motor trigeminal neuropathy in a woman with tegmental pontine infarction. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1792-1794.

- Ko KF, Chan KL. A case of isolated pure trigeminal motor neuropathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1995;97:199-200.

- Park KS, Chung JM, Jeon BS, et al. Unilateral trigeminal mandibular motor neuropathy caused by tumor in the foramen ovale. J Clin Neurol. 2006;2:194-197.

- Chia LG. Pure trigeminal motor neuropathy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296:609-610.

- Braun JS, Hahn K, Bauknecht HC, et al. Progressive facial asymmetry due to trigeminal motor neuropathy. Eur Neurol. 2006;55:96-98.

- Chiba M, Echigo S. Unilateral atrophy of the masticatory muscles and mandibular ramus due to pure trigeminal motor neuropathy: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:E30-E34.

- Jannetta PJ, Robbins LJ. Trigeminal neuropathy—new observations. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:347-351.

- Stone J. Parry-Romberg syndrome: a global survey of 205 patients using the Internet. Neurology. 2003;61:674-676.

- El-Kehdy J, Abbas O, Rubeiz N. A review of Parry-Romberg syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:769-784.

- Taylor HM, Robinson R, Cox T. Progressive facial hemiatrophy: MRI appearances. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:484-486.

Practice Points

- The differential diagnosis of progressive hemifacial atrophy includes disorders of the trigeminal nerve.

- Trigeminal motor neuropathy presents with muscle weakness and atrophy without involvement of the skin, subcutis, or bone.