User login

Margin Size for Unique Skin Tumors Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Survey of Practice Patterns

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is most commonly used for the surgical management of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in high-risk locations. The ability for 100% margin evaluation with MMS also has shown lower recurrence rates compared with wide local excision for less common and/or more aggressive tumors. However, there is a lack of standardization on initial and subsequent margin size when treating these less common skin tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), and sebaceous carcinoma.

Because Mohs surgeons must balance normal tissue preservation with the importance of tumor clearance in the context of comprehensive margin control, we aimed to assess the practice patterns of Mohs surgeons regarding margin size for these unique tumors. The average margin size for each Mohs layer has been reported to be 1 to 3 mm for BCC compared with 3 to 6 mm or larger for other skin cancers, such as melanoma in situ (MIS).1-3 We hypothesized that the initial margin size would vary among surgeons and likely be greater for more aggressive and rarer malignancies as well as for lesions on the trunk and extremities.

Methods

A descriptive survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). Survey participants and their responses were anonymous. Demographic information on survey participants was collected in addition to initial and subsequent MMS margin size for DFSP, AFX, MIS, invasive melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), poorly differentiated SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, leiomyosarcoma, and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Survey participants were asked to choose from a range of margin sizes: 1 to 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm, 7 to 9 mm, and greater than 9 mm. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) institutional review board.

Results

Eighty-seven respondents from the ACMS listserve completed the survey (response rate <10%). Of these, 58 respondents (66.7%) reported practicing for more than 5 years, and 58 (66.7%) were male. Practice setting was primarily private/community (71.3% [62/87]), and survey respondents were located across the United States. More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the head and neck in their respective practices: DFSP (80.9% [55/68]), AFX (95.6% [65/68]), MIS (67.7% [46/68]), sebaceous carcinoma (92.7% [63/68]), MAC (83.8% [57/68]), poorly differentiated SCC (97.1% [66/68]), and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (51.5% [35/68]). More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the trunk and extremities: DFSP (90.3% [47/52]), AFX (86.4% [45/52]), MIS (55.8% [29/52]), sebaceous carcinoma (80.8% [42/52]), MAC (73.1% [38/52]), poorly differentiated SCC (94.2% [49/52]), and extramammary Paget disease (53.9% [28/52]). Invasive melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma were overall less commonly treated.

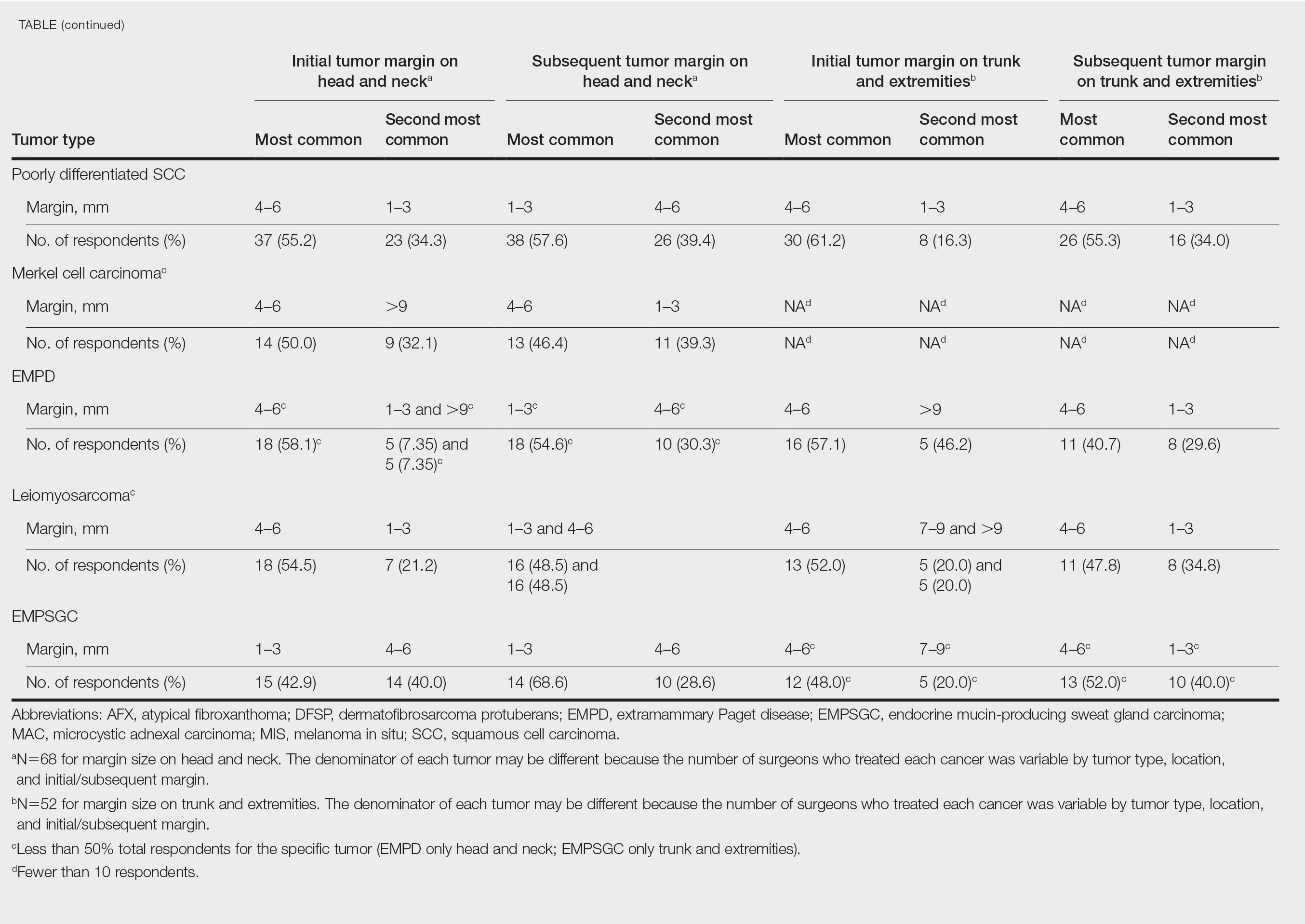

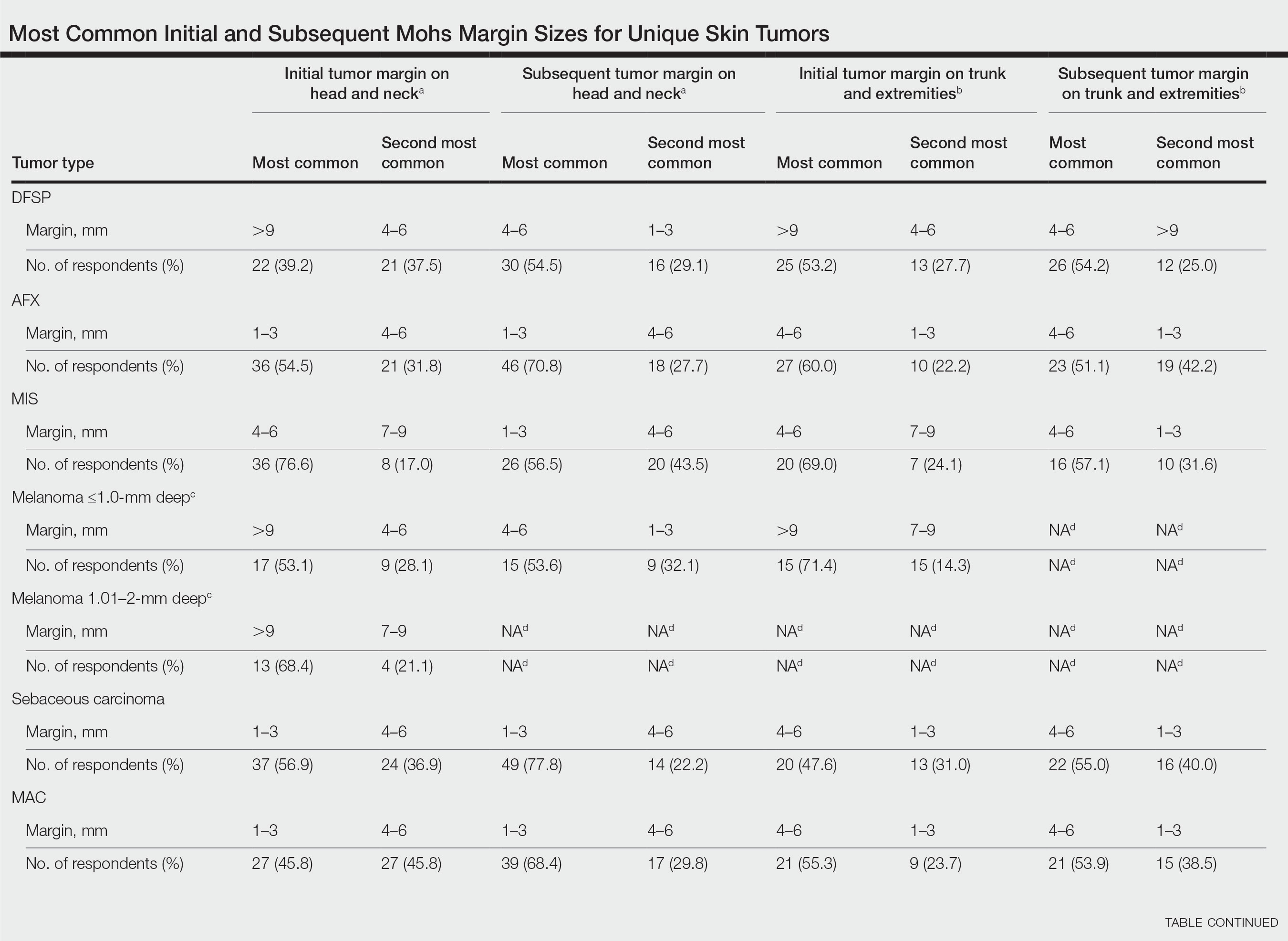

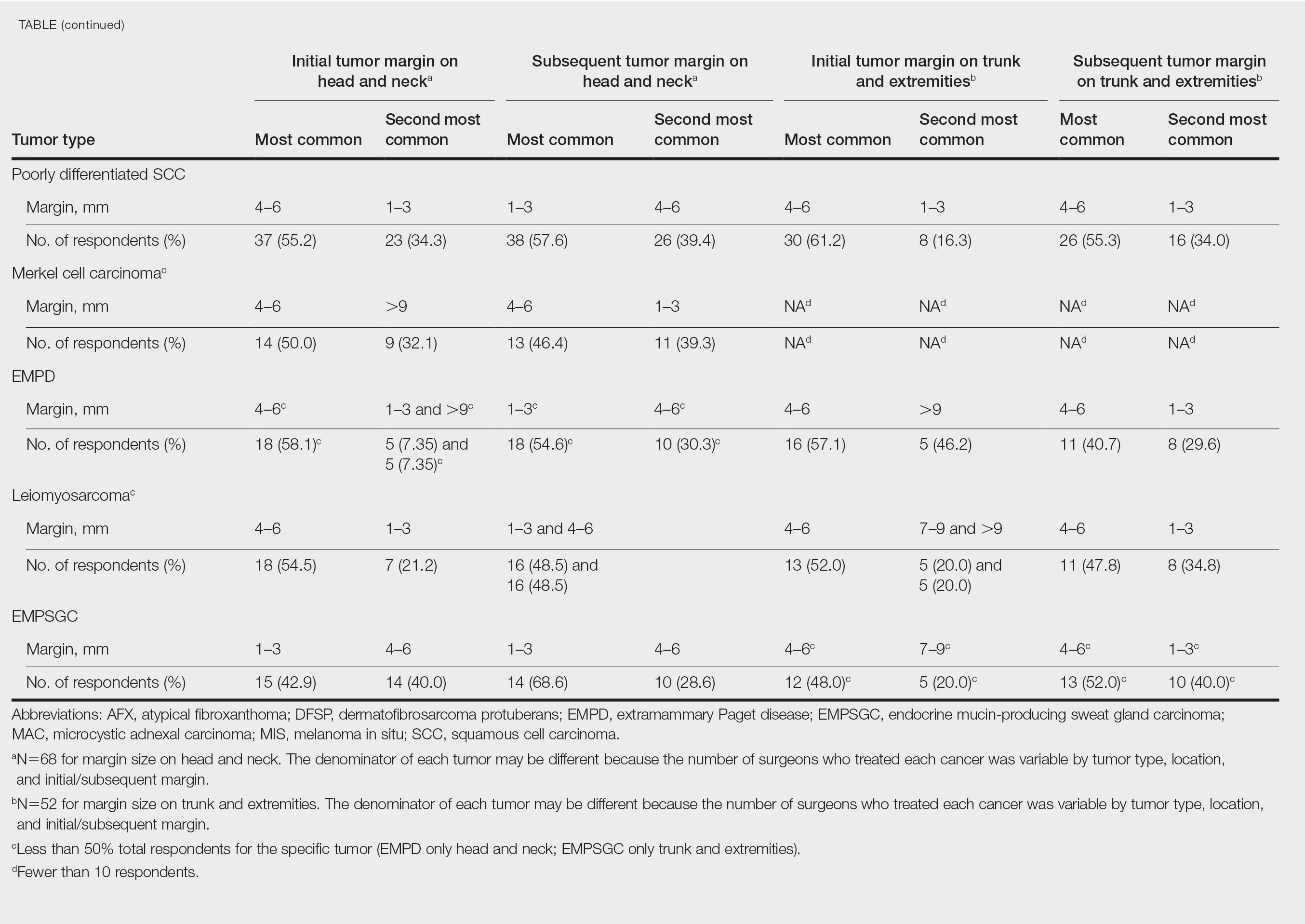

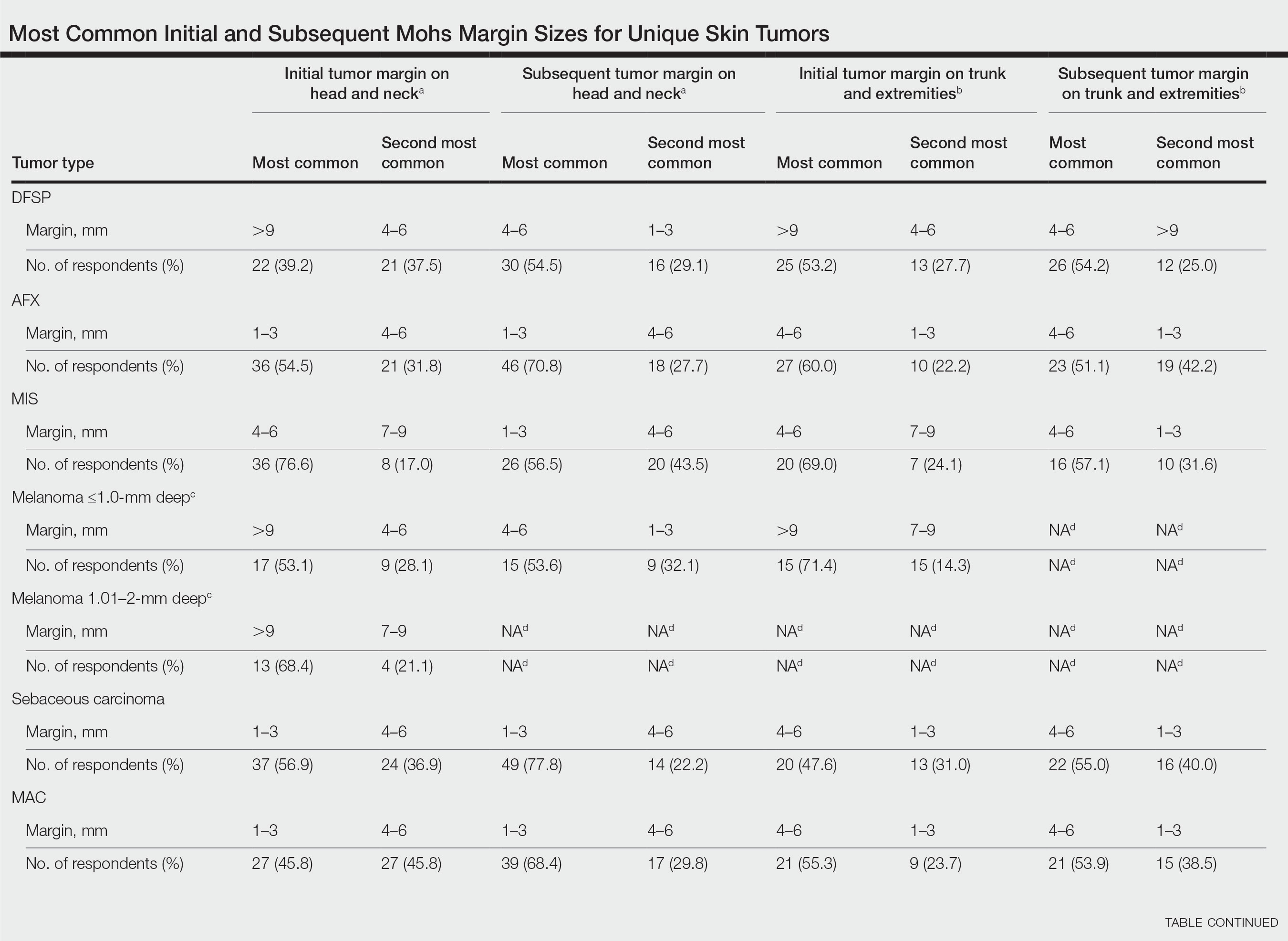

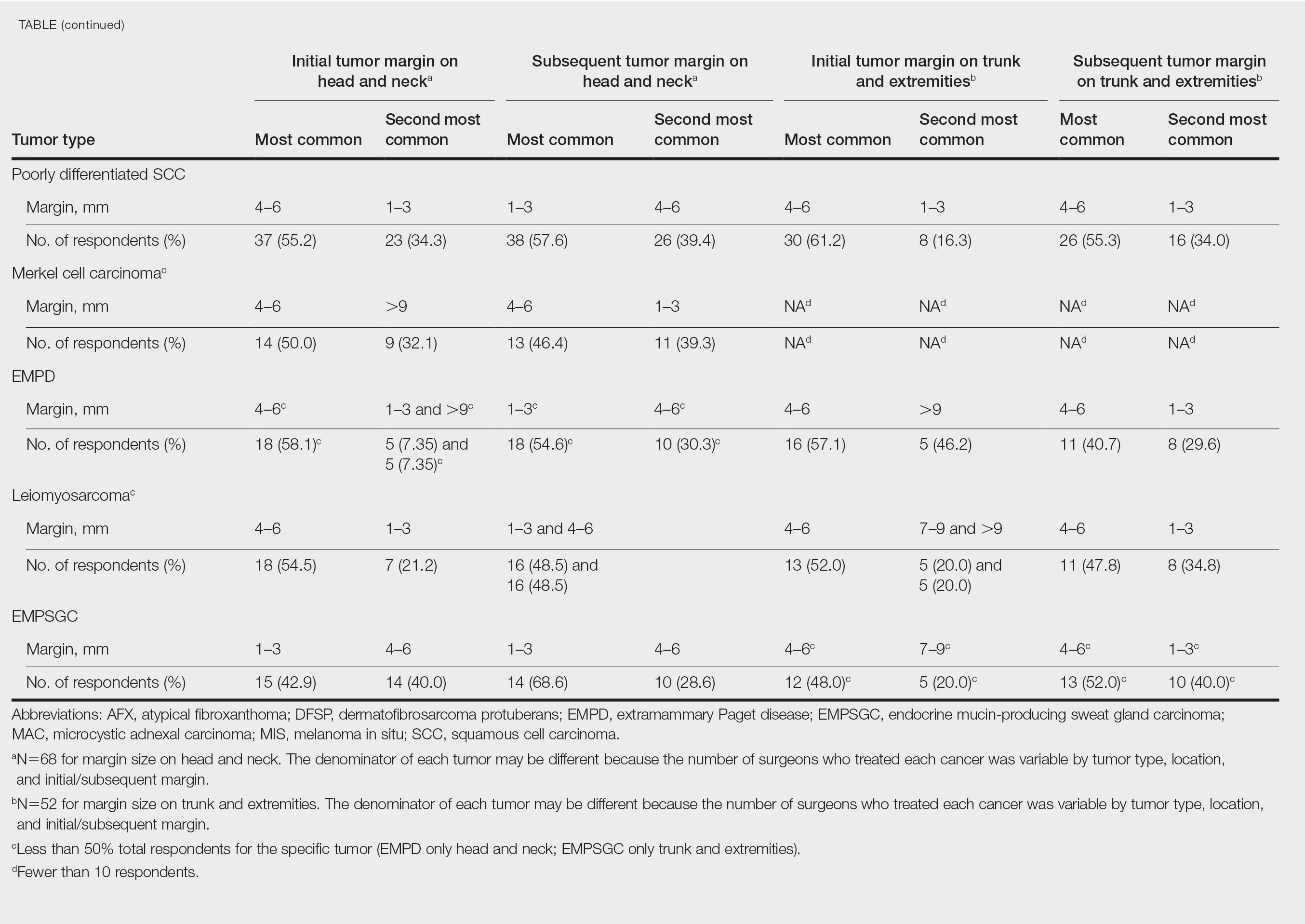

In general, respondent Mohs surgeons were more likely to take larger initial and subsequent margins for tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck (Table). In addition, initial margin size often was larger than the 1- to 3-mm margin commonly used in Mohs surgery for BCCs and less aggressive SCCs (Table). A larger initial margin size (>9 mm) and subsequent margin size (4–6 mm) was more commonly reported for certain tumors known to be more aggressive and/or have extensive subclinical extension, such as DFSP and invasive melanoma. Of note, most respondents performed 4- to 6-mm margins (37/67 [55.2%]) for poorly differentiated SCC. Overall, there was a high range of margin size variability among Mohs surgeons for these unique and/or more aggressive skin tumors.

Comment

Given that no guidelines exist on margins with MMS for less commonly treated skin tumors, this study helps give Mohs surgeons perspective on current practice patterns for both initial and subsequent Mohs margin sizes. High margin-size variability among Mohs surgeons is expected, as surgeons also need to account for high-risk features of the tumor or specific locations where tissue sparing is critical. Overall, Mohs surgeons are more likely to take larger initial margins for these less common skin tumors compared with BCCs or SCCs. Initial margin size was consistently larger on the trunk and extremities where tissue sparing often is less critical.

Our survey was limited by a small sample size and incomplete response of the ACMS membership. In addition, most respondents practiced in a private/community setting, which may have led to bias, as academic centers may manage rare malignancies more commonly and/or have increased access to immunostains and multispecialty care. Future registries for rare skin malignancies will hopefully be developed that will allow for further consensus on standardized margins. Additional studies on the average number of stages required to clear these less common tumors also are warranted.

- Muller FM, Dawe RS, Moseley H, et al. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue‐sparing outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1349-1354.

- van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Ellison PM, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:767-774.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is most commonly used for the surgical management of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in high-risk locations. The ability for 100% margin evaluation with MMS also has shown lower recurrence rates compared with wide local excision for less common and/or more aggressive tumors. However, there is a lack of standardization on initial and subsequent margin size when treating these less common skin tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), and sebaceous carcinoma.

Because Mohs surgeons must balance normal tissue preservation with the importance of tumor clearance in the context of comprehensive margin control, we aimed to assess the practice patterns of Mohs surgeons regarding margin size for these unique tumors. The average margin size for each Mohs layer has been reported to be 1 to 3 mm for BCC compared with 3 to 6 mm or larger for other skin cancers, such as melanoma in situ (MIS).1-3 We hypothesized that the initial margin size would vary among surgeons and likely be greater for more aggressive and rarer malignancies as well as for lesions on the trunk and extremities.

Methods

A descriptive survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). Survey participants and their responses were anonymous. Demographic information on survey participants was collected in addition to initial and subsequent MMS margin size for DFSP, AFX, MIS, invasive melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), poorly differentiated SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, leiomyosarcoma, and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Survey participants were asked to choose from a range of margin sizes: 1 to 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm, 7 to 9 mm, and greater than 9 mm. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) institutional review board.

Results

Eighty-seven respondents from the ACMS listserve completed the survey (response rate <10%). Of these, 58 respondents (66.7%) reported practicing for more than 5 years, and 58 (66.7%) were male. Practice setting was primarily private/community (71.3% [62/87]), and survey respondents were located across the United States. More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the head and neck in their respective practices: DFSP (80.9% [55/68]), AFX (95.6% [65/68]), MIS (67.7% [46/68]), sebaceous carcinoma (92.7% [63/68]), MAC (83.8% [57/68]), poorly differentiated SCC (97.1% [66/68]), and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (51.5% [35/68]). More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the trunk and extremities: DFSP (90.3% [47/52]), AFX (86.4% [45/52]), MIS (55.8% [29/52]), sebaceous carcinoma (80.8% [42/52]), MAC (73.1% [38/52]), poorly differentiated SCC (94.2% [49/52]), and extramammary Paget disease (53.9% [28/52]). Invasive melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma were overall less commonly treated.

In general, respondent Mohs surgeons were more likely to take larger initial and subsequent margins for tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck (Table). In addition, initial margin size often was larger than the 1- to 3-mm margin commonly used in Mohs surgery for BCCs and less aggressive SCCs (Table). A larger initial margin size (>9 mm) and subsequent margin size (4–6 mm) was more commonly reported for certain tumors known to be more aggressive and/or have extensive subclinical extension, such as DFSP and invasive melanoma. Of note, most respondents performed 4- to 6-mm margins (37/67 [55.2%]) for poorly differentiated SCC. Overall, there was a high range of margin size variability among Mohs surgeons for these unique and/or more aggressive skin tumors.

Comment

Given that no guidelines exist on margins with MMS for less commonly treated skin tumors, this study helps give Mohs surgeons perspective on current practice patterns for both initial and subsequent Mohs margin sizes. High margin-size variability among Mohs surgeons is expected, as surgeons also need to account for high-risk features of the tumor or specific locations where tissue sparing is critical. Overall, Mohs surgeons are more likely to take larger initial margins for these less common skin tumors compared with BCCs or SCCs. Initial margin size was consistently larger on the trunk and extremities where tissue sparing often is less critical.

Our survey was limited by a small sample size and incomplete response of the ACMS membership. In addition, most respondents practiced in a private/community setting, which may have led to bias, as academic centers may manage rare malignancies more commonly and/or have increased access to immunostains and multispecialty care. Future registries for rare skin malignancies will hopefully be developed that will allow for further consensus on standardized margins. Additional studies on the average number of stages required to clear these less common tumors also are warranted.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is most commonly used for the surgical management of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in high-risk locations. The ability for 100% margin evaluation with MMS also has shown lower recurrence rates compared with wide local excision for less common and/or more aggressive tumors. However, there is a lack of standardization on initial and subsequent margin size when treating these less common skin tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), and sebaceous carcinoma.

Because Mohs surgeons must balance normal tissue preservation with the importance of tumor clearance in the context of comprehensive margin control, we aimed to assess the practice patterns of Mohs surgeons regarding margin size for these unique tumors. The average margin size for each Mohs layer has been reported to be 1 to 3 mm for BCC compared with 3 to 6 mm or larger for other skin cancers, such as melanoma in situ (MIS).1-3 We hypothesized that the initial margin size would vary among surgeons and likely be greater for more aggressive and rarer malignancies as well as for lesions on the trunk and extremities.

Methods

A descriptive survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). Survey participants and their responses were anonymous. Demographic information on survey participants was collected in addition to initial and subsequent MMS margin size for DFSP, AFX, MIS, invasive melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), poorly differentiated SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, leiomyosarcoma, and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Survey participants were asked to choose from a range of margin sizes: 1 to 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm, 7 to 9 mm, and greater than 9 mm. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) institutional review board.

Results

Eighty-seven respondents from the ACMS listserve completed the survey (response rate <10%). Of these, 58 respondents (66.7%) reported practicing for more than 5 years, and 58 (66.7%) were male. Practice setting was primarily private/community (71.3% [62/87]), and survey respondents were located across the United States. More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the head and neck in their respective practices: DFSP (80.9% [55/68]), AFX (95.6% [65/68]), MIS (67.7% [46/68]), sebaceous carcinoma (92.7% [63/68]), MAC (83.8% [57/68]), poorly differentiated SCC (97.1% [66/68]), and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (51.5% [35/68]). More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the trunk and extremities: DFSP (90.3% [47/52]), AFX (86.4% [45/52]), MIS (55.8% [29/52]), sebaceous carcinoma (80.8% [42/52]), MAC (73.1% [38/52]), poorly differentiated SCC (94.2% [49/52]), and extramammary Paget disease (53.9% [28/52]). Invasive melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma were overall less commonly treated.

In general, respondent Mohs surgeons were more likely to take larger initial and subsequent margins for tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck (Table). In addition, initial margin size often was larger than the 1- to 3-mm margin commonly used in Mohs surgery for BCCs and less aggressive SCCs (Table). A larger initial margin size (>9 mm) and subsequent margin size (4–6 mm) was more commonly reported for certain tumors known to be more aggressive and/or have extensive subclinical extension, such as DFSP and invasive melanoma. Of note, most respondents performed 4- to 6-mm margins (37/67 [55.2%]) for poorly differentiated SCC. Overall, there was a high range of margin size variability among Mohs surgeons for these unique and/or more aggressive skin tumors.

Comment

Given that no guidelines exist on margins with MMS for less commonly treated skin tumors, this study helps give Mohs surgeons perspective on current practice patterns for both initial and subsequent Mohs margin sizes. High margin-size variability among Mohs surgeons is expected, as surgeons also need to account for high-risk features of the tumor or specific locations where tissue sparing is critical. Overall, Mohs surgeons are more likely to take larger initial margins for these less common skin tumors compared with BCCs or SCCs. Initial margin size was consistently larger on the trunk and extremities where tissue sparing often is less critical.

Our survey was limited by a small sample size and incomplete response of the ACMS membership. In addition, most respondents practiced in a private/community setting, which may have led to bias, as academic centers may manage rare malignancies more commonly and/or have increased access to immunostains and multispecialty care. Future registries for rare skin malignancies will hopefully be developed that will allow for further consensus on standardized margins. Additional studies on the average number of stages required to clear these less common tumors also are warranted.

- Muller FM, Dawe RS, Moseley H, et al. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue‐sparing outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1349-1354.

- van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Ellison PM, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:767-774.

- Muller FM, Dawe RS, Moseley H, et al. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue‐sparing outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1349-1354.

- van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Ellison PM, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:767-774.

Practice Points

- It is common for initial margin size for uncommon skin tumors to be larger than the 1 to 3 mm commonly used in Mohs surgery for basal cell carcinomas and less aggressive squamous cell carcinomas.

- Mohs surgeons commonly take larger starting and subsequent margins for uncommon skin tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck.

Cartilage Sutures for a Large Nasal Defect

Practice Gap

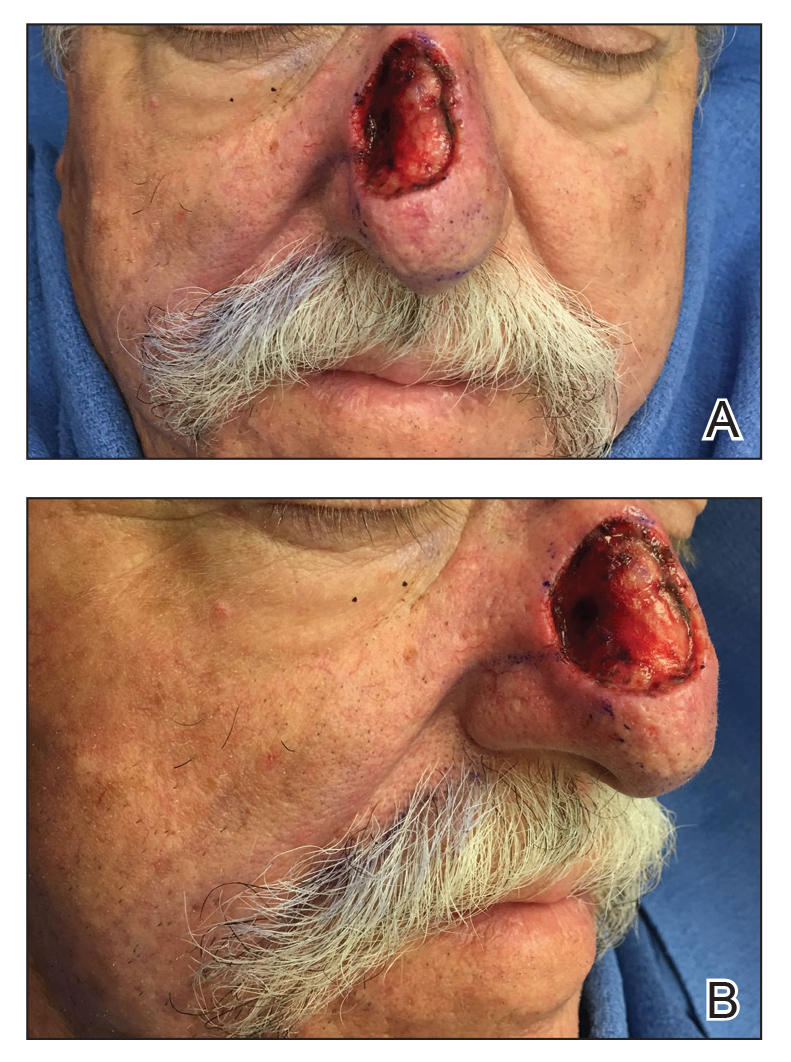

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

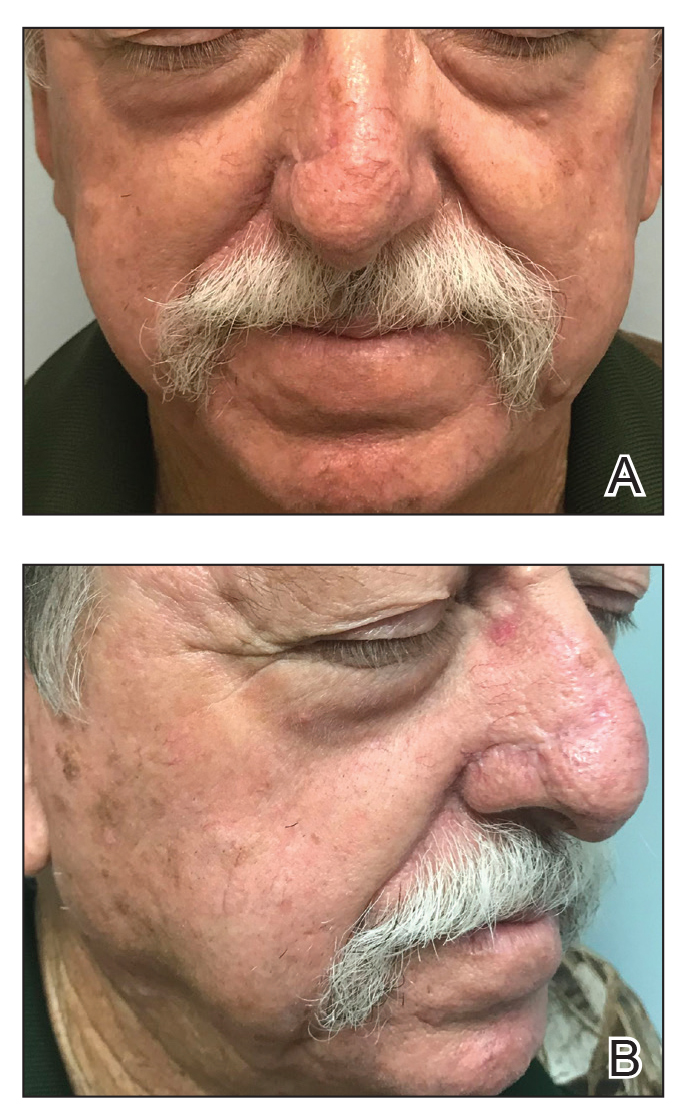

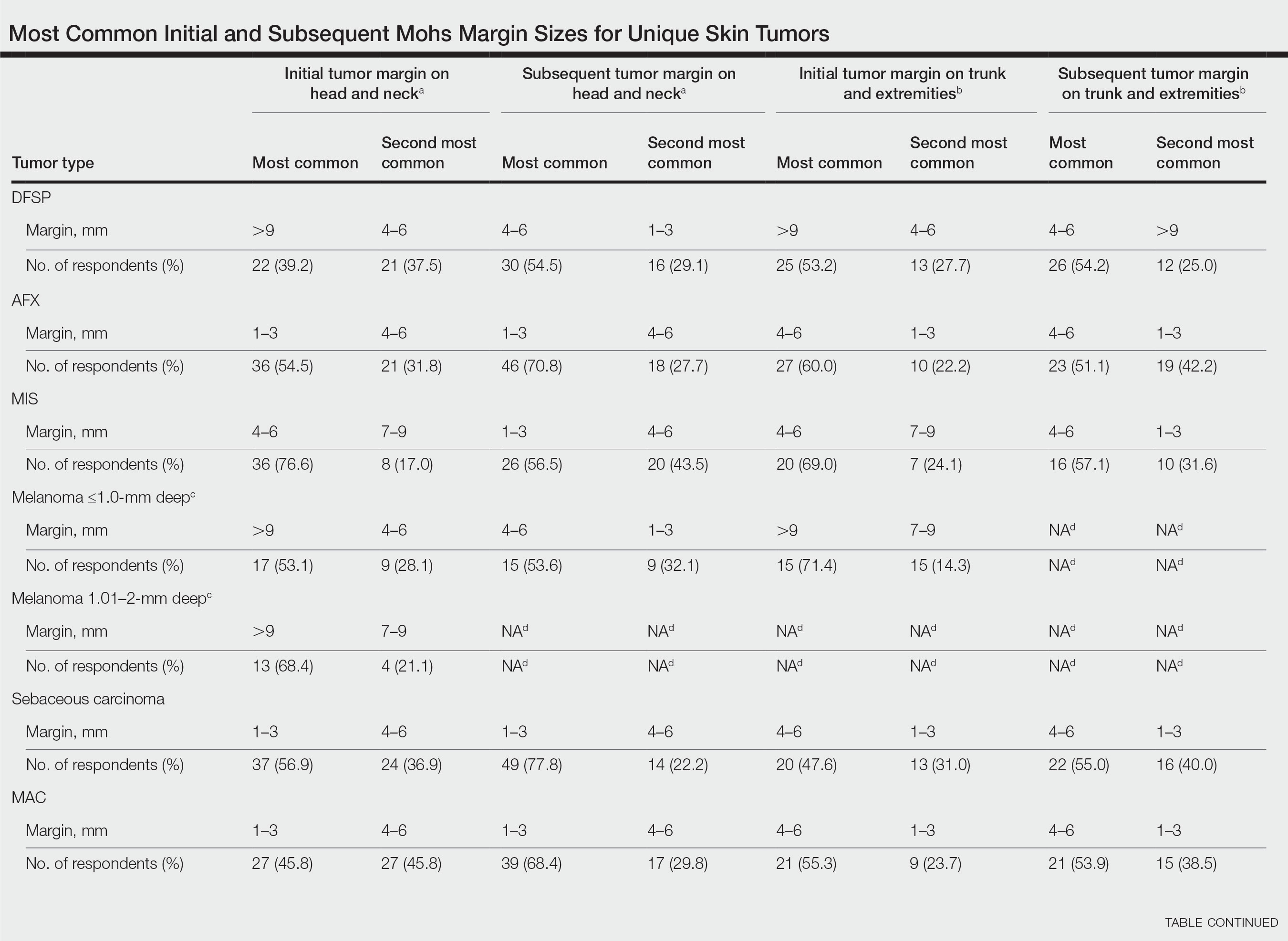

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Wound Closure Tips

What does your patient need to know preoperatively?

Patients should be educated on all aspects of the procedure as well as the expected postoperative course of healing. Manage patient expectations in advance to minimize any surprises for everyone involved. Swelling and bruising are not uncommon in the immediate postoperative phase, and for surgery near the eyes, both may be worse, making it prudent for patients to schedule any procedures after big events or vacations.

The sutured wound initially can appear lumpy, bumpy, and pink, and it may take potentially 3 to 6 months, or even longer, for the scar to fully mature depending on the type of repair performed. Sutured wounds require activity restrictions, which is especially important for young active patients as well as patients who may have labor-intensive occupations. I often recommend 1 to 2 weeks before resuming most forms of strenuous exercise and/or physical labor. Skin grafts may require even longer limitations. Although the overall risk for infection is low (approximately 1%), patients should be instructed to monitor for purulent drainage, fever, and worsening pain and redness, and to inform the dermatologist immediately of any concerning symptoms.

What is your go-to approach for wound closure?

My motto is: Simplest is often best. For the patient who prioritizes returning to full activity as soon as possible, the wound may be able to heal by secondary intention in select anatomic locations, and this approach can often yield excellent cosmetic results. If wound closure with sutures is indicated, then I use the following treatment algorithm:

- Primary closure is used if I can close a wound in a linear fashion without distorting free margins, especially if I can hide the lines within cosmetic subunit junctions and/or relaxed skin tension lines.

- Local flap is used for defects when repair in a linear fashion is not always ideal for various reasons. Recruit local skin with various flap options for the best color and texture match. This approach may be more involved but often provides the best long-term cosmetic outcome; however, it usually results in a longer recovery time and may even require staged procedures.

- Graft usually is our last preferred option because it may appear as a sewn-in patch; however, in certain anatomic locations and in the right patient, skin grafts also can yield acceptable cosmetic results.

I give trainees the following surgical technique pearls:

- Use buried vertical mattress sutures to achieve eversion of wound edges with deep sutures

- Dermal pulley as well as epidermal pulley sutures can offset tension wonderfully, especially in high-tension areas such as the back and scalp

- Placement of a running subcuticular suture in place of epidermal stitches on the trunk and extremities can prevent track marks

How do you keep patients compliant with wound care instructions?

Two keys to high patient compliance with wound care are making instructions as simple as possible and providing detailed written instructions. We instruct patients to keep the pressure dressing in place for 48 hours. Once removed, we recommend patients clean the wound with regular soap and water daily, followed by application of petrolatum ointment. For hard-to-reach areas or on non-hair-bearing skin, my surgical assistants apply adhesive strips over the sutures, eliminating the need for daily wound care. For full-thickness skin grafts, we commonly place a bolster pressure dressing that stays in place until the patient returns to our clinic for a postoperative visit. We provide every patient with detailed written instructions as a patient handout that is specific to the type of wound closure performed.

What do you do if the patient refuses your recommendation for wound closure?

It is important to explain all wound closure options to the patient and the risks and benefits of each. I always show patients the proposed plan using a mirror and/or textbook images so that they can better understand the process. In rare cases when the patient refuses the preferred method of closure, we ensure that he/she understands the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed procedure and why the recommendation was made. If the patient still refuses, we document our lengthy discussion in the medical record. For patients who refuse our recommended plan of sutures and opt to heal by secondary intention, we will see these patients almost weekly to ensure appropriate healing as well as provide further recommendations such as a delayed repair if there is any evidence of functional impairment and/or notable cosmetic implications. A patient completely refusing a planned repair is rare.

More commonly, patients request a "simpler" repair, even if the cosmetic outcome may be suboptimal. For example, some elderly patients with large nasal defects do not want to undergo a staged flap, even though it would give a superior cosmetic result. Instead, we do the best we can with a skin graft or single-stage flap.

What resources do you provide to patients for wound care instructions?

We recommend that physicians prepare comprehensive handouts on wound care instructions that address both short-term and long-term expectations, provide instructions regarding follow-up, and encourage good sun protection behaviors. Some physicians post videos demonstrating proper wound care on their websites, which may be another useful tool.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Daniel Condie, MD (Dallas, Texas), for his contributions.

Suggested Readings

Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part I. cutting tissue: incising, excising, and undermining. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:377-387.

Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402.

What does your patient need to know preoperatively?

Patients should be educated on all aspects of the procedure as well as the expected postoperative course of healing. Manage patient expectations in advance to minimize any surprises for everyone involved. Swelling and bruising are not uncommon in the immediate postoperative phase, and for surgery near the eyes, both may be worse, making it prudent for patients to schedule any procedures after big events or vacations.

The sutured wound initially can appear lumpy, bumpy, and pink, and it may take potentially 3 to 6 months, or even longer, for the scar to fully mature depending on the type of repair performed. Sutured wounds require activity restrictions, which is especially important for young active patients as well as patients who may have labor-intensive occupations. I often recommend 1 to 2 weeks before resuming most forms of strenuous exercise and/or physical labor. Skin grafts may require even longer limitations. Although the overall risk for infection is low (approximately 1%), patients should be instructed to monitor for purulent drainage, fever, and worsening pain and redness, and to inform the dermatologist immediately of any concerning symptoms.

What is your go-to approach for wound closure?

My motto is: Simplest is often best. For the patient who prioritizes returning to full activity as soon as possible, the wound may be able to heal by secondary intention in select anatomic locations, and this approach can often yield excellent cosmetic results. If wound closure with sutures is indicated, then I use the following treatment algorithm:

- Primary closure is used if I can close a wound in a linear fashion without distorting free margins, especially if I can hide the lines within cosmetic subunit junctions and/or relaxed skin tension lines.

- Local flap is used for defects when repair in a linear fashion is not always ideal for various reasons. Recruit local skin with various flap options for the best color and texture match. This approach may be more involved but often provides the best long-term cosmetic outcome; however, it usually results in a longer recovery time and may even require staged procedures.

- Graft usually is our last preferred option because it may appear as a sewn-in patch; however, in certain anatomic locations and in the right patient, skin grafts also can yield acceptable cosmetic results.

I give trainees the following surgical technique pearls:

- Use buried vertical mattress sutures to achieve eversion of wound edges with deep sutures

- Dermal pulley as well as epidermal pulley sutures can offset tension wonderfully, especially in high-tension areas such as the back and scalp

- Placement of a running subcuticular suture in place of epidermal stitches on the trunk and extremities can prevent track marks

How do you keep patients compliant with wound care instructions?

Two keys to high patient compliance with wound care are making instructions as simple as possible and providing detailed written instructions. We instruct patients to keep the pressure dressing in place for 48 hours. Once removed, we recommend patients clean the wound with regular soap and water daily, followed by application of petrolatum ointment. For hard-to-reach areas or on non-hair-bearing skin, my surgical assistants apply adhesive strips over the sutures, eliminating the need for daily wound care. For full-thickness skin grafts, we commonly place a bolster pressure dressing that stays in place until the patient returns to our clinic for a postoperative visit. We provide every patient with detailed written instructions as a patient handout that is specific to the type of wound closure performed.

What do you do if the patient refuses your recommendation for wound closure?

It is important to explain all wound closure options to the patient and the risks and benefits of each. I always show patients the proposed plan using a mirror and/or textbook images so that they can better understand the process. In rare cases when the patient refuses the preferred method of closure, we ensure that he/she understands the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed procedure and why the recommendation was made. If the patient still refuses, we document our lengthy discussion in the medical record. For patients who refuse our recommended plan of sutures and opt to heal by secondary intention, we will see these patients almost weekly to ensure appropriate healing as well as provide further recommendations such as a delayed repair if there is any evidence of functional impairment and/or notable cosmetic implications. A patient completely refusing a planned repair is rare.

More commonly, patients request a "simpler" repair, even if the cosmetic outcome may be suboptimal. For example, some elderly patients with large nasal defects do not want to undergo a staged flap, even though it would give a superior cosmetic result. Instead, we do the best we can with a skin graft or single-stage flap.

What resources do you provide to patients for wound care instructions?

We recommend that physicians prepare comprehensive handouts on wound care instructions that address both short-term and long-term expectations, provide instructions regarding follow-up, and encourage good sun protection behaviors. Some physicians post videos demonstrating proper wound care on their websites, which may be another useful tool.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Daniel Condie, MD (Dallas, Texas), for his contributions.

Suggested Readings

Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part I. cutting tissue: incising, excising, and undermining. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:377-387.

Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402.

What does your patient need to know preoperatively?

Patients should be educated on all aspects of the procedure as well as the expected postoperative course of healing. Manage patient expectations in advance to minimize any surprises for everyone involved. Swelling and bruising are not uncommon in the immediate postoperative phase, and for surgery near the eyes, both may be worse, making it prudent for patients to schedule any procedures after big events or vacations.

The sutured wound initially can appear lumpy, bumpy, and pink, and it may take potentially 3 to 6 months, or even longer, for the scar to fully mature depending on the type of repair performed. Sutured wounds require activity restrictions, which is especially important for young active patients as well as patients who may have labor-intensive occupations. I often recommend 1 to 2 weeks before resuming most forms of strenuous exercise and/or physical labor. Skin grafts may require even longer limitations. Although the overall risk for infection is low (approximately 1%), patients should be instructed to monitor for purulent drainage, fever, and worsening pain and redness, and to inform the dermatologist immediately of any concerning symptoms.

What is your go-to approach for wound closure?

My motto is: Simplest is often best. For the patient who prioritizes returning to full activity as soon as possible, the wound may be able to heal by secondary intention in select anatomic locations, and this approach can often yield excellent cosmetic results. If wound closure with sutures is indicated, then I use the following treatment algorithm:

- Primary closure is used if I can close a wound in a linear fashion without distorting free margins, especially if I can hide the lines within cosmetic subunit junctions and/or relaxed skin tension lines.

- Local flap is used for defects when repair in a linear fashion is not always ideal for various reasons. Recruit local skin with various flap options for the best color and texture match. This approach may be more involved but often provides the best long-term cosmetic outcome; however, it usually results in a longer recovery time and may even require staged procedures.

- Graft usually is our last preferred option because it may appear as a sewn-in patch; however, in certain anatomic locations and in the right patient, skin grafts also can yield acceptable cosmetic results.

I give trainees the following surgical technique pearls:

- Use buried vertical mattress sutures to achieve eversion of wound edges with deep sutures

- Dermal pulley as well as epidermal pulley sutures can offset tension wonderfully, especially in high-tension areas such as the back and scalp

- Placement of a running subcuticular suture in place of epidermal stitches on the trunk and extremities can prevent track marks

How do you keep patients compliant with wound care instructions?

Two keys to high patient compliance with wound care are making instructions as simple as possible and providing detailed written instructions. We instruct patients to keep the pressure dressing in place for 48 hours. Once removed, we recommend patients clean the wound with regular soap and water daily, followed by application of petrolatum ointment. For hard-to-reach areas or on non-hair-bearing skin, my surgical assistants apply adhesive strips over the sutures, eliminating the need for daily wound care. For full-thickness skin grafts, we commonly place a bolster pressure dressing that stays in place until the patient returns to our clinic for a postoperative visit. We provide every patient with detailed written instructions as a patient handout that is specific to the type of wound closure performed.

What do you do if the patient refuses your recommendation for wound closure?

It is important to explain all wound closure options to the patient and the risks and benefits of each. I always show patients the proposed plan using a mirror and/or textbook images so that they can better understand the process. In rare cases when the patient refuses the preferred method of closure, we ensure that he/she understands the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed procedure and why the recommendation was made. If the patient still refuses, we document our lengthy discussion in the medical record. For patients who refuse our recommended plan of sutures and opt to heal by secondary intention, we will see these patients almost weekly to ensure appropriate healing as well as provide further recommendations such as a delayed repair if there is any evidence of functional impairment and/or notable cosmetic implications. A patient completely refusing a planned repair is rare.

More commonly, patients request a "simpler" repair, even if the cosmetic outcome may be suboptimal. For example, some elderly patients with large nasal defects do not want to undergo a staged flap, even though it would give a superior cosmetic result. Instead, we do the best we can with a skin graft or single-stage flap.

What resources do you provide to patients for wound care instructions?

We recommend that physicians prepare comprehensive handouts on wound care instructions that address both short-term and long-term expectations, provide instructions regarding follow-up, and encourage good sun protection behaviors. Some physicians post videos demonstrating proper wound care on their websites, which may be another useful tool.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Daniel Condie, MD (Dallas, Texas), for his contributions.

Suggested Readings

Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part I. cutting tissue: incising, excising, and undermining. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:377-387.

Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402.