User login

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: What primary care physicians need to know

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating and fatal lung disease that generally affects older adults. It is characterized by a radiographic and histopathologic pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) that has no other known etiology.

Accurate diagnosis of IPF is crucial. We recommend early referral to a center specializing in interstitial lung disease to confirm the diagnosis, start appropriate therapy, advise the patient on prognosis and enrollment in disease registries and clinical trials, and determine candidacy for lung transplant.

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to encounter patients with IPF, whether because of a patient complaint or as an incidental finding on computed tomography. The goal of this article is to delineate the features of IPF so that it may be recognized early and thus expedite referral to a center with expertise in interstitial lung disease for a thorough evaluation and appropriate management.

WHAT IS IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS?

MORE COMMON THAN ONCE THOUGHT

The true incidence and prevalence of IPF are difficult to assess. IPF is generally considered a rare disease, but it is more common than once thought. In 2011, Raghu et al3 estimated the prevalence in Medicare beneficiaries to be 495 cases per 100,000. Based on this estimate and the current US population, up to 160,000 Americans could have IPF.4 Raghu et al also showed that IPF more often affects adults over age 65, which suggests that as the US population ages, the incidence of IPF may rise. Studies have also reported an increased incidence of IPF worldwide.5

Further, with the rising use of low-dose computed tomography to screen for lung cancer, more incidental cases of IPF will likely be found.6–8

Older data showed a lag from symptom onset to accurate diagnosis of 1 to 2 years.9 A more recent study found a lag in referral of patients with IPF to tertiary care centers, and this delay was associated with a higher rate of death independent of disease severity.10

TYPICALLY PROGRESSIVE, OFTEN FATAL

IPF is typically progressive and limited to the lungs, and it portends a poor prognosis. The median survival is commonly cited as 2 to 5 years from diagnosis, although this is based on older observations that may not reflect current best practice and newer therapies. More recent studies suggest higher survival rates if patients have preserved lung function.11

As the name indicates, the etiology of IPF is unknown, but studies have indicated genetic underpinnings in a notable proportion of cases.12 Regardless of the cause, the pathogenesis and progression of IPF are thought to be the result of an abnormal and persistent wound-repair response. The progressive deposition of scar tissue disrupts normal lung architecture and function, eventually causing clinical disease.13

SYMPTOMS AND KEY FEATURES

Patients with IPF typically present with the insidious onset of dyspnea on exertion, with or without chronic cough. Risk factors include male sex, increasing age, and a history of smoking. Patients with undiagnosed IPF who present with dyspnea and a history of smoking are often treated empirically for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Rales are a common finding on auscultation in IPF, and this can lead to an exhaustive cardiac evaluation and empiric treatment for heart failure. Digital clubbing is also relatively common.14 Hypoxemia with exertion is another common feature that also often correlates with disease severity and prognosis. Resting hypoxemia is more common in advanced disease.

On spirometry, patients with IPF typically demonstrate restrictive physiology, suggested by a normal or elevated ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 second to the forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) (> 70% predicted or above the lower limit of normal) combined with a lower than normal FVC. Restrictive physiology is definitively demonstrated by a decreased total lung capacity (< 80% predicted or below the lower limit of normal) on plethysmography. Impaired gas exchange, manifested by a decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) on pulmonary function testing, is also common. Because pulmonary perfusion is higher in the lung bases, where IPF is also predominant, the DLCO is often reduced to a greater extent than the FVC.

PROGNOSTIC INDICATORS

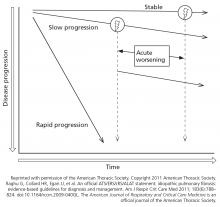

Clinicians typically view IPF as a relentless and progressive process, but its course is variable and can be uncertain in an individual patient (Figure 1).15,16 Nevertheless, over time, most patients have a decline in lung function leading to respiratory failure. Respiratory failure, often preceded by a subacute deterioration (over weeks to months) or an acute deterioration (< 4 weeks), is the most common cause of death, but comorbid diseases such as lung cancer, infection, and heart failure are also common causes of death in these patients.17,18

Predictors of mortality include worsening FVC, DLCO, symptoms, and physiologic impairment, manifested by a decline in the 6-minute walking test or worsening exertional hypoxemia.19–22 Other common comorbidities linked with impaired quality of life and poor prognosis include obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression.16,23 Retrospective studies suggest that most IPF patients die 2 to 5 years after symptom onset. With the lag from symptom onset to final diagnosis, the average life expectancy is as little as 2 years from the time of diagnosis.9,18,24,25

Two staging systems have been developed to predict short-term and long-term mortality risk based on sex, age, and physiologic parameters.23,24 The GAP (gender, age, physiology) index provides an estimate of the risk of death for a cohort of patients: a score of 0 to 8 is calculated, and the score is then categorized as stage I, II, or III. Each stage is associated with 1-, 2-, and 3-year mortality rates, with stage III having the highest rates. The GAP calculator (www.acponline.org/journals/annals/extras/gap) provides an estimate of the risk of death for an individual patient. The application of these tools for the management of IPF is evolving; however, they may be helpful for counseling patients about disease prognosis.

CLUES TO DIAGNOSIS

Histologic patterns

UIP on histologic study is also seen in fibrotic lung diseases other than IPF, including connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, inhalational or occupational interstitial lung disease, and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.26–29 Consequently, the diagnosis of IPF requires exclusion of other known causes of UIP.

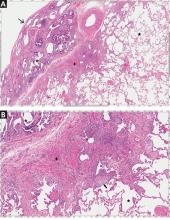

According to the 2011 guidelines,16 the histology of interstitial lung disease can be categorized as definite UIP, probable UIP, or possible UIP, or as an atypical pattern suggesting another diagnosis. If no definite cause of the interstitial lung abnormality is found, the level of certainty of the histopathologic pattern of UIP helps formulate the clinical diagnosis and management plan.

Clues on computed tomography

The UIP nomenclature also describes patterns on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). HRCT is done without contrast and produces thin-sliced images (usually < 1.5 mm) in inspiratory, expiratory, and prone views; this allows detection of air trapping, which may indicate an airway-centric alternative diagnosis.

On HRCT, UIP appears as reticular opacities, often with traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis, usually with a basilar and peripheral predominance. Honeycombing is a key feature and appears as clustered cystic spaces with well-defined walls in the periphery of the lung parenchyma. Ground-glass opacities are not a prominent feature of UIP, and although they do not exclude a UIP pattern, they should spur consideration of other diagnoses.16 Reactive mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is another common feature of UIP.

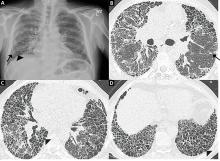

When evaluating results of HRCT for UIP, the radiologist categorizes the pattern as definite UIP, possible UIP, or inconsistent. The definite pattern meets all the above features and has none of the features suggesting an alternative diagnosis (Figure 3). The possible pattern includes all the above features with the exception of honeycombing. If the predominant features on HRCT include any atypical finding listed above, then the study is considered inconsistent with UIP. If the pattern on HRCT is considered definite, evaluation of pathology is not necessary. If the pattern is categorized as possible or is inconsistent, then surgical lung biopsy-confirmed UIP is necessary for the definitive diagnosis of IPF.

However, evidence is emerging that in the correct clinical scenario, possible UIP behaves similarly to definite UIP and may be sufficient to make the clinical diagnosis of IPF even without surgical biopsy confirmation.30

A DIAGNOSTIC ALGORITHM FOR IPF

Given the multitude of interstitial lung diseases, their complexities, and the lack of a gold standard definitive diagnostic test, the diagnosis of IPF can be difficult, requiring the integration of clinical, radiologic, and, if necessary, pathologic findings.

Demographic features

The patient’s demographic features and risk factors dictate the initial clinical suspicion of IPF compared with other interstitial lung diseases. The incidence of IPF increases with age, and IPF is more common in men. A history of smoking is another risk factor.31 A 45-year-old never-smoker is much less likely to have IPF than a 70-year-old former smoker, and a 70-year-old man is more likely to have IPF than a woman of the same age. Thus, the finding of interstitial lung disease in a patient with a demographic profile that is not typical (ie, a younger woman who never smoked) should prompt an exhaustive investigation for another diagnosis such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis or connective tissue disease.

Key elements of the history

After considering the demographic profile and risk factors, the next step in the evaluation is a thorough and accurate medical history. This should include assessment of the severity of dyspnea and cough, signs and symptoms of connective tissue disease (eg, arthralgias, sicca symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, difficulty swallowing), and gastroesophageal reflux disease, which can be associated with connective tissue disease and, independently, with IPF.

It is also important to identify any environmental exposures that suggest pneumoconiosis or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The most common risk factors for hypersensitivity pneumonitis are birds and bird feathers, molds, fungi, hot tub use, and some industrial chemicals.32

A medication history is important. Many medications are associated with interstitial lung disease, but amiodarone, bleomycin, methotrexate, and nitrofurantoin are among the common offenders.33

A thorough family history is necessary, as there are familial forms of IPF.

Focus of the physical examination

The physical examination must include careful auscultation for rales. While rales are not specific for IPF, they are the most common pulmonary abnormality. Detailed skin, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular examinations are also important to evaluate for rheumatologic signs, clubbing, or evidence of heart failure or pulmonary hypertension.

Laboratory tests

Laboratory testing should include a serologic autoantibody panel to evaluate for connective tissue diseases that can manifest as interstitial lung disease, including rheumatoid arthritis, dermatopolymyositis, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, and undifferentiated or mixed connective tissue disease. Typical preliminary laboratory tests are antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Others may include anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), anti-Scl-70, anti-RNP, anti-SS-A, anti-SS-B, and anti-Jo-1.16 The breadth of the panel should depend on patient demographics and findings in the history or physical examination that increase or decrease the likelihood of a connective tissue disease.

Lung function testing

Assessing the patient’s pulmonary physiology should include spirometry, DLCO, and body plethysmography (lung volumes). In most cases, IPF manifests with restrictive physiology. Once restrictive physiology is confirmed with a low total lung capacity, FVC testing can be used as a longitudinal surrogate, as it is less expensive and easier for the patient to perform. In general, a lower total lung capacity or FVC indicates more severe impairment.

The DLCO serves as another marker of severity but is less reliable due to baseline variability and difficulties performing the maneuver.

A 6-minute walk test is another crucial physiologic assessment tool that can quantify exertional hypoxemia and functional status (ie, distance walked), and can assist in prognosis.

Imaging

Most patients undergo chest radiography in the workup for undiagnosed dyspnea. However, chest radiography is not adequate to formulate an accurate diagnosis in suspected interstitial lung disease, and a normal radiograph cannot exclude changes that might reflect early phases of the disease. As the disease progresses, the plain radiograph can show reticulonodular opacities and honeycombing in the peripheral and lower lung zones (Figure 3).34

The decision whether to order HRCT in the workup for a patient who has dyspnea and a normal chest radiograph is challenging. We recommend cross-sectional imaging when physiologic testing shows restriction or low DLCO, or when there is a high index of suspicion for underlying lung disease as the cause of symptoms.

Expert consultation can aid with this decision, especially when the underlying cause of dyspnea remains unclear after initial studies have been completed. Otherwise, HRCT is an essential test in the evaluation of interstitial lung disease.

Bronchoscopy’s role controversial

If the pattern on HRCT is nondiagnostic, then surgical biopsy is necessary, and the diagnosis of IPF requires a histologic pattern of UIP as described above.16,35

Although bronchoscopy can be valuable if an alternative diagnosis such as sarcoidosis or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis is suspected, the role of bronchoscopic biopsy in the workup of IPF is controversial. The patchy nature of UIP does not lend itself to the relatively small biopsy samples obtained through bronchoscopy.36,37

Surgical biopsy options

The favored biopsy approach is surgical, using either an open or a video-assisted thoracoscopic technique. The latter is preferred as it is less invasive, requires a shorter length of hospital stay, and allows a faster recovery.38 Bronchoscopic cryobiopsy, currently under investigation, is a potentially valuable tool whose role in diagnosing IPF is evolving.

Frequently, neither HRCT nor surgical lung biopsy demonstrates UIP, making the definitive diagnosis of IPF difficult. Moreover, some patients with nondiagnostic HRCT results are unable to tolerate surgical lung biopsy because of severely impaired lung function or other comorbidities.

The role of multidisciplinary discussions

When surgical lung biopsy is not possible, current practice at leading centers uses a multidisciplinary approach to allow for a confident diagnosis.30,39 Discussions take place between pulmonologists, pathologists, radiologists, and other specialists to collectively consider all aspects of a case before rendering a consensus opinion on the diagnosis and the management plan. If the discussion leads to a consensus diagnosis of IPF, then the patient’s clinician can move forward with treatment options. If not, the group can recommend further workup or alternative diagnoses and treatment regimens. The multidisciplinary group is also well positioned to consider the relative risks and benefits of moving forward with surgical lung biopsy for individual patients.

This approach illustrates the importance of referring these patients to centers of excellence in diagnosing and managing complex cases of interstitial lung disease, including IPF.40

TREATMENT OF IPF

Antifibrotic therapy

Antifibrotic therapy is a choice between pirfenidone and nintedanib.

Pirfenidone, which has an undefined molecular target, was approved based on the results of 3 trials.41,42 Pooled analyses from these trials showed a reduction in the decline from baseline in FVC percent predicted and improved progression-free survival.43 Pooled and meta-analyses of pirfenidone clinical trials have shown a mortality benefit, although no individual study has shown such an effect on mortality rates.44

The major adverse effects of pirfenidone are gastrointestinal distress and photosensitivity rash.

Nintedanib is a triple tyrosine kinase inhibitor that broadly targets fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Combined analysis of 2 concurrent trials45 showed that nintedanib reduced the decline in FVC, similarly to pirfenidone. The major adverse event associated with nintedanib was diarrhea. Since it inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor, there is a risk of hematologic complications such as bleeding or clotting events.

Because pirfenidone and nintedanib can increase aminotransferase levels, regular monitoring is recommended.

To date, no trial has compared pirfenidone and nintedanib in terms of their efficacy and tolerability. Therefore, the choice of agent is based on the patient’s preference after a discussion of potential risks and expected benefits, a review of each drug’s side effects, and consideration of comorbid conditions and physician experience.

Patients need to understand that these drugs slow the rate of decline in FVC but have not been shown to improve symptoms or functional status.

Corticosteroids are not routine

Corticosteroids should not be used routinely in the treatment of IPF. Although steroids, alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive medications, were commonly used for IPF in the past, such use was not based on results of randomized controlled trials.46 Retrospective controlled studies have failed to show that corticosteroids improve mortality rates in IPF; indeed, they have shown that corticosteroids confer substantial morbidity.47,48 In addition, a randomized controlled trial combining corticosteroids with N-acetylcysteine and azathioprine was stopped early due to an increased risk of death and hospitalization.49 Collectively, these data suggest that corticosteroids confer no benefit and are potentially harmful. Their use in IPF is discouraged, and the joint international guidelines recommend against immunosuppression to treat IPF.16

Other treatments

The guidelines offer additional suggestions for the management of IPF.

Preliminary evidence suggests that microaspiration associated with abnormal gastroesophageal acid reflux is a risk factor for IPF. As such, there is a weak recommendation for aggressive treatment of reflux disease.50 However, because evidence suggests that proton-pump inhibitor therapy may be associated with adverse renal or central nervous system effects, this recommendation bears caution. It is hoped that ongoing studies will provide further insight into the role of acid-suppression in the management of IPF.51,52

Further treatment recommendations include best supportive management such as supplemental oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation, and vaccinations.

Prompt referral for lung transplant is imperative. IPF is now the most common indication for lung transplant, and given the poor overall prognosis of advanced IPF, transplant confers a survival benefit in appropriately selected patients.53,54 Table 2 provides an evidence-based checklist for the workup and management of IPF.

ACUTE EXACERBATIONS OF IPF

The unpredictable nature of IPF can manifest in the form of acute exacerbations without an identifiable cause. The loosely defined diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of acute exacerbations are a previous or new diagnosis of IPF, worsening or development of dyspnea in the last 30 days, and new bilateral ground-glass or consolidative changes with a background of UIP on HRCT.16

A new definition has been proposed55 to facilitate research in the characterization and treatment of acute exacerbations of IPF. The new definition includes all causes of respiratory deterioration except for heart failure and volume overload. It is less strict about the 30-day time frame. This newer definition is based on the lack of evidence differentiating outcomes when an acute deterioration is associated with known or unknown etiologies.55

The incidence of acute exacerbations is variable, with a 1- and 3-year incidence ranging between 8.6% and 23.9% depending on the criteria used.56 In general, acute exacerbations carry a grim prognosis, with a median life expectancy of 2.2 months.57

There is no approved therapy for exacerbations of IPF. Rather, treatment is mainly supportive with supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation. Current guidelines have a weak recommendation for the use of corticosteroids, but there are no recommendations regarding dose, route, or duration of therapy. Other treatments, primarily immunomodulatory agents, have been suggested but lack evidence of benefit.

Acknowledgments: Pathology images were provided by Carol Farver, MD, Pathology Institute, Cleveland Clinic. Radiology images were provided by Ruchi Yadav, MD, Imaging Institute, Cleveland Clinic.

- Brown KK, Raghu G. Medical treatment for pulmonary fibrosis: current trends, concepts, and prospects. Clin Chest Med 2004; 25(4):759–772, vii. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2004.08.003

- Ryerson CJ, Collard HR. Update on the diagnosis and classification of ILD. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2013; 19(5):453–459. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e328363f48d

- Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001-11. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2(7):566–572. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70101-8

- Nalysnyk L, Cid-Ruzafa J, Rotella P, Esser D. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: review of the literature. Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21(126):355–361. doi:10.1183/09059180.00002512

- Hutchinson J, Fogarty A, Hubbard R, McKeever T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2015; 46(3):795–806. doi:10.1183/09031936.00185114

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(5):395–409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Jin GY, Lynch D, Chawla A, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities in a CT lung cancer screening population: prevalence and progression rate. Radiology 2013; 268(2):563–571. doi:10.1148/radiol.13120816

- Southern BD, Scheraga RG, Yadav R. Managing interstitial lung disease detected on CT during lung cancer screening. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(1):55–65. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.14157

- King TE Jr, Schwarz MI, Brown K, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: relationship between histopathologic features and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164(5):1025–1032. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.6.2001056

- Lamas DJ, Kawut SM, Bagiella E, et al. Delayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184(7):842–847. doi:10.1164/rccm.201104-0668OC

- Jo HE, Glaspole I, Moodley Y, et al. Disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with mild physiological impairment: analysis from the Australian IPF registry. BMC Pulm Med 2018; 18(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12890-018-0575-y

- Yang IV, Schwartz DA. Epigenetics of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transl Res 2015; 165(1):48–60. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.011

- King TE Jr, Pardo A, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 2011; 378(9807):1949–1961. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60052-4

- Meltzer EB, Noble PW. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008; 3:8. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-3-8

- Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A rational clinical approach. Chest 1987; 92(1):148–154. doi:10.1378/chest.92.1.148

- Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al; ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183(6):788–824. doi:10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL

- Panos RJ, Mortenson RL, Niccoli SA, King TE Jr. Clinical deterioration in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: causes and assessment. Am J Med 1990; 88(4):396–404. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(90)90495-Y

- Ley B, Collard HR, King TE Jr. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183(4):431–440. doi:10.1164/rccm.201006-0894CI

- Collard HR, King TE Jr, Bartelson BB, Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Brown KK. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168(5):538–542. doi:10.1164/rccm.200211-1311OC

- Flaherty KR, Andrei AC, Murray S, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prognostic value of changes in physiology and six-minute-walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174(7):803–809. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-488OC

- Jegal Y, Kim DS, Shim TS, et al. Physiology is a stronger predictor of survival than pathology in fibrotic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171(6):639–644. doi:10.1164/rccm.200403-331OC

- Latsi PI, du Bois RM, Nicholson AG, et al. Fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: the prognostic value of longitudinal functional trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168(5):531–537. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1245OC

- King CS, Nathan SD. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: effects and optimal management of comorbidities. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5(1):72–84. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30222-3

- Ley B, Ryerson CJ, Vittinghoff E, et al. A multidimensional index and staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156(1):684–691. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00004

- Rudd RM, Prescott RJ, Chalmers JC, Johnston ID; Fibrosing Alveolitis Subcommittee of the Research Committee of the British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society study on cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: response to treatment and survival. Thorax 2007; 62(1):62–66. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.045591

- Gutsche M, Rosen GD, Swigris JJ. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a review. Curr Respir Care Rep 2012; 1:224–232. doi:10.1007/s13665-012-0028-7

- Park JH, Kim DS, Park IN, et al. Prognosis of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease-related subtypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175(7):705–711. doi:10.1164/rccm.200607-912OC

- Taskar VS, Coultas DB. Is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an environmental disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006; 3(4):293–298. doi:10.1513/pats.200512-131TK

- Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Cherniack RM, et al. The effect of pulmonary fibrosis on survival in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Med 2004; 116(10):662–668. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.030

- Brownell R, Moua T, Henry TS, et al. The use of pretest probability increases the value of high-resolution CT in diagnosing usual interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 2017; 72(5):424–429. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209671

- Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Stidley CA, Colby TV, Waldron JA. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155(1):242–248. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001319

- Selman M, Pardo A, King TE Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186(4):314–324. doi:10.1164/rccm.201203-0513CI

- Schwaiblmair M, Behr W, Haeckel T, Markl B, Foerg W, Berghaus T. Drug induced interstitial lung disease. Open Respir Med J 2012; 6:63–74. doi:10.2174/1874306401206010063

- Grenier P, Valeyre D, Cluzel P, Brauner MW, Lenoir S, Chastang C. Chronic diffuse interstitial lung disease: diagnostic value of chest radiography and high-resolution CT. Radiology 1991; 179(1):123–132. doi:10.1148/radiology.179.1.2006262

- Lynch JP 3rd, Huynh RH, Fishbein MC, Saggar R, Belperio JA, Weigt SS. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: epidemiology, clinical features, prognosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 37(3):331–357. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1582011

- Berbescu EA, Katzenstein AL, Snow JL, Zisman DA. Transbronchial biopsy in usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest 2006; 129(5):1126–1131. doi:10.1378/chest.129.5.1126

- Ohshimo S, Bonella F, Cui A, et al. Significance of bronchoalveolar lavage for the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179(11):1043–1047. doi:10.1164/rccm.200808-1313OC

- Oparka J, Yan TD, Ryan E, Dunning J. Does video-assisted thoracic surgery provide a safe alternative to conventional techniques in patients with limited pulmonary function who are otherwise suitable for lung resection? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013; 17(1):159–162. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivt097

- Flaherty KR, King TE Jr, Raghu G, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170(8):904–910. doi:10.1164/rccm.200402-147OC

- Walsh SL, Wells AU, Desai SR, et al. Multicentre evaluation of multidisciplinary team meeting agreement on diagnosis in diffuse parenchymal lung disease: a case-cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4(7):557–565. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30033-9

- King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al; ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(22):2083–2092. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1402582

- Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al; CAPACITY Study Group. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 377(9779):1760–1769. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4

- Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of pooled data from three multinational phase 3 trials. Eur Respir J 2016; 47(1):243–253. doi:10.1183/13993003.00026-2015

- Nathan SD, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Effect of pirfenidone on mortality: pooled analyses and meta-analyses of clinical trials in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5(1):33–41. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30326-5

- Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al; INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(22):2071–2082. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1402584

- Richeldi L, Davies HR, Ferrara G, Franco F. Corticosteroids for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003: 3:CD002880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002880

- Douglas WW, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: impact of oxygen and colchicine, prednisone, or no therapy on survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161(4 pt 1):1172–1178. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9907002

- Gay SE, Kazerooni EA, Toews GB, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: predicting response to therapy and survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157(4 pt 1):1063–1072. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9703022

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network; Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr, Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(21):1968–1977. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1113354

- Raghu G, Freudenberger TD, Yang S, et al. High prevalence of abnormal acid gastro-oesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2006; 27(1):136–142. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00037005

- Gomm W, von Holt K, Thome F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73(4):410–416. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791

- Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, Xian H, Balasubramanian S, Al-Aly Z. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27(10):3153–3163. doi:10.1681/ASN.2015121377

- Thabut G, Mal H, Castier Y, et al. Survival benefit of lung transplantation for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 126(2):469–475. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00600-7

- Valapour M, Skeans MA, Smith JM, et al. Lung. Am J Transplant 2016; 16(suppl 2):141–168. doi:10.1111/ajt.13671

- Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An International Working Group Report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194(3):265–275. doi:10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI

- Kondoh Y, Taniguchi H, Katsuta T, et al. Risk factors of acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2010; 27(2):103–110. doi:10.1016/j.resinv.2015.04.005

- Song JW, Hong SB, Lim CM, Koh Y, Kim DS. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur Respir J 2011; 37(2):356–363. doi:10.1183/09031936.00159709

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating and fatal lung disease that generally affects older adults. It is characterized by a radiographic and histopathologic pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) that has no other known etiology.

Accurate diagnosis of IPF is crucial. We recommend early referral to a center specializing in interstitial lung disease to confirm the diagnosis, start appropriate therapy, advise the patient on prognosis and enrollment in disease registries and clinical trials, and determine candidacy for lung transplant.

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to encounter patients with IPF, whether because of a patient complaint or as an incidental finding on computed tomography. The goal of this article is to delineate the features of IPF so that it may be recognized early and thus expedite referral to a center with expertise in interstitial lung disease for a thorough evaluation and appropriate management.

WHAT IS IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS?

MORE COMMON THAN ONCE THOUGHT

The true incidence and prevalence of IPF are difficult to assess. IPF is generally considered a rare disease, but it is more common than once thought. In 2011, Raghu et al3 estimated the prevalence in Medicare beneficiaries to be 495 cases per 100,000. Based on this estimate and the current US population, up to 160,000 Americans could have IPF.4 Raghu et al also showed that IPF more often affects adults over age 65, which suggests that as the US population ages, the incidence of IPF may rise. Studies have also reported an increased incidence of IPF worldwide.5

Further, with the rising use of low-dose computed tomography to screen for lung cancer, more incidental cases of IPF will likely be found.6–8

Older data showed a lag from symptom onset to accurate diagnosis of 1 to 2 years.9 A more recent study found a lag in referral of patients with IPF to tertiary care centers, and this delay was associated with a higher rate of death independent of disease severity.10

TYPICALLY PROGRESSIVE, OFTEN FATAL

IPF is typically progressive and limited to the lungs, and it portends a poor prognosis. The median survival is commonly cited as 2 to 5 years from diagnosis, although this is based on older observations that may not reflect current best practice and newer therapies. More recent studies suggest higher survival rates if patients have preserved lung function.11

As the name indicates, the etiology of IPF is unknown, but studies have indicated genetic underpinnings in a notable proportion of cases.12 Regardless of the cause, the pathogenesis and progression of IPF are thought to be the result of an abnormal and persistent wound-repair response. The progressive deposition of scar tissue disrupts normal lung architecture and function, eventually causing clinical disease.13

SYMPTOMS AND KEY FEATURES

Patients with IPF typically present with the insidious onset of dyspnea on exertion, with or without chronic cough. Risk factors include male sex, increasing age, and a history of smoking. Patients with undiagnosed IPF who present with dyspnea and a history of smoking are often treated empirically for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Rales are a common finding on auscultation in IPF, and this can lead to an exhaustive cardiac evaluation and empiric treatment for heart failure. Digital clubbing is also relatively common.14 Hypoxemia with exertion is another common feature that also often correlates with disease severity and prognosis. Resting hypoxemia is more common in advanced disease.

On spirometry, patients with IPF typically demonstrate restrictive physiology, suggested by a normal or elevated ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 second to the forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) (> 70% predicted or above the lower limit of normal) combined with a lower than normal FVC. Restrictive physiology is definitively demonstrated by a decreased total lung capacity (< 80% predicted or below the lower limit of normal) on plethysmography. Impaired gas exchange, manifested by a decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) on pulmonary function testing, is also common. Because pulmonary perfusion is higher in the lung bases, where IPF is also predominant, the DLCO is often reduced to a greater extent than the FVC.

PROGNOSTIC INDICATORS

Clinicians typically view IPF as a relentless and progressive process, but its course is variable and can be uncertain in an individual patient (Figure 1).15,16 Nevertheless, over time, most patients have a decline in lung function leading to respiratory failure. Respiratory failure, often preceded by a subacute deterioration (over weeks to months) or an acute deterioration (< 4 weeks), is the most common cause of death, but comorbid diseases such as lung cancer, infection, and heart failure are also common causes of death in these patients.17,18

Predictors of mortality include worsening FVC, DLCO, symptoms, and physiologic impairment, manifested by a decline in the 6-minute walking test or worsening exertional hypoxemia.19–22 Other common comorbidities linked with impaired quality of life and poor prognosis include obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression.16,23 Retrospective studies suggest that most IPF patients die 2 to 5 years after symptom onset. With the lag from symptom onset to final diagnosis, the average life expectancy is as little as 2 years from the time of diagnosis.9,18,24,25

Two staging systems have been developed to predict short-term and long-term mortality risk based on sex, age, and physiologic parameters.23,24 The GAP (gender, age, physiology) index provides an estimate of the risk of death for a cohort of patients: a score of 0 to 8 is calculated, and the score is then categorized as stage I, II, or III. Each stage is associated with 1-, 2-, and 3-year mortality rates, with stage III having the highest rates. The GAP calculator (www.acponline.org/journals/annals/extras/gap) provides an estimate of the risk of death for an individual patient. The application of these tools for the management of IPF is evolving; however, they may be helpful for counseling patients about disease prognosis.

CLUES TO DIAGNOSIS

Histologic patterns

UIP on histologic study is also seen in fibrotic lung diseases other than IPF, including connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, inhalational or occupational interstitial lung disease, and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.26–29 Consequently, the diagnosis of IPF requires exclusion of other known causes of UIP.

According to the 2011 guidelines,16 the histology of interstitial lung disease can be categorized as definite UIP, probable UIP, or possible UIP, or as an atypical pattern suggesting another diagnosis. If no definite cause of the interstitial lung abnormality is found, the level of certainty of the histopathologic pattern of UIP helps formulate the clinical diagnosis and management plan.

Clues on computed tomography

The UIP nomenclature also describes patterns on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). HRCT is done without contrast and produces thin-sliced images (usually < 1.5 mm) in inspiratory, expiratory, and prone views; this allows detection of air trapping, which may indicate an airway-centric alternative diagnosis.

On HRCT, UIP appears as reticular opacities, often with traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis, usually with a basilar and peripheral predominance. Honeycombing is a key feature and appears as clustered cystic spaces with well-defined walls in the periphery of the lung parenchyma. Ground-glass opacities are not a prominent feature of UIP, and although they do not exclude a UIP pattern, they should spur consideration of other diagnoses.16 Reactive mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is another common feature of UIP.

When evaluating results of HRCT for UIP, the radiologist categorizes the pattern as definite UIP, possible UIP, or inconsistent. The definite pattern meets all the above features and has none of the features suggesting an alternative diagnosis (Figure 3). The possible pattern includes all the above features with the exception of honeycombing. If the predominant features on HRCT include any atypical finding listed above, then the study is considered inconsistent with UIP. If the pattern on HRCT is considered definite, evaluation of pathology is not necessary. If the pattern is categorized as possible or is inconsistent, then surgical lung biopsy-confirmed UIP is necessary for the definitive diagnosis of IPF.

However, evidence is emerging that in the correct clinical scenario, possible UIP behaves similarly to definite UIP and may be sufficient to make the clinical diagnosis of IPF even without surgical biopsy confirmation.30

A DIAGNOSTIC ALGORITHM FOR IPF

Given the multitude of interstitial lung diseases, their complexities, and the lack of a gold standard definitive diagnostic test, the diagnosis of IPF can be difficult, requiring the integration of clinical, radiologic, and, if necessary, pathologic findings.

Demographic features

The patient’s demographic features and risk factors dictate the initial clinical suspicion of IPF compared with other interstitial lung diseases. The incidence of IPF increases with age, and IPF is more common in men. A history of smoking is another risk factor.31 A 45-year-old never-smoker is much less likely to have IPF than a 70-year-old former smoker, and a 70-year-old man is more likely to have IPF than a woman of the same age. Thus, the finding of interstitial lung disease in a patient with a demographic profile that is not typical (ie, a younger woman who never smoked) should prompt an exhaustive investigation for another diagnosis such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis or connective tissue disease.

Key elements of the history

After considering the demographic profile and risk factors, the next step in the evaluation is a thorough and accurate medical history. This should include assessment of the severity of dyspnea and cough, signs and symptoms of connective tissue disease (eg, arthralgias, sicca symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, difficulty swallowing), and gastroesophageal reflux disease, which can be associated with connective tissue disease and, independently, with IPF.

It is also important to identify any environmental exposures that suggest pneumoconiosis or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The most common risk factors for hypersensitivity pneumonitis are birds and bird feathers, molds, fungi, hot tub use, and some industrial chemicals.32

A medication history is important. Many medications are associated with interstitial lung disease, but amiodarone, bleomycin, methotrexate, and nitrofurantoin are among the common offenders.33

A thorough family history is necessary, as there are familial forms of IPF.

Focus of the physical examination

The physical examination must include careful auscultation for rales. While rales are not specific for IPF, they are the most common pulmonary abnormality. Detailed skin, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular examinations are also important to evaluate for rheumatologic signs, clubbing, or evidence of heart failure or pulmonary hypertension.

Laboratory tests

Laboratory testing should include a serologic autoantibody panel to evaluate for connective tissue diseases that can manifest as interstitial lung disease, including rheumatoid arthritis, dermatopolymyositis, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, and undifferentiated or mixed connective tissue disease. Typical preliminary laboratory tests are antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Others may include anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), anti-Scl-70, anti-RNP, anti-SS-A, anti-SS-B, and anti-Jo-1.16 The breadth of the panel should depend on patient demographics and findings in the history or physical examination that increase or decrease the likelihood of a connective tissue disease.

Lung function testing

Assessing the patient’s pulmonary physiology should include spirometry, DLCO, and body plethysmography (lung volumes). In most cases, IPF manifests with restrictive physiology. Once restrictive physiology is confirmed with a low total lung capacity, FVC testing can be used as a longitudinal surrogate, as it is less expensive and easier for the patient to perform. In general, a lower total lung capacity or FVC indicates more severe impairment.

The DLCO serves as another marker of severity but is less reliable due to baseline variability and difficulties performing the maneuver.

A 6-minute walk test is another crucial physiologic assessment tool that can quantify exertional hypoxemia and functional status (ie, distance walked), and can assist in prognosis.

Imaging

Most patients undergo chest radiography in the workup for undiagnosed dyspnea. However, chest radiography is not adequate to formulate an accurate diagnosis in suspected interstitial lung disease, and a normal radiograph cannot exclude changes that might reflect early phases of the disease. As the disease progresses, the plain radiograph can show reticulonodular opacities and honeycombing in the peripheral and lower lung zones (Figure 3).34

The decision whether to order HRCT in the workup for a patient who has dyspnea and a normal chest radiograph is challenging. We recommend cross-sectional imaging when physiologic testing shows restriction or low DLCO, or when there is a high index of suspicion for underlying lung disease as the cause of symptoms.

Expert consultation can aid with this decision, especially when the underlying cause of dyspnea remains unclear after initial studies have been completed. Otherwise, HRCT is an essential test in the evaluation of interstitial lung disease.

Bronchoscopy’s role controversial

If the pattern on HRCT is nondiagnostic, then surgical biopsy is necessary, and the diagnosis of IPF requires a histologic pattern of UIP as described above.16,35

Although bronchoscopy can be valuable if an alternative diagnosis such as sarcoidosis or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis is suspected, the role of bronchoscopic biopsy in the workup of IPF is controversial. The patchy nature of UIP does not lend itself to the relatively small biopsy samples obtained through bronchoscopy.36,37

Surgical biopsy options

The favored biopsy approach is surgical, using either an open or a video-assisted thoracoscopic technique. The latter is preferred as it is less invasive, requires a shorter length of hospital stay, and allows a faster recovery.38 Bronchoscopic cryobiopsy, currently under investigation, is a potentially valuable tool whose role in diagnosing IPF is evolving.

Frequently, neither HRCT nor surgical lung biopsy demonstrates UIP, making the definitive diagnosis of IPF difficult. Moreover, some patients with nondiagnostic HRCT results are unable to tolerate surgical lung biopsy because of severely impaired lung function or other comorbidities.

The role of multidisciplinary discussions

When surgical lung biopsy is not possible, current practice at leading centers uses a multidisciplinary approach to allow for a confident diagnosis.30,39 Discussions take place between pulmonologists, pathologists, radiologists, and other specialists to collectively consider all aspects of a case before rendering a consensus opinion on the diagnosis and the management plan. If the discussion leads to a consensus diagnosis of IPF, then the patient’s clinician can move forward with treatment options. If not, the group can recommend further workup or alternative diagnoses and treatment regimens. The multidisciplinary group is also well positioned to consider the relative risks and benefits of moving forward with surgical lung biopsy for individual patients.

This approach illustrates the importance of referring these patients to centers of excellence in diagnosing and managing complex cases of interstitial lung disease, including IPF.40

TREATMENT OF IPF

Antifibrotic therapy

Antifibrotic therapy is a choice between pirfenidone and nintedanib.

Pirfenidone, which has an undefined molecular target, was approved based on the results of 3 trials.41,42 Pooled analyses from these trials showed a reduction in the decline from baseline in FVC percent predicted and improved progression-free survival.43 Pooled and meta-analyses of pirfenidone clinical trials have shown a mortality benefit, although no individual study has shown such an effect on mortality rates.44

The major adverse effects of pirfenidone are gastrointestinal distress and photosensitivity rash.

Nintedanib is a triple tyrosine kinase inhibitor that broadly targets fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Combined analysis of 2 concurrent trials45 showed that nintedanib reduced the decline in FVC, similarly to pirfenidone. The major adverse event associated with nintedanib was diarrhea. Since it inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor, there is a risk of hematologic complications such as bleeding or clotting events.

Because pirfenidone and nintedanib can increase aminotransferase levels, regular monitoring is recommended.

To date, no trial has compared pirfenidone and nintedanib in terms of their efficacy and tolerability. Therefore, the choice of agent is based on the patient’s preference after a discussion of potential risks and expected benefits, a review of each drug’s side effects, and consideration of comorbid conditions and physician experience.

Patients need to understand that these drugs slow the rate of decline in FVC but have not been shown to improve symptoms or functional status.

Corticosteroids are not routine

Corticosteroids should not be used routinely in the treatment of IPF. Although steroids, alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive medications, were commonly used for IPF in the past, such use was not based on results of randomized controlled trials.46 Retrospective controlled studies have failed to show that corticosteroids improve mortality rates in IPF; indeed, they have shown that corticosteroids confer substantial morbidity.47,48 In addition, a randomized controlled trial combining corticosteroids with N-acetylcysteine and azathioprine was stopped early due to an increased risk of death and hospitalization.49 Collectively, these data suggest that corticosteroids confer no benefit and are potentially harmful. Their use in IPF is discouraged, and the joint international guidelines recommend against immunosuppression to treat IPF.16

Other treatments

The guidelines offer additional suggestions for the management of IPF.

Preliminary evidence suggests that microaspiration associated with abnormal gastroesophageal acid reflux is a risk factor for IPF. As such, there is a weak recommendation for aggressive treatment of reflux disease.50 However, because evidence suggests that proton-pump inhibitor therapy may be associated with adverse renal or central nervous system effects, this recommendation bears caution. It is hoped that ongoing studies will provide further insight into the role of acid-suppression in the management of IPF.51,52

Further treatment recommendations include best supportive management such as supplemental oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation, and vaccinations.

Prompt referral for lung transplant is imperative. IPF is now the most common indication for lung transplant, and given the poor overall prognosis of advanced IPF, transplant confers a survival benefit in appropriately selected patients.53,54 Table 2 provides an evidence-based checklist for the workup and management of IPF.

ACUTE EXACERBATIONS OF IPF

The unpredictable nature of IPF can manifest in the form of acute exacerbations without an identifiable cause. The loosely defined diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of acute exacerbations are a previous or new diagnosis of IPF, worsening or development of dyspnea in the last 30 days, and new bilateral ground-glass or consolidative changes with a background of UIP on HRCT.16

A new definition has been proposed55 to facilitate research in the characterization and treatment of acute exacerbations of IPF. The new definition includes all causes of respiratory deterioration except for heart failure and volume overload. It is less strict about the 30-day time frame. This newer definition is based on the lack of evidence differentiating outcomes when an acute deterioration is associated with known or unknown etiologies.55

The incidence of acute exacerbations is variable, with a 1- and 3-year incidence ranging between 8.6% and 23.9% depending on the criteria used.56 In general, acute exacerbations carry a grim prognosis, with a median life expectancy of 2.2 months.57

There is no approved therapy for exacerbations of IPF. Rather, treatment is mainly supportive with supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation. Current guidelines have a weak recommendation for the use of corticosteroids, but there are no recommendations regarding dose, route, or duration of therapy. Other treatments, primarily immunomodulatory agents, have been suggested but lack evidence of benefit.

Acknowledgments: Pathology images were provided by Carol Farver, MD, Pathology Institute, Cleveland Clinic. Radiology images were provided by Ruchi Yadav, MD, Imaging Institute, Cleveland Clinic.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating and fatal lung disease that generally affects older adults. It is characterized by a radiographic and histopathologic pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) that has no other known etiology.

Accurate diagnosis of IPF is crucial. We recommend early referral to a center specializing in interstitial lung disease to confirm the diagnosis, start appropriate therapy, advise the patient on prognosis and enrollment in disease registries and clinical trials, and determine candidacy for lung transplant.

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to encounter patients with IPF, whether because of a patient complaint or as an incidental finding on computed tomography. The goal of this article is to delineate the features of IPF so that it may be recognized early and thus expedite referral to a center with expertise in interstitial lung disease for a thorough evaluation and appropriate management.

WHAT IS IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS?

MORE COMMON THAN ONCE THOUGHT

The true incidence and prevalence of IPF are difficult to assess. IPF is generally considered a rare disease, but it is more common than once thought. In 2011, Raghu et al3 estimated the prevalence in Medicare beneficiaries to be 495 cases per 100,000. Based on this estimate and the current US population, up to 160,000 Americans could have IPF.4 Raghu et al also showed that IPF more often affects adults over age 65, which suggests that as the US population ages, the incidence of IPF may rise. Studies have also reported an increased incidence of IPF worldwide.5

Further, with the rising use of low-dose computed tomography to screen for lung cancer, more incidental cases of IPF will likely be found.6–8

Older data showed a lag from symptom onset to accurate diagnosis of 1 to 2 years.9 A more recent study found a lag in referral of patients with IPF to tertiary care centers, and this delay was associated with a higher rate of death independent of disease severity.10

TYPICALLY PROGRESSIVE, OFTEN FATAL

IPF is typically progressive and limited to the lungs, and it portends a poor prognosis. The median survival is commonly cited as 2 to 5 years from diagnosis, although this is based on older observations that may not reflect current best practice and newer therapies. More recent studies suggest higher survival rates if patients have preserved lung function.11

As the name indicates, the etiology of IPF is unknown, but studies have indicated genetic underpinnings in a notable proportion of cases.12 Regardless of the cause, the pathogenesis and progression of IPF are thought to be the result of an abnormal and persistent wound-repair response. The progressive deposition of scar tissue disrupts normal lung architecture and function, eventually causing clinical disease.13

SYMPTOMS AND KEY FEATURES

Patients with IPF typically present with the insidious onset of dyspnea on exertion, with or without chronic cough. Risk factors include male sex, increasing age, and a history of smoking. Patients with undiagnosed IPF who present with dyspnea and a history of smoking are often treated empirically for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Rales are a common finding on auscultation in IPF, and this can lead to an exhaustive cardiac evaluation and empiric treatment for heart failure. Digital clubbing is also relatively common.14 Hypoxemia with exertion is another common feature that also often correlates with disease severity and prognosis. Resting hypoxemia is more common in advanced disease.

On spirometry, patients with IPF typically demonstrate restrictive physiology, suggested by a normal or elevated ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 second to the forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) (> 70% predicted or above the lower limit of normal) combined with a lower than normal FVC. Restrictive physiology is definitively demonstrated by a decreased total lung capacity (< 80% predicted or below the lower limit of normal) on plethysmography. Impaired gas exchange, manifested by a decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) on pulmonary function testing, is also common. Because pulmonary perfusion is higher in the lung bases, where IPF is also predominant, the DLCO is often reduced to a greater extent than the FVC.

PROGNOSTIC INDICATORS

Clinicians typically view IPF as a relentless and progressive process, but its course is variable and can be uncertain in an individual patient (Figure 1).15,16 Nevertheless, over time, most patients have a decline in lung function leading to respiratory failure. Respiratory failure, often preceded by a subacute deterioration (over weeks to months) or an acute deterioration (< 4 weeks), is the most common cause of death, but comorbid diseases such as lung cancer, infection, and heart failure are also common causes of death in these patients.17,18

Predictors of mortality include worsening FVC, DLCO, symptoms, and physiologic impairment, manifested by a decline in the 6-minute walking test or worsening exertional hypoxemia.19–22 Other common comorbidities linked with impaired quality of life and poor prognosis include obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression.16,23 Retrospective studies suggest that most IPF patients die 2 to 5 years after symptom onset. With the lag from symptom onset to final diagnosis, the average life expectancy is as little as 2 years from the time of diagnosis.9,18,24,25

Two staging systems have been developed to predict short-term and long-term mortality risk based on sex, age, and physiologic parameters.23,24 The GAP (gender, age, physiology) index provides an estimate of the risk of death for a cohort of patients: a score of 0 to 8 is calculated, and the score is then categorized as stage I, II, or III. Each stage is associated with 1-, 2-, and 3-year mortality rates, with stage III having the highest rates. The GAP calculator (www.acponline.org/journals/annals/extras/gap) provides an estimate of the risk of death for an individual patient. The application of these tools for the management of IPF is evolving; however, they may be helpful for counseling patients about disease prognosis.

CLUES TO DIAGNOSIS

Histologic patterns

UIP on histologic study is also seen in fibrotic lung diseases other than IPF, including connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, inhalational or occupational interstitial lung disease, and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.26–29 Consequently, the diagnosis of IPF requires exclusion of other known causes of UIP.

According to the 2011 guidelines,16 the histology of interstitial lung disease can be categorized as definite UIP, probable UIP, or possible UIP, or as an atypical pattern suggesting another diagnosis. If no definite cause of the interstitial lung abnormality is found, the level of certainty of the histopathologic pattern of UIP helps formulate the clinical diagnosis and management plan.

Clues on computed tomography

The UIP nomenclature also describes patterns on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). HRCT is done without contrast and produces thin-sliced images (usually < 1.5 mm) in inspiratory, expiratory, and prone views; this allows detection of air trapping, which may indicate an airway-centric alternative diagnosis.

On HRCT, UIP appears as reticular opacities, often with traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis, usually with a basilar and peripheral predominance. Honeycombing is a key feature and appears as clustered cystic spaces with well-defined walls in the periphery of the lung parenchyma. Ground-glass opacities are not a prominent feature of UIP, and although they do not exclude a UIP pattern, they should spur consideration of other diagnoses.16 Reactive mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is another common feature of UIP.

When evaluating results of HRCT for UIP, the radiologist categorizes the pattern as definite UIP, possible UIP, or inconsistent. The definite pattern meets all the above features and has none of the features suggesting an alternative diagnosis (Figure 3). The possible pattern includes all the above features with the exception of honeycombing. If the predominant features on HRCT include any atypical finding listed above, then the study is considered inconsistent with UIP. If the pattern on HRCT is considered definite, evaluation of pathology is not necessary. If the pattern is categorized as possible or is inconsistent, then surgical lung biopsy-confirmed UIP is necessary for the definitive diagnosis of IPF.

However, evidence is emerging that in the correct clinical scenario, possible UIP behaves similarly to definite UIP and may be sufficient to make the clinical diagnosis of IPF even without surgical biopsy confirmation.30

A DIAGNOSTIC ALGORITHM FOR IPF

Given the multitude of interstitial lung diseases, their complexities, and the lack of a gold standard definitive diagnostic test, the diagnosis of IPF can be difficult, requiring the integration of clinical, radiologic, and, if necessary, pathologic findings.

Demographic features

The patient’s demographic features and risk factors dictate the initial clinical suspicion of IPF compared with other interstitial lung diseases. The incidence of IPF increases with age, and IPF is more common in men. A history of smoking is another risk factor.31 A 45-year-old never-smoker is much less likely to have IPF than a 70-year-old former smoker, and a 70-year-old man is more likely to have IPF than a woman of the same age. Thus, the finding of interstitial lung disease in a patient with a demographic profile that is not typical (ie, a younger woman who never smoked) should prompt an exhaustive investigation for another diagnosis such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis or connective tissue disease.

Key elements of the history

After considering the demographic profile and risk factors, the next step in the evaluation is a thorough and accurate medical history. This should include assessment of the severity of dyspnea and cough, signs and symptoms of connective tissue disease (eg, arthralgias, sicca symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, difficulty swallowing), and gastroesophageal reflux disease, which can be associated with connective tissue disease and, independently, with IPF.

It is also important to identify any environmental exposures that suggest pneumoconiosis or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The most common risk factors for hypersensitivity pneumonitis are birds and bird feathers, molds, fungi, hot tub use, and some industrial chemicals.32

A medication history is important. Many medications are associated with interstitial lung disease, but amiodarone, bleomycin, methotrexate, and nitrofurantoin are among the common offenders.33

A thorough family history is necessary, as there are familial forms of IPF.

Focus of the physical examination

The physical examination must include careful auscultation for rales. While rales are not specific for IPF, they are the most common pulmonary abnormality. Detailed skin, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular examinations are also important to evaluate for rheumatologic signs, clubbing, or evidence of heart failure or pulmonary hypertension.

Laboratory tests

Laboratory testing should include a serologic autoantibody panel to evaluate for connective tissue diseases that can manifest as interstitial lung disease, including rheumatoid arthritis, dermatopolymyositis, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, and undifferentiated or mixed connective tissue disease. Typical preliminary laboratory tests are antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Others may include anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), anti-Scl-70, anti-RNP, anti-SS-A, anti-SS-B, and anti-Jo-1.16 The breadth of the panel should depend on patient demographics and findings in the history or physical examination that increase or decrease the likelihood of a connective tissue disease.

Lung function testing

Assessing the patient’s pulmonary physiology should include spirometry, DLCO, and body plethysmography (lung volumes). In most cases, IPF manifests with restrictive physiology. Once restrictive physiology is confirmed with a low total lung capacity, FVC testing can be used as a longitudinal surrogate, as it is less expensive and easier for the patient to perform. In general, a lower total lung capacity or FVC indicates more severe impairment.

The DLCO serves as another marker of severity but is less reliable due to baseline variability and difficulties performing the maneuver.

A 6-minute walk test is another crucial physiologic assessment tool that can quantify exertional hypoxemia and functional status (ie, distance walked), and can assist in prognosis.

Imaging

Most patients undergo chest radiography in the workup for undiagnosed dyspnea. However, chest radiography is not adequate to formulate an accurate diagnosis in suspected interstitial lung disease, and a normal radiograph cannot exclude changes that might reflect early phases of the disease. As the disease progresses, the plain radiograph can show reticulonodular opacities and honeycombing in the peripheral and lower lung zones (Figure 3).34

The decision whether to order HRCT in the workup for a patient who has dyspnea and a normal chest radiograph is challenging. We recommend cross-sectional imaging when physiologic testing shows restriction or low DLCO, or when there is a high index of suspicion for underlying lung disease as the cause of symptoms.

Expert consultation can aid with this decision, especially when the underlying cause of dyspnea remains unclear after initial studies have been completed. Otherwise, HRCT is an essential test in the evaluation of interstitial lung disease.

Bronchoscopy’s role controversial

If the pattern on HRCT is nondiagnostic, then surgical biopsy is necessary, and the diagnosis of IPF requires a histologic pattern of UIP as described above.16,35

Although bronchoscopy can be valuable if an alternative diagnosis such as sarcoidosis or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis is suspected, the role of bronchoscopic biopsy in the workup of IPF is controversial. The patchy nature of UIP does not lend itself to the relatively small biopsy samples obtained through bronchoscopy.36,37

Surgical biopsy options

The favored biopsy approach is surgical, using either an open or a video-assisted thoracoscopic technique. The latter is preferred as it is less invasive, requires a shorter length of hospital stay, and allows a faster recovery.38 Bronchoscopic cryobiopsy, currently under investigation, is a potentially valuable tool whose role in diagnosing IPF is evolving.

Frequently, neither HRCT nor surgical lung biopsy demonstrates UIP, making the definitive diagnosis of IPF difficult. Moreover, some patients with nondiagnostic HRCT results are unable to tolerate surgical lung biopsy because of severely impaired lung function or other comorbidities.

The role of multidisciplinary discussions

When surgical lung biopsy is not possible, current practice at leading centers uses a multidisciplinary approach to allow for a confident diagnosis.30,39 Discussions take place between pulmonologists, pathologists, radiologists, and other specialists to collectively consider all aspects of a case before rendering a consensus opinion on the diagnosis and the management plan. If the discussion leads to a consensus diagnosis of IPF, then the patient’s clinician can move forward with treatment options. If not, the group can recommend further workup or alternative diagnoses and treatment regimens. The multidisciplinary group is also well positioned to consider the relative risks and benefits of moving forward with surgical lung biopsy for individual patients.

This approach illustrates the importance of referring these patients to centers of excellence in diagnosing and managing complex cases of interstitial lung disease, including IPF.40

TREATMENT OF IPF

Antifibrotic therapy

Antifibrotic therapy is a choice between pirfenidone and nintedanib.

Pirfenidone, which has an undefined molecular target, was approved based on the results of 3 trials.41,42 Pooled analyses from these trials showed a reduction in the decline from baseline in FVC percent predicted and improved progression-free survival.43 Pooled and meta-analyses of pirfenidone clinical trials have shown a mortality benefit, although no individual study has shown such an effect on mortality rates.44

The major adverse effects of pirfenidone are gastrointestinal distress and photosensitivity rash.

Nintedanib is a triple tyrosine kinase inhibitor that broadly targets fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Combined analysis of 2 concurrent trials45 showed that nintedanib reduced the decline in FVC, similarly to pirfenidone. The major adverse event associated with nintedanib was diarrhea. Since it inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor, there is a risk of hematologic complications such as bleeding or clotting events.

Because pirfenidone and nintedanib can increase aminotransferase levels, regular monitoring is recommended.

To date, no trial has compared pirfenidone and nintedanib in terms of their efficacy and tolerability. Therefore, the choice of agent is based on the patient’s preference after a discussion of potential risks and expected benefits, a review of each drug’s side effects, and consideration of comorbid conditions and physician experience.

Patients need to understand that these drugs slow the rate of decline in FVC but have not been shown to improve symptoms or functional status.

Corticosteroids are not routine

Corticosteroids should not be used routinely in the treatment of IPF. Although steroids, alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive medications, were commonly used for IPF in the past, such use was not based on results of randomized controlled trials.46 Retrospective controlled studies have failed to show that corticosteroids improve mortality rates in IPF; indeed, they have shown that corticosteroids confer substantial morbidity.47,48 In addition, a randomized controlled trial combining corticosteroids with N-acetylcysteine and azathioprine was stopped early due to an increased risk of death and hospitalization.49 Collectively, these data suggest that corticosteroids confer no benefit and are potentially harmful. Their use in IPF is discouraged, and the joint international guidelines recommend against immunosuppression to treat IPF.16

Other treatments

The guidelines offer additional suggestions for the management of IPF.

Preliminary evidence suggests that microaspiration associated with abnormal gastroesophageal acid reflux is a risk factor for IPF. As such, there is a weak recommendation for aggressive treatment of reflux disease.50 However, because evidence suggests that proton-pump inhibitor therapy may be associated with adverse renal or central nervous system effects, this recommendation bears caution. It is hoped that ongoing studies will provide further insight into the role of acid-suppression in the management of IPF.51,52

Further treatment recommendations include best supportive management such as supplemental oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation, and vaccinations.

Prompt referral for lung transplant is imperative. IPF is now the most common indication for lung transplant, and given the poor overall prognosis of advanced IPF, transplant confers a survival benefit in appropriately selected patients.53,54 Table 2 provides an evidence-based checklist for the workup and management of IPF.

ACUTE EXACERBATIONS OF IPF

The unpredictable nature of IPF can manifest in the form of acute exacerbations without an identifiable cause. The loosely defined diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of acute exacerbations are a previous or new diagnosis of IPF, worsening or development of dyspnea in the last 30 days, and new bilateral ground-glass or consolidative changes with a background of UIP on HRCT.16

A new definition has been proposed55 to facilitate research in the characterization and treatment of acute exacerbations of IPF. The new definition includes all causes of respiratory deterioration except for heart failure and volume overload. It is less strict about the 30-day time frame. This newer definition is based on the lack of evidence differentiating outcomes when an acute deterioration is associated with known or unknown etiologies.55

The incidence of acute exacerbations is variable, with a 1- and 3-year incidence ranging between 8.6% and 23.9% depending on the criteria used.56 In general, acute exacerbations carry a grim prognosis, with a median life expectancy of 2.2 months.57

There is no approved therapy for exacerbations of IPF. Rather, treatment is mainly supportive with supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation. Current guidelines have a weak recommendation for the use of corticosteroids, but there are no recommendations regarding dose, route, or duration of therapy. Other treatments, primarily immunomodulatory agents, have been suggested but lack evidence of benefit.

Acknowledgments: Pathology images were provided by Carol Farver, MD, Pathology Institute, Cleveland Clinic. Radiology images were provided by Ruchi Yadav, MD, Imaging Institute, Cleveland Clinic.

- Brown KK, Raghu G. Medical treatment for pulmonary fibrosis: current trends, concepts, and prospects. Clin Chest Med 2004; 25(4):759–772, vii. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2004.08.003

- Ryerson CJ, Collard HR. Update on the diagnosis and classification of ILD. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2013; 19(5):453–459. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e328363f48d

- Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001-11. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2(7):566–572. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70101-8

- Nalysnyk L, Cid-Ruzafa J, Rotella P, Esser D. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: review of the literature. Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21(126):355–361. doi:10.1183/09059180.00002512

- Hutchinson J, Fogarty A, Hubbard R, McKeever T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2015; 46(3):795–806. doi:10.1183/09031936.00185114

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(5):395–409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Jin GY, Lynch D, Chawla A, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities in a CT lung cancer screening population: prevalence and progression rate. Radiology 2013; 268(2):563–571. doi:10.1148/radiol.13120816

- Southern BD, Scheraga RG, Yadav R. Managing interstitial lung disease detected on CT during lung cancer screening. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(1):55–65. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.14157

- King TE Jr, Schwarz MI, Brown K, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: relationship between histopathologic features and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164(5):1025–1032. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.6.2001056

- Lamas DJ, Kawut SM, Bagiella E, et al. Delayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184(7):842–847. doi:10.1164/rccm.201104-0668OC

- Jo HE, Glaspole I, Moodley Y, et al. Disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with mild physiological impairment: analysis from the Australian IPF registry. BMC Pulm Med 2018; 18(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12890-018-0575-y

- Yang IV, Schwartz DA. Epigenetics of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transl Res 2015; 165(1):48–60. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.011