User login

Professional Identity Formation During the COVID-19 Pandemic

In 1957, Merton wrote that the primary aim of medical education should be “to provide [learners] with a professional identity so that [they] come to think, act, and feel like a physician.”1 More than a half-century later, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching echoed his sentiments in its landmark examination of the United States medical education system, which produced four key recommendations for curricular reform, including explicitly addressing professional identity formation (PIF).2 PIF is a process by which a learner transforms into a physician with the values, dispositions, and aspirations of the physician community.3 It is now recognized as crucial to developing physicians who can deliver high-quality care.2

Major changes to the learning environment can impact PIF. For example, when the Accreditation Committee for Graduate Medical Education duty-hour restrictions were implemented in 2003, several educators were concerned that the changes may negatively affect resident PIF,4 whereas others saw an opportunity to refocus curricular efforts on PIF.5 Medical education is now in the midst of another radical change with the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Over the past several months, we have begun to understand the pandemic’s effects on medical education in terms of learner welfare, educational experiences/value, innovation, and assessment.6-8 However, little has been published on the pandemic’s effect on PIF.9 We explore the impact of COVID-19 on physicians’ PIF and identify strategies to support PIF in physicians and other healthcare professionals during times of crisis.

SOCIALIZATION AND COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

PIF is dynamic and nonlinear, occurring at every level of the medical education hierarchy (medical student, resident, fellow, attending).10 Emphasis on PIF has grown in recent years as a response to the limitations of behavior-based educational frameworks such as competency-based medical education (CBME),3 which focuses on what the learner can “do.” PIF moves beyond “doing” to consider who the learner “is.”11 PIF occurs at the individual level as learners progress through multiple distinct identity stages during their longitudinal formation10,12-14 but also at the level of the collective. Socialization plays a crucial role; thus, PIF is heavily influenced by the environment, context, and other individuals.10

Medicine can be conceptualized as a community of practice, which is a sustaining network of individuals who share knowledge, beliefs, values, and experiences related to a common practice or purpose.15,16 In a community of practice, learning is social, includes knowledge that is tacit to the community, and is situated within the context in which it will be applied. PIF involves learners moving from “legitimate peripheral participation,” whereby they are accepted as novice community members, to “full participation,” which involves gaining competence in relevant tasks and internalizing community principles to become full partners in the community.13 Critical to this process is exposure to socializing agents (eg, attendings, nurses, peers), observation of community interactions, experiential learning in the clinical environment, and access to role models.10,16 Immersion in the clinical environment with other community members is thus crucial to PIF. This is especially important, as “medicine” is not truly a single community, but rather a “landscape of communities,” each with its own identity.17 Learners must therefore be immersed in many different clinical environments to experience the various communities within our field.

COVID-19 CHANGING THE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

The pandemic is drastically altering the learning environment in medical education.8 Several institutions temporarily removed medical students from clinical rotations to reduce learner exposure and conserve personal protective equipment. Some residents were removed from nonessential clinical activities for similar reasons. Many attendings have been asked to work from home when not required to be present for clinical care duties. Common medical community activities, such as group meals and conferences, have been altered for physical distancing or simply canceled. Usual clinical care has rapidly evolved, with changes in rounding practices, a boon of telehealth, and cancellations of nonessential procedures. These necessary changes present constantly shifting grounds for anyone trying to integrate into a community and develop a professional identity.

Changes outside of the clinical learning environment are also affecting PIF. Social interactions, such as dinners and peer gatherings, occur via video conference or not at all. Most in-person contact happens with masks in place, physically distanced, and in smaller groups. Resident and student lounges are being modified to physically distance or reduce the number of occupants. There is often variable adherence, both intentional and unintentional, to physical distance and mask mandates, creating potential for confusion as learners try to internalize the values and norms of the medical community. Common professional rituals, such as white coat ceremonies, orientation events, and graduations, have been curtailed or canceled. Even experiences that are not commonly seen as social events but are important in the physician’s journey, such as the residency and fellowship application processes and standardized tests, are being transformed. These changes alter typical social patterns that are important in PIF and may adversely affect high-value social group interactions that serve as buffers against stressors during training.18

Finally, the pandemic has altered the timeline for many learners. Medical students at several institutions graduated early to join the workforce and help care for escalating numbers of patients during the pandemic.7 Some see the pandemic as a catalyst to move toward competency-based time-variable training, in which learners progress through training at variable rates depending on their individual performance and learning needs.19 These changes could shorten the amount of time some learners spend in a given role (eg, medical student, intern). In such situations, it is unclear whether a minimal maturational time is necessary for most learners to fully develop a professional identity.

SUPPORTING PIF DURING THE PANDEMIC

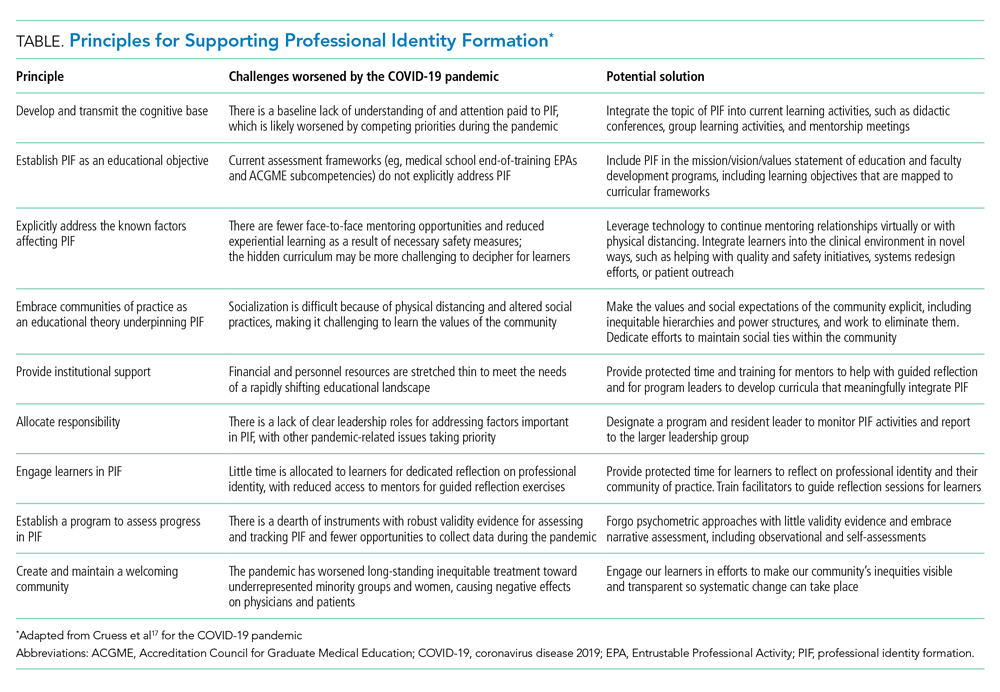

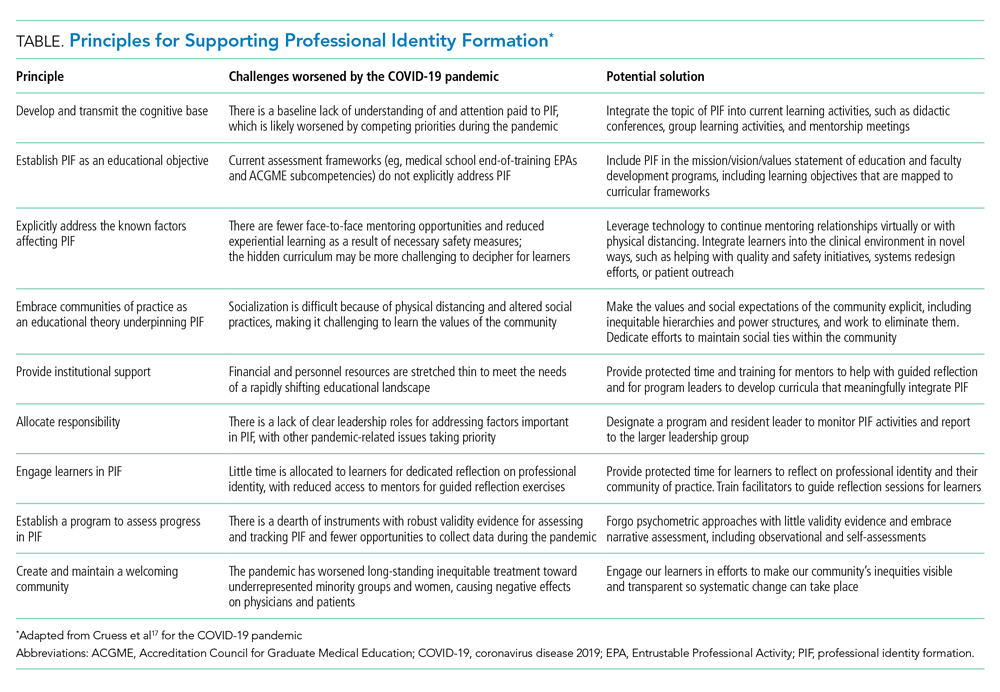

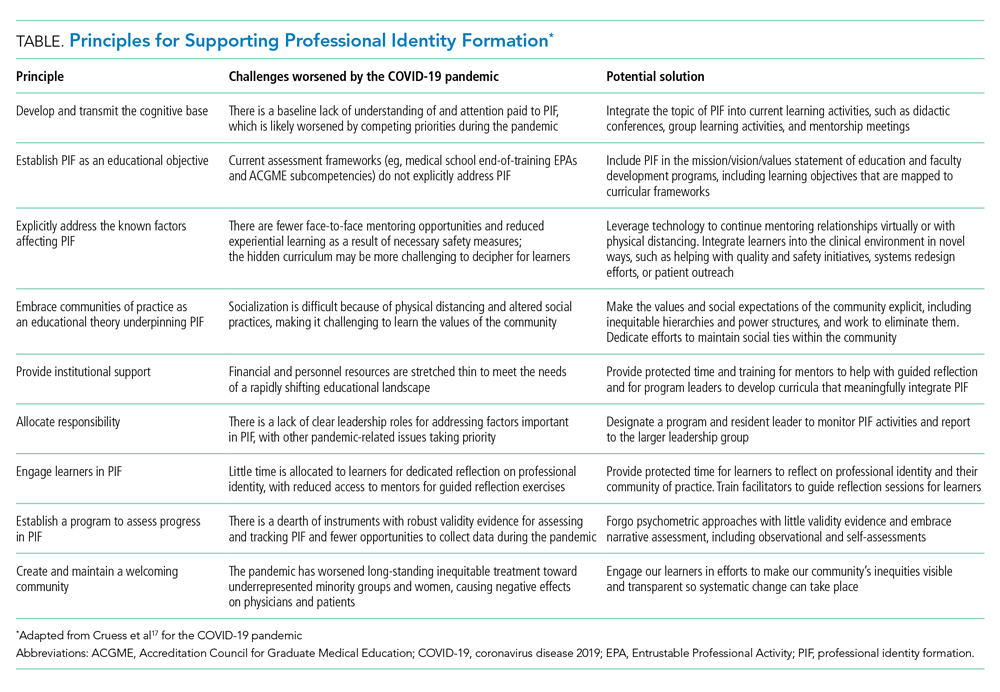

In 2019, Cruess et al published general principles for supporting PIF,17 which have been used to support PIF during the COVID-19 pandemic.20 In the Table, we describe these principles and provide examples of how to implement them in the context of the pandemic. We believe these principles are applicable for PIF in undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, and faculty development programs. A common thread throughout the principles is that PIF is not a process that should be left to chance, but rather explicitly nurtured through systematic support and curricular initiatives.5 This may be challenging while the COVID-19 pandemic is sapping financial resources and requiring rapid changes to clinical systems, but given the central role PIF plays in physician development, it should be prioritized by educational leaders.

CREATING AND MAINTAINING A WELCOMING COMMUNITY: AN OPPORTUNITY

One of the final principles from Cruess et al is to create and maintain a welcoming community.17 This prompts questions such as: Is our community welcoming to everyone, where “everyone” really does mean everyone? Like other social structures, communities of practice tend to perpetuate existing power structures and inequities.17 It is no secret that medicine, like other professions, is riddled with inequities and bias based on factors such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status.21-23 The COVID-19 pandemic is likely exacerbating these inequities, such as the adverse impacts that are specifically affecting women physicians, who take on a disproportionate share of the child care at home.23 These biases impact not only the members of our professional community but also our patients, contributing to disparities in care and outcomes.

Physicians who have received inequitable treatment have laid bare the ways in which our communities of practice are failing them, and also outlined a better path on which to move forward.21,23 In addition to recruitment practices that promote diversity, meaningful programs should be developed to support inclusion, equity (in recognition, support, compensation), retention, and advancement. The disruption caused by COVID-19 can be a catalyst for this change. By taking this moment of crisis to examine the values and norms of medicine and how we systematically perpetuate harmful inequities and biases, we have an opportunity to deliberately rebuild our community of practice in a manner that helps shape the next generation’s professional identities to be better than we have been. This should always be the aim of education.

1. Merton RK. Some Preliminaries to a Sociology of Medical Education. Harvard University Press; 1957.

2. Cooke M, Irby DM, O’Brien BC. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. Jossey-Bass; 2010.

3. Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the clouds: three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1606-1611. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001190

4. Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Effect of residency duty-hour limits: views of key clinical faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1487-1492. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1487

5. Schumacher DJ, Slovin SR, Riebschleger MP, Englander R, Hicks PJ, Carraccio C. Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883-888. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318257d57d

6. Anderson ML, Turbow S, Willgerodt MA, Ruhnke GW. Education in a crisis: the opportunity of our lives. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):287-291. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3431

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Woolliscroft JO. Innovation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1140-1142. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003402

9. Cullum RJ, Shaughnessy A, Mayat NY, Brown ME. Identity in lockdown: supporting primary care professional identity development in the COVID-19 generation. Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(4):200-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2020.1779616

10. Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

11. Al‐Eraky M, Marei H. A fresh look at Miller’s pyramid: assessment at the ‘Is’ and ‘Do’ levels. Med Educ. 2016;50(12):1253-1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13101

12. Forsythe GB. Identity development in professional education. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S112-S117. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510001-0002913.

13. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718-725. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

14. Kegan R. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Harvard University Press; 1982.

15. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

16. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press; 1991.

17. Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641-649. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260

18. Mavor KI, McNeill KG, Anderson K, Kerr A, O’Reilly E, Platow MJ. Beyond prevalence to process: the role of self and identity in medical student well‐being. Med Educ. 2014;48(4):351-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12375

19. Goldhamer MEJ, Pusic MV, Co JPT, Weinstein DF. Can COVID catalyze an educational transformation? Competency-based advancement in a crisis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1003-1005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018570

20. Stetson GV, Kryzhanovskaya IV, Lomen‐Hoerth C, Hauer KE. Professional identity formation in disorienting times. Med Educ. 2020;54(8):765-766. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14202

21. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

22. Beagan BL. Everyday classism in medical school: experiencing marginality and resistance. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):777-784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02225.x

23. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al. Collateral damage: how COVID-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

In 1957, Merton wrote that the primary aim of medical education should be “to provide [learners] with a professional identity so that [they] come to think, act, and feel like a physician.”1 More than a half-century later, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching echoed his sentiments in its landmark examination of the United States medical education system, which produced four key recommendations for curricular reform, including explicitly addressing professional identity formation (PIF).2 PIF is a process by which a learner transforms into a physician with the values, dispositions, and aspirations of the physician community.3 It is now recognized as crucial to developing physicians who can deliver high-quality care.2

Major changes to the learning environment can impact PIF. For example, when the Accreditation Committee for Graduate Medical Education duty-hour restrictions were implemented in 2003, several educators were concerned that the changes may negatively affect resident PIF,4 whereas others saw an opportunity to refocus curricular efforts on PIF.5 Medical education is now in the midst of another radical change with the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Over the past several months, we have begun to understand the pandemic’s effects on medical education in terms of learner welfare, educational experiences/value, innovation, and assessment.6-8 However, little has been published on the pandemic’s effect on PIF.9 We explore the impact of COVID-19 on physicians’ PIF and identify strategies to support PIF in physicians and other healthcare professionals during times of crisis.

SOCIALIZATION AND COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

PIF is dynamic and nonlinear, occurring at every level of the medical education hierarchy (medical student, resident, fellow, attending).10 Emphasis on PIF has grown in recent years as a response to the limitations of behavior-based educational frameworks such as competency-based medical education (CBME),3 which focuses on what the learner can “do.” PIF moves beyond “doing” to consider who the learner “is.”11 PIF occurs at the individual level as learners progress through multiple distinct identity stages during their longitudinal formation10,12-14 but also at the level of the collective. Socialization plays a crucial role; thus, PIF is heavily influenced by the environment, context, and other individuals.10

Medicine can be conceptualized as a community of practice, which is a sustaining network of individuals who share knowledge, beliefs, values, and experiences related to a common practice or purpose.15,16 In a community of practice, learning is social, includes knowledge that is tacit to the community, and is situated within the context in which it will be applied. PIF involves learners moving from “legitimate peripheral participation,” whereby they are accepted as novice community members, to “full participation,” which involves gaining competence in relevant tasks and internalizing community principles to become full partners in the community.13 Critical to this process is exposure to socializing agents (eg, attendings, nurses, peers), observation of community interactions, experiential learning in the clinical environment, and access to role models.10,16 Immersion in the clinical environment with other community members is thus crucial to PIF. This is especially important, as “medicine” is not truly a single community, but rather a “landscape of communities,” each with its own identity.17 Learners must therefore be immersed in many different clinical environments to experience the various communities within our field.

COVID-19 CHANGING THE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

The pandemic is drastically altering the learning environment in medical education.8 Several institutions temporarily removed medical students from clinical rotations to reduce learner exposure and conserve personal protective equipment. Some residents were removed from nonessential clinical activities for similar reasons. Many attendings have been asked to work from home when not required to be present for clinical care duties. Common medical community activities, such as group meals and conferences, have been altered for physical distancing or simply canceled. Usual clinical care has rapidly evolved, with changes in rounding practices, a boon of telehealth, and cancellations of nonessential procedures. These necessary changes present constantly shifting grounds for anyone trying to integrate into a community and develop a professional identity.

Changes outside of the clinical learning environment are also affecting PIF. Social interactions, such as dinners and peer gatherings, occur via video conference or not at all. Most in-person contact happens with masks in place, physically distanced, and in smaller groups. Resident and student lounges are being modified to physically distance or reduce the number of occupants. There is often variable adherence, both intentional and unintentional, to physical distance and mask mandates, creating potential for confusion as learners try to internalize the values and norms of the medical community. Common professional rituals, such as white coat ceremonies, orientation events, and graduations, have been curtailed or canceled. Even experiences that are not commonly seen as social events but are important in the physician’s journey, such as the residency and fellowship application processes and standardized tests, are being transformed. These changes alter typical social patterns that are important in PIF and may adversely affect high-value social group interactions that serve as buffers against stressors during training.18

Finally, the pandemic has altered the timeline for many learners. Medical students at several institutions graduated early to join the workforce and help care for escalating numbers of patients during the pandemic.7 Some see the pandemic as a catalyst to move toward competency-based time-variable training, in which learners progress through training at variable rates depending on their individual performance and learning needs.19 These changes could shorten the amount of time some learners spend in a given role (eg, medical student, intern). In such situations, it is unclear whether a minimal maturational time is necessary for most learners to fully develop a professional identity.

SUPPORTING PIF DURING THE PANDEMIC

In 2019, Cruess et al published general principles for supporting PIF,17 which have been used to support PIF during the COVID-19 pandemic.20 In the Table, we describe these principles and provide examples of how to implement them in the context of the pandemic. We believe these principles are applicable for PIF in undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, and faculty development programs. A common thread throughout the principles is that PIF is not a process that should be left to chance, but rather explicitly nurtured through systematic support and curricular initiatives.5 This may be challenging while the COVID-19 pandemic is sapping financial resources and requiring rapid changes to clinical systems, but given the central role PIF plays in physician development, it should be prioritized by educational leaders.

CREATING AND MAINTAINING A WELCOMING COMMUNITY: AN OPPORTUNITY

One of the final principles from Cruess et al is to create and maintain a welcoming community.17 This prompts questions such as: Is our community welcoming to everyone, where “everyone” really does mean everyone? Like other social structures, communities of practice tend to perpetuate existing power structures and inequities.17 It is no secret that medicine, like other professions, is riddled with inequities and bias based on factors such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status.21-23 The COVID-19 pandemic is likely exacerbating these inequities, such as the adverse impacts that are specifically affecting women physicians, who take on a disproportionate share of the child care at home.23 These biases impact not only the members of our professional community but also our patients, contributing to disparities in care and outcomes.

Physicians who have received inequitable treatment have laid bare the ways in which our communities of practice are failing them, and also outlined a better path on which to move forward.21,23 In addition to recruitment practices that promote diversity, meaningful programs should be developed to support inclusion, equity (in recognition, support, compensation), retention, and advancement. The disruption caused by COVID-19 can be a catalyst for this change. By taking this moment of crisis to examine the values and norms of medicine and how we systematically perpetuate harmful inequities and biases, we have an opportunity to deliberately rebuild our community of practice in a manner that helps shape the next generation’s professional identities to be better than we have been. This should always be the aim of education.

In 1957, Merton wrote that the primary aim of medical education should be “to provide [learners] with a professional identity so that [they] come to think, act, and feel like a physician.”1 More than a half-century later, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching echoed his sentiments in its landmark examination of the United States medical education system, which produced four key recommendations for curricular reform, including explicitly addressing professional identity formation (PIF).2 PIF is a process by which a learner transforms into a physician with the values, dispositions, and aspirations of the physician community.3 It is now recognized as crucial to developing physicians who can deliver high-quality care.2

Major changes to the learning environment can impact PIF. For example, when the Accreditation Committee for Graduate Medical Education duty-hour restrictions were implemented in 2003, several educators were concerned that the changes may negatively affect resident PIF,4 whereas others saw an opportunity to refocus curricular efforts on PIF.5 Medical education is now in the midst of another radical change with the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Over the past several months, we have begun to understand the pandemic’s effects on medical education in terms of learner welfare, educational experiences/value, innovation, and assessment.6-8 However, little has been published on the pandemic’s effect on PIF.9 We explore the impact of COVID-19 on physicians’ PIF and identify strategies to support PIF in physicians and other healthcare professionals during times of crisis.

SOCIALIZATION AND COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

PIF is dynamic and nonlinear, occurring at every level of the medical education hierarchy (medical student, resident, fellow, attending).10 Emphasis on PIF has grown in recent years as a response to the limitations of behavior-based educational frameworks such as competency-based medical education (CBME),3 which focuses on what the learner can “do.” PIF moves beyond “doing” to consider who the learner “is.”11 PIF occurs at the individual level as learners progress through multiple distinct identity stages during their longitudinal formation10,12-14 but also at the level of the collective. Socialization plays a crucial role; thus, PIF is heavily influenced by the environment, context, and other individuals.10

Medicine can be conceptualized as a community of practice, which is a sustaining network of individuals who share knowledge, beliefs, values, and experiences related to a common practice or purpose.15,16 In a community of practice, learning is social, includes knowledge that is tacit to the community, and is situated within the context in which it will be applied. PIF involves learners moving from “legitimate peripheral participation,” whereby they are accepted as novice community members, to “full participation,” which involves gaining competence in relevant tasks and internalizing community principles to become full partners in the community.13 Critical to this process is exposure to socializing agents (eg, attendings, nurses, peers), observation of community interactions, experiential learning in the clinical environment, and access to role models.10,16 Immersion in the clinical environment with other community members is thus crucial to PIF. This is especially important, as “medicine” is not truly a single community, but rather a “landscape of communities,” each with its own identity.17 Learners must therefore be immersed in many different clinical environments to experience the various communities within our field.

COVID-19 CHANGING THE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

The pandemic is drastically altering the learning environment in medical education.8 Several institutions temporarily removed medical students from clinical rotations to reduce learner exposure and conserve personal protective equipment. Some residents were removed from nonessential clinical activities for similar reasons. Many attendings have been asked to work from home when not required to be present for clinical care duties. Common medical community activities, such as group meals and conferences, have been altered for physical distancing or simply canceled. Usual clinical care has rapidly evolved, with changes in rounding practices, a boon of telehealth, and cancellations of nonessential procedures. These necessary changes present constantly shifting grounds for anyone trying to integrate into a community and develop a professional identity.

Changes outside of the clinical learning environment are also affecting PIF. Social interactions, such as dinners and peer gatherings, occur via video conference or not at all. Most in-person contact happens with masks in place, physically distanced, and in smaller groups. Resident and student lounges are being modified to physically distance or reduce the number of occupants. There is often variable adherence, both intentional and unintentional, to physical distance and mask mandates, creating potential for confusion as learners try to internalize the values and norms of the medical community. Common professional rituals, such as white coat ceremonies, orientation events, and graduations, have been curtailed or canceled. Even experiences that are not commonly seen as social events but are important in the physician’s journey, such as the residency and fellowship application processes and standardized tests, are being transformed. These changes alter typical social patterns that are important in PIF and may adversely affect high-value social group interactions that serve as buffers against stressors during training.18

Finally, the pandemic has altered the timeline for many learners. Medical students at several institutions graduated early to join the workforce and help care for escalating numbers of patients during the pandemic.7 Some see the pandemic as a catalyst to move toward competency-based time-variable training, in which learners progress through training at variable rates depending on their individual performance and learning needs.19 These changes could shorten the amount of time some learners spend in a given role (eg, medical student, intern). In such situations, it is unclear whether a minimal maturational time is necessary for most learners to fully develop a professional identity.

SUPPORTING PIF DURING THE PANDEMIC

In 2019, Cruess et al published general principles for supporting PIF,17 which have been used to support PIF during the COVID-19 pandemic.20 In the Table, we describe these principles and provide examples of how to implement them in the context of the pandemic. We believe these principles are applicable for PIF in undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, and faculty development programs. A common thread throughout the principles is that PIF is not a process that should be left to chance, but rather explicitly nurtured through systematic support and curricular initiatives.5 This may be challenging while the COVID-19 pandemic is sapping financial resources and requiring rapid changes to clinical systems, but given the central role PIF plays in physician development, it should be prioritized by educational leaders.

CREATING AND MAINTAINING A WELCOMING COMMUNITY: AN OPPORTUNITY

One of the final principles from Cruess et al is to create and maintain a welcoming community.17 This prompts questions such as: Is our community welcoming to everyone, where “everyone” really does mean everyone? Like other social structures, communities of practice tend to perpetuate existing power structures and inequities.17 It is no secret that medicine, like other professions, is riddled with inequities and bias based on factors such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status.21-23 The COVID-19 pandemic is likely exacerbating these inequities, such as the adverse impacts that are specifically affecting women physicians, who take on a disproportionate share of the child care at home.23 These biases impact not only the members of our professional community but also our patients, contributing to disparities in care and outcomes.

Physicians who have received inequitable treatment have laid bare the ways in which our communities of practice are failing them, and also outlined a better path on which to move forward.21,23 In addition to recruitment practices that promote diversity, meaningful programs should be developed to support inclusion, equity (in recognition, support, compensation), retention, and advancement. The disruption caused by COVID-19 can be a catalyst for this change. By taking this moment of crisis to examine the values and norms of medicine and how we systematically perpetuate harmful inequities and biases, we have an opportunity to deliberately rebuild our community of practice in a manner that helps shape the next generation’s professional identities to be better than we have been. This should always be the aim of education.

1. Merton RK. Some Preliminaries to a Sociology of Medical Education. Harvard University Press; 1957.

2. Cooke M, Irby DM, O’Brien BC. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. Jossey-Bass; 2010.

3. Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the clouds: three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1606-1611. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001190

4. Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Effect of residency duty-hour limits: views of key clinical faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1487-1492. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1487

5. Schumacher DJ, Slovin SR, Riebschleger MP, Englander R, Hicks PJ, Carraccio C. Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883-888. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318257d57d

6. Anderson ML, Turbow S, Willgerodt MA, Ruhnke GW. Education in a crisis: the opportunity of our lives. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):287-291. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3431

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Woolliscroft JO. Innovation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1140-1142. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003402

9. Cullum RJ, Shaughnessy A, Mayat NY, Brown ME. Identity in lockdown: supporting primary care professional identity development in the COVID-19 generation. Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(4):200-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2020.1779616

10. Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

11. Al‐Eraky M, Marei H. A fresh look at Miller’s pyramid: assessment at the ‘Is’ and ‘Do’ levels. Med Educ. 2016;50(12):1253-1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13101

12. Forsythe GB. Identity development in professional education. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S112-S117. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510001-0002913.

13. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718-725. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

14. Kegan R. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Harvard University Press; 1982.

15. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

16. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press; 1991.

17. Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641-649. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260

18. Mavor KI, McNeill KG, Anderson K, Kerr A, O’Reilly E, Platow MJ. Beyond prevalence to process: the role of self and identity in medical student well‐being. Med Educ. 2014;48(4):351-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12375

19. Goldhamer MEJ, Pusic MV, Co JPT, Weinstein DF. Can COVID catalyze an educational transformation? Competency-based advancement in a crisis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1003-1005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018570

20. Stetson GV, Kryzhanovskaya IV, Lomen‐Hoerth C, Hauer KE. Professional identity formation in disorienting times. Med Educ. 2020;54(8):765-766. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14202

21. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

22. Beagan BL. Everyday classism in medical school: experiencing marginality and resistance. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):777-784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02225.x

23. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al. Collateral damage: how COVID-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

1. Merton RK. Some Preliminaries to a Sociology of Medical Education. Harvard University Press; 1957.

2. Cooke M, Irby DM, O’Brien BC. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. Jossey-Bass; 2010.

3. Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the clouds: three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1606-1611. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001190

4. Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Effect of residency duty-hour limits: views of key clinical faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1487-1492. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1487

5. Schumacher DJ, Slovin SR, Riebschleger MP, Englander R, Hicks PJ, Carraccio C. Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883-888. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318257d57d

6. Anderson ML, Turbow S, Willgerodt MA, Ruhnke GW. Education in a crisis: the opportunity of our lives. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):287-291. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3431

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Woolliscroft JO. Innovation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1140-1142. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003402

9. Cullum RJ, Shaughnessy A, Mayat NY, Brown ME. Identity in lockdown: supporting primary care professional identity development in the COVID-19 generation. Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(4):200-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2020.1779616

10. Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

11. Al‐Eraky M, Marei H. A fresh look at Miller’s pyramid: assessment at the ‘Is’ and ‘Do’ levels. Med Educ. 2016;50(12):1253-1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13101

12. Forsythe GB. Identity development in professional education. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S112-S117. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510001-0002913.

13. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718-725. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

14. Kegan R. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Harvard University Press; 1982.

15. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

16. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press; 1991.

17. Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641-649. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260

18. Mavor KI, McNeill KG, Anderson K, Kerr A, O’Reilly E, Platow MJ. Beyond prevalence to process: the role of self and identity in medical student well‐being. Med Educ. 2014;48(4):351-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12375

19. Goldhamer MEJ, Pusic MV, Co JPT, Weinstein DF. Can COVID catalyze an educational transformation? Competency-based advancement in a crisis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1003-1005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018570

20. Stetson GV, Kryzhanovskaya IV, Lomen‐Hoerth C, Hauer KE. Professional identity formation in disorienting times. Med Educ. 2020;54(8):765-766. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14202

21. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

22. Beagan BL. Everyday classism in medical school: experiencing marginality and resistance. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):777-784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02225.x

23. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al. Collateral damage: how COVID-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine