User login

Violaceous-Purpuric Targetoid Macules and Patches With Bullae and Ulceration

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome (Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis)

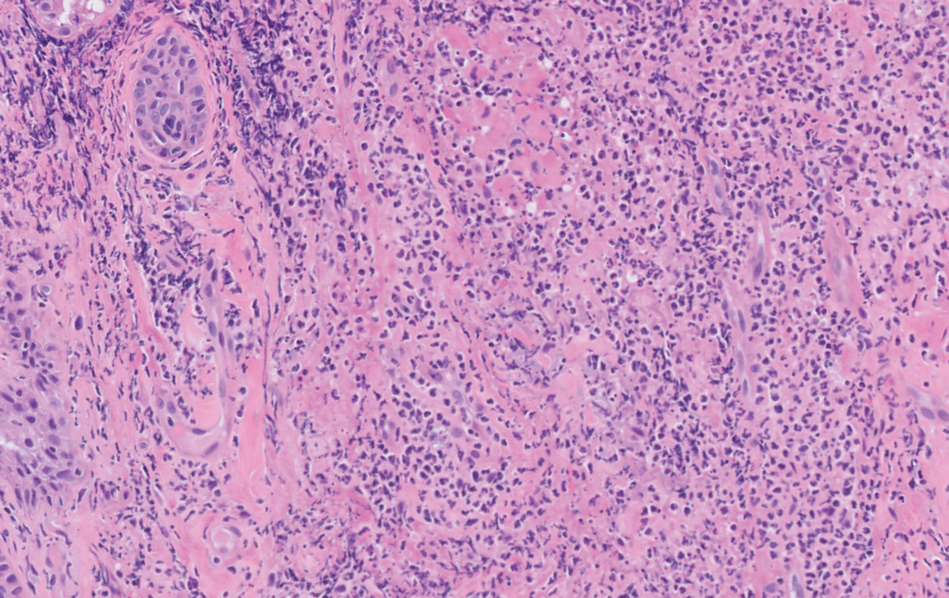

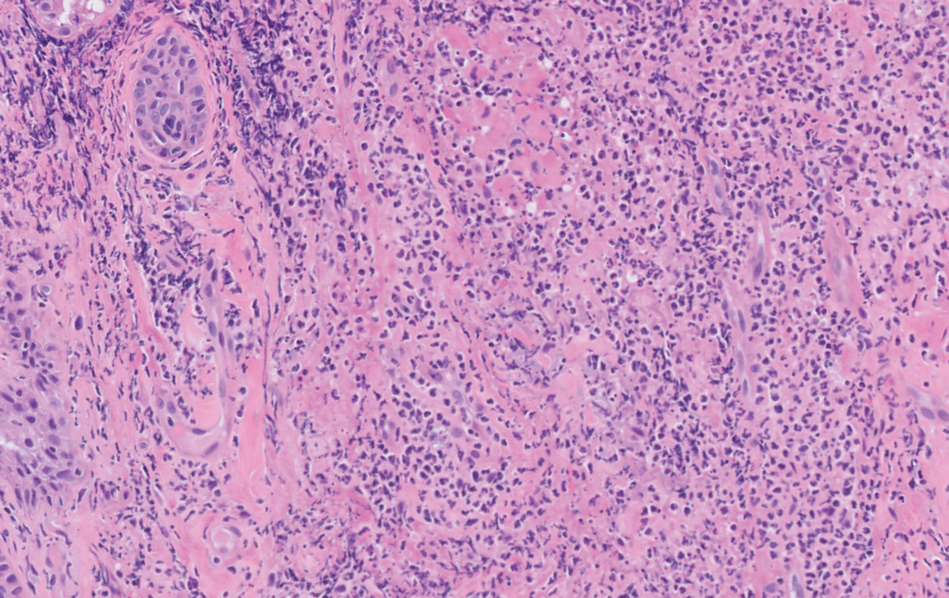

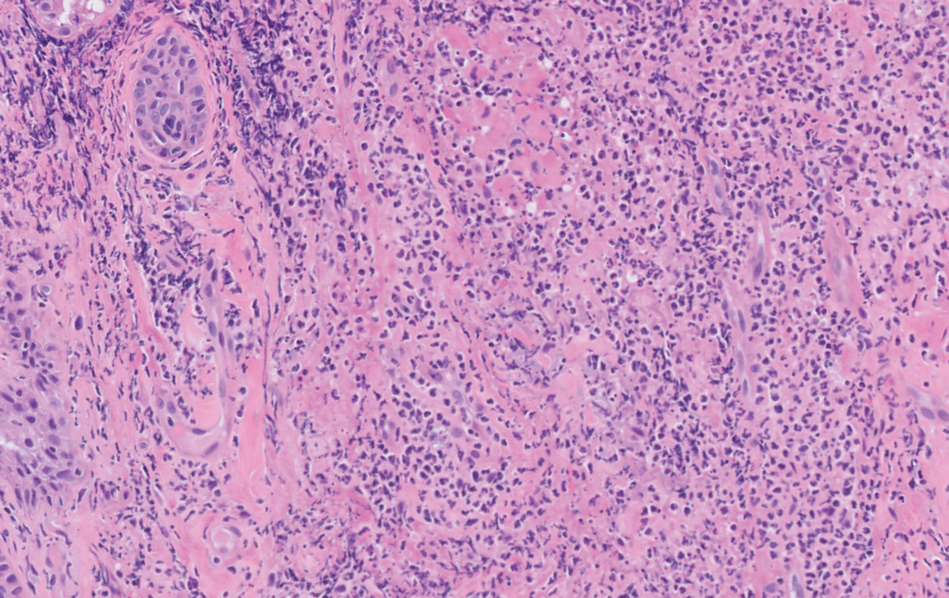

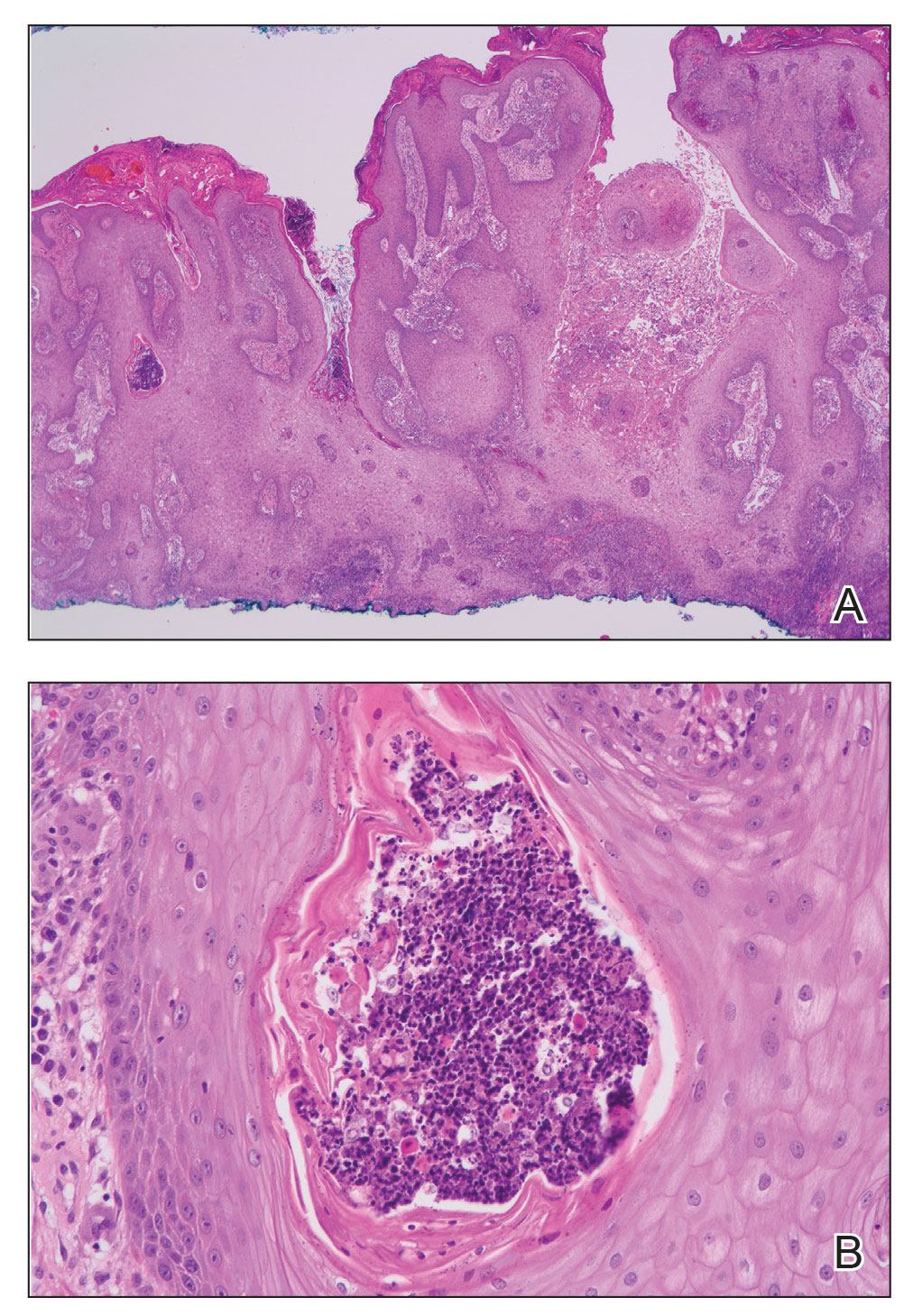

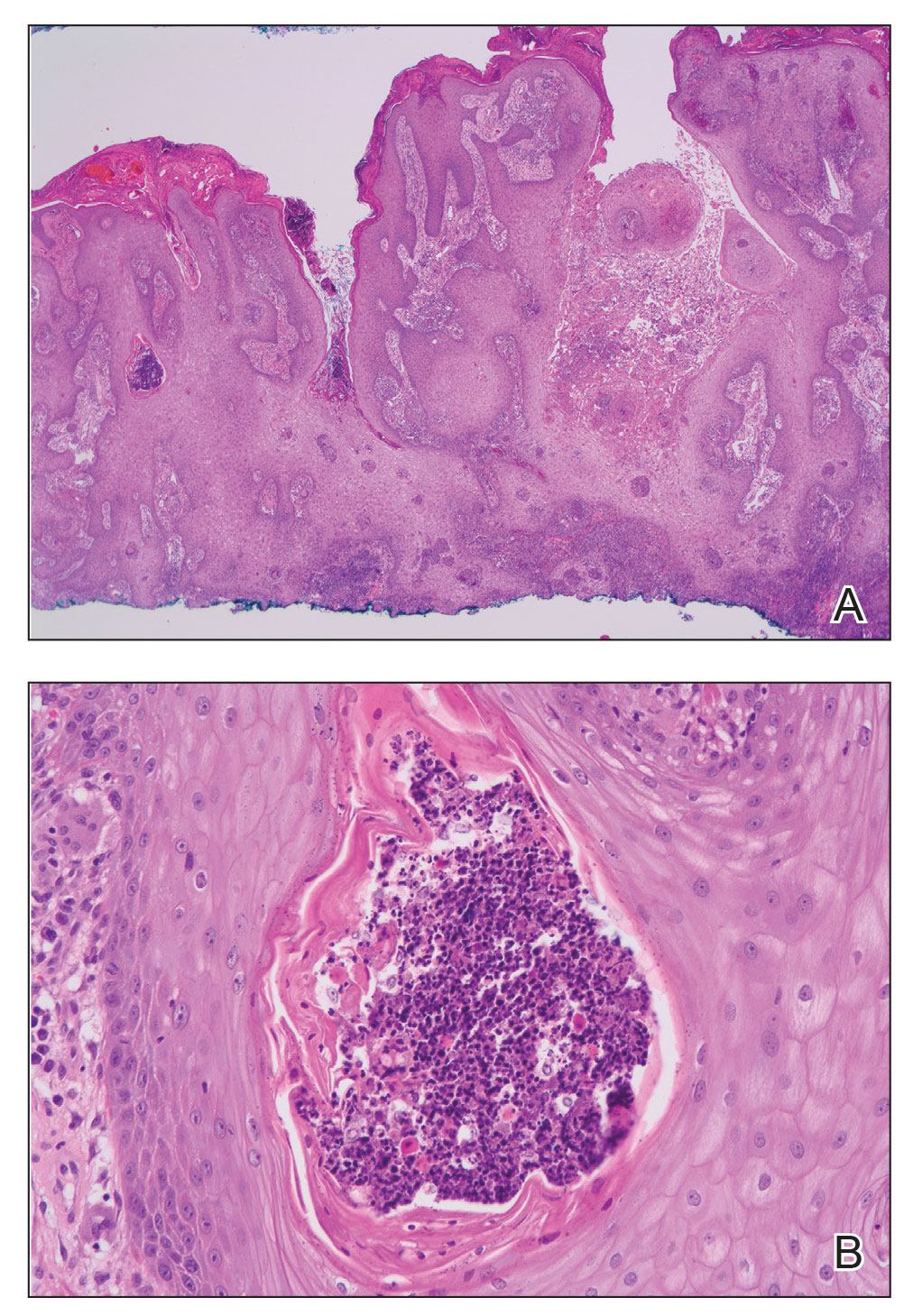

A skin biopsy of the right lower extremity demonstrated diffuse interstitial, perivascular, and periadnexal neutrophilic dermal infiltrate in the reticular dermis (Figure 1), consistent with a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome without evidence of leukemia cutis or infection. The firm erythematous papulonodules with follicular accentuation on the face (Figure 2) also were confirmed as Sweet syndrome on histopathology. Concern for leukemic transformation was confirmed with bone biopsy revealing acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Our patient began a short course of prednisone, and the cutaneous lesions improved during hospitalization; however, he was lost to follow-up.

Sweet syndrome (also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is a rare inflammatory skin condition typically characterized by asymmetric, painful, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules involving the arms, face, and neck.1 It most commonly occurs in women and typically presents in patients aged 47 to 57 years. Although the pathogenesis of neutrophilic dermatoses is not completely understood, they are believed to be due to altered expression of inflammatory cytokines, irregular neutrophil function, and a genetic predisposition.2 There are 3 main categories of Sweet syndrome: classical (or idiopathic), drug induced, and malignancy associated.1 The lesions associated with Sweet syndrome vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters and may be annular or targetoid in the later stages. They also may form bullae and ulcerate. Fever, leukocytosis, and elevated acute-phase reactants also are common on presentation.1 Histopathologic analysis demonstrates an intense neutrophilic infiltrate within the reticular dermis with marked leukocytoclasia. Admixed within the neutrophil polymorphs are variable numbers of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Edema in the upper dermis also is characteristic.3 The exact pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome has yet to be elucidated but may involve a combination of cytokine dysregulation, hypersensitivity reactions, and genetics.4 Our case demonstrates 3 distinct morphologies of Sweet syndrome in a single patient, including classic edematous plaques, agminated targetoid plaques, and ulceration. Based on the clinical presentation, diagnostic workup for an undiagnosed malignancy was warranted, which confirmed AML. The malignancy-associated form of Sweet syndrome accounts for a substantial portion of cases, with approximately 21% of patients diagnosed with Sweet syndrome having an underlying malignancy, commonly a hematologic malignancy or myeloproliferative disorder with AML being the most common.1

The differential diagnosis for Sweet syndrome includes cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, which commonly presents with symmetric palpable purpura of the legs. Lesions may be round, port wine–colored plaques and even may form ulcers, vesicles, and targetoid lesions. However, skin biopsy shows polymorphonuclear infiltrate affecting postcapillary venules, fibrinoid deposits, and extravasation of red blood cells.5 Leukemia cutis describes any type of leukemia that manifests in the skin. It typically presents as violaceous or red-brown papules, nodules, and plaques most commonly on the legs. Histopathology varies by immunophenotype but generally demonstrates perivascular or periadnexal involvement or a diffuse, interstitial, or nodular infiltrate of the dermis or subcutis.6 Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis describes an aseptic neutrophilic infiltration around eccrine coils and glands. It may present as papules or plaques that usually are erythematous but also may be pigmented. Lesions can be asymptomatic or painful as in Sweet syndrome and are distributed proximally or on the distal extremities. Histopathologic examination demonstrates the degeneration of the eccrine gland and neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrates.7 Lastly, necrotizing fasciitis is a life-threatening infection of the deep soft tissue and fascia, classically caused by group A Streptococcus. The infected site may have erythema, tenderness, fluctuance, necrosis, and bullae.8 Although our patient had a fever, he did not display the tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnea, and rapid deterioration that is common in necrotizing fasciitis.

Sweet syndrome may present with various morphologies within the same patient. Painful, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, nodules, bullae, and ulcers may be seen. A workup for an underlying malignancy may be warranted based on clinical presentation. Most patients have a rapid and dramatic response to systemic corticosteroids.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/J .JAAD.2017.11.064

- Pulido-Pérez A, Bergon-Sendin M, Sacks CA. Images in clinical medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;16:382. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1911025

- Marzano AV, Hilbrands L, Le ST, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:414. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00414

- Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:299-306. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0076-6

- Hee Cho-Vega J, Jeffrey Medeiros L, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142. doi:10.1309/WYAC YWF6NGM3WBRT

- Bachmeyer C, Aractingi S. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:319-330. doi:10.1016/S0738-081X(99)00123-6

- Shimizu T, Tokuda Y. Necrotizing fasciitis. Intern Med. 2010; 49:1051-1057. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2964

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome (Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis)

A skin biopsy of the right lower extremity demonstrated diffuse interstitial, perivascular, and periadnexal neutrophilic dermal infiltrate in the reticular dermis (Figure 1), consistent with a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome without evidence of leukemia cutis or infection. The firm erythematous papulonodules with follicular accentuation on the face (Figure 2) also were confirmed as Sweet syndrome on histopathology. Concern for leukemic transformation was confirmed with bone biopsy revealing acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Our patient began a short course of prednisone, and the cutaneous lesions improved during hospitalization; however, he was lost to follow-up.

Sweet syndrome (also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is a rare inflammatory skin condition typically characterized by asymmetric, painful, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules involving the arms, face, and neck.1 It most commonly occurs in women and typically presents in patients aged 47 to 57 years. Although the pathogenesis of neutrophilic dermatoses is not completely understood, they are believed to be due to altered expression of inflammatory cytokines, irregular neutrophil function, and a genetic predisposition.2 There are 3 main categories of Sweet syndrome: classical (or idiopathic), drug induced, and malignancy associated.1 The lesions associated with Sweet syndrome vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters and may be annular or targetoid in the later stages. They also may form bullae and ulcerate. Fever, leukocytosis, and elevated acute-phase reactants also are common on presentation.1 Histopathologic analysis demonstrates an intense neutrophilic infiltrate within the reticular dermis with marked leukocytoclasia. Admixed within the neutrophil polymorphs are variable numbers of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Edema in the upper dermis also is characteristic.3 The exact pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome has yet to be elucidated but may involve a combination of cytokine dysregulation, hypersensitivity reactions, and genetics.4 Our case demonstrates 3 distinct morphologies of Sweet syndrome in a single patient, including classic edematous plaques, agminated targetoid plaques, and ulceration. Based on the clinical presentation, diagnostic workup for an undiagnosed malignancy was warranted, which confirmed AML. The malignancy-associated form of Sweet syndrome accounts for a substantial portion of cases, with approximately 21% of patients diagnosed with Sweet syndrome having an underlying malignancy, commonly a hematologic malignancy or myeloproliferative disorder with AML being the most common.1

The differential diagnosis for Sweet syndrome includes cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, which commonly presents with symmetric palpable purpura of the legs. Lesions may be round, port wine–colored plaques and even may form ulcers, vesicles, and targetoid lesions. However, skin biopsy shows polymorphonuclear infiltrate affecting postcapillary venules, fibrinoid deposits, and extravasation of red blood cells.5 Leukemia cutis describes any type of leukemia that manifests in the skin. It typically presents as violaceous or red-brown papules, nodules, and plaques most commonly on the legs. Histopathology varies by immunophenotype but generally demonstrates perivascular or periadnexal involvement or a diffuse, interstitial, or nodular infiltrate of the dermis or subcutis.6 Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis describes an aseptic neutrophilic infiltration around eccrine coils and glands. It may present as papules or plaques that usually are erythematous but also may be pigmented. Lesions can be asymptomatic or painful as in Sweet syndrome and are distributed proximally or on the distal extremities. Histopathologic examination demonstrates the degeneration of the eccrine gland and neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrates.7 Lastly, necrotizing fasciitis is a life-threatening infection of the deep soft tissue and fascia, classically caused by group A Streptococcus. The infected site may have erythema, tenderness, fluctuance, necrosis, and bullae.8 Although our patient had a fever, he did not display the tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnea, and rapid deterioration that is common in necrotizing fasciitis.

Sweet syndrome may present with various morphologies within the same patient. Painful, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, nodules, bullae, and ulcers may be seen. A workup for an underlying malignancy may be warranted based on clinical presentation. Most patients have a rapid and dramatic response to systemic corticosteroids.

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome (Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis)

A skin biopsy of the right lower extremity demonstrated diffuse interstitial, perivascular, and periadnexal neutrophilic dermal infiltrate in the reticular dermis (Figure 1), consistent with a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome without evidence of leukemia cutis or infection. The firm erythematous papulonodules with follicular accentuation on the face (Figure 2) also were confirmed as Sweet syndrome on histopathology. Concern for leukemic transformation was confirmed with bone biopsy revealing acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Our patient began a short course of prednisone, and the cutaneous lesions improved during hospitalization; however, he was lost to follow-up.

Sweet syndrome (also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is a rare inflammatory skin condition typically characterized by asymmetric, painful, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules involving the arms, face, and neck.1 It most commonly occurs in women and typically presents in patients aged 47 to 57 years. Although the pathogenesis of neutrophilic dermatoses is not completely understood, they are believed to be due to altered expression of inflammatory cytokines, irregular neutrophil function, and a genetic predisposition.2 There are 3 main categories of Sweet syndrome: classical (or idiopathic), drug induced, and malignancy associated.1 The lesions associated with Sweet syndrome vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters and may be annular or targetoid in the later stages. They also may form bullae and ulcerate. Fever, leukocytosis, and elevated acute-phase reactants also are common on presentation.1 Histopathologic analysis demonstrates an intense neutrophilic infiltrate within the reticular dermis with marked leukocytoclasia. Admixed within the neutrophil polymorphs are variable numbers of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Edema in the upper dermis also is characteristic.3 The exact pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome has yet to be elucidated but may involve a combination of cytokine dysregulation, hypersensitivity reactions, and genetics.4 Our case demonstrates 3 distinct morphologies of Sweet syndrome in a single patient, including classic edematous plaques, agminated targetoid plaques, and ulceration. Based on the clinical presentation, diagnostic workup for an undiagnosed malignancy was warranted, which confirmed AML. The malignancy-associated form of Sweet syndrome accounts for a substantial portion of cases, with approximately 21% of patients diagnosed with Sweet syndrome having an underlying malignancy, commonly a hematologic malignancy or myeloproliferative disorder with AML being the most common.1

The differential diagnosis for Sweet syndrome includes cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, which commonly presents with symmetric palpable purpura of the legs. Lesions may be round, port wine–colored plaques and even may form ulcers, vesicles, and targetoid lesions. However, skin biopsy shows polymorphonuclear infiltrate affecting postcapillary venules, fibrinoid deposits, and extravasation of red blood cells.5 Leukemia cutis describes any type of leukemia that manifests in the skin. It typically presents as violaceous or red-brown papules, nodules, and plaques most commonly on the legs. Histopathology varies by immunophenotype but generally demonstrates perivascular or periadnexal involvement or a diffuse, interstitial, or nodular infiltrate of the dermis or subcutis.6 Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis describes an aseptic neutrophilic infiltration around eccrine coils and glands. It may present as papules or plaques that usually are erythematous but also may be pigmented. Lesions can be asymptomatic or painful as in Sweet syndrome and are distributed proximally or on the distal extremities. Histopathologic examination demonstrates the degeneration of the eccrine gland and neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrates.7 Lastly, necrotizing fasciitis is a life-threatening infection of the deep soft tissue and fascia, classically caused by group A Streptococcus. The infected site may have erythema, tenderness, fluctuance, necrosis, and bullae.8 Although our patient had a fever, he did not display the tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnea, and rapid deterioration that is common in necrotizing fasciitis.

Sweet syndrome may present with various morphologies within the same patient. Painful, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, nodules, bullae, and ulcers may be seen. A workup for an underlying malignancy may be warranted based on clinical presentation. Most patients have a rapid and dramatic response to systemic corticosteroids.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/J .JAAD.2017.11.064

- Pulido-Pérez A, Bergon-Sendin M, Sacks CA. Images in clinical medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;16:382. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1911025

- Marzano AV, Hilbrands L, Le ST, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:414. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00414

- Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:299-306. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0076-6

- Hee Cho-Vega J, Jeffrey Medeiros L, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142. doi:10.1309/WYAC YWF6NGM3WBRT

- Bachmeyer C, Aractingi S. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:319-330. doi:10.1016/S0738-081X(99)00123-6

- Shimizu T, Tokuda Y. Necrotizing fasciitis. Intern Med. 2010; 49:1051-1057. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2964

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/J .JAAD.2017.11.064

- Pulido-Pérez A, Bergon-Sendin M, Sacks CA. Images in clinical medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;16:382. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1911025

- Marzano AV, Hilbrands L, Le ST, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:414. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00414

- Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:299-306. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0076-6

- Hee Cho-Vega J, Jeffrey Medeiros L, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142. doi:10.1309/WYAC YWF6NGM3WBRT

- Bachmeyer C, Aractingi S. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:319-330. doi:10.1016/S0738-081X(99)00123-6

- Shimizu T, Tokuda Y. Necrotizing fasciitis. Intern Med. 2010; 49:1051-1057. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2964

A 64-year-old man with long-standing myelofibrosis presented with neutropenic fevers as well as progressive painful lesions of 3 days’ duration on the legs. A bone marrow biopsy during this hospitalization demonstrated a recent progression of the patient’s myelofibrosis to acute myeloid leukemia. Physical examination revealed round to oval, violaceous, targetoid plaques. Within a week, new erythematous and nodular lesions appeared on the right arm and left vermilion border. The lesions on the legs enlarged, formed bullae, and ulcerated.

Fungated Eroded Plaque on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

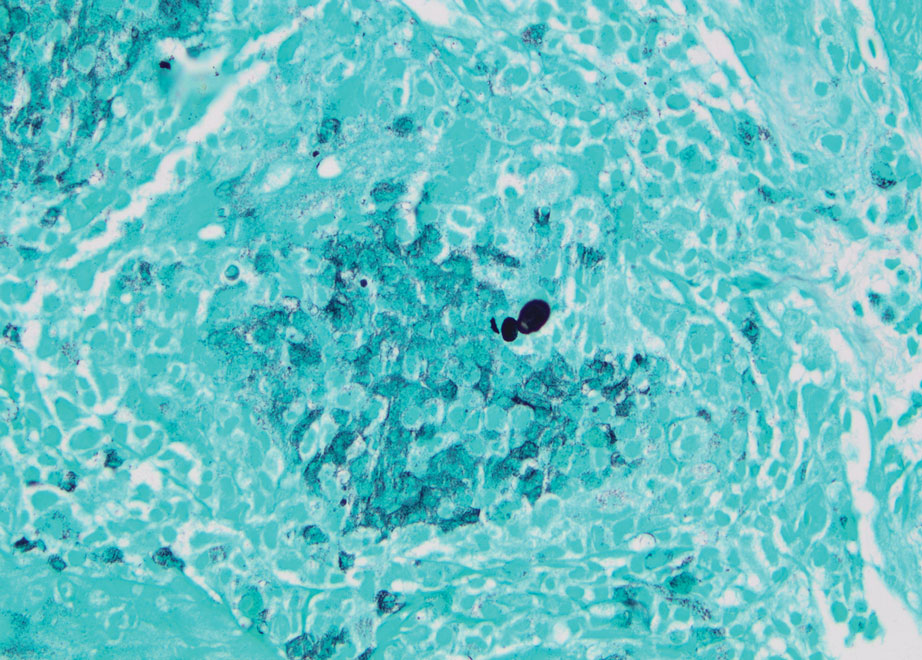

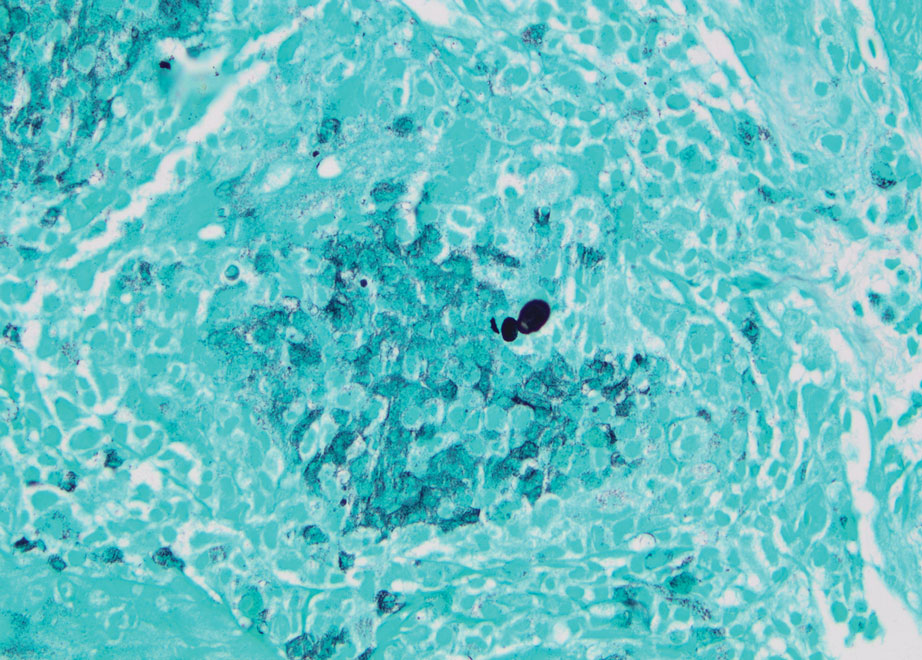

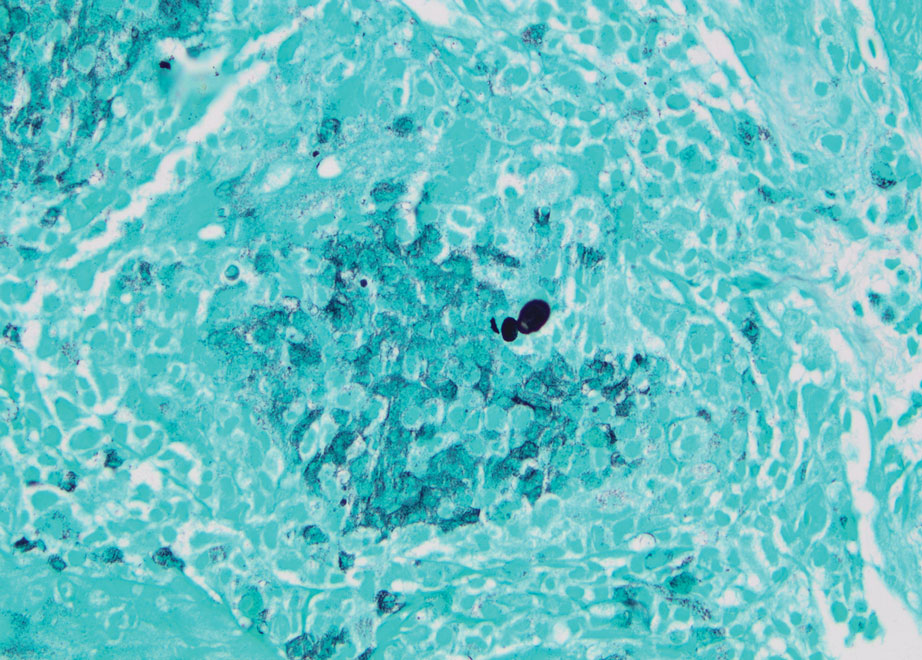

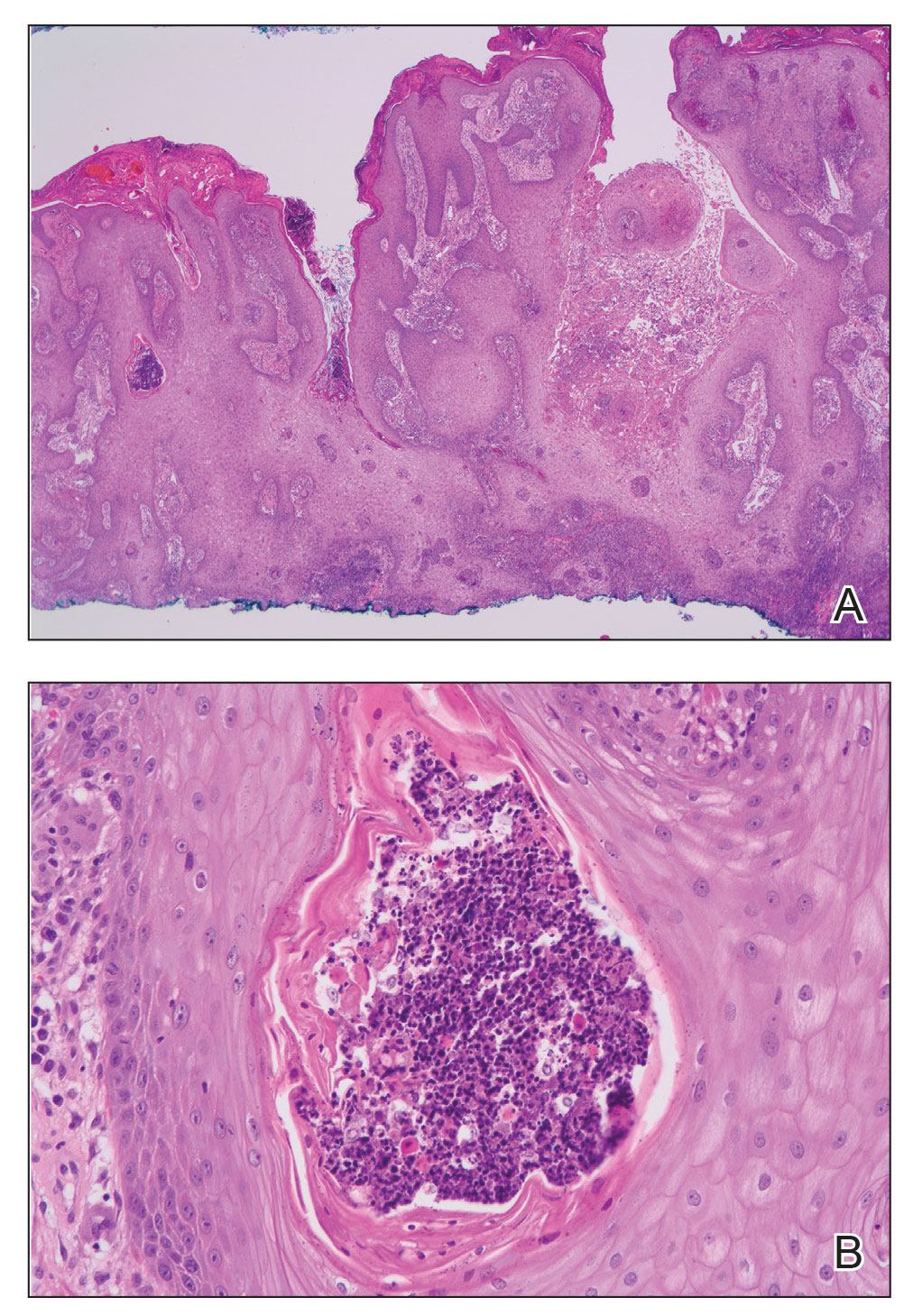

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

A 39-year-old man from Ohio presented with a tender, 10×6-cm, fungated, eroded plaque on the right medial upper arm that developed over the last 4 years. He initially noticed a firm lump under the right arm 4 years prior that was diagnosed as possible cellulitis at an outside clinic and treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The lesion then began to erode and became a chronic nonhealing wound. Approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation, the patient recalled unloading a truckload of soil around the same time the wound began to enlarge in diameter and depth. He denied any prior or current respiratory or systemic symptoms including fevers, chills, or weight loss.