User login

Violaceous Nodules on the Leg in a Patient with HIV

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

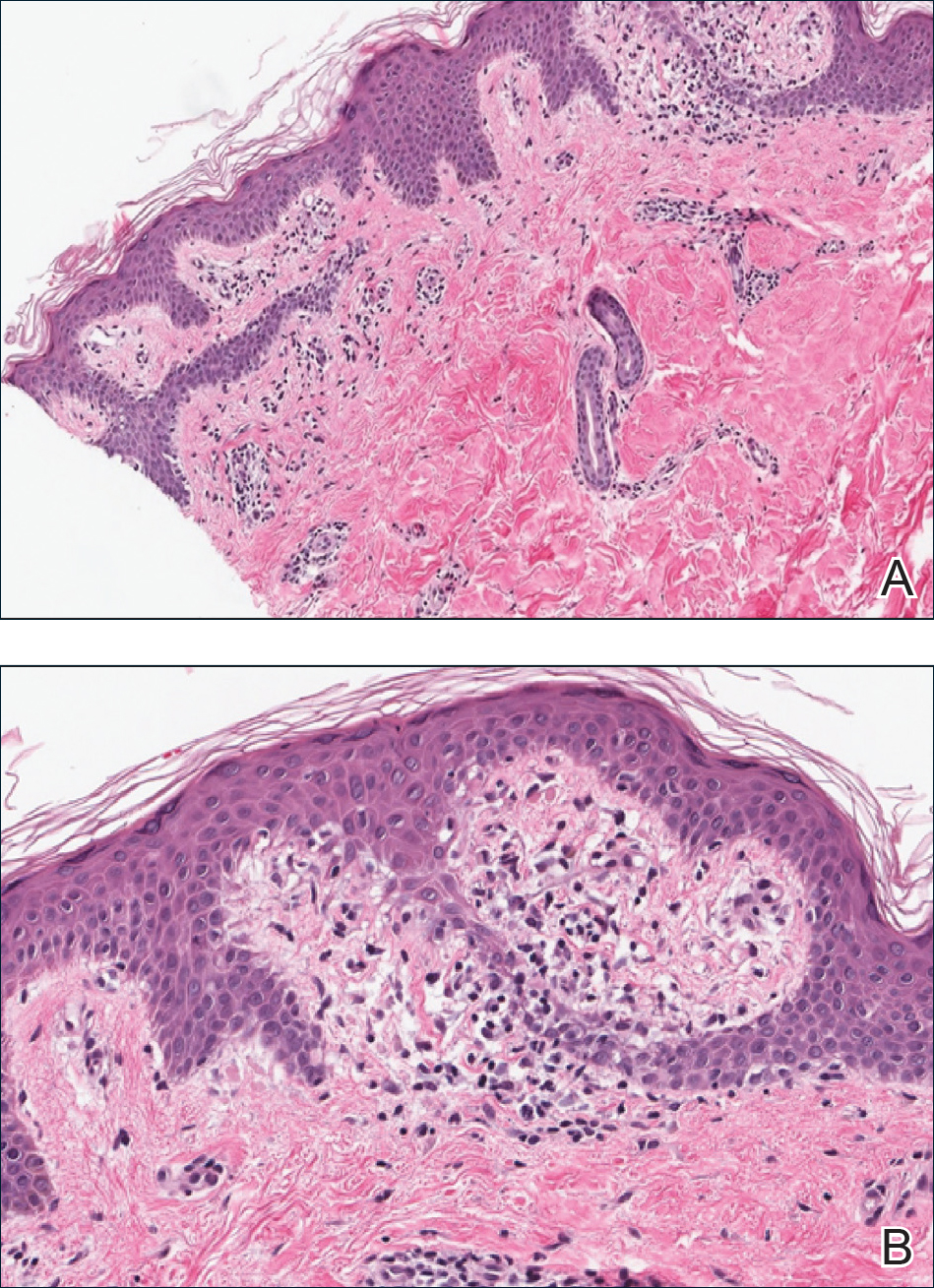

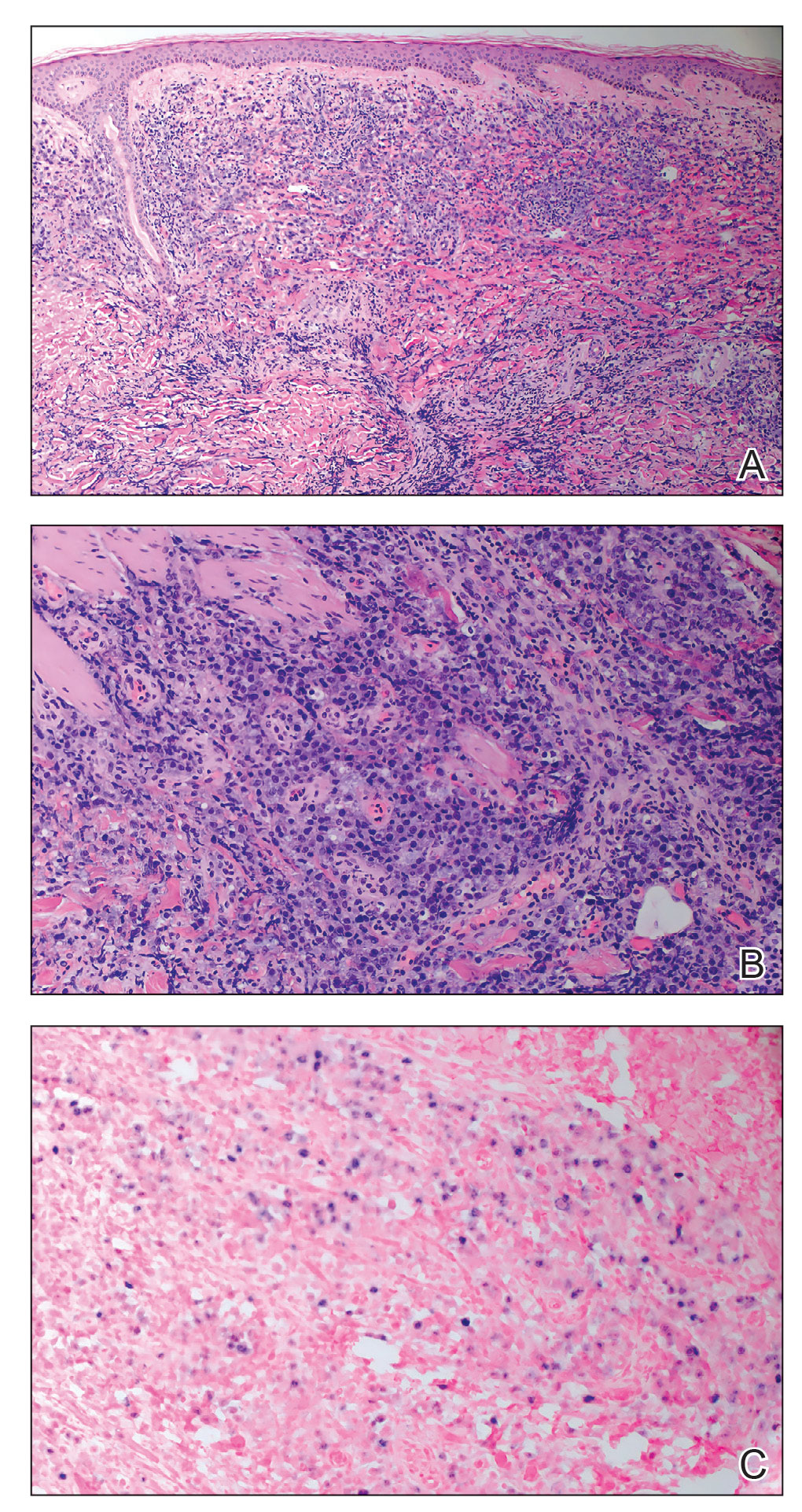

A punch biopsy of one of the leg nodules with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed sheets of medium to large cells with plasmacytic differentiation (Figure, A and B). Immunohistochemistry showed CD79, epithelial membrane antigen, multiple myeloma 1, and CD138 positivity, as well as CD-19 negativity and positive staining on Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in situ hybridization (Figure, C). Ki-67 stained greater than 90% of the neoplastic cells. Neoplastic cells were found to be λ restricted on κ and λ immunohistochemistry. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), CD3, and CD20 stains were negative. Subsequent fluorescent in situ hybridization was positive for MYC/immunoglobulin heavy chain (MYC/IGH) rearrangement t(8;14), confirming a diagnosis of plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL).

A bone marrow biopsy revealed normocellular bone marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis and no morphologic, immunophenotypic, or fluorescent in situ hybridization evidence of plasmablastic lymphoma or other pathology in the bone marrow. Our patient was started on hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin hydrochloride, dexamethasone) chemotherapy and was doing well with plans for a fourth course of chemotherapy. There is no standardized treatment course for cutaneous PBL, though excision with adjunctive chemotherapy treatment commonly has been reported in the literature.1

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare and aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with EBV infection that compromises approximately 2% to 3% of all HIV-related lymphomas.1,2 It frequently is associated with immunosuppression in patients with HIV or in transplant recipients on immunosuppression; however, it has been reported in immunocompetent individuals such as elderly patients.2 Plasmablastic lymphoma most commonly presents on the buccal mucosa but also can affect the gastrointestinal tract and occasionally has cutaneous manifestations.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations of PBL range from erythematous infiltrated plaques to ulcerated nodules presenting in an array of colors from flesh colored to violaceous.2 Primary cutaneous lesions can be seen on the legs, as in our patient.

Histopathologic examination reveals sheets of plasmablasts or large cells with eccentric nuclei and abundant basophilic cytoplasm.1 Plasmablastic lymphoma frequently is positive for mature B-cell markers such as CD38, CD138, multiple myeloma 1, and B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein 1.2,3 Uncommonly, PBL expresses paired box protein Pax-5 and CD20 markers.3 Although pathogenesis is poorly understood, it has been speculated that EBV infection is a common pathogenic factor. Epstein-Barr virus positivity has been noted in 60% of cases.2

Plasmablastic lymphoma and other malignant plasma cell processes such as plasmablastic myeloma (PBM) are morphologically similar. Proliferation of plasmablasts with rare plasmacytic cells is common in PBL, while plasmacytic cells are predominant in PBM. MYC rearrangement/ immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement t(8;14) was used to differentiate PBL from PBM in our patient; however, more cases of PBM with MYC/IGH rearrangement t(8;14) have been reported, making it an unreliable differentiating factor.4 A detailed clinical, pathologic, and genetic survey remains necessary for confirmatory diagnosis of PBL. Compared to other malignant plasma cell processes, PBL more commonly is seen in immunocompromised patients or those with HIV, such as our patient. Additionally, EBV testing is more likely to be positive in patients with PBL, further supporting this diagnosis in our patient.4

Presentations of bacillary angiomatosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and cutaneous lymphoma may be clinically similar; therefore, careful immunohistopathologic differentiation is necessary. Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative disorder that develops from HHV-8 infection and commonly is associated with HIV. It presents as painless vascular lesions in a range of colors with typical progression from patch to plaque to nodules, frequently on the lower extremities. Histologically, admixtures of bland spindle cells, slitlike small vessel proliferation, and lymphocytic infiltration are typical. Neoplastic vessels lack basement membrane zones, resulting in microhemorrhages and hemosiderin deposition. Neoplastic vessels label with CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers in addition to HHV-8 antibodies, which is highly specific for Kaposi sarcoma and differentiates it from PBL.5

Bacillary angiomatosis is an infectious neovascular proliferation characterized by papular lesions that may resemble the lesions of PBL. Mixed cell infiltration in inflammatory cells with clumping of granular material is characteristic. Under Warthin-Starry staining, the granular material is abundant in gram-negative rods representing Bartonella species, which is the implicated infectious agent in bacillary angiomatosis.

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is the most common CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder and also may present with exophytic nodules. The etiology of LyP remains unknown, but it is suspected that overexpression of CD30 plays a role. Lymphomatoid papulosis presents as red-violaceous papules and nodules in various stages of healing. Although variable histology among types of LyP exists, CD30+ T-cell lymphocytes remain the hallmark of LyP. Type A LyP, which accounts for 80% of LyP cases, reveals CD4+ and CD30+ cells scattered among neutrophils, eosinophils, and small lymphocytes.5 Lymphomatoid papulosis typically is self-healing, recurrent, and carries an excellent prognosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma remains a rare and aggressive type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that can have primary cutaneous manifestations. It is prudent to consider PBL in the differential diagnosis of nodular lower extremity lesions, especially in immunosuppressed patients.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Marques SA, Abbade LP, Guiotoku MM, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma revealing clinically unsuspected HIV infection. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:507-509.

- Bhatt R, Desai DS. Plasmablastic lymphoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532975/

- Morris A, Monohan G. Plasmablastic myeloma versus plasmablastic lymphoma: different yet related diseases. Hematol Transfus Int J. 2018;6:25-28. doi:10.15406/htij.2018.06.00146

- Prieto-Torres L, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Onaindia A, et al. CD30-positive primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: molecular alterations and targeted therapies. Haematologica. 2019;104:226-235.

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

A punch biopsy of one of the leg nodules with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed sheets of medium to large cells with plasmacytic differentiation (Figure, A and B). Immunohistochemistry showed CD79, epithelial membrane antigen, multiple myeloma 1, and CD138 positivity, as well as CD-19 negativity and positive staining on Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in situ hybridization (Figure, C). Ki-67 stained greater than 90% of the neoplastic cells. Neoplastic cells were found to be λ restricted on κ and λ immunohistochemistry. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), CD3, and CD20 stains were negative. Subsequent fluorescent in situ hybridization was positive for MYC/immunoglobulin heavy chain (MYC/IGH) rearrangement t(8;14), confirming a diagnosis of plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL).

A bone marrow biopsy revealed normocellular bone marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis and no morphologic, immunophenotypic, or fluorescent in situ hybridization evidence of plasmablastic lymphoma or other pathology in the bone marrow. Our patient was started on hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin hydrochloride, dexamethasone) chemotherapy and was doing well with plans for a fourth course of chemotherapy. There is no standardized treatment course for cutaneous PBL, though excision with adjunctive chemotherapy treatment commonly has been reported in the literature.1

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare and aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with EBV infection that compromises approximately 2% to 3% of all HIV-related lymphomas.1,2 It frequently is associated with immunosuppression in patients with HIV or in transplant recipients on immunosuppression; however, it has been reported in immunocompetent individuals such as elderly patients.2 Plasmablastic lymphoma most commonly presents on the buccal mucosa but also can affect the gastrointestinal tract and occasionally has cutaneous manifestations.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations of PBL range from erythematous infiltrated plaques to ulcerated nodules presenting in an array of colors from flesh colored to violaceous.2 Primary cutaneous lesions can be seen on the legs, as in our patient.

Histopathologic examination reveals sheets of plasmablasts or large cells with eccentric nuclei and abundant basophilic cytoplasm.1 Plasmablastic lymphoma frequently is positive for mature B-cell markers such as CD38, CD138, multiple myeloma 1, and B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein 1.2,3 Uncommonly, PBL expresses paired box protein Pax-5 and CD20 markers.3 Although pathogenesis is poorly understood, it has been speculated that EBV infection is a common pathogenic factor. Epstein-Barr virus positivity has been noted in 60% of cases.2

Plasmablastic lymphoma and other malignant plasma cell processes such as plasmablastic myeloma (PBM) are morphologically similar. Proliferation of plasmablasts with rare plasmacytic cells is common in PBL, while plasmacytic cells are predominant in PBM. MYC rearrangement/ immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement t(8;14) was used to differentiate PBL from PBM in our patient; however, more cases of PBM with MYC/IGH rearrangement t(8;14) have been reported, making it an unreliable differentiating factor.4 A detailed clinical, pathologic, and genetic survey remains necessary for confirmatory diagnosis of PBL. Compared to other malignant plasma cell processes, PBL more commonly is seen in immunocompromised patients or those with HIV, such as our patient. Additionally, EBV testing is more likely to be positive in patients with PBL, further supporting this diagnosis in our patient.4

Presentations of bacillary angiomatosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and cutaneous lymphoma may be clinically similar; therefore, careful immunohistopathologic differentiation is necessary. Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative disorder that develops from HHV-8 infection and commonly is associated with HIV. It presents as painless vascular lesions in a range of colors with typical progression from patch to plaque to nodules, frequently on the lower extremities. Histologically, admixtures of bland spindle cells, slitlike small vessel proliferation, and lymphocytic infiltration are typical. Neoplastic vessels lack basement membrane zones, resulting in microhemorrhages and hemosiderin deposition. Neoplastic vessels label with CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers in addition to HHV-8 antibodies, which is highly specific for Kaposi sarcoma and differentiates it from PBL.5

Bacillary angiomatosis is an infectious neovascular proliferation characterized by papular lesions that may resemble the lesions of PBL. Mixed cell infiltration in inflammatory cells with clumping of granular material is characteristic. Under Warthin-Starry staining, the granular material is abundant in gram-negative rods representing Bartonella species, which is the implicated infectious agent in bacillary angiomatosis.

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is the most common CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder and also may present with exophytic nodules. The etiology of LyP remains unknown, but it is suspected that overexpression of CD30 plays a role. Lymphomatoid papulosis presents as red-violaceous papules and nodules in various stages of healing. Although variable histology among types of LyP exists, CD30+ T-cell lymphocytes remain the hallmark of LyP. Type A LyP, which accounts for 80% of LyP cases, reveals CD4+ and CD30+ cells scattered among neutrophils, eosinophils, and small lymphocytes.5 Lymphomatoid papulosis typically is self-healing, recurrent, and carries an excellent prognosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma remains a rare and aggressive type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that can have primary cutaneous manifestations. It is prudent to consider PBL in the differential diagnosis of nodular lower extremity lesions, especially in immunosuppressed patients.

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

A punch biopsy of one of the leg nodules with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed sheets of medium to large cells with plasmacytic differentiation (Figure, A and B). Immunohistochemistry showed CD79, epithelial membrane antigen, multiple myeloma 1, and CD138 positivity, as well as CD-19 negativity and positive staining on Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in situ hybridization (Figure, C). Ki-67 stained greater than 90% of the neoplastic cells. Neoplastic cells were found to be λ restricted on κ and λ immunohistochemistry. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), CD3, and CD20 stains were negative. Subsequent fluorescent in situ hybridization was positive for MYC/immunoglobulin heavy chain (MYC/IGH) rearrangement t(8;14), confirming a diagnosis of plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL).

A bone marrow biopsy revealed normocellular bone marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis and no morphologic, immunophenotypic, or fluorescent in situ hybridization evidence of plasmablastic lymphoma or other pathology in the bone marrow. Our patient was started on hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin hydrochloride, dexamethasone) chemotherapy and was doing well with plans for a fourth course of chemotherapy. There is no standardized treatment course for cutaneous PBL, though excision with adjunctive chemotherapy treatment commonly has been reported in the literature.1

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare and aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with EBV infection that compromises approximately 2% to 3% of all HIV-related lymphomas.1,2 It frequently is associated with immunosuppression in patients with HIV or in transplant recipients on immunosuppression; however, it has been reported in immunocompetent individuals such as elderly patients.2 Plasmablastic lymphoma most commonly presents on the buccal mucosa but also can affect the gastrointestinal tract and occasionally has cutaneous manifestations.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations of PBL range from erythematous infiltrated plaques to ulcerated nodules presenting in an array of colors from flesh colored to violaceous.2 Primary cutaneous lesions can be seen on the legs, as in our patient.

Histopathologic examination reveals sheets of plasmablasts or large cells with eccentric nuclei and abundant basophilic cytoplasm.1 Plasmablastic lymphoma frequently is positive for mature B-cell markers such as CD38, CD138, multiple myeloma 1, and B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein 1.2,3 Uncommonly, PBL expresses paired box protein Pax-5 and CD20 markers.3 Although pathogenesis is poorly understood, it has been speculated that EBV infection is a common pathogenic factor. Epstein-Barr virus positivity has been noted in 60% of cases.2

Plasmablastic lymphoma and other malignant plasma cell processes such as plasmablastic myeloma (PBM) are morphologically similar. Proliferation of plasmablasts with rare plasmacytic cells is common in PBL, while plasmacytic cells are predominant in PBM. MYC rearrangement/ immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement t(8;14) was used to differentiate PBL from PBM in our patient; however, more cases of PBM with MYC/IGH rearrangement t(8;14) have been reported, making it an unreliable differentiating factor.4 A detailed clinical, pathologic, and genetic survey remains necessary for confirmatory diagnosis of PBL. Compared to other malignant plasma cell processes, PBL more commonly is seen in immunocompromised patients or those with HIV, such as our patient. Additionally, EBV testing is more likely to be positive in patients with PBL, further supporting this diagnosis in our patient.4

Presentations of bacillary angiomatosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and cutaneous lymphoma may be clinically similar; therefore, careful immunohistopathologic differentiation is necessary. Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative disorder that develops from HHV-8 infection and commonly is associated with HIV. It presents as painless vascular lesions in a range of colors with typical progression from patch to plaque to nodules, frequently on the lower extremities. Histologically, admixtures of bland spindle cells, slitlike small vessel proliferation, and lymphocytic infiltration are typical. Neoplastic vessels lack basement membrane zones, resulting in microhemorrhages and hemosiderin deposition. Neoplastic vessels label with CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers in addition to HHV-8 antibodies, which is highly specific for Kaposi sarcoma and differentiates it from PBL.5

Bacillary angiomatosis is an infectious neovascular proliferation characterized by papular lesions that may resemble the lesions of PBL. Mixed cell infiltration in inflammatory cells with clumping of granular material is characteristic. Under Warthin-Starry staining, the granular material is abundant in gram-negative rods representing Bartonella species, which is the implicated infectious agent in bacillary angiomatosis.

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is the most common CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder and also may present with exophytic nodules. The etiology of LyP remains unknown, but it is suspected that overexpression of CD30 plays a role. Lymphomatoid papulosis presents as red-violaceous papules and nodules in various stages of healing. Although variable histology among types of LyP exists, CD30+ T-cell lymphocytes remain the hallmark of LyP. Type A LyP, which accounts for 80% of LyP cases, reveals CD4+ and CD30+ cells scattered among neutrophils, eosinophils, and small lymphocytes.5 Lymphomatoid papulosis typically is self-healing, recurrent, and carries an excellent prognosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma remains a rare and aggressive type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that can have primary cutaneous manifestations. It is prudent to consider PBL in the differential diagnosis of nodular lower extremity lesions, especially in immunosuppressed patients.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Marques SA, Abbade LP, Guiotoku MM, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma revealing clinically unsuspected HIV infection. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:507-509.

- Bhatt R, Desai DS. Plasmablastic lymphoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532975/

- Morris A, Monohan G. Plasmablastic myeloma versus plasmablastic lymphoma: different yet related diseases. Hematol Transfus Int J. 2018;6:25-28. doi:10.15406/htij.2018.06.00146

- Prieto-Torres L, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Onaindia A, et al. CD30-positive primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: molecular alterations and targeted therapies. Haematologica. 2019;104:226-235.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Marques SA, Abbade LP, Guiotoku MM, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma revealing clinically unsuspected HIV infection. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:507-509.

- Bhatt R, Desai DS. Plasmablastic lymphoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532975/

- Morris A, Monohan G. Plasmablastic myeloma versus plasmablastic lymphoma: different yet related diseases. Hematol Transfus Int J. 2018;6:25-28. doi:10.15406/htij.2018.06.00146

- Prieto-Torres L, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Onaindia A, et al. CD30-positive primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: molecular alterations and targeted therapies. Haematologica. 2019;104:226-235.

A 67-year-old man with long-standing hepatitis B virus and HIV managed with chronic antiretroviral therapy presented to an urgent care facility with worsening erythema and edema of the legs of 2 weeks’ duration. He was prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin for presumed cellulitis. Two months later, he developed nodules on the lower extremities. He was seen by podiatry and prescribed a course of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid for presumed infection. Despite 2 courses of antibiotics, his symptoms progressed. The nodules expanded in number and some developed ulceration. Three months into his clinical course, he presented to our dermatology clinic. Physical examination revealed two 2- to 3-cm, violaceous, exophytic, tender nodules. He reported tactile allodynia of the lower extremities and denied fever, chills, night sweats, or weight loss. He also denied exposure to infectious or chemical agents and reported no recent travel. The patient was chronically taking lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide, escitalopram, elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, bupropion, and aspirin with no recent changes. A complete hematologic and biochemical survey largely was unremarkable. His HIV viral load was undetectable with a CD4 count greater than 400/mm3 (reference range, 490–1436/mm3). Lactate dehydrogenase was elevated at 568 IU/L (reference range, 135–225 IU/L). The lower leg lesions were biopsied for confirmatory diagnosis.

Paraneoplastic Signs in Bladder Transitional Cell Carcinoma: An Unusual Presentation

To the Editor:

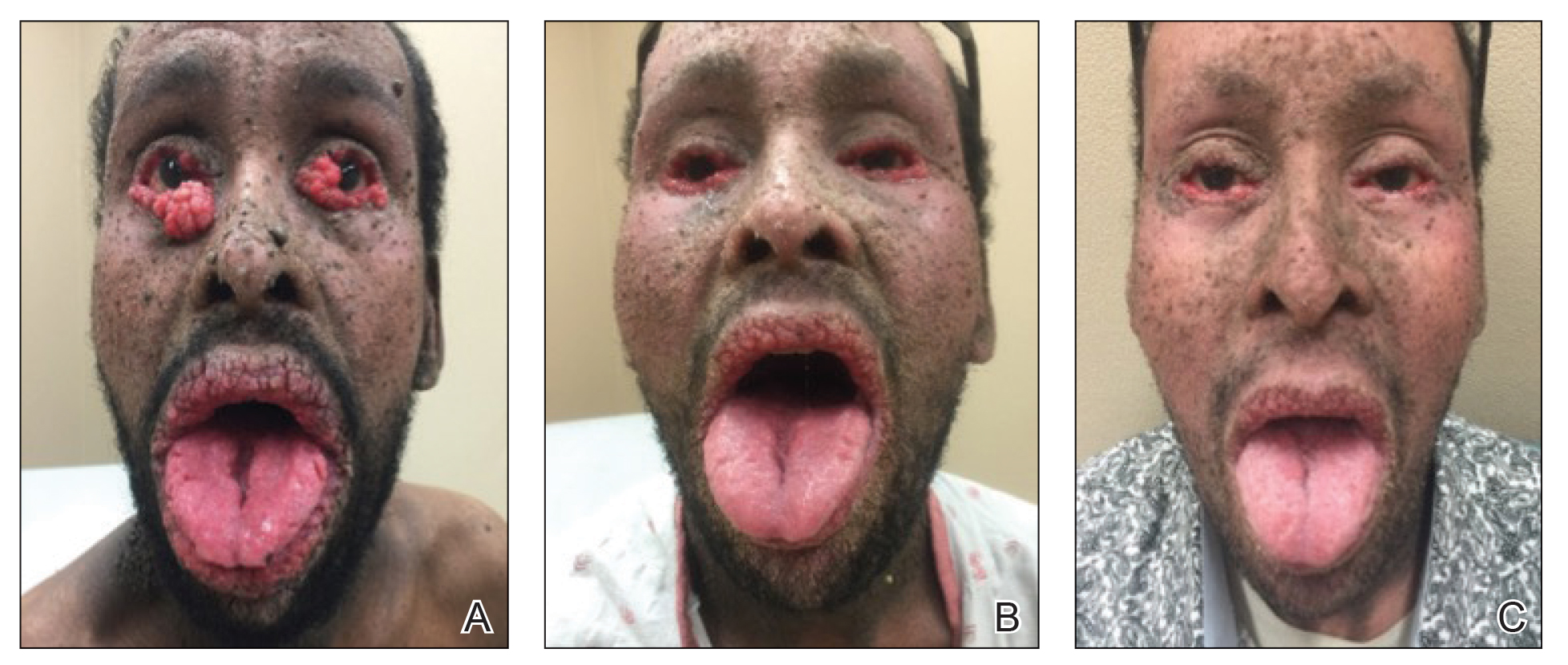

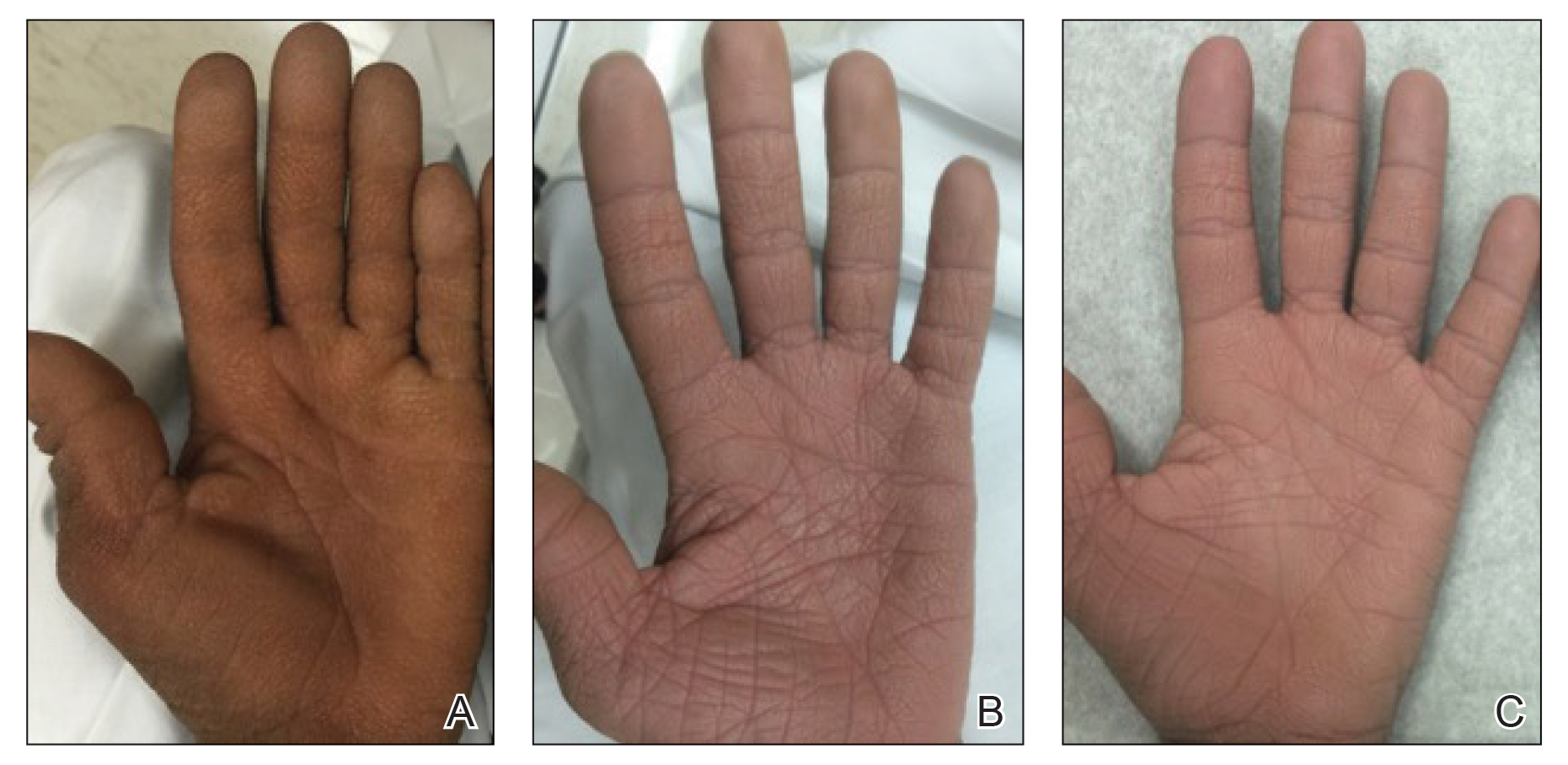

A 40-year-old Somalian man presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the eyelids, tongue, lips, and hands of 8 years’ duration. He was a former refugee who had faced considerable stigma from his community due to his appearance. A review of systems was remarkable for decreased appetite but no weight loss. He reported no abdominal distention, early satiety, or urinary symptoms, and he had no personal history of diabetes mellitus or obesity. Physical examination demonstrated hyperpigmented velvety plaques in all skin folds and on the genitalia. Massive papillomatosis of the eyelid margins, tongue, and lips also was noted (Figure 1A). Flesh-colored papules also were scattered across the face. Punctate, flesh-colored papules were present on the volar and palmar hands (Figure 2A). Histopathology demonstrated pronounced papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with negative human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 and HPV-18 DNA studies. Given the appearance of malignant acanthosis nigricans with oral and conjunctival features, cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms, concern for underlying malignancy was high. Malignancy workup, including upper and lower endoscopy as well as serial computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, was unrevealing.

Laboratory investigation revealed a positive Schistosoma IgG antibody (0.38 geometric mean egg count) and peripheral eosinophilia (1.09 ×103/μL), which normalized after praziquantel therapy. With no malignancy identified over the preceding 6-month period, treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily was initiated based on limited literature support.1-3 Treatment led to reduction in the size and number of papillomas (Figure 1B) and tripe palms (Figure 2B) with increased mobility of hands, lips, and tongue. The patient underwent oculoplastic surgery to reduce the papilloma burden along the eyelid margins. Subsequent cystoscopy 9 months after the initial presentation revealed low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Intraoperative mitomycin C led to tumor shrinkage and, with continued treatment with daily acitretin, dramatic improvement of all cutaneous and mucosal symptoms (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). To date, his cutaneous symptoms have resolved.

This case demonstrated a unique presentation of multiple paraneoplastic signs in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. The presence of malignant acanthosis nigricans (including oral and conjunctival involvement), cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms have been individually documented in various types of gastric malignancies.4 Acanthosis nigricans often is secondary to diabetes and obesity, presenting with diffuse, thickened, velvety plaques in the flexural areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans is a rare, rapidly progressive condition that often presents over a period of weeks to months; it almost always is associated with internal malignancies. It often has more extensive involvement, extending beyond the flexural areas, than typical acanthosis nigricans.4 Oral involvement can be either hypertrophic or papillomatous; papillomatosis of the oral mucosa was reported in over 40% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases (N=200).5 Cases with conjunctival involvement are less common.6 Although malignant acanthosis nigricans often is codiagnosed with a malignancy, it can precede the cancer diagnosis in some cases.7,8 A majority of cases are associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.4 Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis also is a rare paraneoplastic condition that most commonly is associated with gastric adenocarcinomas. Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis often presents rapidly as verrucous growths on cutaneous surfaces (including the hands and face) but also can affect mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and conjunctiva.9-11 Tripe palms are characterized by exaggerated dermatoglyphics with diffuse palmar ridging and hyperkeratosis. Tripe palms most often are associated with pulmonary malignancies. When tripe palms are present with malignant acanthosis nigricans, they reflect up to a one-third incidence of gastrointestinal malignancy.12,13

Despite the individual presentation of these paraneoplastic signs in a variety of malignancies, synchronous presentation is rare. A brief literature review only identified 6 cases of concurrent acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis with an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.1,11,14-17 Two additional reports described tripe palms with oral acanthosis nigricans and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis in metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma and renal urothelial carcinoma.2,18 An additional case of all 3 paraneoplastic conditions was reported in the setting of metastatic cervical cancer (HPV positive).19 Per a recent case report and literature review,20 there have only been 8 cases of acanthosis nigricans reported in bladder transitional cell carcinoma,20-27 half of which have included oral malignant acanthosis nigricans.20-23 Only one report of concurrent cutaneous and oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and triple palms in the setting of bladder cancer has been reported.20 Given the extensive conjunctival involvement and cutaneous papillomatosis in our patient, ours is a rarely reported case of concurrent malignant mucocutaneous acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive papillomatosis in transitional cell bladder carcinoma. We believe it is imperative to consider the role of this malignancy as a cause of these paraneoplastic conditions.

Although these paraneoplastic conditions rarely co-occur, our case further offers a common molecular pathway for these conditions.28 In these paraneoplastic conditions, the stimulating factor is thought to be tumor growth factor α, which is structurally related to epidermal growth factor (EGF). Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where activation stimulates keratinocyte growth and leads to the cutaneous manifestation of symptoms.28 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations are found in most noninvasive transitional cell tumors of the bladder.29 The fibroblast growth factor pathway is distinctly different from the tumor growth factor α and EGF pathways.30 However, this association with transitional cell carcinoma suggests that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 also may be implicated in these paraneoplastic conditions.

Our patient responded well to treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily. The mechanism of action of retinoids involves inducing mitotic activity and desmosomal shedding.31 Retinoids downregulate EGFR expression and activation in EGF-stimulated cells.32 We hypothesize that these oral retinoids decreased the growth stimulus and thereby improved cutaneous signs in the setting of our patient’s transitional cell cancer. Although definitive therapy is malignancy management, our case highlights the utility of adjunctive measures such as oral retinoids and surgical debulking. While previous cases have reported use of retinoids at a lower dosage than used in this case, oral lesions often have only been mildly improved with little impact on other cutaneous symptoms.1,2 In one case of malignant acanthosis nigricans and oral papillomatosis, isotretinoin 25 mg once every 2 to 3 days led to a moderate decrease in hyperkeratosis and papillomas, but the patient was lost to follow-up.3 Our case highlights the use of higher daily doses of oral retinoids for over 9 months, resulting in marked improvement in both the mucosal and cutaneous symptoms of acanthosis nigricans, progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms. Therefore, oral acitretin should be considered as adjuvant therapy for these paraneoplastic conditions.

By reporting this case, we hope to demonstrate the importance of considering other forms of malignancies in the presence of paraneoplastic conditions. Although gastric malignancies more commonly are associated with these conditions, bladder carcinomas also can present with cutaneous manifestations. The presence of these paraneoplastic conditions alone or together rarely is reported in urologic cancers and generally is considered to be an indicator of poor prognosis. Paraneoplastic conditions often develop rapidly and occur in very advanced malignancies.4 The disfiguring presentation in our case also had unusual diagnostic challenges. The presence of these conditions for 8 years and nonmetastatic advanced malignancy suggest a more indolent process and that these signs are not always an indicator of poor prognosis. Future patients with these paraneoplastic conditions may benefit from both a thorough malignancy screen, including cystoscopy, and high daily doses of oral retinoids.

- Stawczyk-Macieja M, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:56-58.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong W-S. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1151-1153.

- Wick MR, Patterson JW. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes [published online January 31, 2019]. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36:211-228.

- Tyler MT, Ficarra G, Silverman S, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with florid papillary oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:445-449.

- Zhang X, Liu R, Liu Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology. 2020;20:1-4.

- Curth HO. Dermatoses and malignant internal tumours. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1955;71:95-107.

- Krawczyk M, Mykala-Cies´la J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

- Singhi MK, Gupta LK, Bansal M, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 year old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:195-196.

- Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E218-E219.

- Yang YH, Zhang RZ, Kang DH, et al. Three paraneoplastic signs in the same patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18966.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Buranathawornsom A, Sirinawasatien A. Diffuse esophageal squamous papillomatosis: a rare disease associated with acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:702-706.

- Muhammad R, Iftikhar N, Sarfraz T, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an indicator of internal malignancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:888-890.

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:573-577.

- Vilas-Sueiro A, Suárez-Amor O, Monteagudo B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis, and tripe palms in a man with gastric adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:438-439.

- Paravina M, Ljubisavljevic´ D. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma—a case report. Serbian J Dermatology Venereol. 2015;7:5-14.

- Kleikamp S, Böhm M, Frosch P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans, papillomatosis mucosae and “tripe” palms in a patient with metastasized gastric carcinoma [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1209-1213.

- Mikhail GR, Fachnie DM, Drukker BH, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:201-202.

- Zhang R, Jiang M, Lei W, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with recurrent bladder cancer: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:951.

- Olek-Hrab K, Silny W, Zaba R, et al. Co-occurrence of acanthosis nigricans and bladder adenocarcinoma-case report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:327-330.

- Canjuga I, Mravak-Stipetic´ M, Kopic´V, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans: case report and comparison with literature reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:91-95.

- Cairo F, Rubino I, Rotundo R, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans as a marker of internal malignancy. a case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1271-1275.

- Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Singh GK, Sen D, Mulajker DS, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:722-725.

- Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433-435.

- Pinto WBVR, Badia BML, Souza PVS, et al. Paraneoplastic motor neuronopathy and malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77:527.

- Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factor–alpha (TGF-alpha)-producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:71-77.

- Billerey C, Chopin D, Aubriot-Lorton MH, et al. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in papillary non-invasive bladder (pTa) tumors. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1955-1959.

- Lee C-J, Lee M-H, Cho Y-Y. Fibroblast and epidermal growth factors utilize different signaling pathways to induce anchorage-independent cell transformation in JB6 Cl41 mouse skin epidermal cells. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:199-208.

- Darmstadt GL, Yokel BK, Horn TD. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1139-1140.

- Sah JF, Eckert RL, Chandraratna RA, et al. Retinoids suppress epidermal growth factor–associated cell proliferation by inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor–dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9728-9735.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old Somalian man presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the eyelids, tongue, lips, and hands of 8 years’ duration. He was a former refugee who had faced considerable stigma from his community due to his appearance. A review of systems was remarkable for decreased appetite but no weight loss. He reported no abdominal distention, early satiety, or urinary symptoms, and he had no personal history of diabetes mellitus or obesity. Physical examination demonstrated hyperpigmented velvety plaques in all skin folds and on the genitalia. Massive papillomatosis of the eyelid margins, tongue, and lips also was noted (Figure 1A). Flesh-colored papules also were scattered across the face. Punctate, flesh-colored papules were present on the volar and palmar hands (Figure 2A). Histopathology demonstrated pronounced papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with negative human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 and HPV-18 DNA studies. Given the appearance of malignant acanthosis nigricans with oral and conjunctival features, cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms, concern for underlying malignancy was high. Malignancy workup, including upper and lower endoscopy as well as serial computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, was unrevealing.

Laboratory investigation revealed a positive Schistosoma IgG antibody (0.38 geometric mean egg count) and peripheral eosinophilia (1.09 ×103/μL), which normalized after praziquantel therapy. With no malignancy identified over the preceding 6-month period, treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily was initiated based on limited literature support.1-3 Treatment led to reduction in the size and number of papillomas (Figure 1B) and tripe palms (Figure 2B) with increased mobility of hands, lips, and tongue. The patient underwent oculoplastic surgery to reduce the papilloma burden along the eyelid margins. Subsequent cystoscopy 9 months after the initial presentation revealed low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Intraoperative mitomycin C led to tumor shrinkage and, with continued treatment with daily acitretin, dramatic improvement of all cutaneous and mucosal symptoms (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). To date, his cutaneous symptoms have resolved.

This case demonstrated a unique presentation of multiple paraneoplastic signs in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. The presence of malignant acanthosis nigricans (including oral and conjunctival involvement), cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms have been individually documented in various types of gastric malignancies.4 Acanthosis nigricans often is secondary to diabetes and obesity, presenting with diffuse, thickened, velvety plaques in the flexural areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans is a rare, rapidly progressive condition that often presents over a period of weeks to months; it almost always is associated with internal malignancies. It often has more extensive involvement, extending beyond the flexural areas, than typical acanthosis nigricans.4 Oral involvement can be either hypertrophic or papillomatous; papillomatosis of the oral mucosa was reported in over 40% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases (N=200).5 Cases with conjunctival involvement are less common.6 Although malignant acanthosis nigricans often is codiagnosed with a malignancy, it can precede the cancer diagnosis in some cases.7,8 A majority of cases are associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.4 Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis also is a rare paraneoplastic condition that most commonly is associated with gastric adenocarcinomas. Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis often presents rapidly as verrucous growths on cutaneous surfaces (including the hands and face) but also can affect mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and conjunctiva.9-11 Tripe palms are characterized by exaggerated dermatoglyphics with diffuse palmar ridging and hyperkeratosis. Tripe palms most often are associated with pulmonary malignancies. When tripe palms are present with malignant acanthosis nigricans, they reflect up to a one-third incidence of gastrointestinal malignancy.12,13

Despite the individual presentation of these paraneoplastic signs in a variety of malignancies, synchronous presentation is rare. A brief literature review only identified 6 cases of concurrent acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis with an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.1,11,14-17 Two additional reports described tripe palms with oral acanthosis nigricans and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis in metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma and renal urothelial carcinoma.2,18 An additional case of all 3 paraneoplastic conditions was reported in the setting of metastatic cervical cancer (HPV positive).19 Per a recent case report and literature review,20 there have only been 8 cases of acanthosis nigricans reported in bladder transitional cell carcinoma,20-27 half of which have included oral malignant acanthosis nigricans.20-23 Only one report of concurrent cutaneous and oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and triple palms in the setting of bladder cancer has been reported.20 Given the extensive conjunctival involvement and cutaneous papillomatosis in our patient, ours is a rarely reported case of concurrent malignant mucocutaneous acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive papillomatosis in transitional cell bladder carcinoma. We believe it is imperative to consider the role of this malignancy as a cause of these paraneoplastic conditions.

Although these paraneoplastic conditions rarely co-occur, our case further offers a common molecular pathway for these conditions.28 In these paraneoplastic conditions, the stimulating factor is thought to be tumor growth factor α, which is structurally related to epidermal growth factor (EGF). Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where activation stimulates keratinocyte growth and leads to the cutaneous manifestation of symptoms.28 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations are found in most noninvasive transitional cell tumors of the bladder.29 The fibroblast growth factor pathway is distinctly different from the tumor growth factor α and EGF pathways.30 However, this association with transitional cell carcinoma suggests that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 also may be implicated in these paraneoplastic conditions.

Our patient responded well to treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily. The mechanism of action of retinoids involves inducing mitotic activity and desmosomal shedding.31 Retinoids downregulate EGFR expression and activation in EGF-stimulated cells.32 We hypothesize that these oral retinoids decreased the growth stimulus and thereby improved cutaneous signs in the setting of our patient’s transitional cell cancer. Although definitive therapy is malignancy management, our case highlights the utility of adjunctive measures such as oral retinoids and surgical debulking. While previous cases have reported use of retinoids at a lower dosage than used in this case, oral lesions often have only been mildly improved with little impact on other cutaneous symptoms.1,2 In one case of malignant acanthosis nigricans and oral papillomatosis, isotretinoin 25 mg once every 2 to 3 days led to a moderate decrease in hyperkeratosis and papillomas, but the patient was lost to follow-up.3 Our case highlights the use of higher daily doses of oral retinoids for over 9 months, resulting in marked improvement in both the mucosal and cutaneous symptoms of acanthosis nigricans, progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms. Therefore, oral acitretin should be considered as adjuvant therapy for these paraneoplastic conditions.

By reporting this case, we hope to demonstrate the importance of considering other forms of malignancies in the presence of paraneoplastic conditions. Although gastric malignancies more commonly are associated with these conditions, bladder carcinomas also can present with cutaneous manifestations. The presence of these paraneoplastic conditions alone or together rarely is reported in urologic cancers and generally is considered to be an indicator of poor prognosis. Paraneoplastic conditions often develop rapidly and occur in very advanced malignancies.4 The disfiguring presentation in our case also had unusual diagnostic challenges. The presence of these conditions for 8 years and nonmetastatic advanced malignancy suggest a more indolent process and that these signs are not always an indicator of poor prognosis. Future patients with these paraneoplastic conditions may benefit from both a thorough malignancy screen, including cystoscopy, and high daily doses of oral retinoids.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old Somalian man presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the eyelids, tongue, lips, and hands of 8 years’ duration. He was a former refugee who had faced considerable stigma from his community due to his appearance. A review of systems was remarkable for decreased appetite but no weight loss. He reported no abdominal distention, early satiety, or urinary symptoms, and he had no personal history of diabetes mellitus or obesity. Physical examination demonstrated hyperpigmented velvety plaques in all skin folds and on the genitalia. Massive papillomatosis of the eyelid margins, tongue, and lips also was noted (Figure 1A). Flesh-colored papules also were scattered across the face. Punctate, flesh-colored papules were present on the volar and palmar hands (Figure 2A). Histopathology demonstrated pronounced papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with negative human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 and HPV-18 DNA studies. Given the appearance of malignant acanthosis nigricans with oral and conjunctival features, cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms, concern for underlying malignancy was high. Malignancy workup, including upper and lower endoscopy as well as serial computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, was unrevealing.

Laboratory investigation revealed a positive Schistosoma IgG antibody (0.38 geometric mean egg count) and peripheral eosinophilia (1.09 ×103/μL), which normalized after praziquantel therapy. With no malignancy identified over the preceding 6-month period, treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily was initiated based on limited literature support.1-3 Treatment led to reduction in the size and number of papillomas (Figure 1B) and tripe palms (Figure 2B) with increased mobility of hands, lips, and tongue. The patient underwent oculoplastic surgery to reduce the papilloma burden along the eyelid margins. Subsequent cystoscopy 9 months after the initial presentation revealed low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Intraoperative mitomycin C led to tumor shrinkage and, with continued treatment with daily acitretin, dramatic improvement of all cutaneous and mucosal symptoms (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). To date, his cutaneous symptoms have resolved.

This case demonstrated a unique presentation of multiple paraneoplastic signs in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. The presence of malignant acanthosis nigricans (including oral and conjunctival involvement), cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms have been individually documented in various types of gastric malignancies.4 Acanthosis nigricans often is secondary to diabetes and obesity, presenting with diffuse, thickened, velvety plaques in the flexural areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans is a rare, rapidly progressive condition that often presents over a period of weeks to months; it almost always is associated with internal malignancies. It often has more extensive involvement, extending beyond the flexural areas, than typical acanthosis nigricans.4 Oral involvement can be either hypertrophic or papillomatous; papillomatosis of the oral mucosa was reported in over 40% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases (N=200).5 Cases with conjunctival involvement are less common.6 Although malignant acanthosis nigricans often is codiagnosed with a malignancy, it can precede the cancer diagnosis in some cases.7,8 A majority of cases are associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.4 Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis also is a rare paraneoplastic condition that most commonly is associated with gastric adenocarcinomas. Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis often presents rapidly as verrucous growths on cutaneous surfaces (including the hands and face) but also can affect mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and conjunctiva.9-11 Tripe palms are characterized by exaggerated dermatoglyphics with diffuse palmar ridging and hyperkeratosis. Tripe palms most often are associated with pulmonary malignancies. When tripe palms are present with malignant acanthosis nigricans, they reflect up to a one-third incidence of gastrointestinal malignancy.12,13

Despite the individual presentation of these paraneoplastic signs in a variety of malignancies, synchronous presentation is rare. A brief literature review only identified 6 cases of concurrent acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis with an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.1,11,14-17 Two additional reports described tripe palms with oral acanthosis nigricans and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis in metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma and renal urothelial carcinoma.2,18 An additional case of all 3 paraneoplastic conditions was reported in the setting of metastatic cervical cancer (HPV positive).19 Per a recent case report and literature review,20 there have only been 8 cases of acanthosis nigricans reported in bladder transitional cell carcinoma,20-27 half of which have included oral malignant acanthosis nigricans.20-23 Only one report of concurrent cutaneous and oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and triple palms in the setting of bladder cancer has been reported.20 Given the extensive conjunctival involvement and cutaneous papillomatosis in our patient, ours is a rarely reported case of concurrent malignant mucocutaneous acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive papillomatosis in transitional cell bladder carcinoma. We believe it is imperative to consider the role of this malignancy as a cause of these paraneoplastic conditions.

Although these paraneoplastic conditions rarely co-occur, our case further offers a common molecular pathway for these conditions.28 In these paraneoplastic conditions, the stimulating factor is thought to be tumor growth factor α, which is structurally related to epidermal growth factor (EGF). Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where activation stimulates keratinocyte growth and leads to the cutaneous manifestation of symptoms.28 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations are found in most noninvasive transitional cell tumors of the bladder.29 The fibroblast growth factor pathway is distinctly different from the tumor growth factor α and EGF pathways.30 However, this association with transitional cell carcinoma suggests that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 also may be implicated in these paraneoplastic conditions.

Our patient responded well to treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily. The mechanism of action of retinoids involves inducing mitotic activity and desmosomal shedding.31 Retinoids downregulate EGFR expression and activation in EGF-stimulated cells.32 We hypothesize that these oral retinoids decreased the growth stimulus and thereby improved cutaneous signs in the setting of our patient’s transitional cell cancer. Although definitive therapy is malignancy management, our case highlights the utility of adjunctive measures such as oral retinoids and surgical debulking. While previous cases have reported use of retinoids at a lower dosage than used in this case, oral lesions often have only been mildly improved with little impact on other cutaneous symptoms.1,2 In one case of malignant acanthosis nigricans and oral papillomatosis, isotretinoin 25 mg once every 2 to 3 days led to a moderate decrease in hyperkeratosis and papillomas, but the patient was lost to follow-up.3 Our case highlights the use of higher daily doses of oral retinoids for over 9 months, resulting in marked improvement in both the mucosal and cutaneous symptoms of acanthosis nigricans, progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms. Therefore, oral acitretin should be considered as adjuvant therapy for these paraneoplastic conditions.

By reporting this case, we hope to demonstrate the importance of considering other forms of malignancies in the presence of paraneoplastic conditions. Although gastric malignancies more commonly are associated with these conditions, bladder carcinomas also can present with cutaneous manifestations. The presence of these paraneoplastic conditions alone or together rarely is reported in urologic cancers and generally is considered to be an indicator of poor prognosis. Paraneoplastic conditions often develop rapidly and occur in very advanced malignancies.4 The disfiguring presentation in our case also had unusual diagnostic challenges. The presence of these conditions for 8 years and nonmetastatic advanced malignancy suggest a more indolent process and that these signs are not always an indicator of poor prognosis. Future patients with these paraneoplastic conditions may benefit from both a thorough malignancy screen, including cystoscopy, and high daily doses of oral retinoids.

- Stawczyk-Macieja M, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:56-58.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong W-S. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1151-1153.

- Wick MR, Patterson JW. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes [published online January 31, 2019]. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36:211-228.

- Tyler MT, Ficarra G, Silverman S, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with florid papillary oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:445-449.

- Zhang X, Liu R, Liu Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology. 2020;20:1-4.

- Curth HO. Dermatoses and malignant internal tumours. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1955;71:95-107.

- Krawczyk M, Mykala-Cies´la J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

- Singhi MK, Gupta LK, Bansal M, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 year old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:195-196.

- Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E218-E219.

- Yang YH, Zhang RZ, Kang DH, et al. Three paraneoplastic signs in the same patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18966.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Buranathawornsom A, Sirinawasatien A. Diffuse esophageal squamous papillomatosis: a rare disease associated with acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:702-706.

- Muhammad R, Iftikhar N, Sarfraz T, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an indicator of internal malignancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:888-890.

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:573-577.

- Vilas-Sueiro A, Suárez-Amor O, Monteagudo B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis, and tripe palms in a man with gastric adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:438-439.

- Paravina M, Ljubisavljevic´ D. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma—a case report. Serbian J Dermatology Venereol. 2015;7:5-14.

- Kleikamp S, Böhm M, Frosch P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans, papillomatosis mucosae and “tripe” palms in a patient with metastasized gastric carcinoma [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1209-1213.

- Mikhail GR, Fachnie DM, Drukker BH, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:201-202.

- Zhang R, Jiang M, Lei W, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with recurrent bladder cancer: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:951.

- Olek-Hrab K, Silny W, Zaba R, et al. Co-occurrence of acanthosis nigricans and bladder adenocarcinoma-case report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:327-330.

- Canjuga I, Mravak-Stipetic´ M, Kopic´V, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans: case report and comparison with literature reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:91-95.

- Cairo F, Rubino I, Rotundo R, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans as a marker of internal malignancy. a case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1271-1275.

- Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Singh GK, Sen D, Mulajker DS, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:722-725.

- Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433-435.

- Pinto WBVR, Badia BML, Souza PVS, et al. Paraneoplastic motor neuronopathy and malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77:527.

- Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factor–alpha (TGF-alpha)-producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:71-77.

- Billerey C, Chopin D, Aubriot-Lorton MH, et al. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in papillary non-invasive bladder (pTa) tumors. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1955-1959.

- Lee C-J, Lee M-H, Cho Y-Y. Fibroblast and epidermal growth factors utilize different signaling pathways to induce anchorage-independent cell transformation in JB6 Cl41 mouse skin epidermal cells. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:199-208.

- Darmstadt GL, Yokel BK, Horn TD. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1139-1140.

- Sah JF, Eckert RL, Chandraratna RA, et al. Retinoids suppress epidermal growth factor–associated cell proliferation by inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor–dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9728-9735.

- Stawczyk-Macieja M, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:56-58.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong W-S. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1151-1153.

- Wick MR, Patterson JW. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes [published online January 31, 2019]. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36:211-228.

- Tyler MT, Ficarra G, Silverman S, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with florid papillary oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:445-449.

- Zhang X, Liu R, Liu Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology. 2020;20:1-4.

- Curth HO. Dermatoses and malignant internal tumours. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1955;71:95-107.

- Krawczyk M, Mykala-Cies´la J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

- Singhi MK, Gupta LK, Bansal M, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 year old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:195-196.

- Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E218-E219.

- Yang YH, Zhang RZ, Kang DH, et al. Three paraneoplastic signs in the same patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18966.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Buranathawornsom A, Sirinawasatien A. Diffuse esophageal squamous papillomatosis: a rare disease associated with acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:702-706.

- Muhammad R, Iftikhar N, Sarfraz T, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an indicator of internal malignancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:888-890.

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:573-577.

- Vilas-Sueiro A, Suárez-Amor O, Monteagudo B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis, and tripe palms in a man with gastric adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:438-439.

- Paravina M, Ljubisavljevic´ D. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma—a case report. Serbian J Dermatology Venereol. 2015;7:5-14.

- Kleikamp S, Böhm M, Frosch P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans, papillomatosis mucosae and “tripe” palms in a patient with metastasized gastric carcinoma [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1209-1213.

- Mikhail GR, Fachnie DM, Drukker BH, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:201-202.

- Zhang R, Jiang M, Lei W, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with recurrent bladder cancer: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:951.

- Olek-Hrab K, Silny W, Zaba R, et al. Co-occurrence of acanthosis nigricans and bladder adenocarcinoma-case report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:327-330.

- Canjuga I, Mravak-Stipetic´ M, Kopic´V, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans: case report and comparison with literature reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:91-95.

- Cairo F, Rubino I, Rotundo R, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans as a marker of internal malignancy. a case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1271-1275.

- Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Singh GK, Sen D, Mulajker DS, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:722-725.

- Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433-435.

- Pinto WBVR, Badia BML, Souza PVS, et al. Paraneoplastic motor neuronopathy and malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77:527.

- Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factor–alpha (TGF-alpha)-producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:71-77.

- Billerey C, Chopin D, Aubriot-Lorton MH, et al. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in papillary non-invasive bladder (pTa) tumors. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1955-1959.

- Lee C-J, Lee M-H, Cho Y-Y. Fibroblast and epidermal growth factors utilize different signaling pathways to induce anchorage-independent cell transformation in JB6 Cl41 mouse skin epidermal cells. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:199-208.

- Darmstadt GL, Yokel BK, Horn TD. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1139-1140.

- Sah JF, Eckert RL, Chandraratna RA, et al. Retinoids suppress epidermal growth factor–associated cell proliferation by inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor–dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9728-9735.

Practice Points

- Paraneoplastic conditions may present secondary to urologic malignancy. Providers should perform thorough malignancy screening, including urologic cystoscopy, in patients presenting with paraneoplastic signs and no identified malignancy.

- Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, may be used as an adjuvant treatment to treat paraneoplastic cutaneous symptoms. The definitive treatment is malignancy management.

Verrucous Coalescing Dry Papules and Plaques on the Hip and Flank

The Diagnosis: Blaschkitis

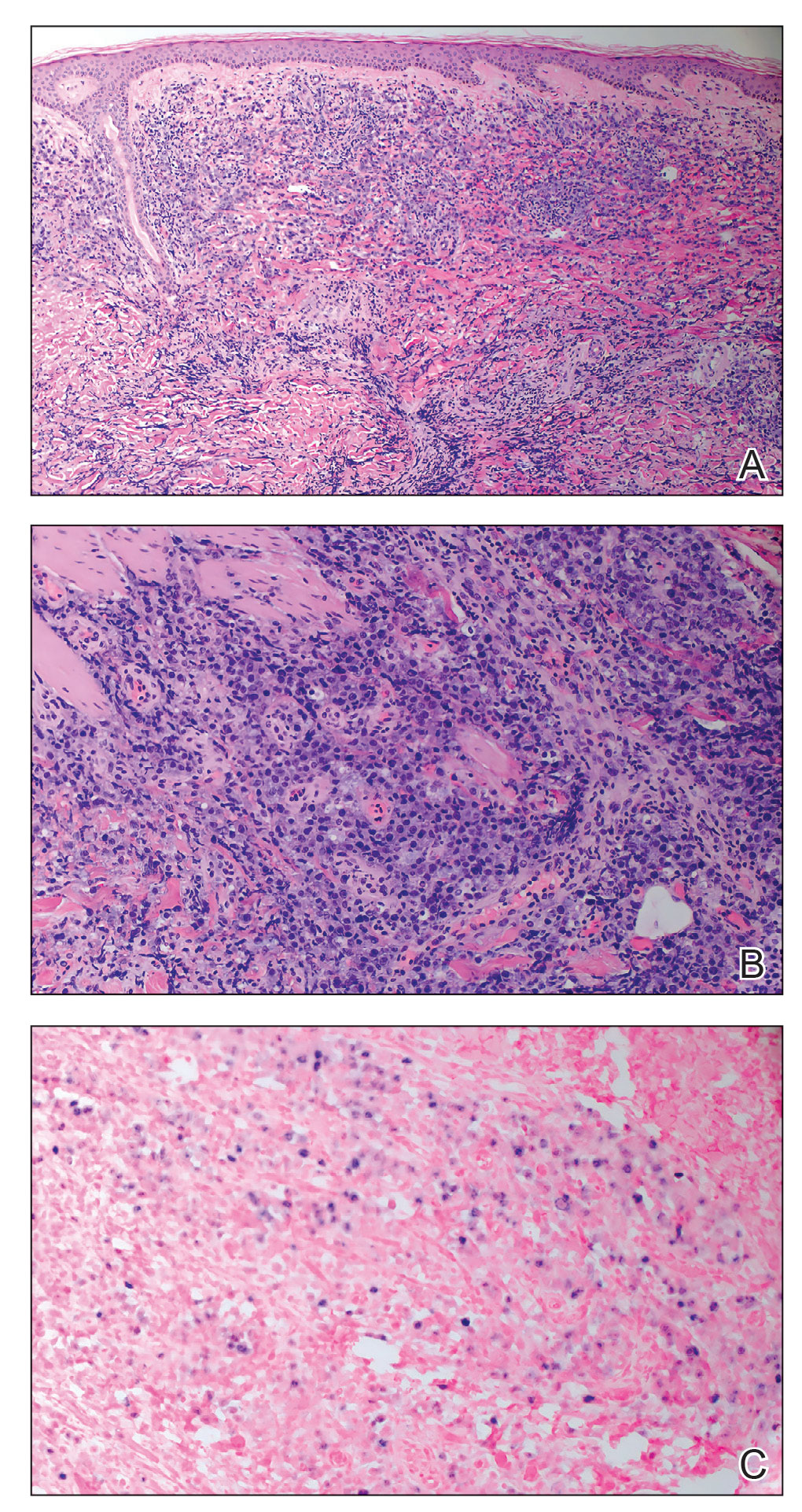

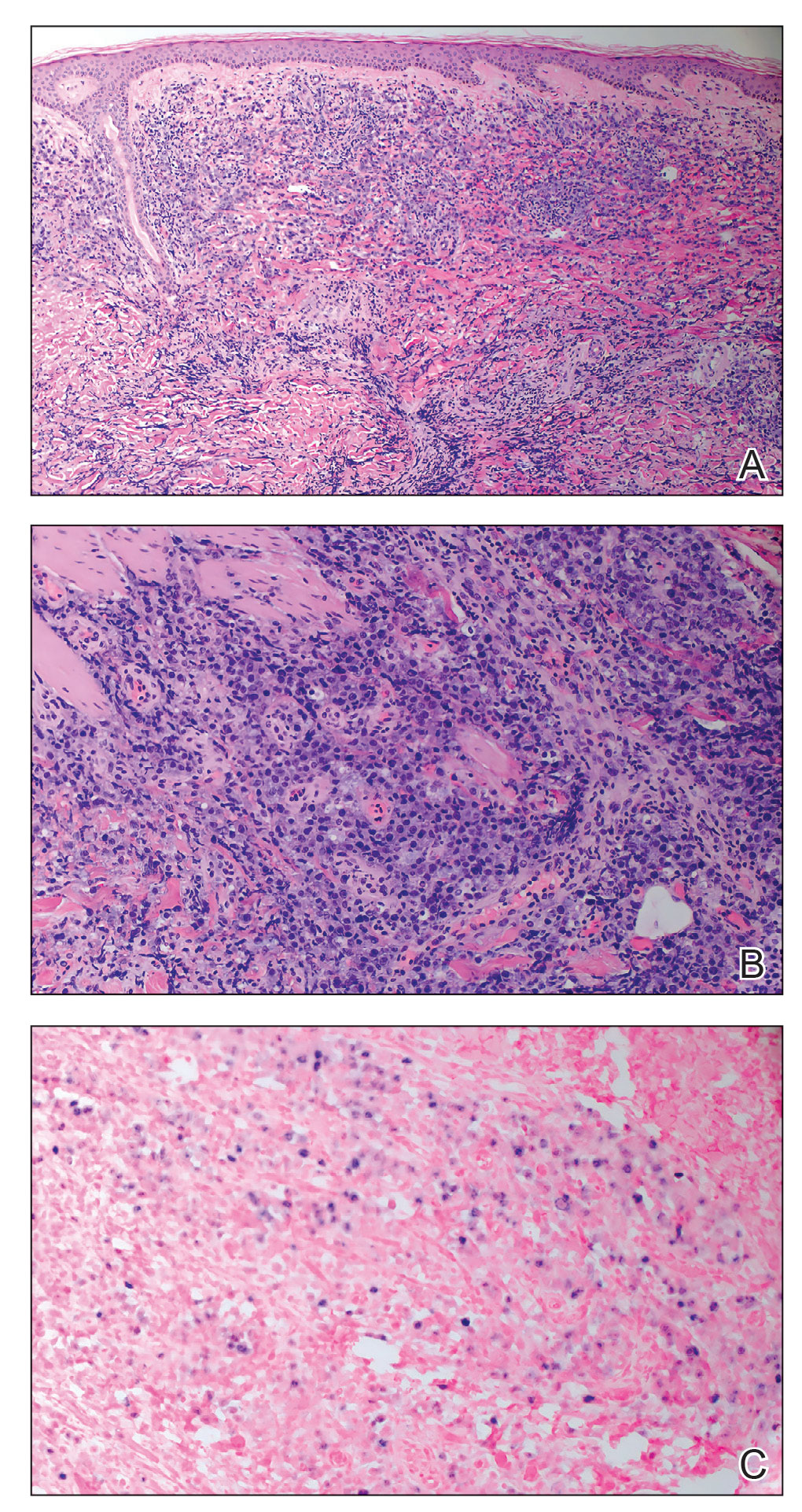

A punch biopsy from the right lateral hip was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed orthokeratosis overlying mild psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia associated with a lichenoid infiltrate composed almost entirely of lymphocytes (Figure). The infiltrate did not entirely obscure the dermoepidermal junction and spared the adnexal structures. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of blaschkitis. The lesions were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily as needed, and the patient reported symptomatic and clinical improvement with this intervention at 4-week follow-up.

Described by Grosshans and Marot1 in 1990, blaschkitis is an acquired inflammatory dermatosis following the lines of Blaschko. It predominantly is seen on the trunk and typically presents with pruritic papules and vesicles. It frequently has a relapsing course and is more commonly found in adults. Blaschkitis is considered a form of cutaneous mosaicism representing somatic mutations affecting epidermal cell growth and migration during embryogenesis. It has been proposed that these aberrant cells are not clinically apparent at birth; however, viral infection and drug or other environmental triggers can induce antigen presentation of the clone cells activating a T cell–mediated inflammatory response.2-4

The differential diagnosis includes other acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses such as lichen striatus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, unilateral lichen planus, linear lichen sclerosus, linear psoriasis, linear fixed drug reaction, lichen nitidus, and others.1,4 Given the overlap in clinical and histopathological presentations of the entities in the differential, it often is difficult to discern the etiology of the papular and vesicular eruption in question. Discrimination of one etiology from the others is further confounded by the fact that these lesions can all be pruritic and initially are treated with topical corticosteroids. A degree of clinical suspicion for blaschkitis coupled with prior understanding of lesional manifestations is helpful in this circumstance. Although classic lichen planus often affects the arms, legs, flexor surfaces, and occasionally the oral mucosa, blaschkitis generally is limited to the trunk. The lesions of lichen planus generally are violaceous, flattopped, polygonal papules that tend to coalesce. They often have a thin, transparent, and adherent scale overlying the papular lesions, and they occasionally demonstrate Wickham striae, which are faint white reticulated networks typically seen in oral mucosal lesions. In the case of lichen nitidus, lesions often follow a geometric line due to the Köbner response, whereas physical trauma from scratching or injury causes lesions to form along the line of insult. Assessing patients for any newly initiated medications can help eliminate lichenoid drug eruptions. Lichen striatus perhaps has the most overlap with blaschkitis, having been described as also following the lines of Blaschko but occurring in children rather than adults. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi also can be distinguished from blaschkitis on this premise, as these lesions arise during the first 5 years of life and generally affect the lower extremities.4,5

Histopathology is somewhat variable but generally includes spongiotic dermatitis with concomitant interface

dermatitis characterized by T-cell infiltration. Spongiosis is a feature less commonly seen in lichen striatus. Lesions can progress over time from spongiotic dermatitis to spongiotic psoriasiform dermatitis and later to spongiotic psoriasiform lichenoid dermatitis.4 Treatment of blaschkitis should begin with reassurance of the benign nature of the dermatosis. Pruritic symptoms can be managed with a course of topical steroids.

Blaschkitis is a rare and self-limiting acquired dermatosis that should be incorporated into the differential diagnosis of Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Further investigation is needed to determine if blaschkitis and lichen striatus represent the ends of a disease spectrum or completely distinct entities.

- Grosshans E, Marot L. Blaschkitis in adults. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:9-15.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis: reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses [published online November 29, 2010]. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Sun BK, Tsao H. X-chromosome inactivation and skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2753-2759.

- Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:261-267.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkitis

A punch biopsy from the right lateral hip was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed orthokeratosis overlying mild psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia associated with a lichenoid infiltrate composed almost entirely of lymphocytes (Figure). The infiltrate did not entirely obscure the dermoepidermal junction and spared the adnexal structures. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of blaschkitis. The lesions were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily as needed, and the patient reported symptomatic and clinical improvement with this intervention at 4-week follow-up.

Described by Grosshans and Marot1 in 1990, blaschkitis is an acquired inflammatory dermatosis following the lines of Blaschko. It predominantly is seen on the trunk and typically presents with pruritic papules and vesicles. It frequently has a relapsing course and is more commonly found in adults. Blaschkitis is considered a form of cutaneous mosaicism representing somatic mutations affecting epidermal cell growth and migration during embryogenesis. It has been proposed that these aberrant cells are not clinically apparent at birth; however, viral infection and drug or other environmental triggers can induce antigen presentation of the clone cells activating a T cell–mediated inflammatory response.2-4

The differential diagnosis includes other acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses such as lichen striatus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, unilateral lichen planus, linear lichen sclerosus, linear psoriasis, linear fixed drug reaction, lichen nitidus, and others.1,4 Given the overlap in clinical and histopathological presentations of the entities in the differential, it often is difficult to discern the etiology of the papular and vesicular eruption in question. Discrimination of one etiology from the others is further confounded by the fact that these lesions can all be pruritic and initially are treated with topical corticosteroids. A degree of clinical suspicion for blaschkitis coupled with prior understanding of lesional manifestations is helpful in this circumstance. Although classic lichen planus often affects the arms, legs, flexor surfaces, and occasionally the oral mucosa, blaschkitis generally is limited to the trunk. The lesions of lichen planus generally are violaceous, flattopped, polygonal papules that tend to coalesce. They often have a thin, transparent, and adherent scale overlying the papular lesions, and they occasionally demonstrate Wickham striae, which are faint white reticulated networks typically seen in oral mucosal lesions. In the case of lichen nitidus, lesions often follow a geometric line due to the Köbner response, whereas physical trauma from scratching or injury causes lesions to form along the line of insult. Assessing patients for any newly initiated medications can help eliminate lichenoid drug eruptions. Lichen striatus perhaps has the most overlap with blaschkitis, having been described as also following the lines of Blaschko but occurring in children rather than adults. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi also can be distinguished from blaschkitis on this premise, as these lesions arise during the first 5 years of life and generally affect the lower extremities.4,5

Histopathology is somewhat variable but generally includes spongiotic dermatitis with concomitant interface

dermatitis characterized by T-cell infiltration. Spongiosis is a feature less commonly seen in lichen striatus. Lesions can progress over time from spongiotic dermatitis to spongiotic psoriasiform dermatitis and later to spongiotic psoriasiform lichenoid dermatitis.4 Treatment of blaschkitis should begin with reassurance of the benign nature of the dermatosis. Pruritic symptoms can be managed with a course of topical steroids.

Blaschkitis is a rare and self-limiting acquired dermatosis that should be incorporated into the differential diagnosis of Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Further investigation is needed to determine if blaschkitis and lichen striatus represent the ends of a disease spectrum or completely distinct entities.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkitis

A punch biopsy from the right lateral hip was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed orthokeratosis overlying mild psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia associated with a lichenoid infiltrate composed almost entirely of lymphocytes (Figure). The infiltrate did not entirely obscure the dermoepidermal junction and spared the adnexal structures. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of blaschkitis. The lesions were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily as needed, and the patient reported symptomatic and clinical improvement with this intervention at 4-week follow-up.

Described by Grosshans and Marot1 in 1990, blaschkitis is an acquired inflammatory dermatosis following the lines of Blaschko. It predominantly is seen on the trunk and typically presents with pruritic papules and vesicles. It frequently has a relapsing course and is more commonly found in adults. Blaschkitis is considered a form of cutaneous mosaicism representing somatic mutations affecting epidermal cell growth and migration during embryogenesis. It has been proposed that these aberrant cells are not clinically apparent at birth; however, viral infection and drug or other environmental triggers can induce antigen presentation of the clone cells activating a T cell–mediated inflammatory response.2-4

The differential diagnosis includes other acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses such as lichen striatus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, unilateral lichen planus, linear lichen sclerosus, linear psoriasis, linear fixed drug reaction, lichen nitidus, and others.1,4 Given the overlap in clinical and histopathological presentations of the entities in the differential, it often is difficult to discern the etiology of the papular and vesicular eruption in question. Discrimination of one etiology from the others is further confounded by the fact that these lesions can all be pruritic and initially are treated with topical corticosteroids. A degree of clinical suspicion for blaschkitis coupled with prior understanding of lesional manifestations is helpful in this circumstance. Although classic lichen planus often affects the arms, legs, flexor surfaces, and occasionally the oral mucosa, blaschkitis generally is limited to the trunk. The lesions of lichen planus generally are violaceous, flattopped, polygonal papules that tend to coalesce. They often have a thin, transparent, and adherent scale overlying the papular lesions, and they occasionally demonstrate Wickham striae, which are faint white reticulated networks typically seen in oral mucosal lesions. In the case of lichen nitidus, lesions often follow a geometric line due to the Köbner response, whereas physical trauma from scratching or injury causes lesions to form along the line of insult. Assessing patients for any newly initiated medications can help eliminate lichenoid drug eruptions. Lichen striatus perhaps has the most overlap with blaschkitis, having been described as also following the lines of Blaschko but occurring in children rather than adults. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi also can be distinguished from blaschkitis on this premise, as these lesions arise during the first 5 years of life and generally affect the lower extremities.4,5

Histopathology is somewhat variable but generally includes spongiotic dermatitis with concomitant interface

dermatitis characterized by T-cell infiltration. Spongiosis is a feature less commonly seen in lichen striatus. Lesions can progress over time from spongiotic dermatitis to spongiotic psoriasiform dermatitis and later to spongiotic psoriasiform lichenoid dermatitis.4 Treatment of blaschkitis should begin with reassurance of the benign nature of the dermatosis. Pruritic symptoms can be managed with a course of topical steroids.

Blaschkitis is a rare and self-limiting acquired dermatosis that should be incorporated into the differential diagnosis of Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Further investigation is needed to determine if blaschkitis and lichen striatus represent the ends of a disease spectrum or completely distinct entities.

- Grosshans E, Marot L. Blaschkitis in adults. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:9-15.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis: reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses [published online November 29, 2010]. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Sun BK, Tsao H. X-chromosome inactivation and skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2753-2759.

- Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:261-267.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Grosshans E, Marot L. Blaschkitis in adults. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:9-15.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis: reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses [published online November 29, 2010]. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Sun BK, Tsao H. X-chromosome inactivation and skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2753-2759.