User login

Postherpetic Isotopic Responses With 3 Simultaneously Occurring Reactions Following Herpes Zoster

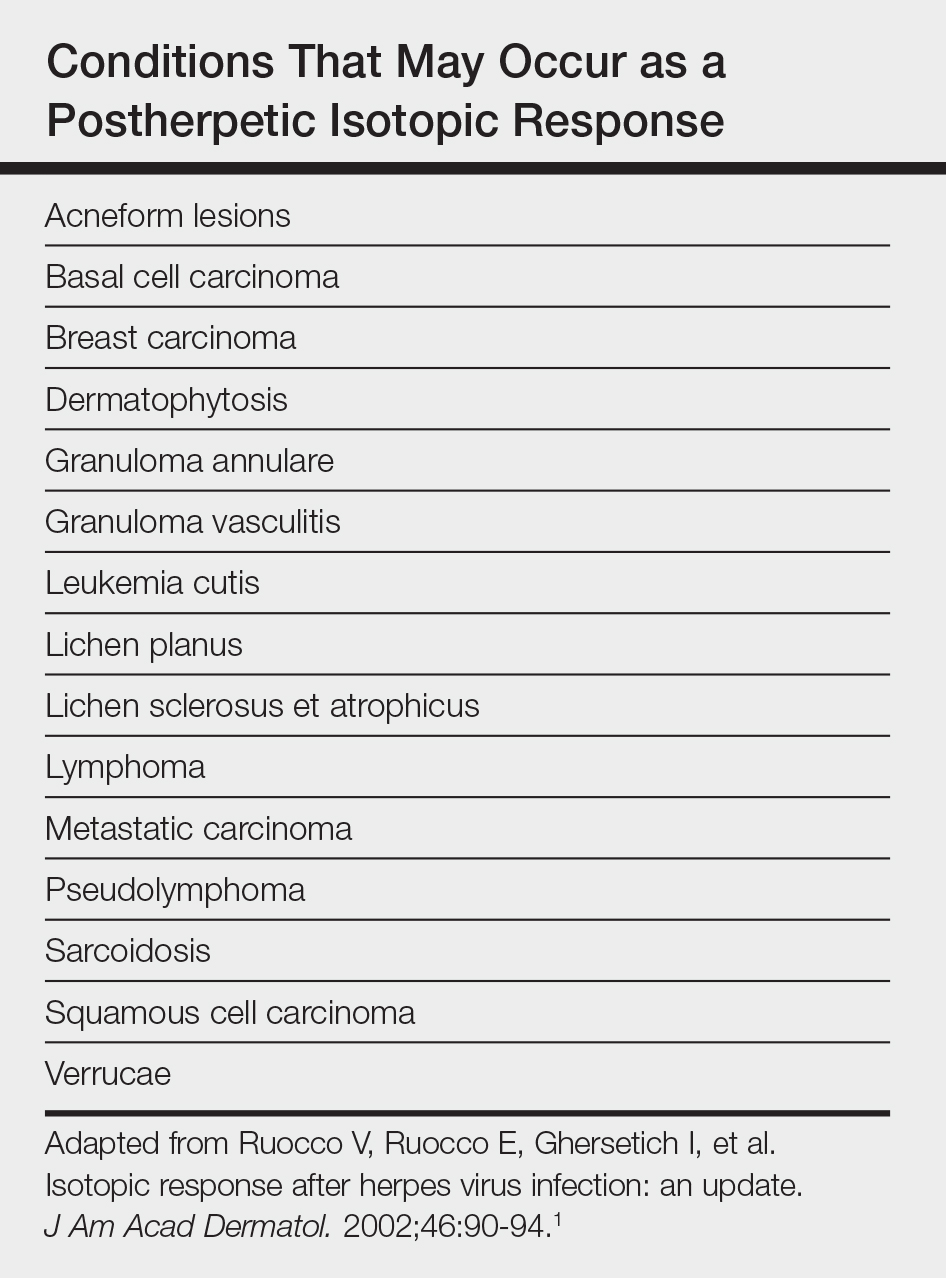

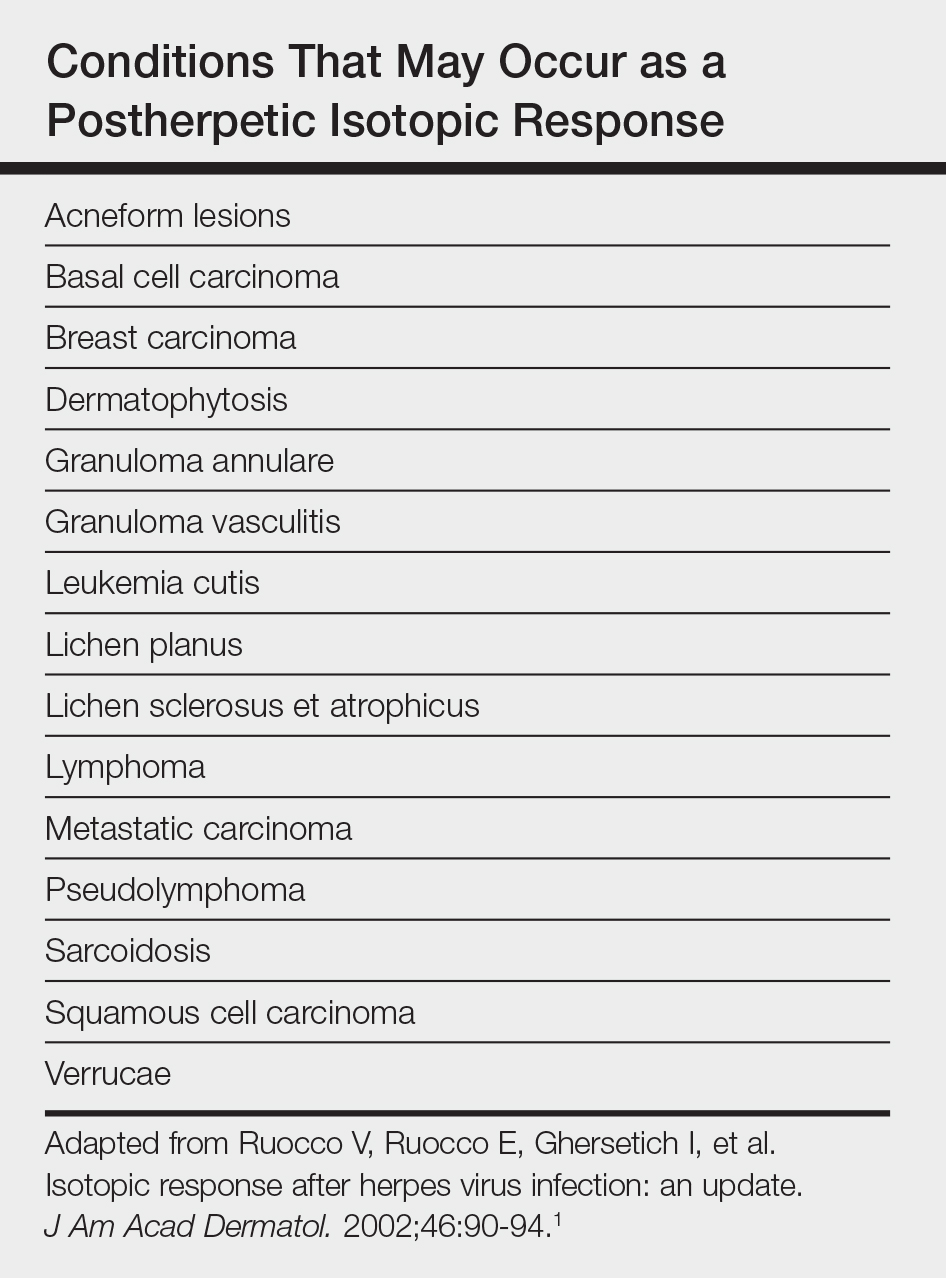

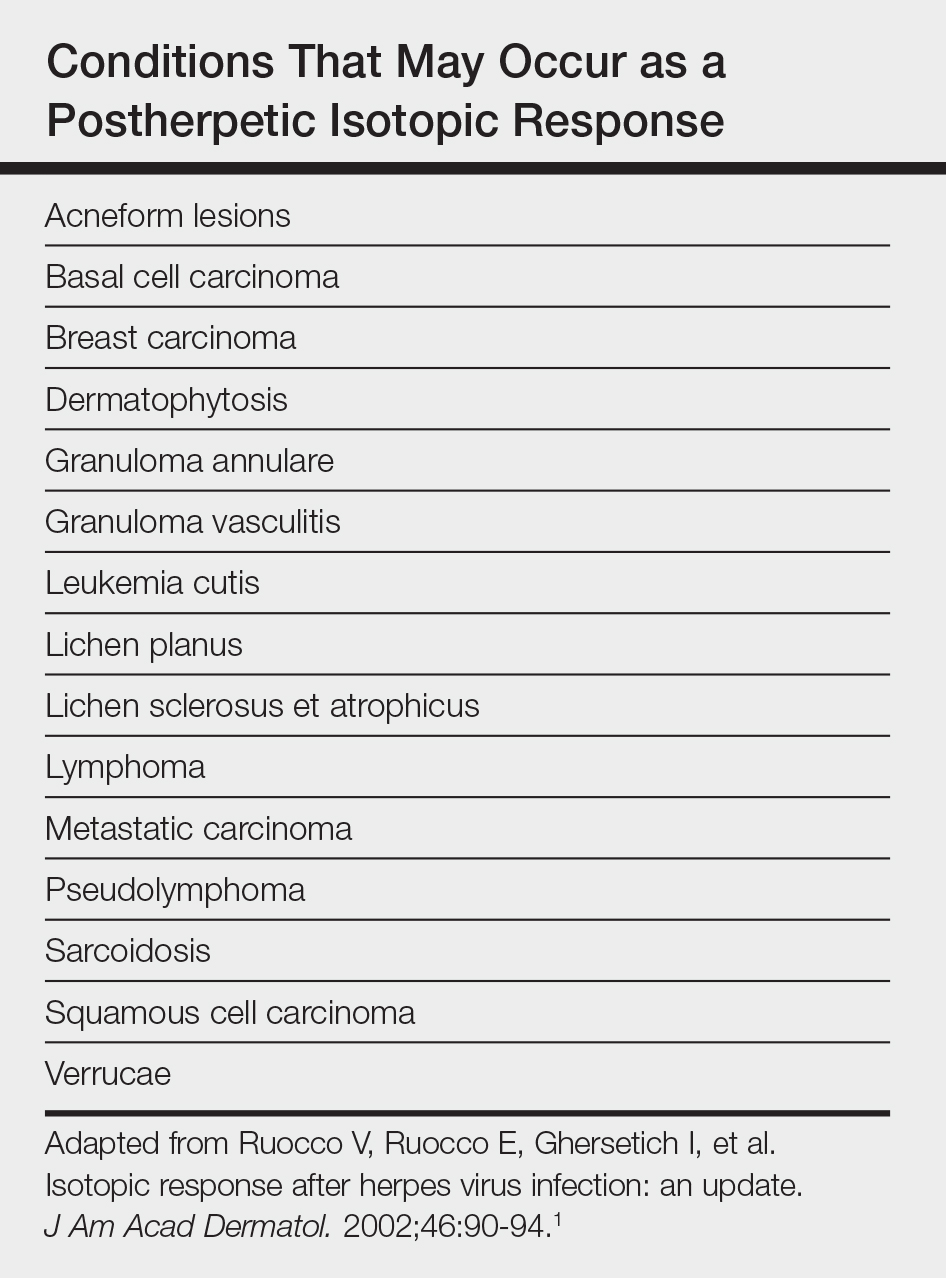

Postherpetic isotopic response (PHIR) refers to the occurrence of a second disease manifesting at the site of prior herpes infection. Many forms of PHIR have been described (Table), with postzoster granulomatous dermatitis (eg, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitis) being the most common.1 Both primary and metastatic malignancies also can occur at the site of a prior herpes infection. Rarely, multiple types of PHIRs occur simultaneously. We report a case of 3 simultaneously occurring postzoster isotopic responses--granulomatous dermatitis, vasculitis, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)--and review the various types of PHIRs.

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a 4-year history of CLL was admitted to the hospital due to a painful rash on the left side of the face of 2 months' duration. Erythematous to violaceous plaques with surrounding papules and nodules were present on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp with focal ulceration. Two months prior, the patient had unilateral vesicular lesions in the same distribution (Figure 1A). He initially received a 3-week course of acyclovir for a presumed herpes zoster infection and showed prompt improvement in the vesicular lesions. After resolution of the vesicles, papules and nodules began developing in the prior vesicular areas and he was treated with another course of acyclovir with the addition of clindamycin. When the lesions continued to progress and spread down the left side of the forehead and upper eyelid (Figure 1B), he was admitted to the hospital and assessed by the consultative dermatology team. No fevers, chills, or other systemic symptoms were reported.

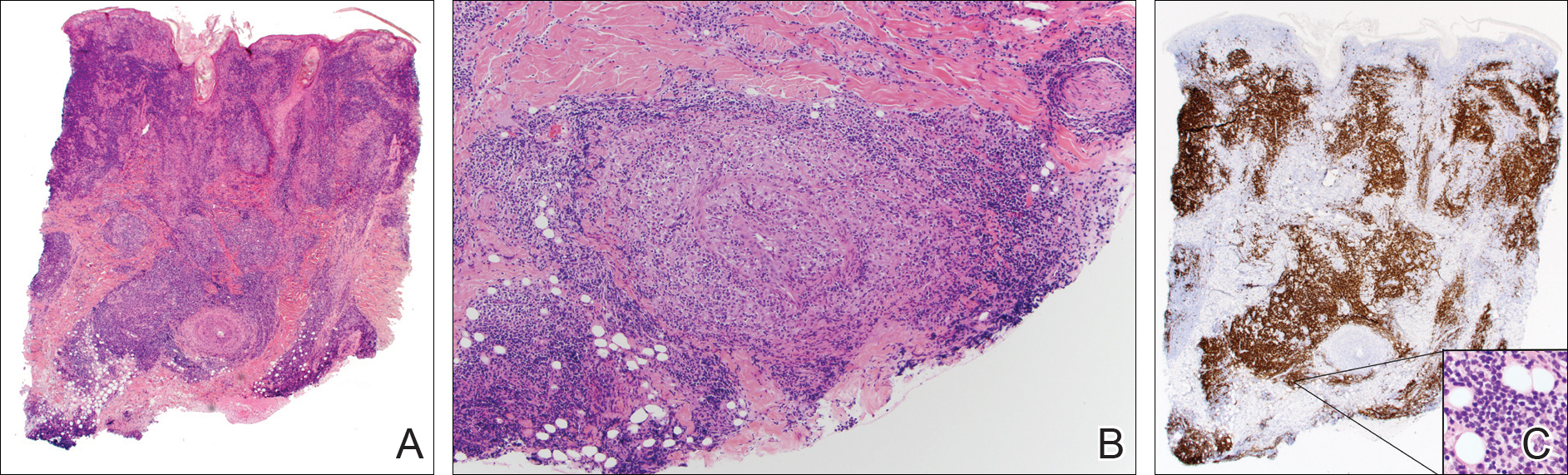

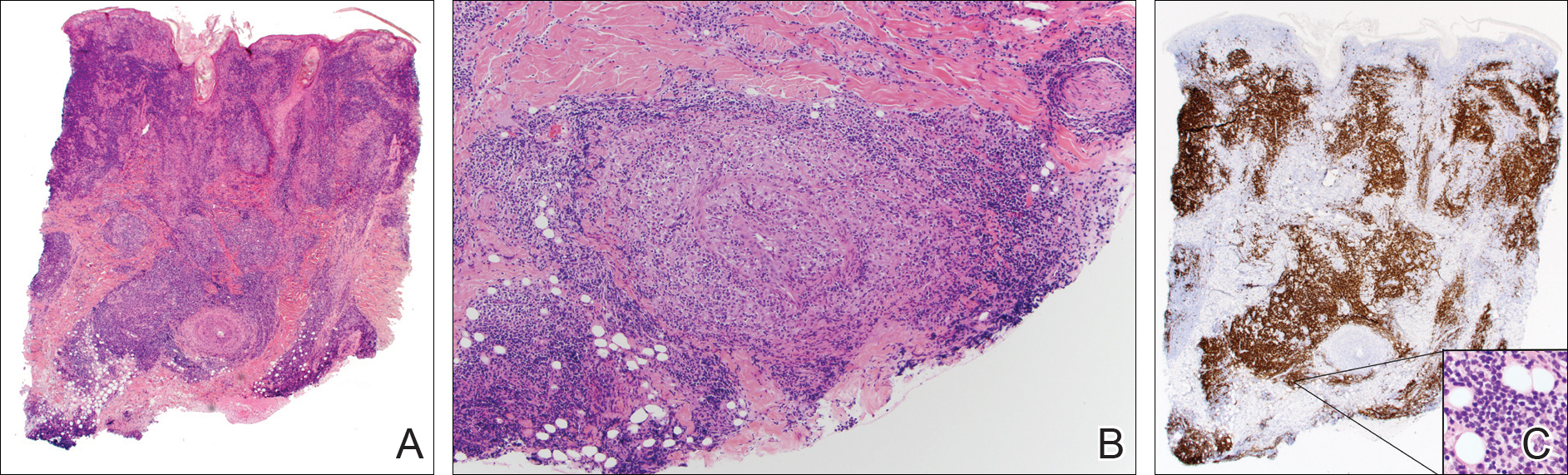

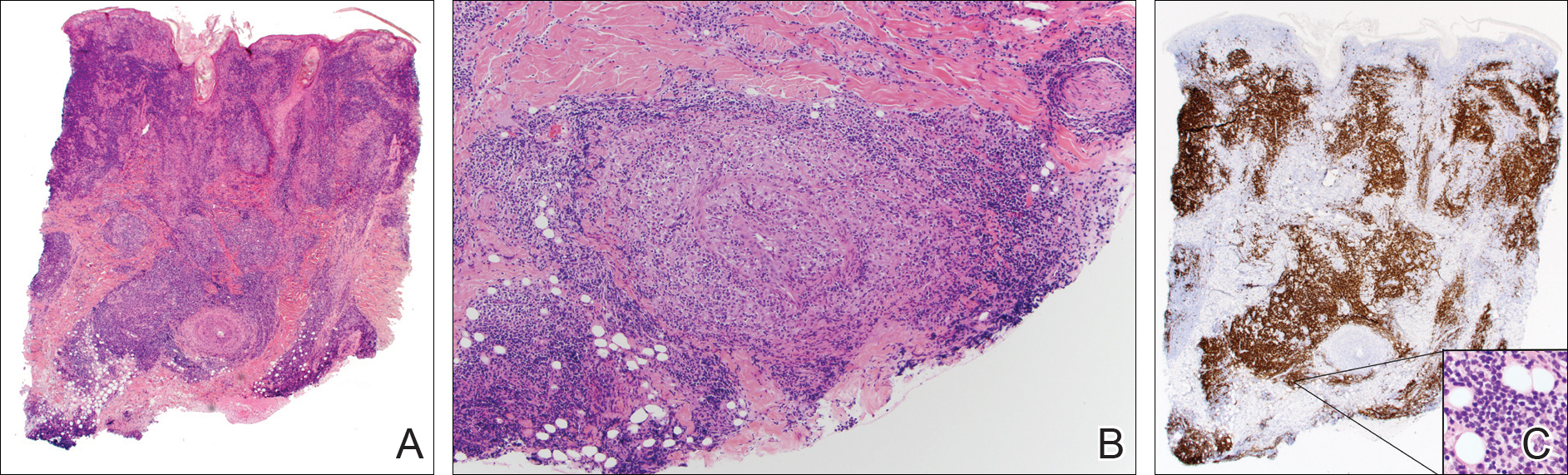

A punch biopsy showed a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate filling the dermis and extending into the subcutis with nodular collections of histiocytes and some plasma cells scattered throughout (Figure 2A). A medium-vessel vasculitis was present with numerous histiocytes and lymphocytes infiltrating the muscular wall of a blood vessel in the subcutis (Figure 2B). CD3 and CD20 immunostaining showed an overwhelming majority of B cells, some with enlarged atypical nuclei and a smaller number of reactive T lymphocytes (Figure 2C). CD5 and CD43 were diffusely positive in the B cells, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous CLL. CD23 staining was focally positive. Immunostaining for κ and λ light chains showed a marginal κ predominance. An additional biopsy for tissue culture was negative. A diagnosis of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with vasculitis and cutaneous CLL was rendered.

Comment

Postherpetic Cutaneous Reactions

Various cutaneous reactions can occur at the site of prior herpes infection. The most frequently reported reactions are granulomatous dermatitides such as granuloma annulare, granulomatous vasculitis, granulomatous folliculitis, sarcoidosis, and nonspecific granulomatous dermatitis.1 Primary cutaneous malignancies and cutaneous metastases, including hematologic malignancies, have also been reported after herpetic infections. In a review of 127 patients with postherpetic cutaneous reactions, 47 had a granulomatous dermatitis, 32 had nonhematologic malignancies, 18 had leukemic or lymphomatous/pseudolymphomatous infiltrates, 10 had acneform lesions, 9 had nongranulomatous dermatitides such as lichen planus and allergic contact dermatitis, and 8 had nonherpetic skin infections; single cases of reactive perforating collagenosis, nodular solar degeneration, and a keloid also were reported.1

Pathogenesis of Cutaneous Reactions

Although postherpetic cutaneous reactions can develop in healthy individuals, they occur more often in immunocompromised patients. Postherpetic isotopic response has been used to describe the development of a nonherpetic disease at the site of prior herpes infection.2 Several different theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of the PHIR, including an unusual delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to residual viral antigen or host-tissue antigen altered by the virus. This delayed-type hypersensitivity explanation is supported by the presence of helper T cells, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, varicella major viral envelope glycoproteins, and viral DNA in postherpetic granulomatous lesions3; however, cases that lack detectable virus and viral DNA in these types of lesions also have been reported.4

A second hypothesis proposes that inflammatory or viral-induced alteration of the local microvasculature results in increased site-specific susceptibility to subsequent inflammatory responses and drives these isotopic reactions.2,3 Damage or alteration of local peripheral nerves leading to abnormal release of specific neuromediators involved in regulating cutaneous inflammatory responses also may play a role.5 Varicella-zoster virus utilizes the peripheral nervous system to establish latent infection and can cause destruction of alpha delta and C nerve fibers in the dermis.1 Destruction of nerve fibers may indirectly influence the local immune system by altering the release of neuromediators such as substance P (known to increase blood vessel permeability, increase fibrinolytic activity, and induce mast cell secretion), vasoactive intestinal peptide (enhances monocyte migration, increases histamine release from mast cells, and inhibits natural killer cell activity), calcitonin gene-related peptide (increases vascular permeability, endothelial cell proliferation, and the accumulation of neutrophils), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (induces anti-inflammatory cytokines). Disruption of the nervous system resulting in an altered local immune response also has been observed in other settings (eg, amputees who develop inflammatory diseases, bacterial and fungal infections, and cutaneous neoplasms confined to stump skin).1

Malignancies in PHIR

The granulomatous inflammation in PHIRs is a nonneoplastic inflammatory reaction with a variable lymphocytic component. Granuloma formation can be seen in both reactive inflammatory infiltrates and in cutaneous involvement of leukemias and lymphomas. Leukemia cutis has been reported in 4% to 20% of patients with CLL/small lymphocytic leukemia.6 In one series of 42 patients with CLL, the malignant cells were confined to the site of postherpetic scars in 14% (6/42) of patients.5 Sixteen percent (7/42) of patients had no prior diagnosis of CLL at the time they developed leukemia cutis, including one patient with leukemia cutis in a postzoster scar. The mechanism involved in the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes within postzoster scars has not been fully characterized. The idea that postzoster sites represent a site of least resistance for cutaneous infiltration of CLL due to the changes from prior inflammatory responses has been proposed.7

Combined CLL and granulomatous dermatitis at prior sites of herpes zoster was first reported in 1990.8 In 1995, Cerroni et al9 reported a series of 5 patients with cutaneous CLL following herpes zoster or herpes simplex virus infection. Three of those patients also demonstrated granuloma formation.9 Establishing a new diagnosis of CLL from a biopsy of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with an associated lymphoid infiltrate also has been reported.10 Cerroni et al9 postulated that cutaneous CLL in post-herpes zoster scars may occur more frequently than reported due to misdiagnoses of CLL as pseudolymphoma. Two additional cases of postherpetic cutaneous CLL and granulomatous dermatitis have been reported since 1995.7,10

Diagnosis of Multiple PHIRs

The presence of 3 concurrent PHIRs is rare. The patient in this report had postzoster cutaneous CLL with an associated granulomatous dermatitis and medium-vessel vasculitis. One other case with these 3 findings was reported by Elgoweini et al.7 Overlooking important diagnoses when multiple findings are present in a biopsy can lead to diagnostic delay and incorrect treatment; we highlighted the importance of careful examination of biopsies in PHIRs to ensure diagnostic accuracy. In cases of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis, assessment of the lymphocytic component should not be overlooked. The presence of a dense lymphocytic infiltrate should raise the possibility of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as CLL, even in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If initial immunostaining discloses a predominantly B-cell infiltrate, additional immuno-stains (eg, CD5, CD23, CD43) and/or genetic testing for monoclonality should be pursued.

Conclusion

Clinicians and dermatopathologists should be aware of the multiplicity of postherpetic isotopic responses and consider immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between a genuine lymphoma such as CLL and pseudolymphoma in PHIRs with a lymphoid infiltrate.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpes virus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf's isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Snow J, el-Azhary R, Gibson L, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis associated with herpes virus: a persistent, painful, postherpetic papular eruption. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:851-853.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Hofler G, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 42 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1000-1010.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Elgoweini M, Blessing K, Jackson R, et al. Coexistent granulomatous vasculitis and leukaemia cutis in a patient with resolving herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:749-751.

- Pujol RM, Matias-Guiu X, Planaguma M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and cutaneous granulomas at sites of herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:652-654.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Kerl H. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia arising at the site of herpes zoster and herpes simplex scars. Cancer. 1995;76:26-31.

- Trojjet S, Hammami H, Zaraa I, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by a granulomatous zosteriform eruption. Skinmed. 2012;10:50-52.

Postherpetic isotopic response (PHIR) refers to the occurrence of a second disease manifesting at the site of prior herpes infection. Many forms of PHIR have been described (Table), with postzoster granulomatous dermatitis (eg, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitis) being the most common.1 Both primary and metastatic malignancies also can occur at the site of a prior herpes infection. Rarely, multiple types of PHIRs occur simultaneously. We report a case of 3 simultaneously occurring postzoster isotopic responses--granulomatous dermatitis, vasculitis, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)--and review the various types of PHIRs.

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a 4-year history of CLL was admitted to the hospital due to a painful rash on the left side of the face of 2 months' duration. Erythematous to violaceous plaques with surrounding papules and nodules were present on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp with focal ulceration. Two months prior, the patient had unilateral vesicular lesions in the same distribution (Figure 1A). He initially received a 3-week course of acyclovir for a presumed herpes zoster infection and showed prompt improvement in the vesicular lesions. After resolution of the vesicles, papules and nodules began developing in the prior vesicular areas and he was treated with another course of acyclovir with the addition of clindamycin. When the lesions continued to progress and spread down the left side of the forehead and upper eyelid (Figure 1B), he was admitted to the hospital and assessed by the consultative dermatology team. No fevers, chills, or other systemic symptoms were reported.

A punch biopsy showed a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate filling the dermis and extending into the subcutis with nodular collections of histiocytes and some plasma cells scattered throughout (Figure 2A). A medium-vessel vasculitis was present with numerous histiocytes and lymphocytes infiltrating the muscular wall of a blood vessel in the subcutis (Figure 2B). CD3 and CD20 immunostaining showed an overwhelming majority of B cells, some with enlarged atypical nuclei and a smaller number of reactive T lymphocytes (Figure 2C). CD5 and CD43 were diffusely positive in the B cells, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous CLL. CD23 staining was focally positive. Immunostaining for κ and λ light chains showed a marginal κ predominance. An additional biopsy for tissue culture was negative. A diagnosis of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with vasculitis and cutaneous CLL was rendered.

Comment

Postherpetic Cutaneous Reactions

Various cutaneous reactions can occur at the site of prior herpes infection. The most frequently reported reactions are granulomatous dermatitides such as granuloma annulare, granulomatous vasculitis, granulomatous folliculitis, sarcoidosis, and nonspecific granulomatous dermatitis.1 Primary cutaneous malignancies and cutaneous metastases, including hematologic malignancies, have also been reported after herpetic infections. In a review of 127 patients with postherpetic cutaneous reactions, 47 had a granulomatous dermatitis, 32 had nonhematologic malignancies, 18 had leukemic or lymphomatous/pseudolymphomatous infiltrates, 10 had acneform lesions, 9 had nongranulomatous dermatitides such as lichen planus and allergic contact dermatitis, and 8 had nonherpetic skin infections; single cases of reactive perforating collagenosis, nodular solar degeneration, and a keloid also were reported.1

Pathogenesis of Cutaneous Reactions

Although postherpetic cutaneous reactions can develop in healthy individuals, they occur more often in immunocompromised patients. Postherpetic isotopic response has been used to describe the development of a nonherpetic disease at the site of prior herpes infection.2 Several different theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of the PHIR, including an unusual delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to residual viral antigen or host-tissue antigen altered by the virus. This delayed-type hypersensitivity explanation is supported by the presence of helper T cells, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, varicella major viral envelope glycoproteins, and viral DNA in postherpetic granulomatous lesions3; however, cases that lack detectable virus and viral DNA in these types of lesions also have been reported.4

A second hypothesis proposes that inflammatory or viral-induced alteration of the local microvasculature results in increased site-specific susceptibility to subsequent inflammatory responses and drives these isotopic reactions.2,3 Damage or alteration of local peripheral nerves leading to abnormal release of specific neuromediators involved in regulating cutaneous inflammatory responses also may play a role.5 Varicella-zoster virus utilizes the peripheral nervous system to establish latent infection and can cause destruction of alpha delta and C nerve fibers in the dermis.1 Destruction of nerve fibers may indirectly influence the local immune system by altering the release of neuromediators such as substance P (known to increase blood vessel permeability, increase fibrinolytic activity, and induce mast cell secretion), vasoactive intestinal peptide (enhances monocyte migration, increases histamine release from mast cells, and inhibits natural killer cell activity), calcitonin gene-related peptide (increases vascular permeability, endothelial cell proliferation, and the accumulation of neutrophils), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (induces anti-inflammatory cytokines). Disruption of the nervous system resulting in an altered local immune response also has been observed in other settings (eg, amputees who develop inflammatory diseases, bacterial and fungal infections, and cutaneous neoplasms confined to stump skin).1

Malignancies in PHIR

The granulomatous inflammation in PHIRs is a nonneoplastic inflammatory reaction with a variable lymphocytic component. Granuloma formation can be seen in both reactive inflammatory infiltrates and in cutaneous involvement of leukemias and lymphomas. Leukemia cutis has been reported in 4% to 20% of patients with CLL/small lymphocytic leukemia.6 In one series of 42 patients with CLL, the malignant cells were confined to the site of postherpetic scars in 14% (6/42) of patients.5 Sixteen percent (7/42) of patients had no prior diagnosis of CLL at the time they developed leukemia cutis, including one patient with leukemia cutis in a postzoster scar. The mechanism involved in the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes within postzoster scars has not been fully characterized. The idea that postzoster sites represent a site of least resistance for cutaneous infiltration of CLL due to the changes from prior inflammatory responses has been proposed.7

Combined CLL and granulomatous dermatitis at prior sites of herpes zoster was first reported in 1990.8 In 1995, Cerroni et al9 reported a series of 5 patients with cutaneous CLL following herpes zoster or herpes simplex virus infection. Three of those patients also demonstrated granuloma formation.9 Establishing a new diagnosis of CLL from a biopsy of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with an associated lymphoid infiltrate also has been reported.10 Cerroni et al9 postulated that cutaneous CLL in post-herpes zoster scars may occur more frequently than reported due to misdiagnoses of CLL as pseudolymphoma. Two additional cases of postherpetic cutaneous CLL and granulomatous dermatitis have been reported since 1995.7,10

Diagnosis of Multiple PHIRs

The presence of 3 concurrent PHIRs is rare. The patient in this report had postzoster cutaneous CLL with an associated granulomatous dermatitis and medium-vessel vasculitis. One other case with these 3 findings was reported by Elgoweini et al.7 Overlooking important diagnoses when multiple findings are present in a biopsy can lead to diagnostic delay and incorrect treatment; we highlighted the importance of careful examination of biopsies in PHIRs to ensure diagnostic accuracy. In cases of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis, assessment of the lymphocytic component should not be overlooked. The presence of a dense lymphocytic infiltrate should raise the possibility of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as CLL, even in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If initial immunostaining discloses a predominantly B-cell infiltrate, additional immuno-stains (eg, CD5, CD23, CD43) and/or genetic testing for monoclonality should be pursued.

Conclusion

Clinicians and dermatopathologists should be aware of the multiplicity of postherpetic isotopic responses and consider immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between a genuine lymphoma such as CLL and pseudolymphoma in PHIRs with a lymphoid infiltrate.

Postherpetic isotopic response (PHIR) refers to the occurrence of a second disease manifesting at the site of prior herpes infection. Many forms of PHIR have been described (Table), with postzoster granulomatous dermatitis (eg, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitis) being the most common.1 Both primary and metastatic malignancies also can occur at the site of a prior herpes infection. Rarely, multiple types of PHIRs occur simultaneously. We report a case of 3 simultaneously occurring postzoster isotopic responses--granulomatous dermatitis, vasculitis, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)--and review the various types of PHIRs.

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a 4-year history of CLL was admitted to the hospital due to a painful rash on the left side of the face of 2 months' duration. Erythematous to violaceous plaques with surrounding papules and nodules were present on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp with focal ulceration. Two months prior, the patient had unilateral vesicular lesions in the same distribution (Figure 1A). He initially received a 3-week course of acyclovir for a presumed herpes zoster infection and showed prompt improvement in the vesicular lesions. After resolution of the vesicles, papules and nodules began developing in the prior vesicular areas and he was treated with another course of acyclovir with the addition of clindamycin. When the lesions continued to progress and spread down the left side of the forehead and upper eyelid (Figure 1B), he was admitted to the hospital and assessed by the consultative dermatology team. No fevers, chills, or other systemic symptoms were reported.

A punch biopsy showed a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate filling the dermis and extending into the subcutis with nodular collections of histiocytes and some plasma cells scattered throughout (Figure 2A). A medium-vessel vasculitis was present with numerous histiocytes and lymphocytes infiltrating the muscular wall of a blood vessel in the subcutis (Figure 2B). CD3 and CD20 immunostaining showed an overwhelming majority of B cells, some with enlarged atypical nuclei and a smaller number of reactive T lymphocytes (Figure 2C). CD5 and CD43 were diffusely positive in the B cells, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous CLL. CD23 staining was focally positive. Immunostaining for κ and λ light chains showed a marginal κ predominance. An additional biopsy for tissue culture was negative. A diagnosis of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with vasculitis and cutaneous CLL was rendered.

Comment

Postherpetic Cutaneous Reactions

Various cutaneous reactions can occur at the site of prior herpes infection. The most frequently reported reactions are granulomatous dermatitides such as granuloma annulare, granulomatous vasculitis, granulomatous folliculitis, sarcoidosis, and nonspecific granulomatous dermatitis.1 Primary cutaneous malignancies and cutaneous metastases, including hematologic malignancies, have also been reported after herpetic infections. In a review of 127 patients with postherpetic cutaneous reactions, 47 had a granulomatous dermatitis, 32 had nonhematologic malignancies, 18 had leukemic or lymphomatous/pseudolymphomatous infiltrates, 10 had acneform lesions, 9 had nongranulomatous dermatitides such as lichen planus and allergic contact dermatitis, and 8 had nonherpetic skin infections; single cases of reactive perforating collagenosis, nodular solar degeneration, and a keloid also were reported.1

Pathogenesis of Cutaneous Reactions

Although postherpetic cutaneous reactions can develop in healthy individuals, they occur more often in immunocompromised patients. Postherpetic isotopic response has been used to describe the development of a nonherpetic disease at the site of prior herpes infection.2 Several different theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of the PHIR, including an unusual delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to residual viral antigen or host-tissue antigen altered by the virus. This delayed-type hypersensitivity explanation is supported by the presence of helper T cells, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, varicella major viral envelope glycoproteins, and viral DNA in postherpetic granulomatous lesions3; however, cases that lack detectable virus and viral DNA in these types of lesions also have been reported.4

A second hypothesis proposes that inflammatory or viral-induced alteration of the local microvasculature results in increased site-specific susceptibility to subsequent inflammatory responses and drives these isotopic reactions.2,3 Damage or alteration of local peripheral nerves leading to abnormal release of specific neuromediators involved in regulating cutaneous inflammatory responses also may play a role.5 Varicella-zoster virus utilizes the peripheral nervous system to establish latent infection and can cause destruction of alpha delta and C nerve fibers in the dermis.1 Destruction of nerve fibers may indirectly influence the local immune system by altering the release of neuromediators such as substance P (known to increase blood vessel permeability, increase fibrinolytic activity, and induce mast cell secretion), vasoactive intestinal peptide (enhances monocyte migration, increases histamine release from mast cells, and inhibits natural killer cell activity), calcitonin gene-related peptide (increases vascular permeability, endothelial cell proliferation, and the accumulation of neutrophils), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (induces anti-inflammatory cytokines). Disruption of the nervous system resulting in an altered local immune response also has been observed in other settings (eg, amputees who develop inflammatory diseases, bacterial and fungal infections, and cutaneous neoplasms confined to stump skin).1

Malignancies in PHIR

The granulomatous inflammation in PHIRs is a nonneoplastic inflammatory reaction with a variable lymphocytic component. Granuloma formation can be seen in both reactive inflammatory infiltrates and in cutaneous involvement of leukemias and lymphomas. Leukemia cutis has been reported in 4% to 20% of patients with CLL/small lymphocytic leukemia.6 In one series of 42 patients with CLL, the malignant cells were confined to the site of postherpetic scars in 14% (6/42) of patients.5 Sixteen percent (7/42) of patients had no prior diagnosis of CLL at the time they developed leukemia cutis, including one patient with leukemia cutis in a postzoster scar. The mechanism involved in the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes within postzoster scars has not been fully characterized. The idea that postzoster sites represent a site of least resistance for cutaneous infiltration of CLL due to the changes from prior inflammatory responses has been proposed.7

Combined CLL and granulomatous dermatitis at prior sites of herpes zoster was first reported in 1990.8 In 1995, Cerroni et al9 reported a series of 5 patients with cutaneous CLL following herpes zoster or herpes simplex virus infection. Three of those patients also demonstrated granuloma formation.9 Establishing a new diagnosis of CLL from a biopsy of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with an associated lymphoid infiltrate also has been reported.10 Cerroni et al9 postulated that cutaneous CLL in post-herpes zoster scars may occur more frequently than reported due to misdiagnoses of CLL as pseudolymphoma. Two additional cases of postherpetic cutaneous CLL and granulomatous dermatitis have been reported since 1995.7,10

Diagnosis of Multiple PHIRs

The presence of 3 concurrent PHIRs is rare. The patient in this report had postzoster cutaneous CLL with an associated granulomatous dermatitis and medium-vessel vasculitis. One other case with these 3 findings was reported by Elgoweini et al.7 Overlooking important diagnoses when multiple findings are present in a biopsy can lead to diagnostic delay and incorrect treatment; we highlighted the importance of careful examination of biopsies in PHIRs to ensure diagnostic accuracy. In cases of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis, assessment of the lymphocytic component should not be overlooked. The presence of a dense lymphocytic infiltrate should raise the possibility of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as CLL, even in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If initial immunostaining discloses a predominantly B-cell infiltrate, additional immuno-stains (eg, CD5, CD23, CD43) and/or genetic testing for monoclonality should be pursued.

Conclusion

Clinicians and dermatopathologists should be aware of the multiplicity of postherpetic isotopic responses and consider immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between a genuine lymphoma such as CLL and pseudolymphoma in PHIRs with a lymphoid infiltrate.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpes virus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf's isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Snow J, el-Azhary R, Gibson L, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis associated with herpes virus: a persistent, painful, postherpetic papular eruption. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:851-853.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Hofler G, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 42 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1000-1010.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Elgoweini M, Blessing K, Jackson R, et al. Coexistent granulomatous vasculitis and leukaemia cutis in a patient with resolving herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:749-751.

- Pujol RM, Matias-Guiu X, Planaguma M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and cutaneous granulomas at sites of herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:652-654.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Kerl H. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia arising at the site of herpes zoster and herpes simplex scars. Cancer. 1995;76:26-31.

- Trojjet S, Hammami H, Zaraa I, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by a granulomatous zosteriform eruption. Skinmed. 2012;10:50-52.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpes virus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf's isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Snow J, el-Azhary R, Gibson L, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis associated with herpes virus: a persistent, painful, postherpetic papular eruption. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:851-853.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Hofler G, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 42 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1000-1010.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Elgoweini M, Blessing K, Jackson R, et al. Coexistent granulomatous vasculitis and leukaemia cutis in a patient with resolving herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:749-751.

- Pujol RM, Matias-Guiu X, Planaguma M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and cutaneous granulomas at sites of herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:652-654.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Kerl H. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia arising at the site of herpes zoster and herpes simplex scars. Cancer. 1995;76:26-31.

- Trojjet S, Hammami H, Zaraa I, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by a granulomatous zosteriform eruption. Skinmed. 2012;10:50-52.

Practice Points

- Multiple diseases may present in prior sites of herpes infection (postherpetic isotopic response).

- Granulomatous dermatitis is the most common postherpetic isotopic response, but other inflammatory, neoplastic, or infectious conditions also occur.

- Multiple conditions may present simultaneously at sites of herpes infection.

- Cutaneous involvement by chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can be easily overlooked in this setting.