User login

Verrucous Carcinoma in a Wounded Military Amputee

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

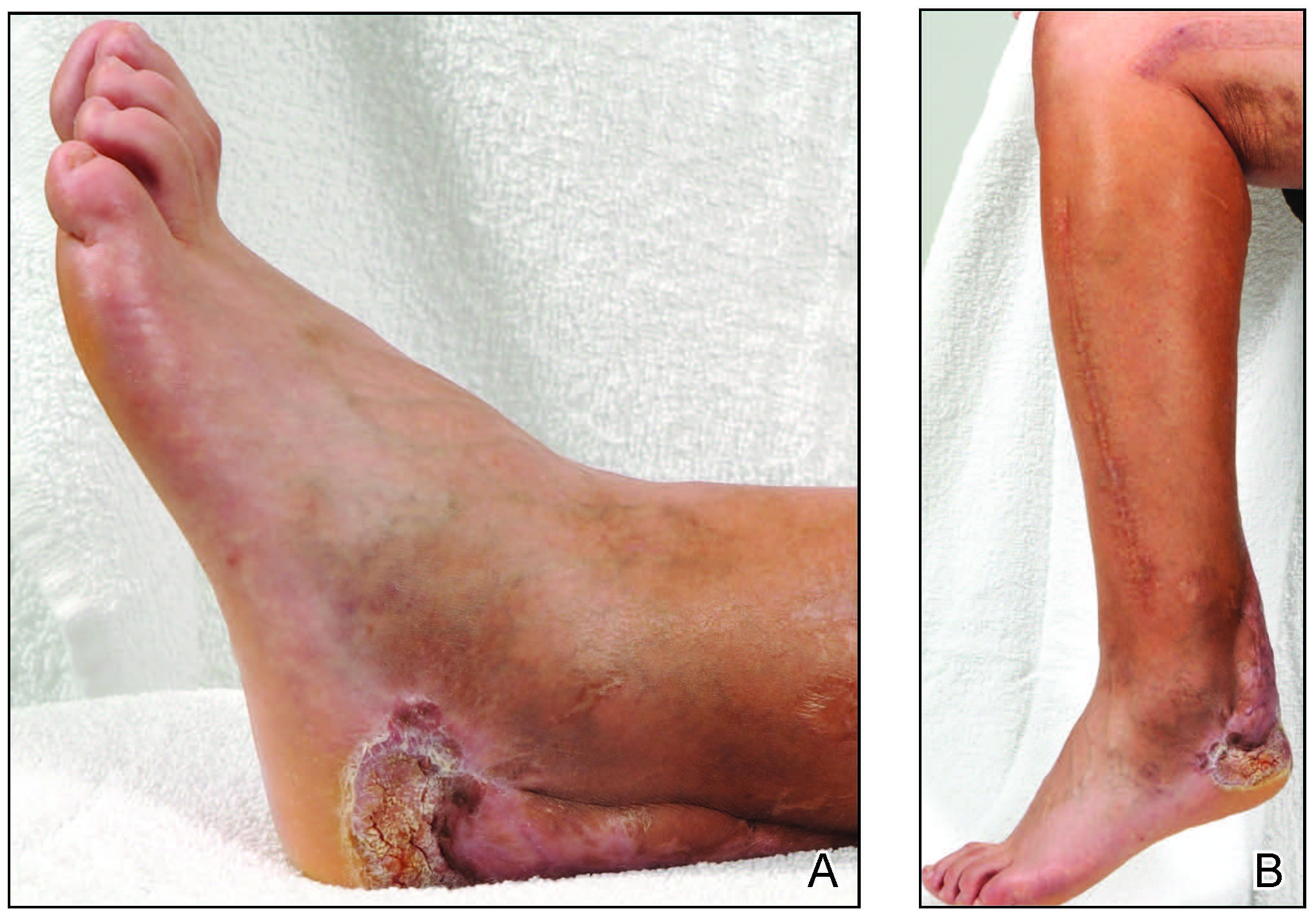

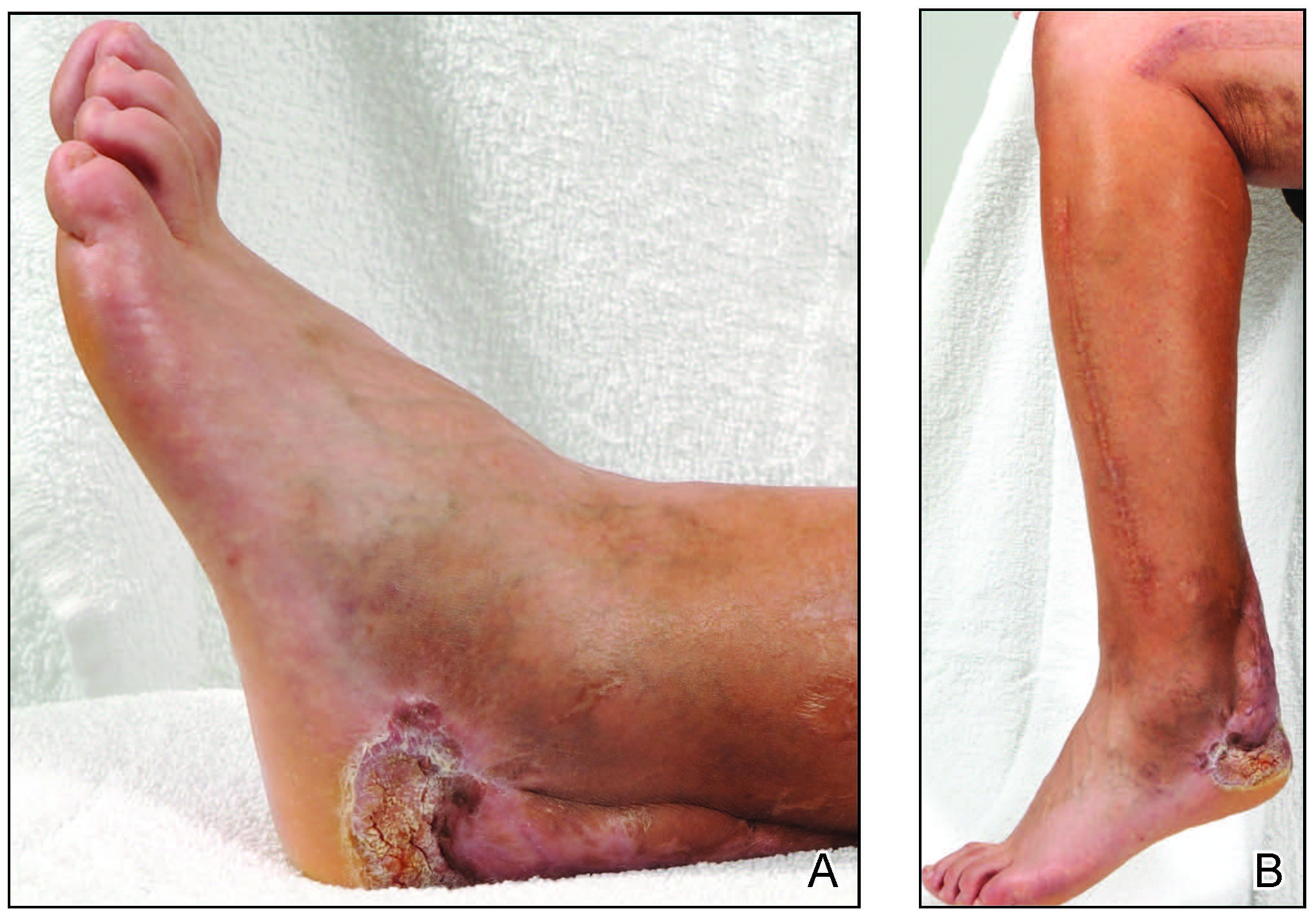

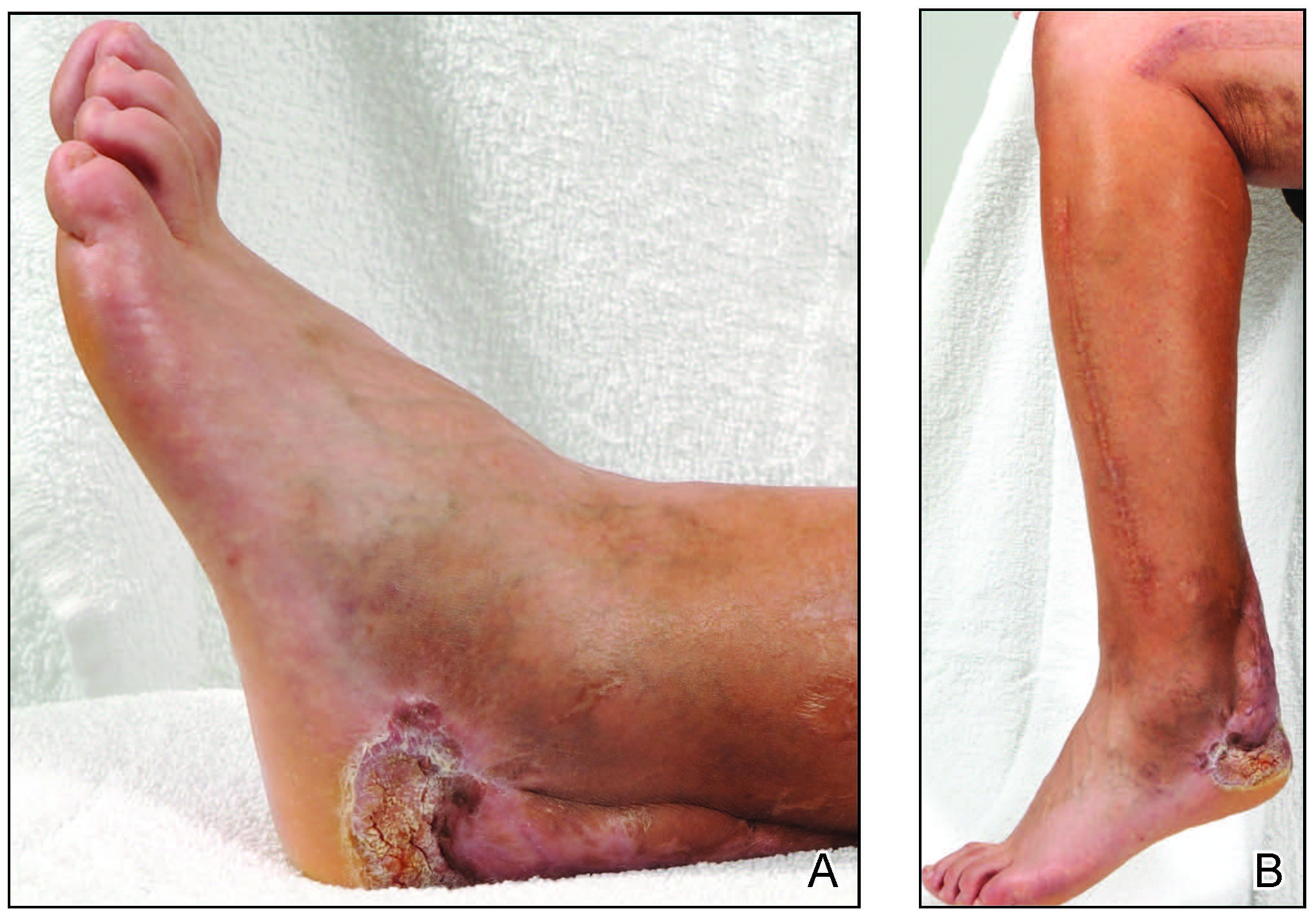

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

Practice Points

- Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma that commonly occurs in sites of inflammation or chronic irritation.

- Histologically, verrucous carcinoma can be mistaken for other entities including verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, often delaying the appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Asymptomatic, Slowly Enlarging Papule on the Nipple

The Diagnosis: Erosive Adenomatosis of the Nipple

Biopsy of the lesion revealed proliferative sections of glandular epithelium demonstrating apocrine differentiation, connecting to the epidermis and traversing throughout the entire dermis of the specimen (Figure). There were papillary projections of dilated ducts with a retained layer of myoepithelial cells surrounding the epithelial layers. Cytologic atypia was not appreciated. The patient was diagnosed with erosive adenomatosis of the nipple (EAN), also known as nipple adenoma. The lesion subsequently was treated and cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). At 8-month follow-up there was no clinical recurrence of the lesion, and the patient was satisfied with the overall cosmetic appearance and conservation of the areola. The patient was followed clinically with annual breast examinations and mammography to monitor future recurrence.

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is an uncommon benign proliferative process of the lactiferous ducts of the nipple. Recognizing EAN is important because it resembles malignant breast diseases such as Paget disease of the nipple and invasive breast carcinoma. Due to these similarities, early cases of EAN have resulted in unnecessary mastectomies before the benignity of the condition was established.1 Accurate diagnosis is important to both the patient and the clinician for treatment planning as well as psychosocial consequences associated with the potential removal of this anatomically and cosmetically sensitive area.

Reviewing the literature on EAN is complicated by the variety of terms used to describe this condition, including but not limited to nipple adenoma, nipple duct adenoma, papillary adenoma of the nipple, and florid papillomatosis of the nipple. In 1955, Jones2 described EAN using the term florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. In 1962, Handley and Thackray1 argued that adenoma of the nipple was a more descriptive term because it more closely described the appearance of a sweat gland adenoma. They reasoned that adenoma of the nipple is a separate process from ductal papilloma due to the adenomatous proliferation into the nipple stroma rather than the lumen of the nipple ducts.1 The term adenoma of the nipple was further supported in 1965 by Taylor and Robertson.3 In 1959, Le Gal et al4 used the term erosive adenomatosis of the nipple to describe the erosive nature of nipple adenoma. The term nipple adenoma was published in the 2012 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast with 4 common histologic subtypes.5,6

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is clinically indistinguishable from Paget disease of the nipple, thus biopsy is essential for accurate diagnosis. In contrast to Paget disease, EAN tends to present in younger patients and progresses more slowly, and symptoms may be exacerbated around menstruation.1 Case reports demonstrate that patients may wait years before seeking medical attention for EAN.1,3,7,8 Presenting symptoms may include inflammation, crusting, nipple skin erosion, itching, and pain. Serous or sanguineous discharge from the lesions also is commonly reported. Palpation may reveal a small, hard, or elastic nodule within or underlying the nipple. In addition to Paget disease, EAN may resemble squamous cell carcinoma of the nipple, eczema, psoriasis, or a skin infection.6 Axillary lymphadenopathy is not present in the absence of a concomitant breast malignancy.8 On biopsy, nipple adenoma represents ductal proliferation of glandular structures within the stroma of the nipple that is well circumscribed but without borders. The erosive appearance of the lesion is produced by extensions of the glandular epithelium on the surface of the nipple.1,6 Specific to EAN is the presence of 2 cell types: an inner columnar epithelium and an outer cuboidal myoepithelium. These 2 cell types are present in normal lactiferous ducts; however, normal ducts are highly organized compared to EAN.9

After confirmation of EAN by nipple biopsy, complete surgical excision has been the gold standard for treatment, followed by reconstructive surgery.6 Handley and Thackray1 advocated for total excision of the nipple and areola with an underlying wedge of breast tissue to facilitate wound closure. More recently, successful alternative forms of treatment have been utilized to minimize disfiguring surgery. Alternative treatments include MMS,8 cryotherapy,10 and nipple splitting enucleation.6 Treatment with MMS has resulted in nipple sparing with the least amount of surface area sacrificed (1.1 cm2).9 Our case and prior case reports demonstrate that the tissue sparing potential of MMS is appropriate for the treatment of EAN, though traditionally it has been reserved for more malignant tumors. Preserving this sensitive area is both cosmetically and psychologically advantageous for the patient and thus should be considered when reviewing treatment options for EAN.

- Handley RS, Thackray AC. Adenoma of nipple. Br J Cancer. 1962;16:187-194.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Taylor HB, Robertson AG. Adenomas of the nipple. Cancer. 1965:18:995-1002.

- Le Gal Y, Gros CM, Bader P. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple [in French]. Ann Anat Pathol (Paris). 1959;4:292-304.

- Eusebi V, Lester S. Tumours of the nipple. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Lyon, France: IARC; 2012.

- Spohn GP, Trotter SC, Tozbician G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Kowal R, Miller CJ, Elenitsas R. Eroded patch on the nipple of a 57-year-old woman. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:933-938.

- Van Mierlo PL, Geelen GM, Neumann HA. Mohs micrographic surgery for an erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:681-683.

- Brankov N, Nino T, Hsiang D, et al. Utilizing Mohs surgery for tissue preservation in erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:684-686.

- Kuflik EG. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:270-271.

The Diagnosis: Erosive Adenomatosis of the Nipple

Biopsy of the lesion revealed proliferative sections of glandular epithelium demonstrating apocrine differentiation, connecting to the epidermis and traversing throughout the entire dermis of the specimen (Figure). There were papillary projections of dilated ducts with a retained layer of myoepithelial cells surrounding the epithelial layers. Cytologic atypia was not appreciated. The patient was diagnosed with erosive adenomatosis of the nipple (EAN), also known as nipple adenoma. The lesion subsequently was treated and cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). At 8-month follow-up there was no clinical recurrence of the lesion, and the patient was satisfied with the overall cosmetic appearance and conservation of the areola. The patient was followed clinically with annual breast examinations and mammography to monitor future recurrence.

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is an uncommon benign proliferative process of the lactiferous ducts of the nipple. Recognizing EAN is important because it resembles malignant breast diseases such as Paget disease of the nipple and invasive breast carcinoma. Due to these similarities, early cases of EAN have resulted in unnecessary mastectomies before the benignity of the condition was established.1 Accurate diagnosis is important to both the patient and the clinician for treatment planning as well as psychosocial consequences associated with the potential removal of this anatomically and cosmetically sensitive area.

Reviewing the literature on EAN is complicated by the variety of terms used to describe this condition, including but not limited to nipple adenoma, nipple duct adenoma, papillary adenoma of the nipple, and florid papillomatosis of the nipple. In 1955, Jones2 described EAN using the term florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. In 1962, Handley and Thackray1 argued that adenoma of the nipple was a more descriptive term because it more closely described the appearance of a sweat gland adenoma. They reasoned that adenoma of the nipple is a separate process from ductal papilloma due to the adenomatous proliferation into the nipple stroma rather than the lumen of the nipple ducts.1 The term adenoma of the nipple was further supported in 1965 by Taylor and Robertson.3 In 1959, Le Gal et al4 used the term erosive adenomatosis of the nipple to describe the erosive nature of nipple adenoma. The term nipple adenoma was published in the 2012 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast with 4 common histologic subtypes.5,6

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is clinically indistinguishable from Paget disease of the nipple, thus biopsy is essential for accurate diagnosis. In contrast to Paget disease, EAN tends to present in younger patients and progresses more slowly, and symptoms may be exacerbated around menstruation.1 Case reports demonstrate that patients may wait years before seeking medical attention for EAN.1,3,7,8 Presenting symptoms may include inflammation, crusting, nipple skin erosion, itching, and pain. Serous or sanguineous discharge from the lesions also is commonly reported. Palpation may reveal a small, hard, or elastic nodule within or underlying the nipple. In addition to Paget disease, EAN may resemble squamous cell carcinoma of the nipple, eczema, psoriasis, or a skin infection.6 Axillary lymphadenopathy is not present in the absence of a concomitant breast malignancy.8 On biopsy, nipple adenoma represents ductal proliferation of glandular structures within the stroma of the nipple that is well circumscribed but without borders. The erosive appearance of the lesion is produced by extensions of the glandular epithelium on the surface of the nipple.1,6 Specific to EAN is the presence of 2 cell types: an inner columnar epithelium and an outer cuboidal myoepithelium. These 2 cell types are present in normal lactiferous ducts; however, normal ducts are highly organized compared to EAN.9

After confirmation of EAN by nipple biopsy, complete surgical excision has been the gold standard for treatment, followed by reconstructive surgery.6 Handley and Thackray1 advocated for total excision of the nipple and areola with an underlying wedge of breast tissue to facilitate wound closure. More recently, successful alternative forms of treatment have been utilized to minimize disfiguring surgery. Alternative treatments include MMS,8 cryotherapy,10 and nipple splitting enucleation.6 Treatment with MMS has resulted in nipple sparing with the least amount of surface area sacrificed (1.1 cm2).9 Our case and prior case reports demonstrate that the tissue sparing potential of MMS is appropriate for the treatment of EAN, though traditionally it has been reserved for more malignant tumors. Preserving this sensitive area is both cosmetically and psychologically advantageous for the patient and thus should be considered when reviewing treatment options for EAN.

The Diagnosis: Erosive Adenomatosis of the Nipple

Biopsy of the lesion revealed proliferative sections of glandular epithelium demonstrating apocrine differentiation, connecting to the epidermis and traversing throughout the entire dermis of the specimen (Figure). There were papillary projections of dilated ducts with a retained layer of myoepithelial cells surrounding the epithelial layers. Cytologic atypia was not appreciated. The patient was diagnosed with erosive adenomatosis of the nipple (EAN), also known as nipple adenoma. The lesion subsequently was treated and cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). At 8-month follow-up there was no clinical recurrence of the lesion, and the patient was satisfied with the overall cosmetic appearance and conservation of the areola. The patient was followed clinically with annual breast examinations and mammography to monitor future recurrence.

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is an uncommon benign proliferative process of the lactiferous ducts of the nipple. Recognizing EAN is important because it resembles malignant breast diseases such as Paget disease of the nipple and invasive breast carcinoma. Due to these similarities, early cases of EAN have resulted in unnecessary mastectomies before the benignity of the condition was established.1 Accurate diagnosis is important to both the patient and the clinician for treatment planning as well as psychosocial consequences associated with the potential removal of this anatomically and cosmetically sensitive area.

Reviewing the literature on EAN is complicated by the variety of terms used to describe this condition, including but not limited to nipple adenoma, nipple duct adenoma, papillary adenoma of the nipple, and florid papillomatosis of the nipple. In 1955, Jones2 described EAN using the term florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. In 1962, Handley and Thackray1 argued that adenoma of the nipple was a more descriptive term because it more closely described the appearance of a sweat gland adenoma. They reasoned that adenoma of the nipple is a separate process from ductal papilloma due to the adenomatous proliferation into the nipple stroma rather than the lumen of the nipple ducts.1 The term adenoma of the nipple was further supported in 1965 by Taylor and Robertson.3 In 1959, Le Gal et al4 used the term erosive adenomatosis of the nipple to describe the erosive nature of nipple adenoma. The term nipple adenoma was published in the 2012 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast with 4 common histologic subtypes.5,6

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is clinically indistinguishable from Paget disease of the nipple, thus biopsy is essential for accurate diagnosis. In contrast to Paget disease, EAN tends to present in younger patients and progresses more slowly, and symptoms may be exacerbated around menstruation.1 Case reports demonstrate that patients may wait years before seeking medical attention for EAN.1,3,7,8 Presenting symptoms may include inflammation, crusting, nipple skin erosion, itching, and pain. Serous or sanguineous discharge from the lesions also is commonly reported. Palpation may reveal a small, hard, or elastic nodule within or underlying the nipple. In addition to Paget disease, EAN may resemble squamous cell carcinoma of the nipple, eczema, psoriasis, or a skin infection.6 Axillary lymphadenopathy is not present in the absence of a concomitant breast malignancy.8 On biopsy, nipple adenoma represents ductal proliferation of glandular structures within the stroma of the nipple that is well circumscribed but without borders. The erosive appearance of the lesion is produced by extensions of the glandular epithelium on the surface of the nipple.1,6 Specific to EAN is the presence of 2 cell types: an inner columnar epithelium and an outer cuboidal myoepithelium. These 2 cell types are present in normal lactiferous ducts; however, normal ducts are highly organized compared to EAN.9

After confirmation of EAN by nipple biopsy, complete surgical excision has been the gold standard for treatment, followed by reconstructive surgery.6 Handley and Thackray1 advocated for total excision of the nipple and areola with an underlying wedge of breast tissue to facilitate wound closure. More recently, successful alternative forms of treatment have been utilized to minimize disfiguring surgery. Alternative treatments include MMS,8 cryotherapy,10 and nipple splitting enucleation.6 Treatment with MMS has resulted in nipple sparing with the least amount of surface area sacrificed (1.1 cm2).9 Our case and prior case reports demonstrate that the tissue sparing potential of MMS is appropriate for the treatment of EAN, though traditionally it has been reserved for more malignant tumors. Preserving this sensitive area is both cosmetically and psychologically advantageous for the patient and thus should be considered when reviewing treatment options for EAN.

- Handley RS, Thackray AC. Adenoma of nipple. Br J Cancer. 1962;16:187-194.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Taylor HB, Robertson AG. Adenomas of the nipple. Cancer. 1965:18:995-1002.

- Le Gal Y, Gros CM, Bader P. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple [in French]. Ann Anat Pathol (Paris). 1959;4:292-304.

- Eusebi V, Lester S. Tumours of the nipple. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Lyon, France: IARC; 2012.

- Spohn GP, Trotter SC, Tozbician G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Kowal R, Miller CJ, Elenitsas R. Eroded patch on the nipple of a 57-year-old woman. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:933-938.

- Van Mierlo PL, Geelen GM, Neumann HA. Mohs micrographic surgery for an erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:681-683.

- Brankov N, Nino T, Hsiang D, et al. Utilizing Mohs surgery for tissue preservation in erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:684-686.

- Kuflik EG. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:270-271.

- Handley RS, Thackray AC. Adenoma of nipple. Br J Cancer. 1962;16:187-194.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Taylor HB, Robertson AG. Adenomas of the nipple. Cancer. 1965:18:995-1002.

- Le Gal Y, Gros CM, Bader P. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple [in French]. Ann Anat Pathol (Paris). 1959;4:292-304.

- Eusebi V, Lester S. Tumours of the nipple. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Lyon, France: IARC; 2012.

- Spohn GP, Trotter SC, Tozbician G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Kowal R, Miller CJ, Elenitsas R. Eroded patch on the nipple of a 57-year-old woman. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:933-938.

- Van Mierlo PL, Geelen GM, Neumann HA. Mohs micrographic surgery for an erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:681-683.

- Brankov N, Nino T, Hsiang D, et al. Utilizing Mohs surgery for tissue preservation in erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:684-686.

- Kuflik EG. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:270-271.

A 61-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic, slowly enlarging, 9-mm, firm, red papule on the left nipple of 2 years' duration. She had no notable medical history, including a BI-RADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) mammogram score of 2 that was suggestive of benign findings 2 years prior. A repeat mammogram ordered by radiology and completed before presenting to dermatology had a BI-RADS score of 4, noting a concerning feature in the area of the lesion and prompting a biopsy.