User login

Verrucous Carcinoma in a Wounded Military Amputee

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

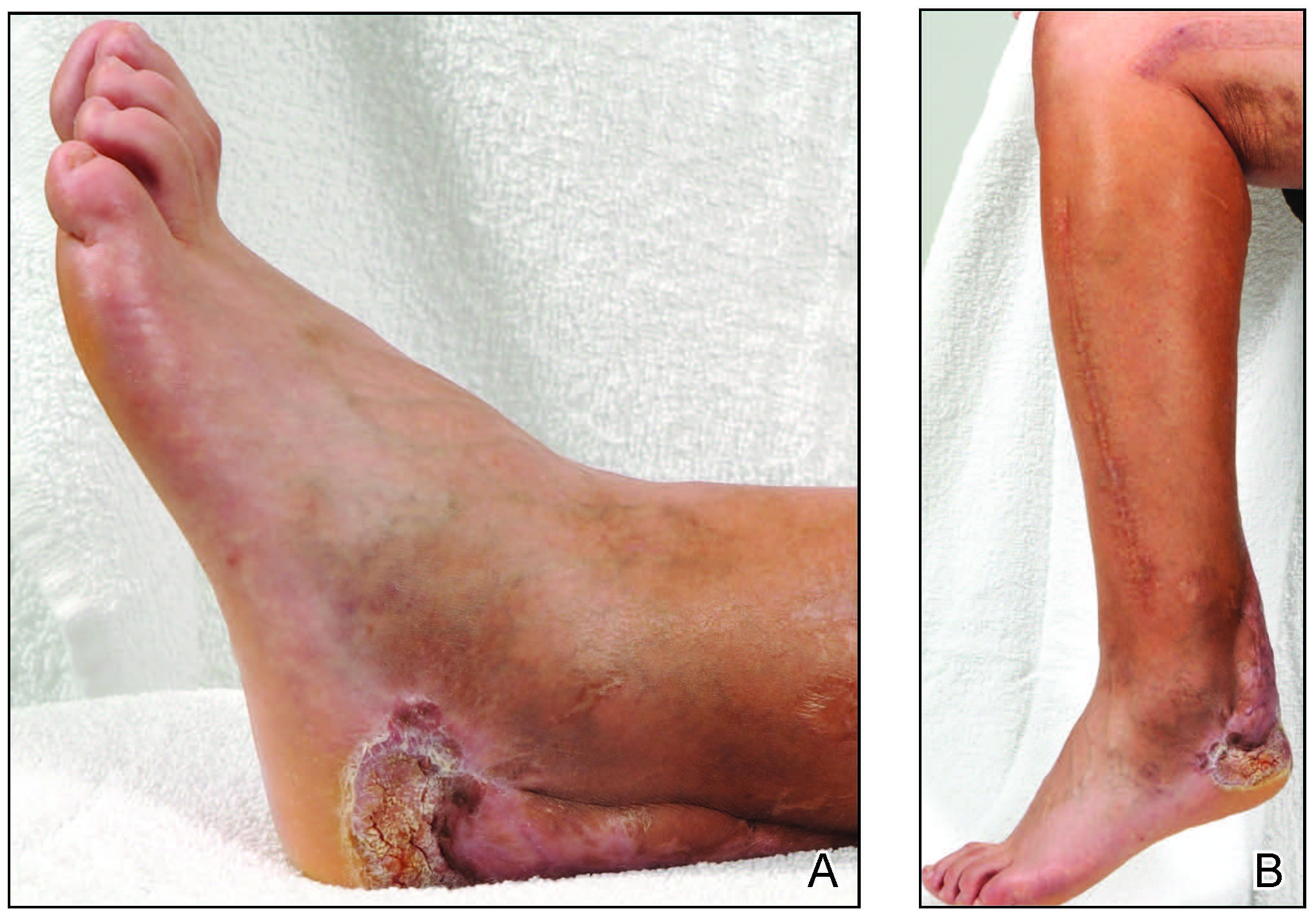

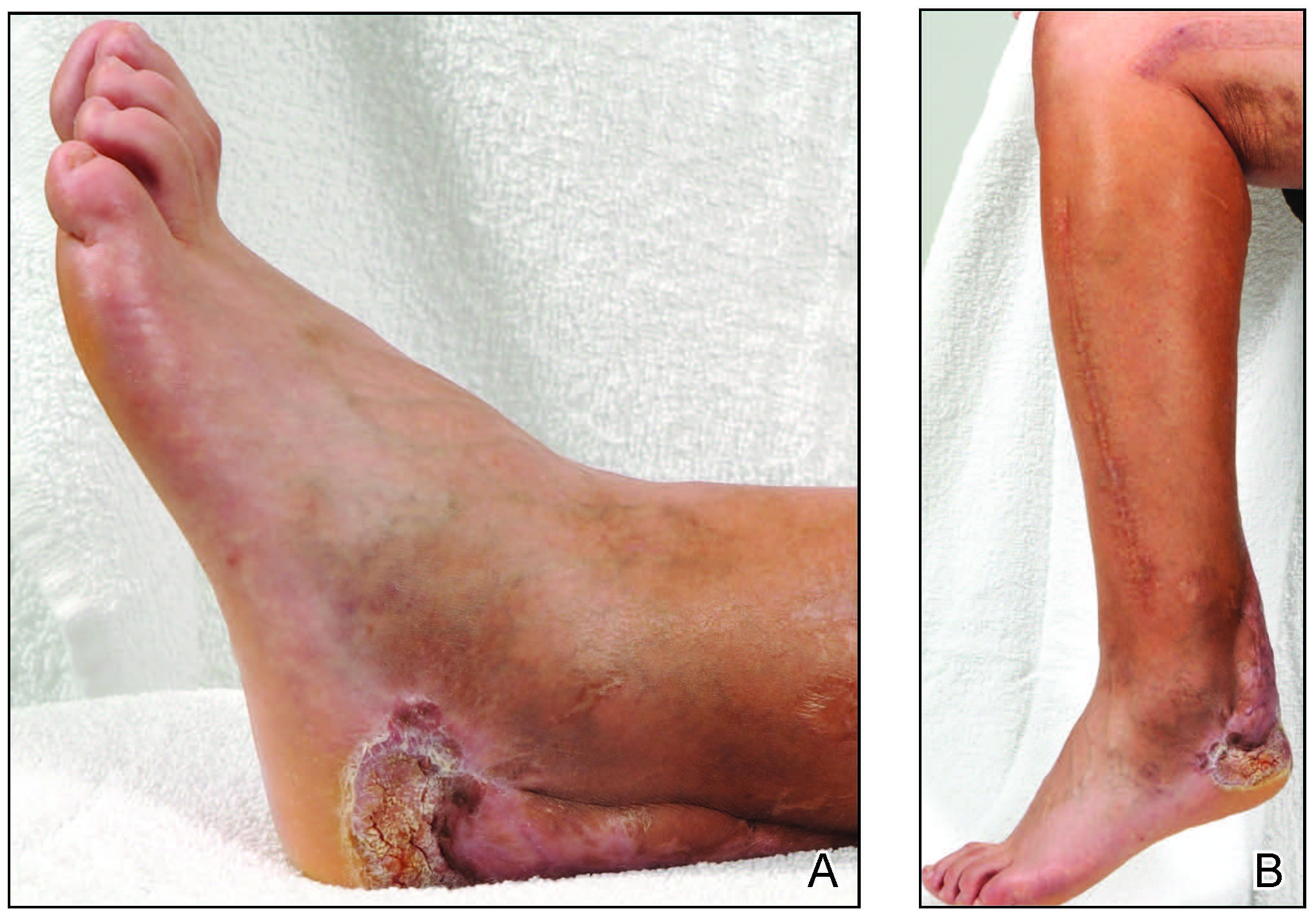

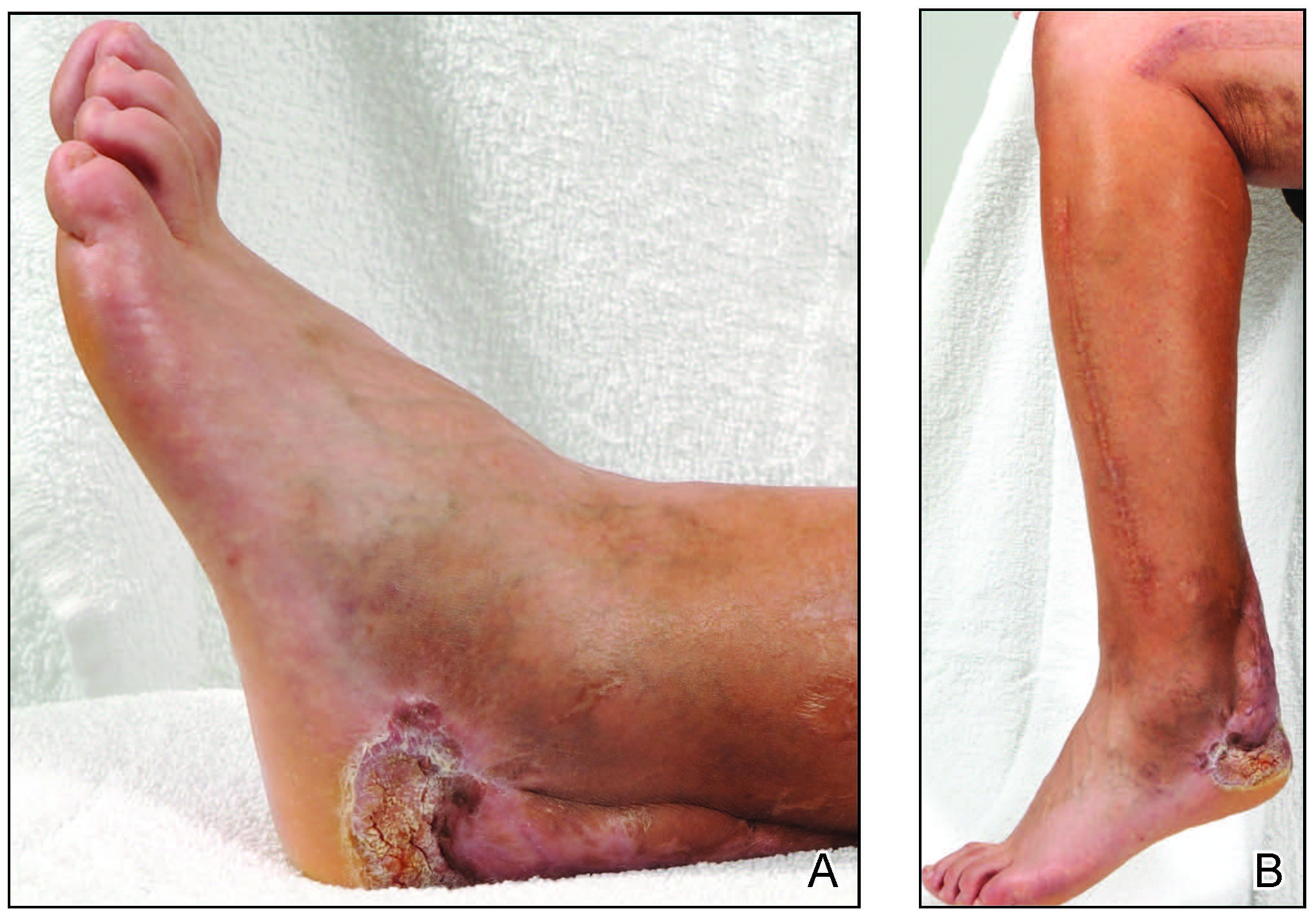

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

Practice Points

- Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma that commonly occurs in sites of inflammation or chronic irritation.

- Histologically, verrucous carcinoma can be mistaken for other entities including verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, often delaying the appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Nodules, tumors, and hyperpigmented patches

A 36-year-old African-American man presented to our clinic for evaluation of a chronic “rash” on his trunk, arms, and legs that had been present for 3 years. Empiric therapy for tinea corporis, nummular eczema, and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis had failed to improve his lesions.

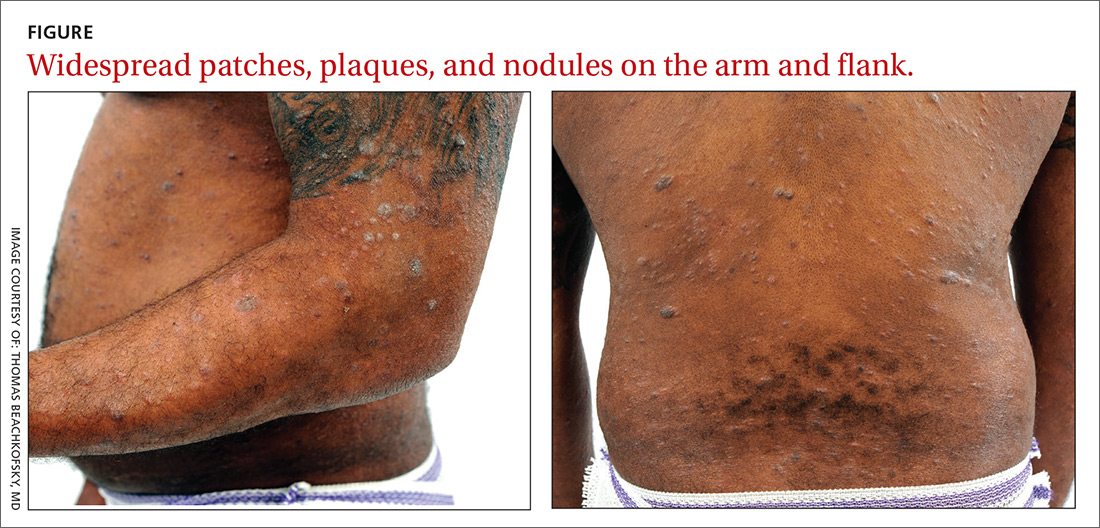

Physical examination revealed a widespread skin eruption consisting of well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, scaly patches and plaques distributed throughout the patient’s trunk and extremities. Initial biopsies of the skin lesions (performed at an outside institution prior to current presentation) were nondiagnostic.

Over the next several months, the patient developed numerous cutaneous nodules and tumors within the background of his persistent patches and plaques (FIGURE). These nodules and tumors intermittently disappeared and recurred, seemingly independent of therapies including psoralen and ultraviolet A phototherapy (PUVA), interferon, and methotrexate.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: CD30+ transformed mycosis fungoides

Repeat biopsies ultimately confirmed a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF), a primary cutaneous non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin.

Lymphomas occurring in the skin without evidence of disease in other areas of the body at the time of diagnosis are referred to as primary cutaneous lymphomas. They are broadly divided by their cell of origin into cutaneous T-cell and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Differentiating primary cutaneous lymphoma from systemic lymphomas with secondary skin involvement is an important distinction, as primary cutaneous lymphomas have different clinical courses and prognoses and require different treatments.1

MF is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), yet it remains an uncommon diagnosis as cutaneous lymphomas comprise only 3.9% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2 The CD30+ transformed variant identified in this patient is a rare subtype of MF that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3 Other types of CTCL include primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, all of which can resemble MF clinically and are diagnosed by histopathology.

A nonspecific presentation

Patients with MF typically present with a complaint of chronic, slowly progressive skin lesions of various sizes and morphologies including scaly patches, plaques, and tumors, often in skin distributions that are not directly exposed to the sun (often referred to as a “bathing suit” distribution).4 Pruritus typically accompanies these skin lesions, and alopecia and poikiloderma are common findings. Patients with more advanced cases may present with generalized erythroderma. This finding should raise concern for progression to Sézary syndrome, a more aggressive type of CTCL that manifests with leukemic involvement of malignant T-cells matching the T-cell clones found in the skin.2

Alopecia is a common manifestation of MF that can be clinically indistinguishable from alopecia areata.5 While isolated alopecia is unlikely to be a consequence of MF, alopecia in the setting of widespread patches and plaques should raise suspicion for a diagnosis of MF.

Continue to: Diagnostic dilemma

Diagnostic dilemma: Condition mimics benign disorders

This case illustrates the diagnostic dilemma posed by MF due to its propensity to mimic more benign skin disorders, both clinically and histologically.2 One literature review of MF cases in which the diagnosis was not suspected clinically but was eventually confirmed histopathologically found that 25 unique dermatoses can be mimicked clinically by MF.6 The more common conditions that MF can be mistaken for are discussed below. In light of the diagnostic challenge posed by this multitude of morphologic presentations, referral to Dermatology for histopathologic evaluation is a reasonable next step when empiric treatment fails to improve symptoms of these common skin disorders.

Chronic atopic dermatitis (eczema) is characterized by dry skin and severe pruritis, usually associated with lichenified plaques and a history of atopic disease. The pruritic, scaly plaques typical of MF may be misdiagnosed as eczema; however, a distribution involving the “bathing suit” area is more suggestive of MF. Patients with atopic dermatitis are more likely to display a flexural distribution.2

Tinea corporis typically presents as annular, erythematous, pruritic, scaly patches or plaques that are similar to the scaling lesions of MF. Tinea corporis can be distinguished from MF via potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from an active lesion, which should demonstrate the segmented hyphae characteristic of this infection. If lesions of this type fail to respond to topical antifungal therapy, a skin biopsy may be warranted for further evaluation.

Nummular eczema, like tinea corporis, presents with round, coin-shaped patches that are highly pruritic and can be difficult to distinguish from the pruritic patches of MF. Unlike MF, however, nummular eczema typically is observed in patients with diffusely dry skin7; the lack of this finding should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, including MF.

Psoriasis classically presents with symmetrically distributed, well-demarcated plaques with prominent scaling that are usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with pruritis. Psoriatic plaques may be difficult to distinguish clinically from the plaques of MF, but their distribution may offer clues; psoriasis typically follows an extensor surface distribution, whereas MF is more commonly identified in a “bathing suit” or generalized distribution.4

Continue to: Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Staging of MF is the primary determinant of treatment and involves evaluation of skin, lymph node, viscera, and blood involvement. Early-stage MF has a favorable prognosis and can be effectively managed with skin-directed treatments. These include topical corticosteroids, topical nitrogen mustard agents, topical retinoids, and phototherapy (PUVA).8 Total skin electron beam therapy has been proven effective in the treatment of refractory and extensive MF, and local radiation therapy also is an effective treatment for isolated cutaneous tumors. Prolonged complete remissions of early-stage MF have been achieved using skin-directed treatments.8

In contrast, advanced MF often is treatment refractory and carries a poor prognosis. Systemic treatments such as interferon therapy, oral retinoids, extracorporeal photopheresis, and chemotherapy are added in patients with advanced disease after skin-directed therapy fails to adequately control tumor burden.

Our patient initially was treated with PUVA as well as 6 million U of interferon alfa-2B 3 times weekly, which he eventually elected to discontinue after 8 months because he wanted to father a child. His disease became more widespread after discontinuing these treatments despite interim therapy with clobetasol ointment .05%. His larger nodules and tumors were intermittently treated with local radiation with good response. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly was initiated following his decline after discontinuing PUVA and interferon treatment. Treatment with methotrexate resulted in an overall decrease in his tumor burden and several months of clinical stability.

Approximately 6 months after initiating methotrexate, his condition notably worsened. He developed generalized erythroderma, systemic symptoms including fever, chills, and unintentional 9.07-kg weight loss, in addition to new findings of palmoplantar keratoderma and nail dystrophy. In light of this systemic progression and concern for developing Sézary syndrome, extracorporeal photopheresis, bexarotene (an oral retinoid) 75 mg twice daily, and interferon alfa-2B 5 million U 3 times weekly were initiated. His condition continued to decline despite these therapies, culminating in a hospital admission for sepsis.

The patient recovered, and his regimen was changed to PUVA 3 times weekly in addition to treatment with intravenous brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD30 receptors. Unfortunately, his condition continued to decline on this treatment regimen, which was subsequently abandoned in favor of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1980 mg/250 mL normal saline. The patient was improving clinically with each cycle of gemcitabine and the plan was to transition him to extracorporeal photopheresis and bexarotene for maintenance therapy; however, the patient succumbed to his disease and passed away at the age of 37.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Banta, MD, PSC 103, Box 3613, APO, AE 09603 jonathan.c.banta.mil@mail.mil

1. Whittaker S, Knobler R, Ortiz P, et al. Major achievements of the EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force (CLTF). EJC Suppl. 2012;10:46-50.

2. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-205.e16.

3. Kadin ME, Hughey LC, Wood GS. Large-cell transformation of mycosis fungoides-differential diagnosis with implications for clinical management: a consensus statement of the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:374-376.

4. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al; International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

5. Bi MY, Curry JL, Christiano AM, et al. The spectrum of hair loss in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:53-63.

6. Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

7. Jiamton S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Kulthanan K. Clinical features and aggravating factors in nummular eczema in Thais. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31:36-42.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-223.e17.

A 36-year-old African-American man presented to our clinic for evaluation of a chronic “rash” on his trunk, arms, and legs that had been present for 3 years. Empiric therapy for tinea corporis, nummular eczema, and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis had failed to improve his lesions.

Physical examination revealed a widespread skin eruption consisting of well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, scaly patches and plaques distributed throughout the patient’s trunk and extremities. Initial biopsies of the skin lesions (performed at an outside institution prior to current presentation) were nondiagnostic.

Over the next several months, the patient developed numerous cutaneous nodules and tumors within the background of his persistent patches and plaques (FIGURE). These nodules and tumors intermittently disappeared and recurred, seemingly independent of therapies including psoralen and ultraviolet A phototherapy (PUVA), interferon, and methotrexate.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: CD30+ transformed mycosis fungoides

Repeat biopsies ultimately confirmed a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF), a primary cutaneous non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin.

Lymphomas occurring in the skin without evidence of disease in other areas of the body at the time of diagnosis are referred to as primary cutaneous lymphomas. They are broadly divided by their cell of origin into cutaneous T-cell and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Differentiating primary cutaneous lymphoma from systemic lymphomas with secondary skin involvement is an important distinction, as primary cutaneous lymphomas have different clinical courses and prognoses and require different treatments.1

MF is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), yet it remains an uncommon diagnosis as cutaneous lymphomas comprise only 3.9% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2 The CD30+ transformed variant identified in this patient is a rare subtype of MF that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3 Other types of CTCL include primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, all of which can resemble MF clinically and are diagnosed by histopathology.

A nonspecific presentation

Patients with MF typically present with a complaint of chronic, slowly progressive skin lesions of various sizes and morphologies including scaly patches, plaques, and tumors, often in skin distributions that are not directly exposed to the sun (often referred to as a “bathing suit” distribution).4 Pruritus typically accompanies these skin lesions, and alopecia and poikiloderma are common findings. Patients with more advanced cases may present with generalized erythroderma. This finding should raise concern for progression to Sézary syndrome, a more aggressive type of CTCL that manifests with leukemic involvement of malignant T-cells matching the T-cell clones found in the skin.2

Alopecia is a common manifestation of MF that can be clinically indistinguishable from alopecia areata.5 While isolated alopecia is unlikely to be a consequence of MF, alopecia in the setting of widespread patches and plaques should raise suspicion for a diagnosis of MF.

Continue to: Diagnostic dilemma

Diagnostic dilemma: Condition mimics benign disorders

This case illustrates the diagnostic dilemma posed by MF due to its propensity to mimic more benign skin disorders, both clinically and histologically.2 One literature review of MF cases in which the diagnosis was not suspected clinically but was eventually confirmed histopathologically found that 25 unique dermatoses can be mimicked clinically by MF.6 The more common conditions that MF can be mistaken for are discussed below. In light of the diagnostic challenge posed by this multitude of morphologic presentations, referral to Dermatology for histopathologic evaluation is a reasonable next step when empiric treatment fails to improve symptoms of these common skin disorders.

Chronic atopic dermatitis (eczema) is characterized by dry skin and severe pruritis, usually associated with lichenified plaques and a history of atopic disease. The pruritic, scaly plaques typical of MF may be misdiagnosed as eczema; however, a distribution involving the “bathing suit” area is more suggestive of MF. Patients with atopic dermatitis are more likely to display a flexural distribution.2

Tinea corporis typically presents as annular, erythematous, pruritic, scaly patches or plaques that are similar to the scaling lesions of MF. Tinea corporis can be distinguished from MF via potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from an active lesion, which should demonstrate the segmented hyphae characteristic of this infection. If lesions of this type fail to respond to topical antifungal therapy, a skin biopsy may be warranted for further evaluation.

Nummular eczema, like tinea corporis, presents with round, coin-shaped patches that are highly pruritic and can be difficult to distinguish from the pruritic patches of MF. Unlike MF, however, nummular eczema typically is observed in patients with diffusely dry skin7; the lack of this finding should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, including MF.

Psoriasis classically presents with symmetrically distributed, well-demarcated plaques with prominent scaling that are usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with pruritis. Psoriatic plaques may be difficult to distinguish clinically from the plaques of MF, but their distribution may offer clues; psoriasis typically follows an extensor surface distribution, whereas MF is more commonly identified in a “bathing suit” or generalized distribution.4

Continue to: Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Staging of MF is the primary determinant of treatment and involves evaluation of skin, lymph node, viscera, and blood involvement. Early-stage MF has a favorable prognosis and can be effectively managed with skin-directed treatments. These include topical corticosteroids, topical nitrogen mustard agents, topical retinoids, and phototherapy (PUVA).8 Total skin electron beam therapy has been proven effective in the treatment of refractory and extensive MF, and local radiation therapy also is an effective treatment for isolated cutaneous tumors. Prolonged complete remissions of early-stage MF have been achieved using skin-directed treatments.8

In contrast, advanced MF often is treatment refractory and carries a poor prognosis. Systemic treatments such as interferon therapy, oral retinoids, extracorporeal photopheresis, and chemotherapy are added in patients with advanced disease after skin-directed therapy fails to adequately control tumor burden.

Our patient initially was treated with PUVA as well as 6 million U of interferon alfa-2B 3 times weekly, which he eventually elected to discontinue after 8 months because he wanted to father a child. His disease became more widespread after discontinuing these treatments despite interim therapy with clobetasol ointment .05%. His larger nodules and tumors were intermittently treated with local radiation with good response. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly was initiated following his decline after discontinuing PUVA and interferon treatment. Treatment with methotrexate resulted in an overall decrease in his tumor burden and several months of clinical stability.

Approximately 6 months after initiating methotrexate, his condition notably worsened. He developed generalized erythroderma, systemic symptoms including fever, chills, and unintentional 9.07-kg weight loss, in addition to new findings of palmoplantar keratoderma and nail dystrophy. In light of this systemic progression and concern for developing Sézary syndrome, extracorporeal photopheresis, bexarotene (an oral retinoid) 75 mg twice daily, and interferon alfa-2B 5 million U 3 times weekly were initiated. His condition continued to decline despite these therapies, culminating in a hospital admission for sepsis.

The patient recovered, and his regimen was changed to PUVA 3 times weekly in addition to treatment with intravenous brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD30 receptors. Unfortunately, his condition continued to decline on this treatment regimen, which was subsequently abandoned in favor of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1980 mg/250 mL normal saline. The patient was improving clinically with each cycle of gemcitabine and the plan was to transition him to extracorporeal photopheresis and bexarotene for maintenance therapy; however, the patient succumbed to his disease and passed away at the age of 37.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Banta, MD, PSC 103, Box 3613, APO, AE 09603 jonathan.c.banta.mil@mail.mil

A 36-year-old African-American man presented to our clinic for evaluation of a chronic “rash” on his trunk, arms, and legs that had been present for 3 years. Empiric therapy for tinea corporis, nummular eczema, and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis had failed to improve his lesions.

Physical examination revealed a widespread skin eruption consisting of well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, scaly patches and plaques distributed throughout the patient’s trunk and extremities. Initial biopsies of the skin lesions (performed at an outside institution prior to current presentation) were nondiagnostic.

Over the next several months, the patient developed numerous cutaneous nodules and tumors within the background of his persistent patches and plaques (FIGURE). These nodules and tumors intermittently disappeared and recurred, seemingly independent of therapies including psoralen and ultraviolet A phototherapy (PUVA), interferon, and methotrexate.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: CD30+ transformed mycosis fungoides

Repeat biopsies ultimately confirmed a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF), a primary cutaneous non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin.

Lymphomas occurring in the skin without evidence of disease in other areas of the body at the time of diagnosis are referred to as primary cutaneous lymphomas. They are broadly divided by their cell of origin into cutaneous T-cell and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Differentiating primary cutaneous lymphoma from systemic lymphomas with secondary skin involvement is an important distinction, as primary cutaneous lymphomas have different clinical courses and prognoses and require different treatments.1

MF is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), yet it remains an uncommon diagnosis as cutaneous lymphomas comprise only 3.9% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2 The CD30+ transformed variant identified in this patient is a rare subtype of MF that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3 Other types of CTCL include primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, all of which can resemble MF clinically and are diagnosed by histopathology.

A nonspecific presentation

Patients with MF typically present with a complaint of chronic, slowly progressive skin lesions of various sizes and morphologies including scaly patches, plaques, and tumors, often in skin distributions that are not directly exposed to the sun (often referred to as a “bathing suit” distribution).4 Pruritus typically accompanies these skin lesions, and alopecia and poikiloderma are common findings. Patients with more advanced cases may present with generalized erythroderma. This finding should raise concern for progression to Sézary syndrome, a more aggressive type of CTCL that manifests with leukemic involvement of malignant T-cells matching the T-cell clones found in the skin.2

Alopecia is a common manifestation of MF that can be clinically indistinguishable from alopecia areata.5 While isolated alopecia is unlikely to be a consequence of MF, alopecia in the setting of widespread patches and plaques should raise suspicion for a diagnosis of MF.

Continue to: Diagnostic dilemma

Diagnostic dilemma: Condition mimics benign disorders

This case illustrates the diagnostic dilemma posed by MF due to its propensity to mimic more benign skin disorders, both clinically and histologically.2 One literature review of MF cases in which the diagnosis was not suspected clinically but was eventually confirmed histopathologically found that 25 unique dermatoses can be mimicked clinically by MF.6 The more common conditions that MF can be mistaken for are discussed below. In light of the diagnostic challenge posed by this multitude of morphologic presentations, referral to Dermatology for histopathologic evaluation is a reasonable next step when empiric treatment fails to improve symptoms of these common skin disorders.

Chronic atopic dermatitis (eczema) is characterized by dry skin and severe pruritis, usually associated with lichenified plaques and a history of atopic disease. The pruritic, scaly plaques typical of MF may be misdiagnosed as eczema; however, a distribution involving the “bathing suit” area is more suggestive of MF. Patients with atopic dermatitis are more likely to display a flexural distribution.2

Tinea corporis typically presents as annular, erythematous, pruritic, scaly patches or plaques that are similar to the scaling lesions of MF. Tinea corporis can be distinguished from MF via potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from an active lesion, which should demonstrate the segmented hyphae characteristic of this infection. If lesions of this type fail to respond to topical antifungal therapy, a skin biopsy may be warranted for further evaluation.

Nummular eczema, like tinea corporis, presents with round, coin-shaped patches that are highly pruritic and can be difficult to distinguish from the pruritic patches of MF. Unlike MF, however, nummular eczema typically is observed in patients with diffusely dry skin7; the lack of this finding should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, including MF.

Psoriasis classically presents with symmetrically distributed, well-demarcated plaques with prominent scaling that are usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with pruritis. Psoriatic plaques may be difficult to distinguish clinically from the plaques of MF, but their distribution may offer clues; psoriasis typically follows an extensor surface distribution, whereas MF is more commonly identified in a “bathing suit” or generalized distribution.4

Continue to: Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Staging of MF is the primary determinant of treatment and involves evaluation of skin, lymph node, viscera, and blood involvement. Early-stage MF has a favorable prognosis and can be effectively managed with skin-directed treatments. These include topical corticosteroids, topical nitrogen mustard agents, topical retinoids, and phototherapy (PUVA).8 Total skin electron beam therapy has been proven effective in the treatment of refractory and extensive MF, and local radiation therapy also is an effective treatment for isolated cutaneous tumors. Prolonged complete remissions of early-stage MF have been achieved using skin-directed treatments.8

In contrast, advanced MF often is treatment refractory and carries a poor prognosis. Systemic treatments such as interferon therapy, oral retinoids, extracorporeal photopheresis, and chemotherapy are added in patients with advanced disease after skin-directed therapy fails to adequately control tumor burden.

Our patient initially was treated with PUVA as well as 6 million U of interferon alfa-2B 3 times weekly, which he eventually elected to discontinue after 8 months because he wanted to father a child. His disease became more widespread after discontinuing these treatments despite interim therapy with clobetasol ointment .05%. His larger nodules and tumors were intermittently treated with local radiation with good response. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly was initiated following his decline after discontinuing PUVA and interferon treatment. Treatment with methotrexate resulted in an overall decrease in his tumor burden and several months of clinical stability.

Approximately 6 months after initiating methotrexate, his condition notably worsened. He developed generalized erythroderma, systemic symptoms including fever, chills, and unintentional 9.07-kg weight loss, in addition to new findings of palmoplantar keratoderma and nail dystrophy. In light of this systemic progression and concern for developing Sézary syndrome, extracorporeal photopheresis, bexarotene (an oral retinoid) 75 mg twice daily, and interferon alfa-2B 5 million U 3 times weekly were initiated. His condition continued to decline despite these therapies, culminating in a hospital admission for sepsis.

The patient recovered, and his regimen was changed to PUVA 3 times weekly in addition to treatment with intravenous brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD30 receptors. Unfortunately, his condition continued to decline on this treatment regimen, which was subsequently abandoned in favor of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1980 mg/250 mL normal saline. The patient was improving clinically with each cycle of gemcitabine and the plan was to transition him to extracorporeal photopheresis and bexarotene for maintenance therapy; however, the patient succumbed to his disease and passed away at the age of 37.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Banta, MD, PSC 103, Box 3613, APO, AE 09603 jonathan.c.banta.mil@mail.mil

1. Whittaker S, Knobler R, Ortiz P, et al. Major achievements of the EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force (CLTF). EJC Suppl. 2012;10:46-50.

2. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-205.e16.

3. Kadin ME, Hughey LC, Wood GS. Large-cell transformation of mycosis fungoides-differential diagnosis with implications for clinical management: a consensus statement of the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:374-376.

4. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al; International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

5. Bi MY, Curry JL, Christiano AM, et al. The spectrum of hair loss in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:53-63.

6. Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

7. Jiamton S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Kulthanan K. Clinical features and aggravating factors in nummular eczema in Thais. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31:36-42.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-223.e17.

1. Whittaker S, Knobler R, Ortiz P, et al. Major achievements of the EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force (CLTF). EJC Suppl. 2012;10:46-50.

2. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-205.e16.

3. Kadin ME, Hughey LC, Wood GS. Large-cell transformation of mycosis fungoides-differential diagnosis with implications for clinical management: a consensus statement of the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:374-376.

4. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al; International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

5. Bi MY, Curry JL, Christiano AM, et al. The spectrum of hair loss in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:53-63.

6. Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

7. Jiamton S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Kulthanan K. Clinical features and aggravating factors in nummular eczema in Thais. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31:36-42.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-223.e17.

Diffuse facial rash in a former collegiate wrestler

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, jonathan.f.madden.mil@mail.mil

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, jonathan.f.madden.mil@mail.mil

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, jonathan.f.madden.mil@mail.mil

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

Primary Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis of the Feet: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Test your knowledge on cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with MD-IQ: the medical intelligence quiz. Click here to answer 5 questions.

When to consider Mohs surgery

› Consider recommending Mohs surgery for cancerous lesions that are long-standing or when there is a high risk of local recurrence or metastasis.

› Consider the procedure for the resection of tumors in cosmetically sensitive areas.

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE A 64-year-old white woman with no personal or family history of skin cancer came to our practice complaining of a lesion on her right cheek (FIGURE 1) that had been present for at least 9 months. The lesion had the appearance of a “rodent bite” ulcer that the patient said bled easily when scratched and occasionally drained clear fluid. She had no other complaints. Biopsy confirmed a nodular, infiltrative basal cell carcinoma (BCC). How would you proceed?

BCC is the most common cutaneous malignancy, with an incidence of more than 1 million cases each year in the United States.1 BCCs occur more commonly in men than in women, usually on the head or neck in both sexes.2,3

Specifying BCC subtype has treatment implications. As the terminology indicates, these lesions arise from the basal cell layer of the epidermis, and they can be further defined histologically as superficial, nodular, micronodular, infiltrating, or other subtypes.

Treatment options for BCCs

Selecting a treatment modality from among the many options depends on a lesion’s subtype and its location. Comorbidity can also influence the decision, favoring nonsurgical intervention if an acute or chronic medical condition or overall health status makes a patient a poor surgical candidate.

Surgical options have the highest clearance rates with the fewest recurrences. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has a cure rate of 99% for primary BCCs and 94% for recurrent lesions.4 Standard excision with appropriate margins yields cure rates of 90% and 83%, respectively.4

Superficial destructive options are typically reserved for superficial BCCs. One example, curettage with electrodessication, cures 92% of primary lesions but just 60% of recurrences.4

Additionally, noninvasive modalities such as cryosurgery, laser ablation, radiotherapy, and photodynamic therapy have varying clearance rates. Topical applications of immune system modulators and chemotherapeutic agents including imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil are also available.5 Target lesions for these modalities may include cancers located on surfaces in which surgical excision would result in unacceptable amounts of tissue loss, such as some periocular BCCs.5

CASE Given our patient’s tumor location (adjacent to the lower eyelid) and its nodular and infiltrating histologic subtype, MMS was the best treatment choice to minimize the chance of recurrence and to achieve an acceptable cosmetic outcome.

A tissue-sparing approach

MMS is a tissue-sparing cutaneous surgical technique first described by Dr. Frederick Mohs in 1941.6 The procedure uses real-time microscopic examination of all removed tissue margins, offering maximal tissue preservation and the highest cure rates of all BCC treatments.7

Compared with other surgical techniques, MMS is unique in that the surgeon also serves as the pathologist and performs reconstruction. After clearing tumor margins of all malignant tissue, the surgeon closes the wound using complex techniques such as tissue flaps and grafts that should be avoided with standard excision due to its inadequate real-time margin control.

When MMS would be the treatment of choice. While MMS may be appropriate for a number of situations, common indications include tumors that are long-standing or have a high risk of local recurrence or metastasis; affected areas where tissue preservation is important such as the face and genitalia; and patients who are immunosuppressed.7

Basics of the technique. To systematically visualize and clear 100% of tumor margins, MMS uses a cyclical process of tumor excision, pathology assessment of specimens with microscopy, and mapping of any remaining positive tissue margins noted.4 These cycles, or stages, are repeated until all excised margins are confirmed cancer free. The ability to establish this outcome with certainty is what permits Mohs surgeons to close surgical wounds with flaps, grafts, and other complex closures.

Advantages of MMS over excision alone. Recurrence rates of BCC after MMS are lower than those seen with excision alone. The 5-year cure rate in the treatment of primary tumors with all non-Mohs modalities combined is 91%, whereas the 5-year cure rate with Mohs surgery is 99%.8 This finding is believed to reflect the difference in the methods used to assess excised specimens histologically. In standard surgical excision, the specimen is examined using the “bread loaf” technique in which the surgical margins are examined in consecutive vertical sections (FIGURE 2).4 Because not all of the surgical margins are directly visualized with this technique, it can increase the rate of false-negative results. In contrast, specimens removed by MMS are examined in horizontal sections, and all surgical margins are directly visualized.9

Aesthetic results are another strong point of MMS. For tumor resection in cosmetically sensitive areas, MMS is the standard of care. The Mohs surgeon is trained to use closures that result in less noticeable scars and minimize distortion of surrounding tissue.

CASE With our patient, we circumscribed the clinical margins of the tumor (FIGURE 3A) before performing Mohs surgery. Two procedural stages were needed to clear all surgical margins, leaving a residual defect (FIGURE 3B). We used a cheek advancement flap to repair the wound (FIGURE 3C).

At 4 months postop, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic result (FIGURE 3D).

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew Morrissey, MD, Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Lackland AFB, TX 78236; matthew.morrissey@us.af.mil

1. Feldman S, Pearce DJ, Williford PM. Surgical decision making for basal cell carcinoma of the face. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1119-1120.

2. Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location, and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

3. Harris RB, Griffith K, Moon TE. Trends in the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancers in southeastern Arizona, 1985-1996. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:528-536.

4. Snow SN, Mikhail GR. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 2nd ed. Madison, Wisc: University of Wisconsin Press; 2005.

5. Smith V, Walton S. Treatment of facial basal cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:380371.

6. Mohs RE, Chemosurgery. A microscopically controlled method of cancer excision. Arch Surg. 1941;42:279-295.

7. Drake LA, Dineheart SM, Goltz RW, et al. Guidelines of care for Mohs micrographic surgery. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:271-278.

8. Snow SN, Gunkel J. Mohs surgery. In: Bolongia JI, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2012:2445-2457.