User login

Friable Scalp Nodule

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

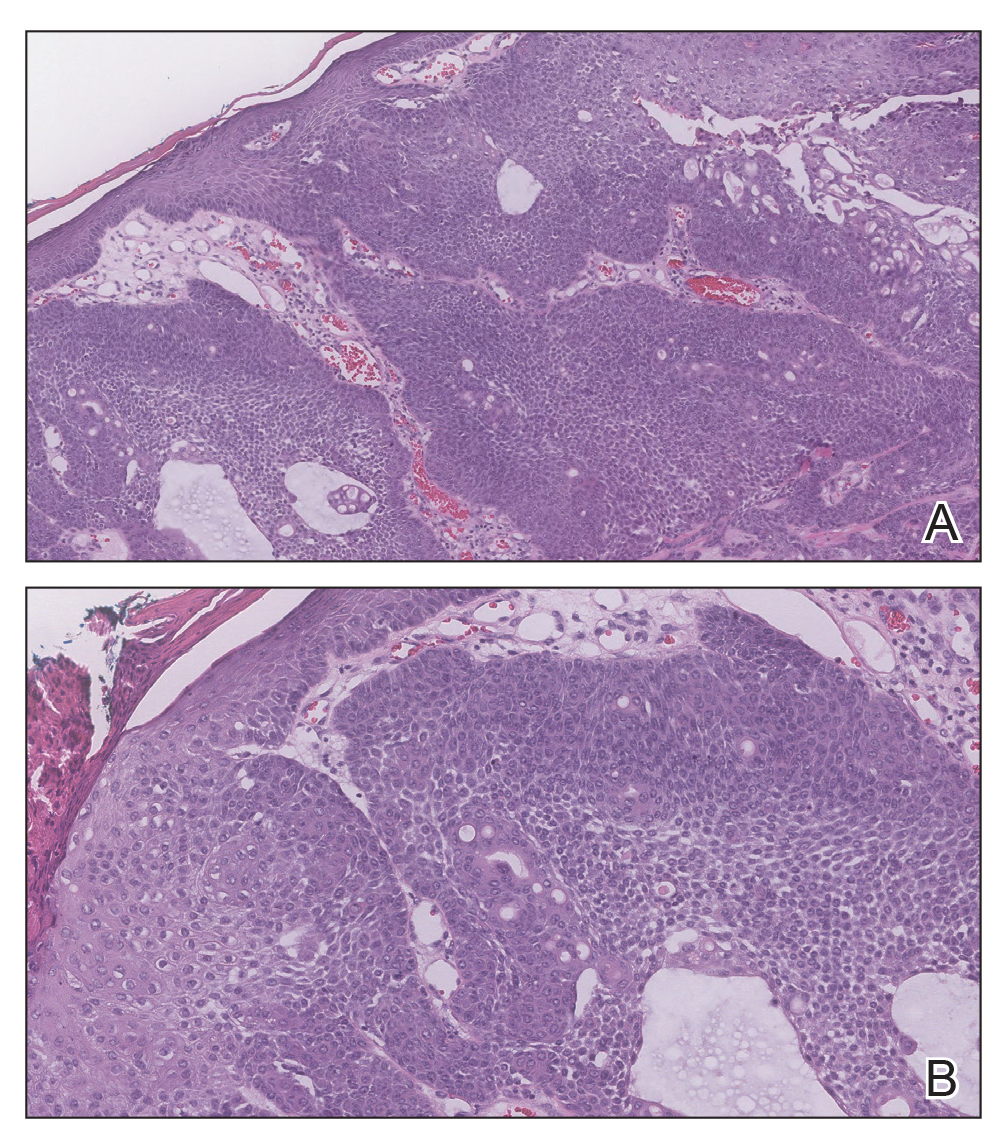

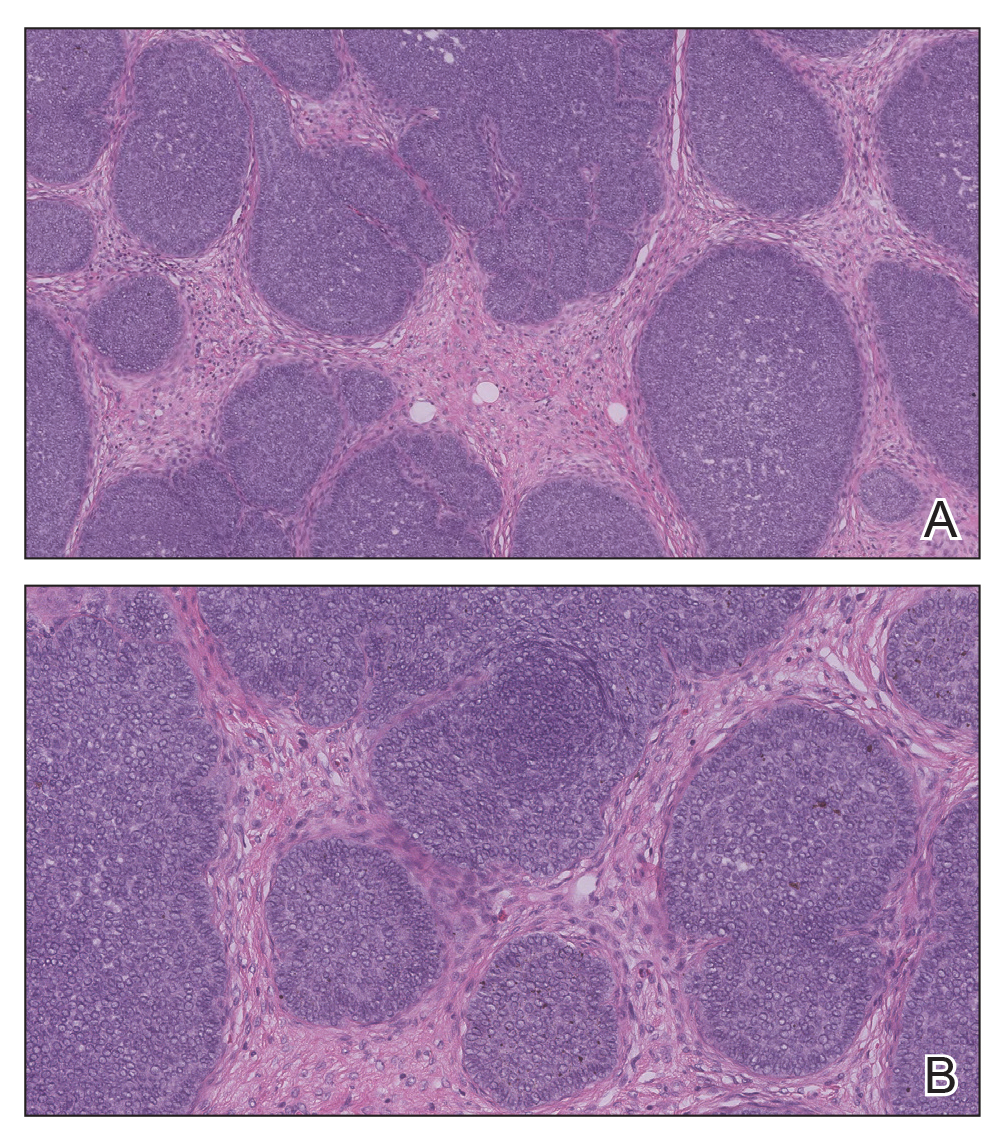

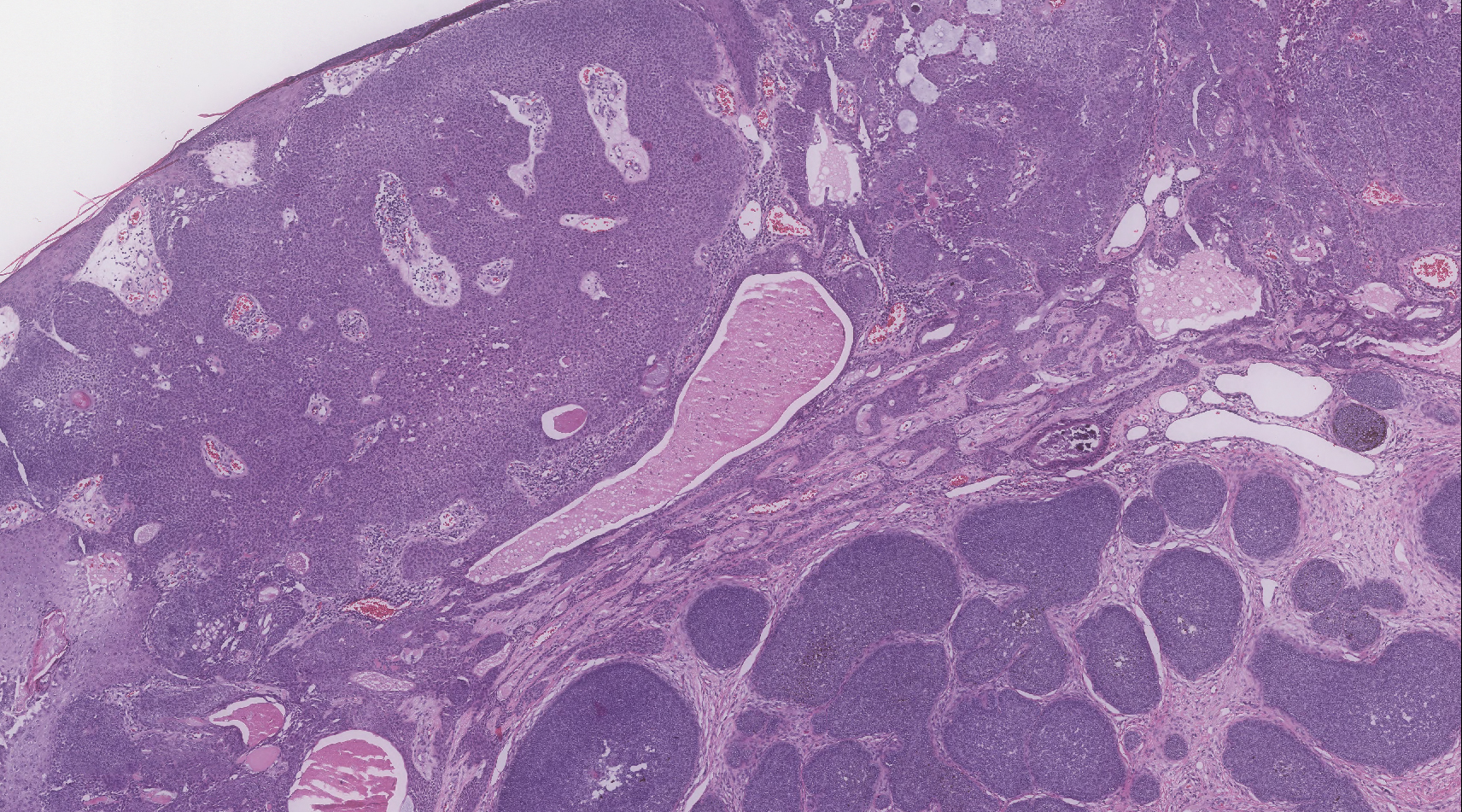

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

A 75-year-old woman presented with an enlarging plaque on the scalp of 5 years' duration. Physical examination revealed a 5.6.2 ×2.9-cm, tan-colored, verrucous plaque with an overlying pink friable nodule on the left occipital scalp. The lesion was not painful or pruritic, and the patient did not have any constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss. The patient denied prior tanning bed use and reported intermittent sun exposure over her lifetime. She denied any prior surgical intervention. There was no family history of similar lesions.

Diffuse facial rash in a former collegiate wrestler

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, jonathan.f.madden.mil@mail.mil

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, jonathan.f.madden.mil@mail.mil

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, jonathan.f.madden.mil@mail.mil

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.