User login

Acral Papulovesicular Eruption in a Soldier Following Smallpox Vaccination

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, heightened concerns over bioterrorism and the potential use of smallpox as a biological weapon made smallpox vaccination a critical component of military readiness. Therefore, the US Military resumed its smallpox vaccination program in 2002 using the first-generation smallpox vaccine (Dryvax, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), a live vaccinia virus vaccine created in the late 19th century. This vaccine was developed by pooling vaccinia strains from the skin of infected cows1 and had previously been used during the worldwide vaccination campaign in the 1970s. Dryvax was associated with various cardiac and cutaneous complications, from benign hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

Due to concerns that the remaining supply of Dryvax was insufficient to vaccinate the US population in the case of a bioterrorism attack, investigators developed the second-generation smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000, Sanofi Pasteur Biologics Co) using advances in vaccine technology.2 ACAM2000 is a plaque-purified isolate of vaccinia virus propagated in cell culture, thereby reducing contaminants and lot-to-lot variation.1 Clinical trials demonstrated comparable immunogenicity and frequency of adverse events compared with Dryvax,2 and ACAM2000 replaced Dryvax in 2008. However, these trials focused on serious adverse events, such as cardiac complications and postvaccinal encephalitis, with less specific characterization and description of cutaneous eruptions.3

Since 2008, there have been few reports of cutaneous adverse reactions following vaccination with ACAM2000. Beachkofsky et al4 described 7 cases of papulovesicular eruptions and 1 case of generalized vaccinia. Freeman and Lenz5 described 4 cases of papulovesicular eruptions, and there has been 1 case of progressive vaccinia reported in a soldier with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia.6 Kramer7 described a patient with multiple vesiculopustular lesions secondary to autoinoculation. The distinct pruritic acral papulovesicular eruptions following ACAM2000 vaccination have occurred in healthy military service members at different locations since the introduction of ACAM2000. We describe an additional case of this unique cutaneous eruption, followed by a review of previously described cutaneous adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination.

Case Report

A 21-year-old female soldier who was otherwise healthy presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic papular eruption involving the upper and lower extremities of 1 week’s duration. The lesions first appeared 8 days after she received the ACAM2000 vaccine. She received no other concurrent vaccines, had no history of atopic dermatitis, and had no systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous indurated papules involving the dorsolateral hands and fingers, as well as the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Based on the clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis included lichen planus, verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, and smallpox vaccine reaction. Erythema multiforme was considered; however, the absence of palmoplantar involvement and typical targetoid lesions made this diagnosis less likely.

Biopsies of lesions on the arm and thigh were performed. Histologic findings revealed interface and spongiotic dermatitis with scattered necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 3). There was no evidence of viral cytopathic effects. Similar clinical and histologic findings have been reported in the literature as acral papulovesicular eruptions following smallpox vaccination or papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination.8 The presence of eosinophils was not conspicuous in the current case and was only a notable finding in 1 of 2 cases previously described by Gaertner et al.8 This may simply be due to an idiosyncratic drug reaction. Furthermore, in the cases described by Beachkofsky et al,4 there were essentially 2 histologic groups. The first group demonstrated a dermal hypersensitivity-type reaction, and the second group demonstrated a lymphocytic capillaritis.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with an acral papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination. Of note, the patient’s presentation was not consistent with other described smallpox vaccine reactions, which included eczema vaccinatum, autoinoculation, generalized vaccinia, and progressive vaccinia. The patient was treated supportively with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%, cool compresses, and oral diphenhydramine as needed for pruritus. The lesions notably improved within the first week of treatment.

Comment

Reported cases of acral papulovesicular eruption4-6 demonstrated an onset of cutaneous symptoms an average of 14 days following vaccination (range, 8–18 days postvaccination). Lesions were benign and self-limited in all cases, with resolution within an average of 25 days (range, 7–71 days). All patients were active-duty military adults with a mean age of 24 years. Supportive treatment varied from topical steroids and oral antihistamines to tapering oral prednisone doses. Of note, all previously reported cases of this reaction occurred in patients who also had received other concurrent or near-concurrent vaccines, including anthrax, hepatitis B, influenza, and typhoid. Our patient represents a unique case of a papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination with no history of concurrent vaccines.

Since the 1970s, smallpox vaccination has been associated with numerous cutaneous reactions, most of which have been reported with the first-generation Dryvax. Minor local reactions occurred in approximately 2% to 6% of vaccinees in clinical trials.9 These reactions included local edema involving the upper arm, satellite lesions within 2.5 cm of the vaccination site, local lymphadenopathy, intense inflammation or viral cellulitis surrounding the inoculation site, and viral lymphangitis tracking to axillary lymph nodes. In clinical trials, these reactions were self-limited and required only symptomatic treatment.9

Autoinoculation is another cutaneous reaction that can occur because Dryvax and ACAM2000 both contain live-attenuated replicating vaccinia virus. Accidental implantation may occur when the high titers of virus present at the vaccine site are subsequently transferred to other sites, especially abnormal mucosa or skin, resulting in an additional primary inoculation site.10

Eczema vaccinatum is a potentially life-threatening reaction that may occur in patients with disruptive skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis. These patients are at risk for massive confluent vaccinia infection of the skin.10 In patients with atopic dermatitis, the virus rapidly disseminates due to both skin barrier dysfunction and impaired immunomodulation, resulting in large confluent skin lesions and the potential for viremia, septic shock, and death.10,11 Mortality from eczema vaccinatum may be reduced by administration of vaccinia immune globulin.10

The vaccinia virus also may spread hematogenously in healthy individuals,10 resulting in a benign reaction called generalized vaccinia. These patients develop pustules on areas of the skin other than the vaccination site. Although typically benign and self-limited, Beachkofsky et al4 described a case of generalized vaccinia in a healthy 34-year-old man resulting in a rapidly progressive vesiculopustular eruption with associated fever and pancytopenia. The patient made a complete recovery over the course of the following month.4

Alternatively, progressive vaccinia is a severe complication of smallpox vaccination seen in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity. It also is known as vaccinia gangrenosum or vaccinia necrosum. These patients develop expanding ulcers due to exaggerated viral replication and cell-to-cell spread of the vaccinia virus.10,11 Hematogenous spread may result in viral implantation at distant sites of the body. This disease slowly progresses over weeks to months, and it often is resistant to treatment and fatal in patients with severe T-cell deficiency.10

Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct cutaneous adverse event following smallpox vaccination. Although further research is needed to discern the pathogenesis of this reaction, it is benign and self-limited, and patients have fully recovered with supportive care. In addition, a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine (Bavarian Nordic) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019.12,13 It is a nonreplicating attenuated viral vaccine that had fewer adverse events compared to ACAM2000 in clinical trials.13 To date, papulovesicular eruptions have not been reported following vaccination with the modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine; however, continued monitoring will help to further characterize any cutaneous reactions to this newer vaccine.

- Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79.

- Monath TP, Caldwell JR, Mundt W, et al. ACAM2000 clonal Vero cell culture vaccinia virus (New York City Board of Health strain)—a second-generation smallpox vaccine for biological defense. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:S31-S44.

- Thomas TN, Reef S, Neff L, et al. A review of the smallpox vaccine adverse events active surveillance system. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S212-S220.

- Beachkofsky TM, Carrizales SC, Bidinger JJ, et al. Adverse events following smallpox vaccination with ACAM2000 in a military population. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:656-661.

- Freeman R, Lenz B. Cutaneous reactions associated with ACAM2000 smallpox vaccination in a deploying U.S. Army unit. Mil Med. 2015;180:E152-E156.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progressive vaccinia in a military smallpox vaccinee—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:532-536.

- Kramer TR. Post–smallpox vaccination skin eruption in a marine. Mil Med. 2018;183:E649-E653.

- Gaertner EM, Groo S, Kim J. Papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination: report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1173-1175.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part I. background, vaccination technique, normal vaccination and revaccination, and expected normal reactions. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:241-250.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part II. adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:251-271.

- Bray M. Understanding smallpox vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1037-1039.

- Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia ankara smallpox vaccine (MVA-BN®) in 56-80-year-old subjects. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0157335.

- Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1897-1908.

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, heightened concerns over bioterrorism and the potential use of smallpox as a biological weapon made smallpox vaccination a critical component of military readiness. Therefore, the US Military resumed its smallpox vaccination program in 2002 using the first-generation smallpox vaccine (Dryvax, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), a live vaccinia virus vaccine created in the late 19th century. This vaccine was developed by pooling vaccinia strains from the skin of infected cows1 and had previously been used during the worldwide vaccination campaign in the 1970s. Dryvax was associated with various cardiac and cutaneous complications, from benign hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

Due to concerns that the remaining supply of Dryvax was insufficient to vaccinate the US population in the case of a bioterrorism attack, investigators developed the second-generation smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000, Sanofi Pasteur Biologics Co) using advances in vaccine technology.2 ACAM2000 is a plaque-purified isolate of vaccinia virus propagated in cell culture, thereby reducing contaminants and lot-to-lot variation.1 Clinical trials demonstrated comparable immunogenicity and frequency of adverse events compared with Dryvax,2 and ACAM2000 replaced Dryvax in 2008. However, these trials focused on serious adverse events, such as cardiac complications and postvaccinal encephalitis, with less specific characterization and description of cutaneous eruptions.3

Since 2008, there have been few reports of cutaneous adverse reactions following vaccination with ACAM2000. Beachkofsky et al4 described 7 cases of papulovesicular eruptions and 1 case of generalized vaccinia. Freeman and Lenz5 described 4 cases of papulovesicular eruptions, and there has been 1 case of progressive vaccinia reported in a soldier with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia.6 Kramer7 described a patient with multiple vesiculopustular lesions secondary to autoinoculation. The distinct pruritic acral papulovesicular eruptions following ACAM2000 vaccination have occurred in healthy military service members at different locations since the introduction of ACAM2000. We describe an additional case of this unique cutaneous eruption, followed by a review of previously described cutaneous adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination.

Case Report

A 21-year-old female soldier who was otherwise healthy presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic papular eruption involving the upper and lower extremities of 1 week’s duration. The lesions first appeared 8 days after she received the ACAM2000 vaccine. She received no other concurrent vaccines, had no history of atopic dermatitis, and had no systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous indurated papules involving the dorsolateral hands and fingers, as well as the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Based on the clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis included lichen planus, verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, and smallpox vaccine reaction. Erythema multiforme was considered; however, the absence of palmoplantar involvement and typical targetoid lesions made this diagnosis less likely.

Biopsies of lesions on the arm and thigh were performed. Histologic findings revealed interface and spongiotic dermatitis with scattered necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 3). There was no evidence of viral cytopathic effects. Similar clinical and histologic findings have been reported in the literature as acral papulovesicular eruptions following smallpox vaccination or papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination.8 The presence of eosinophils was not conspicuous in the current case and was only a notable finding in 1 of 2 cases previously described by Gaertner et al.8 This may simply be due to an idiosyncratic drug reaction. Furthermore, in the cases described by Beachkofsky et al,4 there were essentially 2 histologic groups. The first group demonstrated a dermal hypersensitivity-type reaction, and the second group demonstrated a lymphocytic capillaritis.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with an acral papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination. Of note, the patient’s presentation was not consistent with other described smallpox vaccine reactions, which included eczema vaccinatum, autoinoculation, generalized vaccinia, and progressive vaccinia. The patient was treated supportively with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%, cool compresses, and oral diphenhydramine as needed for pruritus. The lesions notably improved within the first week of treatment.

Comment

Reported cases of acral papulovesicular eruption4-6 demonstrated an onset of cutaneous symptoms an average of 14 days following vaccination (range, 8–18 days postvaccination). Lesions were benign and self-limited in all cases, with resolution within an average of 25 days (range, 7–71 days). All patients were active-duty military adults with a mean age of 24 years. Supportive treatment varied from topical steroids and oral antihistamines to tapering oral prednisone doses. Of note, all previously reported cases of this reaction occurred in patients who also had received other concurrent or near-concurrent vaccines, including anthrax, hepatitis B, influenza, and typhoid. Our patient represents a unique case of a papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination with no history of concurrent vaccines.

Since the 1970s, smallpox vaccination has been associated with numerous cutaneous reactions, most of which have been reported with the first-generation Dryvax. Minor local reactions occurred in approximately 2% to 6% of vaccinees in clinical trials.9 These reactions included local edema involving the upper arm, satellite lesions within 2.5 cm of the vaccination site, local lymphadenopathy, intense inflammation or viral cellulitis surrounding the inoculation site, and viral lymphangitis tracking to axillary lymph nodes. In clinical trials, these reactions were self-limited and required only symptomatic treatment.9

Autoinoculation is another cutaneous reaction that can occur because Dryvax and ACAM2000 both contain live-attenuated replicating vaccinia virus. Accidental implantation may occur when the high titers of virus present at the vaccine site are subsequently transferred to other sites, especially abnormal mucosa or skin, resulting in an additional primary inoculation site.10

Eczema vaccinatum is a potentially life-threatening reaction that may occur in patients with disruptive skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis. These patients are at risk for massive confluent vaccinia infection of the skin.10 In patients with atopic dermatitis, the virus rapidly disseminates due to both skin barrier dysfunction and impaired immunomodulation, resulting in large confluent skin lesions and the potential for viremia, septic shock, and death.10,11 Mortality from eczema vaccinatum may be reduced by administration of vaccinia immune globulin.10

The vaccinia virus also may spread hematogenously in healthy individuals,10 resulting in a benign reaction called generalized vaccinia. These patients develop pustules on areas of the skin other than the vaccination site. Although typically benign and self-limited, Beachkofsky et al4 described a case of generalized vaccinia in a healthy 34-year-old man resulting in a rapidly progressive vesiculopustular eruption with associated fever and pancytopenia. The patient made a complete recovery over the course of the following month.4

Alternatively, progressive vaccinia is a severe complication of smallpox vaccination seen in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity. It also is known as vaccinia gangrenosum or vaccinia necrosum. These patients develop expanding ulcers due to exaggerated viral replication and cell-to-cell spread of the vaccinia virus.10,11 Hematogenous spread may result in viral implantation at distant sites of the body. This disease slowly progresses over weeks to months, and it often is resistant to treatment and fatal in patients with severe T-cell deficiency.10

Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct cutaneous adverse event following smallpox vaccination. Although further research is needed to discern the pathogenesis of this reaction, it is benign and self-limited, and patients have fully recovered with supportive care. In addition, a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine (Bavarian Nordic) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019.12,13 It is a nonreplicating attenuated viral vaccine that had fewer adverse events compared to ACAM2000 in clinical trials.13 To date, papulovesicular eruptions have not been reported following vaccination with the modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine; however, continued monitoring will help to further characterize any cutaneous reactions to this newer vaccine.

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, heightened concerns over bioterrorism and the potential use of smallpox as a biological weapon made smallpox vaccination a critical component of military readiness. Therefore, the US Military resumed its smallpox vaccination program in 2002 using the first-generation smallpox vaccine (Dryvax, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), a live vaccinia virus vaccine created in the late 19th century. This vaccine was developed by pooling vaccinia strains from the skin of infected cows1 and had previously been used during the worldwide vaccination campaign in the 1970s. Dryvax was associated with various cardiac and cutaneous complications, from benign hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

Due to concerns that the remaining supply of Dryvax was insufficient to vaccinate the US population in the case of a bioterrorism attack, investigators developed the second-generation smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000, Sanofi Pasteur Biologics Co) using advances in vaccine technology.2 ACAM2000 is a plaque-purified isolate of vaccinia virus propagated in cell culture, thereby reducing contaminants and lot-to-lot variation.1 Clinical trials demonstrated comparable immunogenicity and frequency of adverse events compared with Dryvax,2 and ACAM2000 replaced Dryvax in 2008. However, these trials focused on serious adverse events, such as cardiac complications and postvaccinal encephalitis, with less specific characterization and description of cutaneous eruptions.3

Since 2008, there have been few reports of cutaneous adverse reactions following vaccination with ACAM2000. Beachkofsky et al4 described 7 cases of papulovesicular eruptions and 1 case of generalized vaccinia. Freeman and Lenz5 described 4 cases of papulovesicular eruptions, and there has been 1 case of progressive vaccinia reported in a soldier with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia.6 Kramer7 described a patient with multiple vesiculopustular lesions secondary to autoinoculation. The distinct pruritic acral papulovesicular eruptions following ACAM2000 vaccination have occurred in healthy military service members at different locations since the introduction of ACAM2000. We describe an additional case of this unique cutaneous eruption, followed by a review of previously described cutaneous adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination.

Case Report

A 21-year-old female soldier who was otherwise healthy presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic papular eruption involving the upper and lower extremities of 1 week’s duration. The lesions first appeared 8 days after she received the ACAM2000 vaccine. She received no other concurrent vaccines, had no history of atopic dermatitis, and had no systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous indurated papules involving the dorsolateral hands and fingers, as well as the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Based on the clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis included lichen planus, verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, and smallpox vaccine reaction. Erythema multiforme was considered; however, the absence of palmoplantar involvement and typical targetoid lesions made this diagnosis less likely.

Biopsies of lesions on the arm and thigh were performed. Histologic findings revealed interface and spongiotic dermatitis with scattered necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 3). There was no evidence of viral cytopathic effects. Similar clinical and histologic findings have been reported in the literature as acral papulovesicular eruptions following smallpox vaccination or papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination.8 The presence of eosinophils was not conspicuous in the current case and was only a notable finding in 1 of 2 cases previously described by Gaertner et al.8 This may simply be due to an idiosyncratic drug reaction. Furthermore, in the cases described by Beachkofsky et al,4 there were essentially 2 histologic groups. The first group demonstrated a dermal hypersensitivity-type reaction, and the second group demonstrated a lymphocytic capillaritis.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with an acral papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination. Of note, the patient’s presentation was not consistent with other described smallpox vaccine reactions, which included eczema vaccinatum, autoinoculation, generalized vaccinia, and progressive vaccinia. The patient was treated supportively with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%, cool compresses, and oral diphenhydramine as needed for pruritus. The lesions notably improved within the first week of treatment.

Comment

Reported cases of acral papulovesicular eruption4-6 demonstrated an onset of cutaneous symptoms an average of 14 days following vaccination (range, 8–18 days postvaccination). Lesions were benign and self-limited in all cases, with resolution within an average of 25 days (range, 7–71 days). All patients were active-duty military adults with a mean age of 24 years. Supportive treatment varied from topical steroids and oral antihistamines to tapering oral prednisone doses. Of note, all previously reported cases of this reaction occurred in patients who also had received other concurrent or near-concurrent vaccines, including anthrax, hepatitis B, influenza, and typhoid. Our patient represents a unique case of a papulovesicular eruption following smallpox vaccination with no history of concurrent vaccines.

Since the 1970s, smallpox vaccination has been associated with numerous cutaneous reactions, most of which have been reported with the first-generation Dryvax. Minor local reactions occurred in approximately 2% to 6% of vaccinees in clinical trials.9 These reactions included local edema involving the upper arm, satellite lesions within 2.5 cm of the vaccination site, local lymphadenopathy, intense inflammation or viral cellulitis surrounding the inoculation site, and viral lymphangitis tracking to axillary lymph nodes. In clinical trials, these reactions were self-limited and required only symptomatic treatment.9

Autoinoculation is another cutaneous reaction that can occur because Dryvax and ACAM2000 both contain live-attenuated replicating vaccinia virus. Accidental implantation may occur when the high titers of virus present at the vaccine site are subsequently transferred to other sites, especially abnormal mucosa or skin, resulting in an additional primary inoculation site.10

Eczema vaccinatum is a potentially life-threatening reaction that may occur in patients with disruptive skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis. These patients are at risk for massive confluent vaccinia infection of the skin.10 In patients with atopic dermatitis, the virus rapidly disseminates due to both skin barrier dysfunction and impaired immunomodulation, resulting in large confluent skin lesions and the potential for viremia, septic shock, and death.10,11 Mortality from eczema vaccinatum may be reduced by administration of vaccinia immune globulin.10

The vaccinia virus also may spread hematogenously in healthy individuals,10 resulting in a benign reaction called generalized vaccinia. These patients develop pustules on areas of the skin other than the vaccination site. Although typically benign and self-limited, Beachkofsky et al4 described a case of generalized vaccinia in a healthy 34-year-old man resulting in a rapidly progressive vesiculopustular eruption with associated fever and pancytopenia. The patient made a complete recovery over the course of the following month.4

Alternatively, progressive vaccinia is a severe complication of smallpox vaccination seen in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity. It also is known as vaccinia gangrenosum or vaccinia necrosum. These patients develop expanding ulcers due to exaggerated viral replication and cell-to-cell spread of the vaccinia virus.10,11 Hematogenous spread may result in viral implantation at distant sites of the body. This disease slowly progresses over weeks to months, and it often is resistant to treatment and fatal in patients with severe T-cell deficiency.10

Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct cutaneous adverse event following smallpox vaccination. Although further research is needed to discern the pathogenesis of this reaction, it is benign and self-limited, and patients have fully recovered with supportive care. In addition, a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine (Bavarian Nordic) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019.12,13 It is a nonreplicating attenuated viral vaccine that had fewer adverse events compared to ACAM2000 in clinical trials.13 To date, papulovesicular eruptions have not been reported following vaccination with the modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine; however, continued monitoring will help to further characterize any cutaneous reactions to this newer vaccine.

- Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79.

- Monath TP, Caldwell JR, Mundt W, et al. ACAM2000 clonal Vero cell culture vaccinia virus (New York City Board of Health strain)—a second-generation smallpox vaccine for biological defense. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:S31-S44.

- Thomas TN, Reef S, Neff L, et al. A review of the smallpox vaccine adverse events active surveillance system. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S212-S220.

- Beachkofsky TM, Carrizales SC, Bidinger JJ, et al. Adverse events following smallpox vaccination with ACAM2000 in a military population. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:656-661.

- Freeman R, Lenz B. Cutaneous reactions associated with ACAM2000 smallpox vaccination in a deploying U.S. Army unit. Mil Med. 2015;180:E152-E156.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progressive vaccinia in a military smallpox vaccinee—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:532-536.

- Kramer TR. Post–smallpox vaccination skin eruption in a marine. Mil Med. 2018;183:E649-E653.

- Gaertner EM, Groo S, Kim J. Papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination: report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1173-1175.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part I. background, vaccination technique, normal vaccination and revaccination, and expected normal reactions. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:241-250.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part II. adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:251-271.

- Bray M. Understanding smallpox vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1037-1039.

- Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia ankara smallpox vaccine (MVA-BN®) in 56-80-year-old subjects. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0157335.

- Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1897-1908.

- Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79.

- Monath TP, Caldwell JR, Mundt W, et al. ACAM2000 clonal Vero cell culture vaccinia virus (New York City Board of Health strain)—a second-generation smallpox vaccine for biological defense. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:S31-S44.

- Thomas TN, Reef S, Neff L, et al. A review of the smallpox vaccine adverse events active surveillance system. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S212-S220.

- Beachkofsky TM, Carrizales SC, Bidinger JJ, et al. Adverse events following smallpox vaccination with ACAM2000 in a military population. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:656-661.

- Freeman R, Lenz B. Cutaneous reactions associated with ACAM2000 smallpox vaccination in a deploying U.S. Army unit. Mil Med. 2015;180:E152-E156.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progressive vaccinia in a military smallpox vaccinee—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:532-536.

- Kramer TR. Post–smallpox vaccination skin eruption in a marine. Mil Med. 2018;183:E649-E653.

- Gaertner EM, Groo S, Kim J. Papular spongiotic dermatitis of smallpox vaccination: report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1173-1175.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part I. background, vaccination technique, normal vaccination and revaccination, and expected normal reactions. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:241-250.

- Fulginiti VA, Papier A, Lane JM, et al. Smallpox vaccination: a review, part II. adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:251-271.

- Bray M. Understanding smallpox vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1037-1039.

- Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia ankara smallpox vaccine (MVA-BN®) in 56-80-year-old subjects. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0157335.

- Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1897-1908.

Practice Points

- There are several potential cutaneous adverse reactions associated with smallpox vaccination, ranging from benign self-limited hypersensitivity reactions to life-threatening eczema vaccinatum and progressive vaccinia.

- Acral papulovesicular eruption is a distinct presentation that has been described in the US Military following vaccination with the second-generation live smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000).

Asymptomatic, Slowly Enlarging Papule on the Nipple

The Diagnosis: Erosive Adenomatosis of the Nipple

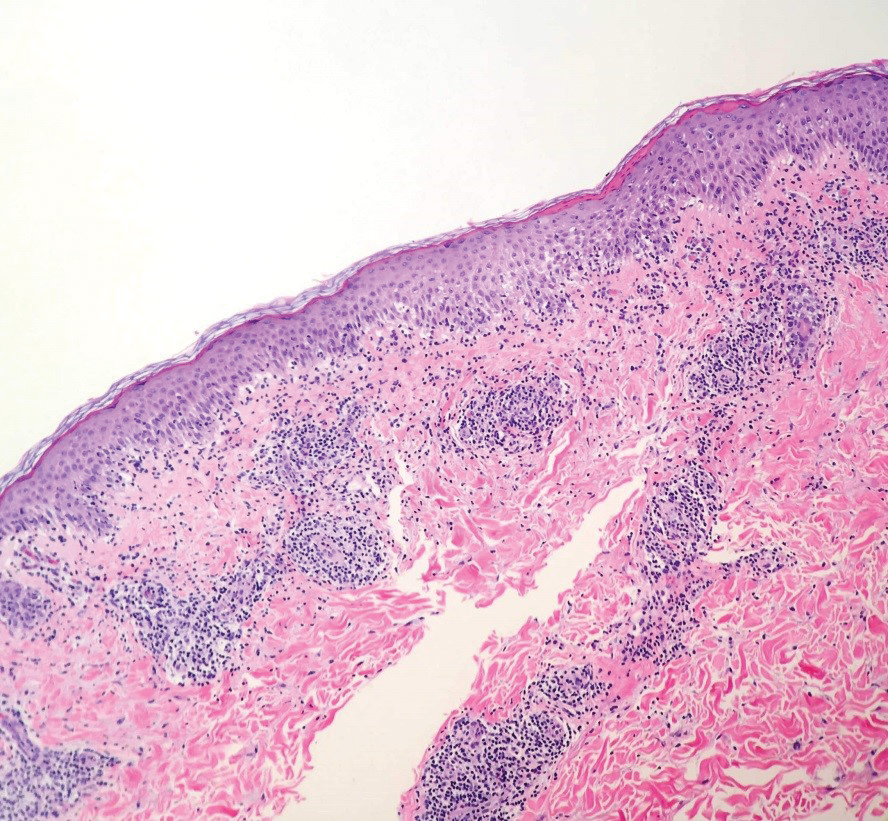

Biopsy of the lesion revealed proliferative sections of glandular epithelium demonstrating apocrine differentiation, connecting to the epidermis and traversing throughout the entire dermis of the specimen (Figure). There were papillary projections of dilated ducts with a retained layer of myoepithelial cells surrounding the epithelial layers. Cytologic atypia was not appreciated. The patient was diagnosed with erosive adenomatosis of the nipple (EAN), also known as nipple adenoma. The lesion subsequently was treated and cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). At 8-month follow-up there was no clinical recurrence of the lesion, and the patient was satisfied with the overall cosmetic appearance and conservation of the areola. The patient was followed clinically with annual breast examinations and mammography to monitor future recurrence.

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is an uncommon benign proliferative process of the lactiferous ducts of the nipple. Recognizing EAN is important because it resembles malignant breast diseases such as Paget disease of the nipple and invasive breast carcinoma. Due to these similarities, early cases of EAN have resulted in unnecessary mastectomies before the benignity of the condition was established.1 Accurate diagnosis is important to both the patient and the clinician for treatment planning as well as psychosocial consequences associated with the potential removal of this anatomically and cosmetically sensitive area.

Reviewing the literature on EAN is complicated by the variety of terms used to describe this condition, including but not limited to nipple adenoma, nipple duct adenoma, papillary adenoma of the nipple, and florid papillomatosis of the nipple. In 1955, Jones2 described EAN using the term florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. In 1962, Handley and Thackray1 argued that adenoma of the nipple was a more descriptive term because it more closely described the appearance of a sweat gland adenoma. They reasoned that adenoma of the nipple is a separate process from ductal papilloma due to the adenomatous proliferation into the nipple stroma rather than the lumen of the nipple ducts.1 The term adenoma of the nipple was further supported in 1965 by Taylor and Robertson.3 In 1959, Le Gal et al4 used the term erosive adenomatosis of the nipple to describe the erosive nature of nipple adenoma. The term nipple adenoma was published in the 2012 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast with 4 common histologic subtypes.5,6

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is clinically indistinguishable from Paget disease of the nipple, thus biopsy is essential for accurate diagnosis. In contrast to Paget disease, EAN tends to present in younger patients and progresses more slowly, and symptoms may be exacerbated around menstruation.1 Case reports demonstrate that patients may wait years before seeking medical attention for EAN.1,3,7,8 Presenting symptoms may include inflammation, crusting, nipple skin erosion, itching, and pain. Serous or sanguineous discharge from the lesions also is commonly reported. Palpation may reveal a small, hard, or elastic nodule within or underlying the nipple. In addition to Paget disease, EAN may resemble squamous cell carcinoma of the nipple, eczema, psoriasis, or a skin infection.6 Axillary lymphadenopathy is not present in the absence of a concomitant breast malignancy.8 On biopsy, nipple adenoma represents ductal proliferation of glandular structures within the stroma of the nipple that is well circumscribed but without borders. The erosive appearance of the lesion is produced by extensions of the glandular epithelium on the surface of the nipple.1,6 Specific to EAN is the presence of 2 cell types: an inner columnar epithelium and an outer cuboidal myoepithelium. These 2 cell types are present in normal lactiferous ducts; however, normal ducts are highly organized compared to EAN.9

After confirmation of EAN by nipple biopsy, complete surgical excision has been the gold standard for treatment, followed by reconstructive surgery.6 Handley and Thackray1 advocated for total excision of the nipple and areola with an underlying wedge of breast tissue to facilitate wound closure. More recently, successful alternative forms of treatment have been utilized to minimize disfiguring surgery. Alternative treatments include MMS,8 cryotherapy,10 and nipple splitting enucleation.6 Treatment with MMS has resulted in nipple sparing with the least amount of surface area sacrificed (1.1 cm2).9 Our case and prior case reports demonstrate that the tissue sparing potential of MMS is appropriate for the treatment of EAN, though traditionally it has been reserved for more malignant tumors. Preserving this sensitive area is both cosmetically and psychologically advantageous for the patient and thus should be considered when reviewing treatment options for EAN.

- Handley RS, Thackray AC. Adenoma of nipple. Br J Cancer. 1962;16:187-194.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Taylor HB, Robertson AG. Adenomas of the nipple. Cancer. 1965:18:995-1002.

- Le Gal Y, Gros CM, Bader P. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple [in French]. Ann Anat Pathol (Paris). 1959;4:292-304.

- Eusebi V, Lester S. Tumours of the nipple. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Lyon, France: IARC; 2012.

- Spohn GP, Trotter SC, Tozbician G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Kowal R, Miller CJ, Elenitsas R. Eroded patch on the nipple of a 57-year-old woman. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:933-938.

- Van Mierlo PL, Geelen GM, Neumann HA. Mohs micrographic surgery for an erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:681-683.

- Brankov N, Nino T, Hsiang D, et al. Utilizing Mohs surgery for tissue preservation in erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:684-686.

- Kuflik EG. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:270-271.

The Diagnosis: Erosive Adenomatosis of the Nipple

Biopsy of the lesion revealed proliferative sections of glandular epithelium demonstrating apocrine differentiation, connecting to the epidermis and traversing throughout the entire dermis of the specimen (Figure). There were papillary projections of dilated ducts with a retained layer of myoepithelial cells surrounding the epithelial layers. Cytologic atypia was not appreciated. The patient was diagnosed with erosive adenomatosis of the nipple (EAN), also known as nipple adenoma. The lesion subsequently was treated and cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). At 8-month follow-up there was no clinical recurrence of the lesion, and the patient was satisfied with the overall cosmetic appearance and conservation of the areola. The patient was followed clinically with annual breast examinations and mammography to monitor future recurrence.

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is an uncommon benign proliferative process of the lactiferous ducts of the nipple. Recognizing EAN is important because it resembles malignant breast diseases such as Paget disease of the nipple and invasive breast carcinoma. Due to these similarities, early cases of EAN have resulted in unnecessary mastectomies before the benignity of the condition was established.1 Accurate diagnosis is important to both the patient and the clinician for treatment planning as well as psychosocial consequences associated with the potential removal of this anatomically and cosmetically sensitive area.

Reviewing the literature on EAN is complicated by the variety of terms used to describe this condition, including but not limited to nipple adenoma, nipple duct adenoma, papillary adenoma of the nipple, and florid papillomatosis of the nipple. In 1955, Jones2 described EAN using the term florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. In 1962, Handley and Thackray1 argued that adenoma of the nipple was a more descriptive term because it more closely described the appearance of a sweat gland adenoma. They reasoned that adenoma of the nipple is a separate process from ductal papilloma due to the adenomatous proliferation into the nipple stroma rather than the lumen of the nipple ducts.1 The term adenoma of the nipple was further supported in 1965 by Taylor and Robertson.3 In 1959, Le Gal et al4 used the term erosive adenomatosis of the nipple to describe the erosive nature of nipple adenoma. The term nipple adenoma was published in the 2012 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast with 4 common histologic subtypes.5,6

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is clinically indistinguishable from Paget disease of the nipple, thus biopsy is essential for accurate diagnosis. In contrast to Paget disease, EAN tends to present in younger patients and progresses more slowly, and symptoms may be exacerbated around menstruation.1 Case reports demonstrate that patients may wait years before seeking medical attention for EAN.1,3,7,8 Presenting symptoms may include inflammation, crusting, nipple skin erosion, itching, and pain. Serous or sanguineous discharge from the lesions also is commonly reported. Palpation may reveal a small, hard, or elastic nodule within or underlying the nipple. In addition to Paget disease, EAN may resemble squamous cell carcinoma of the nipple, eczema, psoriasis, or a skin infection.6 Axillary lymphadenopathy is not present in the absence of a concomitant breast malignancy.8 On biopsy, nipple adenoma represents ductal proliferation of glandular structures within the stroma of the nipple that is well circumscribed but without borders. The erosive appearance of the lesion is produced by extensions of the glandular epithelium on the surface of the nipple.1,6 Specific to EAN is the presence of 2 cell types: an inner columnar epithelium and an outer cuboidal myoepithelium. These 2 cell types are present in normal lactiferous ducts; however, normal ducts are highly organized compared to EAN.9

After confirmation of EAN by nipple biopsy, complete surgical excision has been the gold standard for treatment, followed by reconstructive surgery.6 Handley and Thackray1 advocated for total excision of the nipple and areola with an underlying wedge of breast tissue to facilitate wound closure. More recently, successful alternative forms of treatment have been utilized to minimize disfiguring surgery. Alternative treatments include MMS,8 cryotherapy,10 and nipple splitting enucleation.6 Treatment with MMS has resulted in nipple sparing with the least amount of surface area sacrificed (1.1 cm2).9 Our case and prior case reports demonstrate that the tissue sparing potential of MMS is appropriate for the treatment of EAN, though traditionally it has been reserved for more malignant tumors. Preserving this sensitive area is both cosmetically and psychologically advantageous for the patient and thus should be considered when reviewing treatment options for EAN.

The Diagnosis: Erosive Adenomatosis of the Nipple

Biopsy of the lesion revealed proliferative sections of glandular epithelium demonstrating apocrine differentiation, connecting to the epidermis and traversing throughout the entire dermis of the specimen (Figure). There were papillary projections of dilated ducts with a retained layer of myoepithelial cells surrounding the epithelial layers. Cytologic atypia was not appreciated. The patient was diagnosed with erosive adenomatosis of the nipple (EAN), also known as nipple adenoma. The lesion subsequently was treated and cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). At 8-month follow-up there was no clinical recurrence of the lesion, and the patient was satisfied with the overall cosmetic appearance and conservation of the areola. The patient was followed clinically with annual breast examinations and mammography to monitor future recurrence.

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is an uncommon benign proliferative process of the lactiferous ducts of the nipple. Recognizing EAN is important because it resembles malignant breast diseases such as Paget disease of the nipple and invasive breast carcinoma. Due to these similarities, early cases of EAN have resulted in unnecessary mastectomies before the benignity of the condition was established.1 Accurate diagnosis is important to both the patient and the clinician for treatment planning as well as psychosocial consequences associated with the potential removal of this anatomically and cosmetically sensitive area.

Reviewing the literature on EAN is complicated by the variety of terms used to describe this condition, including but not limited to nipple adenoma, nipple duct adenoma, papillary adenoma of the nipple, and florid papillomatosis of the nipple. In 1955, Jones2 described EAN using the term florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. In 1962, Handley and Thackray1 argued that adenoma of the nipple was a more descriptive term because it more closely described the appearance of a sweat gland adenoma. They reasoned that adenoma of the nipple is a separate process from ductal papilloma due to the adenomatous proliferation into the nipple stroma rather than the lumen of the nipple ducts.1 The term adenoma of the nipple was further supported in 1965 by Taylor and Robertson.3 In 1959, Le Gal et al4 used the term erosive adenomatosis of the nipple to describe the erosive nature of nipple adenoma. The term nipple adenoma was published in the 2012 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast with 4 common histologic subtypes.5,6

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is clinically indistinguishable from Paget disease of the nipple, thus biopsy is essential for accurate diagnosis. In contrast to Paget disease, EAN tends to present in younger patients and progresses more slowly, and symptoms may be exacerbated around menstruation.1 Case reports demonstrate that patients may wait years before seeking medical attention for EAN.1,3,7,8 Presenting symptoms may include inflammation, crusting, nipple skin erosion, itching, and pain. Serous or sanguineous discharge from the lesions also is commonly reported. Palpation may reveal a small, hard, or elastic nodule within or underlying the nipple. In addition to Paget disease, EAN may resemble squamous cell carcinoma of the nipple, eczema, psoriasis, or a skin infection.6 Axillary lymphadenopathy is not present in the absence of a concomitant breast malignancy.8 On biopsy, nipple adenoma represents ductal proliferation of glandular structures within the stroma of the nipple that is well circumscribed but without borders. The erosive appearance of the lesion is produced by extensions of the glandular epithelium on the surface of the nipple.1,6 Specific to EAN is the presence of 2 cell types: an inner columnar epithelium and an outer cuboidal myoepithelium. These 2 cell types are present in normal lactiferous ducts; however, normal ducts are highly organized compared to EAN.9

After confirmation of EAN by nipple biopsy, complete surgical excision has been the gold standard for treatment, followed by reconstructive surgery.6 Handley and Thackray1 advocated for total excision of the nipple and areola with an underlying wedge of breast tissue to facilitate wound closure. More recently, successful alternative forms of treatment have been utilized to minimize disfiguring surgery. Alternative treatments include MMS,8 cryotherapy,10 and nipple splitting enucleation.6 Treatment with MMS has resulted in nipple sparing with the least amount of surface area sacrificed (1.1 cm2).9 Our case and prior case reports demonstrate that the tissue sparing potential of MMS is appropriate for the treatment of EAN, though traditionally it has been reserved for more malignant tumors. Preserving this sensitive area is both cosmetically and psychologically advantageous for the patient and thus should be considered when reviewing treatment options for EAN.

- Handley RS, Thackray AC. Adenoma of nipple. Br J Cancer. 1962;16:187-194.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Taylor HB, Robertson AG. Adenomas of the nipple. Cancer. 1965:18:995-1002.

- Le Gal Y, Gros CM, Bader P. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple [in French]. Ann Anat Pathol (Paris). 1959;4:292-304.

- Eusebi V, Lester S. Tumours of the nipple. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Lyon, France: IARC; 2012.

- Spohn GP, Trotter SC, Tozbician G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Kowal R, Miller CJ, Elenitsas R. Eroded patch on the nipple of a 57-year-old woman. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:933-938.

- Van Mierlo PL, Geelen GM, Neumann HA. Mohs micrographic surgery for an erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:681-683.

- Brankov N, Nino T, Hsiang D, et al. Utilizing Mohs surgery for tissue preservation in erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:684-686.

- Kuflik EG. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:270-271.

- Handley RS, Thackray AC. Adenoma of nipple. Br J Cancer. 1962;16:187-194.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Taylor HB, Robertson AG. Adenomas of the nipple. Cancer. 1965:18:995-1002.

- Le Gal Y, Gros CM, Bader P. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple [in French]. Ann Anat Pathol (Paris). 1959;4:292-304.

- Eusebi V, Lester S. Tumours of the nipple. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Lyon, France: IARC; 2012.

- Spohn GP, Trotter SC, Tozbician G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Kowal R, Miller CJ, Elenitsas R. Eroded patch on the nipple of a 57-year-old woman. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:933-938.

- Van Mierlo PL, Geelen GM, Neumann HA. Mohs micrographic surgery for an erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:681-683.

- Brankov N, Nino T, Hsiang D, et al. Utilizing Mohs surgery for tissue preservation in erosive adenomatosis of the nipple. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:684-686.

- Kuflik EG. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:270-271.

A 61-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic, slowly enlarging, 9-mm, firm, red papule on the left nipple of 2 years' duration. She had no notable medical history, including a BI-RADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) mammogram score of 2 that was suggestive of benign findings 2 years prior. A repeat mammogram ordered by radiology and completed before presenting to dermatology had a BI-RADS score of 4, noting a concerning feature in the area of the lesion and prompting a biopsy.