User login

“Just Getting a Cup of Coffee”—Considering Best Practices for Patients’ Movement off the Hospital Floor

A 58-year-old man with a remote history of endocarditis and no prior injection drug use was admitted to the inpatient medicine service with fever and concern for recurrent endocarditis. A transthoracic echocardiogram was unremarkable and the patient remained clinically stable. A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was scheduled for the following morning, but during nursing rounds, the patient was missing from his room. Multiple staff members searched for the patient and eventually located him in the hospital lobby drinking a cup of coffee purchased from the cafeteria. Despite his opposition, he was escorted back to his room and advised to not leave the floor again. Later that day, the patient became frustrated and left the hospital before his scheduled TEE. He was subsequently lost to follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Patients are admitted to the hospital based upon a medical determination that the patient requires acute observation, evaluation, or treatment. Once admitted, healthcare providers may impose restrictions on the patient’s movement in the hospital, such as restrictions on leaving their assigned floor. Managing the movement of hospitalized patients poses significant challenges for the clinical staff because of the difficulty of providing a treatment environment that ensures safe and efficient delivery of care while promoting patients’ preferences for an unrestrictive environment that respects their independence.1,2 Broad limits may make it easier for staff to care for patients and reduce concerns about liability, but they may also frustrate patients who may be medically, psychiatrically, and physically stable and do not require stringent monitoring (eg, completing a course of intravenous antibiotics or awaiting placement at outside facilities).

Although this issue has broad implications for patient safety and hospital liability, authoritative guidance and evidence-based literature are lacking. Without clear guidelines, healthcare staff members are likely to spend more time in managing each individual request to leave the floor because they do not have a systematic strategy for making fair and consistent decisions. Here, we describe the patient and institutional considerations when managing patient movement in the hospital. We refer to “patient movement” specifically as a patient’s choice to move to different locations within the hospital, but outside of their assigned room and/or floor. This does not include scheduled, supervised ambulation activities, such as physical therapy.

POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES OF LIBERALIZING AND RESTRICTING INPATIENT MOVEMENT

Practices that promote patient movement offer significant benefits and risks. Enhancing movement is likely to reduce the “physiologic disruption”3 of hospitalization while improving patients’ overall satisfaction and alignment with patient-centered care. Liberalized movement also promotes independence and ambulation that reduces the rate of physical deconditioning.4

Despite theoretical benefits, hospitals may be more concerned about adverse events related to patient movement, such as falls, the use of illicit substances, or elopement. Given that hospitals may be legally5 and financially responsible6 for adverse events associated with patient movement, allowances for off-floor movement should be carefully considered with input from risk management, physicians, nursing leadership, patient advocates, and hospital administration.

Additionally, unannounced movement off the floor may interfere with timely and efficient care by causing lapses in monitoring, such as cardiac telemetry,7 medication administration, and scheduled diagnostic tests. In these situations, the risks of patient absence from the floor are significant and may ultimately negate the benefits of continued hospitalization by compromising the central elements of patient care.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Patients’ requests to leave the hospital floor should be evaluated systemically and transparently to promote fair, high-value care. First, a request for liberalized movement should prompt physicians that the patient may no longer require hospitalization and may be ready for the transition to outpatient care.8 If the patient still requires inpatient care, then the medical practitioner should make a clinical determination if the patient is medically stable enough to leave their hospital floor. The provider should first identify when the liberalization of movement would be universally inappropriate, such as in patients who are physically unable to ambulate without posing significant harm to themselves. This includes an accidental fall (usually while walking5), which is one of the most commonly reported adverse events in an inpatient setting.9 Additionally, patients with significant cognitive impairments or those lacking in decision-making capacity may be restricted from leaving their floors unescorted, as they are at a higher risk of disorientation, falls, and death.10

In determining movement restrictions for patients in isolation, hospitals should refer to the existing guidelines on isolation precautions for the transmission of communicable infections11,12 and neutropenic precautions.13 Additionally, movement restriction for patients who are isolated after screening positive for certain drug-resistant organisms (eg, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci) is controversial and should be evaluated based on the available medical evidence and standards.14-16

When making a risk-benefit determination about movement, providers should also assess the intent and the potentially unmet needs behind the patient’s request. Patient-centered reasons for enhanced freedom of movement within the hospital include a desire for exercise, greater food choice, and visiting with loved ones, all of which can enable patients to manage the well-known inconveniences and stresses of hospitalization. In contrast, there may be concerns for other intentions behind leaving assigned floors based on the patient’s clinical history, such as the surreptitious use of illicit substances or attempts to elope from the hospital. Advising restriction of movement is justifiable if there is a significant concern for behavior that undermines the safe delivery of care. In patients with active substance use disorders, the appropriate treatment of pain or withdrawal symptoms may better address the patients’ unmet needs, but a lower threshold to restrict movement may be reasonable given the significant risks involved. However, given the widespread stigmatization of patients with substance use disorders,17 institutional policy and clinicians should adhere to systematic, transparent, and consistent risk assessments for all patients in order to minimize the potential for introducing or exacerbating disparities in care.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

In order to work productively with admitted patients, strong practices honor patients’ autonomy by specifying

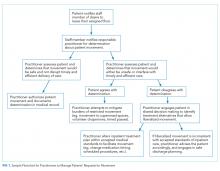

Patients may request or even demand to leave the floor after a healthcare provider has determined that doing so would be unsafe and/or undermine the timely and efficient delivery of care. In these cases, shared decision-making (SDM) can help identify acceptable solutions within the identified constraints. SDM combines the physicians’ experience, expertise, and knowledge of medical evidence with patients’ values, needs, and preferences for care.19 If patients continue to request to leave the floor after the restriction has been communicated, physicians should discuss whether the current treatment plan should be renegotiated to include a relatively minor modification (eg, a change in the timing or route of administration of medication). If inpatient care cannot be provided safely within the patient’s preferences for movement and attempts to accommodate the patient’s preferences are unsuccessful, then a shift to discharge planning may be appropriate. A summary of this decision process is outlined in the Figure.

Of note, physicians’ decisions about the appropriateness of patient movement could conflict with the existing institutional procedures or policies (eg, a physician deems increased patient movement to carry minimal risks, while the institution seeks to restrict movement due to concerns about liability). For this reason, it is important for clinicians to participate in the development of institutional policy to ensure that it reflects the clinical and ethical considerations that clinicians apply to patient care. A policy designed with input from relevant stakeholders across the institution including legal, nursing, physicians, administration, ethics, risk management, and patient advocates can provide expert guidance that is based on and consistent with the institution’s mission, values, and priorities.20

ENHANCING SAFE MOVEMENT

In mitigating the burdens of restriction on movement, hospitals may implement a range of options that address patients’ preferences while maintaining safety. Given the potential consequences of liberalized patient movement, it may be prudent to implement these safeguards as a compromise that addresses both the patients’ needs and the hospital’s concerns. These could include an escort for off-floor supervision, timed passes to leave the floor, or volunteers purchasing food for patients from the cafeteria. Creating open, supervised spaces within the hospital (eg, lounges) may also help provide the respite patients need, but in a safe and medically structured environment.

CONCLUSION

Returning to the introductory case example, we now present an alternative outcome in the context of the practices described above. On the morning of the scheduled TEE, a nurse noted that the patient was missing from his room. Before the staff began searching for the patient, they consulted the medical record which included the admission discussion and agreement to expectations for inpatient movement. The record also included an informed consent discussion indicating the minimal risks of leaving the floor, as the patient could ambulate independently and had no need for continuous monitoring. Finally, a physician’s order authorized the patient to be off the floor until 10

The above scenario highlights the benefits of a comprehensive framework for patient movement practices that are transparent, fair, and systematic. Explicitly recognizing competing institutional and patient perspectives can prevent conflict and promote high-quality, safe, efficient, patient-centered care that only restricts the patient’s movement under specified and justifiable conditions. In developing strong hospital practices, institutions should refer to the relevant clinical and ethical standards and draw upon their institutional resources in risk management, clinical staff, and patient advocates.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Neil Shapiro and Dr. David Chuquin for their constructive reviews of prior versions of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the US Government, or the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

1. Smith T. Wandering off the floors: safety and security risks of patient wandering. PSNet Patient Safety Network. Web M&M 2014. Accessed December 4, 2017.

2. Douglas CH, Douglas MR. Patient-friendly hospital environments: exploring the patients’ perspective. Health Expect. 2004;7(1):61-73. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00251.x.

3. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3695

4. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1556.

5. Oliver D, Killick S, Even T, Willmott M. Do falls and falls-injuries in hospital indicate negligent care-and how big is the risk? A retrospective analysis of the NHS Litigation Authority Database of clinical negligence claims, resulting from falls in hospitals in England 1995 to 2006. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(6):431-436. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.024703.

6. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0807.

7. Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

8. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

9. Halfon P, Eggli Y, Van Melle G, Vagnair A. Risk of falls for hospitalized patients: a predictive model based on routinely available data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(12):1258-1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00406-1

10. Rowe M. Wandering in hospitalized older adults: identifying risk is the first step in this approach to preventing wandering in patients with dementia. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(10):62-70. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336968.32462.c9.

11. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Health care infection control practices advisory C. 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(10 Suppl 2):S65-S164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007

12. Ito Y, Nagao M, Iinuma Y, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial tuberculosis transmission among health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(5):596-598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.11.022.

13. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):e56-e93. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq147

14. Martin EM, Russell D, Rubin Z, et al. Elimination of routine contact precautions for endemic methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus: a retrospective quasi-experimental study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1323-1330. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2016.156

15. Morgan DJ, Murthy R, Munoz-Price LS, et al. Reconsidering contact precautions for endemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(10):1163-1172. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.156.

16. Fatkenheuer G, Hirschel B, Harbarth S. Screening and isolation to control meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: sense, nonsense, and evidence. Lancet. 2015;385(9973):1146-1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60660-7.

17. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018.

18. Handel DA, Fu R, Daya M, York J, Larson E, John McConnell K. The use of scripting at triage and its impact on elopements. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):495-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00721.x.

19. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making-pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780-781. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1109283.

20. Donn SM. Medical liability, risk management, and the quality of health care. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;10(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2004.09.004.

A 58-year-old man with a remote history of endocarditis and no prior injection drug use was admitted to the inpatient medicine service with fever and concern for recurrent endocarditis. A transthoracic echocardiogram was unremarkable and the patient remained clinically stable. A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was scheduled for the following morning, but during nursing rounds, the patient was missing from his room. Multiple staff members searched for the patient and eventually located him in the hospital lobby drinking a cup of coffee purchased from the cafeteria. Despite his opposition, he was escorted back to his room and advised to not leave the floor again. Later that day, the patient became frustrated and left the hospital before his scheduled TEE. He was subsequently lost to follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Patients are admitted to the hospital based upon a medical determination that the patient requires acute observation, evaluation, or treatment. Once admitted, healthcare providers may impose restrictions on the patient’s movement in the hospital, such as restrictions on leaving their assigned floor. Managing the movement of hospitalized patients poses significant challenges for the clinical staff because of the difficulty of providing a treatment environment that ensures safe and efficient delivery of care while promoting patients’ preferences for an unrestrictive environment that respects their independence.1,2 Broad limits may make it easier for staff to care for patients and reduce concerns about liability, but they may also frustrate patients who may be medically, psychiatrically, and physically stable and do not require stringent monitoring (eg, completing a course of intravenous antibiotics or awaiting placement at outside facilities).

Although this issue has broad implications for patient safety and hospital liability, authoritative guidance and evidence-based literature are lacking. Without clear guidelines, healthcare staff members are likely to spend more time in managing each individual request to leave the floor because they do not have a systematic strategy for making fair and consistent decisions. Here, we describe the patient and institutional considerations when managing patient movement in the hospital. We refer to “patient movement” specifically as a patient’s choice to move to different locations within the hospital, but outside of their assigned room and/or floor. This does not include scheduled, supervised ambulation activities, such as physical therapy.

POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES OF LIBERALIZING AND RESTRICTING INPATIENT MOVEMENT

Practices that promote patient movement offer significant benefits and risks. Enhancing movement is likely to reduce the “physiologic disruption”3 of hospitalization while improving patients’ overall satisfaction and alignment with patient-centered care. Liberalized movement also promotes independence and ambulation that reduces the rate of physical deconditioning.4

Despite theoretical benefits, hospitals may be more concerned about adverse events related to patient movement, such as falls, the use of illicit substances, or elopement. Given that hospitals may be legally5 and financially responsible6 for adverse events associated with patient movement, allowances for off-floor movement should be carefully considered with input from risk management, physicians, nursing leadership, patient advocates, and hospital administration.

Additionally, unannounced movement off the floor may interfere with timely and efficient care by causing lapses in monitoring, such as cardiac telemetry,7 medication administration, and scheduled diagnostic tests. In these situations, the risks of patient absence from the floor are significant and may ultimately negate the benefits of continued hospitalization by compromising the central elements of patient care.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Patients’ requests to leave the hospital floor should be evaluated systemically and transparently to promote fair, high-value care. First, a request for liberalized movement should prompt physicians that the patient may no longer require hospitalization and may be ready for the transition to outpatient care.8 If the patient still requires inpatient care, then the medical practitioner should make a clinical determination if the patient is medically stable enough to leave their hospital floor. The provider should first identify when the liberalization of movement would be universally inappropriate, such as in patients who are physically unable to ambulate without posing significant harm to themselves. This includes an accidental fall (usually while walking5), which is one of the most commonly reported adverse events in an inpatient setting.9 Additionally, patients with significant cognitive impairments or those lacking in decision-making capacity may be restricted from leaving their floors unescorted, as they are at a higher risk of disorientation, falls, and death.10

In determining movement restrictions for patients in isolation, hospitals should refer to the existing guidelines on isolation precautions for the transmission of communicable infections11,12 and neutropenic precautions.13 Additionally, movement restriction for patients who are isolated after screening positive for certain drug-resistant organisms (eg, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci) is controversial and should be evaluated based on the available medical evidence and standards.14-16

When making a risk-benefit determination about movement, providers should also assess the intent and the potentially unmet needs behind the patient’s request. Patient-centered reasons for enhanced freedom of movement within the hospital include a desire for exercise, greater food choice, and visiting with loved ones, all of which can enable patients to manage the well-known inconveniences and stresses of hospitalization. In contrast, there may be concerns for other intentions behind leaving assigned floors based on the patient’s clinical history, such as the surreptitious use of illicit substances or attempts to elope from the hospital. Advising restriction of movement is justifiable if there is a significant concern for behavior that undermines the safe delivery of care. In patients with active substance use disorders, the appropriate treatment of pain or withdrawal symptoms may better address the patients’ unmet needs, but a lower threshold to restrict movement may be reasonable given the significant risks involved. However, given the widespread stigmatization of patients with substance use disorders,17 institutional policy and clinicians should adhere to systematic, transparent, and consistent risk assessments for all patients in order to minimize the potential for introducing or exacerbating disparities in care.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

In order to work productively with admitted patients, strong practices honor patients’ autonomy by specifying

Patients may request or even demand to leave the floor after a healthcare provider has determined that doing so would be unsafe and/or undermine the timely and efficient delivery of care. In these cases, shared decision-making (SDM) can help identify acceptable solutions within the identified constraints. SDM combines the physicians’ experience, expertise, and knowledge of medical evidence with patients’ values, needs, and preferences for care.19 If patients continue to request to leave the floor after the restriction has been communicated, physicians should discuss whether the current treatment plan should be renegotiated to include a relatively minor modification (eg, a change in the timing or route of administration of medication). If inpatient care cannot be provided safely within the patient’s preferences for movement and attempts to accommodate the patient’s preferences are unsuccessful, then a shift to discharge planning may be appropriate. A summary of this decision process is outlined in the Figure.

Of note, physicians’ decisions about the appropriateness of patient movement could conflict with the existing institutional procedures or policies (eg, a physician deems increased patient movement to carry minimal risks, while the institution seeks to restrict movement due to concerns about liability). For this reason, it is important for clinicians to participate in the development of institutional policy to ensure that it reflects the clinical and ethical considerations that clinicians apply to patient care. A policy designed with input from relevant stakeholders across the institution including legal, nursing, physicians, administration, ethics, risk management, and patient advocates can provide expert guidance that is based on and consistent with the institution’s mission, values, and priorities.20

ENHANCING SAFE MOVEMENT

In mitigating the burdens of restriction on movement, hospitals may implement a range of options that address patients’ preferences while maintaining safety. Given the potential consequences of liberalized patient movement, it may be prudent to implement these safeguards as a compromise that addresses both the patients’ needs and the hospital’s concerns. These could include an escort for off-floor supervision, timed passes to leave the floor, or volunteers purchasing food for patients from the cafeteria. Creating open, supervised spaces within the hospital (eg, lounges) may also help provide the respite patients need, but in a safe and medically structured environment.

CONCLUSION

Returning to the introductory case example, we now present an alternative outcome in the context of the practices described above. On the morning of the scheduled TEE, a nurse noted that the patient was missing from his room. Before the staff began searching for the patient, they consulted the medical record which included the admission discussion and agreement to expectations for inpatient movement. The record also included an informed consent discussion indicating the minimal risks of leaving the floor, as the patient could ambulate independently and had no need for continuous monitoring. Finally, a physician’s order authorized the patient to be off the floor until 10

The above scenario highlights the benefits of a comprehensive framework for patient movement practices that are transparent, fair, and systematic. Explicitly recognizing competing institutional and patient perspectives can prevent conflict and promote high-quality, safe, efficient, patient-centered care that only restricts the patient’s movement under specified and justifiable conditions. In developing strong hospital practices, institutions should refer to the relevant clinical and ethical standards and draw upon their institutional resources in risk management, clinical staff, and patient advocates.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Neil Shapiro and Dr. David Chuquin for their constructive reviews of prior versions of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the US Government, or the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

A 58-year-old man with a remote history of endocarditis and no prior injection drug use was admitted to the inpatient medicine service with fever and concern for recurrent endocarditis. A transthoracic echocardiogram was unremarkable and the patient remained clinically stable. A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was scheduled for the following morning, but during nursing rounds, the patient was missing from his room. Multiple staff members searched for the patient and eventually located him in the hospital lobby drinking a cup of coffee purchased from the cafeteria. Despite his opposition, he was escorted back to his room and advised to not leave the floor again. Later that day, the patient became frustrated and left the hospital before his scheduled TEE. He was subsequently lost to follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Patients are admitted to the hospital based upon a medical determination that the patient requires acute observation, evaluation, or treatment. Once admitted, healthcare providers may impose restrictions on the patient’s movement in the hospital, such as restrictions on leaving their assigned floor. Managing the movement of hospitalized patients poses significant challenges for the clinical staff because of the difficulty of providing a treatment environment that ensures safe and efficient delivery of care while promoting patients’ preferences for an unrestrictive environment that respects their independence.1,2 Broad limits may make it easier for staff to care for patients and reduce concerns about liability, but they may also frustrate patients who may be medically, psychiatrically, and physically stable and do not require stringent monitoring (eg, completing a course of intravenous antibiotics or awaiting placement at outside facilities).

Although this issue has broad implications for patient safety and hospital liability, authoritative guidance and evidence-based literature are lacking. Without clear guidelines, healthcare staff members are likely to spend more time in managing each individual request to leave the floor because they do not have a systematic strategy for making fair and consistent decisions. Here, we describe the patient and institutional considerations when managing patient movement in the hospital. We refer to “patient movement” specifically as a patient’s choice to move to different locations within the hospital, but outside of their assigned room and/or floor. This does not include scheduled, supervised ambulation activities, such as physical therapy.

POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES OF LIBERALIZING AND RESTRICTING INPATIENT MOVEMENT

Practices that promote patient movement offer significant benefits and risks. Enhancing movement is likely to reduce the “physiologic disruption”3 of hospitalization while improving patients’ overall satisfaction and alignment with patient-centered care. Liberalized movement also promotes independence and ambulation that reduces the rate of physical deconditioning.4

Despite theoretical benefits, hospitals may be more concerned about adverse events related to patient movement, such as falls, the use of illicit substances, or elopement. Given that hospitals may be legally5 and financially responsible6 for adverse events associated with patient movement, allowances for off-floor movement should be carefully considered with input from risk management, physicians, nursing leadership, patient advocates, and hospital administration.

Additionally, unannounced movement off the floor may interfere with timely and efficient care by causing lapses in monitoring, such as cardiac telemetry,7 medication administration, and scheduled diagnostic tests. In these situations, the risks of patient absence from the floor are significant and may ultimately negate the benefits of continued hospitalization by compromising the central elements of patient care.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Patients’ requests to leave the hospital floor should be evaluated systemically and transparently to promote fair, high-value care. First, a request for liberalized movement should prompt physicians that the patient may no longer require hospitalization and may be ready for the transition to outpatient care.8 If the patient still requires inpatient care, then the medical practitioner should make a clinical determination if the patient is medically stable enough to leave their hospital floor. The provider should first identify when the liberalization of movement would be universally inappropriate, such as in patients who are physically unable to ambulate without posing significant harm to themselves. This includes an accidental fall (usually while walking5), which is one of the most commonly reported adverse events in an inpatient setting.9 Additionally, patients with significant cognitive impairments or those lacking in decision-making capacity may be restricted from leaving their floors unescorted, as they are at a higher risk of disorientation, falls, and death.10

In determining movement restrictions for patients in isolation, hospitals should refer to the existing guidelines on isolation precautions for the transmission of communicable infections11,12 and neutropenic precautions.13 Additionally, movement restriction for patients who are isolated after screening positive for certain drug-resistant organisms (eg, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci) is controversial and should be evaluated based on the available medical evidence and standards.14-16

When making a risk-benefit determination about movement, providers should also assess the intent and the potentially unmet needs behind the patient’s request. Patient-centered reasons for enhanced freedom of movement within the hospital include a desire for exercise, greater food choice, and visiting with loved ones, all of which can enable patients to manage the well-known inconveniences and stresses of hospitalization. In contrast, there may be concerns for other intentions behind leaving assigned floors based on the patient’s clinical history, such as the surreptitious use of illicit substances or attempts to elope from the hospital. Advising restriction of movement is justifiable if there is a significant concern for behavior that undermines the safe delivery of care. In patients with active substance use disorders, the appropriate treatment of pain or withdrawal symptoms may better address the patients’ unmet needs, but a lower threshold to restrict movement may be reasonable given the significant risks involved. However, given the widespread stigmatization of patients with substance use disorders,17 institutional policy and clinicians should adhere to systematic, transparent, and consistent risk assessments for all patients in order to minimize the potential for introducing or exacerbating disparities in care.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

In order to work productively with admitted patients, strong practices honor patients’ autonomy by specifying

Patients may request or even demand to leave the floor after a healthcare provider has determined that doing so would be unsafe and/or undermine the timely and efficient delivery of care. In these cases, shared decision-making (SDM) can help identify acceptable solutions within the identified constraints. SDM combines the physicians’ experience, expertise, and knowledge of medical evidence with patients’ values, needs, and preferences for care.19 If patients continue to request to leave the floor after the restriction has been communicated, physicians should discuss whether the current treatment plan should be renegotiated to include a relatively minor modification (eg, a change in the timing or route of administration of medication). If inpatient care cannot be provided safely within the patient’s preferences for movement and attempts to accommodate the patient’s preferences are unsuccessful, then a shift to discharge planning may be appropriate. A summary of this decision process is outlined in the Figure.

Of note, physicians’ decisions about the appropriateness of patient movement could conflict with the existing institutional procedures or policies (eg, a physician deems increased patient movement to carry minimal risks, while the institution seeks to restrict movement due to concerns about liability). For this reason, it is important for clinicians to participate in the development of institutional policy to ensure that it reflects the clinical and ethical considerations that clinicians apply to patient care. A policy designed with input from relevant stakeholders across the institution including legal, nursing, physicians, administration, ethics, risk management, and patient advocates can provide expert guidance that is based on and consistent with the institution’s mission, values, and priorities.20

ENHANCING SAFE MOVEMENT

In mitigating the burdens of restriction on movement, hospitals may implement a range of options that address patients’ preferences while maintaining safety. Given the potential consequences of liberalized patient movement, it may be prudent to implement these safeguards as a compromise that addresses both the patients’ needs and the hospital’s concerns. These could include an escort for off-floor supervision, timed passes to leave the floor, or volunteers purchasing food for patients from the cafeteria. Creating open, supervised spaces within the hospital (eg, lounges) may also help provide the respite patients need, but in a safe and medically structured environment.

CONCLUSION

Returning to the introductory case example, we now present an alternative outcome in the context of the practices described above. On the morning of the scheduled TEE, a nurse noted that the patient was missing from his room. Before the staff began searching for the patient, they consulted the medical record which included the admission discussion and agreement to expectations for inpatient movement. The record also included an informed consent discussion indicating the minimal risks of leaving the floor, as the patient could ambulate independently and had no need for continuous monitoring. Finally, a physician’s order authorized the patient to be off the floor until 10

The above scenario highlights the benefits of a comprehensive framework for patient movement practices that are transparent, fair, and systematic. Explicitly recognizing competing institutional and patient perspectives can prevent conflict and promote high-quality, safe, efficient, patient-centered care that only restricts the patient’s movement under specified and justifiable conditions. In developing strong hospital practices, institutions should refer to the relevant clinical and ethical standards and draw upon their institutional resources in risk management, clinical staff, and patient advocates.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Neil Shapiro and Dr. David Chuquin for their constructive reviews of prior versions of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the US Government, or the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

1. Smith T. Wandering off the floors: safety and security risks of patient wandering. PSNet Patient Safety Network. Web M&M 2014. Accessed December 4, 2017.

2. Douglas CH, Douglas MR. Patient-friendly hospital environments: exploring the patients’ perspective. Health Expect. 2004;7(1):61-73. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00251.x.

3. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3695

4. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1556.

5. Oliver D, Killick S, Even T, Willmott M. Do falls and falls-injuries in hospital indicate negligent care-and how big is the risk? A retrospective analysis of the NHS Litigation Authority Database of clinical negligence claims, resulting from falls in hospitals in England 1995 to 2006. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(6):431-436. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.024703.

6. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0807.

7. Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

8. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

9. Halfon P, Eggli Y, Van Melle G, Vagnair A. Risk of falls for hospitalized patients: a predictive model based on routinely available data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(12):1258-1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00406-1

10. Rowe M. Wandering in hospitalized older adults: identifying risk is the first step in this approach to preventing wandering in patients with dementia. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(10):62-70. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336968.32462.c9.

11. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Health care infection control practices advisory C. 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(10 Suppl 2):S65-S164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007

12. Ito Y, Nagao M, Iinuma Y, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial tuberculosis transmission among health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(5):596-598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.11.022.

13. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):e56-e93. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq147

14. Martin EM, Russell D, Rubin Z, et al. Elimination of routine contact precautions for endemic methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus: a retrospective quasi-experimental study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1323-1330. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2016.156

15. Morgan DJ, Murthy R, Munoz-Price LS, et al. Reconsidering contact precautions for endemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(10):1163-1172. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.156.

16. Fatkenheuer G, Hirschel B, Harbarth S. Screening and isolation to control meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: sense, nonsense, and evidence. Lancet. 2015;385(9973):1146-1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60660-7.

17. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018.

18. Handel DA, Fu R, Daya M, York J, Larson E, John McConnell K. The use of scripting at triage and its impact on elopements. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):495-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00721.x.

19. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making-pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780-781. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1109283.

20. Donn SM. Medical liability, risk management, and the quality of health care. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;10(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2004.09.004.

1. Smith T. Wandering off the floors: safety and security risks of patient wandering. PSNet Patient Safety Network. Web M&M 2014. Accessed December 4, 2017.

2. Douglas CH, Douglas MR. Patient-friendly hospital environments: exploring the patients’ perspective. Health Expect. 2004;7(1):61-73. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00251.x.

3. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3695

4. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1556.

5. Oliver D, Killick S, Even T, Willmott M. Do falls and falls-injuries in hospital indicate negligent care-and how big is the risk? A retrospective analysis of the NHS Litigation Authority Database of clinical negligence claims, resulting from falls in hospitals in England 1995 to 2006. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(6):431-436. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.024703.

6. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0807.

7. Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

8. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

9. Halfon P, Eggli Y, Van Melle G, Vagnair A. Risk of falls for hospitalized patients: a predictive model based on routinely available data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(12):1258-1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00406-1

10. Rowe M. Wandering in hospitalized older adults: identifying risk is the first step in this approach to preventing wandering in patients with dementia. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(10):62-70. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336968.32462.c9.

11. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Health care infection control practices advisory C. 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(10 Suppl 2):S65-S164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007

12. Ito Y, Nagao M, Iinuma Y, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial tuberculosis transmission among health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(5):596-598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.11.022.

13. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):e56-e93. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq147

14. Martin EM, Russell D, Rubin Z, et al. Elimination of routine contact precautions for endemic methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus: a retrospective quasi-experimental study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1323-1330. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2016.156

15. Morgan DJ, Murthy R, Munoz-Price LS, et al. Reconsidering contact precautions for endemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(10):1163-1172. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.156.

16. Fatkenheuer G, Hirschel B, Harbarth S. Screening and isolation to control meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: sense, nonsense, and evidence. Lancet. 2015;385(9973):1146-1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60660-7.

17. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018.

18. Handel DA, Fu R, Daya M, York J, Larson E, John McConnell K. The use of scripting at triage and its impact on elopements. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):495-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00721.x.

19. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making-pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780-781. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1109283.

20. Donn SM. Medical liability, risk management, and the quality of health care. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;10(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2004.09.004.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Ethical Considerations in the Care of Hospitalized Patients with Opioid Use and Injection Drug Use Disorders

“Lord have mercy on me, was the kneeling drunkard’s plea.”

—Johnny Cash

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association defines opioid-use disorder (OUD) as a problematic pattern of prescription and/or illicit opioid medication use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress.1 Compared with their non-OUD counterparts, patients with OUD have poorer overall health and worse health service outcomes, including higher rates of morbidity, mortality, HIV and HCV transmission, and 30-day readmissions.2 With the rate of fatal overdoses from opioids at crisis levels, leading scientific and professional organizations have declared OUD to be a public health emergency in the United States.3

The opioid epidemic affects hospitalists through the rising incidence of hospitalization, not only as a result of OUD’s indirect complications, but also its direct effects of intoxication and withdrawal.4 In caring for patients with OUD, hospitalists are often presented with many ethical dilemmas. Whether the dilemma involves timing and circumstances of discharge or the permission to leave the hospital floor, they often involve elements of mutual mistrust. In qualitative ethnographic studies, patients with OUD report not trusting that the medical staff will take their concerns of inadequately treated pain and other needs seriously. Providers may mistrust the patient’s report of pain and withhold treatment for OUD for nonclinical reasons.5 Here, we examine two ethical dilemmas specific to OUD in hospitalized patients. Our aim in describing these dilemmas is to help hospitalists recognize that targeting issues of mistrust may assist them to deliver better care to hospitalized patients with OUD.

DISCHARGING HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS WITH OUD

In the inpatient setting, ethical dilemmas surrounding discharge are common among people who inject drugs (PWID). These patients have disproportionately high rates of soft tissue and systemic infections, such as endocarditis and osteomyelitis, and subsequently often require long-term, outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT).6 From both the clinical and ethical perspectives, discharging PWID requiring OPAT to an unsupervised setting or continuing inpatient hospitalization to prevent a potential adverse event are equally imperfect solutions.

These patients may be clinically stable, suitable for discharge, and prefer to be discharged, but the practitioner’s concerns regarding untoward complications frequently override the patient’s wishes. Valid reasons for this exercise of what could be considered soft-paternalism are considered when physicians unilaterally decide what is best for patients, including refusal of community agencies to provide OPAT to PWID, inadequate social support and/or health literacy to administer the therapy, or varying degrees of homelessness that can affect timely follow-up. However, surveys of both hospitalists and infectious disease specialists also indicate that they may avoid discharge because of concerns the PWID will tamper with the intravenous (IV) catheter to inject drugs.7 This reluctance to discharge otherwise socially and medically suitable patients increases length of stay,7 decreases patient satisfaction, and could lead to misuse of limited hospital resources.

Both patient mistrust and stigmatization may contribute to this dilemma. Healthcare professionals have been shown to share and reflect a long-standing bias in their attitudes toward patients with substance-use disorders and OUD, in particular.8 Studies of providers’ attitudes are limited but suggest that legal concerns over liability and professional sanctions,9 reluctance to contribute to the development or relapse of addiction,10 and a strong psychological investment in not being deceived by the patient11 may influence physicians’ decisions about care.

Closely supervising IV antibiotic therapy for all PWID may not reflect current medical knowledge and may imply a moral assessment of patients’ culpability and lack of will power to resist using drugs.12 No evidence is available to suggest that inpatient parenteral antibiotic treatment offers superior adherence, and emerging evidence showing that carefully selected patients with an injection drug-use history can be safely and effectively treated as outpatients has been obtained.13,14 Ho et al. found high rates of treatment success in patients with adequate housing, a reliable guardian, and willingness to comply with appropriate IV catheter use.13 Although the study by Buehrle et al. found higher rates of OPAT failure among PWIDs, 25% of these failures were due to adverse drug reactions and only 2% were due to documented line manipulations.14 This research suggests that disposition to alternative settings for OPAT in PWID may be feasible, reasonable, and deserving of further study. Rather than treating PWIDs as a homogenous group of increased risk, contextualizing care based on individual risk stratification promotes more patient-centered care that is medically appropriate and potentially more cost efficient. A

Patient-centered approaches that respond to the individual needs of patients have altered the care delivery model in order to improve health services outcomes. In developing an alternative care model to inpatient treatment in PWID who required OPAT, Jafari et al.15 evaluated a community model of care that provided a home-like residence as an alternative to hospitalization where patients could receive OPAT in a medically and socially supportive environment. This environment, which included RN and mental health staff for substance-use counseling, wound care, medication management, and IV therapy, demonstrated lower rates of against medical advice (AMA) discharge and higher patient satisfaction compared with hospitalization.15

MOBILITY OFF OF THE HOSPITAL FLOOR FOR HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS WITH OUD

Ethical dilemmas may also arise when patients with OUD desire greater mobility in the hospital. Although some inpatients may be permitted to leave the floor, some treatment teams may believe that patients with OUD leave the floor to use drugs and that the patient’s IV will facilitate such behavior. Nursing and medical staff may also believe that, if they agree to a request to leave the floor, they are complicit in any potential drug use or harmful consequences resulting from this use. For their part, patients may have a desire for more mobility because of the sometimes unpleasant constraints of hospitalization, which are not unique to these patients16 or to distract them from their cravings. Patients, unable to tolerate the restriction emotionally or believing they are being treated unfairly, even punitively, may leave AMA rather than complete needed medical care. Once more, distrust of the patient and fear of liability may lead hospital staff to respond in counterproductive ways.

Addressing this dilemma depends, in part on creating an environment where PWID and patients with OUD are treated fairly and appropriately for their underlying illness. Such treatment includes ensuring withdrawal symptoms and pain are adequately treated, building trust by empathically addressing patients’ needs and preferences,17 and having a systematic (ie, policy-based) approach for requests to leave the floor. Th

Efforts to adequately treat withdrawal symptoms in the hospital setting have shown promise in maintaining patient engagement, reducing the rate of AMA discharges, and improving follow up with outpatient medical and substance-use treatment.18 Because physicians consistently cite the lack of advanced training in addiction medicine as a treatment limitation,12 training may go a long way in closing this knowledge and skill gap. Furthermore, systematic efforts to better educate and train hospitalists in the care of patients with addiction can improve both knowledge and attitudes about caring for this vulnerable population,19 thereby enhancing therapeutic relationships and patient centeredness. Finally, institutional policies promoting fair, systematic, and transparent guidance are needed for front-line practitioners to manage the legal, clinical, and ethical ambiguities involved when PWID wish to leave the hospital floor.

ENHANCING CARE DELIVERY TO PATIENTS WITH OUD

In addressing the mistrust some staff may have toward the patients described in the preceding ethical dilemmas, the use of universal precautions is an ethical and efficacious approach that balances reliance on patients’ veracity with due diligence in objective clinical assessments.20 These universal precautions, which are grounded in mutual respect and responsibility between physician and patient, include a set of strategies originally established in infectious disease practice and adapted to the management of chronic pain particularly when opioids are used.21 They are based on the recognition that identifying which patients prescribed opioids will develop an OUD or misuse opioids is difficult. Hence, the safest and least-stigmatizing approach is to treat all patients as individuals who could potentially be at risk. This is an ethically strong approach that seeks to balance the competing values of patent safety and patient centeredness, and involves taking a substance-use history from all patients admitted to the hospital and routinely checking state prescription-drug monitoring programs among other steps. Although self-reporting, at least of prescription-drug misuse, is fairly reliable,22 establishing expectations for mutual respect when working with patients with OUD and other addictive disorders is more likely to garner valid reports and a positive alliance. Once this relationship is established, the practitioner can respond to problematic behaviors with clear, compassionate limit setting.

From a broader perspective, a hospital system and culture that is unable to promote trust and adequately treat pain and withdrawal can create a “risk environment” for PWID.23 When providers are inadequately trained in the management of pain and addiction, or there is a shortage of addiction specialists, or inadequate policy guidance for managing the care of these patients, this can result in AMA discharges and reduced willingness to seek future care. Viewing this problem more expansively may persuade healthcare professionals that patients alone are not entirely responsible for the outcomes related to their illness but that modifying practices and structure at the hospital level has the potential to mitigate harm to this vulnerable population.

As inpatient team leaders, hospitalists have the unique opportunity to address the opioid crisis by enhancing the quality of care provided to hospitalized patients with OUD. This enhancement can be accomplished by destigmatizing substance-use disorders, establishing relationships of trust, and promoting remedies to structural deficiencies in the healthcare system that contribute to the problem. These approaches have the potential to enhance not only the care of patients with OUD but also the satisfaction of the treatment team caring for these patients.24 Su

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose, financial or otherwise. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Government, or the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

1. Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(8):834-851. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. PubMed

2. Donroe JH, Holt SR, Tetrault JM. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder in the hospital. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):1232-1239. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160290. PubMed

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Opioid Overdose Crisis 2018. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis. Last updated March 2018. Accessed July 1, 2018.

4. Kerr T, Wood E, Grafstein E, et al. High rates of primary care and emergency department use among injection drug users in Vancouver. J Public Health. (Oxf). 2005;27(1):62-66. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdh189. PubMed

5. Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, Marlatt GA, Bradley KA. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):327-333. doi:10.1007/s11606-002-0034-5. PubMed

6. DP Levine PB. Infections in Injection Drug Users. In: Mandell GL BJ, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

7. Fanucchi L, Leedy N, Li J, Thornton AC. Perceptions and practices of physicians regarding outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy in persons who inject drugs. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):581-582. doi:10.1002/jhm.2582. PubMed

8. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018. PubMed

9. Fishman SM. Risk of the view through the keyhole: there is much more to physician reactions to the DEA than the number of formal actions. Pain Med. 2006;7(4):360-362; discussion 365-366. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00194.x. PubMed

10. Jamison RN, Sheehan KA, Scanlan E, Matthews M, Ross EL. Beliefs and attitudes about opioid prescribing and chronic pain management: survey of primary care providers. J Opioid Manag. 2014;10(6):375-382. doi:10.5055/jom.2014.0234. PubMed

11. Beach SR, Taylor JB, Kontos N. Teaching psychiatric trainees to “think dirty”: uncovering hidden motivations and deception. Psychosomatics. 2017;58(5):474-482. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2017.04.005. PubMed

12. Wakeman SE, Pham-Kanter G, Donelan K. Attitudes, practices, and preparedness to care for patients with substance use disorder: results from a survey of general internists. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):635-641. doi:10.1080/08897077.2016.1187240. PubMed

13. Ho J, Archuleta S, Sulaiman Z, Fisher D. Safe and successful treatment of intravenous drug users with a peripherally inserted central catheter in an outpatient parenteral antibiotic treatment service. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(12):2641-2644. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq355. PubMed

14. Buehrle DJ, Shields RK, Shah N, Shoff C, Sheridan K. Risk factors associated with outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy program failure among intravenous drug users. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(3):ofx102. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofx102. PubMed

15. Jafari S, Joe R, Elliot D, Nagji A, Hayden S, Marsh DC. A community care model of intravenous antibiotic therapy for injection drug users with deep tissue infection for “reduce leaving against medical advice.” Int J Ment Health Addict. 2015;13:49-58. doi:10.1007/s11469-014-9511-4. PubMed

16. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3695. PubMed

17. Joosten EA, De Jong CA, de Weert-van Oene GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP. Shared decision-making: increases autonomy in substance-dependent patients. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(8):1037-1038. doi:10.3109/10826084.2011.552931. PubMed

18. Chan AC, Palepu A, Guh DP, et al. HIV-positive injection drug users who leave the hospital against medical advice: the mitigating role of methadone and social support. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(1):56-59. doi:10.1097/00126334-200401010-00008. PubMed

19. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11) 752-758. doi:10.12788/jhm.2993. PubMed

20. Kaye AD, Jones MR, Kaye AM, et al. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: an updated review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse (part 2). Pain Physician. 2017;20(2S):S111-S133. PubMed

21. Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Almahrezi A. Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6(2):107-112. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05031.x. PubMed

22. Smith M, Rosenblum A, Parrino M, Fong C, Colucci S. Validity of self-reported misuse of prescription opioid analgesics. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(10):1509-1524. doi:10.3109/10826081003682107. PubMed

23. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a ‘risk environment’: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010. PubMed

24. Sullivan MD, Leigh J, Gaster B. Brief report: Training internists in shared decision making about chronic opioid treatment for noncancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(4):360-362. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00352.x. PubMed

“Lord have mercy on me, was the kneeling drunkard’s plea.”

—Johnny Cash

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association defines opioid-use disorder (OUD) as a problematic pattern of prescription and/or illicit opioid medication use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress.1 Compared with their non-OUD counterparts, patients with OUD have poorer overall health and worse health service outcomes, including higher rates of morbidity, mortality, HIV and HCV transmission, and 30-day readmissions.2 With the rate of fatal overdoses from opioids at crisis levels, leading scientific and professional organizations have declared OUD to be a public health emergency in the United States.3

The opioid epidemic affects hospitalists through the rising incidence of hospitalization, not only as a result of OUD’s indirect complications, but also its direct effects of intoxication and withdrawal.4 In caring for patients with OUD, hospitalists are often presented with many ethical dilemmas. Whether the dilemma involves timing and circumstances of discharge or the permission to leave the hospital floor, they often involve elements of mutual mistrust. In qualitative ethnographic studies, patients with OUD report not trusting that the medical staff will take their concerns of inadequately treated pain and other needs seriously. Providers may mistrust the patient’s report of pain and withhold treatment for OUD for nonclinical reasons.5 Here, we examine two ethical dilemmas specific to OUD in hospitalized patients. Our aim in describing these dilemmas is to help hospitalists recognize that targeting issues of mistrust may assist them to deliver better care to hospitalized patients with OUD.

DISCHARGING HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS WITH OUD

In the inpatient setting, ethical dilemmas surrounding discharge are common among people who inject drugs (PWID). These patients have disproportionately high rates of soft tissue and systemic infections, such as endocarditis and osteomyelitis, and subsequently often require long-term, outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT).6 From both the clinical and ethical perspectives, discharging PWID requiring OPAT to an unsupervised setting or continuing inpatient hospitalization to prevent a potential adverse event are equally imperfect solutions.

These patients may be clinically stable, suitable for discharge, and prefer to be discharged, but the practitioner’s concerns regarding untoward complications frequently override the patient’s wishes. Valid reasons for this exercise of what could be considered soft-paternalism are considered when physicians unilaterally decide what is best for patients, including refusal of community agencies to provide OPAT to PWID, inadequate social support and/or health literacy to administer the therapy, or varying degrees of homelessness that can affect timely follow-up. However, surveys of both hospitalists and infectious disease specialists also indicate that they may avoid discharge because of concerns the PWID will tamper with the intravenous (IV) catheter to inject drugs.7 This reluctance to discharge otherwise socially and medically suitable patients increases length of stay,7 decreases patient satisfaction, and could lead to misuse of limited hospital resources.

Both patient mistrust and stigmatization may contribute to this dilemma. Healthcare professionals have been shown to share and reflect a long-standing bias in their attitudes toward patients with substance-use disorders and OUD, in particular.8 Studies of providers’ attitudes are limited but suggest that legal concerns over liability and professional sanctions,9 reluctance to contribute to the development or relapse of addiction,10 and a strong psychological investment in not being deceived by the patient11 may influence physicians’ decisions about care.

Closely supervising IV antibiotic therapy for all PWID may not reflect current medical knowledge and may imply a moral assessment of patients’ culpability and lack of will power to resist using drugs.12 No evidence is available to suggest that inpatient parenteral antibiotic treatment offers superior adherence, and emerging evidence showing that carefully selected patients with an injection drug-use history can be safely and effectively treated as outpatients has been obtained.13,14 Ho et al. found high rates of treatment success in patients with adequate housing, a reliable guardian, and willingness to comply with appropriate IV catheter use.13 Although the study by Buehrle et al. found higher rates of OPAT failure among PWIDs, 25% of these failures were due to adverse drug reactions and only 2% were due to documented line manipulations.14 This research suggests that disposition to alternative settings for OPAT in PWID may be feasible, reasonable, and deserving of further study. Rather than treating PWIDs as a homogenous group of increased risk, contextualizing care based on individual risk stratification promotes more patient-centered care that is medically appropriate and potentially more cost efficient. A

Patient-centered approaches that respond to the individual needs of patients have altered the care delivery model in order to improve health services outcomes. In developing an alternative care model to inpatient treatment in PWID who required OPAT, Jafari et al.15 evaluated a community model of care that provided a home-like residence as an alternative to hospitalization where patients could receive OPAT in a medically and socially supportive environment. This environment, which included RN and mental health staff for substance-use counseling, wound care, medication management, and IV therapy, demonstrated lower rates of against medical advice (AMA) discharge and higher patient satisfaction compared with hospitalization.15

MOBILITY OFF OF THE HOSPITAL FLOOR FOR HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS WITH OUD

Ethical dilemmas may also arise when patients with OUD desire greater mobility in the hospital. Although some inpatients may be permitted to leave the floor, some treatment teams may believe that patients with OUD leave the floor to use drugs and that the patient’s IV will facilitate such behavior. Nursing and medical staff may also believe that, if they agree to a request to leave the floor, they are complicit in any potential drug use or harmful consequences resulting from this use. For their part, patients may have a desire for more mobility because of the sometimes unpleasant constraints of hospitalization, which are not unique to these patients16 or to distract them from their cravings. Patients, unable to tolerate the restriction emotionally or believing they are being treated unfairly, even punitively, may leave AMA rather than complete needed medical care. Once more, distrust of the patient and fear of liability may lead hospital staff to respond in counterproductive ways.

Addressing this dilemma depends, in part on creating an environment where PWID and patients with OUD are treated fairly and appropriately for their underlying illness. Such treatment includes ensuring withdrawal symptoms and pain are adequately treated, building trust by empathically addressing patients’ needs and preferences,17 and having a systematic (ie, policy-based) approach for requests to leave the floor. Th

Efforts to adequately treat withdrawal symptoms in the hospital setting have shown promise in maintaining patient engagement, reducing the rate of AMA discharges, and improving follow up with outpatient medical and substance-use treatment.18 Because physicians consistently cite the lack of advanced training in addiction medicine as a treatment limitation,12 training may go a long way in closing this knowledge and skill gap. Furthermore, systematic efforts to better educate and train hospitalists in the care of patients with addiction can improve both knowledge and attitudes about caring for this vulnerable population,19 thereby enhancing therapeutic relationships and patient centeredness. Finally, institutional policies promoting fair, systematic, and transparent guidance are needed for front-line practitioners to manage the legal, clinical, and ethical ambiguities involved when PWID wish to leave the hospital floor.

ENHANCING CARE DELIVERY TO PATIENTS WITH OUD

In addressing the mistrust some staff may have toward the patients described in the preceding ethical dilemmas, the use of universal precautions is an ethical and efficacious approach that balances reliance on patients’ veracity with due diligence in objective clinical assessments.20 These universal precautions, which are grounded in mutual respect and responsibility between physician and patient, include a set of strategies originally established in infectious disease practice and adapted to the management of chronic pain particularly when opioids are used.21 They are based on the recognition that identifying which patients prescribed opioids will develop an OUD or misuse opioids is difficult. Hence, the safest and least-stigmatizing approach is to treat all patients as individuals who could potentially be at risk. This is an ethically strong approach that seeks to balance the competing values of patent safety and patient centeredness, and involves taking a substance-use history from all patients admitted to the hospital and routinely checking state prescription-drug monitoring programs among other steps. Although self-reporting, at least of prescription-drug misuse, is fairly reliable,22 establishing expectations for mutual respect when working with patients with OUD and other addictive disorders is more likely to garner valid reports and a positive alliance. Once this relationship is established, the practitioner can respond to problematic behaviors with clear, compassionate limit setting.

From a broader perspective, a hospital system and culture that is unable to promote trust and adequately treat pain and withdrawal can create a “risk environment” for PWID.23 When providers are inadequately trained in the management of pain and addiction, or there is a shortage of addiction specialists, or inadequate policy guidance for managing the care of these patients, this can result in AMA discharges and reduced willingness to seek future care. Viewing this problem more expansively may persuade healthcare professionals that patients alone are not entirely responsible for the outcomes related to their illness but that modifying practices and structure at the hospital level has the potential to mitigate harm to this vulnerable population.

As inpatient team leaders, hospitalists have the unique opportunity to address the opioid crisis by enhancing the quality of care provided to hospitalized patients with OUD. This enhancement can be accomplished by destigmatizing substance-use disorders, establishing relationships of trust, and promoting remedies to structural deficiencies in the healthcare system that contribute to the problem. These approaches have the potential to enhance not only the care of patients with OUD but also the satisfaction of the treatment team caring for these patients.24 Su

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose, financial or otherwise. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Government, or the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

“Lord have mercy on me, was the kneeling drunkard’s plea.”

—Johnny Cash

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association defines opioid-use disorder (OUD) as a problematic pattern of prescription and/or illicit opioid medication use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress.1 Compared with their non-OUD counterparts, patients with OUD have poorer overall health and worse health service outcomes, including higher rates of morbidity, mortality, HIV and HCV transmission, and 30-day readmissions.2 With the rate of fatal overdoses from opioids at crisis levels, leading scientific and professional organizations have declared OUD to be a public health emergency in the United States.3

The opioid epidemic affects hospitalists through the rising incidence of hospitalization, not only as a result of OUD’s indirect complications, but also its direct effects of intoxication and withdrawal.4 In caring for patients with OUD, hospitalists are often presented with many ethical dilemmas. Whether the dilemma involves timing and circumstances of discharge or the permission to leave the hospital floor, they often involve elements of mutual mistrust. In qualitative ethnographic studies, patients with OUD report not trusting that the medical staff will take their concerns of inadequately treated pain and other needs seriously. Providers may mistrust the patient’s report of pain and withhold treatment for OUD for nonclinical reasons.5 Here, we examine two ethical dilemmas specific to OUD in hospitalized patients. Our aim in describing these dilemmas is to help hospitalists recognize that targeting issues of mistrust may assist them to deliver better care to hospitalized patients with OUD.

DISCHARGING HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS WITH OUD