User login

Collagen Meniscus Implant

Ivy Sports Medicine (http://www.ivysportsmed.com/en)

Collagen Meniscus Implant

The number of patients undergoing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy has continued to increase. However, this is potentially not a benign procedure, as there are increased contact pressures on the articular cartilage even with the removal of only a segment of the meniscus.

The Collagen Meniscus Implant (CMI, Ivy Sports Medicine) is a resorbable and biocompatible Type I collagen matrix that was developed to restore the segmental loss of meniscal tissue in the knee. It consists of a porous cross-linked matrix scaffold that allows for the ingrowth of the body’s own cells. The CMI is the only meniscal implant composed of purely biological materials and is available in an off-the-shelf supply.

The CMI is available in the United States for use in the restoration of segmental loss of the medial meniscus. The CMI can be utilized in either an acute or chronic situation. In the acute case, it would be indicated when the medial meniscus is irreparable, and that segment must be removed. In the chronic case, the patient would have had a previous partial meniscectomy and/or failed meniscus repair and had developed either pain or signs of early articular cartilage wear in the compartment. The procedure can be done arthroscopically and as an outpatient. The CMI can be kept on the shelf to be available as needed; it has a 2-year shelf life. There are specialized instruments for measuring the length of implant needed and for delivery of the implant.

The CMI has been utilized clinically for 18 years with excellent clinical results. Patients treated with CMI have benefited in over 80% of cases. Studies have demonstrated improved knee function, activity levels, and pain values from the pre- to postoperative periods.1,2 In addition, functional improvements have been maintained for over 10 years. The reoperation rate has been demonstrated to be 10% to 20%, which is comparable to the reoperation rate after meniscal repair.

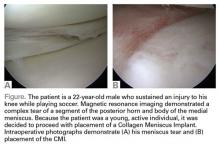

Surgical pearl: The surgical technique for insertion of the CMI is relatively uncomplicated (Figures A, B).

The second step is to measure the length of your meniscus defect with the measuring rod.

Once measured, you want to oversize the implant 10% to 15% (ie, if you measure 30 mm, you will cut at least 34 mm). Use the measuring rod to measure the length of the CMI and mark your length. Use a new scalpel blade to cut the CMI.

Place the measured CMI into the delivery clamp and insert through a mini-arthrotomy into the meniscal defect. The fixation technique of the CMI is entirely up to the implanting surgeon. Most surgeons have used a combination of all-inside and inside-out meniscus repair techniques. It is recommended to start fixing the CMI first posteriorly. The posterior stitch is usually an all-inside horizontal mattress stitch. Coming 1 cm anteriorly, place a vertical mattress stitch. Continue this method sequentially while moving anteriorly. The anterior suture is the surgeon’s choice for device, but it should be a horizontal mattress like the most posterior stitch. It is important while tightening your suture tension to apply the concept of “approximated and not strangulated.” Once completed, close wounds in typical fashion.

1. Zaffagnini S, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Lopomo N, et al. Prospective long-term outcomes of the medial collagen meniscus implant versus partial medial meniscectomy: a minimum 10-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(5):977-985

2. Bulgheroni P, Murena L, Ratti C, Bulgheroni E, Ronga M, Cherubino P. Follow-up of collagen meniscus implant patients: clinical, radiological, and magnetic resonance imaging results at 5 years. Knee. 2010;17(3):224-229.

Ivy Sports Medicine (http://www.ivysportsmed.com/en)

Collagen Meniscus Implant

The number of patients undergoing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy has continued to increase. However, this is potentially not a benign procedure, as there are increased contact pressures on the articular cartilage even with the removal of only a segment of the meniscus.

The Collagen Meniscus Implant (CMI, Ivy Sports Medicine) is a resorbable and biocompatible Type I collagen matrix that was developed to restore the segmental loss of meniscal tissue in the knee. It consists of a porous cross-linked matrix scaffold that allows for the ingrowth of the body’s own cells. The CMI is the only meniscal implant composed of purely biological materials and is available in an off-the-shelf supply.

The CMI is available in the United States for use in the restoration of segmental loss of the medial meniscus. The CMI can be utilized in either an acute or chronic situation. In the acute case, it would be indicated when the medial meniscus is irreparable, and that segment must be removed. In the chronic case, the patient would have had a previous partial meniscectomy and/or failed meniscus repair and had developed either pain or signs of early articular cartilage wear in the compartment. The procedure can be done arthroscopically and as an outpatient. The CMI can be kept on the shelf to be available as needed; it has a 2-year shelf life. There are specialized instruments for measuring the length of implant needed and for delivery of the implant.

The CMI has been utilized clinically for 18 years with excellent clinical results. Patients treated with CMI have benefited in over 80% of cases. Studies have demonstrated improved knee function, activity levels, and pain values from the pre- to postoperative periods.1,2 In addition, functional improvements have been maintained for over 10 years. The reoperation rate has been demonstrated to be 10% to 20%, which is comparable to the reoperation rate after meniscal repair.

Surgical pearl: The surgical technique for insertion of the CMI is relatively uncomplicated (Figures A, B).

The second step is to measure the length of your meniscus defect with the measuring rod.

Once measured, you want to oversize the implant 10% to 15% (ie, if you measure 30 mm, you will cut at least 34 mm). Use the measuring rod to measure the length of the CMI and mark your length. Use a new scalpel blade to cut the CMI.

Place the measured CMI into the delivery clamp and insert through a mini-arthrotomy into the meniscal defect. The fixation technique of the CMI is entirely up to the implanting surgeon. Most surgeons have used a combination of all-inside and inside-out meniscus repair techniques. It is recommended to start fixing the CMI first posteriorly. The posterior stitch is usually an all-inside horizontal mattress stitch. Coming 1 cm anteriorly, place a vertical mattress stitch. Continue this method sequentially while moving anteriorly. The anterior suture is the surgeon’s choice for device, but it should be a horizontal mattress like the most posterior stitch. It is important while tightening your suture tension to apply the concept of “approximated and not strangulated.” Once completed, close wounds in typical fashion.

Ivy Sports Medicine (http://www.ivysportsmed.com/en)

Collagen Meniscus Implant

The number of patients undergoing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy has continued to increase. However, this is potentially not a benign procedure, as there are increased contact pressures on the articular cartilage even with the removal of only a segment of the meniscus.

The Collagen Meniscus Implant (CMI, Ivy Sports Medicine) is a resorbable and biocompatible Type I collagen matrix that was developed to restore the segmental loss of meniscal tissue in the knee. It consists of a porous cross-linked matrix scaffold that allows for the ingrowth of the body’s own cells. The CMI is the only meniscal implant composed of purely biological materials and is available in an off-the-shelf supply.

The CMI is available in the United States for use in the restoration of segmental loss of the medial meniscus. The CMI can be utilized in either an acute or chronic situation. In the acute case, it would be indicated when the medial meniscus is irreparable, and that segment must be removed. In the chronic case, the patient would have had a previous partial meniscectomy and/or failed meniscus repair and had developed either pain or signs of early articular cartilage wear in the compartment. The procedure can be done arthroscopically and as an outpatient. The CMI can be kept on the shelf to be available as needed; it has a 2-year shelf life. There are specialized instruments for measuring the length of implant needed and for delivery of the implant.

The CMI has been utilized clinically for 18 years with excellent clinical results. Patients treated with CMI have benefited in over 80% of cases. Studies have demonstrated improved knee function, activity levels, and pain values from the pre- to postoperative periods.1,2 In addition, functional improvements have been maintained for over 10 years. The reoperation rate has been demonstrated to be 10% to 20%, which is comparable to the reoperation rate after meniscal repair.

Surgical pearl: The surgical technique for insertion of the CMI is relatively uncomplicated (Figures A, B).

The second step is to measure the length of your meniscus defect with the measuring rod.

Once measured, you want to oversize the implant 10% to 15% (ie, if you measure 30 mm, you will cut at least 34 mm). Use the measuring rod to measure the length of the CMI and mark your length. Use a new scalpel blade to cut the CMI.

Place the measured CMI into the delivery clamp and insert through a mini-arthrotomy into the meniscal defect. The fixation technique of the CMI is entirely up to the implanting surgeon. Most surgeons have used a combination of all-inside and inside-out meniscus repair techniques. It is recommended to start fixing the CMI first posteriorly. The posterior stitch is usually an all-inside horizontal mattress stitch. Coming 1 cm anteriorly, place a vertical mattress stitch. Continue this method sequentially while moving anteriorly. The anterior suture is the surgeon’s choice for device, but it should be a horizontal mattress like the most posterior stitch. It is important while tightening your suture tension to apply the concept of “approximated and not strangulated.” Once completed, close wounds in typical fashion.

1. Zaffagnini S, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Lopomo N, et al. Prospective long-term outcomes of the medial collagen meniscus implant versus partial medial meniscectomy: a minimum 10-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(5):977-985

2. Bulgheroni P, Murena L, Ratti C, Bulgheroni E, Ronga M, Cherubino P. Follow-up of collagen meniscus implant patients: clinical, radiological, and magnetic resonance imaging results at 5 years. Knee. 2010;17(3):224-229.

1. Zaffagnini S, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Lopomo N, et al. Prospective long-term outcomes of the medial collagen meniscus implant versus partial medial meniscectomy: a minimum 10-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(5):977-985

2. Bulgheroni P, Murena L, Ratti C, Bulgheroni E, Ronga M, Cherubino P. Follow-up of collagen meniscus implant patients: clinical, radiological, and magnetic resonance imaging results at 5 years. Knee. 2010;17(3):224-229.

Adoption of Choosing Wisely Recommendations Slow to Catch On

Clinical question: Have the Choosing Wisely campaign recommendations led to changes in practice?

Background: The Choosing Wisely campaign aims to reduce the incidence of low-value care by providing evidence-based recommendations for common clinical situations. The rate of adoption of these recommendations is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective review.

Setting: Anthem insurance members.

Synopsis: The study examined the claims data from 25 million Anthem insurance members to compare the rate of services that were targeted by seven Choosing Wisely campaign recommendations before and after the recommendations were published in 2012.

Investigators found the incidence of two of the services declined after the Choosing Wisely recommendations were published; the other five services remained stable or increased slightly. Furthermore, the declines were statistically significant but not a marked absolute difference, with the incidence of head imaging in patients with uncomplicated headaches going down to 13.4% from 14.9% and the use of cardiac imaging in the absence of cardiac disease declining to 9.7% from 10.8%.

The main limitations are the narrow population of Anthem insurance members and the lack of specific data that could help answer why clinical practice has not changed, but that could be the aim of future studies.

Bottom line: Choosing Wisely recommendations have not been adopted on a population level; widespread implementation likely will require financial incentives, provider-level data feedback, and systems interventions.

Citation: Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5441.

Clinical question: Have the Choosing Wisely campaign recommendations led to changes in practice?

Background: The Choosing Wisely campaign aims to reduce the incidence of low-value care by providing evidence-based recommendations for common clinical situations. The rate of adoption of these recommendations is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective review.

Setting: Anthem insurance members.

Synopsis: The study examined the claims data from 25 million Anthem insurance members to compare the rate of services that were targeted by seven Choosing Wisely campaign recommendations before and after the recommendations were published in 2012.

Investigators found the incidence of two of the services declined after the Choosing Wisely recommendations were published; the other five services remained stable or increased slightly. Furthermore, the declines were statistically significant but not a marked absolute difference, with the incidence of head imaging in patients with uncomplicated headaches going down to 13.4% from 14.9% and the use of cardiac imaging in the absence of cardiac disease declining to 9.7% from 10.8%.

The main limitations are the narrow population of Anthem insurance members and the lack of specific data that could help answer why clinical practice has not changed, but that could be the aim of future studies.

Bottom line: Choosing Wisely recommendations have not been adopted on a population level; widespread implementation likely will require financial incentives, provider-level data feedback, and systems interventions.

Citation: Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5441.

Clinical question: Have the Choosing Wisely campaign recommendations led to changes in practice?

Background: The Choosing Wisely campaign aims to reduce the incidence of low-value care by providing evidence-based recommendations for common clinical situations. The rate of adoption of these recommendations is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective review.

Setting: Anthem insurance members.

Synopsis: The study examined the claims data from 25 million Anthem insurance members to compare the rate of services that were targeted by seven Choosing Wisely campaign recommendations before and after the recommendations were published in 2012.

Investigators found the incidence of two of the services declined after the Choosing Wisely recommendations were published; the other five services remained stable or increased slightly. Furthermore, the declines were statistically significant but not a marked absolute difference, with the incidence of head imaging in patients with uncomplicated headaches going down to 13.4% from 14.9% and the use of cardiac imaging in the absence of cardiac disease declining to 9.7% from 10.8%.

The main limitations are the narrow population of Anthem insurance members and the lack of specific data that could help answer why clinical practice has not changed, but that could be the aim of future studies.

Bottom line: Choosing Wisely recommendations have not been adopted on a population level; widespread implementation likely will require financial incentives, provider-level data feedback, and systems interventions.

Citation: Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5441.

Overall Patient Satisfaction Better on Hospitalist Teams Compared with Teaching Teams

Clinical question: Is there a difference in patient experience on hospitalist teams compared with teaching teams?

Background: Hospitalist-intensive hospitals tend to perform better on patient-satisfaction measures on HCAHPS survey; however, little is known about the difference in patient experience between patients cared for by hospitalist and trainee teams.

Study design: Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting: University of Chicago Medical Center.

Synopsis: A 30-day post-discharge survey was sent to 14,855 patients cared for by hospitalist and teaching teams, with 57% of teaching and 31% of hospitalist team patients returning fully completed surveys. A higher percentage of hospitalist team patients reported satisfaction with their overall care (73% vs. 67%; P<0.001; regression model odds ratio = 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.47). There was no statistically significant difference in patient satisfaction with the teamwork of their providers, confidence in identifying their provider, or ability to understand the role of their provider.

Other than the inability to mitigate response-selection bias, the main limitation of this study is the single-center setting, which impacts the generalizability of the findings. Hospital-specific factors like different services and structures (hospitalists at their institution care for renal and lung transplant and oncology patients) could influence patients’ perception of their care. More research needs to be done to determine the specific factors that lead to a better patient experience.

Bottom line: At a single academic center, overall patient satisfaction was higher on a hospitalist service compared with teaching teams.

Citation: Wray CM, Flores A, Padula WV, Prochaska MT, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Measuring patient experiences on hospitalist and teaching services: patient responses to a 30-day postdischarge questionnaire [published online ahead of print September 18, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2485.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in patient experience on hospitalist teams compared with teaching teams?

Background: Hospitalist-intensive hospitals tend to perform better on patient-satisfaction measures on HCAHPS survey; however, little is known about the difference in patient experience between patients cared for by hospitalist and trainee teams.

Study design: Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting: University of Chicago Medical Center.

Synopsis: A 30-day post-discharge survey was sent to 14,855 patients cared for by hospitalist and teaching teams, with 57% of teaching and 31% of hospitalist team patients returning fully completed surveys. A higher percentage of hospitalist team patients reported satisfaction with their overall care (73% vs. 67%; P<0.001; regression model odds ratio = 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.47). There was no statistically significant difference in patient satisfaction with the teamwork of their providers, confidence in identifying their provider, or ability to understand the role of their provider.

Other than the inability to mitigate response-selection bias, the main limitation of this study is the single-center setting, which impacts the generalizability of the findings. Hospital-specific factors like different services and structures (hospitalists at their institution care for renal and lung transplant and oncology patients) could influence patients’ perception of their care. More research needs to be done to determine the specific factors that lead to a better patient experience.

Bottom line: At a single academic center, overall patient satisfaction was higher on a hospitalist service compared with teaching teams.

Citation: Wray CM, Flores A, Padula WV, Prochaska MT, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Measuring patient experiences on hospitalist and teaching services: patient responses to a 30-day postdischarge questionnaire [published online ahead of print September 18, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2485.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in patient experience on hospitalist teams compared with teaching teams?

Background: Hospitalist-intensive hospitals tend to perform better on patient-satisfaction measures on HCAHPS survey; however, little is known about the difference in patient experience between patients cared for by hospitalist and trainee teams.

Study design: Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting: University of Chicago Medical Center.

Synopsis: A 30-day post-discharge survey was sent to 14,855 patients cared for by hospitalist and teaching teams, with 57% of teaching and 31% of hospitalist team patients returning fully completed surveys. A higher percentage of hospitalist team patients reported satisfaction with their overall care (73% vs. 67%; P<0.001; regression model odds ratio = 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.47). There was no statistically significant difference in patient satisfaction with the teamwork of their providers, confidence in identifying their provider, or ability to understand the role of their provider.

Other than the inability to mitigate response-selection bias, the main limitation of this study is the single-center setting, which impacts the generalizability of the findings. Hospital-specific factors like different services and structures (hospitalists at their institution care for renal and lung transplant and oncology patients) could influence patients’ perception of their care. More research needs to be done to determine the specific factors that lead to a better patient experience.

Bottom line: At a single academic center, overall patient satisfaction was higher on a hospitalist service compared with teaching teams.

Citation: Wray CM, Flores A, Padula WV, Prochaska MT, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Measuring patient experiences on hospitalist and teaching services: patient responses to a 30-day postdischarge questionnaire [published online ahead of print September 18, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2485.

Caprini Score Accurately Predicts Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Critically Ill Surgical Patients

Clinical question: Is the Caprini risk assessment model (RAM) a valid tool to predict venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk in critically ill surgical patients?

Background: VTE is a major source of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients; prevention is critical to reduce morbidity and cut healthcare costs. Risk assessment is important to determine thromboprophylaxis, yet data are lacking regarding an appropriate tool for risk stratification in the critically ill.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: University of Michigan Health System; 20-bed surgical ICU at an academic hospital.

Synopsis: This study included 4,844 surgical ICU patients. Primary outcome was VTE during the patient’s hospital admission. A retrospective risk scoring method based on the 2005 Caprini RAM was used to calculate the risk for all patients at the time of ICU admission. Patients were divided into low (Caprini score 0–2), moderate, high, highest, and super-high (Caprini score > 8) risk levels. The incidence of VTE increased in linear fashion with increasing Caprini score.

This study was limited to one academic medical center. The retrospective scoring model limits the ability to identify all patient risk factors. VTE outcomes were reported only for the length of hospitalization and did not include post-discharge follow-up. Replicating this study across a larger patient population and performing a prospective study with follow-up after discharge would address these limitations.

Bottom line: The Caprini risk assessment model is a valid instrument to assess VTE risk in critically ill surgical patients.

Citation: Obi AT, Pannucci CJ, Nackashi A, et al. Validation of the Caprini venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in critically ill surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):941-948.

Clinical question: Is the Caprini risk assessment model (RAM) a valid tool to predict venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk in critically ill surgical patients?

Background: VTE is a major source of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients; prevention is critical to reduce morbidity and cut healthcare costs. Risk assessment is important to determine thromboprophylaxis, yet data are lacking regarding an appropriate tool for risk stratification in the critically ill.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: University of Michigan Health System; 20-bed surgical ICU at an academic hospital.

Synopsis: This study included 4,844 surgical ICU patients. Primary outcome was VTE during the patient’s hospital admission. A retrospective risk scoring method based on the 2005 Caprini RAM was used to calculate the risk for all patients at the time of ICU admission. Patients were divided into low (Caprini score 0–2), moderate, high, highest, and super-high (Caprini score > 8) risk levels. The incidence of VTE increased in linear fashion with increasing Caprini score.

This study was limited to one academic medical center. The retrospective scoring model limits the ability to identify all patient risk factors. VTE outcomes were reported only for the length of hospitalization and did not include post-discharge follow-up. Replicating this study across a larger patient population and performing a prospective study with follow-up after discharge would address these limitations.

Bottom line: The Caprini risk assessment model is a valid instrument to assess VTE risk in critically ill surgical patients.

Citation: Obi AT, Pannucci CJ, Nackashi A, et al. Validation of the Caprini venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in critically ill surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):941-948.

Clinical question: Is the Caprini risk assessment model (RAM) a valid tool to predict venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk in critically ill surgical patients?

Background: VTE is a major source of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients; prevention is critical to reduce morbidity and cut healthcare costs. Risk assessment is important to determine thromboprophylaxis, yet data are lacking regarding an appropriate tool for risk stratification in the critically ill.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: University of Michigan Health System; 20-bed surgical ICU at an academic hospital.

Synopsis: This study included 4,844 surgical ICU patients. Primary outcome was VTE during the patient’s hospital admission. A retrospective risk scoring method based on the 2005 Caprini RAM was used to calculate the risk for all patients at the time of ICU admission. Patients were divided into low (Caprini score 0–2), moderate, high, highest, and super-high (Caprini score > 8) risk levels. The incidence of VTE increased in linear fashion with increasing Caprini score.

This study was limited to one academic medical center. The retrospective scoring model limits the ability to identify all patient risk factors. VTE outcomes were reported only for the length of hospitalization and did not include post-discharge follow-up. Replicating this study across a larger patient population and performing a prospective study with follow-up after discharge would address these limitations.

Bottom line: The Caprini risk assessment model is a valid instrument to assess VTE risk in critically ill surgical patients.

Citation: Obi AT, Pannucci CJ, Nackashi A, et al. Validation of the Caprini venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in critically ill surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):941-948.

Total Knee Replacement Superior to Non-Surgical Intervention

Clinical question: Does total knee replacement followed by a 12-week non-surgical treatment program provide greater pain relief and improvement in function and quality of life than non-surgical treatment alone?

Background: The number of total knee replacements in the U.S. has increased dramatically since the 1970s and is expected to continue to rise. To date, evidence to support the effectiveness of surgical intervention compared to non-surgical intervention is lacking.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Aalborg University Hospital Outpatient Clinics, Denmark.

Synopsis: One hundred patients with osteoarthritis were randomly assigned to undergo total knee replacement followed by 12 weeks of non-surgical treatment or to receive only 12 weeks of non-surgical treatment. The non-surgical treatment program consisted of exercise, education, dietary advice, insoles, and pain medication. Change from baseline to 12 months was assessed using the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS).

The total knee replacement group had a significantly greater improvement in the KOOS score than did the non-surgical group. Serious adverse events were more common in the total knee replacement group.

The study did not include a sham-surgery control group. It is unknown whether the KOOS pain subscale is generalizable to patients with severe pain. Additionally, the intensity of non-surgical treatment may have differed between groups.

Bottom line: Total knee replacement followed by non-surgical treatment is more efficacious than non-surgical treatment alone in providing pain relief and improving function and quality of life, but it is associated with higher number of adverse events.

Citation: Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1597-1606.

Clinical question: Does total knee replacement followed by a 12-week non-surgical treatment program provide greater pain relief and improvement in function and quality of life than non-surgical treatment alone?

Background: The number of total knee replacements in the U.S. has increased dramatically since the 1970s and is expected to continue to rise. To date, evidence to support the effectiveness of surgical intervention compared to non-surgical intervention is lacking.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Aalborg University Hospital Outpatient Clinics, Denmark.

Synopsis: One hundred patients with osteoarthritis were randomly assigned to undergo total knee replacement followed by 12 weeks of non-surgical treatment or to receive only 12 weeks of non-surgical treatment. The non-surgical treatment program consisted of exercise, education, dietary advice, insoles, and pain medication. Change from baseline to 12 months was assessed using the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS).

The total knee replacement group had a significantly greater improvement in the KOOS score than did the non-surgical group. Serious adverse events were more common in the total knee replacement group.

The study did not include a sham-surgery control group. It is unknown whether the KOOS pain subscale is generalizable to patients with severe pain. Additionally, the intensity of non-surgical treatment may have differed between groups.

Bottom line: Total knee replacement followed by non-surgical treatment is more efficacious than non-surgical treatment alone in providing pain relief and improving function and quality of life, but it is associated with higher number of adverse events.

Citation: Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1597-1606.

Clinical question: Does total knee replacement followed by a 12-week non-surgical treatment program provide greater pain relief and improvement in function and quality of life than non-surgical treatment alone?

Background: The number of total knee replacements in the U.S. has increased dramatically since the 1970s and is expected to continue to rise. To date, evidence to support the effectiveness of surgical intervention compared to non-surgical intervention is lacking.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Aalborg University Hospital Outpatient Clinics, Denmark.

Synopsis: One hundred patients with osteoarthritis were randomly assigned to undergo total knee replacement followed by 12 weeks of non-surgical treatment or to receive only 12 weeks of non-surgical treatment. The non-surgical treatment program consisted of exercise, education, dietary advice, insoles, and pain medication. Change from baseline to 12 months was assessed using the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS).

The total knee replacement group had a significantly greater improvement in the KOOS score than did the non-surgical group. Serious adverse events were more common in the total knee replacement group.

The study did not include a sham-surgery control group. It is unknown whether the KOOS pain subscale is generalizable to patients with severe pain. Additionally, the intensity of non-surgical treatment may have differed between groups.

Bottom line: Total knee replacement followed by non-surgical treatment is more efficacious than non-surgical treatment alone in providing pain relief and improving function and quality of life, but it is associated with higher number of adverse events.

Citation: Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1597-1606.

Patients with Postoperative Myocardial Infarction May Benefit from Higher Transfusion Threshold

Clinical question: Is there an improved 30-day mortality rate if patients receive blood transfusion at higher hematocrit values after postoperative myocardial infarction (MI)?

Background: Prior studies evaluating patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) who undergo non-cardiac surgery have shown similar mortality outcomes with liberal and restrictive transfusion strategies. Data are lacking for transfusion strategies in patients with CAD who experience postoperative MI after non-cardiac surgeries.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Veterans Affairs health system.

Synopsis: The study included 7,361 patients with a history of CAD who underwent non-cardiac surgery whose postoperative hematocrit was between 20% and 30%. Patients were stratified by postoperative hematocrit nadir and presence of postoperative MI. In patients with postoperative MI, transfusion was associated with lower mortality with hematocrit nadir of 20%–24% but not with hematocrit of 24%–27% or 27%–30%. In patients without postoperative MI, transfusion was associated with higher mortality in patients with hematocrit of 27%–30%.

This retrospective study was limited to the VA population of mostly male patients. The sample size was limited. The study was unable to determine if postoperative blood transfusion is a risk for developing MI.

Bottom line: Patients with a history of CAD and MI who have a postoperative MI following non-cardiac surgery may benefit from higher blood transfusion thresholds; however, further controlled studies are needed.

Citation: Hollis RH, Singeltary BA, McMurtrie JT, et al. Blood transfusion and 30-day mortality in patients with coronary artery disease and anemia following noncardiac surgery [published online ahead of print October 7, 2015]. JAMA Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3420.

Clinical question: Is there an improved 30-day mortality rate if patients receive blood transfusion at higher hematocrit values after postoperative myocardial infarction (MI)?

Background: Prior studies evaluating patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) who undergo non-cardiac surgery have shown similar mortality outcomes with liberal and restrictive transfusion strategies. Data are lacking for transfusion strategies in patients with CAD who experience postoperative MI after non-cardiac surgeries.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Veterans Affairs health system.

Synopsis: The study included 7,361 patients with a history of CAD who underwent non-cardiac surgery whose postoperative hematocrit was between 20% and 30%. Patients were stratified by postoperative hematocrit nadir and presence of postoperative MI. In patients with postoperative MI, transfusion was associated with lower mortality with hematocrit nadir of 20%–24% but not with hematocrit of 24%–27% or 27%–30%. In patients without postoperative MI, transfusion was associated with higher mortality in patients with hematocrit of 27%–30%.

This retrospective study was limited to the VA population of mostly male patients. The sample size was limited. The study was unable to determine if postoperative blood transfusion is a risk for developing MI.

Bottom line: Patients with a history of CAD and MI who have a postoperative MI following non-cardiac surgery may benefit from higher blood transfusion thresholds; however, further controlled studies are needed.

Citation: Hollis RH, Singeltary BA, McMurtrie JT, et al. Blood transfusion and 30-day mortality in patients with coronary artery disease and anemia following noncardiac surgery [published online ahead of print October 7, 2015]. JAMA Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3420.

Clinical question: Is there an improved 30-day mortality rate if patients receive blood transfusion at higher hematocrit values after postoperative myocardial infarction (MI)?

Background: Prior studies evaluating patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) who undergo non-cardiac surgery have shown similar mortality outcomes with liberal and restrictive transfusion strategies. Data are lacking for transfusion strategies in patients with CAD who experience postoperative MI after non-cardiac surgeries.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Veterans Affairs health system.

Synopsis: The study included 7,361 patients with a history of CAD who underwent non-cardiac surgery whose postoperative hematocrit was between 20% and 30%. Patients were stratified by postoperative hematocrit nadir and presence of postoperative MI. In patients with postoperative MI, transfusion was associated with lower mortality with hematocrit nadir of 20%–24% but not with hematocrit of 24%–27% or 27%–30%. In patients without postoperative MI, transfusion was associated with higher mortality in patients with hematocrit of 27%–30%.

This retrospective study was limited to the VA population of mostly male patients. The sample size was limited. The study was unable to determine if postoperative blood transfusion is a risk for developing MI.

Bottom line: Patients with a history of CAD and MI who have a postoperative MI following non-cardiac surgery may benefit from higher blood transfusion thresholds; however, further controlled studies are needed.

Citation: Hollis RH, Singeltary BA, McMurtrie JT, et al. Blood transfusion and 30-day mortality in patients with coronary artery disease and anemia following noncardiac surgery [published online ahead of print October 7, 2015]. JAMA Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3420.

Beta-Blockers May Increase Risk of Perioperative MACEs in Patients with Uncomplicated Hypertension

Clinical question: Does taking a perioperative beta-blocker increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and all-cause mortality in low-risk patients with essential hypertension (HTN)?

Background: Guidelines for the use of perioperative beta-blockers are being reevaluated due to concerns about validity of prior studies that supported the use of perioperative beta-blockers. This study sought to evaluate effectiveness and safety of beta-blockers in patients with uncomplicated HTN.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Denmark.

Synopsis: This study included 55,320 hypertensive patients using at least two antihypertensive drugs who underwent non-cardiac surgery. Of these, 14,644 patients were treated with a beta-blocker. Patients with secondary cardiovascular conditions, renal disease, or liver disease were excluded; 30-day MACEs and all-cause mortality were analyzed.

In patients treated with a beta-blocker, the incidence of 30-day MACEs was 1.32% compared with 0.84% in the non-beta-blockers group; 30-day mortality in those treated with beta-blocker was 1.9% compared with 1.3% in the non-beta-blocker group. Risk of beta-blocker-associated MACEs was higher in patients 70 and older. Causality cannot be concluded based on observational data.

Bottom line: In patients with uncomplicated HTN, treatment with a beta-blocker may be associated with increased 30-day risk of perioperative MACEs after non-cardiac surgery.

Citation: Jorgensen ME, Hlatky MA, Kober L, et al. Beta-blocker-associated risks in patients with uncomplicated hypertension undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1923-1931.

Clinical question: Does taking a perioperative beta-blocker increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and all-cause mortality in low-risk patients with essential hypertension (HTN)?

Background: Guidelines for the use of perioperative beta-blockers are being reevaluated due to concerns about validity of prior studies that supported the use of perioperative beta-blockers. This study sought to evaluate effectiveness and safety of beta-blockers in patients with uncomplicated HTN.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Denmark.

Synopsis: This study included 55,320 hypertensive patients using at least two antihypertensive drugs who underwent non-cardiac surgery. Of these, 14,644 patients were treated with a beta-blocker. Patients with secondary cardiovascular conditions, renal disease, or liver disease were excluded; 30-day MACEs and all-cause mortality were analyzed.

In patients treated with a beta-blocker, the incidence of 30-day MACEs was 1.32% compared with 0.84% in the non-beta-blockers group; 30-day mortality in those treated with beta-blocker was 1.9% compared with 1.3% in the non-beta-blocker group. Risk of beta-blocker-associated MACEs was higher in patients 70 and older. Causality cannot be concluded based on observational data.

Bottom line: In patients with uncomplicated HTN, treatment with a beta-blocker may be associated with increased 30-day risk of perioperative MACEs after non-cardiac surgery.

Citation: Jorgensen ME, Hlatky MA, Kober L, et al. Beta-blocker-associated risks in patients with uncomplicated hypertension undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1923-1931.

Clinical question: Does taking a perioperative beta-blocker increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and all-cause mortality in low-risk patients with essential hypertension (HTN)?

Background: Guidelines for the use of perioperative beta-blockers are being reevaluated due to concerns about validity of prior studies that supported the use of perioperative beta-blockers. This study sought to evaluate effectiveness and safety of beta-blockers in patients with uncomplicated HTN.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Denmark.

Synopsis: This study included 55,320 hypertensive patients using at least two antihypertensive drugs who underwent non-cardiac surgery. Of these, 14,644 patients were treated with a beta-blocker. Patients with secondary cardiovascular conditions, renal disease, or liver disease were excluded; 30-day MACEs and all-cause mortality were analyzed.

In patients treated with a beta-blocker, the incidence of 30-day MACEs was 1.32% compared with 0.84% in the non-beta-blockers group; 30-day mortality in those treated with beta-blocker was 1.9% compared with 1.3% in the non-beta-blocker group. Risk of beta-blocker-associated MACEs was higher in patients 70 and older. Causality cannot be concluded based on observational data.

Bottom line: In patients with uncomplicated HTN, treatment with a beta-blocker may be associated with increased 30-day risk of perioperative MACEs after non-cardiac surgery.

Citation: Jorgensen ME, Hlatky MA, Kober L, et al. Beta-blocker-associated risks in patients with uncomplicated hypertension undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1923-1931.

Pharmacist Involvement in Transitional Care Can Reduce Return ED Visits, Inpatient Readmissions

Clinical question: Does pharmacist involvement in transitions of care decrease medication errors (MEs), adverse drug events (ADEs), and 30-day ED visits and inpatient readmissions?

Background: Previous studies show pharmacist involvement in discharge can reduce ADEs and improve patient satisfaction, but there have been inconsistent data on the impact of pharmacist involvement on readmissions, ADEs, and MEs.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, single-period, longitudinal study.

Setting: Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago.

Synopsis: Investigators included 278 patients (137 in study arm, 141 in control arm) in the final analysis. The study arm received intensive pharmacist involvement on admission and discharge, followed by phone calls at three, 14, and 30 days post-discharge. The study arm had lower composite 30-day ED visits and inpatient readmission rates compared to the control group (25% vs. 39%; P=0.001) but did not have lower isolated inpatient readmission rates (20% vs. 24%; P=0.43). ADEs and MEs were not significantly different between the two groups.

This study had extensive exclusion criteria, limiting the patient population to which these results can be applied. It was underpowered, which could have prevented the detection of a significant improvement in readmission rates.

Care transitions are high-risk periods in patient care, and there is benefit to continuity of care of an interdisciplinary team, including pharmacists.

Bottom line: Pharmacist involvement in transitions of care was shown to reduce the composite of ED visits and inpatient readmissions.

Citation: Phatak A, Prusi R, Ward B, et al. Impact of pharmacist involvement in the transitional care of high-risk patients through medication reconciliation, medication education, and postdischarge call-backs (IPITCH Study). J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):39-44. doi:10.1002/jhm.2493.

Clinical question: Does pharmacist involvement in transitions of care decrease medication errors (MEs), adverse drug events (ADEs), and 30-day ED visits and inpatient readmissions?

Background: Previous studies show pharmacist involvement in discharge can reduce ADEs and improve patient satisfaction, but there have been inconsistent data on the impact of pharmacist involvement on readmissions, ADEs, and MEs.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, single-period, longitudinal study.

Setting: Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago.

Synopsis: Investigators included 278 patients (137 in study arm, 141 in control arm) in the final analysis. The study arm received intensive pharmacist involvement on admission and discharge, followed by phone calls at three, 14, and 30 days post-discharge. The study arm had lower composite 30-day ED visits and inpatient readmission rates compared to the control group (25% vs. 39%; P=0.001) but did not have lower isolated inpatient readmission rates (20% vs. 24%; P=0.43). ADEs and MEs were not significantly different between the two groups.

This study had extensive exclusion criteria, limiting the patient population to which these results can be applied. It was underpowered, which could have prevented the detection of a significant improvement in readmission rates.

Care transitions are high-risk periods in patient care, and there is benefit to continuity of care of an interdisciplinary team, including pharmacists.

Bottom line: Pharmacist involvement in transitions of care was shown to reduce the composite of ED visits and inpatient readmissions.

Citation: Phatak A, Prusi R, Ward B, et al. Impact of pharmacist involvement in the transitional care of high-risk patients through medication reconciliation, medication education, and postdischarge call-backs (IPITCH Study). J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):39-44. doi:10.1002/jhm.2493.

Clinical question: Does pharmacist involvement in transitions of care decrease medication errors (MEs), adverse drug events (ADEs), and 30-day ED visits and inpatient readmissions?

Background: Previous studies show pharmacist involvement in discharge can reduce ADEs and improve patient satisfaction, but there have been inconsistent data on the impact of pharmacist involvement on readmissions, ADEs, and MEs.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, single-period, longitudinal study.

Setting: Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago.

Synopsis: Investigators included 278 patients (137 in study arm, 141 in control arm) in the final analysis. The study arm received intensive pharmacist involvement on admission and discharge, followed by phone calls at three, 14, and 30 days post-discharge. The study arm had lower composite 30-day ED visits and inpatient readmission rates compared to the control group (25% vs. 39%; P=0.001) but did not have lower isolated inpatient readmission rates (20% vs. 24%; P=0.43). ADEs and MEs were not significantly different between the two groups.

This study had extensive exclusion criteria, limiting the patient population to which these results can be applied. It was underpowered, which could have prevented the detection of a significant improvement in readmission rates.

Care transitions are high-risk periods in patient care, and there is benefit to continuity of care of an interdisciplinary team, including pharmacists.

Bottom line: Pharmacist involvement in transitions of care was shown to reduce the composite of ED visits and inpatient readmissions.

Citation: Phatak A, Prusi R, Ward B, et al. Impact of pharmacist involvement in the transitional care of high-risk patients through medication reconciliation, medication education, and postdischarge call-backs (IPITCH Study). J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):39-44. doi:10.1002/jhm.2493.

Displaying Prices to Providers May Reduce Overall Ordering Costs

Clinical question: Does price display impact order costs and volume as well as patient safety outcomes, and is it acceptable to providers?

Background: Up to one-third of national healthcare expenditures are wasteful, with physicians playing a central role in overall cost, purchasing almost all tests and therapies for patients. Increasing the transparency of costs for physicians is one strategy to reduce unnecessary spending.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Synopsis: Nineteen publications were selected for final analysis. Thirteen studies reported the impact of price display on costs, nine of which showed a statistically significant decrease in order costs. Only three of eight studies reporting the impact of price display on order volume showed statistically significant decreases in order volume. One study showed adverse safety findings in the form of higher rates of unscheduled follow-up care in a pediatric ED. Physicians were overall satisfied with price display in the five studies reporting this.

There was high heterogeneity among studies, which did not allow for pooling of data. Furthermore, more than half of the studies were conducted more than 15 years ago, limiting their generalizability to the modern era of electronic health records (EHRs).

Overall, this review supports the conclusion that price display has a modest effect on order costs. Additional studies utilizing EHR systems are required to more definitively confirm these findings.

Bottom line: Displaying prices to physicians can have a modest effect on overall order costs.

Citation: Silvestri MT, Bongiovanni TR, Glover JG, Gross CP. Impact of price display on provider ordering: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):65-76. doi:10.1002/jhm.2500.

Clinical question: Does price display impact order costs and volume as well as patient safety outcomes, and is it acceptable to providers?

Background: Up to one-third of national healthcare expenditures are wasteful, with physicians playing a central role in overall cost, purchasing almost all tests and therapies for patients. Increasing the transparency of costs for physicians is one strategy to reduce unnecessary spending.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Synopsis: Nineteen publications were selected for final analysis. Thirteen studies reported the impact of price display on costs, nine of which showed a statistically significant decrease in order costs. Only three of eight studies reporting the impact of price display on order volume showed statistically significant decreases in order volume. One study showed adverse safety findings in the form of higher rates of unscheduled follow-up care in a pediatric ED. Physicians were overall satisfied with price display in the five studies reporting this.

There was high heterogeneity among studies, which did not allow for pooling of data. Furthermore, more than half of the studies were conducted more than 15 years ago, limiting their generalizability to the modern era of electronic health records (EHRs).

Overall, this review supports the conclusion that price display has a modest effect on order costs. Additional studies utilizing EHR systems are required to more definitively confirm these findings.

Bottom line: Displaying prices to physicians can have a modest effect on overall order costs.

Citation: Silvestri MT, Bongiovanni TR, Glover JG, Gross CP. Impact of price display on provider ordering: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):65-76. doi:10.1002/jhm.2500.

Clinical question: Does price display impact order costs and volume as well as patient safety outcomes, and is it acceptable to providers?

Background: Up to one-third of national healthcare expenditures are wasteful, with physicians playing a central role in overall cost, purchasing almost all tests and therapies for patients. Increasing the transparency of costs for physicians is one strategy to reduce unnecessary spending.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Synopsis: Nineteen publications were selected for final analysis. Thirteen studies reported the impact of price display on costs, nine of which showed a statistically significant decrease in order costs. Only three of eight studies reporting the impact of price display on order volume showed statistically significant decreases in order volume. One study showed adverse safety findings in the form of higher rates of unscheduled follow-up care in a pediatric ED. Physicians were overall satisfied with price display in the five studies reporting this.

There was high heterogeneity among studies, which did not allow for pooling of data. Furthermore, more than half of the studies were conducted more than 15 years ago, limiting their generalizability to the modern era of electronic health records (EHRs).

Overall, this review supports the conclusion that price display has a modest effect on order costs. Additional studies utilizing EHR systems are required to more definitively confirm these findings.

Bottom line: Displaying prices to physicians can have a modest effect on overall order costs.

Citation: Silvestri MT, Bongiovanni TR, Glover JG, Gross CP. Impact of price display on provider ordering: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):65-76. doi:10.1002/jhm.2500.

ACCF/AHA 2013 Guidelines for Managing Heart Failure

Background

Heart failure (HF) is the No. 1 cause of both hospitalization and readmission among Americans 65 years and older.1 Hospitalizations in the HF population are associated with poor patient outcomes (30% mortality in the following year) and high costs, accounting for approximately 70% of the $32 billion spent on HF care annually in the United States.1 In 2009, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the 30-day, risk-standardized, all-cause readmission for HF as an indicator of quality and efficiency of care, which has since been incorporated into Medicare’s value-based purchasing program.2

HF is a complex syndrome that is associated with multiple comorbidities. Appropriate to these issues, management is multifaceted and involves care across the spectrum of disease:

- Diagnosing and treating underlying causes;

- Minimizing exacerbants;

- Optimizing management of comorbidities;

- Addressing psychosocial and environmental issues beyond the hospital; and

- Confronting end-of-life care.

In order to address this continuum of disease management, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) simultaneously released a new Guideline for the Management of HF in June in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation.3,4 This update was developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, Heart Rhythm Society, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The goals of the document are to improve quality of care, optimize patient outcomes, and advance the efficient use of healthcare resources. The guideline includes important recommendations for overall care, but particularly for hospital-based care and transitions of care that are largely the purview of hospitalists.

Guideline Update

The 2013 guideline is the third revision of the original guideline that was released in 2000. Despite being a complete rewrite of the 2009 HF guideline, the updated document contains relatively few changes to the recommendations that are Class I (should be performed) and III (no benefit or harm). The most significant randomized controlled trials in HF patients that have been published since the 2009 guideline include EMPHASIS-HF5 and MADIT-CRT/RAFT, which expand indications for aldosterone antagonists (AA) and cardiac resyncronization therapy (CRT), respectively, to patients with mild symptoms.5,6,7 Additionally, the WARCEF trial was published, which failed to demonstrate a significant difference in death, ischemic stroke, or intracerebral hemorrhage between treatment with warfarin or aspirin in patients with HF and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in sinus rhythm.8

The most notable updates from the 2009 guideline include (* = Class I and III indications):

- The definition of HF has been revised to include: 1) HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF; LVEF ≤40%), 2) HF failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF; LVEF ≥50%), 3) HFpEF, borderline (LVEF 41-49%), and 4) HFpEF, improved (LVEF >40%).

- In the hospitalized patient, measurement of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or NT-proBNP is useful to support clinical judgment for the diagnosis of acutely decompensated HF, especially in the setting of uncertainty for the diagnosis.*

- AA should be used in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional Class II-IV and LVEF ≤35% unless contraindicated (creatinine ≤2.5 mg/dL in men, ≤2.0 mg/dL in women, and potassium <5.0 mEq/L).*

- CRT is indicated for patients who have LVEF of 35% or less, sinus rhythm, left bundle-branch block with a QRS duration of ³150 ms, and NYHA functional Class II-IV on guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).*

- Anticoagulation should not be used in patients with chronic HFrEF without atrial fibrillation, prior thromboembolic event, or cardioembolic source.*

- Transitions of care and GDMT can be improved by employing the following: 1) use of performance-improvement systems to identify HF patients, 2) development of multidisciplinary HF disease-management programs for patients at high risk of readmission, and 3) placing phone calls to the patient within three days of discharge and scheduling a follow-up visit within seven to 14 days.

Analysis

Overall, the new guideline provides a thorough reassessment and expert analysis on the diagnosis and management of HF for both inpatient and outpatient care. The authors introduce the phrase “guideline-directed medical therapy” (GDMT) to emphasize the smaller set of recommendations that constitute optimal medical therapy for HF patients. This designation, encompassing primarily Class I recommendations, helps providers rapidly determine the optimal treatment course for an individual patient. The mainstay of GDMT in HFrEF patients remains angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) when ACE-I-intolerant, beta-blockers, and, in select patients, AA, hydralazine-nitrates, and diuretics.

A major shift in focus is seen in the new guideline with a greater emphasis on improved patient-centered outcomes across the spectrum of the disease. HF requires a continuum of care, from screening and genetic testing of family members of patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy to conversations about palliative care and hospice. To this end, the authors highlight quality of life, shared decision-making, care coordination, transitions of care, and appropriateness of palliative care in a chronic disease state.

Further, the guideline expands upon previous recommendations for compliance with performance and quality metrics. Quality of care and adherence to performance measures of HF patients are becoming increasingly recognized, particularly in the hospital setting. The guideline offers recommendations for transitions of care in the hospitalized patient, which utilize systems of care coordination to ensure an evidence-based plan of care that includes the achievement of GDMT goals, effective management of comorbid conditions, timely follow-up, and appropriate dietary and physical activities.

HM Takeaways

HF is one of the most common, most challenging diseases managed by hospitalists. The 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of HF, while providing a comprehensive summary of evidence with recommendations for the totality of care for these patients throughout the course of the disease, places heavy emphasis on management during hospitalization and transitions. This includes repositioning of performance measures involving GDMT to better ensure optimal use of proven therapies in HFrEF, evidence-based steps to reduce readmissions, and greater recognition of the role of palliative care for patients with advanced disease.

Drs. McIlvennan and Allen are cardiologists in the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. Dr. Allen also works in the Colorado Health Outcomes Program.

References available at the-hospitalist.org.

Background

Heart failure (HF) is the No. 1 cause of both hospitalization and readmission among Americans 65 years and older.1 Hospitalizations in the HF population are associated with poor patient outcomes (30% mortality in the following year) and high costs, accounting for approximately 70% of the $32 billion spent on HF care annually in the United States.1 In 2009, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the 30-day, risk-standardized, all-cause readmission for HF as an indicator of quality and efficiency of care, which has since been incorporated into Medicare’s value-based purchasing program.2

HF is a complex syndrome that is associated with multiple comorbidities. Appropriate to these issues, management is multifaceted and involves care across the spectrum of disease:

- Diagnosing and treating underlying causes;

- Minimizing exacerbants;

- Optimizing management of comorbidities;

- Addressing psychosocial and environmental issues beyond the hospital; and

- Confronting end-of-life care.

In order to address this continuum of disease management, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) simultaneously released a new Guideline for the Management of HF in June in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation.3,4 This update was developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, Heart Rhythm Society, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The goals of the document are to improve quality of care, optimize patient outcomes, and advance the efficient use of healthcare resources. The guideline includes important recommendations for overall care, but particularly for hospital-based care and transitions of care that are largely the purview of hospitalists.

Guideline Update

The 2013 guideline is the third revision of the original guideline that was released in 2000. Despite being a complete rewrite of the 2009 HF guideline, the updated document contains relatively few changes to the recommendations that are Class I (should be performed) and III (no benefit or harm). The most significant randomized controlled trials in HF patients that have been published since the 2009 guideline include EMPHASIS-HF5 and MADIT-CRT/RAFT, which expand indications for aldosterone antagonists (AA) and cardiac resyncronization therapy (CRT), respectively, to patients with mild symptoms.5,6,7 Additionally, the WARCEF trial was published, which failed to demonstrate a significant difference in death, ischemic stroke, or intracerebral hemorrhage between treatment with warfarin or aspirin in patients with HF and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in sinus rhythm.8

The most notable updates from the 2009 guideline include (* = Class I and III indications):

- The definition of HF has been revised to include: 1) HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF; LVEF ≤40%), 2) HF failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF; LVEF ≥50%), 3) HFpEF, borderline (LVEF 41-49%), and 4) HFpEF, improved (LVEF >40%).

- In the hospitalized patient, measurement of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or NT-proBNP is useful to support clinical judgment for the diagnosis of acutely decompensated HF, especially in the setting of uncertainty for the diagnosis.*

- AA should be used in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional Class II-IV and LVEF ≤35% unless contraindicated (creatinine ≤2.5 mg/dL in men, ≤2.0 mg/dL in women, and potassium <5.0 mEq/L).*

- CRT is indicated for patients who have LVEF of 35% or less, sinus rhythm, left bundle-branch block with a QRS duration of ³150 ms, and NYHA functional Class II-IV on guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).*

- Anticoagulation should not be used in patients with chronic HFrEF without atrial fibrillation, prior thromboembolic event, or cardioembolic source.*

- Transitions of care and GDMT can be improved by employing the following: 1) use of performance-improvement systems to identify HF patients, 2) development of multidisciplinary HF disease-management programs for patients at high risk of readmission, and 3) placing phone calls to the patient within three days of discharge and scheduling a follow-up visit within seven to 14 days.

Analysis

Overall, the new guideline provides a thorough reassessment and expert analysis on the diagnosis and management of HF for both inpatient and outpatient care. The authors introduce the phrase “guideline-directed medical therapy” (GDMT) to emphasize the smaller set of recommendations that constitute optimal medical therapy for HF patients. This designation, encompassing primarily Class I recommendations, helps providers rapidly determine the optimal treatment course for an individual patient. The mainstay of GDMT in HFrEF patients remains angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) when ACE-I-intolerant, beta-blockers, and, in select patients, AA, hydralazine-nitrates, and diuretics.

A major shift in focus is seen in the new guideline with a greater emphasis on improved patient-centered outcomes across the spectrum of the disease. HF requires a continuum of care, from screening and genetic testing of family members of patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy to conversations about palliative care and hospice. To this end, the authors highlight quality of life, shared decision-making, care coordination, transitions of care, and appropriateness of palliative care in a chronic disease state.

Further, the guideline expands upon previous recommendations for compliance with performance and quality metrics. Quality of care and adherence to performance measures of HF patients are becoming increasingly recognized, particularly in the hospital setting. The guideline offers recommendations for transitions of care in the hospitalized patient, which utilize systems of care coordination to ensure an evidence-based plan of care that includes the achievement of GDMT goals, effective management of comorbid conditions, timely follow-up, and appropriate dietary and physical activities.

HM Takeaways

HF is one of the most common, most challenging diseases managed by hospitalists. The 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of HF, while providing a comprehensive summary of evidence with recommendations for the totality of care for these patients throughout the course of the disease, places heavy emphasis on management during hospitalization and transitions. This includes repositioning of performance measures involving GDMT to better ensure optimal use of proven therapies in HFrEF, evidence-based steps to reduce readmissions, and greater recognition of the role of palliative care for patients with advanced disease.

Drs. McIlvennan and Allen are cardiologists in the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. Dr. Allen also works in the Colorado Health Outcomes Program.

References available at the-hospitalist.org.

Background

Heart failure (HF) is the No. 1 cause of both hospitalization and readmission among Americans 65 years and older.1 Hospitalizations in the HF population are associated with poor patient outcomes (30% mortality in the following year) and high costs, accounting for approximately 70% of the $32 billion spent on HF care annually in the United States.1 In 2009, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the 30-day, risk-standardized, all-cause readmission for HF as an indicator of quality and efficiency of care, which has since been incorporated into Medicare’s value-based purchasing program.2

HF is a complex syndrome that is associated with multiple comorbidities. Appropriate to these issues, management is multifaceted and involves care across the spectrum of disease:

- Diagnosing and treating underlying causes;

- Minimizing exacerbants;

- Optimizing management of comorbidities;

- Addressing psychosocial and environmental issues beyond the hospital; and

- Confronting end-of-life care.

In order to address this continuum of disease management, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) simultaneously released a new Guideline for the Management of HF in June in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation.3,4 This update was developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, Heart Rhythm Society, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The goals of the document are to improve quality of care, optimize patient outcomes, and advance the efficient use of healthcare resources. The guideline includes important recommendations for overall care, but particularly for hospital-based care and transitions of care that are largely the purview of hospitalists.

Guideline Update

The 2013 guideline is the third revision of the original guideline that was released in 2000. Despite being a complete rewrite of the 2009 HF guideline, the updated document contains relatively few changes to the recommendations that are Class I (should be performed) and III (no benefit or harm). The most significant randomized controlled trials in HF patients that have been published since the 2009 guideline include EMPHASIS-HF5 and MADIT-CRT/RAFT, which expand indications for aldosterone antagonists (AA) and cardiac resyncronization therapy (CRT), respectively, to patients with mild symptoms.5,6,7 Additionally, the WARCEF trial was published, which failed to demonstrate a significant difference in death, ischemic stroke, or intracerebral hemorrhage between treatment with warfarin or aspirin in patients with HF and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in sinus rhythm.8

The most notable updates from the 2009 guideline include (* = Class I and III indications):

- The definition of HF has been revised to include: 1) HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF; LVEF ≤40%), 2) HF failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF; LVEF ≥50%), 3) HFpEF, borderline (LVEF 41-49%), and 4) HFpEF, improved (LVEF >40%).

- In the hospitalized patient, measurement of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or NT-proBNP is useful to support clinical judgment for the diagnosis of acutely decompensated HF, especially in the setting of uncertainty for the diagnosis.*

- AA should be used in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional Class II-IV and LVEF ≤35% unless contraindicated (creatinine ≤2.5 mg/dL in men, ≤2.0 mg/dL in women, and potassium <5.0 mEq/L).*

- CRT is indicated for patients who have LVEF of 35% or less, sinus rhythm, left bundle-branch block with a QRS duration of ³150 ms, and NYHA functional Class II-IV on guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).*

- Anticoagulation should not be used in patients with chronic HFrEF without atrial fibrillation, prior thromboembolic event, or cardioembolic source.*

- Transitions of care and GDMT can be improved by employing the following: 1) use of performance-improvement systems to identify HF patients, 2) development of multidisciplinary HF disease-management programs for patients at high risk of readmission, and 3) placing phone calls to the patient within three days of discharge and scheduling a follow-up visit within seven to 14 days.

Analysis

Overall, the new guideline provides a thorough reassessment and expert analysis on the diagnosis and management of HF for both inpatient and outpatient care. The authors introduce the phrase “guideline-directed medical therapy” (GDMT) to emphasize the smaller set of recommendations that constitute optimal medical therapy for HF patients. This designation, encompassing primarily Class I recommendations, helps providers rapidly determine the optimal treatment course for an individual patient. The mainstay of GDMT in HFrEF patients remains angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) when ACE-I-intolerant, beta-blockers, and, in select patients, AA, hydralazine-nitrates, and diuretics.

A major shift in focus is seen in the new guideline with a greater emphasis on improved patient-centered outcomes across the spectrum of the disease. HF requires a continuum of care, from screening and genetic testing of family members of patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy to conversations about palliative care and hospice. To this end, the authors highlight quality of life, shared decision-making, care coordination, transitions of care, and appropriateness of palliative care in a chronic disease state.

Further, the guideline expands upon previous recommendations for compliance with performance and quality metrics. Quality of care and adherence to performance measures of HF patients are becoming increasingly recognized, particularly in the hospital setting. The guideline offers recommendations for transitions of care in the hospitalized patient, which utilize systems of care coordination to ensure an evidence-based plan of care that includes the achievement of GDMT goals, effective management of comorbid conditions, timely follow-up, and appropriate dietary and physical activities.

HM Takeaways

HF is one of the most common, most challenging diseases managed by hospitalists. The 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of HF, while providing a comprehensive summary of evidence with recommendations for the totality of care for these patients throughout the course of the disease, places heavy emphasis on management during hospitalization and transitions. This includes repositioning of performance measures involving GDMT to better ensure optimal use of proven therapies in HFrEF, evidence-based steps to reduce readmissions, and greater recognition of the role of palliative care for patients with advanced disease.

Drs. McIlvennan and Allen are cardiologists in the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. Dr. Allen also works in the Colorado Health Outcomes Program.

References available at the-hospitalist.org.