User login

Prospective cohort study of hospitalized adults with advanced cancer: Associations between complications, comorbidity, and utilization

Of the major chronic conditions that affect adult patients in the United States, cancer accounts for the highest levels of per capita spending.1 Cost growth for cancer treatment has been substantial and persistent, from $72 billion in 2004 to $125 billion in 2010, and is projected to increase to $173 billion by 2020.2 Thirty-five percent of US direct medical cancer costs are attributable to inpatient hospital stays.3 Policy responses that can provide financially sustainable, high-quality models of care for patients with advanced cancer and other serious illness are urgently sought.4-7

Patterns and levels of resource utilization in providing healthcare to patients with serious illness reflect not only treatment choices but a complex set of relationships among demographic, clinical, and system factors.8-10 Patient-level factors previously identified as potentially significant drivers of resource utilization among cancer populations specifically include age,11 sex,12 primary diagnosis,13 and comorbidities.11 Among end-of-life populations, significant associations have been found between cost and ethnicity,14 socioeconomic status,15 advance directive status,16 insurance status,16 and functional status.17

Evidence on factors strongly associated with cost of hospital admission for patients with advanced cancer can therefore inform provision and planning of healthcare. For example, when a specific diagnosis or clinical condition is found to be associated with high cost, then improving coordination and provision of care for this patient group may reduce avoidable utilization. Determining associations between sociodemographics and hospital care cost can help in identifying possible disparities in care, such as those that might occur when care differs by race, class, or insurance status.

We conducted the Palliative Care for Cancer (PC4C) study, a prospective multisite cohort study of the palliative care consultation team intervention for hospitalized adults with advanced cancer.18,19 In our primary analysis, we controlled for receipt of palliative care and analyzed a rich patient-reported dataset to examine associations between hospital care cost, and sociodemographic factors, clinical variables, and prior healthcare utilization. The results provide evidence regarding the factors most associated with the cost of hospital-based cancer care.

METHODS

Design, Setting, Participants, Data Sources

The PC4C study has been described in detail by authors who estimated the impact of specialist palliative care consultation teams on hospitalization cost.19-21 We prospectively collected sociodemographic, clinical, prior utilization, and cost data for adult patients with a primary diagnosis of advanced cancer admitted to 4 large US hospitals between 2007 and 2011.

All 4 of these high-volume tertiary-care medical centers were selected for their high patient volume (to facilitate sample size) and research capacity (to facilitate proficient recruitment and data collection). Before the study was initiated, it was approved by the institutional review board of each facility. In addition, approval was sought from each attending physician at each hospital site; patients whose physician did not grant approval were not considered for enrollment. More than 95% of physicians gave their approval.

Patients were at least 18 years old and had a primary diagnosis of metastatic solid tumor; central nervous system malignancy; locally advanced head, neck, or pancreas cancer; metastatic melanoma; or transplant-ineligible lymphoma or multiple myeloma. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, had a diagnosis of dementia, were unresponsive or nonverbal, had been admitted for routine chemotherapy, died or were discharged within 48 hours of admission, or had had a previous palliative care consultation.

Eligible patients were identified through daily review of admissions records and administrative databases. For each potential study patient identified, that patient’s bedside nurse inquired about willingness to participate in the study. Then, for each willing patient, a trained clinical interviewer approached to explain the study and obtain informed consent. With the patient’s consent, family members were also approached and enrolled with written informed consent.

Quantitative Variables

Independent variables. In the dataset, we identified 17 patient-level variables we hypothesized could be significantly associated with hospitalization cost. These variables covered 4 domains:

- Demographics: age, sex, race.

- Socioeconomics/systems: education level, insurance status, presence of advance directive (living will or healthcare proxy).

- Clinical care: primary cancer diagnosis, admitting diagnosis, comorbidities (Elixhauser index22), symptom burden and severity (Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [CMSAS]23), and activities of daily living24 or presence of a hospital-acquired condition or complication.25

- Prior utilization: visiting homecare nurse and home health aide within 2 weeks before admission, and analgesic use in morphine sulfate equivalents within week before admission.

Data were collected through a combination of medical record review (age, sex, diagnoses, comorbidities, complications), patient interview (race, education, advance directive, CMSAS, activities of daily living, prior utilization), and hospital administrative databases (insurance). For use in regression, variables were divided into categories when appropriate. Table 1 lists these predictors and their prevalence in the analytic sample.

Dependent variable. The outcome of interest in this analysis was total direct cost of hospital stay. Direct costs are those attributable to the care of a specific patient, as distinct from indirect costs, the shared overhead costs of running a hospital.26 Cost data were extracted from hospital accounting databases and therefore reflect actual costs, the US dollar cost to the hospitals of care provided, also known as direct measurement.27 Costs were standardized for geographical region using the Medicare Wage Index28 and year using the Consumer Price Index29 and are presented here in US dollars for 2011, the final year of data collection.

Statistical Methods

Primary analyses. We regressed total direct hospital costs against all predictors listed in Table 1. To control for receipt of palliative care, we used additional independent variables—a fixed-effects variable for each of 3 hospitals (the fourth hospital was used as the reference case) and a binary treatment variable (whether or not the patient was seen by a palliative care consultation team within 2 days of hospital admission).19,20

Associations between cost and patient-level covariates were derived with use of a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link,30 selected after comparative evaluation of performance for multiple linear and nonlinear modeling options.31

For each patient-level covariate, we estimated average marginal effects. For continuous variables, we estimated the marginal increase in cost associated with a 1-unit increase in the variable. For binary variables, we estimated the average incremental effect, the increase in cost associated with a move from the reference group, holding all other covariates to their original values. All analyses were performed with Stata Version 12.32

Secondary analyses. Primary analyses showed that number of patient comorbidities (Elixhauser index) was strongly associated with complications and comorbidity count. Prior analyses with these data have shown that palliative care had a larger cost-saving effect for patients with a larger number of comorbidities.20 Additional analyses were therefore performed to examine associations between complications, utilization, and palliative care. First, we cross-tabulated the sample by complications status (none; minor or major) and receipt of timely palliative care, and we present their summary utilization data. Second, we estimated the effect for each complications stratum (none; minor or major) of receiving timely palliative care on cost. These estimates are calculated consistent with prior work with these data: We used propensity scores to balance patients who received the treatment (palliative care) with patients who did not (usual care only),33,34 and we used a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link to regress the direct hospital care cost on the binary treatment variable and all predictors listed in Table 1.19-21

RESULTS

Participants

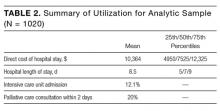

We have previously detailed that in our study there were 1023 patients eligible for cost analysis,19 of whom three were missing data in a field in Table 1 and excluded from this paper. The final analytic sample (N = 1020) is presented according to baseline covariates in Table 1 and according to summary utilization measures in Table 2.

Main Results

The results of the primary analysis, estimating the association between patient-level factors and cost of hospitalization, are presented in Table 3.

These results show the evidence of an association with cost is strongest for 3 clinical factors: a major complication (+$8267; 95% confidence interval [CI], $4509-$12,025), a minor but not a major complication (+$5289; CI, $3480-$7097), and number of comorbidities (+$852; CI, $550-$1153). In addition, there is evidence of associations between lower cost and admitting diagnosis of electrolyte disorders (–$4759; CI, –$7928 to –$1590) and older age (–$53; CI, –$99 to –$6). There is no significant association between primary diagnosis, symptom burden or other clinical factors, sociodemographic factors or healthcare utilization prior to admission and direct hospitalization costs.

Results of the secondary analyses of associations between complications, utilization, and palliative care are listed in Table 4. Patients are stratified by complication (none; major | minor) and their direct cost of hospital care and hospital length of stay (LOS) presented by treatment group (palliative care; usual care only). The data show that within each strata patients who received palliative care had lower costs and LOS than those who received usual care only. Estimated effects of palliative care on utilization is found to be statistically significant in all four quadrants, with a larger cost-effect in the complications stratum than the non-complications stratum.

Sensitivity Analysis

Fifty-one patients died during admission. After removing these cases, because of concerns about possible unobserved heterogeneity,35 we checked our primary (Table 3) and secondary (Table 4) results. Patients discharged alive had results substantively similar to those of the entire sample.

DISCUSSION

Results from our primary analysis (Table 3) suggest that complications and number of comorbidities are the key drivers of hospitalization cost for adults with advanced cancer. Hospitalization for electrolyte disorders and age are both negatively associated with cost.

The association found between higher cost and hospital-acquired complications (HACs) is consistent with other studies’ finding that HACs often result in higher cost, longer LOS, and increased inhospital mortality.36 Since those studies were reported, policy attention has been increasingly focused on HACs.37 Our findings are notable in that, though prior evidence has also suggested high hospital cost is multifactorial, driven by a diversity of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors, this rich patient-reported dataset suggests that, compared with other variables, HACs are emphatically the largest driver of cost. Moreover, cancer patients typically are a vulnerable population, more prone to complications and thus also to potentially avoidable treatments and higher cost. Our prior work suggested earlier palliative care consultation can reduce cost, in part by shortening LOS and reducing the opportunity for HACs to develop19,20; our secondary analysis (Table 4) suggested a palliative care team’s involvement in HAC treatment can significantly reduce cost of care as well. These associations possibly derive from changed treatment choices and shorter LOS. Further work is needed to better elucidate the role of palliative care in the prevention of HACs in seriously ill patients.

That the number of comorbidities was found to be a key driver of hospitalization cost is consistent with recent findings that high spending on seriously ill patients is associated with having multiple chronic conditions rather than any specific primary diagnosis.38,39 It is important to note that, unlike impending complications, serious chronic conditions generally are known at admission and can be addressed prospectively through provision and policy. A prior analysis with these data found that palliative care consultation was more cost-effective for patients with a larger number of comorbidities.20 Our 2 studies together suggest that, notwithstanding the preferable alternative of avoiding hospitalization entirely, palliative care and other skilled coordination of care services ought to be prioritized for inpatients with multiple serious illnesses and the highest medical complexity. This patient group has both the highest costs and the greatest amenability to skilled transdisciplinary intervention, possibly because multiple chronic conditions affect patients interactively, complicating identification of appropriate polypharmacy responses and prioritization of treatments.

Our findings also may help direct appropriate use of palliative care services. The recently published American Society of Clinical Oncology palliative care guidelines note that all patients with advanced cancer (eg, those enrolled in our study) should receive dedicated palliative care services, early in the disease course, concurrent with active treatment.40 Workforce estimates suggest that the current and future numbers of palliative care practitioners will be unable to meet the ASCO recommendations alone never mind patients with other serious illnesses (eg, advanced heart failure, COPD, CKD).41 As such, specialized palliative care services will need to be targeted to the patient populations that can benefit most from these services. Whereas cost should not be the principle driver specialized palliative care provision, it will likely be an important component due to both the necessity of allocating scarce resources in the most effective way and the evidence that in care of the seriously-ill lower costs are often a proxy for improved patient experience.

These findings also have implications for research: Different conditions and presumably different combinations of conditions have very different implications for hospital care costs for a cohort of adults with advanced cancer. Given the increasing number of co-occurring conditions among seriously ill patients, and the increasing costs of cancer care and of treating multimorbidity cases, it is essential to further our understanding of the relationship between comorbidities and costs in order to plan and finance care for advanced cancer patients.

Limitations and Generalizability

In this observational study, reported associations may be attributable to unobserved confounding that our analyses failed to control.

Our results reflect associations in a prospective multisite study of advanced cancer patients hospitalized in the United States. It is not clear how generalizable our findings are to patients without cancer, to patients in nonhospital settings, and to patients in other health systems and countries. Analyzing cost from the hospital perspective does not take into account that the most impactful way to reduce cost is to avoid hospitalization entirely.

Results of our secondary analysis will not necessarily be robust to patient groups, as specific weights likely will vary by sample. The idea that costs vary by condition, however, is important nevertheless. Elixhauser total was derived with use of the enhanced ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) algorithm from Quan et al.42 and does not include subsequent Elixhauser Comorbidity Software updates recommended by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).43 The Elixhauser index is recommended over Charlson and other comorbidity indices by both HCUP45 and a recent systematic review.44

One possible unobserved factor is prior chemotherapy, which is associated with increased hospitalization risk. Related factors that are somewhat controlled for in the study include cancer stage (advanced cancer was an eligibility criterion) and receipt of analgesics within the week before admission (patients admitted for routine chemotherapy were excluded from analyses at the outset).

CONCLUSION

Other studies have identified a wide range of sociodemographic, clinical, and health system factors associated with healthcare utilization. Our results suggest that, for cost of hospital admission among adults with advanced cancer, the most important drivers of utilization are complications and comorbidities. Hospital costs for patients with advanced cancer constitute a major part of US healthcare spending, and these results suggest the need to prioritize high-quality, cost-effective care for patients with multiple serious illnesses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Arnold, Phil Santa Emma, Mary Beth Happ, Tim Smith, and David Weissman for contributing to the Palliative Care for Cancer (PC4C) project.

Disclosure

The study was funded by grant R01 CA116227 from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research. The study sponsors had no role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. All authors are independent of the study sponsors. Dr. May was supported by a HRB/NCI Health Economics Fellowship during this work. Dr. Garrido is supported by a Veterans Affairs HSR&D career development award (CDA 11-201/CDP 12-255). Dr. Kelley’s time was funded by the National Institute on Aging (1K23AG040774-01A1) and the American Federation for Aging. Dr. Smith is funded by the NCI Core Grant P 30 006973, 1-R01 CA177562-01A1, 1-R01 NR014050 01, and the Harry J. Duffey Family Endowment for Palliative Care. Dr. Morrison was the recipient of a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (5K24AG022345) during the course of this work. This work was supported by the NIA, Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai [5P30AG028741], and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

1. Soni A. Top 10 Most Costly Conditions Among Men and Women, 2008: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Adult Population, Age 18 and Older. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

2. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128. PubMed

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2015.

4. Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2060-2065. PubMed

5. Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine/National Academies Press; 2013. PubMed

7. Anderson GF. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010.

8. Tibi-Levy Y, Le Vaillant M, de Pouvourville G. Determinants of resource utilization in four palliative care units. Palliat Med. 2006;20(2):95-106. PubMed

9. Simoens S, Kutten B, Keirse E, et al. The costs of treating terminal patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(3):436-448. PubMed

10. Groeneveld I, Murtagh F, Kaloki Y, Bausewein C, Higginson I. Determinants of healthcare costs in the last year of life. Annual Assembly of American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine & Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association; March 14, 2013; New Orleans, LA.

11. Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures at the end of life for colorectal cancer decedents. J Womens Health. 2007;16(2):214-227. PubMed

12. Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures and service utilization at the end of life for lung cancer decedents. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(3):199-209. PubMed

13. Walker H, Anderson M, Farahati F, et al. Resource use and costs of end-of-life/palliative care: Ontario adult cancer patients dying during 2002 and 2003. J Palliat Care. 2011;27(2):79-88. PubMed

14. Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):493-501. PubMed

15. Hanratty B, Burstrom B, Walander A, Whitehead M. Inequality in the face of death? Public expenditure on health care for different socioeconomic groups in the last year of life. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(2):90-94. PubMed

16. Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(4):235-242. PubMed

17. Guerriere DN, Zagorski B, Fassbender K, Masucci L, Librach L, Coyte PC. Cost variations in ambulatory and home-based palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24(5):523-532. PubMed

18. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Palliative Care for Hospitalized Cancer Patients [project information]. Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2006. Project 5R01CA116227-04. https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?projectnumber=5R01CA116227-04. Published 2006. Accessed August 1, 2015.

19. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2745-2752. PubMed

20. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):44-53. PubMed

21. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Morrison RS, Normand C. Using length of stay to control for unobserved heterogeneity when estimating treatment effect on hospital costs with observational data: issues of reliability, robustness and usefulness. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(5):2020-2043. PubMed

22. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. PubMed

23. Chang VT, Hwang SS, Kasimis B, Thaler HT. Shorter symptom assessment instruments: the Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (CMSAS). Cancer Invest. 2004;22(4):526-536. PubMed

24. Katz S, Ford A, Moskowitz R, Jackson B, Jaffe M. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychological function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919. PubMed

25. McLaughlin MA, Orosz GM, Magaziner J, et al. Preoperative status and risk of complications in patients with hip fracture. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):219-225. PubMed

26. Taheri PA, Butz D, Griffes LC, Morlock DR, Greenfield LJ. Physician impact on the total cost of care. Ann Surg. 2000;231(3):432-435. PubMed

27. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Economics Resource Center. Determining costs. Washington, DC: US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Health Economics Resource Center; 2016. http://www.herc.research.va.gov/include/page.asp?id=determining-costs. Published 2016. Accessed September 7, 2016.

28. US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. FY 2011 Wage Index [Table 2]. Baltimore, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2011. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Wage-Index-Files-Items/CMS1234173.html. Published 2011. Accessed September 2, 2014.

29. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. All Urban Consumers (Current Series) [Consumer Price Index database]. US Dept of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2015. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2016.

30. Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24(3):465-488. PubMed

31. Jones AM, Rice N, Bago d’Uva T, Balia S. Applied Health Economics. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Routledge; 2013.

32. Stata [computer program]. Version 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2011.

33. Garrido MM, Kelley AS, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing

propensity scores. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1701-1720. PubMed

34. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna,

Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016.

35. Cassel JB, Kerr K, Pantilat S, Smith TJ. Palliative care consultation and hospital

length of stay. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(6):761-767. PubMed

36. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality. Efforts to Improve Patient Safety Result in 1.3 Million Fewer Patient

Harms: Interim Update on 2013 Annual Hospital-Acquired Condition Rate and

Estimates of Cost Savings and Deaths Averted From 2010 to 2013. Rockville,

MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality; 2015. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/pfp/

interimhacrate2013.html. Published 2015. Updated November 2015. Accessed

November 18, 2016.

37. Cassidy A. Health Policy Brief: Medicare’s Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction

Program. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_

id=142. Published August 6, 2015. Accessed April 24, 2017.

38. Davis MA, Nallamothu BK, Banerjee M, Bynum JP. Identification of four unique

spending patterns among older adults in the last year of life challenges standard

assumptions. Health Aff. 2016;35(7):1316-1323. PubMed

39. Aldridge MD, Kelley AS. The myth regarding the high cost of end-of-life care.

Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2411-2415. PubMed

40. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard

oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline

update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112. PubMed

41. Spetz J, Dudley N, Trupin L, Rogers M, Meier DE, Dumanovsky T. Few hospital

palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff.

2016;35(9):1690-1697. PubMed

42. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities

in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. PubMed

43. HCUP [Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project] Elixhauser Comorbidity Software

[computer program]. Version 3.7. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality; 2016. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/

comorbidity.jsp. Published 2016. Accessed November 9, 2016.

44. Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for

administrative data. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1109-1118. PubMed

Of the major chronic conditions that affect adult patients in the United States, cancer accounts for the highest levels of per capita spending.1 Cost growth for cancer treatment has been substantial and persistent, from $72 billion in 2004 to $125 billion in 2010, and is projected to increase to $173 billion by 2020.2 Thirty-five percent of US direct medical cancer costs are attributable to inpatient hospital stays.3 Policy responses that can provide financially sustainable, high-quality models of care for patients with advanced cancer and other serious illness are urgently sought.4-7

Patterns and levels of resource utilization in providing healthcare to patients with serious illness reflect not only treatment choices but a complex set of relationships among demographic, clinical, and system factors.8-10 Patient-level factors previously identified as potentially significant drivers of resource utilization among cancer populations specifically include age,11 sex,12 primary diagnosis,13 and comorbidities.11 Among end-of-life populations, significant associations have been found between cost and ethnicity,14 socioeconomic status,15 advance directive status,16 insurance status,16 and functional status.17

Evidence on factors strongly associated with cost of hospital admission for patients with advanced cancer can therefore inform provision and planning of healthcare. For example, when a specific diagnosis or clinical condition is found to be associated with high cost, then improving coordination and provision of care for this patient group may reduce avoidable utilization. Determining associations between sociodemographics and hospital care cost can help in identifying possible disparities in care, such as those that might occur when care differs by race, class, or insurance status.

We conducted the Palliative Care for Cancer (PC4C) study, a prospective multisite cohort study of the palliative care consultation team intervention for hospitalized adults with advanced cancer.18,19 In our primary analysis, we controlled for receipt of palliative care and analyzed a rich patient-reported dataset to examine associations between hospital care cost, and sociodemographic factors, clinical variables, and prior healthcare utilization. The results provide evidence regarding the factors most associated with the cost of hospital-based cancer care.

METHODS

Design, Setting, Participants, Data Sources

The PC4C study has been described in detail by authors who estimated the impact of specialist palliative care consultation teams on hospitalization cost.19-21 We prospectively collected sociodemographic, clinical, prior utilization, and cost data for adult patients with a primary diagnosis of advanced cancer admitted to 4 large US hospitals between 2007 and 2011.

All 4 of these high-volume tertiary-care medical centers were selected for their high patient volume (to facilitate sample size) and research capacity (to facilitate proficient recruitment and data collection). Before the study was initiated, it was approved by the institutional review board of each facility. In addition, approval was sought from each attending physician at each hospital site; patients whose physician did not grant approval were not considered for enrollment. More than 95% of physicians gave their approval.

Patients were at least 18 years old and had a primary diagnosis of metastatic solid tumor; central nervous system malignancy; locally advanced head, neck, or pancreas cancer; metastatic melanoma; or transplant-ineligible lymphoma or multiple myeloma. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, had a diagnosis of dementia, were unresponsive or nonverbal, had been admitted for routine chemotherapy, died or were discharged within 48 hours of admission, or had had a previous palliative care consultation.

Eligible patients were identified through daily review of admissions records and administrative databases. For each potential study patient identified, that patient’s bedside nurse inquired about willingness to participate in the study. Then, for each willing patient, a trained clinical interviewer approached to explain the study and obtain informed consent. With the patient’s consent, family members were also approached and enrolled with written informed consent.

Quantitative Variables

Independent variables. In the dataset, we identified 17 patient-level variables we hypothesized could be significantly associated with hospitalization cost. These variables covered 4 domains:

- Demographics: age, sex, race.

- Socioeconomics/systems: education level, insurance status, presence of advance directive (living will or healthcare proxy).

- Clinical care: primary cancer diagnosis, admitting diagnosis, comorbidities (Elixhauser index22), symptom burden and severity (Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [CMSAS]23), and activities of daily living24 or presence of a hospital-acquired condition or complication.25

- Prior utilization: visiting homecare nurse and home health aide within 2 weeks before admission, and analgesic use in morphine sulfate equivalents within week before admission.

Data were collected through a combination of medical record review (age, sex, diagnoses, comorbidities, complications), patient interview (race, education, advance directive, CMSAS, activities of daily living, prior utilization), and hospital administrative databases (insurance). For use in regression, variables were divided into categories when appropriate. Table 1 lists these predictors and their prevalence in the analytic sample.

Dependent variable. The outcome of interest in this analysis was total direct cost of hospital stay. Direct costs are those attributable to the care of a specific patient, as distinct from indirect costs, the shared overhead costs of running a hospital.26 Cost data were extracted from hospital accounting databases and therefore reflect actual costs, the US dollar cost to the hospitals of care provided, also known as direct measurement.27 Costs were standardized for geographical region using the Medicare Wage Index28 and year using the Consumer Price Index29 and are presented here in US dollars for 2011, the final year of data collection.

Statistical Methods

Primary analyses. We regressed total direct hospital costs against all predictors listed in Table 1. To control for receipt of palliative care, we used additional independent variables—a fixed-effects variable for each of 3 hospitals (the fourth hospital was used as the reference case) and a binary treatment variable (whether or not the patient was seen by a palliative care consultation team within 2 days of hospital admission).19,20

Associations between cost and patient-level covariates were derived with use of a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link,30 selected after comparative evaluation of performance for multiple linear and nonlinear modeling options.31

For each patient-level covariate, we estimated average marginal effects. For continuous variables, we estimated the marginal increase in cost associated with a 1-unit increase in the variable. For binary variables, we estimated the average incremental effect, the increase in cost associated with a move from the reference group, holding all other covariates to their original values. All analyses were performed with Stata Version 12.32

Secondary analyses. Primary analyses showed that number of patient comorbidities (Elixhauser index) was strongly associated with complications and comorbidity count. Prior analyses with these data have shown that palliative care had a larger cost-saving effect for patients with a larger number of comorbidities.20 Additional analyses were therefore performed to examine associations between complications, utilization, and palliative care. First, we cross-tabulated the sample by complications status (none; minor or major) and receipt of timely palliative care, and we present their summary utilization data. Second, we estimated the effect for each complications stratum (none; minor or major) of receiving timely palliative care on cost. These estimates are calculated consistent with prior work with these data: We used propensity scores to balance patients who received the treatment (palliative care) with patients who did not (usual care only),33,34 and we used a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link to regress the direct hospital care cost on the binary treatment variable and all predictors listed in Table 1.19-21

RESULTS

Participants

We have previously detailed that in our study there were 1023 patients eligible for cost analysis,19 of whom three were missing data in a field in Table 1 and excluded from this paper. The final analytic sample (N = 1020) is presented according to baseline covariates in Table 1 and according to summary utilization measures in Table 2.

Main Results

The results of the primary analysis, estimating the association between patient-level factors and cost of hospitalization, are presented in Table 3.

These results show the evidence of an association with cost is strongest for 3 clinical factors: a major complication (+$8267; 95% confidence interval [CI], $4509-$12,025), a minor but not a major complication (+$5289; CI, $3480-$7097), and number of comorbidities (+$852; CI, $550-$1153). In addition, there is evidence of associations between lower cost and admitting diagnosis of electrolyte disorders (–$4759; CI, –$7928 to –$1590) and older age (–$53; CI, –$99 to –$6). There is no significant association between primary diagnosis, symptom burden or other clinical factors, sociodemographic factors or healthcare utilization prior to admission and direct hospitalization costs.

Results of the secondary analyses of associations between complications, utilization, and palliative care are listed in Table 4. Patients are stratified by complication (none; major | minor) and their direct cost of hospital care and hospital length of stay (LOS) presented by treatment group (palliative care; usual care only). The data show that within each strata patients who received palliative care had lower costs and LOS than those who received usual care only. Estimated effects of palliative care on utilization is found to be statistically significant in all four quadrants, with a larger cost-effect in the complications stratum than the non-complications stratum.

Sensitivity Analysis

Fifty-one patients died during admission. After removing these cases, because of concerns about possible unobserved heterogeneity,35 we checked our primary (Table 3) and secondary (Table 4) results. Patients discharged alive had results substantively similar to those of the entire sample.

DISCUSSION

Results from our primary analysis (Table 3) suggest that complications and number of comorbidities are the key drivers of hospitalization cost for adults with advanced cancer. Hospitalization for electrolyte disorders and age are both negatively associated with cost.

The association found between higher cost and hospital-acquired complications (HACs) is consistent with other studies’ finding that HACs often result in higher cost, longer LOS, and increased inhospital mortality.36 Since those studies were reported, policy attention has been increasingly focused on HACs.37 Our findings are notable in that, though prior evidence has also suggested high hospital cost is multifactorial, driven by a diversity of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors, this rich patient-reported dataset suggests that, compared with other variables, HACs are emphatically the largest driver of cost. Moreover, cancer patients typically are a vulnerable population, more prone to complications and thus also to potentially avoidable treatments and higher cost. Our prior work suggested earlier palliative care consultation can reduce cost, in part by shortening LOS and reducing the opportunity for HACs to develop19,20; our secondary analysis (Table 4) suggested a palliative care team’s involvement in HAC treatment can significantly reduce cost of care as well. These associations possibly derive from changed treatment choices and shorter LOS. Further work is needed to better elucidate the role of palliative care in the prevention of HACs in seriously ill patients.

That the number of comorbidities was found to be a key driver of hospitalization cost is consistent with recent findings that high spending on seriously ill patients is associated with having multiple chronic conditions rather than any specific primary diagnosis.38,39 It is important to note that, unlike impending complications, serious chronic conditions generally are known at admission and can be addressed prospectively through provision and policy. A prior analysis with these data found that palliative care consultation was more cost-effective for patients with a larger number of comorbidities.20 Our 2 studies together suggest that, notwithstanding the preferable alternative of avoiding hospitalization entirely, palliative care and other skilled coordination of care services ought to be prioritized for inpatients with multiple serious illnesses and the highest medical complexity. This patient group has both the highest costs and the greatest amenability to skilled transdisciplinary intervention, possibly because multiple chronic conditions affect patients interactively, complicating identification of appropriate polypharmacy responses and prioritization of treatments.

Our findings also may help direct appropriate use of palliative care services. The recently published American Society of Clinical Oncology palliative care guidelines note that all patients with advanced cancer (eg, those enrolled in our study) should receive dedicated palliative care services, early in the disease course, concurrent with active treatment.40 Workforce estimates suggest that the current and future numbers of palliative care practitioners will be unable to meet the ASCO recommendations alone never mind patients with other serious illnesses (eg, advanced heart failure, COPD, CKD).41 As such, specialized palliative care services will need to be targeted to the patient populations that can benefit most from these services. Whereas cost should not be the principle driver specialized palliative care provision, it will likely be an important component due to both the necessity of allocating scarce resources in the most effective way and the evidence that in care of the seriously-ill lower costs are often a proxy for improved patient experience.

These findings also have implications for research: Different conditions and presumably different combinations of conditions have very different implications for hospital care costs for a cohort of adults with advanced cancer. Given the increasing number of co-occurring conditions among seriously ill patients, and the increasing costs of cancer care and of treating multimorbidity cases, it is essential to further our understanding of the relationship between comorbidities and costs in order to plan and finance care for advanced cancer patients.

Limitations and Generalizability

In this observational study, reported associations may be attributable to unobserved confounding that our analyses failed to control.

Our results reflect associations in a prospective multisite study of advanced cancer patients hospitalized in the United States. It is not clear how generalizable our findings are to patients without cancer, to patients in nonhospital settings, and to patients in other health systems and countries. Analyzing cost from the hospital perspective does not take into account that the most impactful way to reduce cost is to avoid hospitalization entirely.

Results of our secondary analysis will not necessarily be robust to patient groups, as specific weights likely will vary by sample. The idea that costs vary by condition, however, is important nevertheless. Elixhauser total was derived with use of the enhanced ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) algorithm from Quan et al.42 and does not include subsequent Elixhauser Comorbidity Software updates recommended by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).43 The Elixhauser index is recommended over Charlson and other comorbidity indices by both HCUP45 and a recent systematic review.44

One possible unobserved factor is prior chemotherapy, which is associated with increased hospitalization risk. Related factors that are somewhat controlled for in the study include cancer stage (advanced cancer was an eligibility criterion) and receipt of analgesics within the week before admission (patients admitted for routine chemotherapy were excluded from analyses at the outset).

CONCLUSION

Other studies have identified a wide range of sociodemographic, clinical, and health system factors associated with healthcare utilization. Our results suggest that, for cost of hospital admission among adults with advanced cancer, the most important drivers of utilization are complications and comorbidities. Hospital costs for patients with advanced cancer constitute a major part of US healthcare spending, and these results suggest the need to prioritize high-quality, cost-effective care for patients with multiple serious illnesses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Arnold, Phil Santa Emma, Mary Beth Happ, Tim Smith, and David Weissman for contributing to the Palliative Care for Cancer (PC4C) project.

Disclosure

The study was funded by grant R01 CA116227 from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research. The study sponsors had no role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. All authors are independent of the study sponsors. Dr. May was supported by a HRB/NCI Health Economics Fellowship during this work. Dr. Garrido is supported by a Veterans Affairs HSR&D career development award (CDA 11-201/CDP 12-255). Dr. Kelley’s time was funded by the National Institute on Aging (1K23AG040774-01A1) and the American Federation for Aging. Dr. Smith is funded by the NCI Core Grant P 30 006973, 1-R01 CA177562-01A1, 1-R01 NR014050 01, and the Harry J. Duffey Family Endowment for Palliative Care. Dr. Morrison was the recipient of a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (5K24AG022345) during the course of this work. This work was supported by the NIA, Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai [5P30AG028741], and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Of the major chronic conditions that affect adult patients in the United States, cancer accounts for the highest levels of per capita spending.1 Cost growth for cancer treatment has been substantial and persistent, from $72 billion in 2004 to $125 billion in 2010, and is projected to increase to $173 billion by 2020.2 Thirty-five percent of US direct medical cancer costs are attributable to inpatient hospital stays.3 Policy responses that can provide financially sustainable, high-quality models of care for patients with advanced cancer and other serious illness are urgently sought.4-7

Patterns and levels of resource utilization in providing healthcare to patients with serious illness reflect not only treatment choices but a complex set of relationships among demographic, clinical, and system factors.8-10 Patient-level factors previously identified as potentially significant drivers of resource utilization among cancer populations specifically include age,11 sex,12 primary diagnosis,13 and comorbidities.11 Among end-of-life populations, significant associations have been found between cost and ethnicity,14 socioeconomic status,15 advance directive status,16 insurance status,16 and functional status.17

Evidence on factors strongly associated with cost of hospital admission for patients with advanced cancer can therefore inform provision and planning of healthcare. For example, when a specific diagnosis or clinical condition is found to be associated with high cost, then improving coordination and provision of care for this patient group may reduce avoidable utilization. Determining associations between sociodemographics and hospital care cost can help in identifying possible disparities in care, such as those that might occur when care differs by race, class, or insurance status.

We conducted the Palliative Care for Cancer (PC4C) study, a prospective multisite cohort study of the palliative care consultation team intervention for hospitalized adults with advanced cancer.18,19 In our primary analysis, we controlled for receipt of palliative care and analyzed a rich patient-reported dataset to examine associations between hospital care cost, and sociodemographic factors, clinical variables, and prior healthcare utilization. The results provide evidence regarding the factors most associated with the cost of hospital-based cancer care.

METHODS

Design, Setting, Participants, Data Sources

The PC4C study has been described in detail by authors who estimated the impact of specialist palliative care consultation teams on hospitalization cost.19-21 We prospectively collected sociodemographic, clinical, prior utilization, and cost data for adult patients with a primary diagnosis of advanced cancer admitted to 4 large US hospitals between 2007 and 2011.

All 4 of these high-volume tertiary-care medical centers were selected for their high patient volume (to facilitate sample size) and research capacity (to facilitate proficient recruitment and data collection). Before the study was initiated, it was approved by the institutional review board of each facility. In addition, approval was sought from each attending physician at each hospital site; patients whose physician did not grant approval were not considered for enrollment. More than 95% of physicians gave their approval.

Patients were at least 18 years old and had a primary diagnosis of metastatic solid tumor; central nervous system malignancy; locally advanced head, neck, or pancreas cancer; metastatic melanoma; or transplant-ineligible lymphoma or multiple myeloma. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, had a diagnosis of dementia, were unresponsive or nonverbal, had been admitted for routine chemotherapy, died or were discharged within 48 hours of admission, or had had a previous palliative care consultation.

Eligible patients were identified through daily review of admissions records and administrative databases. For each potential study patient identified, that patient’s bedside nurse inquired about willingness to participate in the study. Then, for each willing patient, a trained clinical interviewer approached to explain the study and obtain informed consent. With the patient’s consent, family members were also approached and enrolled with written informed consent.

Quantitative Variables

Independent variables. In the dataset, we identified 17 patient-level variables we hypothesized could be significantly associated with hospitalization cost. These variables covered 4 domains:

- Demographics: age, sex, race.

- Socioeconomics/systems: education level, insurance status, presence of advance directive (living will or healthcare proxy).

- Clinical care: primary cancer diagnosis, admitting diagnosis, comorbidities (Elixhauser index22), symptom burden and severity (Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [CMSAS]23), and activities of daily living24 or presence of a hospital-acquired condition or complication.25

- Prior utilization: visiting homecare nurse and home health aide within 2 weeks before admission, and analgesic use in morphine sulfate equivalents within week before admission.

Data were collected through a combination of medical record review (age, sex, diagnoses, comorbidities, complications), patient interview (race, education, advance directive, CMSAS, activities of daily living, prior utilization), and hospital administrative databases (insurance). For use in regression, variables were divided into categories when appropriate. Table 1 lists these predictors and their prevalence in the analytic sample.

Dependent variable. The outcome of interest in this analysis was total direct cost of hospital stay. Direct costs are those attributable to the care of a specific patient, as distinct from indirect costs, the shared overhead costs of running a hospital.26 Cost data were extracted from hospital accounting databases and therefore reflect actual costs, the US dollar cost to the hospitals of care provided, also known as direct measurement.27 Costs were standardized for geographical region using the Medicare Wage Index28 and year using the Consumer Price Index29 and are presented here in US dollars for 2011, the final year of data collection.

Statistical Methods

Primary analyses. We regressed total direct hospital costs against all predictors listed in Table 1. To control for receipt of palliative care, we used additional independent variables—a fixed-effects variable for each of 3 hospitals (the fourth hospital was used as the reference case) and a binary treatment variable (whether or not the patient was seen by a palliative care consultation team within 2 days of hospital admission).19,20

Associations between cost and patient-level covariates were derived with use of a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link,30 selected after comparative evaluation of performance for multiple linear and nonlinear modeling options.31

For each patient-level covariate, we estimated average marginal effects. For continuous variables, we estimated the marginal increase in cost associated with a 1-unit increase in the variable. For binary variables, we estimated the average incremental effect, the increase in cost associated with a move from the reference group, holding all other covariates to their original values. All analyses were performed with Stata Version 12.32

Secondary analyses. Primary analyses showed that number of patient comorbidities (Elixhauser index) was strongly associated with complications and comorbidity count. Prior analyses with these data have shown that palliative care had a larger cost-saving effect for patients with a larger number of comorbidities.20 Additional analyses were therefore performed to examine associations between complications, utilization, and palliative care. First, we cross-tabulated the sample by complications status (none; minor or major) and receipt of timely palliative care, and we present their summary utilization data. Second, we estimated the effect for each complications stratum (none; minor or major) of receiving timely palliative care on cost. These estimates are calculated consistent with prior work with these data: We used propensity scores to balance patients who received the treatment (palliative care) with patients who did not (usual care only),33,34 and we used a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link to regress the direct hospital care cost on the binary treatment variable and all predictors listed in Table 1.19-21

RESULTS

Participants

We have previously detailed that in our study there were 1023 patients eligible for cost analysis,19 of whom three were missing data in a field in Table 1 and excluded from this paper. The final analytic sample (N = 1020) is presented according to baseline covariates in Table 1 and according to summary utilization measures in Table 2.

Main Results

The results of the primary analysis, estimating the association between patient-level factors and cost of hospitalization, are presented in Table 3.

These results show the evidence of an association with cost is strongest for 3 clinical factors: a major complication (+$8267; 95% confidence interval [CI], $4509-$12,025), a minor but not a major complication (+$5289; CI, $3480-$7097), and number of comorbidities (+$852; CI, $550-$1153). In addition, there is evidence of associations between lower cost and admitting diagnosis of electrolyte disorders (–$4759; CI, –$7928 to –$1590) and older age (–$53; CI, –$99 to –$6). There is no significant association between primary diagnosis, symptom burden or other clinical factors, sociodemographic factors or healthcare utilization prior to admission and direct hospitalization costs.

Results of the secondary analyses of associations between complications, utilization, and palliative care are listed in Table 4. Patients are stratified by complication (none; major | minor) and their direct cost of hospital care and hospital length of stay (LOS) presented by treatment group (palliative care; usual care only). The data show that within each strata patients who received palliative care had lower costs and LOS than those who received usual care only. Estimated effects of palliative care on utilization is found to be statistically significant in all four quadrants, with a larger cost-effect in the complications stratum than the non-complications stratum.

Sensitivity Analysis

Fifty-one patients died during admission. After removing these cases, because of concerns about possible unobserved heterogeneity,35 we checked our primary (Table 3) and secondary (Table 4) results. Patients discharged alive had results substantively similar to those of the entire sample.

DISCUSSION

Results from our primary analysis (Table 3) suggest that complications and number of comorbidities are the key drivers of hospitalization cost for adults with advanced cancer. Hospitalization for electrolyte disorders and age are both negatively associated with cost.

The association found between higher cost and hospital-acquired complications (HACs) is consistent with other studies’ finding that HACs often result in higher cost, longer LOS, and increased inhospital mortality.36 Since those studies were reported, policy attention has been increasingly focused on HACs.37 Our findings are notable in that, though prior evidence has also suggested high hospital cost is multifactorial, driven by a diversity of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors, this rich patient-reported dataset suggests that, compared with other variables, HACs are emphatically the largest driver of cost. Moreover, cancer patients typically are a vulnerable population, more prone to complications and thus also to potentially avoidable treatments and higher cost. Our prior work suggested earlier palliative care consultation can reduce cost, in part by shortening LOS and reducing the opportunity for HACs to develop19,20; our secondary analysis (Table 4) suggested a palliative care team’s involvement in HAC treatment can significantly reduce cost of care as well. These associations possibly derive from changed treatment choices and shorter LOS. Further work is needed to better elucidate the role of palliative care in the prevention of HACs in seriously ill patients.

That the number of comorbidities was found to be a key driver of hospitalization cost is consistent with recent findings that high spending on seriously ill patients is associated with having multiple chronic conditions rather than any specific primary diagnosis.38,39 It is important to note that, unlike impending complications, serious chronic conditions generally are known at admission and can be addressed prospectively through provision and policy. A prior analysis with these data found that palliative care consultation was more cost-effective for patients with a larger number of comorbidities.20 Our 2 studies together suggest that, notwithstanding the preferable alternative of avoiding hospitalization entirely, palliative care and other skilled coordination of care services ought to be prioritized for inpatients with multiple serious illnesses and the highest medical complexity. This patient group has both the highest costs and the greatest amenability to skilled transdisciplinary intervention, possibly because multiple chronic conditions affect patients interactively, complicating identification of appropriate polypharmacy responses and prioritization of treatments.

Our findings also may help direct appropriate use of palliative care services. The recently published American Society of Clinical Oncology palliative care guidelines note that all patients with advanced cancer (eg, those enrolled in our study) should receive dedicated palliative care services, early in the disease course, concurrent with active treatment.40 Workforce estimates suggest that the current and future numbers of palliative care practitioners will be unable to meet the ASCO recommendations alone never mind patients with other serious illnesses (eg, advanced heart failure, COPD, CKD).41 As such, specialized palliative care services will need to be targeted to the patient populations that can benefit most from these services. Whereas cost should not be the principle driver specialized palliative care provision, it will likely be an important component due to both the necessity of allocating scarce resources in the most effective way and the evidence that in care of the seriously-ill lower costs are often a proxy for improved patient experience.

These findings also have implications for research: Different conditions and presumably different combinations of conditions have very different implications for hospital care costs for a cohort of adults with advanced cancer. Given the increasing number of co-occurring conditions among seriously ill patients, and the increasing costs of cancer care and of treating multimorbidity cases, it is essential to further our understanding of the relationship between comorbidities and costs in order to plan and finance care for advanced cancer patients.

Limitations and Generalizability

In this observational study, reported associations may be attributable to unobserved confounding that our analyses failed to control.

Our results reflect associations in a prospective multisite study of advanced cancer patients hospitalized in the United States. It is not clear how generalizable our findings are to patients without cancer, to patients in nonhospital settings, and to patients in other health systems and countries. Analyzing cost from the hospital perspective does not take into account that the most impactful way to reduce cost is to avoid hospitalization entirely.

Results of our secondary analysis will not necessarily be robust to patient groups, as specific weights likely will vary by sample. The idea that costs vary by condition, however, is important nevertheless. Elixhauser total was derived with use of the enhanced ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) algorithm from Quan et al.42 and does not include subsequent Elixhauser Comorbidity Software updates recommended by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).43 The Elixhauser index is recommended over Charlson and other comorbidity indices by both HCUP45 and a recent systematic review.44

One possible unobserved factor is prior chemotherapy, which is associated with increased hospitalization risk. Related factors that are somewhat controlled for in the study include cancer stage (advanced cancer was an eligibility criterion) and receipt of analgesics within the week before admission (patients admitted for routine chemotherapy were excluded from analyses at the outset).

CONCLUSION

Other studies have identified a wide range of sociodemographic, clinical, and health system factors associated with healthcare utilization. Our results suggest that, for cost of hospital admission among adults with advanced cancer, the most important drivers of utilization are complications and comorbidities. Hospital costs for patients with advanced cancer constitute a major part of US healthcare spending, and these results suggest the need to prioritize high-quality, cost-effective care for patients with multiple serious illnesses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Arnold, Phil Santa Emma, Mary Beth Happ, Tim Smith, and David Weissman for contributing to the Palliative Care for Cancer (PC4C) project.

Disclosure

The study was funded by grant R01 CA116227 from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research. The study sponsors had no role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. All authors are independent of the study sponsors. Dr. May was supported by a HRB/NCI Health Economics Fellowship during this work. Dr. Garrido is supported by a Veterans Affairs HSR&D career development award (CDA 11-201/CDP 12-255). Dr. Kelley’s time was funded by the National Institute on Aging (1K23AG040774-01A1) and the American Federation for Aging. Dr. Smith is funded by the NCI Core Grant P 30 006973, 1-R01 CA177562-01A1, 1-R01 NR014050 01, and the Harry J. Duffey Family Endowment for Palliative Care. Dr. Morrison was the recipient of a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (5K24AG022345) during the course of this work. This work was supported by the NIA, Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai [5P30AG028741], and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

1. Soni A. Top 10 Most Costly Conditions Among Men and Women, 2008: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Adult Population, Age 18 and Older. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

2. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128. PubMed

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2015.

4. Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2060-2065. PubMed

5. Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine/National Academies Press; 2013. PubMed

7. Anderson GF. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010.

8. Tibi-Levy Y, Le Vaillant M, de Pouvourville G. Determinants of resource utilization in four palliative care units. Palliat Med. 2006;20(2):95-106. PubMed

9. Simoens S, Kutten B, Keirse E, et al. The costs of treating terminal patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(3):436-448. PubMed

10. Groeneveld I, Murtagh F, Kaloki Y, Bausewein C, Higginson I. Determinants of healthcare costs in the last year of life. Annual Assembly of American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine & Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association; March 14, 2013; New Orleans, LA.

11. Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures at the end of life for colorectal cancer decedents. J Womens Health. 2007;16(2):214-227. PubMed

12. Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures and service utilization at the end of life for lung cancer decedents. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(3):199-209. PubMed

13. Walker H, Anderson M, Farahati F, et al. Resource use and costs of end-of-life/palliative care: Ontario adult cancer patients dying during 2002 and 2003. J Palliat Care. 2011;27(2):79-88. PubMed

14. Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):493-501. PubMed

15. Hanratty B, Burstrom B, Walander A, Whitehead M. Inequality in the face of death? Public expenditure on health care for different socioeconomic groups in the last year of life. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(2):90-94. PubMed

16. Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(4):235-242. PubMed

17. Guerriere DN, Zagorski B, Fassbender K, Masucci L, Librach L, Coyte PC. Cost variations in ambulatory and home-based palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24(5):523-532. PubMed

18. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Palliative Care for Hospitalized Cancer Patients [project information]. Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2006. Project 5R01CA116227-04. https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?projectnumber=5R01CA116227-04. Published 2006. Accessed August 1, 2015.

19. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2745-2752. PubMed

20. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):44-53. PubMed

21. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Morrison RS, Normand C. Using length of stay to control for unobserved heterogeneity when estimating treatment effect on hospital costs with observational data: issues of reliability, robustness and usefulness. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(5):2020-2043. PubMed

22. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. PubMed

23. Chang VT, Hwang SS, Kasimis B, Thaler HT. Shorter symptom assessment instruments: the Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (CMSAS). Cancer Invest. 2004;22(4):526-536. PubMed

24. Katz S, Ford A, Moskowitz R, Jackson B, Jaffe M. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychological function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919. PubMed

25. McLaughlin MA, Orosz GM, Magaziner J, et al. Preoperative status and risk of complications in patients with hip fracture. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):219-225. PubMed

26. Taheri PA, Butz D, Griffes LC, Morlock DR, Greenfield LJ. Physician impact on the total cost of care. Ann Surg. 2000;231(3):432-435. PubMed

27. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Economics Resource Center. Determining costs. Washington, DC: US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Health Economics Resource Center; 2016. http://www.herc.research.va.gov/include/page.asp?id=determining-costs. Published 2016. Accessed September 7, 2016.

28. US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. FY 2011 Wage Index [Table 2]. Baltimore, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2011. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Wage-Index-Files-Items/CMS1234173.html. Published 2011. Accessed September 2, 2014.

29. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. All Urban Consumers (Current Series) [Consumer Price Index database]. US Dept of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2015. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2016.

30. Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24(3):465-488. PubMed

31. Jones AM, Rice N, Bago d’Uva T, Balia S. Applied Health Economics. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Routledge; 2013.

32. Stata [computer program]. Version 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2011.

33. Garrido MM, Kelley AS, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing

propensity scores. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1701-1720. PubMed

34. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna,

Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016.

35. Cassel JB, Kerr K, Pantilat S, Smith TJ. Palliative care consultation and hospital

length of stay. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(6):761-767. PubMed

36. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality. Efforts to Improve Patient Safety Result in 1.3 Million Fewer Patient

Harms: Interim Update on 2013 Annual Hospital-Acquired Condition Rate and

Estimates of Cost Savings and Deaths Averted From 2010 to 2013. Rockville,

MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality; 2015. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/pfp/

interimhacrate2013.html. Published 2015. Updated November 2015. Accessed

November 18, 2016.

37. Cassidy A. Health Policy Brief: Medicare’s Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction

Program. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_

id=142. Published August 6, 2015. Accessed April 24, 2017.

38. Davis MA, Nallamothu BK, Banerjee M, Bynum JP. Identification of four unique

spending patterns among older adults in the last year of life challenges standard

assumptions. Health Aff. 2016;35(7):1316-1323. PubMed

39. Aldridge MD, Kelley AS. The myth regarding the high cost of end-of-life care.

Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2411-2415. PubMed

40. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard

oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline

update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112. PubMed

41. Spetz J, Dudley N, Trupin L, Rogers M, Meier DE, Dumanovsky T. Few hospital

palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff.

2016;35(9):1690-1697. PubMed

42. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities

in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. PubMed

43. HCUP [Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project] Elixhauser Comorbidity Software

[computer program]. Version 3.7. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality; 2016. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/

comorbidity.jsp. Published 2016. Accessed November 9, 2016.

44. Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for

administrative data. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1109-1118. PubMed

1. Soni A. Top 10 Most Costly Conditions Among Men and Women, 2008: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Adult Population, Age 18 and Older. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

2. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128. PubMed

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2015.

4. Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2060-2065. PubMed

5. Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine/National Academies Press; 2013. PubMed

7. Anderson GF. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010.

8. Tibi-Levy Y, Le Vaillant M, de Pouvourville G. Determinants of resource utilization in four palliative care units. Palliat Med. 2006;20(2):95-106. PubMed

9. Simoens S, Kutten B, Keirse E, et al. The costs of treating terminal patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(3):436-448. PubMed

10. Groeneveld I, Murtagh F, Kaloki Y, Bausewein C, Higginson I. Determinants of healthcare costs in the last year of life. Annual Assembly of American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine & Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association; March 14, 2013; New Orleans, LA.

11. Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures at the end of life for colorectal cancer decedents. J Womens Health. 2007;16(2):214-227. PubMed

12. Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures and service utilization at the end of life for lung cancer decedents. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(3):199-209. PubMed

13. Walker H, Anderson M, Farahati F, et al. Resource use and costs of end-of-life/palliative care: Ontario adult cancer patients dying during 2002 and 2003. J Palliat Care. 2011;27(2):79-88. PubMed

14. Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):493-501. PubMed

15. Hanratty B, Burstrom B, Walander A, Whitehead M. Inequality in the face of death? Public expenditure on health care for different socioeconomic groups in the last year of life. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(2):90-94. PubMed

16. Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(4):235-242. PubMed

17. Guerriere DN, Zagorski B, Fassbender K, Masucci L, Librach L, Coyte PC. Cost variations in ambulatory and home-based palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24(5):523-532. PubMed

18. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Palliative Care for Hospitalized Cancer Patients [project information]. Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2006. Project 5R01CA116227-04. https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?projectnumber=5R01CA116227-04. Published 2006. Accessed August 1, 2015.

19. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2745-2752. PubMed

20. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):44-53. PubMed

21. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Morrison RS, Normand C. Using length of stay to control for unobserved heterogeneity when estimating treatment effect on hospital costs with observational data: issues of reliability, robustness and usefulness. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(5):2020-2043. PubMed