User login

Heart Failure and Hip Fracture Repair

As the population ages, hip fractures and heart failure increase in prevalence.1, 2 Heart failure prevalence is also increasing in hospitalized patients.3 Indeed, hospitalizations involving heart failure as an active issue tripled in the last 30 years.4 Heart failure has been associated with an increased risk for hip fracture,5, 6 and previous studies report a 6%20% prevalence of preoperative heart failure in hip fracture patients.710 While exacerbation of heart failure increases the mortality risk in patients admitted for hip fractures,8 the incidence of new heart failure, as well as the preoperative factors that predict postoperative heart failure in this patient population remain unclear.

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) perioperative guidelines identify orthopedic surgeries, including hip fracture repair, as intermediate risk procedures.11 Compared to other intermediate risk operations, however, postoperative outcomes following hip fracture repair differ significantly.1216 Overall mortality in hip fracture patients has been reported at 29% at one year,8 with the excess mortality from hip fracture alone at nearly 20%.10, 13 However, the exact factors that contribute to this excess mortality, particularly with regard to heart failure, remain unclear.

To examine the preoperative prevalence, subsequent incidence, and predictors of heart failure in patients undergoing hip fracture repair operations, this study used an established, population‐based database to compare the postoperative consequences in hip fracture repair patients with and without preexisting heart failure. We hypothesized that preoperative heart failure worsens postoperative outcomes in hip fracture patients.

METHODS

Case Ascertainment

Following approval by the Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted Medical Center, we used the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) to identify the patients for this study. The REP is a population‐based medical records linkage system that records all diagnoses, surgical procedures, laboratory data, and death information from hospital, emergency room, outpatient, and nursing home care in the community.17

All Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents who sustained a hip fracture and underwent surgical repair from 1988 through 2002 were evaluated. Patients with more than one hip fracture during the study period (96 occurrences) were censored from the data analysis at the time of the subsequent hip fracture and then included as new cases. The complete enumeration of hip fracture episodes managed in the three Olmsted County hospital facilities (Mayo Clinic's Saint Mary's and Rochester Methodist Hospitals, and the Olmsted Medical Center Hospital) occurred in three phases: First, all hospitalizations with the surgical procedure (International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9]) codes 79.15 (reduction, fracture, femur, closed with internal fixation), 79.25 (reduction, fracture, femur, open, without internal fixation), 79.35 (reduction, fracture, femur, open with internal fixation), 79.95 (operation, unspecified bone injury, femur), 80.05 (arthrotomy for removal of hip prosthesis), 80.15 (arthrotomy, other, hip), 80.95 (excision, hip joint), 81.21 (arthrodesis, hip), 81.40 (repair hip, not elsewhere classified), 81.51 (total hip replacement), 81.52 (partial hip replacement), and 81.53 (revision hip replacement) were identified. Second, through review of the original inpatient and outpatient medical records, we confirmed that a fracture was associated with the index hospitalization. Finally, radiology reports of each index hospitalization verified the presence and exact anatomical location of each fracture. Of those with fractures on admission x‐rays, only patients with a proximal femur (femoral neck or intertrochanteric) fracture as the primary indication for the surgery were included in the study. Surgical report or radiographic evidence of hip fracture was available for all patients. Secondary fractures due to a specific pathological lesion (eg, malignancy) or high‐energy trauma (by convention, motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights) were excluded. Only patients who had provided an authorization to review their medical records for research were ultimately included in the study cohort.18 Medical records were search manually, if indicated.

Criteria for Heart Failure and Death

Preoperative heart failure was based on clinical documentation of heart failure in a patient's medical record prior to the time of the hip fracture repair. Postoperative heart failure, including acute exacerbations, was defined according to Framingham criteria.19 Framingham criteria included clinical evidence of increased central venous pressure, pulmonary edema, an S3 gallop, radiographic pulmonary edema, and response to diuresis. Heart failure was not graded on clinical severity (ie, New York Heart Association classification). We did not distinguish between systolic and diastolic heart failure. Mortality was defined as death from any cause within the first year following hip fracture repair. Deaths were identified either through REP resources or the National Death Index.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are presented as mean standard deviation and categorical variables as number (percent). Two‐sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to test for significant differences in continuous variables. Chi‐square or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables. Rates of postoperative outcomes were calculated using the KaplanMeier method for the overall group and for those with and without preoperative heart failure. A landmark survival curve was used to evaluate postoperative mortality among patients who experienced heart failure in the first seven postoperative days versus those who did not. Patients who died or underwent another hip operation within the first seven postoperative days were excluded from this analysis. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the predictors of postoperative heart failure and mortality. Patients who died or experienced a second hip surgery within one year of their first were censored at that time. Any subsequent hip fracture repair was treated as a new case. To account for the inclusion of multiple hip fracture repairs for a given patient, the Cox proportional hazards model included a robust variance estimator. This provided an accurate calculation of the standard error in the presence of within‐subject correlation.20 Statistical tests were two‐sided, and P values were considered significant if less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From among 1327 potential hip fracture repairs, we excluded 115 cases involving multiple injuries or operations (19), pathological fractures (20), in‐hospital fractures (3), or an operation >72 hours after the initial fracture (5). Three patients under 65 years of age were also excluded, as were cases with missing information (9) or cases managed nonoperatively (56). The final analysis included 1212 surgical cases in 1116 subjects. No subjects were lost to surveillance for 1 year following their hip fracture repair.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study population. The overall prevalence of preoperative heart failure was 27.0% (327 of 1212). Those with preoperative heart failure were older, heavier, more likely male and white, and less likely to live independently preoperatively. They were also more likely to suffer from preexisting cardiovascular comorbidities.

| All (N = 1,212) | HF (N = 327) | No HF (N = 885) | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 84.2 (7.44) | 85.5 (6.54) | 83.7 (7.70) | 0.00101 |

| Male gender | 237 (19.6) | 76 (23.2) | 161 (18.2) | 0.04912 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) (SD) | 23.3 (4.97) | 24.1 (5.68) | 23.0 (4.65) | 0.01231 |

| White | 1,204 (99.3) | 322 (98.5) | 882 (99.7) | 0.03713 |

| Preoperative living situation | ||||

| Nursing facility | 468 (38.6) | 144 (44) | 324 (36.6) | 0.01842 |

| Home | 744 (61.4) | 183 (56) | 561 (63.4) | 0.05192 |

| Preoperative ambulatory status | ||||

| Dependent | 149 (12.3) | 50 (15.3) | 99 (11.2) | |

| Independent | 1,061 (87.7) | 276 (84.7) | 785 (88.8) | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 705 (58.2) | 226 (69.1) | 479 (54.1) | <0.00012 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 143 (11.8) | 63 (19.3) | 80 (9) | <0.00012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 331 (27.3) | 129 (39.4) | 202 (22.8) | <0.00012 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 195 (16.1) | 80 (24.5) | 115 (13) | <0.00012 |

| Coronary artery disease | 464 (38.3) | 237 (72.5) | 227 (25.6) | <0.00012 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 254 (21) | 133 (40.7) | 121 (13.7) | <0.00012 |

| Complete heart block | 18 (1.5) | 9 (2.8) | 9 (1) | 0.03373 |

| Pacer at time of admission | 32 (2.6) | 16 (4.9) | 16 (1.8) | 0.00292 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 196 (16.2) | 78 (23.9) | 118 (13.3) | <0.00012 |

| Liver disease | 15 (1.2) | 7 (2.1) | 8 (0.9) | 0.13753 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 131 (10.8) | 61 (18.7) | 70 (7.9) | <0.00012 |

| Mean length of hospitalization (days) (SD) | 10.0 (7.57) | 11.1 (8.82) | 9.6 (7.01) | 0.00101 |

| Discharge disposition | 0.00192 | |||

| Home | 150 (12.4) | 26 (8.0) | 124 (14.0) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 1,004 (82.9) | 278 (85.0) | 726 (82.1) | |

| Dead | 57 (4.7) | 23 (7.0) | 34 (3.9) | |

Table 1 also summarizes the main outcome characteristics of the study population. Those with preoperative heart failure had longer mean lengths of stay (LOS), were more often discharged to a skilled facility, and demonstrated higher inpatient mortality rates.

Table 2 summarizes the outcomes associated with preoperative heart failure. The overall rate of postoperative heart failure was 6.7% within 7 postoperative days and 21.3% within 1 postoperative year. Postoperative heart failure was significantly more common among those with preoperative heart failure (hazard ratio [HR], 3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3 to 3.9; P < 0.001). Among those without preoperative heart failure, rates of postoperative incident heart failure were 4.8% at 7 days and 15.0% at 1 year. Compared to patients without preoperative heart failure, those with preoperative heart failure demonstrated higher one year mortality rates and higher rates of postoperative heart failure at 7 days and 1 year.

| Preoperative Heart Failure (Subjects) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | All (N = 1212) | No (N = 885) | Yes (N = 327) | Risk ratio* (95% CI) | P Value |

| |||||

| Heart failure exacerbation within seven postoperative days | 6.7% (5.4, 8.3) | 4.8% (3.5, 6.5) | 12.1% (8.7, 16.2) | 2.72 (1.72, 4.31) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative heart failure exacerbation | 21.3% (18.8, 23.7) | 15.0% (12.5, 17.4) | 39.3% (33.3, 44.9) | 3.00 (2.32, 3.87) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative mortality | 24.5% (22.0, 26.9) | 19.8% (17.1, 22.4) | 37.2% (31.6, 42.3) | 2.11 (1.67, 2.67) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative mortality or heart failure exacerbation | 36.5% (33.7, 39.2) | 29.7% (26.6, 32.6) | 55.0% (49.3, 60.2) | 2.28 (1.88, 2.76) | <0.0001 |

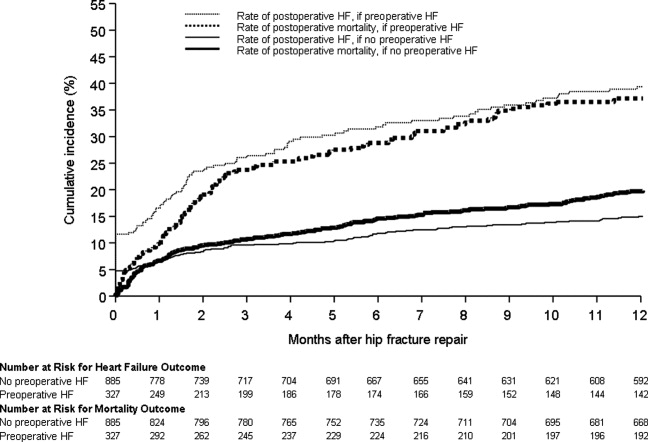

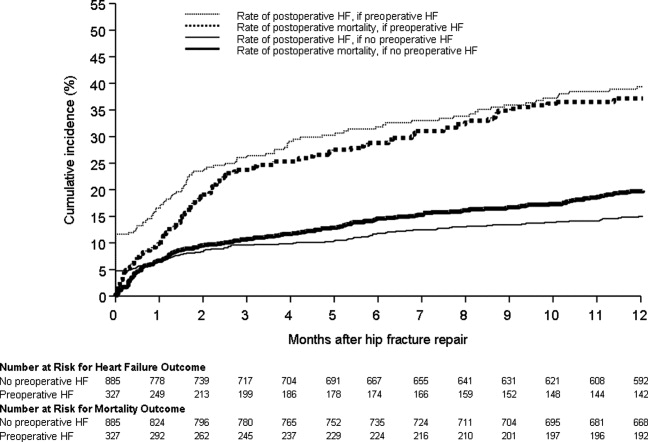

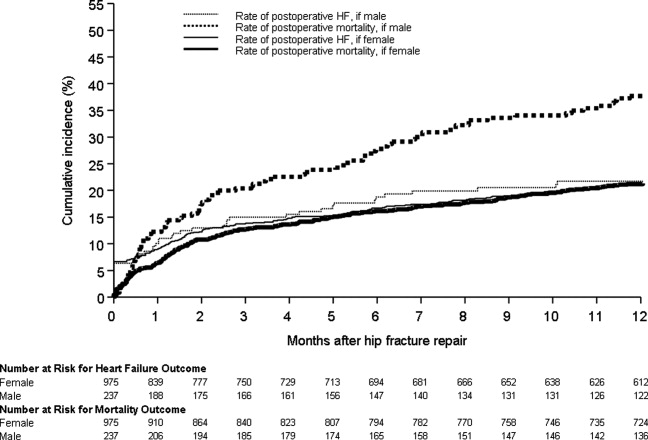

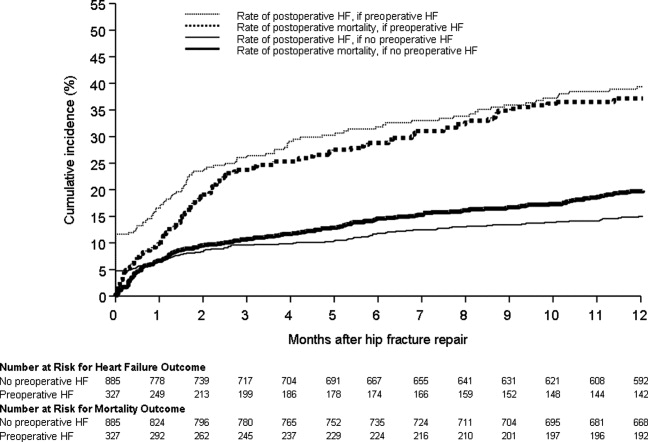

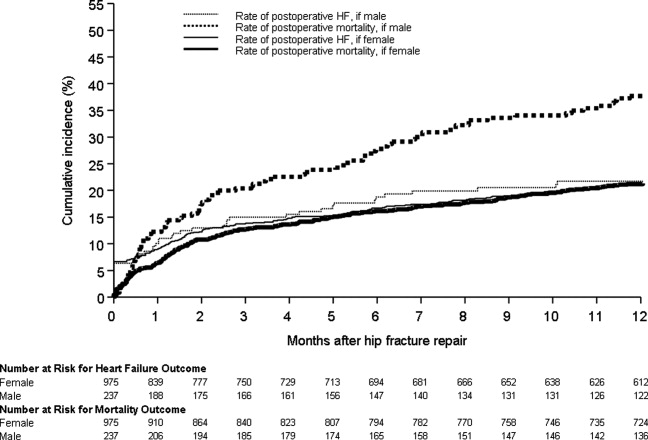

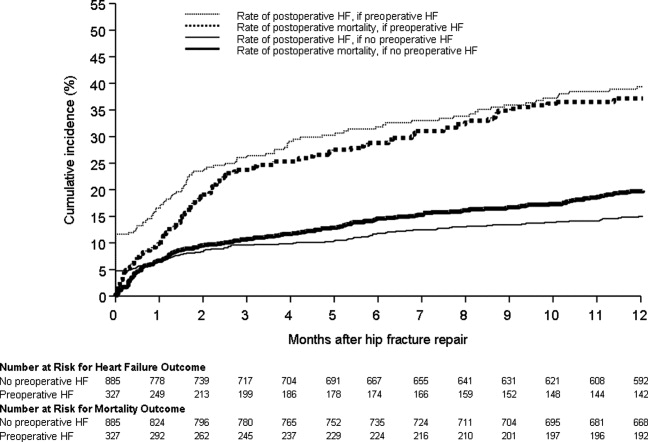

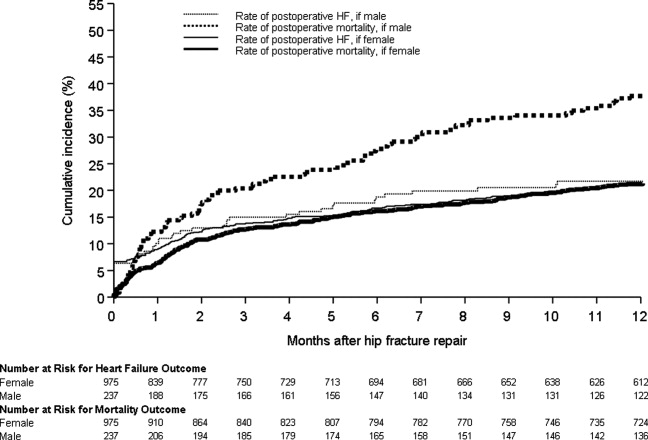

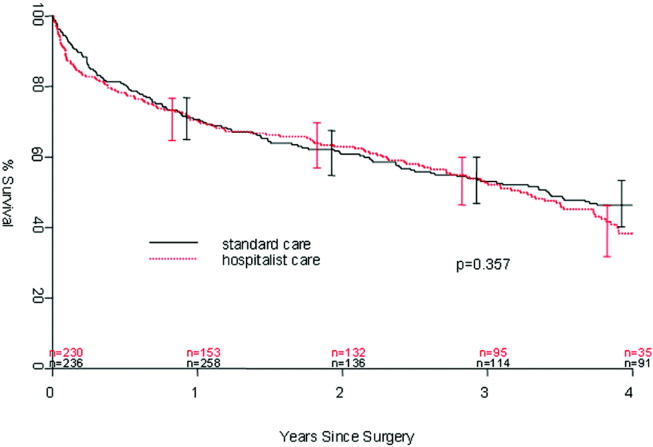

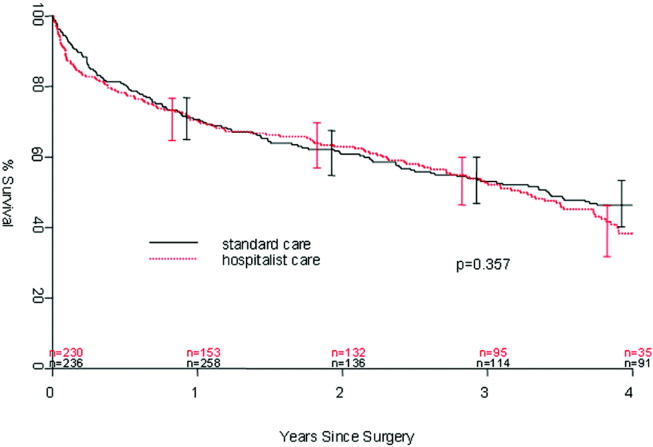

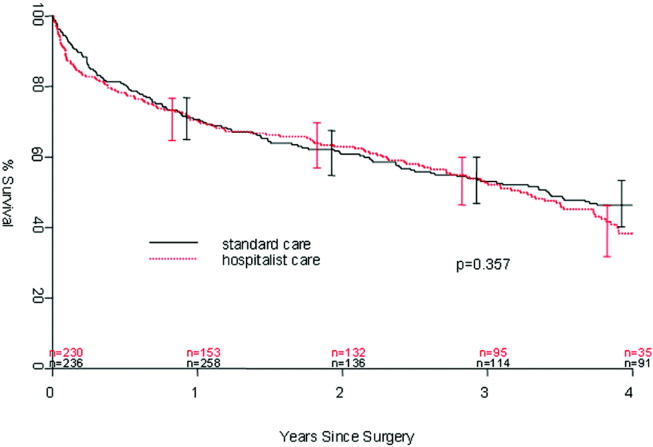

Figure 1 displays the outcomes to 1 year of surveillance. Rates of postoperative heart failure and postoperative mortality were consistently higher among those with, versus without, preoperative heart failure. Figure 2 displays similar data stratified by gender. Postoperative heart failure rates did not differ significantly between genders (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8 to 1.4), but postoperative mortality rates were significantly higher among males than females (HR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.5 to 2.5; P < 0.001).

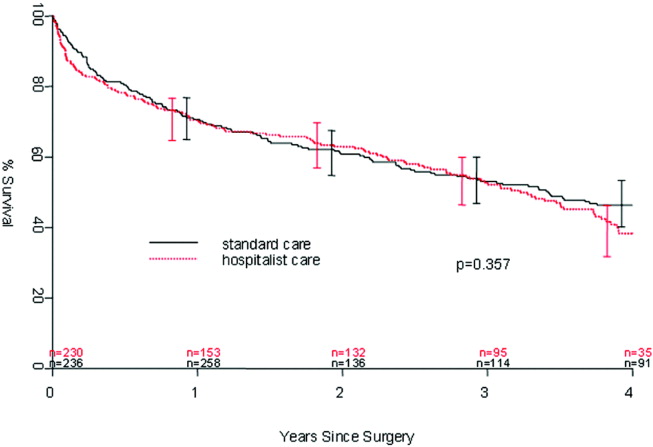

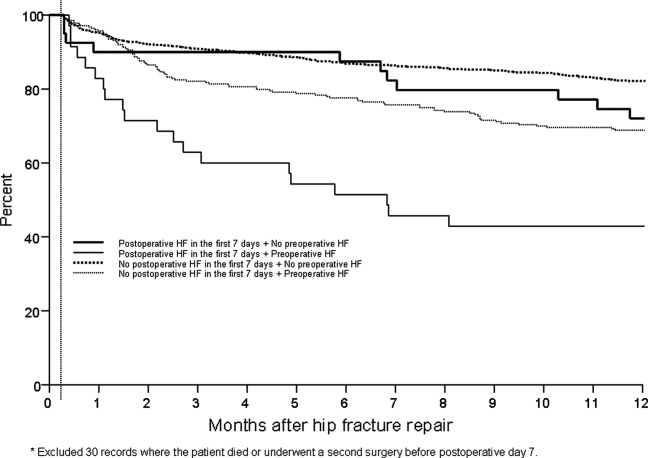

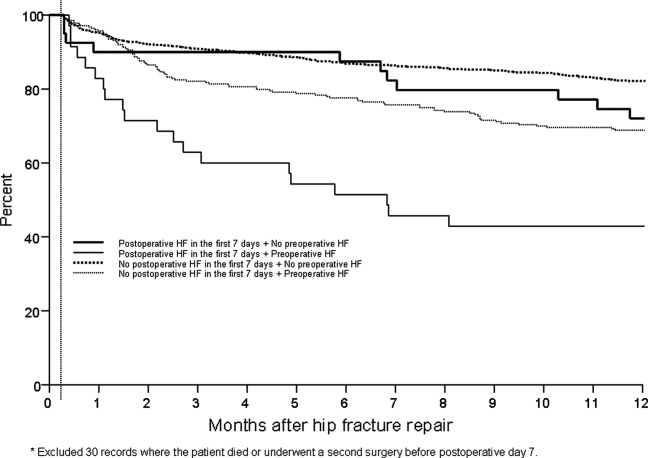

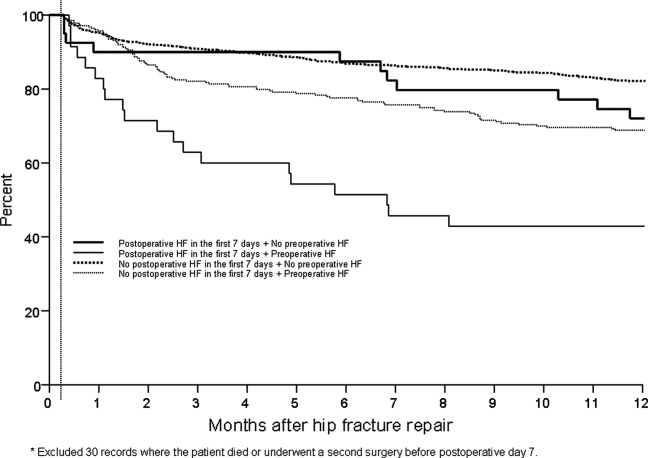

Figure 3 displays survival rates to 1 year based on the occurrence of incident or recurrent heart failure within the first 7 postoperative days. Survival rates were lowest among patients with recurrent heart failure in the first 7 postoperative days and highest among those with no preoperative or postoperative heart failure. Subjects with incident heart failure in the first postoperative week, and those with preoperative heart failure who did not suffer a recurrence, demonstrated intermediate survival rates (P < 0.001 for trend across all four groups).

DISCUSSION

This population‐based study found that heart failure represents a highly prevalent condition in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture repairs. It demonstrates that those with preoperative heart failure typically suffer from more cardiovascular comorbidities and carry a higher risk of postoperative heart failure and postoperative mortality.

While many studies have focused on the epidemiology of hip fractures,21 population‐based data on cardiac complications following hip fracture repair are significantly less common. The ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guidelines classify orthopedic procedures, including hip fracture repair, as intermediate risk.11 Consequently, some may assume that all orthopedic patients will have a mortality rate less than 5%. Indeed, the 30‐day postoperative mortality rate published from our institution's Total Joint Registry was 0.6% following elective total hip arthroplasty.22 However, the present study demonstrates that current ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guidelines may not apply to the population of frail patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Particularly among those who experience new heart failure within the first seven days following surgery, outcomes are substantially worse than the ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines may suggest.11

Preoperative heart failure has been associated with adverse risk for postoperative mortality after hip fracture.9, 10, 12 However, these studies did not report heart failure as a complication of hip fracture repair. A prospective cohort study of 2448 hip fracture patients at an academic hospital in Great Britain found a 5% rate of inpatient heart failure as a postoperative complication.23 The hazard ratio for one‐year mortality was 11.3 with postoperative heart failure.23 However, the British study did not distinguish heart failure from other cardiovascular diseases as a preoperative comorbidity or stratify the risk for postoperative mortality by preoperative heart failure status.23 Our findings add to previous literature by measuring heart failure as a specific complication of hip fracture repair and examining the association of preoperative heart failure with postoperative heart failure and mortality.

Length of stay after hip fracture repair varies in the literature, but previous work has not clearly associated heart failure with length of hospitalization in the setting of hip fracture repair.24, 25 Our study found a significantly higher mean length of stay among those with preoperative heart failure. This adds to previous work by delineating an association between heart failure and increased length of stay after hip fracture repair.

We found a higher rate of postoperative mortality among men compared to women. Rates of postoperative heart failure, however, were more similar (Figure 2). Previous studies have found a consistently higher mortality rate among men versus women after hip fracture.9, 23, 2529 Possible explanations for these findings include the overall increased burden of cardiovascular disease among men, lower treatment rates of osteoporosis in men,30 and increased susceptibility to other postoperative complications, such as infection.25

The findings of this study carry important clinical implications for the perioperative care of hip fracture patients with, or at risk for, heart failure. They suggest that current risk stratification guidelines classifying orthopedic operations as intermediate risk procedures do not reflect the high risk for morbidity that hip fracture patients face.11 The association of heart failure with adverse outcomes implies the need for heightened surveillance in the perioperative period, particularly with regard to volume status and medication reconciliation. Hip fracture patients and their families must be counseled about the ramifications of perioperative heart failure, including higher rates of postoperative heart failure, longer hospitalizations, and ultimate mortality.

This research carries several limitations and remains subject to biases inherent in retrospective cohort studies. The reported effects of heart failure on outcomes after hip fracture repair may be due to confounding from age, functional status, and other comorbidities. We attempted to minimize sampling bias through complete enumeration of hip fracture surgeries among Olmsted County residents. Completeness of follow‐up (100% at one year) was possible given the availability of documentation of all inpatient and outpatient medical care in the community.17 We used objectively defined outcomes to minimize measurement bias. Applicability to a more diverse population may be limited because >95% of the research population was from a single, predominantly white community. However, prior studies have documented that hip fracture incidence rates31 and socioeconomic factors17 in Olmsted County are similar to those for other white residents of the United States. Heart failure rates were determined clinically according to the Framingham criteria. However, the Framingham criteria may inappropriately diagnose individuals with heart failure32 and falsely elevate the prevalence of heart failure as a preoperative comorbidity or postoperative complication.

The statistical analysis included patients counted multiple times if they underwent subsequent hip fracture repair during the study period. Including these patients may inaccurately inflate event rates or contribute to incorrect estimates of standard error. However, we felt it was appropriate to include recurrent hip fracture repair cases in the analysis because they represent a clinically distinct patient from both a medical and functional perspective. We used a robust variance estimator in the Cox proportional hazards models to provide an accurate calculation of the standard error given the possibility for correlation within subjects.20 Finally, the proportion of these patients was low (94 of 1116 unique patients; 8.4%).

Future work must involve further risk stratification and therapeutic interventions in perioperative hip fracture patients. A more robust analysis of heart failure, with differentiation between systolic and diastolic dysfunction, may facilitate risk stratification. Assessment of compliance with standard preoperative heart failure medications and the impact of heightened clinical vigilance may enlighten means to improve postoperative outcomes. Studies on risk stratification and therapeutic interventions may then inform policy regarding length of stay and reimbursement in hip fracture patients.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our population‐based findings reveal that heart failure represents a prevalent and serious comorbidity in patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Clinicians caring for perioperative hip fracture patients must pay particular attention to risk for, and implications of, new or recurrent heart failure.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Donna K. Lawson, LPN, Kathy Wolfert, and Cherie Dolliver for their assistance in data collection and management.

- .Epidemiology of hip fractures: Implications of the exponential increase with age.Bone.1996;18(3 suppl):121S–125S.

- ,,, et al.Trends in length of stay and short‐term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006.JAMA.2010;303(21):2141–2147.

- ,,,,.The expanding national burden of heart failure in the United States: The influence of heart failure in women.Am Heart J.2004;147(1):74–78.

- ,,,.Heart failure‐related hospitalization in the U.S., 1979 to 2004.J Am Coll Cardiol.2008;52(6):428–434.

- ,,,,.Heart failure is a risk factor for orthopedic fracture: A population‐based analysis of 16,294 patients.Circulation.2008;118(19):1946–1952.

- ,,, et al.Cardiovascular diseases and risk of hip fracture.JAMA.2009;302(15):1666–1673.

- ,,,.Effectiveness of hospitalist involvement in hip fracture management questioned.South Med J.2007;100(9):912–913.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures.J Hosp Med.2007;2(4):219–225.

- ,,,.Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival.Age Ageing.2010;39(2):203–209.

- ,,.Increased mortality in patients with a hip fracture—Effect of pre‐morbid conditions and post‐fracture complications.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(12):1583–1593.

- ,,, et al.ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;50(17):1707–1732.

- ,,,,.Excess mortality following hip fracture: The role of underlying health status.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(11):1463–1472.

- .Time trends of mortality after first hip fractures.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(6):721–732.

- ,,, et al.Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: Risk factors and risk‐adjusted hospital outcomes.JAMA.2001;285(21):2736–2742.

- ,,,.Factors associated with mortality after hip fracture.Osteoporos Int.2000;11(3):228–232.

- ,,,,,.Hip fractures among the elderly: Factors associated with in‐hospital mortality.Am J Epidemiol.1991;134(10):1128–1137.

- .History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.Mayo Clin Proc.1996;71(3):266–274.

- .The threat to medical‐records research.N Engl J Med.1997;337(20):1466–1470.

- ,,,.The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham Study.N Engl J Med.1971;285(26):1441–1446.

- ,.The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model.J Am Stat Assoc.1989;84(408):1074–1078.

- .Hip fracture epidemiological trends, outcomes, and risk factors, 1970–2009.Int J Gen Med.2010;3:1–17.

- ,,,,,.Frequency of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and death following primary hip or knee arthroplasty.Anesthesiology.2002;96(5):1140–1146.

- ,,,.Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: Prospective observational cohort study.BMJ.2005;331(7529):1374–1376.

- ,,, et al.The aftermath of hip fracture: Discharge placement, functional status change, and mortality.Am J Epidemiol.2009;170(10):1290–1299.

- ,,,,,.Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: The role of infection.J Bone Miner Res.2003;18(12):2231–2237.

- ,,,,.Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: An observational study.Lancet.1999;353(9156):878–882.

- ,,.Adjusted mortality after hip fracture: From the Cardiovascular Health Study.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006;54(12):1885–1891.

- ,,, et al.Meta‐analysis: Excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men.Ann Intern Med.2010;152(6):380–390.

- ,,,.Predictors of hip fractures in elderly men.J Bone Miner Res.1995;10(12):1900–1907.

- ,,, et al.Population‐based fracture risk assessment and osteoporosis treatment disparities by race and gender.J Gen Intern Med.2009;24(8):956–962.

- ,,.Long‐term trends in hip fracture prevalence: The influence of hip fracture incidence and survival.Osteoporos Int.1998;8(1):68–74.

- ,,,,,.diagnostic accuracy of clinical criteria for identifying systolic and diastolic heart failure: Cross‐sectional study.J Eval Clin Pract.2009;15(1):55–61.

As the population ages, hip fractures and heart failure increase in prevalence.1, 2 Heart failure prevalence is also increasing in hospitalized patients.3 Indeed, hospitalizations involving heart failure as an active issue tripled in the last 30 years.4 Heart failure has been associated with an increased risk for hip fracture,5, 6 and previous studies report a 6%20% prevalence of preoperative heart failure in hip fracture patients.710 While exacerbation of heart failure increases the mortality risk in patients admitted for hip fractures,8 the incidence of new heart failure, as well as the preoperative factors that predict postoperative heart failure in this patient population remain unclear.

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) perioperative guidelines identify orthopedic surgeries, including hip fracture repair, as intermediate risk procedures.11 Compared to other intermediate risk operations, however, postoperative outcomes following hip fracture repair differ significantly.1216 Overall mortality in hip fracture patients has been reported at 29% at one year,8 with the excess mortality from hip fracture alone at nearly 20%.10, 13 However, the exact factors that contribute to this excess mortality, particularly with regard to heart failure, remain unclear.

To examine the preoperative prevalence, subsequent incidence, and predictors of heart failure in patients undergoing hip fracture repair operations, this study used an established, population‐based database to compare the postoperative consequences in hip fracture repair patients with and without preexisting heart failure. We hypothesized that preoperative heart failure worsens postoperative outcomes in hip fracture patients.

METHODS

Case Ascertainment

Following approval by the Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted Medical Center, we used the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) to identify the patients for this study. The REP is a population‐based medical records linkage system that records all diagnoses, surgical procedures, laboratory data, and death information from hospital, emergency room, outpatient, and nursing home care in the community.17

All Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents who sustained a hip fracture and underwent surgical repair from 1988 through 2002 were evaluated. Patients with more than one hip fracture during the study period (96 occurrences) were censored from the data analysis at the time of the subsequent hip fracture and then included as new cases. The complete enumeration of hip fracture episodes managed in the three Olmsted County hospital facilities (Mayo Clinic's Saint Mary's and Rochester Methodist Hospitals, and the Olmsted Medical Center Hospital) occurred in three phases: First, all hospitalizations with the surgical procedure (International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9]) codes 79.15 (reduction, fracture, femur, closed with internal fixation), 79.25 (reduction, fracture, femur, open, without internal fixation), 79.35 (reduction, fracture, femur, open with internal fixation), 79.95 (operation, unspecified bone injury, femur), 80.05 (arthrotomy for removal of hip prosthesis), 80.15 (arthrotomy, other, hip), 80.95 (excision, hip joint), 81.21 (arthrodesis, hip), 81.40 (repair hip, not elsewhere classified), 81.51 (total hip replacement), 81.52 (partial hip replacement), and 81.53 (revision hip replacement) were identified. Second, through review of the original inpatient and outpatient medical records, we confirmed that a fracture was associated with the index hospitalization. Finally, radiology reports of each index hospitalization verified the presence and exact anatomical location of each fracture. Of those with fractures on admission x‐rays, only patients with a proximal femur (femoral neck or intertrochanteric) fracture as the primary indication for the surgery were included in the study. Surgical report or radiographic evidence of hip fracture was available for all patients. Secondary fractures due to a specific pathological lesion (eg, malignancy) or high‐energy trauma (by convention, motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights) were excluded. Only patients who had provided an authorization to review their medical records for research were ultimately included in the study cohort.18 Medical records were search manually, if indicated.

Criteria for Heart Failure and Death

Preoperative heart failure was based on clinical documentation of heart failure in a patient's medical record prior to the time of the hip fracture repair. Postoperative heart failure, including acute exacerbations, was defined according to Framingham criteria.19 Framingham criteria included clinical evidence of increased central venous pressure, pulmonary edema, an S3 gallop, radiographic pulmonary edema, and response to diuresis. Heart failure was not graded on clinical severity (ie, New York Heart Association classification). We did not distinguish between systolic and diastolic heart failure. Mortality was defined as death from any cause within the first year following hip fracture repair. Deaths were identified either through REP resources or the National Death Index.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are presented as mean standard deviation and categorical variables as number (percent). Two‐sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to test for significant differences in continuous variables. Chi‐square or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables. Rates of postoperative outcomes were calculated using the KaplanMeier method for the overall group and for those with and without preoperative heart failure. A landmark survival curve was used to evaluate postoperative mortality among patients who experienced heart failure in the first seven postoperative days versus those who did not. Patients who died or underwent another hip operation within the first seven postoperative days were excluded from this analysis. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the predictors of postoperative heart failure and mortality. Patients who died or experienced a second hip surgery within one year of their first were censored at that time. Any subsequent hip fracture repair was treated as a new case. To account for the inclusion of multiple hip fracture repairs for a given patient, the Cox proportional hazards model included a robust variance estimator. This provided an accurate calculation of the standard error in the presence of within‐subject correlation.20 Statistical tests were two‐sided, and P values were considered significant if less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From among 1327 potential hip fracture repairs, we excluded 115 cases involving multiple injuries or operations (19), pathological fractures (20), in‐hospital fractures (3), or an operation >72 hours after the initial fracture (5). Three patients under 65 years of age were also excluded, as were cases with missing information (9) or cases managed nonoperatively (56). The final analysis included 1212 surgical cases in 1116 subjects. No subjects were lost to surveillance for 1 year following their hip fracture repair.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study population. The overall prevalence of preoperative heart failure was 27.0% (327 of 1212). Those with preoperative heart failure were older, heavier, more likely male and white, and less likely to live independently preoperatively. They were also more likely to suffer from preexisting cardiovascular comorbidities.

| All (N = 1,212) | HF (N = 327) | No HF (N = 885) | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 84.2 (7.44) | 85.5 (6.54) | 83.7 (7.70) | 0.00101 |

| Male gender | 237 (19.6) | 76 (23.2) | 161 (18.2) | 0.04912 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) (SD) | 23.3 (4.97) | 24.1 (5.68) | 23.0 (4.65) | 0.01231 |

| White | 1,204 (99.3) | 322 (98.5) | 882 (99.7) | 0.03713 |

| Preoperative living situation | ||||

| Nursing facility | 468 (38.6) | 144 (44) | 324 (36.6) | 0.01842 |

| Home | 744 (61.4) | 183 (56) | 561 (63.4) | 0.05192 |

| Preoperative ambulatory status | ||||

| Dependent | 149 (12.3) | 50 (15.3) | 99 (11.2) | |

| Independent | 1,061 (87.7) | 276 (84.7) | 785 (88.8) | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 705 (58.2) | 226 (69.1) | 479 (54.1) | <0.00012 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 143 (11.8) | 63 (19.3) | 80 (9) | <0.00012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 331 (27.3) | 129 (39.4) | 202 (22.8) | <0.00012 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 195 (16.1) | 80 (24.5) | 115 (13) | <0.00012 |

| Coronary artery disease | 464 (38.3) | 237 (72.5) | 227 (25.6) | <0.00012 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 254 (21) | 133 (40.7) | 121 (13.7) | <0.00012 |

| Complete heart block | 18 (1.5) | 9 (2.8) | 9 (1) | 0.03373 |

| Pacer at time of admission | 32 (2.6) | 16 (4.9) | 16 (1.8) | 0.00292 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 196 (16.2) | 78 (23.9) | 118 (13.3) | <0.00012 |

| Liver disease | 15 (1.2) | 7 (2.1) | 8 (0.9) | 0.13753 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 131 (10.8) | 61 (18.7) | 70 (7.9) | <0.00012 |

| Mean length of hospitalization (days) (SD) | 10.0 (7.57) | 11.1 (8.82) | 9.6 (7.01) | 0.00101 |

| Discharge disposition | 0.00192 | |||

| Home | 150 (12.4) | 26 (8.0) | 124 (14.0) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 1,004 (82.9) | 278 (85.0) | 726 (82.1) | |

| Dead | 57 (4.7) | 23 (7.0) | 34 (3.9) | |

Table 1 also summarizes the main outcome characteristics of the study population. Those with preoperative heart failure had longer mean lengths of stay (LOS), were more often discharged to a skilled facility, and demonstrated higher inpatient mortality rates.

Table 2 summarizes the outcomes associated with preoperative heart failure. The overall rate of postoperative heart failure was 6.7% within 7 postoperative days and 21.3% within 1 postoperative year. Postoperative heart failure was significantly more common among those with preoperative heart failure (hazard ratio [HR], 3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3 to 3.9; P < 0.001). Among those without preoperative heart failure, rates of postoperative incident heart failure were 4.8% at 7 days and 15.0% at 1 year. Compared to patients without preoperative heart failure, those with preoperative heart failure demonstrated higher one year mortality rates and higher rates of postoperative heart failure at 7 days and 1 year.

| Preoperative Heart Failure (Subjects) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | All (N = 1212) | No (N = 885) | Yes (N = 327) | Risk ratio* (95% CI) | P Value |

| |||||

| Heart failure exacerbation within seven postoperative days | 6.7% (5.4, 8.3) | 4.8% (3.5, 6.5) | 12.1% (8.7, 16.2) | 2.72 (1.72, 4.31) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative heart failure exacerbation | 21.3% (18.8, 23.7) | 15.0% (12.5, 17.4) | 39.3% (33.3, 44.9) | 3.00 (2.32, 3.87) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative mortality | 24.5% (22.0, 26.9) | 19.8% (17.1, 22.4) | 37.2% (31.6, 42.3) | 2.11 (1.67, 2.67) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative mortality or heart failure exacerbation | 36.5% (33.7, 39.2) | 29.7% (26.6, 32.6) | 55.0% (49.3, 60.2) | 2.28 (1.88, 2.76) | <0.0001 |

Figure 1 displays the outcomes to 1 year of surveillance. Rates of postoperative heart failure and postoperative mortality were consistently higher among those with, versus without, preoperative heart failure. Figure 2 displays similar data stratified by gender. Postoperative heart failure rates did not differ significantly between genders (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8 to 1.4), but postoperative mortality rates were significantly higher among males than females (HR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.5 to 2.5; P < 0.001).

Figure 3 displays survival rates to 1 year based on the occurrence of incident or recurrent heart failure within the first 7 postoperative days. Survival rates were lowest among patients with recurrent heart failure in the first 7 postoperative days and highest among those with no preoperative or postoperative heart failure. Subjects with incident heart failure in the first postoperative week, and those with preoperative heart failure who did not suffer a recurrence, demonstrated intermediate survival rates (P < 0.001 for trend across all four groups).

DISCUSSION

This population‐based study found that heart failure represents a highly prevalent condition in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture repairs. It demonstrates that those with preoperative heart failure typically suffer from more cardiovascular comorbidities and carry a higher risk of postoperative heart failure and postoperative mortality.

While many studies have focused on the epidemiology of hip fractures,21 population‐based data on cardiac complications following hip fracture repair are significantly less common. The ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guidelines classify orthopedic procedures, including hip fracture repair, as intermediate risk.11 Consequently, some may assume that all orthopedic patients will have a mortality rate less than 5%. Indeed, the 30‐day postoperative mortality rate published from our institution's Total Joint Registry was 0.6% following elective total hip arthroplasty.22 However, the present study demonstrates that current ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guidelines may not apply to the population of frail patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Particularly among those who experience new heart failure within the first seven days following surgery, outcomes are substantially worse than the ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines may suggest.11

Preoperative heart failure has been associated with adverse risk for postoperative mortality after hip fracture.9, 10, 12 However, these studies did not report heart failure as a complication of hip fracture repair. A prospective cohort study of 2448 hip fracture patients at an academic hospital in Great Britain found a 5% rate of inpatient heart failure as a postoperative complication.23 The hazard ratio for one‐year mortality was 11.3 with postoperative heart failure.23 However, the British study did not distinguish heart failure from other cardiovascular diseases as a preoperative comorbidity or stratify the risk for postoperative mortality by preoperative heart failure status.23 Our findings add to previous literature by measuring heart failure as a specific complication of hip fracture repair and examining the association of preoperative heart failure with postoperative heart failure and mortality.

Length of stay after hip fracture repair varies in the literature, but previous work has not clearly associated heart failure with length of hospitalization in the setting of hip fracture repair.24, 25 Our study found a significantly higher mean length of stay among those with preoperative heart failure. This adds to previous work by delineating an association between heart failure and increased length of stay after hip fracture repair.

We found a higher rate of postoperative mortality among men compared to women. Rates of postoperative heart failure, however, were more similar (Figure 2). Previous studies have found a consistently higher mortality rate among men versus women after hip fracture.9, 23, 2529 Possible explanations for these findings include the overall increased burden of cardiovascular disease among men, lower treatment rates of osteoporosis in men,30 and increased susceptibility to other postoperative complications, such as infection.25

The findings of this study carry important clinical implications for the perioperative care of hip fracture patients with, or at risk for, heart failure. They suggest that current risk stratification guidelines classifying orthopedic operations as intermediate risk procedures do not reflect the high risk for morbidity that hip fracture patients face.11 The association of heart failure with adverse outcomes implies the need for heightened surveillance in the perioperative period, particularly with regard to volume status and medication reconciliation. Hip fracture patients and their families must be counseled about the ramifications of perioperative heart failure, including higher rates of postoperative heart failure, longer hospitalizations, and ultimate mortality.

This research carries several limitations and remains subject to biases inherent in retrospective cohort studies. The reported effects of heart failure on outcomes after hip fracture repair may be due to confounding from age, functional status, and other comorbidities. We attempted to minimize sampling bias through complete enumeration of hip fracture surgeries among Olmsted County residents. Completeness of follow‐up (100% at one year) was possible given the availability of documentation of all inpatient and outpatient medical care in the community.17 We used objectively defined outcomes to minimize measurement bias. Applicability to a more diverse population may be limited because >95% of the research population was from a single, predominantly white community. However, prior studies have documented that hip fracture incidence rates31 and socioeconomic factors17 in Olmsted County are similar to those for other white residents of the United States. Heart failure rates were determined clinically according to the Framingham criteria. However, the Framingham criteria may inappropriately diagnose individuals with heart failure32 and falsely elevate the prevalence of heart failure as a preoperative comorbidity or postoperative complication.

The statistical analysis included patients counted multiple times if they underwent subsequent hip fracture repair during the study period. Including these patients may inaccurately inflate event rates or contribute to incorrect estimates of standard error. However, we felt it was appropriate to include recurrent hip fracture repair cases in the analysis because they represent a clinically distinct patient from both a medical and functional perspective. We used a robust variance estimator in the Cox proportional hazards models to provide an accurate calculation of the standard error given the possibility for correlation within subjects.20 Finally, the proportion of these patients was low (94 of 1116 unique patients; 8.4%).

Future work must involve further risk stratification and therapeutic interventions in perioperative hip fracture patients. A more robust analysis of heart failure, with differentiation between systolic and diastolic dysfunction, may facilitate risk stratification. Assessment of compliance with standard preoperative heart failure medications and the impact of heightened clinical vigilance may enlighten means to improve postoperative outcomes. Studies on risk stratification and therapeutic interventions may then inform policy regarding length of stay and reimbursement in hip fracture patients.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our population‐based findings reveal that heart failure represents a prevalent and serious comorbidity in patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Clinicians caring for perioperative hip fracture patients must pay particular attention to risk for, and implications of, new or recurrent heart failure.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Donna K. Lawson, LPN, Kathy Wolfert, and Cherie Dolliver for their assistance in data collection and management.

As the population ages, hip fractures and heart failure increase in prevalence.1, 2 Heart failure prevalence is also increasing in hospitalized patients.3 Indeed, hospitalizations involving heart failure as an active issue tripled in the last 30 years.4 Heart failure has been associated with an increased risk for hip fracture,5, 6 and previous studies report a 6%20% prevalence of preoperative heart failure in hip fracture patients.710 While exacerbation of heart failure increases the mortality risk in patients admitted for hip fractures,8 the incidence of new heart failure, as well as the preoperative factors that predict postoperative heart failure in this patient population remain unclear.

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) perioperative guidelines identify orthopedic surgeries, including hip fracture repair, as intermediate risk procedures.11 Compared to other intermediate risk operations, however, postoperative outcomes following hip fracture repair differ significantly.1216 Overall mortality in hip fracture patients has been reported at 29% at one year,8 with the excess mortality from hip fracture alone at nearly 20%.10, 13 However, the exact factors that contribute to this excess mortality, particularly with regard to heart failure, remain unclear.

To examine the preoperative prevalence, subsequent incidence, and predictors of heart failure in patients undergoing hip fracture repair operations, this study used an established, population‐based database to compare the postoperative consequences in hip fracture repair patients with and without preexisting heart failure. We hypothesized that preoperative heart failure worsens postoperative outcomes in hip fracture patients.

METHODS

Case Ascertainment

Following approval by the Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted Medical Center, we used the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) to identify the patients for this study. The REP is a population‐based medical records linkage system that records all diagnoses, surgical procedures, laboratory data, and death information from hospital, emergency room, outpatient, and nursing home care in the community.17

All Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents who sustained a hip fracture and underwent surgical repair from 1988 through 2002 were evaluated. Patients with more than one hip fracture during the study period (96 occurrences) were censored from the data analysis at the time of the subsequent hip fracture and then included as new cases. The complete enumeration of hip fracture episodes managed in the three Olmsted County hospital facilities (Mayo Clinic's Saint Mary's and Rochester Methodist Hospitals, and the Olmsted Medical Center Hospital) occurred in three phases: First, all hospitalizations with the surgical procedure (International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9]) codes 79.15 (reduction, fracture, femur, closed with internal fixation), 79.25 (reduction, fracture, femur, open, without internal fixation), 79.35 (reduction, fracture, femur, open with internal fixation), 79.95 (operation, unspecified bone injury, femur), 80.05 (arthrotomy for removal of hip prosthesis), 80.15 (arthrotomy, other, hip), 80.95 (excision, hip joint), 81.21 (arthrodesis, hip), 81.40 (repair hip, not elsewhere classified), 81.51 (total hip replacement), 81.52 (partial hip replacement), and 81.53 (revision hip replacement) were identified. Second, through review of the original inpatient and outpatient medical records, we confirmed that a fracture was associated with the index hospitalization. Finally, radiology reports of each index hospitalization verified the presence and exact anatomical location of each fracture. Of those with fractures on admission x‐rays, only patients with a proximal femur (femoral neck or intertrochanteric) fracture as the primary indication for the surgery were included in the study. Surgical report or radiographic evidence of hip fracture was available for all patients. Secondary fractures due to a specific pathological lesion (eg, malignancy) or high‐energy trauma (by convention, motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights) were excluded. Only patients who had provided an authorization to review their medical records for research were ultimately included in the study cohort.18 Medical records were search manually, if indicated.

Criteria for Heart Failure and Death

Preoperative heart failure was based on clinical documentation of heart failure in a patient's medical record prior to the time of the hip fracture repair. Postoperative heart failure, including acute exacerbations, was defined according to Framingham criteria.19 Framingham criteria included clinical evidence of increased central venous pressure, pulmonary edema, an S3 gallop, radiographic pulmonary edema, and response to diuresis. Heart failure was not graded on clinical severity (ie, New York Heart Association classification). We did not distinguish between systolic and diastolic heart failure. Mortality was defined as death from any cause within the first year following hip fracture repair. Deaths were identified either through REP resources or the National Death Index.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are presented as mean standard deviation and categorical variables as number (percent). Two‐sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to test for significant differences in continuous variables. Chi‐square or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables. Rates of postoperative outcomes were calculated using the KaplanMeier method for the overall group and for those with and without preoperative heart failure. A landmark survival curve was used to evaluate postoperative mortality among patients who experienced heart failure in the first seven postoperative days versus those who did not. Patients who died or underwent another hip operation within the first seven postoperative days were excluded from this analysis. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the predictors of postoperative heart failure and mortality. Patients who died or experienced a second hip surgery within one year of their first were censored at that time. Any subsequent hip fracture repair was treated as a new case. To account for the inclusion of multiple hip fracture repairs for a given patient, the Cox proportional hazards model included a robust variance estimator. This provided an accurate calculation of the standard error in the presence of within‐subject correlation.20 Statistical tests were two‐sided, and P values were considered significant if less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From among 1327 potential hip fracture repairs, we excluded 115 cases involving multiple injuries or operations (19), pathological fractures (20), in‐hospital fractures (3), or an operation >72 hours after the initial fracture (5). Three patients under 65 years of age were also excluded, as were cases with missing information (9) or cases managed nonoperatively (56). The final analysis included 1212 surgical cases in 1116 subjects. No subjects were lost to surveillance for 1 year following their hip fracture repair.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study population. The overall prevalence of preoperative heart failure was 27.0% (327 of 1212). Those with preoperative heart failure were older, heavier, more likely male and white, and less likely to live independently preoperatively. They were also more likely to suffer from preexisting cardiovascular comorbidities.

| All (N = 1,212) | HF (N = 327) | No HF (N = 885) | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 84.2 (7.44) | 85.5 (6.54) | 83.7 (7.70) | 0.00101 |

| Male gender | 237 (19.6) | 76 (23.2) | 161 (18.2) | 0.04912 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) (SD) | 23.3 (4.97) | 24.1 (5.68) | 23.0 (4.65) | 0.01231 |

| White | 1,204 (99.3) | 322 (98.5) | 882 (99.7) | 0.03713 |

| Preoperative living situation | ||||

| Nursing facility | 468 (38.6) | 144 (44) | 324 (36.6) | 0.01842 |

| Home | 744 (61.4) | 183 (56) | 561 (63.4) | 0.05192 |

| Preoperative ambulatory status | ||||

| Dependent | 149 (12.3) | 50 (15.3) | 99 (11.2) | |

| Independent | 1,061 (87.7) | 276 (84.7) | 785 (88.8) | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 705 (58.2) | 226 (69.1) | 479 (54.1) | <0.00012 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 143 (11.8) | 63 (19.3) | 80 (9) | <0.00012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 331 (27.3) | 129 (39.4) | 202 (22.8) | <0.00012 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 195 (16.1) | 80 (24.5) | 115 (13) | <0.00012 |

| Coronary artery disease | 464 (38.3) | 237 (72.5) | 227 (25.6) | <0.00012 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 254 (21) | 133 (40.7) | 121 (13.7) | <0.00012 |

| Complete heart block | 18 (1.5) | 9 (2.8) | 9 (1) | 0.03373 |

| Pacer at time of admission | 32 (2.6) | 16 (4.9) | 16 (1.8) | 0.00292 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 196 (16.2) | 78 (23.9) | 118 (13.3) | <0.00012 |

| Liver disease | 15 (1.2) | 7 (2.1) | 8 (0.9) | 0.13753 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 131 (10.8) | 61 (18.7) | 70 (7.9) | <0.00012 |

| Mean length of hospitalization (days) (SD) | 10.0 (7.57) | 11.1 (8.82) | 9.6 (7.01) | 0.00101 |

| Discharge disposition | 0.00192 | |||

| Home | 150 (12.4) | 26 (8.0) | 124 (14.0) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 1,004 (82.9) | 278 (85.0) | 726 (82.1) | |

| Dead | 57 (4.7) | 23 (7.0) | 34 (3.9) | |

Table 1 also summarizes the main outcome characteristics of the study population. Those with preoperative heart failure had longer mean lengths of stay (LOS), were more often discharged to a skilled facility, and demonstrated higher inpatient mortality rates.

Table 2 summarizes the outcomes associated with preoperative heart failure. The overall rate of postoperative heart failure was 6.7% within 7 postoperative days and 21.3% within 1 postoperative year. Postoperative heart failure was significantly more common among those with preoperative heart failure (hazard ratio [HR], 3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3 to 3.9; P < 0.001). Among those without preoperative heart failure, rates of postoperative incident heart failure were 4.8% at 7 days and 15.0% at 1 year. Compared to patients without preoperative heart failure, those with preoperative heart failure demonstrated higher one year mortality rates and higher rates of postoperative heart failure at 7 days and 1 year.

| Preoperative Heart Failure (Subjects) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | All (N = 1212) | No (N = 885) | Yes (N = 327) | Risk ratio* (95% CI) | P Value |

| |||||

| Heart failure exacerbation within seven postoperative days | 6.7% (5.4, 8.3) | 4.8% (3.5, 6.5) | 12.1% (8.7, 16.2) | 2.72 (1.72, 4.31) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative heart failure exacerbation | 21.3% (18.8, 23.7) | 15.0% (12.5, 17.4) | 39.3% (33.3, 44.9) | 3.00 (2.32, 3.87) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative mortality | 24.5% (22.0, 26.9) | 19.8% (17.1, 22.4) | 37.2% (31.6, 42.3) | 2.11 (1.67, 2.67) | <0.0001 |

| One‐year postoperative mortality or heart failure exacerbation | 36.5% (33.7, 39.2) | 29.7% (26.6, 32.6) | 55.0% (49.3, 60.2) | 2.28 (1.88, 2.76) | <0.0001 |

Figure 1 displays the outcomes to 1 year of surveillance. Rates of postoperative heart failure and postoperative mortality were consistently higher among those with, versus without, preoperative heart failure. Figure 2 displays similar data stratified by gender. Postoperative heart failure rates did not differ significantly between genders (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8 to 1.4), but postoperative mortality rates were significantly higher among males than females (HR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.5 to 2.5; P < 0.001).

Figure 3 displays survival rates to 1 year based on the occurrence of incident or recurrent heart failure within the first 7 postoperative days. Survival rates were lowest among patients with recurrent heart failure in the first 7 postoperative days and highest among those with no preoperative or postoperative heart failure. Subjects with incident heart failure in the first postoperative week, and those with preoperative heart failure who did not suffer a recurrence, demonstrated intermediate survival rates (P < 0.001 for trend across all four groups).

DISCUSSION

This population‐based study found that heart failure represents a highly prevalent condition in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture repairs. It demonstrates that those with preoperative heart failure typically suffer from more cardiovascular comorbidities and carry a higher risk of postoperative heart failure and postoperative mortality.

While many studies have focused on the epidemiology of hip fractures,21 population‐based data on cardiac complications following hip fracture repair are significantly less common. The ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guidelines classify orthopedic procedures, including hip fracture repair, as intermediate risk.11 Consequently, some may assume that all orthopedic patients will have a mortality rate less than 5%. Indeed, the 30‐day postoperative mortality rate published from our institution's Total Joint Registry was 0.6% following elective total hip arthroplasty.22 However, the present study demonstrates that current ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guidelines may not apply to the population of frail patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Particularly among those who experience new heart failure within the first seven days following surgery, outcomes are substantially worse than the ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines may suggest.11

Preoperative heart failure has been associated with adverse risk for postoperative mortality after hip fracture.9, 10, 12 However, these studies did not report heart failure as a complication of hip fracture repair. A prospective cohort study of 2448 hip fracture patients at an academic hospital in Great Britain found a 5% rate of inpatient heart failure as a postoperative complication.23 The hazard ratio for one‐year mortality was 11.3 with postoperative heart failure.23 However, the British study did not distinguish heart failure from other cardiovascular diseases as a preoperative comorbidity or stratify the risk for postoperative mortality by preoperative heart failure status.23 Our findings add to previous literature by measuring heart failure as a specific complication of hip fracture repair and examining the association of preoperative heart failure with postoperative heart failure and mortality.

Length of stay after hip fracture repair varies in the literature, but previous work has not clearly associated heart failure with length of hospitalization in the setting of hip fracture repair.24, 25 Our study found a significantly higher mean length of stay among those with preoperative heart failure. This adds to previous work by delineating an association between heart failure and increased length of stay after hip fracture repair.

We found a higher rate of postoperative mortality among men compared to women. Rates of postoperative heart failure, however, were more similar (Figure 2). Previous studies have found a consistently higher mortality rate among men versus women after hip fracture.9, 23, 2529 Possible explanations for these findings include the overall increased burden of cardiovascular disease among men, lower treatment rates of osteoporosis in men,30 and increased susceptibility to other postoperative complications, such as infection.25

The findings of this study carry important clinical implications for the perioperative care of hip fracture patients with, or at risk for, heart failure. They suggest that current risk stratification guidelines classifying orthopedic operations as intermediate risk procedures do not reflect the high risk for morbidity that hip fracture patients face.11 The association of heart failure with adverse outcomes implies the need for heightened surveillance in the perioperative period, particularly with regard to volume status and medication reconciliation. Hip fracture patients and their families must be counseled about the ramifications of perioperative heart failure, including higher rates of postoperative heart failure, longer hospitalizations, and ultimate mortality.

This research carries several limitations and remains subject to biases inherent in retrospective cohort studies. The reported effects of heart failure on outcomes after hip fracture repair may be due to confounding from age, functional status, and other comorbidities. We attempted to minimize sampling bias through complete enumeration of hip fracture surgeries among Olmsted County residents. Completeness of follow‐up (100% at one year) was possible given the availability of documentation of all inpatient and outpatient medical care in the community.17 We used objectively defined outcomes to minimize measurement bias. Applicability to a more diverse population may be limited because >95% of the research population was from a single, predominantly white community. However, prior studies have documented that hip fracture incidence rates31 and socioeconomic factors17 in Olmsted County are similar to those for other white residents of the United States. Heart failure rates were determined clinically according to the Framingham criteria. However, the Framingham criteria may inappropriately diagnose individuals with heart failure32 and falsely elevate the prevalence of heart failure as a preoperative comorbidity or postoperative complication.

The statistical analysis included patients counted multiple times if they underwent subsequent hip fracture repair during the study period. Including these patients may inaccurately inflate event rates or contribute to incorrect estimates of standard error. However, we felt it was appropriate to include recurrent hip fracture repair cases in the analysis because they represent a clinically distinct patient from both a medical and functional perspective. We used a robust variance estimator in the Cox proportional hazards models to provide an accurate calculation of the standard error given the possibility for correlation within subjects.20 Finally, the proportion of these patients was low (94 of 1116 unique patients; 8.4%).

Future work must involve further risk stratification and therapeutic interventions in perioperative hip fracture patients. A more robust analysis of heart failure, with differentiation between systolic and diastolic dysfunction, may facilitate risk stratification. Assessment of compliance with standard preoperative heart failure medications and the impact of heightened clinical vigilance may enlighten means to improve postoperative outcomes. Studies on risk stratification and therapeutic interventions may then inform policy regarding length of stay and reimbursement in hip fracture patients.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our population‐based findings reveal that heart failure represents a prevalent and serious comorbidity in patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Clinicians caring for perioperative hip fracture patients must pay particular attention to risk for, and implications of, new or recurrent heart failure.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Donna K. Lawson, LPN, Kathy Wolfert, and Cherie Dolliver for their assistance in data collection and management.

- .Epidemiology of hip fractures: Implications of the exponential increase with age.Bone.1996;18(3 suppl):121S–125S.

- ,,, et al.Trends in length of stay and short‐term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006.JAMA.2010;303(21):2141–2147.

- ,,,,.The expanding national burden of heart failure in the United States: The influence of heart failure in women.Am Heart J.2004;147(1):74–78.

- ,,,.Heart failure‐related hospitalization in the U.S., 1979 to 2004.J Am Coll Cardiol.2008;52(6):428–434.

- ,,,,.Heart failure is a risk factor for orthopedic fracture: A population‐based analysis of 16,294 patients.Circulation.2008;118(19):1946–1952.

- ,,, et al.Cardiovascular diseases and risk of hip fracture.JAMA.2009;302(15):1666–1673.

- ,,,.Effectiveness of hospitalist involvement in hip fracture management questioned.South Med J.2007;100(9):912–913.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures.J Hosp Med.2007;2(4):219–225.

- ,,,.Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival.Age Ageing.2010;39(2):203–209.

- ,,.Increased mortality in patients with a hip fracture—Effect of pre‐morbid conditions and post‐fracture complications.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(12):1583–1593.

- ,,, et al.ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;50(17):1707–1732.

- ,,,,.Excess mortality following hip fracture: The role of underlying health status.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(11):1463–1472.

- .Time trends of mortality after first hip fractures.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(6):721–732.

- ,,, et al.Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: Risk factors and risk‐adjusted hospital outcomes.JAMA.2001;285(21):2736–2742.

- ,,,.Factors associated with mortality after hip fracture.Osteoporos Int.2000;11(3):228–232.

- ,,,,,.Hip fractures among the elderly: Factors associated with in‐hospital mortality.Am J Epidemiol.1991;134(10):1128–1137.

- .History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.Mayo Clin Proc.1996;71(3):266–274.

- .The threat to medical‐records research.N Engl J Med.1997;337(20):1466–1470.

- ,,,.The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham Study.N Engl J Med.1971;285(26):1441–1446.

- ,.The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model.J Am Stat Assoc.1989;84(408):1074–1078.

- .Hip fracture epidemiological trends, outcomes, and risk factors, 1970–2009.Int J Gen Med.2010;3:1–17.

- ,,,,,.Frequency of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and death following primary hip or knee arthroplasty.Anesthesiology.2002;96(5):1140–1146.

- ,,,.Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: Prospective observational cohort study.BMJ.2005;331(7529):1374–1376.

- ,,, et al.The aftermath of hip fracture: Discharge placement, functional status change, and mortality.Am J Epidemiol.2009;170(10):1290–1299.

- ,,,,,.Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: The role of infection.J Bone Miner Res.2003;18(12):2231–2237.

- ,,,,.Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: An observational study.Lancet.1999;353(9156):878–882.

- ,,.Adjusted mortality after hip fracture: From the Cardiovascular Health Study.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006;54(12):1885–1891.

- ,,, et al.Meta‐analysis: Excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men.Ann Intern Med.2010;152(6):380–390.

- ,,,.Predictors of hip fractures in elderly men.J Bone Miner Res.1995;10(12):1900–1907.

- ,,, et al.Population‐based fracture risk assessment and osteoporosis treatment disparities by race and gender.J Gen Intern Med.2009;24(8):956–962.

- ,,.Long‐term trends in hip fracture prevalence: The influence of hip fracture incidence and survival.Osteoporos Int.1998;8(1):68–74.

- ,,,,,.diagnostic accuracy of clinical criteria for identifying systolic and diastolic heart failure: Cross‐sectional study.J Eval Clin Pract.2009;15(1):55–61.

- .Epidemiology of hip fractures: Implications of the exponential increase with age.Bone.1996;18(3 suppl):121S–125S.

- ,,, et al.Trends in length of stay and short‐term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006.JAMA.2010;303(21):2141–2147.

- ,,,,.The expanding national burden of heart failure in the United States: The influence of heart failure in women.Am Heart J.2004;147(1):74–78.

- ,,,.Heart failure‐related hospitalization in the U.S., 1979 to 2004.J Am Coll Cardiol.2008;52(6):428–434.

- ,,,,.Heart failure is a risk factor for orthopedic fracture: A population‐based analysis of 16,294 patients.Circulation.2008;118(19):1946–1952.

- ,,, et al.Cardiovascular diseases and risk of hip fracture.JAMA.2009;302(15):1666–1673.

- ,,,.Effectiveness of hospitalist involvement in hip fracture management questioned.South Med J.2007;100(9):912–913.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures.J Hosp Med.2007;2(4):219–225.

- ,,,.Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival.Age Ageing.2010;39(2):203–209.

- ,,.Increased mortality in patients with a hip fracture—Effect of pre‐morbid conditions and post‐fracture complications.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(12):1583–1593.

- ,,, et al.ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;50(17):1707–1732.

- ,,,,.Excess mortality following hip fracture: The role of underlying health status.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(11):1463–1472.

- .Time trends of mortality after first hip fractures.Osteoporos Int.2007;18(6):721–732.

- ,,, et al.Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: Risk factors and risk‐adjusted hospital outcomes.JAMA.2001;285(21):2736–2742.

- ,,,.Factors associated with mortality after hip fracture.Osteoporos Int.2000;11(3):228–232.

- ,,,,,.Hip fractures among the elderly: Factors associated with in‐hospital mortality.Am J Epidemiol.1991;134(10):1128–1137.

- .History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.Mayo Clin Proc.1996;71(3):266–274.

- .The threat to medical‐records research.N Engl J Med.1997;337(20):1466–1470.

- ,,,.The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham Study.N Engl J Med.1971;285(26):1441–1446.

- ,.The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model.J Am Stat Assoc.1989;84(408):1074–1078.

- .Hip fracture epidemiological trends, outcomes, and risk factors, 1970–2009.Int J Gen Med.2010;3:1–17.

- ,,,,,.Frequency of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and death following primary hip or knee arthroplasty.Anesthesiology.2002;96(5):1140–1146.

- ,,,.Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: Prospective observational cohort study.BMJ.2005;331(7529):1374–1376.

- ,,, et al.The aftermath of hip fracture: Discharge placement, functional status change, and mortality.Am J Epidemiol.2009;170(10):1290–1299.

- ,,,,,.Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: The role of infection.J Bone Miner Res.2003;18(12):2231–2237.

- ,,,,.Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: An observational study.Lancet.1999;353(9156):878–882.

- ,,.Adjusted mortality after hip fracture: From the Cardiovascular Health Study.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006;54(12):1885–1891.

- ,,, et al.Meta‐analysis: Excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men.Ann Intern Med.2010;152(6):380–390.

- ,,,.Predictors of hip fractures in elderly men.J Bone Miner Res.1995;10(12):1900–1907.

- ,,, et al.Population‐based fracture risk assessment and osteoporosis treatment disparities by race and gender.J Gen Intern Med.2009;24(8):956–962.

- ,,.Long‐term trends in hip fracture prevalence: The influence of hip fracture incidence and survival.Osteoporos Int.1998;8(1):68–74.

- ,,,,,.diagnostic accuracy of clinical criteria for identifying systolic and diastolic heart failure: Cross‐sectional study.J Eval Clin Pract.2009;15(1):55–61.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine

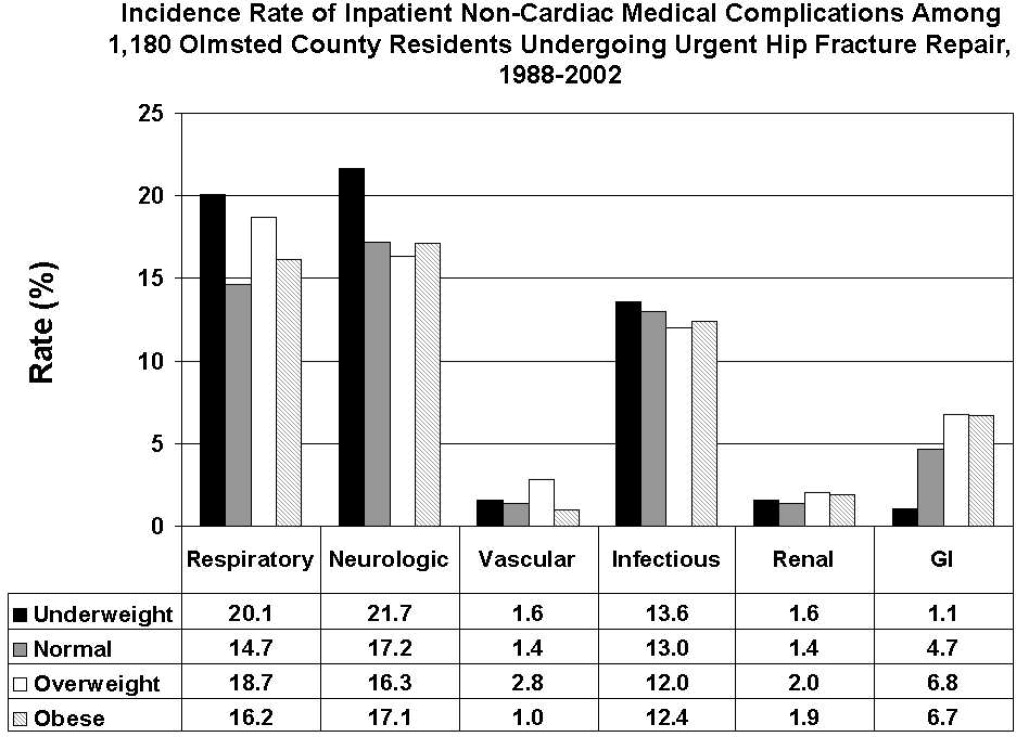

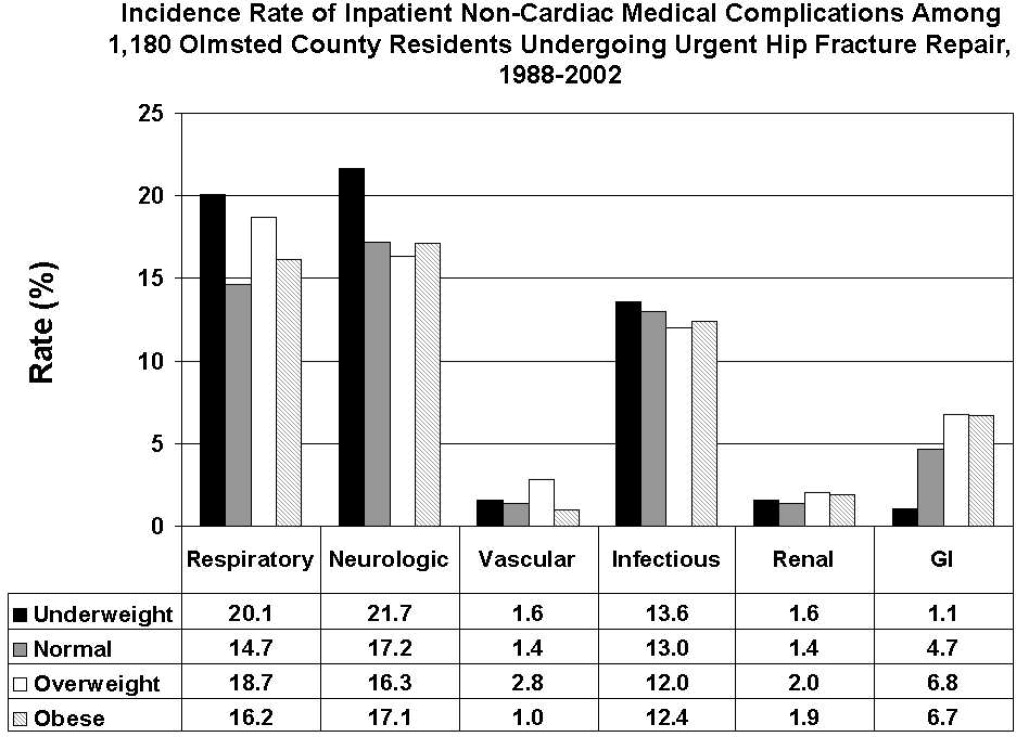

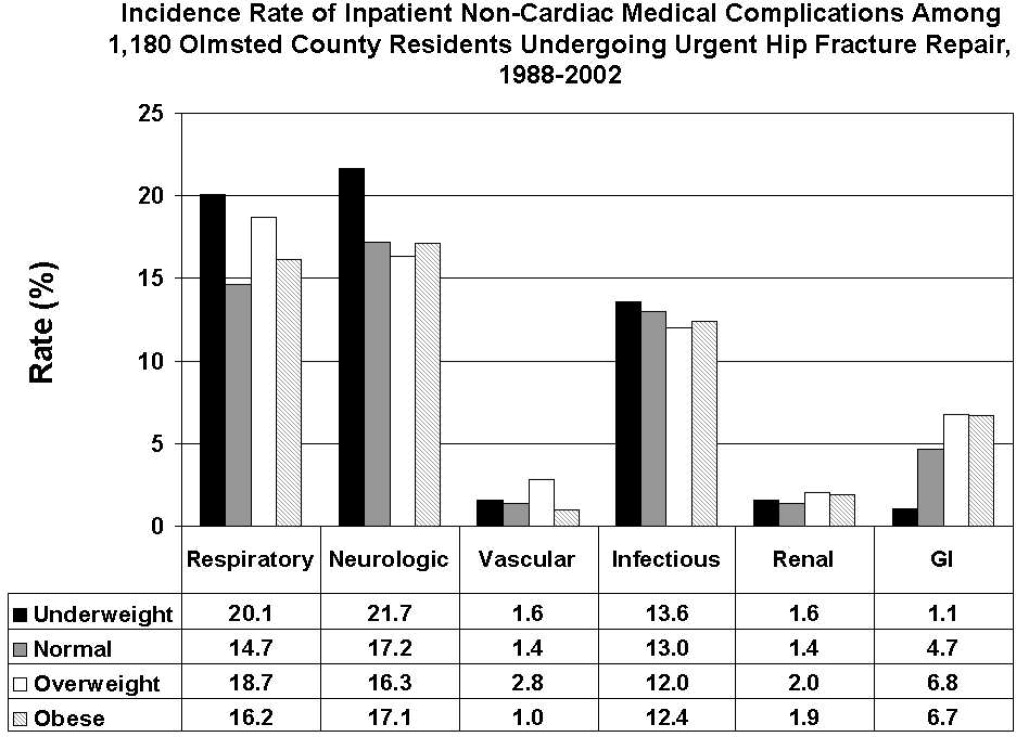

BMI and Postoperative Complications

Public health concerns such as the aging population1 and the increasing prevalence of obesity2 are also important issues to hospitals. However, little attention has been given to the interface of obesity and the elderly, largely due to the dearth of studies that include elderly patients. An aging population leads to an increase in geriatric syndromes, such as osteoporosis3 and its most devastating complication, hip fracture.4 These frail, hip‐fracture patients pose management challenges to practicing geriatricians and hospitalists.5,6 Furthermore, although fracture risk is inversely correlated to body mass index (BMI),7 this relationship has yet to be fully examined in the postoperative hip‐fracture population. In other surgical settings, there is disagreement as to whether underweight or obese patients are at higher risk of developing medical complications,8‐11 but for orthopedic patients, data have been limited to elective orthopedic populations.12‐14 We previously demonstrated that underweight hip‐fracture patients are at higher risk of postoperative cardiac complications at 1 year,15 consistent with studies of cardiac risk indices determining long‐term events. Because of different pathophysiologic mechanisms, the purpose of this study was to ascertain the influence of BMI on inpatient postoperative noncardiac medical complications and to assess predictors of such complications following urgent hip fracture repair.

Patients and Methods

All Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents undergoing urgent hip repair due to fracture were identified using the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a medical‐record linkage system funded by the Federal government since 1966 to support disease‐related epidemiology studies.16 All patient medical care is indexed, and both inpatient and outpatient visits are captured and available for review, allowing for complete case ascertainment. Medical care in Olmsted County is primarily provided by Mayo Clinic with its affiliated hospitals (St. Mary's and Rochester Methodist) and the Olmsted Medical Center, in addition to a few individual providers. Over 95% of all Olmsted County hip fracture surgeries are ultimately managed at St. Mary's Hospital.

Following approval by the Institutional Review Board we used this unique data resource to identify all residents with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD‐9) diagnosis code of 820 to 829 for hip fracture (n = 1310). Both sexes were included, and all patients included in the study provided research authorization for use of their medical records for research purposes.17 We excluded patients who were managed conservatively (n = 56), had a pathological fracture (n = 20), had multiple injuries (n = 19), were operated on >72 hours after fracture (n = 5), were aged <65 years (n = 2), or were admitted for reasons other than a fracture and experienced an in‐hospital fracture (n = 3). We subsequently excluded patients with missing information (n = 10). World Health Organization (WHO) criteria were used for classifying BMI: underweight (BMI < 18.5); normal (BMI = 18.5‐24.9); overweight (BMI = 25.0‐29.9); and obese (BMI 30.0).18

All data were abstracted using standardized collection forms by trained nurse abstractors blinded to the study hypothesis. Patients' admission height and weight were documented; if unavailable, the nearest data within 2 months prior to surgery were recorded. Patients' preadmission residence, functional status, baseline comorbidities, admission medications, discharge destination, as well as whether patients had an intensive care unit stay or any major surgeries in the past 90 days were abstracted. In addition, American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) class, type of anesthesia, and length of stay were also obtained. Inpatient complications that had been identified by the treating physicians and documented in the medical record or identified on imaging studies were assessed from the time of hip fracture repair to the time of discharge using standardized clinical criteria (Table 1). For criteria that were based on either objective findings or clinical documentation/suspicion, the patient was considered to meet the criteria of having a complication if they fulfilled either one. We did not include any cardiac outcomes, including congestive heart failure, angina, myocardial infarction, or arrhythmias that had been previously reported.15 Noncardiac complications were classified broadly: respiratory (respiratory failure, respiratory depression, or pulmonary hypoxemia); neurologic (any cerebral event including hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, or delirium); gastrointestinal (ileus or gastrointestinal bleeding); vascular (pulmonary embolus, or deep vein thrombosis); infectious (pneumonia, sepsis, urinary tract, wound, or cellulitis); renal/metabolic (acute renal failure, dehydration, or electrolyte abnormalities); or other (fractures or falls).

| Definition | Symptom |

|---|---|

| |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Ileus | Dilated loops of bowel on X‐ray; documented ileus with nausea, vomiting, no stool or inability to take oral intake |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | Sudden appearance of frank blood on nasogastric lavage or by rectum AND a decrease in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL or greater with no other suspected source of ongoing blood loss |

| Infectious | |

| Pneumonia | New infiltrate on chest x‐ray plus 2 of the following 3 findings: temperature >38C, elevated white cell count, sputum pathogen that requires antibiotic treatment |

| Bacteremia/sepsis | Localized infection with positive blood culture for the same pathogen AND chills, rigors, fever, elevated white cell count AND intravenous antibiotic treatment |

| Urinary tract infection | Pyuria symptoms |

| Positive gram stain symptoms | |

| Wound | |

| Cellulitis | As documented in physician's note of a superficial skin infection |