User login

Interventional psychiatry (Part 2)

While most psychiatric treatments have traditionally consisted of pharmacotherapy with oral medications, a better understanding of the pathophysiology underlying many mental illnesses has led to the recent increased use of treatments that require specialized administration and the creation of a subspecialty called interventional psychiatry. In Part 1 of this 2-part article (“Interventional psychiatry [Part 1],"

Neuromodulation treatments

Neuromodulation—the alteration of nerve activity through targeted delivery of a stimulus, such as electrical stimulation, to specific neurologic sites—is an increasingly common approach to treating a variety of psychiatric conditions. The use of some form of neuromodulation as a medical treatment has a long history (Box1-6). Modern electric neuromodulation began in the 1930s with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The 1960s saw the introduction of deep brain stimulation (DBS), spinal cord stimulation, and later, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Target-specific noninvasive brain stimulation became possible with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). These approaches are used for treating major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety disorders, and insomnia. Nearly all these neuromodulatory approaches require clinicians to undergo special training and patients to participate in an invasive procedure. These factors also increase cost. Nonetheless, the high rates of success of some of these approaches have led to relatively rapid and widespread acceptance.

Box

The depth and breadth of human anatomical knowledge has evolved over millennia. The time frame “thousands of years” may appear to be an overstatement, but evidence exists for successful therapeutic limb amputation as early as 31,000 years ago.1 This suggests that human knowledge of bone, muscle, and blood supply was developed much earlier than initially believed. Early Homo sapiens were altering the body—regulating or adjusting it— to serve a purpose; in this case, the purpose was survival.

In 46 AD, electrical modulation was introduced by Scribonius Largus, a physician in court of the emperor Tiberius, who used “torpedoes” (most likely electric eels) to treat headaches and pain from arthritis. Loosely, these early clinicians were modulating human function.

In the late 1800s, electrotherapeutics was a growing branch of medicine, with its own national organization—the American ElectroTherapeutic Association.2 In that era, electricity was novel, powerful, and seen as “the future.” Because such novel therapeutics were offered by both mainstream and dubious sources,3 “many of these products were marketed with the promise of curing everything from cancer to headaches.”4

Modern electric neuromodulation began in the 1930s with electroconvulsive therapy,5 followed by deep brain stimulation and spinal cord stimulation in the 1960s. Target-specific noninvasive brain stimulation became possible when Anthony Barker’s team developed the first device that permitted transcranial magnetic stimulation in 1985.6

Electroconvulsive therapy

In ECT, electric current is applied to the brain to induce a self-limiting seizure. It is the oldest and best-known interventional psychiatric treatment. ECT can also be considered one of the first treatments specifically developed to address pathophysiologic changes. In 1934, Ladislas J. Meduna, who had observed in neuropathologic studies that microglia were more numerous in patients with epilepsy compared with patients with schizophrenia, injected a patient who had been hospitalized with catatonia for 4 years with camphor, a proconvulsant.7 After 5 seizures, the patient began to recover. The therapeutic use of electricity was subsequently developed and optimized in animal models, and first used on human patients in Italy in 1939 and in the United States in 1940.8 The link between psychiatric illness and microglia, which was initially observed nearly a century ago, is making a comeback, as excessive microglial activation has been demonstrated in animal and human models of depression.9

Administering ECT requires specialized equipment, anesthesia, physician training, and nursing observation. ECT also has a negative public image.10 All of these factors conspire to reduce the availability of ECT. Despite this, approximately 100,000 patients in the United States and >1 million worldwide receive ECT each year.10 Patients generally require 6 to 12 ECT treatments11 to achieve sufficient response and may require additional maintenance treatments.12

Although ECT is used to treat psychiatric illnesses ranging from mood disorders to psychotic disorders and catatonia, it is mainly employed to treat people with severe treatment-resistant depression (TRD).13 ECT is associated with significant improvements in depressive symptoms and improvements in quality of life.14 It is superior to other treatments for TRD, such as ketamine,15 though a recent study did not show IV ketamine inferiority.16 ECT is also used to treat other neuropsychiatric disorders, such as Parkinson disease.17

Clinicians have explored alternate methods of inducing therapeutic seizures. Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) utilizes a modified magnetic stimulation device to deliver a higher energy in such a way to induce a generalized seizure under anesthesia.18 While patients receiving MST generally experience fewer adverse effects than with ECT, the procedure may be equal to19 or less effective than ECT.20

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

In neuroimaging research, certain aberrant brain circuits have been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression.21 Specifically, anatomical and functional imaging suggests connections in the prefrontal cortex are involved in the depression process. In TMS, a series of magnetic pulses are administered via the scalp to stimulate neurons in areas of the brain associated with MDD. Early case reports on using TMS to stimulate the prefrontal cortex found significant improvement of symptoms in patients with depression.22 These promising results spurred great interest in the procedure. Over time, the dose and duration of stimulation has increased, along with FDA-approved indications. TMS was first FDA-approved for TRD.23 Although the primary endpoint of the initial clinical trial did not meet criteria for FDA approval, TMS did result in improvement across multiple other measures of depression.23 After the FDA approved the first TMS device, numerous companies began to produce TMS technology. Most of these companies manufacture devices with the figure-of-eight coil, with 1 company producing the Hesed-coil helmet.24

Continue to: An unintended outcome...

An unintended outcome of the increased interest in TMS has been an increased understanding of brain regions involved in psychiatric illness. TMS was able to bring knowledge of mental health from synapses to circuits.25 Work in this area has further stratified the circuits involved in the manifestation of symptom clusters in depression.26 The exact taxonomy of these brain circuits has not been fully realized, but the default mode, salience, attention, cognitive control, and other circuits have been shown to be involved in specific symptom presentations.26,27 These circuits can be hyperactive, hypoactive, hyperconnected, or hypoconnected, with the aberrancies compared to normal controls resulting in symptoms of psychiatric illness.28

This enhanced understanding of brain function has led to further research and development of protocols and subsequent FDA approval of TMS for OCD, anxious depression, and smoking cessation.29 In addition, it has allowed for a proliferation of off-label uses for TMS, including (but not limited to) tinnitus, pain, migraines, and various substance use disorders.30 TMS treatment for these conditions involves stimulation of specific anatomical brain regions that are thought to play a role in the pathology of the target disorder. For example, subthreshold stimulation of the motor cortex has shown some utility in managing symptoms of pain disorders and movement disorders,31,32 the ventromedial prefrontal cortex has been implicated in disorders in the OCD spectrum,33 stimulation of the frontal poles may help treat substance use disorders,34 and the auditory cortex has been a target for treating tinnitus and auditory hallucinations.35

The location of stimulation for treating depression has evolved. The Talairach-Tournoux coordinate system has been used to determine the location of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in relation to the motor cortex. This was measured to be 5 cm from the motor hotspot and subsequently became “the 5.5 cm rule,” taking skull convexity into account. The treatment paradigm for the Hesed coil also uses a measurement from the motor hotspot. Another commonly used methodology for coil placement involves using the 10 to 20 EEG coordinate system to individualize scalp landmarks. In this method, the F3 location corresponds most accurately to the DLPFC target. More recently, using fMRI-guided navigation for coil placement has been shown to lead to a significant reduction in depressive symptoms.36

For depression, the initial recommended course of treatment is 6 weeks, but most improvement is seen in the first 2 to 3 weeks.14 Therefore, many clinicians administer an initial course of 3 weeks unless the response is inadequate, in which case a 6-week course is administered. Many patients require ongoing maintenance treatment, which can be weekly or monthly based on response.37

Research to determine the optimal TMS dose for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms is ongoing. Location, intensity of stimulation, and pulse are the components of stimulation. The pulse can be subdivided into frequency, pattern (single pulse, standard, burst), train (numbers of pulse groups), interval between trains, and total number of pulses per session. The Clinical TMS Society has published TMS protocols.38 The standard intensity of stimulation is 120% of the motor threshold (MT), which is defined as the amount of stimulation over the motor cortex required to produce movement in the extensor hallucis longus. Although treatment for depression traditionally utilizes rapid TMS (3,000 pulses delivered per session at a frequency of 10 Hz in 4-second trains), in controlled studies, accelerated protocols such as intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS; standard stimulation parameters: triplet 50 Hz bursts at 5 Hz, with an interval of 8 seconds for 600 pulses per session) have shown noninferiority.36,39

Recent research has explored fMRI-guided iTBS in an even more accelerated format. The Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy trial involved 1,800 pulses per session for 10 sessions a day for 5 days at 90% MT.36 This treatment paradigm was shown to be more effective than standard protocols and was FDA-approved in 2022. Although this specific iTBS protocol exhibited encouraging results, the need for fMRI for adequate delivery might limit its use.

Continue to: Transcranial direct current stimulation

Transcranial direct current stimulation

Therapeutic noninvasive brain stimulation technology is plausible due to the relative lack of adverse effects and ease of administration. In transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), a low-intensity, constant electric current is delivered to stimulate the brain via electrodes attached to the scalp. tDCS modulates spontaneous neuronal network activity40,41 and induces polarization of resting membrane potential at the neuronal level,42 though the exact mechanism is yet to be proven. N-methyl-

tDCS has been suggested as a treatment for various psychiatric and medical conditions. However, the small sample sizes and experimental design of published studies have limited tDCS from being clinically recommended.30 No recommendation of Level A (definite efficacy) for its use was found for any indication. Level B recommendation (probable efficacy) was proposed for fibromyalgia, MDD episode without drug resistance, and addiction/craving. Level C recommendation (possible efficacy) is proposed for chronic lower limb neuropathic pain secondary to spinal cord lesion. tDCS was found to be probably ineffective as a treatment for tinnitus and drug-resistant MDD.30 Some research has suggested that tDCS targeting the DLPFC is associated with cognitive improvements in healthy individuals as well as those with schizophrenia.44 tDCS treatment remains experimental and investigational.

Deep brain stimulation

DBS is a neurosurgical procedure that uses electrical current to directly modulate specific areas of the CNS. In terms of accurate, site-specific anatomical targeting, there can be little doubt of the superiority of DBS. DBS involves the placement of leads into the brain parenchyma. Image guidance techniques are used for accurate placement. DBS is a mainstay for the symptomatic treatment of treatment-resistant movement disorders such as Parkinson disease, essential tremor, and some dystonic disorders. It also has been studied as a potential treatment for chronic pain, cluster headache, Huntington disease, and Tourette syndrome.

For treating depression, researched targets include the subgenual cingulate gyrus (SCG), ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens, inferior thalamic peduncle, medial forebrain bundle, and the red nucleus.45 In systematic reviews, improvement of depression is greatest when DBS targets the subgenual cingulate cortex and the medial forebrain bundle.46

The major limitation of DBS for treating depression is the invasive nature of the procedure. Deep TMS can achieve noninvasive stimulation of the SCG and may be associated with fewer risks, fewer adverse events, and less collateral damage. However, given the evolving concept of abnormal neurologic circuits in depression, as our understanding of circuitry in pathological psychiatric processes increases, DBS may be an attractive option for personalized targeting of symptoms in some patients.

DBS may also be beneficial for severe, treatment-resistant OCD. Electrode implantation in the region of the internal capsule/ventral striatum, including the nucleus accumbens, is used47; there is little difference in placement as a treatment for OCD vs for movement disorders.48

Continue to: A critical review of 23 trials...

A critical review of 23 trials and case reports of DBS as a treatment for OCD demonstrated a 47.7% mean reduction in score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) and a mean response percentage (minimum 35% Y-BOCS reduction) of 58.2%.49 Most patients regained a normal quality of life after DBS.49 A more rigorous review of 15 meta-analyses of DBS found that conclusions about its efficacy or comparative effectiveness cannot be drawn.50 Because of the nature of neurosurgery, DBS has many potential complications, including cognitive changes, headache, infection, seizures, stroke, and hardware failure.

Vagus nerve stimulation

VNS, in which an implanted device stimulates the left vagus nerve with electrical impulses, was FDA-approved for treating chronic TRD in 2005.51 It had been approved for treatment-resistant epilepsy in 1997. In patients with epilepsy, VNS was shown to improve mood independent of seizure control.52 VNS requires a battery-powered pacemaker device to be implanted under the skin over the anterior chest wall, and a wire tunneled to an electrode is wrapped around the left vagus nerve in the neck.53 The pacemaker is then programmed, monitored, and reprogrammed to optimize response.

VNS is believed to stimulate deep brain nuclei that may play a role in depression.54 The onset of improvement is slow (it may take many months) but in carefully selected patients VNS can provide significant control of TRD. In addition to rare surgery-related complications such as a trauma to the vagal nerve and surrounding tissues (vocal cord paralysis, implant site infection, left facial nerve paralysis and Horner syndrome), VNS may cause hoarseness, dyspnea, and cough related to the intensity of the current output.51 Hypomania and mania were also reported; no suicidal behavior has been associated with VNS.51

Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulationIn noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) or transcutaneous VNS, an external handheld device is applied to the neck overlying the course of the vagus nerve to deliver a sinusoidal alternating current.55 nVNS is currently FDA-approved for treating migraine headaches.55,56 It has demonstrated actions on neurophysiology57 and inflammation in patients with MDD.58 Exploratory research has found a small beneficial effect in patients with depression.59,60 A lack of adequate reproducibility prevents this treatment from being more widely recommended, although attempts to standardize the field are evolving.61

Cranial electrical stimulation

Cranial electrical stimulation (CES) is an older form of electric stimulation developed in the 1970s. In CES, mild electrical pulses are delivered to the ear lobes bilaterally in an episodic fashion (usually 20 to 60 minutes once or twice daily). While CES can be considered a form of neuromodulation, it is not strictly interventional. Patients self-administer CES. The procedure has minimal effects on improving sleep, anxiety, and mood.62-66 Potential adverse effects include a tingling sensation in the ear lobes, lightheadedness, and fogginess. A review and meta-analysis of CES for treating addiction by Kirsch67 showed a wide range of symptoms responding positively to CES treatment, although this study was not peer-reviewed. Because of the low quality of nearly all research that evaluated CES, this form of electric stimulation cannot be viewed as an accepted treatment for any of its listed indications.

Continue to: Other neuromodulation techniques

Other

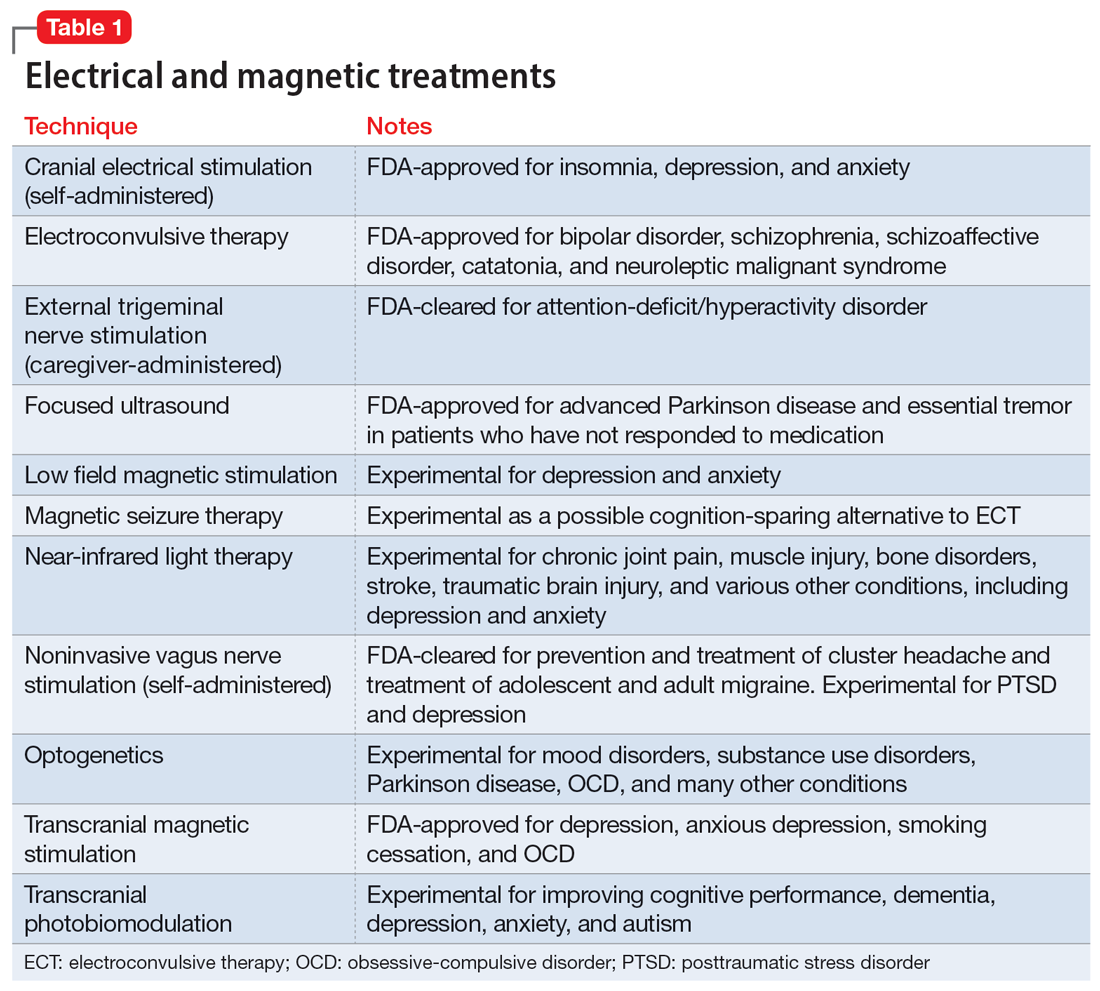

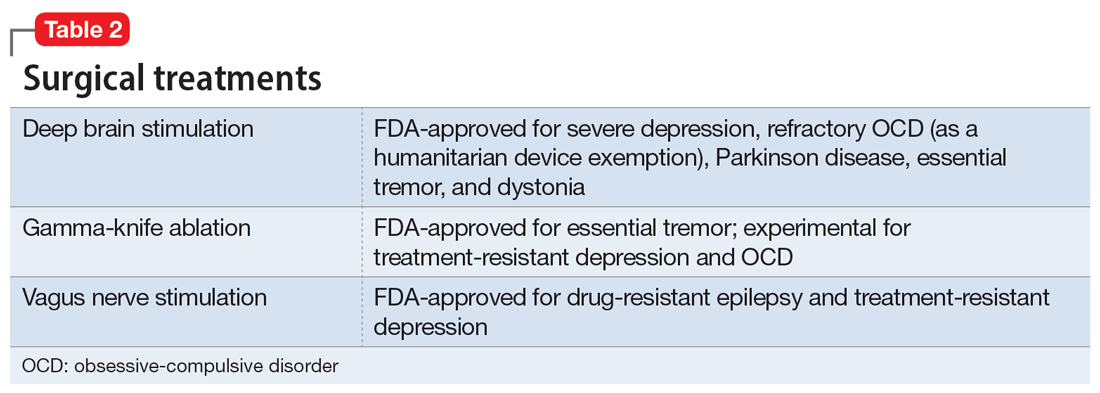

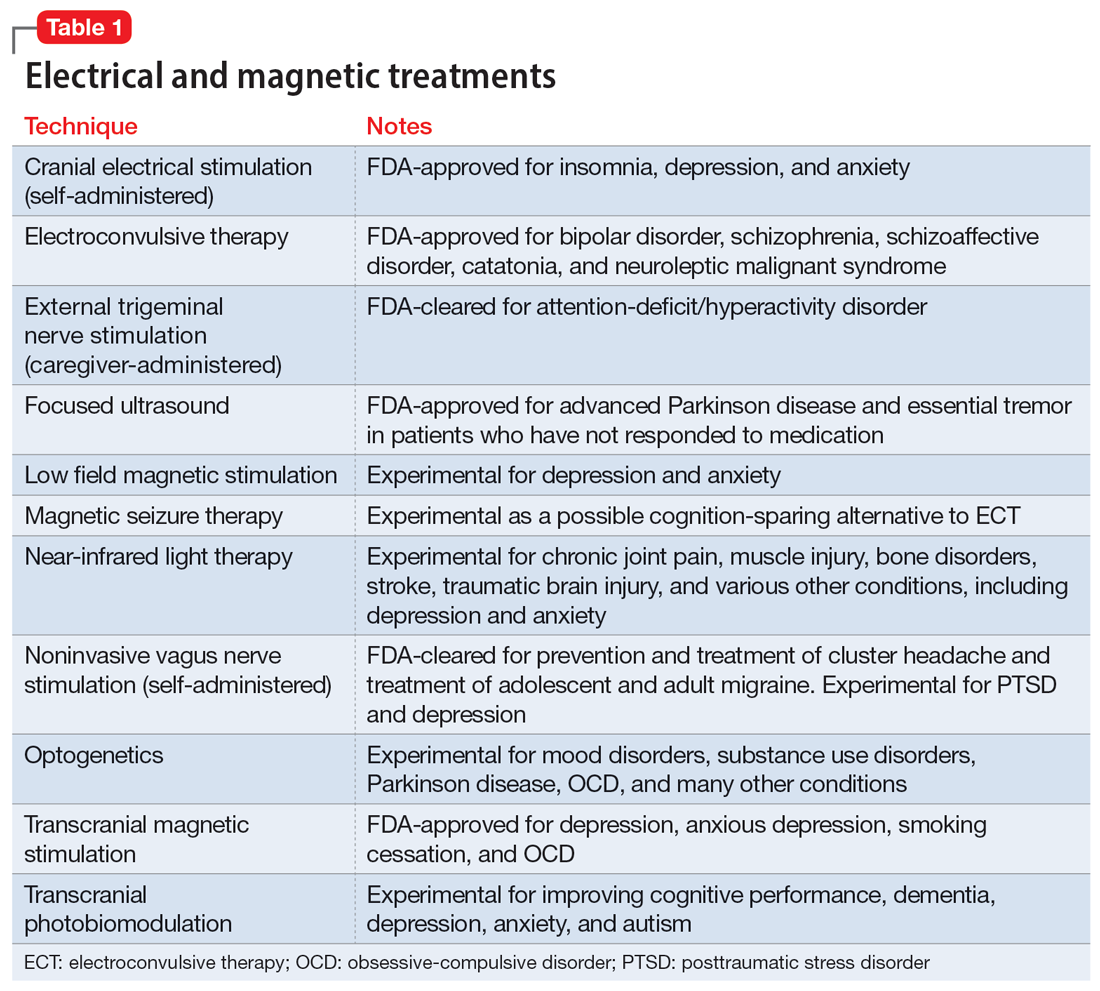

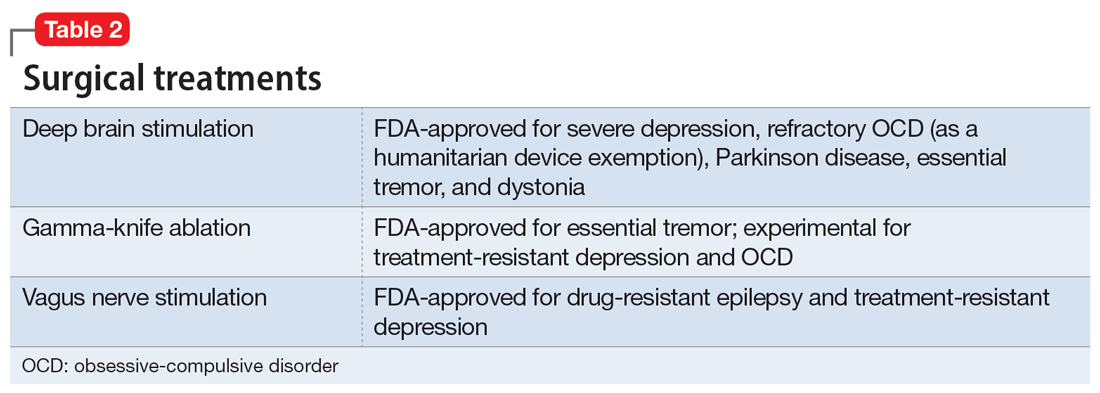

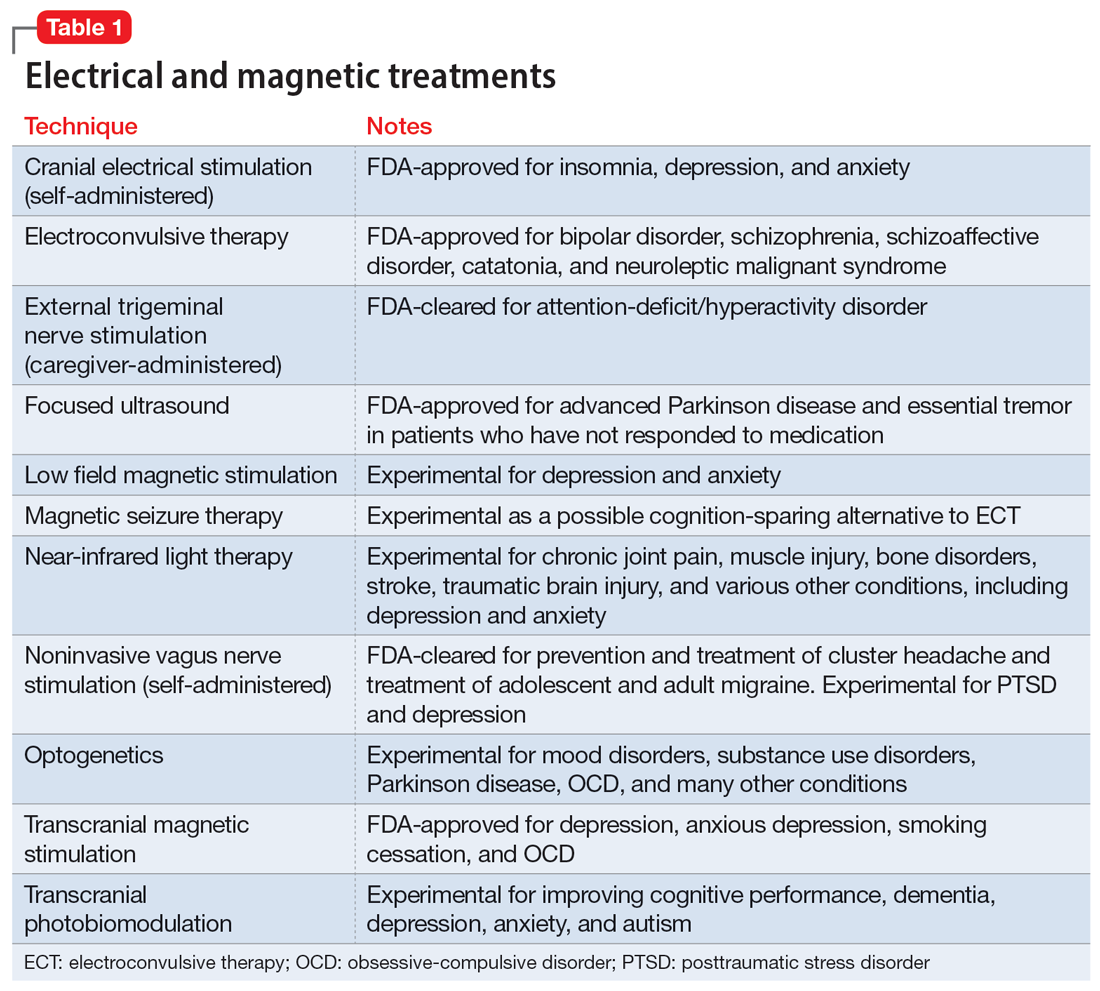

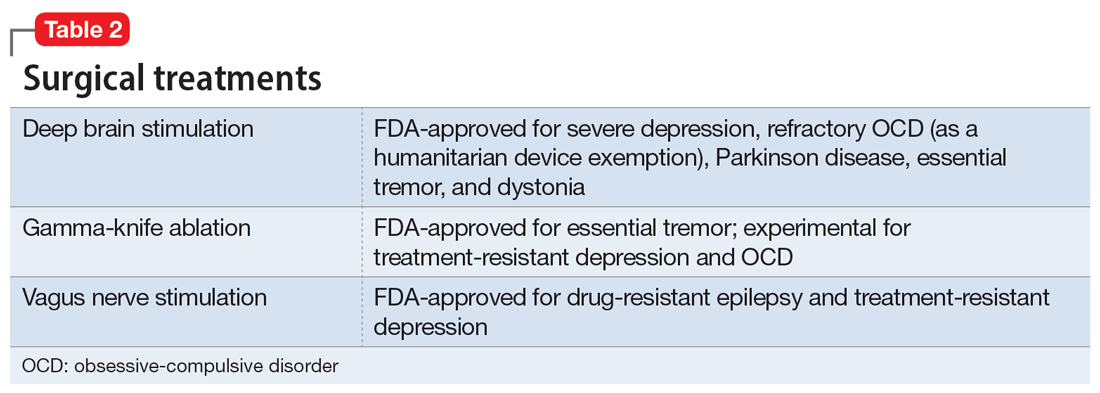

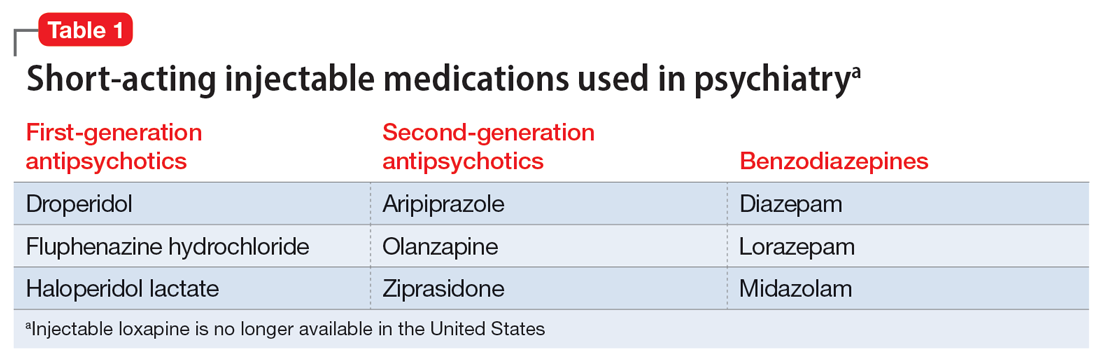

In addition to the forms of neuromodulation we have already described, there are many other techniques. Several are promising but not yet ready for clinical use. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the neuromodulation techniques described in this article as well as several that are under development.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a Chinese form of medical treatment that began >3,000 years ago; there are written descriptions of it from >2,000 years ago.68 It is based on the belief that there are channels within the body through which the Qi (vital energy or life force) flow, and that inserting fine needles into these channels via the skin can rebalance Qi.68 Modern mechanistic hypotheses invoke involvement of inflammatory or pain pathways.69 Acupuncture frequently uses electric stimulation (electro-acupuncture) to increase the potency of the procedure. Alternatively, in a related procedure (acupressure), pressure can replace the needle. Accreditation in acupuncture generally requires a master’s degree in traditional Chinese medicine but does not require any specific medical training. Acupuncture training courses for physicians are widely available.

All forms of acupuncture are experimental for a wide variety of mental and medical conditions. A meta-analysis found that most research of the utility of acupuncture for depression suffered from various forms of potential bias and was considered low quality.70 Nonetheless, active acupuncture was shown to be minimally superior to placebo acupuncture.70 A meta-analysis of acupuncture for preoperative anxiety71,72 and poststroke insomnia73 reported a similar low study quality. A study of 72 patients with primary insomnia revealed that acupuncture was more effective than sham acupuncture for most sleep measures.74

Psychiatry is increasingly integrating medical tools in addition to psychological tools. Pharmacology remains a cornerstone of biological psychiatry and this will not soon change. However, nonpharmacologic psychiatric treatments such as therapeutic neuromodulation are rapidly emerging. These and novel methods of medication administration may present a challenge to psychiatrists who do not have access to medical personnel or may have forgotten general medical skills.

Our 2-part article has highlighted several interventional psychiatry tools—old and new—that may interest clinicians and benefit patients. As a rule, such treatments are reserved for the most treatment-resistant, challenging psychiatric patients, those with hard-to-treat chronic conditions, and patients who are not helped by more commonly used treatments. An additional complication is that such treatments are frequently not appropriately researched, vetted, or FDA-approved, and therefore are higher risk. Appropriate clinical judgment is always necessary, and potential benefits must be thoroughly weighed against possible adverse effects.

Bottom Line

Several forms of neuromodulation, including electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation, may be beneficial for patients with certain treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Related Resources

- Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

- Sharma MS, Ang-Rabanes M, Selek S, et al. Neuromodulatory options for treatment-resistant depression. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):26-28,33-37.

1. Maloney TR, Dilkes-Hall IE, Vlok M, et al. Surgical amputation of a limb 31,000 years ago in Borneo. Nature. 2022;609(7927):547-551. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05160-8

2. The American Electro-Therapeutic Association. JAMA. 1893;21(14):500. doi:10.1001/jama.1893.02420660030004

3. The American Electro-Therapeutic Association. JAMA. 1894;23(15):590-591. doi:10.1001/jama.1894.02421200024006

4. Wexler A. The medical battery in the United States (1870-1920): electrotherapy at home and in the clinic. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2017;72(2):166-192. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrx001

5. Gazdag G, Ungvari GS. Electroconvulsive therapy: 80 years old and still going strong. World J Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):1-6. doi:10.5498/wjp.v9.i1.1

6. Barker AT, Jalinous R, Freeston IL. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex. Lancet. 1985;1(8437):1106-1107. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92413-4

7. Fink M. Historical article: autobiography of L. J. Meduna. Convuls Ther. 1985;1(1):43-57.

8. Suleman R. A brief history of electroconvulsive therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;16(1):6. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2020.160103

9. Ménard C, Hodes GE, Russo SJ. Pathogenesis of depression: insights from human and rodent studies. Neuroscience. 2016;321:138-162. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.053

10. Payne NA, Prudic J. Electroconvulsive therapy: part II: a biopsychosocial perspective. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(5):369-390. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000361278.73092.85

11. Tirmizi O, Raza A, Trevino K, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy: how modern techniques improve patient outcomes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(10):24-46.

12. Kolar D. Current status of electroconvulsive therapy for mood disorders: a clinical review. Evid Based Ment Health. 2017;20(1):12-14. doi:10.1136/eb-2016-102498

13. Andrade C. Active placebo, the parachute meta-analysis, the Nobel Prize, and the efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(2):21f13992. doi:10.4088/JCP.21f13992

14. Giacobbe P, Rakita U, Penner-Goeke K, et al. Improvements in health-related quality of life with electroconvulsive therapy: a meta-analysis. J ECT. 2018;34(2):87-94. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000486

15. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(12):1162-1172. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

16. Anand A, Mathew SJ, Sanacora G, et al. Ketamine versus ECT for nonpsychotic treatment-resistant major depression. N Engl J Med. 2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2302399

17. Takamiya A, Seki M, Kudo S, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2021;36(1):50-58. doi:10.1002/mds.28335

18. Singh R, Sharma R, Prakash J, et al. Magnetic seizure therapy. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30(Suppl 1):S320-S321. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.328841

19. Chen M, Yang X, Liu C, et al. Comparative efficacy and cognitive function of magnetic seizure therapy vs. electroconvulsive therapy for major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):437. doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01560-y

20. Cretaz E, Brunoni AR, Lafer B. Magnetic seizure therapy for unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:521398. doi:10.1155/2015/521398

21. George MS, Ketter TA, Post RM. Prefrontal cortex dysfunction in clinical depression. In: Nemeroff CB, Weiss JM, Schatzberg AF, et al, eds. Depression. 2nd ed. Wiley Online Library; 1994:59-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/depr.3050020202

22. George MS, Wassermann EM, Williams WA, et al. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. Neuroreport. 1995;6(14):1853-1856.

23. O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1208-1216.

24. Clinical TMS Society. TMS devices. Accessed January 2, 2023. https://www.clinicaltmssociety.org/devices

25. Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Ball TM, Samara Z, et al. Mapping neural circuit biotypes to symptoms and behavioral dimensions of depression and anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91(6):561-571. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.06.024

26. Siddiqi SH, Taylor SF, Cooke D, et al. Distinct symptom-specific treatment targets for circuit-based neuromodulation. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(5):435-446. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19090915

27. Williams LM. Defining biotypes for depression and anxiety based on large-scale circuit dysfunction: a theoretical review of the evidence and future directions for clinical translation. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(1):9-24. doi:10.1002/da.22556

28. Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):28-38. doi:10.1038/nm.4246

29. Cohen SL, Bikson M, Badran BW, et al. A visual and narrative timeline of US FDA milestones for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) devices. Brain Stimul. 2022;15(1):73-75. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2021.11.010

30. Lefaucheur JP, Antal A, Ayache SS, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(1):56-92. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2016.10.087

31. Li R, He Y, Qin W, et al. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2022;36(7):395-404. doi:10.1177/15459683221095034

32. Leung A, Shirvalkar P, Chen R, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for pain, headache, and comorbid depression: INS-NANS expert consensus panel review and recommendation. Neuromodulation. 2020;23(3):267-290. doi:10.1111/ner.13094

33. Carmi L, Tendler A, Bystritsky A, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(11):931-938. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101180

34. Harel M, Perini I, Kämpe R, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in alcohol dependence: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled proof-of-concept trial targeting the medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91(12):1061-1069. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.11.020

35. Folmer RL, Theodoroff SM, Casiana L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment for chronic tinnitus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(8):716-722. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1219

36. Cole EJ, Phillips AL, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy (SNT): a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):132-141. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.20101429

37. Wilson S, Croarkin PE, Aaronson ST, et al. Systematic review of preservation TMS that includes continuation, maintenance, relapse-prevention, and rescue TMS. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:79-88. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.040

38. Perera T, George MS, Grammer G, et al. The Clinical TMS Society consensus review and treatment recommendations for TMS therapy for major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(3):336-346. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2016.03.010

39. Blumberger DM, Vila-Rodriguez F, Thorpe KE, et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): a randomized non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1683-1692. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30295-2

40. Nitsche MA, Cohen LG, Wassermann EM, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: state of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 2008;1(3):206-223. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004

41. Priori A, Hallett M, Rothwell JC. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation? Brain Stimul. 2009;2(4):241-245.

42. Priori A, Berardelli A, Rona S, et al. Polarization of the human motor cortex through the scalp. Neuroreport. 1998;9(10):2257-2260. doi:10.1097/00001756-199807130-00020

43. Nitsche MA, Liebetanz D, Antal A, et al. Modulation of cortical excitability by weak direct current stimulation-- technical, safety and functional aspects. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;56:255-276. doi:10.1016/s1567-424x(09)70230-2

44. Agarwal SM, Venkataram Shivakumar V, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation in schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(3):118-125.

45. Drobisz D, Damborská A. Deep brain stimulation targets for treating depression. Behav Brain Res. 2019;359:266-273. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2018.11.004

46. Kisely S, Li A, Warren N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of deep brain stimulation for depression. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(5):468-480. doi:10.1002/da.22746

47. Blomstedt P, Sjöberg RL, Hansson M, et al. Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(6):e245-e253. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2012.10.006

48. Denys D, Mantione M, Figee M, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1061-1068. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.122

49. van Westen M, Rietveld E, Figee M, et al. Clinical outcome and mechanisms of deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2015;2(2):41-48. doi:10.1007/s40473-015-0036-3

50. Papageorgiou PN, Deschner J, Papageorgiou SN. Effectiveness and adverse effects of deep brain stimulation: umbrella review of meta-analyses. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2017;78(2):180-190. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1592158

51. O’Reardon JP, Cristancho P, Peshek AD. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and treatment of depression: to the brainstem and beyond. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):54-63.

52. Harden CL, Pulver MC, Ravdin LD, et al. A pilot study of mood in epilepsy patients treated with vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1(2):93-99. doi:10.1006/ebeh.2000.0046

53. Giordano F, Zicca A, Barba C, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation: surgical technique of implantation and revision and related morbidity. Epilepsia. 2017;58(S1):85-90. doi:10.1111/epi.13687

54. George MS, Nahas Z, Bohning DE, et al. Mechanisms of action of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Clin Neurosci Res. 2004;4(1-2):71-79.

55. Nesbitt AD, Marin JCA, Tompkins E, et al. Initial use of a novel noninvasive vagus nerve stimulator for cluster headache treatment. Neurology. 2015;84:1249-1253. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001394

56. Goadsby PJ, Grosberg BM, Mauskop A, et al. Effect of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation on acute migraine: an open-label pilot study. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:986-993. doi:10.1177/0333102414524494

57. Fang J, Rong P, Hong Y, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates default mode network in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):266-273. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.03.025

58. Liu CH, Yang MH, Zhang GZ, et al. Neural networks and the anti-inflammatory effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in depression. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):54. doi:10.1186/s12974-020-01732-5

59. Hein E, Nowak M, Kiess O, et al. Auricular transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in depressed patients: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2013;120(5):821-827. doi:10.1007/s00702-012-0908-6

60. Rong P, Liu J, Wang L, et al. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder: a nonrandomized controlled pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:172-179. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.031

61. Farmer AD, Strzelczyk A, Finisguerra A, et al. International consensus based review and recommendations for minimum reporting standards in research on transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (Version 2020). Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;14:568051. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2020.568051

62. Amr M, El-Wasify M, Elmaadawi AZ, et al. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation for the treatment of chronically symptomatic bipolar patients. J ECT. 2013;29(2):e31-e32. doi:10.1097/YCT.0b013e31828a344d

63. Kirsch DL, Nichols F. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation for treatment of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):169-176. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2013.01.006

64. Lande RG, Gragnani C. Efficacy of cranial electric stimulation for the treatment of insomnia: a randomized pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21(1):8-13. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2012.11.007

65. Ou Y, Li, C. Sertraline combined alpha-stim clinical observations on the treatment of 30 cases of generalized anxiety disorder. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy. 2015;24(17):73-75.

66. Price L, Briley J, Haltiwanger S, et al. A meta-analysis of cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;135:119-134. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.043

67. Kirsch D, Gilula M. CES in the treatment of addictions: a review and meta-analysis. Pract Pain Manag. 2007;7(9).

68. Hao JJ, Mittelman M. Acupuncture: past, present, and future. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014;3(4):6-8. doi:10.7453/gahmj.2014.042

69. Napadow V, Ahn A, Longhurst J, et al. The status and future of acupuncture mechanism research. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(7):861-869. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.SAR-3

70. Smith CA, Armour M, Lee MS, et al. Acupuncture for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3(3):CD004046. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004046.pub4

71. Tong QY, Liu R, Zhang K, et al. Can acupuncture therapy reduce preoperative anxiety? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Integr Med. 2021;19(1):20-28. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2020.10.007

72. Usichenko TI, Hua K, Cummings M, et al. Auricular stimulation for preoperative anxiety – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Clin Anesth. 2022;76:110581. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110581

73. Zhou L, Hu X, Yu Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture in the treatment of poststroke insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of twenty-six randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:5188311. doi:10.1155/2022/5188311

74. Yin X, Gou M, Xu J, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture treatment on primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Med. 2017;37:193-200. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.02.012

While most psychiatric treatments have traditionally consisted of pharmacotherapy with oral medications, a better understanding of the pathophysiology underlying many mental illnesses has led to the recent increased use of treatments that require specialized administration and the creation of a subspecialty called interventional psychiatry. In Part 1 of this 2-part article (“Interventional psychiatry [Part 1],"

Neuromodulation treatments

Neuromodulation—the alteration of nerve activity through targeted delivery of a stimulus, such as electrical stimulation, to specific neurologic sites—is an increasingly common approach to treating a variety of psychiatric conditions. The use of some form of neuromodulation as a medical treatment has a long history (Box1-6). Modern electric neuromodulation began in the 1930s with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The 1960s saw the introduction of deep brain stimulation (DBS), spinal cord stimulation, and later, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Target-specific noninvasive brain stimulation became possible with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). These approaches are used for treating major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety disorders, and insomnia. Nearly all these neuromodulatory approaches require clinicians to undergo special training and patients to participate in an invasive procedure. These factors also increase cost. Nonetheless, the high rates of success of some of these approaches have led to relatively rapid and widespread acceptance.

Box

The depth and breadth of human anatomical knowledge has evolved over millennia. The time frame “thousands of years” may appear to be an overstatement, but evidence exists for successful therapeutic limb amputation as early as 31,000 years ago.1 This suggests that human knowledge of bone, muscle, and blood supply was developed much earlier than initially believed. Early Homo sapiens were altering the body—regulating or adjusting it— to serve a purpose; in this case, the purpose was survival.

In 46 AD, electrical modulation was introduced by Scribonius Largus, a physician in court of the emperor Tiberius, who used “torpedoes” (most likely electric eels) to treat headaches and pain from arthritis. Loosely, these early clinicians were modulating human function.

In the late 1800s, electrotherapeutics was a growing branch of medicine, with its own national organization—the American ElectroTherapeutic Association.2 In that era, electricity was novel, powerful, and seen as “the future.” Because such novel therapeutics were offered by both mainstream and dubious sources,3 “many of these products were marketed with the promise of curing everything from cancer to headaches.”4

Modern electric neuromodulation began in the 1930s with electroconvulsive therapy,5 followed by deep brain stimulation and spinal cord stimulation in the 1960s. Target-specific noninvasive brain stimulation became possible when Anthony Barker’s team developed the first device that permitted transcranial magnetic stimulation in 1985.6

Electroconvulsive therapy

In ECT, electric current is applied to the brain to induce a self-limiting seizure. It is the oldest and best-known interventional psychiatric treatment. ECT can also be considered one of the first treatments specifically developed to address pathophysiologic changes. In 1934, Ladislas J. Meduna, who had observed in neuropathologic studies that microglia were more numerous in patients with epilepsy compared with patients with schizophrenia, injected a patient who had been hospitalized with catatonia for 4 years with camphor, a proconvulsant.7 After 5 seizures, the patient began to recover. The therapeutic use of electricity was subsequently developed and optimized in animal models, and first used on human patients in Italy in 1939 and in the United States in 1940.8 The link between psychiatric illness and microglia, which was initially observed nearly a century ago, is making a comeback, as excessive microglial activation has been demonstrated in animal and human models of depression.9

Administering ECT requires specialized equipment, anesthesia, physician training, and nursing observation. ECT also has a negative public image.10 All of these factors conspire to reduce the availability of ECT. Despite this, approximately 100,000 patients in the United States and >1 million worldwide receive ECT each year.10 Patients generally require 6 to 12 ECT treatments11 to achieve sufficient response and may require additional maintenance treatments.12

Although ECT is used to treat psychiatric illnesses ranging from mood disorders to psychotic disorders and catatonia, it is mainly employed to treat people with severe treatment-resistant depression (TRD).13 ECT is associated with significant improvements in depressive symptoms and improvements in quality of life.14 It is superior to other treatments for TRD, such as ketamine,15 though a recent study did not show IV ketamine inferiority.16 ECT is also used to treat other neuropsychiatric disorders, such as Parkinson disease.17

Clinicians have explored alternate methods of inducing therapeutic seizures. Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) utilizes a modified magnetic stimulation device to deliver a higher energy in such a way to induce a generalized seizure under anesthesia.18 While patients receiving MST generally experience fewer adverse effects than with ECT, the procedure may be equal to19 or less effective than ECT.20

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

In neuroimaging research, certain aberrant brain circuits have been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression.21 Specifically, anatomical and functional imaging suggests connections in the prefrontal cortex are involved in the depression process. In TMS, a series of magnetic pulses are administered via the scalp to stimulate neurons in areas of the brain associated with MDD. Early case reports on using TMS to stimulate the prefrontal cortex found significant improvement of symptoms in patients with depression.22 These promising results spurred great interest in the procedure. Over time, the dose and duration of stimulation has increased, along with FDA-approved indications. TMS was first FDA-approved for TRD.23 Although the primary endpoint of the initial clinical trial did not meet criteria for FDA approval, TMS did result in improvement across multiple other measures of depression.23 After the FDA approved the first TMS device, numerous companies began to produce TMS technology. Most of these companies manufacture devices with the figure-of-eight coil, with 1 company producing the Hesed-coil helmet.24

Continue to: An unintended outcome...

An unintended outcome of the increased interest in TMS has been an increased understanding of brain regions involved in psychiatric illness. TMS was able to bring knowledge of mental health from synapses to circuits.25 Work in this area has further stratified the circuits involved in the manifestation of symptom clusters in depression.26 The exact taxonomy of these brain circuits has not been fully realized, but the default mode, salience, attention, cognitive control, and other circuits have been shown to be involved in specific symptom presentations.26,27 These circuits can be hyperactive, hypoactive, hyperconnected, or hypoconnected, with the aberrancies compared to normal controls resulting in symptoms of psychiatric illness.28

This enhanced understanding of brain function has led to further research and development of protocols and subsequent FDA approval of TMS for OCD, anxious depression, and smoking cessation.29 In addition, it has allowed for a proliferation of off-label uses for TMS, including (but not limited to) tinnitus, pain, migraines, and various substance use disorders.30 TMS treatment for these conditions involves stimulation of specific anatomical brain regions that are thought to play a role in the pathology of the target disorder. For example, subthreshold stimulation of the motor cortex has shown some utility in managing symptoms of pain disorders and movement disorders,31,32 the ventromedial prefrontal cortex has been implicated in disorders in the OCD spectrum,33 stimulation of the frontal poles may help treat substance use disorders,34 and the auditory cortex has been a target for treating tinnitus and auditory hallucinations.35

The location of stimulation for treating depression has evolved. The Talairach-Tournoux coordinate system has been used to determine the location of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in relation to the motor cortex. This was measured to be 5 cm from the motor hotspot and subsequently became “the 5.5 cm rule,” taking skull convexity into account. The treatment paradigm for the Hesed coil also uses a measurement from the motor hotspot. Another commonly used methodology for coil placement involves using the 10 to 20 EEG coordinate system to individualize scalp landmarks. In this method, the F3 location corresponds most accurately to the DLPFC target. More recently, using fMRI-guided navigation for coil placement has been shown to lead to a significant reduction in depressive symptoms.36

For depression, the initial recommended course of treatment is 6 weeks, but most improvement is seen in the first 2 to 3 weeks.14 Therefore, many clinicians administer an initial course of 3 weeks unless the response is inadequate, in which case a 6-week course is administered. Many patients require ongoing maintenance treatment, which can be weekly or monthly based on response.37

Research to determine the optimal TMS dose for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms is ongoing. Location, intensity of stimulation, and pulse are the components of stimulation. The pulse can be subdivided into frequency, pattern (single pulse, standard, burst), train (numbers of pulse groups), interval between trains, and total number of pulses per session. The Clinical TMS Society has published TMS protocols.38 The standard intensity of stimulation is 120% of the motor threshold (MT), which is defined as the amount of stimulation over the motor cortex required to produce movement in the extensor hallucis longus. Although treatment for depression traditionally utilizes rapid TMS (3,000 pulses delivered per session at a frequency of 10 Hz in 4-second trains), in controlled studies, accelerated protocols such as intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS; standard stimulation parameters: triplet 50 Hz bursts at 5 Hz, with an interval of 8 seconds for 600 pulses per session) have shown noninferiority.36,39

Recent research has explored fMRI-guided iTBS in an even more accelerated format. The Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy trial involved 1,800 pulses per session for 10 sessions a day for 5 days at 90% MT.36 This treatment paradigm was shown to be more effective than standard protocols and was FDA-approved in 2022. Although this specific iTBS protocol exhibited encouraging results, the need for fMRI for adequate delivery might limit its use.

Continue to: Transcranial direct current stimulation

Transcranial direct current stimulation

Therapeutic noninvasive brain stimulation technology is plausible due to the relative lack of adverse effects and ease of administration. In transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), a low-intensity, constant electric current is delivered to stimulate the brain via electrodes attached to the scalp. tDCS modulates spontaneous neuronal network activity40,41 and induces polarization of resting membrane potential at the neuronal level,42 though the exact mechanism is yet to be proven. N-methyl-

tDCS has been suggested as a treatment for various psychiatric and medical conditions. However, the small sample sizes and experimental design of published studies have limited tDCS from being clinically recommended.30 No recommendation of Level A (definite efficacy) for its use was found for any indication. Level B recommendation (probable efficacy) was proposed for fibromyalgia, MDD episode without drug resistance, and addiction/craving. Level C recommendation (possible efficacy) is proposed for chronic lower limb neuropathic pain secondary to spinal cord lesion. tDCS was found to be probably ineffective as a treatment for tinnitus and drug-resistant MDD.30 Some research has suggested that tDCS targeting the DLPFC is associated with cognitive improvements in healthy individuals as well as those with schizophrenia.44 tDCS treatment remains experimental and investigational.

Deep brain stimulation

DBS is a neurosurgical procedure that uses electrical current to directly modulate specific areas of the CNS. In terms of accurate, site-specific anatomical targeting, there can be little doubt of the superiority of DBS. DBS involves the placement of leads into the brain parenchyma. Image guidance techniques are used for accurate placement. DBS is a mainstay for the symptomatic treatment of treatment-resistant movement disorders such as Parkinson disease, essential tremor, and some dystonic disorders. It also has been studied as a potential treatment for chronic pain, cluster headache, Huntington disease, and Tourette syndrome.

For treating depression, researched targets include the subgenual cingulate gyrus (SCG), ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens, inferior thalamic peduncle, medial forebrain bundle, and the red nucleus.45 In systematic reviews, improvement of depression is greatest when DBS targets the subgenual cingulate cortex and the medial forebrain bundle.46

The major limitation of DBS for treating depression is the invasive nature of the procedure. Deep TMS can achieve noninvasive stimulation of the SCG and may be associated with fewer risks, fewer adverse events, and less collateral damage. However, given the evolving concept of abnormal neurologic circuits in depression, as our understanding of circuitry in pathological psychiatric processes increases, DBS may be an attractive option for personalized targeting of symptoms in some patients.

DBS may also be beneficial for severe, treatment-resistant OCD. Electrode implantation in the region of the internal capsule/ventral striatum, including the nucleus accumbens, is used47; there is little difference in placement as a treatment for OCD vs for movement disorders.48

Continue to: A critical review of 23 trials...

A critical review of 23 trials and case reports of DBS as a treatment for OCD demonstrated a 47.7% mean reduction in score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) and a mean response percentage (minimum 35% Y-BOCS reduction) of 58.2%.49 Most patients regained a normal quality of life after DBS.49 A more rigorous review of 15 meta-analyses of DBS found that conclusions about its efficacy or comparative effectiveness cannot be drawn.50 Because of the nature of neurosurgery, DBS has many potential complications, including cognitive changes, headache, infection, seizures, stroke, and hardware failure.

Vagus nerve stimulation

VNS, in which an implanted device stimulates the left vagus nerve with electrical impulses, was FDA-approved for treating chronic TRD in 2005.51 It had been approved for treatment-resistant epilepsy in 1997. In patients with epilepsy, VNS was shown to improve mood independent of seizure control.52 VNS requires a battery-powered pacemaker device to be implanted under the skin over the anterior chest wall, and a wire tunneled to an electrode is wrapped around the left vagus nerve in the neck.53 The pacemaker is then programmed, monitored, and reprogrammed to optimize response.

VNS is believed to stimulate deep brain nuclei that may play a role in depression.54 The onset of improvement is slow (it may take many months) but in carefully selected patients VNS can provide significant control of TRD. In addition to rare surgery-related complications such as a trauma to the vagal nerve and surrounding tissues (vocal cord paralysis, implant site infection, left facial nerve paralysis and Horner syndrome), VNS may cause hoarseness, dyspnea, and cough related to the intensity of the current output.51 Hypomania and mania were also reported; no suicidal behavior has been associated with VNS.51

Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulationIn noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) or transcutaneous VNS, an external handheld device is applied to the neck overlying the course of the vagus nerve to deliver a sinusoidal alternating current.55 nVNS is currently FDA-approved for treating migraine headaches.55,56 It has demonstrated actions on neurophysiology57 and inflammation in patients with MDD.58 Exploratory research has found a small beneficial effect in patients with depression.59,60 A lack of adequate reproducibility prevents this treatment from being more widely recommended, although attempts to standardize the field are evolving.61

Cranial electrical stimulation

Cranial electrical stimulation (CES) is an older form of electric stimulation developed in the 1970s. In CES, mild electrical pulses are delivered to the ear lobes bilaterally in an episodic fashion (usually 20 to 60 minutes once or twice daily). While CES can be considered a form of neuromodulation, it is not strictly interventional. Patients self-administer CES. The procedure has minimal effects on improving sleep, anxiety, and mood.62-66 Potential adverse effects include a tingling sensation in the ear lobes, lightheadedness, and fogginess. A review and meta-analysis of CES for treating addiction by Kirsch67 showed a wide range of symptoms responding positively to CES treatment, although this study was not peer-reviewed. Because of the low quality of nearly all research that evaluated CES, this form of electric stimulation cannot be viewed as an accepted treatment for any of its listed indications.

Continue to: Other neuromodulation techniques

Other

In addition to the forms of neuromodulation we have already described, there are many other techniques. Several are promising but not yet ready for clinical use. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the neuromodulation techniques described in this article as well as several that are under development.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a Chinese form of medical treatment that began >3,000 years ago; there are written descriptions of it from >2,000 years ago.68 It is based on the belief that there are channels within the body through which the Qi (vital energy or life force) flow, and that inserting fine needles into these channels via the skin can rebalance Qi.68 Modern mechanistic hypotheses invoke involvement of inflammatory or pain pathways.69 Acupuncture frequently uses electric stimulation (electro-acupuncture) to increase the potency of the procedure. Alternatively, in a related procedure (acupressure), pressure can replace the needle. Accreditation in acupuncture generally requires a master’s degree in traditional Chinese medicine but does not require any specific medical training. Acupuncture training courses for physicians are widely available.

All forms of acupuncture are experimental for a wide variety of mental and medical conditions. A meta-analysis found that most research of the utility of acupuncture for depression suffered from various forms of potential bias and was considered low quality.70 Nonetheless, active acupuncture was shown to be minimally superior to placebo acupuncture.70 A meta-analysis of acupuncture for preoperative anxiety71,72 and poststroke insomnia73 reported a similar low study quality. A study of 72 patients with primary insomnia revealed that acupuncture was more effective than sham acupuncture for most sleep measures.74

Psychiatry is increasingly integrating medical tools in addition to psychological tools. Pharmacology remains a cornerstone of biological psychiatry and this will not soon change. However, nonpharmacologic psychiatric treatments such as therapeutic neuromodulation are rapidly emerging. These and novel methods of medication administration may present a challenge to psychiatrists who do not have access to medical personnel or may have forgotten general medical skills.

Our 2-part article has highlighted several interventional psychiatry tools—old and new—that may interest clinicians and benefit patients. As a rule, such treatments are reserved for the most treatment-resistant, challenging psychiatric patients, those with hard-to-treat chronic conditions, and patients who are not helped by more commonly used treatments. An additional complication is that such treatments are frequently not appropriately researched, vetted, or FDA-approved, and therefore are higher risk. Appropriate clinical judgment is always necessary, and potential benefits must be thoroughly weighed against possible adverse effects.

Bottom Line

Several forms of neuromodulation, including electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation, may be beneficial for patients with certain treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Related Resources

- Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

- Sharma MS, Ang-Rabanes M, Selek S, et al. Neuromodulatory options for treatment-resistant depression. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):26-28,33-37.

While most psychiatric treatments have traditionally consisted of pharmacotherapy with oral medications, a better understanding of the pathophysiology underlying many mental illnesses has led to the recent increased use of treatments that require specialized administration and the creation of a subspecialty called interventional psychiatry. In Part 1 of this 2-part article (“Interventional psychiatry [Part 1],"

Neuromodulation treatments

Neuromodulation—the alteration of nerve activity through targeted delivery of a stimulus, such as electrical stimulation, to specific neurologic sites—is an increasingly common approach to treating a variety of psychiatric conditions. The use of some form of neuromodulation as a medical treatment has a long history (Box1-6). Modern electric neuromodulation began in the 1930s with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The 1960s saw the introduction of deep brain stimulation (DBS), spinal cord stimulation, and later, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Target-specific noninvasive brain stimulation became possible with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). These approaches are used for treating major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety disorders, and insomnia. Nearly all these neuromodulatory approaches require clinicians to undergo special training and patients to participate in an invasive procedure. These factors also increase cost. Nonetheless, the high rates of success of some of these approaches have led to relatively rapid and widespread acceptance.

Box

The depth and breadth of human anatomical knowledge has evolved over millennia. The time frame “thousands of years” may appear to be an overstatement, but evidence exists for successful therapeutic limb amputation as early as 31,000 years ago.1 This suggests that human knowledge of bone, muscle, and blood supply was developed much earlier than initially believed. Early Homo sapiens were altering the body—regulating or adjusting it— to serve a purpose; in this case, the purpose was survival.

In 46 AD, electrical modulation was introduced by Scribonius Largus, a physician in court of the emperor Tiberius, who used “torpedoes” (most likely electric eels) to treat headaches and pain from arthritis. Loosely, these early clinicians were modulating human function.

In the late 1800s, electrotherapeutics was a growing branch of medicine, with its own national organization—the American ElectroTherapeutic Association.2 In that era, electricity was novel, powerful, and seen as “the future.” Because such novel therapeutics were offered by both mainstream and dubious sources,3 “many of these products were marketed with the promise of curing everything from cancer to headaches.”4

Modern electric neuromodulation began in the 1930s with electroconvulsive therapy,5 followed by deep brain stimulation and spinal cord stimulation in the 1960s. Target-specific noninvasive brain stimulation became possible when Anthony Barker’s team developed the first device that permitted transcranial magnetic stimulation in 1985.6

Electroconvulsive therapy

In ECT, electric current is applied to the brain to induce a self-limiting seizure. It is the oldest and best-known interventional psychiatric treatment. ECT can also be considered one of the first treatments specifically developed to address pathophysiologic changes. In 1934, Ladislas J. Meduna, who had observed in neuropathologic studies that microglia were more numerous in patients with epilepsy compared with patients with schizophrenia, injected a patient who had been hospitalized with catatonia for 4 years with camphor, a proconvulsant.7 After 5 seizures, the patient began to recover. The therapeutic use of electricity was subsequently developed and optimized in animal models, and first used on human patients in Italy in 1939 and in the United States in 1940.8 The link between psychiatric illness and microglia, which was initially observed nearly a century ago, is making a comeback, as excessive microglial activation has been demonstrated in animal and human models of depression.9

Administering ECT requires specialized equipment, anesthesia, physician training, and nursing observation. ECT also has a negative public image.10 All of these factors conspire to reduce the availability of ECT. Despite this, approximately 100,000 patients in the United States and >1 million worldwide receive ECT each year.10 Patients generally require 6 to 12 ECT treatments11 to achieve sufficient response and may require additional maintenance treatments.12

Although ECT is used to treat psychiatric illnesses ranging from mood disorders to psychotic disorders and catatonia, it is mainly employed to treat people with severe treatment-resistant depression (TRD).13 ECT is associated with significant improvements in depressive symptoms and improvements in quality of life.14 It is superior to other treatments for TRD, such as ketamine,15 though a recent study did not show IV ketamine inferiority.16 ECT is also used to treat other neuropsychiatric disorders, such as Parkinson disease.17

Clinicians have explored alternate methods of inducing therapeutic seizures. Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) utilizes a modified magnetic stimulation device to deliver a higher energy in such a way to induce a generalized seizure under anesthesia.18 While patients receiving MST generally experience fewer adverse effects than with ECT, the procedure may be equal to19 or less effective than ECT.20

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

In neuroimaging research, certain aberrant brain circuits have been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression.21 Specifically, anatomical and functional imaging suggests connections in the prefrontal cortex are involved in the depression process. In TMS, a series of magnetic pulses are administered via the scalp to stimulate neurons in areas of the brain associated with MDD. Early case reports on using TMS to stimulate the prefrontal cortex found significant improvement of symptoms in patients with depression.22 These promising results spurred great interest in the procedure. Over time, the dose and duration of stimulation has increased, along with FDA-approved indications. TMS was first FDA-approved for TRD.23 Although the primary endpoint of the initial clinical trial did not meet criteria for FDA approval, TMS did result in improvement across multiple other measures of depression.23 After the FDA approved the first TMS device, numerous companies began to produce TMS technology. Most of these companies manufacture devices with the figure-of-eight coil, with 1 company producing the Hesed-coil helmet.24

Continue to: An unintended outcome...

An unintended outcome of the increased interest in TMS has been an increased understanding of brain regions involved in psychiatric illness. TMS was able to bring knowledge of mental health from synapses to circuits.25 Work in this area has further stratified the circuits involved in the manifestation of symptom clusters in depression.26 The exact taxonomy of these brain circuits has not been fully realized, but the default mode, salience, attention, cognitive control, and other circuits have been shown to be involved in specific symptom presentations.26,27 These circuits can be hyperactive, hypoactive, hyperconnected, or hypoconnected, with the aberrancies compared to normal controls resulting in symptoms of psychiatric illness.28

This enhanced understanding of brain function has led to further research and development of protocols and subsequent FDA approval of TMS for OCD, anxious depression, and smoking cessation.29 In addition, it has allowed for a proliferation of off-label uses for TMS, including (but not limited to) tinnitus, pain, migraines, and various substance use disorders.30 TMS treatment for these conditions involves stimulation of specific anatomical brain regions that are thought to play a role in the pathology of the target disorder. For example, subthreshold stimulation of the motor cortex has shown some utility in managing symptoms of pain disorders and movement disorders,31,32 the ventromedial prefrontal cortex has been implicated in disorders in the OCD spectrum,33 stimulation of the frontal poles may help treat substance use disorders,34 and the auditory cortex has been a target for treating tinnitus and auditory hallucinations.35

The location of stimulation for treating depression has evolved. The Talairach-Tournoux coordinate system has been used to determine the location of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in relation to the motor cortex. This was measured to be 5 cm from the motor hotspot and subsequently became “the 5.5 cm rule,” taking skull convexity into account. The treatment paradigm for the Hesed coil also uses a measurement from the motor hotspot. Another commonly used methodology for coil placement involves using the 10 to 20 EEG coordinate system to individualize scalp landmarks. In this method, the F3 location corresponds most accurately to the DLPFC target. More recently, using fMRI-guided navigation for coil placement has been shown to lead to a significant reduction in depressive symptoms.36

For depression, the initial recommended course of treatment is 6 weeks, but most improvement is seen in the first 2 to 3 weeks.14 Therefore, many clinicians administer an initial course of 3 weeks unless the response is inadequate, in which case a 6-week course is administered. Many patients require ongoing maintenance treatment, which can be weekly or monthly based on response.37

Research to determine the optimal TMS dose for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms is ongoing. Location, intensity of stimulation, and pulse are the components of stimulation. The pulse can be subdivided into frequency, pattern (single pulse, standard, burst), train (numbers of pulse groups), interval between trains, and total number of pulses per session. The Clinical TMS Society has published TMS protocols.38 The standard intensity of stimulation is 120% of the motor threshold (MT), which is defined as the amount of stimulation over the motor cortex required to produce movement in the extensor hallucis longus. Although treatment for depression traditionally utilizes rapid TMS (3,000 pulses delivered per session at a frequency of 10 Hz in 4-second trains), in controlled studies, accelerated protocols such as intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS; standard stimulation parameters: triplet 50 Hz bursts at 5 Hz, with an interval of 8 seconds for 600 pulses per session) have shown noninferiority.36,39

Recent research has explored fMRI-guided iTBS in an even more accelerated format. The Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy trial involved 1,800 pulses per session for 10 sessions a day for 5 days at 90% MT.36 This treatment paradigm was shown to be more effective than standard protocols and was FDA-approved in 2022. Although this specific iTBS protocol exhibited encouraging results, the need for fMRI for adequate delivery might limit its use.

Continue to: Transcranial direct current stimulation

Transcranial direct current stimulation

Therapeutic noninvasive brain stimulation technology is plausible due to the relative lack of adverse effects and ease of administration. In transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), a low-intensity, constant electric current is delivered to stimulate the brain via electrodes attached to the scalp. tDCS modulates spontaneous neuronal network activity40,41 and induces polarization of resting membrane potential at the neuronal level,42 though the exact mechanism is yet to be proven. N-methyl-

tDCS has been suggested as a treatment for various psychiatric and medical conditions. However, the small sample sizes and experimental design of published studies have limited tDCS from being clinically recommended.30 No recommendation of Level A (definite efficacy) for its use was found for any indication. Level B recommendation (probable efficacy) was proposed for fibromyalgia, MDD episode without drug resistance, and addiction/craving. Level C recommendation (possible efficacy) is proposed for chronic lower limb neuropathic pain secondary to spinal cord lesion. tDCS was found to be probably ineffective as a treatment for tinnitus and drug-resistant MDD.30 Some research has suggested that tDCS targeting the DLPFC is associated with cognitive improvements in healthy individuals as well as those with schizophrenia.44 tDCS treatment remains experimental and investigational.

Deep brain stimulation

DBS is a neurosurgical procedure that uses electrical current to directly modulate specific areas of the CNS. In terms of accurate, site-specific anatomical targeting, there can be little doubt of the superiority of DBS. DBS involves the placement of leads into the brain parenchyma. Image guidance techniques are used for accurate placement. DBS is a mainstay for the symptomatic treatment of treatment-resistant movement disorders such as Parkinson disease, essential tremor, and some dystonic disorders. It also has been studied as a potential treatment for chronic pain, cluster headache, Huntington disease, and Tourette syndrome.

For treating depression, researched targets include the subgenual cingulate gyrus (SCG), ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens, inferior thalamic peduncle, medial forebrain bundle, and the red nucleus.45 In systematic reviews, improvement of depression is greatest when DBS targets the subgenual cingulate cortex and the medial forebrain bundle.46

The major limitation of DBS for treating depression is the invasive nature of the procedure. Deep TMS can achieve noninvasive stimulation of the SCG and may be associated with fewer risks, fewer adverse events, and less collateral damage. However, given the evolving concept of abnormal neurologic circuits in depression, as our understanding of circuitry in pathological psychiatric processes increases, DBS may be an attractive option for personalized targeting of symptoms in some patients.

DBS may also be beneficial for severe, treatment-resistant OCD. Electrode implantation in the region of the internal capsule/ventral striatum, including the nucleus accumbens, is used47; there is little difference in placement as a treatment for OCD vs for movement disorders.48

Continue to: A critical review of 23 trials...

A critical review of 23 trials and case reports of DBS as a treatment for OCD demonstrated a 47.7% mean reduction in score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) and a mean response percentage (minimum 35% Y-BOCS reduction) of 58.2%.49 Most patients regained a normal quality of life after DBS.49 A more rigorous review of 15 meta-analyses of DBS found that conclusions about its efficacy or comparative effectiveness cannot be drawn.50 Because of the nature of neurosurgery, DBS has many potential complications, including cognitive changes, headache, infection, seizures, stroke, and hardware failure.

Vagus nerve stimulation

VNS, in which an implanted device stimulates the left vagus nerve with electrical impulses, was FDA-approved for treating chronic TRD in 2005.51 It had been approved for treatment-resistant epilepsy in 1997. In patients with epilepsy, VNS was shown to improve mood independent of seizure control.52 VNS requires a battery-powered pacemaker device to be implanted under the skin over the anterior chest wall, and a wire tunneled to an electrode is wrapped around the left vagus nerve in the neck.53 The pacemaker is then programmed, monitored, and reprogrammed to optimize response.

VNS is believed to stimulate deep brain nuclei that may play a role in depression.54 The onset of improvement is slow (it may take many months) but in carefully selected patients VNS can provide significant control of TRD. In addition to rare surgery-related complications such as a trauma to the vagal nerve and surrounding tissues (vocal cord paralysis, implant site infection, left facial nerve paralysis and Horner syndrome), VNS may cause hoarseness, dyspnea, and cough related to the intensity of the current output.51 Hypomania and mania were also reported; no suicidal behavior has been associated with VNS.51

Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulationIn noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) or transcutaneous VNS, an external handheld device is applied to the neck overlying the course of the vagus nerve to deliver a sinusoidal alternating current.55 nVNS is currently FDA-approved for treating migraine headaches.55,56 It has demonstrated actions on neurophysiology57 and inflammation in patients with MDD.58 Exploratory research has found a small beneficial effect in patients with depression.59,60 A lack of adequate reproducibility prevents this treatment from being more widely recommended, although attempts to standardize the field are evolving.61

Cranial electrical stimulation

Cranial electrical stimulation (CES) is an older form of electric stimulation developed in the 1970s. In CES, mild electrical pulses are delivered to the ear lobes bilaterally in an episodic fashion (usually 20 to 60 minutes once or twice daily). While CES can be considered a form of neuromodulation, it is not strictly interventional. Patients self-administer CES. The procedure has minimal effects on improving sleep, anxiety, and mood.62-66 Potential adverse effects include a tingling sensation in the ear lobes, lightheadedness, and fogginess. A review and meta-analysis of CES for treating addiction by Kirsch67 showed a wide range of symptoms responding positively to CES treatment, although this study was not peer-reviewed. Because of the low quality of nearly all research that evaluated CES, this form of electric stimulation cannot be viewed as an accepted treatment for any of its listed indications.

Continue to: Other neuromodulation techniques

Other

In addition to the forms of neuromodulation we have already described, there are many other techniques. Several are promising but not yet ready for clinical use. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the neuromodulation techniques described in this article as well as several that are under development.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a Chinese form of medical treatment that began >3,000 years ago; there are written descriptions of it from >2,000 years ago.68 It is based on the belief that there are channels within the body through which the Qi (vital energy or life force) flow, and that inserting fine needles into these channels via the skin can rebalance Qi.68 Modern mechanistic hypotheses invoke involvement of inflammatory or pain pathways.69 Acupuncture frequently uses electric stimulation (electro-acupuncture) to increase the potency of the procedure. Alternatively, in a related procedure (acupressure), pressure can replace the needle. Accreditation in acupuncture generally requires a master’s degree in traditional Chinese medicine but does not require any specific medical training. Acupuncture training courses for physicians are widely available.

All forms of acupuncture are experimental for a wide variety of mental and medical conditions. A meta-analysis found that most research of the utility of acupuncture for depression suffered from various forms of potential bias and was considered low quality.70 Nonetheless, active acupuncture was shown to be minimally superior to placebo acupuncture.70 A meta-analysis of acupuncture for preoperative anxiety71,72 and poststroke insomnia73 reported a similar low study quality. A study of 72 patients with primary insomnia revealed that acupuncture was more effective than sham acupuncture for most sleep measures.74

Psychiatry is increasingly integrating medical tools in addition to psychological tools. Pharmacology remains a cornerstone of biological psychiatry and this will not soon change. However, nonpharmacologic psychiatric treatments such as therapeutic neuromodulation are rapidly emerging. These and novel methods of medication administration may present a challenge to psychiatrists who do not have access to medical personnel or may have forgotten general medical skills.

Our 2-part article has highlighted several interventional psychiatry tools—old and new—that may interest clinicians and benefit patients. As a rule, such treatments are reserved for the most treatment-resistant, challenging psychiatric patients, those with hard-to-treat chronic conditions, and patients who are not helped by more commonly used treatments. An additional complication is that such treatments are frequently not appropriately researched, vetted, or FDA-approved, and therefore are higher risk. Appropriate clinical judgment is always necessary, and potential benefits must be thoroughly weighed against possible adverse effects.

Bottom Line

Several forms of neuromodulation, including electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation, may be beneficial for patients with certain treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Related Resources

- Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

- Sharma MS, Ang-Rabanes M, Selek S, et al. Neuromodulatory options for treatment-resistant depression. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):26-28,33-37.

1. Maloney TR, Dilkes-Hall IE, Vlok M, et al. Surgical amputation of a limb 31,000 years ago in Borneo. Nature. 2022;609(7927):547-551. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05160-8