User login

Translating the 2020 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for the Management of Psoriasis With Systemic Nonbiologics to Clinical Practice

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing skin condition characterized by keratinocyte hyperproliferation and a chronic inflammatory cascade. Therefore, controlling inflammatory responses with systemic medications is beneficial in managing psoriatic lesions and their accompanying symptoms, especially in disease inadequately controlled by topicals. Ease of drug administration and treatment availability are benefits that systemic nonbiologic therapies may have over biologic therapies.

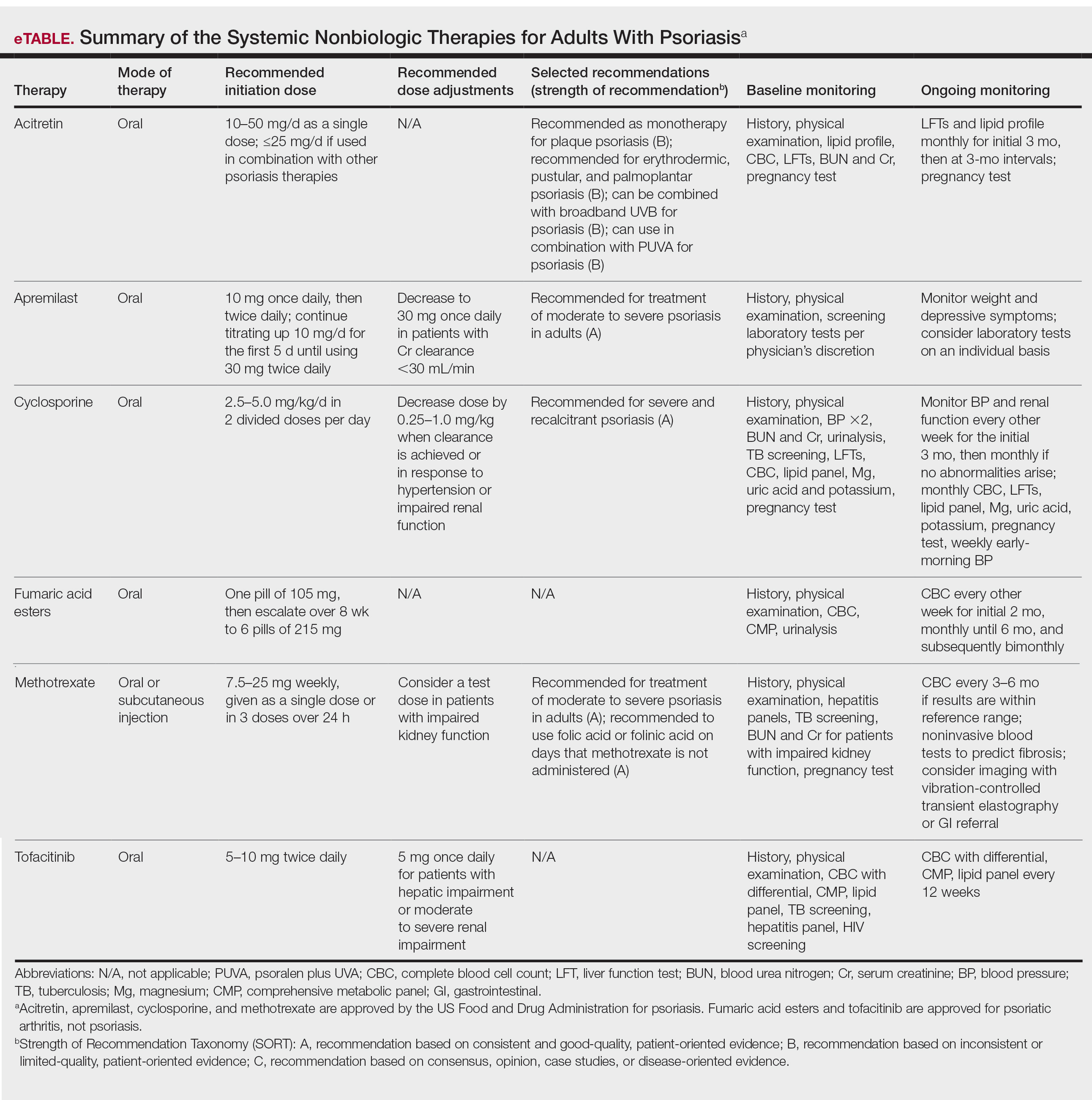

In 2020, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with systemic nonbiologic therapies.1 Dosing, efficacy, toxicity, drug-related interactions, and contraindications are addressed alongside evidence-based treatment recommendations. This review addresses current recommendations for systemic nonbiologics in psoriasis with a focus on the treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, and methotrexate (eTable). Fumaric acid esters and tofacitinib are FDA approved for psoriatic arthritis but not for plaque psoriasis. Additional long-term safety analyses of tofacitinib for plaque psoriasis were requested by the FDA. Dimethyl fumarate is approved by the European Medicines Agency for treatment of psoriasis and is among the first-line systemic treatments used in Germany.2

Selecting a Systemic Nonbiologic Agent

Methotrexate and apremilast have a strength level A recommendation for treating moderate to severe psoriasis in adults. However, methotrexate is less effective than biologic agents, including adalimumab and infliximab, for cutaneous psoriasis. Methotrexate is believed to improve psoriasis because of its direct immunosuppressive effect and inhibition of lymphoid cell proliferation. It typically is administered orally but can be administered subcutaneously for decreased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects. Compliance with close laboratory monitoring and lifestyle modifications, such as contraceptive use (because of teratogenicity) and alcohol cessation (because of the risk of liver damage) are essential in patients using methotrexate.

Apremilast, the most recently FDA-approved oral systemic medication for psoriasis, inhibits phosphodiesterase 4, subsequently decreasing inflammatory responses involving helper T cells TH1 and TH17 as well as type 1 interferon pathways. Apremilast is particularly effective in treating psoriasis with scalp and palmoplantar involvement.3 Additionally, it has an encouraging safety profile and is favorable in patients with multiple comorbidities.

Among the 4 oral agents, cyclosporine has the quickest onset of effect and has a strength level A recommendation for treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis. Because of its high-risk profile, it is recommended for short periods of time, acute flares, or during transitions to safer long-term treatment. Patients with multiple comorbidities should avoid cyclosporine as a treatment option.

Acitretin, an FDA-approved oral retinoid, is an optimal treatment option for immunosuppressed patients or patients with HIV on antiretroviral therapy because it is not immunosuppressive.4 Unlike cyclosporine, acitretin is less helpful for acute flares because it takes 3 to 6 months to reach peak therapeutic response for treating plaque psoriasis. Similar to cyclosporine, acitretin can be recommended for severe psoriatic variants of erythrodermic, generalized pustular, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Acitretin has been reported to be more effective and have a more rapid onset of action in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis than in plaque psoriasis.5

Patient Comorbidities

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a common comorbidity that affects treatment choice. Patients with coexisting PsA could be treated with apremilast, as it is approved for both psoriasis and PsA. In a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial, American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at weeks 16 and 52 was achieved by significantly more patients on apremilast at 20 mg twice daily (BID)(P=.0166) or 30 mg BID (P=.0001) than placebo.6 Although not FDA approved for PsA, methotrexate has been shown to improve concomitant PsA of the peripheral joints in patients with psoriasis. Furthermore, a trial of methotrexate has shown considerable improvements in PsA symptoms in patients with psoriasis—a 62.7% decrease in proportion of patients with dactylitis, 25.7% decrease in enthesitis, and improvements in ACR outcomes (ACR20 in 40.8%, ACR50 in 18.8%, and ACR70 in 8.6%, with 22.4% achieving minimal disease activity).7

Prior to starting a systemic medication for psoriasis, it is necessary to discuss effects on pregnancy and fertility. Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate and acitretin use because of the drugs’ teratogenicity. Fetal death and fetal abnormalities have been reported with methotrexate use in pregnant women.8 Bone, central nervous system, auditory, ocular, and cardiovascular fetal abnormalities have been reported with maternal acitretin use.9 Breastfeeding also is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate use, as methotrexate passes into breastmilk in small quantities. Patients taking acitretin also are strongly discouraged from nursing because of the long half-life (168 days) of etretinate, a reverse metabolism product of acitretin that is increased in the presence of alcohol. Women should wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate for complete drug clearance before conceiving compared to 3 years in women who have discontinued acitretin.8,10 Men also are recommended to wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate before attempting to conceive, as its effect on male spermatogenesis and teratogenicity is unclear. Acitretin has no documented teratogenic effect in men. For women planning to become pregnant, apremilast and cyclosporine can be continued throughout pregnancy on an individual basis. The benefit of apremilast should be weighed against its potential risk to the fetus. There is no evidence of teratogenicity of apremilast at doses of 20 mg/kg daily.11 Current research regarding cyclosporine use in pregnancy only exists in transplant patients and has revealed higher rates of prematurity and lower birth weight without teratogenic effects.10,12 The risks and benefits of continuing cyclosporine while nursing should be evaluated, as cyclosporine (and ethanol-methanol components used in some formulations) is detectable in breast milk.

Drug Contraindications

Hypersensitivity to a specific systemic nonbiologic medication is a contraindication to its use and is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate. Other absolute contraindications to methotrexate are pregnancy and nursing, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease, chronic liver disease, immunodeficiency, and cytopenia. Contraindications to acitretin include pregnancy, severely impaired liver and kidney function, and chronic abnormally elevated lipid levels. There are no additional contraindications for apremilast, but patients must be informed of the risk for depression before initiating therapy. Cyclosporine is contraindicated in patients with prior psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) treatment or radiation therapy, abnormal renal function, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled and active infections, and a history of systemic malignancy. Live vaccines should be avoided in patients on cyclosporine, and caution is advised when cyclosporine is prescribed for patients with poorly controlled diabetes.

Pretreatment Screening

Because of drug interactions, a detailed medication history is essential prior to starting any systemic medication for psoriasis. Apremilast and cyclosporine are metabolized by cytochrome P450 and therefore are more susceptible to drug-related interactions. Cyclosporine use can affect levels of other medications that are metabolized by cytochrome P450, such as statins, calcium channel blockers, and warfarin. Similarly, acitretin’s metabolism is affected by drugs that interfere with cytochrome P450. Additionally, screening laboratory tests are needed before initiating systemic nonbiologic agents for psoriasis, with the exception of apremilast.

Prior to initiating methotrexate treatment, patients may require tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B, and hepatitis C screening tests, depending on their risk factors. A baseline liver fibrosis assessment is recommended because of the potential of hepatotoxicity in patients receiving methotrexate. Noninvasive serology tests utilized to evaluate the presence of pre-existing liver disease include Fibrosis-4, FibroMeter, FibroSure, and Hepascore. Patients with impaired renal function have an increased predisposition to methotrexate-induced hematologic toxicity. Thus, it is necessary to administer a test dose of methotrexate in these patients followed by a complete blood cell count (CBC) 5 to 7 days later. An unremarkable CBC after the test dose suggests the absence of myelosuppression, and methotrexate dosage can be increased weekly. Patients on methotrexate also must receive folate supplementation to reduce the risk for adverse effects during treatment.

Patients considering cyclosporine must undergo screening for family and personal history of renal disease. Prior to initiating treatment, patients require 2 blood pressure measurements, hepatitis screening, TB screening, urinalysis, serum creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid profile, bilirubin, and liver function tests (LFTs). A pregnancy test also is warranted for women of childbearing potential (WOCP).

Patients receiving acitretin should receive screening laboratory tests consisting of fasting cholesterol and triglycerides, CBC, renal function tests, LFTs, and a pregnancy test, if applicable.

After baseline evaluations, the selected oral systemic can be initiated using specific dosing regimens to ensure optimal drug efficacy and reduce incidence of adverse effects (eTable).

Monitoring During Active Treatment

Physicians need to counsel patients on potential adverse effects of their medications. Because of its relatively safe profile among the systemic nonbiologic agents, apremilast requires the least monitoring during treatment. There is no required routine laboratory monitoring for patients using apremilast, though testing may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. However, weight should be regularly measured in patients on apremilast. In a phase 3 clinical trial of patients with psoriasis, 12% of patients on apremilast experienced a 5% to 10% weight loss compared to 5% of patients on placebo.11,13 Thus, it is recommended that physicians consider discontinuing apremilast in patients with a weight loss of more than 5% from baseline, especially if it may lead to other unfavorable health effects. Because depression is reported among 1% of patients on apremilast, close monitoring for new or worsening symptoms of depression should be performed during treatment.11,13 To avoid common GI side effects, apremilast is initiated at 10 mg/d and is increased by 10 mg/d over the first 5 days to a final dose of 30 mg BID. Elderly patients in particular should be cautioned about the risk of dehydration associated with GI side effects. Patients with severe renal impairment (Cr clearance, <30 mL/min) should use apremilast at a dosage of 30 mg once daily.

For patients on methotrexate, laboratory monitoring is essential after each dose increase. It also is important for physicians to obtain regular blood work to assess for hematologic abnormalities and hepatoxicity. Patients with risk factors such as renal insufficiency, increased age, hypoalbuminemia, alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver disease, and methotrexate dosing errors, as well as those prone to drug-related interactions, must be monitored closely for pancytopenia.14,15 The protocol for screening for methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity during treatment depends on patient risk factors. Risk factors for hepatoxicity include history of or current alcohol abuse, abnormal LFTs, personal or family history of liver disease, diabetes, obesity, use of other hepatotoxic drugs, and hyperlipidemia.16 In patients without blood work abnormalities, CBC and LFTs can be performed every 3 to 6 months. Patients with abnormally elevated LFTs require repeat blood work every 2 to 4 weeks. Persistent elevations in LFTs require further evaluation by a GI specialist. After a cumulative dose of 3.5 to 4 g, patients should receive a GI referral and further studies (such as vibration-controlled transient elastography or liver biopsy) to assess for liver fibrosis. Patients with signs of stage 3 liver fibrosis are recommended to discontinue methotrexate and switch to another medication for psoriasis. For patients with impaired renal function, periodic BUN and Cr monitoring are needed. Common adverse effects of methotrexate include diarrhea, nausea, and anorexia, which can be mitigated by taking methotrexate with food or lowering the dosage.8 Patients on methotrexate should be monitored for rare but potential risks of infection and reactivation of latent TB, hepatitis, and lymphoma. To reduce the incidence of methotrexate toxicity from drug interactions, a review of current medications at each follow-up visit is recommended.

Nephrotoxicity and hypertension are the most common adverse effects of cyclosporine. It is important to monitor BUN and Cr biweekly for the initial 3 months, then at monthly intervals if there are no persistent abnormalities. Patients also must receive monthly CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid panel, serum bilirubin, and LFTs to monitor for adverse effects.17 Physicians should obtain regular pregnancy tests in WOCP. Weekly monitoring of early-morning blood pressure is recommended for patients on cyclosporine to detect early cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity. Hypertension on 2 separate occasions warrants a reduction in cyclosporine dosage or an addition of a calcium channel blocker for blood pressure control. Dose reduction also should be performed in patients with an increase in Cr above baseline greater than 25%.17 If Cr level is persistently elevated or if blood pressure does not normalize to lower than 140/90 after dose reduction, cyclosporine should be immediately discontinued. Patients on cyclosporine for more than a year warrant an annual estimation of glomerular filtration rate because of irreversible kidney damage associated with long-term use. A systematic review of patients treated with cyclosporine for more than 2 years found that at least 50% of patients experienced a 30% increase in Cr above baseline.18

Patients taking acitretin should be monitored for hyperlipidemia, the most common laboratory abnormality seen in 25% to 50% of patients.19 Fasting lipid panel and LFTs should be performed monthly for the initial 3 months on acitretin, then at 3-month intervals. Lifestyle changes should be encouraged to reduce hyperlipidemia, and fibrates may be given to treat elevated triglyceride levels, the most common type of hyperlipidemia seen with acitretin. Acitretin-induced toxic hepatitis is a rare occurrence that warrants immediate discontinuation of the medication.20 Monthly pregnancy tests must be performed in WOCP.

Combination Therapy

For apremilast, there is anecdotal evidence supporting its use in conjunction with phototherapy or biologics in some cases, but no high-quality data.21 On the other hand, using combination therapy with other systemic therapies can reduce adverse effects and decrease the amount of medication needed to achieve psoriasis clearance. Methotrexate used with etanercept, for example, has been more effective than methotrexate monotherapy in treating psoriasis, which has been attributed to a methotrexate-mediated reduction in the production of antidrug antibodies.22,23

Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin have synergistic effects when used with phototherapy. Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy combined with methotrexate is more effective in clearing psoriasis than methotrexate or NB-UVB phototherapy alone. Similarly, acitretin and PUVA combination therapy is more effective than acitretin or PUVA phototherapy alone. Combination regimens of acitretin and broadband UVB phototherapy, acitretin and NB-UVB phototherapy, and acitretin and PUVA phototherapy also have been more effective than individual modalities alone. Combination therapy reduces the cumulative doses of both therapies and reduces the frequency and duration of phototherapy needed for psoriatic clearance.24 In acitretin combination therapy with UVB phototherapy, the recommended regimen is 2 weeks of acitretin monotherapy followed by UVB phototherapy. For patients with an inadequate response to UVB phototherapy, the UVB dose can be reduced by 30% to 50%, and acitretin 25 mg/d can be added to phototherapy treatment. Acitretin-UVB combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of UVB-induced erythema seen in UVB monotherapy. Similarly, the risk of squamous cell carcinoma is reduced in acitretin-PUVA combination therapy compared to PUVA monotherapy.25

The timing of phototherapy in combination with systemic nonbiologic agents is critical. Phototherapy used simultaneously with cyclosporine is contraindicated owing to increased risk of photocarcinogenesis, whereas phototherapy used in sequence with cyclosporine is well tolerated and effective. Furthermore, cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d for 4 weeks followed by a rapid cyclosporine taper and initiation of NB-UVB phototherapy demonstrated resolution of psoriasis with fewer NB-UVB treatments and less UVB exposure than NB-UVB therapy alone.26

Final Thoughts

The FDA-approved systemic nonbiologic agents are accessible and effective treatment options for adults with widespread or inadequately controlled psoriasis. Selecting the ideal therapy requires careful consideration of medication toxicity, contraindications, monitoring requirements, and patient comorbidities. The AAD-NPF guidelines guide dermatologists in prescribing systemic nonbiologic treatments in adults with psoriasis. Utilizing these recommendations in combination with clinician judgment will help patients achieve safe and optimal psoriasis clearance.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486.

- Mrowietz U, Barker J, Boehncke WH, et al. Clinical use of dimethyl fumarate in moderate-to-severe plaque-type psoriasis: a European expert consensus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(suppl 3):3-14.

- Van Voorhees AS, Gold LS, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis of the scalp: results of a phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:96-103.

- Buccheri L, Katchen BR, Karter AJ, et al. Acitretin therapy is effective for psoriasis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:711-715.

- Ormerod AD, Campalani E, Goodfield MJD. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines on the efficacy and use of acitretin in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:952-963.

- Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Longterm (52-week) results of a phase III randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:479-488.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Antares Pharma, Inc. Otrexup PFS (methotrexate) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised June 2019. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/204824s009lbl.pdf

- David M, Hodak E, Lowe NJ. Adverse effects of retinoids. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1988;3:273-288.

- Stiefel Laboratories, Inc. Soriatane (acitretin) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised September 2017. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/019821s028lbl.pdf

- Celgene Corporation. Otezla (apremilast) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised March 2014. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205437s000lbl.pdf

- Ghanem ME, El-Baghdadi LA, Badawy AM, et al. Pregnancy outcome after renal allograft transplantation: 15 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121:178-181.

- Zerilli T, Ocheretyaner E. Apremilast (Otezla): A new oral treatment for adults with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. P T. 2015;40:495-500.

- Kivity S, Zafrir Y, Loebstein R, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for low dose methotrexate toxicity: a cohort of 28 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1109-1113.

- Boffa MJ, Chalmers RJ. Methotrexate for psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:399-408.

- Rosenberg P, Urwitz H, Johannesson A, et al. Psoriasis patients with diabetes type 2 are at high risk of developing liver fibrosis during methotrexate treatment. J Hepatol. 2007;46:1111-1118.

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Sandimmune (cyclosporine) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published 2015. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/050573s041,050574s051,050625s055lbl.pdf

- Maza A, Montaudie H, Sbidian E, et al. Oral cyclosporin in psoriasis: a systematic review on treatment modalities, risk of kidney toxicity and evidence for use in non-plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 2):19-27.

- Yamauchi PS, Rizk D, Kormilli T, et al. Systemic retinoids. In: Weinstein GD, Gottlieb AB, eds. Therapy of Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. Marcel Dekker; 2003:137-150.

- van Ditzhuijsen TJ, van Haelst UJ, van Dooren-Greebe RJ, et al. Severe hepatotoxic reaction with progression to cirrhosis after use of a novel retinoid (acitretin). J Hepatol. 1990;11:185-188.

- AbuHilal M, Walsh S, Shear N. Use of apremilast in combination with other therapies for treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:313-316.

- Gottlieb AB, Langley RG, Strober BE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the addition of methotrexate to etanercept in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:649-657.

- Cronstein BN. Methotrexate BAFFles anti-drug antibodies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:505-506.

- Lebwohl M, Drake L, Menter A, et al. Consensus conference: acitretin in combination with UVB or PUVA in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:544-553.

- Nijsten TE, Stern RS. Oral retinoid use reduces cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma risk in patients with psoriasis treated with psoralen-UVA: a nested cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:644-650.

- Calzavara-Pinton P, Leone G, Venturini M, et al. A comparative non randomized study of narrow-band (NB) (312 +/- 2 nm) UVB phototherapy versus sequential therapy with oral administration of low-dose cyclosporin A and NB-UVB phototherapy in patients with severe psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:470-473.

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing skin condition characterized by keratinocyte hyperproliferation and a chronic inflammatory cascade. Therefore, controlling inflammatory responses with systemic medications is beneficial in managing psoriatic lesions and their accompanying symptoms, especially in disease inadequately controlled by topicals. Ease of drug administration and treatment availability are benefits that systemic nonbiologic therapies may have over biologic therapies.

In 2020, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with systemic nonbiologic therapies.1 Dosing, efficacy, toxicity, drug-related interactions, and contraindications are addressed alongside evidence-based treatment recommendations. This review addresses current recommendations for systemic nonbiologics in psoriasis with a focus on the treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, and methotrexate (eTable). Fumaric acid esters and tofacitinib are FDA approved for psoriatic arthritis but not for plaque psoriasis. Additional long-term safety analyses of tofacitinib for plaque psoriasis were requested by the FDA. Dimethyl fumarate is approved by the European Medicines Agency for treatment of psoriasis and is among the first-line systemic treatments used in Germany.2

Selecting a Systemic Nonbiologic Agent

Methotrexate and apremilast have a strength level A recommendation for treating moderate to severe psoriasis in adults. However, methotrexate is less effective than biologic agents, including adalimumab and infliximab, for cutaneous psoriasis. Methotrexate is believed to improve psoriasis because of its direct immunosuppressive effect and inhibition of lymphoid cell proliferation. It typically is administered orally but can be administered subcutaneously for decreased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects. Compliance with close laboratory monitoring and lifestyle modifications, such as contraceptive use (because of teratogenicity) and alcohol cessation (because of the risk of liver damage) are essential in patients using methotrexate.

Apremilast, the most recently FDA-approved oral systemic medication for psoriasis, inhibits phosphodiesterase 4, subsequently decreasing inflammatory responses involving helper T cells TH1 and TH17 as well as type 1 interferon pathways. Apremilast is particularly effective in treating psoriasis with scalp and palmoplantar involvement.3 Additionally, it has an encouraging safety profile and is favorable in patients with multiple comorbidities.

Among the 4 oral agents, cyclosporine has the quickest onset of effect and has a strength level A recommendation for treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis. Because of its high-risk profile, it is recommended for short periods of time, acute flares, or during transitions to safer long-term treatment. Patients with multiple comorbidities should avoid cyclosporine as a treatment option.

Acitretin, an FDA-approved oral retinoid, is an optimal treatment option for immunosuppressed patients or patients with HIV on antiretroviral therapy because it is not immunosuppressive.4 Unlike cyclosporine, acitretin is less helpful for acute flares because it takes 3 to 6 months to reach peak therapeutic response for treating plaque psoriasis. Similar to cyclosporine, acitretin can be recommended for severe psoriatic variants of erythrodermic, generalized pustular, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Acitretin has been reported to be more effective and have a more rapid onset of action in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis than in plaque psoriasis.5

Patient Comorbidities

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a common comorbidity that affects treatment choice. Patients with coexisting PsA could be treated with apremilast, as it is approved for both psoriasis and PsA. In a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial, American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at weeks 16 and 52 was achieved by significantly more patients on apremilast at 20 mg twice daily (BID)(P=.0166) or 30 mg BID (P=.0001) than placebo.6 Although not FDA approved for PsA, methotrexate has been shown to improve concomitant PsA of the peripheral joints in patients with psoriasis. Furthermore, a trial of methotrexate has shown considerable improvements in PsA symptoms in patients with psoriasis—a 62.7% decrease in proportion of patients with dactylitis, 25.7% decrease in enthesitis, and improvements in ACR outcomes (ACR20 in 40.8%, ACR50 in 18.8%, and ACR70 in 8.6%, with 22.4% achieving minimal disease activity).7

Prior to starting a systemic medication for psoriasis, it is necessary to discuss effects on pregnancy and fertility. Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate and acitretin use because of the drugs’ teratogenicity. Fetal death and fetal abnormalities have been reported with methotrexate use in pregnant women.8 Bone, central nervous system, auditory, ocular, and cardiovascular fetal abnormalities have been reported with maternal acitretin use.9 Breastfeeding also is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate use, as methotrexate passes into breastmilk in small quantities. Patients taking acitretin also are strongly discouraged from nursing because of the long half-life (168 days) of etretinate, a reverse metabolism product of acitretin that is increased in the presence of alcohol. Women should wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate for complete drug clearance before conceiving compared to 3 years in women who have discontinued acitretin.8,10 Men also are recommended to wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate before attempting to conceive, as its effect on male spermatogenesis and teratogenicity is unclear. Acitretin has no documented teratogenic effect in men. For women planning to become pregnant, apremilast and cyclosporine can be continued throughout pregnancy on an individual basis. The benefit of apremilast should be weighed against its potential risk to the fetus. There is no evidence of teratogenicity of apremilast at doses of 20 mg/kg daily.11 Current research regarding cyclosporine use in pregnancy only exists in transplant patients and has revealed higher rates of prematurity and lower birth weight without teratogenic effects.10,12 The risks and benefits of continuing cyclosporine while nursing should be evaluated, as cyclosporine (and ethanol-methanol components used in some formulations) is detectable in breast milk.

Drug Contraindications

Hypersensitivity to a specific systemic nonbiologic medication is a contraindication to its use and is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate. Other absolute contraindications to methotrexate are pregnancy and nursing, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease, chronic liver disease, immunodeficiency, and cytopenia. Contraindications to acitretin include pregnancy, severely impaired liver and kidney function, and chronic abnormally elevated lipid levels. There are no additional contraindications for apremilast, but patients must be informed of the risk for depression before initiating therapy. Cyclosporine is contraindicated in patients with prior psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) treatment or radiation therapy, abnormal renal function, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled and active infections, and a history of systemic malignancy. Live vaccines should be avoided in patients on cyclosporine, and caution is advised when cyclosporine is prescribed for patients with poorly controlled diabetes.

Pretreatment Screening

Because of drug interactions, a detailed medication history is essential prior to starting any systemic medication for psoriasis. Apremilast and cyclosporine are metabolized by cytochrome P450 and therefore are more susceptible to drug-related interactions. Cyclosporine use can affect levels of other medications that are metabolized by cytochrome P450, such as statins, calcium channel blockers, and warfarin. Similarly, acitretin’s metabolism is affected by drugs that interfere with cytochrome P450. Additionally, screening laboratory tests are needed before initiating systemic nonbiologic agents for psoriasis, with the exception of apremilast.

Prior to initiating methotrexate treatment, patients may require tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B, and hepatitis C screening tests, depending on their risk factors. A baseline liver fibrosis assessment is recommended because of the potential of hepatotoxicity in patients receiving methotrexate. Noninvasive serology tests utilized to evaluate the presence of pre-existing liver disease include Fibrosis-4, FibroMeter, FibroSure, and Hepascore. Patients with impaired renal function have an increased predisposition to methotrexate-induced hematologic toxicity. Thus, it is necessary to administer a test dose of methotrexate in these patients followed by a complete blood cell count (CBC) 5 to 7 days later. An unremarkable CBC after the test dose suggests the absence of myelosuppression, and methotrexate dosage can be increased weekly. Patients on methotrexate also must receive folate supplementation to reduce the risk for adverse effects during treatment.

Patients considering cyclosporine must undergo screening for family and personal history of renal disease. Prior to initiating treatment, patients require 2 blood pressure measurements, hepatitis screening, TB screening, urinalysis, serum creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid profile, bilirubin, and liver function tests (LFTs). A pregnancy test also is warranted for women of childbearing potential (WOCP).

Patients receiving acitretin should receive screening laboratory tests consisting of fasting cholesterol and triglycerides, CBC, renal function tests, LFTs, and a pregnancy test, if applicable.

After baseline evaluations, the selected oral systemic can be initiated using specific dosing regimens to ensure optimal drug efficacy and reduce incidence of adverse effects (eTable).

Monitoring During Active Treatment

Physicians need to counsel patients on potential adverse effects of their medications. Because of its relatively safe profile among the systemic nonbiologic agents, apremilast requires the least monitoring during treatment. There is no required routine laboratory monitoring for patients using apremilast, though testing may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. However, weight should be regularly measured in patients on apremilast. In a phase 3 clinical trial of patients with psoriasis, 12% of patients on apremilast experienced a 5% to 10% weight loss compared to 5% of patients on placebo.11,13 Thus, it is recommended that physicians consider discontinuing apremilast in patients with a weight loss of more than 5% from baseline, especially if it may lead to other unfavorable health effects. Because depression is reported among 1% of patients on apremilast, close monitoring for new or worsening symptoms of depression should be performed during treatment.11,13 To avoid common GI side effects, apremilast is initiated at 10 mg/d and is increased by 10 mg/d over the first 5 days to a final dose of 30 mg BID. Elderly patients in particular should be cautioned about the risk of dehydration associated with GI side effects. Patients with severe renal impairment (Cr clearance, <30 mL/min) should use apremilast at a dosage of 30 mg once daily.

For patients on methotrexate, laboratory monitoring is essential after each dose increase. It also is important for physicians to obtain regular blood work to assess for hematologic abnormalities and hepatoxicity. Patients with risk factors such as renal insufficiency, increased age, hypoalbuminemia, alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver disease, and methotrexate dosing errors, as well as those prone to drug-related interactions, must be monitored closely for pancytopenia.14,15 The protocol for screening for methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity during treatment depends on patient risk factors. Risk factors for hepatoxicity include history of or current alcohol abuse, abnormal LFTs, personal or family history of liver disease, diabetes, obesity, use of other hepatotoxic drugs, and hyperlipidemia.16 In patients without blood work abnormalities, CBC and LFTs can be performed every 3 to 6 months. Patients with abnormally elevated LFTs require repeat blood work every 2 to 4 weeks. Persistent elevations in LFTs require further evaluation by a GI specialist. After a cumulative dose of 3.5 to 4 g, patients should receive a GI referral and further studies (such as vibration-controlled transient elastography or liver biopsy) to assess for liver fibrosis. Patients with signs of stage 3 liver fibrosis are recommended to discontinue methotrexate and switch to another medication for psoriasis. For patients with impaired renal function, periodic BUN and Cr monitoring are needed. Common adverse effects of methotrexate include diarrhea, nausea, and anorexia, which can be mitigated by taking methotrexate with food or lowering the dosage.8 Patients on methotrexate should be monitored for rare but potential risks of infection and reactivation of latent TB, hepatitis, and lymphoma. To reduce the incidence of methotrexate toxicity from drug interactions, a review of current medications at each follow-up visit is recommended.

Nephrotoxicity and hypertension are the most common adverse effects of cyclosporine. It is important to monitor BUN and Cr biweekly for the initial 3 months, then at monthly intervals if there are no persistent abnormalities. Patients also must receive monthly CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid panel, serum bilirubin, and LFTs to monitor for adverse effects.17 Physicians should obtain regular pregnancy tests in WOCP. Weekly monitoring of early-morning blood pressure is recommended for patients on cyclosporine to detect early cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity. Hypertension on 2 separate occasions warrants a reduction in cyclosporine dosage or an addition of a calcium channel blocker for blood pressure control. Dose reduction also should be performed in patients with an increase in Cr above baseline greater than 25%.17 If Cr level is persistently elevated or if blood pressure does not normalize to lower than 140/90 after dose reduction, cyclosporine should be immediately discontinued. Patients on cyclosporine for more than a year warrant an annual estimation of glomerular filtration rate because of irreversible kidney damage associated with long-term use. A systematic review of patients treated with cyclosporine for more than 2 years found that at least 50% of patients experienced a 30% increase in Cr above baseline.18

Patients taking acitretin should be monitored for hyperlipidemia, the most common laboratory abnormality seen in 25% to 50% of patients.19 Fasting lipid panel and LFTs should be performed monthly for the initial 3 months on acitretin, then at 3-month intervals. Lifestyle changes should be encouraged to reduce hyperlipidemia, and fibrates may be given to treat elevated triglyceride levels, the most common type of hyperlipidemia seen with acitretin. Acitretin-induced toxic hepatitis is a rare occurrence that warrants immediate discontinuation of the medication.20 Monthly pregnancy tests must be performed in WOCP.

Combination Therapy

For apremilast, there is anecdotal evidence supporting its use in conjunction with phototherapy or biologics in some cases, but no high-quality data.21 On the other hand, using combination therapy with other systemic therapies can reduce adverse effects and decrease the amount of medication needed to achieve psoriasis clearance. Methotrexate used with etanercept, for example, has been more effective than methotrexate monotherapy in treating psoriasis, which has been attributed to a methotrexate-mediated reduction in the production of antidrug antibodies.22,23

Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin have synergistic effects when used with phototherapy. Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy combined with methotrexate is more effective in clearing psoriasis than methotrexate or NB-UVB phototherapy alone. Similarly, acitretin and PUVA combination therapy is more effective than acitretin or PUVA phototherapy alone. Combination regimens of acitretin and broadband UVB phototherapy, acitretin and NB-UVB phototherapy, and acitretin and PUVA phototherapy also have been more effective than individual modalities alone. Combination therapy reduces the cumulative doses of both therapies and reduces the frequency and duration of phototherapy needed for psoriatic clearance.24 In acitretin combination therapy with UVB phototherapy, the recommended regimen is 2 weeks of acitretin monotherapy followed by UVB phototherapy. For patients with an inadequate response to UVB phototherapy, the UVB dose can be reduced by 30% to 50%, and acitretin 25 mg/d can be added to phototherapy treatment. Acitretin-UVB combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of UVB-induced erythema seen in UVB monotherapy. Similarly, the risk of squamous cell carcinoma is reduced in acitretin-PUVA combination therapy compared to PUVA monotherapy.25

The timing of phototherapy in combination with systemic nonbiologic agents is critical. Phototherapy used simultaneously with cyclosporine is contraindicated owing to increased risk of photocarcinogenesis, whereas phototherapy used in sequence with cyclosporine is well tolerated and effective. Furthermore, cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d for 4 weeks followed by a rapid cyclosporine taper and initiation of NB-UVB phototherapy demonstrated resolution of psoriasis with fewer NB-UVB treatments and less UVB exposure than NB-UVB therapy alone.26

Final Thoughts

The FDA-approved systemic nonbiologic agents are accessible and effective treatment options for adults with widespread or inadequately controlled psoriasis. Selecting the ideal therapy requires careful consideration of medication toxicity, contraindications, monitoring requirements, and patient comorbidities. The AAD-NPF guidelines guide dermatologists in prescribing systemic nonbiologic treatments in adults with psoriasis. Utilizing these recommendations in combination with clinician judgment will help patients achieve safe and optimal psoriasis clearance.

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing skin condition characterized by keratinocyte hyperproliferation and a chronic inflammatory cascade. Therefore, controlling inflammatory responses with systemic medications is beneficial in managing psoriatic lesions and their accompanying symptoms, especially in disease inadequately controlled by topicals. Ease of drug administration and treatment availability are benefits that systemic nonbiologic therapies may have over biologic therapies.

In 2020, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with systemic nonbiologic therapies.1 Dosing, efficacy, toxicity, drug-related interactions, and contraindications are addressed alongside evidence-based treatment recommendations. This review addresses current recommendations for systemic nonbiologics in psoriasis with a focus on the treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, and methotrexate (eTable). Fumaric acid esters and tofacitinib are FDA approved for psoriatic arthritis but not for plaque psoriasis. Additional long-term safety analyses of tofacitinib for plaque psoriasis were requested by the FDA. Dimethyl fumarate is approved by the European Medicines Agency for treatment of psoriasis and is among the first-line systemic treatments used in Germany.2

Selecting a Systemic Nonbiologic Agent

Methotrexate and apremilast have a strength level A recommendation for treating moderate to severe psoriasis in adults. However, methotrexate is less effective than biologic agents, including adalimumab and infliximab, for cutaneous psoriasis. Methotrexate is believed to improve psoriasis because of its direct immunosuppressive effect and inhibition of lymphoid cell proliferation. It typically is administered orally but can be administered subcutaneously for decreased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects. Compliance with close laboratory monitoring and lifestyle modifications, such as contraceptive use (because of teratogenicity) and alcohol cessation (because of the risk of liver damage) are essential in patients using methotrexate.

Apremilast, the most recently FDA-approved oral systemic medication for psoriasis, inhibits phosphodiesterase 4, subsequently decreasing inflammatory responses involving helper T cells TH1 and TH17 as well as type 1 interferon pathways. Apremilast is particularly effective in treating psoriasis with scalp and palmoplantar involvement.3 Additionally, it has an encouraging safety profile and is favorable in patients with multiple comorbidities.

Among the 4 oral agents, cyclosporine has the quickest onset of effect and has a strength level A recommendation for treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis. Because of its high-risk profile, it is recommended for short periods of time, acute flares, or during transitions to safer long-term treatment. Patients with multiple comorbidities should avoid cyclosporine as a treatment option.

Acitretin, an FDA-approved oral retinoid, is an optimal treatment option for immunosuppressed patients or patients with HIV on antiretroviral therapy because it is not immunosuppressive.4 Unlike cyclosporine, acitretin is less helpful for acute flares because it takes 3 to 6 months to reach peak therapeutic response for treating plaque psoriasis. Similar to cyclosporine, acitretin can be recommended for severe psoriatic variants of erythrodermic, generalized pustular, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Acitretin has been reported to be more effective and have a more rapid onset of action in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis than in plaque psoriasis.5

Patient Comorbidities

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a common comorbidity that affects treatment choice. Patients with coexisting PsA could be treated with apremilast, as it is approved for both psoriasis and PsA. In a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial, American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at weeks 16 and 52 was achieved by significantly more patients on apremilast at 20 mg twice daily (BID)(P=.0166) or 30 mg BID (P=.0001) than placebo.6 Although not FDA approved for PsA, methotrexate has been shown to improve concomitant PsA of the peripheral joints in patients with psoriasis. Furthermore, a trial of methotrexate has shown considerable improvements in PsA symptoms in patients with psoriasis—a 62.7% decrease in proportion of patients with dactylitis, 25.7% decrease in enthesitis, and improvements in ACR outcomes (ACR20 in 40.8%, ACR50 in 18.8%, and ACR70 in 8.6%, with 22.4% achieving minimal disease activity).7

Prior to starting a systemic medication for psoriasis, it is necessary to discuss effects on pregnancy and fertility. Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate and acitretin use because of the drugs’ teratogenicity. Fetal death and fetal abnormalities have been reported with methotrexate use in pregnant women.8 Bone, central nervous system, auditory, ocular, and cardiovascular fetal abnormalities have been reported with maternal acitretin use.9 Breastfeeding also is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate use, as methotrexate passes into breastmilk in small quantities. Patients taking acitretin also are strongly discouraged from nursing because of the long half-life (168 days) of etretinate, a reverse metabolism product of acitretin that is increased in the presence of alcohol. Women should wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate for complete drug clearance before conceiving compared to 3 years in women who have discontinued acitretin.8,10 Men also are recommended to wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate before attempting to conceive, as its effect on male spermatogenesis and teratogenicity is unclear. Acitretin has no documented teratogenic effect in men. For women planning to become pregnant, apremilast and cyclosporine can be continued throughout pregnancy on an individual basis. The benefit of apremilast should be weighed against its potential risk to the fetus. There is no evidence of teratogenicity of apremilast at doses of 20 mg/kg daily.11 Current research regarding cyclosporine use in pregnancy only exists in transplant patients and has revealed higher rates of prematurity and lower birth weight without teratogenic effects.10,12 The risks and benefits of continuing cyclosporine while nursing should be evaluated, as cyclosporine (and ethanol-methanol components used in some formulations) is detectable in breast milk.

Drug Contraindications

Hypersensitivity to a specific systemic nonbiologic medication is a contraindication to its use and is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate. Other absolute contraindications to methotrexate are pregnancy and nursing, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease, chronic liver disease, immunodeficiency, and cytopenia. Contraindications to acitretin include pregnancy, severely impaired liver and kidney function, and chronic abnormally elevated lipid levels. There are no additional contraindications for apremilast, but patients must be informed of the risk for depression before initiating therapy. Cyclosporine is contraindicated in patients with prior psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) treatment or radiation therapy, abnormal renal function, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled and active infections, and a history of systemic malignancy. Live vaccines should be avoided in patients on cyclosporine, and caution is advised when cyclosporine is prescribed for patients with poorly controlled diabetes.

Pretreatment Screening

Because of drug interactions, a detailed medication history is essential prior to starting any systemic medication for psoriasis. Apremilast and cyclosporine are metabolized by cytochrome P450 and therefore are more susceptible to drug-related interactions. Cyclosporine use can affect levels of other medications that are metabolized by cytochrome P450, such as statins, calcium channel blockers, and warfarin. Similarly, acitretin’s metabolism is affected by drugs that interfere with cytochrome P450. Additionally, screening laboratory tests are needed before initiating systemic nonbiologic agents for psoriasis, with the exception of apremilast.

Prior to initiating methotrexate treatment, patients may require tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B, and hepatitis C screening tests, depending on their risk factors. A baseline liver fibrosis assessment is recommended because of the potential of hepatotoxicity in patients receiving methotrexate. Noninvasive serology tests utilized to evaluate the presence of pre-existing liver disease include Fibrosis-4, FibroMeter, FibroSure, and Hepascore. Patients with impaired renal function have an increased predisposition to methotrexate-induced hematologic toxicity. Thus, it is necessary to administer a test dose of methotrexate in these patients followed by a complete blood cell count (CBC) 5 to 7 days later. An unremarkable CBC after the test dose suggests the absence of myelosuppression, and methotrexate dosage can be increased weekly. Patients on methotrexate also must receive folate supplementation to reduce the risk for adverse effects during treatment.

Patients considering cyclosporine must undergo screening for family and personal history of renal disease. Prior to initiating treatment, patients require 2 blood pressure measurements, hepatitis screening, TB screening, urinalysis, serum creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid profile, bilirubin, and liver function tests (LFTs). A pregnancy test also is warranted for women of childbearing potential (WOCP).

Patients receiving acitretin should receive screening laboratory tests consisting of fasting cholesterol and triglycerides, CBC, renal function tests, LFTs, and a pregnancy test, if applicable.

After baseline evaluations, the selected oral systemic can be initiated using specific dosing regimens to ensure optimal drug efficacy and reduce incidence of adverse effects (eTable).

Monitoring During Active Treatment

Physicians need to counsel patients on potential adverse effects of their medications. Because of its relatively safe profile among the systemic nonbiologic agents, apremilast requires the least monitoring during treatment. There is no required routine laboratory monitoring for patients using apremilast, though testing may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. However, weight should be regularly measured in patients on apremilast. In a phase 3 clinical trial of patients with psoriasis, 12% of patients on apremilast experienced a 5% to 10% weight loss compared to 5% of patients on placebo.11,13 Thus, it is recommended that physicians consider discontinuing apremilast in patients with a weight loss of more than 5% from baseline, especially if it may lead to other unfavorable health effects. Because depression is reported among 1% of patients on apremilast, close monitoring for new or worsening symptoms of depression should be performed during treatment.11,13 To avoid common GI side effects, apremilast is initiated at 10 mg/d and is increased by 10 mg/d over the first 5 days to a final dose of 30 mg BID. Elderly patients in particular should be cautioned about the risk of dehydration associated with GI side effects. Patients with severe renal impairment (Cr clearance, <30 mL/min) should use apremilast at a dosage of 30 mg once daily.

For patients on methotrexate, laboratory monitoring is essential after each dose increase. It also is important for physicians to obtain regular blood work to assess for hematologic abnormalities and hepatoxicity. Patients with risk factors such as renal insufficiency, increased age, hypoalbuminemia, alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver disease, and methotrexate dosing errors, as well as those prone to drug-related interactions, must be monitored closely for pancytopenia.14,15 The protocol for screening for methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity during treatment depends on patient risk factors. Risk factors for hepatoxicity include history of or current alcohol abuse, abnormal LFTs, personal or family history of liver disease, diabetes, obesity, use of other hepatotoxic drugs, and hyperlipidemia.16 In patients without blood work abnormalities, CBC and LFTs can be performed every 3 to 6 months. Patients with abnormally elevated LFTs require repeat blood work every 2 to 4 weeks. Persistent elevations in LFTs require further evaluation by a GI specialist. After a cumulative dose of 3.5 to 4 g, patients should receive a GI referral and further studies (such as vibration-controlled transient elastography or liver biopsy) to assess for liver fibrosis. Patients with signs of stage 3 liver fibrosis are recommended to discontinue methotrexate and switch to another medication for psoriasis. For patients with impaired renal function, periodic BUN and Cr monitoring are needed. Common adverse effects of methotrexate include diarrhea, nausea, and anorexia, which can be mitigated by taking methotrexate with food or lowering the dosage.8 Patients on methotrexate should be monitored for rare but potential risks of infection and reactivation of latent TB, hepatitis, and lymphoma. To reduce the incidence of methotrexate toxicity from drug interactions, a review of current medications at each follow-up visit is recommended.

Nephrotoxicity and hypertension are the most common adverse effects of cyclosporine. It is important to monitor BUN and Cr biweekly for the initial 3 months, then at monthly intervals if there are no persistent abnormalities. Patients also must receive monthly CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid panel, serum bilirubin, and LFTs to monitor for adverse effects.17 Physicians should obtain regular pregnancy tests in WOCP. Weekly monitoring of early-morning blood pressure is recommended for patients on cyclosporine to detect early cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity. Hypertension on 2 separate occasions warrants a reduction in cyclosporine dosage or an addition of a calcium channel blocker for blood pressure control. Dose reduction also should be performed in patients with an increase in Cr above baseline greater than 25%.17 If Cr level is persistently elevated or if blood pressure does not normalize to lower than 140/90 after dose reduction, cyclosporine should be immediately discontinued. Patients on cyclosporine for more than a year warrant an annual estimation of glomerular filtration rate because of irreversible kidney damage associated with long-term use. A systematic review of patients treated with cyclosporine for more than 2 years found that at least 50% of patients experienced a 30% increase in Cr above baseline.18

Patients taking acitretin should be monitored for hyperlipidemia, the most common laboratory abnormality seen in 25% to 50% of patients.19 Fasting lipid panel and LFTs should be performed monthly for the initial 3 months on acitretin, then at 3-month intervals. Lifestyle changes should be encouraged to reduce hyperlipidemia, and fibrates may be given to treat elevated triglyceride levels, the most common type of hyperlipidemia seen with acitretin. Acitretin-induced toxic hepatitis is a rare occurrence that warrants immediate discontinuation of the medication.20 Monthly pregnancy tests must be performed in WOCP.

Combination Therapy

For apremilast, there is anecdotal evidence supporting its use in conjunction with phototherapy or biologics in some cases, but no high-quality data.21 On the other hand, using combination therapy with other systemic therapies can reduce adverse effects and decrease the amount of medication needed to achieve psoriasis clearance. Methotrexate used with etanercept, for example, has been more effective than methotrexate monotherapy in treating psoriasis, which has been attributed to a methotrexate-mediated reduction in the production of antidrug antibodies.22,23

Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin have synergistic effects when used with phototherapy. Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy combined with methotrexate is more effective in clearing psoriasis than methotrexate or NB-UVB phototherapy alone. Similarly, acitretin and PUVA combination therapy is more effective than acitretin or PUVA phototherapy alone. Combination regimens of acitretin and broadband UVB phototherapy, acitretin and NB-UVB phototherapy, and acitretin and PUVA phototherapy also have been more effective than individual modalities alone. Combination therapy reduces the cumulative doses of both therapies and reduces the frequency and duration of phototherapy needed for psoriatic clearance.24 In acitretin combination therapy with UVB phototherapy, the recommended regimen is 2 weeks of acitretin monotherapy followed by UVB phototherapy. For patients with an inadequate response to UVB phototherapy, the UVB dose can be reduced by 30% to 50%, and acitretin 25 mg/d can be added to phototherapy treatment. Acitretin-UVB combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of UVB-induced erythema seen in UVB monotherapy. Similarly, the risk of squamous cell carcinoma is reduced in acitretin-PUVA combination therapy compared to PUVA monotherapy.25

The timing of phototherapy in combination with systemic nonbiologic agents is critical. Phototherapy used simultaneously with cyclosporine is contraindicated owing to increased risk of photocarcinogenesis, whereas phototherapy used in sequence with cyclosporine is well tolerated and effective. Furthermore, cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d for 4 weeks followed by a rapid cyclosporine taper and initiation of NB-UVB phototherapy demonstrated resolution of psoriasis with fewer NB-UVB treatments and less UVB exposure than NB-UVB therapy alone.26

Final Thoughts

The FDA-approved systemic nonbiologic agents are accessible and effective treatment options for adults with widespread or inadequately controlled psoriasis. Selecting the ideal therapy requires careful consideration of medication toxicity, contraindications, monitoring requirements, and patient comorbidities. The AAD-NPF guidelines guide dermatologists in prescribing systemic nonbiologic treatments in adults with psoriasis. Utilizing these recommendations in combination with clinician judgment will help patients achieve safe and optimal psoriasis clearance.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486.

- Mrowietz U, Barker J, Boehncke WH, et al. Clinical use of dimethyl fumarate in moderate-to-severe plaque-type psoriasis: a European expert consensus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(suppl 3):3-14.

- Van Voorhees AS, Gold LS, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis of the scalp: results of a phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:96-103.

- Buccheri L, Katchen BR, Karter AJ, et al. Acitretin therapy is effective for psoriasis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:711-715.

- Ormerod AD, Campalani E, Goodfield MJD. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines on the efficacy and use of acitretin in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:952-963.

- Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Longterm (52-week) results of a phase III randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:479-488.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Antares Pharma, Inc. Otrexup PFS (methotrexate) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised June 2019. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/204824s009lbl.pdf

- David M, Hodak E, Lowe NJ. Adverse effects of retinoids. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1988;3:273-288.

- Stiefel Laboratories, Inc. Soriatane (acitretin) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised September 2017. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/019821s028lbl.pdf

- Celgene Corporation. Otezla (apremilast) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised March 2014. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205437s000lbl.pdf

- Ghanem ME, El-Baghdadi LA, Badawy AM, et al. Pregnancy outcome after renal allograft transplantation: 15 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121:178-181.

- Zerilli T, Ocheretyaner E. Apremilast (Otezla): A new oral treatment for adults with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. P T. 2015;40:495-500.

- Kivity S, Zafrir Y, Loebstein R, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for low dose methotrexate toxicity: a cohort of 28 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1109-1113.

- Boffa MJ, Chalmers RJ. Methotrexate for psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:399-408.

- Rosenberg P, Urwitz H, Johannesson A, et al. Psoriasis patients with diabetes type 2 are at high risk of developing liver fibrosis during methotrexate treatment. J Hepatol. 2007;46:1111-1118.

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Sandimmune (cyclosporine) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published 2015. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/050573s041,050574s051,050625s055lbl.pdf

- Maza A, Montaudie H, Sbidian E, et al. Oral cyclosporin in psoriasis: a systematic review on treatment modalities, risk of kidney toxicity and evidence for use in non-plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 2):19-27.

- Yamauchi PS, Rizk D, Kormilli T, et al. Systemic retinoids. In: Weinstein GD, Gottlieb AB, eds. Therapy of Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. Marcel Dekker; 2003:137-150.

- van Ditzhuijsen TJ, van Haelst UJ, van Dooren-Greebe RJ, et al. Severe hepatotoxic reaction with progression to cirrhosis after use of a novel retinoid (acitretin). J Hepatol. 1990;11:185-188.

- AbuHilal M, Walsh S, Shear N. Use of apremilast in combination with other therapies for treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:313-316.

- Gottlieb AB, Langley RG, Strober BE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the addition of methotrexate to etanercept in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:649-657.

- Cronstein BN. Methotrexate BAFFles anti-drug antibodies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:505-506.

- Lebwohl M, Drake L, Menter A, et al. Consensus conference: acitretin in combination with UVB or PUVA in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:544-553.

- Nijsten TE, Stern RS. Oral retinoid use reduces cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma risk in patients with psoriasis treated with psoralen-UVA: a nested cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:644-650.

- Calzavara-Pinton P, Leone G, Venturini M, et al. A comparative non randomized study of narrow-band (NB) (312 +/- 2 nm) UVB phototherapy versus sequential therapy with oral administration of low-dose cyclosporin A and NB-UVB phototherapy in patients with severe psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:470-473.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486.

- Mrowietz U, Barker J, Boehncke WH, et al. Clinical use of dimethyl fumarate in moderate-to-severe plaque-type psoriasis: a European expert consensus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(suppl 3):3-14.

- Van Voorhees AS, Gold LS, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis of the scalp: results of a phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:96-103.

- Buccheri L, Katchen BR, Karter AJ, et al. Acitretin therapy is effective for psoriasis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:711-715.

- Ormerod AD, Campalani E, Goodfield MJD. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines on the efficacy and use of acitretin in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:952-963.

- Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Longterm (52-week) results of a phase III randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:479-488.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Antares Pharma, Inc. Otrexup PFS (methotrexate) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised June 2019. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/204824s009lbl.pdf

- David M, Hodak E, Lowe NJ. Adverse effects of retinoids. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1988;3:273-288.

- Stiefel Laboratories, Inc. Soriatane (acitretin) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised September 2017. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/019821s028lbl.pdf

- Celgene Corporation. Otezla (apremilast) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised March 2014. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205437s000lbl.pdf

- Ghanem ME, El-Baghdadi LA, Badawy AM, et al. Pregnancy outcome after renal allograft transplantation: 15 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121:178-181.

- Zerilli T, Ocheretyaner E. Apremilast (Otezla): A new oral treatment for adults with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. P T. 2015;40:495-500.

- Kivity S, Zafrir Y, Loebstein R, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for low dose methotrexate toxicity: a cohort of 28 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1109-1113.

- Boffa MJ, Chalmers RJ. Methotrexate for psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:399-408.

- Rosenberg P, Urwitz H, Johannesson A, et al. Psoriasis patients with diabetes type 2 are at high risk of developing liver fibrosis during methotrexate treatment. J Hepatol. 2007;46:1111-1118.

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Sandimmune (cyclosporine) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published 2015. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/050573s041,050574s051,050625s055lbl.pdf

- Maza A, Montaudie H, Sbidian E, et al. Oral cyclosporin in psoriasis: a systematic review on treatment modalities, risk of kidney toxicity and evidence for use in non-plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 2):19-27.

- Yamauchi PS, Rizk D, Kormilli T, et al. Systemic retinoids. In: Weinstein GD, Gottlieb AB, eds. Therapy of Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. Marcel Dekker; 2003:137-150.

- van Ditzhuijsen TJ, van Haelst UJ, van Dooren-Greebe RJ, et al. Severe hepatotoxic reaction with progression to cirrhosis after use of a novel retinoid (acitretin). J Hepatol. 1990;11:185-188.

- AbuHilal M, Walsh S, Shear N. Use of apremilast in combination with other therapies for treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:313-316.

- Gottlieb AB, Langley RG, Strober BE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the addition of methotrexate to etanercept in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:649-657.

- Cronstein BN. Methotrexate BAFFles anti-drug antibodies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:505-506.

- Lebwohl M, Drake L, Menter A, et al. Consensus conference: acitretin in combination with UVB or PUVA in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:544-553.

- Nijsten TE, Stern RS. Oral retinoid use reduces cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma risk in patients with psoriasis treated with psoralen-UVA: a nested cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:644-650.

- Calzavara-Pinton P, Leone G, Venturini M, et al. A comparative non randomized study of narrow-band (NB) (312 +/- 2 nm) UVB phototherapy versus sequential therapy with oral administration of low-dose cyclosporin A and NB-UVB phototherapy in patients with severe psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:470-473.

Practice Points

- Systemic nonbiologic therapies are effective treatments for adults with psoriasis. The benefits of these treatments include ease of administration and the ability to control widespread disease.

- When selecting a therapy, a thorough evaluation of patient characteristics and commitment to lifestyle adjustments is necessary, including careful consideration in women of childbearing potential and those with plans of starting a family.

- Regular drug monitoring and patient follow-up is crucial to ensure safe dosing adjustments and to mitigate potential adverse effects.

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for the Management of Psoriasis With Phototherapy

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 Although topical therapies often are the first-line treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis, approximately 1 in 6 individuals has moderate to severe disease that requires systemic treatment such as biologics or phototherapy.2 In patients with localized disease that is refractory to treatment or who have moderate to severe psoriasis requiring systemic treatment, phototherapy should be considered as a potential low-risk treatment option.

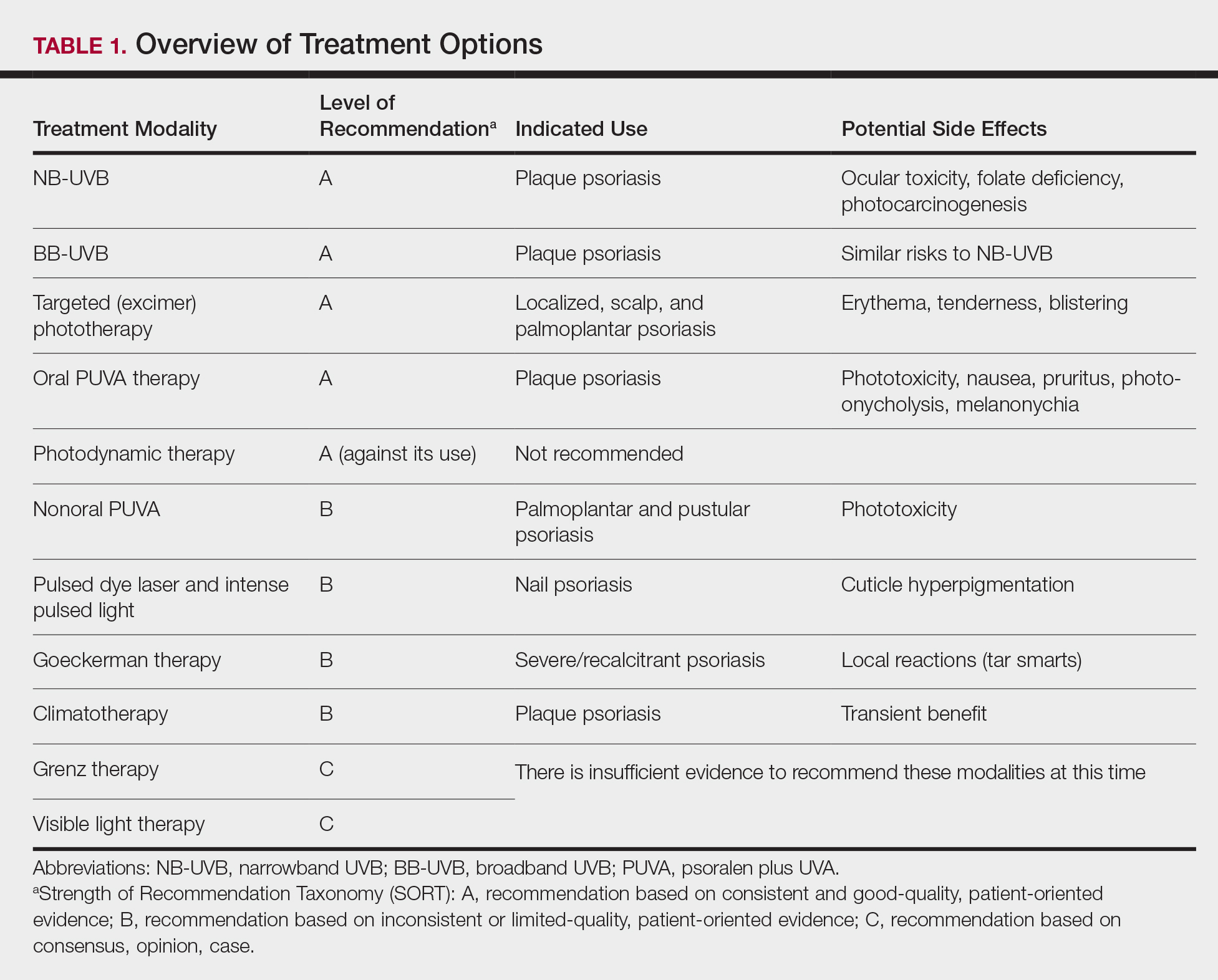

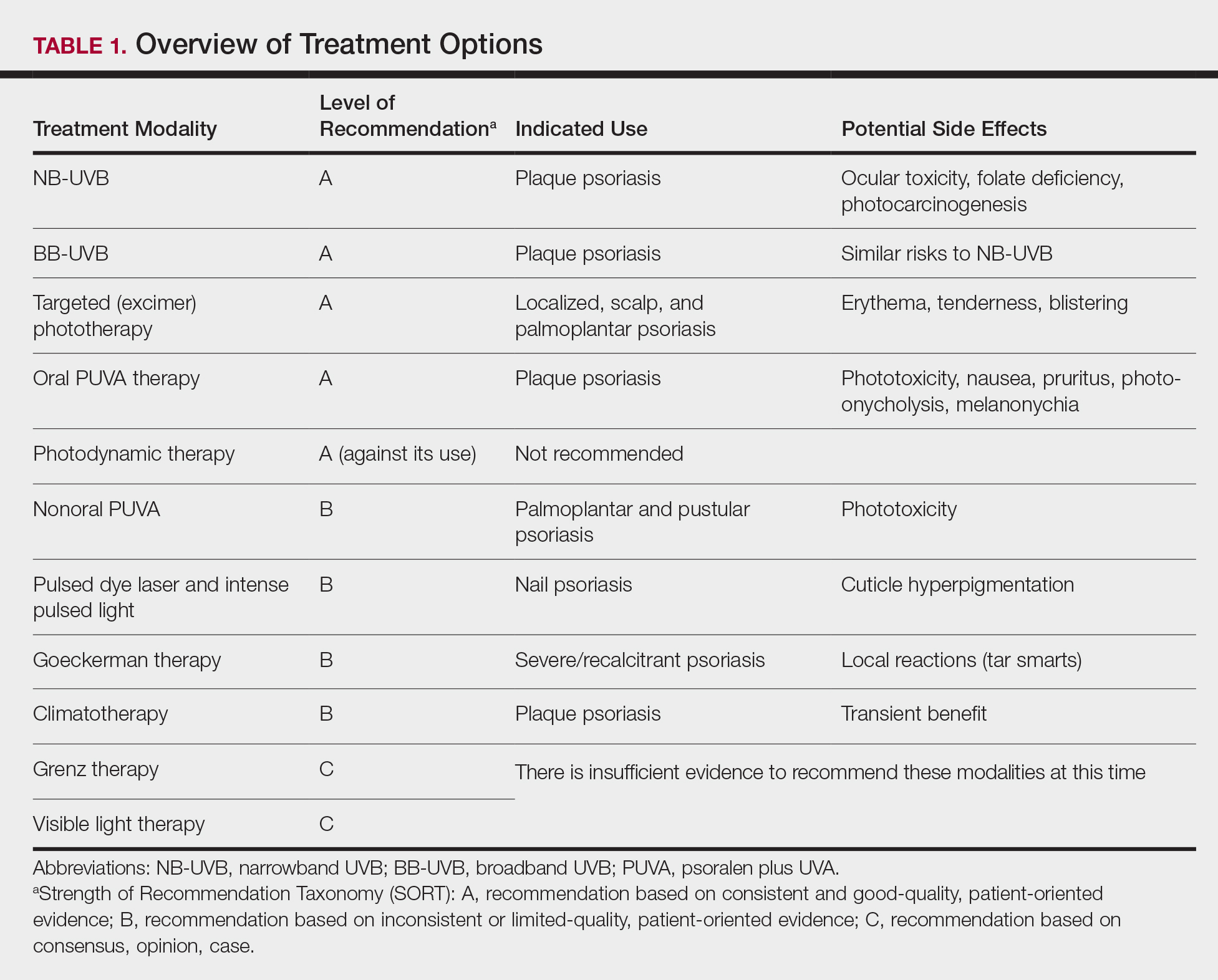

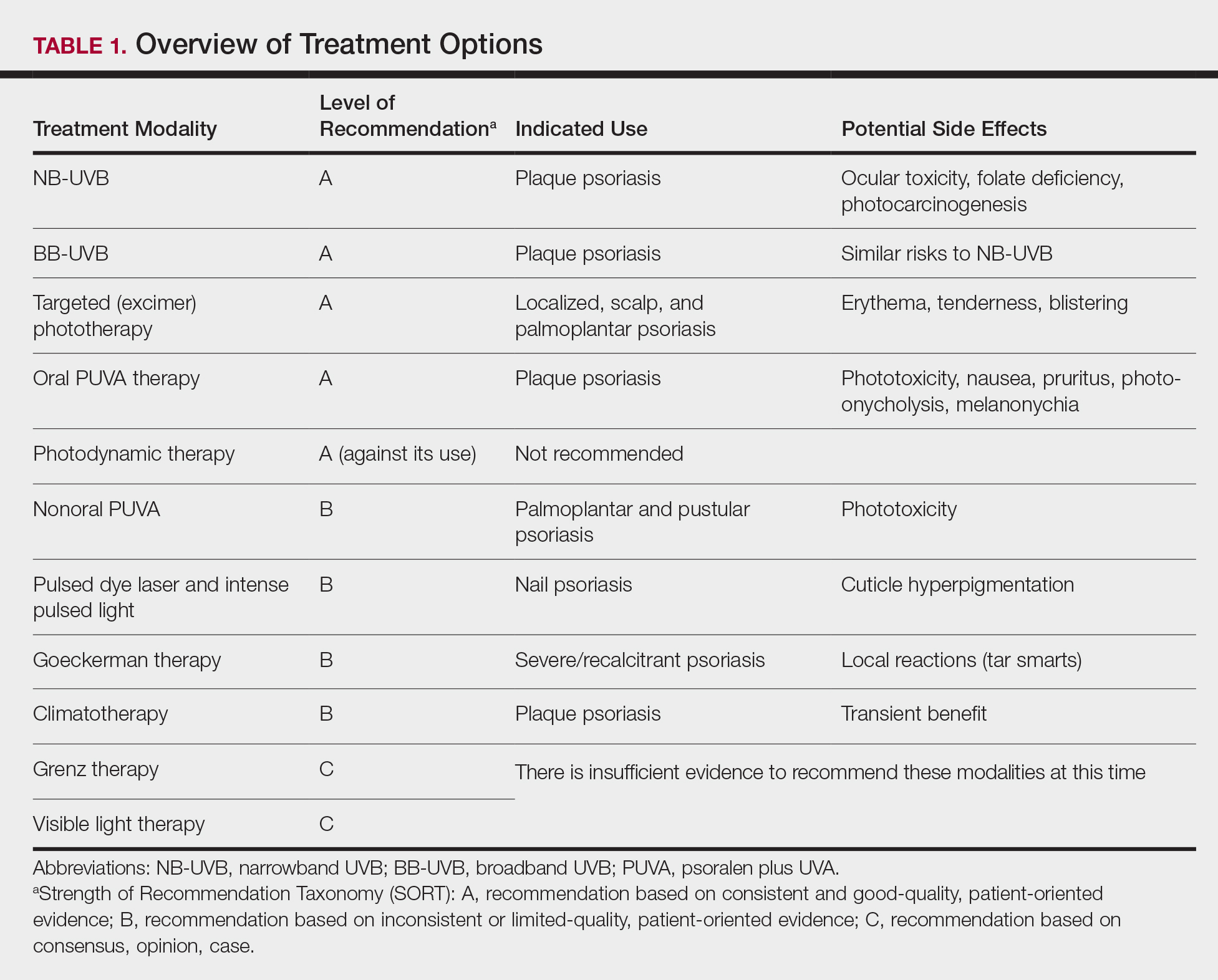

In July 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of phototherapy in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 Since the prior guidelines were released in 2010, there have been numerous studies affirming the efficacy of phototherapy, with several large meta-analyses helping to refine clinical recommendations.4,5 Each treatment was ranked using Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, with a score of A, B, or C based on the strength of the evidence supporting the given modality. With the ever-increasing number of treatment options for patients with psoriasis, these guidelines inform dermatologists of the recommendations for the initiation, maintenance, and optimization of phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and frequency of adverse events of 10 commonly used phototherapy/photochemotherapy modalities. They also address dosing regimens, the potential to combine phototherapy with other therapies, and the efficacy of treatment modalities for different types of psoriasis.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form for prescribers of phototherapy and to review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we only highlight the treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to pediatric patients with psoriasis.

Choosing a Phototherapy Modality

Phototherapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% body surface area or for localized disease refractory to conventional treatments. UV light is believed to provide relief from psoriasis via multiple mechanisms, such as through favorable alterations in cytokine profiles, initiation of apoptosis, and local immunosupression.6 There is no single first-line phototherapeutic modality recommended for all patients with psoriasis. Rather, the decision to implement a particular modality should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as percentage of body surface area affected by disease, quality-of-life assessment, comorbidities, lifestyle, and cost of treatment.

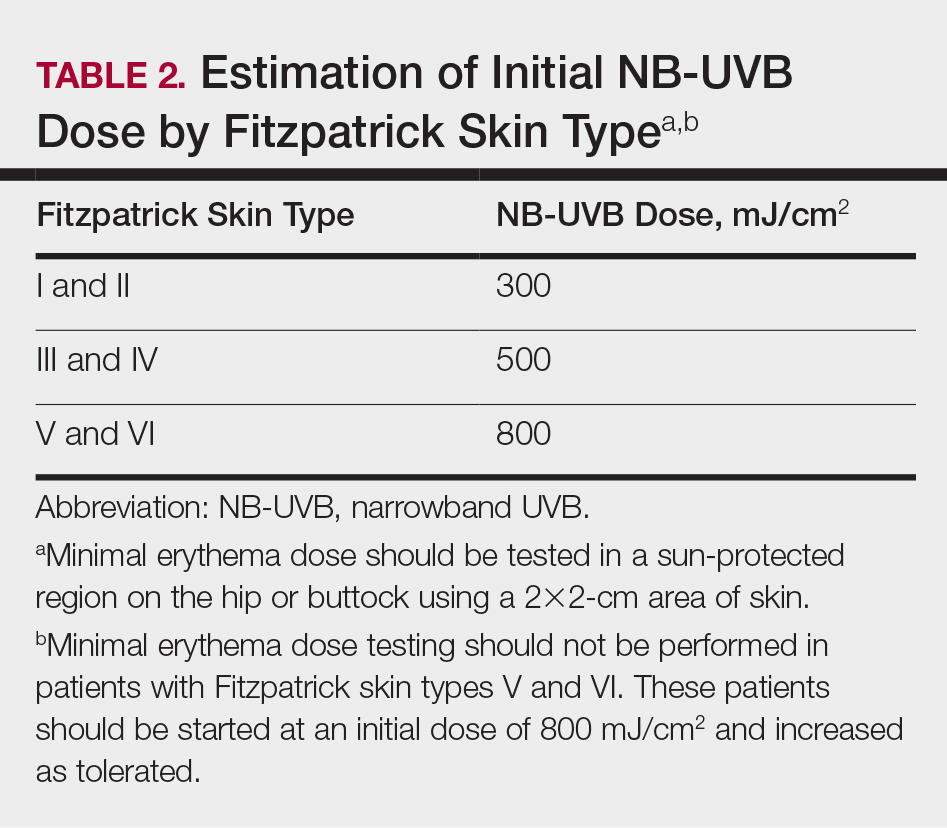

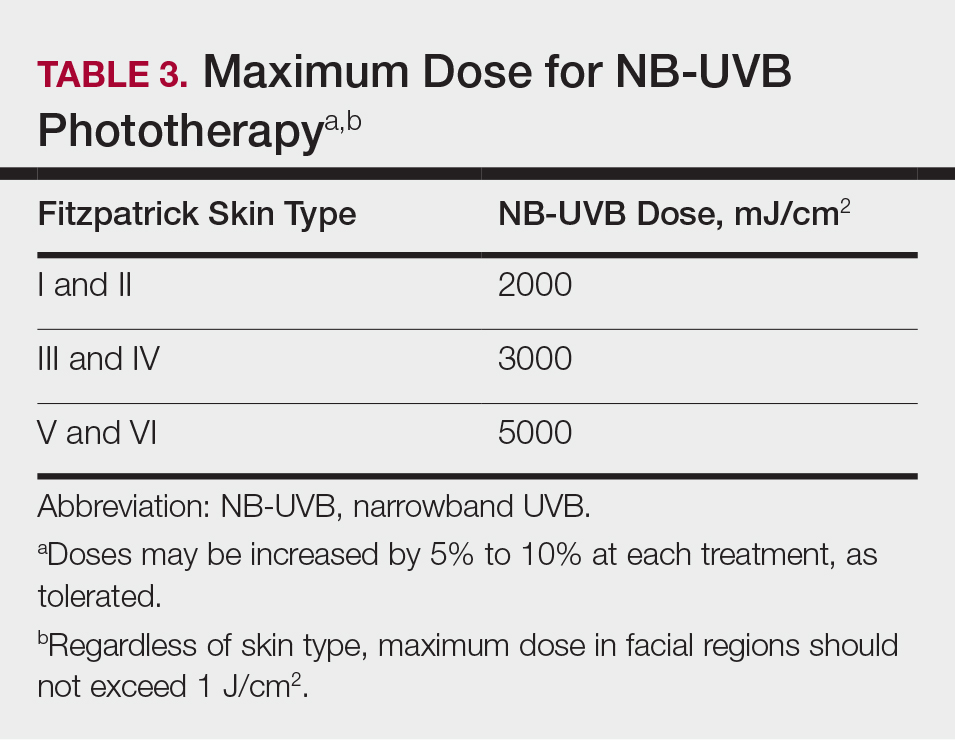

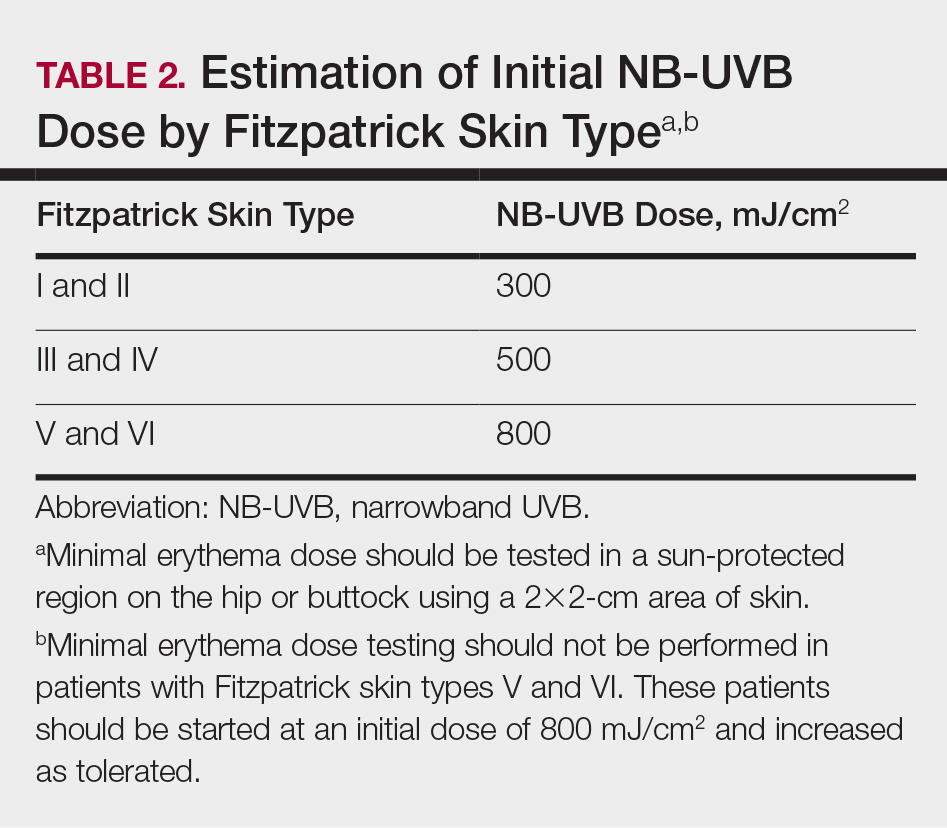

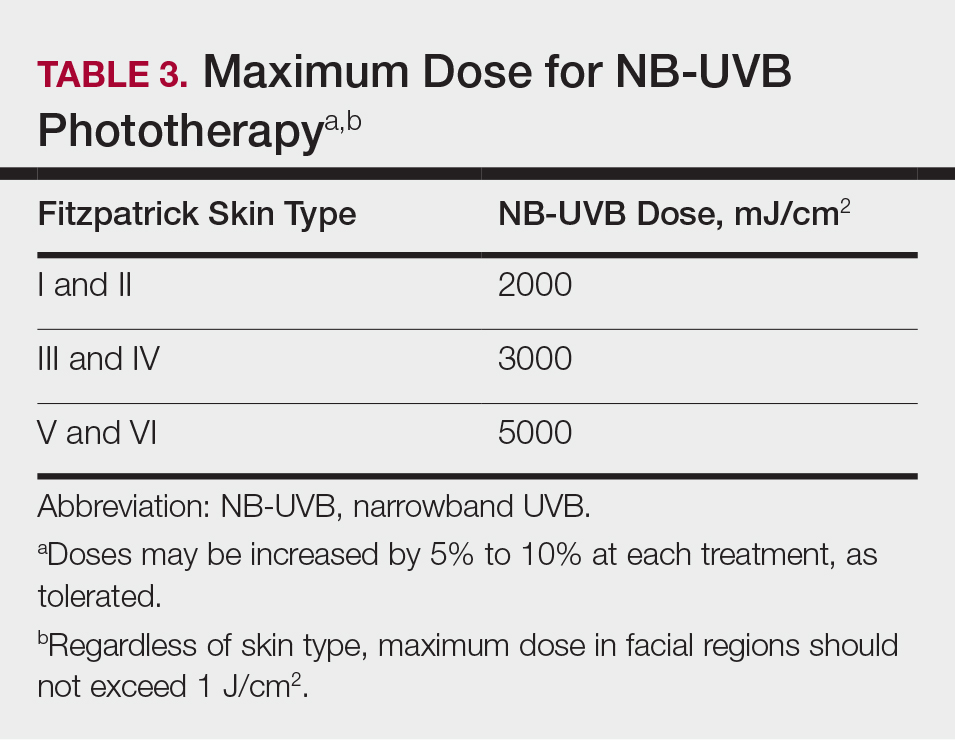

Of the 10 phototherapy modalities reviewed in these guidelines, 4 were ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Treatments with a grade A level of recommendation included narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), broadband UVB (BB-UVB), targeted phototherapy (excimer laser and excimer lamp), and

Studies have shown that the ideal wavelength needed to produce a therapeutic effect (ie, clearance of psoriatic plaques) is 304 to 313 nm. Wavelengths of 290 to 300 nm were found to be less therapeutic and more harmful, as they contributed to the development of sunburns.7 Broadband UVB phototherapy, with wavelengths ranging from 270 to 390 nm, exposes patients to a greater spectrum of radiation, thus making it more likely to cause sunburn and any theoretical form of sun-related damage, such as dysplasia and cancer. Compared with NB-UVB phototherapy, BB-UVB phototherapy is associated with a greater degree of sun damage–related side effects. Narrowband UVB, with a wavelength range of 311 to 313 nm, carries a grade A level of recommendation and should be considered as first-line monotherapy in patients with generalized plaque psoriasis, given its efficacy and promising safety profile. Multiple studies have shown that NB-UVB phototherapy is superior to BB-UVB phototherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in adults.8,9 In facilities where access to NB-UVB is limited, BB-UVB monotherapy is recommended as the treatment of generalized plaque psoriasis.

Psoralen plus UVA, which may be used topically (ie, bathwater PUVA) or taken orally, refers to treatment with photosensitizing psoralens. Psoralens are agents that intercalate with DNA and enhance the efficacy of phototherapy.10 Topical PUVA, with a grade B level of recommendation, is an effective treatment option for patients with localized disease and has been shown to be particularly efficacious in the treatment of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis. Oral PUVA is an effective option for psoriasis with a grade A recommendation, while bathwater PUVA has a grade B level of recommendation for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Oral PUVA is associated with greater systemic side effects (both acute and subacute) compared with NB-UVB and also is associated with photocarcinogenesis, particularly squamous cell carcinoma in white patients.11 Other side effects from PUVA include pigmented macules in sun-protected areas (known as PUVA lentigines), which may make evaluation of skin lesions challenging. Because of the increased risk for cancer with oral PUVA, NB-UVB is preferable as a first-line treatment vs PUVA, especially in patients with a history of skin cancer.12,13

Goeckerman therapy, which involves the synergistic combination of UVB and crude coal tar, is an older treatment that has shown efficacy in the treatment of severe or recalcitrant psoriasis (grade B level of recommendation). One prior case-control study comparing the efficacy of Goeckerman therapy with newer treatments, such as biologic therapies, steroids, and oral immunosuppressants, found a similar reduction in symptoms among both treatment groups, with longer disease-free periods in patients who received Goeckerman therapy than those who received newer therapies (22.3 years vs 4.6 months).14 However, Goeckerman therapy is utilized less frequently than more modern therapies because of the time required for treatment and declining insurance reimbursements for it. Climatotherapy, another older established therapy, involves the temporary or permanent relocation of patients to an environment that is favorable for disease control (grade B level of recommendation). Locations such as the Dead Sea and Canary Islands have been studied and shown to provide both subjective and objective improvement in patients’ psoriasis disease course. Patients had notable improvement in both their psoriasis area and severity index score and quality of life after a 3- to 4-week relocation to these areas.15,16 Access to climatotherapy and the transient nature of disease relief are apparent limitations of this treatment modality.