User login

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for the Management of Psoriasis With Phototherapy

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 Although topical therapies often are the first-line treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis, approximately 1 in 6 individuals has moderate to severe disease that requires systemic treatment such as biologics or phototherapy.2 In patients with localized disease that is refractory to treatment or who have moderate to severe psoriasis requiring systemic treatment, phototherapy should be considered as a potential low-risk treatment option.

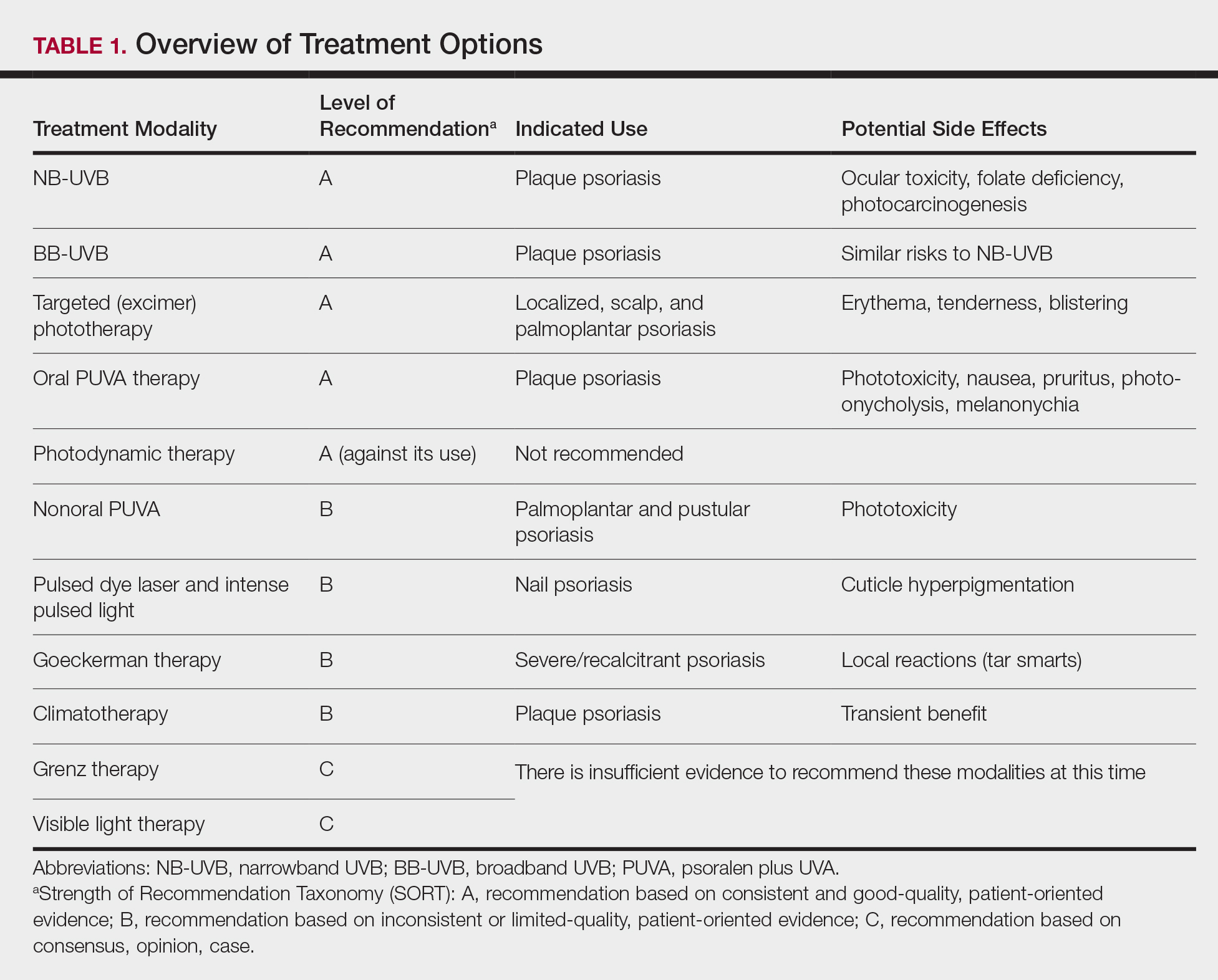

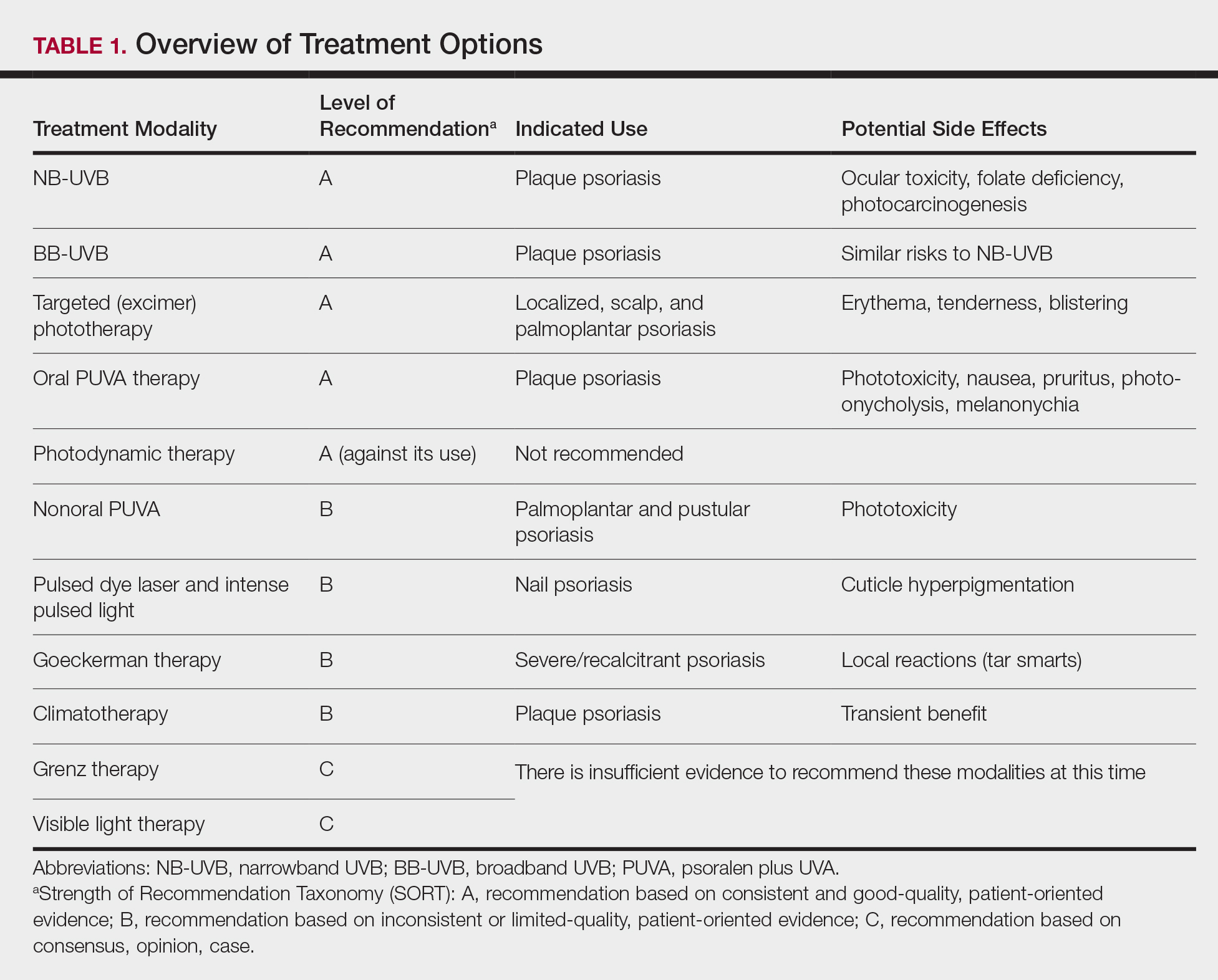

In July 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of phototherapy in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 Since the prior guidelines were released in 2010, there have been numerous studies affirming the efficacy of phototherapy, with several large meta-analyses helping to refine clinical recommendations.4,5 Each treatment was ranked using Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, with a score of A, B, or C based on the strength of the evidence supporting the given modality. With the ever-increasing number of treatment options for patients with psoriasis, these guidelines inform dermatologists of the recommendations for the initiation, maintenance, and optimization of phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and frequency of adverse events of 10 commonly used phototherapy/photochemotherapy modalities. They also address dosing regimens, the potential to combine phototherapy with other therapies, and the efficacy of treatment modalities for different types of psoriasis.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form for prescribers of phototherapy and to review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we only highlight the treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to pediatric patients with psoriasis.

Choosing a Phototherapy Modality

Phototherapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% body surface area or for localized disease refractory to conventional treatments. UV light is believed to provide relief from psoriasis via multiple mechanisms, such as through favorable alterations in cytokine profiles, initiation of apoptosis, and local immunosupression.6 There is no single first-line phototherapeutic modality recommended for all patients with psoriasis. Rather, the decision to implement a particular modality should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as percentage of body surface area affected by disease, quality-of-life assessment, comorbidities, lifestyle, and cost of treatment.

Of the 10 phototherapy modalities reviewed in these guidelines, 4 were ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Treatments with a grade A level of recommendation included narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), broadband UVB (BB-UVB), targeted phototherapy (excimer laser and excimer lamp), and

Studies have shown that the ideal wavelength needed to produce a therapeutic effect (ie, clearance of psoriatic plaques) is 304 to 313 nm. Wavelengths of 290 to 300 nm were found to be less therapeutic and more harmful, as they contributed to the development of sunburns.7 Broadband UVB phototherapy, with wavelengths ranging from 270 to 390 nm, exposes patients to a greater spectrum of radiation, thus making it more likely to cause sunburn and any theoretical form of sun-related damage, such as dysplasia and cancer. Compared with NB-UVB phototherapy, BB-UVB phototherapy is associated with a greater degree of sun damage–related side effects. Narrowband UVB, with a wavelength range of 311 to 313 nm, carries a grade A level of recommendation and should be considered as first-line monotherapy in patients with generalized plaque psoriasis, given its efficacy and promising safety profile. Multiple studies have shown that NB-UVB phototherapy is superior to BB-UVB phototherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in adults.8,9 In facilities where access to NB-UVB is limited, BB-UVB monotherapy is recommended as the treatment of generalized plaque psoriasis.

Psoralen plus UVA, which may be used topically (ie, bathwater PUVA) or taken orally, refers to treatment with photosensitizing psoralens. Psoralens are agents that intercalate with DNA and enhance the efficacy of phototherapy.10 Topical PUVA, with a grade B level of recommendation, is an effective treatment option for patients with localized disease and has been shown to be particularly efficacious in the treatment of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis. Oral PUVA is an effective option for psoriasis with a grade A recommendation, while bathwater PUVA has a grade B level of recommendation for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Oral PUVA is associated with greater systemic side effects (both acute and subacute) compared with NB-UVB and also is associated with photocarcinogenesis, particularly squamous cell carcinoma in white patients.11 Other side effects from PUVA include pigmented macules in sun-protected areas (known as PUVA lentigines), which may make evaluation of skin lesions challenging. Because of the increased risk for cancer with oral PUVA, NB-UVB is preferable as a first-line treatment vs PUVA, especially in patients with a history of skin cancer.12,13

Goeckerman therapy, which involves the synergistic combination of UVB and crude coal tar, is an older treatment that has shown efficacy in the treatment of severe or recalcitrant psoriasis (grade B level of recommendation). One prior case-control study comparing the efficacy of Goeckerman therapy with newer treatments, such as biologic therapies, steroids, and oral immunosuppressants, found a similar reduction in symptoms among both treatment groups, with longer disease-free periods in patients who received Goeckerman therapy than those who received newer therapies (22.3 years vs 4.6 months).14 However, Goeckerman therapy is utilized less frequently than more modern therapies because of the time required for treatment and declining insurance reimbursements for it. Climatotherapy, another older established therapy, involves the temporary or permanent relocation of patients to an environment that is favorable for disease control (grade B level of recommendation). Locations such as the Dead Sea and Canary Islands have been studied and shown to provide both subjective and objective improvement in patients’ psoriasis disease course. Patients had notable improvement in both their psoriasis area and severity index score and quality of life after a 3- to 4-week relocation to these areas.15,16 Access to climatotherapy and the transient nature of disease relief are apparent limitations of this treatment modality.

Grenz ray is a type of phototherapy that uses longer-wavelength ionizing radiation, which has low penetrance into surrounding tissues and a 95% absorption rate within the first 3 mm of the skin depth. This treatment has been used less frequently since the development of newer alternatives but should still be considered as a second line to UV therapy, especially in cases of recalcitrant disease and palmoplantar psoriasis, and when access to other treatment options is limited. Grenz ray has a grade C level of recommendation due to the paucity of evidence that supports its efficacy. Thus, it is not recommended as first-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Visible light therapy is another treatment option that uses light in the visible wavelength spectrum but predominantly utilizes blue and red light. Psoriatic lesions are sensitive to light therapy because of the elevated levels of naturally occurring photosensitizing agents, called protoporphyrins, in these lesions.17 Several small studies have shown improvement in psoriatic lesions treated with visible light therapy, with blue light showing greater efficacy in lesional clearance than red light.18,19

Pulsed dye laser is a phototherapy modality that has shown efficacy in the treatment of nail psoriasis (grade B level of recommendation). One study comparing the effects of tazarotene cream 0.1% with pulsed dye laser and tazarotene cream 0.1% alone showed that patients receiving combination therapy had a greater decrease in

Initiation of Phototherapy

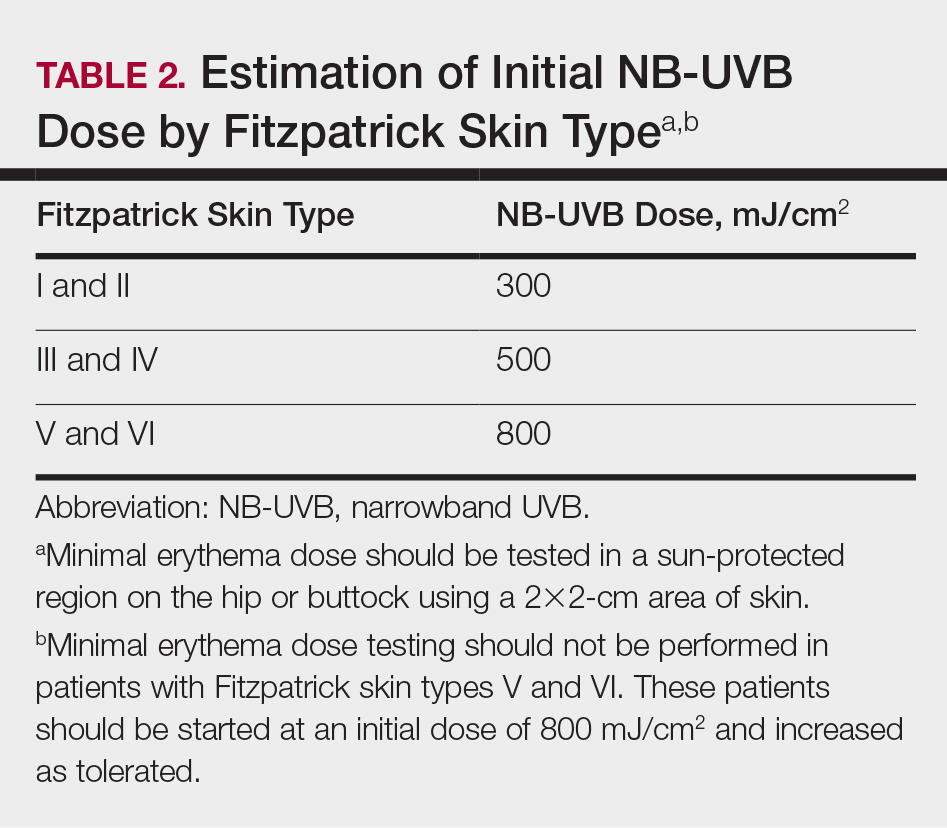

Prior to initiating phototherapy, it is important to assess the patient for any personal or family history of skin cancer, as phototherapy carries an increased risk for cutaneous malignancy, especially in patients with a history of skin cancer.22,23 All patients also should be evaluated for their Fitzpatrick skin type, and the minimal erythema dose should be defined for those initiating UVB treatment. These classifications can be useful for the initial determination of treatment dose and the prevention of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). A careful drug history also should be taken before the initiation of phototherapy to avoid photosensitizing reactions. Thiazide diuretics and tetracyclines are 2 such examples of medications commonly associated with photosensitizing reactions.24

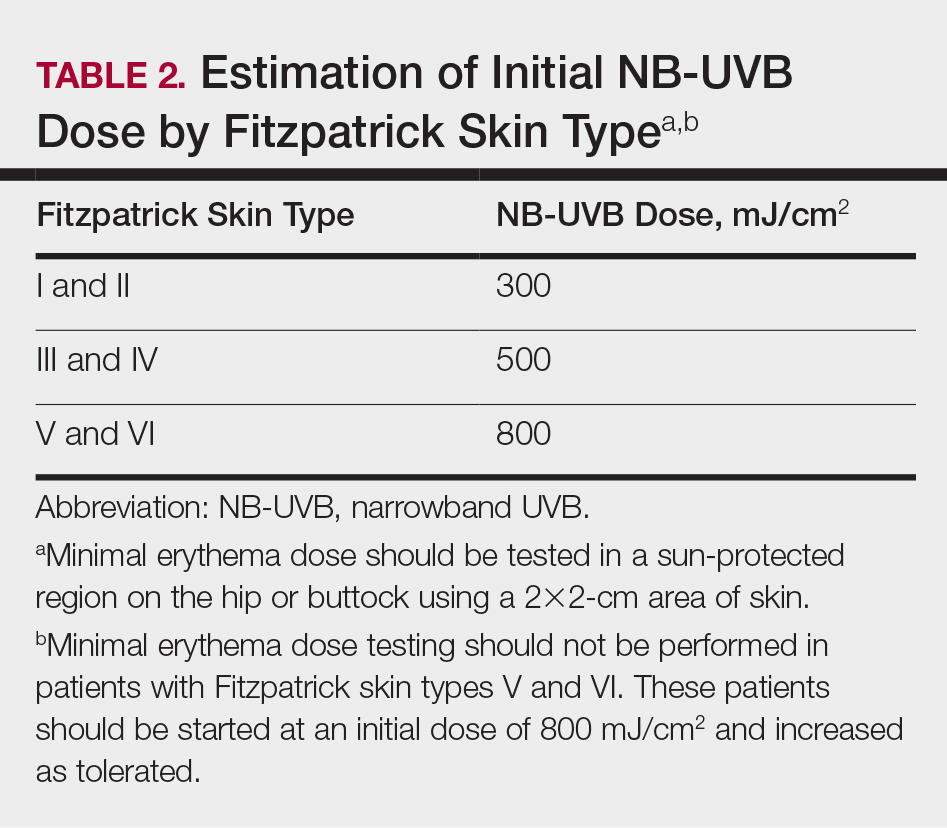

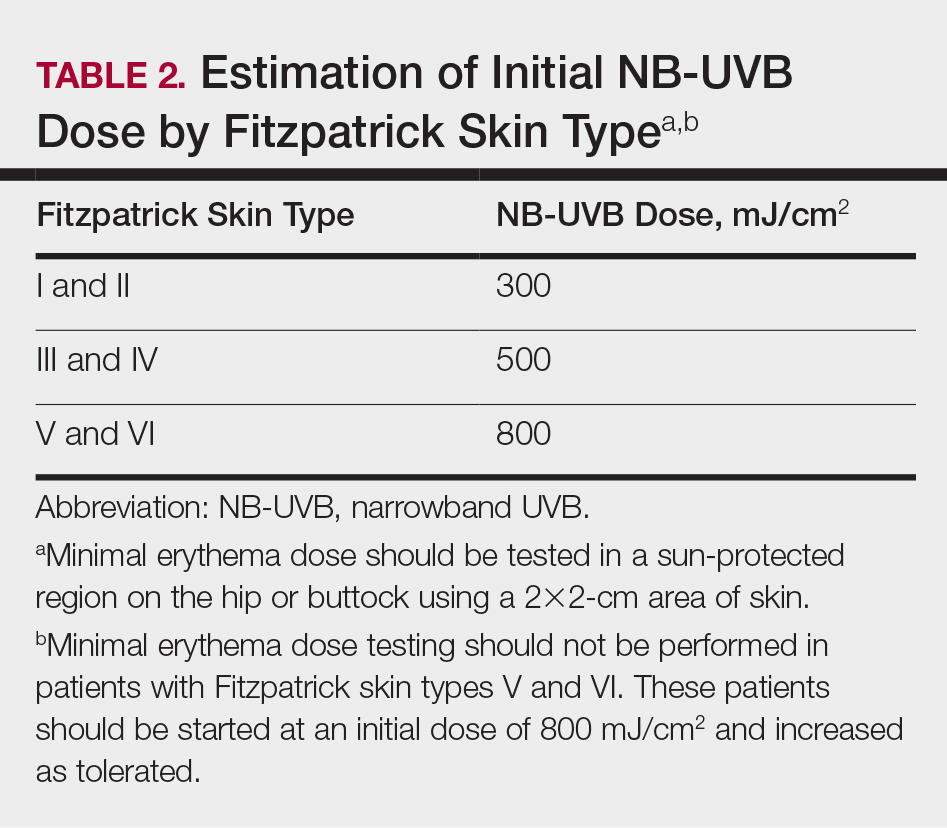

Fitzpatrick skin type and/or minimal erythema dose testing also are essential in determining the appropriate initial NB-UVB dose required for treatment initiation (Table 2). Patient response to the initial NB-UVB trial will determine the optimal dosage for subsequent maintenance treatments.

For patients unable or unwilling to commit to office-based or institution-based treatments, home NB-UVB is another therapeutic option. One study comparing patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who received home NB-UVB vs in-office treatment showed comparable psoriasis area and severity index scores and quality-of-life indices and no difference in the frequency of TRAE indices. It is important to note that patients who received home treatment had a significantly lower treatment burden (P≤.001) and greater treatment satisfaction than those receiving treatment in an office-based setting (P=.001).25

Assessment and Optimization of Phototherapy

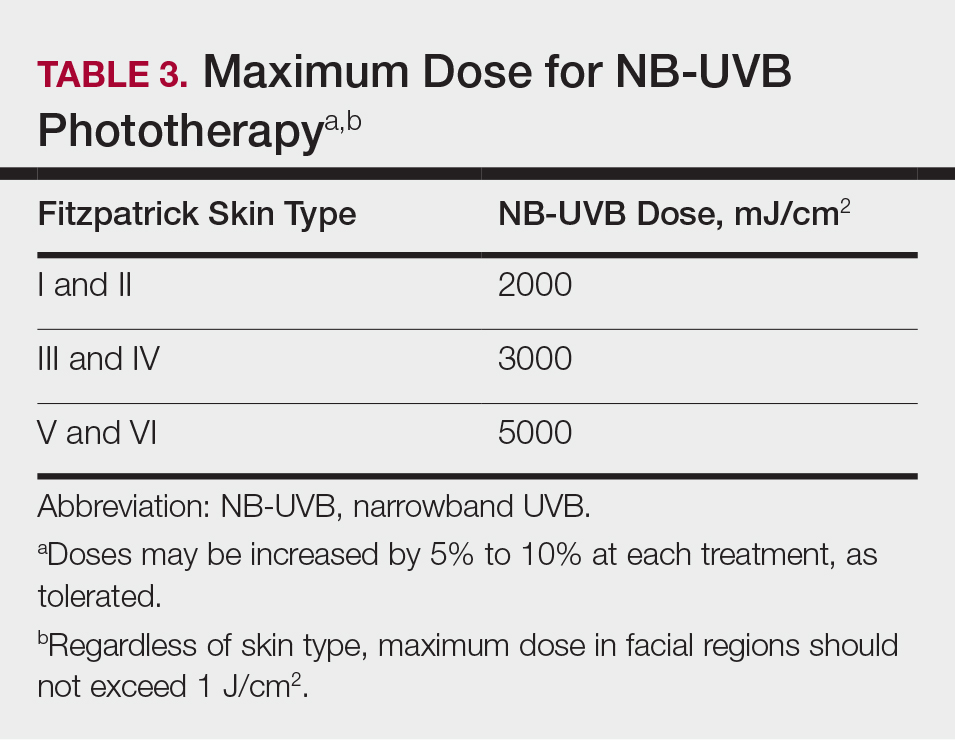

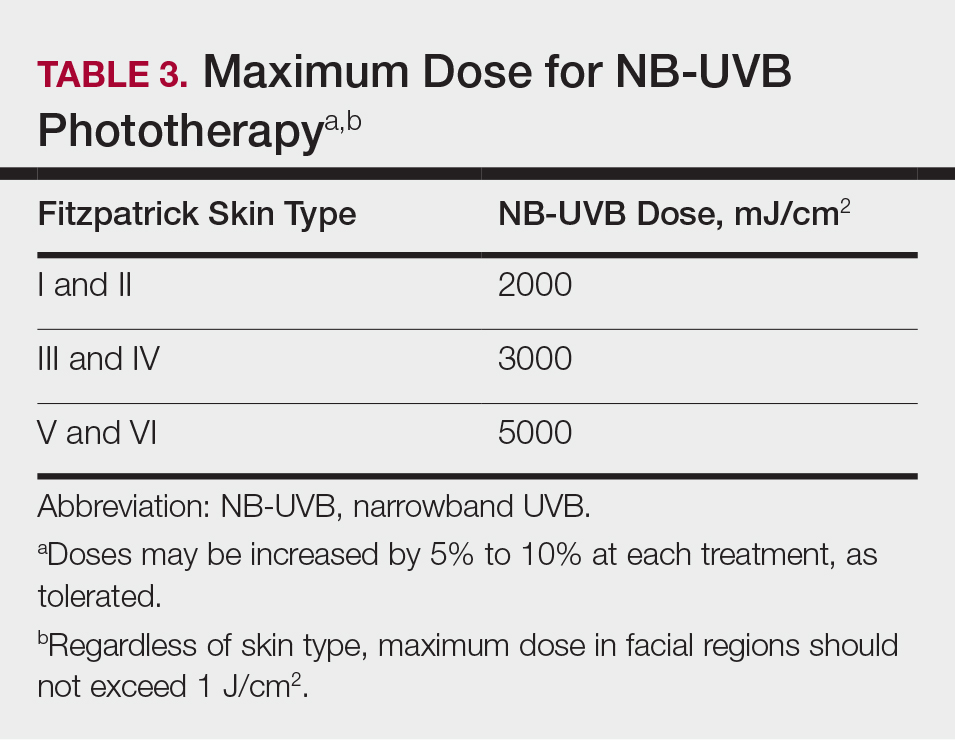

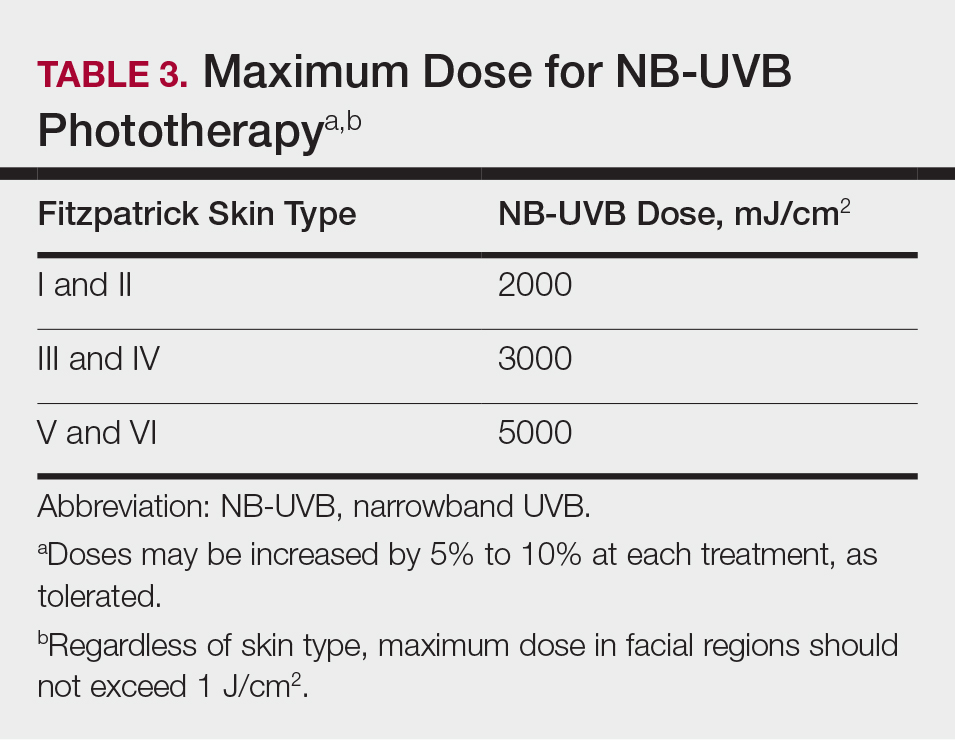

After an appropriate starting dosage has been established, patients should be evaluated at each subsequent visit for the degree of treatment response. Excessive erythema (lasting more than 48 hours) or adverse effects, such as itching, stinging, or burning, are indications that the patient should have their dose adjusted back to the last dose without such adverse responses. Because tolerance to treatment develops over time, patients who miss a scheduled dose of NB-UVB phototherapy require their dose to be temporarily lowered. Targeted dosage of UVB phototherapy at a frequency of 2 to 3 times weekly is preferred over treatment 1 to 2 times weekly; however, consideration should be given toward patient preference.26 Dosing may be increased at a rate of 5% to 10% after each treatment, as tolerated, if there is no clearance of skin lesions with the original treatment dose. Patient skin type also is helpful in dictating the maximum phototherapy dose for each patient (Table 3).

Once a patient’s psoriatic lesions have cleared, the patient has the option to taper or indefinitely continue maintenance therapy. The established protocol for patients who choose to taper therapy is treatment twice weekly for 4 weeks, followed by once-weekly treatment for the second month. The maintenance dosage is held constant during the taper. For patients who prefer indefinite maintenance therapy, treatment is administered every 1 to 2 weeks, with a maintenance dosage that is approximately 25% lower than the original maintenance dosage.

Treatment Considerations

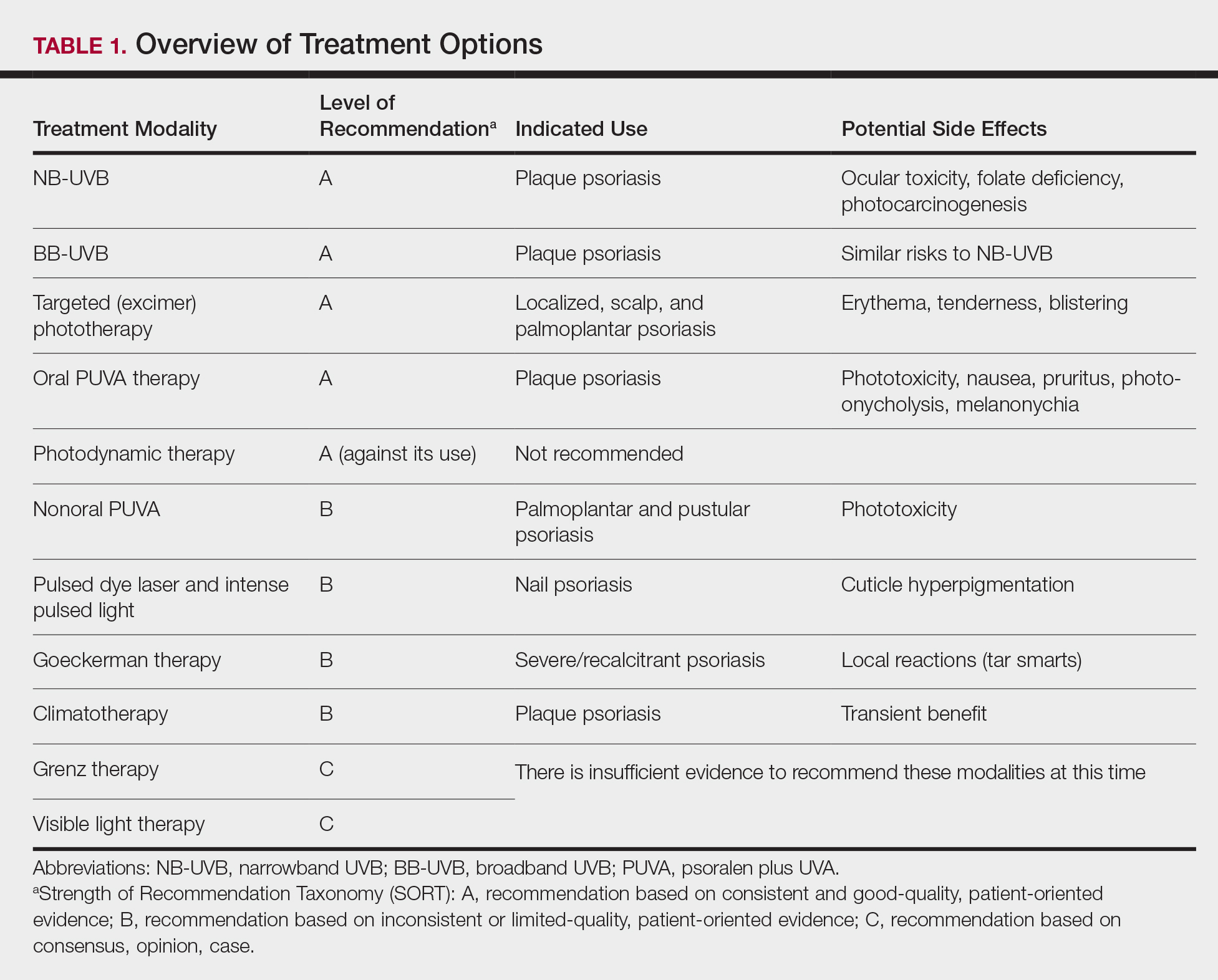

Efforts should be made to ensure that the long-term sequalae of phototherapy are minimized (Table 1). Development of cataracts is a recognized consequence of prolonged UVB exposure; therefore, eye protection is recommended during all UVB treatment sessions to reduce the risk for ocular toxicity. Although pregnancy is not a contraindication to phototherapy, except for PUVA, there is a dose-dependent degradation of folate with NB-UVB treatment, so folate supplementation (0.8 mg) is recommended during NB-UVB treatment to prevent development of neural tube defects in fetuses of patients who are pregnant or who may become pregnant.27

Although phototherapy carries the theoretical risk for photocarcinogenesis, multiple studies have shown no increased risk for malignancy with either NB-UVB or BB-UVB phototherapy.22,23 Regardless, patients who develop new-onset skin cancer while receiving any phototherapeutic treatment should discuss the potential risks and benefits of continued treatment with their physician. Providers should take extra caution prior to initiating treatment, especially in patients with a history of cutaneous malignancy. Because oral PUVA is a systemic therapy, it is associated with a greater risk for photocarcinogenesis than any other modality, particularly in fair-skinned individuals. Patients younger than 10 years; pregnant or nursing patients; and those with a history of lupus, xeroderma pigmentosum, or melanoma should not receive PUVA therapy because of their increased risk for photocarcinogenesis and TRAEs.

The decision to switch patients between different phototherapy modalities during treatment should be individualized to each patient based on factors such as disease severity, quality of life, and treatment burden. Other factors to consider include dosing frequency, treatment cost, and logistical factors, such as proximity to a treatment facility. Physicians should have a detailed discussion about the risks and benefits of continuing therapy for patients who develop new-onset skin cancer during phototherapy.

Final Thoughts

Phototherapy is an effective and safe treatment for patients with psoriasis who have localized and systemic disease. There are several treatment modalities that can be tailored to patient needs and preferences, such as home NB-UVB for patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo office-based treatments. Phototherapy has few absolute contraindications; however, relative contraindications to phototherapy exist. Patients with a history of skin cancer, photosensitivity disorders, and autoimmune diseases (eg, lupus) carry greater risks for adverse events, such as sun-related damage, cancer, and dysplasia. Because these conditions may preclude patients from pursuing phototherapy as a safe and effective approach to treating moderate to severe psoriasis, these patients should be considered for other therapies, such as biologic medications, which may carry a more favorable risk-benefit ratio given that individual’s background.

- Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205-212.

- Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1173-1179.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Efficacy of psoralen UV-A therapy vs. narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):11-21.

- Chen X, Yang M, Cheng Y, et al. Narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy versus broad-band ultraviolet B or psoralen-ultraviolet A photochemotherapy for psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD009481.

- Wong T, Hsu L, Liao W. Phototherapy in psoriasis: a review of mechanisms of action. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:6-12.

- Parrish JA, Jaenicke KF. Action spectrum for phototherapy of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1981;76:359-362.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- El-Mofty M, Mostafa WZ, Bosseila M, et al. A large scale analytical study on efficacy of different photo(chemo)therapeutic modalities in the treatment of psoriasis, vitiligo and mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:428-434.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 5. guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy and photochemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:114-135.

- Murase JE, Lee EE, Koo J. Effect of ethnicity on the risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer following long-term PUVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:1016-1021.

- Bruynzeel I, Bergman W, Hartevelt HM, et al. 'High single-dose' European PUVA regimen also causes an excess of non-melanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:49-55.

- Lindelöf B, Sigurgeirsson B, Tegner E, et al. PUVA and cancer risk: the Swedish follow-up study. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:108-112.

- Chern E, Yau D, Ho JC, et al. Positive effect of modified Goeckerman regimen on quality of life and psychosocial distress in moderate and severe psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:447-451.

- Harari M, Czarnowicki T, Fluss R, et al. Patients with early-onset psoriasis achieve better results following Dead Sea climatotherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:554-559.

- Wahl AK, Langeland E, Larsen MH, et al. Positive changes in self-management and disease severity following climate therapy in people with psoriasis. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2015;95:317-321.

- Bissonnette R, Zeng H, McLean DI, et al. Psoriatic plaques exhibit red autofluorescence that is due to protoporphyrin IX. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:586-591.

- Kleinpenning MM, Otero ME, van Erp PE, et al. Efficacy of blue light vs. red light in the treatment of psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:219-225.

- Weinstabl A, Hoff-Lesch S, Merk HF, et al. Prospective randomized study on the efficacy of blue light in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology. 2011;223:251-259.

- Huang YC, Chou CL, Chiang YY. Efficacy of pulsed dye laser plus topical tazarotene versus topical tazarotene alone in psoriatic nail disease: a single-blind, intrapatient left-to-right controlled study. Lasers Surg Med. 2013;45:102-107.

- Tawfik AA. Novel treatment of nail psoriasis using the intense pulsed light: a one-year follow-up study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:763-768.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):22-31.

- Osmancevic A, Gillstedt M, Wennberg AM, et al. The risk of skin cancer in psoriasis patients treated with UVB therapy. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2014;94:425-430.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368.

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:B1542.

- Almutawa F, Thalib L, Hekman D, et al. Efficacy of localized phototherapy and photodynamic therapy for psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:5-14.

- Zhang M, Goyert G, Lim HW. Folate and phototherapy: what should we inform our patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:958-964.

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 Although topical therapies often are the first-line treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis, approximately 1 in 6 individuals has moderate to severe disease that requires systemic treatment such as biologics or phototherapy.2 In patients with localized disease that is refractory to treatment or who have moderate to severe psoriasis requiring systemic treatment, phototherapy should be considered as a potential low-risk treatment option.

In July 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of phototherapy in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 Since the prior guidelines were released in 2010, there have been numerous studies affirming the efficacy of phototherapy, with several large meta-analyses helping to refine clinical recommendations.4,5 Each treatment was ranked using Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, with a score of A, B, or C based on the strength of the evidence supporting the given modality. With the ever-increasing number of treatment options for patients with psoriasis, these guidelines inform dermatologists of the recommendations for the initiation, maintenance, and optimization of phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and frequency of adverse events of 10 commonly used phototherapy/photochemotherapy modalities. They also address dosing regimens, the potential to combine phototherapy with other therapies, and the efficacy of treatment modalities for different types of psoriasis.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form for prescribers of phototherapy and to review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we only highlight the treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to pediatric patients with psoriasis.

Choosing a Phototherapy Modality

Phototherapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% body surface area or for localized disease refractory to conventional treatments. UV light is believed to provide relief from psoriasis via multiple mechanisms, such as through favorable alterations in cytokine profiles, initiation of apoptosis, and local immunosupression.6 There is no single first-line phototherapeutic modality recommended for all patients with psoriasis. Rather, the decision to implement a particular modality should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as percentage of body surface area affected by disease, quality-of-life assessment, comorbidities, lifestyle, and cost of treatment.

Of the 10 phototherapy modalities reviewed in these guidelines, 4 were ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Treatments with a grade A level of recommendation included narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), broadband UVB (BB-UVB), targeted phototherapy (excimer laser and excimer lamp), and

Studies have shown that the ideal wavelength needed to produce a therapeutic effect (ie, clearance of psoriatic plaques) is 304 to 313 nm. Wavelengths of 290 to 300 nm were found to be less therapeutic and more harmful, as they contributed to the development of sunburns.7 Broadband UVB phototherapy, with wavelengths ranging from 270 to 390 nm, exposes patients to a greater spectrum of radiation, thus making it more likely to cause sunburn and any theoretical form of sun-related damage, such as dysplasia and cancer. Compared with NB-UVB phototherapy, BB-UVB phototherapy is associated with a greater degree of sun damage–related side effects. Narrowband UVB, with a wavelength range of 311 to 313 nm, carries a grade A level of recommendation and should be considered as first-line monotherapy in patients with generalized plaque psoriasis, given its efficacy and promising safety profile. Multiple studies have shown that NB-UVB phototherapy is superior to BB-UVB phototherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in adults.8,9 In facilities where access to NB-UVB is limited, BB-UVB monotherapy is recommended as the treatment of generalized plaque psoriasis.

Psoralen plus UVA, which may be used topically (ie, bathwater PUVA) or taken orally, refers to treatment with photosensitizing psoralens. Psoralens are agents that intercalate with DNA and enhance the efficacy of phototherapy.10 Topical PUVA, with a grade B level of recommendation, is an effective treatment option for patients with localized disease and has been shown to be particularly efficacious in the treatment of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis. Oral PUVA is an effective option for psoriasis with a grade A recommendation, while bathwater PUVA has a grade B level of recommendation for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Oral PUVA is associated with greater systemic side effects (both acute and subacute) compared with NB-UVB and also is associated with photocarcinogenesis, particularly squamous cell carcinoma in white patients.11 Other side effects from PUVA include pigmented macules in sun-protected areas (known as PUVA lentigines), which may make evaluation of skin lesions challenging. Because of the increased risk for cancer with oral PUVA, NB-UVB is preferable as a first-line treatment vs PUVA, especially in patients with a history of skin cancer.12,13

Goeckerman therapy, which involves the synergistic combination of UVB and crude coal tar, is an older treatment that has shown efficacy in the treatment of severe or recalcitrant psoriasis (grade B level of recommendation). One prior case-control study comparing the efficacy of Goeckerman therapy with newer treatments, such as biologic therapies, steroids, and oral immunosuppressants, found a similar reduction in symptoms among both treatment groups, with longer disease-free periods in patients who received Goeckerman therapy than those who received newer therapies (22.3 years vs 4.6 months).14 However, Goeckerman therapy is utilized less frequently than more modern therapies because of the time required for treatment and declining insurance reimbursements for it. Climatotherapy, another older established therapy, involves the temporary or permanent relocation of patients to an environment that is favorable for disease control (grade B level of recommendation). Locations such as the Dead Sea and Canary Islands have been studied and shown to provide both subjective and objective improvement in patients’ psoriasis disease course. Patients had notable improvement in both their psoriasis area and severity index score and quality of life after a 3- to 4-week relocation to these areas.15,16 Access to climatotherapy and the transient nature of disease relief are apparent limitations of this treatment modality.

Grenz ray is a type of phototherapy that uses longer-wavelength ionizing radiation, which has low penetrance into surrounding tissues and a 95% absorption rate within the first 3 mm of the skin depth. This treatment has been used less frequently since the development of newer alternatives but should still be considered as a second line to UV therapy, especially in cases of recalcitrant disease and palmoplantar psoriasis, and when access to other treatment options is limited. Grenz ray has a grade C level of recommendation due to the paucity of evidence that supports its efficacy. Thus, it is not recommended as first-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Visible light therapy is another treatment option that uses light in the visible wavelength spectrum but predominantly utilizes blue and red light. Psoriatic lesions are sensitive to light therapy because of the elevated levels of naturally occurring photosensitizing agents, called protoporphyrins, in these lesions.17 Several small studies have shown improvement in psoriatic lesions treated with visible light therapy, with blue light showing greater efficacy in lesional clearance than red light.18,19

Pulsed dye laser is a phototherapy modality that has shown efficacy in the treatment of nail psoriasis (grade B level of recommendation). One study comparing the effects of tazarotene cream 0.1% with pulsed dye laser and tazarotene cream 0.1% alone showed that patients receiving combination therapy had a greater decrease in

Initiation of Phototherapy

Prior to initiating phototherapy, it is important to assess the patient for any personal or family history of skin cancer, as phototherapy carries an increased risk for cutaneous malignancy, especially in patients with a history of skin cancer.22,23 All patients also should be evaluated for their Fitzpatrick skin type, and the minimal erythema dose should be defined for those initiating UVB treatment. These classifications can be useful for the initial determination of treatment dose and the prevention of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). A careful drug history also should be taken before the initiation of phototherapy to avoid photosensitizing reactions. Thiazide diuretics and tetracyclines are 2 such examples of medications commonly associated with photosensitizing reactions.24

Fitzpatrick skin type and/or minimal erythema dose testing also are essential in determining the appropriate initial NB-UVB dose required for treatment initiation (Table 2). Patient response to the initial NB-UVB trial will determine the optimal dosage for subsequent maintenance treatments.

For patients unable or unwilling to commit to office-based or institution-based treatments, home NB-UVB is another therapeutic option. One study comparing patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who received home NB-UVB vs in-office treatment showed comparable psoriasis area and severity index scores and quality-of-life indices and no difference in the frequency of TRAE indices. It is important to note that patients who received home treatment had a significantly lower treatment burden (P≤.001) and greater treatment satisfaction than those receiving treatment in an office-based setting (P=.001).25

Assessment and Optimization of Phototherapy

After an appropriate starting dosage has been established, patients should be evaluated at each subsequent visit for the degree of treatment response. Excessive erythema (lasting more than 48 hours) or adverse effects, such as itching, stinging, or burning, are indications that the patient should have their dose adjusted back to the last dose without such adverse responses. Because tolerance to treatment develops over time, patients who miss a scheduled dose of NB-UVB phototherapy require their dose to be temporarily lowered. Targeted dosage of UVB phototherapy at a frequency of 2 to 3 times weekly is preferred over treatment 1 to 2 times weekly; however, consideration should be given toward patient preference.26 Dosing may be increased at a rate of 5% to 10% after each treatment, as tolerated, if there is no clearance of skin lesions with the original treatment dose. Patient skin type also is helpful in dictating the maximum phototherapy dose for each patient (Table 3).

Once a patient’s psoriatic lesions have cleared, the patient has the option to taper or indefinitely continue maintenance therapy. The established protocol for patients who choose to taper therapy is treatment twice weekly for 4 weeks, followed by once-weekly treatment for the second month. The maintenance dosage is held constant during the taper. For patients who prefer indefinite maintenance therapy, treatment is administered every 1 to 2 weeks, with a maintenance dosage that is approximately 25% lower than the original maintenance dosage.

Treatment Considerations

Efforts should be made to ensure that the long-term sequalae of phototherapy are minimized (Table 1). Development of cataracts is a recognized consequence of prolonged UVB exposure; therefore, eye protection is recommended during all UVB treatment sessions to reduce the risk for ocular toxicity. Although pregnancy is not a contraindication to phototherapy, except for PUVA, there is a dose-dependent degradation of folate with NB-UVB treatment, so folate supplementation (0.8 mg) is recommended during NB-UVB treatment to prevent development of neural tube defects in fetuses of patients who are pregnant or who may become pregnant.27

Although phototherapy carries the theoretical risk for photocarcinogenesis, multiple studies have shown no increased risk for malignancy with either NB-UVB or BB-UVB phototherapy.22,23 Regardless, patients who develop new-onset skin cancer while receiving any phototherapeutic treatment should discuss the potential risks and benefits of continued treatment with their physician. Providers should take extra caution prior to initiating treatment, especially in patients with a history of cutaneous malignancy. Because oral PUVA is a systemic therapy, it is associated with a greater risk for photocarcinogenesis than any other modality, particularly in fair-skinned individuals. Patients younger than 10 years; pregnant or nursing patients; and those with a history of lupus, xeroderma pigmentosum, or melanoma should not receive PUVA therapy because of their increased risk for photocarcinogenesis and TRAEs.

The decision to switch patients between different phototherapy modalities during treatment should be individualized to each patient based on factors such as disease severity, quality of life, and treatment burden. Other factors to consider include dosing frequency, treatment cost, and logistical factors, such as proximity to a treatment facility. Physicians should have a detailed discussion about the risks and benefits of continuing therapy for patients who develop new-onset skin cancer during phototherapy.

Final Thoughts

Phototherapy is an effective and safe treatment for patients with psoriasis who have localized and systemic disease. There are several treatment modalities that can be tailored to patient needs and preferences, such as home NB-UVB for patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo office-based treatments. Phototherapy has few absolute contraindications; however, relative contraindications to phototherapy exist. Patients with a history of skin cancer, photosensitivity disorders, and autoimmune diseases (eg, lupus) carry greater risks for adverse events, such as sun-related damage, cancer, and dysplasia. Because these conditions may preclude patients from pursuing phototherapy as a safe and effective approach to treating moderate to severe psoriasis, these patients should be considered for other therapies, such as biologic medications, which may carry a more favorable risk-benefit ratio given that individual’s background.

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 Although topical therapies often are the first-line treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis, approximately 1 in 6 individuals has moderate to severe disease that requires systemic treatment such as biologics or phototherapy.2 In patients with localized disease that is refractory to treatment or who have moderate to severe psoriasis requiring systemic treatment, phototherapy should be considered as a potential low-risk treatment option.

In July 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of phototherapy in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 Since the prior guidelines were released in 2010, there have been numerous studies affirming the efficacy of phototherapy, with several large meta-analyses helping to refine clinical recommendations.4,5 Each treatment was ranked using Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, with a score of A, B, or C based on the strength of the evidence supporting the given modality. With the ever-increasing number of treatment options for patients with psoriasis, these guidelines inform dermatologists of the recommendations for the initiation, maintenance, and optimization of phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and frequency of adverse events of 10 commonly used phototherapy/photochemotherapy modalities. They also address dosing regimens, the potential to combine phototherapy with other therapies, and the efficacy of treatment modalities for different types of psoriasis.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form for prescribers of phototherapy and to review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we only highlight the treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to pediatric patients with psoriasis.

Choosing a Phototherapy Modality

Phototherapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% body surface area or for localized disease refractory to conventional treatments. UV light is believed to provide relief from psoriasis via multiple mechanisms, such as through favorable alterations in cytokine profiles, initiation of apoptosis, and local immunosupression.6 There is no single first-line phototherapeutic modality recommended for all patients with psoriasis. Rather, the decision to implement a particular modality should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as percentage of body surface area affected by disease, quality-of-life assessment, comorbidities, lifestyle, and cost of treatment.

Of the 10 phototherapy modalities reviewed in these guidelines, 4 were ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Treatments with a grade A level of recommendation included narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), broadband UVB (BB-UVB), targeted phototherapy (excimer laser and excimer lamp), and

Studies have shown that the ideal wavelength needed to produce a therapeutic effect (ie, clearance of psoriatic plaques) is 304 to 313 nm. Wavelengths of 290 to 300 nm were found to be less therapeutic and more harmful, as they contributed to the development of sunburns.7 Broadband UVB phototherapy, with wavelengths ranging from 270 to 390 nm, exposes patients to a greater spectrum of radiation, thus making it more likely to cause sunburn and any theoretical form of sun-related damage, such as dysplasia and cancer. Compared with NB-UVB phototherapy, BB-UVB phototherapy is associated with a greater degree of sun damage–related side effects. Narrowband UVB, with a wavelength range of 311 to 313 nm, carries a grade A level of recommendation and should be considered as first-line monotherapy in patients with generalized plaque psoriasis, given its efficacy and promising safety profile. Multiple studies have shown that NB-UVB phototherapy is superior to BB-UVB phototherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in adults.8,9 In facilities where access to NB-UVB is limited, BB-UVB monotherapy is recommended as the treatment of generalized plaque psoriasis.

Psoralen plus UVA, which may be used topically (ie, bathwater PUVA) or taken orally, refers to treatment with photosensitizing psoralens. Psoralens are agents that intercalate with DNA and enhance the efficacy of phototherapy.10 Topical PUVA, with a grade B level of recommendation, is an effective treatment option for patients with localized disease and has been shown to be particularly efficacious in the treatment of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis. Oral PUVA is an effective option for psoriasis with a grade A recommendation, while bathwater PUVA has a grade B level of recommendation for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Oral PUVA is associated with greater systemic side effects (both acute and subacute) compared with NB-UVB and also is associated with photocarcinogenesis, particularly squamous cell carcinoma in white patients.11 Other side effects from PUVA include pigmented macules in sun-protected areas (known as PUVA lentigines), which may make evaluation of skin lesions challenging. Because of the increased risk for cancer with oral PUVA, NB-UVB is preferable as a first-line treatment vs PUVA, especially in patients with a history of skin cancer.12,13

Goeckerman therapy, which involves the synergistic combination of UVB and crude coal tar, is an older treatment that has shown efficacy in the treatment of severe or recalcitrant psoriasis (grade B level of recommendation). One prior case-control study comparing the efficacy of Goeckerman therapy with newer treatments, such as biologic therapies, steroids, and oral immunosuppressants, found a similar reduction in symptoms among both treatment groups, with longer disease-free periods in patients who received Goeckerman therapy than those who received newer therapies (22.3 years vs 4.6 months).14 However, Goeckerman therapy is utilized less frequently than more modern therapies because of the time required for treatment and declining insurance reimbursements for it. Climatotherapy, another older established therapy, involves the temporary or permanent relocation of patients to an environment that is favorable for disease control (grade B level of recommendation). Locations such as the Dead Sea and Canary Islands have been studied and shown to provide both subjective and objective improvement in patients’ psoriasis disease course. Patients had notable improvement in both their psoriasis area and severity index score and quality of life after a 3- to 4-week relocation to these areas.15,16 Access to climatotherapy and the transient nature of disease relief are apparent limitations of this treatment modality.

Grenz ray is a type of phototherapy that uses longer-wavelength ionizing radiation, which has low penetrance into surrounding tissues and a 95% absorption rate within the first 3 mm of the skin depth. This treatment has been used less frequently since the development of newer alternatives but should still be considered as a second line to UV therapy, especially in cases of recalcitrant disease and palmoplantar psoriasis, and when access to other treatment options is limited. Grenz ray has a grade C level of recommendation due to the paucity of evidence that supports its efficacy. Thus, it is not recommended as first-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Visible light therapy is another treatment option that uses light in the visible wavelength spectrum but predominantly utilizes blue and red light. Psoriatic lesions are sensitive to light therapy because of the elevated levels of naturally occurring photosensitizing agents, called protoporphyrins, in these lesions.17 Several small studies have shown improvement in psoriatic lesions treated with visible light therapy, with blue light showing greater efficacy in lesional clearance than red light.18,19

Pulsed dye laser is a phototherapy modality that has shown efficacy in the treatment of nail psoriasis (grade B level of recommendation). One study comparing the effects of tazarotene cream 0.1% with pulsed dye laser and tazarotene cream 0.1% alone showed that patients receiving combination therapy had a greater decrease in

Initiation of Phototherapy

Prior to initiating phototherapy, it is important to assess the patient for any personal or family history of skin cancer, as phototherapy carries an increased risk for cutaneous malignancy, especially in patients with a history of skin cancer.22,23 All patients also should be evaluated for their Fitzpatrick skin type, and the minimal erythema dose should be defined for those initiating UVB treatment. These classifications can be useful for the initial determination of treatment dose and the prevention of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). A careful drug history also should be taken before the initiation of phototherapy to avoid photosensitizing reactions. Thiazide diuretics and tetracyclines are 2 such examples of medications commonly associated with photosensitizing reactions.24

Fitzpatrick skin type and/or minimal erythema dose testing also are essential in determining the appropriate initial NB-UVB dose required for treatment initiation (Table 2). Patient response to the initial NB-UVB trial will determine the optimal dosage for subsequent maintenance treatments.

For patients unable or unwilling to commit to office-based or institution-based treatments, home NB-UVB is another therapeutic option. One study comparing patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who received home NB-UVB vs in-office treatment showed comparable psoriasis area and severity index scores and quality-of-life indices and no difference in the frequency of TRAE indices. It is important to note that patients who received home treatment had a significantly lower treatment burden (P≤.001) and greater treatment satisfaction than those receiving treatment in an office-based setting (P=.001).25

Assessment and Optimization of Phototherapy

After an appropriate starting dosage has been established, patients should be evaluated at each subsequent visit for the degree of treatment response. Excessive erythema (lasting more than 48 hours) or adverse effects, such as itching, stinging, or burning, are indications that the patient should have their dose adjusted back to the last dose without such adverse responses. Because tolerance to treatment develops over time, patients who miss a scheduled dose of NB-UVB phototherapy require their dose to be temporarily lowered. Targeted dosage of UVB phototherapy at a frequency of 2 to 3 times weekly is preferred over treatment 1 to 2 times weekly; however, consideration should be given toward patient preference.26 Dosing may be increased at a rate of 5% to 10% after each treatment, as tolerated, if there is no clearance of skin lesions with the original treatment dose. Patient skin type also is helpful in dictating the maximum phototherapy dose for each patient (Table 3).

Once a patient’s psoriatic lesions have cleared, the patient has the option to taper or indefinitely continue maintenance therapy. The established protocol for patients who choose to taper therapy is treatment twice weekly for 4 weeks, followed by once-weekly treatment for the second month. The maintenance dosage is held constant during the taper. For patients who prefer indefinite maintenance therapy, treatment is administered every 1 to 2 weeks, with a maintenance dosage that is approximately 25% lower than the original maintenance dosage.

Treatment Considerations

Efforts should be made to ensure that the long-term sequalae of phototherapy are minimized (Table 1). Development of cataracts is a recognized consequence of prolonged UVB exposure; therefore, eye protection is recommended during all UVB treatment sessions to reduce the risk for ocular toxicity. Although pregnancy is not a contraindication to phototherapy, except for PUVA, there is a dose-dependent degradation of folate with NB-UVB treatment, so folate supplementation (0.8 mg) is recommended during NB-UVB treatment to prevent development of neural tube defects in fetuses of patients who are pregnant or who may become pregnant.27

Although phototherapy carries the theoretical risk for photocarcinogenesis, multiple studies have shown no increased risk for malignancy with either NB-UVB or BB-UVB phototherapy.22,23 Regardless, patients who develop new-onset skin cancer while receiving any phototherapeutic treatment should discuss the potential risks and benefits of continued treatment with their physician. Providers should take extra caution prior to initiating treatment, especially in patients with a history of cutaneous malignancy. Because oral PUVA is a systemic therapy, it is associated with a greater risk for photocarcinogenesis than any other modality, particularly in fair-skinned individuals. Patients younger than 10 years; pregnant or nursing patients; and those with a history of lupus, xeroderma pigmentosum, or melanoma should not receive PUVA therapy because of their increased risk for photocarcinogenesis and TRAEs.

The decision to switch patients between different phototherapy modalities during treatment should be individualized to each patient based on factors such as disease severity, quality of life, and treatment burden. Other factors to consider include dosing frequency, treatment cost, and logistical factors, such as proximity to a treatment facility. Physicians should have a detailed discussion about the risks and benefits of continuing therapy for patients who develop new-onset skin cancer during phototherapy.

Final Thoughts

Phototherapy is an effective and safe treatment for patients with psoriasis who have localized and systemic disease. There are several treatment modalities that can be tailored to patient needs and preferences, such as home NB-UVB for patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo office-based treatments. Phototherapy has few absolute contraindications; however, relative contraindications to phototherapy exist. Patients with a history of skin cancer, photosensitivity disorders, and autoimmune diseases (eg, lupus) carry greater risks for adverse events, such as sun-related damage, cancer, and dysplasia. Because these conditions may preclude patients from pursuing phototherapy as a safe and effective approach to treating moderate to severe psoriasis, these patients should be considered for other therapies, such as biologic medications, which may carry a more favorable risk-benefit ratio given that individual’s background.

- Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205-212.

- Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1173-1179.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Efficacy of psoralen UV-A therapy vs. narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):11-21.

- Chen X, Yang M, Cheng Y, et al. Narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy versus broad-band ultraviolet B or psoralen-ultraviolet A photochemotherapy for psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD009481.

- Wong T, Hsu L, Liao W. Phototherapy in psoriasis: a review of mechanisms of action. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:6-12.

- Parrish JA, Jaenicke KF. Action spectrum for phototherapy of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1981;76:359-362.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- El-Mofty M, Mostafa WZ, Bosseila M, et al. A large scale analytical study on efficacy of different photo(chemo)therapeutic modalities in the treatment of psoriasis, vitiligo and mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:428-434.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 5. guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy and photochemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:114-135.

- Murase JE, Lee EE, Koo J. Effect of ethnicity on the risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer following long-term PUVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:1016-1021.

- Bruynzeel I, Bergman W, Hartevelt HM, et al. 'High single-dose' European PUVA regimen also causes an excess of non-melanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:49-55.

- Lindelöf B, Sigurgeirsson B, Tegner E, et al. PUVA and cancer risk: the Swedish follow-up study. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:108-112.

- Chern E, Yau D, Ho JC, et al. Positive effect of modified Goeckerman regimen on quality of life and psychosocial distress in moderate and severe psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:447-451.

- Harari M, Czarnowicki T, Fluss R, et al. Patients with early-onset psoriasis achieve better results following Dead Sea climatotherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:554-559.

- Wahl AK, Langeland E, Larsen MH, et al. Positive changes in self-management and disease severity following climate therapy in people with psoriasis. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2015;95:317-321.

- Bissonnette R, Zeng H, McLean DI, et al. Psoriatic plaques exhibit red autofluorescence that is due to protoporphyrin IX. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:586-591.

- Kleinpenning MM, Otero ME, van Erp PE, et al. Efficacy of blue light vs. red light in the treatment of psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:219-225.

- Weinstabl A, Hoff-Lesch S, Merk HF, et al. Prospective randomized study on the efficacy of blue light in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology. 2011;223:251-259.

- Huang YC, Chou CL, Chiang YY. Efficacy of pulsed dye laser plus topical tazarotene versus topical tazarotene alone in psoriatic nail disease: a single-blind, intrapatient left-to-right controlled study. Lasers Surg Med. 2013;45:102-107.

- Tawfik AA. Novel treatment of nail psoriasis using the intense pulsed light: a one-year follow-up study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:763-768.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):22-31.

- Osmancevic A, Gillstedt M, Wennberg AM, et al. The risk of skin cancer in psoriasis patients treated with UVB therapy. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2014;94:425-430.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368.

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:B1542.

- Almutawa F, Thalib L, Hekman D, et al. Efficacy of localized phototherapy and photodynamic therapy for psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:5-14.

- Zhang M, Goyert G, Lim HW. Folate and phototherapy: what should we inform our patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:958-964.

- Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205-212.

- Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1173-1179.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Efficacy of psoralen UV-A therapy vs. narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):11-21.

- Chen X, Yang M, Cheng Y, et al. Narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy versus broad-band ultraviolet B or psoralen-ultraviolet A photochemotherapy for psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD009481.

- Wong T, Hsu L, Liao W. Phototherapy in psoriasis: a review of mechanisms of action. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:6-12.

- Parrish JA, Jaenicke KF. Action spectrum for phototherapy of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1981;76:359-362.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- El-Mofty M, Mostafa WZ, Bosseila M, et al. A large scale analytical study on efficacy of different photo(chemo)therapeutic modalities in the treatment of psoriasis, vitiligo and mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:428-434.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 5. guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy and photochemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:114-135.

- Murase JE, Lee EE, Koo J. Effect of ethnicity on the risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer following long-term PUVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:1016-1021.

- Bruynzeel I, Bergman W, Hartevelt HM, et al. 'High single-dose' European PUVA regimen also causes an excess of non-melanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:49-55.

- Lindelöf B, Sigurgeirsson B, Tegner E, et al. PUVA and cancer risk: the Swedish follow-up study. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:108-112.

- Chern E, Yau D, Ho JC, et al. Positive effect of modified Goeckerman regimen on quality of life and psychosocial distress in moderate and severe psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:447-451.

- Harari M, Czarnowicki T, Fluss R, et al. Patients with early-onset psoriasis achieve better results following Dead Sea climatotherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:554-559.

- Wahl AK, Langeland E, Larsen MH, et al. Positive changes in self-management and disease severity following climate therapy in people with psoriasis. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2015;95:317-321.

- Bissonnette R, Zeng H, McLean DI, et al. Psoriatic plaques exhibit red autofluorescence that is due to protoporphyrin IX. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:586-591.

- Kleinpenning MM, Otero ME, van Erp PE, et al. Efficacy of blue light vs. red light in the treatment of psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:219-225.

- Weinstabl A, Hoff-Lesch S, Merk HF, et al. Prospective randomized study on the efficacy of blue light in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology. 2011;223:251-259.

- Huang YC, Chou CL, Chiang YY. Efficacy of pulsed dye laser plus topical tazarotene versus topical tazarotene alone in psoriatic nail disease: a single-blind, intrapatient left-to-right controlled study. Lasers Surg Med. 2013;45:102-107.

- Tawfik AA. Novel treatment of nail psoriasis using the intense pulsed light: a one-year follow-up study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:763-768.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):22-31.

- Osmancevic A, Gillstedt M, Wennberg AM, et al. The risk of skin cancer in psoriasis patients treated with UVB therapy. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2014;94:425-430.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368.

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:B1542.

- Almutawa F, Thalib L, Hekman D, et al. Efficacy of localized phototherapy and photodynamic therapy for psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:5-14.

- Zhang M, Goyert G, Lim HW. Folate and phototherapy: what should we inform our patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:958-964.

Practice Points

- Phototherapy should be considered as an effective and low-risk treatment of psoriasis.

- Narrowband UVB, broadband UVB, targeted phototherapy (excimer laser and excimer lamp), and oral psoralen plus UVA have all received a grade A level of recommendation for the treatment of psoriasis in adults.