User login

Evaluation of the Order SMARTT: An Initiative to Reduce Phlebotomy and Improve Sleep-Friendly Labs on General Medicine Services

Frequent daily laboratory testing for inpatients contributes to excessive costs,1 anemia,2 and unnecessary testing.3 The ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign recommends avoiding routine labs, like complete blood counts (CBCs) and basic metabolic panels (BMP), in the face of clinical and laboratory stability.4,5 Prior interventions have reduced unnecessary labs without adverse outcomes.6-8

In addition to lab frequency, hospitalized patients face suboptimal lab timing. Labs are often ordered as early as 4

METHODS

Setting

This study was conducted on the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) general medicine services, which consisted of a resident-covered service supervised by general medicine, subspecialist, or hospitalist attendings and a hospitalist service staffed by hospitalists and advanced practice providers.

Development of Order SMARTT

To inform intervention development, we surveyed providers about lab-ordering preferences with use of questions from a prior survey to provide a benchmark (Appendix Table 2).15 While reducing lab frequency was supported, the modal response for how frequently a stable patient should receive routine labs was every 48 hours (Appendix Table 2). Therefore, we hypothesized that labs ordered every 48 hours may be popular. Taking labs every 48 hours would not require an urgent 4

Physician Education

We created a 20-minute presentation on the harms of excessive labs and the benefits of sleep-friendly ordering. Instructional Order SMARTT posters were posted in clinician workrooms that emphasized forgoing labs on stable patients and using the “Order Sleep” shortcut when nonurgent labs were needed.

Labs Utilization Data

We used Epic Systems software (Verona, Wisconsin) and our institutional Tableau scorecard to obtain data on CBC and BMP ordering, patient census, and demographics for medical inpatients between July 1, 2017, and November 1, 2018.

Cost Analysis

Costs of lab tests (actual cost to our institution) were obtained from our institutional phlebotomy services’ estimates of direct variable labor and benefits costs and direct variable supplies cost.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed with SAS version 9.4 statistical software (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R version 3.6.2 (Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. Surveys were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and two-sample t tests for continuous variables. For lab ordering data, interrupted time series analyses (ITSA) were used to determine the changes in ordering practices with the implementation of the two interventions controlling for service lines (resident vs hospitalist service). ITSA enables examination of changes in lab ordering while controlling for time. The AUTOREG function in SAS was used to build the model and estimate final parameters. This function automatically tests for autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity, and estimates any autoregressive parameters required in the model. Our main model tested the association between our two separate interventions on ordering practices, controlling for service (hospitalist or resident).16

RESULTS

Of 125 residents, 82 (65.6%) attended the session and completed the survey. Attendance and response rate for hospitalists was 80% (16 of 20). Similar to a prior study, many residents (73.1%) reported they would be comfortable if patients received less daily laboratory testing (Appendix Table 2).

We reviewed data from 7,045 total patients over 50,951 total patient days between July1, 2017, and November 1, 2018 (Appendix Table 3).

Total Lab Draws

After accounting for total patient days, we saw 26.3% reduction on average in total lab draws per patient-day per week postintervention (4.68 before vs 3.45 after; difference, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.82-1.63; P < .05; Appendix Table 3). When total lab draws were stratified by service, we saw 28% reduction on average in total lab draws per patient-day per week on resident services (4.67 before vs 3.36 after; difference, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.88-1.74; P < .05) and 23.9% reduction on average in lab draws/patient-day per week on the hospitalist service (4.73 before vs 3.60 after; difference, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.61-1.64; P < .05; Appendix Table 3).

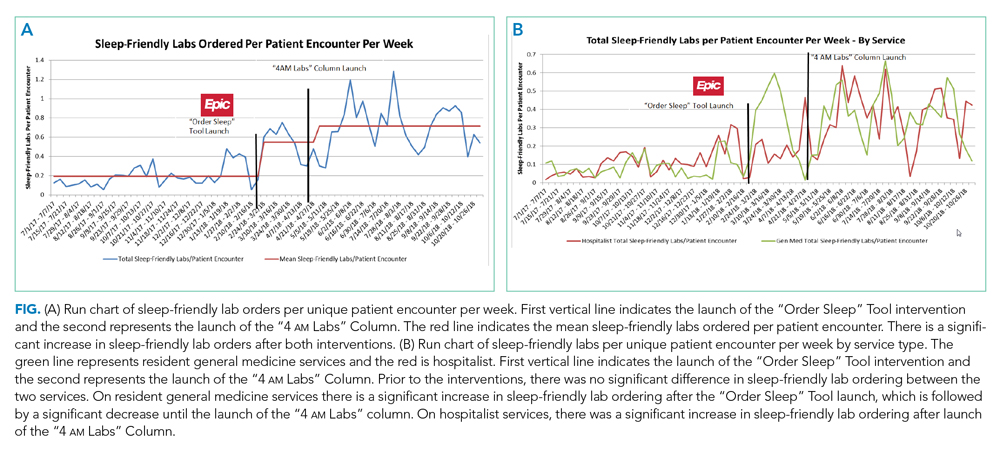

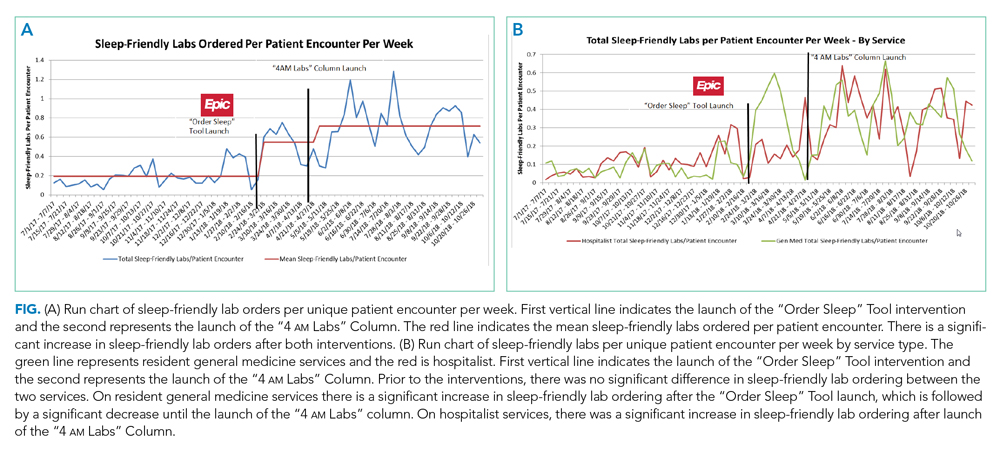

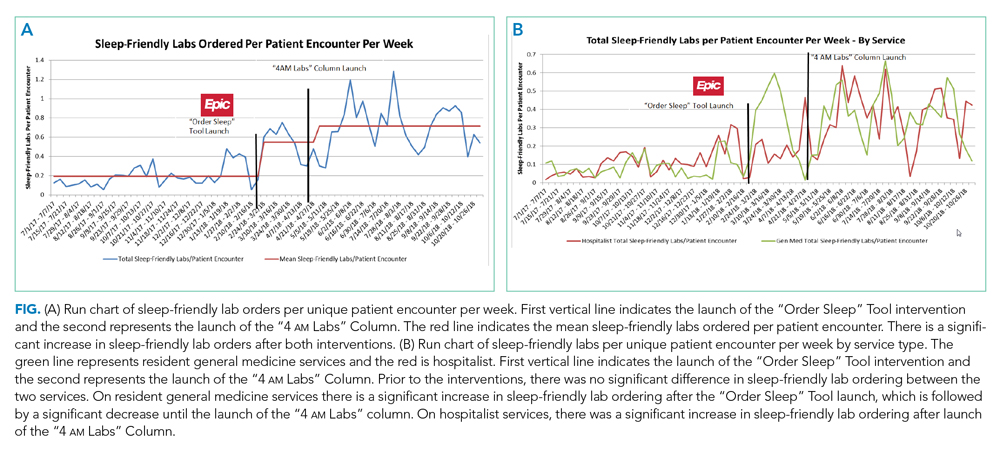

Sleep-Friendly Labs by Intervention

For patients with routine labs, the proportion of sleep-friendly labs drawn per patient-day increased from 6% preintervention to 21% postintervention (P < .001). ITSA demonstrated both interventions were associated with improving lab timing. There was a statistically significant increase in sleep-friendly labs ordered per patient encounter per week immediately after the launch of “Order Sleep” (intercept, 0.49; standard error (SE), 0.14; P = .001) and the “4

Sleep-Friendly Lab Orders by Service

Over the study period, there was no significant difference in total sleep-friendly labs ordered/month between resident and hospitalist services (84.88 vs 86.19; P = .95).

In ITSA, “Order Sleep” was associated with a statistically significant immediate increase in sleep-friendly lab orders per patient encounter per week on resident services (intercept, 1.03; SE, 0.29; P < .001). However, this initial increase was followed by a decrease over time in sleep-friendly lab orders per week (slope change, –0.1; SE, 0.04; P = .02; Table, Figure B). There was no statistically significant change observed on the hospitalist service with “Order Sleep.”

In contrast, the “4

Cost Savings

Using an estimated cost of $7.70 for CBCs and $8.01 for BMPs from our laboratory, our intervention saved an estimated $60,278 in lab costs alone over the 16-month study period (Appendix Table 4).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a multicomponent intervention using EHR tools can both reduce frequency and optimize timing of routine lab ordering. Our project had two interventions implemented at two different times: First, an “Order Sleep” shortcut was introduced to select sleep-friendly lab timing, including a 6

While the “Order Sleep” tool was initially associated with significant increases in sleep-friendly orders on resident services, this change was not sustained. This could have been caused by the short-lived effect of education more than sustained adoption of the tool. In contrast, the “4

The “4

While other institutions have attempted to shift lab-timing by altering phlebotomy workflows10 or via conscious decision-making on rounds,9 our study differs in several ways. We avoided default options and allowed clinicians to select sleep-friendly labs to promote buy-in. It is sometimes necessary to order 4

Our study had several limitations. First, this was a single center study on adult medicine services, which limits generalizability. Although we considered surgical services, their early rounds made deviations from 4

In conclusion, a multicomponent intervention using EHR tools can reduce inpatient daily lab frequency and optimize lab timing to help promote patient sleep.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The University of Chicago Center for Healthcare Delivery Science and Innovation for sponsoring their annual Choosing Wisely Challenge, which allowed for access to institutional support and resources for this study. We would also like to thank Mary Kate Springman, MHA, and John Fahrenbach, PhD, for their assistance with this project. Dr Tapaskar also received mentorship through the Future Leader Program for the High Value Practice Academic Alliance.

1. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0094.x

3. Korenstein D, Husain S, Gennarelli RL, White C, Masciale JN, Roman BR. Impact of clinical specialty on attitudes regarding overuse of inpatient laboratory testing. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):844-847. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2978

4. Choosing Wisely. 2020. Accessed January 10, 2020. http://www.choosingwisely.org/getting-started/

5. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063

6. Stuebing EA, Miner TJ. Surgical vampires and rising health care expenditure: reducing the cost of daily phlebotomy. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):524-527. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.103

7. Attali M, Barel Y, Somin M, et al. A cost-effective method for reducing the volume of laboratory tests in a university-associated teaching hospital. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(5):787-794.

8. Vidyarthi AR, Hamill T, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Changing resident test ordering behavior: a multilevel intervention to decrease laboratory utilization at an academic medical center. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):81-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860613517502

9. Krafft CA, Biondi EA, Leonard MS, et al. Ending the 4 AM Blood Draw. Presented at: American Academy of Pediatrics Experience; October 25, 2015, Washington, DC. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://aap.confex.com/aap/2015/webprogrampress/Paper31640.html

10. Ramarajan V, Chima HS, Young L. Implementation of later morning specimen draws to improve patient health and satisfaction. Lab Med. 2016;47(1):e1-e4. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmv013

11. Delaney LJ, Van Haren F, Lopez V. Sleeping on a problem: the impact of sleep disturbance on intensive care patients - a clinical review. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-015-0043-2

12. Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(3):163-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002

13. Ho A, Raja B, Waldhorn R, Baez V, Mohammed I. New onset of insomnia in hospitalized patients in general medical wards: incidence, causes, and resolution rate. J Community Hosp Int. 2017;7(5):309-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2017.1374108

14. Arora VM, Machado N, Anderson SL, et al. Effectiveness of SIESTA on objective and subjective metrics of nighttime hospital sleep disruptors. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):38-41. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3091

15. Roman BR, Yang A, Masciale J, Korenstein D. Association of Attitudes Regarding Overuse of Inpatient Laboratory Testing With Health Care Provider Type. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1205-1207. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1634

16. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38-S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002

Frequent daily laboratory testing for inpatients contributes to excessive costs,1 anemia,2 and unnecessary testing.3 The ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign recommends avoiding routine labs, like complete blood counts (CBCs) and basic metabolic panels (BMP), in the face of clinical and laboratory stability.4,5 Prior interventions have reduced unnecessary labs without adverse outcomes.6-8

In addition to lab frequency, hospitalized patients face suboptimal lab timing. Labs are often ordered as early as 4

METHODS

Setting

This study was conducted on the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) general medicine services, which consisted of a resident-covered service supervised by general medicine, subspecialist, or hospitalist attendings and a hospitalist service staffed by hospitalists and advanced practice providers.

Development of Order SMARTT

To inform intervention development, we surveyed providers about lab-ordering preferences with use of questions from a prior survey to provide a benchmark (Appendix Table 2).15 While reducing lab frequency was supported, the modal response for how frequently a stable patient should receive routine labs was every 48 hours (Appendix Table 2). Therefore, we hypothesized that labs ordered every 48 hours may be popular. Taking labs every 48 hours would not require an urgent 4

Physician Education

We created a 20-minute presentation on the harms of excessive labs and the benefits of sleep-friendly ordering. Instructional Order SMARTT posters were posted in clinician workrooms that emphasized forgoing labs on stable patients and using the “Order Sleep” shortcut when nonurgent labs were needed.

Labs Utilization Data

We used Epic Systems software (Verona, Wisconsin) and our institutional Tableau scorecard to obtain data on CBC and BMP ordering, patient census, and demographics for medical inpatients between July 1, 2017, and November 1, 2018.

Cost Analysis

Costs of lab tests (actual cost to our institution) were obtained from our institutional phlebotomy services’ estimates of direct variable labor and benefits costs and direct variable supplies cost.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed with SAS version 9.4 statistical software (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R version 3.6.2 (Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. Surveys were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and two-sample t tests for continuous variables. For lab ordering data, interrupted time series analyses (ITSA) were used to determine the changes in ordering practices with the implementation of the two interventions controlling for service lines (resident vs hospitalist service). ITSA enables examination of changes in lab ordering while controlling for time. The AUTOREG function in SAS was used to build the model and estimate final parameters. This function automatically tests for autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity, and estimates any autoregressive parameters required in the model. Our main model tested the association between our two separate interventions on ordering practices, controlling for service (hospitalist or resident).16

RESULTS

Of 125 residents, 82 (65.6%) attended the session and completed the survey. Attendance and response rate for hospitalists was 80% (16 of 20). Similar to a prior study, many residents (73.1%) reported they would be comfortable if patients received less daily laboratory testing (Appendix Table 2).

We reviewed data from 7,045 total patients over 50,951 total patient days between July1, 2017, and November 1, 2018 (Appendix Table 3).

Total Lab Draws

After accounting for total patient days, we saw 26.3% reduction on average in total lab draws per patient-day per week postintervention (4.68 before vs 3.45 after; difference, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.82-1.63; P < .05; Appendix Table 3). When total lab draws were stratified by service, we saw 28% reduction on average in total lab draws per patient-day per week on resident services (4.67 before vs 3.36 after; difference, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.88-1.74; P < .05) and 23.9% reduction on average in lab draws/patient-day per week on the hospitalist service (4.73 before vs 3.60 after; difference, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.61-1.64; P < .05; Appendix Table 3).

Sleep-Friendly Labs by Intervention

For patients with routine labs, the proportion of sleep-friendly labs drawn per patient-day increased from 6% preintervention to 21% postintervention (P < .001). ITSA demonstrated both interventions were associated with improving lab timing. There was a statistically significant increase in sleep-friendly labs ordered per patient encounter per week immediately after the launch of “Order Sleep” (intercept, 0.49; standard error (SE), 0.14; P = .001) and the “4

Sleep-Friendly Lab Orders by Service

Over the study period, there was no significant difference in total sleep-friendly labs ordered/month between resident and hospitalist services (84.88 vs 86.19; P = .95).

In ITSA, “Order Sleep” was associated with a statistically significant immediate increase in sleep-friendly lab orders per patient encounter per week on resident services (intercept, 1.03; SE, 0.29; P < .001). However, this initial increase was followed by a decrease over time in sleep-friendly lab orders per week (slope change, –0.1; SE, 0.04; P = .02; Table, Figure B). There was no statistically significant change observed on the hospitalist service with “Order Sleep.”

In contrast, the “4

Cost Savings

Using an estimated cost of $7.70 for CBCs and $8.01 for BMPs from our laboratory, our intervention saved an estimated $60,278 in lab costs alone over the 16-month study period (Appendix Table 4).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a multicomponent intervention using EHR tools can both reduce frequency and optimize timing of routine lab ordering. Our project had two interventions implemented at two different times: First, an “Order Sleep” shortcut was introduced to select sleep-friendly lab timing, including a 6

While the “Order Sleep” tool was initially associated with significant increases in sleep-friendly orders on resident services, this change was not sustained. This could have been caused by the short-lived effect of education more than sustained adoption of the tool. In contrast, the “4

The “4

While other institutions have attempted to shift lab-timing by altering phlebotomy workflows10 or via conscious decision-making on rounds,9 our study differs in several ways. We avoided default options and allowed clinicians to select sleep-friendly labs to promote buy-in. It is sometimes necessary to order 4

Our study had several limitations. First, this was a single center study on adult medicine services, which limits generalizability. Although we considered surgical services, their early rounds made deviations from 4

In conclusion, a multicomponent intervention using EHR tools can reduce inpatient daily lab frequency and optimize lab timing to help promote patient sleep.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The University of Chicago Center for Healthcare Delivery Science and Innovation for sponsoring their annual Choosing Wisely Challenge, which allowed for access to institutional support and resources for this study. We would also like to thank Mary Kate Springman, MHA, and John Fahrenbach, PhD, for their assistance with this project. Dr Tapaskar also received mentorship through the Future Leader Program for the High Value Practice Academic Alliance.

Frequent daily laboratory testing for inpatients contributes to excessive costs,1 anemia,2 and unnecessary testing.3 The ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign recommends avoiding routine labs, like complete blood counts (CBCs) and basic metabolic panels (BMP), in the face of clinical and laboratory stability.4,5 Prior interventions have reduced unnecessary labs without adverse outcomes.6-8

In addition to lab frequency, hospitalized patients face suboptimal lab timing. Labs are often ordered as early as 4

METHODS

Setting

This study was conducted on the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) general medicine services, which consisted of a resident-covered service supervised by general medicine, subspecialist, or hospitalist attendings and a hospitalist service staffed by hospitalists and advanced practice providers.

Development of Order SMARTT

To inform intervention development, we surveyed providers about lab-ordering preferences with use of questions from a prior survey to provide a benchmark (Appendix Table 2).15 While reducing lab frequency was supported, the modal response for how frequently a stable patient should receive routine labs was every 48 hours (Appendix Table 2). Therefore, we hypothesized that labs ordered every 48 hours may be popular. Taking labs every 48 hours would not require an urgent 4

Physician Education

We created a 20-minute presentation on the harms of excessive labs and the benefits of sleep-friendly ordering. Instructional Order SMARTT posters were posted in clinician workrooms that emphasized forgoing labs on stable patients and using the “Order Sleep” shortcut when nonurgent labs were needed.

Labs Utilization Data

We used Epic Systems software (Verona, Wisconsin) and our institutional Tableau scorecard to obtain data on CBC and BMP ordering, patient census, and demographics for medical inpatients between July 1, 2017, and November 1, 2018.

Cost Analysis

Costs of lab tests (actual cost to our institution) were obtained from our institutional phlebotomy services’ estimates of direct variable labor and benefits costs and direct variable supplies cost.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed with SAS version 9.4 statistical software (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R version 3.6.2 (Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. Surveys were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and two-sample t tests for continuous variables. For lab ordering data, interrupted time series analyses (ITSA) were used to determine the changes in ordering practices with the implementation of the two interventions controlling for service lines (resident vs hospitalist service). ITSA enables examination of changes in lab ordering while controlling for time. The AUTOREG function in SAS was used to build the model and estimate final parameters. This function automatically tests for autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity, and estimates any autoregressive parameters required in the model. Our main model tested the association between our two separate interventions on ordering practices, controlling for service (hospitalist or resident).16

RESULTS

Of 125 residents, 82 (65.6%) attended the session and completed the survey. Attendance and response rate for hospitalists was 80% (16 of 20). Similar to a prior study, many residents (73.1%) reported they would be comfortable if patients received less daily laboratory testing (Appendix Table 2).

We reviewed data from 7,045 total patients over 50,951 total patient days between July1, 2017, and November 1, 2018 (Appendix Table 3).

Total Lab Draws

After accounting for total patient days, we saw 26.3% reduction on average in total lab draws per patient-day per week postintervention (4.68 before vs 3.45 after; difference, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.82-1.63; P < .05; Appendix Table 3). When total lab draws were stratified by service, we saw 28% reduction on average in total lab draws per patient-day per week on resident services (4.67 before vs 3.36 after; difference, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.88-1.74; P < .05) and 23.9% reduction on average in lab draws/patient-day per week on the hospitalist service (4.73 before vs 3.60 after; difference, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.61-1.64; P < .05; Appendix Table 3).

Sleep-Friendly Labs by Intervention

For patients with routine labs, the proportion of sleep-friendly labs drawn per patient-day increased from 6% preintervention to 21% postintervention (P < .001). ITSA demonstrated both interventions were associated with improving lab timing. There was a statistically significant increase in sleep-friendly labs ordered per patient encounter per week immediately after the launch of “Order Sleep” (intercept, 0.49; standard error (SE), 0.14; P = .001) and the “4

Sleep-Friendly Lab Orders by Service

Over the study period, there was no significant difference in total sleep-friendly labs ordered/month between resident and hospitalist services (84.88 vs 86.19; P = .95).

In ITSA, “Order Sleep” was associated with a statistically significant immediate increase in sleep-friendly lab orders per patient encounter per week on resident services (intercept, 1.03; SE, 0.29; P < .001). However, this initial increase was followed by a decrease over time in sleep-friendly lab orders per week (slope change, –0.1; SE, 0.04; P = .02; Table, Figure B). There was no statistically significant change observed on the hospitalist service with “Order Sleep.”

In contrast, the “4

Cost Savings

Using an estimated cost of $7.70 for CBCs and $8.01 for BMPs from our laboratory, our intervention saved an estimated $60,278 in lab costs alone over the 16-month study period (Appendix Table 4).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a multicomponent intervention using EHR tools can both reduce frequency and optimize timing of routine lab ordering. Our project had two interventions implemented at two different times: First, an “Order Sleep” shortcut was introduced to select sleep-friendly lab timing, including a 6

While the “Order Sleep” tool was initially associated with significant increases in sleep-friendly orders on resident services, this change was not sustained. This could have been caused by the short-lived effect of education more than sustained adoption of the tool. In contrast, the “4

The “4

While other institutions have attempted to shift lab-timing by altering phlebotomy workflows10 or via conscious decision-making on rounds,9 our study differs in several ways. We avoided default options and allowed clinicians to select sleep-friendly labs to promote buy-in. It is sometimes necessary to order 4

Our study had several limitations. First, this was a single center study on adult medicine services, which limits generalizability. Although we considered surgical services, their early rounds made deviations from 4

In conclusion, a multicomponent intervention using EHR tools can reduce inpatient daily lab frequency and optimize lab timing to help promote patient sleep.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The University of Chicago Center for Healthcare Delivery Science and Innovation for sponsoring their annual Choosing Wisely Challenge, which allowed for access to institutional support and resources for this study. We would also like to thank Mary Kate Springman, MHA, and John Fahrenbach, PhD, for their assistance with this project. Dr Tapaskar also received mentorship through the Future Leader Program for the High Value Practice Academic Alliance.

1. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0094.x

3. Korenstein D, Husain S, Gennarelli RL, White C, Masciale JN, Roman BR. Impact of clinical specialty on attitudes regarding overuse of inpatient laboratory testing. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):844-847. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2978

4. Choosing Wisely. 2020. Accessed January 10, 2020. http://www.choosingwisely.org/getting-started/

5. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063

6. Stuebing EA, Miner TJ. Surgical vampires and rising health care expenditure: reducing the cost of daily phlebotomy. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):524-527. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.103

7. Attali M, Barel Y, Somin M, et al. A cost-effective method for reducing the volume of laboratory tests in a university-associated teaching hospital. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(5):787-794.

8. Vidyarthi AR, Hamill T, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Changing resident test ordering behavior: a multilevel intervention to decrease laboratory utilization at an academic medical center. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):81-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860613517502

9. Krafft CA, Biondi EA, Leonard MS, et al. Ending the 4 AM Blood Draw. Presented at: American Academy of Pediatrics Experience; October 25, 2015, Washington, DC. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://aap.confex.com/aap/2015/webprogrampress/Paper31640.html

10. Ramarajan V, Chima HS, Young L. Implementation of later morning specimen draws to improve patient health and satisfaction. Lab Med. 2016;47(1):e1-e4. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmv013

11. Delaney LJ, Van Haren F, Lopez V. Sleeping on a problem: the impact of sleep disturbance on intensive care patients - a clinical review. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-015-0043-2

12. Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(3):163-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002

13. Ho A, Raja B, Waldhorn R, Baez V, Mohammed I. New onset of insomnia in hospitalized patients in general medical wards: incidence, causes, and resolution rate. J Community Hosp Int. 2017;7(5):309-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2017.1374108

14. Arora VM, Machado N, Anderson SL, et al. Effectiveness of SIESTA on objective and subjective metrics of nighttime hospital sleep disruptors. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):38-41. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3091

15. Roman BR, Yang A, Masciale J, Korenstein D. Association of Attitudes Regarding Overuse of Inpatient Laboratory Testing With Health Care Provider Type. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1205-1207. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1634

16. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38-S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002

1. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0094.x

3. Korenstein D, Husain S, Gennarelli RL, White C, Masciale JN, Roman BR. Impact of clinical specialty on attitudes regarding overuse of inpatient laboratory testing. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):844-847. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2978

4. Choosing Wisely. 2020. Accessed January 10, 2020. http://www.choosingwisely.org/getting-started/

5. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063

6. Stuebing EA, Miner TJ. Surgical vampires and rising health care expenditure: reducing the cost of daily phlebotomy. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):524-527. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.103

7. Attali M, Barel Y, Somin M, et al. A cost-effective method for reducing the volume of laboratory tests in a university-associated teaching hospital. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(5):787-794.

8. Vidyarthi AR, Hamill T, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Changing resident test ordering behavior: a multilevel intervention to decrease laboratory utilization at an academic medical center. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):81-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860613517502

9. Krafft CA, Biondi EA, Leonard MS, et al. Ending the 4 AM Blood Draw. Presented at: American Academy of Pediatrics Experience; October 25, 2015, Washington, DC. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://aap.confex.com/aap/2015/webprogrampress/Paper31640.html

10. Ramarajan V, Chima HS, Young L. Implementation of later morning specimen draws to improve patient health and satisfaction. Lab Med. 2016;47(1):e1-e4. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmv013

11. Delaney LJ, Van Haren F, Lopez V. Sleeping on a problem: the impact of sleep disturbance on intensive care patients - a clinical review. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-015-0043-2

12. Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(3):163-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002

13. Ho A, Raja B, Waldhorn R, Baez V, Mohammed I. New onset of insomnia in hospitalized patients in general medical wards: incidence, causes, and resolution rate. J Community Hosp Int. 2017;7(5):309-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2017.1374108

14. Arora VM, Machado N, Anderson SL, et al. Effectiveness of SIESTA on objective and subjective metrics of nighttime hospital sleep disruptors. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):38-41. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3091

15. Roman BR, Yang A, Masciale J, Korenstein D. Association of Attitudes Regarding Overuse of Inpatient Laboratory Testing With Health Care Provider Type. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1205-1207. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1634

16. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38-S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine