User login

A Rare Association in Down Syndrome: Milialike Idiopathic Calcinosis Cutis and Palpebral Syringoma

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

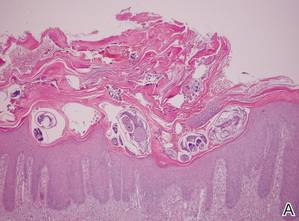

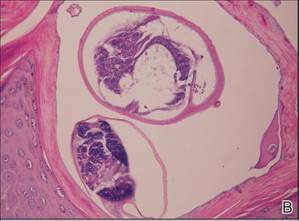

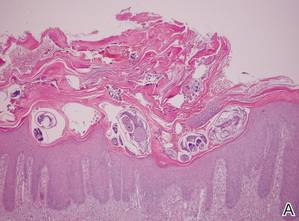

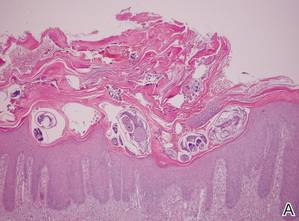

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

Practice Points

- Down syndrome is associated with rare dermatological disorders and an increased prevalence of common dermatoses.

- It is important to differentiate milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis from other dermatological diseases using histopathology and dermoscopy.

In Vivo Confocal Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Onychomycosis

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is a common nail disease that frequently is caused by dermatophytes and is diagnosed by direct microscopy. Conventional diagnostic methods are often time consuming and can produce false-positive or false-negative results. We report a case of onychomycosis diagnosed by confocal microscopy and confirmed with routine potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination and fungal culture. Confocal microscopy is a reliable, practical, and noninvasive technique in the diagnosis of onychomycosis.

A 46-year-old woman presented with yellow-brown discoloration and dystrophy of the toenails (Figure 1) that had become worse over a 5-year period. She was otherwise healthy and had no other dermatologic problems. Examination revealed yellow-brown discoloration, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis of the toenails. Clinically, a diagnosis of onychomycosis was made. Potassium hydroxide examination of a scraping from the subungual region showed fungal elements. Trichophyton rubrum on Sabouraud dextrose agar was determined.

|

We performed both in vivo and in vitro confocal laser scanning microscopic examination of the nail of the right great toe (Figure 2). For the diagnosis of onychomycosis in our case, we used a multilaser reflectance confocal microscope (RCM) with a wavelength of 786 nm. In vivo confocal microscopy of the nail revealed branching hyphae just below the surface of the nail plate. Hyphae were seen as refractile, bright, linear structures along the laminates of the nail.

Onychomycosis is a common condition affecting 5.5% of the population worldwide and representing 20% to 40% of all onychopathies and approximately 30% of cutaneous mycotic infections.1,2 There are many methods available to confirm the clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis by detecting the causative organisms. Direct microscopic examination of the scraping with a KOH culture, histopathologic assessment with periodic acid–Schiff staining, immunofluorescence analysis with calcofluor white staining, enzyme analysis, and polymerase chain reaction can be used for diagnosis of fungal infections. The most frequently used diagnostic method for onychomycosis is KOH examination of the scraping; however, fungal culture and histopathologic examination also can be used in cases having diagnostic difficulties.1,3,4 There are many studies comparing the efficacies of these methods in the literature.5-9

The causative fungal agent should be determined with at least 1 laboratory method due to the high cost, long duration, and serious potential adverse effects of systemic antifungal treatment. Direct microscopic examination with KOH in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is simple, fast, and inexpensive. However, inadequate material, using crystallized KOH for hydrolysis, insufficient or too much hydrolysis of scrapings, inappropriate staining, and not scanning all areas in the microscopy produce false-negative results. Similarly, secondary contamination of hair, cotton, yarn, or air bubbles mimicking fungal structures can cause false-positive results.9,10

Fungal culture is another diagnostic method that is accepted as the gold standard for diagnosis of onychomycosis.9 However, fungal cultures were positive in only 43% to 50% of all cases of onychomycosis that were diagnosed with other methods,11,12 which may be due to the loss of viability and ability of the fungi to grow in culture media during the transport. A major advantage of fungal culture is that the fungal agent can be classified as dermatophyte, nondermatophyte, mold, or yeast. However, culture does determine if the growing fungi is contamination or the real pathogen. Moreover, it is necessary to wait 3 to 4 weeks for culture results. For nondermatophyte fungi this time may be much longer.12

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging method that allows optical en face sectioning of the living tissue with high resolution. Currently, RCM has a wide range of applications, such as the evaluation of both benign and malignant skin lesions in clinical dermatology.13

In vivo RCM was used first by Hongcharu et al.14 The diagnoses of onychomycosis and fungal hyphae were shown both in vivo and in vitro.14 The sensitivity and specificity of confocal examination in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is not known yet. Large clinical trials are needed to assess the sensitivity and specificity of this method in diagnosing fungal infections.

Onychomycosis is a contagious infectious disease characterized by hyphae proliferation in the nail plate. Definitive diagnosis is necessary before treatment because onychomycosis can be mistaken for many infectious or noninfectious skin diseases with nail involvement. Conventional methods are time consuming, laborious, and less reliable. Instead of high-cost procedures, in vivo confocal microscopic examination can be a rapid and reliable diagnostic method for onychomycosis in the near future.

1. Singal A, Khanna D. Onychomycosis: diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:659-672.

2. Kaur R, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. Onychomycosis—epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:108-116.

3. Richardson MD. Diagnosis and pathogenesis of dermatophyte infections. Br J Clin Pract Suppl. 1990;71:98-102.

4. Jensen RH, Arendrup MC. Molecular diagnosis of dermato-phyte infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:126-134.

5. Weinberg JM, Koestenblatt EK, Tutrone WD, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:193-197.

6. Gianni C, Morelli V, Cerri A, et al. Usefulness of histological examination for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Dermatology. 2001;202:283-288.

7. Machler BC, Kirsner RS, Elgart GW. Routine histologic examination for the diagnosis of onychomycosis: an evaluation of sensitivity and specificity. Cutis. 1998;61:217-219.

8. Wilsmann-Theis D, Sareika F, Bieber T, et al. New reasons for histopathological nail-clipping examination in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:235-237.

9. Reisberger EM, Abels C, Landthaler M, et al. Histopathological diagnosis of onychomycosis by periodic acid-Schiff-stained nail clippings. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:749-754.

10. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Collection of fungi samples from nails: comparative study of curettage and drilling techniques. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:182-185.

11. Daniel CR 3rd, Elewski BE. The diagnosis of nail fungus infection revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1162-1164.

12. Borkowski P, Williams M, Holewinski J, et al. Onychomycosis: an analysis of 50 cases and a comparison of diagnostic techniques. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:351-355.

13. Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM, et al. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin II: advances in instrumentation and comparison with histology. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:293-303.

14. Hongcharu W, Dwyer P, Gonzalez S, et al. Confirmation of onychomycosis by in vivo confocal microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):214-216.

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is a common nail disease that frequently is caused by dermatophytes and is diagnosed by direct microscopy. Conventional diagnostic methods are often time consuming and can produce false-positive or false-negative results. We report a case of onychomycosis diagnosed by confocal microscopy and confirmed with routine potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination and fungal culture. Confocal microscopy is a reliable, practical, and noninvasive technique in the diagnosis of onychomycosis.

A 46-year-old woman presented with yellow-brown discoloration and dystrophy of the toenails (Figure 1) that had become worse over a 5-year period. She was otherwise healthy and had no other dermatologic problems. Examination revealed yellow-brown discoloration, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis of the toenails. Clinically, a diagnosis of onychomycosis was made. Potassium hydroxide examination of a scraping from the subungual region showed fungal elements. Trichophyton rubrum on Sabouraud dextrose agar was determined.

|

We performed both in vivo and in vitro confocal laser scanning microscopic examination of the nail of the right great toe (Figure 2). For the diagnosis of onychomycosis in our case, we used a multilaser reflectance confocal microscope (RCM) with a wavelength of 786 nm. In vivo confocal microscopy of the nail revealed branching hyphae just below the surface of the nail plate. Hyphae were seen as refractile, bright, linear structures along the laminates of the nail.

Onychomycosis is a common condition affecting 5.5% of the population worldwide and representing 20% to 40% of all onychopathies and approximately 30% of cutaneous mycotic infections.1,2 There are many methods available to confirm the clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis by detecting the causative organisms. Direct microscopic examination of the scraping with a KOH culture, histopathologic assessment with periodic acid–Schiff staining, immunofluorescence analysis with calcofluor white staining, enzyme analysis, and polymerase chain reaction can be used for diagnosis of fungal infections. The most frequently used diagnostic method for onychomycosis is KOH examination of the scraping; however, fungal culture and histopathologic examination also can be used in cases having diagnostic difficulties.1,3,4 There are many studies comparing the efficacies of these methods in the literature.5-9

The causative fungal agent should be determined with at least 1 laboratory method due to the high cost, long duration, and serious potential adverse effects of systemic antifungal treatment. Direct microscopic examination with KOH in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is simple, fast, and inexpensive. However, inadequate material, using crystallized KOH for hydrolysis, insufficient or too much hydrolysis of scrapings, inappropriate staining, and not scanning all areas in the microscopy produce false-negative results. Similarly, secondary contamination of hair, cotton, yarn, or air bubbles mimicking fungal structures can cause false-positive results.9,10

Fungal culture is another diagnostic method that is accepted as the gold standard for diagnosis of onychomycosis.9 However, fungal cultures were positive in only 43% to 50% of all cases of onychomycosis that were diagnosed with other methods,11,12 which may be due to the loss of viability and ability of the fungi to grow in culture media during the transport. A major advantage of fungal culture is that the fungal agent can be classified as dermatophyte, nondermatophyte, mold, or yeast. However, culture does determine if the growing fungi is contamination or the real pathogen. Moreover, it is necessary to wait 3 to 4 weeks for culture results. For nondermatophyte fungi this time may be much longer.12

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging method that allows optical en face sectioning of the living tissue with high resolution. Currently, RCM has a wide range of applications, such as the evaluation of both benign and malignant skin lesions in clinical dermatology.13

In vivo RCM was used first by Hongcharu et al.14 The diagnoses of onychomycosis and fungal hyphae were shown both in vivo and in vitro.14 The sensitivity and specificity of confocal examination in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is not known yet. Large clinical trials are needed to assess the sensitivity and specificity of this method in diagnosing fungal infections.

Onychomycosis is a contagious infectious disease characterized by hyphae proliferation in the nail plate. Definitive diagnosis is necessary before treatment because onychomycosis can be mistaken for many infectious or noninfectious skin diseases with nail involvement. Conventional methods are time consuming, laborious, and less reliable. Instead of high-cost procedures, in vivo confocal microscopic examination can be a rapid and reliable diagnostic method for onychomycosis in the near future.

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is a common nail disease that frequently is caused by dermatophytes and is diagnosed by direct microscopy. Conventional diagnostic methods are often time consuming and can produce false-positive or false-negative results. We report a case of onychomycosis diagnosed by confocal microscopy and confirmed with routine potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination and fungal culture. Confocal microscopy is a reliable, practical, and noninvasive technique in the diagnosis of onychomycosis.

A 46-year-old woman presented with yellow-brown discoloration and dystrophy of the toenails (Figure 1) that had become worse over a 5-year period. She was otherwise healthy and had no other dermatologic problems. Examination revealed yellow-brown discoloration, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis of the toenails. Clinically, a diagnosis of onychomycosis was made. Potassium hydroxide examination of a scraping from the subungual region showed fungal elements. Trichophyton rubrum on Sabouraud dextrose agar was determined.

|

We performed both in vivo and in vitro confocal laser scanning microscopic examination of the nail of the right great toe (Figure 2). For the diagnosis of onychomycosis in our case, we used a multilaser reflectance confocal microscope (RCM) with a wavelength of 786 nm. In vivo confocal microscopy of the nail revealed branching hyphae just below the surface of the nail plate. Hyphae were seen as refractile, bright, linear structures along the laminates of the nail.

Onychomycosis is a common condition affecting 5.5% of the population worldwide and representing 20% to 40% of all onychopathies and approximately 30% of cutaneous mycotic infections.1,2 There are many methods available to confirm the clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis by detecting the causative organisms. Direct microscopic examination of the scraping with a KOH culture, histopathologic assessment with periodic acid–Schiff staining, immunofluorescence analysis with calcofluor white staining, enzyme analysis, and polymerase chain reaction can be used for diagnosis of fungal infections. The most frequently used diagnostic method for onychomycosis is KOH examination of the scraping; however, fungal culture and histopathologic examination also can be used in cases having diagnostic difficulties.1,3,4 There are many studies comparing the efficacies of these methods in the literature.5-9

The causative fungal agent should be determined with at least 1 laboratory method due to the high cost, long duration, and serious potential adverse effects of systemic antifungal treatment. Direct microscopic examination with KOH in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is simple, fast, and inexpensive. However, inadequate material, using crystallized KOH for hydrolysis, insufficient or too much hydrolysis of scrapings, inappropriate staining, and not scanning all areas in the microscopy produce false-negative results. Similarly, secondary contamination of hair, cotton, yarn, or air bubbles mimicking fungal structures can cause false-positive results.9,10

Fungal culture is another diagnostic method that is accepted as the gold standard for diagnosis of onychomycosis.9 However, fungal cultures were positive in only 43% to 50% of all cases of onychomycosis that were diagnosed with other methods,11,12 which may be due to the loss of viability and ability of the fungi to grow in culture media during the transport. A major advantage of fungal culture is that the fungal agent can be classified as dermatophyte, nondermatophyte, mold, or yeast. However, culture does determine if the growing fungi is contamination or the real pathogen. Moreover, it is necessary to wait 3 to 4 weeks for culture results. For nondermatophyte fungi this time may be much longer.12

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging method that allows optical en face sectioning of the living tissue with high resolution. Currently, RCM has a wide range of applications, such as the evaluation of both benign and malignant skin lesions in clinical dermatology.13

In vivo RCM was used first by Hongcharu et al.14 The diagnoses of onychomycosis and fungal hyphae were shown both in vivo and in vitro.14 The sensitivity and specificity of confocal examination in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is not known yet. Large clinical trials are needed to assess the sensitivity and specificity of this method in diagnosing fungal infections.

Onychomycosis is a contagious infectious disease characterized by hyphae proliferation in the nail plate. Definitive diagnosis is necessary before treatment because onychomycosis can be mistaken for many infectious or noninfectious skin diseases with nail involvement. Conventional methods are time consuming, laborious, and less reliable. Instead of high-cost procedures, in vivo confocal microscopic examination can be a rapid and reliable diagnostic method for onychomycosis in the near future.

1. Singal A, Khanna D. Onychomycosis: diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:659-672.

2. Kaur R, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. Onychomycosis—epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:108-116.

3. Richardson MD. Diagnosis and pathogenesis of dermatophyte infections. Br J Clin Pract Suppl. 1990;71:98-102.

4. Jensen RH, Arendrup MC. Molecular diagnosis of dermato-phyte infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:126-134.

5. Weinberg JM, Koestenblatt EK, Tutrone WD, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:193-197.

6. Gianni C, Morelli V, Cerri A, et al. Usefulness of histological examination for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Dermatology. 2001;202:283-288.

7. Machler BC, Kirsner RS, Elgart GW. Routine histologic examination for the diagnosis of onychomycosis: an evaluation of sensitivity and specificity. Cutis. 1998;61:217-219.

8. Wilsmann-Theis D, Sareika F, Bieber T, et al. New reasons for histopathological nail-clipping examination in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:235-237.

9. Reisberger EM, Abels C, Landthaler M, et al. Histopathological diagnosis of onychomycosis by periodic acid-Schiff-stained nail clippings. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:749-754.

10. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Collection of fungi samples from nails: comparative study of curettage and drilling techniques. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:182-185.

11. Daniel CR 3rd, Elewski BE. The diagnosis of nail fungus infection revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1162-1164.

12. Borkowski P, Williams M, Holewinski J, et al. Onychomycosis: an analysis of 50 cases and a comparison of diagnostic techniques. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:351-355.

13. Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM, et al. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin II: advances in instrumentation and comparison with histology. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:293-303.

14. Hongcharu W, Dwyer P, Gonzalez S, et al. Confirmation of onychomycosis by in vivo confocal microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):214-216.

1. Singal A, Khanna D. Onychomycosis: diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:659-672.

2. Kaur R, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. Onychomycosis—epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:108-116.

3. Richardson MD. Diagnosis and pathogenesis of dermatophyte infections. Br J Clin Pract Suppl. 1990;71:98-102.

4. Jensen RH, Arendrup MC. Molecular diagnosis of dermato-phyte infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:126-134.

5. Weinberg JM, Koestenblatt EK, Tutrone WD, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:193-197.

6. Gianni C, Morelli V, Cerri A, et al. Usefulness of histological examination for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Dermatology. 2001;202:283-288.

7. Machler BC, Kirsner RS, Elgart GW. Routine histologic examination for the diagnosis of onychomycosis: an evaluation of sensitivity and specificity. Cutis. 1998;61:217-219.

8. Wilsmann-Theis D, Sareika F, Bieber T, et al. New reasons for histopathological nail-clipping examination in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:235-237.

9. Reisberger EM, Abels C, Landthaler M, et al. Histopathological diagnosis of onychomycosis by periodic acid-Schiff-stained nail clippings. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:749-754.

10. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Collection of fungi samples from nails: comparative study of curettage and drilling techniques. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:182-185.

11. Daniel CR 3rd, Elewski BE. The diagnosis of nail fungus infection revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1162-1164.

12. Borkowski P, Williams M, Holewinski J, et al. Onychomycosis: an analysis of 50 cases and a comparison of diagnostic techniques. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:351-355.

13. Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM, et al. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin II: advances in instrumentation and comparison with histology. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:293-303.

14. Hongcharu W, Dwyer P, Gonzalez S, et al. Confirmation of onychomycosis by in vivo confocal microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):214-216.

Leser-Trélat Sign: A Paraneoplastic Process?

To the Editor:

Leser-Trélat sign is a rare skin condition characterized by the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratoses that rapidly increase in number and size within weeks to months. Co-occurrence has been reported with a large number of malignancies, particularly adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. We present a case of Leser-Trélat sign that was not associated with an underlying malignancy.

A 44-year-old man was admitted to our dermatology outpatient department with a serpigo on the neck that had grown rapidly in the last month. His medical history and family history were unremarkable. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous 3- to 4-mm brown and slightly verrucous papules on the neck (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the lesion showed acanthosis of predominantly basaloid cells, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis, as well as the presence of characteristic horn cysts (Figure 2). He was tested for possible underlying internal malignancy. Liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte count, protein electrophoresis, and whole blood and urine tests were within reference range. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography revealed no signs of pathology. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 20 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) and tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis were negative. Abdominal, cranial, and thorax computed tomography revealed no abnormalities. Otolaryngologic examinations also were negative. Additional endoscopic analyses, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and colonoscopy revealed no abnormalities. At 1-year follow-up, the seborrheic keratoses remained unchanged. He has remained in good health without specific signs or symptoms suggestive of an underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with malignancy but progress without connection to a primary tumor or metastasis and form a group of clinical manifestations. The characteristic progress of paraneoplastic syndromes shows parallelism with the progression of the tumor. The mechanism underlying the development is not known, though the actions of bioactive substances that cause responses in the tumor, such as polypeptide hormones, hormonelike peptides, antibodies or immune complexes, and cytokines or growth factors, have been implicated.1

Although the term paraneoplastic syndrome commonly is used for Leser-Trélat sign, we do not believe it is accurate. As Fink et al2 and Schwengle et al3 indicated, the possibility of the co-occurrence being fortuitous is high. Showing a parallel progress of malignancy with paraneoplastic dermatosis requires that the paraneoplastic syndrome also diminish when the tumor is cured.4 It should then reappear with cancer recurrence or metastasis, which has not been exhibited in many case presentations in the literature.3 Disease regression was observed in only 1 of 3 seborrheic keratosis cases after primary cancer treatment.5

In patients with a malignancy, the sudden increase in seborrheic keratosis is based exclusively on the subjective evaluation of the patient, which may not be reliable. Schwengle et al3 stated that this sudden increase can be related to the awareness level of the patient who had a cancer diagnosis. Bräuer et al6 stated that no plausible definition distinguishes eruptive versus common seborrheic keratoses.

As a result, the results regarding the relationship between malignancy and Leser-Trélat sign are conflicting, and no strong evidence supports the presence of the sign. Only case reports have suggested that Leser-Trélat sign accompanies malignancy. Studies investigating its etiopathogenesis have not revealed a substance that has been released from or as a response to a tumor.

We believe that the presence of eruptive seborrheic keratosis does not necessitate screening for underlying internal malignancies.

- Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic dermatopathology: cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Adv Dermatol. 1996;11:215-252.

- Fink AM, Filz D, Krajnik G, et al. Seborrhoeic keratoses in patients with internal malignancies: a case-control study with a prospective accrual of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1316-1319.

- Schwengle LE, Rampen FH, Wobbes T. Seborrhoeic keratoses and internal malignancies. a case control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:177-179.

- Curth HO. Skin lesions and internal carcinoma. In: Andrade S, Gumport S, Popkin GL, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin: Biology, Diagnosis, and Management. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1976:1308-1341.

- Heaphy MR Jr, Millns JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trélat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):386-390.

- Bräuer J, Happle R, Gieler U. The sign of Leser-Trélat: fact or myth? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1992;1:77-80.

To the Editor:

Leser-Trélat sign is a rare skin condition characterized by the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratoses that rapidly increase in number and size within weeks to months. Co-occurrence has been reported with a large number of malignancies, particularly adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. We present a case of Leser-Trélat sign that was not associated with an underlying malignancy.

A 44-year-old man was admitted to our dermatology outpatient department with a serpigo on the neck that had grown rapidly in the last month. His medical history and family history were unremarkable. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous 3- to 4-mm brown and slightly verrucous papules on the neck (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the lesion showed acanthosis of predominantly basaloid cells, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis, as well as the presence of characteristic horn cysts (Figure 2). He was tested for possible underlying internal malignancy. Liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte count, protein electrophoresis, and whole blood and urine tests were within reference range. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography revealed no signs of pathology. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 20 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) and tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis were negative. Abdominal, cranial, and thorax computed tomography revealed no abnormalities. Otolaryngologic examinations also were negative. Additional endoscopic analyses, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and colonoscopy revealed no abnormalities. At 1-year follow-up, the seborrheic keratoses remained unchanged. He has remained in good health without specific signs or symptoms suggestive of an underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with malignancy but progress without connection to a primary tumor or metastasis and form a group of clinical manifestations. The characteristic progress of paraneoplastic syndromes shows parallelism with the progression of the tumor. The mechanism underlying the development is not known, though the actions of bioactive substances that cause responses in the tumor, such as polypeptide hormones, hormonelike peptides, antibodies or immune complexes, and cytokines or growth factors, have been implicated.1

Although the term paraneoplastic syndrome commonly is used for Leser-Trélat sign, we do not believe it is accurate. As Fink et al2 and Schwengle et al3 indicated, the possibility of the co-occurrence being fortuitous is high. Showing a parallel progress of malignancy with paraneoplastic dermatosis requires that the paraneoplastic syndrome also diminish when the tumor is cured.4 It should then reappear with cancer recurrence or metastasis, which has not been exhibited in many case presentations in the literature.3 Disease regression was observed in only 1 of 3 seborrheic keratosis cases after primary cancer treatment.5

In patients with a malignancy, the sudden increase in seborrheic keratosis is based exclusively on the subjective evaluation of the patient, which may not be reliable. Schwengle et al3 stated that this sudden increase can be related to the awareness level of the patient who had a cancer diagnosis. Bräuer et al6 stated that no plausible definition distinguishes eruptive versus common seborrheic keratoses.

As a result, the results regarding the relationship between malignancy and Leser-Trélat sign are conflicting, and no strong evidence supports the presence of the sign. Only case reports have suggested that Leser-Trélat sign accompanies malignancy. Studies investigating its etiopathogenesis have not revealed a substance that has been released from or as a response to a tumor.

We believe that the presence of eruptive seborrheic keratosis does not necessitate screening for underlying internal malignancies.

To the Editor:

Leser-Trélat sign is a rare skin condition characterized by the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratoses that rapidly increase in number and size within weeks to months. Co-occurrence has been reported with a large number of malignancies, particularly adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. We present a case of Leser-Trélat sign that was not associated with an underlying malignancy.

A 44-year-old man was admitted to our dermatology outpatient department with a serpigo on the neck that had grown rapidly in the last month. His medical history and family history were unremarkable. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous 3- to 4-mm brown and slightly verrucous papules on the neck (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the lesion showed acanthosis of predominantly basaloid cells, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis, as well as the presence of characteristic horn cysts (Figure 2). He was tested for possible underlying internal malignancy. Liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte count, protein electrophoresis, and whole blood and urine tests were within reference range. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography revealed no signs of pathology. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 20 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) and tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis were negative. Abdominal, cranial, and thorax computed tomography revealed no abnormalities. Otolaryngologic examinations also were negative. Additional endoscopic analyses, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and colonoscopy revealed no abnormalities. At 1-year follow-up, the seborrheic keratoses remained unchanged. He has remained in good health without specific signs or symptoms suggestive of an underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with malignancy but progress without connection to a primary tumor or metastasis and form a group of clinical manifestations. The characteristic progress of paraneoplastic syndromes shows parallelism with the progression of the tumor. The mechanism underlying the development is not known, though the actions of bioactive substances that cause responses in the tumor, such as polypeptide hormones, hormonelike peptides, antibodies or immune complexes, and cytokines or growth factors, have been implicated.1

Although the term paraneoplastic syndrome commonly is used for Leser-Trélat sign, we do not believe it is accurate. As Fink et al2 and Schwengle et al3 indicated, the possibility of the co-occurrence being fortuitous is high. Showing a parallel progress of malignancy with paraneoplastic dermatosis requires that the paraneoplastic syndrome also diminish when the tumor is cured.4 It should then reappear with cancer recurrence or metastasis, which has not been exhibited in many case presentations in the literature.3 Disease regression was observed in only 1 of 3 seborrheic keratosis cases after primary cancer treatment.5

In patients with a malignancy, the sudden increase in seborrheic keratosis is based exclusively on the subjective evaluation of the patient, which may not be reliable. Schwengle et al3 stated that this sudden increase can be related to the awareness level of the patient who had a cancer diagnosis. Bräuer et al6 stated that no plausible definition distinguishes eruptive versus common seborrheic keratoses.

As a result, the results regarding the relationship between malignancy and Leser-Trélat sign are conflicting, and no strong evidence supports the presence of the sign. Only case reports have suggested that Leser-Trélat sign accompanies malignancy. Studies investigating its etiopathogenesis have not revealed a substance that has been released from or as a response to a tumor.

We believe that the presence of eruptive seborrheic keratosis does not necessitate screening for underlying internal malignancies.

- Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic dermatopathology: cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Adv Dermatol. 1996;11:215-252.

- Fink AM, Filz D, Krajnik G, et al. Seborrhoeic keratoses in patients with internal malignancies: a case-control study with a prospective accrual of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1316-1319.

- Schwengle LE, Rampen FH, Wobbes T. Seborrhoeic keratoses and internal malignancies. a case control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:177-179.

- Curth HO. Skin lesions and internal carcinoma. In: Andrade S, Gumport S, Popkin GL, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin: Biology, Diagnosis, and Management. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1976:1308-1341.

- Heaphy MR Jr, Millns JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trélat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):386-390.

- Bräuer J, Happle R, Gieler U. The sign of Leser-Trélat: fact or myth? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1992;1:77-80.

- Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic dermatopathology: cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Adv Dermatol. 1996;11:215-252.

- Fink AM, Filz D, Krajnik G, et al. Seborrhoeic keratoses in patients with internal malignancies: a case-control study with a prospective accrual of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1316-1319.

- Schwengle LE, Rampen FH, Wobbes T. Seborrhoeic keratoses and internal malignancies. a case control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:177-179.

- Curth HO. Skin lesions and internal carcinoma. In: Andrade S, Gumport S, Popkin GL, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin: Biology, Diagnosis, and Management. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1976:1308-1341.

- Heaphy MR Jr, Millns JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trélat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):386-390.

- Bräuer J, Happle R, Gieler U. The sign of Leser-Trélat: fact or myth? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1992;1:77-80.

Eleven Years of Itching: A Case Report of Crusted Scabies

Case Report

A 48-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with pruritus of 11 years’ duration that worsened at night. He had been followed at a different clinic for several years and was unsuccessfully treated with topical permethrin and oral antihistamines on multiple occasions for scabies. He also had been intermittently treated for contact dermatitis with topical and systemic steroids, which also brought no relief. Just prior to his presentation, the patient’s wife and 8-year-old son had sought medical attention at our institution for chronic pruritus and elevated IgE levels. They had been unsuccessfully treated with topical permethrin, topical steroids, and oral antihistamines for atopic dermatitis at a different clinic. When they presented to our clinic, they were both diagnosed with and treated for scabies. At this visit the patient revealed similar concerns and subsequently underwent examination.

Physical examination revealed large erythematous, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques on the gluteal fold, um-bilicus, glans penis, scrotum, bilateral elbows, knees, nipples, and ear helices (Figure 1). Numerous small erythematous papules and wavy threadlike gray burrows measuring 1 to 10 mm in diameter were distributed primarily around the wrists, ankles, proximal extremities, abdominal and pubic area (Figure 2), and interdigital spaces. Wide oval patches of nonscarring alopecia developed on the scalp, and atrophic glossitis and angular cheilitis were noted on the oral mucosa, along with a white pseudomembranous exudate on the palatum. The patient’s nails also were thickened and discolored (Figure 3). His medical history was remarkable for hypoparathyroidism (42 years), alopecia areata (15 years), oral candidiasis and angular cheilitis (10 years), and primary hypothyroidism (1 year) that was currently being treated with levothyroxine.

|  |

| Figure 1. Large erythematous, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques on the ear helices (A), gluteal fold, and bilateral elbows (B) in a 48-year-old man with crusted scabies. | |

| |

| Figure 2. Numerous small erythematous papules and wavy, threadlike, grayish, 1- to 10-mm burrows distributed in the abdominal and pubic area. | |

| |

| Figure 3. Thickened and discolored nails in a 48-year-old man with crusted scabies. | |

| |

| |

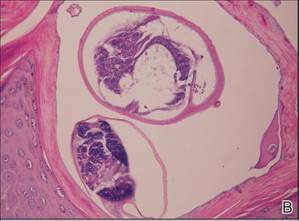

| Figure 4. The psoriasiform epidermis showed massive hyperkeratosis and burrows in the subcorneal layer containing a large number of female mites and feces (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). A substantial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with numerous eosinophils was seen diffusely throughout the dermis, though most prominently within the upper half. High-power examination demonstrated mites in the burrow (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). | |

Laboratory studies revealed normal hemogram with an eosinophil level of 0% (reference range, 0.9%–6%). Biochemistry and hormone profiles were consistent with hypoparathyroidism, with the following levels: serum calcium, 7.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.4–10.2 mg/dL); phosphorus, 5.1 mg/dL (reference range, 2.4–4.4 mg/dL); and parathyroid hormone, 5.23 pg/mL (reference range, 15–65 pg/mL). The patient tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus.

Dermoscopic examination of the gray threadlike burrows revealed distinctive brown-colored triangular structures that were removed with a fine scalpel. Microscopic examination of the tissue revealed moving mites, eggs, and red-brown scybala.

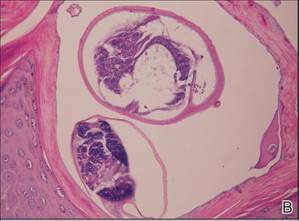

A biopsy was taken from the thick, scaly, crusted white plaques in the gluteal area. The epidermis showed massive hyperkeratosis and burrows in the subcorneal layer containing a large number of female mites and feces, while the remainder of the epidermis was substantially psoriasiform. A substantial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with numerous eosinophils was seen diffusely throughout the dermis, though it was most prominent within the upper half (Figure 4). The patient subsequently was diagnosed with crusted scabies.

Crusted scabies typically develops in patients with defective T-cell immunity or a reduced ability to mechanically debride the mites. Because our patient had a history of persistent oral candidiasis, further investigation for immunosuppression was initiated. An immunosuppression panel revealed low IgA levels (46 mg/dL [reference range, 82–453 mg/dL]), low absolute CD8 level (145 cells/µL [reference range, 300–1800 cells/µL), and CD4:CD8 ratio of 4.1. Serum IgG, IgM, IgE, complement levels, and immunoelectrophoresis were within reference range. Abdominal ultrasonography was unremarkable. Taking into account the patient’s history of autoimmune hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, oral candidiasis, and alopecia areata, he was diagnosed with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.

The patient and his family were successfully treated with modified Wilkinson ointment (goudron végétal 12.5%; sulfur 12.5% in petrolatum) for 3 consecutive days. Within 1 week, the scaly plaques had disappeared and the erythematous papules had faded. The pruritus had resolved and no new papules emerged. Treatment was reapplied once more the following week and complete cure was achieved. We have been following this family for 12 months and no recurrences have occurred.

Comment

Crusted scabies is a rare and highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of mites in the skin, extensive hyperkeratotic scaling, crusted lesions, and variable pruritus.1 The stratum corneum thickens and forms warty crusts as a reaction to the high mite burden.2 The uncontrolled proliferation of mites in the skin typically develops in patients with a defective T-cell response or decreased cutaneous sensation and reduced ability to mechanically debride the mites.3 Patients should be investigated for a predisposition to crusted scabies due to an underlying condition. Crusted scabies also has been shown to develop in Australian natives with normal immunity, though the etiology of the increased susceptibility in this patient population remains unclear. Some studies have shown an association with HLA-A11.4,5 It also has been hypothesized that these patients may have a specific immunodeficiency predisposing them to hyperinfestation.6

Unlike classic scabies, crusted scabies usually does not present acutely, and it usually is insidious at onset. The eruption typically has 2 components: localized horny plaques and a more distinct erythema.3 Crusted scabies can mimic a variety of conditions such as psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, Darier disease, contact dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.7 When pruritus is resistant to permethrin therapy, as in our patient, crusted scabies often is misdiagnosed as eczema or contact dermatitis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids often are prescribed, causing progression to scabies incognito.

The diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by examination of scrapings and biopsies, as in classic scabies; however, treatment can be challenging due to compromised immunity, a large mite burden, and limited penetration of topical medications into the hyperkeratotic lesions. Thus treatment should include both keratolytic and scabicidal agents to remove the crusts, reduce the mite load, and enhance the scabicidal therapy.1 Our patient and his affected family members had previously been treated with topical permethrin several times without any benefit. Oral ivermectin has been proven to be effective but is not available in Turkey. Therefore, we treated the patient and his household contacts (other extended family members treated separately) with modified Wilkinson ointment (goudron végétal 12.5%; sulfur 12.5% in petrolatum) for 3 consecutive days, which is known to have both a keratolytic and scabicidal effect.8-11

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of obtaining a complete family history, skin examination, and thorough investigation for underlying immunodeficiencies that can lead to a predisposition for crusted scabies. It is important to note that the treatment of crusted scabies can be challenging, and effective management of the condition requires a keratolytic agent in conjunction with a scabicidal agent.

1. Douri T, Shawaf AZ. Treatment of crusted scabies with albenzdazole: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Burns DA. Diseases caused by arthropods and other noxious animals. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 1998:1423-1482.

3. Karthiyekan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Falk ES, Thorsby E. HLA antigens in patients with scabies. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:317-320.

5. Morsy TA, Romia SA, al-Ganayni GA, et al. Histocompatibility (HLA) antigens in Egyptians with two parasitic skin diseases (scabies and leishmaniasis). J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1990;20:565-572.

6. Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

7. Jucowics P, Ramon ME, Don PC, et al. Norwegian scabies in an infant with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1670-1671.

8. Goldsmith WN. Wilkinson’s ointment. Br Med J. 1945;1:347-348.

9. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

10. Gupta AK, Nikol K. The use of sulfur in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:427-431.

11. Lin AN, Moses K. Tar revisited. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:216-219.

Case Report

A 48-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with pruritus of 11 years’ duration that worsened at night. He had been followed at a different clinic for several years and was unsuccessfully treated with topical permethrin and oral antihistamines on multiple occasions for scabies. He also had been intermittently treated for contact dermatitis with topical and systemic steroids, which also brought no relief. Just prior to his presentation, the patient’s wife and 8-year-old son had sought medical attention at our institution for chronic pruritus and elevated IgE levels. They had been unsuccessfully treated with topical permethrin, topical steroids, and oral antihistamines for atopic dermatitis at a different clinic. When they presented to our clinic, they were both diagnosed with and treated for scabies. At this visit the patient revealed similar concerns and subsequently underwent examination.

Physical examination revealed large erythematous, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques on the gluteal fold, um-bilicus, glans penis, scrotum, bilateral elbows, knees, nipples, and ear helices (Figure 1). Numerous small erythematous papules and wavy threadlike gray burrows measuring 1 to 10 mm in diameter were distributed primarily around the wrists, ankles, proximal extremities, abdominal and pubic area (Figure 2), and interdigital spaces. Wide oval patches of nonscarring alopecia developed on the scalp, and atrophic glossitis and angular cheilitis were noted on the oral mucosa, along with a white pseudomembranous exudate on the palatum. The patient’s nails also were thickened and discolored (Figure 3). His medical history was remarkable for hypoparathyroidism (42 years), alopecia areata (15 years), oral candidiasis and angular cheilitis (10 years), and primary hypothyroidism (1 year) that was currently being treated with levothyroxine.

|  |

| Figure 1. Large erythematous, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques on the ear helices (A), gluteal fold, and bilateral elbows (B) in a 48-year-old man with crusted scabies. | |

| |

| Figure 2. Numerous small erythematous papules and wavy, threadlike, grayish, 1- to 10-mm burrows distributed in the abdominal and pubic area. | |

| |

| Figure 3. Thickened and discolored nails in a 48-year-old man with crusted scabies. | |

| |

| |

| Figure 4. The psoriasiform epidermis showed massive hyperkeratosis and burrows in the subcorneal layer containing a large number of female mites and feces (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). A substantial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with numerous eosinophils was seen diffusely throughout the dermis, though most prominently within the upper half. High-power examination demonstrated mites in the burrow (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). | |

Laboratory studies revealed normal hemogram with an eosinophil level of 0% (reference range, 0.9%–6%). Biochemistry and hormone profiles were consistent with hypoparathyroidism, with the following levels: serum calcium, 7.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.4–10.2 mg/dL); phosphorus, 5.1 mg/dL (reference range, 2.4–4.4 mg/dL); and parathyroid hormone, 5.23 pg/mL (reference range, 15–65 pg/mL). The patient tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus.

Dermoscopic examination of the gray threadlike burrows revealed distinctive brown-colored triangular structures that were removed with a fine scalpel. Microscopic examination of the tissue revealed moving mites, eggs, and red-brown scybala.

A biopsy was taken from the thick, scaly, crusted white plaques in the gluteal area. The epidermis showed massive hyperkeratosis and burrows in the subcorneal layer containing a large number of female mites and feces, while the remainder of the epidermis was substantially psoriasiform. A substantial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with numerous eosinophils was seen diffusely throughout the dermis, though it was most prominent within the upper half (Figure 4). The patient subsequently was diagnosed with crusted scabies.

Crusted scabies typically develops in patients with defective T-cell immunity or a reduced ability to mechanically debride the mites. Because our patient had a history of persistent oral candidiasis, further investigation for immunosuppression was initiated. An immunosuppression panel revealed low IgA levels (46 mg/dL [reference range, 82–453 mg/dL]), low absolute CD8 level (145 cells/µL [reference range, 300–1800 cells/µL), and CD4:CD8 ratio of 4.1. Serum IgG, IgM, IgE, complement levels, and immunoelectrophoresis were within reference range. Abdominal ultrasonography was unremarkable. Taking into account the patient’s history of autoimmune hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, oral candidiasis, and alopecia areata, he was diagnosed with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.

The patient and his family were successfully treated with modified Wilkinson ointment (goudron végétal 12.5%; sulfur 12.5% in petrolatum) for 3 consecutive days. Within 1 week, the scaly plaques had disappeared and the erythematous papules had faded. The pruritus had resolved and no new papules emerged. Treatment was reapplied once more the following week and complete cure was achieved. We have been following this family for 12 months and no recurrences have occurred.

Comment

Crusted scabies is a rare and highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of mites in the skin, extensive hyperkeratotic scaling, crusted lesions, and variable pruritus.1 The stratum corneum thickens and forms warty crusts as a reaction to the high mite burden.2 The uncontrolled proliferation of mites in the skin typically develops in patients with a defective T-cell response or decreased cutaneous sensation and reduced ability to mechanically debride the mites.3 Patients should be investigated for a predisposition to crusted scabies due to an underlying condition. Crusted scabies also has been shown to develop in Australian natives with normal immunity, though the etiology of the increased susceptibility in this patient population remains unclear. Some studies have shown an association with HLA-A11.4,5 It also has been hypothesized that these patients may have a specific immunodeficiency predisposing them to hyperinfestation.6

Unlike classic scabies, crusted scabies usually does not present acutely, and it usually is insidious at onset. The eruption typically has 2 components: localized horny plaques and a more distinct erythema.3 Crusted scabies can mimic a variety of conditions such as psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, Darier disease, contact dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.7 When pruritus is resistant to permethrin therapy, as in our patient, crusted scabies often is misdiagnosed as eczema or contact dermatitis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids often are prescribed, causing progression to scabies incognito.

The diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by examination of scrapings and biopsies, as in classic scabies; however, treatment can be challenging due to compromised immunity, a large mite burden, and limited penetration of topical medications into the hyperkeratotic lesions. Thus treatment should include both keratolytic and scabicidal agents to remove the crusts, reduce the mite load, and enhance the scabicidal therapy.1 Our patient and his affected family members had previously been treated with topical permethrin several times without any benefit. Oral ivermectin has been proven to be effective but is not available in Turkey. Therefore, we treated the patient and his household contacts (other extended family members treated separately) with modified Wilkinson ointment (goudron végétal 12.5%; sulfur 12.5% in petrolatum) for 3 consecutive days, which is known to have both a keratolytic and scabicidal effect.8-11

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of obtaining a complete family history, skin examination, and thorough investigation for underlying immunodeficiencies that can lead to a predisposition for crusted scabies. It is important to note that the treatment of crusted scabies can be challenging, and effective management of the condition requires a keratolytic agent in conjunction with a scabicidal agent.

Case Report

A 48-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with pruritus of 11 years’ duration that worsened at night. He had been followed at a different clinic for several years and was unsuccessfully treated with topical permethrin and oral antihistamines on multiple occasions for scabies. He also had been intermittently treated for contact dermatitis with topical and systemic steroids, which also brought no relief. Just prior to his presentation, the patient’s wife and 8-year-old son had sought medical attention at our institution for chronic pruritus and elevated IgE levels. They had been unsuccessfully treated with topical permethrin, topical steroids, and oral antihistamines for atopic dermatitis at a different clinic. When they presented to our clinic, they were both diagnosed with and treated for scabies. At this visit the patient revealed similar concerns and subsequently underwent examination.

Physical examination revealed large erythematous, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques on the gluteal fold, um-bilicus, glans penis, scrotum, bilateral elbows, knees, nipples, and ear helices (Figure 1). Numerous small erythematous papules and wavy threadlike gray burrows measuring 1 to 10 mm in diameter were distributed primarily around the wrists, ankles, proximal extremities, abdominal and pubic area (Figure 2), and interdigital spaces. Wide oval patches of nonscarring alopecia developed on the scalp, and atrophic glossitis and angular cheilitis were noted on the oral mucosa, along with a white pseudomembranous exudate on the palatum. The patient’s nails also were thickened and discolored (Figure 3). His medical history was remarkable for hypoparathyroidism (42 years), alopecia areata (15 years), oral candidiasis and angular cheilitis (10 years), and primary hypothyroidism (1 year) that was currently being treated with levothyroxine.

|  |

| Figure 1. Large erythematous, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques on the ear helices (A), gluteal fold, and bilateral elbows (B) in a 48-year-old man with crusted scabies. | |

| |

| Figure 2. Numerous small erythematous papules and wavy, threadlike, grayish, 1- to 10-mm burrows distributed in the abdominal and pubic area. | |

| |

| Figure 3. Thickened and discolored nails in a 48-year-old man with crusted scabies. | |

| |

| |

| Figure 4. The psoriasiform epidermis showed massive hyperkeratosis and burrows in the subcorneal layer containing a large number of female mites and feces (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). A substantial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with numerous eosinophils was seen diffusely throughout the dermis, though most prominently within the upper half. High-power examination demonstrated mites in the burrow (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). | |

Laboratory studies revealed normal hemogram with an eosinophil level of 0% (reference range, 0.9%–6%). Biochemistry and hormone profiles were consistent with hypoparathyroidism, with the following levels: serum calcium, 7.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.4–10.2 mg/dL); phosphorus, 5.1 mg/dL (reference range, 2.4–4.4 mg/dL); and parathyroid hormone, 5.23 pg/mL (reference range, 15–65 pg/mL). The patient tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus.

Dermoscopic examination of the gray threadlike burrows revealed distinctive brown-colored triangular structures that were removed with a fine scalpel. Microscopic examination of the tissue revealed moving mites, eggs, and red-brown scybala.

A biopsy was taken from the thick, scaly, crusted white plaques in the gluteal area. The epidermis showed massive hyperkeratosis and burrows in the subcorneal layer containing a large number of female mites and feces, while the remainder of the epidermis was substantially psoriasiform. A substantial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with numerous eosinophils was seen diffusely throughout the dermis, though it was most prominent within the upper half (Figure 4). The patient subsequently was diagnosed with crusted scabies.

Crusted scabies typically develops in patients with defective T-cell immunity or a reduced ability to mechanically debride the mites. Because our patient had a history of persistent oral candidiasis, further investigation for immunosuppression was initiated. An immunosuppression panel revealed low IgA levels (46 mg/dL [reference range, 82–453 mg/dL]), low absolute CD8 level (145 cells/µL [reference range, 300–1800 cells/µL), and CD4:CD8 ratio of 4.1. Serum IgG, IgM, IgE, complement levels, and immunoelectrophoresis were within reference range. Abdominal ultrasonography was unremarkable. Taking into account the patient’s history of autoimmune hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, oral candidiasis, and alopecia areata, he was diagnosed with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.

The patient and his family were successfully treated with modified Wilkinson ointment (goudron végétal 12.5%; sulfur 12.5% in petrolatum) for 3 consecutive days. Within 1 week, the scaly plaques had disappeared and the erythematous papules had faded. The pruritus had resolved and no new papules emerged. Treatment was reapplied once more the following week and complete cure was achieved. We have been following this family for 12 months and no recurrences have occurred.

Comment

Crusted scabies is a rare and highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of mites in the skin, extensive hyperkeratotic scaling, crusted lesions, and variable pruritus.1 The stratum corneum thickens and forms warty crusts as a reaction to the high mite burden.2 The uncontrolled proliferation of mites in the skin typically develops in patients with a defective T-cell response or decreased cutaneous sensation and reduced ability to mechanically debride the mites.3 Patients should be investigated for a predisposition to crusted scabies due to an underlying condition. Crusted scabies also has been shown to develop in Australian natives with normal immunity, though the etiology of the increased susceptibility in this patient population remains unclear. Some studies have shown an association with HLA-A11.4,5 It also has been hypothesized that these patients may have a specific immunodeficiency predisposing them to hyperinfestation.6

Unlike classic scabies, crusted scabies usually does not present acutely, and it usually is insidious at onset. The eruption typically has 2 components: localized horny plaques and a more distinct erythema.3 Crusted scabies can mimic a variety of conditions such as psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, Darier disease, contact dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.7 When pruritus is resistant to permethrin therapy, as in our patient, crusted scabies often is misdiagnosed as eczema or contact dermatitis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids often are prescribed, causing progression to scabies incognito.

The diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by examination of scrapings and biopsies, as in classic scabies; however, treatment can be challenging due to compromised immunity, a large mite burden, and limited penetration of topical medications into the hyperkeratotic lesions. Thus treatment should include both keratolytic and scabicidal agents to remove the crusts, reduce the mite load, and enhance the scabicidal therapy.1 Our patient and his affected family members had previously been treated with topical permethrin several times without any benefit. Oral ivermectin has been proven to be effective but is not available in Turkey. Therefore, we treated the patient and his household contacts (other extended family members treated separately) with modified Wilkinson ointment (goudron végétal 12.5%; sulfur 12.5% in petrolatum) for 3 consecutive days, which is known to have both a keratolytic and scabicidal effect.8-11

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of obtaining a complete family history, skin examination, and thorough investigation for underlying immunodeficiencies that can lead to a predisposition for crusted scabies. It is important to note that the treatment of crusted scabies can be challenging, and effective management of the condition requires a keratolytic agent in conjunction with a scabicidal agent.

1. Douri T, Shawaf AZ. Treatment of crusted scabies with albenzdazole: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Burns DA. Diseases caused by arthropods and other noxious animals. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 1998:1423-1482.

3. Karthiyekan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Falk ES, Thorsby E. HLA antigens in patients with scabies. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:317-320.

5. Morsy TA, Romia SA, al-Ganayni GA, et al. Histocompatibility (HLA) antigens in Egyptians with two parasitic skin diseases (scabies and leishmaniasis). J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1990;20:565-572.

6. Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

7. Jucowics P, Ramon ME, Don PC, et al. Norwegian scabies in an infant with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1670-1671.

8. Goldsmith WN. Wilkinson’s ointment. Br Med J. 1945;1:347-348.

9. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

10. Gupta AK, Nikol K. The use of sulfur in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:427-431.

11. Lin AN, Moses K. Tar revisited. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:216-219.

1. Douri T, Shawaf AZ. Treatment of crusted scabies with albenzdazole: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Burns DA. Diseases caused by arthropods and other noxious animals. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 1998:1423-1482.

3. Karthiyekan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Falk ES, Thorsby E. HLA antigens in patients with scabies. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:317-320.

5. Morsy TA, Romia SA, al-Ganayni GA, et al. Histocompatibility (HLA) antigens in Egyptians with two parasitic skin diseases (scabies and leishmaniasis). J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1990;20:565-572.

6. Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

7. Jucowics P, Ramon ME, Don PC, et al. Norwegian scabies in an infant with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1670-1671.

8. Goldsmith WN. Wilkinson’s ointment. Br Med J. 1945;1:347-348.

9. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

10. Gupta AK, Nikol K. The use of sulfur in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:427-431.

11. Lin AN, Moses K. Tar revisited. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:216-219.

Practice Points

- Crusted scabies can mimic a variety of conditions such as psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis. Therefore, suspicion is the prerequisite for disease control.

- Scabies usually is found in individuals with a compromised immune system as well as those with decreased sensory functions. Thus patients should be investigated for an underlying immunodeficiency.

- Treatment can be challenging, and effective management of the condition requires a keratolytic agent in conjunction with a scabicidal agent.