User login

Top DEI Topics to Incorporate Into Dermatology Residency Training: An Electronic Delphi Consensus Study

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

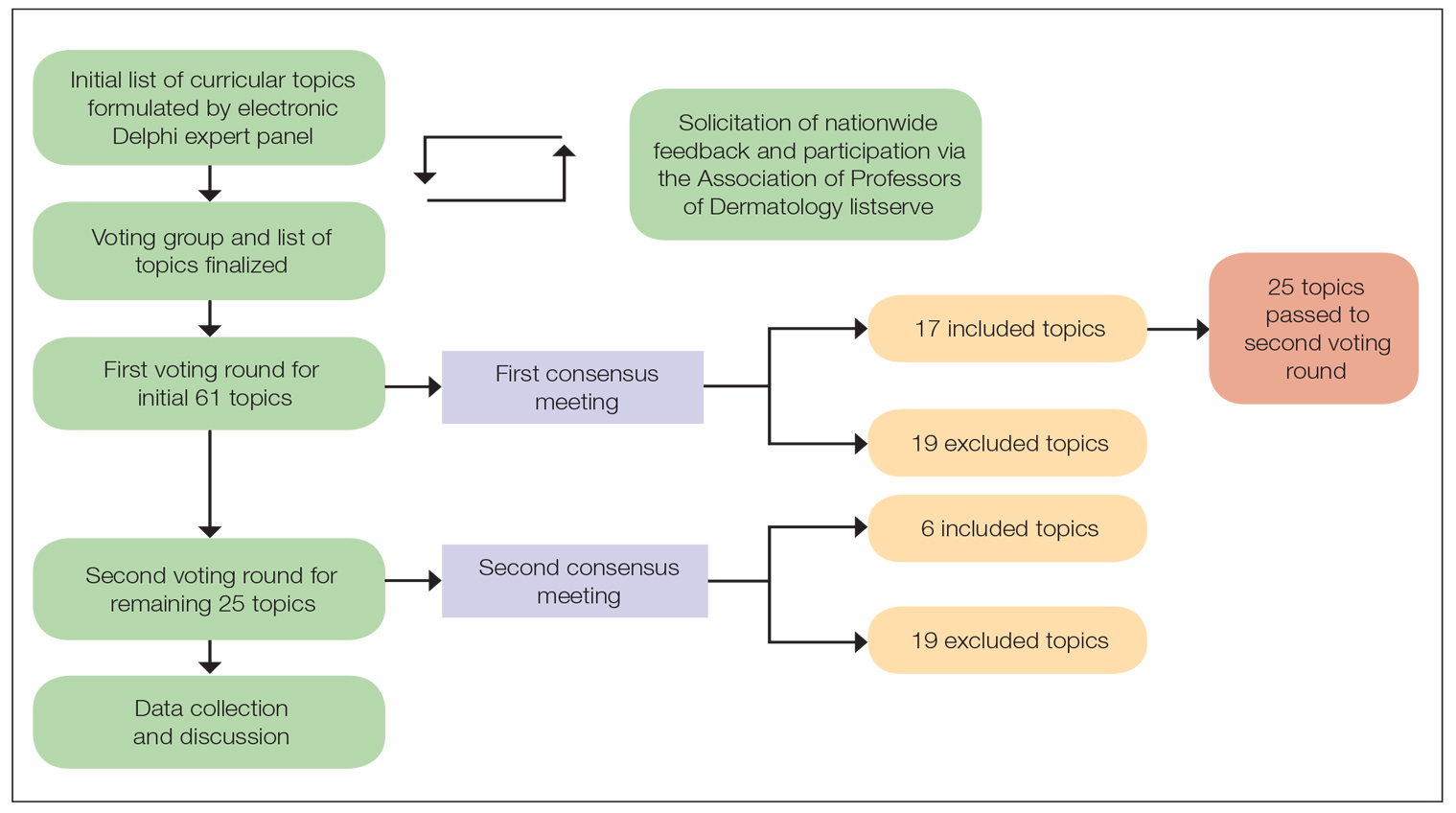

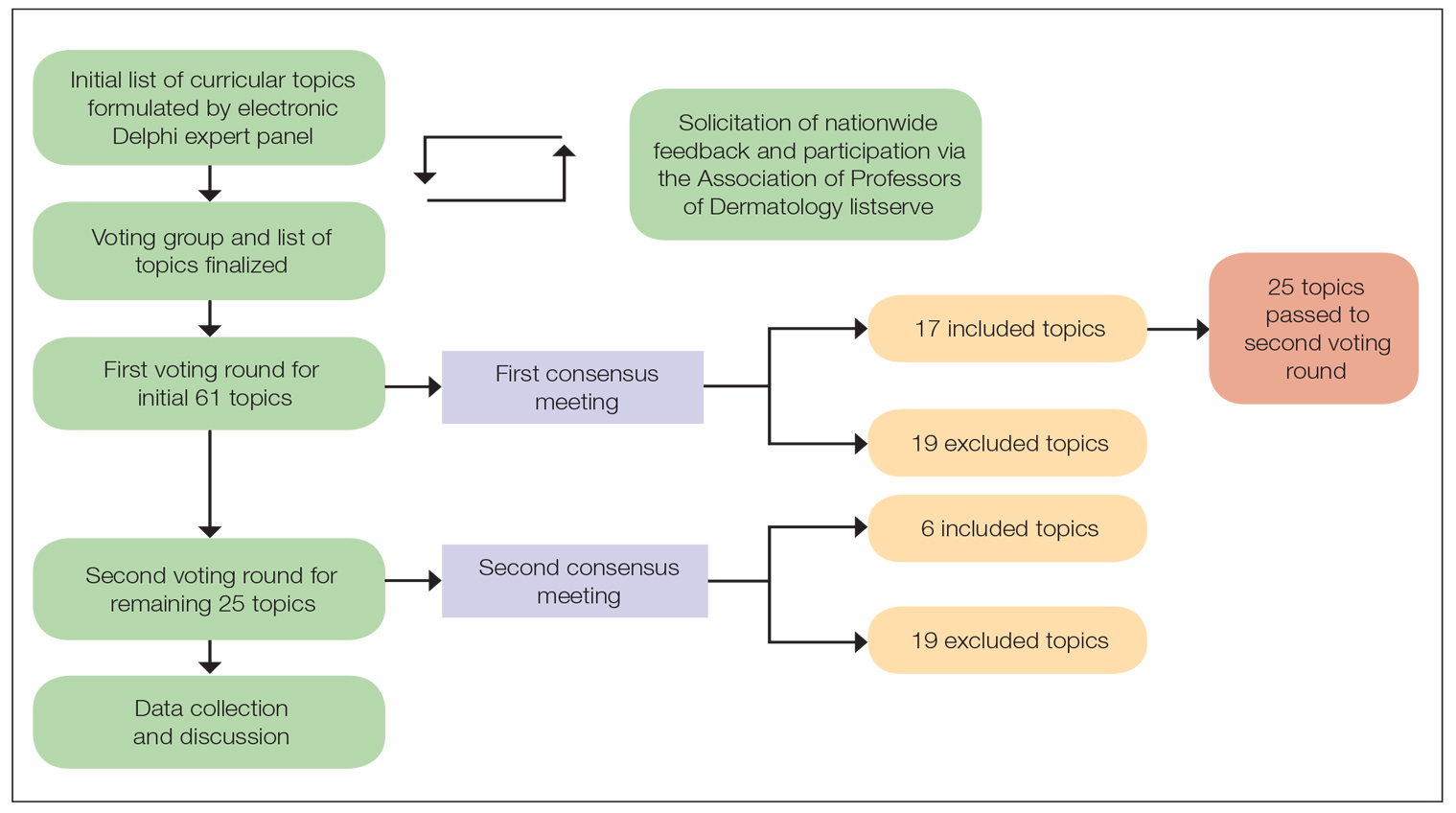

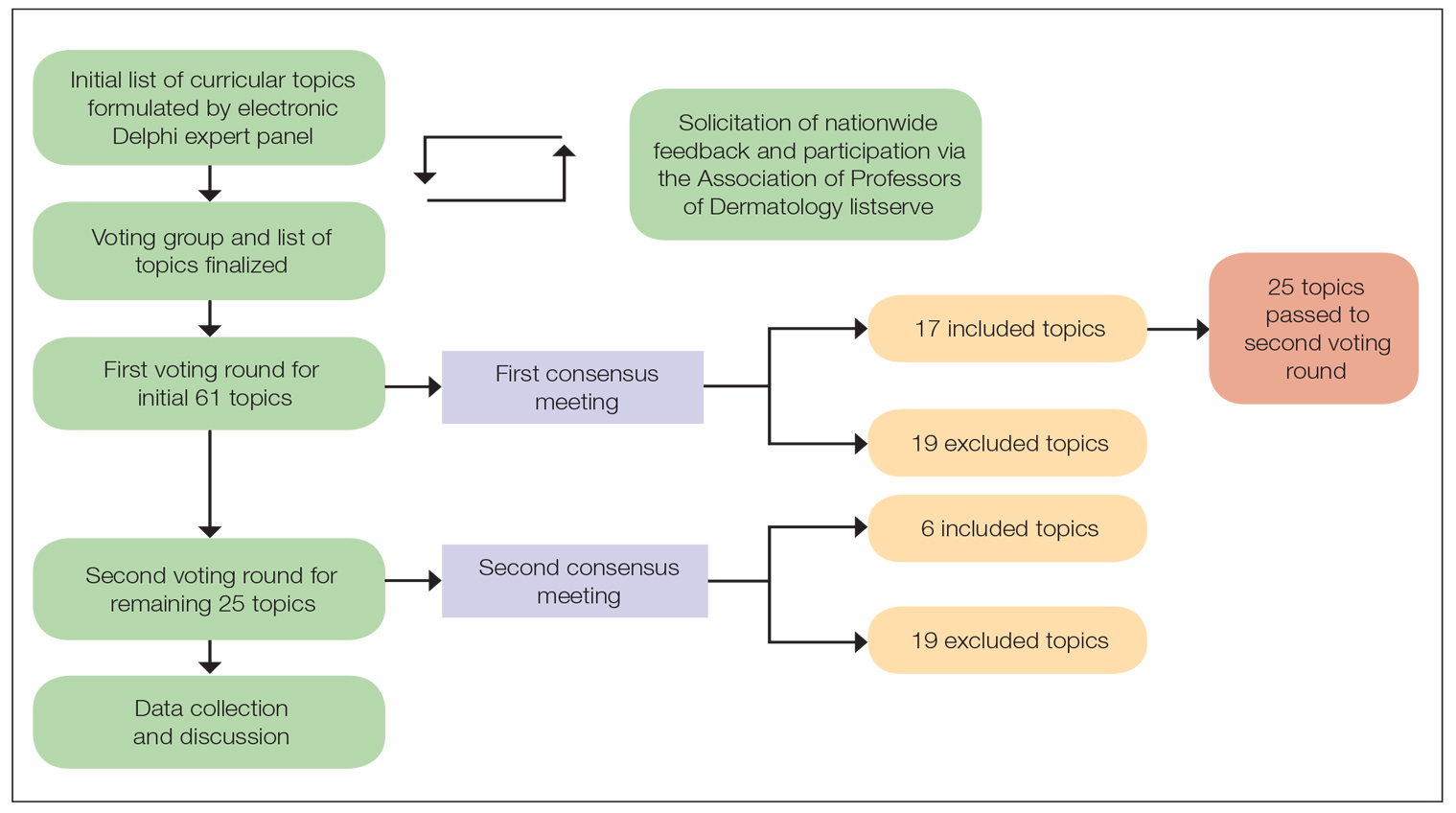

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

PRACTICE POINTS

- Advancing curricula related to diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology training can improve health outcomes, address health care workforce disparities, and enhance clinical care for diverse patient populations.

- Education on patient-centered communication, cultural humility, and the impact of social determinants of health results in dermatology residents who are better equipped with the necessary tools to effectively care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Dermatology Continuing Certification Changes for the Better

Major changes in continuing board certification are occurring across medical specialties. On January 6, 2020, the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) launches its new web-based longitudinal assessment program called CertLink (https://abderm.mycertlink.org/).1 This new platform is designed to eventually replace the sit-down, high-stakes, once-every-10-year medical knowledge examination that dermatologists take to remain board certified. With this alternative, every participating dermatologist will receive a batch of 13 web-based questions every quarter that he/she may answer at a convenient time and place. Questions are answered one at a time or in batches, depending on the test taker’s preference, and can be completed on home or office computers (and eventually on smartphones). Participating in this type of testing does not require shutting down practice, traveling to a test center, or paying for expensive board review courses. CertLink is designed to be convenient, affordable, and relevant to an individual’s practice.

How did the ABD arrive at CertLink?

The ABD launched its original Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program in 2006. Since then, newly board-certified dermatologists, recertifying dermatologists with time-limited certificates, and time-unlimited dermatologists who volunteered to participate in MOC have experienced the dermatology MOC program. In its first 10 years, the program was met with very mixed reviews. The program was designed to assess and promote competence in a 4-part framework, including professionalism; commitment to lifelong learning and self-assessment; demonstration of knowledge, judgment, and skills; and improvement in medical practice. All 4 are areas of rational pursuit for medical professionals seeking to perform and maintain the highest quality patient care possible. But there were problems. First iterations are rarely perfect, and dermatology MOC was no exception.

At the onset, the ABD chose to oversee the MOC requirements and remained hands off in the delivery of education, relying instead on other organizations to fulfill the ABD’s requirements. Unfortunately, with limited educational offerings available, many diplomates paid notable registration fees for each qualifying MOC activity. Quality improvement activities were a relatively new experience for dermatologists and were time consuming. Required medical record reviews were onerous, often requiring more than 35 data points to be collected per medical record reviewed. The limited number and limited diversity of educational offerings also created circumstances in which the material covered was not maximally relevant to many participants. When paying to answer questions about patient populations or procedure types never encountered by the dermatologist who purchased the particular MOC activity, many asked the question “How does this make me a better doctor?” They were right to ask.

Cost, time commitment to participate in MOC, and relevance to practice were 3 key areas of concern for many dermatologists. In response to internal and external MOC feedback, in 2015 the ABD took a hard look at its 10-year experience with MOC. While contemplating its next strategies, the ABD temporarily put its component 4—practice improvement—requirements on hold. After much review, the ABD decided to take over a notable portion of the education delivery. Its goal was to provide education that would fulfill MOC requirements in a more affordable, relevant, quicker, and easier manner.

First, the ABD made the decision to assume a more notable role as educator, in part to offer qualifying activities at no additional cost to diplomates. By taking on the role as educator, 3 major changes resulted: the way ABD approached quality improvement activities, partnership to initiate a question-of-the-week self-assessment program, and initiation of a longitudinal assessment strategy that resulted in this month’s launch of CertLink.

The ABD revolutionized its quality improvement requirements with the launch of its practice improvement modules made available through its website.2 These modules utilize recently published clinical practice gaps in 5 dermatology subspecialty domains to fulfill the practice improvement requirements. Participants read a brief synopsis of the supporting literature explaining practice improvement recommendations found in the module. Next, they find 5 patients in their practice with the condition, medication, or process in question and review whether they provided the care supported by the best available evidence. No module requires more than 5 medical records to review, and no more than 3 questions are answered per medical record review. If review confirms that the care was appropriate, no further action is needed. If a care gap is identified, then participants implement changes and later remeasure practice to detect any change. This certification activity was incredibly popular with the thousands of diplomates who have participated thus far; more than 97% stated the modules were relevant to practice, 98% stated they would recommend the modules to fellow dermatologists, and nearly 25% reported the module helped to change their practice for the better (unpublished data, July 2019). Relevance had been restored.

The ABD worked closely with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) to develop new education for weekly self-assessment. The ABD created the content and delivered to the AAD the first year of material for what would become the most successful and popular dermatology CME activity in history: the AAD Question of the Week (QOW). Thousands of dermatologists are registered to receive the QOW, with very active weekly participation. Participants receive 1 self-assessment point and 0.25 CME credits for each attempted question, right or wrong. This quizzing tool also was educational, with explanation of right answers and wrong choices included. The average amount of time spent answering each question was approximately 40 seconds. American Academy of Dermatology members can participate in its QOW as a member benefit. Self-assessment is no longer a time- consuming or costly process.

The third major change was the ABD initiation of the longitudinal assessment strategy called CertLink, a web-based testing platform operated by the American Board of Medical Specialties. Longitudinal assessment differs from traditional certification and recertification assessment. It allows the test taker to answer the certification test questions over time instead of all at once. Longitudinal assessment not only provides a greater level of convenience to the test taker but also allows boards a more continuous set of touch points in the assessment of diplomates over the course of the continuing certification period.

What will be part of CertLink?

In addition to standard multiple-choice questions, there are many interesting elements to the CertLink program, such as article-based questions. At the beginning of each year, dermatologists select 8 articles from a list of those hosted by CertLink. These are recently published articles, chosen for their meaningfulness to practicing dermatologists. Each subsequent quarter, 2 of these articles are issued to the diplomate to read at his/her leisure. Once ready, participants launch and answer 2 questions about the key points of each article. The article-based questions were designed to help the practicing dermatologist stay up-to-date and relevant in personally chosen areas.

Diplomates are offered a chance to learn from any question that was missed, with explanations or resources provided to help them understand why the correct answer is correct. In this new learn-to-competence model, diplomates are not penalized the first time they answer a particular question incorrectly. Each is provided an opportunity to learn through the explanations given, and then in a future quarter, the dermatologist is given a second chance to answer a similarly themed question, with only that second chance counting toward his/her overall score.

Another unique aspect of CertLink is the allowance of time off from assessment. The ABD recognizes that life happens, and that intermittent time off from career-long assessment will be necessary to accommodate life events, including but not limited to maternity leave, other medical leave, or mental health breaks. Diplomates may take off up to 1 quarter of testing each year to accommodate such life events. Those who need extra time (beyond 1 quarter per year) would need to communicate directly with ABD to request. Those who continue to answer questions throughout the year will have their lowest-performing quarter dropped, to maximize fairness to all. Only the top 3 quarters of CertLink test performance will be counted each year when making certification status decisions. Those who take 1 quarter off will have their other 3 quarters counted toward their scoring.

How will CertLink measure performance?

At the onset of CertLink, there is no predetermined passing score. It will take a few years for the ABD psychometricians to determine an acceptable performance. Questions are written not to be tricky but rather to assess patient issues the dermatologist is likely to encounter in practice. Article-based questions are designed to assess the key points of important recent articles to advance the dermatologist’s practice.

Final Thoughts

In the end, the ABD approach to the new area of continuing certification centers on strategies to be relevant, inexpensive, and minimally disruptive to practice, and to teach to competence and advance practice by bringing forward articles that address key recent literature. We think it is a much better approach to dermatology continuing certification.

- ABD announces CertLink launch in 2020 [news release]. Newton, MA: American Board of Dermatology; 2019. https://www.abderm.org/public/announcements/certlink-2020.aspx. Accessed December 17, 2019.

- American Board of Dermatology. Focused practice improvement modules. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/abd-focused-pi-modules-for-moc.aspx. Accessed December 18, 2019.

Major changes in continuing board certification are occurring across medical specialties. On January 6, 2020, the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) launches its new web-based longitudinal assessment program called CertLink (https://abderm.mycertlink.org/).1 This new platform is designed to eventually replace the sit-down, high-stakes, once-every-10-year medical knowledge examination that dermatologists take to remain board certified. With this alternative, every participating dermatologist will receive a batch of 13 web-based questions every quarter that he/she may answer at a convenient time and place. Questions are answered one at a time or in batches, depending on the test taker’s preference, and can be completed on home or office computers (and eventually on smartphones). Participating in this type of testing does not require shutting down practice, traveling to a test center, or paying for expensive board review courses. CertLink is designed to be convenient, affordable, and relevant to an individual’s practice.

How did the ABD arrive at CertLink?

The ABD launched its original Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program in 2006. Since then, newly board-certified dermatologists, recertifying dermatologists with time-limited certificates, and time-unlimited dermatologists who volunteered to participate in MOC have experienced the dermatology MOC program. In its first 10 years, the program was met with very mixed reviews. The program was designed to assess and promote competence in a 4-part framework, including professionalism; commitment to lifelong learning and self-assessment; demonstration of knowledge, judgment, and skills; and improvement in medical practice. All 4 are areas of rational pursuit for medical professionals seeking to perform and maintain the highest quality patient care possible. But there were problems. First iterations are rarely perfect, and dermatology MOC was no exception.

At the onset, the ABD chose to oversee the MOC requirements and remained hands off in the delivery of education, relying instead on other organizations to fulfill the ABD’s requirements. Unfortunately, with limited educational offerings available, many diplomates paid notable registration fees for each qualifying MOC activity. Quality improvement activities were a relatively new experience for dermatologists and were time consuming. Required medical record reviews were onerous, often requiring more than 35 data points to be collected per medical record reviewed. The limited number and limited diversity of educational offerings also created circumstances in which the material covered was not maximally relevant to many participants. When paying to answer questions about patient populations or procedure types never encountered by the dermatologist who purchased the particular MOC activity, many asked the question “How does this make me a better doctor?” They were right to ask.

Cost, time commitment to participate in MOC, and relevance to practice were 3 key areas of concern for many dermatologists. In response to internal and external MOC feedback, in 2015 the ABD took a hard look at its 10-year experience with MOC. While contemplating its next strategies, the ABD temporarily put its component 4—practice improvement—requirements on hold. After much review, the ABD decided to take over a notable portion of the education delivery. Its goal was to provide education that would fulfill MOC requirements in a more affordable, relevant, quicker, and easier manner.

First, the ABD made the decision to assume a more notable role as educator, in part to offer qualifying activities at no additional cost to diplomates. By taking on the role as educator, 3 major changes resulted: the way ABD approached quality improvement activities, partnership to initiate a question-of-the-week self-assessment program, and initiation of a longitudinal assessment strategy that resulted in this month’s launch of CertLink.

The ABD revolutionized its quality improvement requirements with the launch of its practice improvement modules made available through its website.2 These modules utilize recently published clinical practice gaps in 5 dermatology subspecialty domains to fulfill the practice improvement requirements. Participants read a brief synopsis of the supporting literature explaining practice improvement recommendations found in the module. Next, they find 5 patients in their practice with the condition, medication, or process in question and review whether they provided the care supported by the best available evidence. No module requires more than 5 medical records to review, and no more than 3 questions are answered per medical record review. If review confirms that the care was appropriate, no further action is needed. If a care gap is identified, then participants implement changes and later remeasure practice to detect any change. This certification activity was incredibly popular with the thousands of diplomates who have participated thus far; more than 97% stated the modules were relevant to practice, 98% stated they would recommend the modules to fellow dermatologists, and nearly 25% reported the module helped to change their practice for the better (unpublished data, July 2019). Relevance had been restored.

The ABD worked closely with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) to develop new education for weekly self-assessment. The ABD created the content and delivered to the AAD the first year of material for what would become the most successful and popular dermatology CME activity in history: the AAD Question of the Week (QOW). Thousands of dermatologists are registered to receive the QOW, with very active weekly participation. Participants receive 1 self-assessment point and 0.25 CME credits for each attempted question, right or wrong. This quizzing tool also was educational, with explanation of right answers and wrong choices included. The average amount of time spent answering each question was approximately 40 seconds. American Academy of Dermatology members can participate in its QOW as a member benefit. Self-assessment is no longer a time- consuming or costly process.

The third major change was the ABD initiation of the longitudinal assessment strategy called CertLink, a web-based testing platform operated by the American Board of Medical Specialties. Longitudinal assessment differs from traditional certification and recertification assessment. It allows the test taker to answer the certification test questions over time instead of all at once. Longitudinal assessment not only provides a greater level of convenience to the test taker but also allows boards a more continuous set of touch points in the assessment of diplomates over the course of the continuing certification period.

What will be part of CertLink?

In addition to standard multiple-choice questions, there are many interesting elements to the CertLink program, such as article-based questions. At the beginning of each year, dermatologists select 8 articles from a list of those hosted by CertLink. These are recently published articles, chosen for their meaningfulness to practicing dermatologists. Each subsequent quarter, 2 of these articles are issued to the diplomate to read at his/her leisure. Once ready, participants launch and answer 2 questions about the key points of each article. The article-based questions were designed to help the practicing dermatologist stay up-to-date and relevant in personally chosen areas.

Diplomates are offered a chance to learn from any question that was missed, with explanations or resources provided to help them understand why the correct answer is correct. In this new learn-to-competence model, diplomates are not penalized the first time they answer a particular question incorrectly. Each is provided an opportunity to learn through the explanations given, and then in a future quarter, the dermatologist is given a second chance to answer a similarly themed question, with only that second chance counting toward his/her overall score.

Another unique aspect of CertLink is the allowance of time off from assessment. The ABD recognizes that life happens, and that intermittent time off from career-long assessment will be necessary to accommodate life events, including but not limited to maternity leave, other medical leave, or mental health breaks. Diplomates may take off up to 1 quarter of testing each year to accommodate such life events. Those who need extra time (beyond 1 quarter per year) would need to communicate directly with ABD to request. Those who continue to answer questions throughout the year will have their lowest-performing quarter dropped, to maximize fairness to all. Only the top 3 quarters of CertLink test performance will be counted each year when making certification status decisions. Those who take 1 quarter off will have their other 3 quarters counted toward their scoring.

How will CertLink measure performance?

At the onset of CertLink, there is no predetermined passing score. It will take a few years for the ABD psychometricians to determine an acceptable performance. Questions are written not to be tricky but rather to assess patient issues the dermatologist is likely to encounter in practice. Article-based questions are designed to assess the key points of important recent articles to advance the dermatologist’s practice.

Final Thoughts

In the end, the ABD approach to the new area of continuing certification centers on strategies to be relevant, inexpensive, and minimally disruptive to practice, and to teach to competence and advance practice by bringing forward articles that address key recent literature. We think it is a much better approach to dermatology continuing certification.

Major changes in continuing board certification are occurring across medical specialties. On January 6, 2020, the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) launches its new web-based longitudinal assessment program called CertLink (https://abderm.mycertlink.org/).1 This new platform is designed to eventually replace the sit-down, high-stakes, once-every-10-year medical knowledge examination that dermatologists take to remain board certified. With this alternative, every participating dermatologist will receive a batch of 13 web-based questions every quarter that he/she may answer at a convenient time and place. Questions are answered one at a time or in batches, depending on the test taker’s preference, and can be completed on home or office computers (and eventually on smartphones). Participating in this type of testing does not require shutting down practice, traveling to a test center, or paying for expensive board review courses. CertLink is designed to be convenient, affordable, and relevant to an individual’s practice.

How did the ABD arrive at CertLink?

The ABD launched its original Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program in 2006. Since then, newly board-certified dermatologists, recertifying dermatologists with time-limited certificates, and time-unlimited dermatologists who volunteered to participate in MOC have experienced the dermatology MOC program. In its first 10 years, the program was met with very mixed reviews. The program was designed to assess and promote competence in a 4-part framework, including professionalism; commitment to lifelong learning and self-assessment; demonstration of knowledge, judgment, and skills; and improvement in medical practice. All 4 are areas of rational pursuit for medical professionals seeking to perform and maintain the highest quality patient care possible. But there were problems. First iterations are rarely perfect, and dermatology MOC was no exception.

At the onset, the ABD chose to oversee the MOC requirements and remained hands off in the delivery of education, relying instead on other organizations to fulfill the ABD’s requirements. Unfortunately, with limited educational offerings available, many diplomates paid notable registration fees for each qualifying MOC activity. Quality improvement activities were a relatively new experience for dermatologists and were time consuming. Required medical record reviews were onerous, often requiring more than 35 data points to be collected per medical record reviewed. The limited number and limited diversity of educational offerings also created circumstances in which the material covered was not maximally relevant to many participants. When paying to answer questions about patient populations or procedure types never encountered by the dermatologist who purchased the particular MOC activity, many asked the question “How does this make me a better doctor?” They were right to ask.

Cost, time commitment to participate in MOC, and relevance to practice were 3 key areas of concern for many dermatologists. In response to internal and external MOC feedback, in 2015 the ABD took a hard look at its 10-year experience with MOC. While contemplating its next strategies, the ABD temporarily put its component 4—practice improvement—requirements on hold. After much review, the ABD decided to take over a notable portion of the education delivery. Its goal was to provide education that would fulfill MOC requirements in a more affordable, relevant, quicker, and easier manner.

First, the ABD made the decision to assume a more notable role as educator, in part to offer qualifying activities at no additional cost to diplomates. By taking on the role as educator, 3 major changes resulted: the way ABD approached quality improvement activities, partnership to initiate a question-of-the-week self-assessment program, and initiation of a longitudinal assessment strategy that resulted in this month’s launch of CertLink.

The ABD revolutionized its quality improvement requirements with the launch of its practice improvement modules made available through its website.2 These modules utilize recently published clinical practice gaps in 5 dermatology subspecialty domains to fulfill the practice improvement requirements. Participants read a brief synopsis of the supporting literature explaining practice improvement recommendations found in the module. Next, they find 5 patients in their practice with the condition, medication, or process in question and review whether they provided the care supported by the best available evidence. No module requires more than 5 medical records to review, and no more than 3 questions are answered per medical record review. If review confirms that the care was appropriate, no further action is needed. If a care gap is identified, then participants implement changes and later remeasure practice to detect any change. This certification activity was incredibly popular with the thousands of diplomates who have participated thus far; more than 97% stated the modules were relevant to practice, 98% stated they would recommend the modules to fellow dermatologists, and nearly 25% reported the module helped to change their practice for the better (unpublished data, July 2019). Relevance had been restored.

The ABD worked closely with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) to develop new education for weekly self-assessment. The ABD created the content and delivered to the AAD the first year of material for what would become the most successful and popular dermatology CME activity in history: the AAD Question of the Week (QOW). Thousands of dermatologists are registered to receive the QOW, with very active weekly participation. Participants receive 1 self-assessment point and 0.25 CME credits for each attempted question, right or wrong. This quizzing tool also was educational, with explanation of right answers and wrong choices included. The average amount of time spent answering each question was approximately 40 seconds. American Academy of Dermatology members can participate in its QOW as a member benefit. Self-assessment is no longer a time- consuming or costly process.

The third major change was the ABD initiation of the longitudinal assessment strategy called CertLink, a web-based testing platform operated by the American Board of Medical Specialties. Longitudinal assessment differs from traditional certification and recertification assessment. It allows the test taker to answer the certification test questions over time instead of all at once. Longitudinal assessment not only provides a greater level of convenience to the test taker but also allows boards a more continuous set of touch points in the assessment of diplomates over the course of the continuing certification period.

What will be part of CertLink?

In addition to standard multiple-choice questions, there are many interesting elements to the CertLink program, such as article-based questions. At the beginning of each year, dermatologists select 8 articles from a list of those hosted by CertLink. These are recently published articles, chosen for their meaningfulness to practicing dermatologists. Each subsequent quarter, 2 of these articles are issued to the diplomate to read at his/her leisure. Once ready, participants launch and answer 2 questions about the key points of each article. The article-based questions were designed to help the practicing dermatologist stay up-to-date and relevant in personally chosen areas.

Diplomates are offered a chance to learn from any question that was missed, with explanations or resources provided to help them understand why the correct answer is correct. In this new learn-to-competence model, diplomates are not penalized the first time they answer a particular question incorrectly. Each is provided an opportunity to learn through the explanations given, and then in a future quarter, the dermatologist is given a second chance to answer a similarly themed question, with only that second chance counting toward his/her overall score.

Another unique aspect of CertLink is the allowance of time off from assessment. The ABD recognizes that life happens, and that intermittent time off from career-long assessment will be necessary to accommodate life events, including but not limited to maternity leave, other medical leave, or mental health breaks. Diplomates may take off up to 1 quarter of testing each year to accommodate such life events. Those who need extra time (beyond 1 quarter per year) would need to communicate directly with ABD to request. Those who continue to answer questions throughout the year will have their lowest-performing quarter dropped, to maximize fairness to all. Only the top 3 quarters of CertLink test performance will be counted each year when making certification status decisions. Those who take 1 quarter off will have their other 3 quarters counted toward their scoring.

How will CertLink measure performance?

At the onset of CertLink, there is no predetermined passing score. It will take a few years for the ABD psychometricians to determine an acceptable performance. Questions are written not to be tricky but rather to assess patient issues the dermatologist is likely to encounter in practice. Article-based questions are designed to assess the key points of important recent articles to advance the dermatologist’s practice.

Final Thoughts

In the end, the ABD approach to the new area of continuing certification centers on strategies to be relevant, inexpensive, and minimally disruptive to practice, and to teach to competence and advance practice by bringing forward articles that address key recent literature. We think it is a much better approach to dermatology continuing certification.

- ABD announces CertLink launch in 2020 [news release]. Newton, MA: American Board of Dermatology; 2019. https://www.abderm.org/public/announcements/certlink-2020.aspx. Accessed December 17, 2019.

- American Board of Dermatology. Focused practice improvement modules. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/abd-focused-pi-modules-for-moc.aspx. Accessed December 18, 2019.

- ABD announces CertLink launch in 2020 [news release]. Newton, MA: American Board of Dermatology; 2019. https://www.abderm.org/public/announcements/certlink-2020.aspx. Accessed December 17, 2019.

- American Board of Dermatology. Focused practice improvement modules. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/abd-focused-pi-modules-for-moc.aspx. Accessed December 18, 2019.