User login

Top DEI Topics to Incorporate Into Dermatology Residency Training: An Electronic Delphi Consensus Study

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

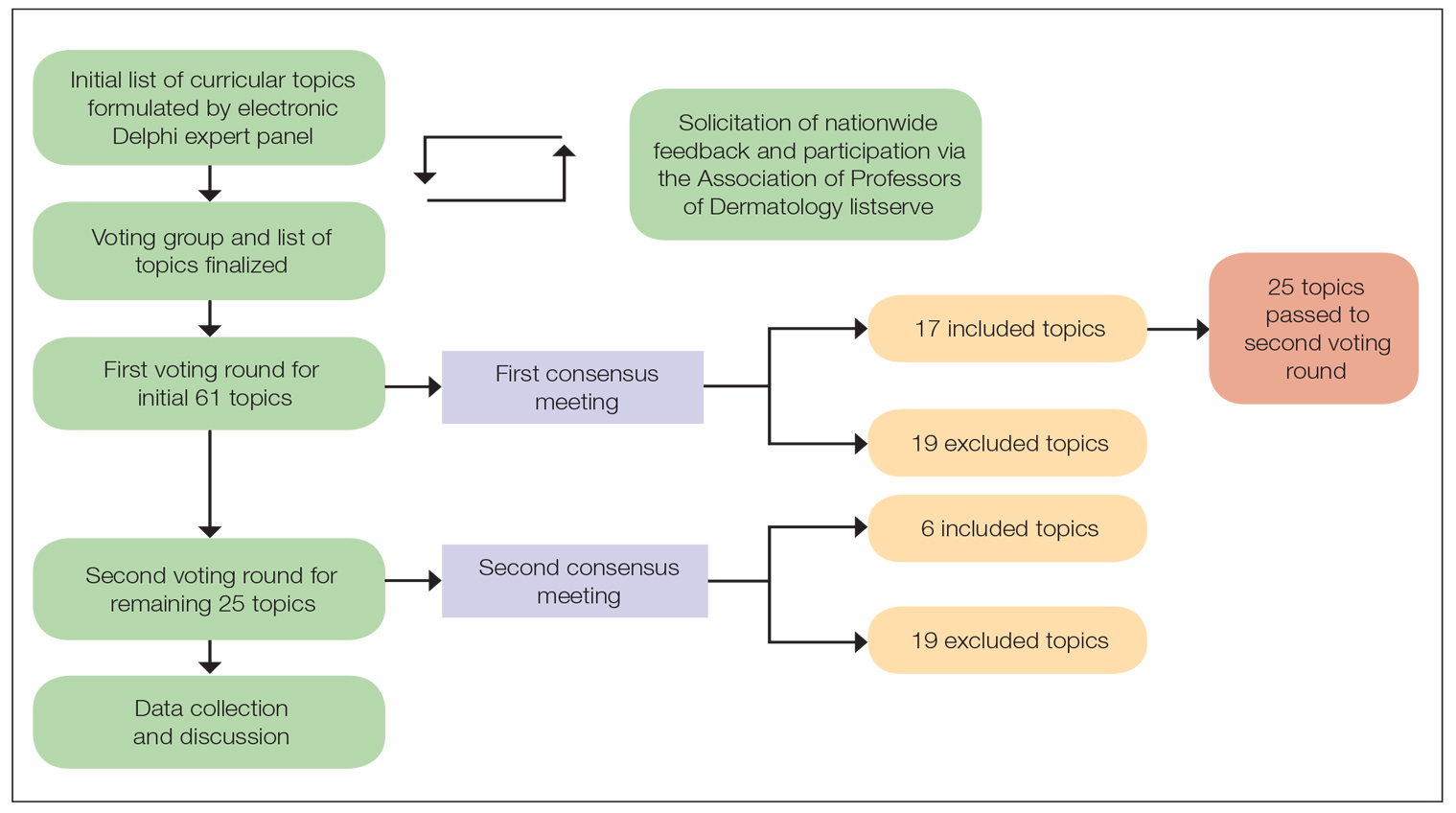

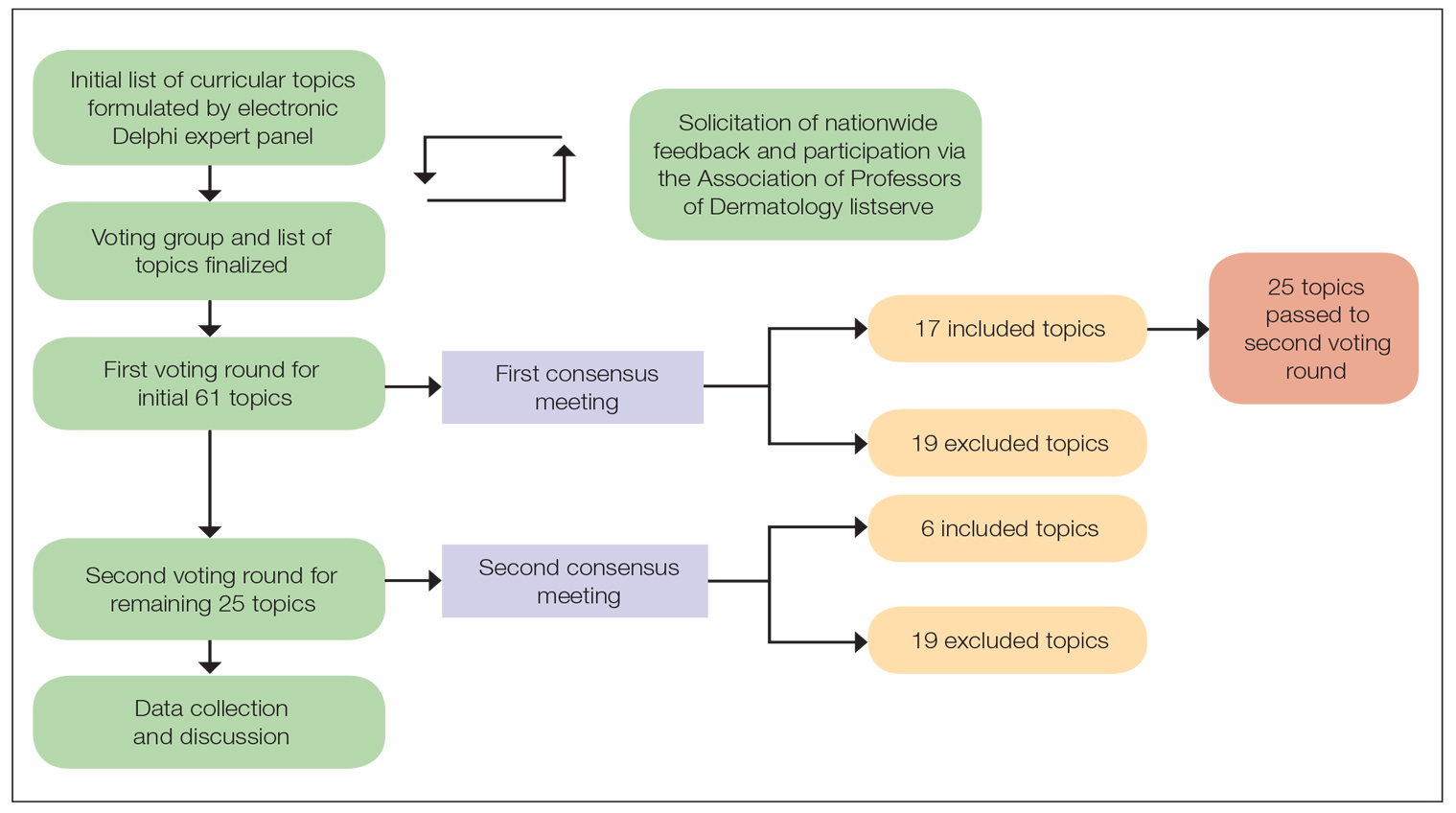

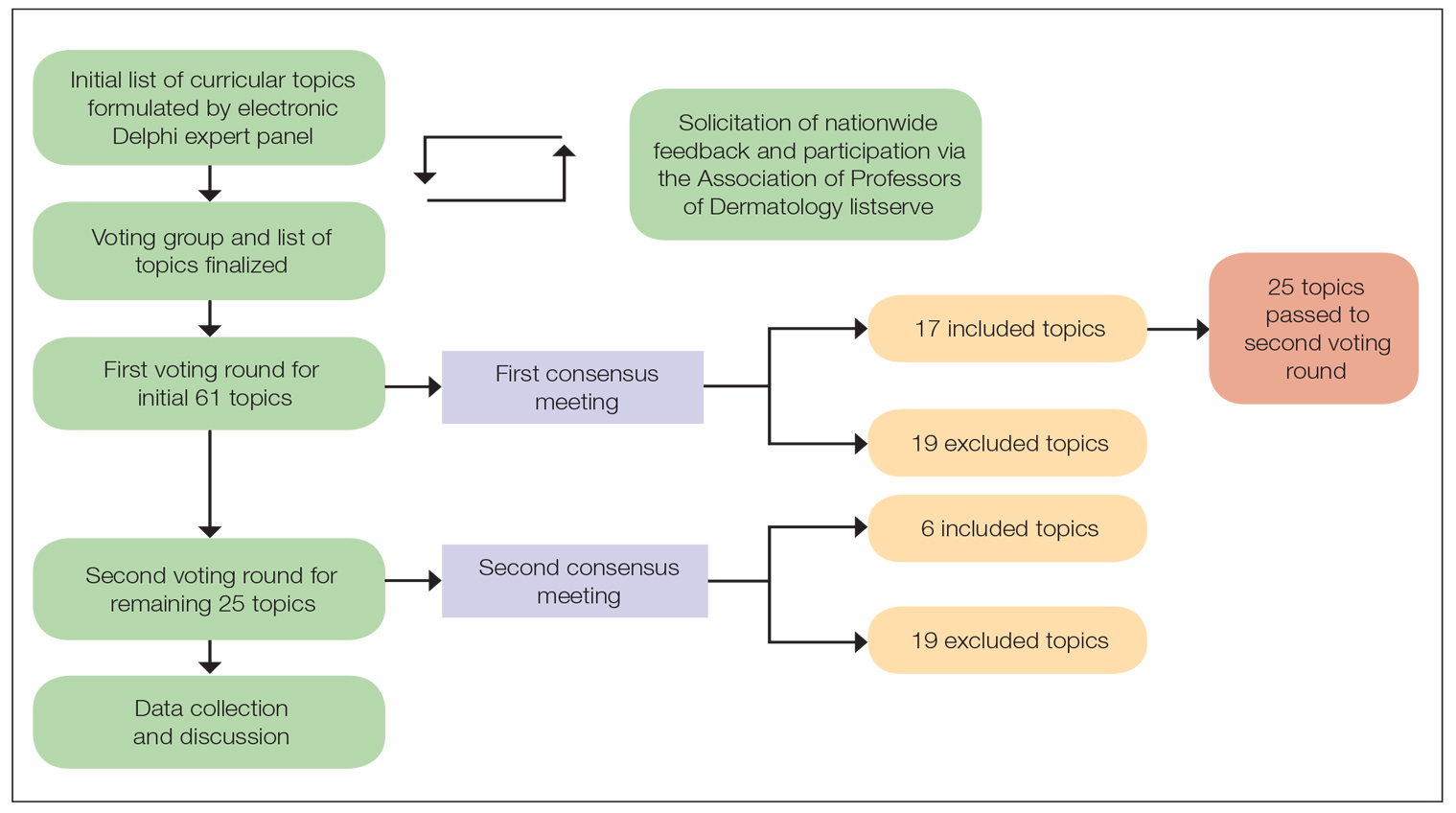

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

PRACTICE POINTS

- Advancing curricula related to diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology training can improve health outcomes, address health care workforce disparities, and enhance clinical care for diverse patient populations.

- Education on patient-centered communication, cultural humility, and the impact of social determinants of health results in dermatology residents who are better equipped with the necessary tools to effectively care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Incontinentia Pigmenti: Initial Presentation of Encephalopathy and Seizures

To the Editor:

A 7-day-old full-term infant presented to the neonatal intensive care unit with poor feeding and altered consciousness. She was born at 39 weeks and 3 days to a gravida 1 mother with a pregnancy history complicated by maternal chorioamnionitis and gestational diabetes. During labor, nonreassuring fetal heart tones and arrest of labor prompted an uncomplicated cesarean delivery with normal Apgar scores at birth. The infant’s family history revealed only beta thalassemia minor in her father. At 5 to 7 days of life, the mother noted difficulty with feeding and poor latch along with lethargy and depressed consciousness in the infant.

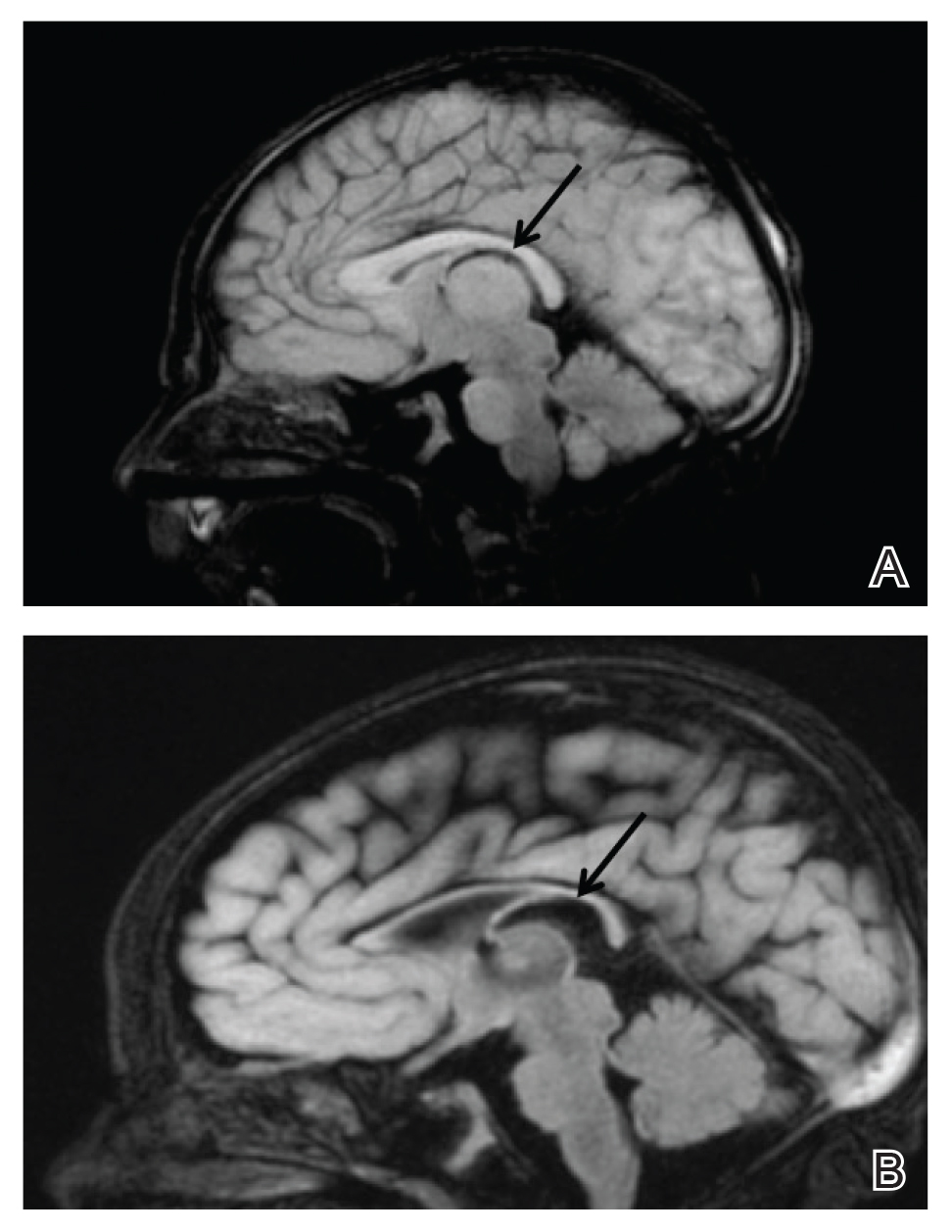

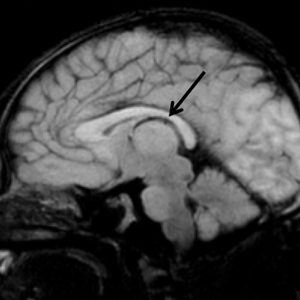

Upon arrival to the neonatal intensive care unit, the infant was noted to have rhythmic lip-smacking behavior, intermittent nystagmus, mild hypotonia, and clonic movements of the left upper extremity. An electroencephalogram was markedly abnormal, capturing multiple seizures in the bilateral cortical hemispheres. She was loaded with phenobarbital with no further seizure activity. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed innumerable punctate foci of restricted diffusion with corresponding punctate hemorrhage within the frontal and parietal white matter, as well as cortical diffusion restriction within the occipital lobe, inferior temporal lobe, bilateral thalami, and corpus callosum (Figure 1). An exhaustive infectious workup also was completed and was unremarkable, though she was treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including intravenous acyclovir.

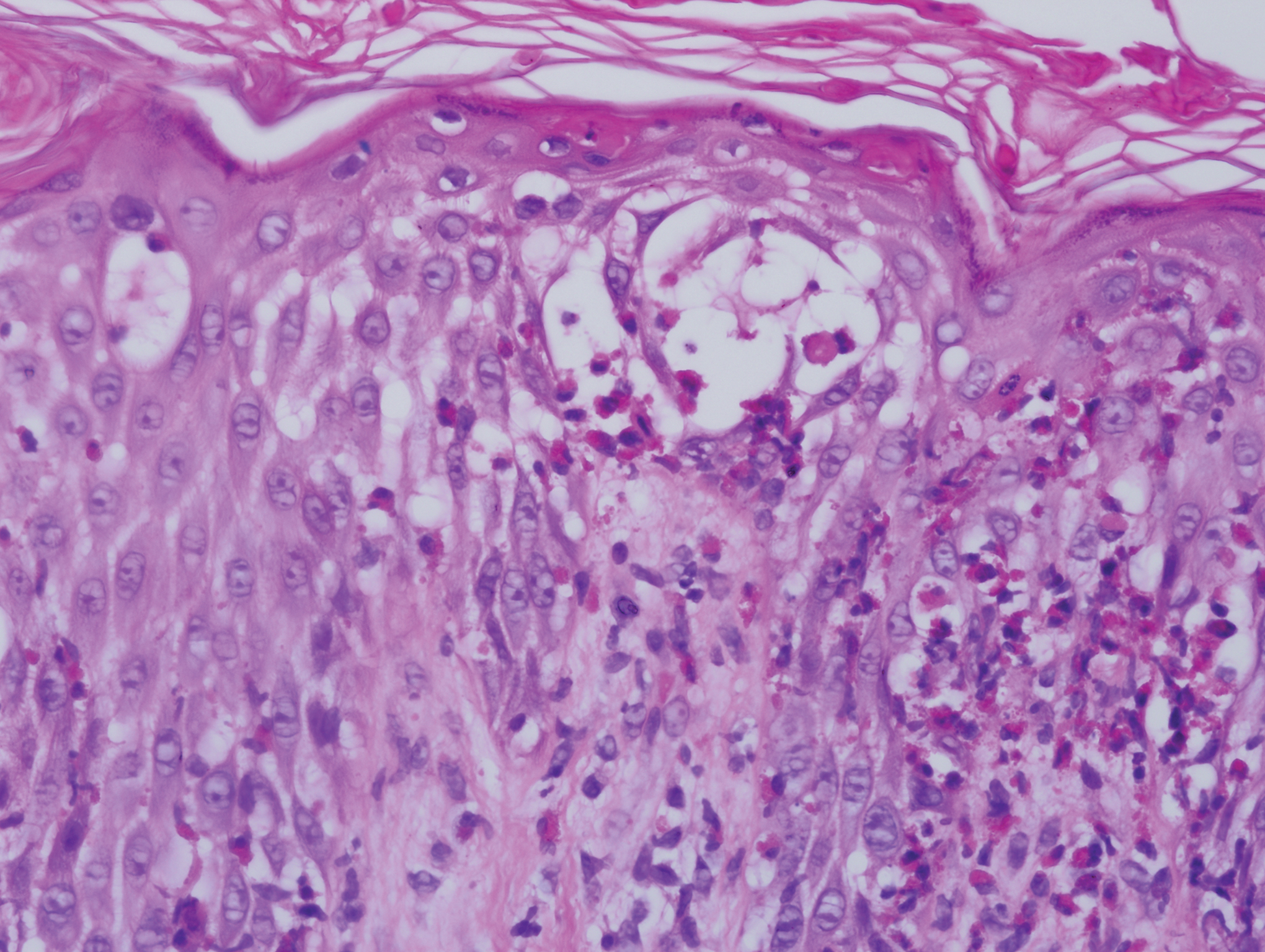

Five days after being hospitalized (day 10 of life), a vesicular rash was noted on the arms and legs (Figure 2). Discussion with the patient’s mother revealed that the first signs of unusual skin lesions occurred as early as several days prior. There were no oral mucosal lesions or gross ocular abnormalities. No nail changes were appreciated. A bedside Tzanck preparation was negative for viral cytopathic changes. A skin biopsy was performed that demonstrated eosinophilic spongiosis with necrotic keratinocytes, typical of the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP)(Figure 3). An ophthalmology examination showed an arteriovenous malformation of the right eye with subtle neovascularization at the infratemporal periphery, consistent with known ocular manifestations of IP. The infant’s mother reported no history of notable dental abnormalities, hair loss, skin rashes, or nail changes. Genetic testing demonstrated the common IKBKG (inhibitor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase gamma [formerly known as NEMO]) gene deletion on the X chromosome, consistent with IP.

She successfully underwent retinal laser ablative therapy for the ocular manifestations without further evidence of neovascularization. She developed a mild cataract that was not visually significant and required no intervention. Her brain abnormalities were thought to represent foci of necrosis with superimposed hemorrhagic transformation due to spontaneous degeneration of brain cells in which the mutated X chromosome was activated. No further treatment was indicated beyond suppression of the consequent seizures. There was no notable cortical edema or other medical indication for systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Phenobarbital was continued without further seizure events.

Several months after the initial presentation, a follow-up electroencephalogram was normal. Phenobarbital was slowly weaned and finally discontinued approximately 6 months after the initial event with no other reported seizures. She currently is achieving normal developmental milestones with the exception of slight motor delay and expected residual hypotonia.

Incontinentia pigmenti, also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is a rare multisystem neuroectodermal disorder, primarily affecting the skin, central nervous system (CNS), and retinas. The disorder can be inherited in an X-linked dominant fashion and appears almost exclusively in women with typical in utero lethality seen in males. Most affected individuals have a sporadic, or de novo, mutation, which was likely the case in our patient given that her mother demonstrated no signs or symptoms.1 The pathogenesis of disease is a defect at chromosome Xq28 that is a region encoding the nuclear factor–κB essential modulator, IKBKG. Absence or mutation of IKBKG in IP results in failure to activate nuclear factor–κB and leaves cells vulnerable to cytokine-mediated apoptosis, especially after exposure to tumor necrosis factor α.2

Clinical manifestations of IP are present at or soon after birth. The cutaneous findings of this disorder are classically described as a step-wise progression through 4 distinct stages: (1) a linear and/or whorled vesicular eruption predominantly on the extremities at birth or within the first few weeks of life; (2) thickened linear or whorled verrucous plaques; (3) hyperpigmented streaks and whorls that may or may not correspond with prior affected areas that may resolve by adolescence; and (4) hypopigmented, possibly atrophic plaques on the extremities that may persist lifelong. Importantly, not every patient will experience each of these stages. Overlap can occur, and the time course of each stage is highly variable. Other ectodermal manifestations include dental abnormalities such as small, misshaped, or missing teeth; alopecia; and nail abnormalities. Ocular abnormalities associated with IP primarily occur in the retina, including vascular occlusion, neovascularization, hemorrhages, foveal abnormalities, as well as exudative and tractional detachments.3,4

It is crucial to recognize CNS anomalies in association with the cutaneous findings of IP, as CNS pathology can be severe with profound developmental implications. Central nervous system findings have been noted to correlate with the appearance of the vesicular stage of IP. A high index of suspicion is needed, as the disease can demonstrate progression within a short time.5-8 The most frequent anomalies include seizures, motor impairment, intellectual disability, and microcephaly.9,10 Some of the most commonly identified CNS lesions on imaging include necrosis or brain infarcts, atrophy, and lesions of the corpus callosum.7

The pathogenesis of observed CNS changes in IP is not well understood. There have been numerous proposals of a vascular mechanism, and a microangiopathic process appears to be most plausible. Mutations in IKBKG may result in interruption of signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 with a consequent impact on angiogenesis, supporting a vascular mechanism. Additionally, mutations in IKBKG lead to activation of eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective chemokine.9 Eotaxin activation results in eosinophilic degranulation that mediates the classic eosinophilic infiltrate seen in the classic skin histology of IP. Additionally, it has been shown that eotaxin is strongly expressed by endothelial cells in IP, and more abundant eosinophil degranulation may play a role in mediating vaso-occlusion.7 Other studies have found that the highest expression level of the IKBKG gene is in the CNS, potentially explaining the extensive imaging findings of hemorrhage and diffusion restriction in our patient. These features likely are attributable to apoptosis of cells possessing the mutated IKBKG gene.9-11

- Ehrenreich M, Tarlow MM, Godlewska-Janusz E, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a systemic disorder. Cutis. 2007;79:355-362.

- Smahi A, Courtois G, Rabia SH, et al. The NF-kappaB signaling pathway in human diseases: from incontinentia pigmenti to ectodermal dysplasias and immune-deficiency syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2371-2375.

- O’Doherty M, McCreery K, Green AJ, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti—ophthalmological observation of a series of cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:11-16.

- Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia pigmenti: a comprehensive review and update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:650-657.

- Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:148-150.

- Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, et al. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:284-289.

- Minic´ S, Trpinac D, Obradovic´ M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:25-35.

- Wolf NI, Kramer N, Harting I, et al. Diffuse cortical necrosis in a neonate with incontinentia pigmenti and an encephalitis-like presentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1580-1582.

- Phan TA, Wargon O, Turner AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:474-480.

- Volpe J. Neurobiology of periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:553-562.

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinical and neuroimaging findings in a series of 12 patients. Neurologia. 2006;21:239-248.

To the Editor:

A 7-day-old full-term infant presented to the neonatal intensive care unit with poor feeding and altered consciousness. She was born at 39 weeks and 3 days to a gravida 1 mother with a pregnancy history complicated by maternal chorioamnionitis and gestational diabetes. During labor, nonreassuring fetal heart tones and arrest of labor prompted an uncomplicated cesarean delivery with normal Apgar scores at birth. The infant’s family history revealed only beta thalassemia minor in her father. At 5 to 7 days of life, the mother noted difficulty with feeding and poor latch along with lethargy and depressed consciousness in the infant.

Upon arrival to the neonatal intensive care unit, the infant was noted to have rhythmic lip-smacking behavior, intermittent nystagmus, mild hypotonia, and clonic movements of the left upper extremity. An electroencephalogram was markedly abnormal, capturing multiple seizures in the bilateral cortical hemispheres. She was loaded with phenobarbital with no further seizure activity. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed innumerable punctate foci of restricted diffusion with corresponding punctate hemorrhage within the frontal and parietal white matter, as well as cortical diffusion restriction within the occipital lobe, inferior temporal lobe, bilateral thalami, and corpus callosum (Figure 1). An exhaustive infectious workup also was completed and was unremarkable, though she was treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including intravenous acyclovir.

Five days after being hospitalized (day 10 of life), a vesicular rash was noted on the arms and legs (Figure 2). Discussion with the patient’s mother revealed that the first signs of unusual skin lesions occurred as early as several days prior. There were no oral mucosal lesions or gross ocular abnormalities. No nail changes were appreciated. A bedside Tzanck preparation was negative for viral cytopathic changes. A skin biopsy was performed that demonstrated eosinophilic spongiosis with necrotic keratinocytes, typical of the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP)(Figure 3). An ophthalmology examination showed an arteriovenous malformation of the right eye with subtle neovascularization at the infratemporal periphery, consistent with known ocular manifestations of IP. The infant’s mother reported no history of notable dental abnormalities, hair loss, skin rashes, or nail changes. Genetic testing demonstrated the common IKBKG (inhibitor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase gamma [formerly known as NEMO]) gene deletion on the X chromosome, consistent with IP.

She successfully underwent retinal laser ablative therapy for the ocular manifestations without further evidence of neovascularization. She developed a mild cataract that was not visually significant and required no intervention. Her brain abnormalities were thought to represent foci of necrosis with superimposed hemorrhagic transformation due to spontaneous degeneration of brain cells in which the mutated X chromosome was activated. No further treatment was indicated beyond suppression of the consequent seizures. There was no notable cortical edema or other medical indication for systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Phenobarbital was continued without further seizure events.

Several months after the initial presentation, a follow-up electroencephalogram was normal. Phenobarbital was slowly weaned and finally discontinued approximately 6 months after the initial event with no other reported seizures. She currently is achieving normal developmental milestones with the exception of slight motor delay and expected residual hypotonia.

Incontinentia pigmenti, also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is a rare multisystem neuroectodermal disorder, primarily affecting the skin, central nervous system (CNS), and retinas. The disorder can be inherited in an X-linked dominant fashion and appears almost exclusively in women with typical in utero lethality seen in males. Most affected individuals have a sporadic, or de novo, mutation, which was likely the case in our patient given that her mother demonstrated no signs or symptoms.1 The pathogenesis of disease is a defect at chromosome Xq28 that is a region encoding the nuclear factor–κB essential modulator, IKBKG. Absence or mutation of IKBKG in IP results in failure to activate nuclear factor–κB and leaves cells vulnerable to cytokine-mediated apoptosis, especially after exposure to tumor necrosis factor α.2

Clinical manifestations of IP are present at or soon after birth. The cutaneous findings of this disorder are classically described as a step-wise progression through 4 distinct stages: (1) a linear and/or whorled vesicular eruption predominantly on the extremities at birth or within the first few weeks of life; (2) thickened linear or whorled verrucous plaques; (3) hyperpigmented streaks and whorls that may or may not correspond with prior affected areas that may resolve by adolescence; and (4) hypopigmented, possibly atrophic plaques on the extremities that may persist lifelong. Importantly, not every patient will experience each of these stages. Overlap can occur, and the time course of each stage is highly variable. Other ectodermal manifestations include dental abnormalities such as small, misshaped, or missing teeth; alopecia; and nail abnormalities. Ocular abnormalities associated with IP primarily occur in the retina, including vascular occlusion, neovascularization, hemorrhages, foveal abnormalities, as well as exudative and tractional detachments.3,4

It is crucial to recognize CNS anomalies in association with the cutaneous findings of IP, as CNS pathology can be severe with profound developmental implications. Central nervous system findings have been noted to correlate with the appearance of the vesicular stage of IP. A high index of suspicion is needed, as the disease can demonstrate progression within a short time.5-8 The most frequent anomalies include seizures, motor impairment, intellectual disability, and microcephaly.9,10 Some of the most commonly identified CNS lesions on imaging include necrosis or brain infarcts, atrophy, and lesions of the corpus callosum.7

The pathogenesis of observed CNS changes in IP is not well understood. There have been numerous proposals of a vascular mechanism, and a microangiopathic process appears to be most plausible. Mutations in IKBKG may result in interruption of signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 with a consequent impact on angiogenesis, supporting a vascular mechanism. Additionally, mutations in IKBKG lead to activation of eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective chemokine.9 Eotaxin activation results in eosinophilic degranulation that mediates the classic eosinophilic infiltrate seen in the classic skin histology of IP. Additionally, it has been shown that eotaxin is strongly expressed by endothelial cells in IP, and more abundant eosinophil degranulation may play a role in mediating vaso-occlusion.7 Other studies have found that the highest expression level of the IKBKG gene is in the CNS, potentially explaining the extensive imaging findings of hemorrhage and diffusion restriction in our patient. These features likely are attributable to apoptosis of cells possessing the mutated IKBKG gene.9-11

To the Editor:

A 7-day-old full-term infant presented to the neonatal intensive care unit with poor feeding and altered consciousness. She was born at 39 weeks and 3 days to a gravida 1 mother with a pregnancy history complicated by maternal chorioamnionitis and gestational diabetes. During labor, nonreassuring fetal heart tones and arrest of labor prompted an uncomplicated cesarean delivery with normal Apgar scores at birth. The infant’s family history revealed only beta thalassemia minor in her father. At 5 to 7 days of life, the mother noted difficulty with feeding and poor latch along with lethargy and depressed consciousness in the infant.

Upon arrival to the neonatal intensive care unit, the infant was noted to have rhythmic lip-smacking behavior, intermittent nystagmus, mild hypotonia, and clonic movements of the left upper extremity. An electroencephalogram was markedly abnormal, capturing multiple seizures in the bilateral cortical hemispheres. She was loaded with phenobarbital with no further seizure activity. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed innumerable punctate foci of restricted diffusion with corresponding punctate hemorrhage within the frontal and parietal white matter, as well as cortical diffusion restriction within the occipital lobe, inferior temporal lobe, bilateral thalami, and corpus callosum (Figure 1). An exhaustive infectious workup also was completed and was unremarkable, though she was treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including intravenous acyclovir.

Five days after being hospitalized (day 10 of life), a vesicular rash was noted on the arms and legs (Figure 2). Discussion with the patient’s mother revealed that the first signs of unusual skin lesions occurred as early as several days prior. There were no oral mucosal lesions or gross ocular abnormalities. No nail changes were appreciated. A bedside Tzanck preparation was negative for viral cytopathic changes. A skin biopsy was performed that demonstrated eosinophilic spongiosis with necrotic keratinocytes, typical of the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP)(Figure 3). An ophthalmology examination showed an arteriovenous malformation of the right eye with subtle neovascularization at the infratemporal periphery, consistent with known ocular manifestations of IP. The infant’s mother reported no history of notable dental abnormalities, hair loss, skin rashes, or nail changes. Genetic testing demonstrated the common IKBKG (inhibitor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase gamma [formerly known as NEMO]) gene deletion on the X chromosome, consistent with IP.

She successfully underwent retinal laser ablative therapy for the ocular manifestations without further evidence of neovascularization. She developed a mild cataract that was not visually significant and required no intervention. Her brain abnormalities were thought to represent foci of necrosis with superimposed hemorrhagic transformation due to spontaneous degeneration of brain cells in which the mutated X chromosome was activated. No further treatment was indicated beyond suppression of the consequent seizures. There was no notable cortical edema or other medical indication for systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Phenobarbital was continued without further seizure events.

Several months after the initial presentation, a follow-up electroencephalogram was normal. Phenobarbital was slowly weaned and finally discontinued approximately 6 months after the initial event with no other reported seizures. She currently is achieving normal developmental milestones with the exception of slight motor delay and expected residual hypotonia.

Incontinentia pigmenti, also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is a rare multisystem neuroectodermal disorder, primarily affecting the skin, central nervous system (CNS), and retinas. The disorder can be inherited in an X-linked dominant fashion and appears almost exclusively in women with typical in utero lethality seen in males. Most affected individuals have a sporadic, or de novo, mutation, which was likely the case in our patient given that her mother demonstrated no signs or symptoms.1 The pathogenesis of disease is a defect at chromosome Xq28 that is a region encoding the nuclear factor–κB essential modulator, IKBKG. Absence or mutation of IKBKG in IP results in failure to activate nuclear factor–κB and leaves cells vulnerable to cytokine-mediated apoptosis, especially after exposure to tumor necrosis factor α.2

Clinical manifestations of IP are present at or soon after birth. The cutaneous findings of this disorder are classically described as a step-wise progression through 4 distinct stages: (1) a linear and/or whorled vesicular eruption predominantly on the extremities at birth or within the first few weeks of life; (2) thickened linear or whorled verrucous plaques; (3) hyperpigmented streaks and whorls that may or may not correspond with prior affected areas that may resolve by adolescence; and (4) hypopigmented, possibly atrophic plaques on the extremities that may persist lifelong. Importantly, not every patient will experience each of these stages. Overlap can occur, and the time course of each stage is highly variable. Other ectodermal manifestations include dental abnormalities such as small, misshaped, or missing teeth; alopecia; and nail abnormalities. Ocular abnormalities associated with IP primarily occur in the retina, including vascular occlusion, neovascularization, hemorrhages, foveal abnormalities, as well as exudative and tractional detachments.3,4

It is crucial to recognize CNS anomalies in association with the cutaneous findings of IP, as CNS pathology can be severe with profound developmental implications. Central nervous system findings have been noted to correlate with the appearance of the vesicular stage of IP. A high index of suspicion is needed, as the disease can demonstrate progression within a short time.5-8 The most frequent anomalies include seizures, motor impairment, intellectual disability, and microcephaly.9,10 Some of the most commonly identified CNS lesions on imaging include necrosis or brain infarcts, atrophy, and lesions of the corpus callosum.7

The pathogenesis of observed CNS changes in IP is not well understood. There have been numerous proposals of a vascular mechanism, and a microangiopathic process appears to be most plausible. Mutations in IKBKG may result in interruption of signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 with a consequent impact on angiogenesis, supporting a vascular mechanism. Additionally, mutations in IKBKG lead to activation of eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective chemokine.9 Eotaxin activation results in eosinophilic degranulation that mediates the classic eosinophilic infiltrate seen in the classic skin histology of IP. Additionally, it has been shown that eotaxin is strongly expressed by endothelial cells in IP, and more abundant eosinophil degranulation may play a role in mediating vaso-occlusion.7 Other studies have found that the highest expression level of the IKBKG gene is in the CNS, potentially explaining the extensive imaging findings of hemorrhage and diffusion restriction in our patient. These features likely are attributable to apoptosis of cells possessing the mutated IKBKG gene.9-11

- Ehrenreich M, Tarlow MM, Godlewska-Janusz E, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a systemic disorder. Cutis. 2007;79:355-362.

- Smahi A, Courtois G, Rabia SH, et al. The NF-kappaB signaling pathway in human diseases: from incontinentia pigmenti to ectodermal dysplasias and immune-deficiency syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2371-2375.

- O’Doherty M, McCreery K, Green AJ, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti—ophthalmological observation of a series of cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:11-16.

- Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia pigmenti: a comprehensive review and update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:650-657.

- Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:148-150.

- Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, et al. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:284-289.

- Minic´ S, Trpinac D, Obradovic´ M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:25-35.

- Wolf NI, Kramer N, Harting I, et al. Diffuse cortical necrosis in a neonate with incontinentia pigmenti and an encephalitis-like presentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1580-1582.

- Phan TA, Wargon O, Turner AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:474-480.

- Volpe J. Neurobiology of periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:553-562.

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinical and neuroimaging findings in a series of 12 patients. Neurologia. 2006;21:239-248.

- Ehrenreich M, Tarlow MM, Godlewska-Janusz E, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a systemic disorder. Cutis. 2007;79:355-362.

- Smahi A, Courtois G, Rabia SH, et al. The NF-kappaB signaling pathway in human diseases: from incontinentia pigmenti to ectodermal dysplasias and immune-deficiency syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2371-2375.

- O’Doherty M, McCreery K, Green AJ, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti—ophthalmological observation of a series of cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:11-16.

- Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia pigmenti: a comprehensive review and update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:650-657.

- Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:148-150.

- Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, et al. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:284-289.

- Minic´ S, Trpinac D, Obradovic´ M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:25-35.

- Wolf NI, Kramer N, Harting I, et al. Diffuse cortical necrosis in a neonate with incontinentia pigmenti and an encephalitis-like presentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1580-1582.

- Phan TA, Wargon O, Turner AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:474-480.

- Volpe J. Neurobiology of periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:553-562.

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinical and neuroimaging findings in a series of 12 patients. Neurologia. 2006;21:239-248.

Practice Points

- Central nervous system involvement in incontinentia pigmenti (IP) may be profound and can present prior to the classic cutaneous findings.

- A high index of suspicion for IP should be maintained in neonatal vesicular eruptions of unclear etiology, especially in the setting of unexplained seizures and/or abnormal brain imaging.