User login

Leveraging the Outpatient Pharmacy to Reduce Medication Waste in Pediatric Asthma Hospitalizations

Asthma results in approximately 125,000 hospitalizations for children annually in the United States.1,2 The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines recommend that children with persistent asthma be treated with a daily controller medication, ie, an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS).3 Hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation provides an opportunity to optimize daily controller medications and improve disease self-management by providing access to medications and teaching appropriate use of complicated inhalation devices.

To reduce readmission4 by mitigating low rates of postdischarge filling of ICS prescriptions,5,6 a strategy of “meds-in-hand” was implemented at discharge. “Meds-in-hand” mitigates medication access as a barrier to adherence by ensuring that patients are discharged from the hospital with all required medications in hand, removing any barriers to filling their initial prescriptions.7 The Asthma Improvement Collaborative at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) previously applied quality improvement methodology to implement “meds-in-hand” as a key intervention in a broad strategy that successfully reduced asthma-specific utilization for the 30-day period following an asthma-related hospitalization of publicly insured children from 12% to 7%.8,9

At the onset of the work described in this manuscript, children hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of persistent asthma were most often treated with an ICS while inpatients in addition to a standard short course of oral systemic corticosteroids. Conceptually, inpatient administration of ICS provided the opportunity to teach effective device usage with each inpatient administration and to reinforce daily use of the ICS as part of the patient’s daily home medication regimen. However, a proportion of patients admitted for an asthma exacerbation were noted to receive more than one ICS inhaler during their admission, most commonly due to a change in dose or type of ICS. When this occurred, the initially dispensed inhaler was discarded despite weeks of potential doses remaining. While some hospitals preferentially dispense ICS devices marketed to institutions with fewer doses per device, our pharmacy primarily dispensed ICS devices identical to retail locations containing at least a one-month supply of medication. In addition to the wasted medication, this practice resulted in additional work by healthcare staff, unnecessary patient charges, and potentially contributed to confusion about the discharge medication regimen.

Our specific aim for this quality improvement study was to reduce the monthly percentage of admissions for an acute asthma exacerbation treated with >1 ICS from 7% to 4% over a six-month period.

METHODS

Context

CCHMC is a quaternary care pediatric health system with more than 600 inpatient beds and 800-900 inpatient admissions per year for acute asthma exacerbation. The Hospital Medicine service cares for patients with asthma on five clinical teams across two different campuses. Care teams are supervised by an attending physician and may include residents, fellows, or nurse practitioners. Patients hospitalized for an acute asthma exacerbation may receive a consult from the Asthma Center consult team, staffed by faculty from either the Pediatric Pulmonology or Allergy/Immunology divisions. Respiratory therapists (RTs) administer inhaled medications and provide asthma education.

Planning the Intervention

Our improvement team included physicians from Hospital Medicine and Pulmonary Medicine, an Asthma Education Coordinator, a Clinical Pharmacist, a Pediatric Chief Resident, and a clinical research coordinator. Initial interventions targeted a single resident team at the main campus before spreading improvement activities to all resident teams at the main campus and then the satellite campus by February 2017.

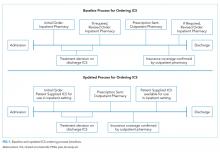

Development of our process map (Figure 1) revealed that the decision for ordering inpatient ICS treatment frequently occurred at admission. Subsequently, the care team or consulting team might make a change in the ICS to fine-tune the outpatient medication regimen given that admission for asthma often results from suboptimal chronic symptom control. Baseline analysis of changes in ICS orders revealed that 81% of ICS changes were associated with a step-up in therapy, defined as an increase in the daily dose of the ICS or the addition of a long-acting beta-agonist. The other common ICS adjustment, accounting for 17%, was a change in corticosteroid without a step-up in therapy, (ie, beclomethasone to fluticasone) that typically occurred near the end of the hospitalization to accommodate outpatient insurance formularies, independent of patient factors related to illness severity.

We utilized the model for improvement and sought to decrease the number of patients administered more than one ICS during an admission through a step-wise quality improvement approach, utilizing plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles.10 This study was reviewed and designated as not human subjects research by the CCHMC institutional review board.

Improvement Activities

We conceived key drivers or domains that would be necessary to address to effect change. Key drivers included a standardized process for delayed initiation of ICS and confirmation of outpatient insurance prescription drug coverage, prescriber education, and real-time failure notification.

PDSA Interventions

PDSA 1 & 2: Standardized Process for Initiation of ICS

Our initial tests of change targeted the timing of when an ICS was ordered during hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation. Providers were instructed to delay ordering an ICS until the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours and to include a standardized communication prompt within the albuterol order. The prompt instructed the RT to contact the provider once the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours and ask for an ICS order, if appropriate. This intervention was abandoned because it did not reliably occur.

The subsequent intervention delayed the start of ICS treatment by using a PRN indication advising that the ICS was to be administered once the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours. However, after an error resulted in the PRN indication being included on a discharge prescription for an ICS, the PRN indication was abandoned. Subsequent work to develop a standardized process for delayed initiation of ICS occurred as part of the workflow to address the confirmation of outpatient formulary coverage as described next.

PDSA 3: Prioritize the Use of the Institution’s Outpatient Pharmacy

Medication changes that occurred because of outpatient insurance formulary denials were a unique challenge; they required a medication change after the discharge treatment plan had been finalized, and a prescription was already submitted to the outpatient pharmacy. In addition, neither our inpatient electronic medical record nor our inpatient hospital pharmacy has access to decision support tools that incorporate outpatient prescription formulary coverage. Alternatively, outpatient pharmacies have a standard workflow that routinely confirms insurance coverage before dispensing medication. The institutional policy was modified to allow for the inpatient administration of patient-supplied medications, pursuant to an inpatient order. Patient-supplied medications include those brought from home or those supplied by the outpatient pharmacy.

Subsequently, we developed a standardized process to confirm outpatient prescription drug coverage by using our hospital-based outpatient pharmacy to dispense ICS for inpatient treatment and asthma education. This new workflow included placing an order for an ICS at admission as a patient-supplied medication with an administration comment to “please administer once available from the outpatient pharmacy” (Figure 1). Then, once the discharge medication plan is finalized, the prescription is submitted to the outpatient pharmacy. Following verification of insurance coverage, the outpatient pharmacy dispenses the ICS, allowing it to be used for patient education and inpatient administration. If the patient is ineligible to have their prescription filled by the outpatient pharmacy for reasons other than formulary coverage, the ICS is dispensed from the hospital inpatient pharmacy as per the previous standard workflow. Inpatient ICS inhalers are then relabeled for home use per the existing practice to support medications-in-hand.

Further workflow improvements occurred following the development of an algorithm to help the outpatient pharmacy contact the correct inpatient team, and augmentation of the medication delivery process included notification of the RT when the ICS was delivered to the inpatient unit.

PDSA 4: Prescriber Education

Prescribers received education regarding PDSA interventions before testing and throughout the improvement cycle. Education sessions included informal coaching by the Asthma Education Coordinator, e-mail reminders containing screenshots of the ordering process, and formal didactic sessions for ordering providers. The Asthma Education Coordinator also provided education to the nursing and respiratory therapy staff regarding the implemented process and workflow changes.

PDSA 5: Real-Time Failure Notification

To supplement education for the complicated process change, the improvement team utilized a decision support tool (Vigilanz Corp., Chicago, IL) linked to EMR data to provide notification of real-time process failures. When a patient with an admission diagnosis of asthma had a prescription for an ICS verified and dispensed by the inpatient pharmacy, an automated message with relevant patient information would be sent to a member of the improvement team. Following a brief chart review, directed feedback could be offered to the ordering provider, allowing the prescription to be redirected to the outpatient pharmacy.

Study of the Improvement

Patients of all ages, with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Tenth Revision codes for asthma (493.xx or J45.xx) were included in data collection and analysis if they were treated by the Hospital Medicine service, as the first inpatient service or after transfer from the ICU, and prescribed an ICS with or without a long-acting beta-agonist. Data were collected retrospectively and aggregated monthly. The baseline period was from January 2015 through October 2016. The intervention period was from November 2016 through March 2018. The prolonged baseline and study periods were utilized to understand the seasonal nature of asthma exacerbations.

Measures

Our primary outcome measure was defined as the monthly number of patients admitted to Hospital Medicine for an acute asthma exacerbation administered more than one ICS divided by the total number of asthma patients administered at least one dose of an ICS (patient-supplied or dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy). A full list of ICS is included in the appendix Table.

A secondary process measure approximated our adherence to obtaining ICS from the outpatient pharmacy for inpatient use. All medications administered during hospitalization are documented in the medication administration report. However, only medications dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy are associated with a patient charge. Patient-supplied medications, including those dispensed from the hospital outpatient pharmacy, are not associated with an inpatient charge. Therefore, the secondary process measure was defined as the monthly number of asthma patients administered an ICS not associated with an inpatient charge divided by the total number of asthma patients administered an ICS.

A cost outcome measure was developed to track changes in the average cost of an ICS included on inpatient bills during hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation. This outcome measure was defined as the total monthly cost, using the average wholesale price, of the ICS included on the inpatient bill for an asthma exacerbation, divided by the total number of asthma patients administered at least one dose of an ICS (patient supplied or dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy).

Our a priori intent was to reduce ICS medication waste while maintaining a highly reliable system that included inpatient administration and education with ICS devices and maintain our medications-in-hand practice. A balancing measure was developed to monitor the reliability of inpatient administration of ICS. It was defined as the monthly number of patients who received a discharge prescription for an ICS and were administered an ICS while an inpatient divided by the total number of asthma patients with a discharge prescription for an ICS.

Analysis

Measures were evaluated using statistical process control charts and special cause variation was determined by previously established rules. Our primary, secondary, and balancing measures were all evaluated using a p-chart with variable subgroup size. The cost outcome measure was evaluated using an X-bar S control chart.11-13

RESULTS

Primary Outcome Measure

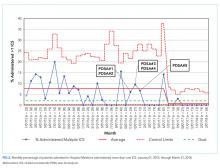

During the baseline period, 7.4% of patients admitted to Hospital Medicine for an acute asthma exacerbation were administered more than one ICS, ranging from 0%-20% of patients per month (Figure 2). Following the start of our interventions, we met criteria for special cause allowing adjustment of the centerline.13 The mean percentage of patients receiving more than one ICS decreased from 7.4% to 0.7%. Figure 2 includes the n-value displayed each month and represents all patients admitted to the Hospital Medicine service with an asthma exacerbation who were administered at least one ICS.

Secondary Process Measure

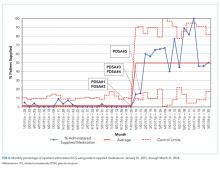

During the baseline period, there were only rare occurrences (less than 1%) of a patient-supplied ICS being administered during an asthma admission. Following the start of our intervention period, the frequency of inpatient administration of patient-supplied ICS showed a rapid increase and met rules for special cause with an increase in the mean percent from 0.7% to 50% (Figure 3). The n-value displayed each month represents all patients admitted to the Hospital Medicine service for an asthma exacerbation administered at least one ICS.

Cost Outcome Measure

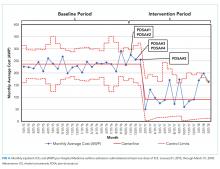

The average cost of an ICS billed during hospitalization for an acute asthma exacerbation was $236.57 per ICS during the baseline period. After the intervention period, the average inpatient cost for ICS decreased by 62% to $90.25 per ICS (Figure 4).

Balancing Measure

DISCUSSION

Our team reduced the monthly percent of children hospitalized with an acute asthma exacerbation administered more than one ICS from 7.4% to 0.7% after implementation of a new workflow process for ordering ICS utilizing the hospital-based outpatient pharmacy. The new workflow delayed ordering and administration of the initial inpatient ICS treatment, allowing time to consider a step-up in therapy. The brief delay in initiating ICS is not expected to have clinical consequence given the concomitant treatment with systemic corticosteroids. In addition, the outpatient pharmacy was utilized to verify insurance coverage reliably prior to dispensing ICS, reducing medication waste, and discharge delays due to outpatient medication formulary conflicts.

Our hospital’s previous approach to inpatient asthma care resulted in a highly reliable process to ensure patients were discharged with medications-in-hand as part of a broader system that effectively decreased reutilization. However, the previous process inadvertently resulted in medication waste. This waste included nearly full inhalers being discarded, additional work by the healthcare team (ordering providers, pharmacists, and RTs), and unnecessary patient charges.

While the primary driver of our decision to use the outpatient pharmacy was to adjudicate insurance prescription coverage reliably to prevent waste, this change likely resulted in a financial benefit to patients. The average cost per asthma admission of an inpatient billed for ICS using the average wholesale price, decreased by 62% following our interventions. The decrease in cost was primarily driven by using patient-supplied medications, including prescriptions newly filled by the on-site outpatient pharmacy, whose costs were not captured in this measure. While our secondary measure may underestimate the total expense incurred by families for an ICS, families likely receive their medications at a lower cost from the outpatient pharmacy than if the ICS was provided by an inpatient pharmacy. The average wholesale price is not what families are charged or pay for medications, partly due to differences in overhead costs that result in inpatient pharmacies having significantly higher charges than outpatient pharmacies. In addition, the 6.7% absolute reduction of our primary measure resulted in direct savings by reducing inpatient medication waste. Our process results in 67 fewer wasted ICS devices ($15,960) per 1,000 admissions for asthma exacerbation, extrapolated using the average cost ($238.20, average wholesale price) of each ICS during the baseline period.

Our quality improvement study had several limitations. (1) The interventions occurred at a single center with an established culture that embraces quality improvement, which may limit the generalizability of the work. (2) Our process verified insurance coverage with a hospital-based outpatient pharmacy. Some ICS prescriptions continued to be dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy, limiting our ability to verify insurance coverage. Local factors, including regulatory restrictions and delivery requirements, may limit the generalizability of using an outpatient pharmacy in this manner. (3) We achieved our goal of decreasing medication waste, but our a priori goal was to maintain our commitment to our established practice of interactive patient education with an ICS device as well as medications-in-hand at time of discharge. Our balancing measure showed a decrease in the percent of patients with a discharge prescription for an ICS who also received an inpatient dose of that ICS. This implies a decreased fidelity in our previously established education protocols. We had postulated that this occurred when the patient-supplied medication arrived on the day of discharge, but not close to when the medication was scheduled on the medication administration report, preventing administration. However, this is not a direct measure of patients receiving medications-in-hand or interactive medication education. Both may have occurred without administration of the ICS. (4) Despite a hospital culture that embraces quality improvement, this project required a significant change in the workflow that required considerable education at the time of implementation to integrate the new process reliably. However, once the process was in place, we have been able to sustain our improvement with limited educational investment.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementation of a new process for ordering ICS that emphasized delaying treatment until all necessary information was available and using an outpatient pharmacy to confirm insurance formulary coverage reduced the waste associated with more than one ICS being prescribed during a single admission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sally Pope, MPH and Dr. Michael Carlisle, MD for their contribution to the quality improvement project. Thank you to Drs. Karen McDowell, MD and Carolyn Kercsmar, MD for advisement of our quality improvement project.

The authors appreciate the following individuals for their invaluable contributions. Dr. Hoefgen conceptualized and designed the study, was a member of the primary improvement team, carried out initial analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs. Jones and Torres Garcia, and Mr. Hare were members of the primary improvement team who contributed to the design of the quality improvement study and interventions, ongoing data interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. Courter contributed to the conceptualization and designed the study, was a member of the primary improvement team, designed data collection instruments, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Simmons conceptualized and designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclaimer

The information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the BHPR, HRSA, DHHS, or the U.S. Government.

1. Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing trends in asthma prevalence among children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20152354. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2354.

2. HCUP Databases. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). www.hcup.us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp. Published 2016. Accessed September 14, 2016.

3. NHLBI. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):S94-S138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029.

4. Kenyon CC, Rubin DM, Zorc JJ, Mohamad Z, Faerber JA, Feudtner C. Childhood asthma hospital discharge medication fills and risk of subsequent readmission. J Pediatr. 2015;166(5):1121-1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.019.

5. Bollinger ME, Mudd KE, Boldt A, Hsu VD, Tsoukleris MG, Butz AM. Prescription fill patterns in underserved children with asthma receiving subspecialty care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(3):185-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.009.

6. Cooper WO, Hickson GB. Corticosteroid prescription filling for children covered by Medicaid following an emergency department visit or a hospitalization for asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(10):1111-1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.155.10.1111.

7. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing medication possession at discharge for patients with asthma: the Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461-e20150461. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0461.

8. Kercsmar CM, Beck AF, Sauers-Ford H, et al. Association of an asthma improvement collaborative with health care utilization in medicaid-insured pediatric patients in an urban community. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1072-1080. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2600.

9. Sauers HS, Beck AF, Kahn RS, Simmons JM. Increasing recruitment rates in an inpatient clinical research study using quality improvement methods. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(6):335-341. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0072.

10. Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009.

11. Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(6):458-464. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.6.458.

12. Mohammed MA, Panesar JS, Laney DB, Wilson R. Statistical process control charts for attribute data involving very large sample sizes: a review of problems and solutions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(4):362-368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001373.

13. Moen R, Nolan T, Provost L. Quality Improvement through Planned Experimentation. 2nd ed. New York City: McGraw-Hill Professional; 1998.

Asthma results in approximately 125,000 hospitalizations for children annually in the United States.1,2 The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines recommend that children with persistent asthma be treated with a daily controller medication, ie, an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS).3 Hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation provides an opportunity to optimize daily controller medications and improve disease self-management by providing access to medications and teaching appropriate use of complicated inhalation devices.

To reduce readmission4 by mitigating low rates of postdischarge filling of ICS prescriptions,5,6 a strategy of “meds-in-hand” was implemented at discharge. “Meds-in-hand” mitigates medication access as a barrier to adherence by ensuring that patients are discharged from the hospital with all required medications in hand, removing any barriers to filling their initial prescriptions.7 The Asthma Improvement Collaborative at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) previously applied quality improvement methodology to implement “meds-in-hand” as a key intervention in a broad strategy that successfully reduced asthma-specific utilization for the 30-day period following an asthma-related hospitalization of publicly insured children from 12% to 7%.8,9

At the onset of the work described in this manuscript, children hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of persistent asthma were most often treated with an ICS while inpatients in addition to a standard short course of oral systemic corticosteroids. Conceptually, inpatient administration of ICS provided the opportunity to teach effective device usage with each inpatient administration and to reinforce daily use of the ICS as part of the patient’s daily home medication regimen. However, a proportion of patients admitted for an asthma exacerbation were noted to receive more than one ICS inhaler during their admission, most commonly due to a change in dose or type of ICS. When this occurred, the initially dispensed inhaler was discarded despite weeks of potential doses remaining. While some hospitals preferentially dispense ICS devices marketed to institutions with fewer doses per device, our pharmacy primarily dispensed ICS devices identical to retail locations containing at least a one-month supply of medication. In addition to the wasted medication, this practice resulted in additional work by healthcare staff, unnecessary patient charges, and potentially contributed to confusion about the discharge medication regimen.

Our specific aim for this quality improvement study was to reduce the monthly percentage of admissions for an acute asthma exacerbation treated with >1 ICS from 7% to 4% over a six-month period.

METHODS

Context

CCHMC is a quaternary care pediatric health system with more than 600 inpatient beds and 800-900 inpatient admissions per year for acute asthma exacerbation. The Hospital Medicine service cares for patients with asthma on five clinical teams across two different campuses. Care teams are supervised by an attending physician and may include residents, fellows, or nurse practitioners. Patients hospitalized for an acute asthma exacerbation may receive a consult from the Asthma Center consult team, staffed by faculty from either the Pediatric Pulmonology or Allergy/Immunology divisions. Respiratory therapists (RTs) administer inhaled medications and provide asthma education.

Planning the Intervention

Our improvement team included physicians from Hospital Medicine and Pulmonary Medicine, an Asthma Education Coordinator, a Clinical Pharmacist, a Pediatric Chief Resident, and a clinical research coordinator. Initial interventions targeted a single resident team at the main campus before spreading improvement activities to all resident teams at the main campus and then the satellite campus by February 2017.

Development of our process map (Figure 1) revealed that the decision for ordering inpatient ICS treatment frequently occurred at admission. Subsequently, the care team or consulting team might make a change in the ICS to fine-tune the outpatient medication regimen given that admission for asthma often results from suboptimal chronic symptom control. Baseline analysis of changes in ICS orders revealed that 81% of ICS changes were associated with a step-up in therapy, defined as an increase in the daily dose of the ICS or the addition of a long-acting beta-agonist. The other common ICS adjustment, accounting for 17%, was a change in corticosteroid without a step-up in therapy, (ie, beclomethasone to fluticasone) that typically occurred near the end of the hospitalization to accommodate outpatient insurance formularies, independent of patient factors related to illness severity.

We utilized the model for improvement and sought to decrease the number of patients administered more than one ICS during an admission through a step-wise quality improvement approach, utilizing plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles.10 This study was reviewed and designated as not human subjects research by the CCHMC institutional review board.

Improvement Activities

We conceived key drivers or domains that would be necessary to address to effect change. Key drivers included a standardized process for delayed initiation of ICS and confirmation of outpatient insurance prescription drug coverage, prescriber education, and real-time failure notification.

PDSA Interventions

PDSA 1 & 2: Standardized Process for Initiation of ICS

Our initial tests of change targeted the timing of when an ICS was ordered during hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation. Providers were instructed to delay ordering an ICS until the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours and to include a standardized communication prompt within the albuterol order. The prompt instructed the RT to contact the provider once the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours and ask for an ICS order, if appropriate. This intervention was abandoned because it did not reliably occur.

The subsequent intervention delayed the start of ICS treatment by using a PRN indication advising that the ICS was to be administered once the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours. However, after an error resulted in the PRN indication being included on a discharge prescription for an ICS, the PRN indication was abandoned. Subsequent work to develop a standardized process for delayed initiation of ICS occurred as part of the workflow to address the confirmation of outpatient formulary coverage as described next.

PDSA 3: Prioritize the Use of the Institution’s Outpatient Pharmacy

Medication changes that occurred because of outpatient insurance formulary denials were a unique challenge; they required a medication change after the discharge treatment plan had been finalized, and a prescription was already submitted to the outpatient pharmacy. In addition, neither our inpatient electronic medical record nor our inpatient hospital pharmacy has access to decision support tools that incorporate outpatient prescription formulary coverage. Alternatively, outpatient pharmacies have a standard workflow that routinely confirms insurance coverage before dispensing medication. The institutional policy was modified to allow for the inpatient administration of patient-supplied medications, pursuant to an inpatient order. Patient-supplied medications include those brought from home or those supplied by the outpatient pharmacy.

Subsequently, we developed a standardized process to confirm outpatient prescription drug coverage by using our hospital-based outpatient pharmacy to dispense ICS for inpatient treatment and asthma education. This new workflow included placing an order for an ICS at admission as a patient-supplied medication with an administration comment to “please administer once available from the outpatient pharmacy” (Figure 1). Then, once the discharge medication plan is finalized, the prescription is submitted to the outpatient pharmacy. Following verification of insurance coverage, the outpatient pharmacy dispenses the ICS, allowing it to be used for patient education and inpatient administration. If the patient is ineligible to have their prescription filled by the outpatient pharmacy for reasons other than formulary coverage, the ICS is dispensed from the hospital inpatient pharmacy as per the previous standard workflow. Inpatient ICS inhalers are then relabeled for home use per the existing practice to support medications-in-hand.

Further workflow improvements occurred following the development of an algorithm to help the outpatient pharmacy contact the correct inpatient team, and augmentation of the medication delivery process included notification of the RT when the ICS was delivered to the inpatient unit.

PDSA 4: Prescriber Education

Prescribers received education regarding PDSA interventions before testing and throughout the improvement cycle. Education sessions included informal coaching by the Asthma Education Coordinator, e-mail reminders containing screenshots of the ordering process, and formal didactic sessions for ordering providers. The Asthma Education Coordinator also provided education to the nursing and respiratory therapy staff regarding the implemented process and workflow changes.

PDSA 5: Real-Time Failure Notification

To supplement education for the complicated process change, the improvement team utilized a decision support tool (Vigilanz Corp., Chicago, IL) linked to EMR data to provide notification of real-time process failures. When a patient with an admission diagnosis of asthma had a prescription for an ICS verified and dispensed by the inpatient pharmacy, an automated message with relevant patient information would be sent to a member of the improvement team. Following a brief chart review, directed feedback could be offered to the ordering provider, allowing the prescription to be redirected to the outpatient pharmacy.

Study of the Improvement

Patients of all ages, with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Tenth Revision codes for asthma (493.xx or J45.xx) were included in data collection and analysis if they were treated by the Hospital Medicine service, as the first inpatient service or after transfer from the ICU, and prescribed an ICS with or without a long-acting beta-agonist. Data were collected retrospectively and aggregated monthly. The baseline period was from January 2015 through October 2016. The intervention period was from November 2016 through March 2018. The prolonged baseline and study periods were utilized to understand the seasonal nature of asthma exacerbations.

Measures

Our primary outcome measure was defined as the monthly number of patients admitted to Hospital Medicine for an acute asthma exacerbation administered more than one ICS divided by the total number of asthma patients administered at least one dose of an ICS (patient-supplied or dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy). A full list of ICS is included in the appendix Table.

A secondary process measure approximated our adherence to obtaining ICS from the outpatient pharmacy for inpatient use. All medications administered during hospitalization are documented in the medication administration report. However, only medications dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy are associated with a patient charge. Patient-supplied medications, including those dispensed from the hospital outpatient pharmacy, are not associated with an inpatient charge. Therefore, the secondary process measure was defined as the monthly number of asthma patients administered an ICS not associated with an inpatient charge divided by the total number of asthma patients administered an ICS.

A cost outcome measure was developed to track changes in the average cost of an ICS included on inpatient bills during hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation. This outcome measure was defined as the total monthly cost, using the average wholesale price, of the ICS included on the inpatient bill for an asthma exacerbation, divided by the total number of asthma patients administered at least one dose of an ICS (patient supplied or dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy).

Our a priori intent was to reduce ICS medication waste while maintaining a highly reliable system that included inpatient administration and education with ICS devices and maintain our medications-in-hand practice. A balancing measure was developed to monitor the reliability of inpatient administration of ICS. It was defined as the monthly number of patients who received a discharge prescription for an ICS and were administered an ICS while an inpatient divided by the total number of asthma patients with a discharge prescription for an ICS.

Analysis

Measures were evaluated using statistical process control charts and special cause variation was determined by previously established rules. Our primary, secondary, and balancing measures were all evaluated using a p-chart with variable subgroup size. The cost outcome measure was evaluated using an X-bar S control chart.11-13

RESULTS

Primary Outcome Measure

During the baseline period, 7.4% of patients admitted to Hospital Medicine for an acute asthma exacerbation were administered more than one ICS, ranging from 0%-20% of patients per month (Figure 2). Following the start of our interventions, we met criteria for special cause allowing adjustment of the centerline.13 The mean percentage of patients receiving more than one ICS decreased from 7.4% to 0.7%. Figure 2 includes the n-value displayed each month and represents all patients admitted to the Hospital Medicine service with an asthma exacerbation who were administered at least one ICS.

Secondary Process Measure

During the baseline period, there were only rare occurrences (less than 1%) of a patient-supplied ICS being administered during an asthma admission. Following the start of our intervention period, the frequency of inpatient administration of patient-supplied ICS showed a rapid increase and met rules for special cause with an increase in the mean percent from 0.7% to 50% (Figure 3). The n-value displayed each month represents all patients admitted to the Hospital Medicine service for an asthma exacerbation administered at least one ICS.

Cost Outcome Measure

The average cost of an ICS billed during hospitalization for an acute asthma exacerbation was $236.57 per ICS during the baseline period. After the intervention period, the average inpatient cost for ICS decreased by 62% to $90.25 per ICS (Figure 4).

Balancing Measure

DISCUSSION

Our team reduced the monthly percent of children hospitalized with an acute asthma exacerbation administered more than one ICS from 7.4% to 0.7% after implementation of a new workflow process for ordering ICS utilizing the hospital-based outpatient pharmacy. The new workflow delayed ordering and administration of the initial inpatient ICS treatment, allowing time to consider a step-up in therapy. The brief delay in initiating ICS is not expected to have clinical consequence given the concomitant treatment with systemic corticosteroids. In addition, the outpatient pharmacy was utilized to verify insurance coverage reliably prior to dispensing ICS, reducing medication waste, and discharge delays due to outpatient medication formulary conflicts.

Our hospital’s previous approach to inpatient asthma care resulted in a highly reliable process to ensure patients were discharged with medications-in-hand as part of a broader system that effectively decreased reutilization. However, the previous process inadvertently resulted in medication waste. This waste included nearly full inhalers being discarded, additional work by the healthcare team (ordering providers, pharmacists, and RTs), and unnecessary patient charges.

While the primary driver of our decision to use the outpatient pharmacy was to adjudicate insurance prescription coverage reliably to prevent waste, this change likely resulted in a financial benefit to patients. The average cost per asthma admission of an inpatient billed for ICS using the average wholesale price, decreased by 62% following our interventions. The decrease in cost was primarily driven by using patient-supplied medications, including prescriptions newly filled by the on-site outpatient pharmacy, whose costs were not captured in this measure. While our secondary measure may underestimate the total expense incurred by families for an ICS, families likely receive their medications at a lower cost from the outpatient pharmacy than if the ICS was provided by an inpatient pharmacy. The average wholesale price is not what families are charged or pay for medications, partly due to differences in overhead costs that result in inpatient pharmacies having significantly higher charges than outpatient pharmacies. In addition, the 6.7% absolute reduction of our primary measure resulted in direct savings by reducing inpatient medication waste. Our process results in 67 fewer wasted ICS devices ($15,960) per 1,000 admissions for asthma exacerbation, extrapolated using the average cost ($238.20, average wholesale price) of each ICS during the baseline period.

Our quality improvement study had several limitations. (1) The interventions occurred at a single center with an established culture that embraces quality improvement, which may limit the generalizability of the work. (2) Our process verified insurance coverage with a hospital-based outpatient pharmacy. Some ICS prescriptions continued to be dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy, limiting our ability to verify insurance coverage. Local factors, including regulatory restrictions and delivery requirements, may limit the generalizability of using an outpatient pharmacy in this manner. (3) We achieved our goal of decreasing medication waste, but our a priori goal was to maintain our commitment to our established practice of interactive patient education with an ICS device as well as medications-in-hand at time of discharge. Our balancing measure showed a decrease in the percent of patients with a discharge prescription for an ICS who also received an inpatient dose of that ICS. This implies a decreased fidelity in our previously established education protocols. We had postulated that this occurred when the patient-supplied medication arrived on the day of discharge, but not close to when the medication was scheduled on the medication administration report, preventing administration. However, this is not a direct measure of patients receiving medications-in-hand or interactive medication education. Both may have occurred without administration of the ICS. (4) Despite a hospital culture that embraces quality improvement, this project required a significant change in the workflow that required considerable education at the time of implementation to integrate the new process reliably. However, once the process was in place, we have been able to sustain our improvement with limited educational investment.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementation of a new process for ordering ICS that emphasized delaying treatment until all necessary information was available and using an outpatient pharmacy to confirm insurance formulary coverage reduced the waste associated with more than one ICS being prescribed during a single admission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sally Pope, MPH and Dr. Michael Carlisle, MD for their contribution to the quality improvement project. Thank you to Drs. Karen McDowell, MD and Carolyn Kercsmar, MD for advisement of our quality improvement project.

The authors appreciate the following individuals for their invaluable contributions. Dr. Hoefgen conceptualized and designed the study, was a member of the primary improvement team, carried out initial analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs. Jones and Torres Garcia, and Mr. Hare were members of the primary improvement team who contributed to the design of the quality improvement study and interventions, ongoing data interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. Courter contributed to the conceptualization and designed the study, was a member of the primary improvement team, designed data collection instruments, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Simmons conceptualized and designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclaimer

The information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the BHPR, HRSA, DHHS, or the U.S. Government.

Asthma results in approximately 125,000 hospitalizations for children annually in the United States.1,2 The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines recommend that children with persistent asthma be treated with a daily controller medication, ie, an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS).3 Hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation provides an opportunity to optimize daily controller medications and improve disease self-management by providing access to medications and teaching appropriate use of complicated inhalation devices.

To reduce readmission4 by mitigating low rates of postdischarge filling of ICS prescriptions,5,6 a strategy of “meds-in-hand” was implemented at discharge. “Meds-in-hand” mitigates medication access as a barrier to adherence by ensuring that patients are discharged from the hospital with all required medications in hand, removing any barriers to filling their initial prescriptions.7 The Asthma Improvement Collaborative at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) previously applied quality improvement methodology to implement “meds-in-hand” as a key intervention in a broad strategy that successfully reduced asthma-specific utilization for the 30-day period following an asthma-related hospitalization of publicly insured children from 12% to 7%.8,9

At the onset of the work described in this manuscript, children hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of persistent asthma were most often treated with an ICS while inpatients in addition to a standard short course of oral systemic corticosteroids. Conceptually, inpatient administration of ICS provided the opportunity to teach effective device usage with each inpatient administration and to reinforce daily use of the ICS as part of the patient’s daily home medication regimen. However, a proportion of patients admitted for an asthma exacerbation were noted to receive more than one ICS inhaler during their admission, most commonly due to a change in dose or type of ICS. When this occurred, the initially dispensed inhaler was discarded despite weeks of potential doses remaining. While some hospitals preferentially dispense ICS devices marketed to institutions with fewer doses per device, our pharmacy primarily dispensed ICS devices identical to retail locations containing at least a one-month supply of medication. In addition to the wasted medication, this practice resulted in additional work by healthcare staff, unnecessary patient charges, and potentially contributed to confusion about the discharge medication regimen.

Our specific aim for this quality improvement study was to reduce the monthly percentage of admissions for an acute asthma exacerbation treated with >1 ICS from 7% to 4% over a six-month period.

METHODS

Context

CCHMC is a quaternary care pediatric health system with more than 600 inpatient beds and 800-900 inpatient admissions per year for acute asthma exacerbation. The Hospital Medicine service cares for patients with asthma on five clinical teams across two different campuses. Care teams are supervised by an attending physician and may include residents, fellows, or nurse practitioners. Patients hospitalized for an acute asthma exacerbation may receive a consult from the Asthma Center consult team, staffed by faculty from either the Pediatric Pulmonology or Allergy/Immunology divisions. Respiratory therapists (RTs) administer inhaled medications and provide asthma education.

Planning the Intervention

Our improvement team included physicians from Hospital Medicine and Pulmonary Medicine, an Asthma Education Coordinator, a Clinical Pharmacist, a Pediatric Chief Resident, and a clinical research coordinator. Initial interventions targeted a single resident team at the main campus before spreading improvement activities to all resident teams at the main campus and then the satellite campus by February 2017.

Development of our process map (Figure 1) revealed that the decision for ordering inpatient ICS treatment frequently occurred at admission. Subsequently, the care team or consulting team might make a change in the ICS to fine-tune the outpatient medication regimen given that admission for asthma often results from suboptimal chronic symptom control. Baseline analysis of changes in ICS orders revealed that 81% of ICS changes were associated with a step-up in therapy, defined as an increase in the daily dose of the ICS or the addition of a long-acting beta-agonist. The other common ICS adjustment, accounting for 17%, was a change in corticosteroid without a step-up in therapy, (ie, beclomethasone to fluticasone) that typically occurred near the end of the hospitalization to accommodate outpatient insurance formularies, independent of patient factors related to illness severity.

We utilized the model for improvement and sought to decrease the number of patients administered more than one ICS during an admission through a step-wise quality improvement approach, utilizing plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles.10 This study was reviewed and designated as not human subjects research by the CCHMC institutional review board.

Improvement Activities

We conceived key drivers or domains that would be necessary to address to effect change. Key drivers included a standardized process for delayed initiation of ICS and confirmation of outpatient insurance prescription drug coverage, prescriber education, and real-time failure notification.

PDSA Interventions

PDSA 1 & 2: Standardized Process for Initiation of ICS

Our initial tests of change targeted the timing of when an ICS was ordered during hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation. Providers were instructed to delay ordering an ICS until the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours and to include a standardized communication prompt within the albuterol order. The prompt instructed the RT to contact the provider once the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours and ask for an ICS order, if appropriate. This intervention was abandoned because it did not reliably occur.

The subsequent intervention delayed the start of ICS treatment by using a PRN indication advising that the ICS was to be administered once the patient’s albuterol treatments were spaced to every three hours. However, after an error resulted in the PRN indication being included on a discharge prescription for an ICS, the PRN indication was abandoned. Subsequent work to develop a standardized process for delayed initiation of ICS occurred as part of the workflow to address the confirmation of outpatient formulary coverage as described next.

PDSA 3: Prioritize the Use of the Institution’s Outpatient Pharmacy

Medication changes that occurred because of outpatient insurance formulary denials were a unique challenge; they required a medication change after the discharge treatment plan had been finalized, and a prescription was already submitted to the outpatient pharmacy. In addition, neither our inpatient electronic medical record nor our inpatient hospital pharmacy has access to decision support tools that incorporate outpatient prescription formulary coverage. Alternatively, outpatient pharmacies have a standard workflow that routinely confirms insurance coverage before dispensing medication. The institutional policy was modified to allow for the inpatient administration of patient-supplied medications, pursuant to an inpatient order. Patient-supplied medications include those brought from home or those supplied by the outpatient pharmacy.

Subsequently, we developed a standardized process to confirm outpatient prescription drug coverage by using our hospital-based outpatient pharmacy to dispense ICS for inpatient treatment and asthma education. This new workflow included placing an order for an ICS at admission as a patient-supplied medication with an administration comment to “please administer once available from the outpatient pharmacy” (Figure 1). Then, once the discharge medication plan is finalized, the prescription is submitted to the outpatient pharmacy. Following verification of insurance coverage, the outpatient pharmacy dispenses the ICS, allowing it to be used for patient education and inpatient administration. If the patient is ineligible to have their prescription filled by the outpatient pharmacy for reasons other than formulary coverage, the ICS is dispensed from the hospital inpatient pharmacy as per the previous standard workflow. Inpatient ICS inhalers are then relabeled for home use per the existing practice to support medications-in-hand.

Further workflow improvements occurred following the development of an algorithm to help the outpatient pharmacy contact the correct inpatient team, and augmentation of the medication delivery process included notification of the RT when the ICS was delivered to the inpatient unit.

PDSA 4: Prescriber Education

Prescribers received education regarding PDSA interventions before testing and throughout the improvement cycle. Education sessions included informal coaching by the Asthma Education Coordinator, e-mail reminders containing screenshots of the ordering process, and formal didactic sessions for ordering providers. The Asthma Education Coordinator also provided education to the nursing and respiratory therapy staff regarding the implemented process and workflow changes.

PDSA 5: Real-Time Failure Notification

To supplement education for the complicated process change, the improvement team utilized a decision support tool (Vigilanz Corp., Chicago, IL) linked to EMR data to provide notification of real-time process failures. When a patient with an admission diagnosis of asthma had a prescription for an ICS verified and dispensed by the inpatient pharmacy, an automated message with relevant patient information would be sent to a member of the improvement team. Following a brief chart review, directed feedback could be offered to the ordering provider, allowing the prescription to be redirected to the outpatient pharmacy.

Study of the Improvement

Patients of all ages, with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Tenth Revision codes for asthma (493.xx or J45.xx) were included in data collection and analysis if they were treated by the Hospital Medicine service, as the first inpatient service or after transfer from the ICU, and prescribed an ICS with or without a long-acting beta-agonist. Data were collected retrospectively and aggregated monthly. The baseline period was from January 2015 through October 2016. The intervention period was from November 2016 through March 2018. The prolonged baseline and study periods were utilized to understand the seasonal nature of asthma exacerbations.

Measures

Our primary outcome measure was defined as the monthly number of patients admitted to Hospital Medicine for an acute asthma exacerbation administered more than one ICS divided by the total number of asthma patients administered at least one dose of an ICS (patient-supplied or dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy). A full list of ICS is included in the appendix Table.

A secondary process measure approximated our adherence to obtaining ICS from the outpatient pharmacy for inpatient use. All medications administered during hospitalization are documented in the medication administration report. However, only medications dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy are associated with a patient charge. Patient-supplied medications, including those dispensed from the hospital outpatient pharmacy, are not associated with an inpatient charge. Therefore, the secondary process measure was defined as the monthly number of asthma patients administered an ICS not associated with an inpatient charge divided by the total number of asthma patients administered an ICS.

A cost outcome measure was developed to track changes in the average cost of an ICS included on inpatient bills during hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation. This outcome measure was defined as the total monthly cost, using the average wholesale price, of the ICS included on the inpatient bill for an asthma exacerbation, divided by the total number of asthma patients administered at least one dose of an ICS (patient supplied or dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy).

Our a priori intent was to reduce ICS medication waste while maintaining a highly reliable system that included inpatient administration and education with ICS devices and maintain our medications-in-hand practice. A balancing measure was developed to monitor the reliability of inpatient administration of ICS. It was defined as the monthly number of patients who received a discharge prescription for an ICS and were administered an ICS while an inpatient divided by the total number of asthma patients with a discharge prescription for an ICS.

Analysis

Measures were evaluated using statistical process control charts and special cause variation was determined by previously established rules. Our primary, secondary, and balancing measures were all evaluated using a p-chart with variable subgroup size. The cost outcome measure was evaluated using an X-bar S control chart.11-13

RESULTS

Primary Outcome Measure

During the baseline period, 7.4% of patients admitted to Hospital Medicine for an acute asthma exacerbation were administered more than one ICS, ranging from 0%-20% of patients per month (Figure 2). Following the start of our interventions, we met criteria for special cause allowing adjustment of the centerline.13 The mean percentage of patients receiving more than one ICS decreased from 7.4% to 0.7%. Figure 2 includes the n-value displayed each month and represents all patients admitted to the Hospital Medicine service with an asthma exacerbation who were administered at least one ICS.

Secondary Process Measure

During the baseline period, there were only rare occurrences (less than 1%) of a patient-supplied ICS being administered during an asthma admission. Following the start of our intervention period, the frequency of inpatient administration of patient-supplied ICS showed a rapid increase and met rules for special cause with an increase in the mean percent from 0.7% to 50% (Figure 3). The n-value displayed each month represents all patients admitted to the Hospital Medicine service for an asthma exacerbation administered at least one ICS.

Cost Outcome Measure

The average cost of an ICS billed during hospitalization for an acute asthma exacerbation was $236.57 per ICS during the baseline period. After the intervention period, the average inpatient cost for ICS decreased by 62% to $90.25 per ICS (Figure 4).

Balancing Measure

DISCUSSION

Our team reduced the monthly percent of children hospitalized with an acute asthma exacerbation administered more than one ICS from 7.4% to 0.7% after implementation of a new workflow process for ordering ICS utilizing the hospital-based outpatient pharmacy. The new workflow delayed ordering and administration of the initial inpatient ICS treatment, allowing time to consider a step-up in therapy. The brief delay in initiating ICS is not expected to have clinical consequence given the concomitant treatment with systemic corticosteroids. In addition, the outpatient pharmacy was utilized to verify insurance coverage reliably prior to dispensing ICS, reducing medication waste, and discharge delays due to outpatient medication formulary conflicts.

Our hospital’s previous approach to inpatient asthma care resulted in a highly reliable process to ensure patients were discharged with medications-in-hand as part of a broader system that effectively decreased reutilization. However, the previous process inadvertently resulted in medication waste. This waste included nearly full inhalers being discarded, additional work by the healthcare team (ordering providers, pharmacists, and RTs), and unnecessary patient charges.

While the primary driver of our decision to use the outpatient pharmacy was to adjudicate insurance prescription coverage reliably to prevent waste, this change likely resulted in a financial benefit to patients. The average cost per asthma admission of an inpatient billed for ICS using the average wholesale price, decreased by 62% following our interventions. The decrease in cost was primarily driven by using patient-supplied medications, including prescriptions newly filled by the on-site outpatient pharmacy, whose costs were not captured in this measure. While our secondary measure may underestimate the total expense incurred by families for an ICS, families likely receive their medications at a lower cost from the outpatient pharmacy than if the ICS was provided by an inpatient pharmacy. The average wholesale price is not what families are charged or pay for medications, partly due to differences in overhead costs that result in inpatient pharmacies having significantly higher charges than outpatient pharmacies. In addition, the 6.7% absolute reduction of our primary measure resulted in direct savings by reducing inpatient medication waste. Our process results in 67 fewer wasted ICS devices ($15,960) per 1,000 admissions for asthma exacerbation, extrapolated using the average cost ($238.20, average wholesale price) of each ICS during the baseline period.

Our quality improvement study had several limitations. (1) The interventions occurred at a single center with an established culture that embraces quality improvement, which may limit the generalizability of the work. (2) Our process verified insurance coverage with a hospital-based outpatient pharmacy. Some ICS prescriptions continued to be dispensed from the inpatient pharmacy, limiting our ability to verify insurance coverage. Local factors, including regulatory restrictions and delivery requirements, may limit the generalizability of using an outpatient pharmacy in this manner. (3) We achieved our goal of decreasing medication waste, but our a priori goal was to maintain our commitment to our established practice of interactive patient education with an ICS device as well as medications-in-hand at time of discharge. Our balancing measure showed a decrease in the percent of patients with a discharge prescription for an ICS who also received an inpatient dose of that ICS. This implies a decreased fidelity in our previously established education protocols. We had postulated that this occurred when the patient-supplied medication arrived on the day of discharge, but not close to when the medication was scheduled on the medication administration report, preventing administration. However, this is not a direct measure of patients receiving medications-in-hand or interactive medication education. Both may have occurred without administration of the ICS. (4) Despite a hospital culture that embraces quality improvement, this project required a significant change in the workflow that required considerable education at the time of implementation to integrate the new process reliably. However, once the process was in place, we have been able to sustain our improvement with limited educational investment.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementation of a new process for ordering ICS that emphasized delaying treatment until all necessary information was available and using an outpatient pharmacy to confirm insurance formulary coverage reduced the waste associated with more than one ICS being prescribed during a single admission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sally Pope, MPH and Dr. Michael Carlisle, MD for their contribution to the quality improvement project. Thank you to Drs. Karen McDowell, MD and Carolyn Kercsmar, MD for advisement of our quality improvement project.

The authors appreciate the following individuals for their invaluable contributions. Dr. Hoefgen conceptualized and designed the study, was a member of the primary improvement team, carried out initial analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs. Jones and Torres Garcia, and Mr. Hare were members of the primary improvement team who contributed to the design of the quality improvement study and interventions, ongoing data interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. Courter contributed to the conceptualization and designed the study, was a member of the primary improvement team, designed data collection instruments, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Simmons conceptualized and designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclaimer

The information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the BHPR, HRSA, DHHS, or the U.S. Government.

1. Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing trends in asthma prevalence among children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20152354. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2354.

2. HCUP Databases. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). www.hcup.us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp. Published 2016. Accessed September 14, 2016.

3. NHLBI. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):S94-S138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029.

4. Kenyon CC, Rubin DM, Zorc JJ, Mohamad Z, Faerber JA, Feudtner C. Childhood asthma hospital discharge medication fills and risk of subsequent readmission. J Pediatr. 2015;166(5):1121-1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.019.

5. Bollinger ME, Mudd KE, Boldt A, Hsu VD, Tsoukleris MG, Butz AM. Prescription fill patterns in underserved children with asthma receiving subspecialty care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(3):185-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.009.

6. Cooper WO, Hickson GB. Corticosteroid prescription filling for children covered by Medicaid following an emergency department visit or a hospitalization for asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(10):1111-1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.155.10.1111.

7. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing medication possession at discharge for patients with asthma: the Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461-e20150461. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0461.

8. Kercsmar CM, Beck AF, Sauers-Ford H, et al. Association of an asthma improvement collaborative with health care utilization in medicaid-insured pediatric patients in an urban community. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1072-1080. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2600.

9. Sauers HS, Beck AF, Kahn RS, Simmons JM. Increasing recruitment rates in an inpatient clinical research study using quality improvement methods. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(6):335-341. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0072.

10. Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009.

11. Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(6):458-464. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.6.458.

12. Mohammed MA, Panesar JS, Laney DB, Wilson R. Statistical process control charts for attribute data involving very large sample sizes: a review of problems and solutions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(4):362-368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001373.

13. Moen R, Nolan T, Provost L. Quality Improvement through Planned Experimentation. 2nd ed. New York City: McGraw-Hill Professional; 1998.

1. Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing trends in asthma prevalence among children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20152354. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2354.

2. HCUP Databases. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). www.hcup.us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp. Published 2016. Accessed September 14, 2016.

3. NHLBI. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):S94-S138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029.

4. Kenyon CC, Rubin DM, Zorc JJ, Mohamad Z, Faerber JA, Feudtner C. Childhood asthma hospital discharge medication fills and risk of subsequent readmission. J Pediatr. 2015;166(5):1121-1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.019.

5. Bollinger ME, Mudd KE, Boldt A, Hsu VD, Tsoukleris MG, Butz AM. Prescription fill patterns in underserved children with asthma receiving subspecialty care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(3):185-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.009.

6. Cooper WO, Hickson GB. Corticosteroid prescription filling for children covered by Medicaid following an emergency department visit or a hospitalization for asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(10):1111-1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.155.10.1111.

7. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing medication possession at discharge for patients with asthma: the Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461-e20150461. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0461.

8. Kercsmar CM, Beck AF, Sauers-Ford H, et al. Association of an asthma improvement collaborative with health care utilization in medicaid-insured pediatric patients in an urban community. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1072-1080. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2600.

9. Sauers HS, Beck AF, Kahn RS, Simmons JM. Increasing recruitment rates in an inpatient clinical research study using quality improvement methods. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(6):335-341. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0072.

10. Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009.

11. Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(6):458-464. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.6.458.

12. Mohammed MA, Panesar JS, Laney DB, Wilson R. Statistical process control charts for attribute data involving very large sample sizes: a review of problems and solutions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(4):362-368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001373.

13. Moen R, Nolan T, Provost L. Quality Improvement through Planned Experimentation. 2nd ed. New York City: McGraw-Hill Professional; 1998.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Continued Learning in Supporting Value-Based Decision Making

Physicians, researchers, and policymakers aspire to improve the value of healthcare, with reduced overall costs of care and improved outcomes. An important component of increasing healthcare costs in the United States is the rising cost of prescription medications, accounting for an estimated 17% of all spending in healthcare services.1 One potentially modifiable driver of low-value prescribing is poor awareness of medication cost.2 While displaying price to the ordering physician has reduced laboratory order volume and associated testing costs,3,4 applying cost transparency to medication ordering has produced variable results, perhaps reflecting conceptual differences in decision making regarding diagnosis and treatment.4-6

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Conway et al.7 performed a retrospective analysis applying interrupted times series models to measure the impact of passive cost display on the ordering frequency of 9 high-cost intravenous (IV) or inhaled medications that were identified as likely overused. For 7 of the IV medications, lower-cost oral alternatives were available; 2 study medications had no clear therapeutic alternatives. It was expected that lower-cost oral alternatives would have a concomitant increase in ordering rate as the order rate of the study medications decreased (eg, oral linezolid use would increase as IV linezolid use decreased). Order rate was the primary outcome, reported each week as treatment orders per 10,000 patient days, and was compared for both the pre- and postimplementation time periods. The particular methodology of segmented regressions allowed the research team to control for preintervention trends in medication ordering, as well as to analyze both immediate and delayed effects of the cost-display intervention. The research team framed the cost display as a passive approach. The intervention displayed average wholesale cost data and lower-cost oral alternatives on the ordering screen, which did not significantly reduce the ordering rate. Over the course of the study, outside influences led to 2 more active approaches to higher-cost medications, and Conway et al. wisely measured their effect as well. Specifically, the IV pantoprazole ordering rate decreased after restrictions secondary to a national medication shortage, and the oral voriconazole ordering rate decreased following an oncology order set change from oral voriconazole to oral posaconazole. These ordering-rate decreases were not temporally related to the implementation of the cost display intervention.

It is important to note several limitations of this study, some of which the authors discuss in the manuscript. Because 2 of the medications studied (eculizumab and calcitonin) do not have direct therapeutic alternatives, it is not surprising that price display alone would have no effect. The ordering providers who received this cost information had a more complex decision to make than they would in a scenario with a lower-cost alternative, essentially requiring them to ask “Does this patient need this class of medications at all?” rather than simply, “Is a lower-cost alternative appropriate?” Similarly, choosing medication alternatives that would require different routes of administration (ie, IV and oral) may have limited the effectiveness of a price intervention, given that factors such as illness severity also may influence the decision between IV and oral agents. Thus, the lack of an effect for the price display intervention for these specific medications may not be generalizable to all other medication decisions. Additionally, this manuscript offers limited data on the context in which the intervention was implemented and what adaptations, if any, were made based on early findings. The results may have varied greatly based on the visual design and how the cost display was presented within the electronic medical record. The wider organizational context may also have affected the intervention’s impact. A cost-display intervention appearing in isolation could understandably have a different impact, compared with an intervention within the context of a broader cost/value curriculum directed at house staff and faculty.

In summary, Conway et al. found that just displaying cost data did little to change prescribing patterns, but that more active approaches were quite efficacious. So where does this leave value-minded hospitalists looking to reduce overuse? Relatedly, what are the next steps for research and improvement science? We think there are 3 key strategic areas on which to focus. First, behavioral economics offers a critically important middle ground between the passive approaches studied here and more heavy-handed approaches that may limit provider autonomy, such as restricting drug use at the formulary.8 An improved choice architecture that presents the preferred higher-value option as the default selection may result in improved adoption of the high-value choice while also preserving provider autonomy and expertise required when clinical circumstances make the higher-cost drug the better choice.9,10 The second consideration is to minimize ethical tensions between cost displays that discourage use and a provider’s belief that a treatment is beneficial. Using available ethical frameworks for high-value care that engage both patient and societal concerns may help us choose and design interventions with more successful outcomes.11 Finally, research has shown that providers have poor knowledge of both cost and the relative benefits and harms of treatments and testing.12 Thus, the third opportunity for improvement is to provide appropriate clinical information (ie, relative therapeutic equivalency or adverse effects in alternative therapies) to support decision making at the point of order entry. Encouraging data already exists regarding how drug facts boxes can help patients understand benefits and side effects.13 A similar approach may aid physicians and may prove an easier task than improving patient understanding, given physicians’ substantial existing knowledge. These strategies may help guide providers to make a more informed value determination and obviate some ethical concerns related to clinical decisions based on cost alone. Despite their negative results, Conway et al.7 provided additional evidence that influencing complex decision making is not easy. However, we believe that continuing research into the factors that lead to successful value interventions has incredible potential for supporting high-value decision making in the future.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858-871. PubMed

2. Allan GM, Lexchin J, Wiebe N. Physician awareness of drug cost: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e283. PubMed

3. Feldman LS, Shihab HM, Thiemann D, et al. Impact of providing fee data on laboratory test ordering: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):903-908. PubMed

4. Silvestri MT, Bongiovanni TR, Glover JG, Gross CP. Impact of price display on provider ordering: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):65-76. PubMed

5. Guterman JJ, Chernof BA, Mares B, Gross-Schulman SG, Gan PG, Thomas D. Modifying provider behavior: a low-tech approach to pharmaceutical ordering. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(10):792-796. PubMed

6. Goetz C, Rotman SR, Hartoularos G, Bishop TF. The effect of charge display on cost of care and physician practice behaviors: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):835-842. PubMed