User login

Anti-Smith and Anti–Double-Stranded DNA Antibodies in a Patient With Henoch-Schönlein Purpura Following COVID-19 Vaccination

To the Editor:

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)(also known as IgA vasculitis) is a small vessel vasculitis characterized by deposition of IgA in small vessels, resulting in the development of purpura on the legs. Based on the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria,1 the patient also must have at least 1 of the following: arthritis, arthralgia, abdominal pain, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposition, or kidney involvement. The disease can be triggered by infection—with more than 75% of patients reporting an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection2—as well as medications, circulating immune complexes, certain foods, vaccines, and rarely cancer.3,4 The disease more commonly occurs in children but also can affect adults.

Several cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.5 We report a case of HSP developing days after the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster that was associated with anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies as well as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs).

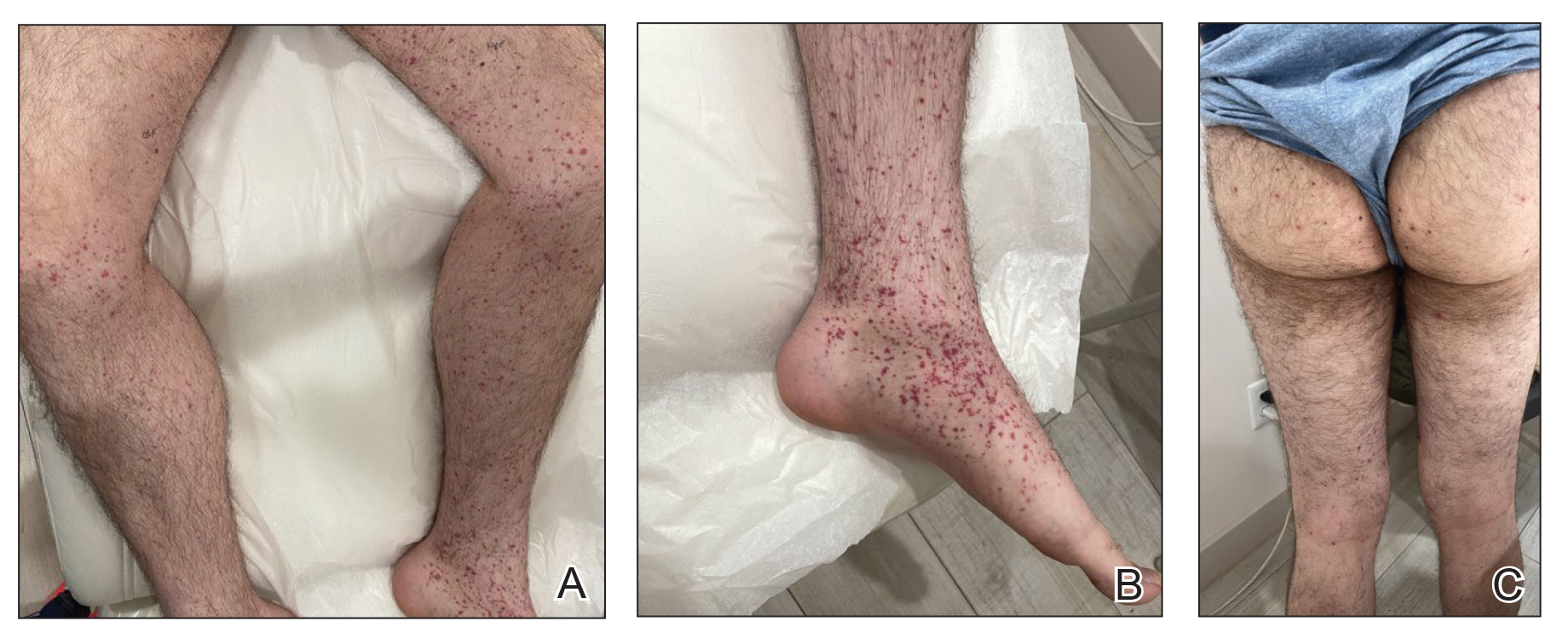

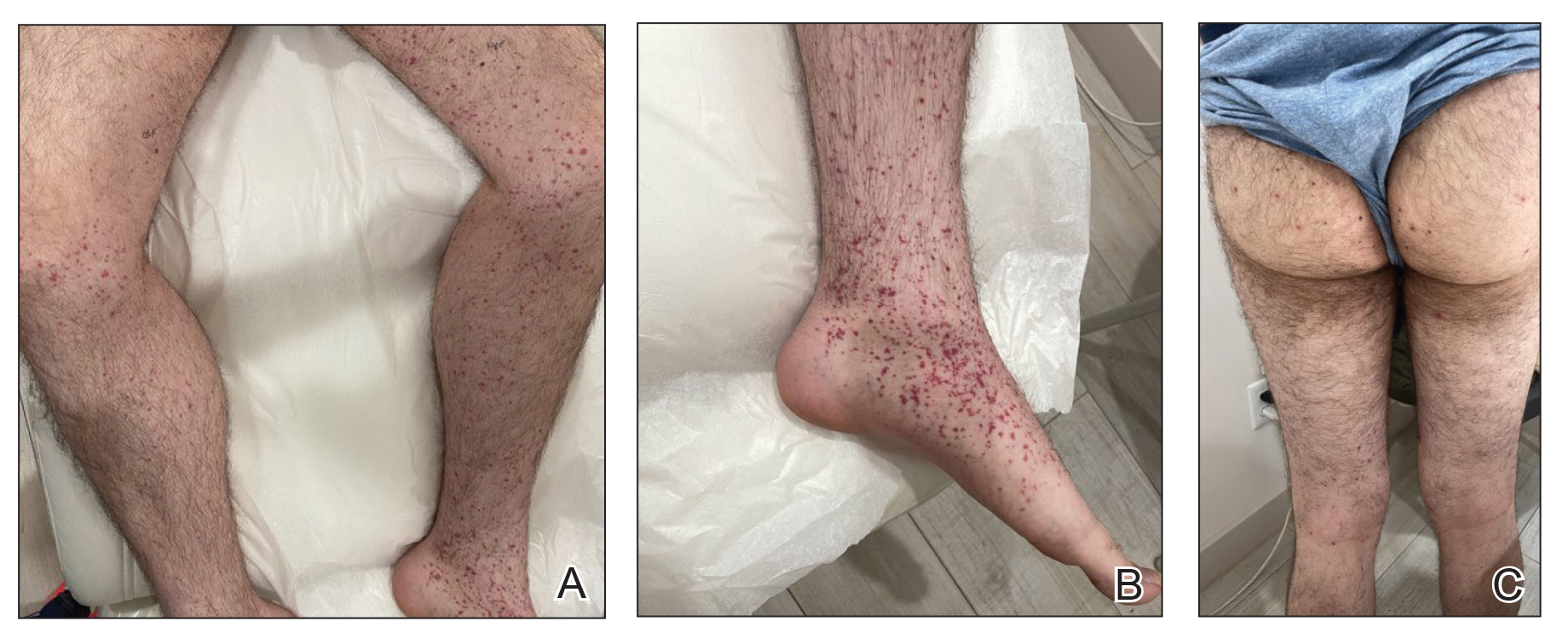

A 24-year-old man presented to dermatology with a rash of 3 weeks’ duration that first appeared 1 week after receiving his second booster of the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Physical examination revealed petechiae with nonblanching erythematous macules and papules covering the legs below the knees (Figure 1) as well as the back of the right arm. A few days later, he developed arthralgia in the knees, hands, and feet. The patient denied any recent infections as well as respiratory and urinary tract symptoms. Approximately 10 days after the rash appeared, he developed epigastric abdominal pain that gradually worsened and sought care from his primary care physician, who ordered computed tomography and referred him for endoscopy. Computed tomography with and without contrast was suspicious for colitis. Colonoscopy and endoscopy were unremarkable. Laboratory tests were notable for elevated white blood cell count (17.08×103/µL [reference range, 3.66–10.60×103/µL]), serum IgA (437 mg/dL [reference range, 70–400 mg/dL]), C-reactive protein (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, <0.5 mg/dL]), anti-Smith antibody (28.1 CU [reference range, <20 CU), positive antinuclear antibody with titer (1:160 [reference range, <1:80]), anti-dsDNA (40.4 IU/mL [reference range, <27 IU/mL]), and cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) titer (1:320 [reference range, <1:20]). Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were all within reference range. Urinalysis with microscopic examination was notable for 2 to 5 red blood cells per high-power field (reference range, 0) and proteinuria of 1+ (reference range, negative for protein).

The patient’s rash progressively worsened over the next few weeks, spreading proximally on the legs to the buttocks and the back of both elbows. A repeat complete blood cell count showed resolution of the leukocytosis. Two biopsies were taken from a lesion on the left proximal thigh: 1 for hematoxylin and eosin stain for histopathologic examination and 1 for direct immunofluorescence examination.

The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with HSP, and dermatology prescribed oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily for 5 days, which was supposed to be increased to 10 mg twice daily on the sixth day of treatment; however, the patient discontinued the medication after 4 days based on his primary care physician’s recommendation due to clotting concerns. The rash and arthralgia temporarily improved for 1 week, then relapsed.

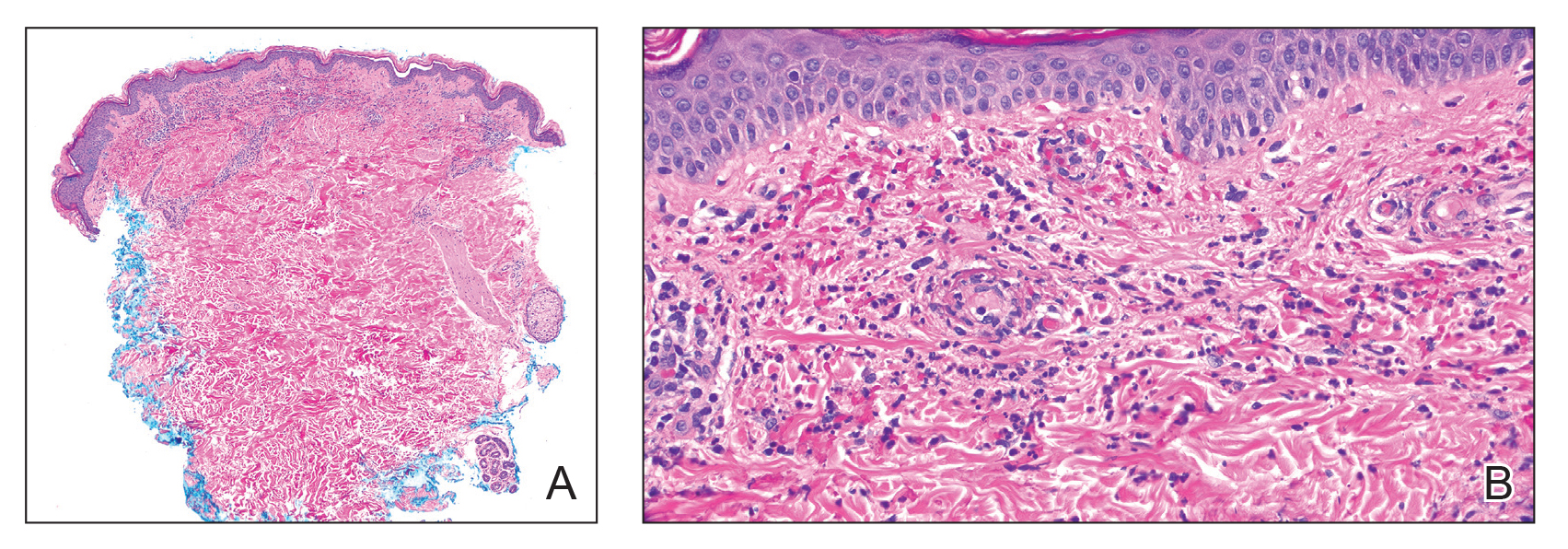

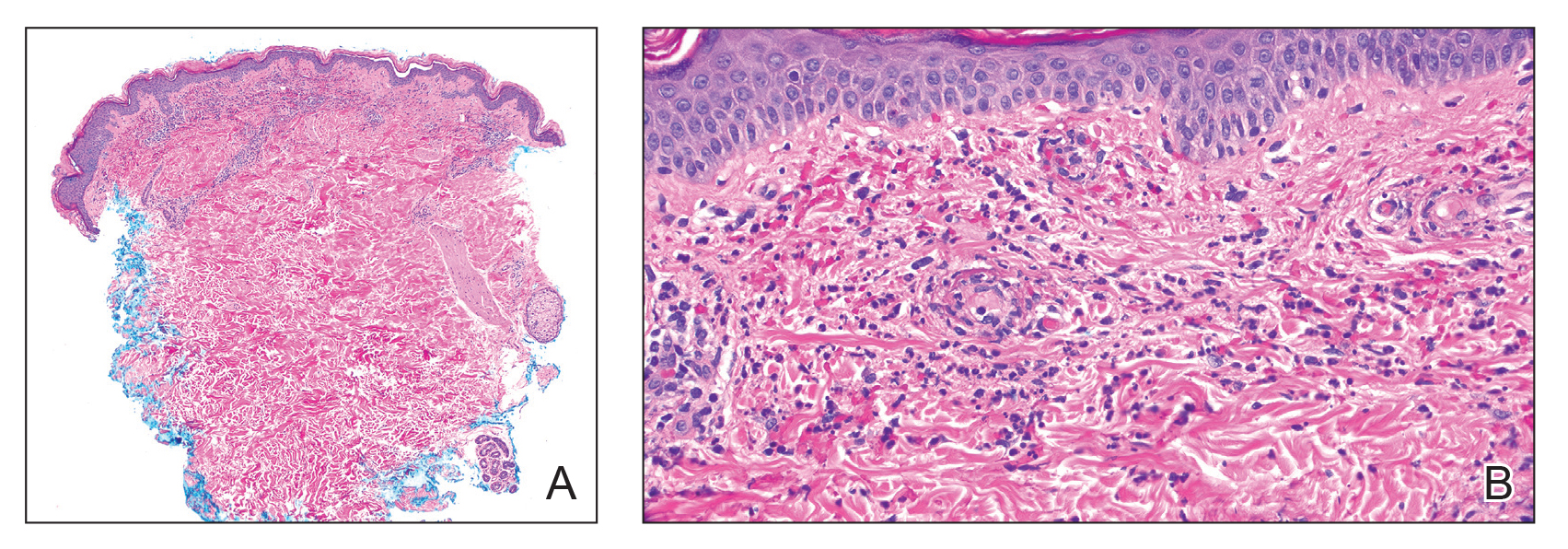

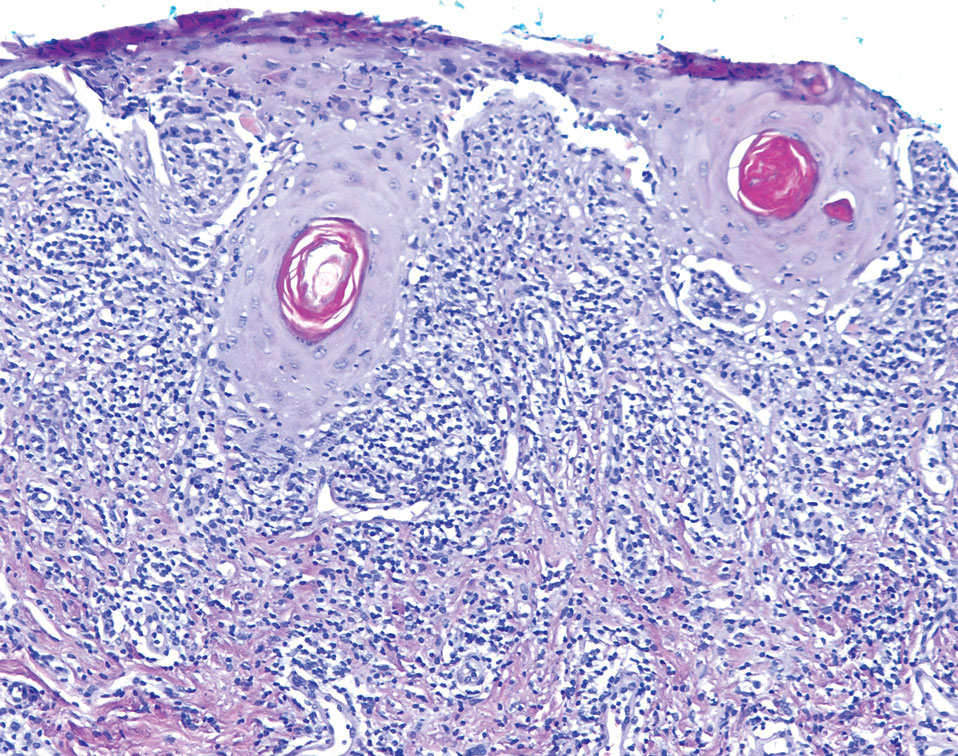

Histopathology revealed neutrophils surrounding and infiltrating small dermal blood vessel walls as well as associated neutrophilic debris and erythrocytes, consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgA antibodies. His primary care physician, in consultation with his dermatologist, then started the patient on oral prednisone 70 mg once daily for 7 days with a plan to taper. Three days after prednisone was started, the arthralgia and abdominal pain resolved, and the rash became lighter in color. After 1 week, the rash resolved completely.

Due to the unusual antibodies, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist, who repeated the blood tests approximately 1 week after the patient started prednisone. The tests were negative for anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and c-ANCA but showed an elevated atypical perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) titer of 1:80 (reference range [negative], <1:20). A repeat urinalysis was unremarkable. The patient slowly tapered the prednisone over the course of 3 months and was subsequently lost to follow-up. The rash and other symptoms had not recurred as of the patient’s last physician contact. The most recent laboratory results showed a white blood cell count of 14.0×103/µL (reference range, 3.4–10.8×103/µL), likely due to the prednisone; blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were within reference range. The urinalysis was notable for occult blood and was negative for protein. C-reactive protein was 1 mg/dL (reference range, 0–10 mg/dL); p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and atypical p-ANCA, as well as antinuclear antibody, were negative. As of his last follow-up, the patient felt well.

The major differential diagnoses for our patient included HSP, ANCA vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Although ANCA vasculitis has been reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection,6 the lack of pulmonary symptoms made this diagnosis unlikely.7 Although our patient initially had elevated anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as mild renal involvement, he fulfilled at most only 2 of the 11 criteria necessary for diagnosing lupus: malar rash, discoid rash (includes alopecia), photosensitivity, ocular ulcers, nonerosive arthritis, serositis, renal disorder (protein >500 mg/24 h, red blood cells, casts), neurologic disorder (seizures, psychosis), hematologic disorders (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia), ANA, and immunologic disorder (anti-Smith). Four of the 11 criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of lupus.8

Torraca et al7 reported a case of HSP with positive c-ANCA (1:640) in a patient lacking pulmonary symptoms who was diagnosed with HSP. Cytoplasmic ANCA is not a typical finding in HSP. However, the additional findings of anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and mildly elevated atypical p-ANCA antibodies in our patient were unexpected and could be explained by the proposed pathogenesis of HSP—an overzealous immune response resulting in aberrant antibody complex deposition with ensuing complement activation.5,9 Production of these additional antibodies could be part of the overzealous response to COVID-19 vaccination.

Of all the COVID-19 vaccines, messenger RNA–based vaccines have been associated with the majority of cutaneous reactions, including local injection-site reactions (most common), delayed local reactions, urticaria, angioedema, morbilliform eruption, herpes zoster eruption, bullous eruptions, dermal filler reactions, chilblains, and pityriasis rosea. Less common reactions have included acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet Syndrome, lichen planus, papulovesicular eruptions, pityriasis rosea–like eruptions, generalized annular lesions, facial pustular neutrophilic eruptions, and flares of underlying autoimmune skin conditions.10 Multiple cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination from all the major vaccine companies.5

In our patient, laboratory tests were repeated by a rheumatologist and were negative for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as c-ANCA, most likely because he started taking prednisone approximately 1 week prior, which may have resulted in decreased antibodies. Also, the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 week of steroid therapy. Therefore, the diagnosis is most consistent with HSP associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The clinical presentation, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria, and histopathology were consistent with the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for HSP.1

Although direct immunofluorescence typically is positive for IgA deposition on biopsies, it can be negative for IgA, especially in lesions that are biopsied more than 7 days after their appearance, as shown in our case; a negative IgA on immunofluorescence does not rule out HSP.4 Elevated serum IgA is seen in more than 50% of cases of HSP.11 Although the disease typically is self-limited, glucocorticoids are used if the disease course is prolonged or if there is evidence of kidney involvement.9 The unique combination of anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs associated with HSP with negative IgA on direct immunofluorescence has been reported with lupus.12 Clinicians should be aware of COVID-19 vaccine–associated HSP that is negative for IgA deposition and positive for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs.

Acknowledgment—We thank our patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.046300

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Casini F, Magenes VC, De Sanctis M, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following COVID-19 vaccine in a child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:158. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01351-1

- Poudel P, Adams SH, Mirchia K, et al. IgA negative immunofluorescence in diagnoses of adult-onset Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33:436-437. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1770526

- Maronese CA, Zelin E, Avallone G, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis and vasculopathy in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:996288. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.996288

- Bryant MC, Spencer LT, Yalcindag A. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a 16-year-old female following SARS-COV-2 infection and a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20:65. doi:10.1186/s12969-022-00727-1

- Torraca PFS, Castro BC, Hans Filho G. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with c-ANCA antibody in adult. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:667-669. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164181

- Agabegi SS, Agabegi ED. Step-Up to Medicine. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Ball-Burack MR, Kosowsky JM. A Case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:E62-E65. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.10.005

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Pang SM. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: a review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:178-186. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.011

- Calviño MC, Llorca J, García-Porrúa C, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from northwestern Spain: a 20-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:279-290.

- Hu P, Huang BY, Zhang DD, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a pediatric patient with lupus. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:689-690. doi:10.5114/aoms.2017.67288

To the Editor:

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)(also known as IgA vasculitis) is a small vessel vasculitis characterized by deposition of IgA in small vessels, resulting in the development of purpura on the legs. Based on the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria,1 the patient also must have at least 1 of the following: arthritis, arthralgia, abdominal pain, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposition, or kidney involvement. The disease can be triggered by infection—with more than 75% of patients reporting an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection2—as well as medications, circulating immune complexes, certain foods, vaccines, and rarely cancer.3,4 The disease more commonly occurs in children but also can affect adults.

Several cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.5 We report a case of HSP developing days after the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster that was associated with anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies as well as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs).

A 24-year-old man presented to dermatology with a rash of 3 weeks’ duration that first appeared 1 week after receiving his second booster of the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Physical examination revealed petechiae with nonblanching erythematous macules and papules covering the legs below the knees (Figure 1) as well as the back of the right arm. A few days later, he developed arthralgia in the knees, hands, and feet. The patient denied any recent infections as well as respiratory and urinary tract symptoms. Approximately 10 days after the rash appeared, he developed epigastric abdominal pain that gradually worsened and sought care from his primary care physician, who ordered computed tomography and referred him for endoscopy. Computed tomography with and without contrast was suspicious for colitis. Colonoscopy and endoscopy were unremarkable. Laboratory tests were notable for elevated white blood cell count (17.08×103/µL [reference range, 3.66–10.60×103/µL]), serum IgA (437 mg/dL [reference range, 70–400 mg/dL]), C-reactive protein (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, <0.5 mg/dL]), anti-Smith antibody (28.1 CU [reference range, <20 CU), positive antinuclear antibody with titer (1:160 [reference range, <1:80]), anti-dsDNA (40.4 IU/mL [reference range, <27 IU/mL]), and cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) titer (1:320 [reference range, <1:20]). Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were all within reference range. Urinalysis with microscopic examination was notable for 2 to 5 red blood cells per high-power field (reference range, 0) and proteinuria of 1+ (reference range, negative for protein).

The patient’s rash progressively worsened over the next few weeks, spreading proximally on the legs to the buttocks and the back of both elbows. A repeat complete blood cell count showed resolution of the leukocytosis. Two biopsies were taken from a lesion on the left proximal thigh: 1 for hematoxylin and eosin stain for histopathologic examination and 1 for direct immunofluorescence examination.

The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with HSP, and dermatology prescribed oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily for 5 days, which was supposed to be increased to 10 mg twice daily on the sixth day of treatment; however, the patient discontinued the medication after 4 days based on his primary care physician’s recommendation due to clotting concerns. The rash and arthralgia temporarily improved for 1 week, then relapsed.

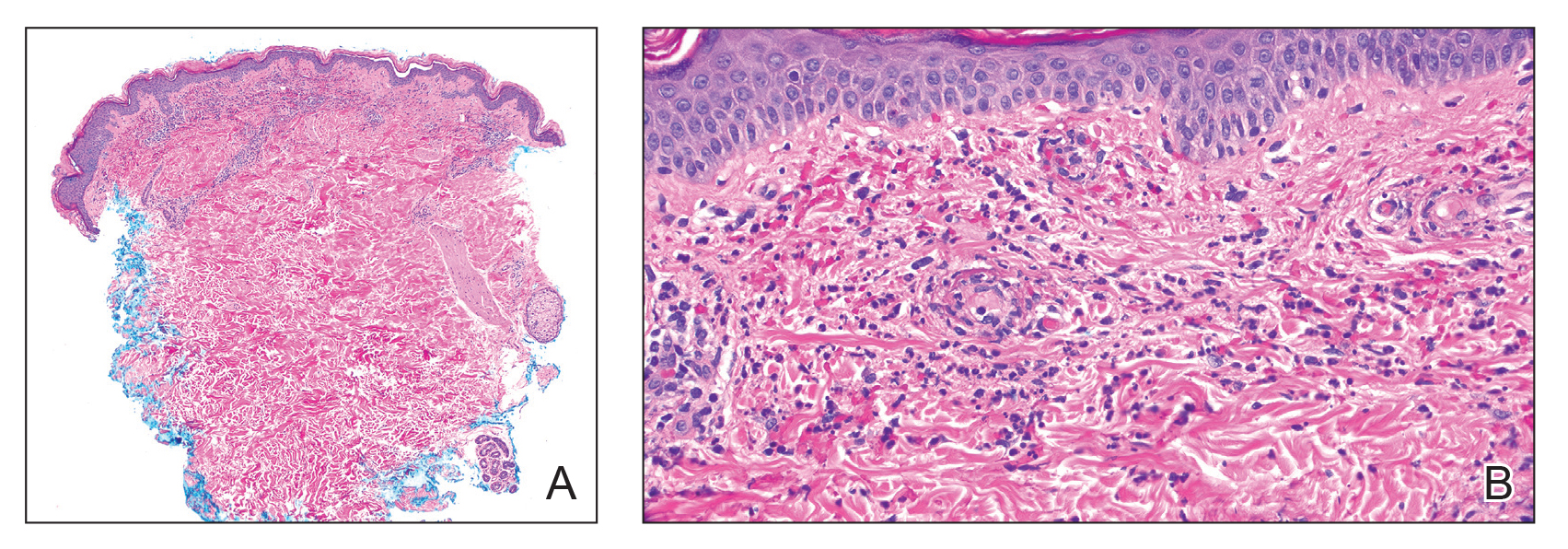

Histopathology revealed neutrophils surrounding and infiltrating small dermal blood vessel walls as well as associated neutrophilic debris and erythrocytes, consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgA antibodies. His primary care physician, in consultation with his dermatologist, then started the patient on oral prednisone 70 mg once daily for 7 days with a plan to taper. Three days after prednisone was started, the arthralgia and abdominal pain resolved, and the rash became lighter in color. After 1 week, the rash resolved completely.

Due to the unusual antibodies, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist, who repeated the blood tests approximately 1 week after the patient started prednisone. The tests were negative for anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and c-ANCA but showed an elevated atypical perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) titer of 1:80 (reference range [negative], <1:20). A repeat urinalysis was unremarkable. The patient slowly tapered the prednisone over the course of 3 months and was subsequently lost to follow-up. The rash and other symptoms had not recurred as of the patient’s last physician contact. The most recent laboratory results showed a white blood cell count of 14.0×103/µL (reference range, 3.4–10.8×103/µL), likely due to the prednisone; blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were within reference range. The urinalysis was notable for occult blood and was negative for protein. C-reactive protein was 1 mg/dL (reference range, 0–10 mg/dL); p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and atypical p-ANCA, as well as antinuclear antibody, were negative. As of his last follow-up, the patient felt well.

The major differential diagnoses for our patient included HSP, ANCA vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Although ANCA vasculitis has been reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection,6 the lack of pulmonary symptoms made this diagnosis unlikely.7 Although our patient initially had elevated anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as mild renal involvement, he fulfilled at most only 2 of the 11 criteria necessary for diagnosing lupus: malar rash, discoid rash (includes alopecia), photosensitivity, ocular ulcers, nonerosive arthritis, serositis, renal disorder (protein >500 mg/24 h, red blood cells, casts), neurologic disorder (seizures, psychosis), hematologic disorders (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia), ANA, and immunologic disorder (anti-Smith). Four of the 11 criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of lupus.8

Torraca et al7 reported a case of HSP with positive c-ANCA (1:640) in a patient lacking pulmonary symptoms who was diagnosed with HSP. Cytoplasmic ANCA is not a typical finding in HSP. However, the additional findings of anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and mildly elevated atypical p-ANCA antibodies in our patient were unexpected and could be explained by the proposed pathogenesis of HSP—an overzealous immune response resulting in aberrant antibody complex deposition with ensuing complement activation.5,9 Production of these additional antibodies could be part of the overzealous response to COVID-19 vaccination.

Of all the COVID-19 vaccines, messenger RNA–based vaccines have been associated with the majority of cutaneous reactions, including local injection-site reactions (most common), delayed local reactions, urticaria, angioedema, morbilliform eruption, herpes zoster eruption, bullous eruptions, dermal filler reactions, chilblains, and pityriasis rosea. Less common reactions have included acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet Syndrome, lichen planus, papulovesicular eruptions, pityriasis rosea–like eruptions, generalized annular lesions, facial pustular neutrophilic eruptions, and flares of underlying autoimmune skin conditions.10 Multiple cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination from all the major vaccine companies.5

In our patient, laboratory tests were repeated by a rheumatologist and were negative for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as c-ANCA, most likely because he started taking prednisone approximately 1 week prior, which may have resulted in decreased antibodies. Also, the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 week of steroid therapy. Therefore, the diagnosis is most consistent with HSP associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The clinical presentation, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria, and histopathology were consistent with the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for HSP.1

Although direct immunofluorescence typically is positive for IgA deposition on biopsies, it can be negative for IgA, especially in lesions that are biopsied more than 7 days after their appearance, as shown in our case; a negative IgA on immunofluorescence does not rule out HSP.4 Elevated serum IgA is seen in more than 50% of cases of HSP.11 Although the disease typically is self-limited, glucocorticoids are used if the disease course is prolonged or if there is evidence of kidney involvement.9 The unique combination of anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs associated with HSP with negative IgA on direct immunofluorescence has been reported with lupus.12 Clinicians should be aware of COVID-19 vaccine–associated HSP that is negative for IgA deposition and positive for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs.

Acknowledgment—We thank our patient for granting permission to publish this information.

To the Editor:

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)(also known as IgA vasculitis) is a small vessel vasculitis characterized by deposition of IgA in small vessels, resulting in the development of purpura on the legs. Based on the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria,1 the patient also must have at least 1 of the following: arthritis, arthralgia, abdominal pain, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposition, or kidney involvement. The disease can be triggered by infection—with more than 75% of patients reporting an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection2—as well as medications, circulating immune complexes, certain foods, vaccines, and rarely cancer.3,4 The disease more commonly occurs in children but also can affect adults.

Several cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.5 We report a case of HSP developing days after the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster that was associated with anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies as well as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs).

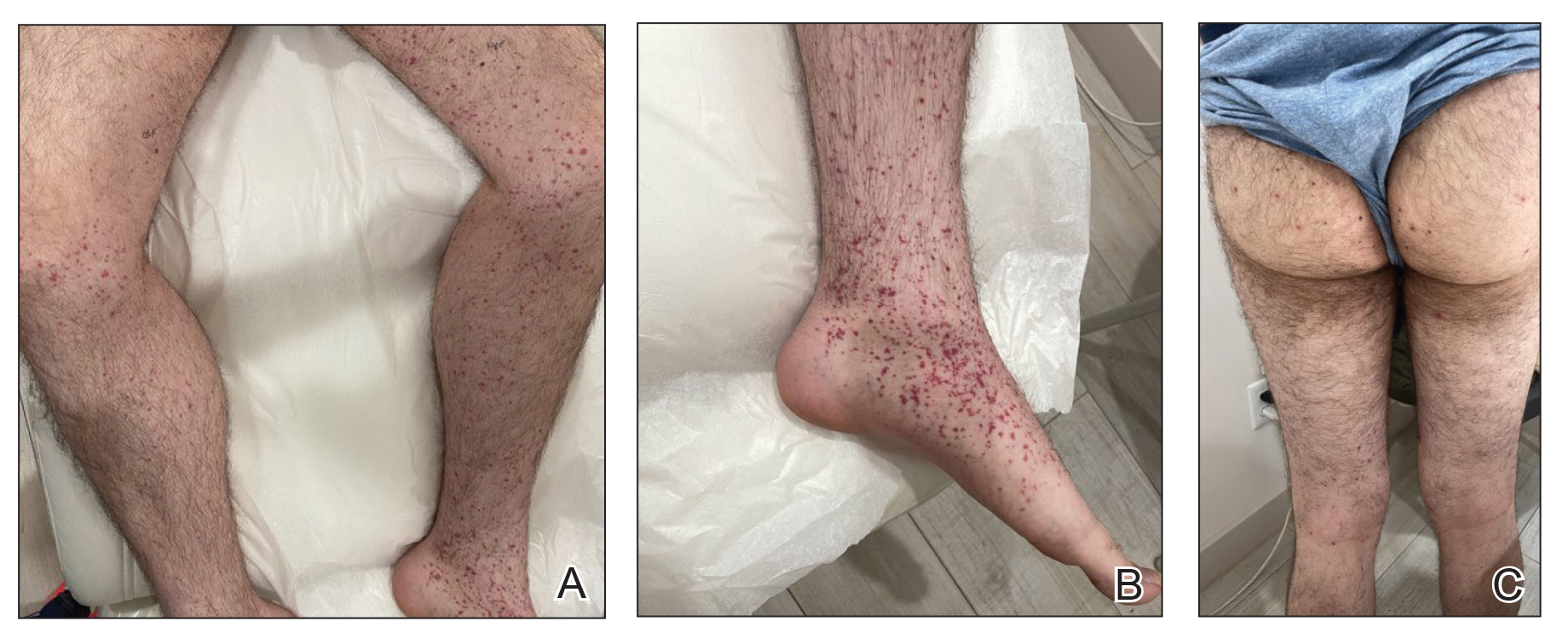

A 24-year-old man presented to dermatology with a rash of 3 weeks’ duration that first appeared 1 week after receiving his second booster of the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Physical examination revealed petechiae with nonblanching erythematous macules and papules covering the legs below the knees (Figure 1) as well as the back of the right arm. A few days later, he developed arthralgia in the knees, hands, and feet. The patient denied any recent infections as well as respiratory and urinary tract symptoms. Approximately 10 days after the rash appeared, he developed epigastric abdominal pain that gradually worsened and sought care from his primary care physician, who ordered computed tomography and referred him for endoscopy. Computed tomography with and without contrast was suspicious for colitis. Colonoscopy and endoscopy were unremarkable. Laboratory tests were notable for elevated white blood cell count (17.08×103/µL [reference range, 3.66–10.60×103/µL]), serum IgA (437 mg/dL [reference range, 70–400 mg/dL]), C-reactive protein (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, <0.5 mg/dL]), anti-Smith antibody (28.1 CU [reference range, <20 CU), positive antinuclear antibody with titer (1:160 [reference range, <1:80]), anti-dsDNA (40.4 IU/mL [reference range, <27 IU/mL]), and cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) titer (1:320 [reference range, <1:20]). Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were all within reference range. Urinalysis with microscopic examination was notable for 2 to 5 red blood cells per high-power field (reference range, 0) and proteinuria of 1+ (reference range, negative for protein).

The patient’s rash progressively worsened over the next few weeks, spreading proximally on the legs to the buttocks and the back of both elbows. A repeat complete blood cell count showed resolution of the leukocytosis. Two biopsies were taken from a lesion on the left proximal thigh: 1 for hematoxylin and eosin stain for histopathologic examination and 1 for direct immunofluorescence examination.

The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with HSP, and dermatology prescribed oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily for 5 days, which was supposed to be increased to 10 mg twice daily on the sixth day of treatment; however, the patient discontinued the medication after 4 days based on his primary care physician’s recommendation due to clotting concerns. The rash and arthralgia temporarily improved for 1 week, then relapsed.

Histopathology revealed neutrophils surrounding and infiltrating small dermal blood vessel walls as well as associated neutrophilic debris and erythrocytes, consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgA antibodies. His primary care physician, in consultation with his dermatologist, then started the patient on oral prednisone 70 mg once daily for 7 days with a plan to taper. Three days after prednisone was started, the arthralgia and abdominal pain resolved, and the rash became lighter in color. After 1 week, the rash resolved completely.

Due to the unusual antibodies, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist, who repeated the blood tests approximately 1 week after the patient started prednisone. The tests were negative for anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and c-ANCA but showed an elevated atypical perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) titer of 1:80 (reference range [negative], <1:20). A repeat urinalysis was unremarkable. The patient slowly tapered the prednisone over the course of 3 months and was subsequently lost to follow-up. The rash and other symptoms had not recurred as of the patient’s last physician contact. The most recent laboratory results showed a white blood cell count of 14.0×103/µL (reference range, 3.4–10.8×103/µL), likely due to the prednisone; blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were within reference range. The urinalysis was notable for occult blood and was negative for protein. C-reactive protein was 1 mg/dL (reference range, 0–10 mg/dL); p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and atypical p-ANCA, as well as antinuclear antibody, were negative. As of his last follow-up, the patient felt well.

The major differential diagnoses for our patient included HSP, ANCA vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Although ANCA vasculitis has been reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection,6 the lack of pulmonary symptoms made this diagnosis unlikely.7 Although our patient initially had elevated anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as mild renal involvement, he fulfilled at most only 2 of the 11 criteria necessary for diagnosing lupus: malar rash, discoid rash (includes alopecia), photosensitivity, ocular ulcers, nonerosive arthritis, serositis, renal disorder (protein >500 mg/24 h, red blood cells, casts), neurologic disorder (seizures, psychosis), hematologic disorders (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia), ANA, and immunologic disorder (anti-Smith). Four of the 11 criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of lupus.8

Torraca et al7 reported a case of HSP with positive c-ANCA (1:640) in a patient lacking pulmonary symptoms who was diagnosed with HSP. Cytoplasmic ANCA is not a typical finding in HSP. However, the additional findings of anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and mildly elevated atypical p-ANCA antibodies in our patient were unexpected and could be explained by the proposed pathogenesis of HSP—an overzealous immune response resulting in aberrant antibody complex deposition with ensuing complement activation.5,9 Production of these additional antibodies could be part of the overzealous response to COVID-19 vaccination.

Of all the COVID-19 vaccines, messenger RNA–based vaccines have been associated with the majority of cutaneous reactions, including local injection-site reactions (most common), delayed local reactions, urticaria, angioedema, morbilliform eruption, herpes zoster eruption, bullous eruptions, dermal filler reactions, chilblains, and pityriasis rosea. Less common reactions have included acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet Syndrome, lichen planus, papulovesicular eruptions, pityriasis rosea–like eruptions, generalized annular lesions, facial pustular neutrophilic eruptions, and flares of underlying autoimmune skin conditions.10 Multiple cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination from all the major vaccine companies.5

In our patient, laboratory tests were repeated by a rheumatologist and were negative for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as c-ANCA, most likely because he started taking prednisone approximately 1 week prior, which may have resulted in decreased antibodies. Also, the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 week of steroid therapy. Therefore, the diagnosis is most consistent with HSP associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The clinical presentation, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria, and histopathology were consistent with the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for HSP.1

Although direct immunofluorescence typically is positive for IgA deposition on biopsies, it can be negative for IgA, especially in lesions that are biopsied more than 7 days after their appearance, as shown in our case; a negative IgA on immunofluorescence does not rule out HSP.4 Elevated serum IgA is seen in more than 50% of cases of HSP.11 Although the disease typically is self-limited, glucocorticoids are used if the disease course is prolonged or if there is evidence of kidney involvement.9 The unique combination of anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs associated with HSP with negative IgA on direct immunofluorescence has been reported with lupus.12 Clinicians should be aware of COVID-19 vaccine–associated HSP that is negative for IgA deposition and positive for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs.

Acknowledgment—We thank our patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.046300

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Casini F, Magenes VC, De Sanctis M, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following COVID-19 vaccine in a child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:158. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01351-1

- Poudel P, Adams SH, Mirchia K, et al. IgA negative immunofluorescence in diagnoses of adult-onset Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33:436-437. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1770526

- Maronese CA, Zelin E, Avallone G, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis and vasculopathy in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:996288. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.996288

- Bryant MC, Spencer LT, Yalcindag A. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a 16-year-old female following SARS-COV-2 infection and a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20:65. doi:10.1186/s12969-022-00727-1

- Torraca PFS, Castro BC, Hans Filho G. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with c-ANCA antibody in adult. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:667-669. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164181

- Agabegi SS, Agabegi ED. Step-Up to Medicine. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Ball-Burack MR, Kosowsky JM. A Case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:E62-E65. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.10.005

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Pang SM. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: a review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:178-186. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.011

- Calviño MC, Llorca J, García-Porrúa C, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from northwestern Spain: a 20-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:279-290.

- Hu P, Huang BY, Zhang DD, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a pediatric patient with lupus. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:689-690. doi:10.5114/aoms.2017.67288

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.046300

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Casini F, Magenes VC, De Sanctis M, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following COVID-19 vaccine in a child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:158. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01351-1

- Poudel P, Adams SH, Mirchia K, et al. IgA negative immunofluorescence in diagnoses of adult-onset Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33:436-437. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1770526

- Maronese CA, Zelin E, Avallone G, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis and vasculopathy in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:996288. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.996288

- Bryant MC, Spencer LT, Yalcindag A. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a 16-year-old female following SARS-COV-2 infection and a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20:65. doi:10.1186/s12969-022-00727-1

- Torraca PFS, Castro BC, Hans Filho G. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with c-ANCA antibody in adult. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:667-669. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164181

- Agabegi SS, Agabegi ED. Step-Up to Medicine. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Ball-Burack MR, Kosowsky JM. A Case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:E62-E65. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.10.005

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Pang SM. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: a review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:178-186. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.011

- Calviño MC, Llorca J, García-Porrúa C, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from northwestern Spain: a 20-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:279-290.

- Hu P, Huang BY, Zhang DD, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a pediatric patient with lupus. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:689-690. doi:10.5114/aoms.2017.67288

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be vigilant for Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) despite negative direct immunofluorescence of IgA deposition and unusual antibodies.

- Messenger RNA–based COVID-19 vaccines are associated with various cutaneous reactions, including HSP.

- Anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies typically are not associated with HSP but may be seen in patients with coexisting systemic lupus erythematosus.

Severe Esophageal Lichen Planus Treated With Tofacitinib

To reach early diagnoses and improve outcomes in cases of mucosal and esophageal lichen planus (ELP), patient education along with a multidisciplinary approach centered on collaboration among dermatologists, gastroenterologists, gynecologists, and dental practitioners should be a priority. Tofacitinib therapy should be considered in the treatment of patients presenting with cutaneous lichen planus (CLP), mucosal lichen planus, and ELP.

Lichen planus is a papulosquamous disease of the skin and mucous membranes that is most common on the skin and oral mucosa. Typical lesions of CLP present as purple, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques on the flexural surfaces of the wrists and ankles as well as areas of friction or trauma due to scratching such as the shins and lower back. Various subtypes of lichen planus can present simultaneously, resulting in extensive involvement that worsens through koebnerization and affects the oral cavity, esophagus, larynx, sclera, genitalia, scalp, and nails.1,2

Esophageal lichen planus can develop with or without the presence of CLP, oral lichen planus (OLP), or genital lichen planus.3 It typically affects women older than 50 years and is linked to OLP and vulvar lichen planus, with 1 study reporting that 87% (63/72) of ELP patients were women with a median age of 61.9 years at the time of diagnosis (range, 22–85 years). Almost all ELP patients in the study had lichen planus symptoms in other locations; 89% (64/72) had OLP, and 42% (30/72) had vulvar lichen planus.4 Consequently, a diagnosis of ELP should be followed by a thorough full-body examination to check for lichen planus at other sites. Studies that examined lichen planus patients for ELP found that 25% to 50% of patients diagnosed with orocutaneous lichen planus also had ELP, with ELP frequently presenting without symptoms.3,5 These findings indicate that ELP likely is underdiagnosed and often misdiagnosed, resulting in an underestimation of its prevalence.

Our case highlights a frequently misdiagnosed condition and underscores the importance of close examination of patients presenting with CLP and OLP for signs and symptoms of ELP. Furthermore, we discuss the importance of patient education and collaboration among different specialties in attaining an early diagnosis to improve patient outcomes. Finally, we review the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of CLP, OLP, and ELP, as well as the utility of tofacitinib for ELP.

Case Report

An emaciated 89-year-old woman with an 11-year history of CLP, OLP, and genital lichen planus that had been successfully treated with topicals presented with an OLP recurrence alongside difficulties eating and swallowing. Her symptoms lasted 1 year and would recur when treatment was paused. Her medical history included rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hypertension, and she was taking levothyroxine, olmesartan, and vitamin D supplements. Dentures and olmesartan previously were ruled out as potential triggers following a 2-month elimination. None of her remaining natural teeth had fillings. She also reported that neither she nor her partner had ever smoked or chewed tobacco.

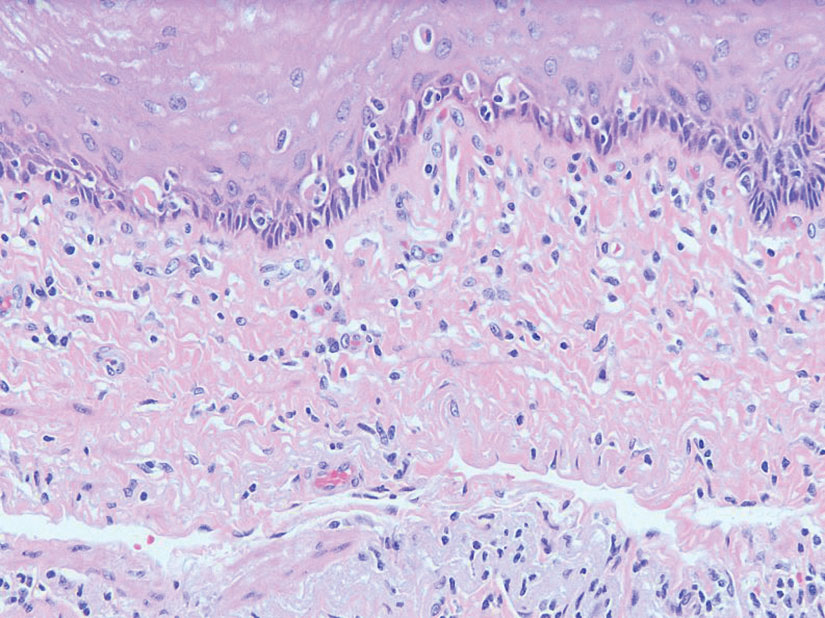

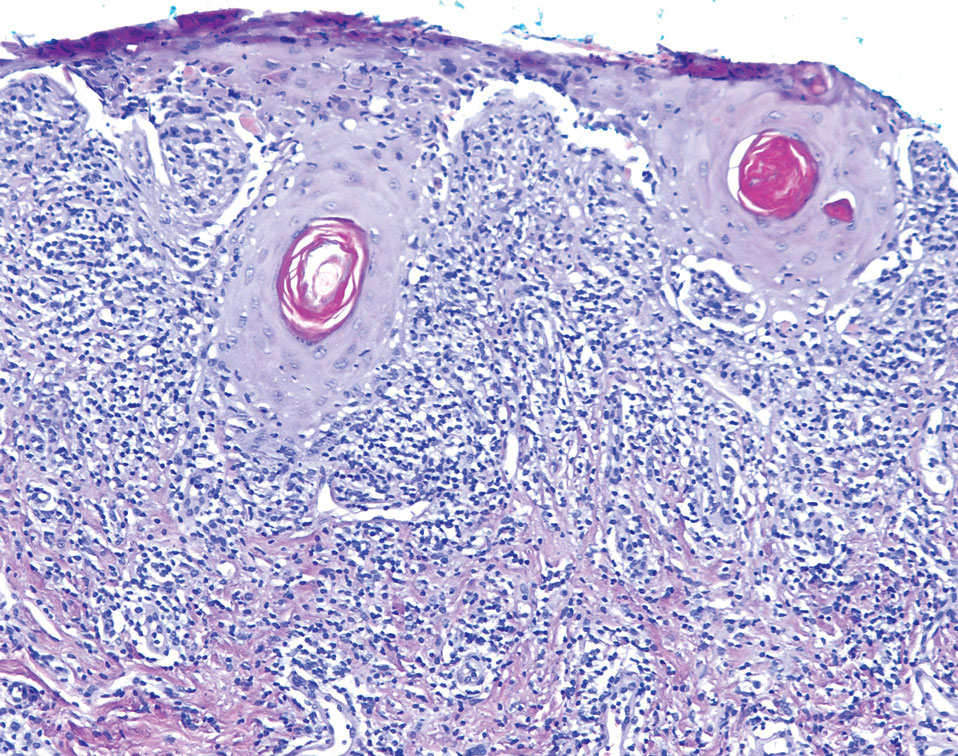

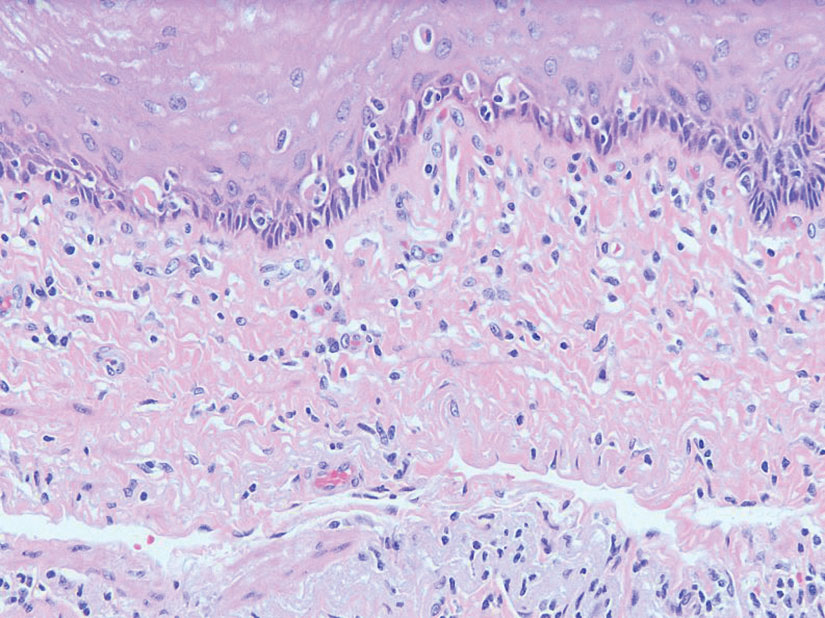

The patient’s lichen planus involvement first manifested as red, itchy, polygonal, lichenoid papules on the superior and inferior mid back 11 years prior to the current presentation (Figure 1). Further examination noted erosions on the genitalia, and a subsequent biopsy of the vulva confirmed a diagnosis of lichen planus (Figure 2). Treatment with halobetasol propionate ointment and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily (BID) resulted in remission of the CLP and vulvar lichen planus. She presented a year later with oral involvement revealing Wickham striae on the buccal mucosa and erosions on the upper palate that resolved after 2 months of treatment with cyclosporine oral solution mixed with a 5-times-daily nystatin swish-and-spit (Figure 3). The CLP did not recur but OLP was punctuated by remissions and recurrences on a yearly basis, often related to the cessation of mouthwash and topical creams. The OLP and vulvar lichen planus were successfully treated with as-needed use of a cyclosporine mouthwash swish-and-spit 3 times daily as well as halobetasol ointment 0.05% 3 times daily, respectively. Six years later, the patient was hospitalized for unrelated causes and was lost to follow-up for 2 years.

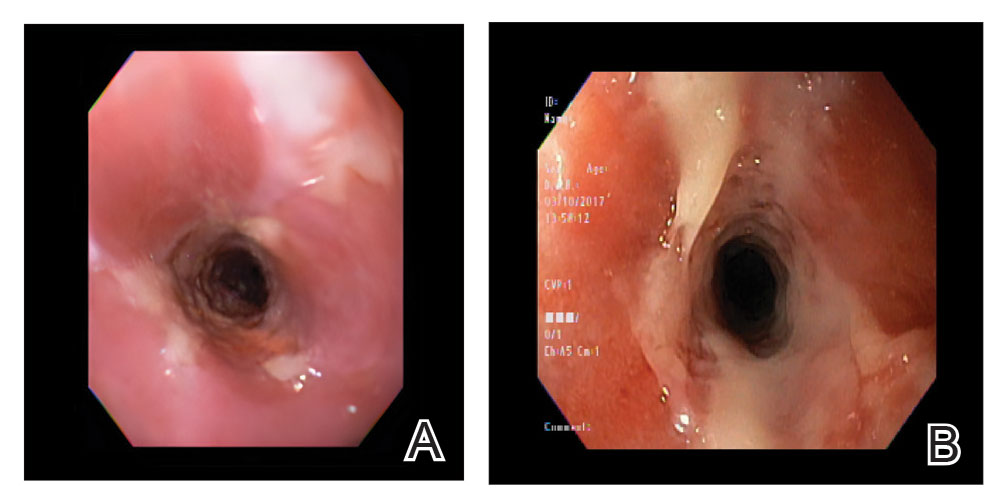

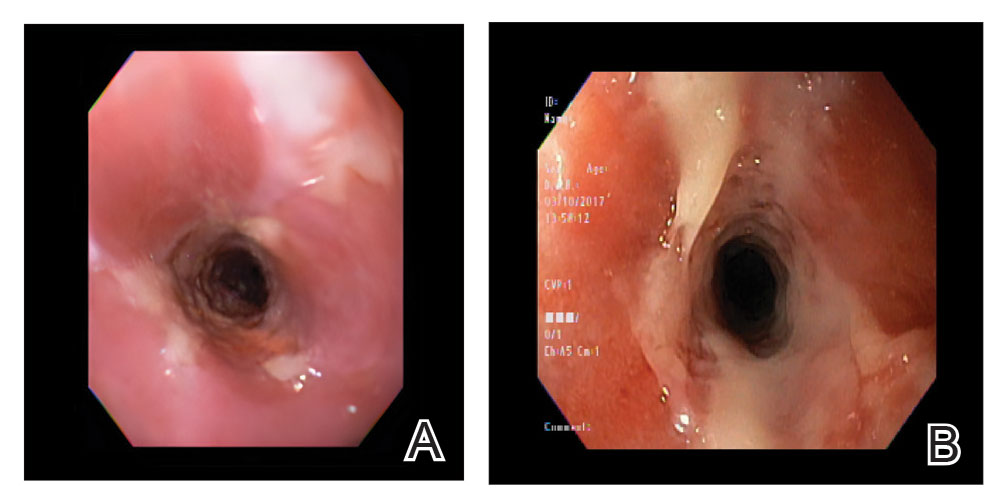

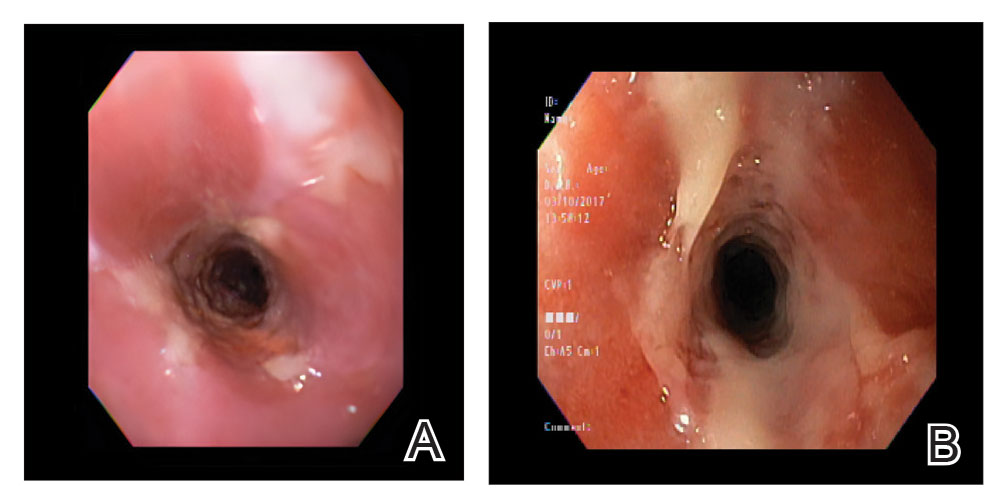

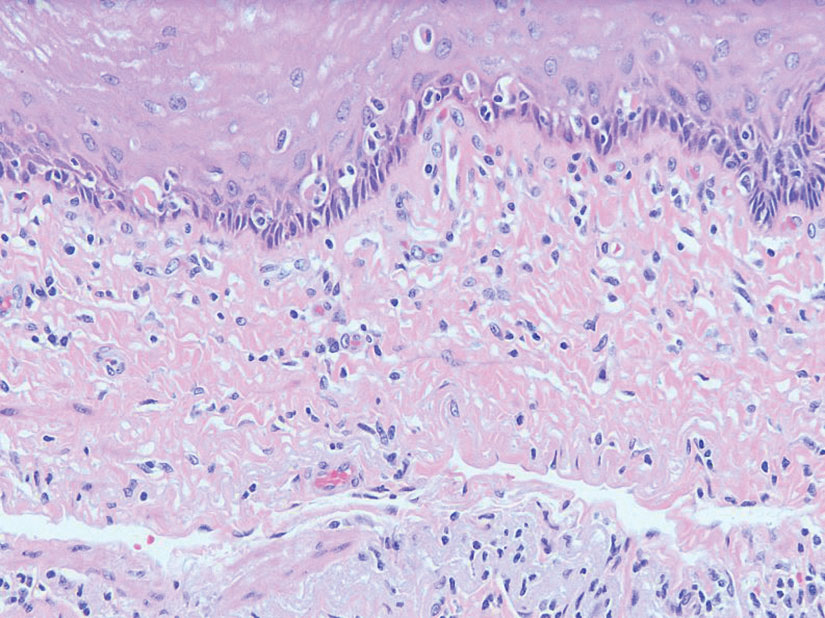

The patient experienced worsening dysphagia and odynophagia over a period of 2 years (mild dysphagia was first recorded 7 years prior to the initial presentation) and reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 pounds. An endoscopy was performed 3 years after the initial report of dysphagia and noted esophageal erosions (Figure 4A) and a stricture (Figure 4B), but all abnormal involvement was attributed to active gastroesophageal reflux disease. She underwent 8 esophageal dilations to treat the stricture but noted that the duration of symptomatic relief decreased with every subsequent dilation. An esophageal stent was placed 4 years after the initial concern of dysphagia, but it was not well tolerated and had to be removed soon thereafter. A year later, the patient underwent an esophageal bypass with a substernal gastric conduit that provided relief for 2 months but failed to permanently resolve the condition. In fact, her condition worsened over the next 1.5 years when she presented with extreme emaciation attributed to a low appetite and pain while eating. A review of the slides from a prior hospital esophageal biopsy revealed lichen planus (Figure 5). She was prescribed tofacitinib 5 mg BID as a dual-purpose treatment for the rheumatoid arthritis and OLP/ELP. At 1-month follow-up she noted that she had only taken one 5-mg pill daily without notable improvement, and after the visit she started the initial recommendation of 5 mg BID. Over the next several months, her condition continued to consistently improve; the odynophagia resolved, and she regained the majority of her lost weight. Tofacitinib was well tolerated across the course of treatment, and no adverse side effects were noted. Furthermore, the patient regained a full range of motion in the previously immobile arthritic right shoulder. She has experienced no recurrence of the genital lichen planus, OLP, or CLP since starting tofacitinib. To date, the patient is still taking only tofacitinib 5 mg BID with no recurrence of the cutaneous, mucosal, or esophageal lichen planus and has experienced no adverse events from the medication.

Comment

Clinical Presentation—Lichen planus—CLP and OLP—most frequently presents between the ages of 40 and 60 years, with a slight female predilection.1,2 The lesions typically present with the 5 P’s—purple, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques—with some lesions revealing white lacy lines overlying them called Wickham striae.6 The lesions may be red at first before turning purple. They often present on the flexural surfaces of the wrists and ankles as well as the shins and back but rarely affect the face, perhaps because of increased chronic sun exposure.2,6 Less common locations include the scalp, nails, and mucosal areas (eg, oral, vulvar, conjunctival, laryngeal, esophageal, anal).1

If CLP is diagnosed, the patient likely will also have oral lesions, which occur in 50% of patients.2 Once any form of lichen planus is found, it is important to examine all of the most frequently involved locations—mucocutaneous and cutaneous as well as the nails and scalp. Special care should be taken when examining OLP and genital lichen planus, as long-standing lesions have a 2% to 5% chance of transforming into squamous cell carcinoma.2

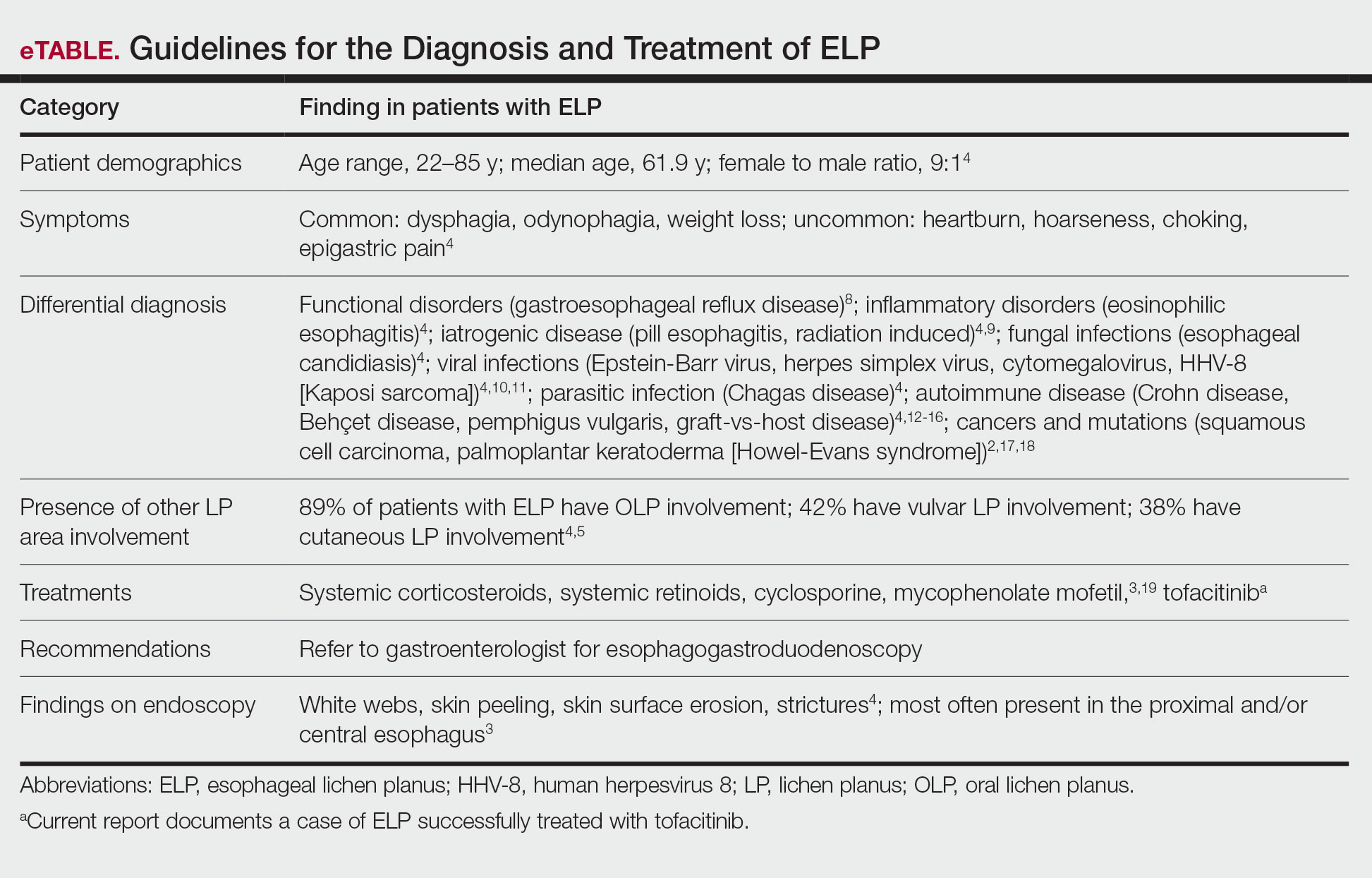

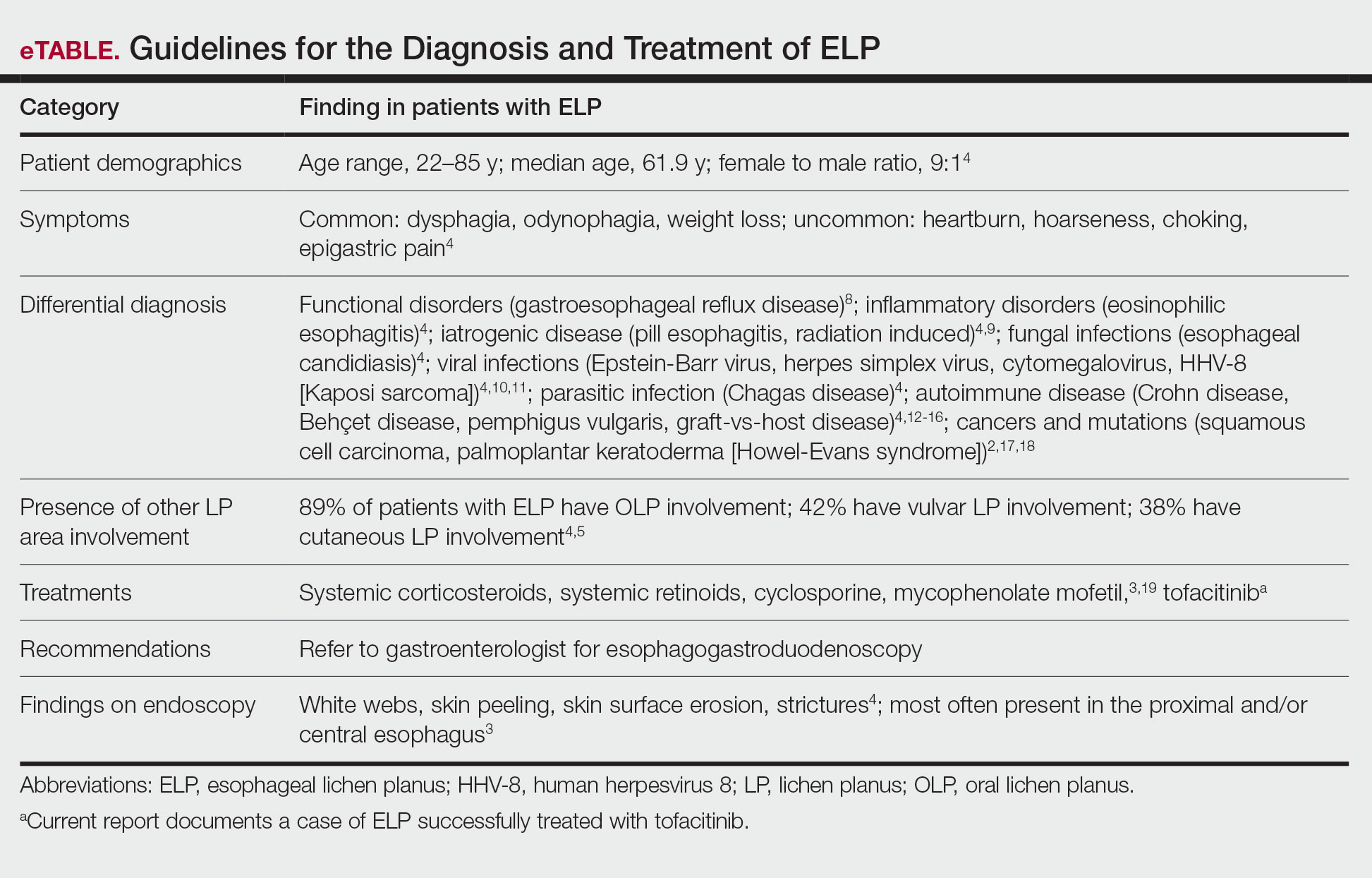

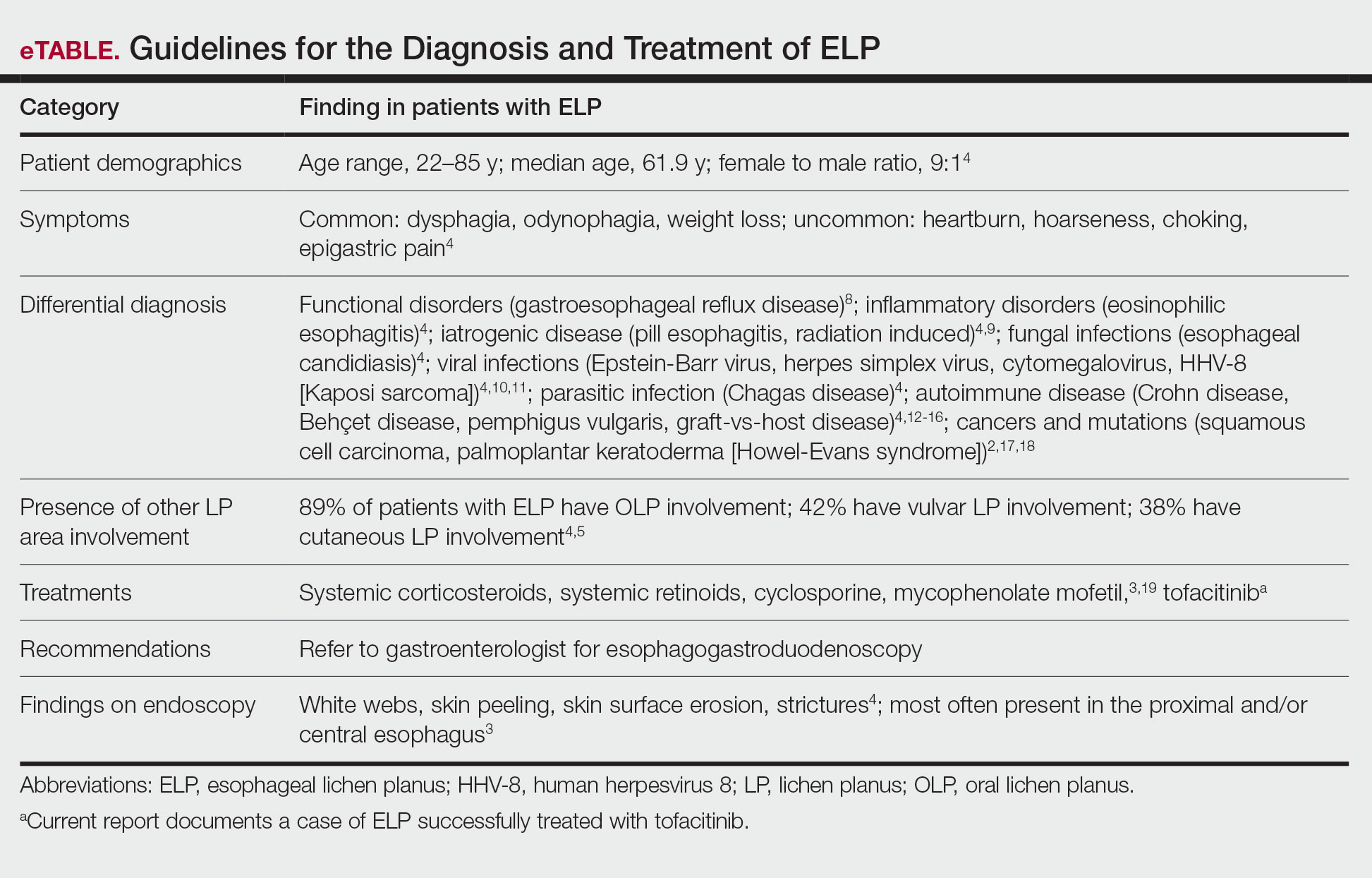

Although cases of traditional OLP and CLP are ubiquitous in the literature, ELP rarely is documented because of frequent misdiagnoses. Esophageal lichen planus has a closer histopathologic resemblance to OLP compared to CLP, and its highly variable presentation often results in an inconclusive diagnosis.3 A review of 27 patients with lichen planus highlighted the difficult nature of diagnosing ELP; ELP manifested up to 20 years after initial lichen planus diagnosis, and patients underwent an average of 2.5 dilations prior to the successful diagnosis of ELP. Interestingly, 2 patients in the study presented with ELP in isolation, which emphasizes the importance of secondary examination for lichen planus in the presence of esophageal strictures.7 The eTable provides common patient demographics and symptoms to more effectively identify ELP.Differential Diagnosis—Because lichen planus can present anywhere on the body, it may be difficult to differentiate it from other skin conditions. Clinical appearance alone often is insufficient for diagnosing lichen planus, and a punch biopsy often is needed.2,20 Cutaneous lichen planus may resemble eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, pityriasis rosea, prurigo nodularis, and psoriasis, while OLP may resemble bite trauma, leukoplakia, pemphigus, and thrush.20 Dermoscopy of the tissue makes Wickham striae easier to visualize and assists in the diagnosis of lichen planus. Furthermore, thickening of the stratum granulosum, a prevalence of lymphocytes in the dermoepidermal junction, and vacuolar alteration of the stratum basale help to distinguish between lichen planus and other inflammatory dermatoses.20 A diagnosis of lichen planus merits a full-body skin examination—hair, nails, eyes, oral mucosa, and genitalia—to rule out additional involvement.

Esophageal lichen planus most frequently presents as dysphagia, odynophagia, and weight loss, but other symptoms including heartburn, hoarseness, choking, and epigastric pain may suggest esophageal involvement.4 Typically, ELP presents in the proximal and/or central esophagus, assisting in the differentiation between ELP and other esophageal conditions.3 Special consideration should be taken when both ELP and gastroesophageal reflux disease are considered in a differential diagnosis, and it is recommended to pair an upper endoscopy with pH monitoring to avoid misdiagnosis.8 Screening endoscopies also are helpful, as they assist in identifying the characteristic white webs, skin peeling, skin surface erosion, and strictures of ELP.4 Taken together, dermatologists should encourage patients with cutaneous or mucocutaneous lichen planus to undergo an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, especially in the presence of any of ELP’s common symptoms (eTable).

Etiology—Although the exact etiology of lichen planus is not well established, there are several known correlative factors, including hepatitis C; increased stress; dental materials; oral medications, most frequently antihypertensives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; systemic diseases; and tobacco usage.6,21

Dental materials used in oral treatments such as silver amalgam, gold, cobalt, palladium, chromium, epoxy resins, and dentures can trigger or exacerbate OLP, and patch testing of a patient’s dental materials can help determine if the reaction was caused by the materials.6,22 The removal of material contributing to lesions often will cause OLP to resolve.22

It also has been suggested that the presence of thyroid disorders, autoimmune disease, various cancers, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, oral sedative usage, and/or vitamin D deficiency may be associated with OLP.21,23 Although OLP patients who were initially deficient in vitamin D demonstrated marked improvement with supplementation, it is unlikely that vitamin D supplements impacted our patient’s presentation of OLP, as she had been consistently taking them for more than 5 years with no change in OLP presentation.24

Pathogenesis—Lichen planus is thought to be a cytotoxic CD8+ T cell–mediated autoimmune disease to a virally modified epidermal self-antigen on keratinocytes. The cytotoxic T cells target the modified self-antigens on basal keratinocytes and induce apoptosis.25 The cytokine-mediated lymphocyte homing mechanism is human leukocyte antigen dependent and involves tumor necrosis factor α as well as IFN-γ and IL-1. The latter cytokines lead to upregulation of vascular adhesion molecules on endothelial vessels of subepithelial vascular plexus as well as a cascade of nonspecific mechanisms such as mast cell degranulation and matrix metalloproteinase activation, resulting in increased basement membrane disruption.6

Shao et al19 underscored the role of IFN-γ in CD8+ T cell–mediated cytotoxic cellular responses, noting that the Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway may play a key role in the pathogenesis of lichen planus. They proposed using JAK inhibitors for the treatment of lichen planus, specifically tofacitinib, a JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor, and baricitinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, as top therapeutic agents for lichen planus (eTable).19 Tofacitinib has been reported to successfully treat conditions such as psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, sarcoidosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and lichen planopilaris.26 Additionally, the efficacy of tofacitinib has been established in patients with erosive lichen planus; tofacitinib resulted in marked improvement while prednisone, acitretin, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine treatment failed.27 Although more studies on tofacitinib’s long-term efficacy, cost, and safety are necessary, tofacitinib may soon play an integral role in the battle against inflammatory dermatoses.

Conclusion

Esophageal lichen planus is an underreported form of lichen planus that often is misdiagnosed. It frequently causes dysphagia and odynophagia, resulting in a major decrease in a patient’s quality of life. We present the case of an 89-year-old woman who underwent procedures to dilate her esophagus that worsened her condition. We emphasize the importance of considering ELP in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with lichen planus in another region. In our patient, tofacitinib 5 mg BID resolved her condition without any adverse effects.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1103641

- Heath L, Matin R. Lichen planus. InnovAiT. 2017;10:133-138. doi:10.1177/1755738016686804

- Oliveira JP, Uribe NC, Abulafia LA, et al. Esophageal lichenplanus. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:394-396. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153255

- Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-183. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.029

- Quispel R, van Boxel O, Schipper M, et al. High prevalence of esophageal involvement in lichen planus: a study using magnification chromoendoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:187-193. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1119590

- Gupta S, Jawanda MK. Oral lichen planus: an update on etiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:222-229. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.156315

- Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Bruce AJ, et al. Variations in presentations of esophageal involvement in lichen planus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:777-782. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.024

- Abraham SC, Ravich WJ, Anhalt GJ, et al. Esophageal lichen planus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1678-1682. doi:10.1097/00000478-200012000-00014

- Murro D, Jakate S. Radiation esophagitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:827-830. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0111-RS

- Wilcox CM. Infectious esophagitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2006;2:567-568.

- Cancio A, Cruz C. A case of Kaposi’s sarcoma of the esophagus presenting with odynophagia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S995-S996.

- Kokturk A. Clinical and pathological manifestations with differential diagnosis in Behçet’s disease. Patholog Res Int. 2012;2012:690390. doi:10.1155/2012/690390

- Madhusudhan KS, Sharma R. Esophageal lichen planus: a case report and review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:26-27. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.39738

- Bottomley WW, Dakkak M, Walton S, et al. Esophageal involvement in Behçet’s disease. is endoscopy necessary? Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:594-597. doi:10.1007/BF01307585

- McDonald GB, Sullivan KM, Schuffler MD, et al. Esophageal abnormalities in chronic graft-versus-host disease in humans. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:914-921.

- Trabulo D, Ferreira S, Lage P, et al. Esophageal stenosis with sloughing esophagitis: a curious manifestation of graft-vs-host disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9217-9222. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9217

- Abbas H, Ghazanfar H, Ul Hussain AN, et al. Atypical presentation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma masquerading as diffuse severe esophagitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2021;15:533-538. doi:10.1159/000517129

- Ellis A, Risk JM, Maruthappu T, et al. Tylosis with oesophageal cancer: diagnosis, management and molecular mechanisms. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:126. doi:10.1186/s13023-015-0346-2

- Shao S, Tsoi LC, Sarkar MK, et al. IFN-γ enhances cell-mediated cytotoxicity against keratinocytes via JAK2/STAT1 in lichen planus. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaav7561. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aav7561

- Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53-60.

- Dave A, Shariff J, Philipone E. Association between oral lichen planus and systemic conditions and medications: case-control study. Oral Dis. 2020;27:515-524. doi:10.1111/odi.13572

- Krupaa RJ, Sankari SL, Masthan KM, et al. Oral lichen planus: an overview. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 1):S158-S161. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.155873

- Tak MM, Chalkoo AH. Vitamin D deficiency—a possible contributing factor in the aetiopathogenesis of oral lichen planus. J Evolution Med Dent Sci. 2017;6:4769-4772. doi:10.14260/jemds/2017/1033

- Gupta J, Aggarwal A, Asadullah M, et al. Vitamin D in thetreatment of oral lichen planus: a pilot clinical study. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2019;31:222-227. doi:10.4103/jiaomr.jiaomr_97_19

- Shiohara T, Moriya N, Mochizuki T, et al. Lichenoid tissue reaction (LTR) induced by local transfer of Ia-reactive T-cell clones. II. LTR by epidermal invasion of cytotoxic lymphokine-producing autoreactive T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;89:8-14.

- Sonthalia S, Aggarwal P. Oral tofacitinib: contemporary appraisal of its role in dermatology. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:503-518. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_474_18

- Damsky W, Wang A, Olamiju B, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:1708-1710.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.031

To reach early diagnoses and improve outcomes in cases of mucosal and esophageal lichen planus (ELP), patient education along with a multidisciplinary approach centered on collaboration among dermatologists, gastroenterologists, gynecologists, and dental practitioners should be a priority. Tofacitinib therapy should be considered in the treatment of patients presenting with cutaneous lichen planus (CLP), mucosal lichen planus, and ELP.

Lichen planus is a papulosquamous disease of the skin and mucous membranes that is most common on the skin and oral mucosa. Typical lesions of CLP present as purple, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques on the flexural surfaces of the wrists and ankles as well as areas of friction or trauma due to scratching such as the shins and lower back. Various subtypes of lichen planus can present simultaneously, resulting in extensive involvement that worsens through koebnerization and affects the oral cavity, esophagus, larynx, sclera, genitalia, scalp, and nails.1,2

Esophageal lichen planus can develop with or without the presence of CLP, oral lichen planus (OLP), or genital lichen planus.3 It typically affects women older than 50 years and is linked to OLP and vulvar lichen planus, with 1 study reporting that 87% (63/72) of ELP patients were women with a median age of 61.9 years at the time of diagnosis (range, 22–85 years). Almost all ELP patients in the study had lichen planus symptoms in other locations; 89% (64/72) had OLP, and 42% (30/72) had vulvar lichen planus.4 Consequently, a diagnosis of ELP should be followed by a thorough full-body examination to check for lichen planus at other sites. Studies that examined lichen planus patients for ELP found that 25% to 50% of patients diagnosed with orocutaneous lichen planus also had ELP, with ELP frequently presenting without symptoms.3,5 These findings indicate that ELP likely is underdiagnosed and often misdiagnosed, resulting in an underestimation of its prevalence.

Our case highlights a frequently misdiagnosed condition and underscores the importance of close examination of patients presenting with CLP and OLP for signs and symptoms of ELP. Furthermore, we discuss the importance of patient education and collaboration among different specialties in attaining an early diagnosis to improve patient outcomes. Finally, we review the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of CLP, OLP, and ELP, as well as the utility of tofacitinib for ELP.

Case Report

An emaciated 89-year-old woman with an 11-year history of CLP, OLP, and genital lichen planus that had been successfully treated with topicals presented with an OLP recurrence alongside difficulties eating and swallowing. Her symptoms lasted 1 year and would recur when treatment was paused. Her medical history included rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hypertension, and she was taking levothyroxine, olmesartan, and vitamin D supplements. Dentures and olmesartan previously were ruled out as potential triggers following a 2-month elimination. None of her remaining natural teeth had fillings. She also reported that neither she nor her partner had ever smoked or chewed tobacco.

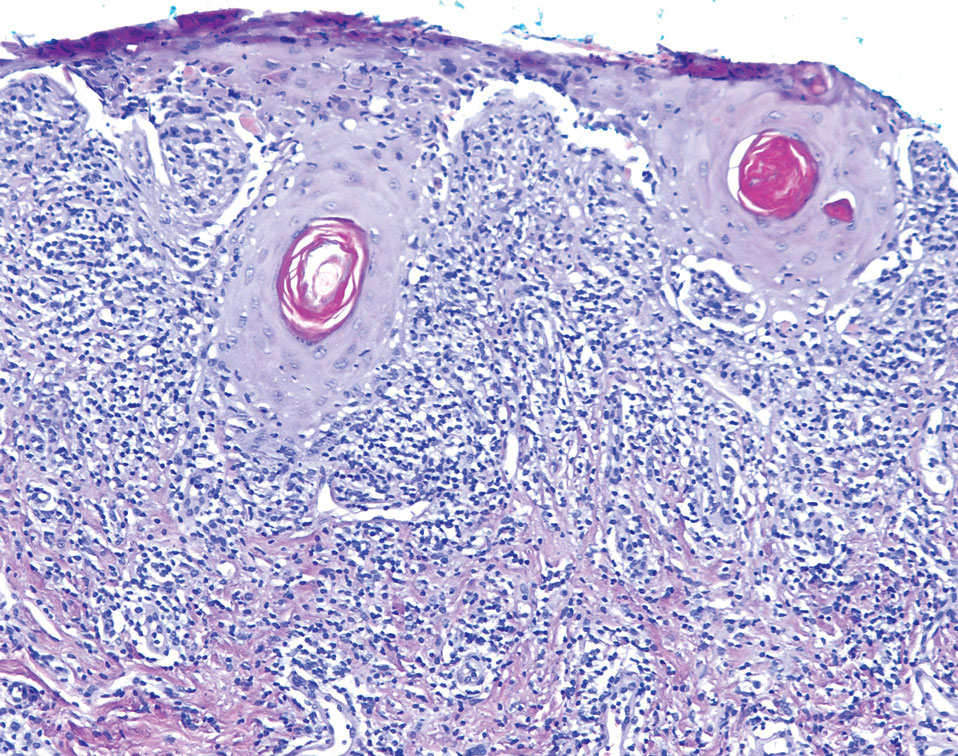

The patient’s lichen planus involvement first manifested as red, itchy, polygonal, lichenoid papules on the superior and inferior mid back 11 years prior to the current presentation (Figure 1). Further examination noted erosions on the genitalia, and a subsequent biopsy of the vulva confirmed a diagnosis of lichen planus (Figure 2). Treatment with halobetasol propionate ointment and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily (BID) resulted in remission of the CLP and vulvar lichen planus. She presented a year later with oral involvement revealing Wickham striae on the buccal mucosa and erosions on the upper palate that resolved after 2 months of treatment with cyclosporine oral solution mixed with a 5-times-daily nystatin swish-and-spit (Figure 3). The CLP did not recur but OLP was punctuated by remissions and recurrences on a yearly basis, often related to the cessation of mouthwash and topical creams. The OLP and vulvar lichen planus were successfully treated with as-needed use of a cyclosporine mouthwash swish-and-spit 3 times daily as well as halobetasol ointment 0.05% 3 times daily, respectively. Six years later, the patient was hospitalized for unrelated causes and was lost to follow-up for 2 years.

The patient experienced worsening dysphagia and odynophagia over a period of 2 years (mild dysphagia was first recorded 7 years prior to the initial presentation) and reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 pounds. An endoscopy was performed 3 years after the initial report of dysphagia and noted esophageal erosions (Figure 4A) and a stricture (Figure 4B), but all abnormal involvement was attributed to active gastroesophageal reflux disease. She underwent 8 esophageal dilations to treat the stricture but noted that the duration of symptomatic relief decreased with every subsequent dilation. An esophageal stent was placed 4 years after the initial concern of dysphagia, but it was not well tolerated and had to be removed soon thereafter. A year later, the patient underwent an esophageal bypass with a substernal gastric conduit that provided relief for 2 months but failed to permanently resolve the condition. In fact, her condition worsened over the next 1.5 years when she presented with extreme emaciation attributed to a low appetite and pain while eating. A review of the slides from a prior hospital esophageal biopsy revealed lichen planus (Figure 5). She was prescribed tofacitinib 5 mg BID as a dual-purpose treatment for the rheumatoid arthritis and OLP/ELP. At 1-month follow-up she noted that she had only taken one 5-mg pill daily without notable improvement, and after the visit she started the initial recommendation of 5 mg BID. Over the next several months, her condition continued to consistently improve; the odynophagia resolved, and she regained the majority of her lost weight. Tofacitinib was well tolerated across the course of treatment, and no adverse side effects were noted. Furthermore, the patient regained a full range of motion in the previously immobile arthritic right shoulder. She has experienced no recurrence of the genital lichen planus, OLP, or CLP since starting tofacitinib. To date, the patient is still taking only tofacitinib 5 mg BID with no recurrence of the cutaneous, mucosal, or esophageal lichen planus and has experienced no adverse events from the medication.

Comment

Clinical Presentation—Lichen planus—CLP and OLP—most frequently presents between the ages of 40 and 60 years, with a slight female predilection.1,2 The lesions typically present with the 5 P’s—purple, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques—with some lesions revealing white lacy lines overlying them called Wickham striae.6 The lesions may be red at first before turning purple. They often present on the flexural surfaces of the wrists and ankles as well as the shins and back but rarely affect the face, perhaps because of increased chronic sun exposure.2,6 Less common locations include the scalp, nails, and mucosal areas (eg, oral, vulvar, conjunctival, laryngeal, esophageal, anal).1

If CLP is diagnosed, the patient likely will also have oral lesions, which occur in 50% of patients.2 Once any form of lichen planus is found, it is important to examine all of the most frequently involved locations—mucocutaneous and cutaneous as well as the nails and scalp. Special care should be taken when examining OLP and genital lichen planus, as long-standing lesions have a 2% to 5% chance of transforming into squamous cell carcinoma.2

Although cases of traditional OLP and CLP are ubiquitous in the literature, ELP rarely is documented because of frequent misdiagnoses. Esophageal lichen planus has a closer histopathologic resemblance to OLP compared to CLP, and its highly variable presentation often results in an inconclusive diagnosis.3 A review of 27 patients with lichen planus highlighted the difficult nature of diagnosing ELP; ELP manifested up to 20 years after initial lichen planus diagnosis, and patients underwent an average of 2.5 dilations prior to the successful diagnosis of ELP. Interestingly, 2 patients in the study presented with ELP in isolation, which emphasizes the importance of secondary examination for lichen planus in the presence of esophageal strictures.7 The eTable provides common patient demographics and symptoms to more effectively identify ELP.Differential Diagnosis—Because lichen planus can present anywhere on the body, it may be difficult to differentiate it from other skin conditions. Clinical appearance alone often is insufficient for diagnosing lichen planus, and a punch biopsy often is needed.2,20 Cutaneous lichen planus may resemble eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, pityriasis rosea, prurigo nodularis, and psoriasis, while OLP may resemble bite trauma, leukoplakia, pemphigus, and thrush.20 Dermoscopy of the tissue makes Wickham striae easier to visualize and assists in the diagnosis of lichen planus. Furthermore, thickening of the stratum granulosum, a prevalence of lymphocytes in the dermoepidermal junction, and vacuolar alteration of the stratum basale help to distinguish between lichen planus and other inflammatory dermatoses.20 A diagnosis of lichen planus merits a full-body skin examination—hair, nails, eyes, oral mucosa, and genitalia—to rule out additional involvement.

Esophageal lichen planus most frequently presents as dysphagia, odynophagia, and weight loss, but other symptoms including heartburn, hoarseness, choking, and epigastric pain may suggest esophageal involvement.4 Typically, ELP presents in the proximal and/or central esophagus, assisting in the differentiation between ELP and other esophageal conditions.3 Special consideration should be taken when both ELP and gastroesophageal reflux disease are considered in a differential diagnosis, and it is recommended to pair an upper endoscopy with pH monitoring to avoid misdiagnosis.8 Screening endoscopies also are helpful, as they assist in identifying the characteristic white webs, skin peeling, skin surface erosion, and strictures of ELP.4 Taken together, dermatologists should encourage patients with cutaneous or mucocutaneous lichen planus to undergo an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, especially in the presence of any of ELP’s common symptoms (eTable).

Etiology—Although the exact etiology of lichen planus is not well established, there are several known correlative factors, including hepatitis C; increased stress; dental materials; oral medications, most frequently antihypertensives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; systemic diseases; and tobacco usage.6,21

Dental materials used in oral treatments such as silver amalgam, gold, cobalt, palladium, chromium, epoxy resins, and dentures can trigger or exacerbate OLP, and patch testing of a patient’s dental materials can help determine if the reaction was caused by the materials.6,22 The removal of material contributing to lesions often will cause OLP to resolve.22

It also has been suggested that the presence of thyroid disorders, autoimmune disease, various cancers, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, oral sedative usage, and/or vitamin D deficiency may be associated with OLP.21,23 Although OLP patients who were initially deficient in vitamin D demonstrated marked improvement with supplementation, it is unlikely that vitamin D supplements impacted our patient’s presentation of OLP, as she had been consistently taking them for more than 5 years with no change in OLP presentation.24

Pathogenesis—Lichen planus is thought to be a cytotoxic CD8+ T cell–mediated autoimmune disease to a virally modified epidermal self-antigen on keratinocytes. The cytotoxic T cells target the modified self-antigens on basal keratinocytes and induce apoptosis.25 The cytokine-mediated lymphocyte homing mechanism is human leukocyte antigen dependent and involves tumor necrosis factor α as well as IFN-γ and IL-1. The latter cytokines lead to upregulation of vascular adhesion molecules on endothelial vessels of subepithelial vascular plexus as well as a cascade of nonspecific mechanisms such as mast cell degranulation and matrix metalloproteinase activation, resulting in increased basement membrane disruption.6

Shao et al19 underscored the role of IFN-γ in CD8+ T cell–mediated cytotoxic cellular responses, noting that the Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway may play a key role in the pathogenesis of lichen planus. They proposed using JAK inhibitors for the treatment of lichen planus, specifically tofacitinib, a JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor, and baricitinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, as top therapeutic agents for lichen planus (eTable).19 Tofacitinib has been reported to successfully treat conditions such as psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, sarcoidosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and lichen planopilaris.26 Additionally, the efficacy of tofacitinib has been established in patients with erosive lichen planus; tofacitinib resulted in marked improvement while prednisone, acitretin, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine treatment failed.27 Although more studies on tofacitinib’s long-term efficacy, cost, and safety are necessary, tofacitinib may soon play an integral role in the battle against inflammatory dermatoses.

Conclusion

Esophageal lichen planus is an underreported form of lichen planus that often is misdiagnosed. It frequently causes dysphagia and odynophagia, resulting in a major decrease in a patient’s quality of life. We present the case of an 89-year-old woman who underwent procedures to dilate her esophagus that worsened her condition. We emphasize the importance of considering ELP in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with lichen planus in another region. In our patient, tofacitinib 5 mg BID resolved her condition without any adverse effects.

To reach early diagnoses and improve outcomes in cases of mucosal and esophageal lichen planus (ELP), patient education along with a multidisciplinary approach centered on collaboration among dermatologists, gastroenterologists, gynecologists, and dental practitioners should be a priority. Tofacitinib therapy should be considered in the treatment of patients presenting with cutaneous lichen planus (CLP), mucosal lichen planus, and ELP.

Lichen planus is a papulosquamous disease of the skin and mucous membranes that is most common on the skin and oral mucosa. Typical lesions of CLP present as purple, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques on the flexural surfaces of the wrists and ankles as well as areas of friction or trauma due to scratching such as the shins and lower back. Various subtypes of lichen planus can present simultaneously, resulting in extensive involvement that worsens through koebnerization and affects the oral cavity, esophagus, larynx, sclera, genitalia, scalp, and nails.1,2

Esophageal lichen planus can develop with or without the presence of CLP, oral lichen planus (OLP), or genital lichen planus.3 It typically affects women older than 50 years and is linked to OLP and vulvar lichen planus, with 1 study reporting that 87% (63/72) of ELP patients were women with a median age of 61.9 years at the time of diagnosis (range, 22–85 years). Almost all ELP patients in the study had lichen planus symptoms in other locations; 89% (64/72) had OLP, and 42% (30/72) had vulvar lichen planus.4 Consequently, a diagnosis of ELP should be followed by a thorough full-body examination to check for lichen planus at other sites. Studies that examined lichen planus patients for ELP found that 25% to 50% of patients diagnosed with orocutaneous lichen planus also had ELP, with ELP frequently presenting without symptoms.3,5 These findings indicate that ELP likely is underdiagnosed and often misdiagnosed, resulting in an underestimation of its prevalence.

Our case highlights a frequently misdiagnosed condition and underscores the importance of close examination of patients presenting with CLP and OLP for signs and symptoms of ELP. Furthermore, we discuss the importance of patient education and collaboration among different specialties in attaining an early diagnosis to improve patient outcomes. Finally, we review the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of CLP, OLP, and ELP, as well as the utility of tofacitinib for ELP.

Case Report

An emaciated 89-year-old woman with an 11-year history of CLP, OLP, and genital lichen planus that had been successfully treated with topicals presented with an OLP recurrence alongside difficulties eating and swallowing. Her symptoms lasted 1 year and would recur when treatment was paused. Her medical history included rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hypertension, and she was taking levothyroxine, olmesartan, and vitamin D supplements. Dentures and olmesartan previously were ruled out as potential triggers following a 2-month elimination. None of her remaining natural teeth had fillings. She also reported that neither she nor her partner had ever smoked or chewed tobacco.

The patient’s lichen planus involvement first manifested as red, itchy, polygonal, lichenoid papules on the superior and inferior mid back 11 years prior to the current presentation (Figure 1). Further examination noted erosions on the genitalia, and a subsequent biopsy of the vulva confirmed a diagnosis of lichen planus (Figure 2). Treatment with halobetasol propionate ointment and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily (BID) resulted in remission of the CLP and vulvar lichen planus. She presented a year later with oral involvement revealing Wickham striae on the buccal mucosa and erosions on the upper palate that resolved after 2 months of treatment with cyclosporine oral solution mixed with a 5-times-daily nystatin swish-and-spit (Figure 3). The CLP did not recur but OLP was punctuated by remissions and recurrences on a yearly basis, often related to the cessation of mouthwash and topical creams. The OLP and vulvar lichen planus were successfully treated with as-needed use of a cyclosporine mouthwash swish-and-spit 3 times daily as well as halobetasol ointment 0.05% 3 times daily, respectively. Six years later, the patient was hospitalized for unrelated causes and was lost to follow-up for 2 years.

The patient experienced worsening dysphagia and odynophagia over a period of 2 years (mild dysphagia was first recorded 7 years prior to the initial presentation) and reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 pounds. An endoscopy was performed 3 years after the initial report of dysphagia and noted esophageal erosions (Figure 4A) and a stricture (Figure 4B), but all abnormal involvement was attributed to active gastroesophageal reflux disease. She underwent 8 esophageal dilations to treat the stricture but noted that the duration of symptomatic relief decreased with every subsequent dilation. An esophageal stent was placed 4 years after the initial concern of dysphagia, but it was not well tolerated and had to be removed soon thereafter. A year later, the patient underwent an esophageal bypass with a substernal gastric conduit that provided relief for 2 months but failed to permanently resolve the condition. In fact, her condition worsened over the next 1.5 years when she presented with extreme emaciation attributed to a low appetite and pain while eating. A review of the slides from a prior hospital esophageal biopsy revealed lichen planus (Figure 5). She was prescribed tofacitinib 5 mg BID as a dual-purpose treatment for the rheumatoid arthritis and OLP/ELP. At 1-month follow-up she noted that she had only taken one 5-mg pill daily without notable improvement, and after the visit she started the initial recommendation of 5 mg BID. Over the next several months, her condition continued to consistently improve; the odynophagia resolved, and she regained the majority of her lost weight. Tofacitinib was well tolerated across the course of treatment, and no adverse side effects were noted. Furthermore, the patient regained a full range of motion in the previously immobile arthritic right shoulder. She has experienced no recurrence of the genital lichen planus, OLP, or CLP since starting tofacitinib. To date, the patient is still taking only tofacitinib 5 mg BID with no recurrence of the cutaneous, mucosal, or esophageal lichen planus and has experienced no adverse events from the medication.

Comment

Clinical Presentation—Lichen planus—CLP and OLP—most frequently presents between the ages of 40 and 60 years, with a slight female predilection.1,2 The lesions typically present with the 5 P’s—purple, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques—with some lesions revealing white lacy lines overlying them called Wickham striae.6 The lesions may be red at first before turning purple. They often present on the flexural surfaces of the wrists and ankles as well as the shins and back but rarely affect the face, perhaps because of increased chronic sun exposure.2,6 Less common locations include the scalp, nails, and mucosal areas (eg, oral, vulvar, conjunctival, laryngeal, esophageal, anal).1

If CLP is diagnosed, the patient likely will also have oral lesions, which occur in 50% of patients.2 Once any form of lichen planus is found, it is important to examine all of the most frequently involved locations—mucocutaneous and cutaneous as well as the nails and scalp. Special care should be taken when examining OLP and genital lichen planus, as long-standing lesions have a 2% to 5% chance of transforming into squamous cell carcinoma.2

Although cases of traditional OLP and CLP are ubiquitous in the literature, ELP rarely is documented because of frequent misdiagnoses. Esophageal lichen planus has a closer histopathologic resemblance to OLP compared to CLP, and its highly variable presentation often results in an inconclusive diagnosis.3 A review of 27 patients with lichen planus highlighted the difficult nature of diagnosing ELP; ELP manifested up to 20 years after initial lichen planus diagnosis, and patients underwent an average of 2.5 dilations prior to the successful diagnosis of ELP. Interestingly, 2 patients in the study presented with ELP in isolation, which emphasizes the importance of secondary examination for lichen planus in the presence of esophageal strictures.7 The eTable provides common patient demographics and symptoms to more effectively identify ELP.Differential Diagnosis—Because lichen planus can present anywhere on the body, it may be difficult to differentiate it from other skin conditions. Clinical appearance alone often is insufficient for diagnosing lichen planus, and a punch biopsy often is needed.2,20 Cutaneous lichen planus may resemble eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, pityriasis rosea, prurigo nodularis, and psoriasis, while OLP may resemble bite trauma, leukoplakia, pemphigus, and thrush.20 Dermoscopy of the tissue makes Wickham striae easier to visualize and assists in the diagnosis of lichen planus. Furthermore, thickening of the stratum granulosum, a prevalence of lymphocytes in the dermoepidermal junction, and vacuolar alteration of the stratum basale help to distinguish between lichen planus and other inflammatory dermatoses.20 A diagnosis of lichen planus merits a full-body skin examination—hair, nails, eyes, oral mucosa, and genitalia—to rule out additional involvement.

Esophageal lichen planus most frequently presents as dysphagia, odynophagia, and weight loss, but other symptoms including heartburn, hoarseness, choking, and epigastric pain may suggest esophageal involvement.4 Typically, ELP presents in the proximal and/or central esophagus, assisting in the differentiation between ELP and other esophageal conditions.3 Special consideration should be taken when both ELP and gastroesophageal reflux disease are considered in a differential diagnosis, and it is recommended to pair an upper endoscopy with pH monitoring to avoid misdiagnosis.8 Screening endoscopies also are helpful, as they assist in identifying the characteristic white webs, skin peeling, skin surface erosion, and strictures of ELP.4 Taken together, dermatologists should encourage patients with cutaneous or mucocutaneous lichen planus to undergo an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, especially in the presence of any of ELP’s common symptoms (eTable).

Etiology—Although the exact etiology of lichen planus is not well established, there are several known correlative factors, including hepatitis C; increased stress; dental materials; oral medications, most frequently antihypertensives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; systemic diseases; and tobacco usage.6,21

Dental materials used in oral treatments such as silver amalgam, gold, cobalt, palladium, chromium, epoxy resins, and dentures can trigger or exacerbate OLP, and patch testing of a patient’s dental materials can help determine if the reaction was caused by the materials.6,22 The removal of material contributing to lesions often will cause OLP to resolve.22

It also has been suggested that the presence of thyroid disorders, autoimmune disease, various cancers, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, oral sedative usage, and/or vitamin D deficiency may be associated with OLP.21,23 Although OLP patients who were initially deficient in vitamin D demonstrated marked improvement with supplementation, it is unlikely that vitamin D supplements impacted our patient’s presentation of OLP, as she had been consistently taking them for more than 5 years with no change in OLP presentation.24

Pathogenesis—Lichen planus is thought to be a cytotoxic CD8+ T cell–mediated autoimmune disease to a virally modified epidermal self-antigen on keratinocytes. The cytotoxic T cells target the modified self-antigens on basal keratinocytes and induce apoptosis.25 The cytokine-mediated lymphocyte homing mechanism is human leukocyte antigen dependent and involves tumor necrosis factor α as well as IFN-γ and IL-1. The latter cytokines lead to upregulation of vascular adhesion molecules on endothelial vessels of subepithelial vascular plexus as well as a cascade of nonspecific mechanisms such as mast cell degranulation and matrix metalloproteinase activation, resulting in increased basement membrane disruption.6