User login

Dermatology Residency Applications: Correlation of Applicant Personal Statement Content With Match Result

The personal statement is a narrative written by an applicant to residency programs to discuss his/her interests. It is one of the few places in the residency application process where applicants can express their personalities.1 Applicants believe the personal statement is an important opportunity to distinguish themselves from others, thus increasing their chances of successful matching, particularly in competitive specialties.1,2

Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty, with 614 medical students applying for 440 total dermatology positions in 2016.3 According to the results of the 2016 National Resident Matching program director survey, 82% (27/33) of dermatology program directors reported that the personal statement was a factor in selecting applicants to interview. Furthermore, dermatology program directors, on average, rated personal statements as more important than the Medical Student Performance Evaluation/Dean’s Letter, US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 scores, and class ranking/quartile.4

Prior studies have sought to evaluate the impact of personal statements on the application process. A 2014 study of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants found that the prevalence of certain themes differed according to match outcome.5 However, some of the conclusions drawn in this study were not supported by the reported results or were based on low numbers of participants. The purpose of our study was to examine personal statements from applications to a dermatology program at a major academic institution. This study identified common themes in personal statements, allowing for an analysis of their association with successful matching into dermatology.

Methods

All applications to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, North Carolina) during the 2012 application cycle (N=422) were eligible. All submitted personal statements (N=422) were included with all personal identifiers removed prior to analysis. The investigator (D.S.M.) was blinded to other Electronic Residency Application Service data and match outcome.

The investigator initially reviewed a small, randomly selected subset of 20 personal statements to identify characteristics and common themes. The investigator then analyzed each of the personal statements to quantify the frequency of each theme. All personal statements submitted to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine were analyzed in this manner. Dermatology match outcomes for each applicant were confirmed later using dermatology program websites.

Differences in the prevalence of common themes between matched and unmatched applicants were calculated. Analysis of variance tests were used to determine if the differences in prevalence were statistically significant (P≤.05).

Results

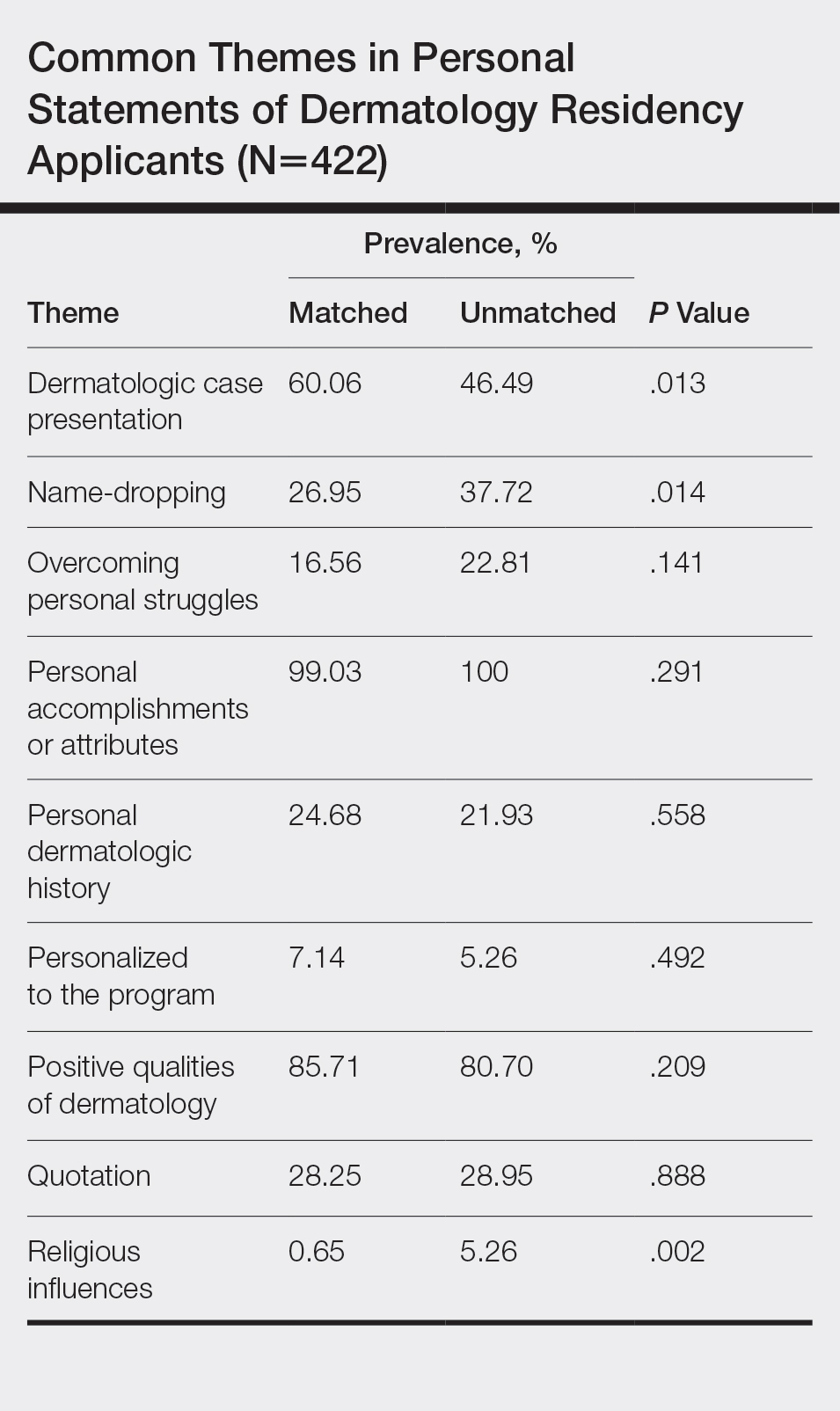

All 422 submitted personal statements were evaluated, with 308 personal statements from applicants who matched and 114 personal statements from unmatched applicants. The screening of the initial subset of 20 personal statements resulted in a total of 9 content themes. The prevalence of each theme among matched and unmatched applicants is shown in the Table.

The most common themes among both matched and unmatched groups were personal accomplishments or attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. The prevalence of certain themes varied between matched and unmatched groups. Dermatologic cases were discussed significantly more frequently in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (60.06% vs 46.49%, P=.013). Name-dropping was more prevalent in the unmatched group (37.72%) compared to the matched group (26.95%). This difference in prevalence reached statistical significance (P=.014). Religious influences also were discussed more frequently in the unmatched group (5.26%) vs the matched group (0.65%) with statistical significance (P=.002).

Comment

This study of 422 personal statements submitted to a major academic institution showed that certain themes were common in personal statements among both matched and unmatched applicants. These themes included personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. This finding is consistent with prior studies that show common themes in the personal statements of applicants across a wide variety of specialties, including dermatology, anesthesiology, pediatrics, general surgery, internal medicine, and radiology.5-10 Most commonly, applicants feel the need to justify why they chose their particular specialty, with Olazagasti et al5 (N=332) reporting that 70% of submitted dermatology personal statements explained why the applicant chose dermatology.

Certain themes, however, varied in prevalence between matched and unmatched groups in our study. Discussion of dermatologic cases was significantly more prevalent in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (P=.013), possibly because dermatology faculty enjoy hearing about cases and how the applicant responds and interacts with the cases. These data suggest that matched applicants focus more on characteristics specific to the clinical aspects of dermatology.

Conversely, name-dropping was significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.014). Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty. In 2016, applicants who matched into dermatology had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 249 with a mean number of 4.7 research experiences and 11.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications, which is higher than the average USMLE Step 1 score of 239 with a mean number of 3.8 research experiences and 8.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications for unmatched applicants.3 It is possible that residency selection committees may view name-dropping negatively if applicants choose to name-drop to strengthen their applications in comparison to more competitive candidates. Religious influences also were significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.002), but the overall frequency of religious influences was low (approximately 2% of all applicants).

The 422 personal statements examined in our study represent 83.1% of the total pool of applicants to postgraduate year 2 dermatology positions in 2012 (N=508).11 Our data differed somewhat from an analysis of same-year dermatology personal statements of 65% of the national applicant pool.5 Olazagasti et al5 found that themes of a family member in medicine (more in unmatched), a desire to contribute to decreasing literature gap (more in matched), and a desire to better understand dermatologic pathophysiology (more in matched) to be statistically significant (P≤.05 for all). Unfortunately, these themes were found in a small number of applicants, with each being reported in less than 7%.5 Our study included 23% more unmatched candidates and likely better estimated potential significant differences between matched and unmatched applicants.

In the Results section, Olazagasti et al5 reported that matched applicants emphasized the study of cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease significantly more frequently than unmatched applicants. However, the P value in their report did not support this statement (P=.054). In addition, their Conclusion section discussed matched candidates including themes of “why dermatology” and unmatched candidates including a “personal story” as differences between groups. Again, their results did not show any statistical significance to support these recommendations.5 When providing medical student mentorship in a field as competitive as dermatology, faculty must be careful in giving accurate advice that, if at all possible, is supported by objective data rather than personal preference or anecdotes.

Our study was limited in that only personal statements of applicants to a single program in a specific specialty were analyzed. Applicants may have submitted personalized versions of their personal statements to specific schools, which may have biased the themes present in this subset of personal statements. Given these limitations, we are unable to determine if these results are generalizable to all dermatology residency applicants. Further limitation is that the analysis of personal statements is in itself a subjective process.

This study included a larger number of personal statements representing a larger proportion of the total pool of applicants in 2012 than prior studies examining personal statements of dermatology residency applicants. In addition, this study examined the ultimate dermatology match outcome for each applicant during the 2012 application cycle. Future investigations could explore the role of other factors in the residency selection process such as USMLE Step scores, community service, research experiences, and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society status.

Conclusion

There are common themes in the personal statements of dermatology residency applicants, including personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. In addition, discussion of dermatologic cases was statistically more prevalent in applicants who ultimately matched, whereas name-dropping and religious influences were more prevalent in applicants who did not match. This information may be useful to effectively mentor medical students about the writing process for the personal statement. Further investigation is needed to explore these associations and the role of other aspects of the application in the residency selection process.

- Arbelaez C, Ganguli I. The personal statement for residency application: review and guidance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:439-442.

- White BA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, et al. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340-343.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match for U.S. Allopathic Seniors: Characteristics of US Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2016 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; September 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; June 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Olazagasti J, Gorouhi F, Fazel N. A critical review of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:934874.

- Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, et al. Have personal statements become impersonal? an evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346-351.

- Nield LS, Nease EK, Mitra S, et al. Major themes in the personal statements of pediatric resident applicants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:671-672.

- Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, et al. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:573-581.

- Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, et al. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93-102.

- Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, et al. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1024-1028.

- Results and Data: 2012 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; April 2012. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata20121.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

The personal statement is a narrative written by an applicant to residency programs to discuss his/her interests. It is one of the few places in the residency application process where applicants can express their personalities.1 Applicants believe the personal statement is an important opportunity to distinguish themselves from others, thus increasing their chances of successful matching, particularly in competitive specialties.1,2

Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty, with 614 medical students applying for 440 total dermatology positions in 2016.3 According to the results of the 2016 National Resident Matching program director survey, 82% (27/33) of dermatology program directors reported that the personal statement was a factor in selecting applicants to interview. Furthermore, dermatology program directors, on average, rated personal statements as more important than the Medical Student Performance Evaluation/Dean’s Letter, US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 scores, and class ranking/quartile.4

Prior studies have sought to evaluate the impact of personal statements on the application process. A 2014 study of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants found that the prevalence of certain themes differed according to match outcome.5 However, some of the conclusions drawn in this study were not supported by the reported results or were based on low numbers of participants. The purpose of our study was to examine personal statements from applications to a dermatology program at a major academic institution. This study identified common themes in personal statements, allowing for an analysis of their association with successful matching into dermatology.

Methods

All applications to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, North Carolina) during the 2012 application cycle (N=422) were eligible. All submitted personal statements (N=422) were included with all personal identifiers removed prior to analysis. The investigator (D.S.M.) was blinded to other Electronic Residency Application Service data and match outcome.

The investigator initially reviewed a small, randomly selected subset of 20 personal statements to identify characteristics and common themes. The investigator then analyzed each of the personal statements to quantify the frequency of each theme. All personal statements submitted to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine were analyzed in this manner. Dermatology match outcomes for each applicant were confirmed later using dermatology program websites.

Differences in the prevalence of common themes between matched and unmatched applicants were calculated. Analysis of variance tests were used to determine if the differences in prevalence were statistically significant (P≤.05).

Results

All 422 submitted personal statements were evaluated, with 308 personal statements from applicants who matched and 114 personal statements from unmatched applicants. The screening of the initial subset of 20 personal statements resulted in a total of 9 content themes. The prevalence of each theme among matched and unmatched applicants is shown in the Table.

The most common themes among both matched and unmatched groups were personal accomplishments or attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. The prevalence of certain themes varied between matched and unmatched groups. Dermatologic cases were discussed significantly more frequently in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (60.06% vs 46.49%, P=.013). Name-dropping was more prevalent in the unmatched group (37.72%) compared to the matched group (26.95%). This difference in prevalence reached statistical significance (P=.014). Religious influences also were discussed more frequently in the unmatched group (5.26%) vs the matched group (0.65%) with statistical significance (P=.002).

Comment

This study of 422 personal statements submitted to a major academic institution showed that certain themes were common in personal statements among both matched and unmatched applicants. These themes included personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. This finding is consistent with prior studies that show common themes in the personal statements of applicants across a wide variety of specialties, including dermatology, anesthesiology, pediatrics, general surgery, internal medicine, and radiology.5-10 Most commonly, applicants feel the need to justify why they chose their particular specialty, with Olazagasti et al5 (N=332) reporting that 70% of submitted dermatology personal statements explained why the applicant chose dermatology.

Certain themes, however, varied in prevalence between matched and unmatched groups in our study. Discussion of dermatologic cases was significantly more prevalent in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (P=.013), possibly because dermatology faculty enjoy hearing about cases and how the applicant responds and interacts with the cases. These data suggest that matched applicants focus more on characteristics specific to the clinical aspects of dermatology.

Conversely, name-dropping was significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.014). Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty. In 2016, applicants who matched into dermatology had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 249 with a mean number of 4.7 research experiences and 11.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications, which is higher than the average USMLE Step 1 score of 239 with a mean number of 3.8 research experiences and 8.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications for unmatched applicants.3 It is possible that residency selection committees may view name-dropping negatively if applicants choose to name-drop to strengthen their applications in comparison to more competitive candidates. Religious influences also were significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.002), but the overall frequency of religious influences was low (approximately 2% of all applicants).

The 422 personal statements examined in our study represent 83.1% of the total pool of applicants to postgraduate year 2 dermatology positions in 2012 (N=508).11 Our data differed somewhat from an analysis of same-year dermatology personal statements of 65% of the national applicant pool.5 Olazagasti et al5 found that themes of a family member in medicine (more in unmatched), a desire to contribute to decreasing literature gap (more in matched), and a desire to better understand dermatologic pathophysiology (more in matched) to be statistically significant (P≤.05 for all). Unfortunately, these themes were found in a small number of applicants, with each being reported in less than 7%.5 Our study included 23% more unmatched candidates and likely better estimated potential significant differences between matched and unmatched applicants.

In the Results section, Olazagasti et al5 reported that matched applicants emphasized the study of cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease significantly more frequently than unmatched applicants. However, the P value in their report did not support this statement (P=.054). In addition, their Conclusion section discussed matched candidates including themes of “why dermatology” and unmatched candidates including a “personal story” as differences between groups. Again, their results did not show any statistical significance to support these recommendations.5 When providing medical student mentorship in a field as competitive as dermatology, faculty must be careful in giving accurate advice that, if at all possible, is supported by objective data rather than personal preference or anecdotes.

Our study was limited in that only personal statements of applicants to a single program in a specific specialty were analyzed. Applicants may have submitted personalized versions of their personal statements to specific schools, which may have biased the themes present in this subset of personal statements. Given these limitations, we are unable to determine if these results are generalizable to all dermatology residency applicants. Further limitation is that the analysis of personal statements is in itself a subjective process.

This study included a larger number of personal statements representing a larger proportion of the total pool of applicants in 2012 than prior studies examining personal statements of dermatology residency applicants. In addition, this study examined the ultimate dermatology match outcome for each applicant during the 2012 application cycle. Future investigations could explore the role of other factors in the residency selection process such as USMLE Step scores, community service, research experiences, and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society status.

Conclusion

There are common themes in the personal statements of dermatology residency applicants, including personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. In addition, discussion of dermatologic cases was statistically more prevalent in applicants who ultimately matched, whereas name-dropping and religious influences were more prevalent in applicants who did not match. This information may be useful to effectively mentor medical students about the writing process for the personal statement. Further investigation is needed to explore these associations and the role of other aspects of the application in the residency selection process.

The personal statement is a narrative written by an applicant to residency programs to discuss his/her interests. It is one of the few places in the residency application process where applicants can express their personalities.1 Applicants believe the personal statement is an important opportunity to distinguish themselves from others, thus increasing their chances of successful matching, particularly in competitive specialties.1,2

Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty, with 614 medical students applying for 440 total dermatology positions in 2016.3 According to the results of the 2016 National Resident Matching program director survey, 82% (27/33) of dermatology program directors reported that the personal statement was a factor in selecting applicants to interview. Furthermore, dermatology program directors, on average, rated personal statements as more important than the Medical Student Performance Evaluation/Dean’s Letter, US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 scores, and class ranking/quartile.4

Prior studies have sought to evaluate the impact of personal statements on the application process. A 2014 study of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants found that the prevalence of certain themes differed according to match outcome.5 However, some of the conclusions drawn in this study were not supported by the reported results or were based on low numbers of participants. The purpose of our study was to examine personal statements from applications to a dermatology program at a major academic institution. This study identified common themes in personal statements, allowing for an analysis of their association with successful matching into dermatology.

Methods

All applications to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, North Carolina) during the 2012 application cycle (N=422) were eligible. All submitted personal statements (N=422) were included with all personal identifiers removed prior to analysis. The investigator (D.S.M.) was blinded to other Electronic Residency Application Service data and match outcome.

The investigator initially reviewed a small, randomly selected subset of 20 personal statements to identify characteristics and common themes. The investigator then analyzed each of the personal statements to quantify the frequency of each theme. All personal statements submitted to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine were analyzed in this manner. Dermatology match outcomes for each applicant were confirmed later using dermatology program websites.

Differences in the prevalence of common themes between matched and unmatched applicants were calculated. Analysis of variance tests were used to determine if the differences in prevalence were statistically significant (P≤.05).

Results

All 422 submitted personal statements were evaluated, with 308 personal statements from applicants who matched and 114 personal statements from unmatched applicants. The screening of the initial subset of 20 personal statements resulted in a total of 9 content themes. The prevalence of each theme among matched and unmatched applicants is shown in the Table.

The most common themes among both matched and unmatched groups were personal accomplishments or attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. The prevalence of certain themes varied between matched and unmatched groups. Dermatologic cases were discussed significantly more frequently in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (60.06% vs 46.49%, P=.013). Name-dropping was more prevalent in the unmatched group (37.72%) compared to the matched group (26.95%). This difference in prevalence reached statistical significance (P=.014). Religious influences also were discussed more frequently in the unmatched group (5.26%) vs the matched group (0.65%) with statistical significance (P=.002).

Comment

This study of 422 personal statements submitted to a major academic institution showed that certain themes were common in personal statements among both matched and unmatched applicants. These themes included personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. This finding is consistent with prior studies that show common themes in the personal statements of applicants across a wide variety of specialties, including dermatology, anesthesiology, pediatrics, general surgery, internal medicine, and radiology.5-10 Most commonly, applicants feel the need to justify why they chose their particular specialty, with Olazagasti et al5 (N=332) reporting that 70% of submitted dermatology personal statements explained why the applicant chose dermatology.

Certain themes, however, varied in prevalence between matched and unmatched groups in our study. Discussion of dermatologic cases was significantly more prevalent in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (P=.013), possibly because dermatology faculty enjoy hearing about cases and how the applicant responds and interacts with the cases. These data suggest that matched applicants focus more on characteristics specific to the clinical aspects of dermatology.

Conversely, name-dropping was significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.014). Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty. In 2016, applicants who matched into dermatology had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 249 with a mean number of 4.7 research experiences and 11.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications, which is higher than the average USMLE Step 1 score of 239 with a mean number of 3.8 research experiences and 8.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications for unmatched applicants.3 It is possible that residency selection committees may view name-dropping negatively if applicants choose to name-drop to strengthen their applications in comparison to more competitive candidates. Religious influences also were significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.002), but the overall frequency of religious influences was low (approximately 2% of all applicants).

The 422 personal statements examined in our study represent 83.1% of the total pool of applicants to postgraduate year 2 dermatology positions in 2012 (N=508).11 Our data differed somewhat from an analysis of same-year dermatology personal statements of 65% of the national applicant pool.5 Olazagasti et al5 found that themes of a family member in medicine (more in unmatched), a desire to contribute to decreasing literature gap (more in matched), and a desire to better understand dermatologic pathophysiology (more in matched) to be statistically significant (P≤.05 for all). Unfortunately, these themes were found in a small number of applicants, with each being reported in less than 7%.5 Our study included 23% more unmatched candidates and likely better estimated potential significant differences between matched and unmatched applicants.

In the Results section, Olazagasti et al5 reported that matched applicants emphasized the study of cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease significantly more frequently than unmatched applicants. However, the P value in their report did not support this statement (P=.054). In addition, their Conclusion section discussed matched candidates including themes of “why dermatology” and unmatched candidates including a “personal story” as differences between groups. Again, their results did not show any statistical significance to support these recommendations.5 When providing medical student mentorship in a field as competitive as dermatology, faculty must be careful in giving accurate advice that, if at all possible, is supported by objective data rather than personal preference or anecdotes.

Our study was limited in that only personal statements of applicants to a single program in a specific specialty were analyzed. Applicants may have submitted personalized versions of their personal statements to specific schools, which may have biased the themes present in this subset of personal statements. Given these limitations, we are unable to determine if these results are generalizable to all dermatology residency applicants. Further limitation is that the analysis of personal statements is in itself a subjective process.

This study included a larger number of personal statements representing a larger proportion of the total pool of applicants in 2012 than prior studies examining personal statements of dermatology residency applicants. In addition, this study examined the ultimate dermatology match outcome for each applicant during the 2012 application cycle. Future investigations could explore the role of other factors in the residency selection process such as USMLE Step scores, community service, research experiences, and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society status.

Conclusion

There are common themes in the personal statements of dermatology residency applicants, including personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. In addition, discussion of dermatologic cases was statistically more prevalent in applicants who ultimately matched, whereas name-dropping and religious influences were more prevalent in applicants who did not match. This information may be useful to effectively mentor medical students about the writing process for the personal statement. Further investigation is needed to explore these associations and the role of other aspects of the application in the residency selection process.

- Arbelaez C, Ganguli I. The personal statement for residency application: review and guidance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:439-442.

- White BA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, et al. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340-343.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match for U.S. Allopathic Seniors: Characteristics of US Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2016 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; September 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; June 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Olazagasti J, Gorouhi F, Fazel N. A critical review of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:934874.

- Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, et al. Have personal statements become impersonal? an evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346-351.

- Nield LS, Nease EK, Mitra S, et al. Major themes in the personal statements of pediatric resident applicants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:671-672.

- Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, et al. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:573-581.

- Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, et al. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93-102.

- Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, et al. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1024-1028.

- Results and Data: 2012 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; April 2012. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata20121.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Arbelaez C, Ganguli I. The personal statement for residency application: review and guidance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:439-442.

- White BA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, et al. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340-343.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match for U.S. Allopathic Seniors: Characteristics of US Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2016 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; September 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; June 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Olazagasti J, Gorouhi F, Fazel N. A critical review of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:934874.

- Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, et al. Have personal statements become impersonal? an evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346-351.

- Nield LS, Nease EK, Mitra S, et al. Major themes in the personal statements of pediatric resident applicants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:671-672.

- Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, et al. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:573-581.

- Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, et al. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93-102.

- Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, et al. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1024-1028.

- Results and Data: 2012 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; April 2012. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata20121.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

Practice Points

- The most common themes discussed in applicant personal statements include personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology.

- Presentation of dermatologic cases was more prevalent in personal statements of matched applicants.

- Name-dropping was more common among unmatched applicants.

What’s Eating You? Millipede Burns

Clinical Presentation

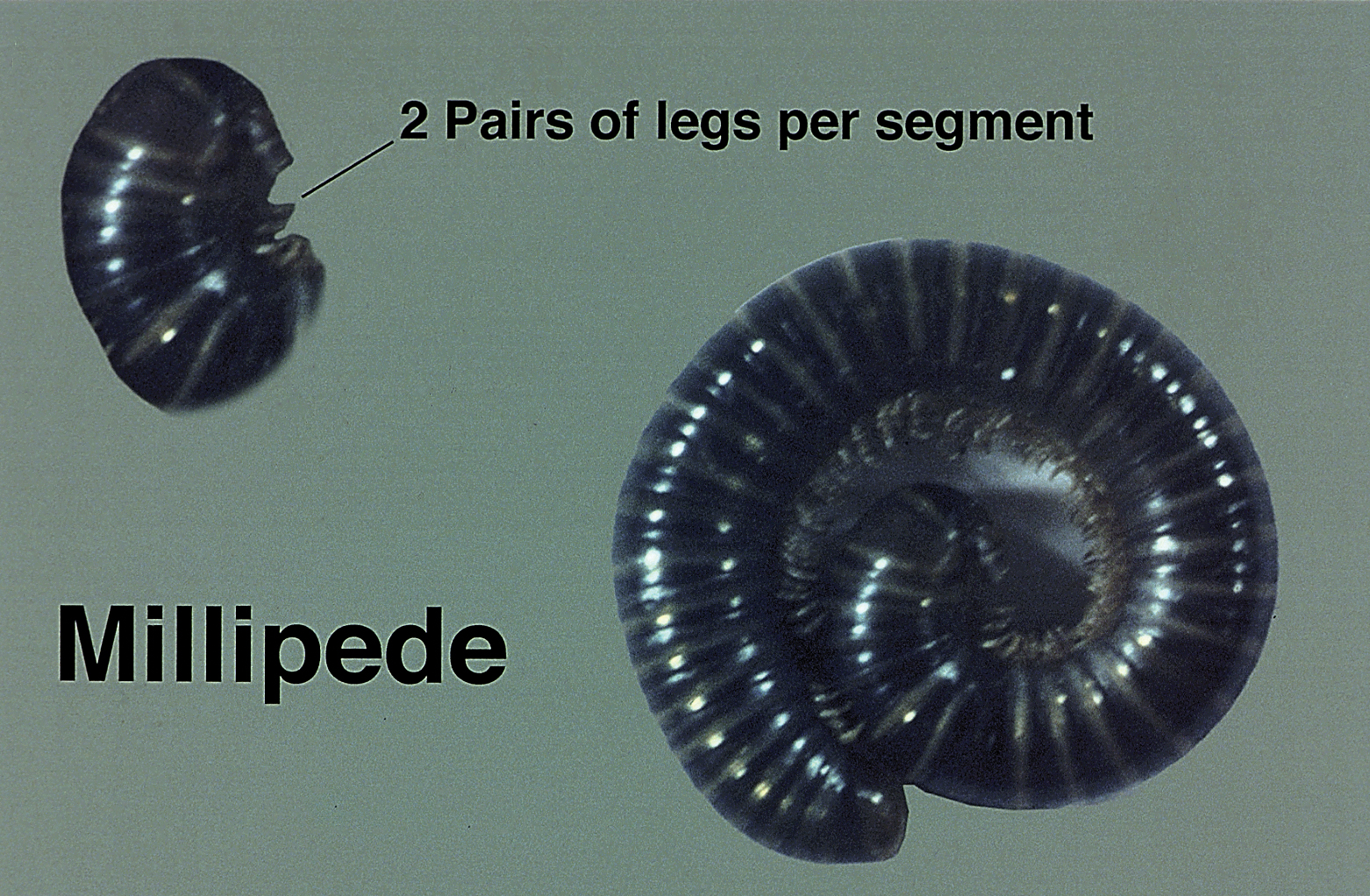

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

Clinical Presentation

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

Clinical Presentation

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

Practice Points

- The most common site of involvement of millipede burns is the foot, followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes. Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected.

- Millipede burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients; therefore, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.