User login

Atrophic Lesion on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

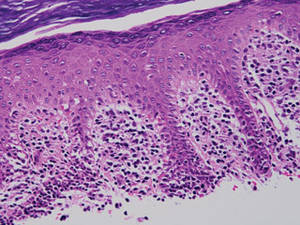

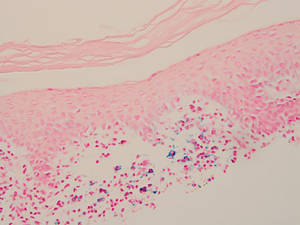

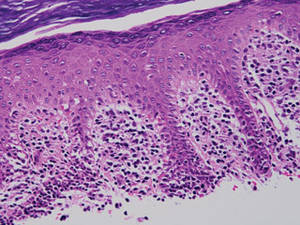

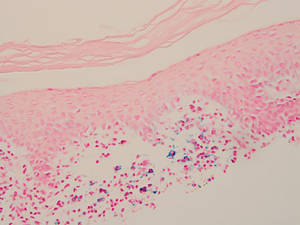

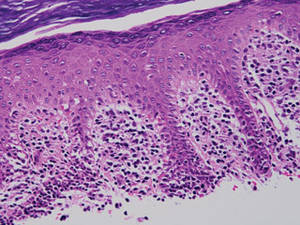

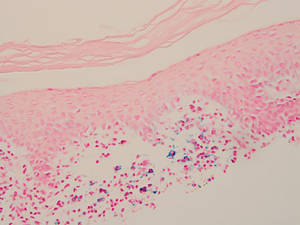

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

An 18-month-old child presented with a 4-cm, atrophic, flesh-colored plaque on the left lateral aspect of the abdomen with overlying wrinkling of the skin. There was no outpouching of the skin or pain associated with the lesion. No other skin abnormalities were noted. The child was born premature at 30 weeks’ gestation (birth weight, 1400 g). The postnatal course was complicated by respiratory distress syndrome requiring prolonged ventilator support. The infant was in the neonatal intensive care unit for 5 months. The atrophic lesion first developed at 5 months of life and remained stable. Although the lesion was not present at birth, the parents noted that it was preceded by an ecchymotic lesion without necrosis that was first noticed at 2 months of life while the patient was in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Dermatology Residency Applications: Correlation of Applicant Personal Statement Content With Match Result

The personal statement is a narrative written by an applicant to residency programs to discuss his/her interests. It is one of the few places in the residency application process where applicants can express their personalities.1 Applicants believe the personal statement is an important opportunity to distinguish themselves from others, thus increasing their chances of successful matching, particularly in competitive specialties.1,2

Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty, with 614 medical students applying for 440 total dermatology positions in 2016.3 According to the results of the 2016 National Resident Matching program director survey, 82% (27/33) of dermatology program directors reported that the personal statement was a factor in selecting applicants to interview. Furthermore, dermatology program directors, on average, rated personal statements as more important than the Medical Student Performance Evaluation/Dean’s Letter, US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 scores, and class ranking/quartile.4

Prior studies have sought to evaluate the impact of personal statements on the application process. A 2014 study of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants found that the prevalence of certain themes differed according to match outcome.5 However, some of the conclusions drawn in this study were not supported by the reported results or were based on low numbers of participants. The purpose of our study was to examine personal statements from applications to a dermatology program at a major academic institution. This study identified common themes in personal statements, allowing for an analysis of their association with successful matching into dermatology.

Methods

All applications to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, North Carolina) during the 2012 application cycle (N=422) were eligible. All submitted personal statements (N=422) were included with all personal identifiers removed prior to analysis. The investigator (D.S.M.) was blinded to other Electronic Residency Application Service data and match outcome.

The investigator initially reviewed a small, randomly selected subset of 20 personal statements to identify characteristics and common themes. The investigator then analyzed each of the personal statements to quantify the frequency of each theme. All personal statements submitted to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine were analyzed in this manner. Dermatology match outcomes for each applicant were confirmed later using dermatology program websites.

Differences in the prevalence of common themes between matched and unmatched applicants were calculated. Analysis of variance tests were used to determine if the differences in prevalence were statistically significant (P≤.05).

Results

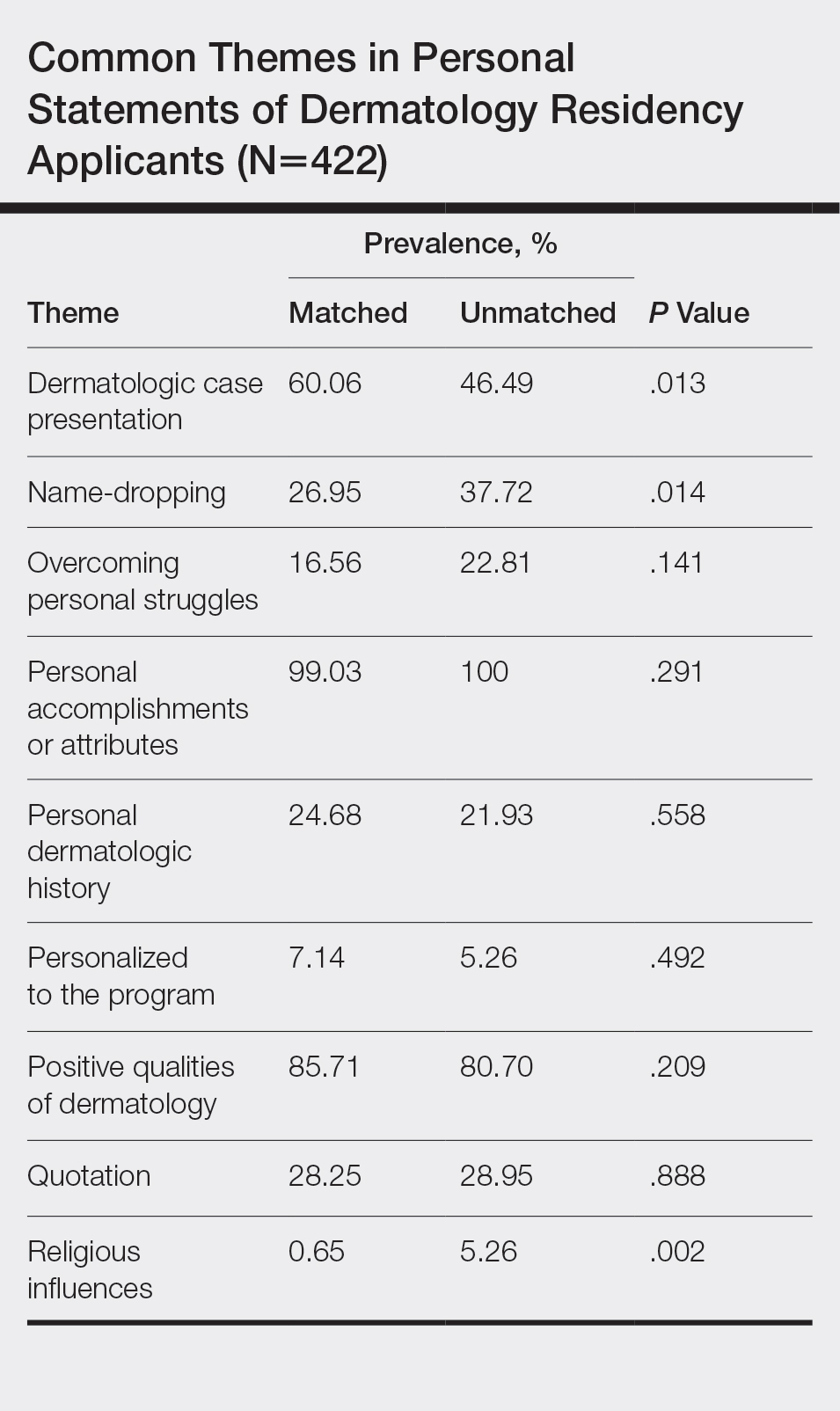

All 422 submitted personal statements were evaluated, with 308 personal statements from applicants who matched and 114 personal statements from unmatched applicants. The screening of the initial subset of 20 personal statements resulted in a total of 9 content themes. The prevalence of each theme among matched and unmatched applicants is shown in the Table.

The most common themes among both matched and unmatched groups were personal accomplishments or attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. The prevalence of certain themes varied between matched and unmatched groups. Dermatologic cases were discussed significantly more frequently in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (60.06% vs 46.49%, P=.013). Name-dropping was more prevalent in the unmatched group (37.72%) compared to the matched group (26.95%). This difference in prevalence reached statistical significance (P=.014). Religious influences also were discussed more frequently in the unmatched group (5.26%) vs the matched group (0.65%) with statistical significance (P=.002).

Comment

This study of 422 personal statements submitted to a major academic institution showed that certain themes were common in personal statements among both matched and unmatched applicants. These themes included personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. This finding is consistent with prior studies that show common themes in the personal statements of applicants across a wide variety of specialties, including dermatology, anesthesiology, pediatrics, general surgery, internal medicine, and radiology.5-10 Most commonly, applicants feel the need to justify why they chose their particular specialty, with Olazagasti et al5 (N=332) reporting that 70% of submitted dermatology personal statements explained why the applicant chose dermatology.

Certain themes, however, varied in prevalence between matched and unmatched groups in our study. Discussion of dermatologic cases was significantly more prevalent in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (P=.013), possibly because dermatology faculty enjoy hearing about cases and how the applicant responds and interacts with the cases. These data suggest that matched applicants focus more on characteristics specific to the clinical aspects of dermatology.

Conversely, name-dropping was significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.014). Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty. In 2016, applicants who matched into dermatology had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 249 with a mean number of 4.7 research experiences and 11.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications, which is higher than the average USMLE Step 1 score of 239 with a mean number of 3.8 research experiences and 8.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications for unmatched applicants.3 It is possible that residency selection committees may view name-dropping negatively if applicants choose to name-drop to strengthen their applications in comparison to more competitive candidates. Religious influences also were significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.002), but the overall frequency of religious influences was low (approximately 2% of all applicants).

The 422 personal statements examined in our study represent 83.1% of the total pool of applicants to postgraduate year 2 dermatology positions in 2012 (N=508).11 Our data differed somewhat from an analysis of same-year dermatology personal statements of 65% of the national applicant pool.5 Olazagasti et al5 found that themes of a family member in medicine (more in unmatched), a desire to contribute to decreasing literature gap (more in matched), and a desire to better understand dermatologic pathophysiology (more in matched) to be statistically significant (P≤.05 for all). Unfortunately, these themes were found in a small number of applicants, with each being reported in less than 7%.5 Our study included 23% more unmatched candidates and likely better estimated potential significant differences between matched and unmatched applicants.

In the Results section, Olazagasti et al5 reported that matched applicants emphasized the study of cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease significantly more frequently than unmatched applicants. However, the P value in their report did not support this statement (P=.054). In addition, their Conclusion section discussed matched candidates including themes of “why dermatology” and unmatched candidates including a “personal story” as differences between groups. Again, their results did not show any statistical significance to support these recommendations.5 When providing medical student mentorship in a field as competitive as dermatology, faculty must be careful in giving accurate advice that, if at all possible, is supported by objective data rather than personal preference or anecdotes.

Our study was limited in that only personal statements of applicants to a single program in a specific specialty were analyzed. Applicants may have submitted personalized versions of their personal statements to specific schools, which may have biased the themes present in this subset of personal statements. Given these limitations, we are unable to determine if these results are generalizable to all dermatology residency applicants. Further limitation is that the analysis of personal statements is in itself a subjective process.

This study included a larger number of personal statements representing a larger proportion of the total pool of applicants in 2012 than prior studies examining personal statements of dermatology residency applicants. In addition, this study examined the ultimate dermatology match outcome for each applicant during the 2012 application cycle. Future investigations could explore the role of other factors in the residency selection process such as USMLE Step scores, community service, research experiences, and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society status.

Conclusion

There are common themes in the personal statements of dermatology residency applicants, including personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. In addition, discussion of dermatologic cases was statistically more prevalent in applicants who ultimately matched, whereas name-dropping and religious influences were more prevalent in applicants who did not match. This information may be useful to effectively mentor medical students about the writing process for the personal statement. Further investigation is needed to explore these associations and the role of other aspects of the application in the residency selection process.

- Arbelaez C, Ganguli I. The personal statement for residency application: review and guidance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:439-442.

- White BA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, et al. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340-343.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match for U.S. Allopathic Seniors: Characteristics of US Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2016 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; September 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; June 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Olazagasti J, Gorouhi F, Fazel N. A critical review of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:934874.

- Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, et al. Have personal statements become impersonal? an evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346-351.

- Nield LS, Nease EK, Mitra S, et al. Major themes in the personal statements of pediatric resident applicants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:671-672.

- Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, et al. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:573-581.

- Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, et al. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93-102.

- Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, et al. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1024-1028.

- Results and Data: 2012 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; April 2012. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata20121.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

The personal statement is a narrative written by an applicant to residency programs to discuss his/her interests. It is one of the few places in the residency application process where applicants can express their personalities.1 Applicants believe the personal statement is an important opportunity to distinguish themselves from others, thus increasing their chances of successful matching, particularly in competitive specialties.1,2

Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty, with 614 medical students applying for 440 total dermatology positions in 2016.3 According to the results of the 2016 National Resident Matching program director survey, 82% (27/33) of dermatology program directors reported that the personal statement was a factor in selecting applicants to interview. Furthermore, dermatology program directors, on average, rated personal statements as more important than the Medical Student Performance Evaluation/Dean’s Letter, US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 scores, and class ranking/quartile.4

Prior studies have sought to evaluate the impact of personal statements on the application process. A 2014 study of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants found that the prevalence of certain themes differed according to match outcome.5 However, some of the conclusions drawn in this study were not supported by the reported results or were based on low numbers of participants. The purpose of our study was to examine personal statements from applications to a dermatology program at a major academic institution. This study identified common themes in personal statements, allowing for an analysis of their association with successful matching into dermatology.

Methods

All applications to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, North Carolina) during the 2012 application cycle (N=422) were eligible. All submitted personal statements (N=422) were included with all personal identifiers removed prior to analysis. The investigator (D.S.M.) was blinded to other Electronic Residency Application Service data and match outcome.

The investigator initially reviewed a small, randomly selected subset of 20 personal statements to identify characteristics and common themes. The investigator then analyzed each of the personal statements to quantify the frequency of each theme. All personal statements submitted to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine were analyzed in this manner. Dermatology match outcomes for each applicant were confirmed later using dermatology program websites.

Differences in the prevalence of common themes between matched and unmatched applicants were calculated. Analysis of variance tests were used to determine if the differences in prevalence were statistically significant (P≤.05).

Results

All 422 submitted personal statements were evaluated, with 308 personal statements from applicants who matched and 114 personal statements from unmatched applicants. The screening of the initial subset of 20 personal statements resulted in a total of 9 content themes. The prevalence of each theme among matched and unmatched applicants is shown in the Table.

The most common themes among both matched and unmatched groups were personal accomplishments or attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. The prevalence of certain themes varied between matched and unmatched groups. Dermatologic cases were discussed significantly more frequently in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (60.06% vs 46.49%, P=.013). Name-dropping was more prevalent in the unmatched group (37.72%) compared to the matched group (26.95%). This difference in prevalence reached statistical significance (P=.014). Religious influences also were discussed more frequently in the unmatched group (5.26%) vs the matched group (0.65%) with statistical significance (P=.002).

Comment

This study of 422 personal statements submitted to a major academic institution showed that certain themes were common in personal statements among both matched and unmatched applicants. These themes included personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. This finding is consistent with prior studies that show common themes in the personal statements of applicants across a wide variety of specialties, including dermatology, anesthesiology, pediatrics, general surgery, internal medicine, and radiology.5-10 Most commonly, applicants feel the need to justify why they chose their particular specialty, with Olazagasti et al5 (N=332) reporting that 70% of submitted dermatology personal statements explained why the applicant chose dermatology.

Certain themes, however, varied in prevalence between matched and unmatched groups in our study. Discussion of dermatologic cases was significantly more prevalent in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (P=.013), possibly because dermatology faculty enjoy hearing about cases and how the applicant responds and interacts with the cases. These data suggest that matched applicants focus more on characteristics specific to the clinical aspects of dermatology.

Conversely, name-dropping was significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.014). Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty. In 2016, applicants who matched into dermatology had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 249 with a mean number of 4.7 research experiences and 11.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications, which is higher than the average USMLE Step 1 score of 239 with a mean number of 3.8 research experiences and 8.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications for unmatched applicants.3 It is possible that residency selection committees may view name-dropping negatively if applicants choose to name-drop to strengthen their applications in comparison to more competitive candidates. Religious influences also were significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.002), but the overall frequency of religious influences was low (approximately 2% of all applicants).

The 422 personal statements examined in our study represent 83.1% of the total pool of applicants to postgraduate year 2 dermatology positions in 2012 (N=508).11 Our data differed somewhat from an analysis of same-year dermatology personal statements of 65% of the national applicant pool.5 Olazagasti et al5 found that themes of a family member in medicine (more in unmatched), a desire to contribute to decreasing literature gap (more in matched), and a desire to better understand dermatologic pathophysiology (more in matched) to be statistically significant (P≤.05 for all). Unfortunately, these themes were found in a small number of applicants, with each being reported in less than 7%.5 Our study included 23% more unmatched candidates and likely better estimated potential significant differences between matched and unmatched applicants.

In the Results section, Olazagasti et al5 reported that matched applicants emphasized the study of cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease significantly more frequently than unmatched applicants. However, the P value in their report did not support this statement (P=.054). In addition, their Conclusion section discussed matched candidates including themes of “why dermatology” and unmatched candidates including a “personal story” as differences between groups. Again, their results did not show any statistical significance to support these recommendations.5 When providing medical student mentorship in a field as competitive as dermatology, faculty must be careful in giving accurate advice that, if at all possible, is supported by objective data rather than personal preference or anecdotes.

Our study was limited in that only personal statements of applicants to a single program in a specific specialty were analyzed. Applicants may have submitted personalized versions of their personal statements to specific schools, which may have biased the themes present in this subset of personal statements. Given these limitations, we are unable to determine if these results are generalizable to all dermatology residency applicants. Further limitation is that the analysis of personal statements is in itself a subjective process.

This study included a larger number of personal statements representing a larger proportion of the total pool of applicants in 2012 than prior studies examining personal statements of dermatology residency applicants. In addition, this study examined the ultimate dermatology match outcome for each applicant during the 2012 application cycle. Future investigations could explore the role of other factors in the residency selection process such as USMLE Step scores, community service, research experiences, and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society status.

Conclusion

There are common themes in the personal statements of dermatology residency applicants, including personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. In addition, discussion of dermatologic cases was statistically more prevalent in applicants who ultimately matched, whereas name-dropping and religious influences were more prevalent in applicants who did not match. This information may be useful to effectively mentor medical students about the writing process for the personal statement. Further investigation is needed to explore these associations and the role of other aspects of the application in the residency selection process.

The personal statement is a narrative written by an applicant to residency programs to discuss his/her interests. It is one of the few places in the residency application process where applicants can express their personalities.1 Applicants believe the personal statement is an important opportunity to distinguish themselves from others, thus increasing their chances of successful matching, particularly in competitive specialties.1,2

Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty, with 614 medical students applying for 440 total dermatology positions in 2016.3 According to the results of the 2016 National Resident Matching program director survey, 82% (27/33) of dermatology program directors reported that the personal statement was a factor in selecting applicants to interview. Furthermore, dermatology program directors, on average, rated personal statements as more important than the Medical Student Performance Evaluation/Dean’s Letter, US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 scores, and class ranking/quartile.4

Prior studies have sought to evaluate the impact of personal statements on the application process. A 2014 study of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants found that the prevalence of certain themes differed according to match outcome.5 However, some of the conclusions drawn in this study were not supported by the reported results or were based on low numbers of participants. The purpose of our study was to examine personal statements from applications to a dermatology program at a major academic institution. This study identified common themes in personal statements, allowing for an analysis of their association with successful matching into dermatology.

Methods

All applications to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, North Carolina) during the 2012 application cycle (N=422) were eligible. All submitted personal statements (N=422) were included with all personal identifiers removed prior to analysis. The investigator (D.S.M.) was blinded to other Electronic Residency Application Service data and match outcome.

The investigator initially reviewed a small, randomly selected subset of 20 personal statements to identify characteristics and common themes. The investigator then analyzed each of the personal statements to quantify the frequency of each theme. All personal statements submitted to the dermatology residency program at UNC School of Medicine were analyzed in this manner. Dermatology match outcomes for each applicant were confirmed later using dermatology program websites.

Differences in the prevalence of common themes between matched and unmatched applicants were calculated. Analysis of variance tests were used to determine if the differences in prevalence were statistically significant (P≤.05).

Results

All 422 submitted personal statements were evaluated, with 308 personal statements from applicants who matched and 114 personal statements from unmatched applicants. The screening of the initial subset of 20 personal statements resulted in a total of 9 content themes. The prevalence of each theme among matched and unmatched applicants is shown in the Table.

The most common themes among both matched and unmatched groups were personal accomplishments or attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. The prevalence of certain themes varied between matched and unmatched groups. Dermatologic cases were discussed significantly more frequently in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (60.06% vs 46.49%, P=.013). Name-dropping was more prevalent in the unmatched group (37.72%) compared to the matched group (26.95%). This difference in prevalence reached statistical significance (P=.014). Religious influences also were discussed more frequently in the unmatched group (5.26%) vs the matched group (0.65%) with statistical significance (P=.002).

Comment

This study of 422 personal statements submitted to a major academic institution showed that certain themes were common in personal statements among both matched and unmatched applicants. These themes included personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. This finding is consistent with prior studies that show common themes in the personal statements of applicants across a wide variety of specialties, including dermatology, anesthesiology, pediatrics, general surgery, internal medicine, and radiology.5-10 Most commonly, applicants feel the need to justify why they chose their particular specialty, with Olazagasti et al5 (N=332) reporting that 70% of submitted dermatology personal statements explained why the applicant chose dermatology.

Certain themes, however, varied in prevalence between matched and unmatched groups in our study. Discussion of dermatologic cases was significantly more prevalent in the matched group compared to the unmatched group (P=.013), possibly because dermatology faculty enjoy hearing about cases and how the applicant responds and interacts with the cases. These data suggest that matched applicants focus more on characteristics specific to the clinical aspects of dermatology.

Conversely, name-dropping was significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.014). Dermatology is a highly competitive specialty. In 2016, applicants who matched into dermatology had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 249 with a mean number of 4.7 research experiences and 11.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications, which is higher than the average USMLE Step 1 score of 239 with a mean number of 3.8 research experiences and 8.7 abstracts, presentations, or publications for unmatched applicants.3 It is possible that residency selection committees may view name-dropping negatively if applicants choose to name-drop to strengthen their applications in comparison to more competitive candidates. Religious influences also were significantly more prevalent in the unmatched group (P=.002), but the overall frequency of religious influences was low (approximately 2% of all applicants).

The 422 personal statements examined in our study represent 83.1% of the total pool of applicants to postgraduate year 2 dermatology positions in 2012 (N=508).11 Our data differed somewhat from an analysis of same-year dermatology personal statements of 65% of the national applicant pool.5 Olazagasti et al5 found that themes of a family member in medicine (more in unmatched), a desire to contribute to decreasing literature gap (more in matched), and a desire to better understand dermatologic pathophysiology (more in matched) to be statistically significant (P≤.05 for all). Unfortunately, these themes were found in a small number of applicants, with each being reported in less than 7%.5 Our study included 23% more unmatched candidates and likely better estimated potential significant differences between matched and unmatched applicants.

In the Results section, Olazagasti et al5 reported that matched applicants emphasized the study of cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease significantly more frequently than unmatched applicants. However, the P value in their report did not support this statement (P=.054). In addition, their Conclusion section discussed matched candidates including themes of “why dermatology” and unmatched candidates including a “personal story” as differences between groups. Again, their results did not show any statistical significance to support these recommendations.5 When providing medical student mentorship in a field as competitive as dermatology, faculty must be careful in giving accurate advice that, if at all possible, is supported by objective data rather than personal preference or anecdotes.

Our study was limited in that only personal statements of applicants to a single program in a specific specialty were analyzed. Applicants may have submitted personalized versions of their personal statements to specific schools, which may have biased the themes present in this subset of personal statements. Given these limitations, we are unable to determine if these results are generalizable to all dermatology residency applicants. Further limitation is that the analysis of personal statements is in itself a subjective process.

This study included a larger number of personal statements representing a larger proportion of the total pool of applicants in 2012 than prior studies examining personal statements of dermatology residency applicants. In addition, this study examined the ultimate dermatology match outcome for each applicant during the 2012 application cycle. Future investigations could explore the role of other factors in the residency selection process such as USMLE Step scores, community service, research experiences, and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society status.

Conclusion

There are common themes in the personal statements of dermatology residency applicants, including personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology. In addition, discussion of dermatologic cases was statistically more prevalent in applicants who ultimately matched, whereas name-dropping and religious influences were more prevalent in applicants who did not match. This information may be useful to effectively mentor medical students about the writing process for the personal statement. Further investigation is needed to explore these associations and the role of other aspects of the application in the residency selection process.

- Arbelaez C, Ganguli I. The personal statement for residency application: review and guidance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:439-442.

- White BA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, et al. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340-343.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match for U.S. Allopathic Seniors: Characteristics of US Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2016 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; September 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; June 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Olazagasti J, Gorouhi F, Fazel N. A critical review of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:934874.

- Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, et al. Have personal statements become impersonal? an evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346-351.

- Nield LS, Nease EK, Mitra S, et al. Major themes in the personal statements of pediatric resident applicants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:671-672.

- Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, et al. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:573-581.

- Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, et al. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93-102.

- Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, et al. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1024-1028.

- Results and Data: 2012 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; April 2012. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata20121.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Arbelaez C, Ganguli I. The personal statement for residency application: review and guidance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:439-442.

- White BA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, et al. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340-343.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match for U.S. Allopathic Seniors: Characteristics of US Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2016 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; September 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; June 2016. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

- Olazagasti J, Gorouhi F, Fazel N. A critical review of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:934874.

- Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, et al. Have personal statements become impersonal? an evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346-351.

- Nield LS, Nease EK, Mitra S, et al. Major themes in the personal statements of pediatric resident applicants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:671-672.

- Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, et al. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:573-581.

- Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, et al. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93-102.

- Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, et al. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1024-1028.

- Results and Data: 2012 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; April 2012. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata20121.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2020.

Practice Points

- The most common themes discussed in applicant personal statements include personal accomplishments/attributes and positive qualities of dermatology.

- Presentation of dermatologic cases was more prevalent in personal statements of matched applicants.

- Name-dropping was more common among unmatched applicants.

Prolonged Pustular Eruption From Hydroxychloroquine: An Unusual Case of Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an uncommon cutaneous eruption characterized by acute, extensive, nonfollicular, sterile pustules accompanied by widespread erythema, fever, and leukocytosis. The clinical hallmark is superficial, sterile, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, which typically starts on the face, axilla, and groin and then progresses to most of the body. Approximately 90% of AGEP cases are due to drug hypersensitivity to a newly initiated medication, while the other 10% are thought to be viral in origin.1 Discontinuation of the offending agent may allow for complete resolution within 15 days. Agents commonly implicated in causing AGEP are antibiotics such as aminopenicillins, macrolides, and cephalosporins.2 Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) also has been reported to cause AGEP,3-7 with resolution shortly after discontinuation of the drug,4,6 close to the characteristic 15 days of AGEP due to alternate medications.We report an unusual case of HCQ-induced AGEP that lasted far beyond the typical 15 days. We also review other cases of HCQ-induced AGEP and possible mechanisms to explain our patient’s symptoms.

|

|

| Figure 1. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis extending to the chest and upper extremities (A) as well as the shoulders and back (B). |

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman who was previously diagnosed with rheumatoid factor seronegative, nonerosive rheumatoid arthritis, which was only moderately controlled with low-dose prednisone (5 mg once daily) after 2 months of treatment, was started on oral HCQ 200 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. Two weeks after starting HCQ treatment, she developed a pustular exanthem that gradually spread on the back over the next 24 to 48 hours. She described the eruption initially as pruritic, but she then developed painful stinging sensations as the eruption spread. She visited her primary care physician the next day and stopped the HCQ after 14 days following a discussion with the physician. Her prednisone dosage was increased to 50 mg daily for 5 days, but by the fifth day the lesions had spread to the face, full back, shoulders, and upper chest (Figure 1). Morphologically, she presented to the dermatology clinic with innumerable 1- to 2-mm pustules with confluent erythema on the back, extending to the forearms (Figure 2). She also had scattered erythematous macules and papules on the buttocks, legs, and plantar surfaces of the feet. A biopsy taken from the right forearm demonstrated subcorneal pustular dermatosis consistent with AGEP. Prednisone 50 mg once daily was continued. She was scheduled for a follow-up in 3 days but instead went to the emergency department 1 day later due to worsening of the eruption, fever, and malaise. On examination there were multiple discrete and confluent erythematous plaques on the face that extended to the lower extremities. Pustules and scales were noted on the back. New pustules had developed on the hands and feet with intense pruritus.

On admission, her vitals were stable with mild tachycardia. Aggressive intravenous hydration was administered. Her white blood cell count was elevated at 28.3×109/L (reference range, 4.5–10×109/L). She was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg once daily; topical steroid wet wraps with triamcinolone 0.1% were applied to the trunk, arms, legs, and abdomen twice daily; and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% was applied to the face and intertriginous areas 3 times daily. Over the next 2 days, eruptions continued to persist and the patient reported worsening of pain despite treatment. On day 3, intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg was switched to oral prednisone 80 mg once daily.

Over the ensuing 5 days, recurrent episodes of erythema on the back had spread to the extremities. After 1 week in the hospital, the diffuse erythema had improved and she had widespread desquamation. She was discharged and prescribed oral prednisone 80 mg once daily and topical therapy twice daily. The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 4 days after discharge with a mildly pruritic eruption on the trunk and proximal lower extremities but otherwise was doing well. She was instructed to taper the prednisone by 10 mg every 4 days.

At a follow-up 3 weeks later, she had persistent stinging and tingling sensations, widespread xerosis, and diffuse patchy erythema primarily on the back and proximal extremities, which flared over the last week. The patient reported waxing and waning of the erythema and pruritus since being discharged from the hospital. Despite the recent flare, which was her fourth flare of cutaneous eruption, she showed marked improvement since her initial examination and 40 days after discontinuation of HCQ. She was taking prednisone 40 mg once daily and was advised to continue tapering the dose by 2 mg every 6 to 8 days as tolerated. At 81 days after AGEP onset, the eruption had resolved and the patient was back to her baseline prednisone dosage of 5 mg once daily.

Comment

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is characterized by the sudden appearance of erythema and hundreds of sterile nonfollicular pustules, fever, and leukocytosis. Histologically, AGEP is composed of subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules, edema of the papillary dermis, and perivascular infiltrates of neutrophils and possible eosinophils. The pathogenesis of AGEP is thought to be due to the release of increased amounts of IL-8 by T cells, which attract and activate polymorphonuclear neutrophils.1 Psoriasiform changes are uncommon. Clinically, AGEP is similar to pustular psoriasis but has shown to be its own distinct entity. Unlike patients with pustular psoriasis, patients with AGEP lack a personal or family history of psoriasis or arthritis, have a shorter duration of pustules and fever, and have a history of new medication administration. Other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustulosis, IgA pemphigus, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.

In AGEP, the average duration of medication exposure prior to onset varies depending on the causative agent. Antibiotics consistently have been shown to trigger symptoms after 1 day, whereas other medications, including HCQ, averaged closer to 11 days. Hydroxychloroquine is widely used to treat rheumatic and dermatologic diseases and has previously been reported to be a less common cause of AGEP3; however, a EuroSCAR study found that patients treated with HCQ were at a greater risk for AGEP.2 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually follows a benign self-limiting course. Within days the eruption gradually evolves into superficial desquamation. Characteristically, removal of the offending agent typically leads to spontaneous resolution in less than 15 days. Resolution is generally without complications and, therefore, treatment is not always necessary. Death has been reported in up to 2% of cases.8 There are no known therapies that prevent the spread of lesions or further decline of the patient’s condition. Systemic corticosteroids often are used to treat AGEP with variable results.1,5

Unique to our patient were recurring exacerbations of the cutaneous lesions beyond the typical 15 days for complete resolution. Even up to 40 days after discontinuation of medication, our patient continued to experience cutaneous symptoms. Other reported cases have not described patients with symptoms flaring or continuing for this extended period of time. A review of 7 external AGEP cases caused by HCQ (identified through a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis or eruption with hydroxychloroquine or plaquenil) showed resolution within 8 days to 3 weeks (Table).3-6,8 One case report documented disease exacerbation on day 18 after tapering the methylprednisolone dose. This patient was then treated with cyclosporine and had a prompt recovery.5 One case of AGEP due to terbinafine reported continual symptoms for approximately 4 weeks after terbinafine discontinuation.9 Our patient’s continual symptoms beyond the typical 15 days may be due to the long half-life of HCQ, which is approximately 40 to 50 days. Systemic corticosteroids often are used to control severe eruptions in AGEP and were administered to our patient; however, their utility in shortening the duration or reducing the severity of the eruption has not been proven.

Conclusion

Hydroxychloroquine is a commonly used agent for dermatologic and rheumatologic conditions. The rare but severe acute adverse event of AGEP warrants caution in HCQ use. Correct diagnosis of AGEP with HCQ cessation generally is effective as therapy. Our patient demonstrated that not all cases of AGEP show rapid resolution of cutaneous symptoms after cessation of the drug. Hydroxychloroquine’s extended half-life of 40 to 50 days surpasses that of other medications known to cause AGEP and may explain our patient’s symptoms beyond the usual course.

1. Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts [published online June 14, 2010]. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:425-433.

2. Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)-results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR) [published online September 13, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:989-996.

3. Park JJ, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. A case of hydroxy-chloroquine induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by accidental oral provocation [published online February 28, 2010]. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:102-105.

4. Lateef A, Tan KB, Lau TC. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and toxic epidermal necrolysis induced by hydroxychloroquine [published online August 30, 2009]. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:1449-1452.

5. Di Lernia V, Grenzi L, Guareschi E, et al. Rapid clearing of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis after administration of ciclosporin [published online July 29, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e757-e759.

6. Paradisi A, Bugatti L, Sisto T, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by hydroxychloroquine: three cases and a review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2008;30:930-940.

7. Choi MJ, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of 36 Korean patients with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a case series and review of the literature [published online May 17, 2010]. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:163-169.

8. Martins A, Lopes LC, Paiva Lopes MJ, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by hydroxychloroquine. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:317-318.

9. Lombardo M, Cerati M, Pazzaglia A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:158-159.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an uncommon cutaneous eruption characterized by acute, extensive, nonfollicular, sterile pustules accompanied by widespread erythema, fever, and leukocytosis. The clinical hallmark is superficial, sterile, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, which typically starts on the face, axilla, and groin and then progresses to most of the body. Approximately 90% of AGEP cases are due to drug hypersensitivity to a newly initiated medication, while the other 10% are thought to be viral in origin.1 Discontinuation of the offending agent may allow for complete resolution within 15 days. Agents commonly implicated in causing AGEP are antibiotics such as aminopenicillins, macrolides, and cephalosporins.2 Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) also has been reported to cause AGEP,3-7 with resolution shortly after discontinuation of the drug,4,6 close to the characteristic 15 days of AGEP due to alternate medications.We report an unusual case of HCQ-induced AGEP that lasted far beyond the typical 15 days. We also review other cases of HCQ-induced AGEP and possible mechanisms to explain our patient’s symptoms.

|

|

| Figure 1. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis extending to the chest and upper extremities (A) as well as the shoulders and back (B). |

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman who was previously diagnosed with rheumatoid factor seronegative, nonerosive rheumatoid arthritis, which was only moderately controlled with low-dose prednisone (5 mg once daily) after 2 months of treatment, was started on oral HCQ 200 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. Two weeks after starting HCQ treatment, she developed a pustular exanthem that gradually spread on the back over the next 24 to 48 hours. She described the eruption initially as pruritic, but she then developed painful stinging sensations as the eruption spread. She visited her primary care physician the next day and stopped the HCQ after 14 days following a discussion with the physician. Her prednisone dosage was increased to 50 mg daily for 5 days, but by the fifth day the lesions had spread to the face, full back, shoulders, and upper chest (Figure 1). Morphologically, she presented to the dermatology clinic with innumerable 1- to 2-mm pustules with confluent erythema on the back, extending to the forearms (Figure 2). She also had scattered erythematous macules and papules on the buttocks, legs, and plantar surfaces of the feet. A biopsy taken from the right forearm demonstrated subcorneal pustular dermatosis consistent with AGEP. Prednisone 50 mg once daily was continued. She was scheduled for a follow-up in 3 days but instead went to the emergency department 1 day later due to worsening of the eruption, fever, and malaise. On examination there were multiple discrete and confluent erythematous plaques on the face that extended to the lower extremities. Pustules and scales were noted on the back. New pustules had developed on the hands and feet with intense pruritus.

On admission, her vitals were stable with mild tachycardia. Aggressive intravenous hydration was administered. Her white blood cell count was elevated at 28.3×109/L (reference range, 4.5–10×109/L). She was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg once daily; topical steroid wet wraps with triamcinolone 0.1% were applied to the trunk, arms, legs, and abdomen twice daily; and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% was applied to the face and intertriginous areas 3 times daily. Over the next 2 days, eruptions continued to persist and the patient reported worsening of pain despite treatment. On day 3, intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg was switched to oral prednisone 80 mg once daily.

Over the ensuing 5 days, recurrent episodes of erythema on the back had spread to the extremities. After 1 week in the hospital, the diffuse erythema had improved and she had widespread desquamation. She was discharged and prescribed oral prednisone 80 mg once daily and topical therapy twice daily. The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 4 days after discharge with a mildly pruritic eruption on the trunk and proximal lower extremities but otherwise was doing well. She was instructed to taper the prednisone by 10 mg every 4 days.

At a follow-up 3 weeks later, she had persistent stinging and tingling sensations, widespread xerosis, and diffuse patchy erythema primarily on the back and proximal extremities, which flared over the last week. The patient reported waxing and waning of the erythema and pruritus since being discharged from the hospital. Despite the recent flare, which was her fourth flare of cutaneous eruption, she showed marked improvement since her initial examination and 40 days after discontinuation of HCQ. She was taking prednisone 40 mg once daily and was advised to continue tapering the dose by 2 mg every 6 to 8 days as tolerated. At 81 days after AGEP onset, the eruption had resolved and the patient was back to her baseline prednisone dosage of 5 mg once daily.

Comment

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is characterized by the sudden appearance of erythema and hundreds of sterile nonfollicular pustules, fever, and leukocytosis. Histologically, AGEP is composed of subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules, edema of the papillary dermis, and perivascular infiltrates of neutrophils and possible eosinophils. The pathogenesis of AGEP is thought to be due to the release of increased amounts of IL-8 by T cells, which attract and activate polymorphonuclear neutrophils.1 Psoriasiform changes are uncommon. Clinically, AGEP is similar to pustular psoriasis but has shown to be its own distinct entity. Unlike patients with pustular psoriasis, patients with AGEP lack a personal or family history of psoriasis or arthritis, have a shorter duration of pustules and fever, and have a history of new medication administration. Other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustulosis, IgA pemphigus, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.

In AGEP, the average duration of medication exposure prior to onset varies depending on the causative agent. Antibiotics consistently have been shown to trigger symptoms after 1 day, whereas other medications, including HCQ, averaged closer to 11 days. Hydroxychloroquine is widely used to treat rheumatic and dermatologic diseases and has previously been reported to be a less common cause of AGEP3; however, a EuroSCAR study found that patients treated with HCQ were at a greater risk for AGEP.2 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually follows a benign self-limiting course. Within days the eruption gradually evolves into superficial desquamation. Characteristically, removal of the offending agent typically leads to spontaneous resolution in less than 15 days. Resolution is generally without complications and, therefore, treatment is not always necessary. Death has been reported in up to 2% of cases.8 There are no known therapies that prevent the spread of lesions or further decline of the patient’s condition. Systemic corticosteroids often are used to treat AGEP with variable results.1,5