User login

Scaly Annular and Concentric Plaques

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

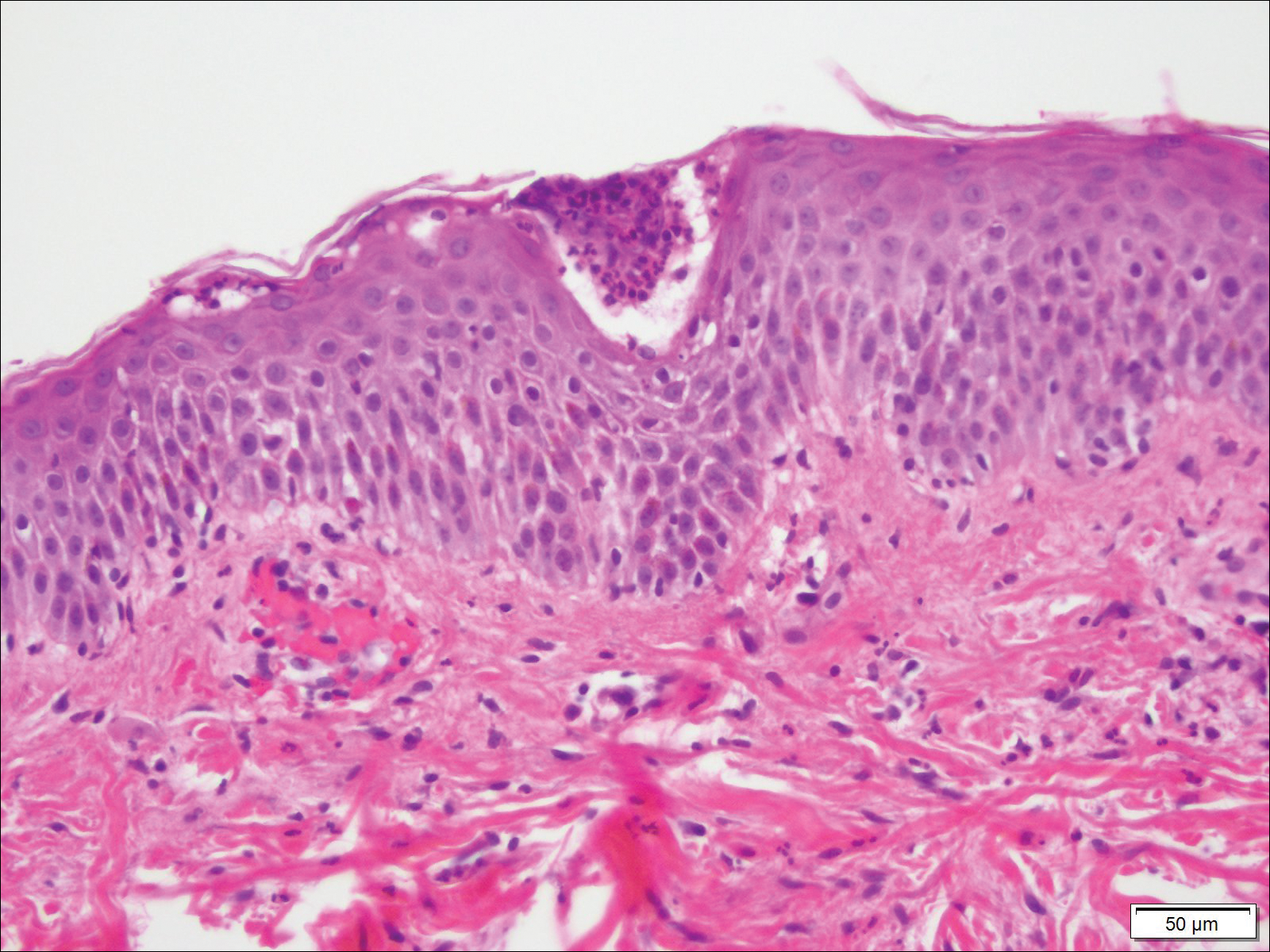

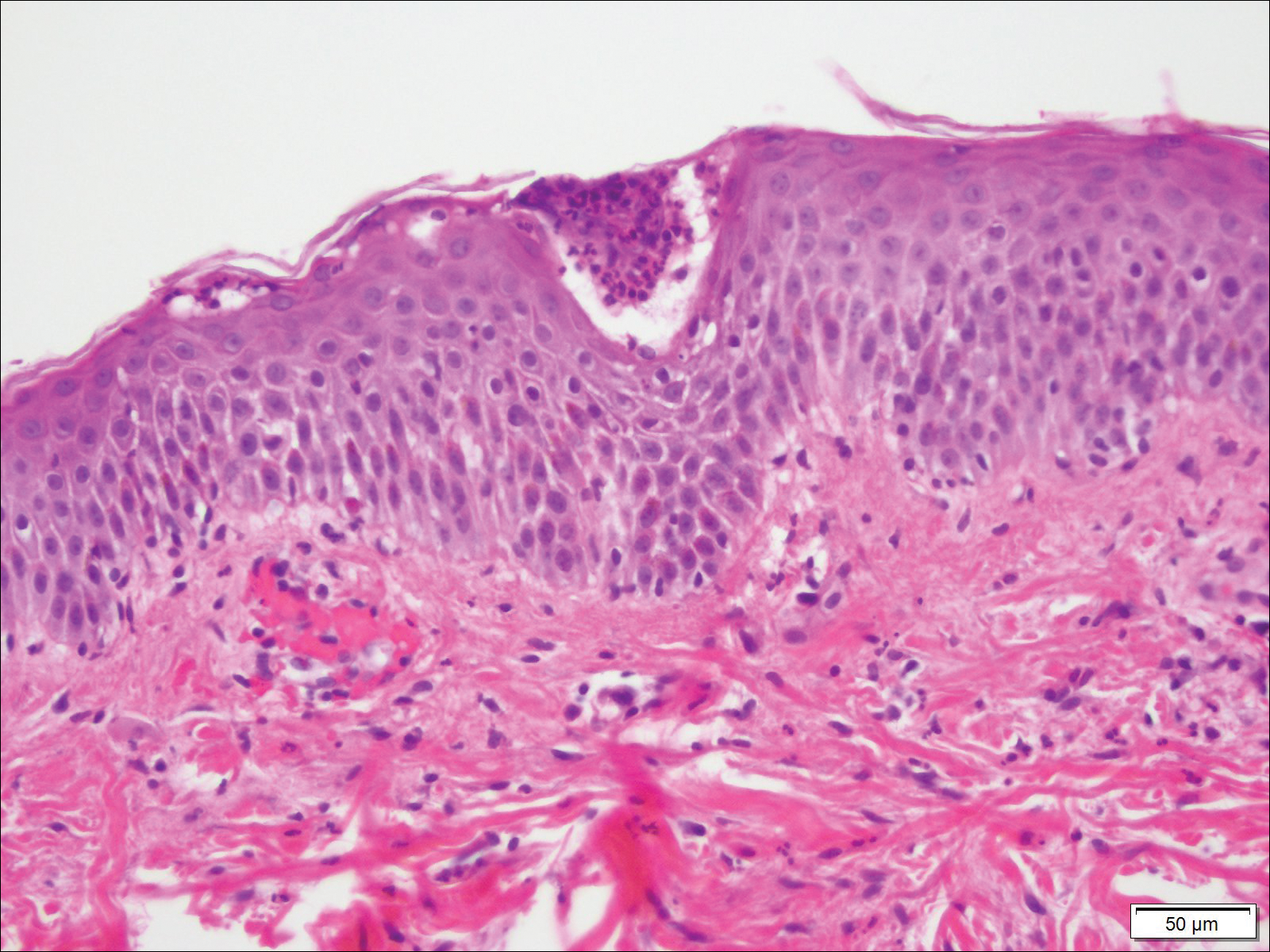

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

A healthy 23-year-old man presented for evaluation of an enlarging annular pruritic rash of 1.5 years' duration. Treatment with ciclopirox cream 0.77%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, fluticasone cream 0.05%, and halobetasol cream 0.05% prescribed by an outside physician provided only modest temporary improvement. The patient reported no history of travel outside of western New York, camping, tick bites, or medications. He denied any joint swelling or morning stiffness. Physical examination revealed multiple 4- to 6-cm pink, annular, scaly plaques with central clearing on the abdomen (top) and thighs. A few 1-cm pink scaly patches were present on the back (bottom), and few 2- to 3-mm pink scaly papules were noted on the extensor aspects of the elbows and forearms. A potassium hydroxide examination revealed no hyphal elements or yeast forms.

A Case of Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy With Positive Maternal-Fetal Outcomes

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP), also known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder of pregnancy wherein lesions typically appear in the third trimester and resolve after delivery; however, lesions may persist through the postpartum period. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy may be considered a fifth dermatosis of pregnancy, alongside the classic dermatoses of atopic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy.1

As PPP is a rare disease, its effects on maternal-fetal health outcomes and management remain to be elucidated. Though maternal mortality is rare in PPP, it is a unique dermatosis of pregnancy because it may be associated with severe systemic maternal symptoms.2 Fetal morbidity and mortality are less predictable in PPP, with reported cases of stillbirth, fetal anomalies, and neonatal death thought to be due largely to placental insufficiency, even with control of symptoms.1,3 Given the risk of serious harm to the fetus, reporting of cases and discussion of PPP management is critical.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old G2P1 woman at 32 weeks’ gestation presented to our emergency department with a 1-week history of a pruritic, burning rash that started on the thighs then spread diffusely. She denied any similar rash in her prior pregnancy. She was not currently taking any medications except for prenatal vitamins and denied any systemic symptoms. The patient’s obstetrician initiated treatment with methylprednisolone 50 mg once daily for the rash 3 days prior to the current presentation, which had not seemed to help. On physical examination, edematous pink plaques studded with 1- to 2-mm collarettes of scaling and sparse 1-mm pustules involving the arms, chest, abdomen, back, groin, buttocks, and legs were noted. The plaques on the back and inner thighs had a peripheral rim of desquamative scaling. There were pink macules on the palms, and superficial desquamation was noted on the lips. The oral mucosa was otherwise spared (Figure 1).

Biopsy specimens from the left arm revealed discrete subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis (Figure 2). The papillary dermis showed a sparse infiltrate of neutrophils with many marginated neutrophils within vessels. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for human IgG, IgA, IgM, complement component 3, and fibrinogen. Laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis of 21.5×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with neutrophilic predominance of 73.6% (reference range, 56%), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), and a mild hypocalcemia of 8.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The patient was started on methylprednisone 40 mg once daily with a plan to taper the dose by 8 mg every 5 days.

At 35 weeks’ gestation, the patient continued to report pruritus and burning in the areas where the rash had developed. The morphology of the rash had changed considerably, as she now had prominent, annular, pink plaques with central clearing, trailing scaling, and a border of subtle pustules on the legs. There also were rings of desquamative scaling on the palms. During follow-up at 37 weeks’ gestation, the back, chest, and abdomen were improved from the initial presentation, and annular pink plaques with central clearing were noted on the legs (Figure 3). Given the clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of PPP was made. It was recommended that she undergo increased fetal surveillance with close obstetric follow-up. Weekly office visits with obstetrics and twice-weekly Doppler ultrasounds and fetal nonstress tests were deemed appropriate management. The patient was scheduled for induction at 39 weeks’ gestation given the risk for potential harm to the fetus. She was maintained on low-dose methylprednisolone 4 mg once daily for the duration of the pregnancy. The patient continued to have gradual improvement of the rash at the low treatment dose.

Following induction at 39 weeks’ gestation, the patient vaginally delivered a healthy, 6-lb male neonate at an outside hospital. She reported that the burning sensation improved within hours of delivery, and systemic steroids were stopped after delivery. At a follow-up visit 3 weeks postpartum, considerable improvement of the rash was noted with no evidence of pustules. Fading pink patches with a superficial scaling were noted on the back, chest, abdomen, arms, legs (Figure 4), and fingertips. The patient was counseled that PPP could recur in subsequent pregnancies and that she should be aware of the potential risks to the fetus.

Comment

In our patient, the diagnosis of PPP was supported by the presence of erythematous, coalescent plaques with small pustules at the margins and central erosions as well as the histologic findings of subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis and a sparse neutrophilic infiltrate into the dermis.

The typical presentation of PPP is characterized by lesions that initially develop in skin folds with centrifugal spread.3 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet typically are spared with occasional involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae. Biopsy findings typically include spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Typical laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated ESR and leukocytosis.1

Diagnosis of PPP is critical given the potential for associated fetal morbidity and mortality.4 Anticipatory guidance for the patient also is necessary, as PPP can recur with subsequent pregnancies or even use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Notably, a patient with recurrences of PPP with each of 9 pregnancies also experienced a recurrence when taking a combination estrogen/progesterone OCP, but not with an estrogen-only diethylstilbestrol OCP.5 Although the pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is thought to be related to the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, most notably due to elevated progesterone levels.2 The presence of progesterone in OCPs and recurrences associated with their use supports this altered hormonal state, contributing to the underlying pathophysiology of PPP.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy can occur in women without any personal or family history of psoriasis, and as such, it is unclear whether PPP is a separate entity or a hormonally induced variation of generalized pustular psoriasis. Recent evidence included reports of women with PPP who had a mutation in the IL-36 receptor antagonist, leading to a relative abundance of IL-36 inflammatory cytokines.6

The mainstay of treatment for PPP is oral corticosteroids. Cases of PPP that are unresponsive to systemic steroids have been documented, requiring treatment with cyclosporine.9 Antitumor necrosis factors also have been used safely during pregnancy.10 Narrowband UVB phototherapy also has been proposed as a treatment alternative for patients who do not respond to oral corticosteroids.11

Conclusion

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare dermatosis of pregnancy that, unlike most other common dermatoses of pregnancy, is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. Diagnosis and management of PPP are critical to ensure the best care and outcomes for the patient and fetus and for a successful delivery of a healthy neonate. Our patient with PPP presented with involvement of the body, palms, and oral mucosa in the absence of systemic symptoms. Close follow-up and comanagement with the patient’s obstetrician ensured safe outcomes for the patient and the neonate.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Kar S, Krishnan A, Shivkumar PV. Pregnancy and skin [published online August 28, 2012]. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:268-275.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Sugiura K, Oiso N, Iinuma S, et al. IL36RN mutations underlie impetigo herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2472-2474.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants [published online March 5, 2014]. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192.

- Li X, Chen M, Fu X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:132-138.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP), also known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder of pregnancy wherein lesions typically appear in the third trimester and resolve after delivery; however, lesions may persist through the postpartum period. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy may be considered a fifth dermatosis of pregnancy, alongside the classic dermatoses of atopic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy.1

As PPP is a rare disease, its effects on maternal-fetal health outcomes and management remain to be elucidated. Though maternal mortality is rare in PPP, it is a unique dermatosis of pregnancy because it may be associated with severe systemic maternal symptoms.2 Fetal morbidity and mortality are less predictable in PPP, with reported cases of stillbirth, fetal anomalies, and neonatal death thought to be due largely to placental insufficiency, even with control of symptoms.1,3 Given the risk of serious harm to the fetus, reporting of cases and discussion of PPP management is critical.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old G2P1 woman at 32 weeks’ gestation presented to our emergency department with a 1-week history of a pruritic, burning rash that started on the thighs then spread diffusely. She denied any similar rash in her prior pregnancy. She was not currently taking any medications except for prenatal vitamins and denied any systemic symptoms. The patient’s obstetrician initiated treatment with methylprednisolone 50 mg once daily for the rash 3 days prior to the current presentation, which had not seemed to help. On physical examination, edematous pink plaques studded with 1- to 2-mm collarettes of scaling and sparse 1-mm pustules involving the arms, chest, abdomen, back, groin, buttocks, and legs were noted. The plaques on the back and inner thighs had a peripheral rim of desquamative scaling. There were pink macules on the palms, and superficial desquamation was noted on the lips. The oral mucosa was otherwise spared (Figure 1).

Biopsy specimens from the left arm revealed discrete subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis (Figure 2). The papillary dermis showed a sparse infiltrate of neutrophils with many marginated neutrophils within vessels. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for human IgG, IgA, IgM, complement component 3, and fibrinogen. Laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis of 21.5×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with neutrophilic predominance of 73.6% (reference range, 56%), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), and a mild hypocalcemia of 8.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The patient was started on methylprednisone 40 mg once daily with a plan to taper the dose by 8 mg every 5 days.

At 35 weeks’ gestation, the patient continued to report pruritus and burning in the areas where the rash had developed. The morphology of the rash had changed considerably, as she now had prominent, annular, pink plaques with central clearing, trailing scaling, and a border of subtle pustules on the legs. There also were rings of desquamative scaling on the palms. During follow-up at 37 weeks’ gestation, the back, chest, and abdomen were improved from the initial presentation, and annular pink plaques with central clearing were noted on the legs (Figure 3). Given the clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of PPP was made. It was recommended that she undergo increased fetal surveillance with close obstetric follow-up. Weekly office visits with obstetrics and twice-weekly Doppler ultrasounds and fetal nonstress tests were deemed appropriate management. The patient was scheduled for induction at 39 weeks’ gestation given the risk for potential harm to the fetus. She was maintained on low-dose methylprednisolone 4 mg once daily for the duration of the pregnancy. The patient continued to have gradual improvement of the rash at the low treatment dose.

Following induction at 39 weeks’ gestation, the patient vaginally delivered a healthy, 6-lb male neonate at an outside hospital. She reported that the burning sensation improved within hours of delivery, and systemic steroids were stopped after delivery. At a follow-up visit 3 weeks postpartum, considerable improvement of the rash was noted with no evidence of pustules. Fading pink patches with a superficial scaling were noted on the back, chest, abdomen, arms, legs (Figure 4), and fingertips. The patient was counseled that PPP could recur in subsequent pregnancies and that she should be aware of the potential risks to the fetus.

Comment

In our patient, the diagnosis of PPP was supported by the presence of erythematous, coalescent plaques with small pustules at the margins and central erosions as well as the histologic findings of subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis and a sparse neutrophilic infiltrate into the dermis.

The typical presentation of PPP is characterized by lesions that initially develop in skin folds with centrifugal spread.3 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet typically are spared with occasional involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae. Biopsy findings typically include spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Typical laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated ESR and leukocytosis.1

Diagnosis of PPP is critical given the potential for associated fetal morbidity and mortality.4 Anticipatory guidance for the patient also is necessary, as PPP can recur with subsequent pregnancies or even use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Notably, a patient with recurrences of PPP with each of 9 pregnancies also experienced a recurrence when taking a combination estrogen/progesterone OCP, but not with an estrogen-only diethylstilbestrol OCP.5 Although the pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is thought to be related to the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, most notably due to elevated progesterone levels.2 The presence of progesterone in OCPs and recurrences associated with their use supports this altered hormonal state, contributing to the underlying pathophysiology of PPP.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy can occur in women without any personal or family history of psoriasis, and as such, it is unclear whether PPP is a separate entity or a hormonally induced variation of generalized pustular psoriasis. Recent evidence included reports of women with PPP who had a mutation in the IL-36 receptor antagonist, leading to a relative abundance of IL-36 inflammatory cytokines.6

The mainstay of treatment for PPP is oral corticosteroids. Cases of PPP that are unresponsive to systemic steroids have been documented, requiring treatment with cyclosporine.9 Antitumor necrosis factors also have been used safely during pregnancy.10 Narrowband UVB phototherapy also has been proposed as a treatment alternative for patients who do not respond to oral corticosteroids.11

Conclusion

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare dermatosis of pregnancy that, unlike most other common dermatoses of pregnancy, is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. Diagnosis and management of PPP are critical to ensure the best care and outcomes for the patient and fetus and for a successful delivery of a healthy neonate. Our patient with PPP presented with involvement of the body, palms, and oral mucosa in the absence of systemic symptoms. Close follow-up and comanagement with the patient’s obstetrician ensured safe outcomes for the patient and the neonate.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP), also known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder of pregnancy wherein lesions typically appear in the third trimester and resolve after delivery; however, lesions may persist through the postpartum period. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy may be considered a fifth dermatosis of pregnancy, alongside the classic dermatoses of atopic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy.1

As PPP is a rare disease, its effects on maternal-fetal health outcomes and management remain to be elucidated. Though maternal mortality is rare in PPP, it is a unique dermatosis of pregnancy because it may be associated with severe systemic maternal symptoms.2 Fetal morbidity and mortality are less predictable in PPP, with reported cases of stillbirth, fetal anomalies, and neonatal death thought to be due largely to placental insufficiency, even with control of symptoms.1,3 Given the risk of serious harm to the fetus, reporting of cases and discussion of PPP management is critical.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old G2P1 woman at 32 weeks’ gestation presented to our emergency department with a 1-week history of a pruritic, burning rash that started on the thighs then spread diffusely. She denied any similar rash in her prior pregnancy. She was not currently taking any medications except for prenatal vitamins and denied any systemic symptoms. The patient’s obstetrician initiated treatment with methylprednisolone 50 mg once daily for the rash 3 days prior to the current presentation, which had not seemed to help. On physical examination, edematous pink plaques studded with 1- to 2-mm collarettes of scaling and sparse 1-mm pustules involving the arms, chest, abdomen, back, groin, buttocks, and legs were noted. The plaques on the back and inner thighs had a peripheral rim of desquamative scaling. There were pink macules on the palms, and superficial desquamation was noted on the lips. The oral mucosa was otherwise spared (Figure 1).

Biopsy specimens from the left arm revealed discrete subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis (Figure 2). The papillary dermis showed a sparse infiltrate of neutrophils with many marginated neutrophils within vessels. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for human IgG, IgA, IgM, complement component 3, and fibrinogen. Laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis of 21.5×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with neutrophilic predominance of 73.6% (reference range, 56%), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), and a mild hypocalcemia of 8.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The patient was started on methylprednisone 40 mg once daily with a plan to taper the dose by 8 mg every 5 days.

At 35 weeks’ gestation, the patient continued to report pruritus and burning in the areas where the rash had developed. The morphology of the rash had changed considerably, as she now had prominent, annular, pink plaques with central clearing, trailing scaling, and a border of subtle pustules on the legs. There also were rings of desquamative scaling on the palms. During follow-up at 37 weeks’ gestation, the back, chest, and abdomen were improved from the initial presentation, and annular pink plaques with central clearing were noted on the legs (Figure 3). Given the clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of PPP was made. It was recommended that she undergo increased fetal surveillance with close obstetric follow-up. Weekly office visits with obstetrics and twice-weekly Doppler ultrasounds and fetal nonstress tests were deemed appropriate management. The patient was scheduled for induction at 39 weeks’ gestation given the risk for potential harm to the fetus. She was maintained on low-dose methylprednisolone 4 mg once daily for the duration of the pregnancy. The patient continued to have gradual improvement of the rash at the low treatment dose.

Following induction at 39 weeks’ gestation, the patient vaginally delivered a healthy, 6-lb male neonate at an outside hospital. She reported that the burning sensation improved within hours of delivery, and systemic steroids were stopped after delivery. At a follow-up visit 3 weeks postpartum, considerable improvement of the rash was noted with no evidence of pustules. Fading pink patches with a superficial scaling were noted on the back, chest, abdomen, arms, legs (Figure 4), and fingertips. The patient was counseled that PPP could recur in subsequent pregnancies and that she should be aware of the potential risks to the fetus.

Comment

In our patient, the diagnosis of PPP was supported by the presence of erythematous, coalescent plaques with small pustules at the margins and central erosions as well as the histologic findings of subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis and a sparse neutrophilic infiltrate into the dermis.

The typical presentation of PPP is characterized by lesions that initially develop in skin folds with centrifugal spread.3 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet typically are spared with occasional involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae. Biopsy findings typically include spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Typical laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated ESR and leukocytosis.1

Diagnosis of PPP is critical given the potential for associated fetal morbidity and mortality.4 Anticipatory guidance for the patient also is necessary, as PPP can recur with subsequent pregnancies or even use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Notably, a patient with recurrences of PPP with each of 9 pregnancies also experienced a recurrence when taking a combination estrogen/progesterone OCP, but not with an estrogen-only diethylstilbestrol OCP.5 Although the pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is thought to be related to the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, most notably due to elevated progesterone levels.2 The presence of progesterone in OCPs and recurrences associated with their use supports this altered hormonal state, contributing to the underlying pathophysiology of PPP.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy can occur in women without any personal or family history of psoriasis, and as such, it is unclear whether PPP is a separate entity or a hormonally induced variation of generalized pustular psoriasis. Recent evidence included reports of women with PPP who had a mutation in the IL-36 receptor antagonist, leading to a relative abundance of IL-36 inflammatory cytokines.6

The mainstay of treatment for PPP is oral corticosteroids. Cases of PPP that are unresponsive to systemic steroids have been documented, requiring treatment with cyclosporine.9 Antitumor necrosis factors also have been used safely during pregnancy.10 Narrowband UVB phototherapy also has been proposed as a treatment alternative for patients who do not respond to oral corticosteroids.11

Conclusion

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare dermatosis of pregnancy that, unlike most other common dermatoses of pregnancy, is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. Diagnosis and management of PPP are critical to ensure the best care and outcomes for the patient and fetus and for a successful delivery of a healthy neonate. Our patient with PPP presented with involvement of the body, palms, and oral mucosa in the absence of systemic symptoms. Close follow-up and comanagement with the patient’s obstetrician ensured safe outcomes for the patient and the neonate.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Kar S, Krishnan A, Shivkumar PV. Pregnancy and skin [published online August 28, 2012]. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:268-275.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Sugiura K, Oiso N, Iinuma S, et al. IL36RN mutations underlie impetigo herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2472-2474.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants [published online March 5, 2014]. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192.

- Li X, Chen M, Fu X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:132-138.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Kar S, Krishnan A, Shivkumar PV. Pregnancy and skin [published online August 28, 2012]. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:268-275.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Sugiura K, Oiso N, Iinuma S, et al. IL36RN mutations underlie impetigo herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2472-2474.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants [published online March 5, 2014]. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192.

- Li X, Chen M, Fu X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:132-138.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

Practice Points

- Given its association with maternal and fetal morbidity/mortality, it is important for physicians to have a high suspicion for pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP) in pregnant women with widespread cutaneous eruptions.

- Oral corticosteroids and close involvement of obstetric care is the mainstay of treatment for PPP.