User login

Rapidly Progressive Necrotizing Myositis Mimicking Pyoderma Gangrenosum

To the Editor:

Necrotizing myositis (NM) is an exceedingly rare necrotizing soft-tissue infection (NSTI) that is characterized by skeletal muscle involvement. β -Hemolytic streptococci, such as Streptococcus pyogenes , are the most common causative organisms. The overall prevalence and incidence of NM is unknown. A review of the literature by Adams et al 2 identified only 21 cases between 1900 and 1985.

Timely treatment of this infection leads to improved outcomes, but diagnosis can be challenging due to the ambiguous presentation of NM and lack of specific cutaneous changes.3 Clinical manifestations including bullae, blisters, vesicles, and petechiae become more prominent as infection progresses.4 If NM is suspected due to cutaneous manifestations, it is imperative that the underlying cause be identified; for example, NM must be distinguished from the overlapping presentation of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). Because NM has nearly 100% mortality without prompt surgical intervention, early identification is critical.5 Herein, we report a case of NM that illustrates the correlation of clinical, histological, and imaging findings required to diagnose this potentially fatal infection.

An 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, edema, and spreading redness of the right wrist over the last 5 weeks. He had a history of atopic dermatitis that was refractory to topical steroids and methotrexate; he was dependent on an oral steroid (prednisone 30 mg/d) for symptom control. The patient reported minor trauma to the area after performing home renovations. He received numerous rounds of oral antibiotics as an outpatient for presumed cellulitis and reported he was “getting better” but that the signs and symptoms of the condition grew worse after outpatient arthrocentesis. Dermatology was consulted to evaluate for a necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG.

At the current presentation, the patient was tachycardic and afebrile (temperature, 98.2 °F [36.8 °C]). Physical examination revealed large, exquisitely tender, ill-defined necrotic ulceration of the right wrist with purulent debris and diffuse edema (Figure 1). Sequential evaluation at 6-hour intervals revealed notably increasing purulence, edema, and tenderness. Interconnected sinus tracts that extended to the fascial plane were observed.

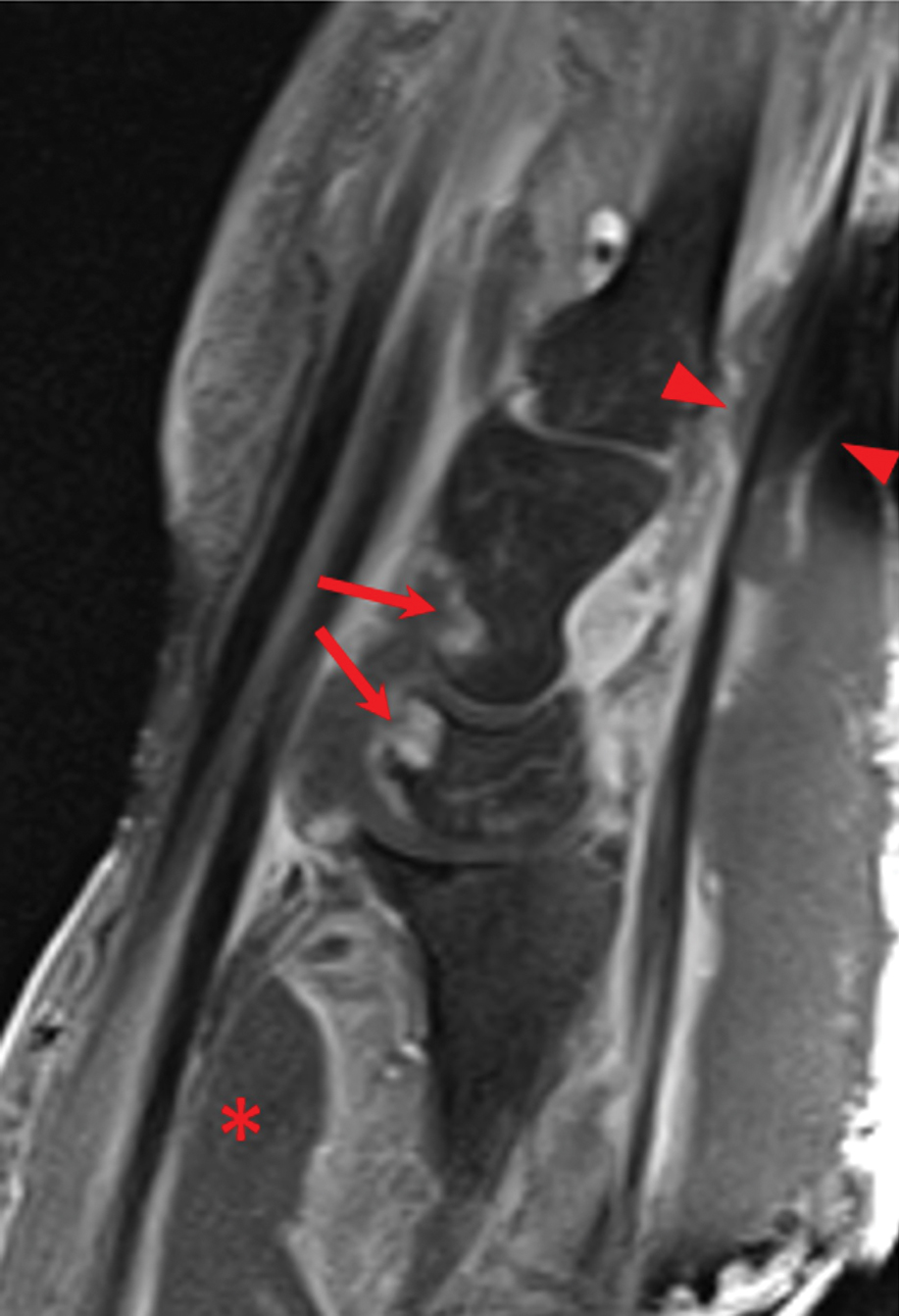

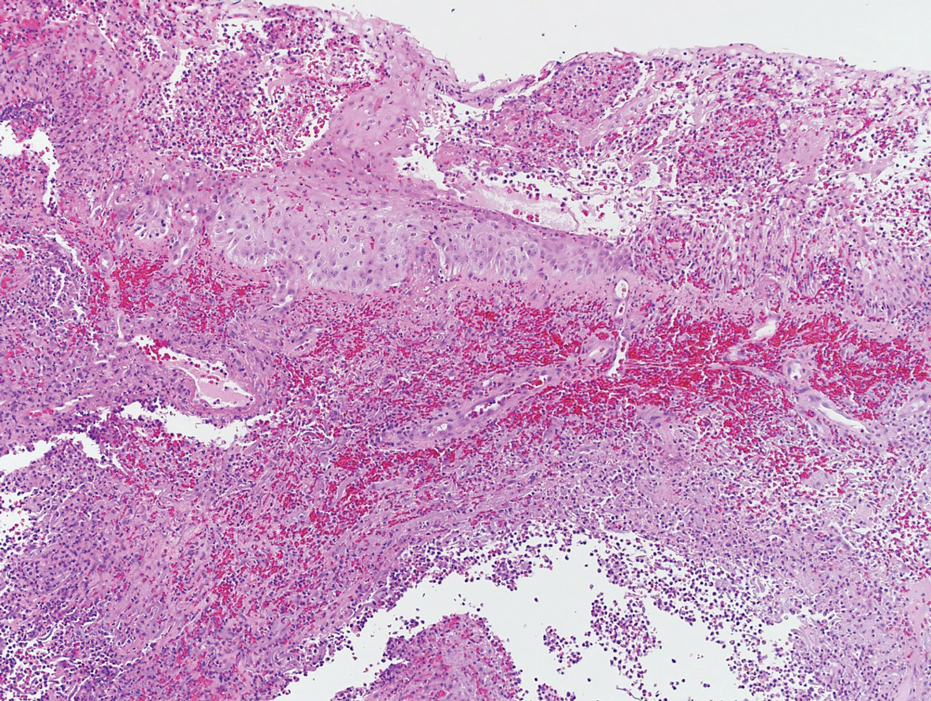

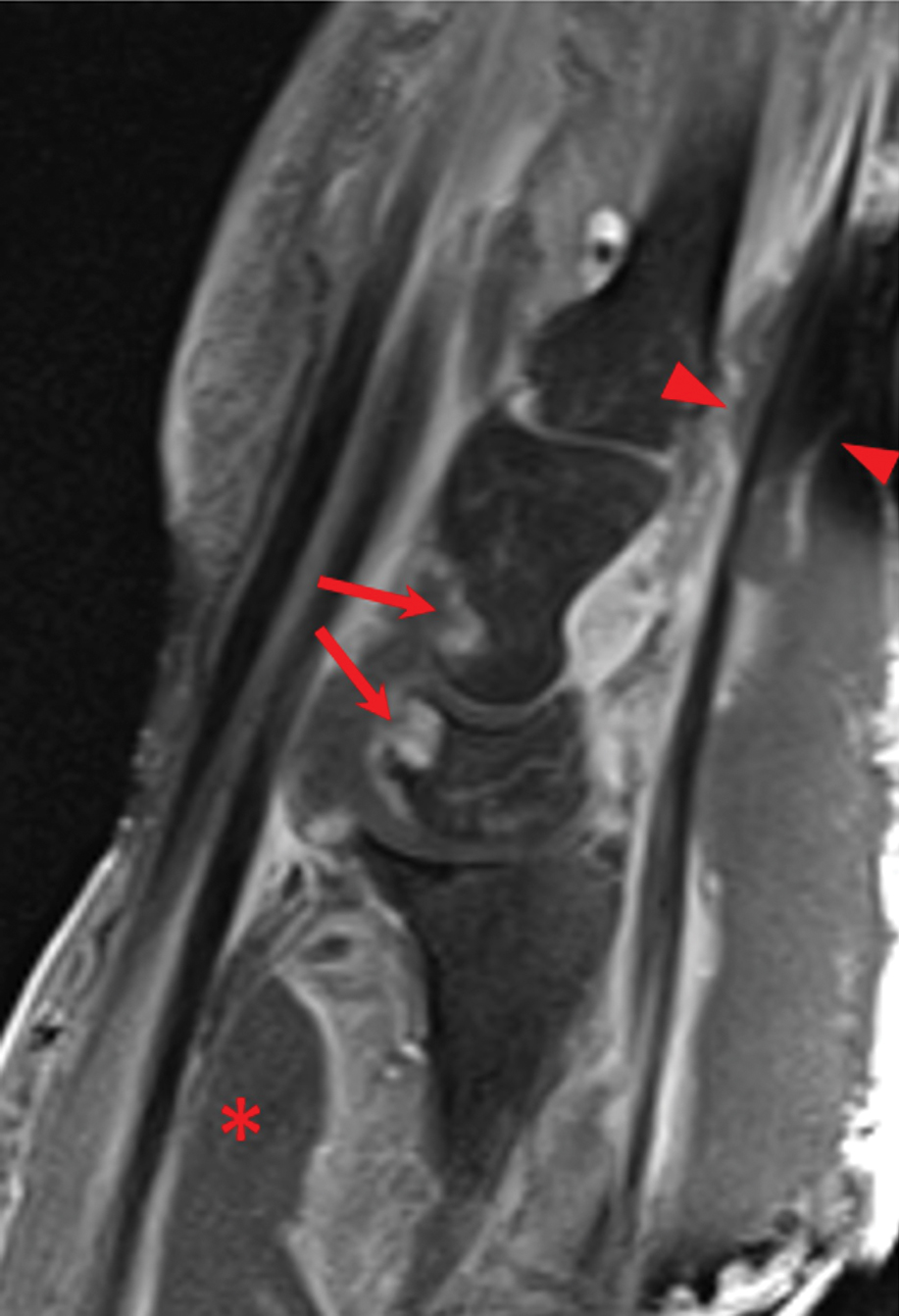

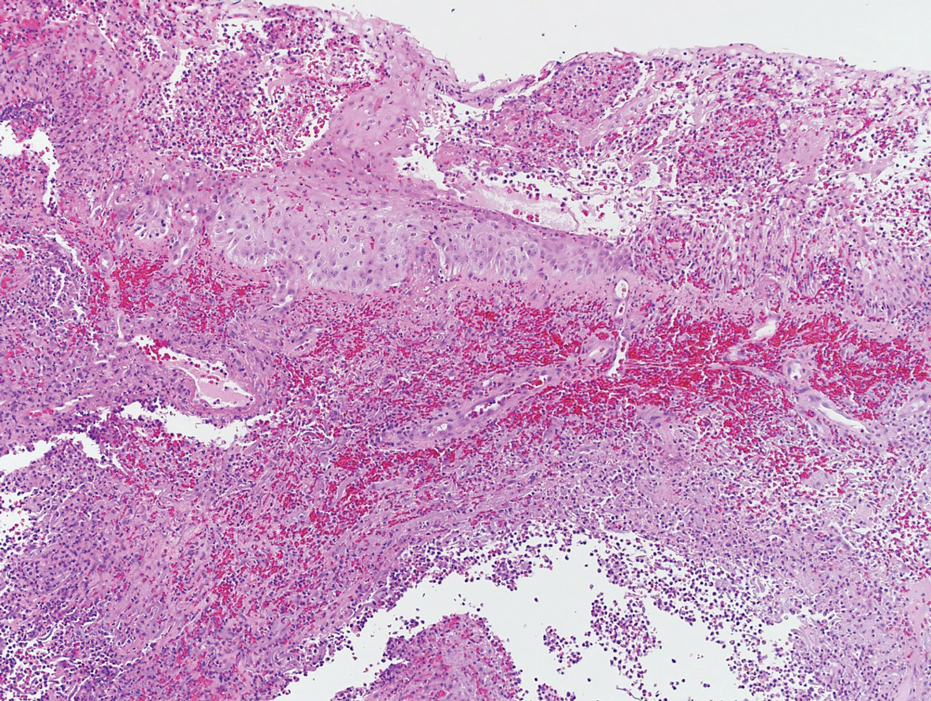

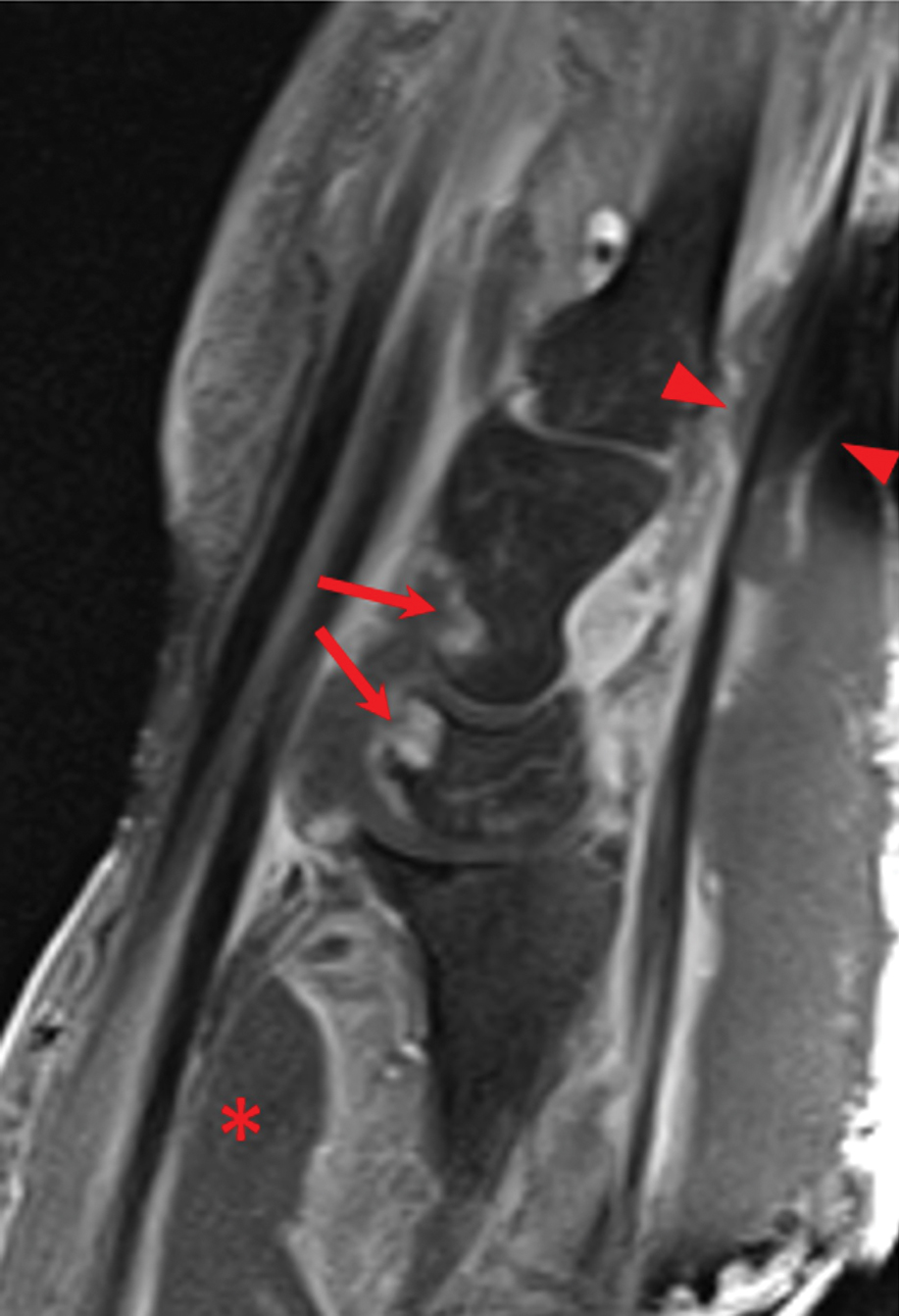

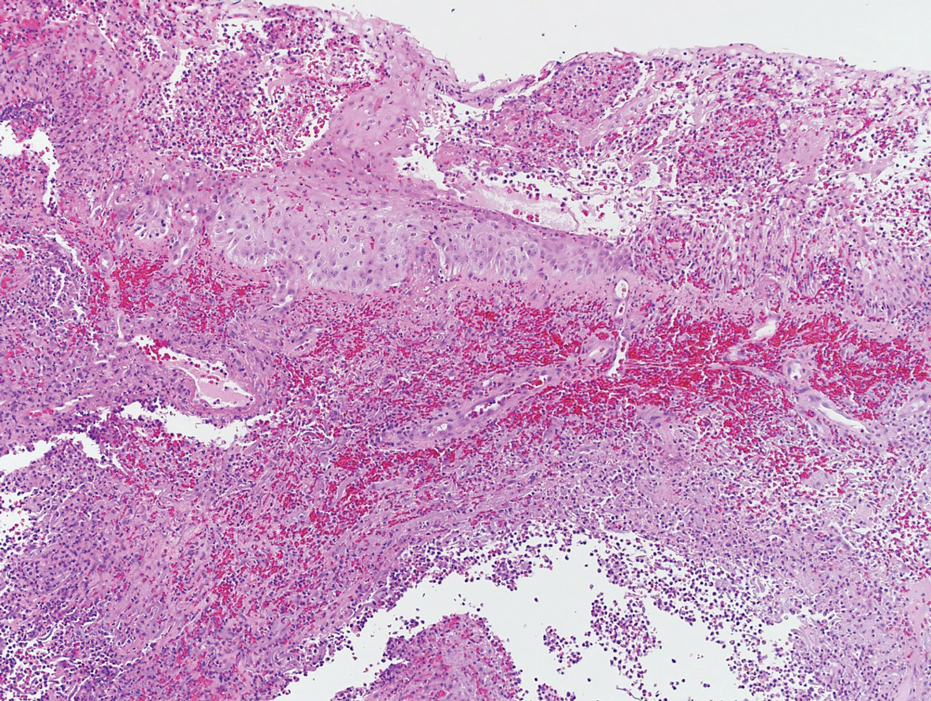

Laboratory workup was notable for a markedly elevated C-reactive protein level of 18.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0–0.8 mg/dL) and an elevated white blood cell count of 19.92×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L). Blood and tissue cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to biopsy demonstrated findings consistent with extensive subcutaneous and intramuscular areas of loculation and foci of gas (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intramuscular involvement. A punch biopsy revealed a necrotic epidermis filled with neutrophilic pustules and a dense dermal infiltrate of neutrophilic inflammation consistent with infection (Figure 3).

Emergency surgery was performed with debridement of necrotic tissue and muscle. Postoperatively, he became more clinically stable after being placed on cefazolin through a peripherally inserted central catheter. He underwent 4 additional washouts over the ensuing month, as well as tendon reconstructions, a radial forearm flap, and reverse radial forearm flap reconstruction of the forearm. At the time of publication, there has been no recurrence. The patient’s atopic dermatitis is well controlled on dupilumab and topical fluocinonide alone, with a recent IgA level of 1 g/L and a body surface area measurement of 2%. Dupilumab was started 3 months after surgery.

Necrotizing myositis is a rare, rapidly progressive infection involving muscle that can manifest as superficial cutaneous involvement. The clinical manifestation of NM is harder to recognize than other NSTIs such as necrotizing fasciitis, likely due to the initial prodromal phase of NM, which consists of nonspecific constitutional symptoms.3 Systemic findings such as tachycardia, fever, hypotension, and shock occur in only 10% to 40% of NM patients.4,5

In our patient, clues of NM included fulfillment of criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome at admission and a presumed source of infection; taken together, these findings should lead to a diagnosis of sepsis until otherwise proven. The patient also reported pain that was not proportional to the skin findings, which suggested an NSTI. His lack of constitutional symptoms may have been due to the effects of prednisone, which was changed to dupilumab during hospitalization.

The clinical and histological findings of NM are nonspecific. Clinical findings include skin discoloration with bullae, blisters, vesicles, or petechiae.4 Our case adds to the descriptive morphology by including marked edema with ulceration, progressive purulence, and interconnected sinuses tracking to the fascial plane. Histologic findings can include confluent necrosis extending from the epidermis to the underlying muscle with dense neutrophilic inflammation. Notably, these findings can mirror necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses in the absence of an infectious cause. Failure to recognize simple systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in NM patients due to slow treatment response or incorrect treatment can can lead to loss of a limb or death.

Workup reveals overlap with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses including PG, which is the prototypical neutrophilic dermatosis. Morphologically, PG presents as an ulcer with a purple and undermined border, often having developed from an initial papule, vesicle, or pustule. A neutrophilic infiltrate of the ulcer edge is the major criterion required to diagnose PG6; minor criteria include a positive pathergy test, history of inflammatory arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, and exclusion of infection.6 When compared directly to an NSTI such as NM, the most important variable that sets PG apart is the absence of bacterial growth on blood and tissue cultures.7

Imaging studies can aid in the clinical diagnosis of NM and help distinguish the disease from PG. Computed tomography and MRI may demonstrate hallmarks of extensive necrotizing infection, such as gas formation and consequent fascial swelling, thickening and edema of involved muscle, and subfascial fluid collection.3,4 Distinct from NM, imaging findings in PG are more subtle, suggesting cellulitic inflammation with edema.8 A defining radiographic feature of NM can be foci of gas within muscle or fascia, though absence of this finding does not exclude NM.1,4

In conclusion, NM is a rare intramuscular infection that can be difficult to diagnose due to its nonspecific presentation and lack of constitutional symptoms. Dermatologists should maintain a high level of suspicion for NM in the setting of rapidly progressive clinical findings; accurate diagnosis requires a multimodal approach with complete correlation of clinical, histological, and imaging findings. Computed tomography and MRI can heighten the approach, even when necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses and NM have similar clinical and histological appearances. Once a diagnosis of NM is established, prompt surgical and medical intervention improves the prognosis.

- Stevens DL, Baddour LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate. Updated October 7, 2022. Accessed February 13, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/necrotizing-soft-tissue-infections?search=Necrotizing%20soft%20tissue%20infections&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Adams EM, Gudmundsson S, Yocum DE, et al. Streptococcal myositis. Arch Intern Med . 1985;145:1020-1023.

- Khanna A, Gurusinghe D, Taylor D. Necrotizing myositis: highlighting the hidden depths—case series and review of the literature. ANZ J Surg . 2020;90:130-134. doi:10.1111/ans.15429

- Boinpally H, Howell RS, Ram B, et al. Necrotizing myositis: a rare necrotizing soft tissue infection involving muscle. Wounds . 2018;30:E116-E120.

- Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis . 2007;44:705-710. doi:10.1086/511638

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol . 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

- Sanchez IM, Lowenstein S, Johnson KA, et al. Clinical features of neutrophilic dermatosis variants resembling necrotizing fasciitis. JAMA Dermatol . 2019;155:79-84. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3890

- Demirdover C, Geyik A, Vayvada H. Necrotising fasciitis or pyoderma gangrenosum: a fatal dilemma. Int Wound J . 2019;16:1347-1353. doi:10.1111/iwj.13196

To the Editor:

Necrotizing myositis (NM) is an exceedingly rare necrotizing soft-tissue infection (NSTI) that is characterized by skeletal muscle involvement. β -Hemolytic streptococci, such as Streptococcus pyogenes , are the most common causative organisms. The overall prevalence and incidence of NM is unknown. A review of the literature by Adams et al 2 identified only 21 cases between 1900 and 1985.

Timely treatment of this infection leads to improved outcomes, but diagnosis can be challenging due to the ambiguous presentation of NM and lack of specific cutaneous changes.3 Clinical manifestations including bullae, blisters, vesicles, and petechiae become more prominent as infection progresses.4 If NM is suspected due to cutaneous manifestations, it is imperative that the underlying cause be identified; for example, NM must be distinguished from the overlapping presentation of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). Because NM has nearly 100% mortality without prompt surgical intervention, early identification is critical.5 Herein, we report a case of NM that illustrates the correlation of clinical, histological, and imaging findings required to diagnose this potentially fatal infection.

An 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, edema, and spreading redness of the right wrist over the last 5 weeks. He had a history of atopic dermatitis that was refractory to topical steroids and methotrexate; he was dependent on an oral steroid (prednisone 30 mg/d) for symptom control. The patient reported minor trauma to the area after performing home renovations. He received numerous rounds of oral antibiotics as an outpatient for presumed cellulitis and reported he was “getting better” but that the signs and symptoms of the condition grew worse after outpatient arthrocentesis. Dermatology was consulted to evaluate for a necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG.

At the current presentation, the patient was tachycardic and afebrile (temperature, 98.2 °F [36.8 °C]). Physical examination revealed large, exquisitely tender, ill-defined necrotic ulceration of the right wrist with purulent debris and diffuse edema (Figure 1). Sequential evaluation at 6-hour intervals revealed notably increasing purulence, edema, and tenderness. Interconnected sinus tracts that extended to the fascial plane were observed.

Laboratory workup was notable for a markedly elevated C-reactive protein level of 18.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0–0.8 mg/dL) and an elevated white blood cell count of 19.92×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L). Blood and tissue cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to biopsy demonstrated findings consistent with extensive subcutaneous and intramuscular areas of loculation and foci of gas (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intramuscular involvement. A punch biopsy revealed a necrotic epidermis filled with neutrophilic pustules and a dense dermal infiltrate of neutrophilic inflammation consistent with infection (Figure 3).

Emergency surgery was performed with debridement of necrotic tissue and muscle. Postoperatively, he became more clinically stable after being placed on cefazolin through a peripherally inserted central catheter. He underwent 4 additional washouts over the ensuing month, as well as tendon reconstructions, a radial forearm flap, and reverse radial forearm flap reconstruction of the forearm. At the time of publication, there has been no recurrence. The patient’s atopic dermatitis is well controlled on dupilumab and topical fluocinonide alone, with a recent IgA level of 1 g/L and a body surface area measurement of 2%. Dupilumab was started 3 months after surgery.

Necrotizing myositis is a rare, rapidly progressive infection involving muscle that can manifest as superficial cutaneous involvement. The clinical manifestation of NM is harder to recognize than other NSTIs such as necrotizing fasciitis, likely due to the initial prodromal phase of NM, which consists of nonspecific constitutional symptoms.3 Systemic findings such as tachycardia, fever, hypotension, and shock occur in only 10% to 40% of NM patients.4,5

In our patient, clues of NM included fulfillment of criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome at admission and a presumed source of infection; taken together, these findings should lead to a diagnosis of sepsis until otherwise proven. The patient also reported pain that was not proportional to the skin findings, which suggested an NSTI. His lack of constitutional symptoms may have been due to the effects of prednisone, which was changed to dupilumab during hospitalization.

The clinical and histological findings of NM are nonspecific. Clinical findings include skin discoloration with bullae, blisters, vesicles, or petechiae.4 Our case adds to the descriptive morphology by including marked edema with ulceration, progressive purulence, and interconnected sinuses tracking to the fascial plane. Histologic findings can include confluent necrosis extending from the epidermis to the underlying muscle with dense neutrophilic inflammation. Notably, these findings can mirror necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses in the absence of an infectious cause. Failure to recognize simple systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in NM patients due to slow treatment response or incorrect treatment can can lead to loss of a limb or death.

Workup reveals overlap with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses including PG, which is the prototypical neutrophilic dermatosis. Morphologically, PG presents as an ulcer with a purple and undermined border, often having developed from an initial papule, vesicle, or pustule. A neutrophilic infiltrate of the ulcer edge is the major criterion required to diagnose PG6; minor criteria include a positive pathergy test, history of inflammatory arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, and exclusion of infection.6 When compared directly to an NSTI such as NM, the most important variable that sets PG apart is the absence of bacterial growth on blood and tissue cultures.7

Imaging studies can aid in the clinical diagnosis of NM and help distinguish the disease from PG. Computed tomography and MRI may demonstrate hallmarks of extensive necrotizing infection, such as gas formation and consequent fascial swelling, thickening and edema of involved muscle, and subfascial fluid collection.3,4 Distinct from NM, imaging findings in PG are more subtle, suggesting cellulitic inflammation with edema.8 A defining radiographic feature of NM can be foci of gas within muscle or fascia, though absence of this finding does not exclude NM.1,4

In conclusion, NM is a rare intramuscular infection that can be difficult to diagnose due to its nonspecific presentation and lack of constitutional symptoms. Dermatologists should maintain a high level of suspicion for NM in the setting of rapidly progressive clinical findings; accurate diagnosis requires a multimodal approach with complete correlation of clinical, histological, and imaging findings. Computed tomography and MRI can heighten the approach, even when necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses and NM have similar clinical and histological appearances. Once a diagnosis of NM is established, prompt surgical and medical intervention improves the prognosis.

To the Editor:

Necrotizing myositis (NM) is an exceedingly rare necrotizing soft-tissue infection (NSTI) that is characterized by skeletal muscle involvement. β -Hemolytic streptococci, such as Streptococcus pyogenes , are the most common causative organisms. The overall prevalence and incidence of NM is unknown. A review of the literature by Adams et al 2 identified only 21 cases between 1900 and 1985.

Timely treatment of this infection leads to improved outcomes, but diagnosis can be challenging due to the ambiguous presentation of NM and lack of specific cutaneous changes.3 Clinical manifestations including bullae, blisters, vesicles, and petechiae become more prominent as infection progresses.4 If NM is suspected due to cutaneous manifestations, it is imperative that the underlying cause be identified; for example, NM must be distinguished from the overlapping presentation of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). Because NM has nearly 100% mortality without prompt surgical intervention, early identification is critical.5 Herein, we report a case of NM that illustrates the correlation of clinical, histological, and imaging findings required to diagnose this potentially fatal infection.

An 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, edema, and spreading redness of the right wrist over the last 5 weeks. He had a history of atopic dermatitis that was refractory to topical steroids and methotrexate; he was dependent on an oral steroid (prednisone 30 mg/d) for symptom control. The patient reported minor trauma to the area after performing home renovations. He received numerous rounds of oral antibiotics as an outpatient for presumed cellulitis and reported he was “getting better” but that the signs and symptoms of the condition grew worse after outpatient arthrocentesis. Dermatology was consulted to evaluate for a necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG.

At the current presentation, the patient was tachycardic and afebrile (temperature, 98.2 °F [36.8 °C]). Physical examination revealed large, exquisitely tender, ill-defined necrotic ulceration of the right wrist with purulent debris and diffuse edema (Figure 1). Sequential evaluation at 6-hour intervals revealed notably increasing purulence, edema, and tenderness. Interconnected sinus tracts that extended to the fascial plane were observed.

Laboratory workup was notable for a markedly elevated C-reactive protein level of 18.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0–0.8 mg/dL) and an elevated white blood cell count of 19.92×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L). Blood and tissue cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to biopsy demonstrated findings consistent with extensive subcutaneous and intramuscular areas of loculation and foci of gas (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intramuscular involvement. A punch biopsy revealed a necrotic epidermis filled with neutrophilic pustules and a dense dermal infiltrate of neutrophilic inflammation consistent with infection (Figure 3).

Emergency surgery was performed with debridement of necrotic tissue and muscle. Postoperatively, he became more clinically stable after being placed on cefazolin through a peripherally inserted central catheter. He underwent 4 additional washouts over the ensuing month, as well as tendon reconstructions, a radial forearm flap, and reverse radial forearm flap reconstruction of the forearm. At the time of publication, there has been no recurrence. The patient’s atopic dermatitis is well controlled on dupilumab and topical fluocinonide alone, with a recent IgA level of 1 g/L and a body surface area measurement of 2%. Dupilumab was started 3 months after surgery.

Necrotizing myositis is a rare, rapidly progressive infection involving muscle that can manifest as superficial cutaneous involvement. The clinical manifestation of NM is harder to recognize than other NSTIs such as necrotizing fasciitis, likely due to the initial prodromal phase of NM, which consists of nonspecific constitutional symptoms.3 Systemic findings such as tachycardia, fever, hypotension, and shock occur in only 10% to 40% of NM patients.4,5

In our patient, clues of NM included fulfillment of criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome at admission and a presumed source of infection; taken together, these findings should lead to a diagnosis of sepsis until otherwise proven. The patient also reported pain that was not proportional to the skin findings, which suggested an NSTI. His lack of constitutional symptoms may have been due to the effects of prednisone, which was changed to dupilumab during hospitalization.

The clinical and histological findings of NM are nonspecific. Clinical findings include skin discoloration with bullae, blisters, vesicles, or petechiae.4 Our case adds to the descriptive morphology by including marked edema with ulceration, progressive purulence, and interconnected sinuses tracking to the fascial plane. Histologic findings can include confluent necrosis extending from the epidermis to the underlying muscle with dense neutrophilic inflammation. Notably, these findings can mirror necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses in the absence of an infectious cause. Failure to recognize simple systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in NM patients due to slow treatment response or incorrect treatment can can lead to loss of a limb or death.

Workup reveals overlap with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses including PG, which is the prototypical neutrophilic dermatosis. Morphologically, PG presents as an ulcer with a purple and undermined border, often having developed from an initial papule, vesicle, or pustule. A neutrophilic infiltrate of the ulcer edge is the major criterion required to diagnose PG6; minor criteria include a positive pathergy test, history of inflammatory arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, and exclusion of infection.6 When compared directly to an NSTI such as NM, the most important variable that sets PG apart is the absence of bacterial growth on blood and tissue cultures.7

Imaging studies can aid in the clinical diagnosis of NM and help distinguish the disease from PG. Computed tomography and MRI may demonstrate hallmarks of extensive necrotizing infection, such as gas formation and consequent fascial swelling, thickening and edema of involved muscle, and subfascial fluid collection.3,4 Distinct from NM, imaging findings in PG are more subtle, suggesting cellulitic inflammation with edema.8 A defining radiographic feature of NM can be foci of gas within muscle or fascia, though absence of this finding does not exclude NM.1,4

In conclusion, NM is a rare intramuscular infection that can be difficult to diagnose due to its nonspecific presentation and lack of constitutional symptoms. Dermatologists should maintain a high level of suspicion for NM in the setting of rapidly progressive clinical findings; accurate diagnosis requires a multimodal approach with complete correlation of clinical, histological, and imaging findings. Computed tomography and MRI can heighten the approach, even when necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses and NM have similar clinical and histological appearances. Once a diagnosis of NM is established, prompt surgical and medical intervention improves the prognosis.

- Stevens DL, Baddour LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate. Updated October 7, 2022. Accessed February 13, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/necrotizing-soft-tissue-infections?search=Necrotizing%20soft%20tissue%20infections&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Adams EM, Gudmundsson S, Yocum DE, et al. Streptococcal myositis. Arch Intern Med . 1985;145:1020-1023.

- Khanna A, Gurusinghe D, Taylor D. Necrotizing myositis: highlighting the hidden depths—case series and review of the literature. ANZ J Surg . 2020;90:130-134. doi:10.1111/ans.15429

- Boinpally H, Howell RS, Ram B, et al. Necrotizing myositis: a rare necrotizing soft tissue infection involving muscle. Wounds . 2018;30:E116-E120.

- Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis . 2007;44:705-710. doi:10.1086/511638

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol . 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

- Sanchez IM, Lowenstein S, Johnson KA, et al. Clinical features of neutrophilic dermatosis variants resembling necrotizing fasciitis. JAMA Dermatol . 2019;155:79-84. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3890

- Demirdover C, Geyik A, Vayvada H. Necrotising fasciitis or pyoderma gangrenosum: a fatal dilemma. Int Wound J . 2019;16:1347-1353. doi:10.1111/iwj.13196

- Stevens DL, Baddour LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate. Updated October 7, 2022. Accessed February 13, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/necrotizing-soft-tissue-infections?search=Necrotizing%20soft%20tissue%20infections&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Adams EM, Gudmundsson S, Yocum DE, et al. Streptococcal myositis. Arch Intern Med . 1985;145:1020-1023.

- Khanna A, Gurusinghe D, Taylor D. Necrotizing myositis: highlighting the hidden depths—case series and review of the literature. ANZ J Surg . 2020;90:130-134. doi:10.1111/ans.15429

- Boinpally H, Howell RS, Ram B, et al. Necrotizing myositis: a rare necrotizing soft tissue infection involving muscle. Wounds . 2018;30:E116-E120.

- Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis . 2007;44:705-710. doi:10.1086/511638

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol . 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

- Sanchez IM, Lowenstein S, Johnson KA, et al. Clinical features of neutrophilic dermatosis variants resembling necrotizing fasciitis. JAMA Dermatol . 2019;155:79-84. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3890

- Demirdover C, Geyik A, Vayvada H. Necrotising fasciitis or pyoderma gangrenosum: a fatal dilemma. Int Wound J . 2019;16:1347-1353. doi:10.1111/iwj.13196

Practice Points

- The accurate diagnosis of necrotizing myositis (NM) requires a multimodal approach with complete clinical, histological, and radiographic correlation.

- Necrotizing myositis can manifest as violaceous erythematous plaques, bullae, blisters, or vesicles with petechiae, marked edema with ulceration, progressive purulence, and interconnected sinuses tracking to the fascial plane.

- The differential diagnosis of NM includes pyoderma gangrenosum.

Teledermatology During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned and Future Directions

Although teledermatology utilization in the United States traditionally has lagged behind other countries,1,2 the COVID-19 pandemic upended this trend by creating the need for a massive teledermatology experiment. Recently reported survey results from a large representative sample of US dermatologists (5000 participants) on perceptions of teledermatology during COVID-19 indicated that only 14.1% of participants used teledermatology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic vs 54.1% of dermatologists in Europe.2,3 Since the pandemic started, 97% of US dermatologists reported teledermatology use,3 demonstrating a huge shift in utilization. This trend is notable, as teledermatology has been shown to increase access to dermatology in underserved areas, reduce patient travel times, improve patient triage, and even reduce carbon footprints.1,4 Thus, to sustain the momentum, insights from the recent teledermatology experience during the pandemic should inform future development.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid shift in focus from store-and-forward teledermatology to live video–based models.1,2 Logistically, live video visits are challenging, require more time and resources, and often are diagnostically limited, with concerns regarding technology, connectivity, reimbursement, and appropriate use.3 Prior to COVID-19, formal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant teledermatology platforms often were costly to establish and maintain, largely relegating use to academic centers and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thus, many fewer private practice dermatologists had used teledermatology compared to academic dermatologists in the United States (11.4% vs 27.6%).3 Government regulations—a key barrier to the adoption of teledermatology in private practice before COVID-19—were greatly relaxed during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed restrictions on where patients could be seen, improved reimbursement for video visits, and allowed the use of platforms that are not Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. Many states also relaxed medical licensing rules.

Overall, the general outlook on telehealth seems positive. Reimbursement has been found to be a primary factor in dermatologists’ willingness to use teledermatology.3 Thus, sustainable use of teledermatology likely will depend on continued reimbursement parity for live video as well as store-and-forward consultations, which have several advantages but currently are de-incentivized by low reimbursement. The survey also found that 70% of respondents felt that teledermatology use will continue after COVID-19, while 58% intended to continue use—nearly 5-fold more than before the pandemic.3 We suspect the discrepancy between participants’ predictions regarding future use of teledermatology and their personal intent to use it highlights perceived barriers and limitations of the long-term success of teledermatology. Aside from reimbursement, connectivity and functionality were common concerns, emphasizing the need for innovative technological solutions.3 Moving forward, we anticipate that dermatologists will need to establish consistent workflows to establish consistent triage for the most appropriate visit—in-person visits vs teledermatology, which may include augmented, intelligence-enhanced solutions. Similar to prior clinician perspectives about which types of visits are conducive to teledermatology,2 most survey participants believed virtual visits were effective for acne, routine follow-ups, medication monitoring, and some inflammatory conditions.3

Importantly, we must be mindful of patients who may be left behind by the digital divide, such as those with lack of access to a smartphone or the internet, language barriers, or limited telehealth experience.5 Systems should be designed to provide these patients with technologic and health literacy aid or alternate modalities to access care. For example, structured methods could be introduced to provide training and instructions on how to access phone applications, computer-based programs, and more. Likewise, for those with hearing or vision deficits, it will be important to improve sound amplification and accessibility for headphones or hearing aid connectivity, as well as appropriate font size, button size, and application navigation. In remote areas, existing clinics may be used to help field specialty consultation teleconferences. Certainly, applications and platforms devised for teledermatology must be designed to serve diverse patient groups, with special consideration for the elderly, those who speak languages other than English, and those with disabilities that may make telehealth use more challenging.

Large-scale regulatory changes and reimbursement parity can have a substantial impact on future teledermatology use. Advocacy efforts continue to push for fair valuation of telemedicine, coverage of store-and-forward teledermatology codes, and coverage for all models of care. It is imperative for the dermatology community to continue discussions on implementation and methodology to best leverage this technology for the most patient benefit.

- Tensen E, van der Heijden JP, Jaspers MWM, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Moscarella E, Pasquali P, Cinotti E, et al. A survey on teledermatology use and doctors’ perception in times of COVID-19 [published online August 17, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E772-E773.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Bonsall A. Unleashing carbon emissions savings with regular teledermatology clinics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:574-575.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.

Although teledermatology utilization in the United States traditionally has lagged behind other countries,1,2 the COVID-19 pandemic upended this trend by creating the need for a massive teledermatology experiment. Recently reported survey results from a large representative sample of US dermatologists (5000 participants) on perceptions of teledermatology during COVID-19 indicated that only 14.1% of participants used teledermatology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic vs 54.1% of dermatologists in Europe.2,3 Since the pandemic started, 97% of US dermatologists reported teledermatology use,3 demonstrating a huge shift in utilization. This trend is notable, as teledermatology has been shown to increase access to dermatology in underserved areas, reduce patient travel times, improve patient triage, and even reduce carbon footprints.1,4 Thus, to sustain the momentum, insights from the recent teledermatology experience during the pandemic should inform future development.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid shift in focus from store-and-forward teledermatology to live video–based models.1,2 Logistically, live video visits are challenging, require more time and resources, and often are diagnostically limited, with concerns regarding technology, connectivity, reimbursement, and appropriate use.3 Prior to COVID-19, formal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant teledermatology platforms often were costly to establish and maintain, largely relegating use to academic centers and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thus, many fewer private practice dermatologists had used teledermatology compared to academic dermatologists in the United States (11.4% vs 27.6%).3 Government regulations—a key barrier to the adoption of teledermatology in private practice before COVID-19—were greatly relaxed during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed restrictions on where patients could be seen, improved reimbursement for video visits, and allowed the use of platforms that are not Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. Many states also relaxed medical licensing rules.

Overall, the general outlook on telehealth seems positive. Reimbursement has been found to be a primary factor in dermatologists’ willingness to use teledermatology.3 Thus, sustainable use of teledermatology likely will depend on continued reimbursement parity for live video as well as store-and-forward consultations, which have several advantages but currently are de-incentivized by low reimbursement. The survey also found that 70% of respondents felt that teledermatology use will continue after COVID-19, while 58% intended to continue use—nearly 5-fold more than before the pandemic.3 We suspect the discrepancy between participants’ predictions regarding future use of teledermatology and their personal intent to use it highlights perceived barriers and limitations of the long-term success of teledermatology. Aside from reimbursement, connectivity and functionality were common concerns, emphasizing the need for innovative technological solutions.3 Moving forward, we anticipate that dermatologists will need to establish consistent workflows to establish consistent triage for the most appropriate visit—in-person visits vs teledermatology, which may include augmented, intelligence-enhanced solutions. Similar to prior clinician perspectives about which types of visits are conducive to teledermatology,2 most survey participants believed virtual visits were effective for acne, routine follow-ups, medication monitoring, and some inflammatory conditions.3

Importantly, we must be mindful of patients who may be left behind by the digital divide, such as those with lack of access to a smartphone or the internet, language barriers, or limited telehealth experience.5 Systems should be designed to provide these patients with technologic and health literacy aid or alternate modalities to access care. For example, structured methods could be introduced to provide training and instructions on how to access phone applications, computer-based programs, and more. Likewise, for those with hearing or vision deficits, it will be important to improve sound amplification and accessibility for headphones or hearing aid connectivity, as well as appropriate font size, button size, and application navigation. In remote areas, existing clinics may be used to help field specialty consultation teleconferences. Certainly, applications and platforms devised for teledermatology must be designed to serve diverse patient groups, with special consideration for the elderly, those who speak languages other than English, and those with disabilities that may make telehealth use more challenging.

Large-scale regulatory changes and reimbursement parity can have a substantial impact on future teledermatology use. Advocacy efforts continue to push for fair valuation of telemedicine, coverage of store-and-forward teledermatology codes, and coverage for all models of care. It is imperative for the dermatology community to continue discussions on implementation and methodology to best leverage this technology for the most patient benefit.

Although teledermatology utilization in the United States traditionally has lagged behind other countries,1,2 the COVID-19 pandemic upended this trend by creating the need for a massive teledermatology experiment. Recently reported survey results from a large representative sample of US dermatologists (5000 participants) on perceptions of teledermatology during COVID-19 indicated that only 14.1% of participants used teledermatology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic vs 54.1% of dermatologists in Europe.2,3 Since the pandemic started, 97% of US dermatologists reported teledermatology use,3 demonstrating a huge shift in utilization. This trend is notable, as teledermatology has been shown to increase access to dermatology in underserved areas, reduce patient travel times, improve patient triage, and even reduce carbon footprints.1,4 Thus, to sustain the momentum, insights from the recent teledermatology experience during the pandemic should inform future development.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid shift in focus from store-and-forward teledermatology to live video–based models.1,2 Logistically, live video visits are challenging, require more time and resources, and often are diagnostically limited, with concerns regarding technology, connectivity, reimbursement, and appropriate use.3 Prior to COVID-19, formal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant teledermatology platforms often were costly to establish and maintain, largely relegating use to academic centers and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thus, many fewer private practice dermatologists had used teledermatology compared to academic dermatologists in the United States (11.4% vs 27.6%).3 Government regulations—a key barrier to the adoption of teledermatology in private practice before COVID-19—were greatly relaxed during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed restrictions on where patients could be seen, improved reimbursement for video visits, and allowed the use of platforms that are not Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. Many states also relaxed medical licensing rules.

Overall, the general outlook on telehealth seems positive. Reimbursement has been found to be a primary factor in dermatologists’ willingness to use teledermatology.3 Thus, sustainable use of teledermatology likely will depend on continued reimbursement parity for live video as well as store-and-forward consultations, which have several advantages but currently are de-incentivized by low reimbursement. The survey also found that 70% of respondents felt that teledermatology use will continue after COVID-19, while 58% intended to continue use—nearly 5-fold more than before the pandemic.3 We suspect the discrepancy between participants’ predictions regarding future use of teledermatology and their personal intent to use it highlights perceived barriers and limitations of the long-term success of teledermatology. Aside from reimbursement, connectivity and functionality were common concerns, emphasizing the need for innovative technological solutions.3 Moving forward, we anticipate that dermatologists will need to establish consistent workflows to establish consistent triage for the most appropriate visit—in-person visits vs teledermatology, which may include augmented, intelligence-enhanced solutions. Similar to prior clinician perspectives about which types of visits are conducive to teledermatology,2 most survey participants believed virtual visits were effective for acne, routine follow-ups, medication monitoring, and some inflammatory conditions.3

Importantly, we must be mindful of patients who may be left behind by the digital divide, such as those with lack of access to a smartphone or the internet, language barriers, or limited telehealth experience.5 Systems should be designed to provide these patients with technologic and health literacy aid or alternate modalities to access care. For example, structured methods could be introduced to provide training and instructions on how to access phone applications, computer-based programs, and more. Likewise, for those with hearing or vision deficits, it will be important to improve sound amplification and accessibility for headphones or hearing aid connectivity, as well as appropriate font size, button size, and application navigation. In remote areas, existing clinics may be used to help field specialty consultation teleconferences. Certainly, applications and platforms devised for teledermatology must be designed to serve diverse patient groups, with special consideration for the elderly, those who speak languages other than English, and those with disabilities that may make telehealth use more challenging.

Large-scale regulatory changes and reimbursement parity can have a substantial impact on future teledermatology use. Advocacy efforts continue to push for fair valuation of telemedicine, coverage of store-and-forward teledermatology codes, and coverage for all models of care. It is imperative for the dermatology community to continue discussions on implementation and methodology to best leverage this technology for the most patient benefit.

- Tensen E, van der Heijden JP, Jaspers MWM, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Moscarella E, Pasquali P, Cinotti E, et al. A survey on teledermatology use and doctors’ perception in times of COVID-19 [published online August 17, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E772-E773.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Bonsall A. Unleashing carbon emissions savings with regular teledermatology clinics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:574-575.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.

- Tensen E, van der Heijden JP, Jaspers MWM, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Moscarella E, Pasquali P, Cinotti E, et al. A survey on teledermatology use and doctors’ perception in times of COVID-19 [published online August 17, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E772-E773.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Bonsall A. Unleashing carbon emissions savings with regular teledermatology clinics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:574-575.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.

Scaly Annular and Concentric Plaques

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

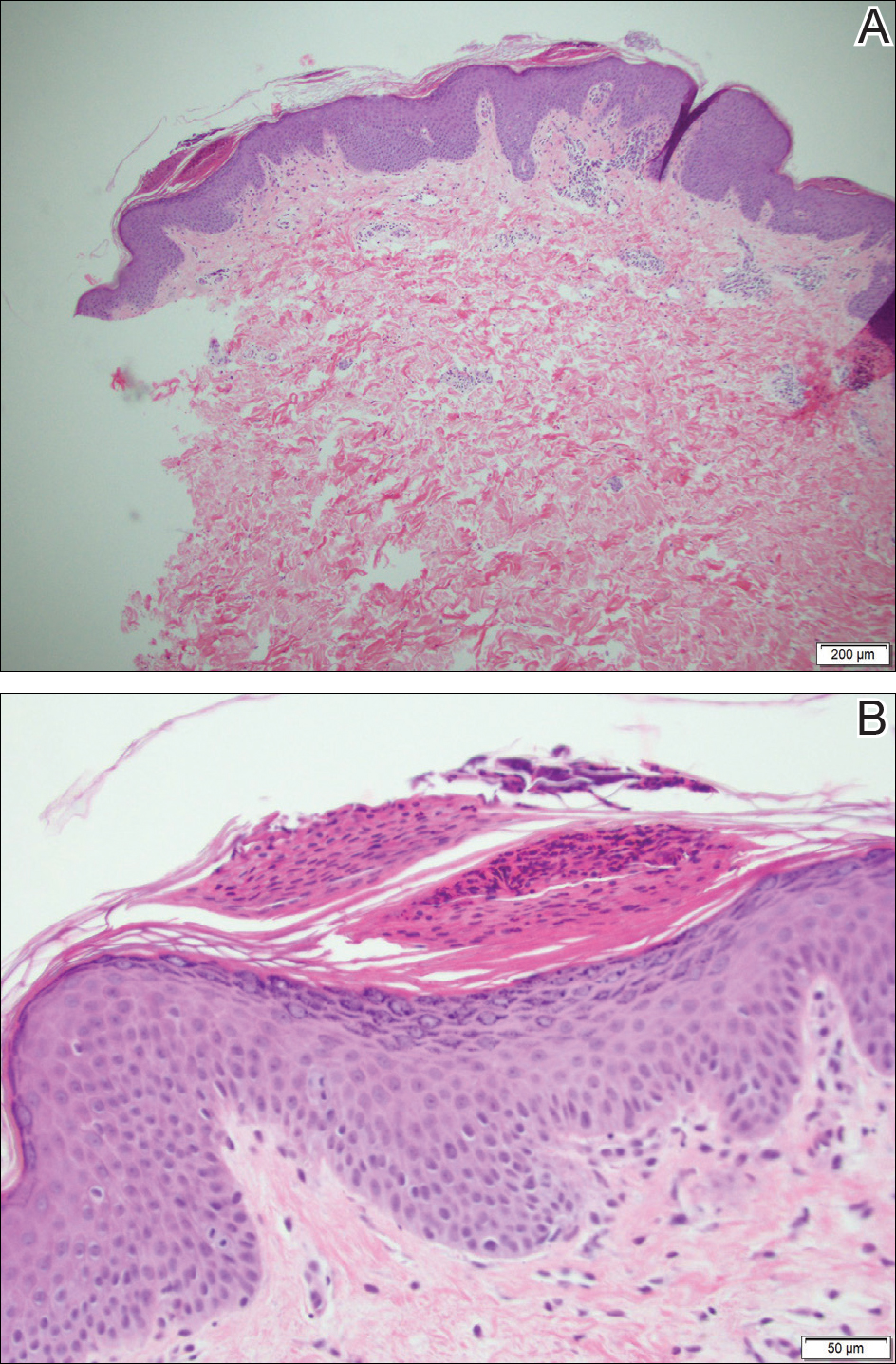

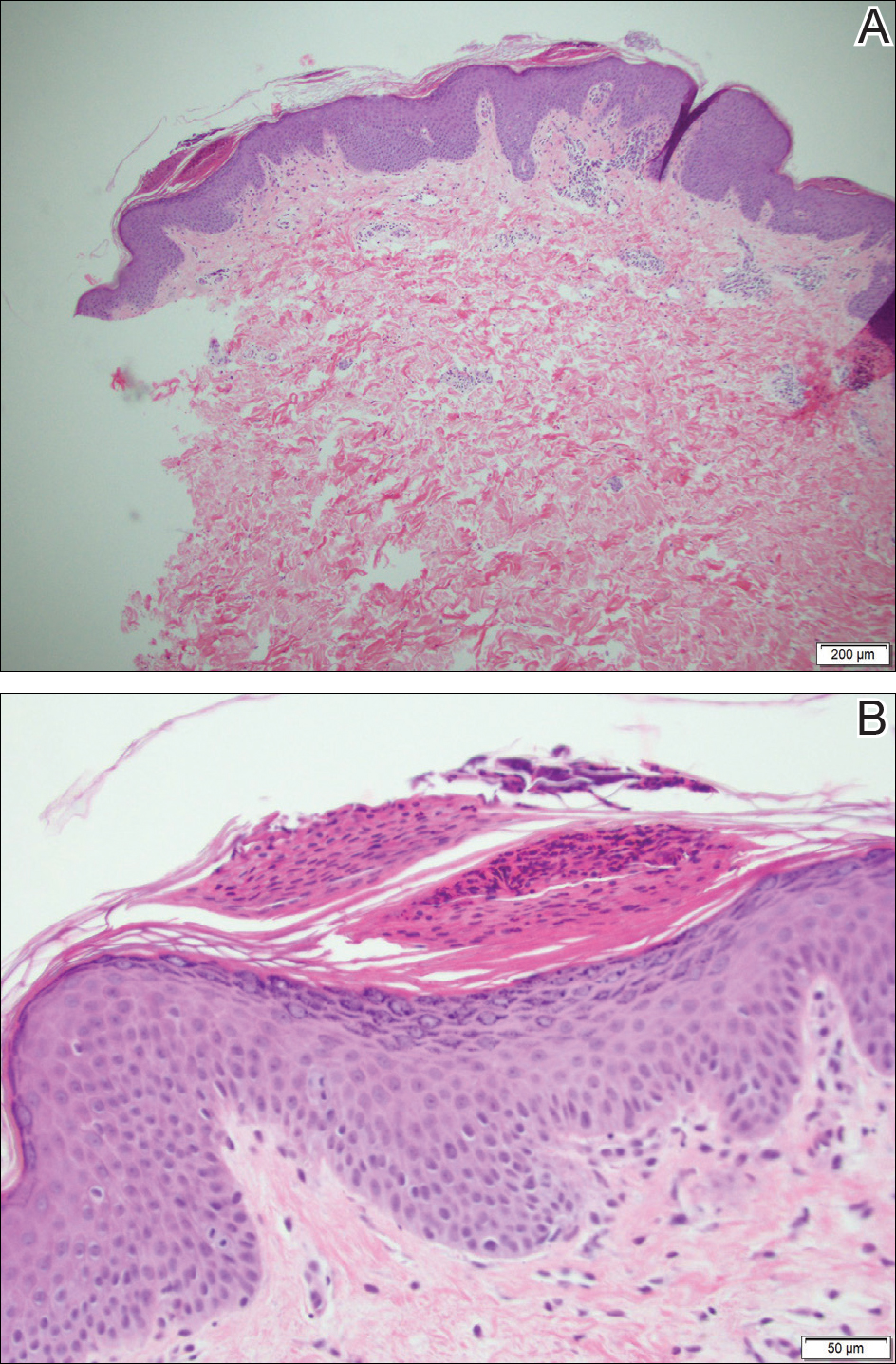

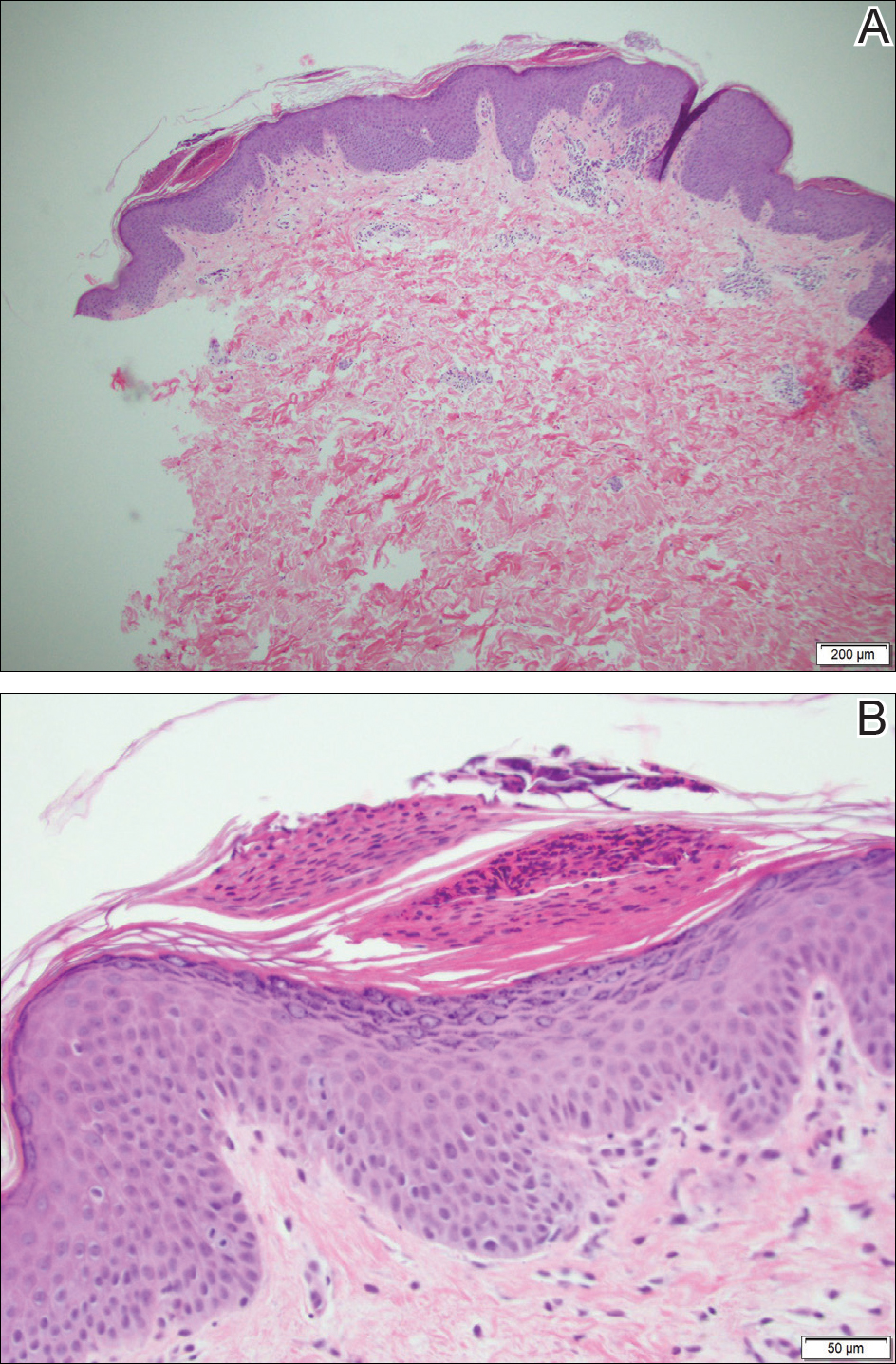

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

A healthy 23-year-old man presented for evaluation of an enlarging annular pruritic rash of 1.5 years' duration. Treatment with ciclopirox cream 0.77%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, fluticasone cream 0.05%, and halobetasol cream 0.05% prescribed by an outside physician provided only modest temporary improvement. The patient reported no history of travel outside of western New York, camping, tick bites, or medications. He denied any joint swelling or morning stiffness. Physical examination revealed multiple 4- to 6-cm pink, annular, scaly plaques with central clearing on the abdomen (top) and thighs. A few 1-cm pink scaly patches were present on the back (bottom), and few 2- to 3-mm pink scaly papules were noted on the extensor aspects of the elbows and forearms. A potassium hydroxide examination revealed no hyphal elements or yeast forms.