User login

Costs and Reimbursements for Mental Health Hospitalizations at Children’s Hospitals

Increasing numbers of children and adolescents are presenting to children’s hospitals with acute mental health crises requiring emergent or inpatient treatment.1-5 As a result, children’s hospitals are experiencing additional financial challenges because specialty mental health services are often reimbursed at lower rates than other medical services.6-9 Poor reimbursement has also been cited as a deterrent to the provision of mental health specialty care, including emergency mental health crisis services.10 The cumulative financial impact of recent trends in the provision of mental health crisis services at children’s hospitals, however, is unknown. We conducted this study to assess children’s hospitals’ costs, reimbursement, and net profits or losses when delivering inpatient mental health care.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of the Children’s Hospital Association’s Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and Revenue Management Program (RMP) databases. PHIS is an administrative and billing database that collects International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnoses, procedure codes, and hospital charges from encounters at 52 US children’s hospitals. Costs are estimated from charges using hospital-, year-, and department-specific cost-to-charge ratios. The RMP database is an add-on module to the PHIS database that captures reimbursement data submitted quarterly from 17 participating hospitals based on actual reimbursement amounts collected for each encounter.

Among the 17 participating hospitals, we included all medical (ie, not surgical or intensive care) encounters during calendar year 2017 for children older than 6 years. We stratified encounters into three diagnosis types: primary mental health diagnosis,5 suicide attempt,11 or other medical hospitalizations. We separated suicide attempts since these encounters often require care for both mental health concerns and medical complications. Eating disorders were excluded because these programs at children’s hospitals primarily focus on medical complications, require complex multispecialty support, have significantly longer hospitalizations and made up a small volume of overall mental health hospitalizations.

We stratified all analyses by inpatient or observation encounter and determined the proportion of encounters and hospital days attributed to primary mental health, suicide attempt, and other medical conditions at each hospital. One of the 17 children’s hospitals does not use observation status billing, so the observation encounters dataset includes 16 hospitals.

We summarized patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics using frequencies and percentages, comparing across diagnosis groups using chi-square tests. We calculated mean cost per day as (total cost) ÷ (total length of stay [LOS]), reimbursement per day as (total reimbursement) ÷ (total LOS) for each hospital and patient group, and margin per day as (reimbursement per day) – (cost per day). We then determined the total margin difference of caring for mental health vs caring for other medical encounters as ([margin per day for mental health] – [margin per day other medical]) × (number of mental health days). Similarly, we calculated the total margin loss for suicide attempts vs other medical encounters. After calculating profits and losses at individual hospitals, we summed total annual profits and losses to calculate cumulative annual differences. We summarized these profits and losses across all hospitals with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR).

This study of deidentified administrative data was approved by the Internal Review Board at Vanderbilt University as non-human subjects research. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Across the 17 included children’s hospitals, there were 8,521 (7.6%) mental health encounters, 3,247 (2.9%) suicide attempt encounters, and 99,937 (89.5%) other medical encounters. LOS was significantly longer for mental health hospitalizations than for suicide attempts and for other medical hospitalizations.

Hospital Characteristics

All 17 free-standing children’s hospitals in the study had an inpatient behavioral health/psychiatric consultation service, and 7 of the 17 had an inpatient behavioral health/psychiatric unit. The total number of discharges for mental health, suicide attempt, and other medical conditions per year varied (range, 2,868-13,214) across the hospitals.

Hospital Daily Profits and Losses for Mental Health, Suicide Attempt, and Other Medical Admissions

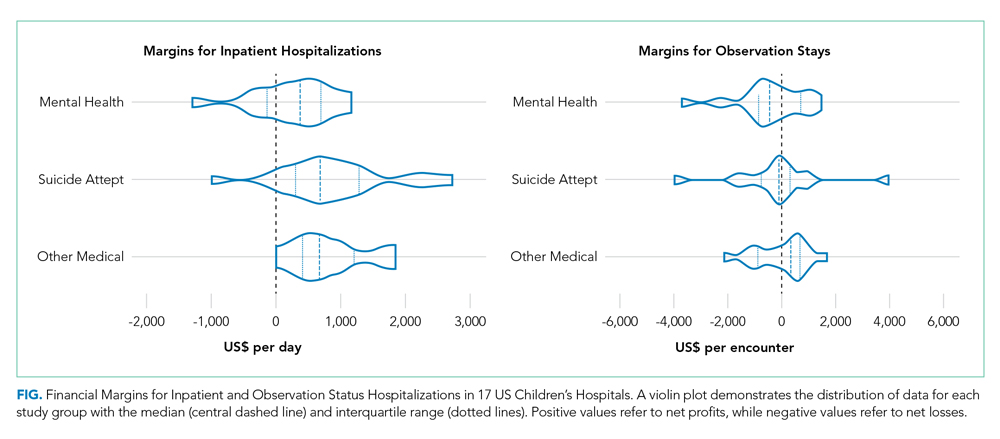

For inpatient status mental health hospitalizations, the median margin was $376/day (IQR, $23-$618). For inpatient status suicide attempt hospitalizations, the median margin was $685/day (IQR, $3-$1,117), and for other medical hospitalizations the median margin was $603/day (IQR, $240-$991). With regard to observation status admissions, mental health hospitalizations had a median margin of –$453/day (IQR, –$806 to $362), suicide attempts of –$103/day (IQR, –$639 to $264), and other medical conditions of $353/day (IQR, –$616 to $658; Figure).

Hospital Annual Profits and Losses for Mental Health and Suicide Attempt Admissions, Compared With Other Medical Admissions

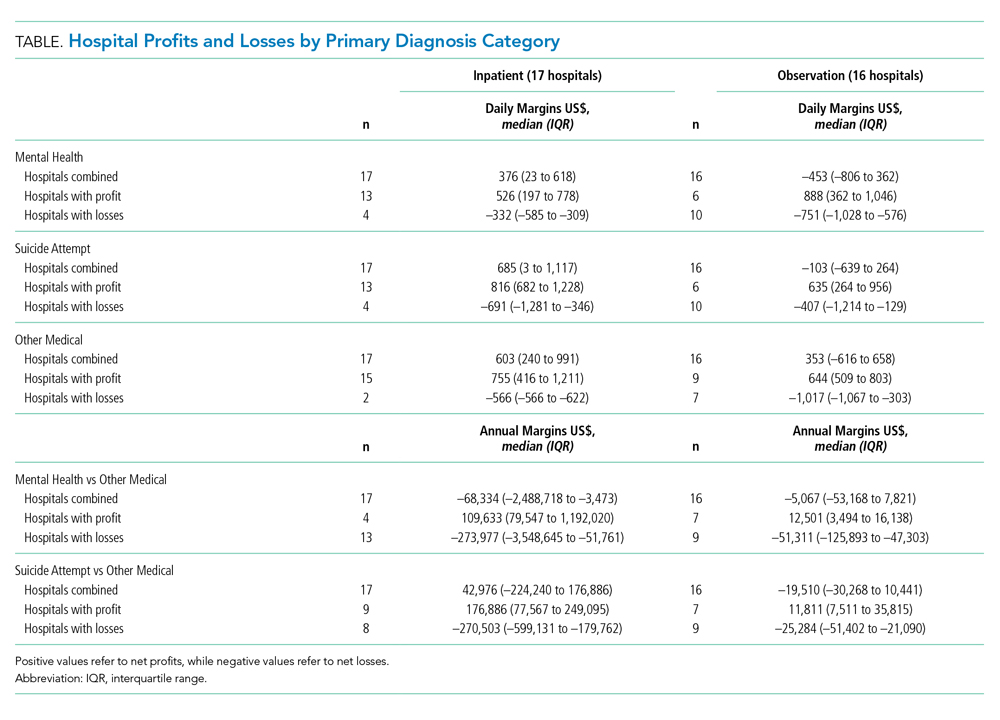

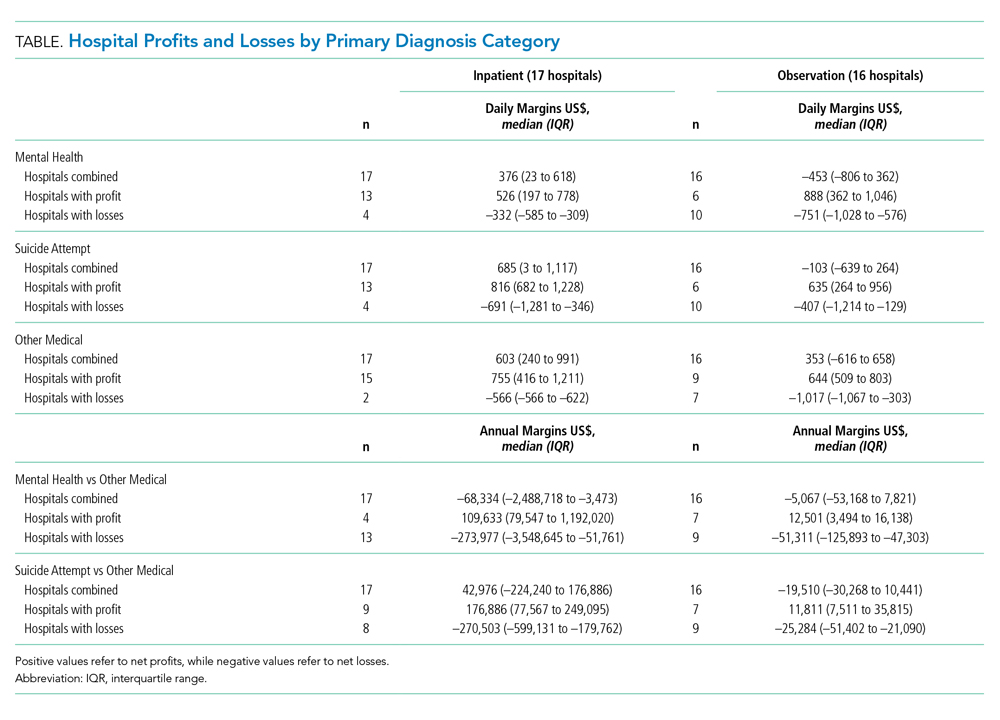

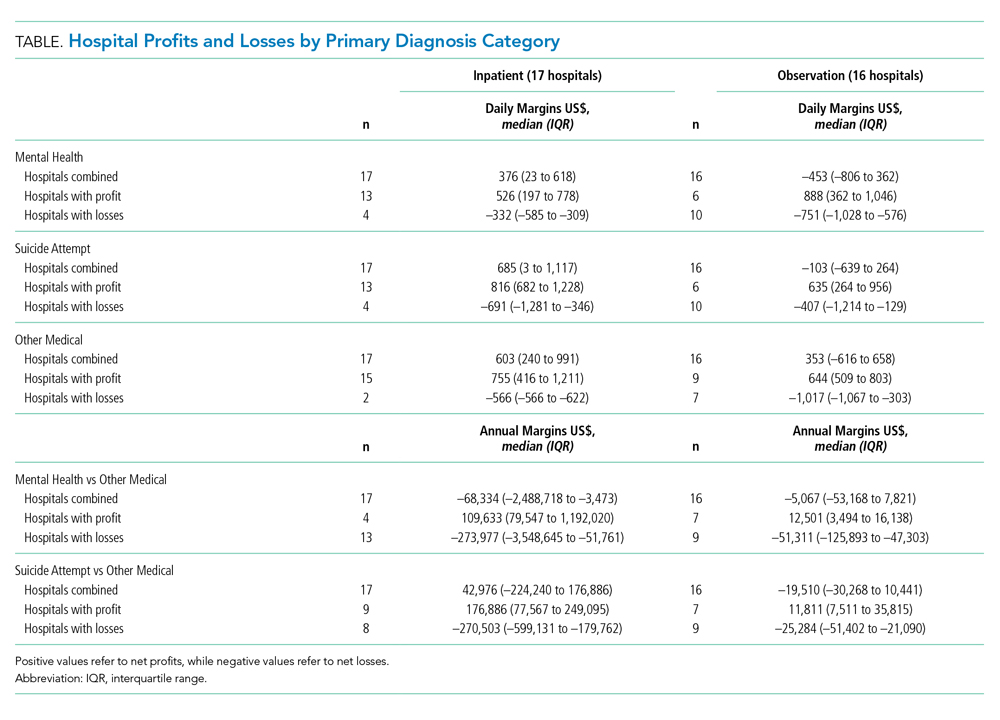

The Table shows daily and annual profits and losses for inpatient and observation status. The total annual loss across all hospitals for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, including both inpatient and observation status, was –$26,658,255 when taking both profits and losses into account. For the seven hospitals with net profits for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, the median net profit for combined inpatient and observation status encounters was $119,361 (IQR, $82,818-$195,543), and the total net profit was $5,872,665. For the 10 hospitals with net losses for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, the median net loss for combined inpatient and observation status was –$2,169,357 (IQR, –$4,034,085 to –$511,755), and the total net loss was –$27,419,379.

DISCUSSION

Hospitalizations for mental health disorders and suicide attempts accounted for 10.5% of hospitalizations at 17 US children’s hospitals in 2017. Overall, mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations had lower financial margins than did other medical hospitalizations, and they accounted for a total margin loss of more than $26 million across 17 hospitals. Seven hospitals generated a profit for mental health and suicide attempt admissions; 10 hospitals reported losses. Only three hospitals generated a higher net profit for mental health admissions than for other medical admissions. More hospitals had net profits for inpatient status mental health and suicide attempt admissions than for observation status mental health and suicide attempt admissions.

For a minority of children’s hospitals, mental health hospitalizations had higher profit margins than for other medical hospitalizations. This raises questions about patient outcomes and the type of care models employed. One potential explanation is that these hospitals have negotiated favorable agreements with payers. Another possibility could be variations in case-mix and payer mix. Certain mental health services, such as crisis response teams, social workers, and child life specialists, may also be funded from nonpayer sources, so estimates may not fully reflect the cost of providing mental health services. A worst-case view is that hospitals with higher profit margins are providing less or poorer care because of lower reimbursement.

Mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations were associated with smaller margins but counterintuitively generally wider IQRs for cost. This might be related to variation in care models, but our study was not positioned to examine reasons for this variation. The relationship between reimbursement or margins and patient outcomes, as well as specific mechanisms which may drive costs and outcomes, are areas for future research.

Health insurance plays a crucial role in mental health care. In our study, hospitals were more likely to report positive margins from inpatient status mental health hospitalizations rather than from observation status ones. This is unsurprising because payments for observation status are generally lower than for inpatient status.12 Less is known about what influences billing and payment for inpatient versus observation at individual hospitals, particularly for mental health hospitalizations. In many cases, billing status is not strictly under the hospital’s control and may be determined by payers during or after the hospitalization. Significant variability in the percentage of patients billed as observation status and the impact of lower, often negative, margins for observation mental health encounters, will have a disproportionate effect on some hospitals. Future work could investigate how these differences may influence overall costs and delivery of care.

This study has several limitations that deserve attention. Costs reported are based on cost to charge ratios, which may generate imperfect estimates. Data was limited to 17 freestanding children’s hospitals, and our findings may not generalize to other hospitals. We also compared mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations with “other medical” hospitalizations. This broad group contains certain medical conditions that may have higher or lower profit margins than average, and estimates of the margins could be over- or underestimated. We assumed that mental health and suicide attempt admissions were displacing admissions with non–mental health medical conditions (ie, not an empty bed). If those beds would otherwise be unoccupied, raw margins are better estimates of the financial impact than margin differences between mental health/suicide attempt and other medical hospitalizations.

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals are more likely to have significantly lower financial margins for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations than for other medical hospitalizations. Future work to investigate how quality of care is associated with reimbursement can help ensure that funding for children’s acute mental health care services is commensurate with resources required to provide high quality services.

Disclosures

The authors had no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MH115162 (Doupnik).

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

1. Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008-2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172426. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2426.

2. Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, et al. Mental health surveillance among children--United States, 2005-2011. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62:1-35.

3. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2016;138(6):e20161878. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1878.

4. Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;(241):1–8.

5. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric disorders and trends in resource use in pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0909.

6. Bierenbaum ML, Katsikas S, Furr A, Carter BD. Factors associated with non-reimbursable activity on an inpatient pediatric consultation-liaison service. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:464-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-013-9371-2.

7. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:176-81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862.

8. McAuliffe Lines M, Tynan WD, Angalet GB, Shroff Pendley J. Commentary: the use of health and behavior codes in pediatric psychology: where are we now? J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:486-90. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss045.

9. Drotar D. Introduction to the special section: pediatric psychologists’ experiences in obtaining reimbursement for the use of health and behavior codes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:479-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss065.

10. Komers AM. “Indiana children’s hospital shutters psychiatric unit.” Becker’s Hospital Review. 2019. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/patient-flow/indiana-children-s-hospital-shutters-psychiatric-unit.html. Accessed August 28, 2019.

11. Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1-19.

12. Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M, et al. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1050-8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2494.

Increasing numbers of children and adolescents are presenting to children’s hospitals with acute mental health crises requiring emergent or inpatient treatment.1-5 As a result, children’s hospitals are experiencing additional financial challenges because specialty mental health services are often reimbursed at lower rates than other medical services.6-9 Poor reimbursement has also been cited as a deterrent to the provision of mental health specialty care, including emergency mental health crisis services.10 The cumulative financial impact of recent trends in the provision of mental health crisis services at children’s hospitals, however, is unknown. We conducted this study to assess children’s hospitals’ costs, reimbursement, and net profits or losses when delivering inpatient mental health care.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of the Children’s Hospital Association’s Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and Revenue Management Program (RMP) databases. PHIS is an administrative and billing database that collects International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnoses, procedure codes, and hospital charges from encounters at 52 US children’s hospitals. Costs are estimated from charges using hospital-, year-, and department-specific cost-to-charge ratios. The RMP database is an add-on module to the PHIS database that captures reimbursement data submitted quarterly from 17 participating hospitals based on actual reimbursement amounts collected for each encounter.

Among the 17 participating hospitals, we included all medical (ie, not surgical or intensive care) encounters during calendar year 2017 for children older than 6 years. We stratified encounters into three diagnosis types: primary mental health diagnosis,5 suicide attempt,11 or other medical hospitalizations. We separated suicide attempts since these encounters often require care for both mental health concerns and medical complications. Eating disorders were excluded because these programs at children’s hospitals primarily focus on medical complications, require complex multispecialty support, have significantly longer hospitalizations and made up a small volume of overall mental health hospitalizations.

We stratified all analyses by inpatient or observation encounter and determined the proportion of encounters and hospital days attributed to primary mental health, suicide attempt, and other medical conditions at each hospital. One of the 17 children’s hospitals does not use observation status billing, so the observation encounters dataset includes 16 hospitals.

We summarized patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics using frequencies and percentages, comparing across diagnosis groups using chi-square tests. We calculated mean cost per day as (total cost) ÷ (total length of stay [LOS]), reimbursement per day as (total reimbursement) ÷ (total LOS) for each hospital and patient group, and margin per day as (reimbursement per day) – (cost per day). We then determined the total margin difference of caring for mental health vs caring for other medical encounters as ([margin per day for mental health] – [margin per day other medical]) × (number of mental health days). Similarly, we calculated the total margin loss for suicide attempts vs other medical encounters. After calculating profits and losses at individual hospitals, we summed total annual profits and losses to calculate cumulative annual differences. We summarized these profits and losses across all hospitals with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR).

This study of deidentified administrative data was approved by the Internal Review Board at Vanderbilt University as non-human subjects research. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Across the 17 included children’s hospitals, there were 8,521 (7.6%) mental health encounters, 3,247 (2.9%) suicide attempt encounters, and 99,937 (89.5%) other medical encounters. LOS was significantly longer for mental health hospitalizations than for suicide attempts and for other medical hospitalizations.

Hospital Characteristics

All 17 free-standing children’s hospitals in the study had an inpatient behavioral health/psychiatric consultation service, and 7 of the 17 had an inpatient behavioral health/psychiatric unit. The total number of discharges for mental health, suicide attempt, and other medical conditions per year varied (range, 2,868-13,214) across the hospitals.

Hospital Daily Profits and Losses for Mental Health, Suicide Attempt, and Other Medical Admissions

For inpatient status mental health hospitalizations, the median margin was $376/day (IQR, $23-$618). For inpatient status suicide attempt hospitalizations, the median margin was $685/day (IQR, $3-$1,117), and for other medical hospitalizations the median margin was $603/day (IQR, $240-$991). With regard to observation status admissions, mental health hospitalizations had a median margin of –$453/day (IQR, –$806 to $362), suicide attempts of –$103/day (IQR, –$639 to $264), and other medical conditions of $353/day (IQR, –$616 to $658; Figure).

Hospital Annual Profits and Losses for Mental Health and Suicide Attempt Admissions, Compared With Other Medical Admissions

The Table shows daily and annual profits and losses for inpatient and observation status. The total annual loss across all hospitals for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, including both inpatient and observation status, was –$26,658,255 when taking both profits and losses into account. For the seven hospitals with net profits for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, the median net profit for combined inpatient and observation status encounters was $119,361 (IQR, $82,818-$195,543), and the total net profit was $5,872,665. For the 10 hospitals with net losses for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, the median net loss for combined inpatient and observation status was –$2,169,357 (IQR, –$4,034,085 to –$511,755), and the total net loss was –$27,419,379.

DISCUSSION

Hospitalizations for mental health disorders and suicide attempts accounted for 10.5% of hospitalizations at 17 US children’s hospitals in 2017. Overall, mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations had lower financial margins than did other medical hospitalizations, and they accounted for a total margin loss of more than $26 million across 17 hospitals. Seven hospitals generated a profit for mental health and suicide attempt admissions; 10 hospitals reported losses. Only three hospitals generated a higher net profit for mental health admissions than for other medical admissions. More hospitals had net profits for inpatient status mental health and suicide attempt admissions than for observation status mental health and suicide attempt admissions.

For a minority of children’s hospitals, mental health hospitalizations had higher profit margins than for other medical hospitalizations. This raises questions about patient outcomes and the type of care models employed. One potential explanation is that these hospitals have negotiated favorable agreements with payers. Another possibility could be variations in case-mix and payer mix. Certain mental health services, such as crisis response teams, social workers, and child life specialists, may also be funded from nonpayer sources, so estimates may not fully reflect the cost of providing mental health services. A worst-case view is that hospitals with higher profit margins are providing less or poorer care because of lower reimbursement.

Mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations were associated with smaller margins but counterintuitively generally wider IQRs for cost. This might be related to variation in care models, but our study was not positioned to examine reasons for this variation. The relationship between reimbursement or margins and patient outcomes, as well as specific mechanisms which may drive costs and outcomes, are areas for future research.

Health insurance plays a crucial role in mental health care. In our study, hospitals were more likely to report positive margins from inpatient status mental health hospitalizations rather than from observation status ones. This is unsurprising because payments for observation status are generally lower than for inpatient status.12 Less is known about what influences billing and payment for inpatient versus observation at individual hospitals, particularly for mental health hospitalizations. In many cases, billing status is not strictly under the hospital’s control and may be determined by payers during or after the hospitalization. Significant variability in the percentage of patients billed as observation status and the impact of lower, often negative, margins for observation mental health encounters, will have a disproportionate effect on some hospitals. Future work could investigate how these differences may influence overall costs and delivery of care.

This study has several limitations that deserve attention. Costs reported are based on cost to charge ratios, which may generate imperfect estimates. Data was limited to 17 freestanding children’s hospitals, and our findings may not generalize to other hospitals. We also compared mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations with “other medical” hospitalizations. This broad group contains certain medical conditions that may have higher or lower profit margins than average, and estimates of the margins could be over- or underestimated. We assumed that mental health and suicide attempt admissions were displacing admissions with non–mental health medical conditions (ie, not an empty bed). If those beds would otherwise be unoccupied, raw margins are better estimates of the financial impact than margin differences between mental health/suicide attempt and other medical hospitalizations.

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals are more likely to have significantly lower financial margins for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations than for other medical hospitalizations. Future work to investigate how quality of care is associated with reimbursement can help ensure that funding for children’s acute mental health care services is commensurate with resources required to provide high quality services.

Disclosures

The authors had no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MH115162 (Doupnik).

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Increasing numbers of children and adolescents are presenting to children’s hospitals with acute mental health crises requiring emergent or inpatient treatment.1-5 As a result, children’s hospitals are experiencing additional financial challenges because specialty mental health services are often reimbursed at lower rates than other medical services.6-9 Poor reimbursement has also been cited as a deterrent to the provision of mental health specialty care, including emergency mental health crisis services.10 The cumulative financial impact of recent trends in the provision of mental health crisis services at children’s hospitals, however, is unknown. We conducted this study to assess children’s hospitals’ costs, reimbursement, and net profits or losses when delivering inpatient mental health care.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of the Children’s Hospital Association’s Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and Revenue Management Program (RMP) databases. PHIS is an administrative and billing database that collects International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnoses, procedure codes, and hospital charges from encounters at 52 US children’s hospitals. Costs are estimated from charges using hospital-, year-, and department-specific cost-to-charge ratios. The RMP database is an add-on module to the PHIS database that captures reimbursement data submitted quarterly from 17 participating hospitals based on actual reimbursement amounts collected for each encounter.

Among the 17 participating hospitals, we included all medical (ie, not surgical or intensive care) encounters during calendar year 2017 for children older than 6 years. We stratified encounters into three diagnosis types: primary mental health diagnosis,5 suicide attempt,11 or other medical hospitalizations. We separated suicide attempts since these encounters often require care for both mental health concerns and medical complications. Eating disorders were excluded because these programs at children’s hospitals primarily focus on medical complications, require complex multispecialty support, have significantly longer hospitalizations and made up a small volume of overall mental health hospitalizations.

We stratified all analyses by inpatient or observation encounter and determined the proportion of encounters and hospital days attributed to primary mental health, suicide attempt, and other medical conditions at each hospital. One of the 17 children’s hospitals does not use observation status billing, so the observation encounters dataset includes 16 hospitals.

We summarized patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics using frequencies and percentages, comparing across diagnosis groups using chi-square tests. We calculated mean cost per day as (total cost) ÷ (total length of stay [LOS]), reimbursement per day as (total reimbursement) ÷ (total LOS) for each hospital and patient group, and margin per day as (reimbursement per day) – (cost per day). We then determined the total margin difference of caring for mental health vs caring for other medical encounters as ([margin per day for mental health] – [margin per day other medical]) × (number of mental health days). Similarly, we calculated the total margin loss for suicide attempts vs other medical encounters. After calculating profits and losses at individual hospitals, we summed total annual profits and losses to calculate cumulative annual differences. We summarized these profits and losses across all hospitals with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR).

This study of deidentified administrative data was approved by the Internal Review Board at Vanderbilt University as non-human subjects research. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Across the 17 included children’s hospitals, there were 8,521 (7.6%) mental health encounters, 3,247 (2.9%) suicide attempt encounters, and 99,937 (89.5%) other medical encounters. LOS was significantly longer for mental health hospitalizations than for suicide attempts and for other medical hospitalizations.

Hospital Characteristics

All 17 free-standing children’s hospitals in the study had an inpatient behavioral health/psychiatric consultation service, and 7 of the 17 had an inpatient behavioral health/psychiatric unit. The total number of discharges for mental health, suicide attempt, and other medical conditions per year varied (range, 2,868-13,214) across the hospitals.

Hospital Daily Profits and Losses for Mental Health, Suicide Attempt, and Other Medical Admissions

For inpatient status mental health hospitalizations, the median margin was $376/day (IQR, $23-$618). For inpatient status suicide attempt hospitalizations, the median margin was $685/day (IQR, $3-$1,117), and for other medical hospitalizations the median margin was $603/day (IQR, $240-$991). With regard to observation status admissions, mental health hospitalizations had a median margin of –$453/day (IQR, –$806 to $362), suicide attempts of –$103/day (IQR, –$639 to $264), and other medical conditions of $353/day (IQR, –$616 to $658; Figure).

Hospital Annual Profits and Losses for Mental Health and Suicide Attempt Admissions, Compared With Other Medical Admissions

The Table shows daily and annual profits and losses for inpatient and observation status. The total annual loss across all hospitals for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, including both inpatient and observation status, was –$26,658,255 when taking both profits and losses into account. For the seven hospitals with net profits for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, the median net profit for combined inpatient and observation status encounters was $119,361 (IQR, $82,818-$195,543), and the total net profit was $5,872,665. For the 10 hospitals with net losses for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations, compared with other medical hospitalizations, the median net loss for combined inpatient and observation status was –$2,169,357 (IQR, –$4,034,085 to –$511,755), and the total net loss was –$27,419,379.

DISCUSSION

Hospitalizations for mental health disorders and suicide attempts accounted for 10.5% of hospitalizations at 17 US children’s hospitals in 2017. Overall, mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations had lower financial margins than did other medical hospitalizations, and they accounted for a total margin loss of more than $26 million across 17 hospitals. Seven hospitals generated a profit for mental health and suicide attempt admissions; 10 hospitals reported losses. Only three hospitals generated a higher net profit for mental health admissions than for other medical admissions. More hospitals had net profits for inpatient status mental health and suicide attempt admissions than for observation status mental health and suicide attempt admissions.

For a minority of children’s hospitals, mental health hospitalizations had higher profit margins than for other medical hospitalizations. This raises questions about patient outcomes and the type of care models employed. One potential explanation is that these hospitals have negotiated favorable agreements with payers. Another possibility could be variations in case-mix and payer mix. Certain mental health services, such as crisis response teams, social workers, and child life specialists, may also be funded from nonpayer sources, so estimates may not fully reflect the cost of providing mental health services. A worst-case view is that hospitals with higher profit margins are providing less or poorer care because of lower reimbursement.

Mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations were associated with smaller margins but counterintuitively generally wider IQRs for cost. This might be related to variation in care models, but our study was not positioned to examine reasons for this variation. The relationship between reimbursement or margins and patient outcomes, as well as specific mechanisms which may drive costs and outcomes, are areas for future research.

Health insurance plays a crucial role in mental health care. In our study, hospitals were more likely to report positive margins from inpatient status mental health hospitalizations rather than from observation status ones. This is unsurprising because payments for observation status are generally lower than for inpatient status.12 Less is known about what influences billing and payment for inpatient versus observation at individual hospitals, particularly for mental health hospitalizations. In many cases, billing status is not strictly under the hospital’s control and may be determined by payers during or after the hospitalization. Significant variability in the percentage of patients billed as observation status and the impact of lower, often negative, margins for observation mental health encounters, will have a disproportionate effect on some hospitals. Future work could investigate how these differences may influence overall costs and delivery of care.

This study has several limitations that deserve attention. Costs reported are based on cost to charge ratios, which may generate imperfect estimates. Data was limited to 17 freestanding children’s hospitals, and our findings may not generalize to other hospitals. We also compared mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations with “other medical” hospitalizations. This broad group contains certain medical conditions that may have higher or lower profit margins than average, and estimates of the margins could be over- or underestimated. We assumed that mental health and suicide attempt admissions were displacing admissions with non–mental health medical conditions (ie, not an empty bed). If those beds would otherwise be unoccupied, raw margins are better estimates of the financial impact than margin differences between mental health/suicide attempt and other medical hospitalizations.

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals are more likely to have significantly lower financial margins for mental health and suicide attempt hospitalizations than for other medical hospitalizations. Future work to investigate how quality of care is associated with reimbursement can help ensure that funding for children’s acute mental health care services is commensurate with resources required to provide high quality services.

Disclosures

The authors had no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MH115162 (Doupnik).

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

1. Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008-2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172426. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2426.

2. Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, et al. Mental health surveillance among children--United States, 2005-2011. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62:1-35.

3. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2016;138(6):e20161878. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1878.

4. Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;(241):1–8.

5. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric disorders and trends in resource use in pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0909.

6. Bierenbaum ML, Katsikas S, Furr A, Carter BD. Factors associated with non-reimbursable activity on an inpatient pediatric consultation-liaison service. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:464-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-013-9371-2.

7. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:176-81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862.

8. McAuliffe Lines M, Tynan WD, Angalet GB, Shroff Pendley J. Commentary: the use of health and behavior codes in pediatric psychology: where are we now? J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:486-90. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss045.

9. Drotar D. Introduction to the special section: pediatric psychologists’ experiences in obtaining reimbursement for the use of health and behavior codes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:479-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss065.

10. Komers AM. “Indiana children’s hospital shutters psychiatric unit.” Becker’s Hospital Review. 2019. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/patient-flow/indiana-children-s-hospital-shutters-psychiatric-unit.html. Accessed August 28, 2019.

11. Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1-19.

12. Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M, et al. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1050-8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2494.

1. Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008-2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172426. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2426.

2. Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, et al. Mental health surveillance among children--United States, 2005-2011. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62:1-35.

3. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2016;138(6):e20161878. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1878.

4. Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;(241):1–8.

5. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric disorders and trends in resource use in pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0909.

6. Bierenbaum ML, Katsikas S, Furr A, Carter BD. Factors associated with non-reimbursable activity on an inpatient pediatric consultation-liaison service. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:464-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-013-9371-2.

7. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:176-81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862.

8. McAuliffe Lines M, Tynan WD, Angalet GB, Shroff Pendley J. Commentary: the use of health and behavior codes in pediatric psychology: where are we now? J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:486-90. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss045.

9. Drotar D. Introduction to the special section: pediatric psychologists’ experiences in obtaining reimbursement for the use of health and behavior codes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:479-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss065.

10. Komers AM. “Indiana children’s hospital shutters psychiatric unit.” Becker’s Hospital Review. 2019. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/patient-flow/indiana-children-s-hospital-shutters-psychiatric-unit.html. Accessed August 28, 2019.

11. Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1-19.

12. Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M, et al. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1050-8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2494.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine