User login

Growth Spurt

Despite intravenous medication, a young boy in status epilepticus had the pediatric ICU team at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison stumped. The team called for a consult with the Integrative Medicine Program, which works with licensed acupuncturists and has been affiliated with the department of family medicine since 2001. Acupuncture’s efficacy in this setting has not been validated, but it has been shown to ease chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as radiation-induced xerostomia.1,2

Following several treatments by a licensed acupuncturist and continued conventional care, the boy’s seizures subsided and he was transitioned to the medical floor. Did the acupuncture contribute to bringing the seizures under control? “I can’t say that it was the acupuncture—it was probably a function of all the therapies working together,” says David P. Rakel, MD, assistant professor and director of UW’s Integrative Medicine Program.

The UW case illustrates both current trends and the constant conundrum that surrounds hospital-based complementary medicine: Complementary and alternative medicine’s use is increasing in some U.S. hospitals, yet the existing research evidence for the efficacy of its multiple modalities is decidedly mixed.

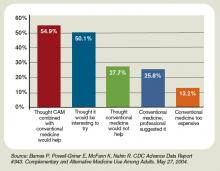

Even if your hospital does not offer complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), your patients are using CAM at ever-increasing rates. In 1993, 34% of Americans reported using some type of CAM (e.g., supplements, massage therapy, prayer, and so on). That number has almost doubled to 62%.3 Americans spend $47 billion a year—of their own money—for CAM therapies, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. And older patients with chronic conditions—the kind of patient hospitalists are most familiar with—tend to try CAM more than younger patients.4

These trends can directly affect hospitalists’ treatment decisions, but they also play a part in how you establish communication and trust with your patients, and how you keep your patients safe from adverse drug interactions. According to the National Academy of Sciences, in order to effectively counsel patients and ensure high-quality comprehensive care, conventional professionals need more CAM-related education.5

—Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, fellow, Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center

What Trends Show

In 2007, according to the American Hospital Association, 20.8% of community hospitals offered some type of care or treatment not based on traditional Western allopathic medicine. That’s up from 8.6% of reporting hospitals that offered those services in 1998.

The 1990s saw rapid growth of integrative medicine centers at major research institutions, and the majority of U.S. cancer centers now offer some form of complementary therapy, says Barrie R. Cassileth, MS, PhD, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Chair in Integrative Medicine and chief of the Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

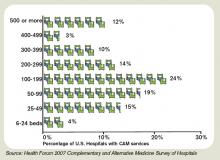

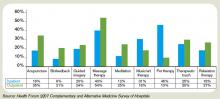

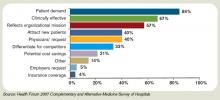

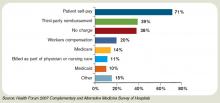

The 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals reported that complementary programs are more common in urban rather than rural hospitals; services vary by hospital size (see Figure 2, above); and the top six modalities offered on an inpatient basis are pet therapy, massage therapy, music/art therapy, guided imagery, acupuncture, and reiki (see “Glossary of Complementary Terms,” above). Eighty-four percent of hospitals offer complementary services due to patient demand, the survey showed.

Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, FHM, SHM board member and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief of the division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, doesn’t see a problem with modalities that can make his patients feel better. Patients at his hospital have access to pet therapy, massage, and acupuncture. “I don’t think these modalities hurt our patients, and there is very little downside, except for potential cost,” says Dr. Li, an SHM board member. “What’s not clear is whether these therapies work or not.”

What’s in a Name?

Numerous therapies and modalities crowd under the CAM umbrella, but most experts classify “complementary” modalities as those used in conjunction with conventional medicine to mitigate symptoms of disease or treatment, whereas “alternative” connotes therapies claiming to treat or cure the underlying disease. Some harmful, dangerous, and dishonest practices fall into the “alternative” category, such as Hulda Clark’s “Zapper” device, which was promoted as a cure for liver flukes, something she says cause everything from diabetes to heart disease. (For more on questionable practices, visit www.quackwatch.com or the National Council Against Health Fraud’s Web site at www.ncahf.org.)

The National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as a group of “diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Dr. Cassileth says the conflation of “complementary and alternative” into one neat acronym—CAM—causes confusion among patients and medical professionals. NCCAM will be changing its name soon, she says, to the National Center for Integrative Medicine, emphasizing the use of adjunctive modalities along with conventional medical treatments.

Hospitalist Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, recently completed a research fellowship at Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center. She explains that integrative medicine uses a macro model of health, claiming a middle ground between the traditional, allopathic model of treating disease.

All Kinds of Evidence

Twenty years of complementary medicine research has yielded some information about safety—namely, what works and what doesn’t. For example, saw palmetto has not panned out as an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia; St. John’s wort, useful for mild depression, interferes with many medications, including cyclosporine and warfarin, and should be avoided at least five days prior to surgery.7,8

Since NCCAM’s inception in October 1998, its research portfolio has stirred debate in the scientific community. Part of the disagreement stems from the difficulty of fitting multidimensional interventions, some of which are provider-dependent (e.g., massage or acupuncture), into the gold standard of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, explains Darshan Mehta, MD, MPH, associate director of medical education at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The manner in which the effectiveness of integrative techniques is assessed requires a higher sophistication of systems research, Dr. Mehta says.

“The way we construe evidence needs to change,” she adds.

Likely to Expand

Most private health plans do not cover complementary services, although Medicare and numerous insurance plans will reimburse treatment in conjunction with physical therapy (e.g., massage) in the outpatient setting. Twenty-three states cover chiropractic care under Medicaid, and Medicare has begun to assess the cost-effectiveness of including acupuncture—especially for postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting—in its benefits package.9 Other modalities, ranging from aromatherapy to guided imagery training, are paid for largely out-of-pocket.10

Dr. Rakel notes that the delivery of integrative medicine services at UW entails conversations with patients about out-of-pocket payments. “It can pose a barrier to the clinician-patient relationship if you give them acupuncture to help with their chemotherapy-induced nausea and then ask for their credit card,” he says.

Hospitalist Preparation

Most complementary therapies are currently offered on an outpatient basis. Because of this trend, and because they deal with acute conditions, hospitalists are less likely to be involved with complementary or integrative medicine services, says Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center hospitalist Andrew C. Ahn, MD, MPH. But that’s not to say complementary medicine is something hospitalists should ignore; patients arrive at the hospital with CAM regimens in tow. It’s the No. 1 reason, Dr. Ahn says, hospitalists should be knowledgeable and exposed to CAM therapies.

Physicians must understand patient patterns and preferences regarding allopathic and complementary medicine, says Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services and optimal healing environments at the Samueli Institute in Alexandria, Va., and author of the 2007 AHA report. She points to a 2006 survey conducted by AARP and NCCAM that found almost 70% of respondents did not tell their physicians about their complementary medicine approaches. These patients are within the age range most likely to be cared for by hospitalists, and failure to communicate about complementary treatment, such as supplemental vitamin use, could lead to safety issues. Moreover, without complete disclosure, the patient-physician relationship might not be as open as possible, Dr. Ananth says.

Many acute-care hospitalists do not have formal dietary supplement policies, and less than half of U.S. children’s hospitals require documentation of a check for drug or dietary supplement interaction.11,12 As a safety issue, it is always incumbent on hospitalists, says Dr. Li, to ask about any supplements or therapies patients are trying on their own as part of the history and physical examination. The policy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. Cassileth says, is that patients on chemotherapy or who are undergoing radiation or facing surgery must avoid herbal dietary supplements.

Beyond Safety

Dr. Bertisch advises hospitalists to pose questions about complementary therapies in an open manner, avoiding antagonistic discussions. “Even when I disagree, I try to guide them to issues about safety and nonsafety, and coax in my concerns,” she says. “The most challenging part about complementary medicine is that patients’ beliefs in these therapies may be so strong that even if the doctor says it won’t work, that will not necessarily change that belief.” A 2001 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine revealed that 70% of respondents would continue to take supplements even if a major study or their physician told them they didn’t work.13

The attraction to complementary medicine often reflects patients’ preferences for a holistic approach to health, says Dr. Ahn, or it may emanate from traditions carried with them from their country of origin. “Once you do understand their reasons for using CAM, then the patient-physician relationship can be significantly strengthened,” he says. With nearly two-thirds of Americans using some form of CAM, hospitalists need to engage in this dialogue.

Dr. Rakel agrees understanding patient culture is vital to uncovering useful information. “Most clinicians would agree that if we can match a therapy to the patient culture and belief system, we are more likely to get buy-in from the patient,” he says.

Dr. Mehta also is a clinical instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He teaches his residents to educate themselves about credentialing, certification, and licensure of complementary providers. He also asks them to maintain an open mind. He says the most important preparation for hospitalists right now is to help educate their patients to be more proactive in their own healthcare. “An engaged patient,” he says, “is better than a disengaged patient.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Deng G, Cassileth BR, Yeung KS. Complementary therapies for cancer-related symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(5):419-426.

- Kahn ST, Johnstone PA. Management of xerostomia related to radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Oncology. 2005;19(14):1827-1832.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;27(343):1-19.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569-1575.

- Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2005.

- Ananth S. 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals. Health Forum LLC. 2008.

- Bent S, Kane C, Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):557-566.

- Bauer BA. The herbal hospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2006;10(2);16-17.

- Ananth S. Applying integrative healthcare. Explore. 2009;5(2):119-120.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-52

- Bassie KL, Witmer DR, Pinto B, Bush C, Clark J, Deffenbaugh J Jr. National survey of dietary supplement policies in acute care facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(1):65-70.

- Gardiner P, Phillips RS, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Henlon S, Woolf AD. Dietary supplements: inpatient policies in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e775-781.

- Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):805-810.

Top Image Source: TETRA IMAGES

Despite intravenous medication, a young boy in status epilepticus had the pediatric ICU team at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison stumped. The team called for a consult with the Integrative Medicine Program, which works with licensed acupuncturists and has been affiliated with the department of family medicine since 2001. Acupuncture’s efficacy in this setting has not been validated, but it has been shown to ease chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as radiation-induced xerostomia.1,2

Following several treatments by a licensed acupuncturist and continued conventional care, the boy’s seizures subsided and he was transitioned to the medical floor. Did the acupuncture contribute to bringing the seizures under control? “I can’t say that it was the acupuncture—it was probably a function of all the therapies working together,” says David P. Rakel, MD, assistant professor and director of UW’s Integrative Medicine Program.

The UW case illustrates both current trends and the constant conundrum that surrounds hospital-based complementary medicine: Complementary and alternative medicine’s use is increasing in some U.S. hospitals, yet the existing research evidence for the efficacy of its multiple modalities is decidedly mixed.

Even if your hospital does not offer complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), your patients are using CAM at ever-increasing rates. In 1993, 34% of Americans reported using some type of CAM (e.g., supplements, massage therapy, prayer, and so on). That number has almost doubled to 62%.3 Americans spend $47 billion a year—of their own money—for CAM therapies, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. And older patients with chronic conditions—the kind of patient hospitalists are most familiar with—tend to try CAM more than younger patients.4

These trends can directly affect hospitalists’ treatment decisions, but they also play a part in how you establish communication and trust with your patients, and how you keep your patients safe from adverse drug interactions. According to the National Academy of Sciences, in order to effectively counsel patients and ensure high-quality comprehensive care, conventional professionals need more CAM-related education.5

—Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, fellow, Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center

What Trends Show

In 2007, according to the American Hospital Association, 20.8% of community hospitals offered some type of care or treatment not based on traditional Western allopathic medicine. That’s up from 8.6% of reporting hospitals that offered those services in 1998.

The 1990s saw rapid growth of integrative medicine centers at major research institutions, and the majority of U.S. cancer centers now offer some form of complementary therapy, says Barrie R. Cassileth, MS, PhD, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Chair in Integrative Medicine and chief of the Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

The 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals reported that complementary programs are more common in urban rather than rural hospitals; services vary by hospital size (see Figure 2, above); and the top six modalities offered on an inpatient basis are pet therapy, massage therapy, music/art therapy, guided imagery, acupuncture, and reiki (see “Glossary of Complementary Terms,” above). Eighty-four percent of hospitals offer complementary services due to patient demand, the survey showed.

Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, FHM, SHM board member and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief of the division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, doesn’t see a problem with modalities that can make his patients feel better. Patients at his hospital have access to pet therapy, massage, and acupuncture. “I don’t think these modalities hurt our patients, and there is very little downside, except for potential cost,” says Dr. Li, an SHM board member. “What’s not clear is whether these therapies work or not.”

What’s in a Name?

Numerous therapies and modalities crowd under the CAM umbrella, but most experts classify “complementary” modalities as those used in conjunction with conventional medicine to mitigate symptoms of disease or treatment, whereas “alternative” connotes therapies claiming to treat or cure the underlying disease. Some harmful, dangerous, and dishonest practices fall into the “alternative” category, such as Hulda Clark’s “Zapper” device, which was promoted as a cure for liver flukes, something she says cause everything from diabetes to heart disease. (For more on questionable practices, visit www.quackwatch.com or the National Council Against Health Fraud’s Web site at www.ncahf.org.)

The National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as a group of “diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Dr. Cassileth says the conflation of “complementary and alternative” into one neat acronym—CAM—causes confusion among patients and medical professionals. NCCAM will be changing its name soon, she says, to the National Center for Integrative Medicine, emphasizing the use of adjunctive modalities along with conventional medical treatments.

Hospitalist Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, recently completed a research fellowship at Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center. She explains that integrative medicine uses a macro model of health, claiming a middle ground between the traditional, allopathic model of treating disease.

All Kinds of Evidence

Twenty years of complementary medicine research has yielded some information about safety—namely, what works and what doesn’t. For example, saw palmetto has not panned out as an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia; St. John’s wort, useful for mild depression, interferes with many medications, including cyclosporine and warfarin, and should be avoided at least five days prior to surgery.7,8

Since NCCAM’s inception in October 1998, its research portfolio has stirred debate in the scientific community. Part of the disagreement stems from the difficulty of fitting multidimensional interventions, some of which are provider-dependent (e.g., massage or acupuncture), into the gold standard of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, explains Darshan Mehta, MD, MPH, associate director of medical education at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The manner in which the effectiveness of integrative techniques is assessed requires a higher sophistication of systems research, Dr. Mehta says.

“The way we construe evidence needs to change,” she adds.

Likely to Expand

Most private health plans do not cover complementary services, although Medicare and numerous insurance plans will reimburse treatment in conjunction with physical therapy (e.g., massage) in the outpatient setting. Twenty-three states cover chiropractic care under Medicaid, and Medicare has begun to assess the cost-effectiveness of including acupuncture—especially for postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting—in its benefits package.9 Other modalities, ranging from aromatherapy to guided imagery training, are paid for largely out-of-pocket.10

Dr. Rakel notes that the delivery of integrative medicine services at UW entails conversations with patients about out-of-pocket payments. “It can pose a barrier to the clinician-patient relationship if you give them acupuncture to help with their chemotherapy-induced nausea and then ask for their credit card,” he says.

Hospitalist Preparation

Most complementary therapies are currently offered on an outpatient basis. Because of this trend, and because they deal with acute conditions, hospitalists are less likely to be involved with complementary or integrative medicine services, says Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center hospitalist Andrew C. Ahn, MD, MPH. But that’s not to say complementary medicine is something hospitalists should ignore; patients arrive at the hospital with CAM regimens in tow. It’s the No. 1 reason, Dr. Ahn says, hospitalists should be knowledgeable and exposed to CAM therapies.

Physicians must understand patient patterns and preferences regarding allopathic and complementary medicine, says Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services and optimal healing environments at the Samueli Institute in Alexandria, Va., and author of the 2007 AHA report. She points to a 2006 survey conducted by AARP and NCCAM that found almost 70% of respondents did not tell their physicians about their complementary medicine approaches. These patients are within the age range most likely to be cared for by hospitalists, and failure to communicate about complementary treatment, such as supplemental vitamin use, could lead to safety issues. Moreover, without complete disclosure, the patient-physician relationship might not be as open as possible, Dr. Ananth says.

Many acute-care hospitalists do not have formal dietary supplement policies, and less than half of U.S. children’s hospitals require documentation of a check for drug or dietary supplement interaction.11,12 As a safety issue, it is always incumbent on hospitalists, says Dr. Li, to ask about any supplements or therapies patients are trying on their own as part of the history and physical examination. The policy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. Cassileth says, is that patients on chemotherapy or who are undergoing radiation or facing surgery must avoid herbal dietary supplements.

Beyond Safety

Dr. Bertisch advises hospitalists to pose questions about complementary therapies in an open manner, avoiding antagonistic discussions. “Even when I disagree, I try to guide them to issues about safety and nonsafety, and coax in my concerns,” she says. “The most challenging part about complementary medicine is that patients’ beliefs in these therapies may be so strong that even if the doctor says it won’t work, that will not necessarily change that belief.” A 2001 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine revealed that 70% of respondents would continue to take supplements even if a major study or their physician told them they didn’t work.13

The attraction to complementary medicine often reflects patients’ preferences for a holistic approach to health, says Dr. Ahn, or it may emanate from traditions carried with them from their country of origin. “Once you do understand their reasons for using CAM, then the patient-physician relationship can be significantly strengthened,” he says. With nearly two-thirds of Americans using some form of CAM, hospitalists need to engage in this dialogue.

Dr. Rakel agrees understanding patient culture is vital to uncovering useful information. “Most clinicians would agree that if we can match a therapy to the patient culture and belief system, we are more likely to get buy-in from the patient,” he says.

Dr. Mehta also is a clinical instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He teaches his residents to educate themselves about credentialing, certification, and licensure of complementary providers. He also asks them to maintain an open mind. He says the most important preparation for hospitalists right now is to help educate their patients to be more proactive in their own healthcare. “An engaged patient,” he says, “is better than a disengaged patient.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Deng G, Cassileth BR, Yeung KS. Complementary therapies for cancer-related symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(5):419-426.

- Kahn ST, Johnstone PA. Management of xerostomia related to radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Oncology. 2005;19(14):1827-1832.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;27(343):1-19.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569-1575.

- Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2005.

- Ananth S. 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals. Health Forum LLC. 2008.

- Bent S, Kane C, Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):557-566.

- Bauer BA. The herbal hospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2006;10(2);16-17.

- Ananth S. Applying integrative healthcare. Explore. 2009;5(2):119-120.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-52

- Bassie KL, Witmer DR, Pinto B, Bush C, Clark J, Deffenbaugh J Jr. National survey of dietary supplement policies in acute care facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(1):65-70.

- Gardiner P, Phillips RS, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Henlon S, Woolf AD. Dietary supplements: inpatient policies in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e775-781.

- Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):805-810.

Top Image Source: TETRA IMAGES

Despite intravenous medication, a young boy in status epilepticus had the pediatric ICU team at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison stumped. The team called for a consult with the Integrative Medicine Program, which works with licensed acupuncturists and has been affiliated with the department of family medicine since 2001. Acupuncture’s efficacy in this setting has not been validated, but it has been shown to ease chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as radiation-induced xerostomia.1,2

Following several treatments by a licensed acupuncturist and continued conventional care, the boy’s seizures subsided and he was transitioned to the medical floor. Did the acupuncture contribute to bringing the seizures under control? “I can’t say that it was the acupuncture—it was probably a function of all the therapies working together,” says David P. Rakel, MD, assistant professor and director of UW’s Integrative Medicine Program.

The UW case illustrates both current trends and the constant conundrum that surrounds hospital-based complementary medicine: Complementary and alternative medicine’s use is increasing in some U.S. hospitals, yet the existing research evidence for the efficacy of its multiple modalities is decidedly mixed.

Even if your hospital does not offer complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), your patients are using CAM at ever-increasing rates. In 1993, 34% of Americans reported using some type of CAM (e.g., supplements, massage therapy, prayer, and so on). That number has almost doubled to 62%.3 Americans spend $47 billion a year—of their own money—for CAM therapies, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. And older patients with chronic conditions—the kind of patient hospitalists are most familiar with—tend to try CAM more than younger patients.4

These trends can directly affect hospitalists’ treatment decisions, but they also play a part in how you establish communication and trust with your patients, and how you keep your patients safe from adverse drug interactions. According to the National Academy of Sciences, in order to effectively counsel patients and ensure high-quality comprehensive care, conventional professionals need more CAM-related education.5

—Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, fellow, Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center

What Trends Show

In 2007, according to the American Hospital Association, 20.8% of community hospitals offered some type of care or treatment not based on traditional Western allopathic medicine. That’s up from 8.6% of reporting hospitals that offered those services in 1998.

The 1990s saw rapid growth of integrative medicine centers at major research institutions, and the majority of U.S. cancer centers now offer some form of complementary therapy, says Barrie R. Cassileth, MS, PhD, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Chair in Integrative Medicine and chief of the Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

The 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals reported that complementary programs are more common in urban rather than rural hospitals; services vary by hospital size (see Figure 2, above); and the top six modalities offered on an inpatient basis are pet therapy, massage therapy, music/art therapy, guided imagery, acupuncture, and reiki (see “Glossary of Complementary Terms,” above). Eighty-four percent of hospitals offer complementary services due to patient demand, the survey showed.

Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, FHM, SHM board member and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief of the division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, doesn’t see a problem with modalities that can make his patients feel better. Patients at his hospital have access to pet therapy, massage, and acupuncture. “I don’t think these modalities hurt our patients, and there is very little downside, except for potential cost,” says Dr. Li, an SHM board member. “What’s not clear is whether these therapies work or not.”

What’s in a Name?

Numerous therapies and modalities crowd under the CAM umbrella, but most experts classify “complementary” modalities as those used in conjunction with conventional medicine to mitigate symptoms of disease or treatment, whereas “alternative” connotes therapies claiming to treat or cure the underlying disease. Some harmful, dangerous, and dishonest practices fall into the “alternative” category, such as Hulda Clark’s “Zapper” device, which was promoted as a cure for liver flukes, something she says cause everything from diabetes to heart disease. (For more on questionable practices, visit www.quackwatch.com or the National Council Against Health Fraud’s Web site at www.ncahf.org.)

The National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as a group of “diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Dr. Cassileth says the conflation of “complementary and alternative” into one neat acronym—CAM—causes confusion among patients and medical professionals. NCCAM will be changing its name soon, she says, to the National Center for Integrative Medicine, emphasizing the use of adjunctive modalities along with conventional medical treatments.

Hospitalist Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, recently completed a research fellowship at Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center. She explains that integrative medicine uses a macro model of health, claiming a middle ground between the traditional, allopathic model of treating disease.

All Kinds of Evidence

Twenty years of complementary medicine research has yielded some information about safety—namely, what works and what doesn’t. For example, saw palmetto has not panned out as an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia; St. John’s wort, useful for mild depression, interferes with many medications, including cyclosporine and warfarin, and should be avoided at least five days prior to surgery.7,8

Since NCCAM’s inception in October 1998, its research portfolio has stirred debate in the scientific community. Part of the disagreement stems from the difficulty of fitting multidimensional interventions, some of which are provider-dependent (e.g., massage or acupuncture), into the gold standard of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, explains Darshan Mehta, MD, MPH, associate director of medical education at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The manner in which the effectiveness of integrative techniques is assessed requires a higher sophistication of systems research, Dr. Mehta says.

“The way we construe evidence needs to change,” she adds.

Likely to Expand

Most private health plans do not cover complementary services, although Medicare and numerous insurance plans will reimburse treatment in conjunction with physical therapy (e.g., massage) in the outpatient setting. Twenty-three states cover chiropractic care under Medicaid, and Medicare has begun to assess the cost-effectiveness of including acupuncture—especially for postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting—in its benefits package.9 Other modalities, ranging from aromatherapy to guided imagery training, are paid for largely out-of-pocket.10

Dr. Rakel notes that the delivery of integrative medicine services at UW entails conversations with patients about out-of-pocket payments. “It can pose a barrier to the clinician-patient relationship if you give them acupuncture to help with their chemotherapy-induced nausea and then ask for their credit card,” he says.

Hospitalist Preparation

Most complementary therapies are currently offered on an outpatient basis. Because of this trend, and because they deal with acute conditions, hospitalists are less likely to be involved with complementary or integrative medicine services, says Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center hospitalist Andrew C. Ahn, MD, MPH. But that’s not to say complementary medicine is something hospitalists should ignore; patients arrive at the hospital with CAM regimens in tow. It’s the No. 1 reason, Dr. Ahn says, hospitalists should be knowledgeable and exposed to CAM therapies.

Physicians must understand patient patterns and preferences regarding allopathic and complementary medicine, says Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services and optimal healing environments at the Samueli Institute in Alexandria, Va., and author of the 2007 AHA report. She points to a 2006 survey conducted by AARP and NCCAM that found almost 70% of respondents did not tell their physicians about their complementary medicine approaches. These patients are within the age range most likely to be cared for by hospitalists, and failure to communicate about complementary treatment, such as supplemental vitamin use, could lead to safety issues. Moreover, without complete disclosure, the patient-physician relationship might not be as open as possible, Dr. Ananth says.

Many acute-care hospitalists do not have formal dietary supplement policies, and less than half of U.S. children’s hospitals require documentation of a check for drug or dietary supplement interaction.11,12 As a safety issue, it is always incumbent on hospitalists, says Dr. Li, to ask about any supplements or therapies patients are trying on their own as part of the history and physical examination. The policy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. Cassileth says, is that patients on chemotherapy or who are undergoing radiation or facing surgery must avoid herbal dietary supplements.

Beyond Safety

Dr. Bertisch advises hospitalists to pose questions about complementary therapies in an open manner, avoiding antagonistic discussions. “Even when I disagree, I try to guide them to issues about safety and nonsafety, and coax in my concerns,” she says. “The most challenging part about complementary medicine is that patients’ beliefs in these therapies may be so strong that even if the doctor says it won’t work, that will not necessarily change that belief.” A 2001 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine revealed that 70% of respondents would continue to take supplements even if a major study or their physician told them they didn’t work.13

The attraction to complementary medicine often reflects patients’ preferences for a holistic approach to health, says Dr. Ahn, or it may emanate from traditions carried with them from their country of origin. “Once you do understand their reasons for using CAM, then the patient-physician relationship can be significantly strengthened,” he says. With nearly two-thirds of Americans using some form of CAM, hospitalists need to engage in this dialogue.

Dr. Rakel agrees understanding patient culture is vital to uncovering useful information. “Most clinicians would agree that if we can match a therapy to the patient culture and belief system, we are more likely to get buy-in from the patient,” he says.

Dr. Mehta also is a clinical instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He teaches his residents to educate themselves about credentialing, certification, and licensure of complementary providers. He also asks them to maintain an open mind. He says the most important preparation for hospitalists right now is to help educate their patients to be more proactive in their own healthcare. “An engaged patient,” he says, “is better than a disengaged patient.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Deng G, Cassileth BR, Yeung KS. Complementary therapies for cancer-related symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(5):419-426.

- Kahn ST, Johnstone PA. Management of xerostomia related to radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Oncology. 2005;19(14):1827-1832.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;27(343):1-19.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569-1575.

- Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2005.

- Ananth S. 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals. Health Forum LLC. 2008.

- Bent S, Kane C, Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):557-566.

- Bauer BA. The herbal hospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2006;10(2);16-17.

- Ananth S. Applying integrative healthcare. Explore. 2009;5(2):119-120.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-52

- Bassie KL, Witmer DR, Pinto B, Bush C, Clark J, Deffenbaugh J Jr. National survey of dietary supplement policies in acute care facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(1):65-70.

- Gardiner P, Phillips RS, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Henlon S, Woolf AD. Dietary supplements: inpatient policies in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e775-781.

- Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):805-810.

Top Image Source: TETRA IMAGES

Alpesh Amin: HM's History maker

Dedication to hard work, a passion for improving health outcomes and medical curricula, a background in business administration, and a knack for team-building have catapulted Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, to the forefront of change at the University of California at Irvine Health Affairs, comprised of the UC Irvine Medical Center and School of Medicine. Those skill sets and determination have landed Dr. Amin an HM first: appointment as interim chair of an academic Department of Medicine.

Dr. Amin’s new role—he supervises 11 divisions and more than 200 faculty—means he’s responsible for the department’s budget and administration. He also is charged with advancing the department’s clinical, teaching, and research missions, demonstrating that it’s possible for hospitalists to rise through the department ranks through an HM track. And that, says Scott Flanders, SHM’s president-elect and associate professor of medicine and director of the HM program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor, “bodes well for the future of academic hospitalists at many institutions across the country.”

Traditionally, lofty hospital appointments have gone to academics with a background in biomedical and basic science research. But as academic and teaching hospitals focus more and more on quality issues and improved performance, hospitalists are positioned to advance into department leadership positions.

Dr. Amin’s appointment could signal the first of many opportunities for academic hospitalists, according to Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the HM program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Dr. Li, who served with Dr. Amin on SHM’s Board of Directors, was not surprised when Alpesh was named the first hospitalist to chair a department of medicine. “He is a very gregarious person, he’s bright, and he’s logical in his thinking,” Dr. Li says.

Career Foundation

Dr. Amin credits his family with instilling in him strong values and dedication to his work. Born in Baroda, India, he emigrated to the U.S. before his first birthday; he graduated from Northgate High School in Walnut Creek, Calif., in 1985, and from UC San Diego with a degree in bioengineering in 1989. He obtained his MD in 1994 from Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

During his internship and residency at UC Irvine, Dr. Amin pondered the possibilities of a subspecialty within internal medicine. He opted to follow his interests in medical education and healthcare outcomes and research. The HM field intrigued him, he says, “because there was an opportunity to improve on systems and patient-care delivery.” Numerous mentors along the way encouraged his interests in curriculum development and design, quality improvement, and developing delivery models for patient care.

Trendsetter

As a medical resident, Dr. Amin demonstrated a desire to become a leader and change agent. “He was truly an outstanding resident, and then he joined the faculty and did spectacularly in organizing the hospitalist program, which has become very successful,” recalls Nosratola D. Vaziri, MD, chief of the division of nephrology and hypertension at UC Irvine’s School of Medicine. Dr. Amin founded the UC Irvine hospitalist program in 1998. At the same time, he acquired his MBA in healthcare administration, thus rounding out an already impressive skill set. “The MBA has been a valuable tool,” says Dr. Amin, “because I learned—among other skills—leadership, strategic planning, developing business plans, and improving on operations.”

He has applied those techniques throughout his career, serving in various leadership roles at his institution, including medicine clerkship director, associate program director for the internal medicine residency program, vice chair for clinical affairs and quality assurance, and chief of the division of general internal medicine.

By developing and nurturing the UC Irvine hospitalist program, Dr. Amin has exhibited a deep commitment to the core missions of hospital medicine. “Our multidisciplinary program has nine different specialties managed under one program,” he notes. He has structured the program in such a way that members hold dual appointments in the HM program and their individual departments or divisions, thus creating a bridge between the HM program and other departments.

“We have an integrated group that is working together for the focus of advancement in the hospital setting, in terms of clinical care, teaching, team-building, quality and systems improvement. As a result, we’ve had great outcomes in terms of length of stay, quality, and core measures,” Dr. Amin says. “I’ve been fortunate to work with a team of hospitalist faculty who are spectacular and collectively deserve kudos for the success of our group.”

Dr. Amin has shared his passion for quality improvement and curriculum development with all of hospital medicine. As chair of SHM’s education committee, he pushed for the first education summit in 2001, securing support to form a core-curriculum task force. Four years later, Dr. Amin and a small group of industry leaders published “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (www.hospitalmedicine.org/corecomp).

“Dr. Amin has really set the trend [for improved hospital performance], not only here for the hospitalist program, but nationwide,” says David N. Bailey, MD, dean and vice chancellor for UC Irvine Health Affairs.

Bucking Tradition

Hospitalists have been advancing into leadership positions in the private sector for many years. It’s been a slower ascent in the academic medical center setting.

“Until recently, it would not have been possible to ascend to the level of chair at most academic centers unless your background was in biomedical and basic science research,” says Robert Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of HM at the University of California San Francisco, a former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld .com). “Quality, patient safety, and systems improvement were not considered to be legitimate enough academic work to garner the necessary credibility. I think that’s changing.”

Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and associate dean for graduate medical education at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans and an SHM board member, believes Dr. Amin’s interim appointment “speaks in broad strokes to the new skill set—that is, financial and organizational abilities—that are increasingly becoming valued by academic medicine.” Agendas of patient safety, quality, and delivery of efficient, cost-effective, and safe healthcare are gaining parity, Dr. Wiese says, with academic research agendas. “For one to supercede the other is not a good thing, but for the two to be in balance, I think, is a very good thing,” he says.

“Renaissance Physician”

Dr. Bailey appointed Dr. Amin to what he describes as a “long-term” interim post last June. To make his decision, Dr. Bailey consulted with 11 division chiefs, and Dr. Amin emerged as the leading candidate. “Alpesh does it all, from clinical research to leading a department to running an outstanding hospitalist service,” Dr. Bailey says. “He’s really a renaissance physician.”

The promotion coincides with another of Dr. Amin’s recent accomplishments: He received the Laureate Award for the California Southern Region 2 of the American College of Physicians.

Ever energetic, Dr. Amin is not resting on his laurels. “I’m looking forward to helping the department continue to be a flagship within the UC Irvine School of Medicine,” he says. “This is a challenging and positive opportunity to balance systems-based practice, the business of medicine, and the science of medicine.”

Dr. Amin thinks his appointment signifies the new opportunities open to the growing number of U.S. hospitalists—now more than 28,000 strong and growing every day. “This [appointment] shows that hospitalists can move in the direction of being both academic leaders and healthcare administrative leaders.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance medical writer based in California.

Dedication to hard work, a passion for improving health outcomes and medical curricula, a background in business administration, and a knack for team-building have catapulted Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, to the forefront of change at the University of California at Irvine Health Affairs, comprised of the UC Irvine Medical Center and School of Medicine. Those skill sets and determination have landed Dr. Amin an HM first: appointment as interim chair of an academic Department of Medicine.

Dr. Amin’s new role—he supervises 11 divisions and more than 200 faculty—means he’s responsible for the department’s budget and administration. He also is charged with advancing the department’s clinical, teaching, and research missions, demonstrating that it’s possible for hospitalists to rise through the department ranks through an HM track. And that, says Scott Flanders, SHM’s president-elect and associate professor of medicine and director of the HM program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor, “bodes well for the future of academic hospitalists at many institutions across the country.”

Traditionally, lofty hospital appointments have gone to academics with a background in biomedical and basic science research. But as academic and teaching hospitals focus more and more on quality issues and improved performance, hospitalists are positioned to advance into department leadership positions.

Dr. Amin’s appointment could signal the first of many opportunities for academic hospitalists, according to Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the HM program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Dr. Li, who served with Dr. Amin on SHM’s Board of Directors, was not surprised when Alpesh was named the first hospitalist to chair a department of medicine. “He is a very gregarious person, he’s bright, and he’s logical in his thinking,” Dr. Li says.

Career Foundation

Dr. Amin credits his family with instilling in him strong values and dedication to his work. Born in Baroda, India, he emigrated to the U.S. before his first birthday; he graduated from Northgate High School in Walnut Creek, Calif., in 1985, and from UC San Diego with a degree in bioengineering in 1989. He obtained his MD in 1994 from Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

During his internship and residency at UC Irvine, Dr. Amin pondered the possibilities of a subspecialty within internal medicine. He opted to follow his interests in medical education and healthcare outcomes and research. The HM field intrigued him, he says, “because there was an opportunity to improve on systems and patient-care delivery.” Numerous mentors along the way encouraged his interests in curriculum development and design, quality improvement, and developing delivery models for patient care.

Trendsetter

As a medical resident, Dr. Amin demonstrated a desire to become a leader and change agent. “He was truly an outstanding resident, and then he joined the faculty and did spectacularly in organizing the hospitalist program, which has become very successful,” recalls Nosratola D. Vaziri, MD, chief of the division of nephrology and hypertension at UC Irvine’s School of Medicine. Dr. Amin founded the UC Irvine hospitalist program in 1998. At the same time, he acquired his MBA in healthcare administration, thus rounding out an already impressive skill set. “The MBA has been a valuable tool,” says Dr. Amin, “because I learned—among other skills—leadership, strategic planning, developing business plans, and improving on operations.”

He has applied those techniques throughout his career, serving in various leadership roles at his institution, including medicine clerkship director, associate program director for the internal medicine residency program, vice chair for clinical affairs and quality assurance, and chief of the division of general internal medicine.

By developing and nurturing the UC Irvine hospitalist program, Dr. Amin has exhibited a deep commitment to the core missions of hospital medicine. “Our multidisciplinary program has nine different specialties managed under one program,” he notes. He has structured the program in such a way that members hold dual appointments in the HM program and their individual departments or divisions, thus creating a bridge between the HM program and other departments.

“We have an integrated group that is working together for the focus of advancement in the hospital setting, in terms of clinical care, teaching, team-building, quality and systems improvement. As a result, we’ve had great outcomes in terms of length of stay, quality, and core measures,” Dr. Amin says. “I’ve been fortunate to work with a team of hospitalist faculty who are spectacular and collectively deserve kudos for the success of our group.”

Dr. Amin has shared his passion for quality improvement and curriculum development with all of hospital medicine. As chair of SHM’s education committee, he pushed for the first education summit in 2001, securing support to form a core-curriculum task force. Four years later, Dr. Amin and a small group of industry leaders published “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (www.hospitalmedicine.org/corecomp).

“Dr. Amin has really set the trend [for improved hospital performance], not only here for the hospitalist program, but nationwide,” says David N. Bailey, MD, dean and vice chancellor for UC Irvine Health Affairs.

Bucking Tradition

Hospitalists have been advancing into leadership positions in the private sector for many years. It’s been a slower ascent in the academic medical center setting.

“Until recently, it would not have been possible to ascend to the level of chair at most academic centers unless your background was in biomedical and basic science research,” says Robert Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of HM at the University of California San Francisco, a former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld .com). “Quality, patient safety, and systems improvement were not considered to be legitimate enough academic work to garner the necessary credibility. I think that’s changing.”

Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and associate dean for graduate medical education at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans and an SHM board member, believes Dr. Amin’s interim appointment “speaks in broad strokes to the new skill set—that is, financial and organizational abilities—that are increasingly becoming valued by academic medicine.” Agendas of patient safety, quality, and delivery of efficient, cost-effective, and safe healthcare are gaining parity, Dr. Wiese says, with academic research agendas. “For one to supercede the other is not a good thing, but for the two to be in balance, I think, is a very good thing,” he says.

“Renaissance Physician”

Dr. Bailey appointed Dr. Amin to what he describes as a “long-term” interim post last June. To make his decision, Dr. Bailey consulted with 11 division chiefs, and Dr. Amin emerged as the leading candidate. “Alpesh does it all, from clinical research to leading a department to running an outstanding hospitalist service,” Dr. Bailey says. “He’s really a renaissance physician.”

The promotion coincides with another of Dr. Amin’s recent accomplishments: He received the Laureate Award for the California Southern Region 2 of the American College of Physicians.

Ever energetic, Dr. Amin is not resting on his laurels. “I’m looking forward to helping the department continue to be a flagship within the UC Irvine School of Medicine,” he says. “This is a challenging and positive opportunity to balance systems-based practice, the business of medicine, and the science of medicine.”

Dr. Amin thinks his appointment signifies the new opportunities open to the growing number of U.S. hospitalists—now more than 28,000 strong and growing every day. “This [appointment] shows that hospitalists can move in the direction of being both academic leaders and healthcare administrative leaders.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance medical writer based in California.

Dedication to hard work, a passion for improving health outcomes and medical curricula, a background in business administration, and a knack for team-building have catapulted Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, to the forefront of change at the University of California at Irvine Health Affairs, comprised of the UC Irvine Medical Center and School of Medicine. Those skill sets and determination have landed Dr. Amin an HM first: appointment as interim chair of an academic Department of Medicine.

Dr. Amin’s new role—he supervises 11 divisions and more than 200 faculty—means he’s responsible for the department’s budget and administration. He also is charged with advancing the department’s clinical, teaching, and research missions, demonstrating that it’s possible for hospitalists to rise through the department ranks through an HM track. And that, says Scott Flanders, SHM’s president-elect and associate professor of medicine and director of the HM program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor, “bodes well for the future of academic hospitalists at many institutions across the country.”

Traditionally, lofty hospital appointments have gone to academics with a background in biomedical and basic science research. But as academic and teaching hospitals focus more and more on quality issues and improved performance, hospitalists are positioned to advance into department leadership positions.

Dr. Amin’s appointment could signal the first of many opportunities for academic hospitalists, according to Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the HM program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Dr. Li, who served with Dr. Amin on SHM’s Board of Directors, was not surprised when Alpesh was named the first hospitalist to chair a department of medicine. “He is a very gregarious person, he’s bright, and he’s logical in his thinking,” Dr. Li says.

Career Foundation

Dr. Amin credits his family with instilling in him strong values and dedication to his work. Born in Baroda, India, he emigrated to the U.S. before his first birthday; he graduated from Northgate High School in Walnut Creek, Calif., in 1985, and from UC San Diego with a degree in bioengineering in 1989. He obtained his MD in 1994 from Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

During his internship and residency at UC Irvine, Dr. Amin pondered the possibilities of a subspecialty within internal medicine. He opted to follow his interests in medical education and healthcare outcomes and research. The HM field intrigued him, he says, “because there was an opportunity to improve on systems and patient-care delivery.” Numerous mentors along the way encouraged his interests in curriculum development and design, quality improvement, and developing delivery models for patient care.

Trendsetter

As a medical resident, Dr. Amin demonstrated a desire to become a leader and change agent. “He was truly an outstanding resident, and then he joined the faculty and did spectacularly in organizing the hospitalist program, which has become very successful,” recalls Nosratola D. Vaziri, MD, chief of the division of nephrology and hypertension at UC Irvine’s School of Medicine. Dr. Amin founded the UC Irvine hospitalist program in 1998. At the same time, he acquired his MBA in healthcare administration, thus rounding out an already impressive skill set. “The MBA has been a valuable tool,” says Dr. Amin, “because I learned—among other skills—leadership, strategic planning, developing business plans, and improving on operations.”

He has applied those techniques throughout his career, serving in various leadership roles at his institution, including medicine clerkship director, associate program director for the internal medicine residency program, vice chair for clinical affairs and quality assurance, and chief of the division of general internal medicine.

By developing and nurturing the UC Irvine hospitalist program, Dr. Amin has exhibited a deep commitment to the core missions of hospital medicine. “Our multidisciplinary program has nine different specialties managed under one program,” he notes. He has structured the program in such a way that members hold dual appointments in the HM program and their individual departments or divisions, thus creating a bridge between the HM program and other departments.

“We have an integrated group that is working together for the focus of advancement in the hospital setting, in terms of clinical care, teaching, team-building, quality and systems improvement. As a result, we’ve had great outcomes in terms of length of stay, quality, and core measures,” Dr. Amin says. “I’ve been fortunate to work with a team of hospitalist faculty who are spectacular and collectively deserve kudos for the success of our group.”

Dr. Amin has shared his passion for quality improvement and curriculum development with all of hospital medicine. As chair of SHM’s education committee, he pushed for the first education summit in 2001, securing support to form a core-curriculum task force. Four years later, Dr. Amin and a small group of industry leaders published “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (www.hospitalmedicine.org/corecomp).

“Dr. Amin has really set the trend [for improved hospital performance], not only here for the hospitalist program, but nationwide,” says David N. Bailey, MD, dean and vice chancellor for UC Irvine Health Affairs.

Bucking Tradition

Hospitalists have been advancing into leadership positions in the private sector for many years. It’s been a slower ascent in the academic medical center setting.

“Until recently, it would not have been possible to ascend to the level of chair at most academic centers unless your background was in biomedical and basic science research,” says Robert Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of HM at the University of California San Francisco, a former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld .com). “Quality, patient safety, and systems improvement were not considered to be legitimate enough academic work to garner the necessary credibility. I think that’s changing.”

Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and associate dean for graduate medical education at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans and an SHM board member, believes Dr. Amin’s interim appointment “speaks in broad strokes to the new skill set—that is, financial and organizational abilities—that are increasingly becoming valued by academic medicine.” Agendas of patient safety, quality, and delivery of efficient, cost-effective, and safe healthcare are gaining parity, Dr. Wiese says, with academic research agendas. “For one to supercede the other is not a good thing, but for the two to be in balance, I think, is a very good thing,” he says.

“Renaissance Physician”

Dr. Bailey appointed Dr. Amin to what he describes as a “long-term” interim post last June. To make his decision, Dr. Bailey consulted with 11 division chiefs, and Dr. Amin emerged as the leading candidate. “Alpesh does it all, from clinical research to leading a department to running an outstanding hospitalist service,” Dr. Bailey says. “He’s really a renaissance physician.”

The promotion coincides with another of Dr. Amin’s recent accomplishments: He received the Laureate Award for the California Southern Region 2 of the American College of Physicians.

Ever energetic, Dr. Amin is not resting on his laurels. “I’m looking forward to helping the department continue to be a flagship within the UC Irvine School of Medicine,” he says. “This is a challenging and positive opportunity to balance systems-based practice, the business of medicine, and the science of medicine.”

Dr. Amin thinks his appointment signifies the new opportunities open to the growing number of U.S. hospitalists—now more than 28,000 strong and growing every day. “This [appointment] shows that hospitalists can move in the direction of being both academic leaders and healthcare administrative leaders.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance medical writer based in California.

Ethical Gray Zones

A distraught daughter demands you place a feeding tube in her father, your patient, who has not eaten in three days. The patient’s advanced dementia, anti-coagulation therapy, and other co-morbidities suggest such a move may not be in his best interest. How do you respond?

Ethical dilemmas rarely are simple or clear cut. They often involve revisiting the same issues time and again. That’s where an ethics committee comes in, says Maj. Heather Cereste, MD, U.S. Air Force, co-director of the geriatric medicine service and chair of the bioethics committee at Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas.

Ethics committees provide oversight and assist the institution in creating policies to guide staff through ethical dilemmas, Dr. Cereste says.

“Our job at the ethics committee—and we try to make this very clear—is not to solve people’s problems or dictate care,” she says. “Our job is to provide a perspective and a way of thinking about an issue to better equip people to get through it.”

Though it seems straightforward, the notion is fraught with myriad complications.

A Range of Issues

Pediatric Hospitalist Sheldon Berkowitz, MD, medical director, Minneapolis Children’s Clinic (MCC), Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minnesota, has been involved with ethics issues for 24 years. He currently is the ethics committee chair at MCC. In his experience, he says “most [ethics committee] consults come from intensive care settings, relating to life-and-death issues.”

The issues become trickier for patients from cultures with specific traditions and beliefs surrounding death. Anita Gandhy, MD, a hospitalist board certified in hospice and palliative care, works at Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco. The family of a patient she was treating wanted to continue care for its loved one despite the fact the patient was dying. “I later found out that a baby had recently been born into the family,” Dr. Gandhy says. “In the Chinese culture, if someone dies around the time that a baby is born, that spirit will follow the baby. So the family’s desire to prolong care was consistent with their cultural beliefs.”

Ethical dilemmas surface in a variety of situations—not just related to end-of-life treatment—and between a variety of parties: patient surrogates and medical staff, members of the care team, patients and family, or among family members themselves. Physicians will face many types of conflicts:

- Who makes decisions regarding the rights and preferences of unidentified patients without designated surrogates or advance directives;

- Whether to allow medical training on the newly dead;

- Whether to agree to requests for exorbitant or unorthodox treatments;

- Whether family members can ably deliver home care for a patient who is being discharged; or

- Whether to grant sterilization requests from families of adolescent children with Down syndrome.1

Underutilized Service?

With such a wide swath of potential ethical dilemmas, it would seem intuitive for physicians to use an ethics committee when one is available. Yet, a 2005 survey of 600 U.S. hospitals by The National Center for Ethics in Health Care tells a different story. The survey found 81% of the general hospitals responding to the survey had ethics consultation services, and 100% of hospitals with more than 400 beds had such services. However, the staff sought the ethics consultation services a median of only three times in the year prior to the survey.2

Hospitalist Olivia Wendy Zachary, MD, has worked for two years at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. In that time, she has requested a total of four ethics consults. One recent consultation helped her determine the source of durable power of attorney for a patient who was a prisoner and who, because he was a felon and a ward of the state prison system, could not make his own healthcare decisions.

There are other situations, however, when Dr. Zachary refrains from asking for an ethics consult. For example, as a geriatrician conversant in the potential adverse outcomes of tube feeding patients with dementia, she makes the judgment calls in these instances.

“I feel very comfortable giving family members the data, in a way that they can understand, on the conflicts of tube feeding in demented patients,” Dr. Zachary says. “The role of the ethics committee, in my opinion, should be to answer conflicts for which you do not have the answers. … If that’s beyond your expertise—if you don’t know the studies and aren’t a geriatrician—then in that case, it might be appropriate.”

In other words, don’t call the ethics committee because you don’t have the time to clearly communicate with the family.

Call on the Committee

Medical ethics dilemmas aren’t always as straightforward as knowing the possible negative consequences of placing a feeding tube in a dementia patient. So when should you call on the ethics committee? Physicians at St. Joseph’s Hospital in St. Paul, Minn., fill out an ethics consultation request form to help the hospital determine the need for the consult.

Robert C. Moravec, MD, medical director, director of hospital medicine, and chair of the ethics committee at St. Joseph’s, says the form was created to prevent physicians from requesting consults prematurely, before they have attempted a family care conference or fully understand the issue at hand. For example, providers occasionally request ethics consults when the problem really is poor communication.

“Sometimes, when our ethics committee is consulted, we discover that there is so much emotional energy going into the issue that the participants are simply not communicating,” Dr. Cereste says. “We can help them identify that.”

Other times, the issue lies in a conflict between the physician and the patient’s family. The physician may want to move from aggressive care to a pain and palliative care approach. The family, of course, wants to stay the aggressive course. It’s not the committee’s job to resolve this conflict, Dr. Berkowitz cautions. “The role of the ethics committee should be helping to identify, delineate, and resolve ethics issues,” he explains. “The committee should not be there simply to help the attending physician accomplish their goals.”

Committee Credibility

Even if physicians know when to ask for help from an ethics committee, they only will do so if they trust the enterprise, Dr. Moravec says. Using a multidisciplinary approach has worked at St. Joseph’s, where the ethics committee is comprised of nursing clinical directors, physicians, social workers, chaplains, hospice and palliative care directors, and even dietitians, who meet monthly.

When the St. Joseph’s ethics committee convenes, members fill out a multi-page record for each patient. In addition to a summary of the patient’s medical history, goals of treatment, preferences, and expected quality of life with proposed treatments (or withdrawal thereof), the record documents the committee’s conclusions, Dr. Moravec says. One copy of the document gets incorporated into the patient’s chart, one is sent to hospital administration, and a third gets channeled to the hospital system’s organization-wide ethics committee. This reporting through the medical staff fosters physician buy-in, Dr. Moravec says.

Physicians are less likely to use the consultation services if they feel the ethics committee doesn’t have teeth, says Rachel George, MD, MBA, hospitalist at Aurora St. Luke’s Hospital in Milwaukee, and regional director of five west coast hospitalist programs for Cogent Healthcare, Inc.

The same is true for one Southern California hospitalist who preferred to remain anonymous. “I rarely call for an ethics consult because they’re rarely helpful,” she says. “Generally, the issues we bring to the ethics committee are those where the family is pushing us to provide care we think is futile, and the ethics committee really doesn’t make a decision. You don’t get the backup you need, and you end up very frustrated.”

Sometimes, the California hospitalist continues, the family needs permission from the hospital to halt futile care. Without a durable power of attorney, the care team may find itself bowing to the wishes of one family member—the outlier—who insists the patient be kept alive with aggressive measures. The inpatient palliative care team often fills the ethics gap, helping the medical team discuss end-of-life issues, goals, and desires with the family. Hospitalists, she says, sometimes need an authoritative body to say, “It is no longer ethical to do this to this patient.”

“Having a hospital committee say it’s OK to withdraw a feeding tube or stop dialysis gives a comfort level to physicians,” Dr. Moravec says, “especially if the committee involves clergy, as well as administration. That is powerful support for that doctor.”

Med Students & Residents

The key to making ethics committees more effectively and widely used is education, Dr. George says. “We need to be educating our medical students and residents a lot more aggressively than we are right now,” she asserts. “How to talk with families about end-of-life issues, what is appropriate or inappropriate care, how should you be using your ethics committees—none of that is taught.”

At Children’s Hospital and Clinics, Dr. Berkowitz meets with residents and medical students every six weeks to discuss cases with ethical dilemmas. He says house staffers have little background or experience with ethics. The American Medical Association’s Liaison Committee on Medical Education 2007-2008 survey of 126 U.S. medical colleges found medical ethics was included in one required course at all 126 colleges, and was an elective course in 61. For some perspective, a course in end-of-life care was required at 124 schools and was an elective at 69. A course in palliative care was required at 120 schools, and was an elective in 60.3

Dr. Berkowitz agrees outreach is one solution. “The longer you have an ethics committee available and doing consultations in an institution, the more you expand the knowledge about how to handle problems,” he says. “People who may have previously requested an ethics consult may now have the skills and ability to handle these issues on their own, without needing to call a consult.”

Dr. Gandhy, of Saint Francis Memorial, believes such additional knowledge helps her focus on a patient’s family, not her own plan. “If the family is not ready to withdraw the care, I realize that forcing my agenda on them can also cause suffering,” she says. “When I change my focus to ask, ‘What is going to help the patient and the family?’ sometimes I don’t even need the ethics committee, because I am then able to address the family’s concerns.”

And that’s when everybody gains. TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California and a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

1. Snyder L, Leffler C;, for the Ethics and Human Rights Committee, American College of Physicians. Ethics Manual. 5th ed.,2005.

2. Fox E, Myers S, Pearlman RA. Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: a national survey. Am J Bioeth. 2007 Feb;7(2):13-25.

3. Barzansky B, Etze SI. 2007-2008 annual medical school questionnaire part II. JAMA 2008;300(10):1221.

A distraught daughter demands you place a feeding tube in her father, your patient, who has not eaten in three days. The patient’s advanced dementia, anti-coagulation therapy, and other co-morbidities suggest such a move may not be in his best interest. How do you respond?

Ethical dilemmas rarely are simple or clear cut. They often involve revisiting the same issues time and again. That’s where an ethics committee comes in, says Maj. Heather Cereste, MD, U.S. Air Force, co-director of the geriatric medicine service and chair of the bioethics committee at Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas.

Ethics committees provide oversight and assist the institution in creating policies to guide staff through ethical dilemmas, Dr. Cereste says.

“Our job at the ethics committee—and we try to make this very clear—is not to solve people’s problems or dictate care,” she says. “Our job is to provide a perspective and a way of thinking about an issue to better equip people to get through it.”

Though it seems straightforward, the notion is fraught with myriad complications.

A Range of Issues

Pediatric Hospitalist Sheldon Berkowitz, MD, medical director, Minneapolis Children’s Clinic (MCC), Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minnesota, has been involved with ethics issues for 24 years. He currently is the ethics committee chair at MCC. In his experience, he says “most [ethics committee] consults come from intensive care settings, relating to life-and-death issues.”