User login

Rash on the thigh

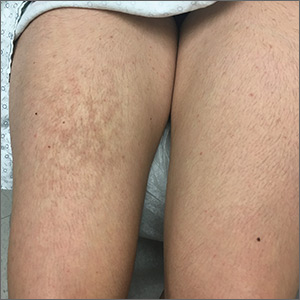

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; lcyoung@mednet.ucla.edu

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; lcyoung@mednet.ucla.edu

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; lcyoung@mednet.ucla.edu

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

Multiple Eruptive Dermatofibromas in a Patient With Sarcoidosis

To the Editor:

Dermatofibromas, the most common fibrohistiocytic tumors of the skin, are typically solitary lesions. Clustering of and multiple dermatofibromas (multiple eruptive dermatofibromas [MEDFs]) are relatively less common. The association between MEDF and systemic immunoaltered disease states such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or human immunodeficiency virus infection has been described and led to speculation that MEDF might be a result of an abnormal immune response. We report a patient with sarcoidosis who developed multiple large dermatofibromas, some clustered, on the neck, left shoulder, and back.

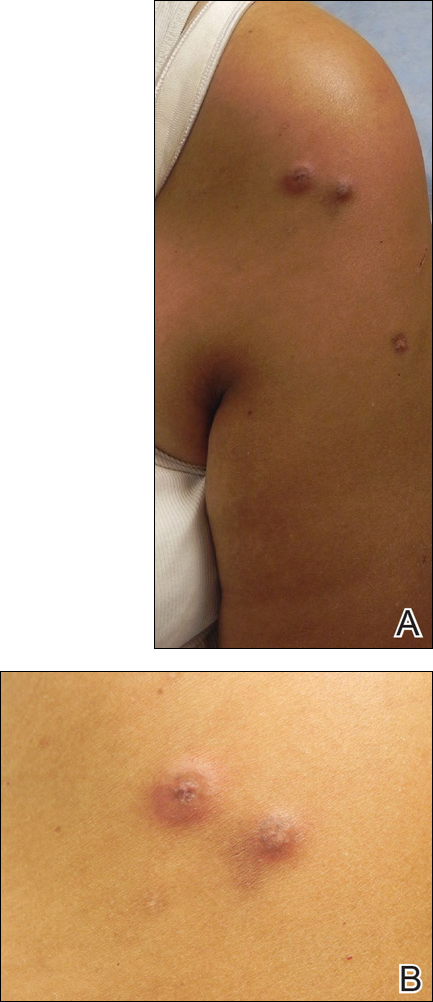

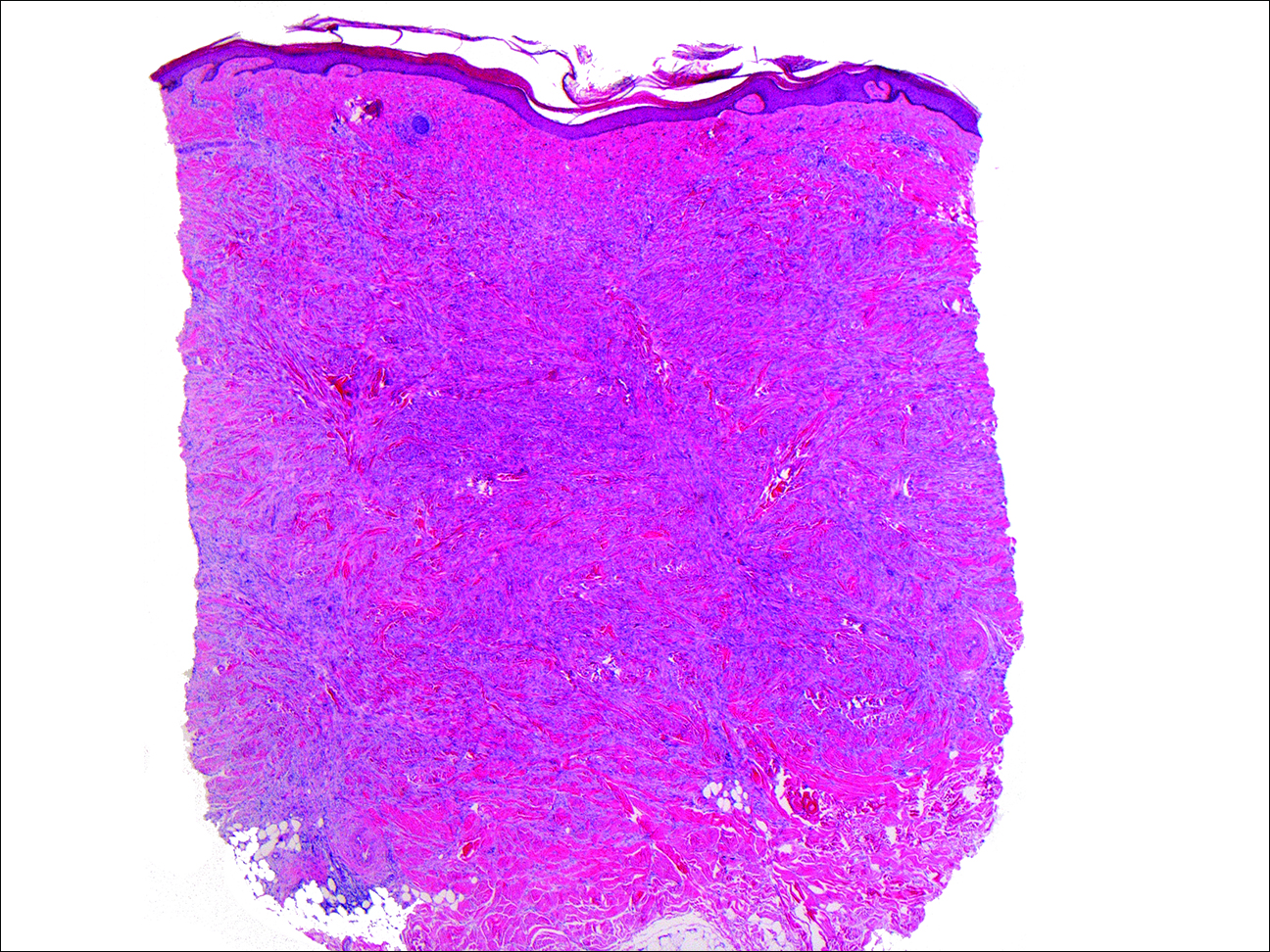

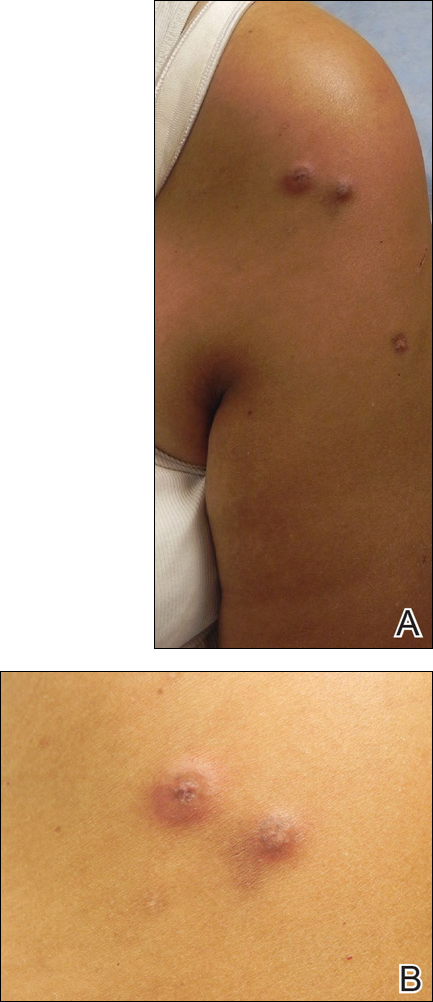

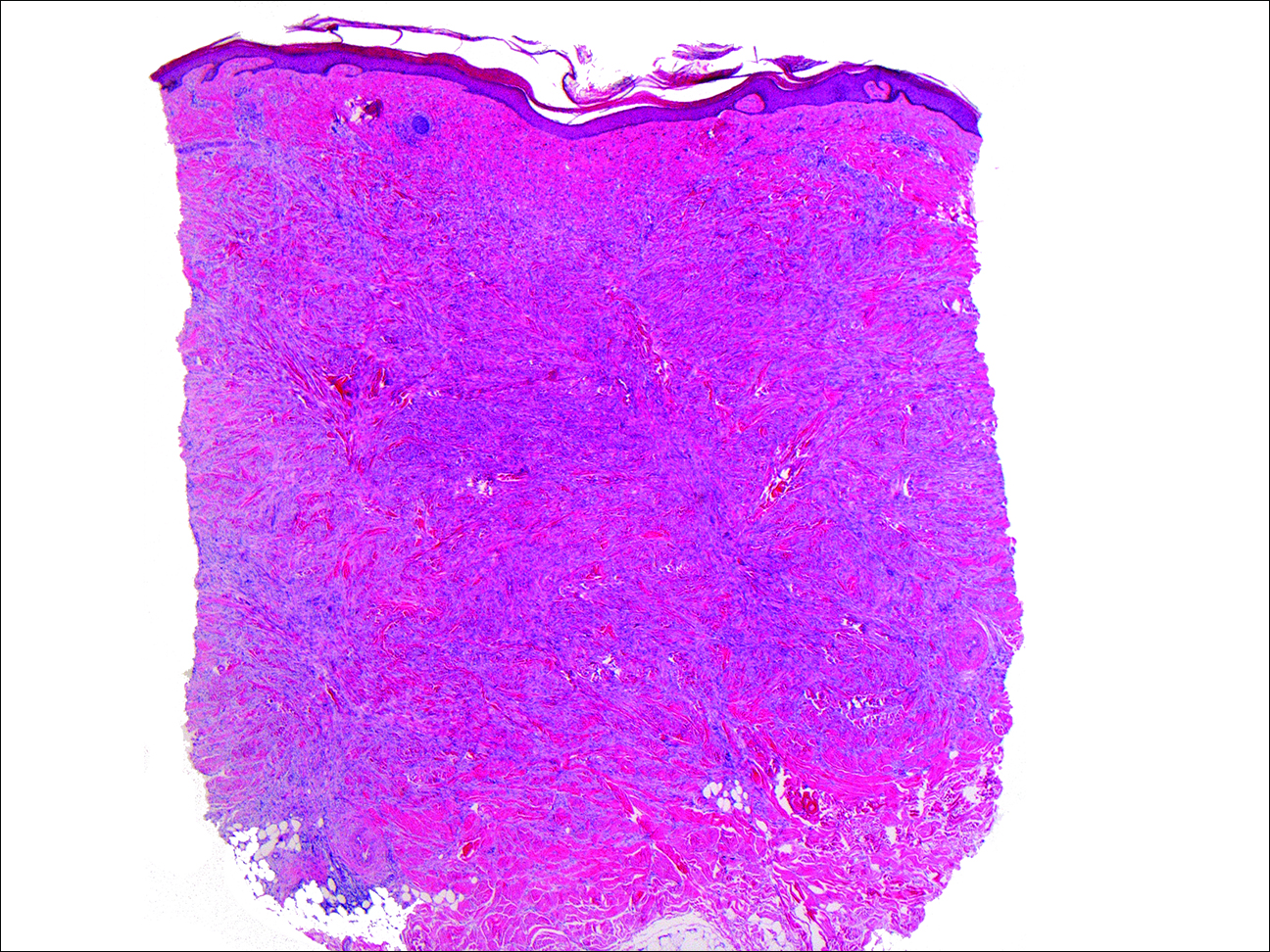

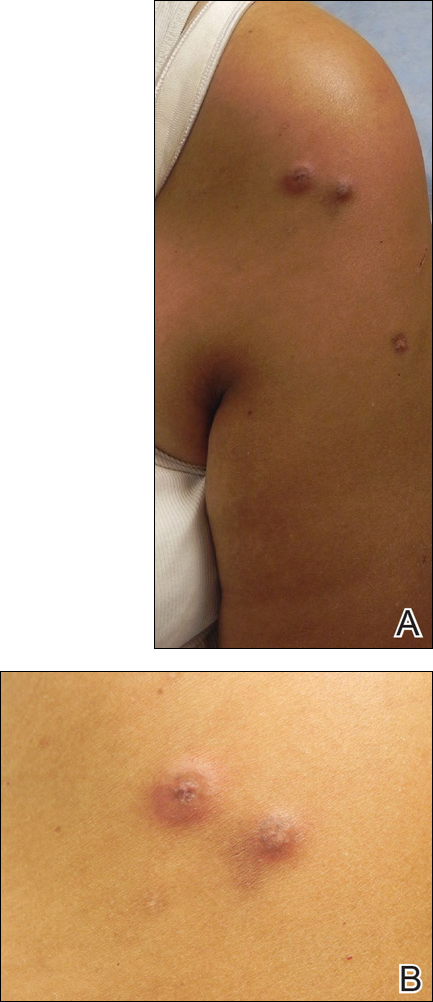

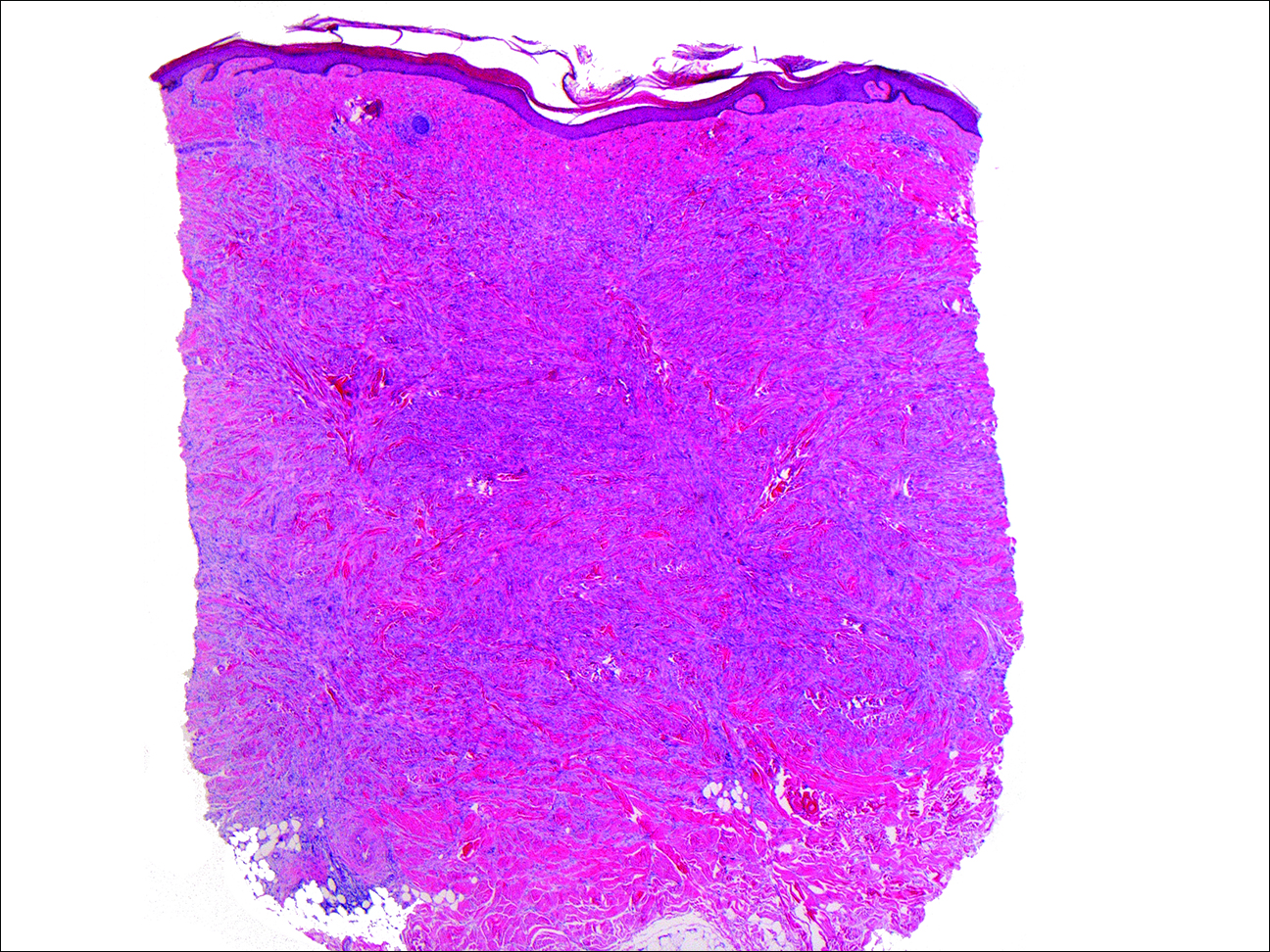

A 61-year-old woman with a history of mild pulmonary sarcoidosis confirmed by transbronchial biopsies presented to our clinic with a 2-year history of hyperpigmented papules on the trunk and extremities with subjective enlargement and increased erythema of a papule on the left shoulder over the last 6 months. She had associated pain and pruritus in the area. She was not on any systemic medications for sarcoidosis at the time. Physical examination revealed 2 large, firm, hyperpigmented nodules on the left shoulder, one with overlying erythema and mild scale (Figure 1). There also were multiple scattered hyperpigmented papules on the back, chest, and right arm that dimpled when compressed. A biopsy was obtained because of clinical concern for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Histopathologic evaluation of the largest nodule demonstrated epidermal hyperplasia with effacement of the rete ridges and a proliferation of spindle cells that wrapped around collagen fibers in the dermis, consistent with a dermatofibroma (Figure 2).

Dermatofibromas are common fibrohistiocytic neoplasms in the skin that typically present as a solitary lesion. A clustering of dermatofibromas, MEDFs, is relatively less common, representing only 0.3% of all dermatofibromas.1,2 Histopathologically, similar to solitary dermatofibromas,3 MEDF has classically been defined as more than 15 lesions, though another definition includes the appearance of several dermatofibromas over a relatively short period of time.2

Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas have been described in association with several underlying diseases. A strong association between MEDFs and immune dysregulation appears to exist, with 69% of reported cases of MEDF associated with an underlying disease, 83% of which were related to dysregulated immunity. Systemic lupus erythematosus was the most common underlying disease associated with MEDF, representing 25% of published cases.3 Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been linked to other autoimmune disorders such as myasthenia gravis,4,5 Hashimoto thyroiditis,4 diabetes mellitus,6 Sjögren syndrome,7,8 dermatomyositis,9 and Graves-Basedow disease.10

Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been linked to immunosuppression, including human immunodeficiency virus11; malignancy12,13; and immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs such as corticosteroids,14 cyclophosphamide,5 methotrexate,9 efalizumab,15 and interferon alfa.12 The degree of immunosuppression, however, does not seem to correlate to the number of MEDFs.3 In addition, MEDFs have been reported in pregnancy and a variety of other systemic disorders including atopic dermatitis,1,16,17 hypertriglyceridemia,8 and pulmonary hypertension.18 We report a case of MEDF in a patient with sarcoidosis who was not treated with immunosuppressive medication. A report of sarcoidosis and MEDF was previously published, but the patient had been treated for many years with prednisone.19 Most reports of SLE-associated MEDF occurred in the setting of steroid use.

Although the etiology of dermatofibromas is unclear, the link between MEDFs and altered immunity has led to speculation that dermatofibromas could be a manifestation of defective autoimmune inflammatory regulation. This hypothesis has been supported by the observation that the lesions are often associated with cells that express class II MHC molecules and also bear morphologic similarity to dermal antigen-presenting cells.20 Reports of familial cases of MEDF suggest that there could be a genetic predisposition.1

The association of MEDFs and underlying immune disorders is important for clinicians to know for appropriate evaluation of potential systemic associations, including sarcoidosis. In addition, biopsy should be considered to confirm the diagnosis with large or atypical lesions to exclude other potential diagnoses. Given the protean nature of sarcoidosis, skin biopsy often is indicated to identify whether cutaneous findings are granulomatous sarcoid-related manifestations. The association of MEDFs with sarcoidosis requires further evaluation but might provide keys to understanding the pathophysiology of these lesions.

- Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G, et al. Familial eruptive dermatofibromas in atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:90-92.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K, Happle R, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:241-244.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Kimura Y, Kaneko T, Akasaka E, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and myasthenia gravis. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:538-539.

- Bargman HB, Fefferman I. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with myasthenia gravis treated with prednisone and cyclophosphamide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:351-352.

- Gelfarb M, Hyman AB. Multiple noduli cutanei. an unusual case of multiple noduli cutanei in a patient with hydronephrosis. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:89-94.

- Yamamoto T, Katayama I, Nishioka K. Mast cell numbers in multiple dermatofibromas. Dermatology. 1995;190:9-13.

- Tsunemi Y, Tada Y, Saeki H, et al. Multiple dermatofibromas in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:483-485.

- Huang PY, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with dermatomyositis taking prednisolone and methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl 5):S81-S84.

- Lopez N, Fernandez A, Bosch RJ, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with Graves-Basedow disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:402-403.

- Gualandri L, Betti R, Cerri A, et al. Eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:45-47.

- Alexandrescu DT, Wiernik PH. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas occurring in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:397-398.

- Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas occurring in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1062-1063.

- Cohen PR. Multiple dermatofibromas in patients with autoimmune disorders receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:266-270.

- Santos-Juanes J, Coto-Segura P, Mallo S, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient receiving efalizumab. Dermatology. 2008;216:363.

- Stainforth J, Goodfield MJ. Multiple dermatofibromata developing during pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:59-60.

- Ashworth J, Archard L, Woodrow D, et al. Multiple eruptive histiocytoma cutis in an atopic. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:454-456.

- Lee HW, Lee DK, Oh SH, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with primary pulmonary hypertension. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:845-847.

- Veraldi S, Drudi E, Gianotti R. Multiple, eruptive dermatofibromas. Eur J Dermatol. 1996;6:523-524.

- Nestle FO, Nickeloff BJ, Burg G. Dermatofibroma: an abortive immunoreactive process mediated by dermal dendritic cells? Dermatology. 1995;190:265-268.

To the Editor:

Dermatofibromas, the most common fibrohistiocytic tumors of the skin, are typically solitary lesions. Clustering of and multiple dermatofibromas (multiple eruptive dermatofibromas [MEDFs]) are relatively less common. The association between MEDF and systemic immunoaltered disease states such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or human immunodeficiency virus infection has been described and led to speculation that MEDF might be a result of an abnormal immune response. We report a patient with sarcoidosis who developed multiple large dermatofibromas, some clustered, on the neck, left shoulder, and back.

A 61-year-old woman with a history of mild pulmonary sarcoidosis confirmed by transbronchial biopsies presented to our clinic with a 2-year history of hyperpigmented papules on the trunk and extremities with subjective enlargement and increased erythema of a papule on the left shoulder over the last 6 months. She had associated pain and pruritus in the area. She was not on any systemic medications for sarcoidosis at the time. Physical examination revealed 2 large, firm, hyperpigmented nodules on the left shoulder, one with overlying erythema and mild scale (Figure 1). There also were multiple scattered hyperpigmented papules on the back, chest, and right arm that dimpled when compressed. A biopsy was obtained because of clinical concern for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Histopathologic evaluation of the largest nodule demonstrated epidermal hyperplasia with effacement of the rete ridges and a proliferation of spindle cells that wrapped around collagen fibers in the dermis, consistent with a dermatofibroma (Figure 2).

Dermatofibromas are common fibrohistiocytic neoplasms in the skin that typically present as a solitary lesion. A clustering of dermatofibromas, MEDFs, is relatively less common, representing only 0.3% of all dermatofibromas.1,2 Histopathologically, similar to solitary dermatofibromas,3 MEDF has classically been defined as more than 15 lesions, though another definition includes the appearance of several dermatofibromas over a relatively short period of time.2

Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas have been described in association with several underlying diseases. A strong association between MEDFs and immune dysregulation appears to exist, with 69% of reported cases of MEDF associated with an underlying disease, 83% of which were related to dysregulated immunity. Systemic lupus erythematosus was the most common underlying disease associated with MEDF, representing 25% of published cases.3 Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been linked to other autoimmune disorders such as myasthenia gravis,4,5 Hashimoto thyroiditis,4 diabetes mellitus,6 Sjögren syndrome,7,8 dermatomyositis,9 and Graves-Basedow disease.10

Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been linked to immunosuppression, including human immunodeficiency virus11; malignancy12,13; and immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs such as corticosteroids,14 cyclophosphamide,5 methotrexate,9 efalizumab,15 and interferon alfa.12 The degree of immunosuppression, however, does not seem to correlate to the number of MEDFs.3 In addition, MEDFs have been reported in pregnancy and a variety of other systemic disorders including atopic dermatitis,1,16,17 hypertriglyceridemia,8 and pulmonary hypertension.18 We report a case of MEDF in a patient with sarcoidosis who was not treated with immunosuppressive medication. A report of sarcoidosis and MEDF was previously published, but the patient had been treated for many years with prednisone.19 Most reports of SLE-associated MEDF occurred in the setting of steroid use.

Although the etiology of dermatofibromas is unclear, the link between MEDFs and altered immunity has led to speculation that dermatofibromas could be a manifestation of defective autoimmune inflammatory regulation. This hypothesis has been supported by the observation that the lesions are often associated with cells that express class II MHC molecules and also bear morphologic similarity to dermal antigen-presenting cells.20 Reports of familial cases of MEDF suggest that there could be a genetic predisposition.1

The association of MEDFs and underlying immune disorders is important for clinicians to know for appropriate evaluation of potential systemic associations, including sarcoidosis. In addition, biopsy should be considered to confirm the diagnosis with large or atypical lesions to exclude other potential diagnoses. Given the protean nature of sarcoidosis, skin biopsy often is indicated to identify whether cutaneous findings are granulomatous sarcoid-related manifestations. The association of MEDFs with sarcoidosis requires further evaluation but might provide keys to understanding the pathophysiology of these lesions.

To the Editor:

Dermatofibromas, the most common fibrohistiocytic tumors of the skin, are typically solitary lesions. Clustering of and multiple dermatofibromas (multiple eruptive dermatofibromas [MEDFs]) are relatively less common. The association between MEDF and systemic immunoaltered disease states such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or human immunodeficiency virus infection has been described and led to speculation that MEDF might be a result of an abnormal immune response. We report a patient with sarcoidosis who developed multiple large dermatofibromas, some clustered, on the neck, left shoulder, and back.

A 61-year-old woman with a history of mild pulmonary sarcoidosis confirmed by transbronchial biopsies presented to our clinic with a 2-year history of hyperpigmented papules on the trunk and extremities with subjective enlargement and increased erythema of a papule on the left shoulder over the last 6 months. She had associated pain and pruritus in the area. She was not on any systemic medications for sarcoidosis at the time. Physical examination revealed 2 large, firm, hyperpigmented nodules on the left shoulder, one with overlying erythema and mild scale (Figure 1). There also were multiple scattered hyperpigmented papules on the back, chest, and right arm that dimpled when compressed. A biopsy was obtained because of clinical concern for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Histopathologic evaluation of the largest nodule demonstrated epidermal hyperplasia with effacement of the rete ridges and a proliferation of spindle cells that wrapped around collagen fibers in the dermis, consistent with a dermatofibroma (Figure 2).

Dermatofibromas are common fibrohistiocytic neoplasms in the skin that typically present as a solitary lesion. A clustering of dermatofibromas, MEDFs, is relatively less common, representing only 0.3% of all dermatofibromas.1,2 Histopathologically, similar to solitary dermatofibromas,3 MEDF has classically been defined as more than 15 lesions, though another definition includes the appearance of several dermatofibromas over a relatively short period of time.2

Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas have been described in association with several underlying diseases. A strong association between MEDFs and immune dysregulation appears to exist, with 69% of reported cases of MEDF associated with an underlying disease, 83% of which were related to dysregulated immunity. Systemic lupus erythematosus was the most common underlying disease associated with MEDF, representing 25% of published cases.3 Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been linked to other autoimmune disorders such as myasthenia gravis,4,5 Hashimoto thyroiditis,4 diabetes mellitus,6 Sjögren syndrome,7,8 dermatomyositis,9 and Graves-Basedow disease.10

Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been linked to immunosuppression, including human immunodeficiency virus11; malignancy12,13; and immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs such as corticosteroids,14 cyclophosphamide,5 methotrexate,9 efalizumab,15 and interferon alfa.12 The degree of immunosuppression, however, does not seem to correlate to the number of MEDFs.3 In addition, MEDFs have been reported in pregnancy and a variety of other systemic disorders including atopic dermatitis,1,16,17 hypertriglyceridemia,8 and pulmonary hypertension.18 We report a case of MEDF in a patient with sarcoidosis who was not treated with immunosuppressive medication. A report of sarcoidosis and MEDF was previously published, but the patient had been treated for many years with prednisone.19 Most reports of SLE-associated MEDF occurred in the setting of steroid use.

Although the etiology of dermatofibromas is unclear, the link between MEDFs and altered immunity has led to speculation that dermatofibromas could be a manifestation of defective autoimmune inflammatory regulation. This hypothesis has been supported by the observation that the lesions are often associated with cells that express class II MHC molecules and also bear morphologic similarity to dermal antigen-presenting cells.20 Reports of familial cases of MEDF suggest that there could be a genetic predisposition.1

The association of MEDFs and underlying immune disorders is important for clinicians to know for appropriate evaluation of potential systemic associations, including sarcoidosis. In addition, biopsy should be considered to confirm the diagnosis with large or atypical lesions to exclude other potential diagnoses. Given the protean nature of sarcoidosis, skin biopsy often is indicated to identify whether cutaneous findings are granulomatous sarcoid-related manifestations. The association of MEDFs with sarcoidosis requires further evaluation but might provide keys to understanding the pathophysiology of these lesions.

- Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G, et al. Familial eruptive dermatofibromas in atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:90-92.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K, Happle R, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:241-244.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Kimura Y, Kaneko T, Akasaka E, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and myasthenia gravis. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:538-539.

- Bargman HB, Fefferman I. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with myasthenia gravis treated with prednisone and cyclophosphamide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:351-352.

- Gelfarb M, Hyman AB. Multiple noduli cutanei. an unusual case of multiple noduli cutanei in a patient with hydronephrosis. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:89-94.

- Yamamoto T, Katayama I, Nishioka K. Mast cell numbers in multiple dermatofibromas. Dermatology. 1995;190:9-13.

- Tsunemi Y, Tada Y, Saeki H, et al. Multiple dermatofibromas in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:483-485.

- Huang PY, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with dermatomyositis taking prednisolone and methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl 5):S81-S84.

- Lopez N, Fernandez A, Bosch RJ, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with Graves-Basedow disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:402-403.

- Gualandri L, Betti R, Cerri A, et al. Eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:45-47.

- Alexandrescu DT, Wiernik PH. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas occurring in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:397-398.

- Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas occurring in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1062-1063.

- Cohen PR. Multiple dermatofibromas in patients with autoimmune disorders receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:266-270.

- Santos-Juanes J, Coto-Segura P, Mallo S, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient receiving efalizumab. Dermatology. 2008;216:363.

- Stainforth J, Goodfield MJ. Multiple dermatofibromata developing during pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:59-60.

- Ashworth J, Archard L, Woodrow D, et al. Multiple eruptive histiocytoma cutis in an atopic. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:454-456.

- Lee HW, Lee DK, Oh SH, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with primary pulmonary hypertension. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:845-847.

- Veraldi S, Drudi E, Gianotti R. Multiple, eruptive dermatofibromas. Eur J Dermatol. 1996;6:523-524.

- Nestle FO, Nickeloff BJ, Burg G. Dermatofibroma: an abortive immunoreactive process mediated by dermal dendritic cells? Dermatology. 1995;190:265-268.

- Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G, et al. Familial eruptive dermatofibromas in atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:90-92.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K, Happle R, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:241-244.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Kimura Y, Kaneko T, Akasaka E, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and myasthenia gravis. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:538-539.

- Bargman HB, Fefferman I. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with myasthenia gravis treated with prednisone and cyclophosphamide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:351-352.

- Gelfarb M, Hyman AB. Multiple noduli cutanei. an unusual case of multiple noduli cutanei in a patient with hydronephrosis. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:89-94.

- Yamamoto T, Katayama I, Nishioka K. Mast cell numbers in multiple dermatofibromas. Dermatology. 1995;190:9-13.

- Tsunemi Y, Tada Y, Saeki H, et al. Multiple dermatofibromas in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:483-485.

- Huang PY, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with dermatomyositis taking prednisolone and methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl 5):S81-S84.

- Lopez N, Fernandez A, Bosch RJ, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with Graves-Basedow disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:402-403.

- Gualandri L, Betti R, Cerri A, et al. Eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:45-47.

- Alexandrescu DT, Wiernik PH. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas occurring in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:397-398.

- Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas occurring in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1062-1063.

- Cohen PR. Multiple dermatofibromas in patients with autoimmune disorders receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:266-270.

- Santos-Juanes J, Coto-Segura P, Mallo S, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient receiving efalizumab. Dermatology. 2008;216:363.

- Stainforth J, Goodfield MJ. Multiple dermatofibromata developing during pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:59-60.

- Ashworth J, Archard L, Woodrow D, et al. Multiple eruptive histiocytoma cutis in an atopic. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:454-456.

- Lee HW, Lee DK, Oh SH, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with primary pulmonary hypertension. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:845-847.

- Veraldi S, Drudi E, Gianotti R. Multiple, eruptive dermatofibromas. Eur J Dermatol. 1996;6:523-524.

- Nestle FO, Nickeloff BJ, Burg G. Dermatofibroma: an abortive immunoreactive process mediated by dermal dendritic cells? Dermatology. 1995;190:265-268.

Practice Points

- Sarcoidosis can present with multiple cutaneous morphologies and dermatologists should have a low threshold to perform skin biopsy to confirm sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation.

- Dermatofibromas can occur in greater numbers in patients with immune dysregulation such as human immunodeficiency virus and systemic lupus erythematosus.