User login

Rash on the thigh

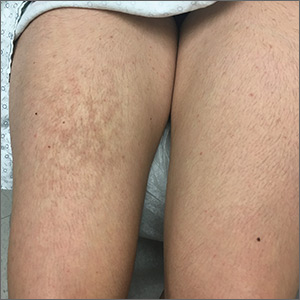

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; lcyoung@mednet.ucla.edu

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; lcyoung@mednet.ucla.edu

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; lcyoung@mednet.ucla.edu

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

A Case of Morfan Syndrome

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to our clinic for evaluation of diffuse acanthosis nigricans (AN) that had been present since 7 years of age. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism, insulin resistance, ovarian cysts, and developmental delay. On examination, she presented with thick and verrucous plaques of AN involving the neck, abdomen, trunk, arms, and legs (Figure). The intertriginous areas were affected the most. The examination also was notable for dysmorphic facies and an endomorphic body habitus. Both parents denied similar health problems in their family and were normal in appearance. Although the patient was receiving metformin treatment for insulin resistance, she had not undergone any prior workup to identify a unifying syndromic cause for her physical and biochemical findings. A review of the literature showed a 1993 case report of a 5-year-old boy with mental retardation, body overgrowth, remarkable facies, and AN, which was termed Morfan syndrome.1 Because of the similarity in features, we believe that our patient’s presentation fits this syndrome. This report represents the second documented case of Morfan syndrome according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term Morfan. Additional searches using the terms acanthosis nigricans and syndrome also failed to identify any reports describing patients with a similar constellation of findings.

|

First described by Santi Unna and Monatsh Pollitzer in 1890, AN is a common dermatosis that is characterized by thick, hyperpigmented, and verrucous plaques.2,3 Although most common in symmetric distribution on flexural and intertriginous areas, AN also may involve mucosal surfaces.4 Acanthosis nigricans is associated with multiple etiologic factors, including direct autosomal transmission, genetic abnormalities, medications, malignancy, and endocrine imbalance.2 However, the diffuse generalized form of AN is almost always found in the context of malignancy or genetic syndromes.5 Historically, most attention on AN has focused on its eruptive form (so-called malignant AN), which is usually associated with internal malignancy but also may result from benign pituitary adenomas.6 Although the precise mechanism for paraneoplastic AN is still a matter of debate, it is likely the result of overactive growth factors, such as transforming growth factor α, epidermal growth factor, and α melanocyte-stimulating hormone.7 Generalized AN also has been associated with genetic abnormalities. Multiple genetic mutations have been associated with AN, including the genes coding for the insulin receptor, fibroblast growth receptors 2 and 3, lamin A/C, and seipin.8-12 Acanthosis nigricans has been described as a feature in other genetic syndromes but may represent an incidental finding.4 In 1976, Kahn et al13 linked AN with insulin resistance, which subsequently shifted the focus on AN’s link with obesity and as a precursor of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6,14 In these cases, it is hypothesized that excess insulin activates the insulinlike growth factor 1 receptor to stimulate keratinocyte and dermal fibroblast proliferation. It is likely that hyperinsulinemia also induces cellular proliferation indirectly through other pathways.15,16 Compared with paraneoplastic and syndromic causes, AN secondary to hyperinsulinemia and obesity does not tend to be generalized but instead is proportionate to the degree of metabolic derangement.17

Because our patient’s AN presentation was diffuse, long-standing, and occurred in the context of morphologic abnormalities, it was consistent with a syndrome. Based on the constellation of findings, we believe our patient fit the rare markers indicating Morfan syndrome. Because of its extreme rarity, there is no specific diagnostic algorithm for Morfan syndrome. As additional cases are reported, we hope that further biochemical, physical, and genetic studies may be pursued to better identify the syndrome and elucidate its pathogenesis.

1. Seemanová E, Rüdiger HW, Dreyer M. Morfan: a new syndrome characterized by mental retardation, pre- and postnatal overgrowth, remarkable face and acanthosis nigricans in 5-year-old boy. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:525-528.

2. Rendon MI, Cruz PD Jr, Sontheimer RD, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a cutaneous marker of tissue resistance to insulin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:461-469.

3. Unna PG, Morris M, Besnier E, eds. International Atlas of Rare Skin Diseases. London, England: HK Lewis & Co; 1890.

4. Schwartz RA. Acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1-19.

5. Inamdar AC, Palit A. Generalized acanthosis nigricans in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:277-279.

6. Cruz PD, Hud JA. Excess insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor receptors: proposed mechanism for acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:82-85.

7. Krawczyk M, Mykała-Cies´la J, Kołodziej-Jaskuła A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

8. Meyers GA, Orlow SJ, Munro IR, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) transmembrane mutation in Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans. Nature Genet. 1995;11:462-464.

9. Moller DE, Cohen O, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Prevalence of mutations in the insulin receptor gene in subjects with features of the type A syndrome of insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1994;43:247-255.

10. Przylepa KA, Paznekas W, Zhang M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutations in Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome. Nature Genet. 1996;13:492-494.

11. Anderson JL, Khan M, David WS, et al. Confirmation of linkage of hereditary partial lipodystrophy to chromosome 1q21-22. Am J Med Genet. 1992;82:161-165.

12. Simha V, Agarwal AK, Aronin PA, et al. Novel subtype of congenital generalized lipodystrophy associated with muscular weakness and cervical spine instability. Am J Med Genet. 2008;146A:2318-2326.

13. Kahn CR, Flier JS, Bar RS, et al. the syndromes of insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans. insulin-receptor disorders in man. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:739-745.

14. Brickman WWJ, Huang J, Silverman BL, et al. Acanthosis nigricans identifies youth at high risk for metabolic abnormalities. J Pediatr. 2010;156:87-92.

15. Le Roith D. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. insulin-like growth factors.

N Engl J Med. 1997;336:633-640.

16. Nakae J, Kido Y, Accili D. Distinct and overlapping functions of insulin and IGF-I receptors. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:818-835.

17. Berk DR, Spector EB, Bayliss SJ. Familial acanthosis nigricans due to K650T FGFR3 mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1153-1156.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to our clinic for evaluation of diffuse acanthosis nigricans (AN) that had been present since 7 years of age. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism, insulin resistance, ovarian cysts, and developmental delay. On examination, she presented with thick and verrucous plaques of AN involving the neck, abdomen, trunk, arms, and legs (Figure). The intertriginous areas were affected the most. The examination also was notable for dysmorphic facies and an endomorphic body habitus. Both parents denied similar health problems in their family and were normal in appearance. Although the patient was receiving metformin treatment for insulin resistance, she had not undergone any prior workup to identify a unifying syndromic cause for her physical and biochemical findings. A review of the literature showed a 1993 case report of a 5-year-old boy with mental retardation, body overgrowth, remarkable facies, and AN, which was termed Morfan syndrome.1 Because of the similarity in features, we believe that our patient’s presentation fits this syndrome. This report represents the second documented case of Morfan syndrome according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term Morfan. Additional searches using the terms acanthosis nigricans and syndrome also failed to identify any reports describing patients with a similar constellation of findings.

|

First described by Santi Unna and Monatsh Pollitzer in 1890, AN is a common dermatosis that is characterized by thick, hyperpigmented, and verrucous plaques.2,3 Although most common in symmetric distribution on flexural and intertriginous areas, AN also may involve mucosal surfaces.4 Acanthosis nigricans is associated with multiple etiologic factors, including direct autosomal transmission, genetic abnormalities, medications, malignancy, and endocrine imbalance.2 However, the diffuse generalized form of AN is almost always found in the context of malignancy or genetic syndromes.5 Historically, most attention on AN has focused on its eruptive form (so-called malignant AN), which is usually associated with internal malignancy but also may result from benign pituitary adenomas.6 Although the precise mechanism for paraneoplastic AN is still a matter of debate, it is likely the result of overactive growth factors, such as transforming growth factor α, epidermal growth factor, and α melanocyte-stimulating hormone.7 Generalized AN also has been associated with genetic abnormalities. Multiple genetic mutations have been associated with AN, including the genes coding for the insulin receptor, fibroblast growth receptors 2 and 3, lamin A/C, and seipin.8-12 Acanthosis nigricans has been described as a feature in other genetic syndromes but may represent an incidental finding.4 In 1976, Kahn et al13 linked AN with insulin resistance, which subsequently shifted the focus on AN’s link with obesity and as a precursor of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6,14 In these cases, it is hypothesized that excess insulin activates the insulinlike growth factor 1 receptor to stimulate keratinocyte and dermal fibroblast proliferation. It is likely that hyperinsulinemia also induces cellular proliferation indirectly through other pathways.15,16 Compared with paraneoplastic and syndromic causes, AN secondary to hyperinsulinemia and obesity does not tend to be generalized but instead is proportionate to the degree of metabolic derangement.17

Because our patient’s AN presentation was diffuse, long-standing, and occurred in the context of morphologic abnormalities, it was consistent with a syndrome. Based on the constellation of findings, we believe our patient fit the rare markers indicating Morfan syndrome. Because of its extreme rarity, there is no specific diagnostic algorithm for Morfan syndrome. As additional cases are reported, we hope that further biochemical, physical, and genetic studies may be pursued to better identify the syndrome and elucidate its pathogenesis.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to our clinic for evaluation of diffuse acanthosis nigricans (AN) that had been present since 7 years of age. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism, insulin resistance, ovarian cysts, and developmental delay. On examination, she presented with thick and verrucous plaques of AN involving the neck, abdomen, trunk, arms, and legs (Figure). The intertriginous areas were affected the most. The examination also was notable for dysmorphic facies and an endomorphic body habitus. Both parents denied similar health problems in their family and were normal in appearance. Although the patient was receiving metformin treatment for insulin resistance, she had not undergone any prior workup to identify a unifying syndromic cause for her physical and biochemical findings. A review of the literature showed a 1993 case report of a 5-year-old boy with mental retardation, body overgrowth, remarkable facies, and AN, which was termed Morfan syndrome.1 Because of the similarity in features, we believe that our patient’s presentation fits this syndrome. This report represents the second documented case of Morfan syndrome according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term Morfan. Additional searches using the terms acanthosis nigricans and syndrome also failed to identify any reports describing patients with a similar constellation of findings.

|

First described by Santi Unna and Monatsh Pollitzer in 1890, AN is a common dermatosis that is characterized by thick, hyperpigmented, and verrucous plaques.2,3 Although most common in symmetric distribution on flexural and intertriginous areas, AN also may involve mucosal surfaces.4 Acanthosis nigricans is associated with multiple etiologic factors, including direct autosomal transmission, genetic abnormalities, medications, malignancy, and endocrine imbalance.2 However, the diffuse generalized form of AN is almost always found in the context of malignancy or genetic syndromes.5 Historically, most attention on AN has focused on its eruptive form (so-called malignant AN), which is usually associated with internal malignancy but also may result from benign pituitary adenomas.6 Although the precise mechanism for paraneoplastic AN is still a matter of debate, it is likely the result of overactive growth factors, such as transforming growth factor α, epidermal growth factor, and α melanocyte-stimulating hormone.7 Generalized AN also has been associated with genetic abnormalities. Multiple genetic mutations have been associated with AN, including the genes coding for the insulin receptor, fibroblast growth receptors 2 and 3, lamin A/C, and seipin.8-12 Acanthosis nigricans has been described as a feature in other genetic syndromes but may represent an incidental finding.4 In 1976, Kahn et al13 linked AN with insulin resistance, which subsequently shifted the focus on AN’s link with obesity and as a precursor of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6,14 In these cases, it is hypothesized that excess insulin activates the insulinlike growth factor 1 receptor to stimulate keratinocyte and dermal fibroblast proliferation. It is likely that hyperinsulinemia also induces cellular proliferation indirectly through other pathways.15,16 Compared with paraneoplastic and syndromic causes, AN secondary to hyperinsulinemia and obesity does not tend to be generalized but instead is proportionate to the degree of metabolic derangement.17

Because our patient’s AN presentation was diffuse, long-standing, and occurred in the context of morphologic abnormalities, it was consistent with a syndrome. Based on the constellation of findings, we believe our patient fit the rare markers indicating Morfan syndrome. Because of its extreme rarity, there is no specific diagnostic algorithm for Morfan syndrome. As additional cases are reported, we hope that further biochemical, physical, and genetic studies may be pursued to better identify the syndrome and elucidate its pathogenesis.

1. Seemanová E, Rüdiger HW, Dreyer M. Morfan: a new syndrome characterized by mental retardation, pre- and postnatal overgrowth, remarkable face and acanthosis nigricans in 5-year-old boy. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:525-528.

2. Rendon MI, Cruz PD Jr, Sontheimer RD, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a cutaneous marker of tissue resistance to insulin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:461-469.

3. Unna PG, Morris M, Besnier E, eds. International Atlas of Rare Skin Diseases. London, England: HK Lewis & Co; 1890.

4. Schwartz RA. Acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1-19.

5. Inamdar AC, Palit A. Generalized acanthosis nigricans in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:277-279.

6. Cruz PD, Hud JA. Excess insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor receptors: proposed mechanism for acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:82-85.

7. Krawczyk M, Mykała-Cies´la J, Kołodziej-Jaskuła A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

8. Meyers GA, Orlow SJ, Munro IR, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) transmembrane mutation in Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans. Nature Genet. 1995;11:462-464.

9. Moller DE, Cohen O, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Prevalence of mutations in the insulin receptor gene in subjects with features of the type A syndrome of insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1994;43:247-255.

10. Przylepa KA, Paznekas W, Zhang M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutations in Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome. Nature Genet. 1996;13:492-494.

11. Anderson JL, Khan M, David WS, et al. Confirmation of linkage of hereditary partial lipodystrophy to chromosome 1q21-22. Am J Med Genet. 1992;82:161-165.

12. Simha V, Agarwal AK, Aronin PA, et al. Novel subtype of congenital generalized lipodystrophy associated with muscular weakness and cervical spine instability. Am J Med Genet. 2008;146A:2318-2326.

13. Kahn CR, Flier JS, Bar RS, et al. the syndromes of insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans. insulin-receptor disorders in man. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:739-745.

14. Brickman WWJ, Huang J, Silverman BL, et al. Acanthosis nigricans identifies youth at high risk for metabolic abnormalities. J Pediatr. 2010;156:87-92.

15. Le Roith D. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. insulin-like growth factors.

N Engl J Med. 1997;336:633-640.

16. Nakae J, Kido Y, Accili D. Distinct and overlapping functions of insulin and IGF-I receptors. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:818-835.

17. Berk DR, Spector EB, Bayliss SJ. Familial acanthosis nigricans due to K650T FGFR3 mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1153-1156.

1. Seemanová E, Rüdiger HW, Dreyer M. Morfan: a new syndrome characterized by mental retardation, pre- and postnatal overgrowth, remarkable face and acanthosis nigricans in 5-year-old boy. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:525-528.

2. Rendon MI, Cruz PD Jr, Sontheimer RD, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a cutaneous marker of tissue resistance to insulin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:461-469.

3. Unna PG, Morris M, Besnier E, eds. International Atlas of Rare Skin Diseases. London, England: HK Lewis & Co; 1890.

4. Schwartz RA. Acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1-19.

5. Inamdar AC, Palit A. Generalized acanthosis nigricans in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:277-279.

6. Cruz PD, Hud JA. Excess insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor receptors: proposed mechanism for acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:82-85.

7. Krawczyk M, Mykała-Cies´la J, Kołodziej-Jaskuła A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

8. Meyers GA, Orlow SJ, Munro IR, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) transmembrane mutation in Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans. Nature Genet. 1995;11:462-464.

9. Moller DE, Cohen O, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Prevalence of mutations in the insulin receptor gene in subjects with features of the type A syndrome of insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1994;43:247-255.

10. Przylepa KA, Paznekas W, Zhang M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutations in Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome. Nature Genet. 1996;13:492-494.

11. Anderson JL, Khan M, David WS, et al. Confirmation of linkage of hereditary partial lipodystrophy to chromosome 1q21-22. Am J Med Genet. 1992;82:161-165.

12. Simha V, Agarwal AK, Aronin PA, et al. Novel subtype of congenital generalized lipodystrophy associated with muscular weakness and cervical spine instability. Am J Med Genet. 2008;146A:2318-2326.

13. Kahn CR, Flier JS, Bar RS, et al. the syndromes of insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans. insulin-receptor disorders in man. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:739-745.

14. Brickman WWJ, Huang J, Silverman BL, et al. Acanthosis nigricans identifies youth at high risk for metabolic abnormalities. J Pediatr. 2010;156:87-92.

15. Le Roith D. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. insulin-like growth factors.

N Engl J Med. 1997;336:633-640.

16. Nakae J, Kido Y, Accili D. Distinct and overlapping functions of insulin and IGF-I receptors. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:818-835.

17. Berk DR, Spector EB, Bayliss SJ. Familial acanthosis nigricans due to K650T FGFR3 mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1153-1156.