User login

Localized Argyria With Pseudo-ochronosis

Localized cutaneous argyria often presents as asymptomatic black or blue-gray pigmented macules in areas of the skin exposed to silver-containing compounds.1 Silver may enter the skin by traumatic implantation or absorption via eccrine sweat glands.2 Our patient witnessed a gun fight several years ago while on a mission trip and sustained multiple shrapnel wounds.

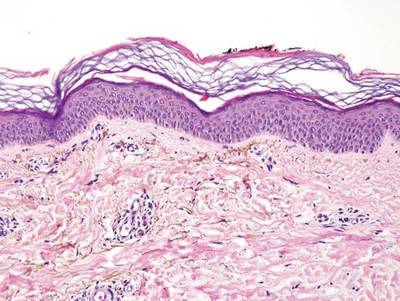

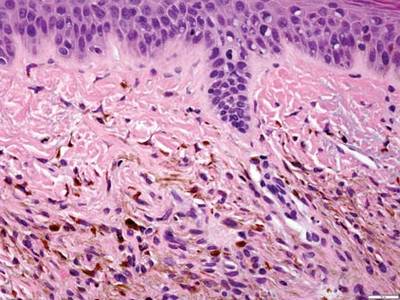

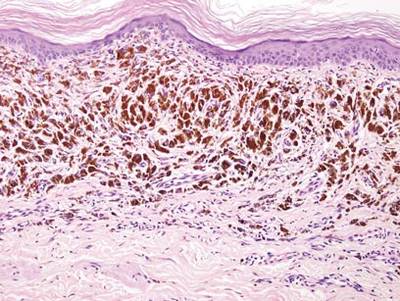

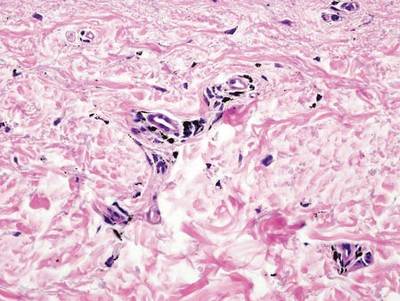

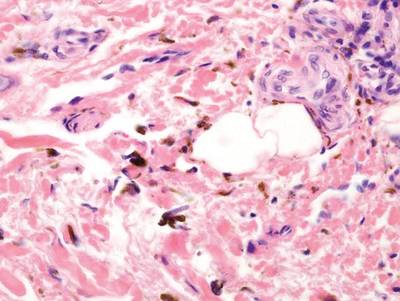

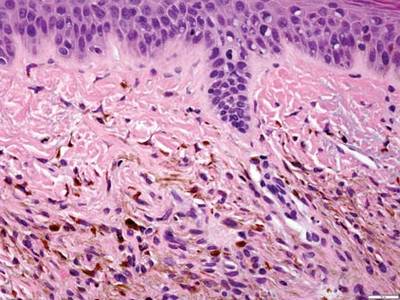

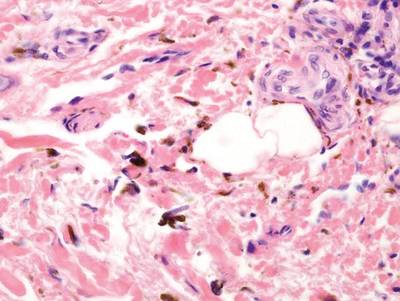

As in our patient, hyperpigmentation may appear years following initial exposure. Over time, incident light reduces colorless silver salts and compounds to black elemental silver.3 It also has been suggested that metallic silver granules stimulate tyrosine kinase activity, leading to locally increased melanin production.4 Together, these processes result in the clinical appearance of a blue-black macule. Despite its long-standing association with silver, this appearance also has been noted with deposition of other metals.5 Histologically, metal deposits can be seen as black granules surrounding eccrine glands, blood vessels, and elastic fibers on higher magnification.6 Granules also may be found in sebaceous glands and arrector pili muscle fibers. These findings do not distinguish from generalized argyria due to increased serum silver levels; however, some cases of localized cutaneous argyria have demonstrated spheroid black globules with surrounding collagen necrosis,1 which have not been reported with generalized disease. Localized cutaneous argyria also may be associated with ocher pigmentation of thickened collagen fibers, resembling changes typically found in alkaptonuria, an inherited deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase (an enzyme involved in tyrosine metabolism).7 The resulting buildup of metabolic intermediates leads to ochronosis, a deposition of ocher-pigmented intermediates in connective tissue throughout the body. In the skin, ocher pigmentation occurs in elastic fibers of the reticular dermis.1 Grossly, these changes result in a blue-gray discoloration of the skin due to a light-scattering phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect. Exogenous ochronosis also can occur, most commonly from the topical application of hydroquinone or other skin-lightening compounds.1,5 Ocher pigmentation occurring in the setting of localized cutaneous argyria is referred to as pseudo-ochronosis, a finding first described by Robinson-Bostom et al.1 The etiology of this condition is poorly understood, but Robinson-Bostom et al1 noted the appearance of dark metal granules surrounding collagen bundles and hypothesized that metal aggregates surrounding collagen bundles in pseudo-ochronosis cause a homogenized appearance under light microscopy. Yellow-brown, swollen, homogenized collagen bundles can be visualized in the reticular dermis with surrounding deposition of metal granules (Figures 1 and 2).1 Typical patterns of granule deposition in localized argyria also are present.

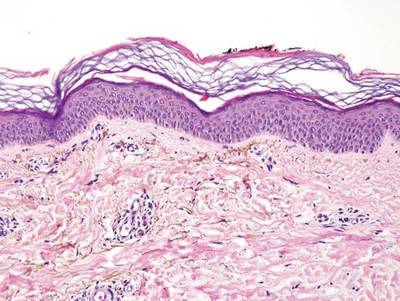

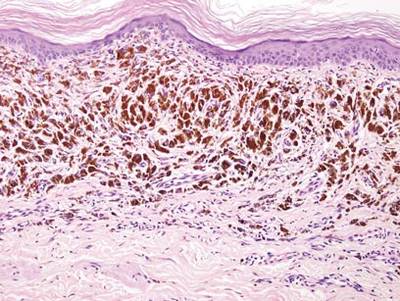

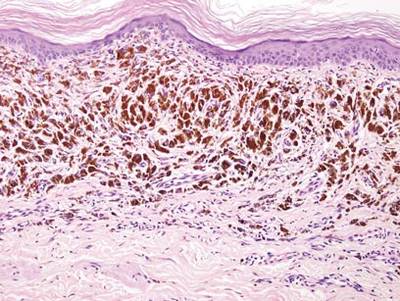

A blue nevus is a collection of proliferating dermal melanocytes. Many histologic subtypes exist and there may be extensive variability in the extent of sclerosis, cellular architecture, and tissue cellularity between each variant.8 Blue nevi commonly present as blue-black hyperpigmentation in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.9 Histologically, they are characterized by slender, bipolar, dendritic melanocytes in a sclerotic stroma (Figure 3).8 Melanocytes are highly pigmented and contain small monomorphic nuclei. Lesions are relatively homogenous and typically are restricted to the dermis with epidermal sparing.9 Dark granules and ocher fibers are absent.

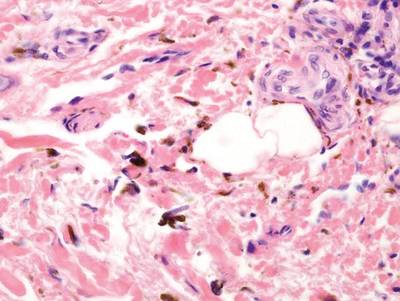

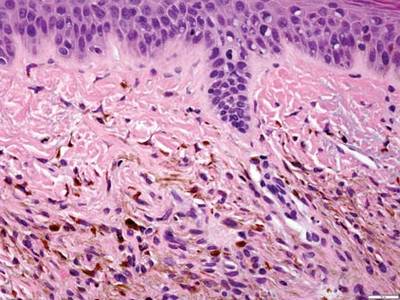

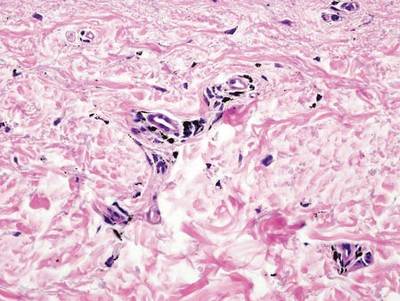

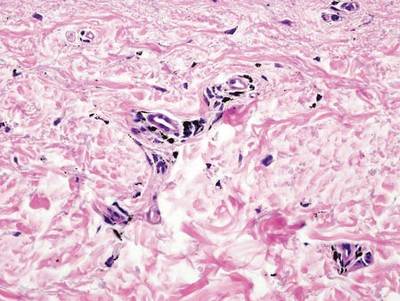

Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials may cause a macular pattern of blue-gray hyperpigmentation.10 Biopsy specimens typically reveal coarse, yellow-brown pigment granules primarily affecting the superficial dermis (Figure 4). Granules are found both extracellularly and within macrophages. Fontana-Masson silver staining may identify melanin, as hydroxychloroquine-melanin binding may contribute to patterns of hyperpigmentation.10 Hemosiderin often is present in cases of hydroxychloroquine pigmentation. Preceding ecchymosis appears to favor the deposition of hydroxychloroquine in the skin.11 The absence of dark metal granules helps distinguish hydroxychloroquine pigmentation from argyria.

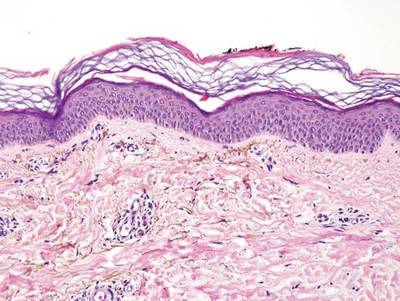

Regressed melanomas may appear clinically as gray macules. These lesions arise in cases of malignant melanoma that spontaneously regress without treatment. Spontaneous regression occurs in 10% to 35% of cases depending on tumor subtype.12 Lesions can have a variable appearance based on the degree of regression. Partial regression is demonstrated by mixed melanosis and fibrosis in the dermis (Figure 5).13,14 Melanin is housed within melanophages present in a variably expanded papillary dermis. Tumors in early stages of regression can be surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate, which becomes diminished at later stages. However, a few exceptional cases have been noted with extensive inflammatory infiltrate and no residual tumor.14 Completely regressed lesions typically appear as a band of dermal melanophages in the absence of inflammation or melanocytic atypia.15 The finding of regressed melanoma should prompt further investigation including sentinel lymph node biopsy, as it may be associated with metastasis.

Tattooing occurs following traumatic penetration of the skin with impregnation of pigmented foreign material into deep dermal layers.16 Histologic examination usually reveals clumps of fine particulate material in the dermis (Figure 6). The color of the pigment depends on the agent used. For example, graphite appears as black particles that may be confused with localized cutaneous argyria. Distinction can be made using elemental identification techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.1 The intensity of the pigment in granules found in tattoos or localized cutaneous argyria will fail to diminish with the application of melanin bleach.6

- Robinson-Bostom L, Pomerantz D, Wilkel C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:222-227.

- Tajirian AL, Campbell RM, Robinson-Bostom L. Localized argyria after exposure to aerosolized solder. Cutis. 2006;78:305-308.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED, Burmeister V. Argyria: the intradermal photograph, a manifestation of passive photosensitivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:211-217.

- Buckley WR, Terhaar CJ. The skin as an excretory organ in argyria. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1973;59:39-44.

- Shimizu I, Dill SW, McBean J, et al. Metal-induced granule deposition with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:357-359.

- Rackoff EMJ, Benbenisty KM, Maize JC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria from an acupuncture needle clini-cally concerning for metastatic melanoma. Cutis. 2007;80:423-426.

- Fernandez-Canon JM, Granadino B, Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, et al. The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nat Genet. 1996;14:5-6.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, et al. Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called ‘malignant blue nevus.’ Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:316.

- Puri PK, Lountzis NI, Tyler W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced hyperpigmentation: the staining pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1134-1137.

- Jallouli M, Francès C, Piette JC, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced pigmentation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:935-940.

- Blessing K, McLaren KM. Histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: recognition, prevalence and significance. Histopathology. 1992;20:315-322.

- LeBoit PE. Melanosis and its meanings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:369-372.

- Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

- Yang CH, Yeh JT, Shen SC, et al. Regressed subungual melanoma simulating cellular blue nevus: managed with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:577-581.

- Apfelberg DB, Manchester GH. Decorative and traumatic tattoo biophysics and removal. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:243-251.

Localized cutaneous argyria often presents as asymptomatic black or blue-gray pigmented macules in areas of the skin exposed to silver-containing compounds.1 Silver may enter the skin by traumatic implantation or absorption via eccrine sweat glands.2 Our patient witnessed a gun fight several years ago while on a mission trip and sustained multiple shrapnel wounds.

As in our patient, hyperpigmentation may appear years following initial exposure. Over time, incident light reduces colorless silver salts and compounds to black elemental silver.3 It also has been suggested that metallic silver granules stimulate tyrosine kinase activity, leading to locally increased melanin production.4 Together, these processes result in the clinical appearance of a blue-black macule. Despite its long-standing association with silver, this appearance also has been noted with deposition of other metals.5 Histologically, metal deposits can be seen as black granules surrounding eccrine glands, blood vessels, and elastic fibers on higher magnification.6 Granules also may be found in sebaceous glands and arrector pili muscle fibers. These findings do not distinguish from generalized argyria due to increased serum silver levels; however, some cases of localized cutaneous argyria have demonstrated spheroid black globules with surrounding collagen necrosis,1 which have not been reported with generalized disease. Localized cutaneous argyria also may be associated with ocher pigmentation of thickened collagen fibers, resembling changes typically found in alkaptonuria, an inherited deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase (an enzyme involved in tyrosine metabolism).7 The resulting buildup of metabolic intermediates leads to ochronosis, a deposition of ocher-pigmented intermediates in connective tissue throughout the body. In the skin, ocher pigmentation occurs in elastic fibers of the reticular dermis.1 Grossly, these changes result in a blue-gray discoloration of the skin due to a light-scattering phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect. Exogenous ochronosis also can occur, most commonly from the topical application of hydroquinone or other skin-lightening compounds.1,5 Ocher pigmentation occurring in the setting of localized cutaneous argyria is referred to as pseudo-ochronosis, a finding first described by Robinson-Bostom et al.1 The etiology of this condition is poorly understood, but Robinson-Bostom et al1 noted the appearance of dark metal granules surrounding collagen bundles and hypothesized that metal aggregates surrounding collagen bundles in pseudo-ochronosis cause a homogenized appearance under light microscopy. Yellow-brown, swollen, homogenized collagen bundles can be visualized in the reticular dermis with surrounding deposition of metal granules (Figures 1 and 2).1 Typical patterns of granule deposition in localized argyria also are present.

A blue nevus is a collection of proliferating dermal melanocytes. Many histologic subtypes exist and there may be extensive variability in the extent of sclerosis, cellular architecture, and tissue cellularity between each variant.8 Blue nevi commonly present as blue-black hyperpigmentation in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.9 Histologically, they are characterized by slender, bipolar, dendritic melanocytes in a sclerotic stroma (Figure 3).8 Melanocytes are highly pigmented and contain small monomorphic nuclei. Lesions are relatively homogenous and typically are restricted to the dermis with epidermal sparing.9 Dark granules and ocher fibers are absent.

Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials may cause a macular pattern of blue-gray hyperpigmentation.10 Biopsy specimens typically reveal coarse, yellow-brown pigment granules primarily affecting the superficial dermis (Figure 4). Granules are found both extracellularly and within macrophages. Fontana-Masson silver staining may identify melanin, as hydroxychloroquine-melanin binding may contribute to patterns of hyperpigmentation.10 Hemosiderin often is present in cases of hydroxychloroquine pigmentation. Preceding ecchymosis appears to favor the deposition of hydroxychloroquine in the skin.11 The absence of dark metal granules helps distinguish hydroxychloroquine pigmentation from argyria.

Regressed melanomas may appear clinically as gray macules. These lesions arise in cases of malignant melanoma that spontaneously regress without treatment. Spontaneous regression occurs in 10% to 35% of cases depending on tumor subtype.12 Lesions can have a variable appearance based on the degree of regression. Partial regression is demonstrated by mixed melanosis and fibrosis in the dermis (Figure 5).13,14 Melanin is housed within melanophages present in a variably expanded papillary dermis. Tumors in early stages of regression can be surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate, which becomes diminished at later stages. However, a few exceptional cases have been noted with extensive inflammatory infiltrate and no residual tumor.14 Completely regressed lesions typically appear as a band of dermal melanophages in the absence of inflammation or melanocytic atypia.15 The finding of regressed melanoma should prompt further investigation including sentinel lymph node biopsy, as it may be associated with metastasis.

Tattooing occurs following traumatic penetration of the skin with impregnation of pigmented foreign material into deep dermal layers.16 Histologic examination usually reveals clumps of fine particulate material in the dermis (Figure 6). The color of the pigment depends on the agent used. For example, graphite appears as black particles that may be confused with localized cutaneous argyria. Distinction can be made using elemental identification techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.1 The intensity of the pigment in granules found in tattoos or localized cutaneous argyria will fail to diminish with the application of melanin bleach.6

Localized cutaneous argyria often presents as asymptomatic black or blue-gray pigmented macules in areas of the skin exposed to silver-containing compounds.1 Silver may enter the skin by traumatic implantation or absorption via eccrine sweat glands.2 Our patient witnessed a gun fight several years ago while on a mission trip and sustained multiple shrapnel wounds.

As in our patient, hyperpigmentation may appear years following initial exposure. Over time, incident light reduces colorless silver salts and compounds to black elemental silver.3 It also has been suggested that metallic silver granules stimulate tyrosine kinase activity, leading to locally increased melanin production.4 Together, these processes result in the clinical appearance of a blue-black macule. Despite its long-standing association with silver, this appearance also has been noted with deposition of other metals.5 Histologically, metal deposits can be seen as black granules surrounding eccrine glands, blood vessels, and elastic fibers on higher magnification.6 Granules also may be found in sebaceous glands and arrector pili muscle fibers. These findings do not distinguish from generalized argyria due to increased serum silver levels; however, some cases of localized cutaneous argyria have demonstrated spheroid black globules with surrounding collagen necrosis,1 which have not been reported with generalized disease. Localized cutaneous argyria also may be associated with ocher pigmentation of thickened collagen fibers, resembling changes typically found in alkaptonuria, an inherited deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase (an enzyme involved in tyrosine metabolism).7 The resulting buildup of metabolic intermediates leads to ochronosis, a deposition of ocher-pigmented intermediates in connective tissue throughout the body. In the skin, ocher pigmentation occurs in elastic fibers of the reticular dermis.1 Grossly, these changes result in a blue-gray discoloration of the skin due to a light-scattering phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect. Exogenous ochronosis also can occur, most commonly from the topical application of hydroquinone or other skin-lightening compounds.1,5 Ocher pigmentation occurring in the setting of localized cutaneous argyria is referred to as pseudo-ochronosis, a finding first described by Robinson-Bostom et al.1 The etiology of this condition is poorly understood, but Robinson-Bostom et al1 noted the appearance of dark metal granules surrounding collagen bundles and hypothesized that metal aggregates surrounding collagen bundles in pseudo-ochronosis cause a homogenized appearance under light microscopy. Yellow-brown, swollen, homogenized collagen bundles can be visualized in the reticular dermis with surrounding deposition of metal granules (Figures 1 and 2).1 Typical patterns of granule deposition in localized argyria also are present.

A blue nevus is a collection of proliferating dermal melanocytes. Many histologic subtypes exist and there may be extensive variability in the extent of sclerosis, cellular architecture, and tissue cellularity between each variant.8 Blue nevi commonly present as blue-black hyperpigmentation in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.9 Histologically, they are characterized by slender, bipolar, dendritic melanocytes in a sclerotic stroma (Figure 3).8 Melanocytes are highly pigmented and contain small monomorphic nuclei. Lesions are relatively homogenous and typically are restricted to the dermis with epidermal sparing.9 Dark granules and ocher fibers are absent.

Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials may cause a macular pattern of blue-gray hyperpigmentation.10 Biopsy specimens typically reveal coarse, yellow-brown pigment granules primarily affecting the superficial dermis (Figure 4). Granules are found both extracellularly and within macrophages. Fontana-Masson silver staining may identify melanin, as hydroxychloroquine-melanin binding may contribute to patterns of hyperpigmentation.10 Hemosiderin often is present in cases of hydroxychloroquine pigmentation. Preceding ecchymosis appears to favor the deposition of hydroxychloroquine in the skin.11 The absence of dark metal granules helps distinguish hydroxychloroquine pigmentation from argyria.

Regressed melanomas may appear clinically as gray macules. These lesions arise in cases of malignant melanoma that spontaneously regress without treatment. Spontaneous regression occurs in 10% to 35% of cases depending on tumor subtype.12 Lesions can have a variable appearance based on the degree of regression. Partial regression is demonstrated by mixed melanosis and fibrosis in the dermis (Figure 5).13,14 Melanin is housed within melanophages present in a variably expanded papillary dermis. Tumors in early stages of regression can be surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate, which becomes diminished at later stages. However, a few exceptional cases have been noted with extensive inflammatory infiltrate and no residual tumor.14 Completely regressed lesions typically appear as a band of dermal melanophages in the absence of inflammation or melanocytic atypia.15 The finding of regressed melanoma should prompt further investigation including sentinel lymph node biopsy, as it may be associated with metastasis.

Tattooing occurs following traumatic penetration of the skin with impregnation of pigmented foreign material into deep dermal layers.16 Histologic examination usually reveals clumps of fine particulate material in the dermis (Figure 6). The color of the pigment depends on the agent used. For example, graphite appears as black particles that may be confused with localized cutaneous argyria. Distinction can be made using elemental identification techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.1 The intensity of the pigment in granules found in tattoos or localized cutaneous argyria will fail to diminish with the application of melanin bleach.6

- Robinson-Bostom L, Pomerantz D, Wilkel C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:222-227.

- Tajirian AL, Campbell RM, Robinson-Bostom L. Localized argyria after exposure to aerosolized solder. Cutis. 2006;78:305-308.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED, Burmeister V. Argyria: the intradermal photograph, a manifestation of passive photosensitivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:211-217.

- Buckley WR, Terhaar CJ. The skin as an excretory organ in argyria. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1973;59:39-44.

- Shimizu I, Dill SW, McBean J, et al. Metal-induced granule deposition with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:357-359.

- Rackoff EMJ, Benbenisty KM, Maize JC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria from an acupuncture needle clini-cally concerning for metastatic melanoma. Cutis. 2007;80:423-426.

- Fernandez-Canon JM, Granadino B, Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, et al. The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nat Genet. 1996;14:5-6.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, et al. Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called ‘malignant blue nevus.’ Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:316.

- Puri PK, Lountzis NI, Tyler W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced hyperpigmentation: the staining pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1134-1137.

- Jallouli M, Francès C, Piette JC, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced pigmentation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:935-940.

- Blessing K, McLaren KM. Histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: recognition, prevalence and significance. Histopathology. 1992;20:315-322.

- LeBoit PE. Melanosis and its meanings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:369-372.

- Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

- Yang CH, Yeh JT, Shen SC, et al. Regressed subungual melanoma simulating cellular blue nevus: managed with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:577-581.

- Apfelberg DB, Manchester GH. Decorative and traumatic tattoo biophysics and removal. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:243-251.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Pomerantz D, Wilkel C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:222-227.

- Tajirian AL, Campbell RM, Robinson-Bostom L. Localized argyria after exposure to aerosolized solder. Cutis. 2006;78:305-308.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED, Burmeister V. Argyria: the intradermal photograph, a manifestation of passive photosensitivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:211-217.

- Buckley WR, Terhaar CJ. The skin as an excretory organ in argyria. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1973;59:39-44.

- Shimizu I, Dill SW, McBean J, et al. Metal-induced granule deposition with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:357-359.

- Rackoff EMJ, Benbenisty KM, Maize JC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria from an acupuncture needle clini-cally concerning for metastatic melanoma. Cutis. 2007;80:423-426.

- Fernandez-Canon JM, Granadino B, Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, et al. The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nat Genet. 1996;14:5-6.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, et al. Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called ‘malignant blue nevus.’ Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:316.

- Puri PK, Lountzis NI, Tyler W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced hyperpigmentation: the staining pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1134-1137.

- Jallouli M, Francès C, Piette JC, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced pigmentation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:935-940.

- Blessing K, McLaren KM. Histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: recognition, prevalence and significance. Histopathology. 1992;20:315-322.

- LeBoit PE. Melanosis and its meanings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:369-372.

- Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

- Yang CH, Yeh JT, Shen SC, et al. Regressed subungual melanoma simulating cellular blue nevus: managed with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:577-581.

- Apfelberg DB, Manchester GH. Decorative and traumatic tattoo biophysics and removal. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:243-251.